Abstract Abstract

Phormia regina (the black fly) is a common Holarctic blow fly species which serves as a primary indicator taxon to estimate minimal post mortem intervals. It is also a major research model in physiological and neurological studies on insect feeding. Previous studies have shown a sequence divergence of up to 4.3% in the mitochondrial COI gene between W European and N American P. regina populations. Here, we DNA barcoded P. regina specimens from six N American and 17 W European populations and confirmed a mean sequence divergence of ca. 4% between the populations of the two continents, while sequence divergence within each continent was a ten-fold lower. Comparable mean mtDNA sequence divergences were observed for COII (3.7%) and cyt b (5.3%), but mean divergence was lower for 16S (0.4–0.6%). Intercontinental divergence at nuclear DNA was very low (≤ 0.1% for both 28S and ITS2), and we did not detect any morphological differentiation between N American and W European specimens. Therefore, we consider the strong differentiation at COI, COII and cyt b as intraspecific mtDNA sequence divergence that should be taken into account when using P. regina in forensic casework or experimental research.

Keywords: Black fly, COI, COII, cyt b, 16S, 28S, ITS2

Introduction

Forensic entomology uses the larval and pupal developmental stages of insects sampled on a corpse to estimate a minimum post-mortem interval (PMImin) of the corpse (Amendt et al. 2004, 2007). This requires i) detailed and accurate knowledge of the developmental rate of the species of forensic interest under different temperature conditions (Charabidze 2012), and ii) identification tools by which the different immature insect stadia can be identified (Catts 1992). Blowflies (family Calliphoridae) are among the most common insects found on dead bodies shortly after death. The species differ in their developmental times and have therefore a high potential for the accurate estimation of the PMImin. Unfortunately, several forensically important blow fly species can hardly be distinguished morphologically, especially in the larval and pupal stages (e.g. Catts 1992). To improve the success and reliability of identifications, a number of molecular techniques and tools have been explored to identify forensically important species (Wells and Stevens 2008, reviewed in Jordaens et al. in press).

Currently, the most popular molecular method for organismal identification is DNA barcoding, which was promoted by Hebert et al. (2003a, b) as a standardized molecular identification tool for all animals. It refers to establishing species-level identifications by sequencing a fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene, the “DNA barcode”, into a taxonomically unknown specimen and performing comparisons with a reference library of barcodes of well-identified species. COI barcodes (and other fragments of COI) indeed have been successfully applied in the identification of many calliphorid species (e.g. Wallman and Donnellan 2001, Wells and Sperling 2001, Nelson et al. 2007, Wells and Williams 2007, Harvey et al. 2008, Desmyter and Gosselin 2009, DeBry et al. 2013). Yet, COI fails to unambiguously discriminate among several calliphorid species pairs (e.g. Nelson et al. 2007, see also the Discussion) and the use of alternative identification tools (e.g. other genes) could be necessary to acquire correct identifications.

The monophyly of Calliphoridae has been questioned for many years (e.g. Griffiths 1982) and paraphyly or polyphyly was suggested by a morphology-based parsimony analysis (Rognes 1997). Nonmonophyly was also found in a molecular phylogenetic analysis of the Calyptratae with Calliphoridae being polyphyletic with respect to the Tachinidae and Rhinophoridae. Within this ‘calliphorid-tachinid-rhinophorid’ clade, the subfamily Chrysomyinae was para- or polyphyletic (Kutty et al. 2010). The Chrysomyinae comprises two tribes, Chrysomyini and Phormiini, of which the Phormiini has three genera (Table 1). Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826) (black fly) is the only species in the monotypic genus Phormia. It is a Holarctic blow fly species that is commonly found on human or animal faeces (Coffey 1966) and that is frequently found on corpses. It therefore serves as a primary species to estimate the PMImin (e.g. Byrd and Allen 2001). Further, the species also plays an important role in secondary myasis in cattle (e.g. Francesconi and Lupi 2012) and is used in maggot therapy (Knipling and Rainwater 1937).

Table 1.

Taxonomy of the subfamily Chrysomyinae (family Calliphoridae) with indication of the number of DNA sequences (the number of haplotypes is given in parentheses) for each of the species used in this study (numbers combined from this study and GenBank) and for each of the gene fragments studied. No. ind. = number of individuals; No. hapl. = number of haplotypes; No. spp. = number of species.

| Genus/species | COI | COII | 16S | cyt b | ITS2 | 28S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 251 bp | 350 bp | |||||||

| Chrysomyini | Chloroprocta Wulp, 1896 | |||||||

| Chloroprocta idioidea (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) | 2(2) | 1(1) | 1(1) | |||||

| Chrysomya Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 | ||||||||

| Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) | 3(2) | 1(1) | 2(1) | 2(1) | ||||

| Chrysomya bezziana Villeneuve, 1914 | 5(2) | 1(1) | 10(6) | 2(1) | 2(2) | |||

| Chrysomya cabrerai Kurahashi & Salazar, 1977 | 1(1) | |||||||

| Chrysomya chani Kurahashi, 1979 | 1(1) | 11(2) | ||||||

| Chrysomya chloropyga (Wiedemann, 1818) | 1(1) | 2(2) | ||||||

| Chrysomya defixa (Walker, 1856) | 1(1) | |||||||

| Chrysomya flavifrons (Aldrich, 1925) | 3(2) | 1(1) | 4(2) | |||||

| Chrysomya greenbergi Wells & Kurahashi, 1996 | 1(1) | |||||||

| Chrysomya incisularis (Macquart, 1851) | 9(2) | 2(2) | 1(1) | |||||

| Chrysomya latifrons (Malloch, 1927) | 6(2) | 1(1) | 5(1) | |||||

| Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) | 79(11) | 28(7) | 66(31) | 20(3) | 2(2) | 42(3) | 4(2) | |

| Chrysomya nigripes Aubertin, 1932 | 9(7) | 3(3) | 7(1) | |||||

| Chrysomya norrisi James, 1971 | 1(1) | 1(1) | ||||||

| Chrysomya pacifica Kurahashi, 1991 | 1(1) | 1(1) | ||||||

| Chrysomya pinguis (Walker, 1858) | 7(4) | 1(1) | 14(2) | |||||

| Chrysomya putoria (Wiedemann, 1830) | 2(2) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 2(1) | ||||

| Chrysomya rufifacies (Macquart, 1843) | 25(10) | 45(9) | 10(5) | 1(1) | 14(1) | 2(2) | ||

| Chrysomya saffranea (Bigot, 1877) | 7(2) | 1(1) | 8(2) | |||||

| Chrysomya semimetallica (Malloch, 1927) | 11(5) | 3(2) | 10(2) | |||||

| Chrysomya thanomthini Kurahashi & Tumrasvin, 1977 | 1(1) | |||||||

| Chrysomya varipes (Macquart, 1851) | 7(6) | 6(2) | 1(1) | |||||

| Chrysomya villeneuvi Patton, 1922 | 7(1) | |||||||

| Cochliomyia Townsend, 1915 | ||||||||

| Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel, 1858) | 78(73) | 65(62) | 2(1) | 90(24) | 2(1) | |||

| Cochliomyia macellaria (Fabricius, 1775) | 3(3) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 4(1) | ||||

| Compsomyiops Townsend, 1918 | ||||||||

| Compsomyiops calipes (Bigot, 1877) | 1(1) | 1(1) | ||||||

| Compsomyiops fulvicrura (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 1(1) | |||||

| Hemilucilia Brauer, 1895 | ||||||||

| Hemilucilia segmentaria (Fabricius, 1805) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 1(1) | |||||

| Hemilucilia semidiaphana (Rondani, 1850) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 1(1) | |||||

| Paralucilia Brauer & Bergenstamm, 1891 | ||||||||

| Paralucilia paraensis (Mello, 1969) | 1(1) | |||||||

| Trypocalliphora Peus, 1960 | ||||||||

| Trypocalliphora braueri (Hendel, 1901) | 1(1) | |||||||

| Phormiini | Phormia Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 | |||||||

| Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826) | 48(20) | 30(9) | 15(2) | 15(2) | 17(10) | 36(2) | 38(2) | |

| Protophormia Townsend, 1908 | ||||||||

| Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) | 17(7) | 1(1) | 2(2) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 4(2) | ||

| Protocalliphora Hough, 1899 | ||||||||

| Protocalliphora azurea (Fallen, 1817) | 2(2) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 1(1) | ||||

| Protocalliphora occidentalis Whitworth, 2003 | 1(1) | |||||||

| Protocalliphora sialia Shannon & Dobroscky, 1924 | 1(1) | 1(1) | ||||||

| Protocalliphora sp. | 1(1) | |||||||

| Total no. ind. | 339 | 194 | 95 | 39 | 32 | 263 | 66 | |

| Total no. hapl. | 180 | 108 | 42 | 9 | 20 | 55 | 21 | |

| Total no. spp. | 36 | 20 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 24 | ||

Phormia regina is a highly mobile species that is abundant in North American areas with cool spring and fall temperatures and in warmer areas, but then at higher altitudes (Hall 1948, Brundage et al. 2011). The developmental time of Phormia regina seems highly variable and could be influenced by a number of environmental variables (Kamal 1958, Greenberg 1991, Anderson 2000, Byrd and Allen 2001, Nabity et al. 2007, Núñez-Vázquez et al. 2013). Using amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP), Picard and Wells (2009) studied the population genetic structure of N American Phormia regina and found that the N American populations were panmictic but with significant temporal genetic differences within populations, even over short periods of time. They therefore suggested that part of the variation in developmental times and growth curves that was observed in laboratory studies is not only due to local environmental (i.e. laboratory) conditions, but also to differences in the genetic composition of the laboratory stocks. This finding is important for forensic sciences since it shows that forensically relevant ecological data from one population (i.e. from a forensic case) cannot be extrapolated to other populations (i.e. to other forensic cases). Interestingly, Desmyter and Gosselin (2009) found a 4.2% sequence divergence at a 304 bp COI fragment between N American and W European specimens. Subsequently, Boehme et al. (2012) found a similar sequence divergence (range: 3.5%–4.31%) at the COI barcodes between N American and W European Phormia regina specimens.

Because high COI sequence divergences are often indicating species level differentiation (e.g. Hebert et al. 2003a, b), the strong COI differentiation between N American and W European Phormia regina specimens calls for a taxonomic re-assessment. We therefore studied DNA sequence variation in mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, and examined morphological differentiation between N American and W European populations of Phormia regina to i) provide additional DNA barcodes for Phormia regina, ii) examine molecular differentiation between N American and W European specimens in other genes, and iii) assess whether the COI differentiation is correlated with morphological differentiation. The taxonomy of Phormia regina is then re-evaluated in the light of these results.

Material and methods

Specimen collection and morphological examination

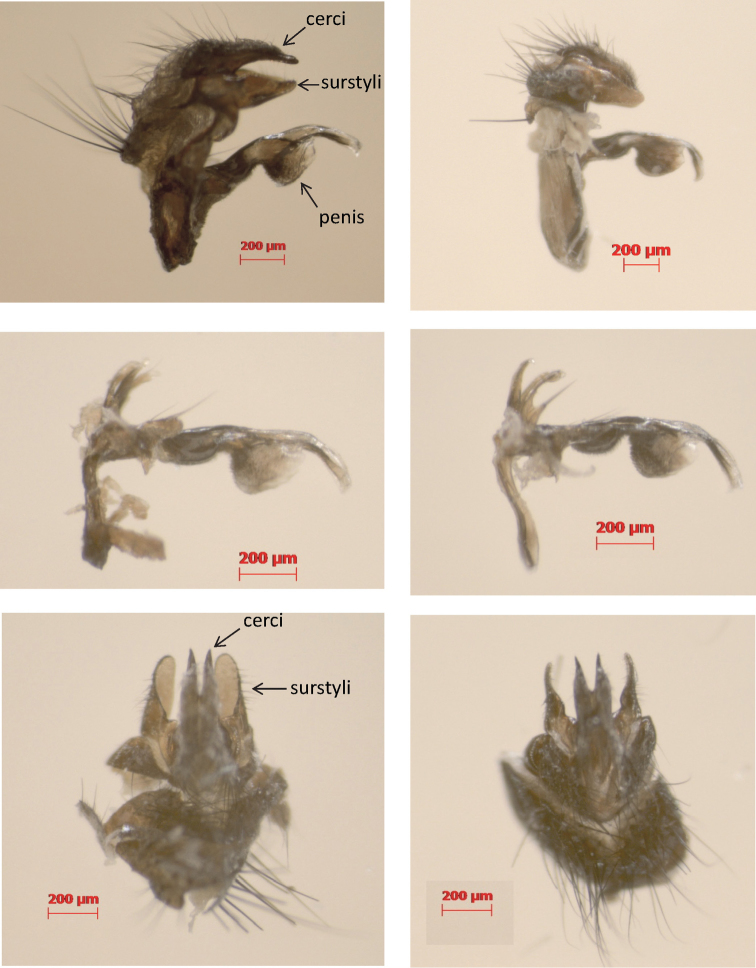

Sixty-one adult individuals of Phormia regina were captured at several localities in N America (Indiana, Texas, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming) and W Europe (Belgium, France, Germany) and stored in > 70% ethanol (Appendix 1 – Supplementary table 1). The individuals were qualitatively scored for the color of 11 external characters (Table 2). In addition, we dissected the male copulatory organs of five W European and five N American individuals to study the general shape of the penis, cerci and surstyli (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Color scoring of eleven external morphological characters of adult W European and N American Phormia regina.

| Character | W Europe and N America |

|---|---|

| calypters | white |

| first spiraculum | white to yellow |

| thoracic dorsum | metallic green-bluish to dark green |

| scutellum | dark green |

| legs | black |

| abdomen | metallic green-bluish |

| facial ridge | red-brown |

| gena | black |

| postgena | black |

| first antennal segment | dark-brown to black |

| second antennal segment | white-grey |

Figure 1.

Lateral (top) and dorsal (bottom) view of the male copulatory organs of Phormia regina from W Europe (left) and N America (right) with a detail of the penis (middle).

DNA sequence analysis

DNA was extracted from on one or two legs. The remaining parts of the vouchers are kept at the NICC (National Institute of Criminalistics and Criminology – Brussels, Belgium) as pinned material. Genomic DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel). A fragment of 721 bp from the 5’-end of the COI gene, including the standard barcode region (Hebert et al. 2003a, b), was amplified using primer pair TY-J-1460 and C1-N-2191 (Sperling et al. 1994, Wells and Sperling 2001). Five other DNA markers were sequenced for a more limited set of samples (Appendix 1 – Supplementary table 1). Fragments of the mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA (16S), cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COII), and cytochrome b (cyt b) genes, and of the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) and fragment D1–D2 of the 28S ribosomal RNA (28S) were amplified using primer pairs 16Sf.dip/16Sr.dip (Kutty et al. 2007), C2-J-3138/TK-N-3775 (Wells and Sperling 2001), CB1-SE/PDR-WR04 (Ready et al. 2009), ITS2F.dip/ITS2R (Song et al. 2008) and D1F/D2R (Stevens and Wall 2001), respectively.

Each 25 µl PCR reaction was prepared using 1 × PCR buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.4 μM of each primer, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Platinum®, Invitrogen), 2–4 µl DNA template (DNA was stored in 100 µl of elution buffer) and enough mQ-H2O to complete the total PCR reaction volume. The thermal cycler program consisted of an initial denaturation step of 4 min at 94 °C, followed by 30–40 cycles of 45–60 s at 94 °C, 30–60 s at a fragment depending annealing temperature and 90 s at 72 °C; with a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. The annealing temperatures were 45 °C for COI and COII, 48 °C for 16S and cyt b, 50 °C for ITS-2 and 55 °C for 28S. PCR products were cleaned using the NucleoFast96 PCR® kit (Macherey-Nagel) and bidirectionally sequenced on an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using the BigDye® Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit v3.1. Together with the Phormia regina specimens we also collected several Protophormia terraenovae specimens that were also sequenced to increase the number of material for comparison (Appendix 1 – Supplementary table 1). Sequences were assembled in SeqScape v2.5 (Applied Biosystems) and deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KF908069–KF908124 (COI), KF908126–KF908152 (COII), KF908153–KF908169 (cyt b), KF908054–KF908068 (16S), KF908170–KF908203 (ITS2), and KF908204–KF908237 (28S).

Phormiini and its sister clade Chrysomyini form the Chrysomyinae (Singh and Wells 2011a, b). We therefore downloaded from GenBank (and for all genes) all available sequences (at 11 July 2013) of the Phormiini (genera Phormia, Protophormia and Protocalliphora) and of the Chrysomyini (genera Chloroprocta, Chrysomya, Cochliomyia, Compsomyiops, Hemilucilia, Paralucilia and Trypocalliphora) to allow comparison with closely related taxa (Table 1). Sequences were aligned in MAFFT v7 (Katoh and Standley 2013). Sequences with > 5 ambiguous positions were discarded and each dataset was trimmed to equal sequence length (Table 3). The 16S dataset was trimmed at 251 bp and at 350 bp to yield a higher number of Chrysomyinae haplotypes for the latter dataset (i.e. 22 vs. 42 unique haplotypes; six species in the ingroup for both datasets). Alignments are available as fasta files in the online Appendix 2 text file. Unique sequences (haplotypes) were selected in DAMBE5 (Xia 2013). Nucleotide sequence divergences within and between species (based on the haplotypes) were calculated using the uncorrected p-distances in MEGA v5.05 (Tamura et al. 2011). For these calculations we excluded haplotypes that were not identified to the species level (one Protocalliphora sp. for COI) or that were most likely identification errors (for details see the Results). MEGA v5.05 was also used to construct Neighbour-Joining (NJ) trees (Saitou and Nei 1987) using the p-distances with complete deletion of positions with ambiguities and alignment gaps (indels). Relative branch support was evaluated with 1000 bootstrap replicates (Felsenstein 1985). In all analyses, several Lucilia spp. or Calliphora spp. sequences from GenBank were added as outgroups, and for COI we also used Lucilia sericata NICC0390 as outgroup (GenBank accession number KF908125). Author names of all species are provided in Table 1.

Table 3.

Description of the Phormia regina and other Chrysomyinae DNA sequences (including those retrieved from GenBank) for each of the gene fragments.

| Marker | COI | COII | 16S | cyt b | ITS2 (without indels) | 28S (without indels) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 251 bp | 350 bp | ||||||

| Fragment size (bp) | 655 | 472 | 251 | 350 | 512 | 380 (224) | 633 (592) |

| Phormia regina | |||||||

| Total | |||||||

| No of sequences | 50 | 30 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 36 | 37 |

| No of haplotypes | 20 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 2 |

| North America (NA) | |||||||

| No of sequences | 27 | 27 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 25 | 23 |

| No of haplotypes | 14 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| Mean intra-NA distances (%) | 0.004 | 0.004 | - | 0.004 | 0.005 | - | 0.002 |

| SE | 0.001 | 0.002 | - | 0.003 | 0.002 | - | 0.002 |

| min. – max. | 0.002–0.008 | 0.002–0.006 | - | 0.003–0.006 | 0.002–0.008 | - | 0.002 |

| Europe (EU) | |||||||

| No of sequences | 23 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 14 |

| No of haplotypes | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4(2) | 1 |

| Mean intra-EU distances (%) | 0.003 | 0.002 | - | - | 0.002 | 0.002 | - |

| SE | 0.001 | 0.002 | - | - | 0.007 | 0.002 | - |

| min. – max. | 0.002–0.008 | 0.002 | - | - | 0.002–0.010 | 0.002 | - |

| Mean p-distance between NA and EU | 0.04 | 0.037 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.053 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SE | 0.007 | 0.008 | - | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| min. – max. | 0.036–0.044 | 0.034–0.042 | 0.004 | 0.005–0.009 | 0.047–0.061 | 0–0.004 | 0–0.002 |

| Other Chrysomyinae | |||||||

| Mean intraspecific p-distance | 0.005 | 0.014 | 0.028 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| SE | 0.009 | 0.014 | 0.009 | - | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| min. – max. | 0–0.042 | 0–0.037 | 0.018–0.036 | 0.014 | 0.002–0.005 | 0.004–0.015 | 0–0.010 |

| Mean interspecific p-distance | 0.066 | 0.046 | 0.038 | 0.023 | 0.079 | 0.085 | 0.007 |

| SE | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.002 |

| min. – max. | 0.011–0.113 | 0.002–0.135 | 0.03–0.075 | 0.023–0.057 | 0.073–0.141 | 0.009–0.166 | 0–0.015 |

Results

Morphology

We did not detect morphological differences between N American and W European Phormia regina specimens in the 11 external color characters that we scored (Table 2). Also the male copulatory organs of W European and N American Phormia regina specimens were indistinguishable (Figure 1).

DNA sequence analysis

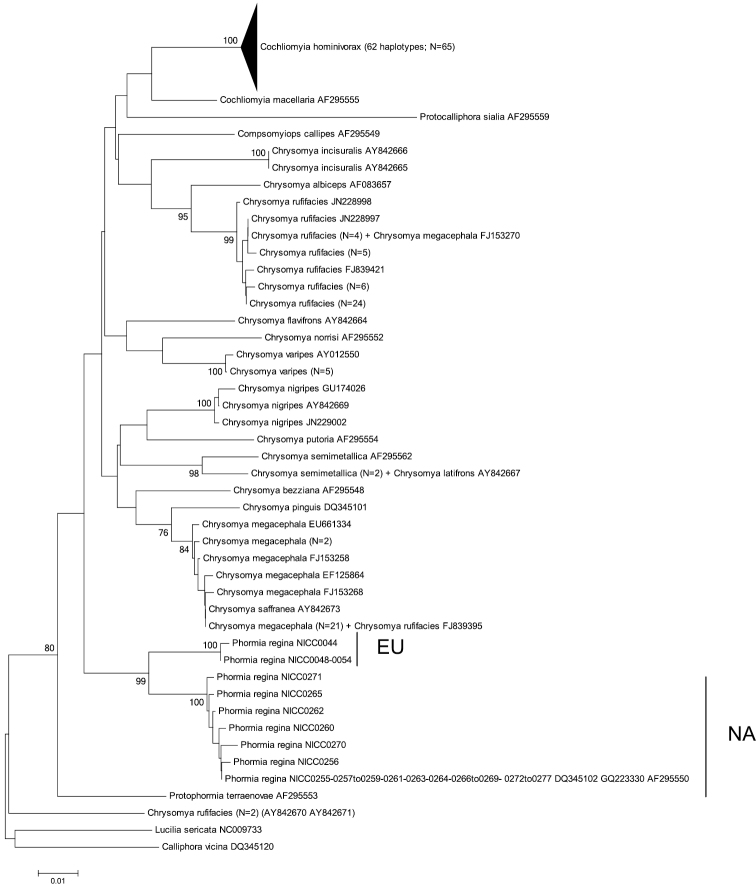

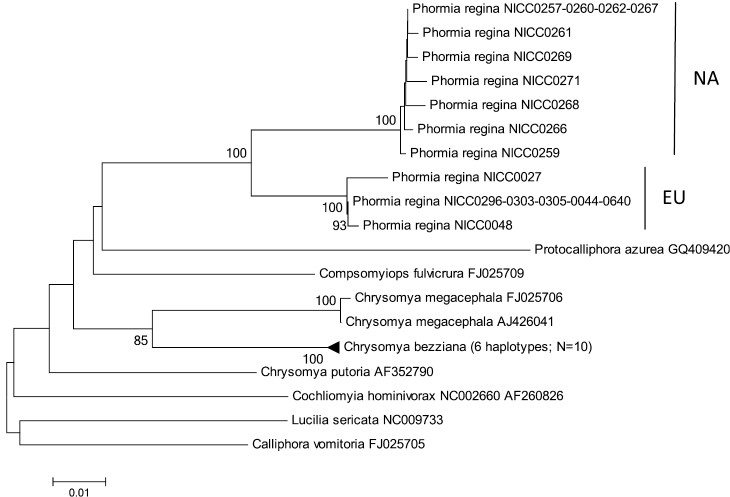

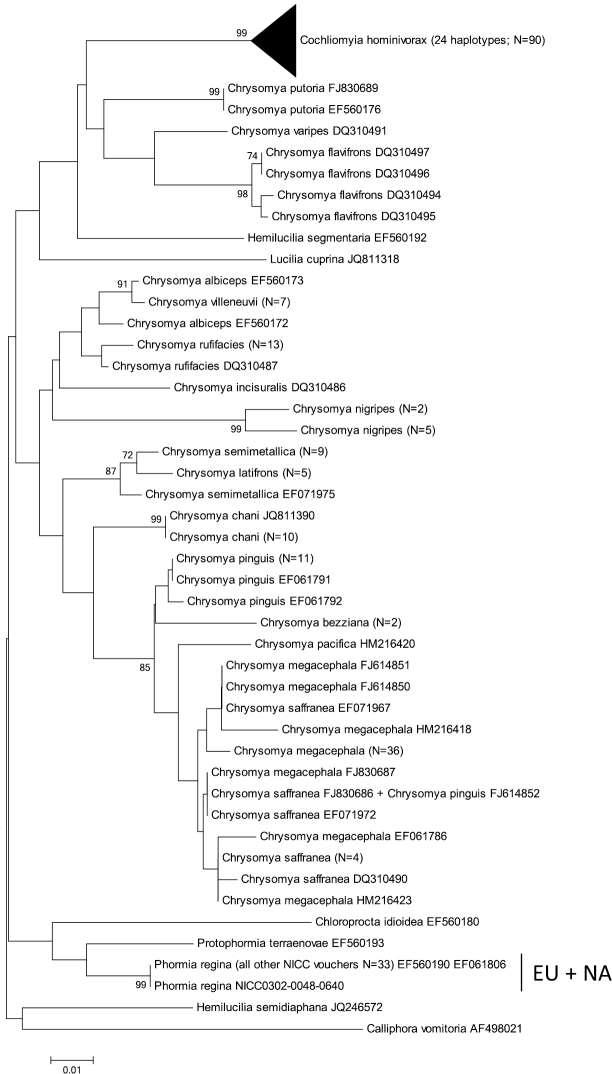

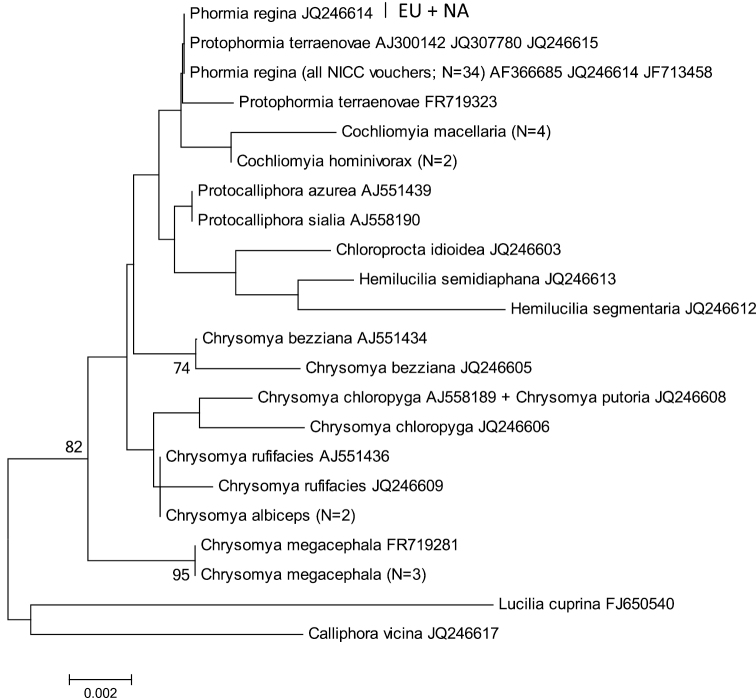

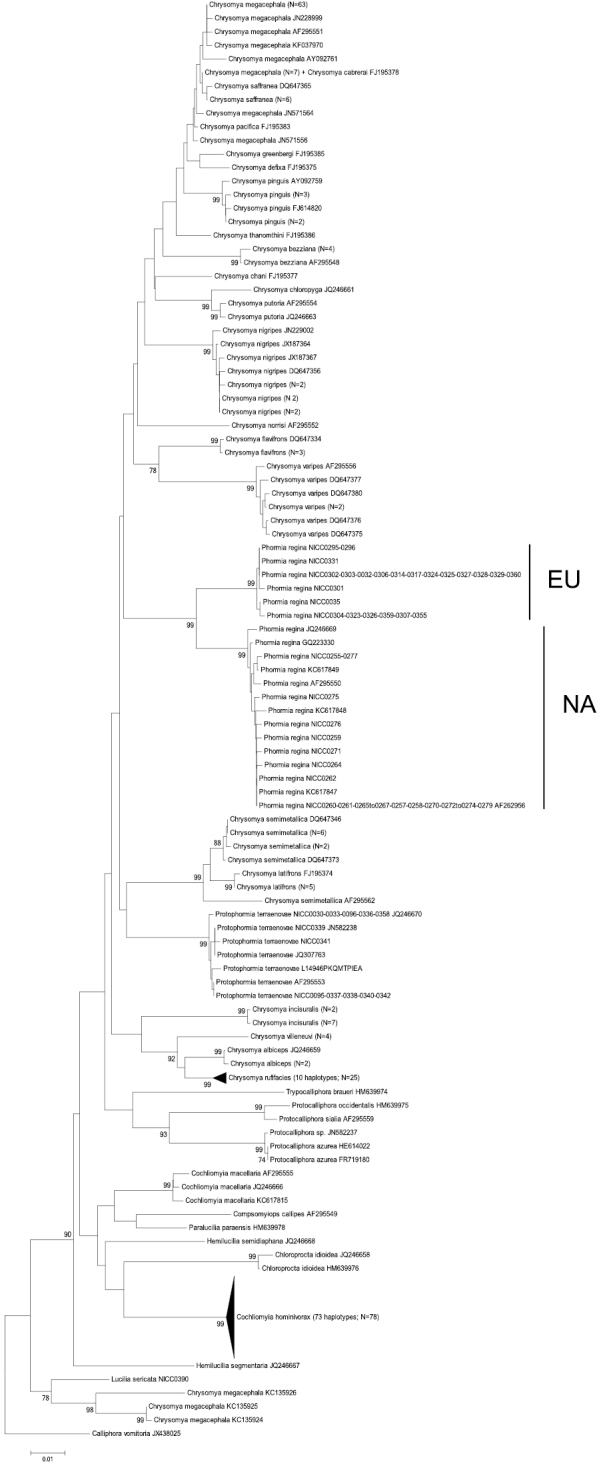

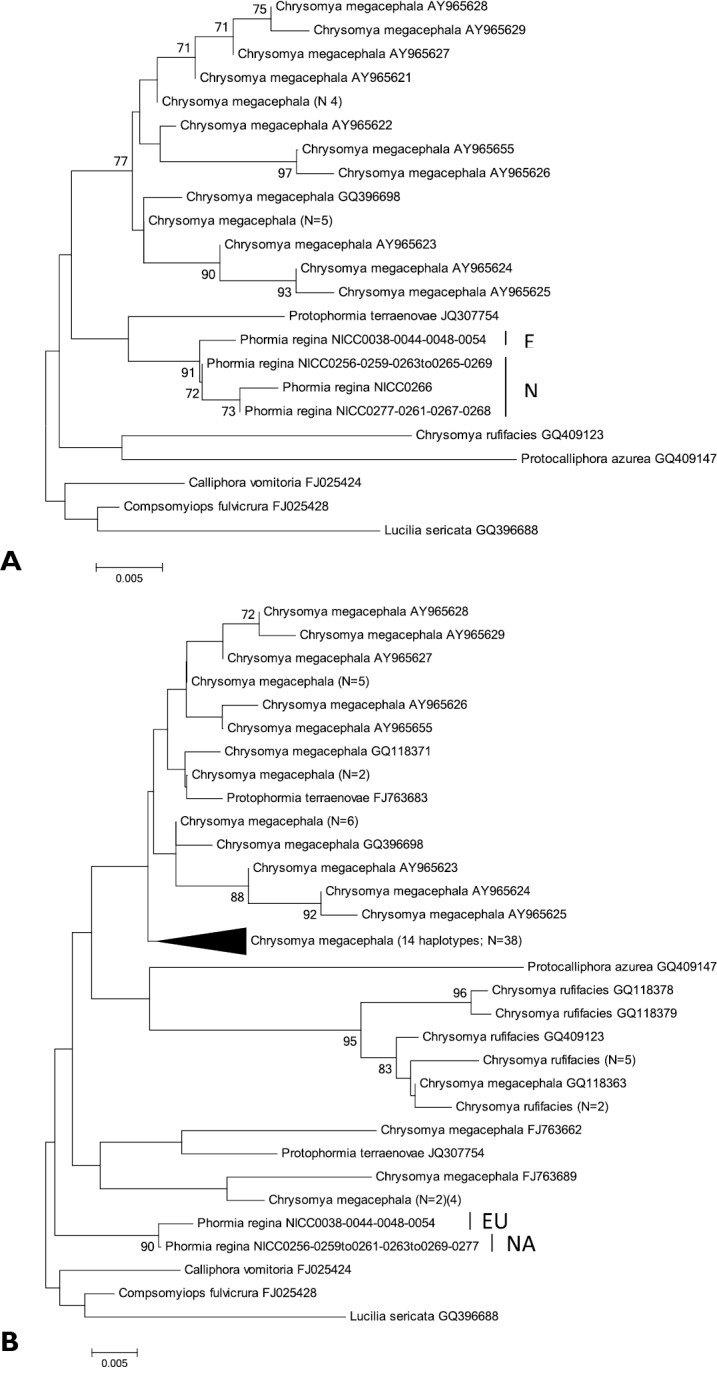

Basic information of the different datasets can be found in Table 3. There was only high bootstrap support for the monophyly of Chrysomyinae, Phormiini or Chrysomyini with 28S and a sister group relationship of Phormia regina and Protophormia terraenovae with ITS2. Yet, for all fragments, except for 28S, there was high bootstrap support for the monophyly of Phormia regina (Figures 2–4 and Appendix 1 – Supplementary figures 1–3).

Figure 2.

Neighbour-Joining tree (p-distances) of a 655 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at the nodes. N gives the number of specimens of that haplotype. EU = Phormia regina haplotypes from W Europe; NA = Phormia regina haplotypes from N America.

Figure 3.

Neighbour-Joining tree (p-distances) of a 472 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COII) gene. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at the nodes. N gives the number of specimens of that haplotype. EU = Phormia regina haplotypes from W Europe; NA = Phormia regina haplotypes from N America.

Figure 4.

Neighbour-Joining tree (p-distances) of a 512 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cyt b) gene. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at the nodes. N gives the number of specimens of that haplotype. EU = Phormia regina haplotypes from W Europe; NA = Phormia regina haplotypes from N America.

COI: The COI NJ-tree showed two supported clades within Phormia regina (Figure 2). One clade (EU = Europe) comprised six haplotypes from Europe (23 specimens sequenced), while the other clade (NA = North America) comprised 14 haplotypes from N America (27 specimens sequenced). The seven NA haplotypes available in GenBank clustered within the NA clade. The mean p-distance between the EU and NA Phormia regina haplotypes was 0.04 ± 0.007 (Table 3). Sequence divergence in Phormia regina within each continent was approximately a ten-fold lower, viz. EU: 0.003 ± 0.001 – NA: 0.004 ± 0.001.

The mean p-distances between Chrysomyinae species pairs were: between three Protocalliphora spp.: 0.05 ± 0.006, 23 Chrysomya taxa: 0.06 ± 0.005 (the three Chrysomya megacephala specimens with GenBank accession numbers KC135924, KC135925 and KC135926 were treated as a different taxon from the other Chrysomya megacephala specimens because of a strong sequences divergence, viz. mean p-distance = 0.089 ± 0.01; see Figure 2), Cochliomyia macellaria – Cochliomyia hominivorax: 0.068 ± 0.009, and Hemilucilia semidiaphana – Hemilucilia segmentaria: 0.078 ± 0.001. The mean intra- and interspecific p-distances between all Chrysomyinae species (excluding Phormia regina) were 0.005 ± 0.009 and 0.066 ± 0.005, respectively (Table 3).

COII: The two EU and seven NA haplotypes of Phormia regina (from 30 specimens) formed two strongly supported clades (Figure 3) separated by mean p-distance of 0.037 ± 0.008 (Table 3). The three COII sequences from GenBank (from NA specimens) had the same haplotype as our NA specimens. Sequence divergence in Phormia regina within each continent was approximately a ten-fold lower, viz. EU: 0.002 ± 0.002 – NA: 0.004 ± 0.002 (Table 3). The mean p-distance between the 14 Chrysomya taxa was 0.059 ± 0.007. We considered Chrysomya megacephala_FJ153270 and Chrysomya rufifacies_FJ839395 as misidentifications, and Chrysomya rufifacies_AY842670_AY842671 to be different from the other Chrysomya rufifacies individuals given the high sequence divergence (viz. mean p-distance = 0.10 ± 0.013). The mean p-distance between Cochliomyia macellaria and Cochliomyia hominivorax was 0.048 ± 0.009. The mean intra- and interspecific p-distances among all Chrysomyinae species (excluding Phormia regina) were 0.014 ± 0.014 and 0.046 ± 0.005, respectively (Table 3).

Cyt b: The three EU and seven NA haplotypes of Phormia regina (from 17 specimens) formed two strongly supported clades (Figure 4) with a mean p-distance of 0.053 ± 0.009 between these two clades (Table 3). There were no cyt b sequences of Phormia in GenBank. Sequence divergence in Phormia regina within each continent was approximately a ten-fold lower, viz. EU: 0.002 ± 0.007 – NA: 0.005 ± 0.002 (Table 3). The mean p-distance between the three Chrysomya species was 0.046 ± 0.005. The mean intra- and interspecific p-distances among all Chrysomyinae species (excluding Phormia regina) were 0.003 ± 0.002 and 0.079 ± 0.007, respectively (Table 3).

16S: For the 350 bp dataset, the three NA 16S haplotypes (from 15 specimens) (mean within NA p-distance = 0.004 ± 0.003; Table 3) formed a well-supported clade, and formed a monophyletic group with the single EU haplotype (Supplementary figure 1A). The mean p-distance between the NA and EU haplotypes was 0.006 ± 0.003. The mean p-distance between Chrysomya megacephala and Chrysomya rufifacies was 0.040 ± 0.009. The mean intra- and interspecific p-distances among all Chrysomyinae species (excluding Phormia regina) were 0.014 and 0.023 ± 0.004.

For the 251 bp dataset, all eleven NA specimens had the same haplotype with a p-distance of 0.004 to the EU haplotype (four specimens) (Supplementary figure 1B). The mean p-distance between Chrysomya megacephala and Chrysomya rufifacies was 0.059 ± 0.012. The mean intra- and interspecific p-distances among all Chrysomyinae species (excluding Phormia regina) were 0.028 ± 0.009 and 0.038 ± 0.006, respectively (Table 3).

ITS2: Excluding indels, all Phormia regina specimens (36 specimens) had the same haplotype (Supplementary figure 2), except for Phormia regina NICC0302 that had a C instead of a T at position 219 of the alignment (p-distance = 0.003). Phormia regina NICC0640 had a deletion at position 201, and Phormia regina NICC0048 had an insertion of a G at position 270 of the alignment. Both specimens were from the same locality (Liège – Belgium) in W Europe. The p-distance between Cochliomyia hominivorax and Cochliomyia macellaria was 0.008 ± 0.001, that between Hemilucilia segmentaria and Hemilucilia semidiaphana was 0.106 ± 0.018, and the mean p-distance among 16 Chrysomya species was 0.085 ± 0.010. The mean intra- and interspecific p-distances among all Chrysomyinae species (excluding Phormia regina) were 0.008 ± 0.005 and 0.085 ± 0.011, respectively (Table 3).

28S: All 37 Phormia regina specimens had the same haplotype, except for Phormia regina JQ246614 from N America that had an AG insertion at positions 460-461 of the alignment (Supplementary figure 3). One haplotype of Protophormia terraenovae (three specimens with GenBank accession numbers AJ300142, JQ307780 and JQ246615) only differed by two indels from haplotype JQ246614 of Phormia regina (at positions 408 and 460-461) (the other Protophormia terraenovae haplotype differed at more positions). The mean p-distance between Cochliomyia macellaria and Cochliomyia hominivorax was 0.005, that between Protocalliphora azurea and Protocalliphora sialia was zero [an indel at position 439 (A) in Protocalliphora azurea) of the alignment], and that between Hemilucilia semidiaphana and Hemilucilia segmentaria was 0.013. The mean p-distance among the six Chrysomya species was 0.006 ± 0.002. The mean intra- and interspecific p-distances among all Chrysomyinae species (excluding Phormia regina) were 0.003 ± 0.004 and 0.007 ± 0.002, respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

Desmyter and Gosselin (2009) and Boehme et al. (2012) found a mean sequence divergence of approximately 4% within a 304 bp and the barcoding COI region between N American and W European Phormia regina, respectively. We confirmed this COI divergence with newly sequenced material. Such a strong divergence at COI is common among insect species (e.g. Park et al. 2011a, b, Webb et al. 2012, Ng’endo et al. 2013). Moreover, we here show a similar degree of divergence at two other mtDNA genes, viz. COII (3.7%) and cyt b (5.3%). The ‘within-continent’ divergence in Phormia regina was very low (0.2-0.5% for the three genes) and comparable to the intraspecific differentiation of other Chrysomyinae (0.5% for COI, 1.4% for COII, 0.3% for cyt b). Hence, the high between-continent mtDNA differentiation, and low within-continent mtDNA divergence may hint at a taxonomic difference between the N American and W European populations. In order to evaluate this suggestion, we included all publicly available GenBank sequences from species of the subfamily Chrysomyinae for the four mtDNA and two nDNA gene fragments that we sequenced. The combined study of mtDNA and nDNA has proven valuable to disentangle the taxonomy of other calliphorid species (e.g. Nelson et al. 2007, Sonet et al. 2012).

On the one hand, our results show that the mean p-distance of other intrageneric interspecific comparisons (COI: 5–6.8%, COII: 4.8-5.9%, cyt b: 4.6%, 16S (251 bp): 5.9%), or among other Chrysomyinae species in general (COI: 6.6%, COII: 4.6%, cyt b: 7.9%, 16S (251 bp): 3.8%), are higher than the mean p-distances between N American and W European Phormia regina at the four mtDNA fragments (COI: 4%, COII: 3.7%, cyt b: 5.3%, 16S: 0.6%). For cyt b the NA-EU differentiation in Phormia regina is higher than that observed within other Chrysomyinae species (0.3%) yet still below the minimum interspecific p-distance (7.3%). On the other hand, for COI and COII, the NA-EU differentiation in Phormia regina is higher than the intraspecific differentiation in other Chrysomyinae species and well within the range of interspecific p-distances within Chrysomyinae. Yet, the low interspecific p-distance between some Chrysomyinae species may be due to misidentifications or may be the result of a natural process (e.g. hybridization, incomplete lineage sorting). Likewise, the high intraspecific variation within some species may be indicative of cryptic diversity (see further).

North American and W European Phormia regina were not differentiated at both nDNA fragments, and at the mtDNA 16S (< 1%), whereas interspecific p-distances in Chrysomyinae in general are substantial for ITS2 (8.5%) and 16S (3.8%). Moreover, the NA-EU differentiation in Phormia regina at these genes was even lower than the minimum intraspecific differentiation within other Chrysomyinae. This suggests that the variation at these genes in Phormia regina is intraspecific variation. Finally, we could neither detect color differences in 11 external characters, nor in the general shape of the male copulatory organs between N American and W European specimens. Evidently, a statistical analysis of more specimens (from a wider range of the species’ distribution) is necessary to reliably assess within and among population variation at these (and eventually other) morphological characters. For the time being, we consider the high differentiation at COI, COII and cyt b, but the low (16S, nDNA) or lack of (morphological) differentiation, as indicative of substantial intraspecific mtDNA sequence divergence, rather than as a species-level differentiation.

Our findings may have important implications for the use of Phormia regina in forensic and other scientific fields. Indeed, it has been suggested that the high variation in developmental times and growth curves of Phormia regina (e.g. Byrd and Allen 2001 and references therein) is partly due to differences in the population genetic structure (Picard and Wells 2009) and that therefore ecological data obtained from one population should not be generalized or extrapolated to other populations (Byrne et al. 1995). Interestingly, Marchenko (2001) reports a mean accumulated degree-days (from egg to adult) of 148 °C (lower development temperature: 11.4 °C) for Russian/Lithuanian Phormia regina, whereas a mean accumulated degree-days of 162 °C (lower development temperature: 11.16 °C) was found for N American Phormia regina (Yves Braet, unpublished preliminary results). Hence, the strong mtDNA divergence between N American and W European Phormia regina requires a sound comparison of the ecology of populations from both continents, especially since Phormia regina is a key species in the study of the physiology and neurology of insect feeding (e.g. Haselton et al. 2009, Larson and Stoffolano 2011, Ishida et al. 2012). Moreover, if locally diverged populations differ in their developmental biology, then this may affect the estimate of PMImin.

Intraspecific mtDNA divergence in other Chrysomyinae species is sometimes also high, viz. 4.3% for COI in Chrysomya megacephala, and 2.2%, 2.6% and 3.7% for COII in Chrysomya megacephala, Chrysomya semimetallica and Chrysomya rufifacies, respectively. Whereas these high intraspecific divergences may be due to hybridization/introgression or incomplete lineage sorting, they may also point to misidentifications. Obviously these issues are problematic if DNA barcoding of animals is only based on COI, as advocated by Hebert et al. (2003a, b). For instance, three Chrysomya megacephala specimens (KC135924, KC139925, KC135926) have a remarkably high p-distance of 8% with the other Chrysomya megacephala haplotypes and it would be advisable to re-identify these specimens. Also Chrysomya semimetallica shows much more intraspecific sequence variation (mean p-distance = 0.011 ± 0.003) as compared to other Chrysomyinae species but at the same time the species has a low mean interspecific p-distance with Chrysomya albiceps (p-distance = 0.017 ± 0.004).

Although there is no doubt that COI is a useful tool for the identification of forensically important Chrysomyinae species (Wells and Sperling 2001, Nelson et al. 2007, Wells and Williams 2007, Desmyter and Gosselin 2009, Boehme et al. 2012) not all species can be identified with COI. For instance, there is very low mean interspecific p-distance of 0.006 ± 0.002 between Chrysomya megacephala (excluding the three aforementioned haplotypes), Chrysomya cabrerai, Chrysomya saffranea and Chrysomya pacifica (the first two even share a haplotype) (see also Harvey et al. 2008). Therefore, other genes (or gene fragments) might help to overcome the shortcomings of the sole use of COI as molecular identification tool. We here showed that also COII may be a good DNA barcode marker in the Chrysomyinae. Indeed, the mean interspecific p-distance at COII is 4.6%, whereas the mean intraspecific distance is much lower (1.4%). Yet, the amount of Chrysomyinae COII data that is currently available in public libraries such as GenBank (194 sequences representing 108 haplotypes from 20 species), is rather limited compared to the amount of COI data (339 sequences representing 180 haplotypes from 36 species) (Table 1). Moreover, the problems inherent to misidentifications and introgression also apply to COII (or any other DNA marker). For instance, Chrysomya megacephala FJ153270 shares a haplotype within the Chrysomya rufifacies clade, and Chrysomya rufifacies FJ839395 shares a haplotype within the Chrysomya megacephala clade. Also other species share haplotypes such as Chrysomya semimetallica and Chrysomya latifrons. The other two mtDNA fragments (cyt b and 16S) cannot yet be evaluated as DNA barcode markers because of insufficient sequence data (cyt b: 32 sequences representing 20 haplotypes of five species; 16S: 39 sequences representing nine haplotypes of six species) (Table 1), but both have been shown to discriminate sufficiently between other dipteran species of forensic interest (Vincent et al. 2000, Li et al. 2010).

So far, the forensically important species within the Chrysomyinae belong to the genera Chrysomya, Cochliomyia, Paralucilia, Protophormia and Phormia. A number of COI reference datasets of these species are available (e.g. Wallman and Donnellan 2001, Wells and Sperling 2001, Nelson et al. 2007, Wells and Williams 2007, Harvey et al. 2008, Desmyter and Gosselin 2009, Boehme et al. 2012) and they seem to work well to identify most forensically important species. Yet, it is important to also include species without a clear forensic interest in (local) reference databases because this will improve the assessment of species boundaries which, in turn, may help to reach a stable taxonomy.

In conclusion, we observed substantial differentiation between N American and W European Phormia regina at the mtDNA genes COI, COII and cyt b, but not at the 16S rDNA and the nDNA genes ITS2 and 28S. Moreover, we neither detected any morphological differentiation between specimens from both continents. We therefore consider the strong mtDNA divergence between specimens from both continents as intraspecific variation. This differentiation has to be taken into account when using Phormia regina in forensic casework or physiological studies. Finally, the use of COII as a DNA barcode marker in the Chrysomyinae seems to perform as good as the standard COI barcode region.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Françoise Hubrecht for her support, Knut Rognes for his help with the literature, and Sofie Vanpoucke (NICC) for her help in making the pictures of the genitalia. We thank Jens Amendt, Richard Zehner and Benoît Vincent for providing part of the W European Phormia material, and Neal Haskell, Jefferey Tomberlin and Jeffrey Wells for collecting part of the N American Phormia specimens. The comments of one referee improved the manuscript considerably. This work was done in the context of FWO research network W0.009.11N “Belgian Network for DNA Barcoding”. JEMU is funded by the Belgian Science Policy Office (Belspo).

Appendix 1

Supplementary figure 1.

Neighbour-Joining tree (p-distances) of a 350 bp (A) and of a 251 bp (B) fragment of the mitochondrial 16S gene. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at the nodes. N gives the number of specimens of that haplotype. EU = Phormia regina haplotypes from W Europe; NA = Phormia regina haplotypes from N America.

Supplementary figure 2.

Neighbour-Joining tree (p-distances) of a 404 bp (229 bp without indels) fragment of the nuclear internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2). Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at the nodes. N gives the number of specimens of that haplotype. EU = Phormia regina haplotypes from W Europe; NA = Phormia regina haplotypes from N America.

Supplementary figure 3.

Neighbour-Joining tree (p-distances) of a 633 bp fragment of the nuclear 28S gene. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at the nodes. N gives the number of specimens of that haplotype. EU = Phormia regina haplotypes from W Europe; NA = Phormia regina haplotypes from N America.

Supplementary table 1.

Sampling localities, voucher numbers and GenBank numbers of the Phormia regina and Protophormia terraenovae that were sequenced in this study.

| Species | continent/country | country/state | city/county | latitude/longitude | voucher no. | GenBank accession no. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI | COII | 16S | cyt b | ITS2 | 28S | ||||||

| Phormia regina | Europe | Belgium | Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0323 | KJ908102 | |||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0324 | KF908103 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0325 | KF908104 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0326 | KF908105 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0327 | KF908106 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0328 | KF908107 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0329 | KF908108 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0331 | KF908109 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0332 | KF908199 | KF908234 | |||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0334 | KF908200 | KF908235 | |||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36"N, 5°54'36"E | NICC 0336 | KF908201 | ||||||||

| Auderghem | 50°49'05"N, 4°24'41"E | NICC 0032 | KF908069 | ||||||||

| Custine | 49°41'41"N, 3°49'28"E | NICC 0314 | KF908100 | ||||||||

| Genk | 50°57'13"N, 5°29'56"E | NICC 0038 | KF908054 | ||||||||

| Genk | 50°57'13"N, 5°29'56"E | NICC 0355 | KF908110 | ||||||||

| Hastière | 50°13'14"N, 4°49'39"E | NICC 0027 | KF908153 | KF908171 | |||||||

| Laeken | 50°53'10"N, 4°22'36"E | NICC 0044 | KF908126 | KF908055 | KF908154 | KF908172 | |||||

| Liège | 50°37'49"N, 5°33'17"E | NICC 0048 | KF908127 | KF908056 | KF908155 | KF908173 | KF908205 | ||||

| Liège | 50°37'49"N, 5°33'17"E | NICC 0638 | KF908202 | ||||||||

| Liège | 50°37'49"N, 5°33'17"E | NICC 0640 | KF908169 | KF908203 | KF908236 | ||||||

| Liège | 50°37'49"N, 5°33'17"E | NICC 0641 | KF908237 | ||||||||

| Messancy | 49°35'31"N, 5°48'54"E | NICC 0317 | KF908101 | ||||||||

| Schaerbeek | 50°51'34"N, 4°22'25"E | NICC 0035 | KF908070 | ||||||||

| Schoonaarde | 51°00'17"N, 4°00'05"E | NICC 0359 | KF908111 | ||||||||

| Schoonaarde | 51°00'17"N, 4°00'05"E | NICC 0360 | KF908112 | ||||||||

| Steendorp | 51°07'25"N, 4°14'49"E | NICC 0054 | KF908128 | KF908057 | KF908206 | ||||||

| Toernich | 49°39'01"N, 5°45'07"E | NICC 0024 | KF908170 | KF908204 | |||||||

| France | Sarreguemines | 49°06'50"N, 7°04'18"E | NICC 0295 | KF908092 | KF908227 | ||||||

| Sarreguemines | 49°06'50"N, 7°04'18"E | NICC 0296 | KF908093 | KF908166 | KF908195 | KF908228 | |||||

| Germany | Frankfurt | 50°06'41"N, 8°40'49"E | NICC 0301 | KF908094 | KF908196 | KF908229 | |||||

| Frankfurt | 50°06'41"N, 8°40'49"E | NICC 0302 | KF908095 | KF908197 | KF908230 | ||||||

| Frankfurt | 50°06'41"N, 8°40'49"E | NICC 0303 | KF908096 | KF908167 | |||||||

| Frankfurt | 50°06'41"N, 8°40'49"E | NICC 0304 | KF908097 | ||||||||

| Frankfurt | 50°06'41"N, 8°40'49"E | NICC 0305 | KF908168 | KF908231 | |||||||

| Frankfurt | 50°06'41"N, 8°40'49"E | NICC 0306 | KF908098 | KF908198 | KF908232 | ||||||

| Frankfurt | 50°06'41"N, 8°40'49"E | NICC 0307 | KF908099 | KF908233 | |||||||

| USA | Indiana | Rensselaer Co. | 40°56'12"N, 87°09'03"W | NICC 0275 | KF908088 | KF908150 | KF908222 | ||||

| Rensselaer Co. | 40°56'12"N, 87°09'03"W | NICC 0276 | KF908089 | KF908151 | KF908192 | KF908223 | |||||

| Rensselaer Co. | 40°56'12"N, 87°09'03"W | NICC 0277 | KF908090 | KF908152 | KF908068 | KF908193 | KF908224 | ||||

| Rensselaer Co. | 40°56'12"N, 87°09'03"W | NICC 0278 | KF908194 | KF908225 | |||||||

| Rensselaer Co. | 40°56'12"N, 87°09'03"W | NICC 0279 | KF908091 | KF908226 | |||||||

| Texas | Brazos | 32°39'41"N, 98°07'19"W | NICC 0265 | KF908080 | KF908140 | KF908063 | KF908212 | ||||

| Brazos | 32°39'41"N, 98°07'19"W | NICC 0266 | KF908081 | KF908141 | KF908064 | KF908161 | KF908184 | KF908213 | |||

| Brazos | 32°39'41"N, 98°07'19"W | NICC 0267 | KF908082 | KF908142 | KF908065 | KF908162 | KF908214 | ||||

| Brazos | 32°39'41"N, 98°07'19"W | NICC 0268 | KF908143 | KF908066 | KF908163 | KF908185 | KF908215 | ||||

| Brazos | 32°39'41"N, 98°07'19"W | NICC 0269 | KF908144 | KF908067 | KF908164 | KF908186 | KF908216 | ||||

| Virginia | Pr. Williams Co. | 38°31'20"N, 77°17'22"W | NICC 0260 | KF908075 | KF908135 | KF908158 | KF908179 | ||||

| Pr. Williams Co. | 38°31'20"N, 77°17'22"W | NICC 0261 | KF908076 | KF908136 | KF908060 | KF908159 | KF908180 | KF908209 | |||

| Pr. Williams Co. | 38°31'20"N, 77°17'22"W | NICC 0262 | KF908077 | KF908137 | KF908160 | KF908181 | KF908210 | ||||

| Pr. Williams Co. | 38°31'20"N, 77°17'22"W | NICC 0263 | KF908078 | KF908138 | KF908061 | KF908182 | |||||

| Pr. Williams Co. | 38°31'20"N, 77°17'22"W | NICC 0264 | KF908079 | KF908139 | KF908062 | KF908183 | KF908211 | ||||

| Washington | Snohomish Co. | 47°54'46"N, 122°05'53"W | NICC 0270 | KF908083 | KF908145 | KF908187 | KF908217 | ||||

| Snohomish Co. | 47°54'46"N, 122°05'53"W | NICC 0271 | KF908084 | KF908146 | KF908165 | KF908188 | KF908218 | ||||

| Snohomish Co. | 47°54'46"N, 122°05'53"W | NICC 0272 | KF908085 | KF908147 | KF908189 | KF908219 | |||||

| Snohomish Co. | 47°54'46"N, 122°05'53"W | NICC 0273 | KF908086 | KF908148 | KF908190 | KF908220 | |||||

| Snohomish Co. | 47°54'46"N, 122°05'53"W | NICC 0274 | KF908087 | KF908149 | KF908191 | KF908212 | |||||

| Wyoming | Park Co. | 44°31'52"N, 108°57'40"W | NICC 0255 | KF908071 | KF908130 | KF908174 | |||||

| Park Co. | 44°31'52"N, 108°57'40"W | NICC 0256 | KF908131 | KF908058 | KF908175 | ||||||

| Park Co. | 44°31'52"N, 108°57'40"W | NICC 0257 | KF908072 | KF908132 | KF908156 | KF908176 | |||||

| Park Co. | 44°31'52"N, 108°57'40"W | NICC 0258 | KF908073 | KF908133 | KF908177 | KF908207 | |||||

| Park Co. | 44°31'52"N, 108°57'40"W | NICC 0259 | KF908074 | KF908134 | KF908059 | KF908157 | KF908178 | KF908208 | |||

| Protophormia terraenovae | Europe | Belgium | Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0030 | KF908113 | |||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0095 | KF908115 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0096 | KF908116 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0336 | KF908117 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0337 | KF908118 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0338 | KF908119 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0339 | KF908120 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0340 | KF908121 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0341 | KF908122 | ||||||||

| Andrimont | 50°36'36''N, 5°54'36''E | NICC 0342 | KF908123 | ||||||||

| Auderghem | 50°49'05''N, 4°24'41''E | NICC 0033 | KF908114 | ||||||||

| Auderghem | 50°49'05''N, 4°24'41''E | NICC 0358 | KF908124 | ||||||||

Appendix 2

Text file with the alignments for all the gene fragments studied. (doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.6202.app2) File format: Text file (txt).

Explanation note: Text file with the alignments (fasta format) for all the gene fragments studied (COI, COII, cyt b, 16S (251 bp), 16S (350 bp), ITS2 and 28S, respectively).

References

- Amendt J, Krettek R, Zehner R. (2004) Forensic entomology. Naturwissenschaften 91: 51-65. doi: 10.1007/s00114-003-0493-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendt J, Campobasso CP, Gaudry E, Reiter C, LeBlanc HN, Hall MJR. (2007) Best practice in forensic entomology: standards and guidelines. International Journal of Legal Medicine 121: 90-104. doi: 10.1007/s00414-006-0086-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GS. (2000) Minimum and maximum development rate of some forensically important Calliphoridae (Diptera). Journal of Forensic Science 45: 824-832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehme P, Amendt J, Zehner R. (2012) The use of COI barcodes for molecular identification of forensically important fly species in Germany. Parasitology Research 110: 2325-2335. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2767-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundage A, Bros S, Honda JY. (2011) Seasonal and habitat abundance and distribution of some forensically important blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in Central California. Forensic Science International 212: 115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd JH, Allen JC. (2001) The development of the black blow fly, Phormia regina (Meigen). Forensic Science International 120: 79-88. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00431-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne AL, Camann MA, Cyr TL, Catts EP, Espelie KE. (1995) Forensic implications of biochemical differences among geographic populations of the black blow fly, Phormia regina. Journal of Forensic Sciences 40: 372-377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts EP. (1992) Problems in estimating the postmortem interval in death investigations. Journal of Agricultural Entomology 9: 245-255. [Google Scholar]

- Charabidze D. (2012) Necrophagous insects and forensic entomology. Annales de la Société Entomologique de France 48: 239-252. doi: 10.1080/00379271.2012.10697773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey MD. (1966) Studies on the association of flies (Diptera) with dung in southeastern Washington. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 59: 207-218. [Google Scholar]

- DeBry RW, Timm A, Wong ES, Stamper T, Cookman C, Dahlem GA. (2013) DNA-based identification of forensically important Lucilia (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in the continental United States. Journal of Forensic Sciences 58: 73-78. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02176.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmyter S, Gosselin M. (2009) COI sequence variability between Chrysomyinae of forensic interest. Forensic Science International 3: 89-95. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783-791. doi: 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi F, Lupi O. (2012) Myasis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 25: 79-105. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00010-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg B. (1991) Flies as forensic indicators. Journal of Medical Entomology 28: 565-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths GCD. (1982) On the systematic position of Mystacinobia (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Memoirs of the Entomological Society, Washington 10: 70-77. [Google Scholar]

- Hall DG. (1948) The blowflies of North America. Thomas Say Foundation, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey ML, Gaudieri S, Villet MH, Dadour IR. (2008) A global study of forensically significant calliphorids: implications for identification. Forensic Science International 177: 66-67. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselton AT, Downer KE, Zylstra J, Stoffolano JG. (2009) Serotonin inhibits protein feeding in the blow fly, Phormia regina (Meigen). Journal of Insect Behavior 22: 452-463. doi: 10.1007/s10905-009-9184-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, DeWaard JR. (2003a) Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit I divergences among closely related species. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B (Supplement) 270: S96–S99. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, DeWaard JR. (2003b) Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 270: 313-321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Nagae T, Azuma M. (2012) A water-specific aquaporin is expressed in the olfactory organs of the blowfly, Phormia regina. Journal of Chemical Ecology 38: 1057-1061. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0157-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordaens K, Sonet G, Desmyter S. (in press) IX. Aperçu des méthodes moléculaires d’identification d’insectes d’intérêt forensique. In: Charabidze D, Gosselin M. (Eds) Insectes, Cadavre & Scène de Crime – Principes et Applications de l’Entomologie Médico-légale. De Boeck, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal AS. (1958) Comparative study of thirteen species of sarcosaprophagous Calliphoridae and Sarcophagidae (Diptera).I. Bionomics. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 51: 261-270. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772-780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipling EF, Rainwater HT. (1937) Species and incidence of dipterous larvae concerned in wound myiasis. Journal of Parasitology 23: 451-455. doi: 10.2307/3272391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutty SN, Bernasconi MV, Sifner F, Meier R. (2007) Sensitivity analysis, molecular systematics and natural history evolution of Scathophagidae (Diptera: Cyclorrhapha: Calyptratae). Cladistics 23: 64-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2006.00131.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutty SN, Pape T, Wiegmann BM, Meier R. (2010) Molecular phylogeny of the Calyptratae (Diptera: Cyclorrhapha) with an emphasis on the superfamily Oestroidea and the position of Mystacinobiidae and McAlpine’s fly. Systematic Entomology 35: 614-635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2010.00536.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson K, Stoffolano JG. (2011) Effect of high and low concentrations of sugar solutions fed to adult male, Phormia regina (Diptera: Calliphoridae), on ‘bubbling’ behavior. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 104: 1399-1403. doi: 10.1603/AN11029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Cai JF, Guo YD, Wu KL, Wang JF, Liu QL, Wang XH, Chang YF, Yang L, Lan LM, Zhong M, Wang X, Song C, Liu Y, Li JB, Dai ZH. (2010) The availability of 16S rRNA for the identification of forensically important flies (Diptera: Muscidae) in China. Tropical Biomedicine 27: 155-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko MI. (2001) Medicolegal relevance of cadaver entomofauna for the determination of the time of death. Forensic Science International 120: 89-109. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00416-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabity PD, Higley LG, Heng-Moss TM. (2007) Light-induced variability in development of forensically important blow fly Phormia regina (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Journal of Medical Entomology 44: 351-358. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[351:LVIDOF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LA, Wallman JF, Dowton M. (2007) Using COI barcodes to identify forensically and medically important blowflies. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 21: 44-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng’endo RN, Osiemo ZB, Brandl R. (2013) DNA barcodes for species identification in the hyperdiverse ant genus Pheidole (Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Journal of Insect Science 13: 27. doi: 10.1673/031.013.2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Vázquez C, Tomberlin J, Cantú-Sifuentes M, García-Martínez O. (2013) Laboratory development and field validation of Phormia regina (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Journal of Medical Entomology 50: 252-260. doi: 10.1603/ME12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DS, Suh SJ, Hebert PDN, Oh HW, Hong KJ. (2011a) DNA barcodes for two scale insect families, mealybugs (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) and armored scales (Hemiptera: Diaspididae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 101: 429-434. doi: 10.1017/S0007485310000714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DS, Foottit R, Maw E, Hebert PDN. (2011b) Barcoding bugs: DNA-based identification of the True Bugs (Insecta: Hemiptera: Heteroptera). PLoS ONE 6: e18749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard CJ, Wells JD. (2009) Survey of the genetic diversity of Phormia regina (Diptera: Calliphoridae) using amplified fragment length polymorphisms. Journal of Medical Entomology 46: 664-670. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ready PD, Testa JM, Wardhana AH, Al-Izzi M, Khalaj M, Hall MJR. (2009) Phylogeography and recent emergence of the Old World screwworm fly, Chrysomya bezziana, based on mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 23: 43-50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rognes K. (1997) The Calliphoridae (blowflies) (Diptera: Oestroidea) are not a monophyletic group. Cladistics 13: 27-66. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1997.tb00240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 4: 406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B, Wells JD. (2011a) Chrysomyinae (Diptera: Calliphoridae) is monophyletic: a molecular systematic analysis. Systematic Entomology 36: 415-420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2011.00568.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B, Wells JD. (2011b) Molecular systematics of the Calliphoridae (Diptera: Oestroidea): Evidence from one mitochondrial and three nuclear genes. Journal of Medical Entomology 50: 15-23. doi: 10.1603/ME11288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonet G, Jordaens K, Braet Y, Desmyter S. (2012) Why is the molecular identification of the forensically important blowfly species Lucilia caesar and L. illustris (family Calliphoridae) so problematic? Forensic Science International 223: 153-159. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, Wang X, GeQiu Liang G. (2008) Species identification of some common necrophagous flies in Guangdong province, southern China based on the rDNA internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2). Forensic Science International 175: 17-22. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.04.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling FA, Anderson GS, Hickey DA. (1994) A DNA-based approach to the identification of insect species used for postmortem interval estimation. Journal of Forensic Sciences 39: 418–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JR, Wall R. (2001) Genetic relationships between blowflies (Calliphoridae) of forensic importance. Forensic Science International 120: 116-123. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00417-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. (2011) MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution 28: 2731-2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent S, Vian JM, Carlotti MP. (2000) Partial sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome b oxidase subunit I gene: A tool for the identification of European species of blow flies for postmortem interval estimation. Journal of Forensic Sciences 45: 820-823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallman JF, Donnellan SC. (2001) The utility of mitochondrial DNA sequences for the identification of forensically important blowflies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in southeastern Australia. Forensic Science International 120: 60-67. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00426-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JM, Jacobus LM, Funk DH, Zhou X, Kondratieff B, Geraci CJ, DeWalt RE, Baird DJ, Richard B, Phillips I, Hebert PDN. (2012) A DNA barcode library for North American Ephemeroptera: progress and prospects. PLoS ONE 7: e38063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JD, Sperling FAH. (2001) DNA-based identification of forensically important Chrysomyinae (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Forensic Science International 120: 110-115. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00414-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JD, Stevens JR. (2008) Application of DNA-based methods in forensic entomology. Annual Review in Entomology 53: 103-120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JD, Williams DW. (2007) Validation of a DNA-based method for identifying Chrysomyinae (Diptera: Calliphoridae) used in a death investigation. International Journal of Legal Medicine 121: 1-8. doi: 10.1007/s00414-005-0056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. (2013) DAMBE5: A comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 1720-1728. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Text file with the alignments for all the gene fragments studied. (doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.6202.app2) File format: Text file (txt).