Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) is associated with high morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients. At present, the functional contribution of airway mucins to ALI is unknown. We hypothesized that excessive mucus production could be detrimental during lung injury. Initial transcriptional profiling of airway mucins revealed a selective and robust induction of MUC5AC upon cyclic mechanical stretch exposure of pulmonary epithelia (Calu-3). Additional studies confirmed time- and stretch-dose-dependent induction of MUC5AC transcript or protein during cyclic mechanical stretch exposure in vitro or during ventilator-induced lung injury in vivo. Patients suffering from ALI showed a 58-fold increase in MUC5AC protein in their bronchoalveolar lavage. Studies of the MUC5AC promoter implicated nuclear factor κB in Muc5ac induction during ALI. Moreover, mice with gene-targeted deletion of Muc5ac−/− experience attenuated lung inflammation and pulmonary edema during injurious ventilation. We observed that neutrophil trafficking into the lungs of Muc5ac−/− mice was selectively attenuated. This implicates that endogenous Muc5ac production enhances pulmonary neutrophil trafficking during lung injury. Together, these studies reveal a detrimental role for endogenous Muc5ac production during ALI and suggest pharmacological strategies to dampen mucin production in the treatment of lung injury.

INTRODUCTION

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a life-threatening disorder that can develop in the course of different clinical conditions such as pneumonia, acid aspiration, major trauma, or prolonged mechanical ventilation and contributes significantly to critical illness.1 For example, epidemiological studies show that each year 75,000 patients in the United States alone die from acute respiratory distress syndrome, a severe form of ALI.2 The pathogenesis of ALI is characterized by the influx of a protein-rich edema fluid into the interstitial and intra-alveolar spaces as a consequence of increased permeability of the alveolar–capillary barrier1 in conjunction with excessive invasion of inflammatory cells—particularly polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs).3–6 Indeed, several experimental and clinical studies indicate that pulmonary PMN accumulation represents a key event in the pathophysiology of ALI. For example, depletion of PMNs can curb experimental lung damage,7 while lung function in patients suffering from ALI negatively correlates with neutrophil counts in the blood,8 and persisting pulmonary neutrophilia is correlated with poor outcome.9

Mucosal surfaces—such as the airway epithelia—have a protective mucus barrier. For example, airway mucus traps inhaled toxins and transports them out of the lungs by means of ciliary beating and cough. Airway mucus is a mixture of water, cells, cellular debris, and mucins—heavy glycoproteins—which represent the major protein component of mucus.10 The two predominant mucins of the human airway are MUC5AC and MUC5B.10 In healthy lungs, MUC5AC is produced predominantly in the tracheobronchial secretory cells at the airway surface, whereas MUC5B is produced in surface secretory cells throughout the airways and by submucosal glands.10–14 In the airways of normal mice, almost no Muc5ac is produced,10,15 and mice with Muc5ac deletion appear to be healthy.16 By contrast, Muc5b is produced constitutively in airway surface secretory cells,10,15,17 and it remains abundant in lung inflammation. Although a deficient mucous barrier intuitively leaves the lungs vulnerable to injury, excessive mucus or impaired clearance contributes to the pathogenesis of common airway diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.11,18,19

Despite of the fact that many previous studies have addressed the functional role of mucins in lung disease, essentially nothing is known about the specific functions of airway mucins during ALI. In the context of previous studies showing that ALI provides strong transcriptional stimuli,20–22 and other studies implicating transcriptionally controlled pathways in the regulation of the airway mucin production,14,23,24 we pursued the expression patterns of airway mucins in a microarray study of airway epithelia (Calu-3) exposed to cyclic mechanical stretch. These microarray studies revealed a selective induction of MUC5AC with stretch conditions. Surprisingly, subsequent studies in genetic models indicate that the endogenous production of Muc5ac induced by mechanical ventilation has a detrimental role during ALI. In line with previous studies indicating that PMN contribute to tissue injury during ALI, we observed that genetic deletion of Muc5ac was associated with a selective attenuation of PMNs during experimental lung injury.

RESULTS

Microarray studies of human pulmonary epithelia exposed to cyclic mechanical stretch reveal selective induction of MUC5AC

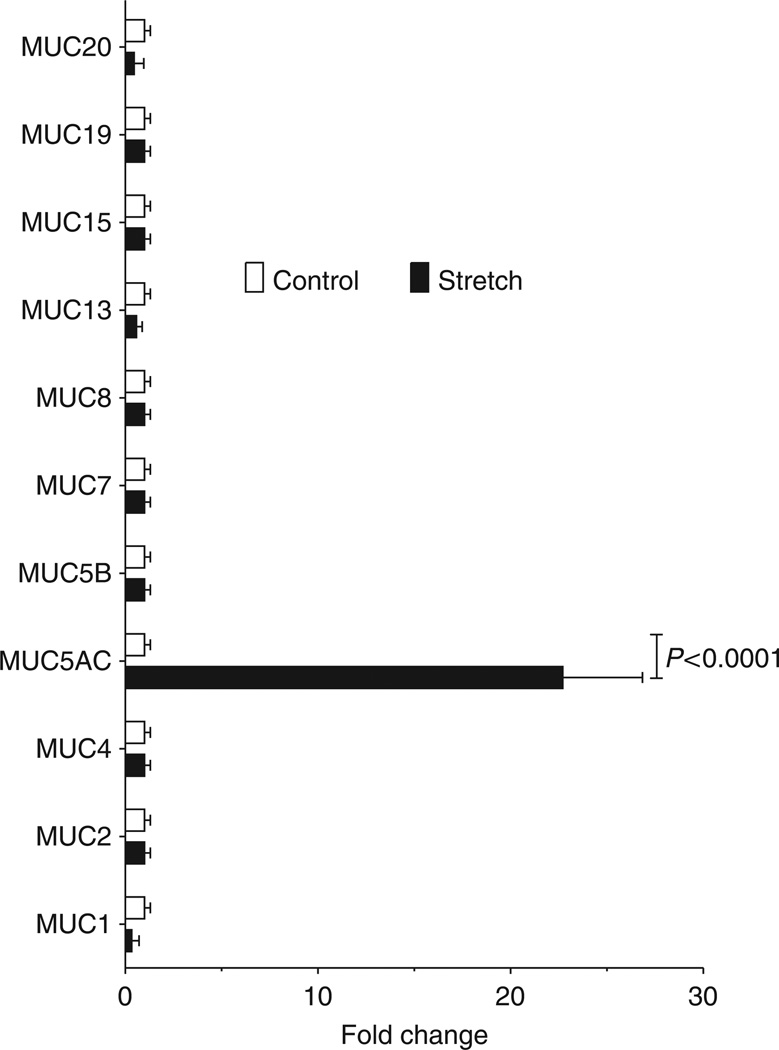

Mucins are an integral part of the innate defense system of the lung, and they have been implicated in various lung diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, and asthma.10,19,25–27 However, their functional role in ALI remains largely unknown. Mucin production is regulated on a transcriptional level.14,23 Therefore, we performed profiling studies of mucin mRNA levels utilizing human pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to cyclic mechanical stretch as an in vitro model of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). The findings from this microarray revealed a robust and selective induction of MUC5AC (22.6±4.1 fold vs. control; n = 2; P<0.05), whereas all other airway mucins were either unchanged or suppressed (Figure 1). Based on these findings, we further pursued a potential functional role of MUC5AC during ALI.

Figure 1.

Transcriptional alteration of human pulmonary epithelial mucins in response to cyclic-mechanical stretch. Calu-3 human pulmonary were plated on collagen-coated plates and underwent cyclic mechanical stretch at 20% stretch maximum, 0.7% stretch minimum, sine wave 2s, on 2 s off for 18h or were maintained at rest. Total RNA was isolated and the transcriptional changes were analyzed using a microarray technique (accession number: GSE34789). Mucins that were previously shown to be expressed in the airway are shown. Results are expressed as fold change in relation to baseline expression. Note: selective induction of Muc5ac in response to cyclic-mechanical stretch (P<0.0001, n =3).

MUC5AC transcript and protein levels are induced with cyclic mechanical stretch in vitro

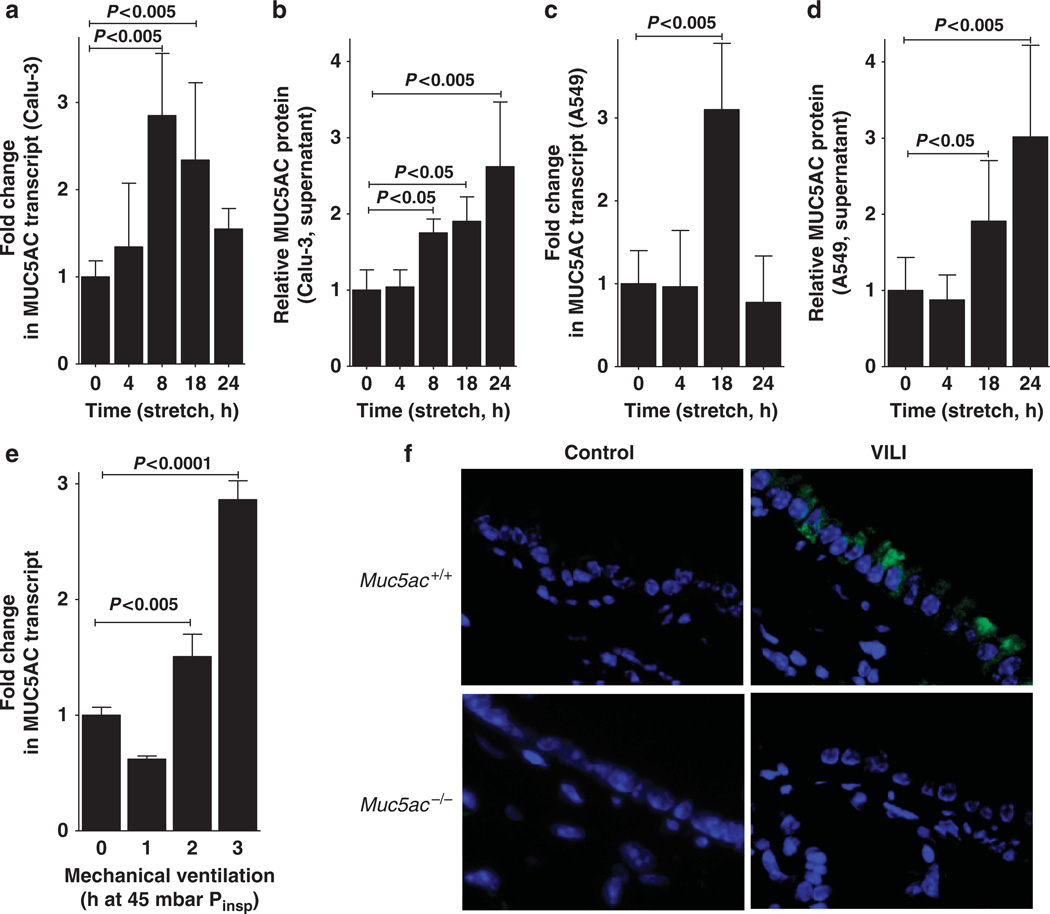

After having shown a selective induction of MUC5AC in microarray studies of pulmonary epithelia exposed to cyclic mechanical stretch, we next investigated the time course of MUC5AC induction in different model cell lines of airway epithelia. We submitted Calu-3 or A549 pulmonary epithelia to various durations of cyclic mechanical stretch and found a time-dependent induction of MUC5AC transcript and protein release into the supernatant (Figure 2a–d). Taken together with our above microarray studies, these findings indicate that MUC5AC transcript and protein levels are increased during conditions of cyclic mechanical stretch as occurs in the setting of mechanical ventilation.

Figure 2.

MUC5AC transcript and protein levels during cyclic mechanical in vitro or during acute lung injury in vivo. (a) Calu-3 human pulmonary epithelial cells were submitted to cyclic mechanical stretch. After the indicated time points total RNA was isolated and samples were probed for MUC5AC mRNA levels by reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR). Transcriptional changes were calculated relative to an internal housekeeping gene (β-actin). Data are expressed as mean fold change ± s.d. compared with 0 h cyclic mechanical stretch (n = 4). (b) Supernatants from stretched Calu-3 human pulmonary epithelia were collected at indicated time points and probed for MUC5AC protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data are expressed as mean fold change ± s.d. compared with 0 h cyclic mechanical stretch (n = 4). (c) A549 human pulmonary epithelial cells were submitted to cyclic mechanical stretch. After the indicated time points, total RNA was isolated, and samples were probed for MUC5AC mRNA levels by RT-PCR. Transcriptional changes were calculated relative to the internal housekeeping gene (β-actin). Data are expressed as mean fold change ± s.d. compared with 0 h cyclic mechanical stretch (n = 4). (d) Supernatants from stretched A549 human pulmonary epithelia were collected at indicated time points and probed for MUC5AC protein by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean fold change ± s.d. compared with 0 h cyclic mechanical stretch (n = 4). (e) C57BL/6 mice were mechanically ventilated (inspiratory pressure (Pinsp) 45 mbar, 100% oxygen). After indicated time periods, lungs were harvested; total RNA isolated, and Muc5ac mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data are calculated relative to the internal housekeeping gene (β-actin) and are expressed as mean fold change compared with control (0 h ventilation) ± s.d. (n = 4). (f) Muc5ac−/− or corresponding littermate controls matched in age, sex, and weight (Muc5a+/+ mice) were mechanically ventilated (inspiratory pressure 45 mbar, inspired oxygen fraction 1.0, positive-end expiratory pressure 3 mbar). After 3 h of mechanical ventilation, the lungs were fixated in situ and stained with antibodies for Muc5ac. Immunoglobulin G controls were used at identical concentrations and staining conditions as the target primary antibodies. One representative experiment out of four is shown (original magnification ×400). VILI, ventilator-induced lung injury.

MUC5AC expression is increased in mice exposed to VILI

Based on our in vitro findings showing MUC5AC induction during cyclic mechanical stretch of pulmonary epithelia, we next pursued studies of Muc5ac expression during murine VILI. We anesthetized mice and performed a tracheostomy, followed by pressure-controlled ventilation with an inspiratory pressure level of 45 mbar over indicated time periods (0–3 h).20,28–30 Consistent with the in vitro findings, we observed a robust induction of the Muc5ac transcript in response to high-pressure ventilation (Figure 2e; P<0.005). By contrast, transcript levels for Muc2 were unaltered, whereas Muc5b transcript was significantly repressed during VILI (see Supplementary Figure S1 online). Utilizing immunofluorescence microscopy, we also observed induction of Muc5ac protein in mice exposed to VILI over 3 h (Figure 2f). Control studies in previously described mice gene-targeted for Muc5ac16 provide specificity for these staining studies (Figure 2f). Taken together, these studies indicate induction of MUC5AC transcript and protein levels during cyclic mechanical stretch exposure of human airway epithelia in vitro or during murine VILI in vivo.

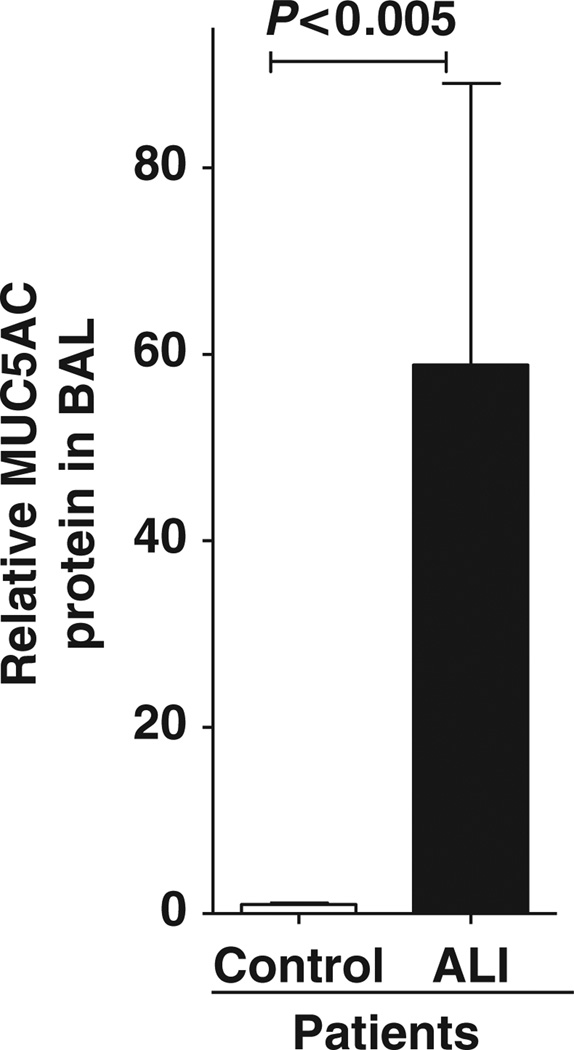

MUC5AC protein is increased in patients with ALI

Having demonstrated that MUC5AC is induced in models of ALI, we examined MUC5AC protein levels in patients with ALI. After approval by the Internal Review Board, lavage samples were collected in patients experiencing ALI or corresponding healthy controls (see Supplementary Table S1 online). We retrospectively measured MUC5AC protein levels in the lavage fluid collected from unventilated control subjects or patients diagnosed with ALI utilizing enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Interestingly, these studies revealed a 58.8-fold increase of MUC5AC protein in the BAL fluid of patients with ALI. These novel findings indicate that MUC5AC is increased in the BAL fluid of humans experiencing ALI.

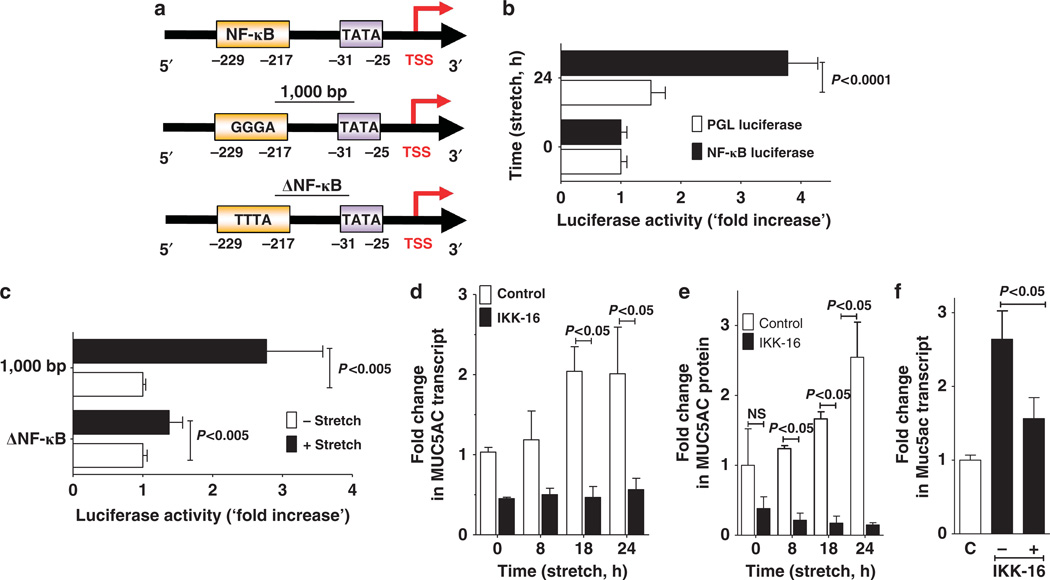

Nuclear factor (NF-κB) is critical for MUC5AC induction during cyclic mechanical stretch in vitro or during ALI in vivo

After having shown that MUC5AC is induced in model systems of lung injury or in patients suffering from ALI, we next analyzed the transcriptional mechanism governing MUC5AC expression under these conditions. Previous studies had implicated NF-κB in the transcriptional regulation of MUC5AC23 and that this is mediated via binding of NF-κB to a specific area within the MUC5AC promoter (Figure 4a).31 Indeed, during similar conditions of cyclic mechanical stretch associated with the transcriptional induction of MUC5AC, we observed robust increases of NF-κB reporter activity (3.8-fold increase; Figure 4b; P<0.0001). To examine the influence of cyclic mechanical stretch conditions on the MUC5AC promoter, we cloned the previously described human MUC5AC promoter31 into a PGL4-vector and examined alterations in promoter activity with stretch conditions. Cells transiently transfected with the wild-type promoter showed a 2.4±0.1-fold increase in promoter activity when exposed to cyclic mechanical stretch as compared with unstretched controls. By contrast, stretch-responsiveness of a promoter construct with a mutated, putative NF-κB binding site was completely lost, implicating a functional role of NF-κB binding to the MUC5AC promoter during cyclic mechanical stretch (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Transcriptional regulation of Muc5ac during cyclic mechanical stretch in vitro or during acute lung injury in vivo. (a) Upper panel: Schematic of human MUC5AC promoter. Middle panel: Core sequence of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB binding site of the human MUC5AC promoter located −217 to −229 bp upstream from the transcription start site (TSS). Lower panel: Loss of function mutation of NF-κB binding site in MUC5AC promoter construct studies. (b) Luciferase activity in A549 pulmonary epithelial cells transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter plasmid for NF-κB and renilla luciferase reporter plasmids. Cells were exposed to 24 h of cylic mechanical stretch and all activity was normalized with respect to renilla reporter. Results are presented as “fold change” in luminescence relative to that of an empty PGL-luciferase. Data were calculated as fold change compared with 0 h cyclic mechanical stretch and are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 4). (c) Luciferase activity in A549 pulmonary epithelial cells transfected with human MUC5AC promoter firefly luciferase reporter construct or renilla luciferase reporter plasmid, then exposed to 24 h of cyclic mechanical stretch. Full-length MUC5AC promoter (1,000 bp upstream of TSS); ΔNF-κB loss-of-function mutation of NF-κB binding site (position −229 to −217 relative to TSS). Data were calculated as fold change compared with 0 h cyclic mechanical stretch and are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 4). (d) Calu-3 human pulmonary epithelial cells were incubated with the NF-κB-inhibitor IKK-16 followed by cylic mechanical stretch and harvested at the indicated time points. Total RNA was isolated, and samples were probed. MUC5AC mRNA by reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) and transcriptional changes were calculated relative to the internal housekeeping gene (β-actin). Data are expressed as mean fold change compared with 0 h of cyclic mechanical stretch ± s.d. (n = 6). (e) Calu-3 human pulmonary epithelial cells were incubated with the NF-κB-inhibitor IKK-16 followed by cyclic mechanical stretch and harvested at the indicated time points. Cell lysates were probed for MUC5AC protein levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are expressed as mean fold change compared with 0 h of cyclic mechanical stretch ± s.d. (n = 6). (f) C57BL/6 mice were treated with 30 mg kg−1 IKK-16 (NF-κB-inhibitor) followed by mechanical ventilation (inspiratory pressure 45 mbar, inspired oxygen fraction 1.0, positive-end expiratory pressure 3 mbar). After 3 h, lungs were harvested; total RNA isolated, and Muc5ac mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data were calculated relative to the internal housekeeping gene (β-actin) and are expressed as mean fold change compared with control (0 h ventilation) ± s.d. (n = 4).

As second line of evidence, we inhibited NF-κB pharmacologically with a highly selective inhibitor, IKK-16.32 For this purpose, IKK-16 (3 µM) was added to the supernatants of Calu-3 cells 2 h before stretch exposure.32 Subsequently, we examined MUC5AC transcript levels at indicated time points in the IKK-16-treated cells or controls treated with vehicle. Indeed, pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB activation with IKK-16 completely abolished the induction of MUC5AC transcript levels during cyclic mechanical stretch exposure (Figure 4d). Similarly, IKK-16 treatment abolished the induction of MUC5AC protein levels in stretch-exposed Calu-3 cells (Figure 4e).

We next extended these findings into in vivo studies of ALI induced by mechanical ventilation. Based on previous studies, we pretreated BL6 mice 30 min before the induction of VILI with IKK-16 (30 mg kg−1) or vehicle control. Following 3 h of exposure to VILI (pressure-controlled ventilation at 45 mbar), we examined Muc5ac transcript levels by real-time reverse transcriptase–PCR. Consistent with the inhibition of MUC5AC induction during cyclic mechanical stretch in vitro, in vivo treatment with IKK-16 abrogated Muc5ac induction (Figure 4f). Taken together these studies collectively suggest that NF-κB directly regulates MUC5AC induction during cyclic mechanical stretch in vitro or during murine lung injury induced by mechanical ventilation in vivo.

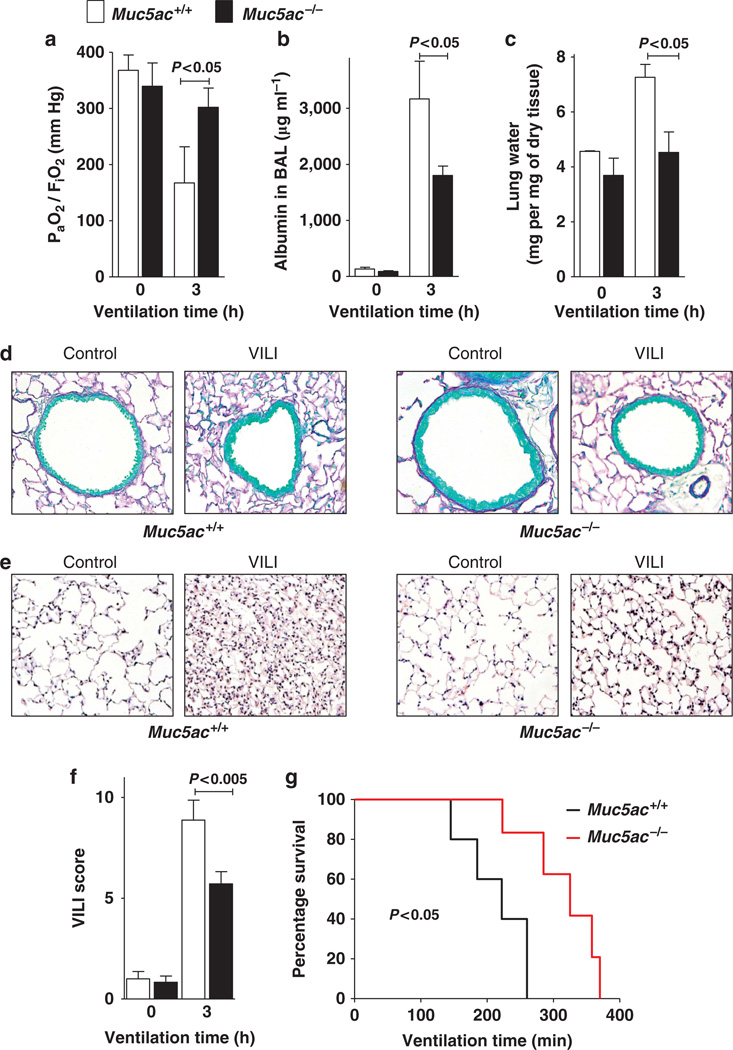

Muc5ac−/− mice are protected during VILI

Having shown that the transcriptional control of MUC5AC during ALI involves NF-κB, we next examined the functional role of Muc5ac during VILI. For this purpose, we subjected recently described Muc5ac gene-targeted mice to VILI (pressure-controlled ventilation at 45 mbar for 3 h) and measured the extent of ALI. Surprisingly, the profound reduction of pulmonary gas exchange (ratio of the arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)) observed in wild-type mice was almost completely abolished in Muc5ac−/− mice. This provides the first evidence for a detrimental role of Muc5ac in ALI (Figure 5a). Furthermore, we found that ALI-induced increases in pulmonary edema assessed by albumin leakage into the BAL or measurements of lung water content were significantly lower in Muc5ac-deficient mice (Figure 5b,c). As next step, we performed histological studies to examine whether VILI was associated with a more pronounced obstruction of small airways. However, no mucous plugs or difference in the number of mucous-producing cells were observed in Muc5ac+/+ or Muc5ac−/− (Figure 5d). Assessment of pulmonary histology following VILI revealed a significantly lower degree of histological tissue injury in Muc5ac−/− mice compared with littermate controls (Figure 5d,e). Moreover, Muc5ac−/− mice survived significantly longer when submitted to VILI than wild-type littermate controls (Figure 5f). Together these studies provide the first genetic evidence for improved pulmonary function and decreased severity of VILI associated with genetic deletion of Muc5ac.

Figure 5.

Phenotypic characterization of Muc5ac−/− mice during ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). (a–f) Muc5ac−/− mice or corresponding littermate controls matched in age, sex, and weight (Muc5a+/+) were mechanically ventilated (inspiratory pressure (Pinsp) 45 mbar, inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) 1.0, positive-end expiratory pressure 3 mbar). (a) Arterial blood samples were collected at indicated time points and analyzed for oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) by a bedside blood gas analyzer. Ratio of PaO2 and FiO2 was calculated. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. (n = 6 per group). (b) Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected at the indicated time points and was analyzed for albumin content. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. (n = 6 per group). (c) At indicated time points, lungs were excised, patted dry, and weighed. Then lungs were dried for 48 h, and lung water content (mg lung water per mg dry tissue) was determined. Data are shown as mean ± s.d. (d) Muc5ac−/− or corresponding littermate controls were mechanically ventilated as described above. Lungs were fixed in situ and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). (original magnification x 40; n = 4). (e) For quantification of tissue damage due to mechanical ventilation, a histological score for VILI was assessed in Muc5ac+/+ and Muc5ac−/− mice based on H&E stainings. Results are displayed as median ± s.d. (n = 5). (f) Muc5ac−/− or corresponding littermate controls were mechanically ventilated as described above until a cardiac standstill was observed in the surface electrocardiogram. (n = 5).

Muc5ac enhances pulmonary inflammation in ALI

Previous studies strongly implicated an excessive invasion of inflammatory cells (particularly PMNs) in the pathogenesis of ALI.3–6. Therefore, we examined inflammatory end points in Muc5ac−/− mice or littermate controls exposed to VILI. First, we quantified the myeloperoxidase (MPO) as a readout for PMN tissue accumulation33 in lung homogenates following 3 h of mechanical ventilation at 45 mbar. Consistent with previous studies, we found profound increase in pulmonary MPO following the induction of ALI in wild-type animals.20–22 By remarkable contrast, however, this increase in pulmonary MPO levels was almost completely abolished in Muc5ac−/− mice (Figure 6a). We found similar alterations of inflammatory end points for Cxcl1 transcript (Figure 6b) and protein (Figure 6c), Cxcl2 transcript (Figure 6d) and interleukin (IL)-6 protein (Figure 6e), indicating that genetic deletion of Muc5ac is associated with an attenuated acute inflammatory response during VILI.

Figure 6.

Inflammatory parameters in Muc5ac+/+ and Muc5ac−/− acute lung injury. Muc5ac−/− mice or their corresponding littermate controls matched in age, sex, and weight were mechanically ventilated (inspiratory pressure (Pinsp) 45 mbar, inspired oxygen fraction 1.0, positive-end expiratory pressure 3 mbar). After the indicated time points, the lungs were harvested and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. (a) Frozen tissue was homogenized and probed for myeloperoxidase (MPO) protein levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). MPO content was normalized to total protein content of homogenate determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA). Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 5). (b) Total RNA was isolated and Cxcl1 mRNA levels were determined by real-time reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR). Data were calculated relative to the internal housekeeping gene (β-actin) and are expressed as mean fold change compared with control (0 h ventilation) ± s.d. (n = 4). (c) Frozen tissue was homogenized and probed for Cxcl1 protein levels by ELISA. Cxcl1 content was normalized to total protein content of homogenate determined by BCA. Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n= 5). (d) Total RNA was isolated and Cxcl2 mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data were calculated relative to the internal housekeeping gene (β-actin) and are expressed as mean fold change compared with control (0 h ventilation) ± s.d. (e) Frozen tissue was homogenized and probed for interleukin (IL)-6 protein levels by ELISA. IL-6 content was normalized to total protein content of homogenate determined by BCA. Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 5).

To further define the role of Muc5ac in the inflammatory response during VILI, we performed a PCR array to examine the expression levels of various cytokines and their receptors in Muc5ac−/− mice or corresponding littermate controls. Following VILI (45 mbar over 3 h), many proinflammatory cytokines were induced in wild-type or Muc5ac−/− mice (see Supplementary Table S3 online). However, several chemokines and chemokine receptors implicated in PMN trafficking were differentially regulated. Their transcriptional induction was significantly less pronounced in Muc5ac−/− mice when compared with wild-type animals (e.g., Ccl20, Ccl7, Cxcl1 and Cxcl10 and Il-11; see Supplementary Table S4 online). Taken together, these studies suggest that Muc5ac−/− mice experience attenuated lung inflammation and neutrophil trafficking during VILI.

Muc5ac deletion selectively dampens pulmonary neutrophil accumulation during VILI

Muc5ac−/− mice experienced attenuated lung inflammation during VILI. This was in conjunction with attenuated expression of pulmonary chemokines and chemokine receptors implicated in PMN trafficking. Subsequently, we analyzed influence of Muc5ac gene-deletion on myeloid cell trafficking during VILI. We submitted Muc5ac−/− mice or corresponding littermate controls to VILI (45 mbar inspiratory pressure, 3 h), harvested lung tissue and BAL fluid and performed flow cytometry on live leukocytes (CD45 + cells). Consistent with the PCR array showing a selective increase of trafficking markers for PMN, Ly6Ghigh/CD11bhigh cells (PMN) were selectively increased in the pulmonary tissue of wild-type mice exposed to VILI (Figure 7a–d). By contrast, this increase in pulmonary PMN accumulation was completely abolished in lungs from Muc5ac−/− mice. Granulocyte trafficking into the BAL (Figure 7e–h) mirrored the studies of lung tissue, confirming that Muc5ac−/− mice experience a selective attenuation of PMN trafficking into the alveolar airspace during ALI induced by mechanical ventilation.

Figure 7.

Granulocyte accumulation in Muc5ac+/+ or Muc5ac−/− during ventilator-induced lung inury (VILI). (a–h) Muc5ac−/− mice or littermate controls matched in age, gender, and weight were mechanically ventilated (inspiratory pressure 45 mbar, inspired oxygen fraction 1.0, positive-end expiratory pressure 3 mbar), followed by collection of bronchoalveolar fluid (BAL) and harvest of the lungs. Flow cytometry was performed on tissue homogenates (a–d) and corresponding BAL (e–h) for eosinophils (EOS; SiglecF+/Ly6G−/CD11b+), polymorphnuclear neutrophils (PMN; Ly6Ghigh/CD11 bhigh/SiglecF), dendritic cells (DC; MHCII+ CD11chigh), and macrophages (Mφ); F4/80+/MHCII+/CD11b+/Ly6G-) following gating of Live CD45+ leukocytes. (a) Absolute cell numbers from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ lung homogenate at baseline. (b) Representative flow cytometry for PMNs from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ lung homogenates at baseline. (c) Absolute cell numbers from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ lung homogenates after 3 h of mechanical ventilation (as described above). (d) Representative flow cytometry for PMNs from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ lung homogenates after mechanical ventilation (as described above). (e) Absolute cell numbers from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ BAL at baseline. (f) Representative flow cytometry for PMNs from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ BAL at baselines. (g) Absolute cell numbers from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ lung homogenates after 3 h of mechanical ventilation (as described above). (h) Representative flow cytometry for PMNs from Muc5ac−/− or Muc5ac+/+ BAL after mechanical ventilation (as described above). All data are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 5 per strain).

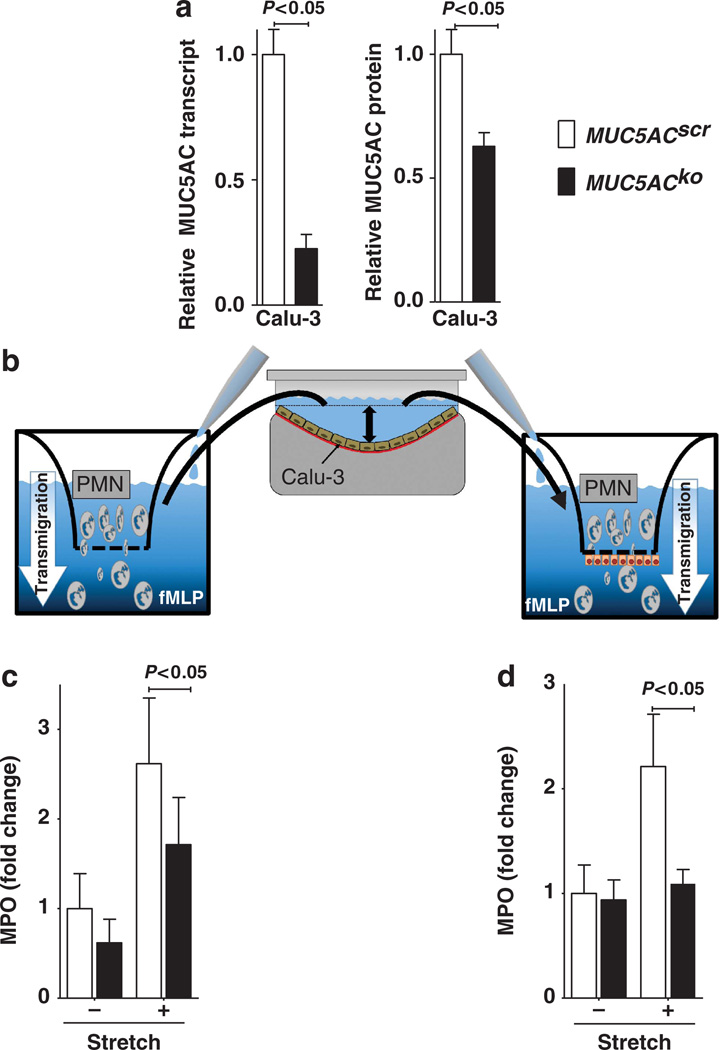

Muc5ac enhances neutrophil transmigration in vitro

Studies of granulocyte trafficking into the lungs during VILI indicated a selective attenuation of PMN transmigration into lung tissue and BAL of Muc5ac−/− mice. We next pursued in vitro studies of PMN transmigration. For this purpose, we examined the effect of supernatants from stretch-exposed control cells or small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated MUC5AC-deficient cells on PMN transmigration. Human pulmonary epithelia (Calu-3) were transfected with stable siRNA to repress MUC5AC. As shown in Figure 8a, hairpin siRNA-mediated MUC5AC repression significantly attenuated MUC5AC transcript and protein levels in Calu-3 cells in comparison to control-siRNA-transfected Calu3 cells (Figure 8a). To examine the functional role of MUC5AC release into the supernatant, we submitted these model cell lines to 24 h cyclic mechanical stretch. Subsequently, we harvested the supernatant of stretched cells or unstretched controls and transferred the supernatant to the basal compartment of aPMN transmigration chamber. We then added freshly isolated human PMN to the apical compartment of the chamber (Figure 8b). PMN transmigration towards a chemotactic agent (formyl-methinyl-leucyl-phenylalanine) was carried out across a mechanical barrier (inserts with a pore size of 3 µm2; Figure 8c) or a biological barrier (Calu-3 pulmonary epithelia grown to confluence, Figure 8d). Indeed, assessment of PMN transmigration by measuring MPO from the basal compartment revealed that stretch-exposed supernatants from control-transfected cells significantly increased PMN transmigration in both the models. By contrast, supernatants from MUC5AC-deficient cell lines had no significant effect on PMN transmigration. Taken together, these studies suggest that endogenous induction of MUC5AC enhances in vitro transmigration of PMN.

Figure 8.

Role of Muc5ac in neutrophil transmigration in vitro. (a) Calu-3 pulmonary epithelial cells were stably transfected with hairpin siRNA targeting MUC5AC (MUC5ACko) or non-specific control siRNA (MUC5ACscr). Total RNA isolated and protein from cell lysates was harvested. Left panel: MUC5AC mRNA levels were determined by real-time reverse transcriptase–PCR. Data were calculated relative to the internal housekeeping gene (β-actin) and are expressed as mean fold change ± s.d. compared with scramble siRNA transfection (n=4). Right panel: Cell lysates were probed for MUC5AC protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data were normalized to protein content isolated from MUC5ACscr cells and are expressed as mean±s.d. (n=4). (b) MUC5ACscr or MUC5ACko cells were seeded on an elastic membrane and submitted to 24 h cyclic mechanical stretch. The supernatant was harvested and transferred into the lower chamber of a transmigration transwell system with or without a confluent Calu-3 human pulmonary epithelial monolayer. In all, 106 freshly isolated human neutrophils (PMN) were added to the apical chamber of the transwell. N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) was added to the lower chamber as PMN-chemoattractant. (c) Transmigration over a mechanical barrier (3 mm2 pore size). After 45 minutes, lower chamber was assayed for MPO activity as readout for PMN transmigration Data are expressed as relative changes of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity measured by absorbance at 405 nm (n = 4 per experimental condition). (d) Transmigration over a biological barrier (confluent Calu-3 human pulmonary epithelial cell monolayer grown on a 3 µm2 pore size insert). After 90 min, basolateral chamber was assayed for MPO activity as readout for PMN transmigration. Data are expressed as relative changes of MPO activity measured by absorbance at 405 nm (n = 4 per experimental condition).

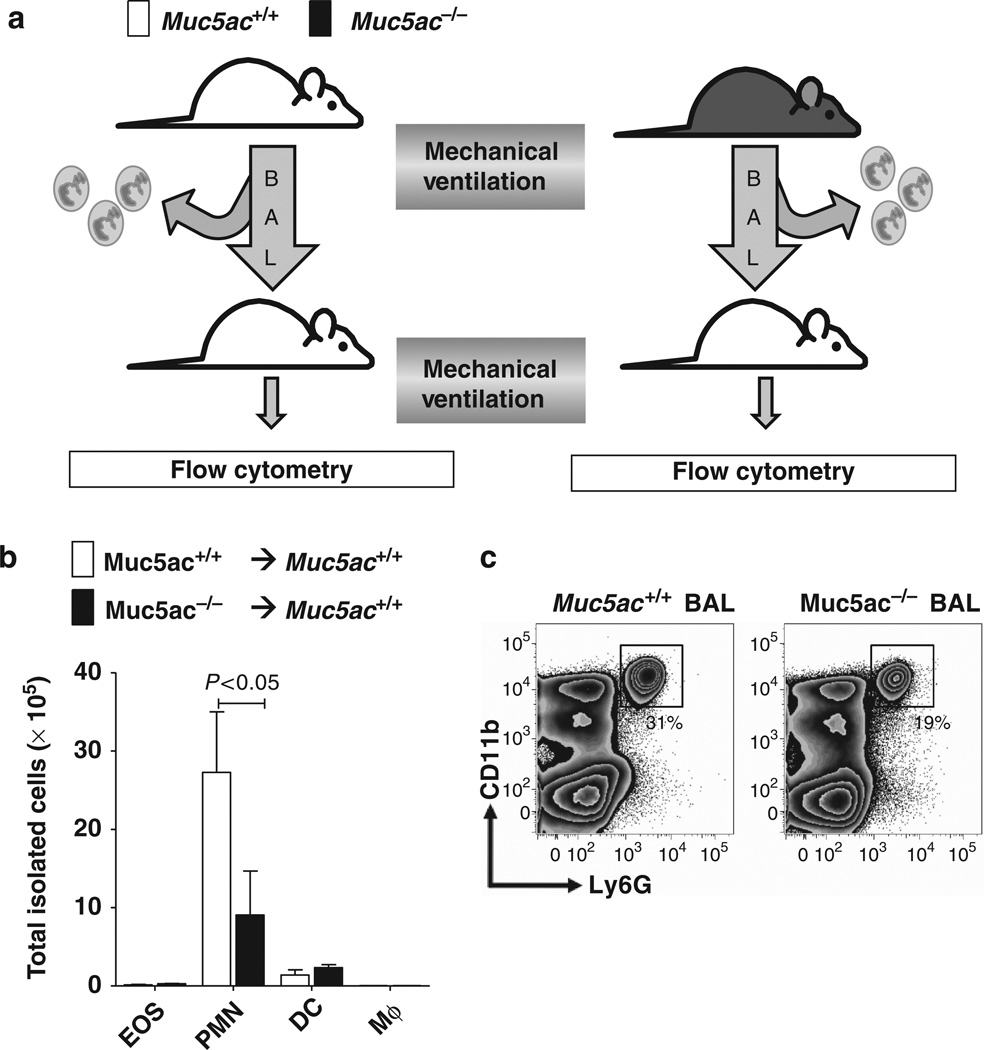

Muc5ac contributes to chemotactic trafficking of PMNs into the lungs in vivo

The above studies implicated that MUC5AC secretion interacts with PMN transmigration in vitro. We extended these findings into an in vivo model of pulmonary PMN trafficking. Muc5ac−/− mice or littermate controls underwent 3 h of mechanical ventilation. We assumed that this treatment is associated with the production and release of Muc5ac in wild-type but not in Muc5ac−/− mice. Subsequently, we harvested 500 µl of BAL and eliminated any cellular content by centrifugation. Next, wild-type mice were anesthetized, intubated, and 100 µl of freshly harvested BAL fluid was instilled into their lungs via the endotracheal tube (Figure 9a). After an additional 3 h of gentle mechanical ventilation at 15 mbar, animals were killed and pulmonary granulocyte trafficking was assessed by flow cytometry. Surprisingly, these studies revealed that transfer of BAL from mechanically ventilated Muc5ac+/+ mice into Muc5ac+/+ was associated with a substantial and selective increase in neutrophil numbers into the BAL (Figure 9b) and lung tissue (Figure 9c). Where we transferred BAL from ventilated Muc5ac−/− mice into wild-type mice, this increase in PMN numbers was almost completely abolished. Taken together these data suggest that Muc5ac increase PMN trafficking into the lungs during ALI.

Figure 9.

Effect of BAL fluid transfer on pulmonary granulocyte trafficking. (a) Muc5ac−/− mice or their corresponding littermate controls matched in age, sex, and weight (Muc5ac+/+) were exposed to gentle mechanical ventilation over 3 h and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was collected and centrifuged to eliminate cellular content. Subsequently, 100µl of this BAL was transferred into anesthetized Muc5ac+/+ mice, and gentle mechanical ventilation (inspiratory pressure 15 mbar) was continued. After 3 h, lungs were harvested and examined by flow cytometry. (b) Cell numbers of eosinophils (EOS), polymorphnuclear neutrophils (PMN), dendritic cells (DC), and macrophages (Mφ) in lung homogenate. Mice received a BAL transfer from either Muc5ac+/+ or Muc5ac−/− mice as described above. Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. (n = 4 per group) (c) Representative flow cytometry blot for PMNs from lung homogenates from mice that received BAL fluid from either Muc5ac+/+ or Muc5ac−/−.

DISCUSSION

ALI significantly contributes to critical illness, as it occurs frequently2 and carries a high mortality rate.1 Moreover, the only therapeutic interventions currently available are elimination of the causative agents and supportive therapy.1 Although airway mucins have previously been implicated in many airway diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary fibrosis,10,19,25,26,34 their functional roles during ALI are essentially unknown. Our studies revealed a selective and robust induction of the human airway mucin MUC5AC. Similarly, patients experiencing ALI showed elevated MUC5AC levels in their BAL fluid (58-fold increase). Moreover, Muc5ac protein and transcript levels were increased in mice exposed to VILI. To provide evidence for a functional role of MUC5AC in ALI, we subsequently exposed gene-targeted mice for Muc5ac to ALI induced by mechanical ventilation. Surprisingly, these mice were profoundly protected from lung inflammation. Additional studies pointed out that neutrophil accumulation within the lungs of Muc5ac−/− mice were selectively attenuated, thereby implicating endogenous production of MUC5AC in regulation of inflammatory cell trafficking during ALI.

Similar to the present studies showing a detrimental role of MUC5AC in ALI, previous studies show a deleterious role of mucins in other forms of peripheral lung diseases. For example, a recent study implicates the endogenous production of MUC5B in the development of pulmonary fibrosis.19 Indeed, this study identified a common variant in the MUC5B promoter that is associated with the development of familial interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Linkage, fine mapping, selective re-sequencing of MUC2 and MUC5AC, and a genetic analysis of the gel-forming mucin region at the p-terminus of chromosome 11 resulted in the identification of a single nucleotide polymorphism (rs35705950) in the putative MUC5B promoter that is strongly associated with both MUC5B expression in the lung among unaffected subjects and the development of familial interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Moreover, subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis had significantly higher levels of expression of MUC5B in the lungs than did controls, and the MUC5B protein was expressed in lesions of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. As such, these studies suggest that overproduction MUC5B is associated with a substantially increased risk for familial interstitial pneumonia or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A possible explanation for the relationship between the single nucleotide polymorphism and excess production of MUC5B could be that too much MUC5B impairs the mucosal host defense, results in excessive lung injury from inhaled substances, and over time leads to the development of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

The present studies indicate that MUC5AC levels are transcriptionally induced during experimental lung injury. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing very robust increases of MUC5AC during allergic mucous metaplasia of the surface epithelium in humans.27 By contrast, studies of MUC5B induction during asthma demonstrate only moderate increases.10,15,35 Indeed, several transcriptionally controlled pathways for the regulation of MUC5AC expression have been previously described.10 For example, recent studies assessed the expression of the entire gel-forming mucin gene family in allergic mouse airways and found a selective induction of Muc5ac. To better understand the tight regulation of Muc5ac expression, the authors analyzed all available 5′-flanking sequences of mammalian MUC5AC orthologs and identified evolutionarily conserved regions within domains proximal to the mRNA coding region. Analysis of luciferase reporter gene activity in a mouse-transformed Clara cell line demonstrated that this region possesses strong promoter activity and harbors multiple conserved transcription factor-binding motifs. In particular, SMAD4 and HIF-1α (hypoxia-inducible factor-1α) bind to the promoter, and mutation of their recognition motifs abolishes promoter function.14 Other studies provide evidence that pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-17A are potent inducers of MUC5AC mRNA and protein. MUC5AC induction by these cytokines was both time- and dose-dependent and occurred at the level of promoter activation, as measured by a reporter gene assay. These effects were attenuated by the small molecule inhibitor NF-κB inhibitor III, as well as p65 siRNA, suggesting that the regulation of MUC5AC expression by these cytokines is intimately linked to NF-κB-based transcriptional mechanisms.23 These findings are very consistent with this study of MUC5AC expression during cyclic mechanical stretch in vitro or during lung injury induced by mechanical ventilation in vivo. Indeed, the present studies implicate NF-κB-based transcriptional mechanisms in the transcriptional regulation of MUC5AC during ALI.

Pharmacological approaches to alter the consistency of airway mucus have been studied in ALI for many years. For example, experimental studies implicate the mucolytic N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of phosgene-induced lung injury,36 lung injury following experimental lung transplantation,37 or following fat embolism.38 Although some of these studies attribute beneficial effects of N-acetylcysteine to its properties as antioxidant, at least some of its effects could be related to its mucolytic effects, and improved clearance of airway mucins. Indeed, several smaller clinical trials have suggested treatment with N-acetylcysteine for patients suffering from ALI.39,40 Our studies implicating NF-κB in the transcriptional induction of MUC5AC during ALI suggest that NF-κB inhibitors would be an appropriate pharmacological approach to dampen pulmonary MUC5AC production during ALI. Other studies have shown a critical role of nucleotide signaling in the secretion of mucins41 or the activation of NFκB. These studies implicate the nucleotide P2Y2 receptor in nucleotide release.42 Moreover, a recent study indicates that intracellular vesicles of Muc5ac also contain high concentrations of nucleotides. Together, these findings could lead to a feed-forward loop with release of Muc5ac, and concomitant nucleotides release could lead to further increases of Muc5ac via stimulation of P2 receptors.43 Similarly, other studies have shown that ALI is associated with the release of nucleotides, particularly ATP.44,45 Important tissue sources for nucleotide during ALI include pulmonary epithelia,46,47 vascular endothelia,48 inflammatory cells,49,50 or platelets.51 Other studies provide strong evidence that the A3 adenosine receptor contributes to mucin secretion during allergic airway disease.52 As such, pharmacological inhibitors of the P2Y2 or the A3 adenosine receptor could be used as a pharmacological strategy to dampen mucin secretion during ALI.53,54 Given that nucleotide signaling enhances pulmonary inflammation55,56 and that MUC5AC release goes along with an increase in extracellular nucleotides,43 it is intriguing to speculate that MUC5AC release could contribute to lung inflammation by increasing the concentration of nucleotides in the airway. For example, several studies have shown that pulmonary nucleotides can function as a find-me signal for inflammatory cells.57 An alternative hypothesis on how MUC5AC functions to enhance lung inflammation could include a potential role as cytokine “sponge”. It is conceivable that by binding with inflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, their half-life in the broncho-alveolar compartment could be prolonged, thereby resulting in enhanced lung inflammation and enhanced neutrophil trafficking. However, the present studies do not yet allow a definitive conclusion on the mechanism of how MUC5AC induces lung inflammation during ALI.

In summary, the present study provides the first in vivo evidence that the endogenous production of MUC5AC has a detrimental role during experimentally induced lung injury. Indeed, the present findings implicate inhibitors of MUC5AC induction or secretion in the treatment of ALI. Future challenges aimed towards translating these findings from models of VILI in mice towards the treatment of patients will have to be directed towards further defining and examining such pharmacological interventions.

METHODS

Cell culture

Human bronchial epithelial cells (Calu-3 or A549) were cultured as described previously.58,59 Both cell lines express MUC5AC as shown previously60–62

In vitro stretch model

Human bronchial epithelial cells were submitted to cyclic mechanical stretch as described previously.29 In short, Calu-3 human bronchial epithelial cells were plated on BioFlex culture plates collagen type I (BF-3001C; FlexCell International, Hillsborough, NC) and allowed to attach and grow to ~80% confluence. The medium was changed to Minimum Essential Medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum. Plates were then placed on a FlexCell FX-4000T Tension Plus System and stretched at 20% stretch maximum, 0.7% stretch minimum, sine wave 2 s, on 2 s off. Supernatants were collected at indicated time points, flash-frozen, and stored at −80 ° C for further analysis. In controls, supernatants from Calu-3 human epithelia cultured under similar conditions at rest (without application of cyclic stretch) were used. In duplicate wells, cells adherent to the plates were used for transcriptional analysis (see below).

Murine mechanical ventilation

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Colorado and are in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use of live animals. Mice gene-targeted for Muc5ac16 or corresponding littermate controls were matched according to sex, age, and weight. Muc5ac-deficient mice were generated by the laboratory of Christopher Evans (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). The correct genotype was identified by real-time reverse transcriptase–PCR and real-time PCR. ALI was induced with mechanical ventilation utilizing high inspiratory pressure levels (45 mbar, positive-end expiratory pressure 3 mbar) during pressure-controlled ventilation. In short, animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (70 mg kg−1 intrapentoneally for induction; 20 mg kg−1 h−1 for maintenance) and placed on a temperature-controlled heated table (RT, Effenberg, Munich, Germany) with a rectal thermometer probe attached to a thermal feedback controller to maintain body temperature at 37 °C. In addition, all animals were monitored with an electrocardiogram (Hewlett Packard, Böblingen, Germany). Fluid replacement was performed with normal saline, 0.05 ml h −1 intraperitoneally Tracheotomy and mechanical ventilation was performed as described previously.29,30 In short, the tracheal tube was connected to a mechanical ventilator (Servo 900C, Siemens, Germany; with pediatric tubing). Mice were ventilated in a pressure-controlled ventilation mode at 45 mbar inspiratory pressure levels over indicated time periods. Respiratory rate and inspiratory to expiratory time ratios (I:E ratios) were adjusted based on arterial blood gas sampling obtained by carotid artery catheter in control animals to maintain a carbon dioxide partial pressure between 35 and 40 mm Hg and a pH between 7.35 and 7.40. For survival studies, mice were ventilated under deep general anesthesia until a cardiac standstill was observed in the surface electrocardiogram. All animals were ventilated with 100% inspired oxygen. In subsets of experiments, mice were treated with the IKK-16 (30 mg kg −1 intraperitoneally, Tocris, Bristol, UK), a highly specific inhibitor of NF-κB.

Human BAL samples

BAL was collected in both studies as described previously.63. In short, 160 ml in 20-ml aliquots was instilled into the trachea with gentle suctioning after each aliquot. Samples were stored at −80 °C for subsequent assays. After approval by the Internal Review Board, archived BAL samples from patients with ALI and non-intubated, non-ventilated healthy controls were analyzed. ALI diagnoses was established according to the American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS.64

MUC5AC protein measurements

MUC5AC protein content was measured utilizing custom-made ELISA.65 The semi-quantitative measurements were performed by ElisaTech (Aurora, CO), with MS-551-PABX (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA) as coating antibody and MS-145-B1 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA) for detection.

Microarray analysis

Transcriptional profile of human bronchiolar epithelial cells (Calu-3) subjected to cyclic mechanical stretch (18 h) was compared with that of unstretched cells using quantitative gene chip expression arrays as described previously.66 RNA was isolated from cell lysates using a spin column according to manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, RNeasy mini spin columns). Samples were analyzed using a human genome U133 Plus 2.0 array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

Transcriptional analysis

Transcriptional changes were quantified by microarray using a human genome U133 Plus 2.0 array (Affymetrix) or real-time reverse transcriptase–PCR (iCycler; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) as described. 66,67 RNA was isolated as described previously (Qiagen).68–70 Fold change in mRNA levels were determined as described.28,69,71 Primer sets (sense sequence and antisense sequence, respectively) for the following genes were: Muc5ac (5′-CCA TGC AGA GTC CTC AGA ACA A-3′, 5′-TTA CTG GAA AGG CCC AAG CA-3′); Muc5b (5′-TGT ACT GCC CCC AGG ATG GGC-3′, 5′-AGC TCA GCT CTG CCT GAC CCT-3′); Muc2 (5′-TGC CCC TGG CTA TGA CGT CTG T-3′,5′-CCA CCC TCC CGG CAA ACA CA-3′); Cxcl1 (5′-CCA GAG CTT GAA GGT GTT GC-3′, 5′-TCT GAA CCA AGG GAG CTT CA-3′); and Cxcl2 (5′-TTC ATG GAA GGA GTG TGC AT-3′, 5′-ACA CGA AAA GGC ATG ACA AA-3′). In case of human cell samples, the following primer sets were used: MUC5AC (5′-CAG CCA CGT CCC CTT CAA TA-3′, 5′-ACC GCA TTT GGG CAT CC-3′). Each target sequence was amplified using increasing numbers of cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 58 °C for 0.5 min, 72 °C for 1 min. β-actin mRNA (murine: sense primer, 5′-ACA TTG GCA TGG CTT TGT TT-3′ and antisense primer, 5′-GTT TGC TCC AAC CAA CTG CT-3′; human: sense primer, 5′-GGT GGC TTT TAG GAT GGC AAG-3′ and antisense primer, 5′-ACT GGA ACG GTG AAG GTG ACA G-3′) was amplified in identical reactions to control for the amount of starting template. Levels and fold change in mRNA were determined as described previously. 29,69,71

PCR-Array

In a subset of experiments, the expression of different chemokines and cytokines and their corresponding receptors were analyzed. RNA was isolated from control animals and mice submitted to VILI, followed by extraction of total RNA using RNeasy mini spin columns (Qiagen). Gene expression was examined with the mouse RT2 profiler PCR arrays (PAMM-11; SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) using cDNA (Reaction Ready First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit; SABiosciences). Fold changes in gene expression were calculated in mice submitted to VILI relative to control animals with the same genotype (Muc5ac+/+-VILI vs. Muc5ac+/+-Control and Muc5ac−/−-VILI vs. Muc5ac−/−-Control). The software for this calculation was provided by the manufacturer of the PCR-Array (http://www.sabiosciences.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php).

Immunohistochemistry

To examine the influence of mechanical ventilation on pulmonary Muc5ac expression, mice were ventilated in a pressure-controlled fashion over indicated time periods. Mice were euthanized, and the lungs were perfused via the right ventricle with 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. Lungs were subsequently removed and stained with chicken anti-mouse polyclonal Muc5ac antibody as described previously.72 Preimmune sera and control tissue were used at identical concentrations and staining conditions as the target primary antibodies. As secondary, a goat anit-chicken antibody was used (AlexaFluor 488, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY).

BAL in mice

To obtain BAL fluid from experimental mice, the tracheal tube was disconnected from the mechanical ventilator, and the lungs were lavaged three times with 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. All removed fluid was centrifuged immediately and the supernatant was aliquoted for measurement of albumin concentration.

Protein analysis

MPO, Cxcl1, and IL-6 content of the murine lung were quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), then normalized to total protein content of the sample. Albumin content of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was determined by ELISA (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX). After approval by the IRB, MUC5AC protein was measured in BAL samples from patients with ALI and non-ventilated controls utilizing semi-quantitative ELISA by ElisaTech (Aurora, CO).

Wet-to-dry ratios

Wet-to-dry ratios were measured as previously described.73,74 In short, following ventilation with indicated settings, lungs were excised en bloc. The weight was obtained immediately to prevent evaporative fluid loss of the tissues. Lungs were then lyophilized for 48 h, and the dry weight was measured. Wet-to-dry ratios were then calculated as mg water per mg of dry tissue.

Blood gas analysis

To assess pulmonary gas exchange, blood gas analyses were performed in subsets of experiments by obtaining arterial blood via a carotid artery catheter as described previously.75,76 Analysis was performed immediately after collection with the I-STAT analyzer (Abbott, Abbott Park, IL) and the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) was measured, in addition to arterial partial carbon dioxide pressure and pH-values.

Histopathological evaluation of ALI

Following ventilation at indicated settings, the mice were euthanized and lungs were fixed by instillation of 10% formaldehyde solution via the tracheal cannula at a pressure of 20 mbar. Lungs were then embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff staining. Two random tissue sections from four different lungs in each group were examined by an investigator who was blinded to the genetic background/treatment of the mice. For each subject (alveolar congestion, hemorrhage, neutrophil aggregation, and hyline membranes), a five-point scale was applied: 0 = minimal (little) damage, 1 + =mild damage, 2 + = moderate damage, 3 + = severe damage, and 4 + = maximal damage. Points were added up and are expressed as median ± s.d. (n = 4)28 (see Supplementary Table S3 online).

Flow cytometry of pulmonary tissue and BAL

After harvest of BAL fluid, the lungs were excised. Tissue was digested with collagenase VIII (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO), filtered, and viability assessed before staining. Cells from indicated compartments were incubated with antimouse Fc-block (CD16/32: clone 93; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and fluorescently labeled antibodies against: Siglec-F (clone E50-2440; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); CD11c (clone N418), Ly6G (clone 1A8; Biolegend, San Diego, CA); MHCII (clone M5/114.15.2), CD45.2 (clone 104), CD11b (clone M1/70), F4/80 (clone BM8) (eBioscience); or corresponding isotype controls. Live cells were acquired using a LIVE/DEAD fixable aqua dead cell stain (Invitrogen). Cells were washed and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and analysed using a FACS Canto system (Beckton-Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Post analyses were performed using FLOWJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Percentage of live CD45+ cells of each population were calculated and multiplied by the total cell number retrieved from organ harvest to calculate actual cell number of distinct sub-populations.

MUC5AC suppression with RNA interference

Calu-3 were grown in 60-mm Petri dishes. Different sets of siRNA directed against human MUC5AC were designed using standard molecular tools, synthesized by InVivogen (San Diego, CA), and tested with reverse transcriptase–PCR for their efficiency to suppress MUC5AC expression at different concentrations. Highest efficiencies were found with 5′-ACCTCGTGTCAAAGTGTGCCTGCGTCTACATCAAGAGTGTAGACGCAGGCACACTTTGACACTTdTdT-3′. As non-specific control, the sense strand of the MUC5AC oligoribonucleotide was used under identical conditions. Calu-3 loading was accomplished using standard conditions of Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), when cells had reached 40–60% confluence.

In vitro PMN transmigration

Isolation of human PMNs was performed by Histopaque 1077 gradient as described.33,77 In all, 1×10 PMN were added to the insert of a Transwell plate (6.5 polyester, 3 µm pore size; Costar, Tewksbury, MA) chamber in the presence of supernatant from cells that were transfected with a siRNA directed against MUC5AC (MUC5ACko) or a control siRNA (MUC5ACscr). Formyl-methinyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (Sigma Aldrich) was added at a final concentration of 1 mm to the lower chamber.78 In a subset of experiments, Calu-3 pulmonary epithelial cells were cultured on inverted 6.5 mm polyester permeable Transwell membranes (3.0 µm pore; Costar) as an additional barrier as previously described.33 The assay was incubated at 37 ° C for 45 mins, when no cell barrier was present and for 1.5 h in the presence of a cell barrier. Numbers of transmigrated PMN were determined by MPO assay, as described.33,79

Data analysis

All data are presented as mean ± s.d. from 4–6 animals per condition. We performed statistical analysis using Student’s t-test (two sided, α < 0.05) or analysis of variance to determine group differences. To test survival differences, we used the Mantel–Cox test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

MUC5AC content in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of patients with acute lung injury (ALI). Human BAL fluid was obtained from patients with ALI and MUC5AC protein content was assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results were compared with samples collected from unventilated subjects without lung injury, who were otherwise healthy. Results are presented as mean±s.d.(n= 5 per group).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The present review is supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL0921, R01-DK083385 and R01HL098294 to H.K.E., HL090669 to G.P.D., and grants by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America to H.K.E., E.N.M. and C.M.A. and a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) research fellowship to M.K.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/mi

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenfeld GD, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belperio JA, et al. Critical role for CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands during the pathogenesis of ventilator-induced lung injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:1703–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI15849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reutershan J, Cagnina RE, Chang D, Linden J, Ley K. Therapeutic anti-inflammatory effects of myeloid cell adenosine receptor A2a stimulation in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1254–1263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reutershan J, et al. Critical role of endothelial CXCR2 in LPS-induced neutrophil migration into the lung. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:695–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI27009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin TR. Neutrophils and lung injury: getting it right. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:1603–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI17302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham E, Carmody A, Shenkar R, Arcaroli J. Neutrophils as early immunologic effectors in hemorrhage- or endotoxemia-induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2000;279:L1137–L1145. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azoulay E, et al. Deterioration of previous acute lung injury during neutropenia recovery. Crit. Care Med. 2002;30:781–786. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baughman RP, Gunther KL, Rashkin MC, Keeton DA, Pattishall EN. Changes in the inflammatory response of the lung during acute respiratory distress syndrome: prognostic indicators. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;154:76–81. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fahy JV, Dickey BF. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2233–2247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:245–278. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Zhao YH, Di YP, Wu R. Characterization of human mucin 5B gene expression in airway epithelium and the genomic clone of the amino-terminal and 5′-flanking region. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2001;25:542–553. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young HW, et al. Central role of Muc5ac expression in mucous metaplasia and its regulation by conserved 5′ elements. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:273–290. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0460OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans CM, et al. Mucin is produced by clara cells in the proximal airways of antigen-challenged mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2004;31:382–394. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0060OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasnain SZ, et al. Muc5ac: a critical component mediating the rejection of enteric nematodes. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:893–900. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galaup A, et al. Protection against myocardial infarction and no-reflow through preservation of vascular integrity by angiopoietin-like 4. Circulation. 2012;125:140–149. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.049072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles MR, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:571–577. doi: 10.1172/JCI15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seibold MA, et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1503–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckle T, Grenz A, Laucher S, Eltzschig HK. A2B adenosine receptor signaling attenuates acute lung injury by enhancing alveolar fluid clearance in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3301–3315. doi: 10.1172/JCI34203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schingnitz U, et al. Signaling through the A2B adenosine receptor dampens endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J. Immunol. 2010;184:5271–5279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reutershan J, Vollmer I, Stark S, Wagner R, Ngamsri KC, Eltzschig HK. Adenosine and inflammation: CD39 and CD73 are critical mediators in LPS-induced PMN trafficking into the lungs. FASEB J. 2009;23:473–482. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-119701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujisawa T, Velichko S, Thai P, Hung LY, Huang F, Wu R. Regulation of airway MUC5AC expression by IL-1beta and IL-17A; the NF-kappaB paradigm. J. Immunol. 2009;183:6236–6243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He BJ, et al. Oxidation of CaMKII determines the cardiotoxic effects of aldosterone. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1610–1618. doi: 10.1038/nm.2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boucher RC. Airway surface dehydration in cystic fibrosis: pathogenesis and therapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2007;58:157–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.071905.105316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boucher RC. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis–a sticky business. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1560–1561. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1014191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans CM, Kim K, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF. Mucus hypersecretion in asthma: causes and effects. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2009;15:4–11. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32831da8d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckle T, Fullbier L, Grenz A, Eltzschig HK. Usefulness of pressure-controlled ventilation at high inspiratory pressures to induce acute lung injury in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008;295:L718–L724. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90298.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckle T, et al. Identification of ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 in innate protection during acute lung injury. J. Immunol. 2007;178:8127–8137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koeppen M, Eckle T, Eltzschig HK. Pressure controlled ventilation to induce acute lung injury in mice. J. Vis. Exp. doi: 10.3791/2525. pii: 25252011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li D, Gallup M, Fan N, Szymkowski DE, Basbaum CB. Cloning of the amino-terminal and 5′-flanking region of the human MUC5AC mucin gene and transcriptional up-regulation by bacterial exoproducts. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6812–6820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waelchli R, et al. Design and preparation of 2-benzamido-pyrimidines as inhibitors of IKK. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenberger P, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent induction of netrin-1 dampens inflammation caused by hypoxia. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:195–202. doi: 10.1038/ni.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donaldson SH, Bennett WD, Zeman KL, Knowles MR, Tarran R, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance and lung function in cystic fibrosis with hypertonic saline. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:241–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casalino-Matsuda SM, Monzon ME, Day AJ, Forteza RM. Hyaluronan fragments/CD44 mediate oxidative stress-induced MUC5B up-regulation in airway epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009;40:277–285. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0073OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sciuto AM, Strickland PT, Kennedy TP, Gurtner GH. Protective effects of N-acetylcysteine treatment after phosgene exposure in rabbits. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;151(3 Part 1):768–772. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.3.7881668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inci I, Zhai W, Arni S, Hillinger S, Vogt P, Weder W. N-acetylcysteine attenuates lung ischemia-reperfusion injury after lung transplantation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007;84:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.03.082. discussion 246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu DD, Kao SJ, Chen HI. N-acetylcysteine attenuates acute lung injury induced by fat embolism. Crit. Care Med. 2008;36:565–571. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000299737.24338.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernard GR, et al. A trial of antioxidants N-acetylcysteine, procysteine in ARDS The Antioxidant in ARDS Study Group. Chest. 1997;112:164–172. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suter PM, Domenighetti G, Schaller MD, Laverriere MC, Ritz R, Perret C. N-acetylcysteine enhances recovery from acute lung injury in man. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Chest. 1994;105:190–194. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.1.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreda SM, et al. Coordinated release of nucleotides and mucin from human airway epithelial Calu-3 cells. J. Physiol. 2007;584(Part 1):245–259. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korcok J, Raimundo LN, Du X, Sims SM, Dixon SJ. P2Y6 nucleotide receptors activate NF-kappaB and increase survival of osteoclasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:16909–16915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410764200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kreda SM, et al. Receptor-promoted exocytosis of airway epithelial mucin granules containing a spectrum of adenine nucleotides. J. Physiol. 2010;588(Part 12):2255–2267. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.186643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eckle T, Koeppen M, Eltzschig HK. Role of extracellular adenosine in acute lung injury. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:298–306. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00022.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eltzschig HK. Adenosine: an old drug newly discovered. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:904–915. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b060f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad S, et al. Lung epithelial cells release ATP during ozone exposure: signaling for cell survival. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;39:213–226. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Button B, Picher M, Boucher RC. Differential effects of cyclic and constant stress on ATP release and mucociliary transport by human airway epithelia. J. Physiol. 2007;580(Part. 2):577–592. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faigle M, Seessle J, Zug S, El Kasmi KC, Eltzschig HK. ATP release from vascular endothelia occurs across Cx43 hemi channels and is attenuated during hypoxia. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eltzschig HK, et al. ATP release from activated neutrophils occurs via connexin 43 and modulates adenosine-dependent endothelial cell function. Circ. Res. 2006;99:1100–1108. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250174.31269.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eltzschig HK, Macmanus CF, Colgan SP. Neutrophils as Sources of Extracellular Nucleotides: Functional Consequences at the Vascular Interface. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2008;18:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weissmuller T, et al. PMNs facilitate translocation of platelets across human and mouse epithelium and together alter fluid homeostasis via epithelial cell-expressed ecto-NTPDases. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3682–3692. doi: 10.1172/JCI35874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young HW, Sun CX, Evans CM, Dickey BF, Blackburn MR. A3 adenosine receptor signaling contributes to airway mucin secretion after allergen challenge. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006;35:549–558. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0060OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohsenin A, Mi T, Xia Y, Kellems RE, Chen JF, Blackburn MR. Genetic removal of the A2A adenosine receptor enhances pulmonary inflammation, mucin production, and angiogenesis in adenosine deaminase-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2007;293:L753–L761. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00187.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cicko S, et al. Purinergic receptor inhibition prevents the development of smoke-induced lung injury and emphysema. J. Immunol. 2010;185:688–697. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsuyama H, et al. Acute lung inflammation and ventilator-induced lung injury caused by ATP via the P2Y receptors: an experimental study. Respir. Res. 9:792008. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Idzko M, et al. Extracellular ATP triggers and maintains asthmatic airway inflammation by activating dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2007;13:913–919. doi: 10.1038/nm1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elliott MR, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liedtke CM, Wang X, Smallwood ND. Role for protein phosphatase 2A in the regulation of Calu-3 epithelial Na+-K+-2Cl-, type 1 co-transport function. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:25491–25498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haeberle HA, et al. Oxygen-independent stabilization of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1 during RSV infection. PLoS ONE. 3:33522008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hauber HP, Goldmann T, Vollmer E, Wollenberg B, Zabel P. Effect of dexamethasone and ACC on bacteria-induced mucin expression in human airway mucosa. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;37:606–616. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kreda SM, et al. Receptor-promoted exocytosis of airway epithelial mucin granules containing a spectrum of adenine nucleotides. J. Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 12):2255–2267. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.186643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fischer BM, Voynow JA. Neutrophil elastase induces MUC5AC gene expression in airway epithelium via a pathway involving reactive oxygen species. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002;26:447–452. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.4.4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paine R, 3rd, et al. A randomized trial of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for patients with acute lung injury. Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:90–97. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822d7bf0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernard GR, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994;149(3 Part 1):818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seibold MA, et al. The concentration of MUC5AC is higher in the air space of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) subjects and is associated with a disease susceptibility variant (Ala497Val) in MUC5AC. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181:A24932012. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Synnestvedt K, et al. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:993–1002. doi: 10.1172/JCI15337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eltzschig HK, et al. Coordinated adenine nucleotide phosphohydrolysis and nucleoside signaling in posthypoxic endothelium: role of ectonucleotidases and adenosine A2B receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:783–796. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eckle T, Kohler D, Lehmann R, El Kasmi KC, Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Is Central to Cardioprotection: A New Paradigm for Ischemic Preconditioning. Circulation. 2008;118:166–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.758516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eckle T, et al. Cardioprotection by ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) and A2B adenosine receptors. Circulation. 2007;115:1581–1590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grenz A, et al. The Reno-Vascular A2B Adenosine Receptor Protects the Kidney from Ischemia. PLoS Med. 5:e1372008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kohler D, et al. CD39/ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 provides myocardial protection during cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2007;116:1784–1794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shekels LL, Lyftogt C, Kieliszewski M, Filie JD, Kozak CA, Ho SB. Mouse gastric mucin: cloning and chromosomal localization. Biochem J. 1995;311(Part 3):775–785. doi: 10.1042/bj3110775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eltzschig HK, et al. HIF-1-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) in hypoxia. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1493–1505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thompson LF, et al. Crucial role for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1395–1405. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koeppen M, Eckle T, Eltzschig HK. Selective deletion of the A1 adenosine receptor abolishes heart-rate slowing effects of intravascular adenosine in vivo. PLoS One. 4:e67842009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koeppen M, Eckle T, Eltzschig HK. Pressure controlled ventilation to induce acute lung injury in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koeppen M, et al. Adora2b signaling on bone marrow derived cells dampens myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1245–1257. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318255793c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cronstein BN, Daguma L, Nichols D, Hutchison AJ, Williams M. The adenosine/neutrophil paradox resolved: human neutrophils possess both A1 and A2 receptors that promote chemotaxis and inhibit O2 generation, respectively. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:1150–1157. doi: 10.1172/JCI114547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reutershan J, Ley K. Bench-to-bedside review: acute respiratory distress syndrome - how neutrophils migrate into the lung. Crit Care. 2004;8:453–461. doi: 10.1186/cc2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.