Abstract

Background

A systematic review may evaluate different aspects of a health care intervention. To accommodate the evaluation of various research questions, the inclusion of more than one study design may be necessary. One aim of this study is to find and describe articles on methodological issues concerning the incorporation of multiple types of study designs in systematic reviews on health care interventions. Another aim is to evaluate methods studies that have assessed whether reported effects differ by study types.

Methods and Findings

We searched PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Cochrane Methodology Register on 31 March 2012 and identified 42 articles that reported on the integration of single or multiple study designs in systematic reviews. We summarized the contents of the articles qualitatively and assessed theoretical and empirical evidence. We found that many examples of reviews incorporating multiple types of studies exist and that every study design can serve a specific purpose. The clinical questions of a systematic review determine the types of design that are necessary or sufficient to provide the best possible answers. In a second independent search, we identified 49 studies, 31 systematic reviews and 18 trials that compared the effect sizes between randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, which were statistically different in 35%, and not different in 53%. Twelve percent of studies reported both, different and non-different effect sizes.

Conclusions

Different study designs addressing the same question yielded varying results, with differences in about half of all examples. The risk of presenting uncertain results without knowing for sure the direction and magnitude of the effect holds true for both nonrandomized and randomized controlled trials. The integration of multiple study designs in systematic reviews is required if patients should be informed on the many facets of patient relevant issues of health care interventions.

Introduction

A systematic review may evaluate different aspects of a health care intervention such efficacy, effectiveness, and adverse events [1]. To accommodate the evaluation of various research questions such as efficacy or effectiveness and outcomes such as survival or severe adverse events, the inclusion of more than one study design appears to be necessary. If multiple study designs are included in a systematic review they should be well selected and customized to answer to the questions of interest. Efficacy addresses the question whether the intervention of interest can work in the ideal study setting (randomized controlled trial) and typically provides a conclusion for an average patient only [2]. In some situations RCTs are not feasible due to ethical concerns or due to strong patients' preferences and the results may not be applicable to everyday practice [3]. Some nonrandomized studies are designed to evaluate effectiveness and may show that interventions will work under every day circumstances, for example in a general practice [4]. Effectiveness typically provides a conclusion for a subgroup of patients that can be applied to individual patients. Adverse events can be crucial for approval, the restriction of application to particular indications, or the discontinuation of drugs or other interventions. The comprehensive detection of adverse events may need a long-term observation of a large number of participants and an experimental research design could become a costly and unsuccessful enterprise. It appears that many public commissioners provide predominantly funding for efficacy research [4].

A considerable proportion of researchers appears dichotomized to either require the randomized design for scientific evidence on health care interventions or to also accept designs without randomization as sufficient [5]. A 'hierarchy of evidence' was established that clearly downgrades designs other than randomized studies regardless of the type of outcome evaluated [6]. Some authors questioned this hierarchy [7,8]. Advantages and disadvantages of various designs have been reported repeatedly and some authors support the integration of multiple study designs with respect to the outcome of interest [5]. We did not find a report that systematically summarized methods papers about usefulness and complexity of integrating various designs in one systematic review. Therefore, we wanted to collect experiences, recommendations, and evidence based on clinical study data reported by others to infer whether one design is superior to others or not and whether alternative or more practical designs could complement or even replace a seemingly favorable design. One aim of this study is to find and describe articles on methodological issues concerning the incorporation of multiple types of study designs in systematic reviews on health care interventions. Another aim is to evaluate methods studies that have assessed whether reported effects differ by study types. Finally, we aimed to identify and summarize qualitative evidence sufficient enough to guide finding and integrating the right research design for answering various clinical questions within systematic reviews of health care interventions.

Methods

While preparing this systematic review, we endorsed the PRISMA statement, adhered to its principles and conformed to its checklist (Table S1 ).

Inclusion criteria

We included articles reporting on how to integrate different study designs in systematic reviews of health care interventions. We did not include articles merely describing advantages and disadvantages of various designs. We also included articles reporting different results of a particular outcome that depend on the type of design such as in a comparison of a randomized vs. a nonrandomized controlled design. Since we concentrated on the reporting of various study designs, we did not specify on the type of participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Cochrane Methodology Register on 31 March 2012. The search strategy is detailed in Table 1 . Terms and syntax used for the search in PubMed were also used for the Cochrane Libarary. The MeSH term "Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic"[MeSH] aims to specifically identify RCTs [9] while the MeSH term "Epidemiologic Studies"[Mesh] comprises nonrandomized study designs [10]. We combined terms of the controlled vocabulary MeSH with text words. We searched PubMed and the Related citations function in PubMed tool to find some pertinent articles that appeared to represent the topic of the present revew. We adopted candidate text words reported by those articles in the title or the abstract to build a search strategy for nonrandomized or observational studies [11-13].

Table 1. Search strategy.

| No | Term |

|---|---|

| 1 | "Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic"[Mesh] |

| 2 | randomized controlled[tiab] |

| 3 | randomised controlled[tiab] |

| 4 | randomization[tiab] |

| 5 | randomisation[tiab] |

| 6 | random allocation[tiab] |

| 7 | "Epidemiologic studies"[Mesh] non random*[tiab] |

| 8 | nonrandom*[tiab] |

| 9 | non-random*[tiab] |

| 10 | observational[tiab] |

| 11 | quasi-experiment*[tiab] |

| 12 | quasi experiment*[tiab] |

| 13 | or/1-6 |

| 14 | or/7-12 |

| 15 | and/13-14 |

Searching PubMed, Cochrane database of systematic reviews, and the Cochrane database of methods studies on 31 March 2012.

Abbreviations and symbols. *: The asterisk represents truncation to find all terms that begin with a given text string; [Mesh]: Search field tag provided by PubMed for the search in Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms; [tiab]: Search field tag provided by PubMed for the search in the title and/or in the abstract

Study selection

We imported the bibliographic data of the search results into an EndNote X4 database. Two reviewers assessed independently title and/or abstract whether randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized studies were addressed at the same time in any type of article. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full texts were ordered if we agreed on potentially relevant references and if disagreements could not be resolved. The full text papers were assessed to see whether the methodology of how to integrate specific study designs in systematic reviews was addressed. We also marked studies that compared the results of randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized studies on the same clinical topic to estimate possible effect size differences between the two design categories.

Data collection, analysis, and synthesis

We summarized the identified statements in a descriptive manner and did not quantitatively pool any data. We worked with 2 types of reviews, systematic reviews and other reviews. The systematic review category included Cochrane systematic reviews, other systematic reviews not issued by Cochrane, and health technology assessments. The other review category included non-systematic reviews, editorials, comments, and letters. We based the rationale to include non-systematic type papers on the following reflections. We wanted to build a comprehensive review of available methods papers. We wanted to acknowledge experience-based thoughts and reasonings and we wanted to include rationales and recommendations with respect to integrate various designs in systematic reviews that have been developed by others. We did not expect a large number of systematic reviews and we apprehended a limited scope of topics if we would have confined the data collection to systematic reviews only. Nevertheless, we stratified the results presentation by the two review types.

We identified 16 separately reported clinical fields and we used one additional category for articles that combined two or more clinical fields. The 17 categories were:

-

•

Acupuncture: Intervention regarding acupuncture type of complementary and alternative medicine)

-

•

Cardiology: Interventional procedures to reopen coronary arteries as opposed to surgical interventions

-

•

Genetics: Genetic diseases and rare diseases

-

•

HRT: Hormone replacement therapy for women

-

•

Mental: Intervention to treat a mental disease such as depression

-

•

Nephrology: Intevention regarding renal disease

-

•

Nutrition: Influence of food on health

-

•

Orthopedics: Intervention regarding orthopedic disease

-

•

Palliation: Intervention regarding palliative treatment

-

•

Pediatrics: Intervention regarding children

-

•

Pharma: Drugs to treat patients

-

•

Pregnancy: Intervention regarding pregnant women

-

•

Social: Complex social interventions

-

•

Surgery: Surgical intervention regarding various diseases

-

•

Tele: Intervention regarding telehealth issues

-

•

Transplant: Autologous or allogeneic transplantation of organs

-

•

Various: Two or more different clinical fields

We created 8 distinct categories for classifying the type of study design:

-

•

RCT: Randomized controlled trial

-

•

NRCT: Nonrandomized controlled trial: prospective comparative trial with allocation of patients by physician

-

•

Cohort study: Prospective or retrospective observational study with a control group without allocation of patients by physician, start is intervention

-

•

CCS: Case-control study: retrospective study, start is events

-

•

Regist: Registry of data from patients with particular diseases or interventions

-

•

Admin: Administrative databases such as data from health care providers

-

•

Survey: Survey or audit as well as postmarketing analysis

-

•

Cases: Single case or case series

We identified a considerable number of different methodological topics relevant for the integration of various study designs in systematic reviews. As some of the topics were similar, we assigned these topics to 15 methodological categories. All major issues such as validity, applicability, and confounding were addressed in the papers.

-

•

Adherence: Patients may adhere to the prescription or may not take drugs or doses as wanted

-

•

Adverse events: Patients may experience unwanted effects or events that are associated with the intervention

-

•

Applicability: Results may not be generalized to patients that have different characteristics than the study population

-

•

Case load: The number of patients with a particular disease or intervention admitted to a hospital or treated by a physician

-

•

Confounding: A known or unknown factor that is associated with the intervention and influences the outcome

-

•

Exclusions: Certain patients are excluded from the recruitment such as elderly, pregnant women, children, patients with comorbidities

-

•

Heterogeneity: Patients within one treatment group differ in baseline characteristics such as severity of disease

-

•

Long term: Follow up more than 12 months after the intervention

-

•

Participation: Eligible individuals who did not participate in trials

-

•

Pathophysiol: Pathophysiological issues such as bacterial cause or various genetic constitution

-

•

Preferences: Patients and physicians may have preferences about what treatment is best

-

•

Rare disease: Rare diseases may not be represented in clinical trials and rare adverse events may not be detected by small studies

-

•

Specialisation: The level of education and experience of a physician may influence the outcome

-

•

Survival: Proportion of patients that sustain a specific wanted status after a certain time period

-

•

Validity: To measure what should be measured; minimizing uncertainty and systematic error; dealing with selection bias

Results

Search results

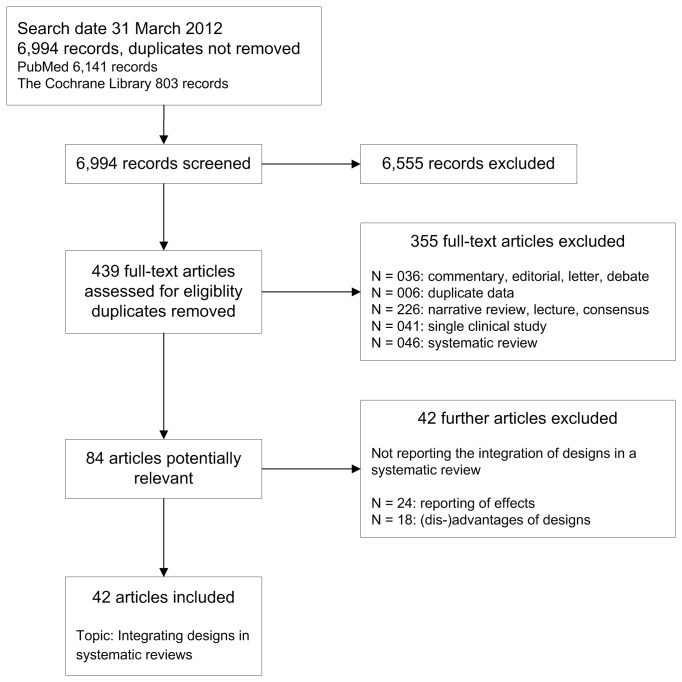

We included 42 articles that report about the integration of study designs in systematic reviews (Figure 1 ) [5,7,8,14-52]. In the first step of the study selection process, we retrieved 6994 records from electronic databases including 6141 citations from PubMed and 803 citations from the Cochrane Library. The Cochrane Library citations were made of 188 systematic reviews and 526 methods studies. After excluding 6555 records not relevant to the topic of interest or duplicates, we assessed the fulltexts of 439 different articles. After a first screening process, we excluded 355 articles and after a repeated screening of the remaining potentially relevant fulltexts, we excluded another 42 articles. The reasons for exclusion are shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. Literature retrieval and study selection.

Characteristics of included articles

The characteristics of included articles are shown in Table 2 and Table 3 . We identified 8 systematic reviews [14,17-20,33,34,38] and 34 non-systematic reviews including editorials, comments, or letters. The articles containing concepts relevant to our research question were published between 1995 and 2012. Most of the articles were published between 2005 and 2012: 73% (31 of 42) of all reviews, 62% (5 of 8) systematic reviews and 76% (26 of 34) non-systematic reviews (Table 2 ). The systematic reviews covered 4 of 16 distinct clinical field categories with 5 of 8 reviews reporting on surgery and with 1 review reporting on acupuncture, cardiology, and various clinical fields, respectively (Table 2 ). The non-systematic reviews covered 15 of 16 categories with 12 reporting on various topics, 4 reporting on surgery, no report on acupuncture, and 1 to 2 reporting on each of the rest of clinical entities.

Table 2. Characteristics of included articles.

| Author |

Year

|

Ref | Field |

Type of design

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

RCT | NRCT | Cohort | CCS | Regist | Admin | Survey | Cases | ||||

| Systematic review | ||||||||||||

| Archampong | 2012 | [14] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Britton | 1998 | [17] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Chambers | 2009 | [18] | Cardiology | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Chambers | 2010 | [18] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Chou | 2010 | [20] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Lewsey | 2000 | [33] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Linde | 2002 | [34] | Acupuncture | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Norris | 2005 | [38] | Various | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Non-systematic review | ||||||||||||

| Atkins | 2007 | [15] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 1996 | [16] | Various | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Chumbler | 2008 | [21] | Tele | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Concato (Comp) | 2010 | [7] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Concato (Observ) | 2010 | [22] | Various | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Essock | 2003 | [23] | Mental | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Fletcher | 2002 | [24] | Various | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Fletcher | 2009 | [25] | HRT | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Gale | 2009 | [26] | Transplant | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Grzeskowiak | 2012 | [27] | Pregnancy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Hadley | 2009 | [61] | Palliation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Hartling | 2005 | [29] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Hodgson | 2007 | [30] | Mental | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Hoppe | 2009 | [8] | Orthopedics | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Horn | 2010 | [31] | Various | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Kovesdy | 2012 | [32] | Nephrology | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| McCarthy | 2008 | [35] | Surgery | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Mercer | 2007 | [36] | Various | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Mitchell | 1995 | [37] | Pediatrics | 1 | ||||||||

| Norris | 2011 | [39] | Various | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Ogilvie | 2005 | [40] | Social | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Olivier | 2006 | [41] | Pharma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Reeves | 2005 | [42] | Nutrition | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Rosendaal | 2001 | [43] | Cardiology | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Sharma | 2012 | [44] | Social | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Shrier | 2007 | [45] | Various | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Silverman | 2009 | [46] | Pharma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Vandenbroucke | 1998 | [47] | Various | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2004 | [48] | Various | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2008 | [5] | Various | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2009 | [49] | HRT | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2011 | [50] | Various | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Wilcken | 2001 | [51] | Genetics | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Zlowodzki | 2006 | [52] | Various | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Frequency | 36 | 22 | 28 | 21 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 14 | ||||

Type of review. Systematic review (first 8 papers): Cochrane Systematic Review (Archampong 2012), Health Technology Assessment of National Health Service in UK (Britton 1998), other systematic reviews not issued by Cochrane or HTA (Chambers 2009, Chambers 2010, Chou 2010, Lewsey 2000, Linde 2002, Norris 2005). Non-systematic review (rest of 34 papers): narrative review or editorial or comment or letter.

Field. Acupuncture: Intervention regarding acupuncture type of complementary and alternative medicine; Cardiology: Interventional procedures to reopen coronary arteries as opposed to surgical interventions; Genetics: Genetic diseases and rare diseases; HRT: Hormone replacement therapy for women; Mental: Intervention to treat a mental disease such as depression; Nephrology: Intevention regarding renal disease; Nutrition: Influence of food on health; Orthopedics: Intervention regarding orthopedic disease; Palliation: Intervention regarding palliative treatment; Pediatrics: Intervention regarding children; Pharma: Drugs to treat patients; Pregnancy: Intervention regarding pregnant women; Social: Complex social interventions; Surgery: Surgical intervention regarding various diseases; Tele: Intervention regarding telehealth issues; Transplant: Autologous or allogeneic transplantation of organs; Various: Two or more different clinical fields

Type of design. RCT: Randomized controlled trial; NRCT: Nonrandomized controlled trial: prospective comparative trial with allocation of patients by physician; Cohor: Prospective or retrospective observational study without allocation of patients by physician, start is intervention; CCS: Case-control study: retrospective study, start is events; Regist: Registry of data from patients with particular diseases or interventions; Admin: Administrative databases such as data from health care providers; Survey: Survey or audit or postmarketing analysis; Cases: Single case or case series

Other abbreviations. Ref: reference

Of the 15 methodological topics relevant for the integration of various study designs in systematic reviews, 5 topics were frequently reported by more than 10 articles (Table 3 ). The rest were addressed by 1 article or up to 6 articles. Validity was reported by 30 reviews (systematic 3, non-systematic 27), applicability by 21 reviews (systematic 6, non-systematic 15), confounding by 21 reviews (systematic 2, non-systematic 19), adverse events by 18 reviews (systematic 4, non-systematic 14), and long-term follow up by 15 reviews (systematic 4, non-systematic 11). Systematic reviews reported 13 categories leaving pathogenesis and rare diseases out. Non-systematic reviews reported 12 categories and did not refer to case load, specialisation, and survival.

Table 3. Outcomes of included articles.

| Authors |

Year

|

Ref |

Outcomes addressed

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Adherence | Adverse events | Applicability | Case-load | Confounding | Exclusions | Heterogeneity | Long term | Participation | Patho-physiol | Preferences | Rare disease | Special-isation | Survival | Validity | |||

| Systematic review | ||||||||||||||||||

| Archampong | 2012 | [14] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Britton | 1998 | [17] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Chambers | 2009 | [18] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Chambers | 2010 | [18] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Chou | 2010 | [20] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Lewsey | 2000 | [33] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Linde | 2002 | [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Norris | 2005 | [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Non-systematic review | ||||||||||||||||||

| Atkins | 2007 | [15] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Black | 1996 | [16] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Chumbler | 2008 | [21] | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Concato (Comp) | 2010 | [7] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Concato (Observ) | 2010 | [22] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Essock | 2003 | [23] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Fletcher | 2002 | [24] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Fletcher | 2009 | [25] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Gale | 2009 | [26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Grzeskowiak | 2012 | [27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Hadley | 2009 | [61] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Hartling | 2005 | [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Hodgson | 2007 | [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Hoppe | 2009 | [8] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Horn | 2010 | [31] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Kovesdy | 2012 | [32] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| McCarthy | 2008 | [35] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Mercer | 2007 | [36] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Mitchell | 1995 | [37] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Norris | 2011 | [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Ogilvie | 2005 | [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Olivier | 2006 | [41] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Reeves | 2005 | [42] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Rosendaal | 2001 | [43] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Sharma | 2012 | [44] | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Shrier | 2007 | [45] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Silverman | 2009 | [46] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 1998 | [47] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2004 | [48] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2008 | [5] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2009 | [49] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Vandenbroucke | 2011 | [50] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Wilcken | 2001 | [51] | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Zlowodzki | 2006 | [52] | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Frequency | 4 | 18 | 21 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 30 | |||

Outcomes addressed. Adherence: Patients may adhere to the prescription or may not take drugs or doses as wanted; Adverse events: Patients may experience unwanted effects or events that are associated with the intervention; Applicability: Results may not be generalized to patients that have different characteristics than the study population; Case load: the number of patients with a particular disease or intervention admitted to a hospital or treated by a physician; Confounding: A known or unknown factor that is associated with the intervention and influences the outcome; Exclusions: Certain patients are excluded from the recruitment such as elderly, pregnant women, children, patients with comorbidities; Heterogeneity: Patients within one treatment group differ in baseline characteristics such as severity of disease; Long term: follow up more than 12 months after the intervention; Participation: Eligible individuals who did not participate in trials; Pathophysiol: Pathophysiological issues such as bacterial cause or various genetic constitution; Preferences: Patients and physicians may have preferences about what treatment is best; Rare disease: Rare diseases may not be represented in clinical trials and rare adverse events may not be detected by small studies; Specialisation: the level of education and experience of a physician may influence the outcome: Survival: Proportion of patients that sustain a specific wanted status after a certain time period; Validity: to measure what should be measured; minimizing uncertainty and systematic error, dealing with selection bias

Other abbreviations. Ref: reference

Key messages

We qualitatively summarized the key messages of the 42 included methods studies based on the extraction of major statements (Table S2 ). We identified a clear tendency in the message that nonrandomized studies should be conducted and integrated in systematic reviews to complement available RCTs or replace lacking RCTs in 85% (36 of 42) of all reviews. We judged the difference between systematic reviews 75% (6 of 8) and non-systematic reviews 88% (30 of 34) as not considerable. Thus the majority of identified reviews supported the view that nonrandomized studies are important and should be an integral part of assessing health care interventions. Only a minority of reviews regarded RCTs as the sole means of finding reliable answers to clinical research questions. Most papers acknowledged the advantages and the disadvantages of RCTs and nonrandomized studies with regard to specific methodologic topics or specific clinical outcomes. Some papers addressed the problem that RCTs are not possible for assessing certain questions and that case reports may have a considerable impact on safety issues.

Comparison of randomized vs. nonrandomized controlled design

We identified 49 studies, 18 trials and 31systematic reviews that compared the effect measures found in randomized controlled trials with those in nonrandomized controlled trials (Table 4 ). Of these 49 studies, 39 reported about the same or similar intervention in both study designs and 10 studies that included different interventions in the analyses. In 35% (17 of 49) studies, there was a different direction or a statistically significant difference of the magnitude of effect between randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. In 53% (26 of 49) studies, the effect did not differ considerably between those two designs. In 12% (6 of 49) studies, both results, a difference as well as no difference were reported.

Table 4. Reviews and studies comparing randomized vs. nonrandomized controlled results.

| First author | Year | Ref | Intervention |

Difference R vs. N

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Various | No | ||||

| Abraham | 2010 | [62] | same | no | ||

| Algra | 2012 | [63] | same | no | ||

| Antman | 1985 | [64] | same | yes | ||

| Aslani | 2010 | [65] | same | no | ||

| Benis | 2002 | [66] | same | yes | ||

| Benson | 2000 | [67] | same | no | ||

| Bhandari | 2004 | [68] | same | yes | ||

| Britton | 1998 | [17] | same | no | ||

| Carroll | 1996 | [69] | same | yes | ||

| CASS | 1984 | [70] | same | no | ||

| Cheng | 2012 | [71] | same | no | ||

| Choi | 2012 | [72] | same | no | ||

| Clagett | 1984 | [73] | same | no | ||

| Colditz | 1989 | [74] | various | yes | ||

| Conaty | 2004 | [75] | same | no | ||

| Concato | 2000 | [76] | same | no | ||

| Deeks | 2003 | [77] | various | various | ||

| Edwards | 2012 | [78] | various | no | ||

| Flossman | 2007 | [79] | same | no | ||

| Franklin | 2000 | [80] | same | no | ||

| Furlan (Exam) | 2008 | [81] | same | various | ||

| Furlan (Meth) | 2008 | [82] | same | yes | ||

| Golder | 2011 | [83] | various | no | ||

| Gross | 2005 | [84] | same | no | ||

| Guyatt | 2000 | [85] | same | yes | ||

| Hannan | 2008 | [86] | various | various | ||

| Hlatky | 1988 | [87] | same | no | ||

| Ioannidis | 2001 | [58] | various | yes | ||

| Kunz | 2007 | [54] | same | yes | ||

| Kunz | 1998 | [53] | same | yes | ||

| Kuss | 2011 | [88] | same | no | ||

| Lawlor | 2004 | [89] | same | yes | ||

| Linde | 2002 | [34] | same | no | ||

| MacLehose | 2000 | [11] | various | no | ||

| Mueller | 2010 | [90] | same | yes | ||

| Naudet | 2011 | [91] | same | yes | ||

| Odgaard-Jensen | 2011 | [55] | various | various | ||

| Papanikolaou | 2006 | [92] | various | various | ||

| Phillips | 1999 | [93] | same | no | ||

| RMIT | 1994 | [94] | same | no | ||

| Rovers | 2001 | [95] | same | no | ||

| Schmoor | 2008 | [96] | same | no | ||

| Shea | 2010 | [97] | same | yes | ||

| Shikata | 2006 | [98] | various | various | ||

| Tzoulaki | 2011 | [99] | same | yes | ||

| Vis | 2008 | [100] | same | yes | ||

| Vist | 2008 | [101] | same | no | ||

| Wilkes | 2010 | [102] | same | no | ||

| Wolfe | 2004 | [103] | same | yes | ||

| Frequency | 17 | 6 | 26 | |||

Abbreviations: CASS: Coronary artery surgery study; Difference R vs N: difference between randomized vs. nonrandomized results; Ref: reference; RMIT: Recurrent Miscarriage Immunotherapy Trialists

Discussion

We identified and summarized qualitative evidence sufficient enough to guide finding and integrating the right research design for answering various clinical questions within the conduct of systematic reviews of health care interventions.

It is obvious that intended effects of interventions such as the physician-reported outcomes of prevention of death and healing or improving of disease in ideal settings with financially affordable follow up and with ample number of available participants are best investigated in well planned RCTs. There is no equal or better alternative study design. The results may or may not be applicable to the general population. Many people with particular characteristics such as younger or older age, gender, pregnancy, or comorbidity may have been excluded and may have experienced opposing effects or an unfavorable and unwanted balance of benefit and harm. Pediatricians may seek information on drugs from observational studies if data on the treatment of children from RCTs are not available. Unintended, severe adverse events require long-term observation including postmarketing analysis, administrative databases, and case reports to identify harmful drugs that have to be withdrawn from the market. The types of different study design that need to be included in a systematic review depend on the nature of the clinical questions that the review addresses.

Oxman and collaborators assessed the effects of randomisation and concealment of allocation on the results of healthcare studies and reported their results in three papers within the time period from 1998 to 2011 [53-55]. The authors concluded that "the results of randomised and non-randomised studies – sometimes – differed". In many cases the results did not differ. The authors argued "that it is not generally possible to predict the magnitude, or even the direction, of possible selection biases and consequent distortions of treatment effects from studies with non-random allocation or controlled trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment". We believe that trials with random allocation and adequate allocation concealment may show contradictory results. We also believe that it is not possible to foresee the magnitude or the direction of bias in those adequately randomized trials with absolute certainty [56]. Nevertheless, the authors stated that "randomized controlled trials are a safeguard against biased estimates of treatment effects". Various design prerequisites and adjustment procedures in nonrandomized controlled trials can minimize bias and confounding, however, it is not kown for certain in a particular trial whether the results reflect the reality or whether they are distorted. The same principle holds true for trials with adequate randomization and concealment of allocation. Even if the risk of a false estimate determined in a series of trials would be lower than in trials with inadequate randomization and concealment of allocation the fact is that the result of the primary outcome measure in a single specific trial cannot be regarded as an absolute and certain proof regardless of the p-values or confidence intervals. Ioannidis 2005 concluded that, quote: "Controversies are most common with highly cited nonrandomized studies, but even the most highly cited randomized trials may be challenged and refuted over time, especially small ones" [57]. The authors found that 5 of 6 highly cited nonrandomized studies had been contradicted or had found stronger effects versus 9 of 39 randomized controlled trials (P = 0.008). Our assessment adds to the existing work done by Oxman group and the Ioannidis group that the effect did not differ considerably between the randomized and the nonrandomized designs in more than half of the studies. The general postulate or dogma of the RCT as a safeguard against biased estimates of treatment effects may create deceptive promises and may give researchers a false sense of security. We infer from our findings just the same as Shrier 2007 has expressed before, quote: "(...)that excluding observational studies in systematic reviews a priori is inappropriate and internally inconsistent with an evidence-based approach" [45].

According to the Cochrane handbook, the Cochrane Collaboration focuses particularly on systematic reviews of RCTs and considers inclusion of nonrandomized studies mainly if RCTs are lacking. We see a vast number of clinical research questions that are not investigated by RCTs. There may be many reasons, for example, patients' and physicians' preferences that prevent the accumulation of true randomized study data. Our results suggest that the Cochrane Collaboration might be advised to consider more reasons for including nonrandomized studies on the condition of a rigorous risk of bias assessment and confinement to specific interventions and outcomes.

In general, a high risk of bias is inherent in all nonrandomized studies. Certain study characteristics such as prospective design, concurrent control group, adjustment of results with respect to different baseline values, and confounder control can limit additional bias. For example, Ioannidis 2001 [58] reported that discrepancies between RCT and nonrandomized studies were less common when only nonrandomized studies with a prospective design were considered. The Cochrane Collaboration offers a guide for inclusion of nonrandomized studies [59] and it has developed a tool for assessing the risk of bias in both RCT and controlled nonrandomized studies[60].

Conclusions

Different study designs addressing the same question yielded varying results, with differences in about half of all examples. The risk of presenting uncertain results without knowing for sure the direction and magnitude of the effect holds true for both nonrandomized and randomized controlled trials, though, the risk of bias and confounding is probably higher in the nonrandomized ones. The integration of multiple study designs in systematic reviews is required if patients should be informed on the many facets of patient relevant issues of health care interventions.

Supporting Information

PRISMA Checklist.

(DOC)

Qualitative summary of key messages. Type of review. Systematic review (first 8 papers): Cochrane Systematic Review (Archampong 2012), Health Technology Assessment of National Health Service in UK (Britton 1998), other systematic reviews not issued by Cochrane or HTA (Chambers 2009, Chambers 2010, Chou 2010, Lewsey 2000, Linde 2002, Norris 2005). Non-systematic review (rest of 34 papers): narrative review or editorial or comment or letter.

Message. We extracted messages with respect to the question whether nonrandomized studies should be conducted or integrated in systematic reviews to complement available RCTs or replace lacking RCTs. We did not extract data on differences between those two study design on size or direction of effect.

NRS also: We perceived a tendency in the message that nonrandomized studies should also be considered in addition to RCTs in general or to answer specific research questions.

RCT only: We perceived a tendency in the message that RCTs are sufficient to answer research questions in clinical trials and in systematic reviews and that nonrandomized studies cannot complement or replace them.

Field. Acupuncture: Intervention regarding acupuncture type of complementary and alternative medicine; Cardiology: Interventional procedures to reopen coronary arteries as opposed to surgical interventions; Genetics: Genetic diseases and rare diseases; HRT: Hormone replacement therapy for women; Mental: Intervention to treat a mental disease such as depression; Nephrology: Intevention regarding renal disease; Nutrition: Influence of food on health; Orthopedics: Intervention regarding orthopedic disease; Palliation: Intervention regarding palliative treatment; Pediatrics: Intervention regarding children; Pharma: Drugs to treat patients; Pregnancy: Intervention regarding pregnant women; Social: Complex social interventions; Surgery: Surgical intervention regarding various diseases; Tele: Intervention regarding telehealth issues; Transplant: Autologous or allogeneic transplantation of organs; Various: Two or more different clinical fields.

Other abbreviations. Ref: reference.

(DOCX)

Funding Statement

The University of Cologne provided the fulltexts. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Haynes B (1999) Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? The testing of health care interventions is evolving. BMJ 319: 652-653. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.652. PubMed: 10480802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Djulbegovic B, Paul A (2011) From efficacy to effectiveness in the face of uncertainty: indication creep and prevention creep. JAMA 305: 2005-2006. PubMed: 21586716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Victora CG, Habicht JP, Bryce J (2004) Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health 94: 400-405. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.400. PubMed: 14998803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Djulbegovic M, Djulbegovic B (2011) Implications of the principle of question propagation for comparative-effectiveness and "data mining" research. JAMA 305: 298-299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2013. PubMed: 21245185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vandenbroucke JP (2008) Observational research, randomised trials, and two views of medical science. PLoS Med 5: e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050067. PubMed: 18336067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CEBM (2009) Levels of evidence. Oxford: Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine; (CEBM; ). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Concato J, Peduzzi P, Huang GD, O'Leary TJ, Kupersmith J (2010) Comparative effectiveness research: what kind of studies do we need? J Investig Med 58: 764-769. PubMed: 20479661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoppe DJ, Schemitsch EH, Morshed S, Tornetta P 3rd, Bhandari M (2009) Hierarchy of evidence: where observational studies fit in and why we need them. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91 Suppl 3: 2-9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00549. PubMed: 19411493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. NCBI (2011) MeSH: Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) [Google Scholar]

- 10. NCBI (2011) MeSH: Epidemiologic Study Characteristics as Topic. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 11. MacLehose RR, Reeves BC, Harvey IM, Sheldon TA, Russell IT et al. (2000) A systematic review of comparisons of effect sizes derived from randomised and non-randomised studies. Health Technol Assess 4: 1-154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pibouleau L, Boutron I, Reeves BC, Nizard R, Ravaud P (2009) Applicability and generalisability of published results of randomised controlled trials and non-randomised studies evaluating four orthopaedic procedures: methodological systematic review. BMJ 339: b4538. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4538. PubMed: 19920015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fraser C, Murray A, Burr J (2006) Identifying observational studies of surgical interventions in MEDLINE and EMBASE. BMC Med Res Methodol 6: 41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-41. PubMed: 16919159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Archampong D, Borowski D, Wille-Jørgensen P, Iversen LH (2012) Workload and surgeon's specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD005391: CD005391 PubMed: 22419309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Atkins D (2007) Creating and synthesizing evidence with decision makers in mind: integrating evidence from clinical trials and other study designs. Med Care 45: S16-S22. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c3f. PubMed: 17909376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Black N (1996) Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ 312: 1215-1218. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1215. PubMed: 8634569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Britton A, McKee M, Black N, McPherson K, Sanderson C et al. (1998) Choosing between randomised and non-randomised studies: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2: 1-iv. 9793791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chambers D, Rodgers M, Woolacott N (2009) Not only randomized controlled trials, but also case series should be considered in systematic reviews of rapidly developing technologies. J Clin Epidemiol 62: 1253-1260 e1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chambers D, Fayter D, Paton F, Woolacott N (2010) Use of non-randomised evidence alongside randomised trials in a systematic review of endovascular aneurysm repair: strengths and limitations. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 39: 26-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.09.010. PubMed: 19836274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chou R, Aronson N, Atkins D, Ismaila AS, Santaguida P et al. (2010) AHRQ series paper 4: assessing harms when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol 63: 502-512. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.007. PubMed: 18823754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chumbler NR, Kobb R, Brennan DM, Rabinowitz T (2008) Recommendations for research design of telehealth studies. Telemed J E Health 14: 986-989. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0108. PubMed: 19035813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Concato J, Lawler EV, Lew RA, Gaziano JM, Aslan M et al. (2010) Observational methods in comparative effectiveness research. Am J Med 123: e16-e23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.04.014. PubMed: 21184862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Essock SM, Drake RE, Frank RG, McGuire TG (2003) Randomized controlled trials in evidence-based mental health care: getting the right answer to the right question. Schizophr Bull 29: 115-123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006981. PubMed: 12908666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fletcher RH (2002) Evaluation of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 55: 1183-1190. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00525-5. PubMed: 12547447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fletcher AE (2009) Controversy over "contradiction": Should randomized trials always trump observational studies? Am J Ophthalmol 147: 384-386. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.024. PubMed: 19217953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gale RP, Eapen M, Logan B, Zhang MJ, Lazarus HM (2009) Are there roles for observational database studies and structured quantification of expert opinion to answer therapy controversies in transplants? Bone Marrow Transplant 43: 435-446. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.447. PubMed: 19182830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grzeskowiak LE, Gilbert AL, Morrison JL (2012) Investigating outcomes associated with medication use during pregnancy: a review of methodological challenges and observational study designs. Reprod Toxicol 33: 280-289. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.01.006. PubMed: 22329969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hadley J, Yabroff KR, Barrett MJ, Penson DF, Saigal CS et al. (2010) Comparative effectiveness of prostate cancer treatments: evaluating statistical adjustments for confounding in observational data. J Natl Cancer Inst 102: 1780-1793. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq393. PubMed: 20944078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hartling L, McAlister FA, Rowe BH, Ezekowitz J, Friesen C et al. (2005) Challenges in systematic reviews of therapeutic devices and procedures. Ann Intern Med 142: 1100-1111. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_Part_2-200506211-00010. PubMed: 15968035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hodgson R, Bushe C, Hunter R (2007) Measurement of long-term outcomes in observational and randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 50: s78-s84. PubMed: 18019049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Horn SD, Gassaway J, Pentz L, James R (2010) Practice-based evidence for clinical practice improvement: an alternative study design for evidence-based medicine. Stud Health Technol Inform 151: 446-460. PubMed: 20407178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K (2012) Observational studies versus randomized controlled trials: avenues to causal inference in nephrology. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 19: 11-18. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.09.004. PubMed: 22364796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lewsey JD, Leyland AH, Murray GD, Boddy FA (2000) Using routine data to complement and enhance the results of randomised controlled trials. Health Technol Assess 4: 1-55. PubMed: 11074392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Linde K, Scholz M, Melchart D, Willich SN (2002) Should systematic reviews include non-randomized and uncontrolled studies? The case of acupuncture for chronic headache. J Clin Epidemiol 55: 77-85. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00422-X. PubMed: 11781125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCarthy CM, Collins ED, Pusic AL (2008) Where do we find the best evidence? Plast Reconstr Surg 122: 1942-1951; discussion: 19050548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mercer SL, DeVinney BJ, Fine LJ, Green LW, Dougherty D (2007) Study designs for effectiveness and translation research: identifying trade-offs. Am J Prev Med 33: 139-154. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.005. PubMed: 17673103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mitchell AA, Lesko SM (1995) When a randomised controlled trial is needed to assess drug safety. The case of paediatric ibuprofen. Drug Saf 13: 15-24. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199513010-00003. PubMed: 8527016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Norris SL, Atkins D (2005) Challenges in using nonrandomized studies in systematic reviews of treatment interventions. Ann Intern Med 142: 1112-1119. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_Part_2-200506211-00011. PubMed: 15968036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Norris SL, Atkins D, Bruening W, Fox S, Johnson E et al. (2011) Observational studies in systemic reviews of comparative effectiveness: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol 64: 1178-1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.027. PubMed: 21636246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ogilvie D, Egan M, Hamilton V, Petticrew M (2005) Systematic reviews of health effects of social interventions: 2. Best available evidence: how low should you go? J Epidemiol Community Health 59: 886-892. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.034199. PubMed: 16166365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Olivier P, Montastruc JL (2006) The nature of the scientific evidence leading to drug withdrawals for pharmacovigilance reasons in France. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 15: 808-812. doi: 10.1002/pds.1248. PubMed: 16700082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reeves BC, van Binsbergen J, van Weel C (2005) Systematic reviews incorporating evidence from nonrandomized study designs: reasons for caution when estimating health effects. Eur J Clin Nutr 59 Suppl 1: S155-S161. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602049. PubMed: 16052184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosendaal FR (2001) Bridging case-control studies and randomized trials. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med 2: 109-110. doi: 10.1186/CVM-2-3-109. PubMed: 11806781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sharma V, Minhas R (2012) Explanatory models are needed to integrate RCT and observational data with the patient's unique biology. J R Soc Med 105: 11-24. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110236. PubMed: 22275494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shrier I, Boivin JF, Steele RJ, Platt RW, Furlan A et al. (2007) Should meta-analyses of interventions include observational studies in addition to randomized controlled trials? A critical examination of underlying principles. Am J Epidemiol 166: 1203-1209. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm189. PubMed: 17712019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Silverman SL (2009) From randomized controlled trials to observational studies. Am J Med 122: 114-120. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.030. PubMed: 19185083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vandenbroucke JP (1998) Observational research and evidence-based medicine: What should we teach young physicians? J Clin Epidemiol 51: 467-472. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00025-0. PubMed: 9635995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vandenbroucke JP (2004) When are observational studies as credible as randomised trials? Lancet 363: 1728-1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16261-2. PubMed: 15158638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vandenbroucke JP (2009) The HRT controversy: observational studies and RCTs fall in line. Lancet 373: 1233-1235. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60708-X. PubMed: 19362661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vandenbroucke JP (2011) Why do the results of randomised and observational studies differ? BMJ 343: d7020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7020. PubMed: 22065658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilcken B (2001) Rare diseases and the assessment of intervention: what sorts of clinical trials can we use? J Inherit Metab Dis 24: 291-298. doi: 10.1023/A:1010387522195. PubMed: 11405347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zlowodzki M, Jonsson A, Bhandari M (2006) Common pitfalls in the conduct of clinical research. Med Princ Pract 15: 1-8. doi: 10.1159/000089379. PubMed: 16340221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kunz R, Oxman AD (1998) The unpredictability paradox: review of empirical comparisons of randomised and non-randomised clinical trials. BMJ 317: 1185-1190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1185. PubMed: 9794851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kunz R, Vist G, Oxman AD (2007) Randomisation to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: MR: 000012 PubMed: 2149141517443633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Odgaard-Jensen J, Vist GE, Timmer A, Kunz R, Akl EA et al. (2011) Randomisation to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: MR: 000012 PubMed: 21491415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Savović J, Jones HE, Altman DG, Harris RJ, Jüni P et al. (2012) Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 157: 429-438. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00537. PubMed: 22945832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ioannidis JP (2005) Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited clinical research. JAMA 294: 218-228. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.218. PubMed: 16014596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ioannidis JP, Haidich AB, Pappa M, Pantazis N, Kokori SI et al. (2001) Comparison of evidence of treatment effects in randomized and nonrandomized studies. JAMA 286: 821-830. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.7.821. PubMed: 11497536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Wells GA (2011) Chapter 13: Including non-randomized studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510 [updated March 2011]. Oxford, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration [Google Scholar]

- 60. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (2011) Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510 [updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hadley G, Derry S, Moore RA, Wee B (2009) Can observational studies provide a realistic alternative to randomized controlled trials in palliative care? J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 23: 106-113. doi: 10.1080/15360280902899921. PubMed: 19492211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Abraham NS, Byrne CJ, Young JM, Solomon MJ (2010) Meta-analysis of well-designed nonrandomized comparative studies of surgical procedures is as good as randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 63: 238-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.04.005. PubMed: 19716267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Algra AM, Rothwell PM (2012) Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. Lancet Oncol 13: 518-527. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2. PubMed: 22440112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Antman K, Amato D, Wood W, Carson J, Suit H et al. (1985) Selection bias in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 3: 1142-1147. PubMed: 4020412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Aslani N, Brown CJ (2010) Does mesh offer an advantage over tissue in the open repair of umbilical hernias? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia 14: 455-462. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0705-9. PubMed: 20635190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Benis MM (2002) Are pacifiers associated with early weaning from breastfeeding? Adv Neonatal Care 2: 259-266. doi: 10.1016/S1536-0903(02)70003-9. PubMed: 12881939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Benson K, Hartz AJ (2000) A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med 342: 1878-1886. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422506. PubMed: 10861324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bhandari M, Tornetta P 3rd, Ellis T, Audige L, Sprague S et al. (2004) Hierarchy of evidence: differences in results between non-randomized studies and randomized trials in patients with femoral neck fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 124: 10-16. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0559-z. PubMed: 14576955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Carroll D, Tramèr M, McQuay H, Nye B, Moore A (1996) Randomization is important in studies with pain outcomes: systematic review of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in acute postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth 77: 798-803. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.6.798. PubMed: 9014639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.(1984) Coronary artery surgery study (CASS): a randomized trial of coronary artery bypass surgery. Comparability of entry characteristics and survival in randomized patients and nonrandomized patients meeting randomization criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 3: 114-128. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(84)80437-4. PubMed: 6361099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cheng Y, Xiong XZ, Wu SJ, Lin YX, Cheng NS (2012) Laparoscopic vs. open cholecystectomy for cirrhotic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology 59: 1727-1734. PubMed: 22193435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Choi HJ, Hahn S, Lee J, Park BJ, Lee SM et al. (2012) Surfactant lavage therapy for meconium aspiration syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neonatology 101: 183-191. doi: 10.1159/000329822. PubMed: 22067375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Clagett GP, Youkey JR, Brigham RA, Orecchia PM, Salander JM et al. (1984) Asymptomatic cervical bruit and abnormal ocular pneumoplethysmography: a prospective study comparing two approaches to management. Surgery 96: 823-830. PubMed: 6387988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Colditz GA, Miller JN, Mosteller F (1989) How study design affects outcomes in comparisons of therapy. I: Medical. Stat Med 8: 441-454. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080408. PubMed: 2727468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Conaty S, Watson L, Dinnes J, Waugh N (2004) The effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines in adults: a systematic review of observational studies and comparison with results from randomised controlled trials. Vaccine 22: 3214-3224. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.050. PubMed: 15297076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI (2000) Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med 342: 1887-1892. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. PubMed: 10861325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C et al. (2003) Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess 7: iii-iix, 1-173 PubMed: 14499048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Edwards JP, Kelly EJ, Lin Y, Lenders T, Ghali WA et al. (2012) Meta-analytic comparison of randomized and nonrandomized studies of breast cancer surgery. Can J Surg 55: 155-162. doi: 10.1503/cjs.023410. PubMed: 22449722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Flossmann E, Rothwell PM, British Doctors Aspirin T, the UKTIAAT (2007) Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies. Lancet 369: 1603-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Kozak MJ, Levitt JT, Foa EB (2000) Effectiveness of exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized compared with nonrandomized samples. J Consult Clin Psychol 68: 594-602. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.594. PubMed: 10965635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Furlan AD, Tomlinson G, Jadad AA, Bombardier C (2008) Examining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: comparing results of randomized trials and nonrandomized studies of interventions for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33: 339-348. PubMed: 18303468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Furlan AD, Tomlinson G, Jadad AA, Bombardier C (2008) Methodological quality and homogeneity influenced agreement between randomized trials and nonrandomized studies of the same intervention for back pain. J Clin Epidemiol 61: 209-231. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.019. PubMed: 18226744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Golder S, Loke YK, Bland M (2011) Meta-analyses of adverse effects data derived from randomised controlled trials as compared to observational studies: methodological overview. PLoS Med 8: e1001026 PubMed: 21559325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gross CP, Garg PP, Krumholz HM (2005) The generalizability of observational data to elderly patients was dependent on the research question in a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 58: 130-137. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.001. PubMed: 15680745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Guyatt GH, DiCenso A, Farewell V, Willan A, Griffith L (2000) Randomized trials versus observational studies in adolescent pregnancy prevention. J Clin Epidemiol 53: 167-174. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00160-2. PubMed: 10729689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hannan EL (2008) Randomized clinical trials and observational studies: guidelines for assessing respective strengths and limitations. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 1: 211-217. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.01.008. PubMed: 19463302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hlatky MA, Califf RM, Harrell FE Jr., Lee KL, Mark DB et al. (1988) Comparison of predictions based on observational data with the results of randomized controlled clinical trials of coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 11: 237-245. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90086-1. PubMed: 3276752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kuss O, Legler T, Börgermann J (2011) Treatments effects from randomized trials and propensity score analyses were similar in similar populations in an example from cardiac surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 64: 1076-1084. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.005. PubMed: 21482068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Kundu D, Bruckdorfer KR, Ebrahim S (2004) Those confounded vitamins: what can we learn from the differences between observational versus randomised trial evidence? Lancet 363: 1724-1727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16260-0. PubMed: 15158637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Müeller D, Sauerland S, Neugebauer EA, Immenroth M (2010) Reported effects in randomized controlled trials were compared with those of nonrandomized trials in cholecystectomy. J Clin Epidemiol 63: 1082-1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.009. PubMed: 20346627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Naudet F, Maria AS, Falissard B (2011) Antidepressant response in major depressive disorder: a meta-regression comparison of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. PLOS ONE 6: e20811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020811. PubMed: 21687681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Papanikolaou PN, Christidi GD, Ioannidis JP (2006) Comparison of evidence on harms of medical interventions in randomized and nonrandomized studies. CMAJ 174: 635-641. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050873. PubMed: 16505459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Phillips AN, Grabar S, Tassie JM, Costagliola D, Lundgren JD et al. (1999) Use of observational databases to evaluate the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: comparison of cohort studies with randomized trials. EuroSIDA, the French Hospital Database on HIV and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study Groups. AIDS 13: 2075-2082. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910220-00010. PubMed: 10546860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.(1994) Worldwide collaborative observational study and meta-analysis on allogenic leukocyte immunotherapy for recurrent spontaneous abortion. Recurrent Miscarriage Immunotherapy Trialists Group. Am J Reprod Immunol 32: 55-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Rovers MM, Straatman H, Ingels K, van der Wilt GJ, van den Broek P et al. (2001) Generalizability of trial results based on randomized versus nonrandomized allocation of OME infants to ventilation tubes or watchful waiting. J Clin Epidemiol 54: 789-794. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00340-7. PubMed: 11470387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Schmoor C, Caputo A, Schumacher M (2008) Evidence from nonrandomized studies: a case study on the estimation of causal effects. Am J Epidemiol 167: 1120-1129. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn010. PubMed: 18334500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Shea MK, Houston DK, Nicklas BJ, Messier SP, Davis CC et al. (2010) The effect of randomization to weight loss on total mortality in older overweight and obese adults: the ADAPT Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65: 519-525. PubMed: 20080875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Shikata S, Nakayama T, Noguchi Y, Taji Y, Yamagishi H (2006) Comparison of effects in randomized controlled trials with observational studies in digestive surgery. Ann Surg 244: 668-676. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225356.04304.bc. PubMed: 17060757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Tzoulaki I, Siontis KC, Ioannidis JP (2011) Prognostic effect size of cardiovascular biomarkers in datasets from observational studies versus randomised trials: meta-epidemiology study. BMJ 343: d6829. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6829. PubMed: 22065657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Vis AN, Roemeling S, Reedijk AM, Otto SJ, Schröder FH (2008) Overall survival in the intervention arm of a randomized controlled screening trial for prostate cancer compared with a clinically diagnosed cohort. Eur Urol 53: 91-98. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.06.001. PubMed: 17583416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Vist GE, Bryant D, Somerville L, Birminghem T, Oxman AD (2008) Outcomes of patients who participate in randomized controlled trials compared to similar patients receiving similar interventions who do not participate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: MR: 000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wilkes MM, Navickis RJ, Chan WW, Lewiecki EM (2010) Bisphosphonates and osteoporotic fractures: a cross-design synthesis of results among compliant/persistent postmenopausal women in clinical practice versus randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 21: 679-688. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0991-1. PubMed: 19572092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Wolfe F, Michaud K, Dewitt EM (2004) Why results of clinical trials and observational studies of antitumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy differ: methodological and interpretive issues. Ann Rheum Dis 63 Suppl 2: ii13-ii17. PubMed: 15479864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA Checklist.

(DOC)

Qualitative summary of key messages. Type of review. Systematic review (first 8 papers): Cochrane Systematic Review (Archampong 2012), Health Technology Assessment of National Health Service in UK (Britton 1998), other systematic reviews not issued by Cochrane or HTA (Chambers 2009, Chambers 2010, Chou 2010, Lewsey 2000, Linde 2002, Norris 2005). Non-systematic review (rest of 34 papers): narrative review or editorial or comment or letter.

Message. We extracted messages with respect to the question whether nonrandomized studies should be conducted or integrated in systematic reviews to complement available RCTs or replace lacking RCTs. We did not extract data on differences between those two study design on size or direction of effect.

NRS also: We perceived a tendency in the message that nonrandomized studies should also be considered in addition to RCTs in general or to answer specific research questions.

RCT only: We perceived a tendency in the message that RCTs are sufficient to answer research questions in clinical trials and in systematic reviews and that nonrandomized studies cannot complement or replace them.

Field. Acupuncture: Intervention regarding acupuncture type of complementary and alternative medicine; Cardiology: Interventional procedures to reopen coronary arteries as opposed to surgical interventions; Genetics: Genetic diseases and rare diseases; HRT: Hormone replacement therapy for women; Mental: Intervention to treat a mental disease such as depression; Nephrology: Intevention regarding renal disease; Nutrition: Influence of food on health; Orthopedics: Intervention regarding orthopedic disease; Palliation: Intervention regarding palliative treatment; Pediatrics: Intervention regarding children; Pharma: Drugs to treat patients; Pregnancy: Intervention regarding pregnant women; Social: Complex social interventions; Surgery: Surgical intervention regarding various diseases; Tele: Intervention regarding telehealth issues; Transplant: Autologous or allogeneic transplantation of organs; Various: Two or more different clinical fields.

Other abbreviations. Ref: reference.

(DOCX)