Significance

Human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and HHV-6B are prevalent viruses causing mild up to grave lethal diseases. Viruses modulate cell-cycle progression so as to use cellular replication machinery. The retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor protein represses the E2F1 transcription factor. This induces entry to the S phase, enabling efficient replication. Viruses employ different mechanisms modulating the Rb–E2F1 pathway. However, the mechanism(s) used by HHV-6 are unknown. We have found that HHV-6A infection induced Rb degradation while producing elevated levels of active E2F1 and DP1. Surprisingly, several cellular E2F target genes were not up-regulated, whereas active E2F1 was used to transcribe selected viral genes containing the E2F binding site in their promoters. These viral genes play significant roles in viral DNA synthesis.

Abstract

E2F transcription factors play pivotal roles in controlling the expression of genes involved in cell-cycle progression. Different viruses affect E2F1/retinoblastoma (Rb) interactions by diverse mechanisms releasing E2F1 from its suppressor Rb, enabling viral replication. We show that in T cells infected with human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A), the E2F1 protein and its cofactor DP1 increased, whereas the Rb protein underwent massive degradation without hyperphosphorylation at three sites known to control E2F/Rb association. Although E2F1 and DP1 increased without Rb suppression, the E2F1 target genes—including cyclin A, cyclin E, and dihydrofolate reductase—were not up-regulated. To test whether the E2F1/DP1 complexes were used for viral transcription, we scanned the viral genome for genes containing the E2F binding site in their promoters. In the present work, we concentrated on the U27 and U79 genes known to act in viral DNA synthesis. We constructed amplicon-6 vectors containing a GFP reporter gene driven by WT viral promoter or by promoter mutated in the E2F binding site. We found that the expression of the fusion U27 promoter was dependent on the presence of the E2F binding site. Test of the WT U79 promoter yielded >10-fold higher expression of the GFP reporter gene than the mutant U79 promoter with abrogated E2F binding site. Moreover, by using siRNA to E2F1, we found that E2F1 was essential for the activity of the U79 promoter. These findings revealed a unique pathway in HHV-6 replication: The virus causes Rb degradation and uses the increased E2F1 and DP1 factors to transcribe viral genes.

Human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and HHV-6B infect >90% of children by the age of 2 y (1). Recent studies have found that ∼1% of children are born with chromosomally integrated HHV-6, suggesting that the virus is vertically transmitted in a Mendelian manner (2). HHV-6B is the causative agent of roseola infantum, a brief febrile infection with skin rash (3). In a minority of patients, there are neurological complications up to lethal encephalitis (4). After productive infection, HHV-6B enters into latency from which it can be reactivated—e.g., following bone marrow and hematopoietic stem cell transplantations. Viral reactivation can result in delayed transplant engraftment and severe complications up to lethal encephalitis (5). Furthermore, transplantation of solid organs—including kidney, liver, lung, and heart—results in high rates of HHV-6 reactivation, although only 1% of transplant recipients were found to develop severe complications (6). There is no acute disease known to be caused by HHV-6A, but recent studies have suggested potential involvement in multiple sclerosis (MS) aggravation (7). HHV-6 was found more often in MS plaques than in MS normal-appearing white matter or non-MS brains. HHV-6 reactivation has been reported during MS clinical relapses (7). Recent evidence (8) has suggested the association of HHV-6A with Hashimoto thyroiditis, the most common of all thyroid diseases.

E2F1 acts as a transcription factor of genes involved in cell-cycle progression, DNA replication, DNA repair and apoptosis (9, 10). The heterodimerization of E2F1 and its cofactor DP1 is essential for binding to promoters that carry the E2F binding site (10). E2F1 activity is regulated by the tumor suppressor retinoblastoma (Rb) protein. The binding of hypophosphorylated Rb to E2F1 leads to inhibition of E2F1 transcription activity and cell-growth arrest. In the G1 phase, Rb protein is inactivated following its phosphorylation by cyclin D/CDK-4/6 and cyclin E/CDK-2 complexes, resulting in its dissociation from E2F1/DP1 heterodimer and cellular entry into the S phase (11, 12). In mid-late S phase, the cyclin A/CDK-2 complex phosphorylates E2F1/DP1 complex, reducing their DNA binding capacity (10, 11). The E2F1/Rb interactions were found to be targeted by different viruses, including the adenovirus oncoprotein E1A, the papillomavirus E7 protein, and the SV40 large T antigen (13, 14). These viral proteins disassemble the E2F1/Rb complexes, resulting in the release of E2F1. A number of human herpesviruses also target the Rb protein (15). It has been shown that human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) tegument protein pp71 induces Rb degradation (16) and that HCMV kinase protein UL97 phosphorylates Rb protein (17). We have shown (18) that the infection of SupT1 T cells with HHV-6A was associated with cell-cycle arrest at the G2/M phase. Such arrest might be advantageous for viral replication and the production of the typical HHV-6 cytopathic effect, consisting of multiple fused infected cells. To test the mechanism(s) by which HHV-6A manipulates the cell cycle, we analyzed alterations of the E2F1/Rb pathway known to be a checkpoint in the control of cell-cycle progression. We describe a unique strategy used by HHV-6A inducing the degradation of Rb, so as to exploit the released E2F1 transcription factor to transcribe selected cellular genes as well as viral genes containing E2F binding site in their promoters.

Results

HHV-6A Infection Leads to Rb Degradation.

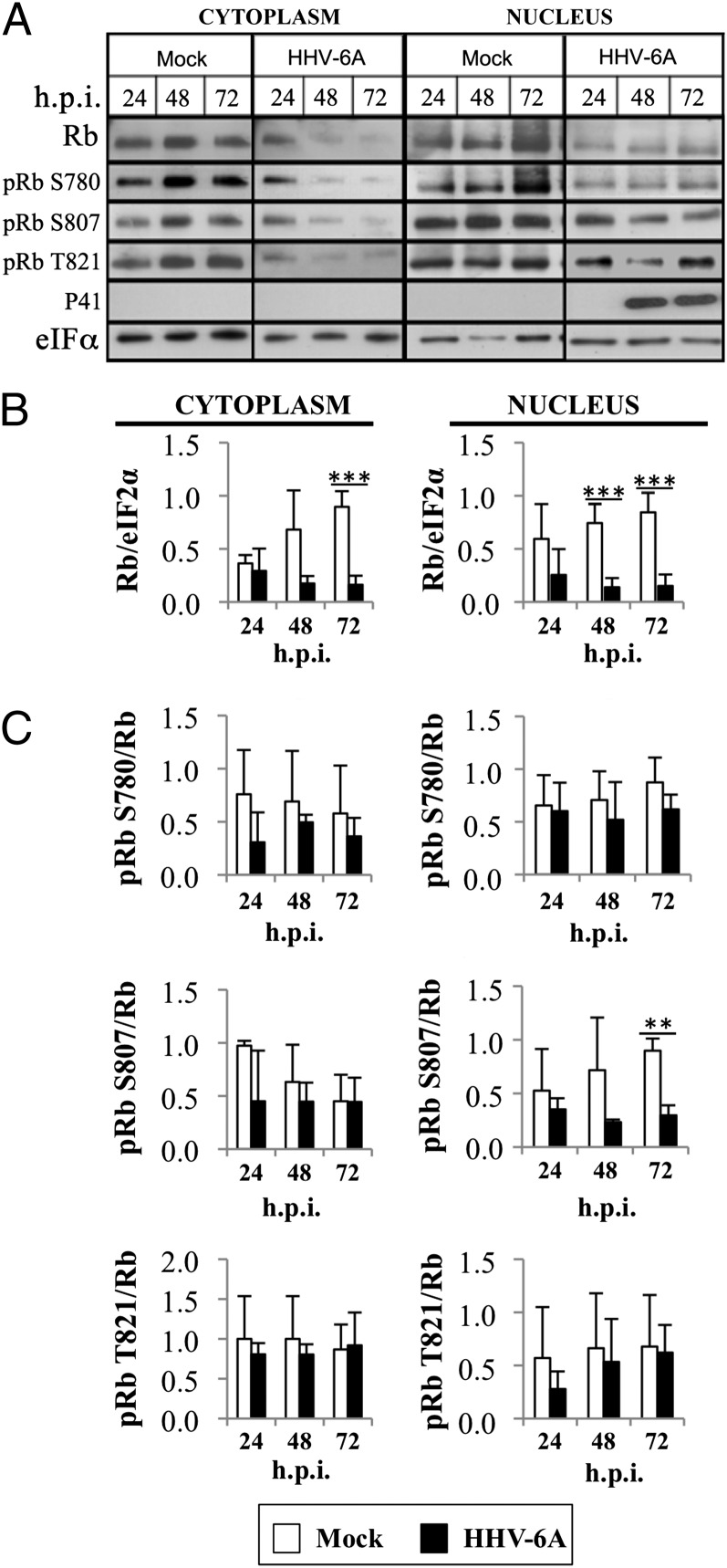

During lytic infection, herpesviruses synthesize viral DNA by using viral or cellular reagents required for nucleotide metabolism and DNA replication. Cellular enzymes are encoded by E2F1-target genes. These genes are negatively regulated by Rb protein, a major target for the intervention of herpesviruses in the cell cycle (15). Disruption of the E2F1/Rb complexes by phosphorylation and/or Rb degradation can induce entry into the S phase, enhancing viral replication. There are 13 Ser/Thr sites potentially phosphorylated in Rb during G1/S transition. Accumulation of multiple phosphorylated Rb residues can result in the disruption of E2F1/Rb complexes (19). We tested Rb phosphorylation at residues Ser-780, Ser-807, and Thr-821 because they represent consensus sites known to be phosphorylated during E2F1/Rb disassembly. SupT1 T cells were mock infected or infected with two tissue culture infectious dosage for infecting 50% of the cells (TCID50) per cell. Protein samples were prepared from the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection (h.p.i.). Blots were reacted with antibodies to total Rb; phosphorylated Rb at amino acids S780, S807/811, T821; and the eIF2α, as loading control. The progression of infection was tested by accumulation of the P41 protein reactive with 9A5 monoclonal antibody (20, 21).

The results revealed (Fig. 1 A and B) that in the infected cells, the Rb levels were significantly decreased (P ≤ 0.001). Rb degradation was found at 48 and 72 h.p.i., as seen in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Tests of Rb phosphorylation at three sites revealed no significant alterations in the phosphorylation level of these residues (Fig. 1 A and C). Thus, HHV-6A infection led to dramatic Rb degradation without Rb phosphorylation.

Fig. 1.

Regulation of Rb and phosphorylated Rb during the HHV-6A infection. (A) Western blots of cytoplasmic (Left) and nuclear (Right) lysates of mock-infected and HHV-6A–infected SupT1 T cells tested with antibodies to Rb; phosphorylated Rb at amino acids S780, S807, and T821; HHV-6 P41; and eIF2α as a loading control. (B) Graphic representation of the Rb/eIF2a results relative to the highest level of Rb/eIF2α in the cytoplasmic (Left) and nuclear (Right) fractions. Results are shown as mean ± SD, based on three independent experiments for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. The differences in Rb levels in the mock-infected vs. HHV-6–infected cells were statistically significant as determined by t tests. ***P ≤ 0.001. (C) Graphic representation of the phosphorylation levels of pRbS780/Rb, pRbS807/Rb, and pRbT821/Rb in the cytoplasmic (Left) and nuclear (Right) fractions. In each case, the results are calculated based on mean ± SD from three independent experiments. The results are displayed relative to the highest level of phosphorylated Rb in the nuclear fraction. **P ≤ 0.01.

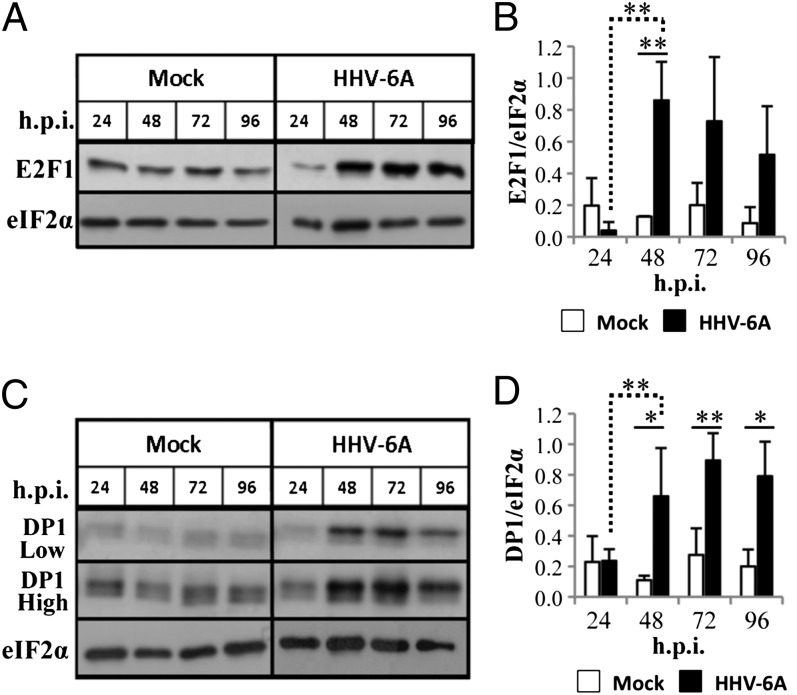

The E2F1 and Its Cofactor DP1 Are Elevated During HHV-6A Infection.

Heterodimers of E2F and DP family members are used in gene expression of E2F target genes. This complex reduces the repression by the Rb protein family members (22). The release of E2F1 induces its own expression as well as its cofactor DP1. To test whether Rb degradation induced E2F1 and DP1 expression, nuclear protein lysates from mock-infected cells or infected cells were prepared (Fig. 2) and were analyzed in Western blots, by using the E2F1 and DP1 antibodies. The eIF2α antibody served as loading control. Whereas in the mock infection the E2F1 level was low and steady, there was a significant increase in E2F1 expression, starting from 48 until 96 h.p.i. A similar increase was found in the DP1 protein expression. The coordinated increase in E2F1 and DP1 proteins coincided with Rb degradation and E2F1 release.

Fig. 2.

E2F1 and DP1 expression during HHV-6A infection. (A) Western blots of nuclear protein lysates reacted with antibodies to E2F1 and eIF2α. (B) Graphic representation of the results relative to the highest level of E2F1/eIF2α in the nuclear fraction. (C) Western blots of nuclear protein lysates reacted with antibodies to DP1 and eIF2α. Two exposures of the blots (low and high) are shown for the DP1 protein. (D) Graphic representation of the results relative to the highest level of DP1/eIF2α in the nuclear fraction. Results are indicated as mean ± SD based on three independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

In HHV-6A Infection, There Was No Induction of Expression of E2F1 Target Genes.

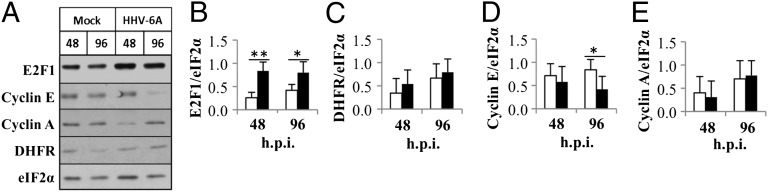

E2F1 in association with DP1 function as sequence-specific transcriptional activators of genes involved in cell proliferation (10). Because HHV-6A infection induced elevation of free E2F1, we tested the expression of the target genes cyclin A, cyclin E, and Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). Protein lysates of mock-infected or HHV-6A–infected cells were prepared at 48 and 96 h.p.i. Test with antibodies to E2F1, cyclin A, cyclin E, DHFR, and eIF2α (Fig. 3) revealed the following: (i) There was increased E2F1 protein, confirming the earlier results; (ii) there was no up-regulation of cyclin A and DHFR; and (iii) cyclin E was found to be decreased at 96 h.p.i. Thus, during HHV-6A infection, there was no up-regulation of genes involved in S-phase progression, regardless of the induction of E2F1.

Fig. 3.

Expression of E2F1 and E2F1 target genes. (A) Western blots of proteins of mock-infected and HHV-6A–infected cell lysates reacted with antibodies to E2F1 cyclin E, cyclin A, DHFR, and eIF2α. (B–E) Graphic representation of the results compared with the highest level of protein/eIF2α. The results are presented as mean ± SD based on four independent experiments for E2F1 and the E2F1 target genes. E2F1 increased significantly at 48 and 96 h.p.i. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

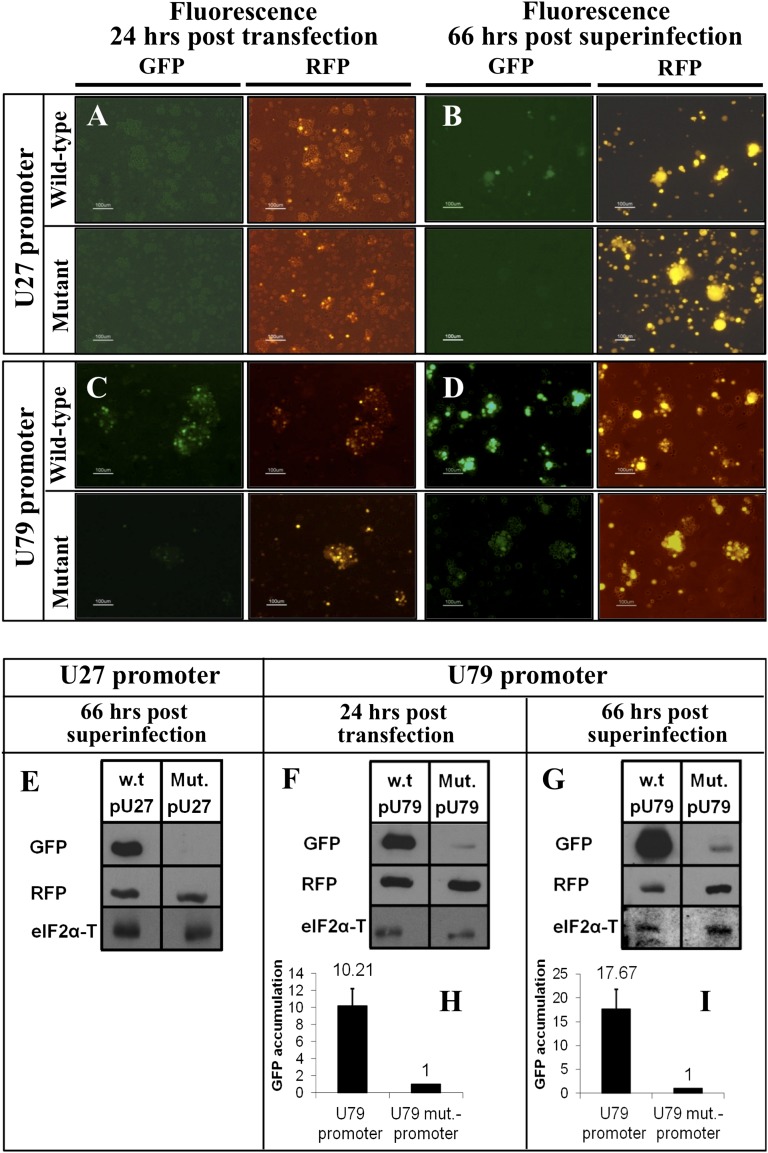

Viral Transcription Was Affected by the E2F Binding Site.

Because the E2F1-responsive genes cyclin A, cyclin E, and DHFR were not up-regulated, it was of interest to test whether the free E2F1 was used to transcribe viral genes. We scanned the HHV-6A genome for the consensus E2F binding site TTTSSCGC, where S is either a G or a C. Several viral genes were found to have promoters with E2F binding site, including the following: (i) U18, a transcription regulatory gene, part of the IE-B/E genes; (ii) U33, a viral tegument protein, found to be a critical mediator of metabolic stress; (iii) U52, which promotes the accumulation of late transcripts, E gene; and (iv) U74, part of the helicase/primase complex, E gene. In the present work, we have focused on the U27 and the U79 genes, both functioning in viral DNA synthesis. The U27 gene encodes the P41 viral DNA polymerase processivity factor (23). The U79–80 early gene encodes a family of nuclear proteins possessing common amino acid termini and is generated by different alternative splicing. They were found to be essential for viral DNA replication (24) and colocalize with components of the viral DNA replication machinery.

To test whether E2F1 is used in the expression of U27 and U79 genes, we placed the promoters as well as site-specific mutations of the E2F binding site within the amplicon-6-GFP vector (pNF1194) containing the viral oriLyt, the pac-1–pac-2 packaging signals, and the transgene GFP driven by the HCMV promoter (25). The primer sequences are listed in Table S1. We replaced the HCMV promoter with the U27 or the U79 promoters containing the WT E2F binding site TTTGCCGC, as well as a mutant sequence TGTGGATC. To monitor transfection efficiency, RFP driven by the HCMV promoter was also placed in the vectors. The new plasmids (Fig. S1) were designated as amplicon-6-U27-promoter-GFP-RFP; amplicon-6-mutant-U27-promoter-GFP-RFP; amplicon-6-U79-promoter-GFP-RFP; and amplicon-6-mutant-U79-promoter-GFP-RFP. Parallel 2 × 106 SupT1 T-cell cultures were transfected with the amplicon plasmids. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were monitored for GFP and red fluorescent protein (RFP) fluorescence (Fig. 4). Aliquots of the cultures were used to prepare protein lysates, whereas additional aliquots were superinfected with 2 TCID50 per cell of HHV-6A. At 66 h post-superinfection, fluorescence images were obtained and protein lysates were tested in Western blots, by using antibodies to GFP, RFP, and eIF2α protein. The results have shown the following: (i) The RFP expression was detected in all cultures, demonstrating the successful transfection (Fig. 4 A–D); (ii) GFP expression was not detected in cultures that were solely transfected with the U27 WT or mutant promoters (Fig. 4A); (iii) superinfection with HHV-6A led to GFP expression in cultures that were transfected with the WT promoter, but not in cultures receiving the mutant U27 promoter (Fig. 4 A, B, and E); (iv) GFP fluorescence was observed in the cultures which were transfected with U79 WT or mutant promoters (Fig. 4C); in cultures that received the WT U79 promoter, there was 10-fold higher GFP expression than in the cultures that received the mutant promoter (Fig. 4F); and (v) superinfection with HHV-6A led to a stronger expression of GFP in cultures transfected with WT U79 promoter (Fig. 4 D, H, and I). Moreover, there was ∼17-fold higher GFP expression in the cultures that were transfected with the WT promoter compared with cultures transfected with the mutant promoter (Fig. 4I). All together, these results reveal a previously undescribed role of E2F binding site in the regulation of HHV-6 gene expression.

Fig. 4.

Viral promoters are regulated by the E2F binding site. (A–D) GFP and RFP fluorescence at 24 h after transfection (A and C) and 66 h after superinfection (B and D) with HHV-6A. Transfections were done with amplicon-6-U27-promoter-GFP-RFP (U27 promoter), amplicon-6-mutant-U27-promoter-GFP-RFP (mutant U27 promoter), amplicon-6-U79-promoter-GFP-RFP (U79 promoter), and amplicon-6-mutant-U79-promoter-GFP-RFP (mutant U79 promoter). At 24 h after transfection and at 66 h after superinfection, RFP expression was viewed in the microscope to estimate efficiency of transfection. GFP expression was viewed in the microscope to estimate promoter strength. (E) Western blots of cultures that were transfected with U27 WT or mutant promoters were followed by 66 h after superinfection with HHV-6A. The blot was tested by using GFP, RPF, and eIF2a antibodies. GFP expression at 24 h after transfection with amplicon-6-U27 WT or mutant promoters was not detected. The results are based on three experiments. (F and G) Western blots of cultures that were transfected with the WT U79 promoter or the mutant U79 promoter for 24 h (F) as well as these cultures following HHV-6A superinfected for 66 h (G). (H and I) Graphic representation of the GFP expression in cells transfected with the WT or mutant U79 promoters at 24 h after transfection (H) or 66 h after superinfection (I). GFP accumulation was divided by RFP accumulation to correct for transfection efficiency and by eIF2α as a loading control. Results are shown as mean ± SD based on three experiments.

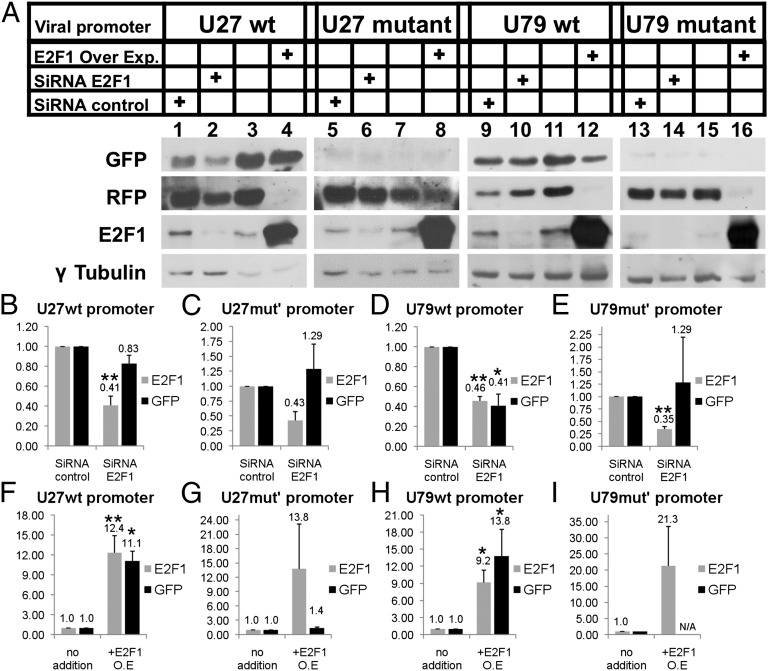

The E2F1 Transcription Factor Regulates Viral Transcription as Shown by siRNA and Overexpression Treatments.

The involvement of the E2F1 transcription factor in viral transcription was tested by altering the E2F1 levels in the cells using siRNA as well as E2F1 overexpression. Parallel six-well cultures of 293T cultures were transfected with the following: amplicon-6-U27-promoter-GFP-RFP (U27 WT), amplicon-6-mutant-U27-promoter-GFP-RFP (U27 mutant), amplicon-6-U79-promoter-GFP-RFP (U79 WT), and amplicon-6-U79 mutant-promoter-GFP-RFP (U79 mutant). Each culture was transfected with 2 µg of the promoter plasmid solely or cotransfected with one of following: 10 nM negative control siRNA, 10 nM siRNA to E2F1, or 2 µg of E2F1 overexpression plasmid. At 48 h.p.i., the cells were extracted, and the E2F1 and γ-tubulin were measured. The expression of GFP was normalized to RFP expression to correct for transfection efficiency, as well as to γ-tubulin protein to correct for gel protein loading. The experiments were repeated three times. The results showed the following: (i) siRNA against E2F1 led to >50% reduction in the E2F1 (Fig. 5 A, lanes 2, 6, 10, and 14; and B–E) compared with the siRNA control; (ii) the decreased E2F1 caused a mild decrease in the activity of U27 WT promoter and sharp decrease in the activity of U79 WT promoter (Fig. 5 A, lanes 2 and 10; B; and D); (iii) the promoters of U27 and U79 mutants showed no significant difference in their activity (Fig. 5 A, lanes 6 and 14; C; and E); (iv) moreover, the mutant promoters showed very weak GFP expression in comparison with the WT promoters; and (v) overexpression of E2F1 induced >10-fold GFP expression (P < 0.05) by using the WT promoters (Fig. 5 A, lanes 4 and 12; F; and H). However, this effect was barely visible, with only mild increase, using the U27 mutant promoter (Fig. 5 A, lane 4; and G). The GFP expression of the U79 mutant promoter could not be detected (Fig. 5 A, lane 16; and I).

Fig. 5.

E2F1 is involved in viral transcription. The 293T cells were transfected with viral promoters including U27 WT, U27 mutant, U79 WT, and the U79 mutant. The cells were treated several folds: siRNA control, siRNA to E2F1, and E2F1 overexpression vector. The cellular proteins were prepared from the cultures at 48 h.p.i. (A) Western blots of cultures that were reacted with antibodies to GFP, RFP, E2F1, and γ-tubulin. (B–E) Graphic representation of the GFP expression in cells transfected with the viral promoters U27 WT (B), U27 mutant (C), U79 WT (D), and the U79 mutant (E) and cotransfected with siRNA control or siRNA to E2F1. GFP expression (promoter activity) was divided by RFP expression to correct for the efficiency of transfection and by γ-tubulin as a loading control. (F–I) Graphic representation of the E2F1 expression in cells transfected with viral promoters U27 WT (F), U27 mutant (G), U79 WT (H), and the U79 mutant (I) or cotransfected with E2F1 expression vector (O.E). E2F1 expression was divided by γ-tubulin as a loading control. Results are shown as mean ± SD based on three experiments. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

In analyzing the ability of HHV-6A to modulate the E2F/Rb pathway, we found massive degradation of the Rb protein and no phosphorylation of residues Ser-780, Ser-807, or Thr-821. In uninfected cells in late G1 phase the heterodimers of E2F1 and DP1 proteins were reported to be up-regulated, stimulating E2F1-dependent transcription and entry into the S phase (26). Both HHV-6A and -6B infections were reported to induce cell-cycle arrest at the G2/M phase during the first 48 h.p.i. (18, 27). As shown here in HHV-6A infection of SupT1 T cells, there was pronounced up-regulation of E2F1 and DP1 proteins by 48 h.p.i. Increased E2F1 expression was also described by using a microarray assay of HHV-6B–infected adult T-cell leukemia cell line (28). Although E2F1 and DP1 levels were elevated, we found that cyclin A and DHFR were not up-regulated, and cyclin E decreased at 96 h.p.i. Our results differ from the results of De Bolle et al., who found that late post–HHV-6A infection of human cord blood mononuclear cells there was increased accumulation of cyclin A without up-regulation of cyclin E (27). Hence, the expression of E2F1 target genes during HHV-6A infection might vary depending on the cells or tissues used.

To test the potential utilization of E2F1 in the transcription of viral genes, we scanned the viral genome for E2F binding sites. We chose the U27 early (β) gene encoding the p41 DNA polymerase processivity factor and the U79 immediate early (α) gene also active in viral DNA synthesis. DNA polymerase processivity factors were found to be essential for the replication of several herpesviruses. The HSV-1 mutant of UL42 DNA polymerase processivity factor was found to be defective in viral replication (29, 30). The HCMV UL44 gene encoding the ICP36 processivity factor is homologous to the HSV-1 UL42 gene and to the HHV-6 U27. By its association with viral DNA polymerase, it stimulates viral replication (31). We now show that a GFP reporter gene is expressed if it is linked to the WT U27 promoter with an intact E2F binding site. A three-nucleotide mutation in the E2F1 binding site abolished the activation of the promoter. However, no expression of GFP was noted in cells transfected with WT U27 promoter in absence of superinfecting virus, indicating potential participation of additional viral protein(s) in mediating activation of the U27 promoter. Moreover, whereas the treatment of the cells with siRNA to E2F1 resulted in mild decrease in the promoter activity, the overexpression of E2F1 led to a substantial increase of the promoter activity. This result indicates that other E2F factors may play a role in the induction of U27 promoter.

The mRNA transcripts of the U79 gene were found to encode immediate early nuclear proteins playing a role in viral DNA synthesis (24). We have found a strong activity of the U79 promoter even in the absence of additional viral factors. This activity depended on the intactness of the E2F binding site because mutation of the site led to 90% reduced activity. The involvement of E2F1 in U79 promoter activity was found by using siRNA and overexpression of E2F1. This finding indicates that E2F1 is a major factor in U79 expression.

The involvement of E2F1 in transcription of the U27 and the U79, β, and α genes, respectively, is a previously undescribed outlook of the regulation of HHV-6 gene expression. It is of interest for several reasons: First, ∼30% of cellular genes contain promoters with E2F1 binding site. Analyses of ∼24,000 promoters revealed that >20% of the promoters were bound by E2F1. These results place the E2F1 as a factor that contributes to the regulation of a large fraction of human genes (32). Second, a functional distinction between the various E2F1 binding sites could be caused by their association with different protein complexes (33). The cellular E2F1 target genes were found to be manipulated during the infection: Whereas E2F1 and DP1 were specifically induced, there was no up-regulation of cyclin A, cyclin E, and DHFR expression. Hence, a possible mechanism for the utilization of E2F1 transcription factor in viral replication might involve viral protein(s) recruiting the E2F1 and directing it to viral promoter(s) or selected cellular promoters. Examples for such processes include the E2 adenovirus promoter that is activated by an E2F1/E4 complex (34). In addition, the bovine herpes virus 1 infection leads to increased E2F1 protein levels, and the activity of the bovine ICP0 early promoter is increased dramatically by E2F1 (35).

Materials and Methods

Cells and Viruses.

SupT1 CD4+ human T cells were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research Repository. The SupT1 Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640, 10% (vol/vol) FCS, and gentamycin (25 µg/mL). The 293T cells were propagated in DMEM, 10% (vol/vol) FCS, and gentamycin (25 µg/mL). The HHV-6A (U1102) was obtained from Robert Honess (National Institute for Medical Research, London). Virus stocks were prepared from virus secreted into the medium and concentrated by centrifugation at 65,000 × g for 2.15 h (4 °C). Titers were determined by using the endpoint assay, estimating the TCID50 per milliliter.

Plasmids.

The details on plasmids are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Transfection.

A total of 2 × 106 cells were transfected with 13 μg of the test plasmid, by using microporator MP1000 (Bio Digital). The efficiency of transfection was determined by RFP expression. The 293T cells were transfected by calcium phosphate.

siRNA Transfection.

The siRNA duplexes were inserted by the calcium phosphate method. The negative control duplex corresponds to a scrambled sequence that is absent in the human genome. The duplexes were purchased from IDT (TriFECTa Dicer-Substrate RNAi kit).

Fluorescence and Light Microscopy.

Fluorescence microscopy was performed by using the Nikon Eclipse TE200-S microscope with ACT-1 software.

Western Blotting.

Protein extracts were prepared as described (18). The antibodies used in Western blotting are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bala Chandran (Rosalind Franklin University) for the gift of the 9A5 antibody recognizing the HHV-6 P41 protein. The E2E1 expression plasmid was kindly gifted by Dr. Yoel Kloog (Tel Aviv University). We thank the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Division of AIDS) for the SupT1T cells from James Howxie. This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation; the S. Daniel Abraham Institute for Molecular Virology; and the S. Daniel Abraham Chair for Molecular Virology and Gene Therapy, Tel Aviv University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1308854110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1. Yamanishi K, Mori Y, Pellett PE (2007) Human herpesviruses 6 and 7. Fields Virology, eds Knipe DM, Howley PM (Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia), 5th Ed, Vol 2, pp 2819–2845.

- 2.Gravel A, Hall CB, Flamand L. Sequence analysis of transplacentally acquired human herpesvirus 6 DNA is consistent with transmission of a chromosomally integrated reactivated virus. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(10):1585–1589. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamanishi K, et al. Identification of human herpesvirus-6 as a causal agent for exanthem subitum. Lancet. 1988;1(8594):1065–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michael BD, Solomon T. Seizures and encephalitis: Clinical features, management, and potential pathophysiologic mechanisms. Epilepsia. 2012;53(Suppl 4):63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerr DM, et al. HHV-6 reactivation and associated sequelae after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(11):1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lautenschlager I, Razonable RR. Human herpesvirus-6 infections in kidney, liver, lung, and heart transplantation: Review. Transpl Int. 2012;25(5):493–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virtanen JO, Jacobson S. Viruses and multiple sclerosis. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2012;11(5):528–544. doi: 10.2174/187152712801661220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caselli E, et al. Virologic and immunologic evidence supporting an association between HHV-6 and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(10):e1002951. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polager S, Ginsberg D. p53 and E2f: Partners in life and death. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(10):738–748. doi: 10.1038/nrc2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong JV, Dong P, Nevins JR, Mathey-Prevot B, You L. Network calisthenics: Control of E2F dynamics in cell cycle entry. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(18):3086–3094. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.18.17350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mundle SD, Saberwal G. Evolving intricacies and implications of E2F1 regulation. FASEB J. 2003;17(6):569–574. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0431rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh S, Johnson J, Chellappan S. Small molecule regulators of Rb-E2F pathway as modulators of transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799(10-12):788–794. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helt AM, Galloway DA. Mechanisms by which DNA tumor virus oncoproteins target the Rb family of pocket proteins. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24(2):159–169. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felsani A, Mileo AM, Paggi MG. Retinoblastoma family proteins as key targets of the small DNA virus oncoproteins. Oncogene. 2006;25(38):5277–5285. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hume AJ, Kalejta RF. Regulation of the retinoblastoma proteins by the human herpesviruses. Cell Div. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalejta RF, Shenk T. Proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of the Rb family of tumor suppressors by the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(6):3263–3268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hume AJ, et al. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein by viral protein with cyclin-dependent kinase function. Science. 2008;320(5877):797–799. doi: 10.1126/science.1152095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mlechkovich G, Frenkel N. Human herpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and HHV-6B alter E2F1/Rb pathways and E2F1 localization and cause cell cycle arrest in infected T cells. J Virol. 2007;81(24):13499–13508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01496-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke JR, Deshong AJ, Pelton JG, Rubin SM. Phosphorylation-induced conformational changes in the retinoblastoma protein inhibit E2F transactivation domain binding. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(21):16286–16293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang CK, Balachandran N. Identification, characterization, and sequence analysis of a cDNA encoding a phosphoprotein of human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1991;65(6):2884–2894. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2884-2894.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang CK, Balachandran N. Identification, characterization, and sequence analysis of a cDNA encoding a phosphoprotein of human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1991;65(12):7085. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.7085-.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohdaira H, Sekiguchi M, Miyata K, Sasaki T, Yoshida K. Acute loss of DP1, but not DP2, induces p53 mRNA and augments p21Waf1/Cip1 and senescence. Cell Biochem Funct. October 20, 2011 doi: 10.1002/cbf.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin K, Ricciardi RP. The 41-kDa protein of human herpesvirus 6 specifically binds to viral DNA polymerase and greatly increases DNA synthesis. Virology. 1998;250(1):210–219. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taniguchi T, Shimamoto T, Isegawa Y, Kondo K, Yamanishi K. Structure of transcripts and proteins encoded by U79-80 of human herpesvirus 6 and its subcellular localization in infected cells. Virology. 2000;271(2):307–320. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borenstein R, Singer O, Moseri A, Frenkel N. Use of amplicon-6 vectors derived from human herpesvirus 6 for efficient expression of membrane-associated and -secreted proteins in T cells. J Virol. 2004;78(9):4730–4743. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4730-4743.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson DG, Schwarz JK, Cress WD, Nevins JR. Expression of transcription factor E2F1 induces quiescent cells to enter S phase. Nature. 1993;365(6444):349–352. doi: 10.1038/365349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Bolle L, Hatse S, Verbeken E, De Clercq E, Naesens L. Human herpesvirus 6 infection arrests cord blood mononuclear cells in G(2) phase of the cell cycle. FEBS Lett. 2004;560(1-3):25–29. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takaku T, Ohyashiki JH, Zhang Y, Ohyashiki K. Estimating immunoregulatory gene networks in human herpesvirus type 6-infected T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336(2):469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson JR, Agulnick AD, Ricciardi RP. A novel cis element essential for stimulated transcription of the p41 promoter of human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1994;68(7):4478–4485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4478-4485.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burrel S, Aït-Arkoub Z, Agut H, Boutolleau D. Genotypic characterization of herpes simplex virus DNA polymerase UL42 processivity factor. Antiviral Res. 2012;93(1):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ertl PF, Powell KL. Physical and functional interaction of human cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase and its accessory protein (ICP36) expressed in insect cells. J Virol. 1992;66(7):4126–4133. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4126-4133.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bieda M, Xu X, Singer MA, Green R, Farnham PJ. Unbiased location analysis of E2F1-binding sites suggests a widespread role for E2F1 in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16(5):595–605. doi: 10.1101/gr.4887606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rayman JB, et al. E2F mediates cell cycle-dependent transcriptional repression in vivo by recruitment of an HDAC1/mSin3B corepressor complex. Genes Dev. 2002;16(8):933–947. doi: 10.1101/gad.969202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neill SD, Hemstrom C, Virtanen A, Nevins JR. An adenovirus E4 gene product trans-activates E2 transcription and stimulates stable E2F binding through a direct association with E2F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(5):2008–2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Workman A, Jones C. Productive infection and bICP0 early promoter activity of bovine herpesvirus 1 are stimulated by E2F1. J Virol. 2010;84(13):6308–6317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00321-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.