Significance

P2X receptors are trimeric proteins in which an extracellular transmitter (ATP) binds to open a transmembrane ion permeation pathway. We have designed a thiol-reactive, light-sensitive azobenzene molecule that can attach between cysteines introduced by mutagenesis into different channel subunits. Such chemically modified channels can be opened within milliseconds by irradiation at 440 nm, and closed by light at 360 nm, in the absence of any extracellular ligand. A similar result was obtained for heterotrimeric P2X2/3 receptors and for structurally unrelated (but trimeric) acid-sensing ion channels. The work extends our understanding of the molecular mechanism of gating and provides a tool to investigate the role of P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels in intact cells and tissues.

Abstract

P2X receptors are trimeric membrane proteins that function as ion channels gated by extracellular ATP. We have engineered a P2X2 receptor that opens within milliseconds by irradiation at 440 nm, and rapidly closes at 360 nm. This requires bridging receptor subunits via covalent attachment of 4,4'-bis(maleimido)azobenzene to a cysteine residue (P329C) introduced into each second transmembrane domain. The cis–trans isomerization of the azobenzene pushes apart the outer ends of the transmembrane helices and opens the channel in a light-dependent manner. Light-activated channels exhibited similar unitary currents, rectification, calcium permeability, and dye uptake as P2X2 receptors activated by ATP. P2X3 receptors with an equivalent mutation (P320C) were also light sensitive after chemical modification. They showed typical rapid desensitization, and they could coassemble with native P2X2 subunits in pheochromocytoma cells to form light-activated heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors. A similar approach was used to open and close human acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs), which are also trimers but are unrelated in sequence to P2X receptors. The experiments indicate that the opening of the permeation pathway requires similar and substantial movements of the transmembrane helices in both P2X receptors and ASICs, and the method will allow precise optical control of P2X receptors or ASICs in intact tissues.

P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) are trimeric membrane ion channels gated by binding extracellular ligands. P2X receptors are gated by extracellular ATP, and their physiological roles include neuroeffector transmission, primary afferent transmission (e.g., taste, hearing, chemoreception), central control of respiration, and neuroinflammation (1–3). ASICs are gated by protons and are involved in pain sensation (4, 5). The experimental study of ligand-gated channels in intact tissues is often hampered by difficulties in application of the appropriate ligand while recording ion channel activity in the millisecond time domain, and there are advantages to controlling channel activation by surrogate optical methods. The increase in our knowledge of molecular and atomic structure of ligand-gated channels over the past 10 years has allowed one such approach (photoswitchable tethered ligands) to become much more sophisticated, because cysteines can be introduced into the channel protein exactly where required to form an attachment point. The method has been applied to pentameric nicotinic receptors (6) and tetrameric glutamate receptors (7, 8). Although attaching ligands through photoswitchable tethers is proving extremely valuable, an intimate structural knowledge of a closed and open state of a channel also allows for optical control of conformation at parts of the protein that are remote from the agonist binding site (9–11).

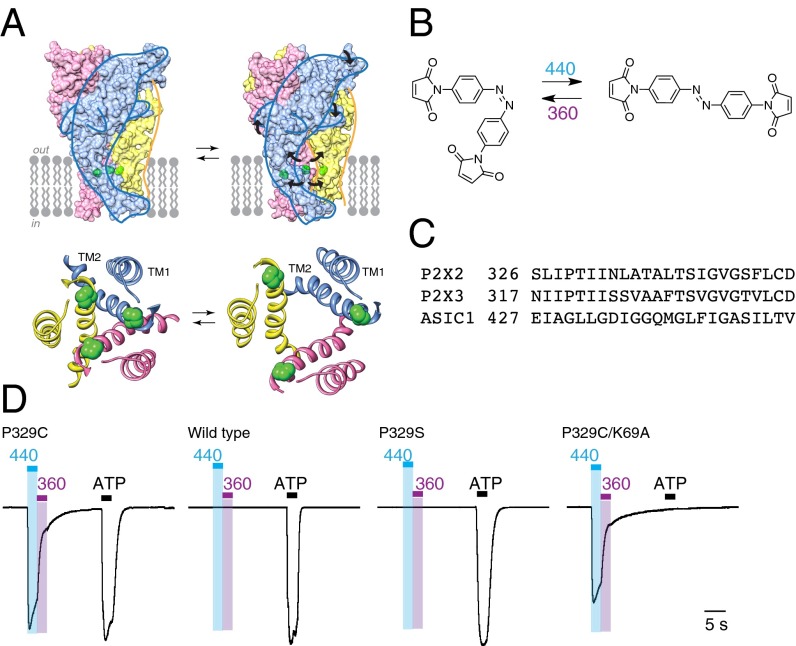

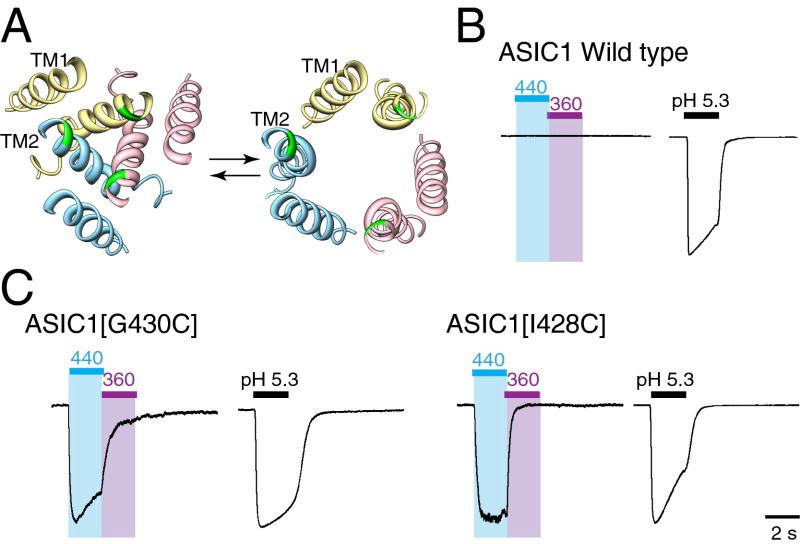

High-resolution structures are available for P2X receptors (closed: ref. 12; open: ref. 13) and ASICs (closed: refs. 14 and 15; open: ref. 16). In both these trimeric channels the second of the two transmembrane domains (TM2) of each subunit lines the permeation pathway (12–14, 16, 17), and the outermost ends of the TM2s undergo substantial lateral displacement when the channel opens (Fig. 1A) (13, 16). We therefore reasoned that the energy provided by an azobenzene molecule undergoing cis to trans isomerization should be sufficient to force apart the TM2 domains and open the permeation pathway.

Fig. 1.

Light activation of P2X2 receptors. (A) Models of rat P2X2 receptor showing closed (Left) and open (Right) conformations. (Upper) Space-fill of trimeric holoprotein. (Lower) Ribbon representation of TM domains, from extracellular side. The positions of P329 are indicated in green. (B) BMA, in its cis state (Left) and trans state (Right). (C) Aligned sequences of second transmembrane domains of rat P2X2 and P2X3 receptors, and human ASIC1a. (D) Light-activated P2X2[P329C] receptors. Currents were evoked by illumination at 440 nm (2 s, blue bar) and turned off by illumination at 360 nm (2 s, violet bar). Light-induced currents were 35% ± 4% (n = 11) of the amplitude of maximum currents evoked by ATP. There was no effect of 440-nm or 360-nm illumination at wild-type P2X2 receptors or at P2X2[P329S] receptors (middle traces), but normal responses to ATP. When the P329C mutation was combined with K69A mutation, ATP (100 μM, 2 s) had no effect (right trace), whereas light-induced currents were present. Preincubated for 10–12 min with BMA (10 μM), in each case. ATP was 3, 10, 10, and 100 μM (left to right). Currents normalized to the peak amplitude evoked by ATP, except that P329C/K69A uses the same scale as P329C. Actual peak amplitudes were as follows: P329C 1879 pA, wild type 1937 pA, P329S 1954 pA, and P329C/K69A 1360 pA.

We synthesized a bis(maleimido)azobenzene (Fig. 1B) of molecular dimensions appropriate to react with two cysteines in different subunits: this produced a P2X2 receptor that was opened and closed by different wavelengths of light. We extended the studies to a second member of the P2X family (P2X3) and thus produced an optically controlled heteromeric P2X2/3 receptor. Despite the lack of primary similarity, including the TM2 domain (Fig. 1C), there are similarities between the overall conformational changes that underlie channel opening in P2X receptors and in ASICs (18). We anticipate that the introduction of these engineered channels into cells and animals, when combined with the covalent modification with bis(maleimido)azobenzene, will facilitate the further investigation of the physiological roles of P2X receptors and ASICs.

Results

Synthesis of 4,4′-Bis(maleimido)azobenzene.

4,4′-Bis(maleimido)azobenzene (BMA) (Fig. 1B) was synthesized from 4,4′-azodianiline via a two-step protocol. Initially, 4,4′-azodianiline was reacted with maleic anhydride to form 4,4′-bis(maleamic acid)azobenzene. This species was then converted to 4,4′-bis(maleimido)azobenze in 43% overall yield by the application of acetic anhydride and sodium acetate. The protocol afforded 4,4′-bis(maleimido)azobenzene with only minor water contamination (2.7% by weight), but the product is highly hygroscopic.

Modification of P2X2[P329C] by BMA.

Whole-cell recordings from cells expressing wild-type P2X2 showed typical inward currents (3.0 ± 0.4 nA, n = 14) in response to 2-s applications of ATP (100 μM). In P2X2 receptors with P329C mutation, after treatment with BMA for at least 10 min, blue light at 440 nm evoked an inward current (Fig. 1D); this was never observed in wild-type cells or with cysteine substitutions at nearby positions (L327C, I328C, I331C, I332C, or N333C). The sulfur atom was essential, because light did not elicit currents in P2X2[P329S] receptors. Changing the irradiation from 440 nm to near UV light at 360 nm rapidly terminated the inward current (Fig. S1).

Light (440 nm) evoked no inward currents in cells not treated with BMA. As the duration of exposure to BMA (10 μM) increased, the current elicited by the same 2-s light application also increased, and measurements showed that BMA associated with the channel according to a first-order reaction with kon of approximately 250 M−1s−1 (Fig. S1A). BMA alone, without irradiation, had no detectable effect on the holding current during 10- to 12-min incubation (Fig. S1B). In subsequent experiments, we used 12-min pretreatment with BMA (10 μM).

A threefold increase in intensity (2.7–7.5 mW mm−2) of blue light increased the rate at which the current developed [time constant changed from 121 ± 13 ms (n = 9) to 78 ± 8 ms (n = 9)] (Fig. S2A). Deactivation (at 360 nm) was also faster at 2.0 mW mm−2 (τ = 559 ± 31 ms, n = 9) than at 0.7 mW mm−2 (τ = 761 ± 40 s, n = 9) (Fig. S2A). These relatively small changes suggest that the intensity is near saturation under our experimental conditions with cells on the microscope stage.

Irradiation at 440 nm evoked significant current within a few milliseconds, and this became maximal with light application lasting approximately 300 ms (time constant 69 ± 11 ms, n = 4) (Fig. S2B). The rate of activation of P2X[P329C] receptors by light (time constant 78 ± 8 ms, n = 9) was similar to that using ATP (at 100 μM; time constant 98 ± 18 ms, n = 9) in the same cells, although under the present recording conditions we have not optimized the kinetics of ATP application. With maximal power (7.5 mW mm−2 under the present conditions), maximal duration of light of 1 s, and maximal BMA exposure of 12 min, the currents evoked by light were typically approximately 35% (range 13–58%, n = 11) of those evoked by a maximal concentration of ATP (100 μM). ATP could elicit additional current after maximal light, but light had no effect when applied after maximal ATP. Currents at light-activated P2X2 receptors showed modest desensitization during prolonged light applications (Fig. S2C, Left) that was comparable to that reported for P2X2 receptors activated by ATP (19, 20). Deactivation was measured from the rate of current decay after a brief pulse of 440 nm light: the BMA trans state isomerized back to the cis state at 3.0% ± 0.3% s−1 (n = 5) (Fig. S2C). The optimal wavelengths for activation and inactivation of the modified P2X2 receptor by light were 440 nm and 360 nm, respectively (Fig. S3), and highly reproducible responses were observed with repetitive illumination at these wavelengths.

ATP binding was not required for activation by light. Removal of the lysine residue at position 69 is well known to reduce dramatically the effect of ATP (20, 21), consistent with its direct interaction with the γ-phosphate oxygen atoms in the ATP-bound open channel structure (13). We introduced this mutation into the P329C channel and confirmed that ATP had no effect even at concentrations of 100 μM (Fig. 1D). However, the ability of light to activate this channel was unaltered.

Light and ATP Activate P2X2 Channels with the Same Properties.

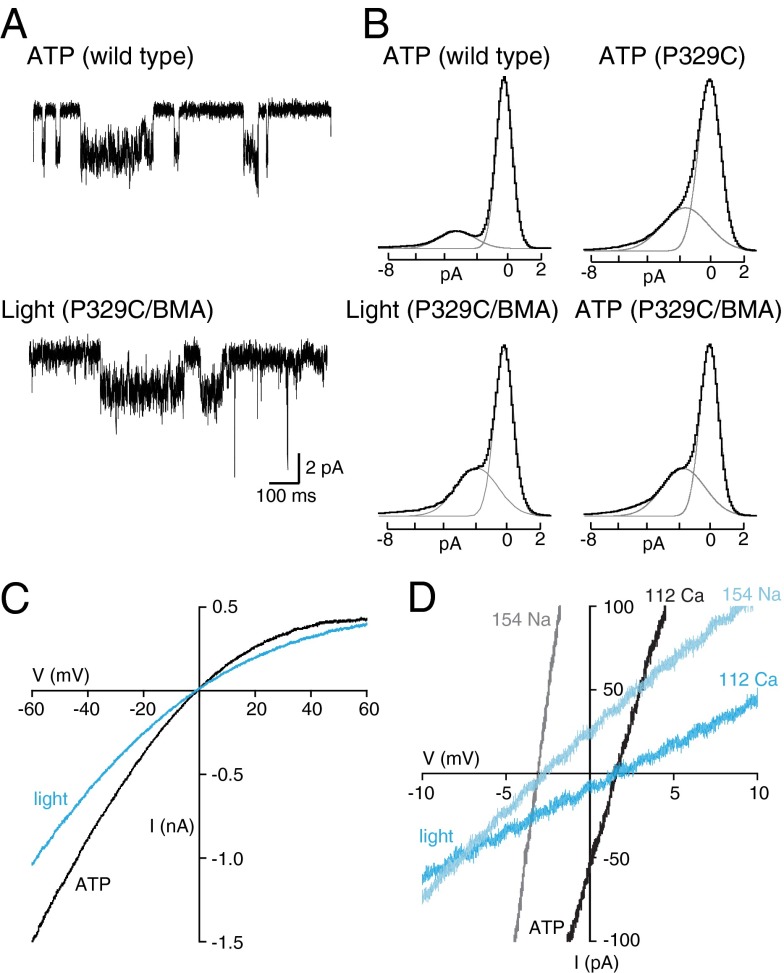

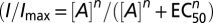

Single-channel currents activated by ATP were somewhat smaller in amplitude in P329C receptors than in wild-type channels (1.7 pA vs. 3.0 pA at −120 mV) (Fig. 2A). However, in the P329C channel treated with BMA, there was no difference between the unitary currents activated by light and those activated by ATP (Fig. 2B). P2X2 receptors show marked inward rectification, and this is dependent on expression level (20, 22). We found that for comparable levels of expression, the light-activated current and the ATP-activated current showed similar rectification (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Same permeation properties of light-gated and ATP-gated P2X2 receptors. (A) Single-channel currents from cells expressing wild-type or P329C receptors. (Upper) Wild-type receptors in ATP (3 μM). (Lower) P2X2[P329C] receptors after treatment with BMA and exposure to 440 nm light. (B) All-points histograms for wild-type receptors activated by ATP, P329C receptors activated by ATP, P329C receptors after BMA treatment activated by light, and P329C receptors after BMA treatment activated by ATP. (C) Current–voltage plots for currents evoked by light (blue) and ATP (black) from cell expressing the P2X2[P329C] receptor. (D) Current–voltage plots from two cells expressing the P2X2[P329C] receptor activated by light (blue traces) or ATP (black and gray traces). Shift in reversal potential observed between external calcium (112 mM) and sodium (154 mM) was similar for P2X2[P329C] receptors gated by light (blue) and by ATP (black).

Calcium permeability is an important feature of P2X receptors (19, 20, 23, 24). Fig. 2D shows that the relative permeability to calcium (PCa/PNa) was similar for channels whether gated by light or by ATP. For P2X2[P329C] receptors gated by light, PCa/PNa was 2.6 ± 0.1 (n = 6), and for ATP-evoked currents this was 2.5 ± 0.1 (n = 6). This calcium permeability is the same as observed for wild-type P2X2 receptors activated by ATP (PCa/PNa = 2.7 ± 0.1, n = 10) (24). Several P2X subtypes become permeable to large organic cations such as N-methyl-d-glucamine when activated by ATP, and this pore dilation can also be studied by measuring the uptake of fluorescent dyes (20, 25). We found that exposure of P2X2[P329C] receptors to blue (440 nm) light for 2 s elicited significant entry of YO-PRO-1, a dye that becomes fluorescent on binding to nucleic acid (Fig. S4). By this criterion, the permeation pathway of the light-activated P2X2 receptor also resembles that of the native channel opened by ATP.

The homotrimeric P2X receptor presents three identical ATP binding sites, but occupancy of only two of these is sufficient to drive channel opening (26). We constructed concatenated cDNAs that encoded three joined subunits and introduced the P329C mutation into the first and/or second and/or third subunit. The concatemer that contained three P329C substitutions (denoted C-C-C) was activated by blue (440 nm) light (mean current was 456 ± 122 pA, n = 9, with light and 2,147 ± 315 pA, n = 10, with ATP), whereas the wild-type concatemer that contained three prolines (denoted P-P-P) was not activated by light but responded normally to ATP (2,383 ± 185 pA, n = 10) (Fig. S5). We found that the introduction of two cysteine residues also produced robust responses to light (384 ± 33 pA, n = 30) and ATP (2,689 ± 118 pA, n = 30). The response to light was not dependent on the positions of the cysteines in the concatemer (P-C-C, C-P-C, or C-C-P) (P = 0.13, one-way ANOVA). Two of the three forms with a single P329C substitution also gave small responses to light. This was most notable for the form with cysteine in the first of the three concatenated subunits and may reflect aberrant (“heads-up”) channel formation from three N-terminal subunits or from minimal breakdown of the concatemers as observed and discussed previously (26).

Light-Gated Homomeric P2X3 and Heteromeric P2X2/3 Channels.

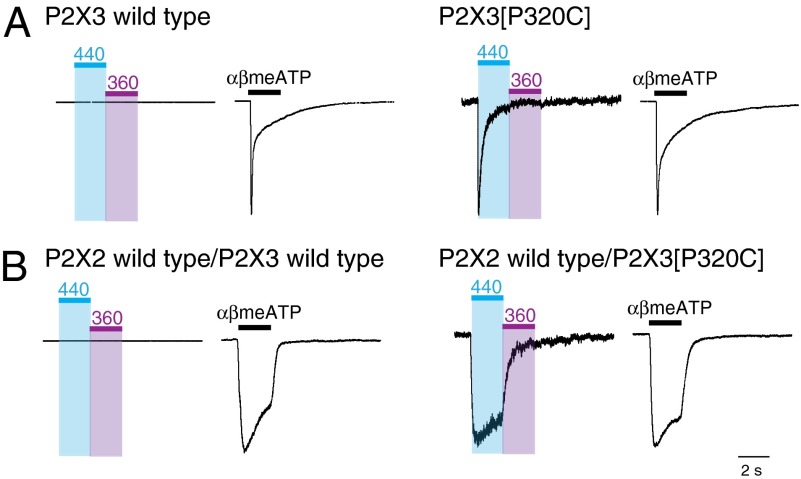

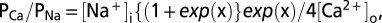

Two features distinguish ATP-evoked currents at homomeric P2X2 and P2X3 receptors (20, 27). First, P2X3 receptors show rapid desensitization: currents evoked by 30 μM ATP decline almost to zero within less than 2 s during a continued application. Second, αβmeATP activates P2X3 receptors at concentrations that have no effect at P2X2 receptors (27). Coexpression of P2X2 and P2X3 subunits in HEK293 cells results in the formation of receptors that are activated by αβmeATP and that show little desensitization during a 2-s application, and this phenotype allows the P2X2/3 heteromeric current to be distinguished from the homomeric forms (27).

We found that blue light (440 nm) activated homomeric P2X3[P320C] receptors pretreated with BMA, and these currents desensitized rapidly during sustained (2 s) light application in a manner similar to that observed for application of ATP (or αβmeATP) (Fig. 3A). The light-activated currents peaked at 129 ± 17 pA (n = 5) and declined to 9 ± 4 pA at 2 s (n = 4), whereas currents activated by αβmeATP (30 μM) peaked at 1,960 ± 234 pA (n = 5) and declined at 2 s to 270 ± 79 pA (n = 4). Light had no effect on wild-type P2X3 receptors (Fig. 3A). Coexpression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptors resulted in a slowly desensitizing heteromeric current in response to αβmeATP (27, 28) (Fig. 3B). This phenotype was also mimicked by light application after BMA treatment. The peak amplitude of the light-activated currents (90 ± 27 pA, n = 8) was less than that observed by αβmeATP (571 ± 79 pA, n = 8), but the close similarity in the time course of the evoked currents strongly indicates that light is activating a heteromeric P2X2/3 receptor (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 3.

Optical control of heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors. (A, Left) Whole-cell recordings from HEK293 cells expressing wild-type P2X3 subunit cDNA show rapidly desensitizing currents elicited by αβmeATP (30 μM) but no effect of light (440 nm 2 s, 360 nm 2 s). (A, Right) Cells expressing mutant P2X3[P320C] subunit cDNA showed rapidly desensitizing currents evoked by 440 nm light (8% ± 3% (n = 5) of amplitude of currents evoked by αβmeATP). (B, Left) Recordings from cells cotransfected with wild-type P2X2 and P2X3 subunit cDNAs show slowly desensitizing currents evoked by αβmeATP (30 μM) but no effect of light. (B, Right) Light-evoked currents in cell coexpressing wild-type P2X2 subunit cDNA and P2X3[P320C] subunit cDNA. Heteromeric P2X2/3 receptor current was 16% ± 4% (n = 8) the amplitude of currents evoked by αβmeATP (each measured 2 s after beginning of application). Traces in A and B normalized to the peak current amplitude induced by αβmeATP (amplitudes were as follows: wild-type P2X3, 1,845 pA; P2X3[P320C], 2,394 pA; P2X2 wild type/P2X3 wild type, 860 pA; P2X2 wild type/P2X3[P320C], 917 pA) or by light (amplitudes were as follows: P2X3[P320C], 500 pA; P2X2 wild type/P2X3[P320C], 193 pA).

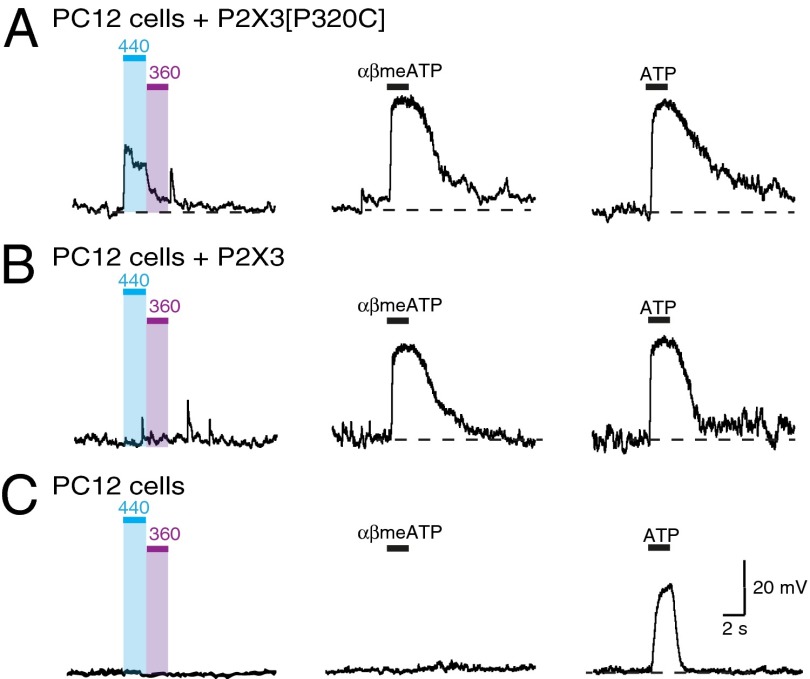

Expression in PC12 Cells.

PC12 cells express P2X2 receptors (19, 29). Whole-cell recordings made 48 h after transfection with GFP showed robust depolarizations (30–50 mV) in response to ATP (30 μM) but no effect of αβmeATP (30 μM) or light (Fig. 4). Cells transfected with P2X3[P320C] receptor cDNA and pretreated with BMA responded to ATP, to αβmeATP (30 μM: 95% ± 17% of depolarization evoked by ATP, n = 7), and to light (40% ± 10% of that caused by ATP, n = 8) (Fig. 4A), whereas cells transfected with wild-type P2X3 receptors responded to both αβmeATP and ATP but not to light (Fig. 4B). The sustained depolarization elicited by αβmeATP is typical of that observed in heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors, either by heterologous expression or in native afferent neurons (20, 27). This indicates that transfection with P2X3 receptor cDNA leads to the production of P2X3 subunits that coassemble with endogenous P2X2 subunits and that light sensitivity can be conferred by this coassembly when these P2X3 subunits contains the P320C substitution.

Fig. 4.

Light activates heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors in PC12 cells. (A) PC12 cells transfected with P2X3[P320C] depolarized by 440 nm irradiation and switched off by 360 nm light. These cells respond to αβmeATP with a sustained depolarization, indicative of heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors. (B) Cells transfected with wild-type P2X3 receptors do not respond to light but are depolarized by αβmeATP. (C) Native PC12 cells (mock transfected with GFP) show responses to ATP (P2X2 receptors) but no effect of light or αβmeATP. ATP and αβmeATP concentrations 30 μM.

Light-Activated ASIC1a Channels.

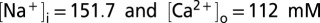

There is no amino acid sequence relatedness between ASIC and P2X receptors. Their ectodomains exhibit quite different folds, and the sequences of their TM2 domains also show very limited conservation (18). However, comparison of open and closed structures suggests that the outer part of TM2 undergoes substantial lateral movements during channel opening in each case (18) (Fig. 5A). We therefore examined whether light might be used to drive the closed to open transition of suitably engineered ASIC.

Fig. 5.

Optical control of trimeric ASIC1 channels. (A) Pore of trimeric chick ASIC1 channels, depicted in desensitized (Left, Proteing Data Bank ID 3IJ4) and open (Right, Protein Data Bank ID 4FZ1) states, showing transmembrane domains viewed from the outside. The residue corresponding to G430 is shown in green. (B) CHO cells expressing wild-type human ASIC1a subunit cDNAs show large inward currents in pH 5.3 but no effect of light (preincubated with BMA). (C) G430C and I428C ASIC1b receptors showed light-activated currents. For G340C, light induced currents were 15% ± 9% (n = 5) the amplitude of currents evoked by pH 5.3, and for I428C this was 10% ± 1% (n = 4). Traces to peak current amplitude induced by pH 5.3 (amplitudes were as follows: wild type, 3,866 pA; G430C, 1,986 pA; I428C, 3,148 pA) or by light (amplitudes were as follows: G430C, 969 pA; I428C, 448 pA).

Human ASIC1a channels were expressed in CHO-K1 cells, and currents were evoked by acidification of the extracellular solution for 2-s periods. Maximal currents were in the range of 2–7 nA (mean = 5,113 ± 705 pA, n = 6), and the EC50 for protons was ∼1 μM (pH 6.0). Wild-type ASICs showed no response to light after 12-min treatment with BMA (Fig. 5B), and similar negative results were observed with Y426C, A429C, and L431C mutations. We observed that ASIC1a[G430C] channels responded to blue (440 nm) light in a manner that closely resembled the effects observed on P2X receptors (Fig. 5C). Channel opening was very rapid: activation by light occurred with τ = 100 ± 11 ms, and activation by pH 5.3 had τ = 69 ± 15 ms in the same five cells (t test, P = 0.132). The peak light-activated current was 350 ± 160 pA (n = 5), approximately 15% of the maximal current activated by protons (pH 5.3: 2.9 ± 0.4 nA, n = 5), and in both cases the current was largely sustained during a 2-s light application. Deactivation occurred at the same rate whether from light (τ = 373 ± 70 ms) or from pH 5.3 (τ = 314 ± 45 ms) in the same five cells (t test, P = 0.5). As for P2X receptors, switching to 360-nm irradiation rapidly closed the channel. The residue that aligns with P329 of the P2X2 receptor is G430 (Fig. 1C), but ASIC1a[I428C] channels provided essentially similar responses (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

To confer light sensitivity on P2X and ASIC proteins, we bridged two transmembrane helices with a photoisomerizable conjugate (BMA) that switches rapidly and reversibly to open or close the channel, depending on the wavelength of light that is applied. A similar strategy has been carried out for certain other proteins, such as restriction enzymes and DNA-binding proteins (11), but in those cases the azobenzene bridged residues are used to render the molecule nonfunctional by inducing disorder. In contrast, here we apply appropriate mechanical forces to the protein to gain optical control of two discrete functional states.

The outer parts of the transmembrane domains of P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels undergo substantial lateral movements during the iris-like rearrangement that underlies channel opening (13, 16, 18), with distances that are similar in magnitude to those predicted for the cis and trans photoisomers of BMA. We predicted that BMA could bridge two cysteines so that in the cis state the β-carbons of the cysteines would be approximately 13 Å apart, and in the trans state they would be approximately 22 Å apart. In our homology models of the P2X2 receptor, the β-carbons of TM2 residue P329 are separated by 12 Å in the closed channel and 23 Å in the open channel. P329 is oriented toward other P329 residues in adjacent subunits and is solvent-exposed. We found that bridging two of the three cysteines was sufficient to open and close trimeric P2X2 receptors, consistent with the finding that only two intact agonist-binding sites (and by inference only two ATP molecules) are required for P2X receptor activation (26). It is noteworthy that at rest (the closed channel state) the BMA was in its higher-energy cis isomer, suggesting it is constrained in this form by the protein to which it is conjugated.

The kinetics of P2X receptor activation were similar whether activated by a maximal concentration of ATP or by blue light. This indicates that the cis-to-trans photoisomerization was not rate limiting and that the activation rate of P2X receptors is determined by the gating rearrangement rather than agonist-binding steps. P2X2 receptors typically show a maximum probability of opening (po) of approximately 0.6 when activated by high concentrations of ATP (30). In the present experiments the P329C mutation had a unitary conductance that was approximately 60% that of the wild-type channel, but we do not know the effects of this mutation on maximal po. Our observation that light-induced currents were up to 50% of ATP-activated currents implies that BMA conjugation followed by light may drive P2X2 channels to open probabilities similar to those achieved by ATP. The observation that light could activate the P2X2[K69A/P329] receptor indicates that endogenous ATP is not involved. However, it would be of interest to know whether the conformational change associated with light-induced channel opening nonetheless involves protein rearrangement at the ATP binding pocket. This might be studied by using a competitive antagonist, but the molecular mechanism of such compounds at P2X2 receptors is still poorly understood.

The approach was extended to P2X3 receptors with the equivalent mutation, P320C. The distinctive rapid desensitization was maintained in this construct irrespective of whether agonist or blue light was used for activation. Previous work has shown key roles for transmembrane and juxtamembrane cytosolic domains (31). Heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors are formed when both P2X3 and P2X2 subunits are both expressed together in primary afferent neurons. This heteromeric channel, when heterologously expressed, is formed by two P2X3 subunits and one P2X2 subunit (28). In accordance with this stoichiometry, the P2X3[P320C] subunit assembled to form light-gated heteromeric P2X2/3 receptors when coexpressed with wild-type P2X2 subunits. This displayed the slower desensitization that is characteristic for the heteromeric P2X2/3 receptor. The presence of two P2X3 subunits in the trimer would be consistent with our interpretation that the cis–trans conformational change between only two TM2s is sufficient for channel opening.

The structure of the ASIC1 indicates that G430 is also oriented toward the other G430 residues in adjacent subunits (14, 16). The observation of light-evoked currents indicates that the opening mechanism for ASICs and P2X receptors at the level of the transmembrane domains is functionally similar (18). We also observed light-evoked currents from mutation I428C, which is predicted to face away from the other I428C residues in adjacent subunits. This may be explained by differences between chick and human ASIC1 structures, but we cannot exclude the possibility that BMA may be bridging to an endogenous cysteines (e.g., C49, C59, C61, and C440) that are sufficiently close enough to I428C.

The expression of a nonnative light-gated protein (such as the channelrhodopsins) can address important questions about the cells and systems into which it is introduced. However, there are also advantages to control directly the activity of the native protein under investigation. First, the conjugated BMA is relatively stable in the trans isomer, so that the biological sample is illuminated only transiently. Second, the photoisomerizable conjugate can be tuned depending on the application; for example, by switching at longer wavelengths of light (32). Third, it is possible to exploit properties of the native channel, such as calcium permeability. Ion channels used currently as optogenetic tools show relatively lower calcium permeability [such as the calcium-permeable channelrhodopsin CatCh (33); PCa/PNa = 0.2] compared with the light-gated P2X2 receptor (PCa/PNa = 2.6).

The use of photoswitchable tethered ligands at P2X receptors would complement the optogenetic tool presented here. P2X receptors have previously been used for optogenetic studies of the Drosophila melanogaster nervous system using freely diffusible caged ATP (34), and attachment of an agonist at the P2X receptor binding site has also been achieved using cysteine-reactive 8-thiocyano-ATP (35, 36) or the photoaffinity agonist BzATP (37, 38). The presence of ATP in a photoswitchable ligand may increase the specificity for attachment in comparison with BMA, which is likely to react nondiscriminately with available extracellular cysteines (although most are disulfided in the extracellular oxidizing environment). Conversely, the tethered ATP molecule may be structurally constrained or prone to hydrolysis, and would thus become ineffective at activating the target P2X receptor. These potential issues are avoided in the present work, in which gating rather than agonist binding is under optical control. The bridging conjugate approach is also more versatile: it avoids the inherent difficulties of “tethering” a proton (in the case of ASICs). The approach could also be readily extended to other membrane proteins, such as stretch-activated or voltage-gated ion channels.

The detailed role of P2X receptors requires further study at several levels. These range from the subcellular [e.g., contractile vacuole of Dictyostelium (39) or fusion pore dilation in pneumocytes (40)] to the whole animal [e.g., demyelination (41)]. We expect that the development of an optically controlled P2X receptor will facilitate such studies.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of (E)-4,4′-Bis(maleimido)azobenzene.

To a solution of 4,4′-azodianiline (106 mg, 0.50 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (1 mL) was added maleic anhydride (103 mg, 1.05 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. To the resultant orange-colored solid was added dichloromethane (3 mL), and the mixture filtered through a Büchner funnel. The orange filter cake was washed with dichloromethane (20 mL) and dried under vacuum. The orange solid was suspended in acetic anhydride (2 mL), and to this mixture was added sodium acetate (106 mg, 1.29 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 45 min at 140 °C, during which time the suspended solid gradually dissolved. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, causing an orange precipitate. To the mixture was added water (10 mL), followed by aqueous 10% K2CO3 (10 mL), and the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (2 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine (10 mL), dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resultant crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica with dichloromethane/EtOAc (20:1 vol/vol) to afford (E)-4,4′-bis(maleimido)azobenzene as an orange solid (86 mg, 0.23 mmol, 43%) (42) with some water (12 mg or 13% by weight). The water content was reduced to 2.3 mg (2.7% by weight) by drying the isolated solid under high vacuum at 150 °C for 72 h.

Molecular and Cell Biology.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on P2X and ASIC subunits using the Stratagene QuikChange method. P2X2 receptor concatemers were generated as previously described (43), with minor changes in that the construct was engineered using NheI, ScaII, HindIII, and EcoRI (HindIII and EcoRI replacing NotI and ApaI, respectively). Each subunit has a different C terminus epitope tag (subunit 1, His; subunit 2, EYMPME; subunit 3, Flag), and linking residues between subunits 1 and 2 (-GRG-) and between subunits 2 and 3 (-GGRR-) were thus replaced by -PR- and -KL-, respectively. The constructs were confirmed by sequencing the whole construct using unique primers for each subunit. HEK 293 cells were maintained in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS (vol/vol) and 2 mM l-glutamine. CHO-K1 cells were maintained in RPMI with 10% FBS (vol/vol) and 2 mM l-glutamine. The cDNAs for wild-type and mutant P2X2 subunits (0.1–1 μg), P2X2 concatemers (1 μg), P2X3 subunits (1 μg), or ASIC1 subunits (0.1 μg) were transiently coexpressed together with GFP vector (0.05 μg) into HEK293 cells (for P2X receptors) or CHO-K1 cells (for ASIC1a: NP_001086.2) using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were seeded on borosilicate glass coverslips (Agar Scientific). PC12 cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% horse serum (vol/vol), 5% FBS (vol/vol), and 2 mM l-glutamine. PC12 cells were differentiated by plating them onto borosilicate glass coverslips (VWR) coated with collagen IV (Trevigen) and applying RPMI supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 100 ng/mL nerve growth factor-7S, from murine submaxillary gland. After 5–7 d, PC12 cells were transfected as for HEK293 cells, and recordings were made 48 h later. All cell lines were incubated at 37 °C/5% CO2. All media and reagents were purchased from Life Technologies, except where otherwise specified.

BMA Conjugation, Electrophysiology, and Light-Switching.

BMA was dissolved in DMSO to give a 1-mM stock solution: this was stored in the dark at room temperature for use within 48 h. Stock was diluted in the standard extracellular solution at 10 µM. Recordings were at room temperature. For whole-cell voltage clamp experiments, patch pipettes were pulled from thin-wall borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus): they had resistances of 2–4 MΩ when filled with (in mM): 147 NaCl, 10 EGTA, and 10 Hepes. Current–voltage relationships were obtained from voltage ramps (−60 mV to +60 mV in 500 ms). Permeability ratios were determined by measuring the reversal potentials first in an extracellular solution containing (in mM): 147 NaCl, 13 glucose, and 10 Hepes (adjusted to pH 7.3 using NaOH), and then in a solution containing (in mM) 110 CaCl2, 13 glucose, and 10 Hepes [adjusted to pH 7.3 using Ca(OH)2]. Reversal potentials were measured during voltage ramps (−20 to +20 mV in 500 ms). Currents elicited by protons were measured using an extracellular solution containing (in mM): 147 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Mes, and 13 glucose (pH 5.3 with NaOH). The holding potential was −60 mV for whole-cell recordings. For outside-out recordings, pipettes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments) and had resistance of 10–20 MΩ when filled with solution containing (in mM): 145 NaF, 10 Hepes, and 10 EGTA. The holding potential was −120 mV for single-channel recordings. Recordings of membrane potential PC-12 cells used pipettes (resistances 5–8 MΩ) filled with solution containing (in mM): 125 K gluconate, 15 KCl, 5 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, and 10 Hepes. The resting voltage was held at −60 mV. The standard extracellular solution contained (in mM): 147 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, and 13 glucose (pH 7.3, 285–315 mOsM). Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Illumination for light switching used a rapid wavelength-switching (<3 ms) xenon lamp monochromator (Polychrome IV, TILL Photonics) connected through the epifluorescence port of the microscope (Nikon TE200). Light was directed to a Fluor 40×/0.75 N.A. objective (Nikon) using a short-pass 532-nm edge filter in the exciter, and a 520-nm edge dichroic (Semrock), which also enabled the light to be switched off rapidly by switching to longer wavelengths. The monochromator was controlled using the EPC10 amplifier. Light illumination intensity was determined using an optical power meter (Newport).

Currents were recorded with an EPC10 amplifier using Patchmaster software (HEKA). The data were low-pass filtered at 3 kHz and sampled at 1 or 5 kHz unless stated otherwise. Agonists and other compounds were applied using an RSC-160 rapid perfusion system (Bio-Logic) and Perfusion Pencil (Digitimer). The RSC-160 was triggered by the EPC10 amplifier. Agonist concentrations were 100 μM ATP and 30 μM αβmeATP, unless stated otherwise.

Confocal Laser-Scanning Fluorescence Microscopy.

Fluorescent images were acquired using a Nikon laser-scanning C1 confocal microscope, using an Ar-ion 488-nm laser line with 515/30-nm emission filter. Photobleaching was <5% over the duration of experiments. YO-PRO-1 was used at 1 μM. Excitation for image acquisition was not carried out until after light switching had been carried out, so as not to isomerize the BMA. Light switching was carried out as described above. The C1 confocal, RSC-160, and monochromator were triggered using outputs of the EPC10 amplifier.

Molecular Models.

Closed and open molecular models of the rat P2X2 receptor were generated with MODELER 9.10 (44) using the zebrafish P2X4.1 crystal structures (Protein Data Bank accession nos. 4DW0 and 4DW1) as templates. MolProbity (45) was used to assess lowest-energy models, which were subsequently energy minimized using AMBER. The models showed 98.9% (closed model) and 97.4% (open model) of residues in the allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. The ASIC structures shown are the chick ASIC1 closed (3IJ4) and open (4FZ1) crystal structures. Protein images were produced using UCSF Chimera 1.62 (46).

Data Analysis.

Electrophysiological data were analyzed using FitMaster (HEKA), Axograph X (Molecular Devices), Kaleidograph 4 (Synergy), and Prism 4 (GraphPad) software. Dose–responses were fit with the Hill equation  , where [A] is the agonist concentration causing current I, EC50 is the agonist concentration causing half the maximal current Imax, and n is the Hill coefficient. Relative calcium permeabilities were calculated from the reversal potential of the ATP-evoked or light-evoked current (Erev, mV) from

, where [A] is the agonist concentration causing current I, EC50 is the agonist concentration causing half the maximal current Imax, and n is the Hill coefficient. Relative calcium permeabilities were calculated from the reversal potential of the ATP-evoked or light-evoked current (Erev, mV) from  where

where  , and x = ErevF/RT (F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature). Amplitudes of single-channel currents were measured by all-points amplitude histograms fit to two Gaussian distributions. Fluorescent images were analyzed using EZ-C1 Viewer (Nikon) and were low-pass filtered with a 3 × 3 pixel median filter using ImageJ. Pooled data are given as the mean ± SEM. Tests for statistical significance were performed using nonparametric ANOVA.

, and x = ErevF/RT (F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature). Amplitudes of single-channel currents were measured by all-points amplitude histograms fit to two Gaussian distributions. Fluorescent images were analyzed using EZ-C1 Viewer (Nikon) and were low-pass filtered with a 3 × 3 pixel median filter using ImageJ. Pooled data are given as the mean ± SEM. Tests for statistical significance were performed using nonparametric ANOVA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rosemary Gaskell for tissue culture. The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (093140/Z/10/Z) and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/J010448).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1318582111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442(7102):527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khakh BS, North RA. Neuromodulation by extracellular ATP and P2X receptors in the CNS. Neuron. 2012;76(1):51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surprenant A, North RA. Signaling at purinergic P2X receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishtal OA, Pidoplichko VI. A receptor for protons in the nerve cell membrane. Neuroscience. 1980;5(12):2325–2327. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wemmie JA, Taugher RJ, Kreple CJ. Acid-sensing ion channels in pain and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(7):461–471. doi: 10.1038/nrn3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tochitsky I, et al. Optochemical control of genetically engineered neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat Chem. 2012;4(2):105–111. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volgraf M, et al. Allosteric control of an ionotropic glutamate receptor with an optical switch. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(1):47–52. doi: 10.1038/nchembio756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Numano R, et al. Nanosculpting reversed wavelength sensitivity into a photoswitchable iGluR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(16):6814–6819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811899106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolley GA. Photocontrolling peptide alpha helices. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38(6):486–493. doi: 10.1021/ar040091v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorostiza P, Isacoff EY. Optical switches and triggers for the manipulation of ion channels and pores. Mol Biosyst. 2007;3(10):686–704. doi: 10.1039/b710287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beharry AA, Woolley GA. Azobenzene photoswitches for biomolecules. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40(8):4422–4437. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15023e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawate T, Michel JC, Birdsong WT, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of the ATP-gated P2X(4) ion channel in the closed state. Nature. 2009;460(7255):592–598. doi: 10.1038/nature08198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattori M, Gouaux E. Molecular mechanism of ATP binding and ion channel activation in P2X receptors. Nature. 2012;485(7397):207–212. doi: 10.1038/nature11010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales EB, Gouaux E. Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 A resolution and low pH. Nature. 2007;449(7160):316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature06163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzales EB, Kawate T, Gouaux E. Pore architecture and ion sites in acid-sensing ion channels and P2X receptors. Nature. 2009;460(7255):599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature08218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baconguis I, Gouaux E. Structural plasticity and dynamic selectivity of acid-sensing ion channel-spider toxin complexes. Nature. 2012;489(7416):400–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rassendren F, Buell G, Newbolt A, North RA, Surprenant A. Identification of amino acid residues contributing to the pore of a P2X receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16(12):3446–3454. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baconguis I, Hattori M, Gouaux E. Unanticipated parallels in architecture and mechanism between ATP-gated P2X receptors and acid sensing ion channels. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23(2):277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brake AJ, Wagenbach MJ, Julius D. New structural motif for ligand-gated ion channels defined by an ionotropic ATP receptor. Nature. 1994;371(6497):519–523. doi: 10.1038/371519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(4):1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang LH, Rassendren F, Surprenant A, North RA. Identification of amino acid residues contributing to the ATP-binding site of a purinergic P2X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(44):34190–34196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujiwara Y, Kubo Y. Density-dependent changes of the pore properties of the P2X2 receptor channel. J Physiol. 2004;558(Pt 1):31–43. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valera S, et al. A new class of ligand-gated ion channel defined by P2x receptor for extracellular ATP. Nature. 1994;371(6497):516–519. doi: 10.1038/371516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans RJ, et al. Ionic permeability of, and divalent cation effects on, two ATP-gated cation channels (P2X receptors) expressed in mammalian cells. J Physiol. 1996;497(Pt 2):413–422. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browne LE, Compan V, Bragg L, North RA. P2X7 receptor channels allow direct permeation of nanometer-sized dyes. J Neurosci. 2013;33(8):3557–3566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2235-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stelmashenko O, Lalo U, Yang Y, Bragg L, North RA, Compan V. Activation of trimeric P2X2 receptors by fewer than three ATP molecules. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82(4):760–766. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis C, et al. Coexpression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits can account for ATP-gated currents in sensory neurons. Nature. 1995;377(6548):432–435. doi: 10.1038/377432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang LH, et al. Subunit arrangement in P2X receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23(26):8903–8910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08903.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakazawa K, Fujimori K, Takanaka A, Inoue K. An ATP-activated conductance in pheochromocytoma cells and its suppression by extracellular calcium. J Physiol. 1990;428:257–272. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding S, Sachs F. Single channel properties of P2X2 purinoceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113(5):695–720. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner P, Seward EP, Buell GN, North RA. Domains of P2X receptors involved in desensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(26):15485–15490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samanta S, Beharry AA, Sadovski O, McCormick TM, Babalhavaeji A, Tropepe V, Woolley GA. Photoswitching azo compounds in vivo with red light. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9777–9784. doi: 10.1021/ja402220t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinlogel S, et al. Ultra light-sensitive and fast neuronal activation with the Ca²+-permeable channelrhodopsin CatCh. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(4):513–518. doi: 10.1038/nn.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lima SQ, Miesenböck G. Remote control of behavior through genetically targeted photostimulation of neurons. Cell. 2005;121(1):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang R, et al. Agonist trapped in ATP-binding sites of the P2X2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(22):9066–9071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102170108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang R, Taly A, Lemoine D, Martz A, Specht A, Grutter T. Intermediate closed channel state(s) precede(s) activation in the ATP-gated P2X2 receptor. Channels. 2012;6(5):398–402. doi: 10.4161/chan.21520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhargava Y, Rettinger J, Mourot A. Allosteric nature of P2X receptor activation probed by photoaffinity labelling. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(6):1301–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browne LE, North RA. P2X receptor intermediate activation states have altered nucleotide selectivity. J Neurosci. 2013;33(37):14801–14808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2022-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fountain SJ, et al. An intracellular P2X receptor required for osmoregulation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2007;448(7150):200–203. doi: 10.1038/nature05926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miklavc P, et al. Fusion-activated Ca2+ entry via vesicular P2X4 receptors promotes fusion pore opening and exocytotic content release in pneumocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(35):14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101039108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matute C, et al. P2X(7) receptor blockade prevents ATP excitotoxicity in oligodendrocytes and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci. 2007;27(35):9525–9533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0579-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamenjicki M, Asher SA. Photochemically controlled cross-linking in polymerized crystalline colloidal array photonic crystals. Macromolecules. 2004;37:8293–8296. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Browne LE, et al. P2X receptor channels show threefold symmetry in ionic charge selectivity and unitary conductance. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(1):17–18. doi: 10.1038/nn.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234(3):779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis IW, et al. MolProbity: All-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W375–83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.