Significance

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is an important causative agent of B-cell lymphomas and Hodgkin disease in immune-deficient people, including HIV-infected people. The experiments described here were undertaken to determine the mechanisms through which the EBV-encoded nuclear protein EBNA3C blocks the cell p14ARF and p16INK4A tumor suppressor-mediated inhibition of EBV-infected B-cell growth, thereby unfettering EBV-driven B-cell proliferation. The experiments also identify the molecular basis for diverse EBNA3C enhancer interactions with cell DNA-binding proteins and cell DNA to regulate MYC, pRB, BCL2, and BIM expression. Surprisingly, EBNA3C’s role in enhancer-mediated cell gene transcription up-regulation is primarily mediated by combinatorial effects with cell transcription factors, most notably AICEs, EICEs, and RUNX3.

Keywords: EBV, tumor suppressor, resting B lymphocyte, lymphoma

Abstract

Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C (EBNA3C) repression of CDKN2A p14ARF and p16INK4A is essential for immortal human B-lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) growth. EBNA3C ChIP-sequencing identified >13,000 EBNA3C sites in LCL DNA. Most EBNA3C sites were associated with active transcription; 64% were strong H3K4me1- and H3K27ac-marked enhancers and 16% were active promoters marked by H3K4me3 and H3K9ac. Using ENCODE LCL transcription factor ChIP-sequencing data, EBNA3C sites coincided (±250 bp) with RUNX3 (64%), BATF (55%), ATF2 (51%), IRF4 (41%), MEF2A (35%), PAX5 (34%), SPI1 (29%), BCL11a (28%), SP1 (26%), TCF12 (23%), NF-κB (23%), POU2F2 (23%), and RBPJ (16%). EBNA3C sites separated into five distinct clusters: (i) Sin3A, (ii) EBNA2/RBPJ, (iii) SPI1, and (iv) strong or (v) weak BATF/IRF4. EBNA3C signals were positively affected by RUNX3, BATF/IRF4 (AICE) and SPI1/IRF4 (EICE) cooccupancy. Gene set enrichment analyses correlated EBNA3C/Sin3A promoter sites with transcription down-regulation (P < 1.6 × 10−4). EBNA3C signals were strongest at BATF/IRF4 and SPI1/IRF4 composite sites. EBNA3C bound strongly to the p14ARF promoter through SPI1/IRF4/BATF/RUNX3, establishing RBPJ-, Sin3A-, and REST-mediated repression. EBNA3C immune precipitated with Sin3A and conditional EBNA3C inactivation significantly decreased Sin3A binding at the p14ARF promoter (P < 0.05). These data support a model in which EBNA3C binds strongly to BATF/IRF4/SPI1/RUNX3 sites to enhance transcription and recruits RBPJ/Sin3A- and REST/NRSF-repressive complexes to repress p14ARF and p16INK4A expression.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a highly prevalent γ-herpesvirus that causes B and T lymphomas, Hodgkin disease, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and gastric carcinoma. EBV-associated B lymphomas and Hodgkin disease are more prevalent in T-cell immune-deficient people and are major causes of mortality in HIV-infected people. EBV infection of B lymphocytes, in vitro, results in continuously proliferating lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). LCLs and EBV-infected cells in T-cell immune-deficient people express six EBV-encoded nuclear proteins (EBNA1, EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3B, EBNA3C, and EBNALP), three latent infection-associated membrane proteins (LMP1, LMP2A, and LMP2B), microRNAs, and EBER 1 and 2 RNAs. Genetic analyses indicate that EBNA1, EBNALP, EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3C, and LMP1 are essential for LCL outgrowth (1, 2).

EBNA3A, EBNA3B, and EBNA3C are similar proteins, composed of ∼1,000 aa. Each has a near N-terminal site that binds RBPJ, the cell sequence specific transcription factor (TF) that mediates EBNA2 or Notch binding to DNA. EBNA3A and EBNA3C are both required for LCL growth, whereas EBNA3B is not (3–5). When conditional, hydoxytamoxifen (HT)-dependent, EBNA3C (EBNA3CHT)-expressing LCLs are grown in medium without HT, the cells stop growing (6). HT addition or complementation with wild-type (WT) EBNA3C-expression plasmids, but not with EBNA3A- or EBNA3B-expression plasmids, restores LCL growth, indicating that EBNA3C is specifically required for LCL growth (6). Similar experiments reveal EBNA3C N-terminal amino acids 50–400 to be essential for LCL growth (3, 7, 8). EBNA3C also up-regulates EBV LMP1 and cell CXCR4 and CXCL12 gene expression (9–12), which are required for LCL growth in nude mice (13). EBNA3C and EBNA3A joint repression of p14ARF and p16INK4A expression is essential for LCL growth and knock down of p14ARF and p16INK4A or null p16INK4A mutations allow LCL growth in the absence of EBNA3C, indicating that EBNA3C repression of p14ARF and p16INK4A is an essential EBNA3C function (14, 15). Both EBNA3A and EBNA3C have repressive activities that correlate with cell histone modifications: EBNA3A induces histone modifications at the CXCL10 and CXCL9 chemokine genes (16), whereas EBNA3C induces histone modifications which are important for p14ARF and p16INK4A repression (14, 17). However, the detailed mechanism through which EBNA3C represses p14ARF and p16INK4A expression is unknown.

In contrast to EBNA2, which is tethered to DNA by RBPJ, EBNA3C binding to RBPJ prevents RBPJ binding to DNA in electrophoretic mobility-shift assays (EMSAs) and blocks EBNA2 activation effects (18, 19). EBNA3C affects cell and EBV gene expression through cell TFs. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) found EBNA3C bound to virus and cell promoter sites, including the EBV LMP1, cell BIM, and ITGA4 promoters (20, 21, 22), whereas ChIP-sequencing (ChIP-seq) using an antibody that immune precipitates EBNA3A, EBNA3B, and EBNA3C, found an EBNA3 at around 7,000 sites in a Burkitt lymphoma cell line (23), consistent with the hypothesis that EBNA3C may affect transcription through interactions with other cell TFs (11, 23–27). Recently, EBNA3C residues 130–159 were shown to bind to IRF4 or IRF8, TFs important for lymphopoiesis (24). EBNA3C can also coactivate the EBV LMP1 promoter with EBNA2 through a SPI1 site (10, 11). Overall, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that EBNA3C affects transcription through interactions with cell TFs.

We therefore undertook ChIP-seq studies to identify EBNA3C’s genome-wide interactions with LCL DNA and cell TFs. EBNA3C was at around 13,000 genomic sites and was highly colocalized with cell TFs RUNX3, BATF, IRF4, and SPI1. EBNA3C recruited Sin3A repressive complexes to the p14ARF promoter to mediate p14ARF and p16INK4A repression.

Results

EBNA3C Binding Sites in LCLs.

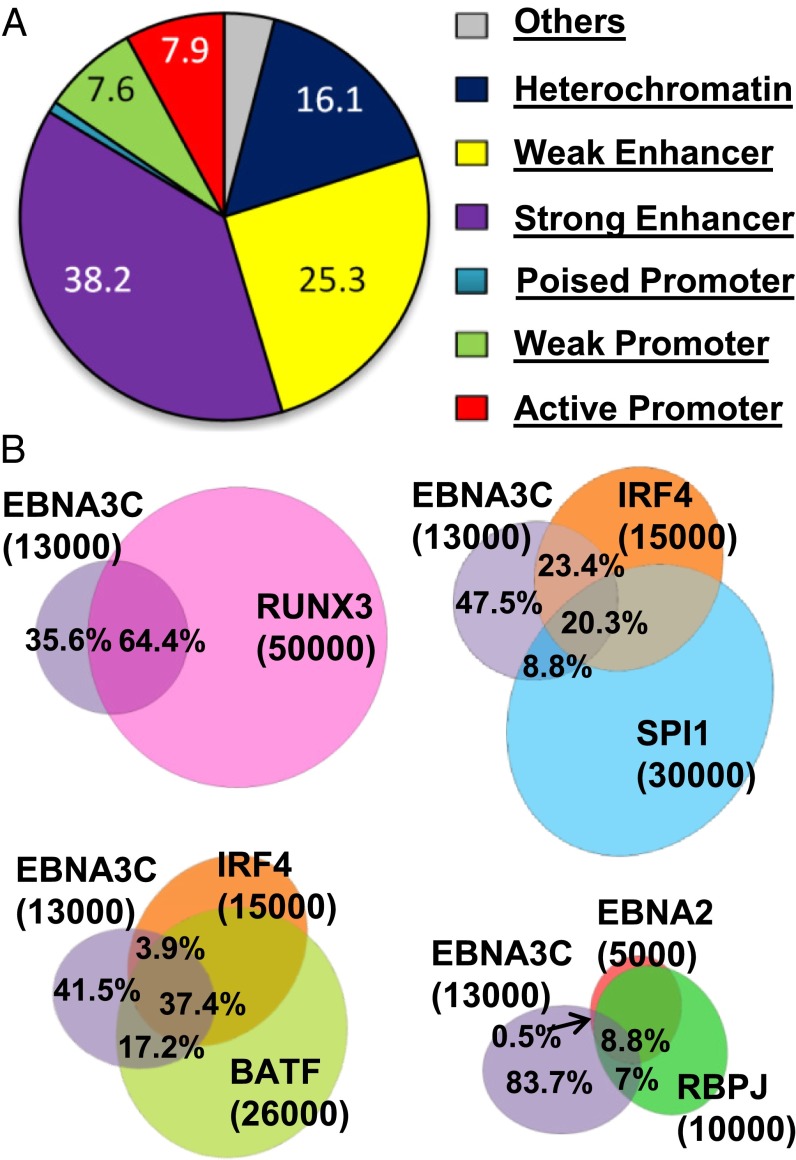

An LCL transformed by a recombinant EBV BACmid in which EBNA3C was C-terminally tagged with HA and Flag epitopes (EBNA3CFH) was used for ChIP-seq analyses. The EBNA3CFH LCLs grew similarly to WT LCLs and expressed similar EBNA3C levels. Two anti-HA ChIP-seq biological replicates identified EBNA3C genome-wide DNA binding sites, using input DNA controls. Sequencing reads were mapped to the human genome using Bowtie with two mismatches (28). Phantom peak calling was used to evaluate ChIP-seq quality. Both EBNA3C ChIP-seq replicates had a Quality tags >1, in accordance with the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) high quality data standard (29). The ChIP-seq processing pipeline (SPP) identified over 13,000 EBNA3C peaks with irreproducible discovery rates (IDRs) <0.01 (29, 30). EBNA3C peaks were annotated using the ENCODE GM12878 LCL epigenetic landscape, which divides the genome into seven functional domains defined by unique histone modifications (31). EBNA3C sites were 38% (4,969 sites) at strong enhancers, marked by high H3K4me1 and H3K27ac; 25% (3,287 sites) at weak enhancers, marked by intermediate H3K4me1 and little H3K27ac; 8% (1,021 sites) at active promoters, marked by high H3K4me3 and H3K9ac; 8% (1,108 sites) at weak or poised promoters, marked by high H3K4me3 and low H3K27ac; or high H3K27me3, and 16% (2,093 sites) at heterochromatin, marked by the absence of detectable histone modifications (Fig. 1A). EBNA3C peaks were significantly enriched over background controls at weak promoters, poised promoters, and strong and weak enhancers (Fisher's exact test: P < 1 × 10−5) (Fig. S1A), identifying EBNA3C as a TF that significantly affects enhancer and promoter activity.

Fig. 1.

Genome-wide distribution of EBNA3C sites and EBNA3C site overlap with EBNA2/RBPJ, BATF/IRF4, SPI1/IRF4, and RUNX3. (A) Genome-wide distribution of EBNA3C DNA binding by chromatin states (%). EBNA3C distribution calculated based on the chromatin state of GM12878 cells; 12,992 EBNA3C sites within annotated genomic regions were used to identify the genome-wide distribution of EBNA3C sites. (B) Venn diagram showing EBNA3C site overlap with RUNX3, SPI1/IRF4, EBNA2/RBPJ, or BATF/IRF4 (±250 bp of EBNA3C sites).

EBNA3C and EBNA2/RBPJ Peaks Overlap.

Reanalysis of previous EBNA2 and RBPJ data (32) using IDR identified the top 5,000 EBNA2 and 10,000 RBPJ sites. Overall, 9% of EBNA3C sites overlapped with EBNA2/RBPJ sites and 7% overlapped with RBPJ sites lacking EBNA2 (Fig. 1B). EBNA3C was 84% at DNA sites without significant RBPJ, whereas most EBNA2 sites coincided with RBPJ. EBNA2-associated RBPJ sites had twofold higher signals than RBPJ sites that lacked EBNA2, indicating a strong EBNA2 effect on RBPJ association with DNA (32). In contrast, RBPJ sites with or without EBNA3C had similar signals (Fig. S1C).

EBNA3C Site-Enriched Cell TF Motifs.

Motif analysis using HOMER identified EBNA3C sites (±250 bp) to be significantly enriched for cell TF-binding motifs, including IRF4 (49%), RUNX (44%), SPI1-IRF4 (46%), REL (18%), E2A (21%), and EBF1 (12%). Homer known motif enrichment analysis identified SPI1-IRF4 (50%), IRF4 (30%), AP-1 (37%), RUNX (40%), JUN-AP1 (15%), ETS1 (34%), SPI1 (21%), and ISRE (10%).

EBNA3C Sites Are Highly Associated with Cell TFs.

ENCODE GM12878 LCL ChIP-seq data were used to elucidate EBNA3C site cell TF cooccupancies. Cell TFs, including those identified by motif (Fig. 2), frequently cooccupied EBNA3C DNA sites (±250 bp) (Table S1). EBNA3C site-associated cell TFs included RUNX3 (64%), BATF (55%), ATF2 (51%), IRF4 (41%), MEF2A (35%), PAX5 (34%), SPI1 (29%), BCL11a (28%), SP1 (26%), TCF12 (23%), RELA (23%), POU2F2/Oct2 (23%), RBPJ (16%), EBNA2 (9%), RXRA (7%), and Sin3A (1%) (Table S1). In B and T lymphocytes, IRF4 (or IRF8) frequently bind with ATF to composite elements (AICEs) or with ETS to composite elements (EICEs) (33–35). EBNA3C can bind to IRF4 or IRF8 (24). Indeed, AP-1/IRF4 motifs were highly enriched at EBNA3C sites (Fig. 2). Furthermore, EBNA3C sites also coincided with RUNX3 (Fig. 1B). Overall, 37% of EBNA3C sites coincided with BATF and IRF4 and 20% of EBNA3C sites coincided with SPI1 and IRF4 (Fig. 1B). Thus, EBNA3C was highly associated with AICEs or EICEs.

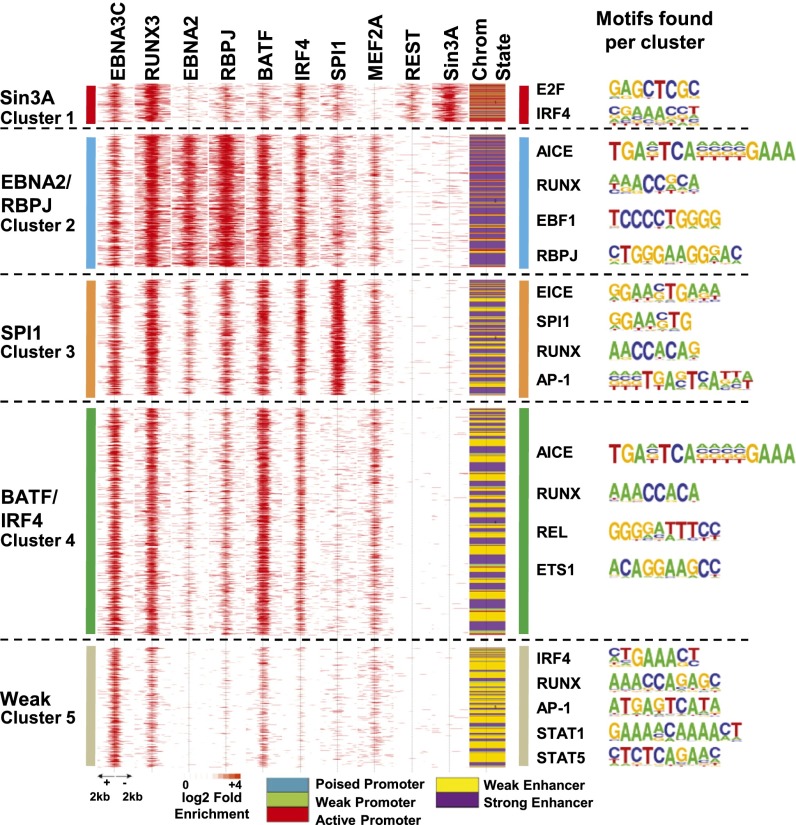

Fig. 2.

EBNA3C-associated cell TF clusters, chromatin state, and associated motifs at different clusters. Partitioning Around Medoids (PAM) clustering was used to cluster all nonheterochromatin EBNA3C sites together with EBNA2 and cell TFs into five unique clusters. ChIP-seq signals centered at the EBNA3C sites with neighboring ±2 kb were shown on a red (highest binding) to white (no binding) scale. The chromatin state distribution of EBNA3C sites are represented in the column titled “State.” Enriched motifs at each cluster are shown next to the clusters.

EBNA3C Promoter and Enhancer Site-Associated Cell TFs Divided into Five Unique Clusters Using Partitioning Around Medoids.

EBNA3C sites coincided with EBNA2, RBPJ, RUNX3, BATF, IRF4, SPI1, MEF2A, REST/NRSF, and Sin3A in five distinct clusters (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, cluster 1 was highly enriched for RUNX3, Sin3A, and REST/NRSF. Sin3A is a repressive scaffold for histone deacetylases 1 and 2 (HDAC 1 and 2) (36), but was mostly at active promoter-associated EBNA3C sites. Repressive HDACs frequently bind to active promoters (37). Sin3A HDAC-repressive complexes may reset chromatin to preactivation levels to prevent effects of prolonged gene activation (37). Sin3A cluster-enriched cell TF motifs included E2F and IRF4.

EBNA3C cluster 2 was strongly enriched for AP-1/IRF4 (AICE), RUNX, RBPJ, and EBF1 motifs and had strong EBNA2, RBPJ, RUNX3, BATF, and IRF4 signals, with predominantly strong enhancer marks (Fig. 2, purple). EBNA3C cluster 3 was enriched in IRF4/SPI1 (EICE), SPI1, RUNX and AP-1 motifs and had high SPI1, RUNX3, BATF, and IRF4 signals with strong enhancer marks. Cluster 4 was enriched for AP1/IRF4 (AICE), RUNX, REL, and ETS1 motifs and had prominent RUNX3, BATF, IRF4, and EBNA3C signals, with minimal SPI1 signals and weak enhancer marks (Fig. 2, yellow). Cluster 5 was enriched for STAT1 and STAT5 motifs, for which there are no ENCODE data, and had moderate EBNA3C signals, with weak RUNX3, BATF, and MEF2A signals, with weak enhancer marks.

RBPJ was at only 16% of EBNA3C sites, which were mostly cluster 2 strong enhancers with high EBNA2, RBPJ, RUNX3, and EBNA3C signals. In contrast, EBNA3C clusters 1 and 4 and especially five sites (Fig. 2) had much lower RBPJ signals than cluster-2 sites, indicating that EBNA3C was associated with DNA at sites that are RBPJ deficient. Anchor plots of Sin3A signals show that Sin3A signals were high in cluster 1 and very low in all other clusters. Anchor plots of EBNA2 or RBPJ signals indicated that EBNA2 or RBPJ signals were much stronger in cluster 2 than in other clusters (Fig. S1B). However, SPI1 signals were only strong at cluster-3 sites, whereas BATF and IRF4 signals were strong at cluster-2, -3, and -4 sites (Fig. S1B). These data are consistent with EBNA2 and RBPJ having strong enhancer effects at EBNA3C cluster-2 sites.

EBNA3C Signals Are Affected by Cooccupancy with RUNX, BATF, IRF4, SPI1, or RBPJ.

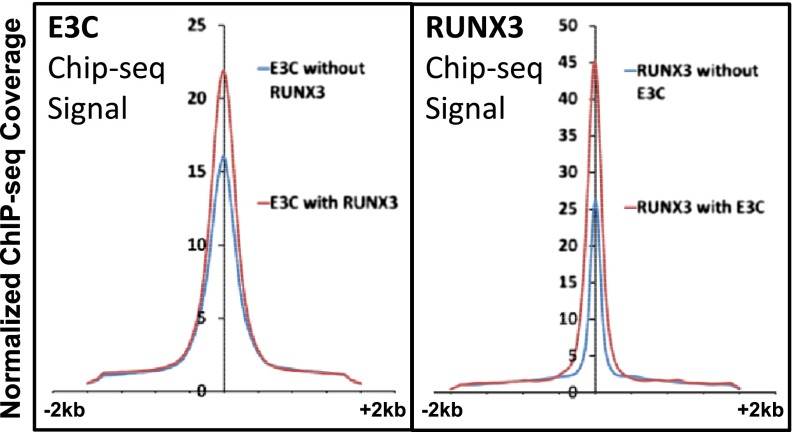

Anchor plots of EBNA3C sites—alone or at sites with RUNX3, BATF, IRF4, or SPI1—had stronger EBNA3C-normalized ChIP-seq signals (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1C). Sites cooccupied with RUNX3, BATF, IRF4, or SPI1, had EBNA3C signals that were increased from 15 to 18 for EBNA3C sites alone to 22–25 for EBNA3C sites with RUNX3, BATF, IRF4, or SPI1 (one-tailed paired t test, P < 10−20) (Fig. S1C). Similarly, RUNX3, BATF, IRF4, or SPI1 had stronger signals at sites cooccupied with EBNA3C than at sites with these factors alone and EBNA3C sites co-occurring with RBPJ or EBNA2 had stronger EBNA3C signals than EBNA3C alone. However, RBPJ and EBNA2 sites with or without EBNA3C had similar signals, consistent with EBNA3C having no incremental effect on EBNA2 or EBNA2 and RBPJ signals (Fig. S1C). EBNA3C sites with or without Sin3A had similar signals, whereas Sin3A sites with EBNA3C had higher signals than Sin3A only sites, (P < 10−30), consistent with EBNA3C recruiting Sin3A to these sites (Fig. S1C). Furthermore, RBPJ signals at sites with Sin3A had lower signals than RBPJ sites alone (Fig. S1D). In contrast, Sin3A signals at Sin3A and RBPJ sites were stronger than Sin3A signals without RBPJ (P < 10−11), consistent with RBPJ tethering Sin3A to DNA (Fig. S1D).

Fig. 3.

Anchor plots of EBNA3C (E3C) or RUNX3 centered at E3C or RUNX3 peaks. E3C (Left) or RUNX3 (Right) was intersected pairwise (±250 bp) with HOMER and the anchor plots of E3C without RUNX3, E3C with RUNX3, or RUNX3 without E3C ChIP-seq signals were plotted around a ±2-kb region.

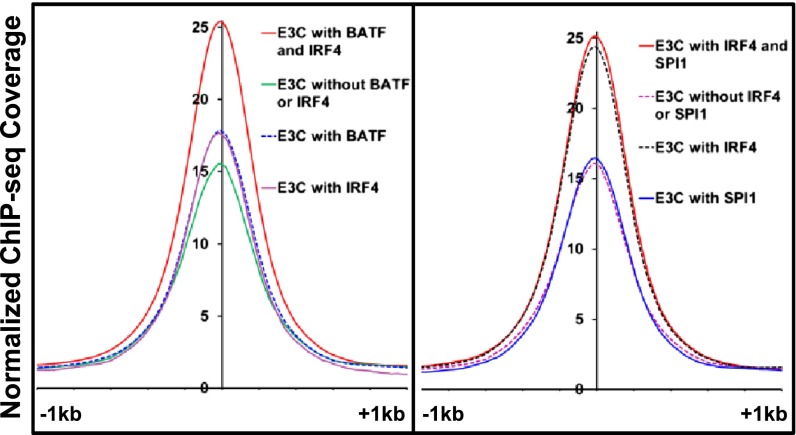

Notably, EBNA3C signals at BATF/IRF4 (AICE) sites were stronger than EBNA3C-alone sites (P < 1 × 10−23), EBNA3C/BATF (P < 10−25) sites, or EBNA3C/IRF4 sites (P < 10−28), consistent with EBNA3C preferential binding to AICE composite sites. In parallel, EBNA3C signals at SPI1/IRF4 (EICE) sites were similar to EBNA3C/IRF4 sites and higher than EBNA3C alone (P < 10−23) or EBNA3C/SPI1 sites (P < 10−27), consistent with EBNA3C’s preferential binding to EICE sites (Fig. 4). Most of EBNA3C/IRF4 sites without SPI1 were associated with BATF (Fig. 1B), accounting for their similar signal.

Fig. 4.

Anchor plots at EBNA3C sites, showing the effects of AICEs (BATF and IRF4, Left) and EICEs (SPI1 and IRF4, Right) on EBNA3C ChIP-seq signals on DNA. ChIP-seq signals were plotted around a ±1-kb region.

EBNA3C Promoter Sites Correlated with Effects on Gene Expression.

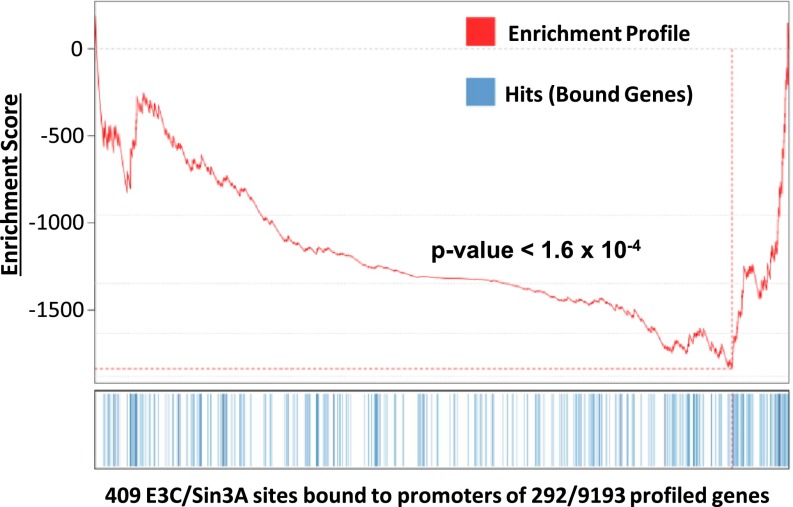

Transcription profiling of conditional EBNA3CHT LCLs under nonpermissive conditions for EBNA3C expression versus the same LCLs transcomplemented with WT EBNA3C expression identify EBNA3C conditionally regulated cell genes (12). Eight hundred and ninety one EBNA3C sites localized within ±2 kb of the transcription start site (TSS) of an EBNA3C dynamically affected cell gene (Fig. S2). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) negatively correlated EBNA3C promoter binding with cell gene repressive effects (P < 1 × 10−6, Fig. S2) (38). GSEA analysis of 409 EBNA3C/Sin3A sites in cluster 1 (Fig. 2) were at 292 affected cell promoters and correlated WT EBNA3C expression levels with normal cell growth and a 28% average lower expression of EBNA3C/Sin3A-affected genes (P < 1.6 × 10−4, Fig. 5), indicative of repressed cell gene expression at EBNA3C- and Sin3A-bound promoters.

Fig. 5.

GSEA analysis of EBNA3C/Sin3A binding and gene expression. The enrichment profile is shown on top, 229 genes with EBNA3C/Sin3A sites at ±2 kb of TSS were indicated with blue vertical lines in the center, and 9,193 genes profiled were ranked from EBNA3C induced (left) to EBNA3C repressed (right).

EBNA3C Site-Associated Histone Modifications.

To evaluate EBNA3C, EBNA2, and associated cell TF effects on epigenetic modifications indicative of enhanced or repressed transcription, ENCODE LCL histone H3K4me1, H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and p300 ChIP-seq signals at EBNA3C sites were analyzed (Fig. S3). EBNA3C cluster-2 sites with significant EBNA2/RBPJ signals had highest H3K4me1, H3K27ac, nucleosome depletion, and p300 signals, with low H3K27me3, indicative of high-level enhancer activity. EBNA3C sites with significant Sin3A signals had high H3K4me3, H3K9ac, and nucleosome depletion consistent with promoter activation. However, GSEA analyses indicate that EBNA3C has repressive effects on cluster-1 promoters, compatible with a model that EBNA3C attenuates promoter overactivation, by recruiting repressive Sin3A complexes to these sites (Fig. 5).

EBNA3C Binds to the p14ARF Promoter and Recruits Sin3A.

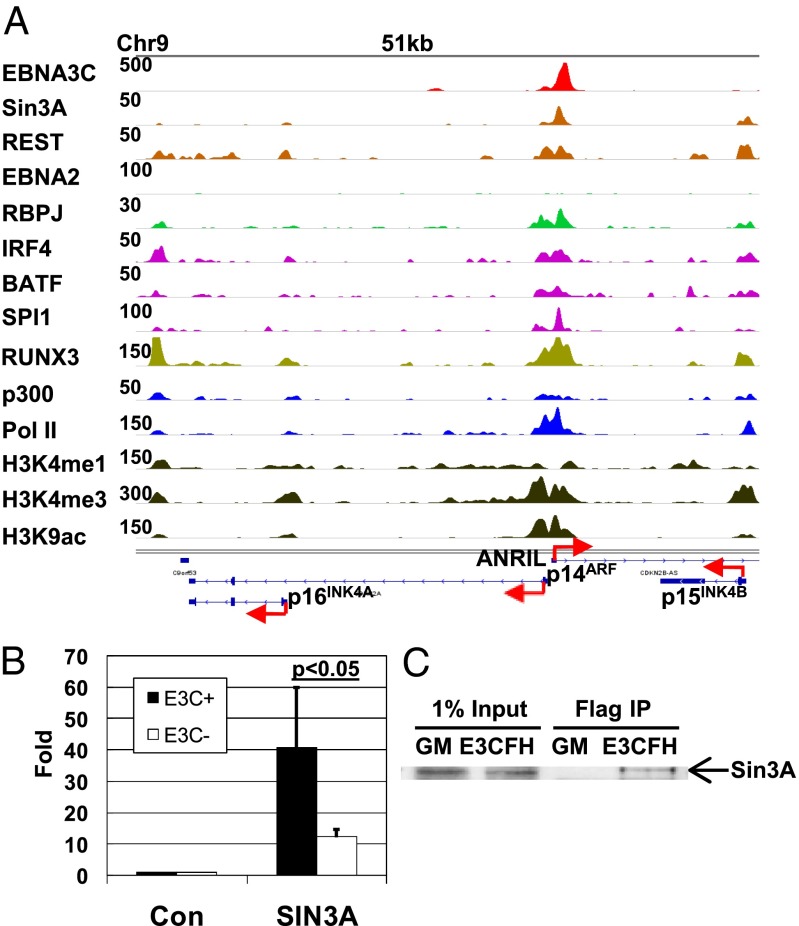

To understand the molecular mechanisms through which EBNA3C represses p14ARF and p16INK4A expression, we investigated EBNA3C binding to these loci. By ChIP-seq, EBNA3C localized to the p14ARF promoter (Fig. 6A). The EBNA3C p14ARF promoter site coincided with strong BATF, IRF4, and SPI1 signals consistent with EBNA3C binding to the p14ARF promoter through AICES or EICES (Fig. 6A). Notably, EBNA2 was absent from the p14ARF promoter site and weak RBPJ signals coincided with EBNA3C, consistent with the hypothesis that EBNA3C can recruit RBPJ to AICE or EICE sites (Fig. 6A). Although RBPJ signals at the p14ARF promoter site were two- to threefold over controls after 10 min of formaldehyde cross-linking, 20 min of cross-linking increased RBPJ signals to 13-fold over control antibody, consistent with RBPJ being more distal to DNA than EBNA3C. These data are consistent with a model in which EBNA3C binds to BATF/IRF4/SPI1 AICE or EICE sites at the p14ARF promoter and recruits RBPJ with its associated repressors, notably including Sin3A (39).

Fig. 6.

EBNA3C site at the p14ARF promoter and association with Sin3A. (A) EBNA3C binding at the p14ARF promoter. Normalized EBNA3C, Sin3A, and other TF tag density signals at the CDKN2A/B locus are shown. Red arrows indicate the direction of transcription. The peak heights are indicated at the left of and for each track. (B) EBNA3CHT LCLs were grown under permissive or nonpermissive conditions for 7 d. Sin3A enrichment at the p14ARF promoter over the control antibody was determined by ChIP-qPCR. (C) Anti-Flag agarose beads were used to immune precipitate EBNA3CFH and associated proteins from EBNA3CFH LCL with GM12878 LCLs as control. EBNA3C-associated Sin3A was detected by Western blotting.

ENCODE Sin3A ChIP-seq data identified Sin3A signals that were coincident with EBNA3C signals at the p14ARF promoter site (Fig. 6A). To test the hypothesis that EBNA3C recruits Sin3A to the p14ARF promoter to repress p14ARF expression, Sin3A ChIP-qPCRs were done using conditional EBNA3CHT LCLs. Under permissive conditions for EBNA3C expression, Sin3A was enriched 41-fold at the p14ARF promoter, normalized to control antibody. Whereas, under nonpermissive conditions for EBNA3C expression, Sin3A was enriched 12-fold compared with control antibody (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that Sin3A binding to p14ARF DNA is EBNA3C dependent, further indication that EBNA3C tethers Sin3A to the p14ARF promoter to repress p14ARF expression. Previous immune florescence studies had shown that EBNA3C extensively colocalizes with Sin3A in LCLs (24). To further evaluate EBNA3C association with Sin3A in LCLs, agarose beads conjugated to anti-Flag antibody were used to pull down EBNA3CHF and associated proteins from EBNA3CHF LCLs. Western blotting showed that EBNA3CHF immune precipitated 0.5–1% of input Sin3A from EBNA3CHF LCLs, whereas Sin3A was not detected in immune precipitates from control non–HF-tagged GM12878 LCLs (GM) (Fig. 6C). Together with previous studies, these results indicate that recruitment of Sin3A complexes to the p14ARF promoter is EBNA3C dependent.

EBNA3C Binds to MYC Enhancers, the pRB Promoter, and BIM Enhancers.

EBNA2 and EBNALP induce MYC expression within 24 h after EBV infection of resting B lymphocytes. EBNA2 binds to multiple enhancer sites 400–500 kb upstream of MYC, causing enhancer looping to the MYC promoter, cell-cycle entry, and cell proliferation (32). After EBNA3C expression is turned on in infected B cells, EBNA3C attenuates MYC expression, preventing MYC overexpression-induced apoptosis (40). LCL growth requires MYC modulation and expression of antiapoptotic BCL2 family proteins. However, EBNA3C can also up-regulate MYC when its expression is low. EBNA3C up-regulates MYC 1.3-fold (P < 1 × 10−4) in EBNA3CHT LCLs (12). EBNA3C localized to 18 sites upstream of MYC (Fig. 7), a region deficient in other annotated genes. These sites have pronounced H3K4me1, H3K27Ac, Pol II, and p300 enhancer marks, implicating EBNA3C in MYC up-regulation.

Fig. 7.

EBNA3C sites upstream of MYC. EBNA3C, EBNA2, RBPJ, IRF4, BATF, SPI1, EBF, Pol II, and histone signals at MYC and up to ∼600 kb upstream are shown.

pRb is frequently inactivated in tumors, and human papilloma virus- or polyomavirus-infected cells have low pRb levels, which enable continuous cell proliferation. EBNA3C can associate with and decrease pRb (41). EBNA3C down-regulated pRB 1.21-fold in conditional EBNA3C transcription-profiling experiments (12). EBNA3C and Sin3A peaks at the pRB promoter and enhancer likely mediate pRB repression (Fig. S4). EBNA3C was also significantly enriched at the IRF4 and BATF promoters (Fig. S4). EBNA3C and Sin3A localization at the BIM promoter support ChIP-qPCR studies of EBNA3C-mediated BIM repression (21, 42). Strong EBNA3C signals likely down-regulate BIM by bringing Sin3A to BIM promoter and enhancer sites (Fig. S5B). These findings position EBNA3C at cell genes critical for cell growth and survival.

Discussion

EBNA3C amino acids 50–400 are essential for continuous LCL growth. This region includes an IRF4-binding domain, amino acids 130–150 (24); an RBPJ-binding domain, amino acids 180–231 (7, 8, 18); and an SPI1-binding domain, amino acids 181–365 (11). These EBNA3C-associated cell TFs are likely critical for EBNA3C association with DNA and transcription effects.

Previously, EBNA3C interaction with DNA could only be assessed at a few sites (11, 19). The EBNA3C ChIP-seq analysis presented here finds EBNA3C at over 13,000 cell DNA sites. Surprisingly, RBPJ is at only <16% of EBNA3C sites. EBNA3C/RBPJ DNA signals were similar to EBNA3C IRF4/BATF/SPI1/RUNX3 DNA signals (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1C). EBNA3C-associated RBPJ had lower DNA signals than EBNA2-associated RBPJ, consistent with the model that EBNA3C-associated RBPJ is not directly binding DNA, but is tethered to DNA by EBNA3C binding to composite IFR4/BATF/SPI1/RUNX3 sites.

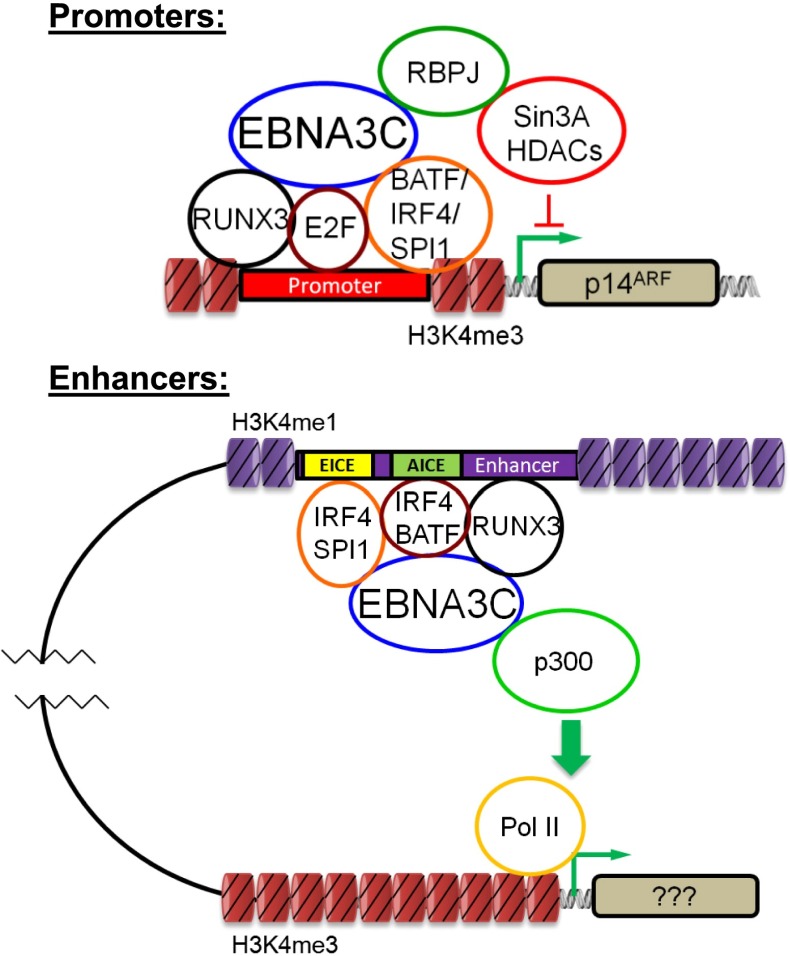

EBNA3C is most frequently bound to DNA by AICE (IRF4/BATF) and EICE (IRF4/SPI1) sites. EBNA3C signals are also positively affected by RUNX3. RUNX3, IRF4, BATF, and SPI1 likely bridge EBNA3C to DNA. ChIP-seq and EMSA experiments implicate cooperative BATF/IRF4 binding to AICE (33–35). Our data detect extensive EBNA3C interactions with AICE and EICE sites to drive LCL proliferation. IRF8 can replace IRF4 in AICE complexes in B- and T-cell development and EBNA3C can bind to IRF8 (24). These data further underscore the extent to which EBV uses intrinsic B-cell developmental pathways to immortalize B cells (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

EBNA3C binds to promoters via RUNX3, IRF4, and E2F to recruit Sin3A repressor complexes (Sin3A, HDACs 1 and 2, and RBPJ). This complex represses the nearby p14ARF TSS. EBNA3C binds to H3K4me1-enriched enhancers via BATF/IRF4 and/or SPI1, RUNX3 to recruit p300 and drive distal target gene expression.

EBNA3C repression of p16INK4A and p14ARF expression is essential for LCL growth (14, 15). In LCLs this repression is marked by increased H3K27me3 across this locus (14, 17). However, the mechanisms through which EBNA3C mediates repression were unclear. Using ENCODE data, we found Sin3A- and REST/NRSF-repressive complexes associated with EBNA3C at the p14ARF promoter. EBNA3C bound to Sin3A and EBNA3C-Sin3A complexes repressed p16INK4A and p14ARF transcription (Fig. 6). Conditional EBNA3C inactivation resulted in loss of Sin3A at this site, indicating that EBNA3C is required for Sin3A DNA binding. The CDKN2A (p14ARF and p16INK4A) and CDKN2B (p15INK4B) sites are highly dynamic in chromatin conformation (43). The p15INK4B promoter can loop to the p16INK4A promoter to coregulate both genes, looping out the p14ARF promoter (36). Because EBNA3C represses p14ARF and p16INK4A simultaneously, these repressive effects are likely coregulated by the p14ARF promoter, via looping.

These experiments further illustrate the extent to which EBV has evolved to use preexisting B-cell programs to drive cell-cycle entry to maintain infected cell persistence or alternatively to enable virus replication.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

LCLs transformed by a recombinant EBV BACmid in which EBNA3C was C-terminally tagged with HA and Flag epitopes (EBNA3CFH) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) Fetal Plex animal serum complex (Gemini) and 2 mM l-glutamine, and 4HT withdraw experiments were done as described (6).

ChIP-Seq.

Anti-HA antibody (Abcam, ab9110) was used to immune precipitate EBNA3CFH from formaldehyde cross-linked EBNA3CFH LCLs. After extensive washing, Protein-DNA complexes were eluted and cross-linking was reversed (31). The purified DNA was sequenced using a HiSEq 2500 (Illumina).

ChIP-Seq Data Analyses.

ChIP-seq reads were mapped to hg18 using Bowtie (27), allowing one alignment per read and two mismatches per read. The 39.9 and 43.2 million unique reads from biologic EBNA3C replicates 1 and 2, of which 37.5 million reads (78.8%) and 35.9 million reads (77.8%) mapped to the hg18 genome. Phantom peak calling was used for quality control (29). SPP was used to call peaks with an IDR < 0.01 (29, 30). EBNA3C peaks were mapped to the hg18 GM12878 chromatin states (31).

Enriched Motif Calling.

Sequences ±250 bp of EBNA3C sites per cluster (Fig. 2) were extracted for motif analysis using HOMER. Random sites with identical chromatin distribution were used as control. HOMER was used to identify enriched motifs around these EBNA3C sites (44). Additional materials and methods are available SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anshul Kundaje, Burak Alver, Richard Sandstrom, and Ben Gewurz for helpful input and discussions. These experiments were supported by Grants R01CA047006, R01CA170023, R01CA085180, and R01CA131354 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the US Public Health Service.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The ChIP sequence data reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. GSE52632).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1321704111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rickinson A, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Howley P, Knipe D, editors. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2655–2700. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kieff E, Rickinson A. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Howley P, Knipe D, editors. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 2603–2654. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomkinson B, Robertson E, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins EBNA-3A and EBNA-3C are essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J Virol. 1993;67(4):2014–2025. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2014-2025.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen A, Divisconte M, Jiang X, Quink C, Wang F. Epstein-Barr virus with the latent infection nuclear antigen 3B completely deleted is still competent for B-cell growth transformation in vitro. J Virol. 2005;79(7):4506–4509. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4506-4509.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomkinson B, Kieff E. Use of second-site homologous recombination to demonstrate that Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 3B is not important for lymphocyte infection or growth transformation in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66(5):2893–2903. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2893-2903.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maruo S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein EBNA3C is required for cell cycle progression and growth maintenance of lymphoblastoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(51):19500–19505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604919104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 3C domains necessary for lymphoblastoid cell growth: Interaction with RBP-Jkappa regulates TCL1. J Virol. 2009;83(23):12368–12377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01403-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruo S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein EBNA3C residues critical for maintaining lymphoblastoid cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(11):4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813134106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allday MJ, Farrell PJ. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA3C/6 expression maintains the level of latent membrane protein 1 in G1-arrested cells. J Virol. 1994;68:3491–3498. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3491-3498.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin J, Johannsen E, Robertson E, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C putative repression domain mediates coactivation of the LMP1 promoter with EBNA-2. J Virol. 2002;76(1):232–242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.232-242.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao B, Sample CE. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C activates the latent membrane protein 1 promoter in the presence of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 through sequences encompassing an spi-1/Spi-B binding site. J Virol. 2000;74(11):5151–5160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5151-5160.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao B, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C regulated genes in lymphoblastoid cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(1):337–342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017419108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piovan E, et al. Chemokine receptor expression in EBV-associated lymphoproliferation in hu/SCID mice: Implications for CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in lymphoma generation. Blood. 2005;105(3):931–939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruo S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens 3C and 3A maintain lymphoblastoid cell growth by repressing p16INK4A and p14ARF expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(5):1919–1924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019599108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skalska L, et al. Induction of p16(INK4a) is the major barrier to proliferation when Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transforms primary B cells into lymphoblastoid cell lines. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(2):e1003187. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harth-Hertle ML, et al. Inactivation of intergenic enhancers by EBNA3A initiates and maintains polycomb signatures across a chromatin domain encoding CXCL10 and CXCL9. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(9):e1003638. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skalska L, White RE, Franz M, Ruhmann M, Allday MJ. Epigenetic repression of p16(INK4A) by latent Epstein-Barr virus requires the interaction of EBNA3A and EBNA3C with CtBP. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(6):e1000951. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao B, Marshall DR, Sample CE. A conserved domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens 3A and 3C binds to a discrete domain of Jkappa. J Virol. 1996;70(7):4228–4236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4228-4236.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson ES, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 3C modulates transcription through interaction with the sequence-specific DNA-binding protein J kappa. J Virol. 1995;69(5):3108–3116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3108-3116.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClellan MJ, et al. Downregulation of integrin receptor-signaling genes by Epstein-Barr virus EBNA 3C via promoter-proximal and -distal binding elements. J Virol. 2012;86(9):5165–5178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07161-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paschos K, Parker GA, Watanatanasup E, White RE, Allday MJ. BIM promoter directly targeted by EBNA3C in polycomb-mediated repression by EBV. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):7233–7246. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiménez-Ramírez C, et al. Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-3C is targeted to and regulates expression from the bidirectional LMP-1/2B promoter. J Virol. 2006;80:11200–11208. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00897-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClellan MJ, et al. Modulation of enhancer looping and differential gene targeting by Epstein-Barr virus transcription factors directs cellular reprogramming. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(9):e1003636. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee S, et al. The EBV Latent Antigen 3C Inhibits Apoptosis through Targeted Regulation of Interferon Regulatory Factors 4 and 8. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(5):e1003314. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight JS, Lan K, Subramanian C, Robertson ES. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C recruits histone deacetylase activity and associates with the corepressors mSin3A and NCoR in human B-cell lines. J Virol. 2003;77(7):4261–4272. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4261-4272.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radkov SA, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. J Virol. 1999;73(7):5688–5697. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5688-5697.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touitou R, Hickabottom M, Parker G, Crook T, Allday MJ. Physical and functional interactions between the corepressor CtBP and the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA3C. J Virol. 2001;75(16):7749–7755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7749-7755.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landt SG, et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1813–1831. doi: 10.1101/gr.136184.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kharchenko PV, Tolstorukov MY, Park PJ. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(12):1351–1359. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ernst J, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473(7345):43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao B, et al. Epstein-Barr virus exploits intrinsic B-lymphocyte transcription programs to achieve immortal cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(36):14902–14907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108892108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tussiwand R, et al. Compensatory dendritic cell development mediated by BATF-IRF interactions. Nature. 2012;490(7421):502–507. doi: 10.1038/nature11531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasmacher E, et al. A genomic regulatory element that directs assembly and function of immune-specific AP-1-IRF complexes. Science. 2012;338(6109):975–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1228309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ochiai K, et al. Transcriptional regulation of germinal center B and plasma cell fates by dynamical control of IRF4. Immunity. 2013;38(5):918–929. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagy L, et al. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell. 1997;89(3):373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, et al. Genome-wide mapping of HATs and HDACs reveals distinct functions in active and inactive genes. Cell. 2009;138(5):1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou S, Fujimuro M, Hsieh JJ-D, Chen L, Hayward SD. A role for SKIP in EBNA2 activation of CBF1-repressed promoters. J Virol. 2000;74(4):1939–1947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1939-1947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikitin PA, et al. An ATM/Chk2-mediated DNA damage-responsive signaling pathway suppresses Epstein-Barr virus transformation of primary human B cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8(6):510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knight JS, Sharma N, Robertson ES. Epstein-Barr virus latent antigen 3C can mediate the degradation of the retinoblastoma protein through an SCF cellular ubiquitin ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(51):18562–18566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503886102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paschos K, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latency in B cells leads to epigenetic repression and CpG methylation of the tumour suppressor gene Bim. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(6):e1000492. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kheradmand Kia S, et al. EZH2-dependent chromatin looping controls INK4a and INK4b, but not ARF, during human progenitor cell differentiation and cellular senescence. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2009;2(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38(4):576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.