Abstract

Chronic lung infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the major severe complication in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, where P. aeruginosa persists and grows in biofilms in the endobronchial mucus under hypoxic conditions. Numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) surround the biofilms and create local anoxia by consuming the majority of O2 for production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). We hypothesized that P. aeruginosa acquires energy for growth in anaerobic endobronchial mucus by denitrification, which can be demonstrated by production of nitrous oxide (N2O), an intermediate in the denitrification pathway. We measured N2O and O2 with electrochemical microsensors in 8 freshly expectorated sputum samples from 7 CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection. The concentrations of NO3 − and NO2 − in sputum were estimated by the Griess reagent. We found a maximum median concentration of 41.8 µM N2O (range 1.4–157.9 µM N2O). The concentration of N2O in the sputum was higher below the oxygenated layers. In 4 samples the N2O concentration increased during the initial 6 h of measurements before decreasing for approximately 6 h. Concomitantly, the concentration of NO3 − decreased in sputum during 24 hours of incubation. We demonstrate for the first time production of N2O in clinical material from infected human airways indicating pathogenic metabolism based on denitrification. Therefore, P. aeruginosa may acquire energy for growth by denitrification in anoxic endobronchial mucus in CF patients. Such ability for anaerobic growth may be a hitherto ignored key aspect of chronic P. aeruginosa infections that can inform new strategies for treatment and prevention.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease. It is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis trans-membrane conductance regulator gene [1] affecting apical ion transport. In the lungs, the defective ion transport results in endobronchial accumulation of thick, viscous mucus that prevents mucociliar cleaning of the lungs, and increases susceptibility to chronic respiratory infections [2], [3]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, gamma proteobacterium, which dominates chronic lung infections in CF patients and is considered the most serious complication of CF [4], [5]. The chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection in CF patients is characterized by presence of endobronchial biofilm aggregates surrounded by numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) [6], [7]. Despite the bactericidal activity of the PMNs and intensive antibiotic therapy, these biofilms persist and grow in the endobronchial mucus of CF patients over many years [7], [8]. P. aeruginosa can withstand the bactericidal activity of the PMNs by forming biofilms of the protective mucoid phenotype [9] and by quorum sensing (QS)-regulated production of leukolytic amounts of rhamnolipid [10]–[13]. The summoned PMNs produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) through a respiratory burst, which leads to intense depletion of molecular oxygen (O2) [14], a common feature of infected endobronchial mucus in CF [6]. Biofilm formation may explain why P. aeruginosa survives the attacking PMNs, but it is not known how P. aeruginosa acquires the energy required for the observed growth in endobronchial secretions [8] when O2 is absent. However, P. aeruginosa can grow anaerobically with alternative electron acceptors or by arginine fermentation [15], and it has been suggested that P. aeruginosa can respire by denitrification in anoxic CF mucus utilizing nitrate (NO3 −) and nitrite (NO2 −), which are both present in sufficient amounts [15], [16]. Although the ability of P. aeruginosa to utilize reduction of NOx for anaerobic respiration is well known [17], denitrification in mucus and persistent biofilms present in the airways of CF patients remains to be demonstrated. Since N2O is a natural intermediate belonging to the gases defining denitrification [17], we used electrochemical microsensors [18] to measure O2 and N2O concentration gradients at high spatio-temporal resolution in freshly expectorated sputum from CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection.

Further evidence for denitrification was obtained from nitrate (NO3 −) and nitrite (NO2 −) turnover measurements in the sputum samples. These measurements provided important new insights to the micro-environmental conditions and chemical dynamics associated with persistent P. aeruginosa lung infections in CF patients and indicate that nitrogen compounds can play an important role in the interaction between pathogenic bacteria and an active immune response.

Results

N2O and O2 in sputum from CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection

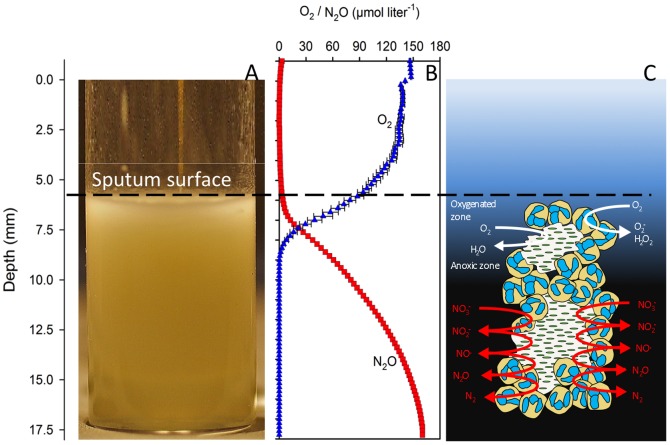

Representative measurements of O2 and N2O in freshly expectorated sputum were acquired with O2- and N2O microsensors (Fig 1A). Measurements of O2- and N2O profiles in expectorated sputum from a CF patient with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection showed the distribution of an upper oxygenated zone and a lower anoxic zone. The N2O profile reached the maximal concentration of N2O in the lower anoxic part of the sputum sample, suggesting that denitrification is mainly confined to the anoxic zone. A slow decline of O2 was apparently detected above the sputum surface. This may be because the position of the sputum surface was estimated by visual inspection, which is associated with uncertainty due to small amounts of heterogeneous saliva (Fig 1B).

Figure 1. Microsensor measurements of chemical gradients in sputum.

(A) Close up of a sputum sample from a cystic fibrosis patient with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection with an inserted microsensor. (B) Representative microprofiles of N2O and O2 in a CF sputum sample. O2 profiles are shown as the mean and SD of three microprofiles recorded in the beginning of the experiment and did not change significantly throughout the experimental period, while the N2O profile represents the maximal N2O levels measured about 6–7 h after beginning. (C) A schematic model of the involved PMN and biofilm processes in CF sputum explaining the microprofiles.

Sputum is composed of heterogeneously distributed bacterial aggregates surrounded by PMNs consuming O2, and this respiratory burst creates local anoxic microenvironments in the sputum [14]. The metabolic mechanisms are thus compartmentalized according to the availability of O2 with an oxygenated zone, wherein the majority of O2 is reduced to superoxide by the summoned PMNs, and an anoxic zone, where P. aeruginosa can utilize nitrate as electron acceptor during oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 1C).

NO3 − and NO2 − in sputum from CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection

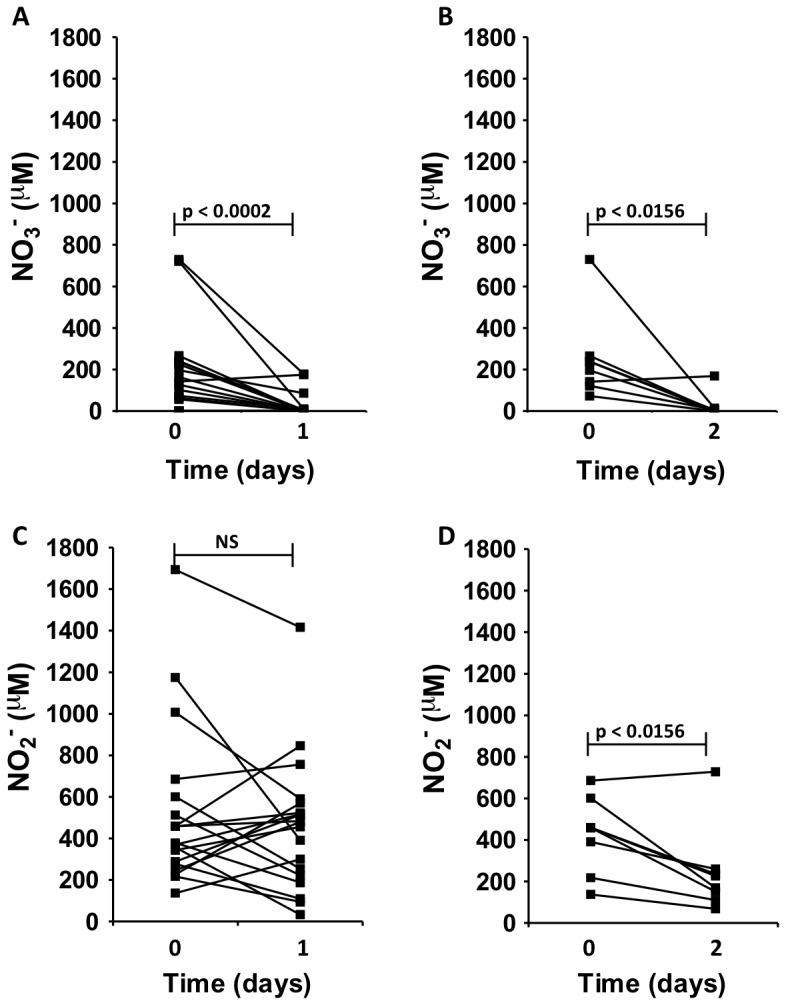

NO3 − and NO2 − concentrations in sputum samples were measured before N2O profiling and 1 day later (Fig 2). The concentration of NO3 − was significantly higher immediately before N2O profiling as compared to 1 and 2 days after incubation indicating NO3 − depletion due to ongoing denitrification (Fig 2A, B). The NO2 − concentration was not changed significantly after one day (Fig 2C), but by including additional measurements of the NO2 − concentration in 7 sputum samples a significantly decreased NO2 − concentration was detected (Fig 2D).

Figure 2. Consumption of NO3− and NO2− in sputum.

(A, B) NO3 − concentration in sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection. (C, D) NO2 − concentration in sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection. Samples were collected immediately after expectoration and after 1 (n = 20) and 2 days (n = 7) of incubation. Data were analyzed by Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Distribution of N2O in sputum from CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection

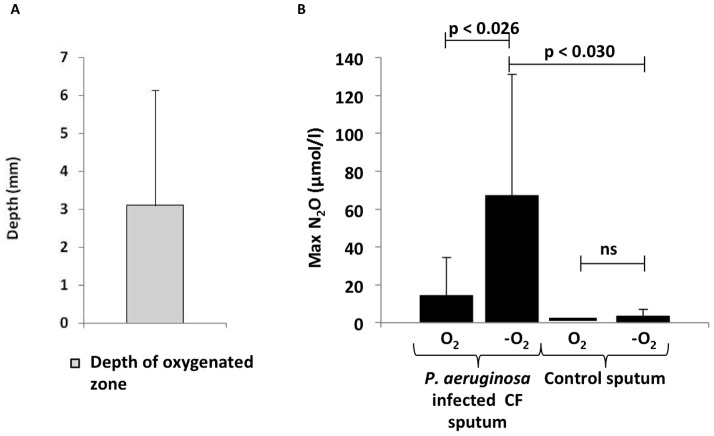

Vertical profiles of O2 in sputum samples showed depletion of O2, indicating the formation of anoxic zones below a mean depth of 3.1 mm (SD = 3.0 mm) from the sputum surface (Fig 3A) suggesting that the average depth of O2 penetration of ∼3 mm. A higher concentration of N2O was observed in the anoxic zone as compared to the oxic zone (p<0.026, n = 8) (Fig 3B). To verify that N2O is related to P. aeruginosa we found significantly less N2O in three control sputum samples from 1 CF patient and from 2 primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) patients without detectable P. aeruginosa (p<0.030).

Figure 3. Distribution of O2 and N2O in sputum.

(A) Depth of oxygenated zone in sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients with chronic P. eruginosa lung infection (n = 8). (B) Maximal N2O concentration in the oxic zone and anoxic zone in sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection (n = 8). Control sputum without detectable P. aeruginosa was obtained from two PCD patients and one CF patient. Statistical analysis was performed by Student t-test.

Dynamics of N2O in sputum from a CF patient with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection

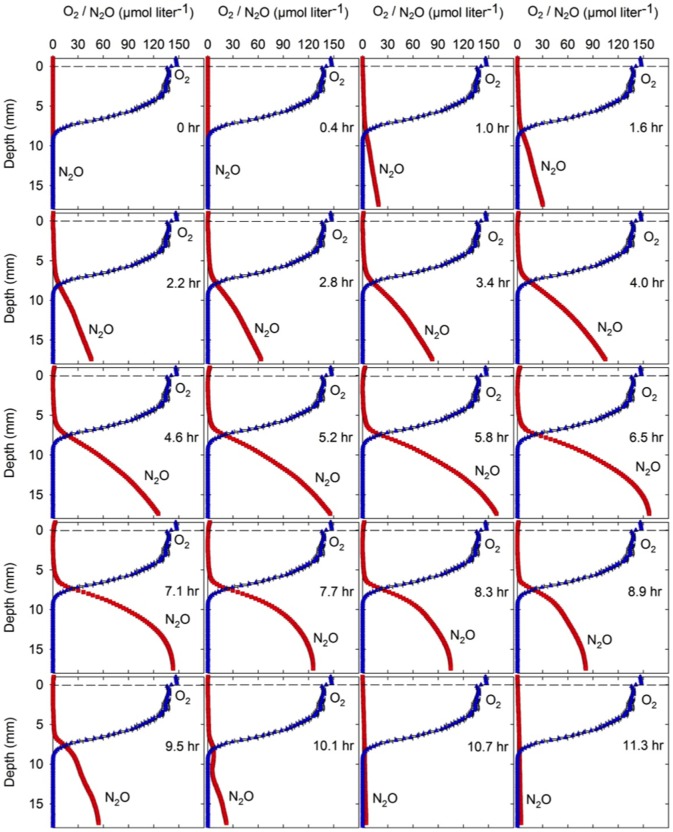

Figure 4 displays time series of representative N2O profiles measured vertically through a sputum sample. The distribution of O2 is displayed at 0 hr. During the initial measuring period, N2O accumulated in the anoxic zone reaching a maximum concentration of 160 µM after 6.5 h incubation, which indicates ongoing production of N2O. Within the subsequent 4 hours the accumulated N2O decreased indicating consumption through reduction to N2.

Figure 4. Generation and depletion of N2O in sputum.

Spatio-temporal dynamics of N2O concentration profiles in a representative sputum sample from a cystic fibrosis patient with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection showing initial accumulation of N2O in the anoxic zone followed by total depletion. The O2 concentration profile is shown as the mean and SD of three microprofiles recorded at the beginning of the experiment.

Rates of N2O production and consumption in sputum samples

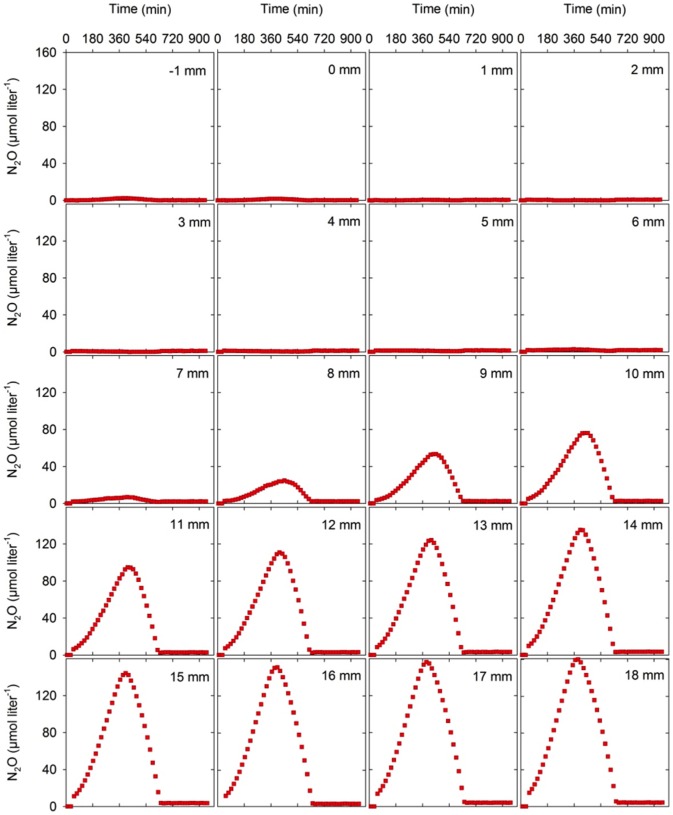

Measurements of the N2O concentration dynamics over time in particular depths of a sputum sample showed an initial build-up of N2O in layers below 7 mm (Fig. 5). In each layer, the slope of the net production curves was quasi-linear after ∼180 min indicating a constant production of N2O related to the particular layer and therefore that N2O originates from immobile sources such as biofilm. The production ceased about 6–7 h after start of the sample incubation, and was then followed by a net consumption of N2O over the following 4–5 h leading to N2O depletion in the sputum sample after ∼10–12 hours. In 4 sputum samples it was possible to estimate N2O production and consumption rates (Table 1) and N2O flux rates and cumulated emission (Figure 6) from measurements of such dynamic N2O concentration micro-gradients. A substantial initial N2O concentration was observed in the anaerobic zone of the remaining 4 assayed sputum samples. In these samples the N2O concentration decreased steadily during incubation.

Figure 5. Rates of N2O production and consumption in sputum.

Depth specific plots of N2O concentration vs. time at particular measuring depths in the same sputum sample as displayed in Fig 4. Accumulation and thus net production of N2O in all depths was observed until approximately 6 h, followed by net consumption of N2O presumably due to depletion of nitrate around 6 h.

Table 1. N2O production, consumption, max emission, and cumulated emission in 4 CF sputum samples.

| Net production rate | Net consumption rate | Max emission | Cumulated emission | |

| (nmol cm−3min−1) | (nmol cm−3min−1) | (nmol cm−2 min−1) | (nmol cm−2) | |

| Median | 0.47 | −0.39 | 5.06×10−5 | 1.05×10−2 |

| Range | 0.40–0.70 | −0.77–−0.10 | 1.8×10−5–6.78×10−5 | 3.94×10−3–1.46×10−2 |

Figure 6. Efflux and cumulated emission of N2O from sputum samples.

(A) Estimated N2O efflux rates in sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection as calculated from N2O microprofiles (n = 4). (B) Cumulated N2O emission as calculated from N2O microprofiles (n = 4). I, II, III and IV represents 4 different sputum samples.

Discussion

The ability of microorganisms to exploit a wide range of electron acceptors for ATP generation by oxidative phosphorylation provides metabolic flexibility in transient environments as these organisms inhabit a variety of habitats ranging from soils, sediments to aquatic environments [19]. Even though several human pathogens, including P. aeruginosa, are equipped with the genetic setup for denitrification [20]–[22] including nitric oxide reductase (NOR) [22], we present the very first observations of N2O production in clinical material from infected human airways demonstrating pathogenic metabolism based on denitrification. These data indicate that denitrification may serve as an alternative metabolic pathway allowing P. aeruginosa to thrive in O2 depleted micro niches in the airways of CF patients. Besides our study, denitrification in humans has previously been demonstrated in human dental plaque [23] and has been related to infections of the gastrointestinal tract by the increased concentration of N2O in exhaled breath from patients after oral intake of NO3 − [24].

Seminal observations of O2 depletion and the presence of OprF porin, which is involved in NO3 − and NO2 − diffusion, in habitats of P. aeruginosa during chronic lung infection of CF patients provided initial evidence for anaerobic respiration by denitrification [6], [16]. To demonstrate denitrification we have included CF patients, who suffered from chronic P. aeruginosa infection in the endobronchial mucus as detected by routine culturing. We revealed a depletion of O2 in CF sputum samples, which is in accordance with the steep O2 gradients in endobronchial CF mucus [6] and due to O2 consumption by activated PMNs for generation of ROS [14]. Our O2 measurements in sputum confirmed the presence of O2 concentration gradients reaching anoxia ∼3 mm below the sputum surface.

The depletion of O2 for microbial respiration in infected endobronchial CF mucus has motivated the present and several other studies of anaerobic metabolism by P. aeruginosa based on denitrification during chronic lung infection in CF. We demonstrated N2O production and consumption in the sputum samples indicating the presence of active NOR and nitrous oxide reductase (N2OR) for the reduction of nitric oxide (NO•) and N2O [17]. Previously, NOR has been isolated from P. aeruginosa [25], the genes (norCB) have been sequenced [26] and functional NOR has been observed in clinical strains of P. aeruginosa by consumption of NO• [27].

In our study, the initial phase of N2O production in the sputum samples was followed by a period of net N2O consumption suggesting a depletion of NO• and a concomitant reduction of N2O to N2 by N2OR. The N2O consumption is in agreement with the demonstration of N2OR activity and the identification of the nos genes in P. aeruginosa [28] as well as the induced genes for a N2OR precursor in clinical isolates [29].

Our demonstration of significant N2O production in sputum indicates ample presence of NO3 − and NO2 − that serve as electron acceptors for the denitrification pathway. We found high levels of NO3 − and NO2 − in the sputum, which are in agreement with previous findings [30]–[32]. It has been proposed that NO3 − and NO2 − in CF sputum originates from the rapid reaction between superoxide (O2 -) and NO• [15]. In this regard, we suggest the summoned activated PMNs [14] as a major source of O2 -, while NO•, which is present in CF exhaled breath [33], [34], may be produced by a variety of cells in the lungs. In fact, inhalation of NO• or incubation of sputum samples with NO• resulted in elevated levels of NO3 − and NO2 − in sputum from CF patients [35]. In addition, ongoing activity of the patients nitric oxide synthases was evidenced by the increased exhaled NO• from infected CF patients following supplementation with the substrate L-arginine [36], [37].

As a consequence of our demonstration of N2O production, we expected a consumption of the precursors NO3 − and NO2 −. Accordingly, NO3 − was depleted in the sputum after incubation for 1 day, which likely is due to the membrane-bound nitrate reductase of P. aeruginosa [29]. NO3 − consumption may also accompany assimilatory denitrification and ammonification resulting in the formation of ammonia (NH4 +) [17], which has been detected in CF sputum [27]. However, assimilatory denitrification and ammonification does not involve production of N2O [17], [38], [39] and NH4 + is also produced by several human cell types [40]. The concentration of NO2 − was not changed during 1 day of incubation, but after 2 days of incubation the concentration of NO2 − in the sputum was decreased significantly. This indicates that the production of NO• from NO2 − is slower than the generation of NO2 − resulting from reduction of NO3 −. Indeed, during reduction of NO3 − transient accumulation of NO2 − is known from anaerobic cultures of P. aeruginosa growing by denitrification [16], [41], [42].

A further verification of ongoing dissimilatory denitrification in sputum is evident from the calculated rate of N2O production (Fig. 6A), which easily can explain the depletion of NO3 − during incubation (Fig. 2A). The depletion of NO3 − in the sputum samples indicates that the NO3 − in sputum samples is not replaced by the reaction between O2 - and NO. This is possibly due to lack of contributions from immigrating PMNs and the epithelia as opposed to the conditions in the endobronchial mucus.

Since we calculated the rates of N2O production by assuming linear changes between subsequent measurements in the beginning of incubation, the estimates are likely to reflect the situation in the endobronchial mucus, where reduced NO3 − and NO2 − is continuously being replaced as indicated by the high NO3 − and NO2 − content in fresh sputum. The estimated N2O production, however, is calculated from the actual N2O content and does not include the reduction of N2O to N2. Therefore, the actual rate of denitrification may be higher than our estimates.

We found the highest concentration of N2O in the anoxic zone of the confined sputum samples indicating higher rate of denitrification without O2 as previously demonstrated [43]. Accordingly, we suggest that the low concentration of N2O found in the oxygenated zone is mainly due to diffusion from the active anoxic zone. Additionally, our estimate of the depth of the oxygenated zone implies that the bronchi, with diameters ranging from 0.8 to 13 mm [44], [45], allow for numerous anoxic zones in the endobronchial mucus of the lungs and confirms the in vivo demonstration of O2 depletion in the endobronchial mucus [6]. Consequently, our results propose the existence of several zones with N2O production in the anoxic endobronchial mucus of the lungs of CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection. However, such in vivo production of N2O in CF patients still awaits direct experimental confirmation.

The involvement of denitrification enzymes as terminal oxidases that reduce nitrogen oxides in the highly branched respiratory chain of P. aeruginosa may enable anaerobic growth in the presence of nitrate or nitrite [19], [46]. But the engagement of denitrification in P. aeruginosa may also contribute to virulence as evidenced by the finding of antibodies directed against components of denitrification in CF patients with P. aeruginosa lung infection [16], [47] and the dependence on nitrite reductase for type III secretion [48]. In anaerobic cultures, denitrification promotes growth of P. aeruginosa [49], increases antibiotic tolerance of P. aeruginosa [50] and favors maintenance of the virulent mucoid phenotype [30].

A particular contribution to the pathogenesis of chronic lung infection in CF by NOR activity, is suggested by the induced in vivo gene expression in clinical isolates [29] including the highly virulent mucoid isolates [51]. In this respect, the reduction of NO• to N2O by active NOR may actually protect P. aeruginosa from the bactericidal action of NO• generated by the immune system. In fact, NOR-deficient P. aeruginosa is more susceptible to NO• generated by macrophages [52] and less virulent during infection of silkworm [53]. In addition, NOR activity increases the virulence of several pathogens [54]–[56].

In conclusion, this study points to the presence of anoxic microenvironments with strong spatio-temporal heterogeneity as well as a possible stratification of metabolic processes in the biofilm aggregates characteristic of chronic P. aeruginosa infections in the airways of CF patients. Such structural and metabolic heterogeneity may be a characteristic trait ensuring persistent infection. Indeed, spatio-temporal resolved measurements enabled the demonstrated of N2O production in the anaerobic zones of freshly expectorated sputum samples from CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection for the first time. Analysis of the N2O production rates suggests ongoing generation of N2O in the lungs of CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection. N2O production by P. aeruginosa in this environment is associated with anaerobic growth, which can promote increased virulence and tolerance to antibiotic, as well as contribute to evasion of the host response. The chronic infected CF lung is in many ways a black box. By using the presented approach to elucidate the essential metabolites we may now open the black box and start mapping the micro-environment of infection which may inspire new strategies for prevention and treatment of chronic lung infections in CF.

Materials and Methods

Sputum Samples

As defined by the “Danish Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects” Section 2 the project does not constitute a health research project and was thus initiated without approval from The Committees on Health Research Ethics in the Capital Region of Denmark. Therefore, verbal informed consent was obtained using waiver of documentation of consent. The study was carried out on 21 anonymized samples of surplus expectorated sputum from 21 CF patients and 2 PCD patients (Table 2). Chronic P. aeruginosa infection was defined as the presence of P. aeruginosa in the lower respiratory tract at each monthly culture for >6 months, or for a shorter time in the presence of increased antibody response to P. aeruginosa (>2 precipitating antibodies, normal: 0–1) [57].

Table 2. Demographic data of the patients.

| CF patients | PCD patients | ||

| Infectious status | |||

| P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | H. influenzae | |

| Number (male) | 20 (10) | 1 (1) | 2 (0) |

| Age (years)* | 39 (24–50) | 17 | 32 (27–36) |

| Duration of chronic infection (years)* , ** | 19 (4–38) | ||

| FEV1 (%)* | 56 (23–96) | 75 | 89 (70–109) |

| FVC (%)* | 88 (46–139) | 82 | 110 (95–125) |

*Values are medians (range).

*Duration of chronic infection is only recorded for P. aeruginosa infections.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

FVC, forced vital capacity.

Microsensor Measurements of O2 and N2O

Each of 8 different sputum samples (1–2 ml) was added to a glass vial (35×12 mm) (Schuett Biotec, Germany) and allowed to settle for about 10 min. The glass vials were positioned in a heated metal rack, kept at 37°C. Vertical O2-concentration profiles were recorded in the sputum with an amperometric O2 microsensor (OX25, Unisense A/S, Århus, Denmark) mounted in a motorized PC-controlled profiling setup (MM33 and MC-232, Unisense A/S). Subsequently, vertical N2O concentration profiles were recorded at defined time intervals for up to 12 hours with an amperometric N2O microsensor [18] (N2O-25, Unisense A/S) mounted in the micromanipulator.

The microsensors (tip diameter 25 µm) were connected to a picoammeter (PA2000, Unisense A/S) and positioned manually onto the upper surface of the sputum sample. Profile measurements were taken by movement of the sensor in vertical steps of 100 or 200 µm through the sputum sample. Positioning and data acquisition were controlled by dedicated software (Sensortrace Pro 2.0, Unisense A/S). The software was set to wait 3 seconds for the O2-microprofile and 5 seconds for the N2O-microprofile, before actual measurement and subsequent movement of the sensors to the next measuring depth. The interval between each cycle of profile measurements was 10 seconds.

The O2-microsensor was linearly calibrated by measuring the sensor signal in an alkaline sodium ascorbate solution (zero O2) and in air saturated free phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at experimental temperature and salinity. The O2 concentration in air saturated water was determined from the known temperature and salinity according to [58]. The N2O -microsensor was linearly calibrated according to [18] by measuring sensor signals in N2O free PBS at experimental temperature and salinity and in PBS with sequential addition of a known volume of N2O saturated PBS up to a final concentration of 100 µM N2O. The N2O concentration in saturated PBS was determined according to [59].

NO3 − and NO2 − quantification

The concentration of NO3 − and NO2 − in sputum was measured in 20 samples. From each sputum sample, 0.1 ml was aspired with a syringe and was immediately diluted 10x in PBS and stored at -20°C for later analysis. The remaining sample was incubated in a glass vial at 37°C for 24 h before dilution 10x in PBS and storage at −20°C. The NO3 − and NO2 − levels in the sputum were measured using the Griess colorimetric reaction (no. 780001, Cayman Chemicals, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For this, sputum samples were transferred to a 96 well microtiter plate. NO2 − concentration was estimated by addition of the Griess Reagent for 10 minutes, whereby NO2 − was converted into a purple azo-compound, which was quantitated by the optical density at 540–550 nm measured with an ELISA plate reader (Thermo Scientific Multiskan EX, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, BioImage, Denmark). Total NO3 − and NO2 − levels were estimated by a two-step analysis process: The first step converted NO3 − to NO2 − utilizing NO3 − reductase. After incubation for 2 hours, the next step involved the addition of the Griess Reagent, whereby NO2 − was converted into a purple azo-compound. After incubation with Griess Reagent for 10 minutes, the optical density at 540–550 nm was measured with an ELISA plate reader (Thermo Scientific Multiskan EX, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, BioImage, Denmark). A NO3 − standard curve was used for determination of total NO3 − and NO2 − concentration, while a NO2 − standard curve was used for determination of NO2 − alone. The concentration of NO3 − was calculated as the difference between the NO3 − concentration and the total NO3 − and NO2 − concentration.

Calculations of N2O production rates

The local N2O fluxes in sputum samples were calculated from the measured N2O concentration gradient in the uppermost oxic sputum layer. It was assumed that no production or consumption of N2O occurred in the presence of O2. The flux was calculated using a modified version of Fick's 1st law of diffusion [60], where the slope of the profile in the sputum surface layer was calculated from the three uppermost measured concentrations (measurement a, b and c):

where J is the flux of N2O (nmol N2O cm−2 min−1), D is the molecular diffusion coefficient of N2O in water at 37°C (2.76×10−5 cm2 s−1) [61] and C is the concentration of N2O (µmol liter−1) at depth xn, where n = a, b or c denote 3 subsequent depths of measurement. The cumulated N2O emission was calculated by assuming linear changes between subsequent measurements. Net production and net consumption rates of N2O in particular sputum layers were calculated from the slopes of linear increase and decrease of N2O concentration at particular measuring depths in the sputum samples [62], [63].

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance was evaluated by Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test and by Students T-test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The tests were performed with Prism 4.0c (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA).

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, et al. (1989) Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245: 1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knowles MR, Boucher RC (2002) Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest 109: 571–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boucher RC (2007) Evidence for airway surface dehydration as the initiating event in CF airway disease. J Intern Med 261: 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koch C, Høiby N (1993) Pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis. Lancet 341: 1065–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koch C, Høiby N (2000) Diagnosis and treatment of cystic fibrosis. Respiration 67: 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Worlitzsch D, Tarran R, Ulrich M, Schwab U, Cekici A, et al. (2002) Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Invest 109: 317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PØ, Fiandaca MJ, Pedersen J, Hansen CR, et al. (2009) Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in the respiratory tract of cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Pulmonol 44: 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang L, Haagensen JA, Jelsbak L, Johansen HK, Sternberg C, et al. (2008) In situ growth rates and biofilm development of Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations in chronic lung infections. J Bacteriol 190: 2767–2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pedersen SS, Moller H, Espersen F, Sorensen CH, Jensen T, et al. (1992) Mucosal immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate in cystic fibrosis. APMIS 100: 326–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PØ, Burmolle M, Hentzer M, Haagensen JA, et al. (2005) Pseudomonas aeruginosa tolerance to tobramycin, hydrogen peroxide and polymorphonuclear leukocytes is quorum-sensing dependent. Microbiology 151: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen PØ, Bjarnsholt T, Phipps R, Rasmussen TB, Calum H, et al. (2007) Rapid necrotic killing of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is caused by quorum-sensing-controlled production of rhamnolipid by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Microbiology 153: 1329–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van GM, Christensen LD, Alhede M, Phipps R, Jensen PØ, et al. (2009) Inactivation of the rhlA gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa prevents rhamnolipid production, disabling the protection against polymorphonuclear leukocytes. APMIS 117: 537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alhede M, Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PØ, Phipps RK, Moser C, et al. (2009) Pseudomonas aeruginosa recognizes and responds aggressively to the presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Microbiology 155: 3500–3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kolpen M, Hansen CR, Bjarnsholt T, Moser C, Christensen LD, et al. (2010) Polymorphonuclear leucocytes consume oxygen in sputum from chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 65: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hassett DJ, Cuppoletti J, Trapnell B, Lymar SV, Rowe JJ, et al. (2002) Anaerobic metabolism and quorum sensing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in chronically infected cystic fibrosis airways: rethinking antibiotic treatment strategies and drug targets. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54: 1425–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon SS, Hennigan RF, Hilliard GM, Ochsner UA, Parvatiyar K, et al. (2002) Pseudomonas aeruginosa anaerobic respiration in biofilms: relationships to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis. Dev Cell 3: : 593–603. S1534580702002952 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zumft WG (1997) Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61: 533–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andersen K, Kjær T, Revsbech NP (2001) An oxygen insentitive microsensor for nitrous oxide. Sensors & Actuators B: Chemical 81: 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richardson DJ (2000) Bacterial respiration: a flexible process for a changing environment. Microbiology 146 (Pt 3): 551–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Philippot L (2002) Denitrifying genes in bacterial and Archaeal genomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1577: 355–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Philippot L (2005) Denitrification in pathogenic bacteria: for better or worst? Trends Microbiol 13: 191–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zumft WG (2005) Nitric oxide reductases of prokaryotes with emphasis on the respiratory, heme-copper oxidase type. J Inorg Biochem 99: 194–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schreiber F, Stief P, Gieseke A, Heisterkamp IM, Verstraete W, et al. (2010) Denitrification in human dental plaque. BMC Biol 8: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitsui T, Kondo T (2004) Increased breath nitrous oxide after ingesting nitrate in patients with atrophic gastritis and partial gastrectomy. Clin Chim Acta 345: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hino T, Matsumoto Y, Nagano S, Sugimoto H, Fukumori Y, et al. (2010) Structural basis of biological N2O generation by bacterial nitric oxide reductase. Science 330: 1666–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arai H, Igarashi Y, Kodama T (1995) The structural genes for nitric oxide reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Biochim Biophys Acta 1261: 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gaston B, Ratjen F, Vaughan JW, Malhotra NR, Canady RG, et al. (2002) Nitrogen redox balance in the cystic fibrosis airway: effects of antipseudomonal therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. SooHoo CK, Hollocher TC (1991) Purification and characterization of nitrous oxide reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain P2. J Biol Chem 266: 2203–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Son MS, Matthews WJ Jr, Kang Y, Nguyen DT, Hoang TT (2007) In vivo evidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa nutrient acquisition and pathogenesis in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun 75: 5313–5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hassett DJ (1996) Anaerobic production of alginate by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: alginate restricts diffusion of oxygen. J Bacteriol 178: 7322–7325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jones KL, Hegab AH, Hillman BC, Simpson KL, Jinkins PA, et al. (2000) Elevation of nitrotyrosine and nitrate concentrations in cystic fibrosis sputum. Pediatr Pulmonol 30: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palmer KL, Brown SA, Whiteley M (2007) Membrane-bound nitrate reductase is required for anaerobic growth in cystic fibrosis sputum. J Bacteriol 189: 4449–4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grasemann H, Michler E, Wallot M, Ratjen F (1997) Decreased concentration of exhaled nitric oxide (NO) in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 24: 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Linnane SJ, Keatings VM, Costello CM, Moynihan JB, O'Connor CM, et al. (1998) Total sputum nitrate plus nitrite is raised during acute pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ratjen F, Gartig S, Wiesemann HG, Grasemann H (1999) Effect of inhaled nitric oxide on pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. Respir Med 93: 579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grasemann H, Grasemann C, Kurtz F, Tietze-Schillings G, Vester U, et al. (2005) Oral L-arginine supplementation in cystic fibrosis patients: a placebo-controlled study. Eur Respir J 25: 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grasemann H, Tullis E, Ratjen F (2013) A randomized controlled trial of inhaled l-Arginine in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38. Einsle O, Messerschmidt A, Stach P, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, et al. (1999) Structure of cytochrome c nitrite reductase. Nature 400: 476–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Einsle O, Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Kroneck PMH, Neese F (2002) Mechanism of the six-electron reduction of nitrite to ammonia by cytochrome c nitrite reductase. J Am Chem Soc 124: ; 11737–11745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Planelles G (2007) Ammonium homeostasis and human Rhesus glycoproteins. Nephron Physiol 105: ; 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Williams DR, Rowe JJ, Romero P, Eagon RG (1978) Denitrifying Pseudomonas aeruginosa: some parameters of growth and active transport. Appl Environ Microbiol 36: 257–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoffman LR, Richardson AR, Houston LS, Kulasekara HD, Martens-Habbena W, et al. (2010) Nutrient availability as a mechanism for selection of antibiotic tolerant Pseudomonas aeruginosa within the CF airway. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thomas KL, Lloyd D, Boddy L (1994) Effects of oxygen, pH and nitrate concentration on denitrification by Pseudomonas species. FEMS Microbiol Lett 118: 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seneterre E, Paganin F, Bruel JM, Michel FB, Bousquet J (1994) Measurement of the internal size of bronchi using high resolution computed tomography (HRCT). Eur Respir J 7: 596–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hampton T, Armstrong S, Russell WJ (2000) Estimating the diameter of the left main bronchus. Anaesth Intensive Care 28: 540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Arai H (2011) Regulation and Function of Versatile Aerobic and Anaerobic Respiratory Metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Front Microbiol 2: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beckmann C, Brittnacher M, Ernst R, Mayer-Hamblett N, Miller SI, et al. (2005) Use of phage display to identify potential Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products relevant to early cystic fibrosis airway infections. Infect Immun 73: 444–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Van Alst NE, Wellington M, Clark VL, Haidaris CG, Iglewski BH (2009) Nitrite reductase NirS is required for type III secretion system expression and virulence in the human monocyte cell line THP-1 by Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Infect Immun 77: 4446–4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williams DR, Rowe JJ, Romero P, Eagon RG (1978) Denitrifying Pseudomonas aeruginosa: some parameters of growth and active transport. Appl Environ Microbiol 36: 257–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Borriello G, Werner E, Roe F, Kim AM, Ehrlich GD, et al. (2004) Oxygen limitation contributes to antibiotic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48: 2659–2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee B, Schjerling CK, Kirkby N, Hoffmann N, Borup R, et al. (2011) Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates maintain the biofilm formation capacity and the gene expression profiles during the chronic lung infection of CF patients. APMIS 119: 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kakishima K, Shiratsuchi A, Taoka A, Nakanishi Y, Fukumori Y (2007) Participation of nitric oxide reductase in survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in LPS-activated macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 355: 587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arai H, Iiyama K (2013) Role of nitric oxide-detoxifying enzymes in the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa against the silkworm, Bombyx mori Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 77: : 198–200. DN/JST.JSTAGE/bbb/120656 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shimizu T, Tsutsuki H, Matsumoto A, Nakaya H, Noda M (2012) The nitric oxide reductase of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli plays an important role for the survival within macrophages. Mol Microbiol 85: 492–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stevanin TM, Moir JW, Read RC (2005) Nitric oxide detoxification systems enhance survival of Neisseria meningitidis in human macrophages and in nasopharyngeal mucosa. Infect Immun 73: 3322–3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Loisel-Meyer S, Jimenez de Bagues MP, Basseres E, Dornand J, Kohler S, et al. (2006) Requirement of norD for Brucella suis virulence in a murine model of in vitro and in vivo infection. Infect Immun 74: 1973–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Høiby N (2000) Microbiology of cystic fibrosis. In: Hodson ME GD, editors. Cystic fibrosis. London, UK: Arnold. pp. 83–107.

- 58. Gundersen JK, Glud RN, Ramsing NB (1998) Predicting the signal of O2 microsensors from physical dimensions, temperature, salinity, and O2 concentration. Limnol Oceanogr 43: 1932–1937. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Weiss RF, Price BA (1980) Nitrous oxide solubility in water and seawater. Marine Chemistry 8: 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Beer D, Stoodley P (2006) Microbial biofilms. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E, editors. The Prokaryotes. New York: Springer Science. pp. 904–937.

- 61. Broecker WS, Peng TH (1974) Gas-exchange rates between air and sea. Tellus 26: 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Markfoged R, Nielsen LP, Nyord T, Ottosen LDM, Revsbech NP (2013) Transient N2O accumulation and emission caused by O2 depletion in soil after liquid manure injection. European journal of soil science 62: 541–550. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liengaard L, Nielsen LP, Revsbech NP, Priemé A, Elberling B, et al. (2013) Extreme emission of N2O from tropical wetland soil (Pantanal, South America). Frontiers in Microbiology 3: 433 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]