Abstract

Background and purpose of the study

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors plays a critical role in treating hypertension. The purpose of the present investigation was to evaluate ACE inhibition activity of 50 Iranian medicinal plants using an in vitro assay.

Methods

The ACE activity was evaluated by determining the hydrolysis rate of substrate, hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine (HHL), using reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity were determined by Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method and DPPH radical scavenging assay respectively.

Results

Six extracts revealed > 50% ACE inhibition activity at 330 μg/ml concentration. They were Berberis integerrima Bunge. (Berberidaceae) (88.2 ± 1.7%), Crataegus microphylla C. Koch (Rosaceae) (80.9 ± 1.3%), Nymphaea alba L. (Nymphaeaceae) (66.3 ± 1.2%), Onopordon acanthium L. (Asteraceae) (80.2 ± 2.0%), Quercus infectoria G. Olivier. (Fagaceae) (93.9 ± 2.5%) and Rubus sp. (Rosaceae) (51.3 ± 1.0%). Q. infectoria possessed the highest total phenolic content with 7410 ± 101 mg gallic acid/100 g dry plant. Antioxidant activity of Q. infectoria (IC50 value 1.7 ± 0.03 μg/ml) was more than that of BHT (IC50 value of 10.3 ± 0.15 μg/ml) and Trolox (IC50 value of 3.2 ± 0.06 μg/ml) as the positive controls.

Conclusions

In this study, we introduced six medicinal plants with ACE inhibition activity. Despite the high ACE inhibition and antioxidant activity of Q. infectoria, due to its tannin content (tannins interfere in ACE activity), another plant, O. acanthium, which also had high ACE inhibition and antioxidant activity, but contained no tannin, could be utilized in further studies for isolation of active compounds.

Keywords: Angiotensin converting enzyme, Screening, Medicinal plants, Total phenolic content, Antioxidant activity

Introduction

In 2000, 26.4% of the world’s population suffered hypertension and it is predicted that this rate would increase by 60% in 2025 [1]. Since the proportion of hypertensive people will increase rapidly, new therapeutic approaches for management of hypertension are essential. High blood pressure is a silent killer, causing several serious diseases such as heart failure, kidney failure and stroke. There are a number of choices for the treatment of hypertension. Some treatments include diuretics, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers and angiotensin II receptor blockers, the most common of which is angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors.

Angiotensin converting enzyme, EC 3.4.15.1, is a zinc metallopeptidase that converts the angiotensin I (inactive decapeptide) to angiotensin II (a potent vasoconstrictor), and bradykinin (a hypotensive peptide) to inactive components [2]. High ACE activity leads to increased concentration of angiotensin II and hypertension. Therefore, development of agents that inhibit the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, and bradykinin to inactive components began as a therapeutic strategy to treat hypertension. ACE inhibitors such as captopril and lisinopril play key roles in treating hypertension and maintaining the electrolyte balance [3]. They are commonly used as they are safe and well tolerated with few side effects.

Tannins are plant polyphenolic compounds that precipitate proteins and interfere in the functions of many macromolecules including ACE. Therefore, plants with ≥ 50% ACE inhibition activity would be further tested for the presence of tannins in order to eliminate false positives [4].

Furthermore, reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a significant role in cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and congestive heart failure. In hypertensive patients, angiotensin II increases chronically and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase is activated, which causes a rise in ROS. As a result, it is more beneficial for an antihypertensive drug to have antioxidant effect [5]. Phenolic compounds have antioxidant activity and are effective agents to prevent oxidative stress.

Natural products could be important sources of ACE inhibitors such as captopril, a synthetic antihypertensive drug, which is developed by changing and optimizing the structure of the venom of the Brazilian viper. Active substances derived from medicinal plants can also be a source of new ACE inhibitors. Moreover, some plants contain a great amount of phenolic compounds, so consequently, they have antioxidant activity.

In this study, some medicinal plants that are used to manage different diseases were screened to discover possible new ACE inhibition activity using an in vitro ACE inhibition assay. Among the plants tested, the most active ones were examined for total phenolic content and antioxidant activity.

Material and methods

Chemicals

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) from rabbit lung, hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine (HHL), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer, hippuric acid (HA) and captopril were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (England). HCl, KH2PO4, methanol (HPLC grade), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, Na2CO3, gallic acid, butylated hydroxyl toluene (BHT), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), FeCl3, NaCl, NaOH and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Merck Co. (Germany). Ultrapure water was applied to prepare all of the aqueous solutions.

Apparatus

Enzymatic incubation was performed in a thermomixer eppendorf comfort (Germany). HPLC analysis was carried out by a Knauer liquid chromatograph, with an ODS Eurospher column (250 × 4.6 mm, 100–5; C18), protected by a C18 precolumn (Perfectsil Target, ODS-3 (5 μm)) and a 20 μl injection loop. A smartline Photodiode Array (PDA) detector 2850 (Knauer, Germany) was used to detect analytes, and a Chromgate software version 3.3, was used for data processing. A Cecil UV/Vis spectrophotometer (series 9000) was utilized to measure the absorbances.

Plant materials

Some of the studied plants (41 plants) were purchased from a local herbal store located in Tehran, Iran (June 2011). Rubus sp. was collected from north of Iran, Mazandaran province (June 2012), and 8 other plants were collected from Herburatum of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (June 2011). All of the mentioned plants were identified by Prof. G. Amin. Voucher specimens of the collected plants were deposited in the Herbarium of Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Preparation of crude extracts

Dried plant materials (1 g) were extracted with 20 ml methanol:water (80:20, v/v) at room temperature for 24 h and then over 2 h in an ultrasonic bath [6]. The extracts were filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure, using a rotary evaporator at room temperature and then they were lyophilized.

ACE inhibition assay

In this study, the assay method is based on the hydrolysis of the substrate HHL by ACE, and measuring the amount of HA using RP-HPLC [6-9]. HEPES buffer solution used in this assay was prepared by dissolving 50 mM HEPES and 300 mM NaCl in 1000 ml water and adjusting the solution to pH 8.3 by 1 M NaOH solution. The substrate solution (9 mM) was prepared by dissolving HHL (19.74 mg) in 5 ml of HEPES buffer. Herbal extract (1 mg) was dissolved in 1 ml of solvent containing buffer/DMSO (90:10, v/v) to provide 330 μg/ml concentration (a comparable scale all over the world) [10].

First, ACE solution (25 μl) (80 mU/ml) was added to 25 μl of inhibitor solution (or solvent as negative control). After 3 min preincubation at 37°C, 25 μl substrate solution was added and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min with shaking at 300 rpm in an Eppendorf thermomixer. After 30 min, the reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μl of 1 M HCl and then the reaction mixture was subjected to RP-HPLC. The mobile phase was an isocratic system consisting of a mixture of 10 mM KH2PO4 (adjusted to pH 3 with H3PO4) and methanol (50:50, v/v). The flow rate was 1 ml/min and the injection volume was 20 μl. Analytes were detected by a PDA detector at the wavelength of 228 nm.

ACE inhibition measurement

ACE inhibition calculation was based on the ratio of the area under curve (AUC) of HA peak in an inhibitor sample to that of negative control sample as it is expressed by equation 1:

| (1) |

Gelatin salt block test (eliminating false positive results)

In order to detect tannins, extracts with ≥ 50% ACE inhibition activity were tested under gelatin salt block test. Active extracts (200 mg) were dissolved in 4 ml water (50°C) and allowed to reach room temperature. To remove non-tannin compounds, a few drops of an aqueous 10% NaCl solution was added to the extracts. After filtration, the filtrate (1 ml) was added to four test tubes. Tube 1 contained 4–5 drops of 1% gelatin solution. Tube 2 contained 4–5 drops of 1% gelatin + 10% NaCl solution. Tube 3 contained 3–4 drops of 10% ferric chloride solution, and tube 4, was a control sample containing no reagent. Tube 1 and 2 were observed for the formation of precipitate, while tube 3 was observed for color [4].

The presence of greenish-blue or greenish-black color following the addition of ferric chloride indicates the presence of condensed tannins, and bluish-black color accounts for the presence of pyrogallol type tannins (assuming that precipitation is the result of gelatin salt block test). The presence of greenish-black or bluish-black color after the addition of ferric chloride with negative gelatin salt block test indicated no tannins in that extract.

Total phenolic content (TP)

Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method [11] was used to determine the total phenolic content of extracts. First, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (0.5 ml) was added to 0.5 ml of methanol extract solution (100 mg/ml). Then Na2CO3 (0.5 ml) (100 mg/ml) was added to the mixture. The absorbance was measured at 760 nm, after 60 min incubation at room temperature. Calibration curve of gallic acid in different concentrations (1, 10, 100, 500 and 1000 μg/ml) was prepared using the same method. Total phenolic content of each extract was calculated from calibration curve of gallic acid and reported as mg of gallic acid equivalent in 100 g dry of plant [12].

DPPH radical scavenging activity

The DPPH radical scavenging activity assay is a method for determining the ability of extracts to trap free radicals [13]. First, DPPH methanol solution (2.0 ml) (0.16 mM) was added to 2.0 ml of extract methanol solutions in different concentrations. Next the same sample was prepared with 2.0 ml methanol replacing extract methanol solution as control. After that the mixtures were vortexed for 1 min and left at room temperature for 30 min. Later the absorbance (Abs) were read at 517 nm. For calculating radical scavenging activity (RSA), the equation 2 was used:

| (2) |

Radical scavenging activity of extracts was compared with those of BHT and Trolox as the positive controls.

Establishing the sensitivity of the ACE assay system

The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of captopril was determined from concentration - response curve by nonlinear regression, using GraphPad Prism software version 5, and it was compared with the value in the literature. The IC50 value for captopril determined in this study was 25 ± 2.6 nM, which was close to the value (23 nM) in the literature [14].

Results

ACE inhibition activity

Table 1 illustrates scientific names, plant families, common names in Persian, parts used, collection sites, collection times, medicinal uses, voucher numbers and ACE inhibition activities of herbal extracts. Of a total of fifty herbal extracts, six extracts have shown inhibition activity more than 50% at 330 μg/ml concentration (Table 2). They were B. integerrima (88.2 ± 1.7%), C. microphylla (80.9 ± 1.3%), N. alba (66.3 ± 1.2%), O. acanthium (80.2 ± 2.0%), Q. infectoria (93.9 ± 2.5%) and Rubus sp. (51.3 ± 1.0%).

Table 1.

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition activity of the 50 studied plants*

| Scientific name and plant family | Common name in Persian | Part used | Collection site | Medicinal use | Voucher No | Inhibition% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abrus precatorius L. (Leguminosae) |

Cheshm- e Khorus |

Seed |

LHSa |

Tonic, astringent |

PMP - 725b |

-13.1 |

|

Alcea sp. (Malvaceae) |

Khatmi |

Flower |

LHS |

Diuretic, demulcent, disinfectant |

PMP - 503 |

-27.3 |

|

Allium cepa L. (Alliaceae) |

Tokhm- e pyaz |

Seed |

LHS |

Anti-typhoid fever |

PMP - 726 |

21.2 |

|

Amaranthus lividus L. (Amaranthaceae) |

Tokhm- e tajkhorus |

Seed |

LHS |

Treatment of anemia |

PMP - 723 |

-13.9 |

|

Amomum subulatum Roxb. (Zingiberaceae) |

Hel- e bad |

Fruit |

LHS |

Stomach tonic, carminative |

PMP - 634 |

-11.6 |

|

Arnebia euchroma (Royle) I. M. Johnst. (Boraginaceae) |

Havachobe |

Root |

LHS |

Disinfectant |

PMP - 211 |

-8.1 |

|

Artemisia sp. (Asteraceae) |

Afsantin |

Herb |

Ha |

Stomach tonic, increasing the appetite |

83004 |

-8.5 |

|

Berberis integerrima Bunge. (Berberidaceae) |

Zereshk- e abi |

Fruit |

LHS |

Tonic, laxative, refrigerant, antiseptic |

PMP - 619 |

88.2 ± 1.7c |

|

Biebersteinia sp. (Geraniaceae) |

Chelledaghi |

Root |

LHS |

Anti-rheumatic |

PMP - 215 |

22.7 |

|

Cerasus avium (L.) Moench (Rosaceae) |

Dom- e gilas |

Tail |

LHS |

Cardiac tonic, diuretic |

PMP - 309 |

28.4 |

|

Chelidonium majus L. (Papaveraceae) |

Mamiran |

Root |

LHS |

Anti-diarrhea, anti-liver disease |

PMP - 314 |

0.0 |

|

Cichorium intybus L. (Compositae) |

Kasni |

Root |

LHS |

Diuretic, analgesic, anti-fever |

PMP - 213 |

13.2 |

|

Colchicum sp. (Colchicaceae) |

Suranjan |

Rhizome |

LHS |

Anti-pain in gout |

PMP - 214 |

19.6 |

|

Commiphora sp. (Burseraceae) |

Moql |

Resin |

LHS |

Anti-rheumatic |

PMP - 812 |

20.8 |

|

Cordia myxa L. (Boraginaceae) |

Sepestan |

Fruit |

LHS |

Mucilage, anti-chest complaints |

PMP - 730 |

-15.9 |

|

Crataegus microphylla C. Koch (Rosaceae) |

Sorkhevalik |

Leaf |

LHS |

Cardiac tonic, diuretic, hypotensive |

PMP - 306 |

80.9 ± 1.3 |

|

Cucurbita pepo L. (Cucurbitaceae) |

Tokhm- e kadu |

Seed |

LHS |

Anti-fever, anti-gastrointestinal parasites |

PMP - 729 |

-31.5 |

|

Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. (Gramineae) |

Margh |

Rhizome |

LHS |

Diuretic |

PMP - 312 |

9.6 |

|

Datura stramonium L. (Solanaceae) |

Tature |

Leaf |

LHS |

Anti-asthma |

PMP - 728 |

22.3 |

|

Dorema ammoniacum Don. (Umbelliferae) |

Vasha |

Resin |

LHS |

Anti-gastrointestinal parasites |

PMP - 815 |

14.2 |

|

Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench (Asteraceae) |

Sarkhargol |

Aerial part |

H |

Anti-inflammatory, immune-stimulant |

84159 |

-50.4 |

|

Echinops sp. (Compositae) |

Shekartighal |

Resin |

LHS |

Demulcent, anti-cough, anti-fever |

PMP - 817 |

2.1 |

|

Elettaria cardamomum (L.) Maton (Zingiberaceae) |

Hel- e sabz |

Fruit |

LHS |

Spice, stomach tonic, carminative |

PMP - 630 |

-25.7 |

|

Entada rheedii Spreng. (Leguminosae) |

Qorc- e kamar |

Seed |

LHS |

Ointment for backache |

PMP - 724 |

17.3 |

|

Eugenia caryophyllata Thunb. (Myrtaceae) |

Mikhak |

Flower |

LHS |

Anti-dental pain, disinfectant |

PMP - 504 |

-34.4 |

|

Ferula asssa-foetida L. (Umbelliferae) |

Anqoze |

Resin |

LHS |

Anti-gastrointestinal parasites |

PMP - 816 |

-40.3 |

|

Ferula gumosa Boiss

.

(Umbelliferae) |

Barije |

Resin |

LHS |

Stomach tonic |

PMP - 814 |

-36.7 |

|

Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (Umbelliferae) |

Razyane |

Seed |

LHS |

Tonic, diuretic, carminative |

PMP - 632 |

-9.2 |

|

Heracleum persicum Desf. (Umbelliferae) |

Golpar |

Fruit |

LHS |

Spice, disinfectant, carminative |

PMP - 631 |

4.7 |

|

Iris sp. (Iridaceae) |

Rishe- e irisa |

Root |

LHS |

Diuretic, cathartic |

PMP - 212 |

0.0 |

|

Lepidium sativum L. (Cruciferae) |

Tokhm- e shahi |

Seed |

LHS |

Tonic |

PMP - 722 |

-2.2 |

|

Malva sylvestris L. (Malvaceae) |

Panirak |

Flower |

H |

Mucilage, anti-cough |

84450 |

21.7 |

|

Matricaria inodora L. (Asteraceae) |

Babuneh |

Flower |

H |

Carminative, febrifuge |

83452 |

-7.5 |

|

Nymphaea alba L. (Nymphaeaceae) |

Gol- e nilufar |

Flower |

LHS |

Diuretic, sedative |

PMP - 501 |

66.3 ± 1.2 |

|

Onopordon acanthium L. (Asteraceae) |

Khajebashi |

Seed |

LHS |

Hypotensive, diuretic, cardiac tonic |

PMP - 714 |

80.2 ± 2.0 |

|

Passiflora caerulea L. (Passifloraceae) |

Gol- e saati |

Flower |

H |

Spinal depressant, respiratory stimulant |

84568 |

-33.2 |

|

Plantago ovata Phil. (Plantaginaceae) |

Esfarze |

Seed |

LHS |

Laxative, anti-hemorrhoids |

PMP - 731 |

-24.2 |

|

Quercus infectoria G.Olivier. (Fagaceae) |

Jaft |

Bark |

LHS |

Anti-diarrhea, astringent, antibacterial |

PMP - 621 |

93.9 ± 2.5 |

|

Rosmarinus officinalis L. (Lamiaceae) |

Rosaemary |

Leaf |

H |

Spice, herb, carminative, GI irritant |

83636 |

0.0 |

|

Rubus sp. (Rosaceae) |

Tameshk |

Leaf |

Na |

Hypotensive, anti-diarrhea |

PMP - 404 |

51.3 ± 1.0 |

|

Salvia macrosiphon Boiss. (Labiatae) |

Tokhm- e marv |

Seed |

LHS |

Demulcent, anti-cough |

PMP - 721 |

-11.7 |

|

Saponaria officinalis L. (Caryophyllaceae) |

Gol- e sabooni |

Flower |

H |

Expectorant, laxative |

84680 |

-33.6 |

|

Satureja hortensis L. (Labiatae) |

Tokhm- e marze |

Seed |

LHS |

Anti-muscle pain, anti-rheumatic |

PMP - 732 |

34.4 |

|

Tanacetum Balsamita L. (Compositae) |

Shahesparam |

Leaf |

LHS |

Stomach tonic, anti-nausea |

PMP - 405 |

-15.2 |

|

Terminalia chebula Retz. (Combretaceae) |

Halil- e zard |

Fruit |

LHS |

Stomach tonic, anti-diarrhea |

PMP - 633 |

17.9 |

|

Terminalia chebula Retz. (Combretaceae) |

Halil- e siah |

Fruit |

LHS |

Cathartic |

PMP - 629 |

15.2 |

|

Teucrium polium L. (Labiatae) |

Maryam nokhodi |

Aerial part |

LHS |

Cold treatment, anti-fever |

PMP - 313 |

2.1 |

|

Vitex agnus-castus L. (Verbenaceae) |

Panj anghosht |

Flower |

H |

Anti-androgen, carminative |

84802 |

31.4 |

|

Zataria multiflora Boiss. (Labiatae) |

Avishan- e shirazi |

Leaf |

LHS |

Cold treatment, carminative |

PMP - 310 |

24.8 |

| Zea mays L. (Gramineae) | Kakol- e zhorrat | Herb | LHS | Diuretic, urethra antiseptic | PMP - 311 | -35.7 |

*All medicinal plants were collected in June 2011 except Rubus sp. which is collected in June 2012.

aLHS, Local Herbal Store; H, Herburatum of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (http://pharmacy.tums.ac.ir); N, North of Iran (Mazandaran province).

bPMP, Popular Medicinal Plant.

cValues are means ± SD of three measurements for 6 active plants.

Table 2.

The active medicinal plants with more than 50% ACE inhibition activity at 330 μg/ml concentration

| Scientific name | Percent of inhibition a |

|---|---|

|

B. integerrima |

88.2 ± 1.7 |

|

C. microphylla |

80.9 ± 1.3 |

|

N. alba |

66.3 ± 1.2 |

|

O. acanthium |

80.2 ± 2.0 |

|

Q. infectoria |

93.9 ± 2.5 |

| Rubus sp. | 51.3 ± 1.0 |

aValues are means ± SD of three measurements.

Tannin test

Out of six active extracts investigated in this study, only the extract of Q. infectoria produced a positive gelatin salt block test (Table 3). The presence of greenish-black or bluish-black color after the addition of ferric chloride with negative gelatin salt block test indicated no tannins in other extracts.

Table 3.

Results of gelatin salt block test in order to detect tannin in extracts

| Scientific name | 1% Gelatin | 1% gelatin + 10% NaCl | Ferric chloride |

|---|---|---|---|

|

B. integerrima |

NPa |

NP |

Green/black |

|

C. microphylla |

NP |

NP |

Green/black |

|

N. alba |

NP |

NP |

Blue/black |

|

O. acanthium |

NP |

NP |

Green/black |

|

Q. infectoria |

Pb |

P |

Green/black |

| Rubus sp. | NP | NP | Blue/black |

aNP, no precipitate; bP, precipitate.

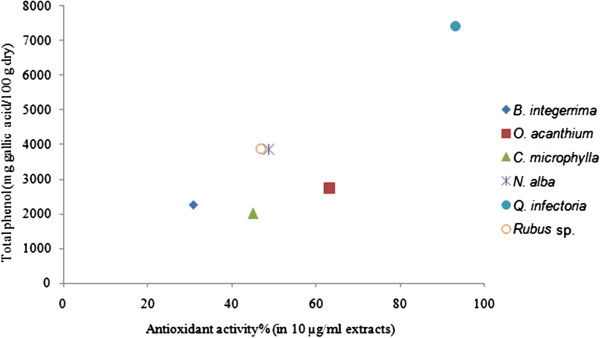

Total phenolic content and radical scavenging activity

Oxidative stress plays a critical role in cardiovascular disease [15]. Phenolic compounds are responsible for antioxidant activity due to their ability for scavenging free radicals. Therefore, total phenolic content and radical scavenging activities of these six medicinal plants were determined (Table 4). Most of these six extracts had a large phenolic content. In DPPH radical scavenging assay, IC50 values of six plant extracts were determined and compared with those of BHT and Trolox as the positive controls (Table 4). Q. infectoria possessed more antioxidant activity (IC50 value of 1.7 ± 0.03 μg/ml), compared to that of BHT (IC50 value of 10.3 ± 0.15 μg/ml) and Trolox (IC50 value of 3.2 ± 0.06 μg/ml).

Table 4.

Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of active extracts

| Scientific name | Tp a (mg gallic acid/100 g dry plant) | IC 50 b (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

|

B. integerrima |

2250 ± 37 |

15.3 ± 0.20 |

|

C. microphylla |

2000 ± 29 |

13.1 ± 0.20 |

|

N. alba |

3860 ± 36 |

10.2 ± 0.15 |

|

O. acanthium |

2740 ± 26 |

7.0 ± 0.09 |

|

Q. infectoria |

7410 ± 101 |

1.7 ± 0.03 |

|

Rubus sp. |

3870 ± 26 |

11.3 ± 0.22 |

| BHT |

_ |

10.3 ± 0.15 |

| Trolox | _ | 3.2 ± 0.06 |

aTp, Total phenolic content.

bIC50, radical scavenging activity in DPPH assay.

Values are means ± SD of three independent measurements.

Discussion

Hypertension, a worldwide illness, is a major factor in cardiovascular diseases that affects a large population of adults. One of the most effective medications for the treatment of hypertension is angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Meanwhile, medicinal plants have been used for treating illnesses. Therefore, they can be important resources to develop new drug candidates [16].

As illustrated in Table 1 six extracts showed inhibition activity more than 50%, nineteen extracts showed inhibition activity less than 50% and 25 of them showed no inhibition activity at 330 μg/ml concentration. Among these active medicinal plants, three ones (C. microphylla, O. acanthium and Rubus sp.) are utilized for the treatment of hypertension in traditional medicine and this research revealed that the mechanism of action of the three mentioned plants in treatment of hypertension could be done through ACE inhibition.

In addition, Antihypertensive activity is reported in traditional medicine for similar species of the above mentioned plants including Crataegus oxyacantha[17], Onopordon leptolepis and Onopordon carmanicum[18].

Flavonoids [19], flavanols [20], flavonols [21], anthocyanins [22], isoflavones [23], flavones [24] and other phenolic compounds have proved to be effective in decreasing the ACE activity. Therefore, the above mentioned secondary metabolites could be responsible for ACE inhibition activity in these 6 active extracts.

On the other hand, such ACE inhibitors with antioxidant activity might be useful to treat other diseases which are caused as a result of a rise in ROS production [25].

The highest ACE inhibition activity (93.9 ± 2.5%) was observed at 330 μg/ml concentration in Q. infectoria. It is clear that tannins are phenolic natural products that interfere in enzymatic activity. Consequently, we checked for its presence in our active extracts (extracts with ≥ 50% ACE inhibition activity). Unfortunately, greenish-black color after the addition of ferric chloride with positive gelatin salt block test indicated the presence of condensed tannins in Q. infectoria extract. Therefore, in spite of high ACE inhibition and antioxidant activity, it is not the plant of choice for further studies to isolate the active compounds.

Among other active medicinal plants, three ones including B. integerrima, C. microphylla and O. acanthium possessed > 80% ACE inhibition activity. Out of the three mentioned plants, O. acanthium possessed more antioxidant activity (IC50 value of 7 ± 0.09 μg/ml), compared to that of B. integerrima (IC50 value of 15.3 ± 0.2 μg/ml) and C. microphylla (IC50 value of 13.1 ± 0.2 μg/ml). Therefore, because of high ACE inhibition and antioxidant activity, O. acanthium is a valuable medicinal plant for isolation of active compounds.

Furthermore, N. alba and Rubus sp. are moderate ACE inhibitors and after the above three mentioned plants, are valuable plants for isolation of active compounds in further studies.

Conclusions

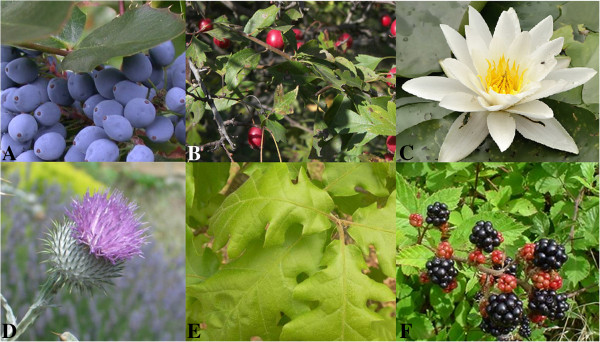

Medicinal plants presented in Table 2 are potential sources for developing new ACE inhibitors (Figure 1) [26-31]. There was a linear relationship between total phenolic content and radical scavenging activity with equation formula, y = 83.53 × - 823.4; R2 = 0.714 (Figure 2). As shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4, in spite of possessing the highest ACE inhibition and antioxidant activity, Q. infectoria had tannin content. On the other hand, O. acanthium, which also had high ACE inhibition and antioxidant activity containing no tannin, and could be used in further studies for isolation of active compounds.

Figure 1.

The picture of active medicinal plants with more than 50% angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory activity. A)B. integerrimaB)C. microphyllaC)N. albaD)O. acanthiumE)Q. infectoriaF)Rubus sp [26-31].

Figure 2.

The correlation between total phenolic content and DPPH radical scavenging activity for six plant extracts.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Authors’ contributions

NS: Performed the experimental work including plant extraction, biological tests, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation. ES: Was responsible for HPLC analysis. SAZ: Was involved in designing the experiments. GHA: Identified all plants. MA: Was responsible for the study registration, financial and administrative support, and also gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Niusha Sharifi, Email: ni_sharifi@razi.tums.ac.ir.

Effat Souri, Email: souri@sina.tums.ac.ir.

Seyed Ali Ziai, Email: saziai@gmail.com.

Gholamreza Amin, Email: amin@tums.ac.ir.

Massoud Amanlou, Email: amanlou@tums.ac.ir.

Acknowledgment

The financial support of the Research Council of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;21:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeggs SLT, Kahn JR, Shumway NP. The preparation and function of the angiotensin I converting enzyme. J Exp Med. 1956;21:295–299. doi: 10.1084/jem.103.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero OA, Oparil S. Essential hypertension.Part I: definition and etiology. Circulation. 2000;21:329–335. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AC, Jager AK, Staden JV. Screening of Zulu medicinal plants for angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;21:63–70. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griendling KK, Candace A, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1994;21:1141–1148. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.74.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchmeshky A, Jameie SB, Amin G, Ziai SA. Investigation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory effects of medicinal plants used in traditional Persian medicine for treatment of hypertension, screening study. Thrita Stud J Med Sci. 2012;21:13–23. doi: 10.5812/Thrita.4264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M, Fujimura K, Terashima T, Iso T. Method for determination of angiotensin converting enzyme activity in blood and tissue by high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1982;21:123–130. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(00)81738-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehanna AS, Dowling M. Liquid chromatographic determination of hippuric acid for the evaluation of ethacrynic acid as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1999;21:967–973. doi: 10.1016/S0731-7085(98)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaith E, Beyrau R, Buckner B, Klein RM, Rick W. Optimized determination of angiotensin I converting enzyme activity with hippuril-L-histidyl-L-leucine as substrate. Clin Chim Acta. 1994;21:145–158. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tundis R, Loizzo MR, Statti GA, Deguin B, Amissah R, Houghton PJ. et al. Chemical composition of and inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme by Senecio samnitum huet. Pharm Biol. 2005;21:605–608. doi: 10.1080/13880200500301886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;21:152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman J, Hamouz K, Orsak M, Pivec V. Potato tubers as a significant source of antioxidant human nutrition. Rostl Vyr. 2000;21:231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Yen GC, Chen HY. Antioxidant activity of various tea extracts in relation to their antimutagenicity. J Agric Food Chem. 1995;21:27–37. doi: 10.1021/jf00049a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ondetti MA. Structural relationships of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors to pharmacologic activity. Circulation. 1988;21:74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla NS, Temsah RM, Netticadan T. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. J Hypertens. 2000;21:655–673. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp FJ. The efficacy, history, and politics of medicinal plants. Altern Ther Health Med. 1996;21:36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacaille-Dubois MA, Franck U, Wagner H. Search for potential Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE)-inhibitors from plants. Phytomedicine. 2001;21:47–52. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili A, Saremnia B. Preparation of extract-loaded nanocapsules from Onopordon leptolepis DC. Ind Crop Prod. 2012;21:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda D, Jiménez-Ferrer E, Zamilpa A, Herrera-Arellano A, Tortoriello J, Alvarez L. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) activity by the anthocyanins delphinidin- and cyanidin-3-O-sambubiosides from Hibiscus sabdariffa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;21:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani JI, Actis-Goretta L, Villordo JJ, Fraga CG. Procyanidin structure defines the extent and specificity of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibition. Biochimie. 2006;21:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Kang DG, Kwon JW, Kwon TO, Lee SY, Lee DB. et al. Isolation of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory flavonoids from Sedum sarmentosum. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;21:2035–2037. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon EK, Lee DY, Lee H, Kim DO, Baek NI, Kim YE. et al. Flavonoids from the buds of Rosa damascena inhibit the activity of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase and angiotensin I-converting enzyme. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;21:882–886. doi: 10.1021/jf903515f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro MF, Pessa LR, Tanus-Santos JE. Isoflavone genistein inhibits the angiotensin converting enzyme and alters the vascular responses to angiotensin I and bradykinin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;21:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loizzo MR, Said A, Tundis R, Rashed K, Statti GA, Hufner A. et al. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) by flavonoids isolated from Ailanthus excels (Roxb) (Simaroubaceae) Phytother Res. 2007;21:32–36. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasani-Ranjbar S, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of the potential herbal sources of future drugs effective in oxidant-related diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2009;21:2–10. doi: 10.2174/187152809787582561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberis integerrima. http://www.plantsystematics.org/imgs/kcn2/r/Berberidaceae_Berberis_sp_1445.html.webcite (accessed September 6, 2013)

- Crategus microphylla. http://www.plantarium.ru/page/image/id/155248.html.webcite (accessed September 6, 2013)

- Wikipedia contributors. Nymphaea alba. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nymphaea_alba.webcite (accessed September 6, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia contributors. Ononpordum acanthium. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onopordum_acanthium webcite (accessed September 6, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Quercus infectoria. http://www.biolib.cz/en/taxonimage/id77341 webcite (Pavel Bursik). (accessed September 6, 2013)

- Wikipedia contributors. Rubus sp. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubus webcite (accessed September 6, 2013) [Google Scholar]