Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) produced by the oxidative burst in activated macrophages and neutrophils cause oxidative stress-implicated diseases. Quercetin is flavonoid that occurs naturally in plants and is widely used as a nutritional supplement due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. In this study, we investigated antioxidant activities and mechanisms of action in zymosan-induced macrophages of quercetin and quercetin-related flavonoids such as quercitrin, isoquercitrin, quercetin 3-O-β-(2″-galloyl)-rhamnopyranoside (QGR) and quercetin 3-O-β-(2″-galloyl)-glucopyranoside (QGG) as well as gallic acid, a building moiety of QGR and QGG. QGR and QGG exhibited stronger antioxidant activities compared with quercetin, whereas quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid exhibited weak-to-no antioxidant activities, assessed by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging, superoxide production, superoxide scavenging, nitric oxide (NO) production, peroxynitrite (ONOO−) scavenging and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity. Regarding mechanisms, the quercetin-containing flavonoids QGR and QGG differentially targeted compared with quercetin in the NF-κB signaling pathway that inhibited the DNA binding activity of the NF-κB complex without affecting the degradation and phosphorylation of IκBα and NF-κB phosphorylation. In addition, QGR and QGG inhibited CRE and activator protein (AP-1) transcriptional activity and JNK phosphorylation by inhibiting the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling in a different manner than quercetin. Our results showed that although QGR and QGG exhibited stronger antioxidant activities than quercetin in macrophages, their mechanisms of action in terms of the NF-κB, PKA and PKC signaling pathways were different.

Keywords: antioxidant, NF-κB/CRE/AP-1, quercetin, ROS/RNS, structurally related compounds

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) can be produced continually as a natural byproduct of the cellular metabolism when oxygen and nitrogen interact with certain molecules. These molecules play important roles in cellular signaling and homeostasis, which protect the human body against bacteria and viruses. Immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils activated by either internal stimuli or environmental stressors, release excess amounts of ROS and RNS such as the superoxide radical anion (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (OH•), nitric oxide (NO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) due to activation of NADH/NADPH oxidase, 5-lipoxygenase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the mitochondria (Trachootham et al., 2008). This may result in noxious effects on cells by direct interaction with cellular macromolecules such as DNA, RNA, lipids and proteins; the damage caused by the free radicals is reported in the etiology of several diseases (Lee and Kang, 2013; Rahman et al., 2012; Valko et al., 2007).

A number of antioxidants are used to neutralize and eliminate harmful activities of ROS and RNS through different ways to protect the human body. Naturally occurring polyphenols are present in fruits, vegetables, and other nutrient-rich plant foods and are widely used for prevention of oxidative stress-related diseases due to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (Pandey and Rizvi, 2009; Park et al., 2012). Quercetin is a prominent plant-derived flavonoid compound found in fruits, vegetables, leaves and grains and is widely used as an ingredient in supplements, beverages and foods for the potential health benefits due to its antioxidant (Boots et al., 2008a; Zhang et al., 2011a), anti-inflammatory (Boots et al., 2008b; Rogerio et al., 2007), neuropharmacological actions (Lee et al., 2005; 2010), anti-viral (Chen et al., 2006; Davis et al., 2008) and anti-cancer (Hirpara et al., 2009; Puoci et al., 2012) properties.

Zymosan is an insoluble substance derived from the cell walls of yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is composed mainly of β-glucan and mannan residues (Di Carlo and Fiore, 1958). Zymosan is recognized and phagocytosed by macrophages, monocytes, leukotriens (LTs) and complements in the absence of immunoglobulins and leads to cellular activation, which stimulates secretion of many inflammatory products such as prostaglandins (PGs), LTs, cytokines, chemokines, and oxygen radicals (Volman et al., 2005). In addition, zymosan induces inflammatory signals by binding with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) after phagocytosis by macrophages, and the signals are prolonged because they are not degraded and can be enhanced by the use of mineral oil as a carrier (Sato et al., 2003).

Many of the bioflavonoids derived from plants contain the quercetin moiety as their core structure, which forms the glycosides with glucose or rhamnose. Among the quercetin-related bioflavonoids, quercitrin (quercetin 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside) and isoquercitrin (quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside) have quercetin and either rhamnose or glucose as the glycoside moieties, respectively. Quercetin 3-O-β-(2″-galloyl)-rhamnopyranoside (QGR) and quercetin 3-O-β-(2″-galloyl)-glucopyranoside (QGG) were first isolated from the aerial parts of Polygonum salicifolium and Persicaria lapathifolia (Calis et al., 1999; Park et al., 1999), and contain gallic acid as their building block with either a quercitrin or isoquercitrin moiety, respectively (Kim et al., 2000). In this study, we found that QGR and QGG exhibited significant stronger antioxidant activity compared with their aglycone core structure (quercetin) and their building blocks (quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid) in zymosan-stimulated macrophages. In addition, both compounds exhibited anti-inflammatory activity through inhibition of the nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), protein kinase A (PKA) and C (PKC) signaling pathways in zymosan-stimulated macrophages. However, the inhibitory action of QGR and QGG on their signaling was mediated by mechanisms distinct from those of quercetin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds and reagents

Quercetin, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). QGR and QGG were isolated from the aerial parts of Persicaria lapathifolia (Polygonaceae) as previously described (Kim et al., 2000). These compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and kept at −20°C after aliquots. Antibodies specific for phospho-IκBα, phospho-NF-κB p65, phospho-JNK, JNK, phospho-ERK, ERK, iNOS and GAPDH were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). Phospho-p47phox and p47phox antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and IκBα antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA), respectively. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody was obtained from Life Technologies (USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), unless otherwise noted.

Cell culture

Mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells (ATCC# TIB-71) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, Invitrogen, USA). The cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 atmosphere in a humidified incubator. The RAW264.7 cells harboring pNF-κB-SEAP-NPT reporter construct (a gift from Dr. Kim YS, Seoul National University, Korea) were incubated in the same conditions with RAW264.7 cells except supplemented with 500 μg/ml of geneticin to the media.

Measurement of DPPH radical scavenging activity

Reaction mixture was prepared by mixing with 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, 200 μM, 100 μl) solution and various concentrations of each compound (100 μl). The mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader.

Measurement of superoxide production

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a white 96-well plate at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well. After incubation for 30 min, the cells were pretreated with various concentrations of each compound for 5 min in the presence of lucigenin (25 μM) and subsequently stimulated with either unopsonized zymosan (0.3 mg/ml) or PMA (0.1 μg/ml). Superoxide production was immediately measured by lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence as relative light units (RLU) at 37°C in the dark for 2 h with 5 min intervals for zymosan challenge or 30 min with 90 sec intervals for PMA challenge, respectively.

Measurement of superoxide scavenging activity

Superoxide was produced in NADH/PMS/NBT system. Solutions containing nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT, 100 μM) and phenazine methosulfate (PMS, 30 μM) dissolved in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) were mixed with various concentrations of each compound. Reaction was started by adding nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH, 150 mM). After incubation at 25°C for 5 min, the absorbance was measured at 560 nm against control samples as without NADH.

Measurement of NO production

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a 12-well plate at a density of 5 ×105 cells per well. After overnight, cells were treated with various concentrations of each compound in the presence or absence of zymosan (0.3 mg/ml) for 24 h. Amounts of nitric oxide in the cultured supernatants were reacted with Griess reagents, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader.

Measurement of peroxynitrite production

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 2.5 ×105 cells per well. After overnight, cells were treated with various concentrations of each compound in the presence or absence of zymosan for 24 h. The cells were further incubated with dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR 123, 15 μM) and diethyl-enetriaminepentaacetic acid (0.1 mM) for 1 h. Amounts of peroxynitrite were measured as relative fluorescence units (RFU) with emission at 530 nm and excitation at 485 nm.

Measurement of myeloperoxidase activity

Peritoneal neutrophils were isolated from rat peritoneal lavage after intraperitoneal injection with 1% casein in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer for 15 h. The cell lysates (20 μl) were mixed with substrate buffer (100 μl) containing citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.0, 50 ml, 30% H2O2 20 μl and O-phenylenediamine 20 mg) and incubated with various concentrations of each compound for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by addition with H2SO4 and the absorbance was measured with a microplate reader at 485 nm against control samples as without H2O2.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Cell pellets were lyzed for 30 min at 4°C in a Triton lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 350 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, and insoluble proteins were removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Whole-cell extracts were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (EMD Millipore Corporation, USA). The membranes were blocked for 1 h in a blocking buffer containing 5% skim-milk and then incubated with specific primary antibodies for target molecules at 4°C for overnight. After washing with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T), the signals were detected using an ECL detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, USA) followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

NF-κB binding site containing oligonucleotide (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) was 32P-end labeled using [γ-32P] ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega, USA) at 37°C for 10 min. Nuclear extracts (10 μg) were incubated with binding buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 50 μg/ml poly(dI-dC), 4% glycerol, and [γ-32P]-labeled NF-κB oligonucleotide on ice for 20 min. The protein-DNA complexes were separated on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel, and dried gels were exposed to X-ray films at −80°C.

Measurement of secreted alkaline phosphatase activity

RAW264.7 cells harboring pNF-κB-SEAP-NPT reporter construct encoding four copies of κB sequence and secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene as a reporter were pretreated with each compound for 1 h and stimulated with zymosan for 24 h. The cultured supernatants were heated at 65°C for 5 min and reacted with assay buffer (2 M diethanolamine, 1 mM MgCl2) and substrate (0.5 mM 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate) in the dark at 37°C for 1 h. SEAP activity was measured as relative fluorescence units (RFUs) with emission 449 nm and excitation 360 nm. Cis-acting response element vectors containing either pCRE-SEAP, pAP-1-SEAP, pSRE-SEAP or pNFAT-SEAP plasmid (Clontech Laboratories, USA) were transiently transfected in RAW264.7 cells. After 24 h, the cells were pre-treated with each compound for 1 h and stimulated with zymosan for 24 h. SEAP activity was measured using cultured supernatants.

Cell-free kinase assay

Cell-free cAMP-dependent PKA and PKC activities were measured using a PepTag® Non-Radioactive Protein Kinase Assay kits (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, purified PKA or PKC (10 ng) was activated by addition with either cAMP (500 nM) or phosphatidylserine (100 μg/ml) and incubated with either PKA-specific peptide substrate L-R-R-A-S-L-G or PKC-specific peptide substrate P-L-S-R-T-L-S-V-A-A-K, respectively, in the presence or absence of each compound at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were separated on agarose gel and then visualized under UV irradiation followed by heating at 95°C for 10 min.

Cell viability assay

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well plate at a density of 20,000 cells per well. After overnight, the cells were incubated with either DMSO as a vehicle or various concentrations of compounds for 24 h. The cell viability was measured by EZ-CyTox Enhanced Cell Viability Assay Kit (Daeil Lab Service, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocols using a microplate reader (BioTek, USA) at wavelength of 450 nm after reaction for 2 to 4 h at 37°C incubator followed by addition with 10 μl assay reagent in a well.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from independent experiments were expressed as mean ± standard error of means (SEM). Statistical analysis of differences among groups was determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant at a level of p < 0.001 or p < 0.05.

RESULTS

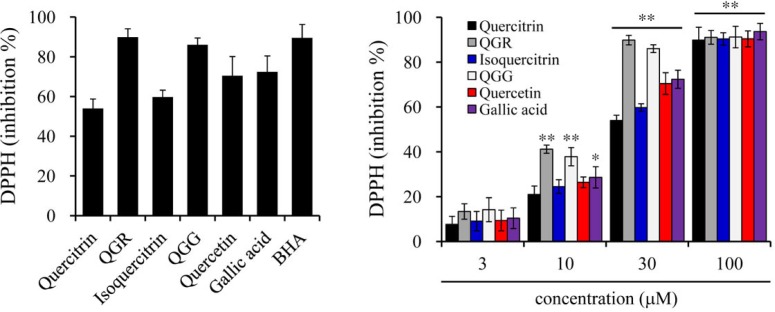

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on DPPH radical scavenging

Quercetin and many flavonoids containing the quercetin moiety are known for their antioxidant properties. To investigate the antioxidant potential of quercetin and its structurally-related flavonoids such as quercitrin, isoquercitrin, QGR and QGG as well as gallic acid, a building moiety of QGR and QGG (Fig. 1), we first evaluated the DPPH radical scavenging activity. QGR and QGG scavenged nearly 90% of the DPPH radical at a concentration of 30 μM, which was slightly greater than quercetin and the DPPH radical scavenger BHA, respectively. However, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid, a building moiety of QGR and QGG, exhibited weaker antioxidant activity than QGR and QGG (Fig. 2A). The DPPH radical scavenging activities of all compounds increased in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2B), but did not affect cell proliferation at the concentrations tested (Supplementary Fig. S1).

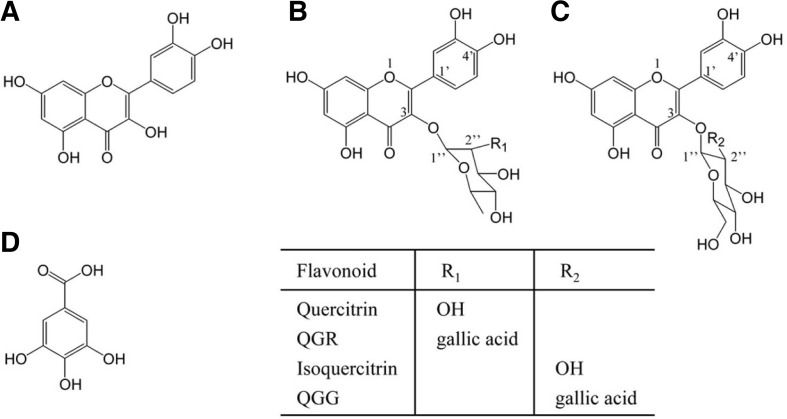

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of quercetin and structurally related compounds. Quercetin (A), quercitrin and QGR (B), isoquercitrin and QGG (C), and gallic acid (D). QGR and QGG contain quercetin and gallic acid as well as either rhamnose or glucose as a glycoside in their structures, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Effects of quercetin and structurally related compounds on DPPH radical. Compounds were mixed with DPPH solution and the mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 30 min. DPPH radical scavenging activity was measured as absorbance at 517 nm, and the results were represented as inhibition % at 30 μM (A) and concentration-dependent manner (B). BHA was used as a positive control. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 versus the vehicle group.

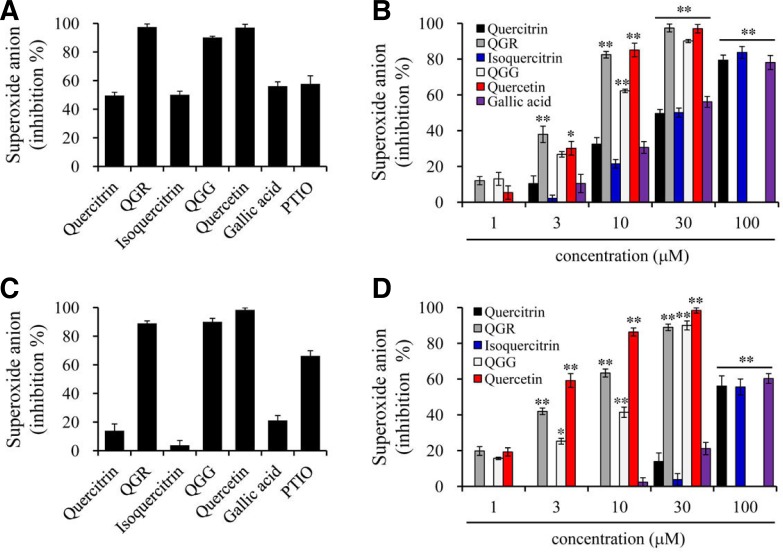

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on superoxide production

We next investigated whether quercetin and its structurally related compounds could affect NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide production in either zymosan-or PMA-stimulated macrophages. When macrophage RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with zymosan, superoxide production was immediately increased to a peak at 15 min and gradually decreased to basal levels within 2 h (data not shown). QGR, QGG and quercetin inhibited superoxide production almost completely at a concentration of 30 μM in zymosan-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, whereas treatment with quercitrin, isoquercitrin or gallic acid resulted in ∼50% inhibition (Fig. 3A). In the concentration-dependent study, at a concentration of 10 μM, the inhibitory activities of QGR and quercetin were over 80% and that of QGG was 60%. Quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid showed weaker inhibitory activities than QGR, QGG and quercetin in zymosan-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on superoxide production in macrophages. RAW264.7 cells were pre-treated with compounds for 30 min and stimulated with zymosan (A, B) or PMA (C, D). Amounts of superoxide production were measured as relative light units, and the results were represented as inhibition % at 30 μM (A, C) and concentration-dependent manner (B, D). PTIO was used as a positive control. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **p < 0.001 and *p. < 0.05 versus either the zymosan or PMA-stimulated group.

In PMA-induced RAW264.7 cells, superoxide production increased immediately to a peak within 5 min and decreased gradually to basal levels within 30 min (data not shown). Comparable with zymosan-stimulated superoxide production, QGR, QGG or quercetin treatment inhibited superoxide production almost completely at a concentration of 30 μM, whereas quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid had no significant effects on the production (Fig. 3C). The inhibitory potentials of QGR, QGG and quercetin on superoxide production were similar to those of zymosan and PMA, and significantly stronger than PTIO, a stable ROS and NO scavenger. However, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid exhibited weak inhibitory activities in PMA-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3D).

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on superoxide scavenging

To determine whether quercetin and its structurally related compounds have ROS scavenging activities, we performed a non-enzymatic assay of superoxide radicals and assessed their scavenging activities. Superoxide radicals were generated in the presence of PMS and NADH by reaction with oxygen in the air and immediately formed formazan by reduction of NBT. QGR and QGG exhibited a similar scavenging effect against superoxide radicals at high concentrations (100 μM). The positive control, PTIO, showed greater superoxide-scavenging activity than QGR and QGG. However, other compounds, including quercetin, did not exhibit superoxide scavenging potential (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on superoxide production. Superoxide was produced by NADH/PMS/NBT system and the scavenging activity was measured as absorbance at 567 nm followed by incubation at 25°C for 5 min, and the results were represented as inhibition % at 100 μM (A) and concentration-dependent manner (B). PTIO was used as a positive control. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 versus the vehicle group.

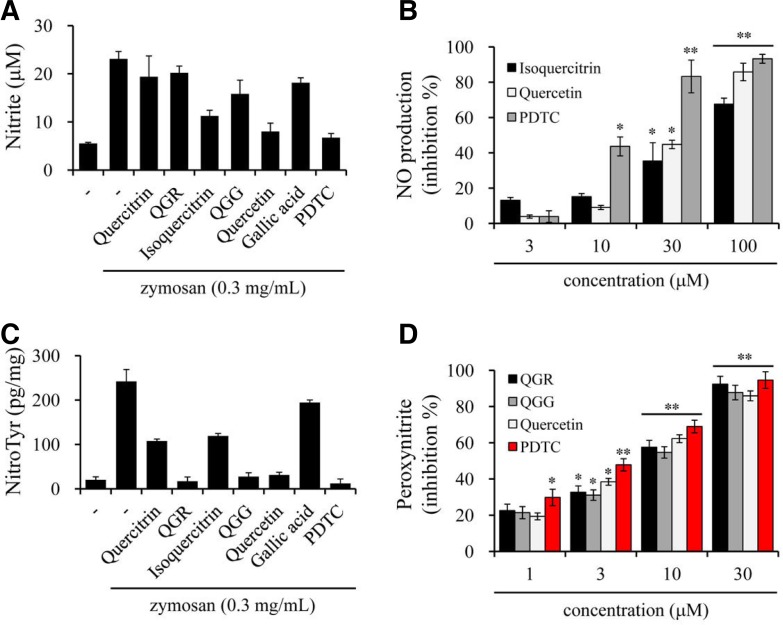

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on NO and ONOO− production

To further investigate whether quercetin and its structurally related compounds affect RNS production, we performed the Griess reaction to assess their effect on NO production in zymosan-induced macrophages. The levels of nitrite, a stable metabolite of NO, were basal (5.2 ± 0.2 μM) in resting cells, whereas it was increased by more than four-fold (23.1 ± 1.6 μM) by stimulation with zymosan for 24 h. Among the examined compounds, quercetin and isoquercitrin exhibited an inhibitory effect against NO production at high concentrations (Figs. 5A and 5B). Conversely, PDTC, the positive control, effectively inhibited zymosan-induced nitrite production in a concentration-dependent manner, and the activity was more potent than those of quercetin and isoquercitrin (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on NO and ONOO− production in macrophages. RAW264.7 cells were incubated with compounds in the presence or absence of zymosan for 24 h. Amounts of NO or peroxynitrite were measured using Griess reaction (A, B) or as relative fluorescence units using 123-DHR oxidation (C, D), respectively. Results were represented as inhibition % at 100 or 30 μM (A, C) and concentration-dependent manner (B, D). PDTC was used as a positive control. **p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 versus either the zymosan-stimulated or vehicle group.

We next investigated whether quercetin and its structurally related compounds affected ONOO− production in zymosan-stimulated macrophages because this metabolite is produced from superoxide and NO. Protein-bound 3-nitrotyrosine, a stable ONOO− metabolite, was produced at basal levels (18.4 ± 5.6 pg/mg protein) in resting macrophages, whereas these amounts were dramatically increased (226.3 ± 24.8 pg/mg protein) by stimulation with zymosan for 24 h. By contrast, QGR, QGG and quercetin exhibited strong inhibitory activity on ONOO− production at 30 μM, which was similar to PDTC, the positive control. Conversely, quercitrin and isoquercitrin exhibited ∼50% inhibition of ONOO− production, but gallic acid did not (Fig. 5C). In the concentration-dependent study, QGR, QGG, quercetin and PDTC exhibited similar inhibitory potentials, with IC50 values of 6.4–8.6 μM (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that the inhibitory activities of QGR, QGG and quercetin against ONOO− production are involved in the inhibition of superoxide production and superoxide scavenging, although the effect on NO production is either weak or absent.

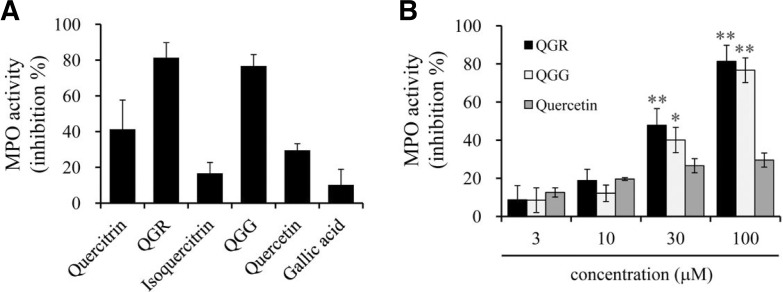

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on myeloperoxidase activity

To further investigate whether quercetin and its structurally related compounds inhibit the production of hypohalides, we isolated neutrophils from the peritoneal lavage of rats and assessed the inhibitory activities against myeloperoxidase (MPO). Hypohalides, such as hypochlorous acid (HOCl), are produced by MPO from H2O2 and either a chloride anion (Cl−) or non-chlorine halide, during the respiratory burst in neutrophils. QGR and QGG effectively inhibited MPO activity at high concentrations (100 μM), whereas quercetin, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid exhibited weak-to-no MPO inhibitory activity (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on MPO activity. Cell lysates of neutrophils were reacted with substrate containing citrate-phosphate buffer for 10 min in the presence or absence of compounds. Myeloperoxidase activity was measured as absorbance at 485 nm, and the results were represented as inhibition % at 100 μM (A) and concentration-dependent manner (B). Results are shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 versus the vehicle group.

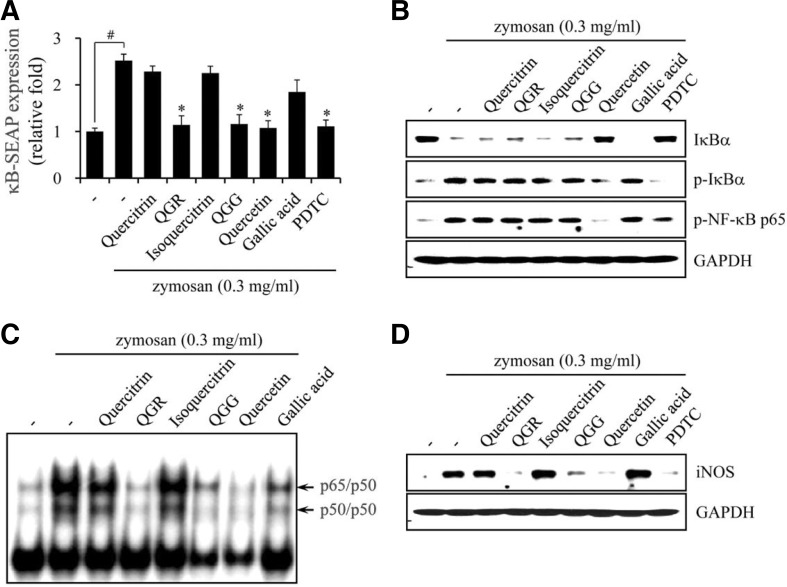

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on NF-κB signaling

NF-κB activation and oxidative stress are associated with various diseases (Bai et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2011; Mariappan et al., 2010). We therefore investigated whether quercetin and its structurally related compounds could affect NF-κB signaling. We assayed SEAP expression as a measurement of NF-κB transcriptional activity in RAW264.7 cells harboring the pNF-κB-SEAP-NPT reporter construct, followed by incubation with various concentrations of each compound for 24 h in the presence or absence of zymosan. SEAP expression was increased by ∼2.5-fold by stimulation with zymosan, indicating that cellular NF-κB is transcriptionally activated and functional. QGR, QGG and quercetin inhibited NF-κB-SEAP expression in a concentration-dependent manner, to as low as basal levels at high concentrations (100 μM). However, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid had no effect on NF-κB-SEAP expression compared with zymosan-stimulated cells (Fig. 7A). The inhibition of zymosan-induced NF-κB-SEAP expression was significantly stronger by PDTC treatment than with QGR, QGG or quercetin.

Fig. 7.

Effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on zymosan-induced NF-κB signaling. (A) RAW264.7 cells harboring pNF-κB-SEAP-NPT reporter construct were pretreated with compounds for 1 h and then incubated for 24 h in the presence or absence of zymosan. SEAP expression as a reporter of NF-κB transcriptional activity was measured with cultured supernatants, and the results are represented as inhibition % at 100 μM and shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. #p < 0.001 versus the vehicle group, and *p < 0.001 versus the zymosan-stimulated group. (B) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with compounds for 1 h and stimulated with zymosan for 10-30 min. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies specific for the molecules indicated. (C) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with compounds for 1 h and stimulated with zymosan for 1 h. Nuclear extracts of the cells were reacted with NF-κB-specific 32P-labeled oligonucleotide and separated on nondenaturing 6% acrylamide gel by electrophoresis. NF-κB complex, p65/p50 and p50/p50, are indicated by an arrow. (D) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with compounds for 1 h and stimulated with zymosan for 24 h. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed with anti-iNOS and GAPDH antibodies. PDTC was used as a positive control.

To activate NF-κB signaling, DNA binding of the NF-κB complex is essential, followed by phosphorylation and proteolytic degradation of the inhibitory protein IκBα. We therefore next assessed the effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on IκBα. Upon exposure to zymosan alone, IκBα was dramatically phosphorylated and degraded within 10 to 30 min, respectively. Quercetin effectively inhibited the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, as well as the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 in zymosan-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, which is consistent with previous reports (Chen et al., 2005; Cho et al., 2003). However, treatment with QGR, QGG, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid at up to 100 μM did not inhibit the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, and phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 (Fig. 7B).

Next, the effect of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on the DNA binding activity of the NF-κB complex was assessed. Upon zymosan-stimulation alone, the DNA binding activities of NF-κB p65/p50 and p50/p50 were markedly increased. QGR, QGG and quercetin inhibited DNA binding of the NF-κB complex, whereas quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid did not (Fig. 7C).

Upon exposure to stimuli, NO is produced primarily by the iNOS enzyme. To determine whether the inhibition of quercetin, QGR and QGG of zymosan-stimulated NO production was due to their effect on the iNOS protein, we examined iNOS protein expression by Western blot analysis. iNOS expression was barely detectable in resting RAW264.7 cells, whereas it was increased markedly by zymosan stimulation. Results showed that QGR, QGG and quercetin inhibited iNOS expression, indicating that the inhibition of NO production was due to a reduction in iNOS expression (Fig. 7D). These results clearly indicate that although quercetin and the quercetin-containing flavonoids QGR and QGG inhibit NF-κB signaling, the molecular target of quercetin and QGR and QGG in NF-κB signaling is differs slightly.

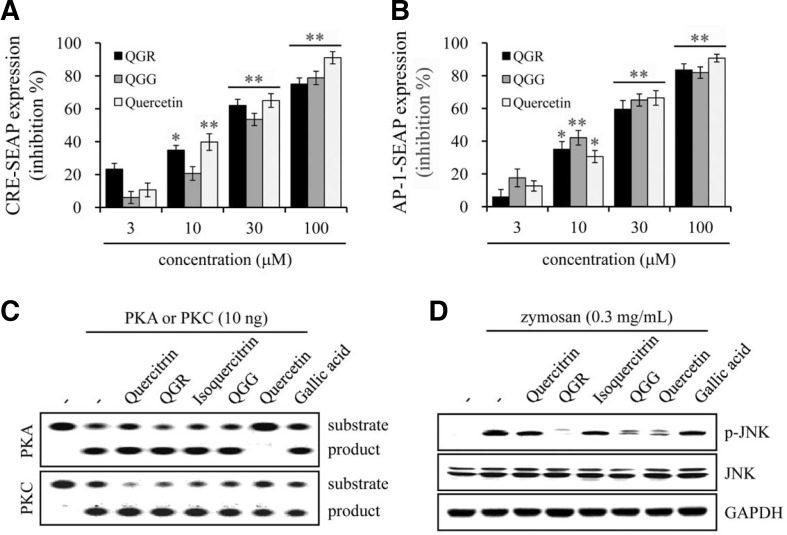

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on CRE and AP-1 signaling

We further examined the transcriptional activities of CRE, activator protein-1 (AP-1), SRE and NFAT by measuring SEAP expression in zymosan-stimulated macrophages followed by transient transfection with a pCRE-SEAP, pAP-1-SEAP, pSRE-SEAP or pNFAT-SEAP plasmid. QGR and QGG inhibited the SEAP expression of CRE and AP-1 in a concentration-dependent manner. The inhibitory activities of QGR and QGG on both CRE and AP-1 transcription were similar but slightly weaker than that of quercetin (Figs. 8A and 8B). However, quercetin, QGR and QGG had no effects on SEAP expression of the SRE and NFAT (Supplementary Fig. S2). The transcriptional activation of CRE and AP-1 is implicated in either the cAMP/PKA or JNK pathway. In addition, PKC activity is important during superoxide generation in the membrane-associated NADPH oxidase complex. Although QGR and QGG inhibited the transcriptional activity of CRE, neither affected PKA or PKC activity. However, quercetin inhibited PKA, but not PKC, activity. Additionally, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid did not affect PKA or PKC activity (Fig. 8C). Regarding JNK signaling, QGR, QGG and quercetin inhibited JNK phosphorylation, but quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid did not (Fig. 8D). Similar to NF-κB signaling, these results also indicate that quercetin and the quercetin-containing flavonoids QGR and QGG inhibited the cAMP/PKA and JNK pathways through different molecular mechanisms.

Fig. 8.

Effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on zymosan-induced CRE and AP-1 signaling. (A, B) RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with pCRE-SEAP or pAP-1-SEAP plasmid for 24 h, and SEAP expression was measured with cultured supernatants. Results are represented as inhibition % and shown as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (C) Purified PKA or PKC was incubated with its specific peptide substrate in the presence or absence of compounds. The reaction mixtures were separated on agarose gel by electrophoresis. One of similar results is represented. (D) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with compounds for 1 h and stimulated with zymosan for 30 min. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed with anti-phospho-JNK, JNK and GAPDH antibodies. **p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05 versus the vehicle group.

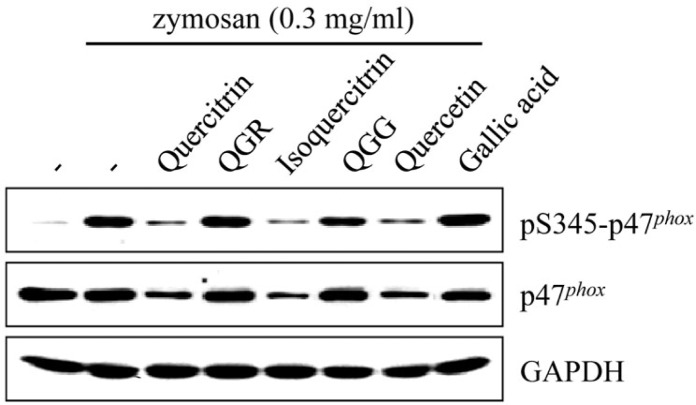

Effect of quercetin and structurally related compounds on NOX complex

To more address the effect of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on the NADPH oxidase complex, we examined the phosphorylation of p47phox, a key component of NOX assembly, due to no affected PKC activity by quercetin and its structurally related compounds. The NADPH oxidase complex is composed of the membrane-associated cytochrome B558 and the cytoplasmic complex p40phox, p47phox and p67phox (Babior, 1999). In fact, quercetin and QGG reported the activities of phosphorylation and protein levels of p47phox in human neutrophils spontaneously hypertensive rats (Liu et al., 2005; Sánchez et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2011b).

Serine residue of the p47phox was phosphorylated by zymosan stimulation in RAW264.7 cells, and this phosphorylation was inhibited by quercetin, QGR and QGG, but not quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid. In addition, quercetin, QGR and QGG suppressed the levels of total p47phox in zymosan-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, whereas these levels were not changed by quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid (Fig. 9). These results suggest that strong anti-oxidant activities of quercetin, QGG and QGG were involved in regulation of the NADPH oxidase complex.

Fig. 9.

Effects of quercetin and its structurally related compounds on zymosan-induced NADPH oxidase complex. RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with zymosan for 30 min, followed by pre-treatment with each compound for 1 h. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed with anti-phospho-p47phox at serine 345, p47phox and GAPDH antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Quercetin is a naturally occurring flavonoid compound that is distributed widely in nature and has a number of biological properties. Recently, quercetin has been used commercially to enhance blood vessel health and as an ingredient in numerous multivitamin preparations and herbal remedies in many countries. Quercitrin and isoquercitrin contain quercetin and either rhamnose or glucose as a glycoside, and QGR and QGG contain quercitrin or isoquercitrin as well as galloyl moieties as their building blocks. Thus QGR, QGG, quercitrin and isoquercitrin contain the quercetin moiety as the core structure. Previous studies have reported antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of quercitrin and isoquercitrin (Babujanarthanam et al., 2011; Camuesco et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2010; Rogerio et al., 2007). QGR and QGG containing quercitrin or isoquercitrin and galloyl moieties have recently been isolated from Polygonum salicifolium and Persicaria lapathifolia (Calis et al., 1999; Park et al., 1999); however their properties have been investigated only minimally. In this study, we evaluated the antioxidant activities of QGR, QGG, quercetin, quercitrin, isoquercitrin, and gallic acid. QGR and QGG exhibited stronger protective effects against oxidative stress than quercetin and a significantly stronger effect than quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid in zymosan-stimulated macrophage RAW264.7 cells.

Antioxidant scavenging of free radicals is one of the defense mechanisms of the body. To prevent ROS- and RNS-mediated damage, the human body has multiple enzymatic antioxidant systems, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase (Irshad and Chaudhuri, 2002). Low levels of ROS and RNS generated by natural by-products are considered beneficial for the cellular immune response against invading microorganisms. However, excessive amounts of these molecules generated during oxidative stress have been implicated in various pathogenic conditions, and activate various signaling pathways through oxidation of reactive cysteine residues on specific target molecules. Therefore, regulation of the ROS- and RNS-generation systems and scavenging of the ROS and RNS generated is important for prevention of oxidative stress-related disorders. We assayed DPPH radical scavenging activity, superoxide production, superoxide scavenging activity, MPO activity, and NO and ONOO− production in zymosan-stimulated macrophages to investigate the antioxidant activity of structurally quercetin-related flavonoids and gallic acid. QGR and QGG exhibited the greatest antioxidant potential as indicated by scavenging activity and inhibition of ROS and RNS production. Although quercetin also showed effective antioxidant activity, no peroxynitrite scavenging and MPO activities were observed. Quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid showed similar antioxidant potentials, which was lower than those of QGR, QGG and quercetin. In flavonoids, the 3′4′-dihydroxy B-ring and hydroxyl group at position 3 of the C-ring are structurally important for antioxidant activity (Cao et al., 1997; Choi et al., 2002; Heijnen et al., 2001). QGR and QGG contain either quercitrin or isoquercitrin and galloyl moieties in their structures, while quercitrin and isoquercitrin contain a quercetin moiety as well as a glycoside (rhamnose or glucose). Despite the importance of the phenolic hydroxyl groups of quercetin for the antioxidant activities of QGR and QGG, the galloyl moiety appears to play a more pivotal role as indicated by the significant increase in activity, even though the activity of gallic acid was either very low or nonexistent.

Numerous studies have reported that quercetin exerts anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. Quercetin targets IKKα phosphorylation, which is an upstream signal of NF-κB, thereby inhibiting phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα and NF-κB activation, resulting in inhibition of the expression and production of pro-inflammatory mediators (Chen et al., 2005; García-Mediavilla et al., 2007; Wadsworth and Koop, 1999). Quercitrin and QGR also inhibit NF-κB activation and iNOS expression, as well as NO production (Camuesco et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005). We found that quercetin inhibited iNOS expression by targeting the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα in zymosan-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, indicating an upstream target of NF-κB; this is consistent with other reports. However, QGR and QGG exhibited different NF-κB-mediated mechanisms of inhibition of NO production and iNOS expression than quercetin. QGR and QGG inhibited DNA binding of the NF-κB complex in the nucleus without affecting phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, whereas quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid did not inhibit NO production and iNOS expression. Therefore, gallic acid is essential for inhibition on the NF-κB signaling by QGR and QGG, even though quercitrin and isoquercitrin do not affect this signaling.

iNOS expression and NO production are regulated by various transcription factors, including NF-κB, AP-1, cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP), interferon-regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1), signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1), STAT3, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), and hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) (Pautz et al., 2010). Of these, QGR, QGG and quercetin inhibited the transcriptional activities of CREB and AP-1. CREB is activated by cAMP/PKA signaling (Delghandi et al., 2005) and JNK activation is related to AP-1 signaling (Papachristou et al., 2003). Quercetin inhibited cell-free PKA enzymatic activity, whereas QGG and QGR did not exhibit significant inhibitory effects on PKA activity. However, JNK phosphorylation was inhibited by quercetin, QGR and QGG. Similar to quercetin in NF-κB signaling, the molecular targets of QGR and QGG in both the cAMP/PKA and JNK/AP-1 signaling pathways differed. Moreover, gallic acid was essential for the QGR and QGG activity because their building blocks quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid did not inhibit these signaling pathways.

NADPH oxidase and iNOS produce superoxide, NO and ONOO− in activated immune cells (Bedard and Krause, 2007; Montezano and Touyz, 2012). The NADPH oxidase complex is composed of the membrane-associated cytochrome B558 and the cytoplasmic complex p40phox, p47phox and p67phox (Babior, 1999). PKC, specifically PKCδ, is important for activation of the NADPH oxidase complex (Brown et al., 2003). In addition, zymosan activates PKC via a receptor-mediated signaling pathway, and PMA is a direct activator of PKC in phagocytes (Klebanoff and Headley, 1999; Liu and Heckman, 1998; Phillips et al., 1992). Although quercetin, QGR and QGG effectively inhibited superoxide production in zymosan-or PMA-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, these compounds showed no significant inhibitory effects on PKC activity, suggesting prevention of the membrane-associated assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex, an event downstream of PKC-mediated phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic p47phox component that is similar to the NADPH oxidase-inhibitory mechanism of apocynin (Stolk et al., 1994). Zymosan and PMA induce NADPH oxidase activation by phosphorylation of the p47phox and activation of the Rac2 through signaling pathways of the protein tyrosine kinases, phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3K), PKC, ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases (Karlsson et al., 2000; Makni-Maalej et al., 2013; Raad et al., 2009). Our results indicated that strong anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of qurecetin, QGR and QGG than quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid resulted in regulation of the NADPH oxidase complex, specifically p47phox.

In the present study, we showed that the quercetin-containing flavonoids, QGR and QGG, exhibited antioxidant activities that were significantly stronger than that of quercetin, a core structure of QGG and QGR. However, their building blocks, quercitrin, isoquercitrin and gallic acid showed weak-to-no antioxidant activities. QGR and QGG exhibited a mechanism of action different from that of quercetin on the NF-κB, cAMP/PKA and JNK/AP-1 signaling pathways, suggesting glycosides with glucose or rhamnose is essential roles to exhibit their anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory potential.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Summary of the antioxidant activities of quercetin, quercetin-containing flavonoids and gallic acid (IC50 value)

| Antioxidant | Quercitrin | QGR | Isoquercitrin | QGG | Quercetin | Gallic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH scavenging | 27.6 μM | 13.6 μM | 24.5 μM | 15.1 μM | 20.7 μM | 19.8 μM |

| Superoxide production | ||||||

| Zymosan-induced | 31.0 μM | 4.9 μM | 30.0 μM | 7.6 μM | 5.5 μM | 25.2 μM |

| PMA-induced | 89.9 μM | 5.6 μM | 92.5 μM | 13.5 μM | 2.5 μM | 81.6 μM |

| Superoxide scavenging | >100 μM | 30.0 μM | >100 μM | 47.6 μM | >100 μM | >100 μM |

| NO production | >100 μM | >100 μM | 61.8 μM | >100 μM | 38.9 μM | >100 μM |

| Peroxynitrite production | 8.6 μM | 7.9 μM | 40.1 μM | 8.6 μM | 6.4 μM | >100 μM |

| Myeloperoxidase | >100 μM | 34.6 μM | >100 μM | 49.0 μM >100 μM | >100 μM |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0014661), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MESF) (Grand No. 2011-0030737; M.-H. Kim and 2010-0027827, 2011-0010571 and 2011-0030739; S.-K. Ye). We thank Dr. Kim YS for kindly providing RAW264.7 cells harboring pNF-κB-SEAP-NPT reporter construct.

Note:

Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

REFERENCES

- Babior BM. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood. 1999;93:1464–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babujanarthanam R, Kavitha P, Mahadeva Rao US, Pandian MR. Quercitrin a bioflavonoid improves the antioxidant status in streptozotocin: induced diabetic rat tissues. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;358:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0927-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai XC, Lu D, Liu AL, Zhang ZM, Li XM, Zou ZP, Zeng WS, Cheng BL, Luo SQ. Reactive oxygen species stimulates receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand expression in osteoblast. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17497–17506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots AW, Haenen GR, Bast A. Health effects of quercetin: from antioxidant to nutraceutical. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008a;585:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots AW, Wilms LC, Swennen EL, Kleinjans JC, Bast A, Haenen GR. In vitro and ex vivo anti-inflammatory activity of quercetin in healthy volunteers. Nutrition. 2008b;24:703–710. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GE, Stewart MQ, Liu H, Ha VL, Yaffe MB. A novel assay system implicates PtdIns(3,4)P(2), PtdIns (3)P, and PKC delta in intracellular production of reactive oxygen species by the NADPH oxidase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:35–47. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calis I, Kuruüzüm A, Demirezer LO, Sticher O, Ganci W, Rüedi P. Phenylvaleric acid and flavonoid glycosides from Polygonum salicifolium. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1101–1105. doi: 10.1021/np9900674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camuesco D, Comalada M, Rodríguez-Cabezas ME, Nieto A, Lorente MD, Concha A, Zarzuelo A, Gálvez J. The intestinal anti-inflammatory effect of quercitrin is associated with an inhibition in iNOS expression. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:908–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Sofic E, Prior RL. Antioxidant and prooxidant behavior of flavonoids: structure-activity relationships. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:749–760. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Ho FM, Chao Pei-Dawn Lee, Chen CP, Jeng KC, Hsu HB, Lee ST, Wu Wen Tung, Lin WW. Inhibition of iNOS gene expression by quercetin is mediated by the inhibition of IkappaB kinase, nuclear factor-kappa B and STAT1, and depends on heme oxygenase-1 induction in mouse BV-2 microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;521:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Li J, Luo C, Liu H, Xu W, Chen G, Liew OW, Zhu W, Puah CM, Shen X, et al. Binding interaction of quercetin-3-beta-galactoside and its synthetic derivatives with SARS-CoV 3CL(pro): structure-activity relationship studies reveal salient pharmacophore features. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:8295–8306. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Arany PR, Huang YY, Tomkinson EM, Sharma SK, Kharkwal GB, Saleem T, Mooney D, Yull FE, Blackwell TS, et al. Low-level laser therapy activates NF-κB via generation of reactive oxygen species in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SY, Park SJ, Kwon MJ, Jeong TS, Bok SH, Choi WY, Jeong WI, Ryu SY, Do SH, Lee CS, et al. Quercetin suppresses proinflammatory cytokines production through MAP kinases and NF-kappaB pathway in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophage. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;243:153–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1021624520740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Chung HY, Kang SS, Jung MJ, Kim JW, No JK, Jung HA. The structure-activity relationship of flavonoids as scavengers of peroxynitrite. Phytother Res. 2002;16:232–235. doi: 10.1002/ptr.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Murphy EA, McClellan JL, Carmichael MD, Gangemi JD. Quercetin reduces susceptibility to influenza infection following stressful exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R505–R509. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90319.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delghandi MP, Johannessen M, Moens U. The cAMP signalling pathway activates CREB through PKA, p38 and MSK1 in NIH 3T3 cells. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo FJ, Fiore JV. On the composition of zymosan. Science. 1958;127:756–757. doi: 10.1126/science.127.3301.756-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mediavilla V, Crespo I, Collado PS, Esteller A, Sánchez-Campos S, Tuñón MJ, González-Gallego J. The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaemp-ferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclo-oxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in chang liver cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen CG, Haenen GR, Vekemans JA, Bast A. Peroxynitrite scavenging of flavonoids: structure activity relationship. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2001;10:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s1382-6689(01)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirpara KV, Aggarwal P, Mukherjee AJ, Joshi N, Burman AC. Quercetin and its derivatives: synthesis, pharmacological uses with special emphasis on anti-tumor properties and prodrug with enhanced bio-availability. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:138–161. doi: 10.2174/187152009787313855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irshad M, Chaudhuri PS. Oxidant-antioxidant system: role and significance in human body. Indian J Exp Biol. 2002;40:1233–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SH, Kim BJ, Lee EH, Osborne NN. Isoquercitrin is the most effective antioxidant in the plant Thuja orientalis and able to counteract oxidative-induced damage to a transformed cell line (RGC-5 cells) Neurochem Int. 2010;57:713–721. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson A, Nixon JB, McPhail LC. Phorbol myristate acetate induces neutrophil NADPH-oxidase activity by two separate signal transduction pathways: dependent or independent of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:396–404. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Jang DS, Park SH, Yun J, Min BK, Min KR, Lee HK. Flavonol glycoside gallate and ferulate esters from Persicaria lapathifolia as inhibitors of superoxide production in human monocytes stimulated by unopsonized zymosan. Planta Med. 2000;66:72–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BH, Cho SM, Reddy AM, Kim YS, Min KR, Kim Y. Down-regulatory effect of quercitrin gallate on nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages RAW 264.7. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1577–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff SJ, Headley CM. Activation of the human immunodeficiency virus-1 long terminal repeat by respiratory burst oxidants of neutrophils. Blood. 1999;93:350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Kang SW. Reactive oxygen species and tumor metastasis. Mol Cells. 2013;35:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0034-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lee BH, Jeong SM, Lee JH, Kim JH, Yoon IS, Lee JH, Choi SH, Lee SM, Chang CG, Kim HC, et al. Quercetin inhibits the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor-mediated ion current by interacting with pre-transmembrane domain I. Mol Cells. 2005;20:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Choi SH, Shin TJ, Pyo MK, Hwang SH, Kim BR, Lee SM, Lee JH, Kim HC, Park HY, et al. Quercetin enhances human α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated ion current through interactions with Ca(2+) binding sites. Mol Cells. 2010;30:245–253. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WS, Heckman CA. The sevenfold way of PKC regulation. Cell Signal. 1998;10:529–542. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Wang W, Masuoka N, Isobe T, Yamashita K, Manabe M, Kodama H. Effect of three flavonoids isolated from Japanese Polygonum species on superoxide generation in human neutrophils. Planta Med. 2005;71:933–937. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makni-Maalej K, Chiandotto M, Hurtado-Nedelec M, Bedouhene S, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Dang PM, El-Benna J. Zymosan induces NADPH oxidase activation in human neutrophils by inducing the phosphorylation of p47phox and the activation of Rac2: involvement of protein tyrosine kinases, PI3Kinase, PKC, ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariappan N, Elks CM, Sriramula S, Guggilam A, Liu Z, Borkhsenious O, Francis J. NF-kappaB-induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction in type II diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:473–483. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montezano AC, Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species and endothelial function--role of nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and Nox family nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;110:87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey KB, Rizvi SI. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;2:270–278. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristou DJ, Batistatou A, Sykiotis GP, Varakis I, Papavassiliou AG. Activation of the JNK-AP-1 signal transduction pathway is associated with pathogenesis and progression of human osteosarcomas. Bone. 2003;32:364–371. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Oh SR, Jung KY, Lee IS, Ahn KS, Kim JH, Kim YS, Lee JJ, Lee HK. Acylated flavonol glycosides with anti-complement activity from Persicaria lapathifolia. Chem Pharm Bull. 1999;47:1484–1486. doi: 10.1248/cpb.47.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Kim YT, Jeon YJ. Antioxidant dieckol downregulates the Rac1/ROS signaling pathway and inhibits Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-family verprolin-homologous protein 2 (WAVE2)-mediated invasive migration of B16 mouse melanoma cells. Mol Cells. 2012;33:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-2285-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pautz A, Art J, Hahn S, Nowag S, Voss C, Kleinert H. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide. 2010;23:75–93. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips WA, Croatto M, Veis N, Hamilton JA. Protein kinase C has both stimulatory and suppressive effects on macrophage superoxide production. J Cell Physiol. 1992;152:64–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041520109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puoci F, Morelli C, Cirillo G, Curcio M, Parisi OI, Maris P, Sisci D, Picci N. Anticancer activity of a quercetin-based polymer towards HeLa cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2843–2847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raad H, Paclet MH, Boussetta T, Kroviarski Y, Morel F, Quinn MT, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Dang PM, El-Benna J. Regulation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase activity: phosphorylation of gp91phox/NOX2 by protein kinase C enhances its diaphorase activity and binding to Rac2, p67phox, and p47phox. FASEB J. 2009;23:1011–1022. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman T, Hosen I, Islam M, Shekhar H. Oxidative stress and human health. Adv Biosci Biotechnol. 2012;3:997–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerio AP, Kanashiro A, Fontanari C, da Silva EV, Lucisano-Valim YM, Soares EG, Faccioli LH. Anti-inflammatory activity of quercetin and isoquercitrin in experimental murine allergic asthma. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:402–408. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-7005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez M, Galisteo M, Vera R, Villar IC, Zarzuelo A, Tamargo J, Pérez-Vizcaíno F, Duarte J. Quercetin down-regulates NADPH oxidase, increases eNOS activity and prevents endothelial dysfunction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2006;24:75–84. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000198029.22472.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Sano H, Iwaki D, Kudo K, Konishi M, Takahashi H, Takahashi T, Imaizumi H, Asai Y, Kuroki Y. Direct binding of Toll-like receptor 2 to zymosan, and zymosan-induced NF-kappa B activation and TNF-alpha secretion are down-regulated by lung collectin surfactant protein A. J Immunol. 2003;171:417–425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk J, Hiltermann TJ, Dijkman JH, Verhoeven AJ. Characteristics of the inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils by apocynin, a methoxy-substituted catechol. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:95–102. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.1.8018341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachootham D, Lu W, Ogasawara MA, Nilsa RD, Huang P. Redox regulation of cell survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1343–1374. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volman TJ, Hendriks T, Goris RJ. Zymosan-induced generalized inflammation: experimental studies into mechanisms leading to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Shock. 2005;23:291–297. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000155350.95435.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth TL, Koop DR. Effects of the wine polyphenolics quercetin and resveratrol on pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:941–949. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Swarts SG, Yin L, Liu C, Tian Y, Cao Y, Swarts M, Yang S, Zhang SB, Zhang K, et al. Antioxidant properties of quercetin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011a;701:283–289. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7756-4_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HB, Wen JK, Zhang J, Miao SB, Ma GY, Wang YY, Zheng B, Han M. Effect of three flavonoids isolated from Japanese Polygonum species on superoxide generation in human neutrophils. Pharm Biol. 2011b;49:815–820. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.