Abstract

The essential but also toxic gaseous signaling molecule nitric oxide is scavenged by the reduced vitamin B12 complex cob(II)alamin. The resulting complex, nitroxylcobalamin (NO−-Cbl(III)), is rapidly oxidized to nitrocobalamin (NO2Cbl) in the presence of oxygen; however it is unlikely that nitrocobalamin is itself stable in biological systems. Kinetic studies on the reaction between NO2Cbl and the important intracellular antioxidant, glutathione (GSH), are reported. In this study, a reaction pathway is proposed in which the β-axial ligand of NO2Cbl is first substituted by water to give aquacobalamin (H2OCbl+), which then reacts further with GSH to form glutathionylcobalamin (GSCbl). Independent measurements of the four associated rate constants k1, k−1, k2, and k−2 support the proposed mechanism. These findings provide insight into the fundamental mechanism of ligand substitution reactions of cob(III)alamins with inorganic ligands at the β-axial site.

Keywords: Vitamin B12, Cob(III)alamin, Bioinorganic chemistry, Kinetics, Reaction mechanisms

Introduction

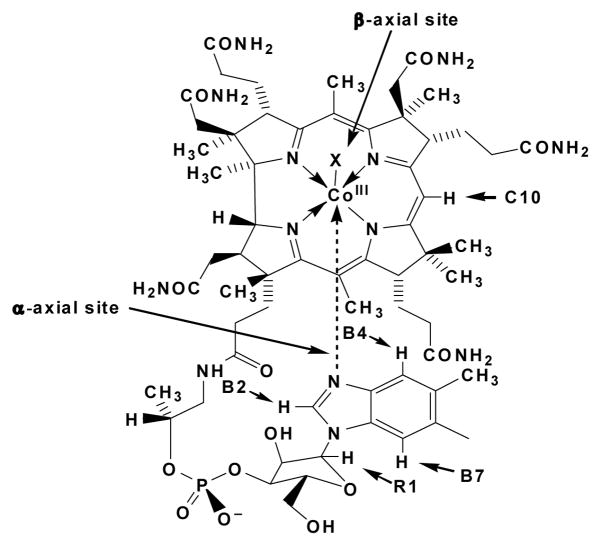

Two essential enzymes in mammals, L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, and methionine synthase, and numerous bacterial enzymes require the vitamin B12 derivatives (= cobalamins, Cbls) adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl) and methylcobalamin (MeCbl) as cofactors, Figure 1.[1] MeCbl-dependent methionine synthase transfers a methyl group from methyltetrahydrofolate to homocysteine to generate tetrahydrofolate and methionine, whereas AdoCbl-dependent L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase catalyzes the isomerization of L-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA.[1] Cobalamins may also have additional roles in biological systems, including regulating the immune response and protecting against intracellular oxidative stress.[2]

Figure 1.

Structure of cobalamins showing the two axial sites (upper = β, lower = α) with respect to the corrin ring.

The signaling molecule nitric oxide (•NO) plays a key role in the immune response, vasodilation, and neurotransmission.[3] However, high levels of NO can be deleterious and can result in sepsis and septic shock,[4] leading to organ failure and even death. Importantly, administering cobalamins suppresses •NO-induced relaxation of smooth muscle,[5] •NO-induced vasodilation[6] and •NO-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation.[7] Cobalamins also reverse •NO-induced neural tube defects.[8] Both mammalian B12-dependent enzymes are inhibited by •NO.[9] With the exception of glutathionylcobalamin (X = glutathione, Figure 1), •NO does not directly react with cob(III)alamins,[10] whereas the rate of the reaction between cob(II)alamin and nitric oxide to form nitrosylcobalamin (NOCbl) is almost diffusion controlled and essentially irreversible.[11] Given that all cob(III)alamins are readily reduced by intracellular reductases,[12] it is likely that cob(II)alamin reacts with •NO in biological systems, to form NOCbl.

In discussions of the biological relevance of NOCbl formation, we have observed that authors neglect to mention that NOCbl itself is not a stable entity.[5a, 6–8, 9c–e] However, in the presence of even minute amounts of air, orange NOCbl rapidly oxidizes to form red nitrocobalamin, NO2Cbl.[13] Indeed, we have used this property of NOCbl in our laboratory numerous times to check the condition of valves and taps used in strictly anaerobic experimental setups. The intracellular fate of NO2Cbl is unclear. Possibilities include NO2Cbl being reduced by intracellular reductases, and/or NO2Cbl reacting with the strong nucleophile and reductant glutathione (GSH), which is present in mM concentrations in cells.[14] In this work we report kinetic studies on the reaction of NO2Cbl with glutathione. Interestingly, our kinetic data show that GSH does not directly react with NO2Cbl, but instead reacts with aquacobalamin, which is always present in equilibrium, albeit typically in small amounts, with cobalamins incorporating inorganic ligands at the β-axial cobalamin site (Figure 1).

Results and Discussion

Kinetic data were collected for the reaction of NO2Cbl with glutathione (GSH). Experiments were initiated by adding a small aliquot of concentrated aqueous NO2Cbl solution (final concentration 5.0 × 10−5 M) to a buffered GSH solution (3.00 mL) at a specific pH condition (I = 1.0 M (NaCF3SO3)). Control experiments established that rate constants were identical within experimental error in the absence and presence of air; hence all experiments were carried out under aerobic conditions. Importantly, dissolving NO2Cbl in water rather than in buffer minimized the decomposition of NO2Cbl to aquacobalamin (H2OCbl+) prior to the addition of an aliquot of this solution into a buffered GSH solution.

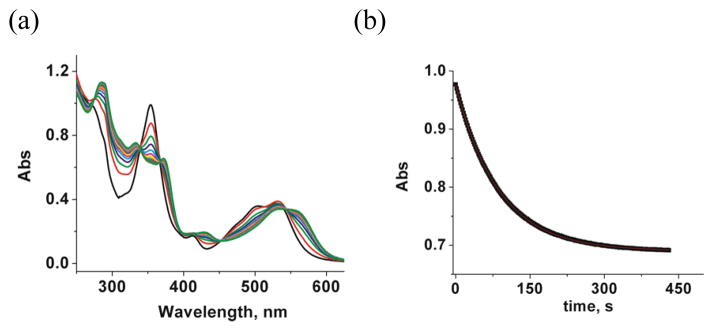

Figure 2(a) shows UV-vis spectral changes observed upon the addition of NO2Cbl to a buffered GSH solution (5.00 × 10−2 M) at pH 4.00. NO2Cbl (λmax 354, 413 and 532) is converted to GSCbl (λmax 333, 372, 428 and 534[15]) with isosbestic points at 336, 367, 452 and 543, indicating that a single reaction occurs. The corresponding plot at 354 nm versus time is given in Figure 2(b). The data fit well to the first-order rate equation, giving an observed rate constant, kobs= (1.15 ± 0.07) × 10−2 s−1.

Figure 2.

(a) UV-vis spectra for the reaction of GSH (5.00 × 10−2 M) with NO2Cbl (5.0 × 10−5 M) at pH 4.00 (25.0 °C, 0.020 M NaOAc, I = 1.0 M, NaCF3SO3). Selected spectra for the reaction are shown every 1.00 min. (b) Plot of absorbance at 354 nm versus time for the experiment shown in 2(a). Data were fitted to a first-order rate equation, giving kobs = (1.15 ± 0.07) × 10−2 s−1.

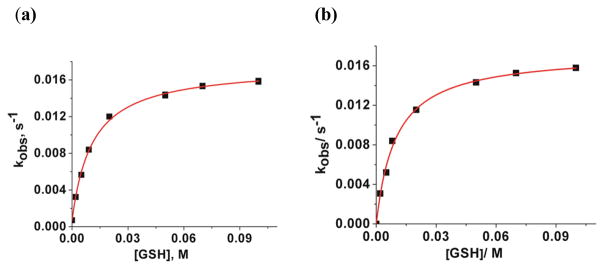

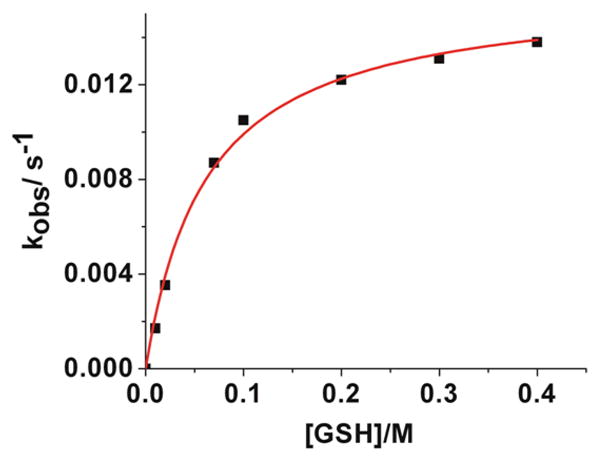

Kinetic data were collected at pH 4.00 and 7.00, in order to determine whether the rate of the reaction is pH dependent. Plots of kobs versus total GSH concentration are shown in Figures 3(a) and 3(b). These plots indicate that the observed rate constant reach a limiting value at high GSH concentrations and that there is no pH dependence in this pH region. There are two plausible mechanisms by which NO2Cbl reacts with GSH to give a plot exhibiting curvature to reach a limiting value of kobs at high GSH concentrations (saturation kinetics). The first involves rapid equilibration to form a NO2Cbl•GSH association complex prior to rate-determining substitution of the β-axial NO2− ligand of NO2Cbl by GSH to give GSCbl. The other alternative is a two step process, in which H2OCbl+, which is in equilibrium with NO2Cbl, reacts with GSH, Scheme 1. Given that all Cbls with β-axial inorganic ligands exist in equilibrium with H2OCbl+ and that Cbls undergo β-axial ligand exchange via a dissociative interchange mechanism,[16] the latter possibility is more likely to occur. Kinetic studies on the reaction between H2OCbl+/HOCbl and GSH have been reported,[17] and show that H2OCbl+ reacts rapidly with GSH to form GSCbl under the conditions of our study.

Figure 3.

Plots of kobs vs [GSH] at pH 4.00 (a) and 7.00 (b) for the reaction between NO2Cbl (5.00 × 10−5 M) and glutathione (25.0 °C, 0.020 M NaOAc (a) or 0.020 M KH2PO4 (b), I = 1.0 M (NaCF3SO3)). Data in (a) were fitted to eq (2) in the text fixing k−2 = 7.4 × 10−4 s−1, giving k1 = (1.75 ± 0.02) × 10−2 s−1 and K = 94.5 ± 3.7 M−1 at pH 4.00. Data in (b) were fitted to eq (2) fixing k−2 = 0 s−1, giving k1 = (1.73 ± 0.05) × 10−2 s−1 and K = 102.1 ± 9.7 M−1 at pH 7.00.

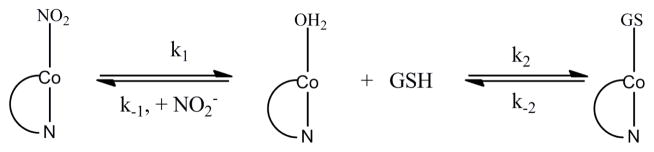

Scheme 1.

Proposed reaction pathway for the reaction of NO2Cbl with GSH. Note that in aqueous solution H2OCbl+ exists in equilibrium with HOCbl (pKa(H2OCbl+) = 7.8 [17]); however at the pH conditions of our kinetic experiments HOCbl formation is unimportant, since the values of the rate constants k−1 and k2 are the same at pH 4.00 and 7.00.

The rate expression corresponding to the reaction pathway shown in Scheme 1 is [18]

| (1) |

| (2) |

where K = k2/(k−1[NO2−]). The rate constant, k−2, for decomposition of GSCbl to H2OCbl+ and GSH was independently determined at pH 4.00 and found to be (7.4 ± 0.5) × 10−4 s−1, Figure S1, Supporting Information. Previous studies have shown that the observed equilibrium constant for formation of GSCbl, Kobs(GSCbl), = k2/k−2, increases by approximately one order of magnitude for each unit change in pH.[17] Since k2 is pH independent,[17] k−2 is therefore negligible at pH 7.00. Data in Figure 3(a) were fitted to eq (2) fixing k−2 = 7.4 × 10−4 s−1, giving k1= (1.75 ± 0.02) × 10−2 s−1 and K = 94.5 ± 3.7 M−1. Data in (b) were fitted to the same equation fixing k−2 = 0 s−1, giving k1 = (1.73 ± 0.05) × 10−2 s−1 and K = 102.1 ± 9.7 M−1. K is therefore also pH independent in the pH 4–7 region, within experimental error.

Importantly, if our model is correct, then K = k2/(k−1[NO2−]). Note, however, that the free nitrite concentration is not strictly constant during the reaction, but will vary from 0 to a maximum value of 5.0 × 10−5 M as the reaction proceeds, as NO2Cbl (5.0 × 10−5 M) reacts with GSH to give GSCbl plus NO2−. Hence K is not strictly constant during the reaction, as reflected in the error associated with K. In order to provide support for our model, new data was therefore collected at pH 7.00 under the same conditions as the experiments summarized in Figure 3(b), except that 5.00 × 10−4 M NaNO2 was added to each solution, so the nitrite concentration is constant (pseudo-first order conditions) during the reaction. These data are shown in Figure 4. Fitting this data to eq (2) fixing k−2 = 0 s−1 gave k1 = (1.60 ± 0.05) × 10−2 s−1 and K = 16.2 ± 0.2 M−1. The data now fit considerably better to eq (2) as expected (the error in K is now one order of magnitude smaller), since the nitrite concentration remains constant during the reaction.

Figure 4.

Plot of kobs vs [GSH] for the reaction between NO2Cbl (5.0 × 10−5 M) and GSH in the presence of 5.00 × 10−4 M NaNO2 at pH 7.00 (25.0°C, 0.020 M KH2PO4, 5.00×10−4 M NaNO2, I = 1.0 M, NaCF3SO3). Data were fitted to eq (2) in the text fixing k−2 = 0, giving k1 = (1.60 ±0.05) × 10−2s−1 and K = 16.2 ± 0.2 M−1.

The rate constant k2 for the reaction of H2OCbl+ with GSH was also independently determined at pH 4.00 and found to be 12.00 ± 0.25 M−1 s−1 (25.0 °C, 0.020 M NaCH3COO, I = 1.00 M (NaCF3SO3)), Figure S2, Supporting Information. This value is in good agreement with a value reported by us under slightly different conditions (k2 = 18.5 M−1 s−1 at pH 4.50, 25.0 °C, 0.10 M NaOAc, I = 0.50 M (KNO3)[17]), and is pH independent in the pH 4–7 range.[17] The rate constant k−1 for the reaction between H2OCbl+ and NO2− was independently determined to be (1.25 ± 0.02) × 103 and (1.20 ± 0.02) × 103 M−1 s−1 at pH 4.00 and 7.00, respectively, Figures S3 and S4, Supporting Information. Hence k−1 is also independent of the pH (pH 4–7), as expected, as the ionization of the reactants is essentially unchanged (pKa(HNO2) ~ 3.2; pKa(H2OCbl+) = 7.8 [17]) in this pH region. The value of k−1 agrees well with a value reported by others (k−1 = 99.8 × 102 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C, I = 2.2 M (NaNO3)).[19] Using k2 = 12.00 M−1 s−1, k−1 = 1.23 × 103 M−1 s−1 and NO2− = 5.00 × 10−4 M gives K ~20 M−1, which is in very good agreement with the experimental value of K obtained from the best fit of the data (16.2 ± 0.2 M−1), providing strong support for the reaction pathway proposed in Scheme 1.

Finally, the rate constant k1 for decomposition of NO2Cbl to H2OCbl+ was also independently determined by obtaining kinetic data for the decomposition of NO2Cbl to H2OCbl+ upon dissolving NO2Cbl in buffer. Figure S5 in the Supporting Information shows the absorbance change (ΔAbs = 0.013 at 350 nm) that occurs at pH 4.00. Only a small fraction of NO2Cbl is converted to H2OCbl+; however the absorbance change is sufficient to allow calculation of k1. The results at different pH conditions are summarized in Table S1, and give a mean value for k1 of (1.48 ± 0.22) × 10−2 M−1 s−1 (pH 3.5 – 6.0; k1 is pH independent). The observed rate constant for NO2Cbl partially decomposing to give H2OCbl+ is actually k1 + k−1[NO2−] for the pseudo-first-order reversible process. A separate experiment showed that an absorbance difference of 0.232 is observed upon completely converting H2OCbl+ to NO2Cbl upon the addition of a slight excess of NO2− (CblT = 5.0 × 10−5 M). Hence an absorbance change of 0.013 corresponds to formation of 5.6% H2OCbl+ (2.8 × 10−6 M H2OCbl+ and 2.8 × 10−6 M NO2−) upon dissolving NO2Cbl in H2OCbl+; that is, the maximum NO2− is 2.8 × 10−6 M. Using k1 = 1.48 × 10−2 M−1 s−1, k−1 = (1.25 ± 0.02) × 103 and [NO2−] = 2.8 × 10−6 M shows that k1 is ~ 5 times larger than k−1[NO2−], validating the assumption that kobs ~ k1 upon dissolving NO2Cbl in H2OCbl+. Using our values of k1 and k−1, the equilibrium constant for formation of NO2Cbl, K(NO2Cbl), = k−1/k1, is 8.5 × 104 M−1, which is in reasonable agreement with a value reported by others under different ionic strength conditions (K(NO2Cbl) = 2.2 × 105 M−1, 25 °C, I = 2.2 M [20]).

Conclusions

Kinetic studies on the reaction between NO2Cbl and GSH show that the rate of the reaction is pH independent in the pH 4–7 region. By independently determining values of k1, k−1, k2 and k−2, we have shown that the data fits a model involving an H2OCbl+ intermediate, which then rapidly reacts with GSH to form GSCbl, Scheme 1. To our knowledge this is the first time that the reaction pathway of β-axial inorganic ligand exchange for cob(III)alamins via an H2OCbl+ intermediate has been unequivocally demonstrated. This may have important consequences for free and potentially even protein-bound cob(III)alamins incorporating inorganic ligands (X-ray structures of cobalamins bound to B12 transport proteins show that the β-axial site can be readily accessed by solvent and small molecules[21]) that is, the amount of each of these species may reflect the concentrations and binding constants to aquacobalamin of the various inorganic ligands present. As such, GSCbl would be expected to be the major intracellular non-alkylcob(III)alamin, given that intracellular GSH concentrations are mM,[14] and only CN− binds stronger than GSH to H2OCbl+(KCNCbl ~ 1014 M−1 [22]). Finally, at 0.5 mM GSH the rate constant for the reaction between NO2Cbl and GSH is ~ 8 × 10−3 s−1 at pH 7.0 (25 °C), corresponding to a half life of ~ 1.4 min. Hence formation of GSCbl is one possible reaction pathway by which NO2Cbl decomposes in biological systems.

Experimental Section

General

Hydroxycobalamin hydrochloride (HOCbl•HCl, 98% stated purity by manufacturer) was purchased from Fluka. Glutathione (98%), acetic acid (sodium salt, ≥99%), sodium nitrite (97%) and CF3SO3H (99%) were obtained from Acros Organics. TES buffer (98%) was purchased from MP Biomedicals Inc. Potassium dihydrogen phosphate was purchased from Sigma. NaCF3SO3 was prepared by neutralizing a concentrated, aqueous solution of CF3SO3H with NaOH, reducing it to dryness by rotary evaporation, and drying it overnight in a vacuum oven at 70.0 °C. Nitrocobalamin was synthesized and characterized according to a published procedure.[15] The purity was ≥ 95%, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

UV-visible spectra and kinetic data for slower reactions were recorded on a Cary 5000 spectrophotometer equipped with a thermostated (25.0 ± 0.1°C) cell changer operating with WinUV Bio software (version 3.00). Reactant solutions were thermostated for 15 min prior to measurements. Kinetic data for rapid reactions were obtained at 25.0 ± 0.1°C using an Applied Photophysics SX20 stopped-flow spectrophotometer equipped with a photodiode array detector in addition to a single wavelength detector. Data were collected with Pro-Data SX (version 2.1.4) and Pro-Data Viewer (version 4.1.10) software, and a 1.0 cm pathlength cell was utilized. All data were analyzed using Microcal Origin version 8.0.

pH measurements were carried out using an Orion model 710A pH meter equipped with a Wilmad 6030–02 pH electrode. The electrode was filled with a 3 M KCl/saturated AgCl solution (pH 7.0) and standardized with standard BDH buffer solutions at pH 6.98, 4.01 and 2.02. Solution pH was adjusted using 50% v/v aqueous CF3SO3Hand NaOH (~ 5 M).

1H NMR spectra was recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz spectrometer equipped with 5 mm probe. Solutions for NMR measurements were prepared in D2O. 1H NMR spectra were internally referenced to TSP (0 ppm).

Kinetic measurements

The rates of the reaction between NO2Cbl and glutathione (GSH) were determined under pseudo-first-order conditions with excess GSH. Stock solutions of GSH (0.500 M) in the presence or absence of sodium nitrite (5.00 × 10−4 M) were prepared in the appropriate buffer (0.020 M) at pH 4.00 and 7.00 and diluted as appropriate. A small aliquot of concentrated NO2Cbl (final concentration 5.0 × 10−5 M) in water was added to initiate the reaction and the absorbance at 354 nm was recorded as a function of time.

Kinetic data for the reaction between H2OCbl+ (5.0 × 10−5 M) with varying concentrations of NO2− were obtained at pH 4.00 and 7.00. Stock solutions of NaNO2 (0.010 M) were prepared in the appropriate buffer (0.020 M) and diluted as needed. Data were collected at 354 nm. Kinetic data for the reaction of H2OCbl+ (5.0 × 10−5 M) with varying concentrations of glutathione at pH 4.00 were collected at 354 nm in acetate buffer (0.020 M).

The rate of decomposition of NO2Cbl to H2OCbl+ was determined in the pH 3.5–6.0 range by adding solid NO2Cbl directly to the appropriate buffer solution (0.200 M; the solution was thermostated at 25.0 °C for 10 min prior to the addition of NaNO2). The solution was quickly filtered through a micropore filter (0.45 μm) and data collection initiated at 354 nm.

The rate of decomposition of GSCbl to H2OCbl+ was determined at pH 4.00. An aliquot of GSCbl (4.0 × 10−5 M) was added to pH 4.00 acetate buffer (0.020 M; the buffer solution was thermostated at 25.0 °C for 10 min prior to the addition of GSCbl) and data were collected at 354 nm.

The total ionic strength was maintained at 1.0 M using NaCF3SO3 for all solutions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the US National Science Foundation (CHE-084839) and the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (1R15GM094707-01A1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Funding for this work was also provided by the NSF-REU program at KSU (CHE-1004987 (D. W.) and CHE-0649017 (K. G.))..

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.eurjic.org/ or from the author.

References

- 1.a) Kräutler B, Ostermann S. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Chapter 68. Academic Press; San Diego: 2003. p. 229. [Google Scholar]; b) Banerjee R, editor. Chemistry and Biochemistry of B12. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]; c) Brown KL. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2075. doi: 10.1021/cr030720z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Scalabrino G, Mutti E, Veber D, Aloe L, Corsi MM, Galbiati S, Tredici G. Neurosci Lett. 2006;396:153. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Scalabrino G, Peracchi M. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:247. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Veber D, Mutti E, Tacchini L, Gammella E, Tredici G, Scalabrino G. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1380–1387. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mukherjee R, Brasch NE. Chem - Eur J. 2011;17:11673. [Google Scholar]; e) Birch CS, Brasch NE, McCaddon A, Williams JHH. Free Radical Biol Med. 2009;47:184. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Moreira ES, Brasch NE, Yun J. Radical Biol Med. 2011;51:876. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Suarez-Moreira E, Yun J, Birch CS, Williams JHH, McCaddon A, Brasch NE. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15078. doi: 10.1021/ja904670x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Ignarro L. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34:879. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Heinecke J, Ford PC. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:235. [Google Scholar]; c) Avery AA. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:583. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmen W. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Rand MJ, Li CG. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;241:249. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Greenberg SS, Xie J, Zatarain JM, Kapusta DR, Miller MJ. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Schubert R, [Krien U, Wulfsen I, Schiemann D, Lehmann G, Ulfig N, Veh RW, Schwarz JR, Gago H. Hypertension. 2004;43:891. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000121882.42731.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang F, Li CG, Rand MJ. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;340:181. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01381-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouwer M, Chamulitrat W, Ferruzzi G, Sauls DL, Weinberg JB. Blood. 1996;88:1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weil M, Abeles R, Nachmany A, Gold V, Michael E. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:361. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Nicolaou A, Ast T, Garcia CV, Anderson MM, Gibbons JM, Gibbons WA. Biochem Soc Trans. 1994;22:296S. doi: 10.1042/bst022296s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nicolaou A, Kenyon SH, Gibbons JM, Ast T, Gibbons WA. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996;26:167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.122254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nicolaou A, Waterfield CJ, Kenyon SH, Gibbons WA. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:876. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kambo A, Sharma VS, Casteel DE, Woods VL, Jr, Pilz RB, Boss GR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Danishpajooh IO, Gudi T, Chen Y, Kharitonov VG, Sharma VS, Boss GR. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Zheng D, Birke RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9066. doi: 10.1021/ja017684a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Roncaroli F, Shubina TE, Clark T, van Eldik R. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:7869. doi: 10.1021/ic061151r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wolak M, Stochel G, Hamza M, van Eldik R. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:2018. doi: 10.1021/ic991266d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Wolak M, Zahl A, Schneppensieper T, Stochel G, van Eldik R. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9780. doi: 10.1021/ja010530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zheng D, Birke RL. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4637. doi: 10.1021/ja015682k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Stich TA, Yamanishi M, Banerjee R, Brunold TC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7660. doi: 10.1021/ja050546r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hannibal L, Kim J, Brasch NE, Wang S, Rosenblatt DS, Banerjee R, Jacobsen DW. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;97:260. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yamada K, Gravel RA, Toraya T, Matthews RG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603694103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Watanabe F, Saido H, Yamaji R, Miyatake K, Isegawa Y, Ito A, Yubisui T, Rosenblatt DS, Nakano Y. J Nutr. 1996;126:2947. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.12.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannibal L, Smith CA, Jacobsen DW, Brasch NE. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:5140. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao R, Lind J, Merenyi G, Eriksen TE. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1997;2:569. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez-Moreira E, Hannibal L, Smith CA, Chavez RA, Jacobsen DW, Brasch NE. Dalton Trans. 2006:5269. doi: 10.1039/b610158e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier M, van Eldik R. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:2635. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia L, Cregan AG, Berben LA, Brasch NE. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:6848. doi: 10.1021/ic040022c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cregan AG, Brasch NE, van Eldik R. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:1430. doi: 10.1021/ic0009268.b) Rate constants k3, k−3, k4 and k−4 from eq(11) in reference 18(a) become k1, k−1[NO2−], k2 and k−2, respectively, in eq(1) in this article.

- 19.Marques HM, Knapton L. Dalton Trans. 1997:3827. doi: 10.1039/b416083e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapton L, Marques HM. Dalton Trans. 2005:889. doi: 10.1039/b416083e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Wuerges J, Garau G, Geremia S, Fedosov SN, Petersen TE, Randaccio L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509099103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mathews FS, Gordon MM, Chen Z, Rajashankar KR, Ealick SE, Alpers DH, Sukumar N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703228104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin DAB, Betterton EA, Pratt JM. S Afr J Chem. 1982;34:173. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.