Abstract

Objective

To describe the distribution of cardiovascular risk factors in western Kenya using a Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS).

Design

Population-based survey of residents in an HDSS

Setting

Webuye Division in Bungoma East District, Western Province of Kenya

Patients

4037 adults ≥18 years of age

Interventions

Home-based survey using the World Health Organization STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance

Main outcome measures

Self-report of high blood pressure, high blood sugar, tobacco use, alcohol use, physical activity and fruit/vegetable intake

Results

The median age of the population was 35 years (IQR: 26–50). Less than 6% of the population reported high blood pressure or blood sugar. Tobacco and alcohol use were reported in 7% and 16% of the population, respectively. The majority of the population (93%) was physically active. The average number of days per week that participants reported intake of fruits (3.1 +/− 0.1) or vegetables (1.6 +/− 0.1) was low. In multiple logistic regression analyses, women were more likely to report a history of high blood pressure (OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.9–3.9), less likely to report using tobacco (OR 0.08, 95% CI 0.06–0.11), less likely to report alcohol use (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.15–0.21) or eat ≥5 servings per day of fruits or vegetables (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76–0.99) compared to men.

Conclusions

The most common cardiovascular risk factors in peri-urban western Kenya are tobacco use, alcohol use and inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables. Our data reveal locally-relevant sub-group differences that could inform future prevention efforts.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, risk factors, Kenya, demography, sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

Of the 52.8 million deaths worldwide in 2010, roughly 65% were due to chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) affecting most regions of the world.[1] Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in all developing regions with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where infectious diseases account for the greatest burden.[1, 2] While a low background prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors may be a cause of this difference, other factors such as limited data, lack of population surveillance efforts and relative inattention to NCDs in the region must also be considered. Having population-based estimates of cardiovascular risk factors is crucial to understanding the distribution and types of risk factors present in the region and for policy and planning to address the burden of CVD.[3, 4] Such population data on cardiovascular disease risk factors are sorely lacking in sub-Saharan Africa.[5] The few data that do exist from Kenya suggests that hypertension and myocardial infarction are increasingly common and often related to higher socioeconomic status.[6, 7, 8]. Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems (HDSSs) have been established in nearly two-dozen countries as platforms to monitor population dynamics and are linked via the International Network of field sites for continuous Demographic Evaluation of Populations and Their Health in developing countries (www.indepth-network.org). An HDSS collects longitudinal, population-based health and vital event information and monitors demographic and health events in a geographically defined population. Many HDSS sites have demonstrated utility in describing cardiovascular risk factor patterns in many LMICs.[9, 10] By using standardized instruments, population-level data obtained from HDSS activities can inform local policy and be compared across regions. Our aim was to describe the distribution of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in a peri-urban population in western Kenya using an existing HDSS platform.[11]

METHODS

Study setting

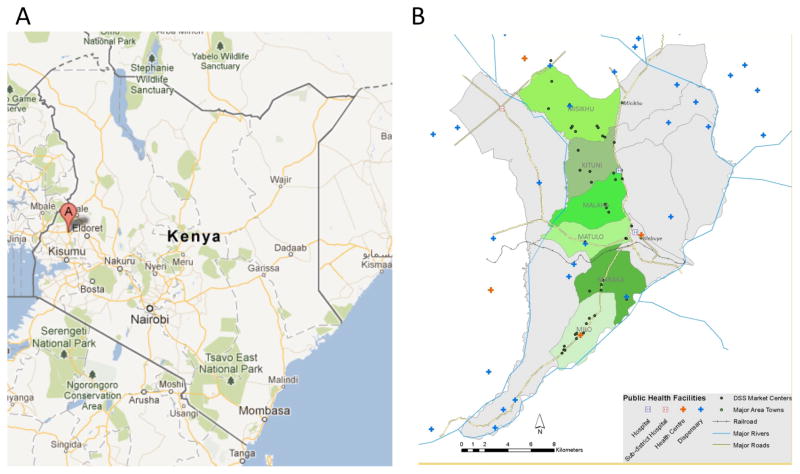

On a national level, the mean life expectancy for Kenyans was 58.9 years in 2009. The infant mortality rate was 52 per 1 000 births and the country was 21% urban.[12] There has been a demographic transition as evidence by increasing population size, life expectancy, percent of population in urban settings alongside decreasing fertility, infant mortality and birth rates over the last 40 years.[12] This study was conducted within the Webuye HDSS site between March and July 2010. The characteristics and management of the HDSS have been previously described.[11] The Webuye Division in Bungoma East District, Western Province of Kenya is approximately 400km west of Nairobi and 40 km from the Kenya-Uganda border. The HDSS population of 77 000 individuals resides in approximately 13 500 households in 6 sub-locations (Figure 1). Farming is the main economic activity. Sugar cane as the main cash crop while maize, beans, millet and sorghum are grown for subsistence. Small-scale dairy and poultry farming is widely practiced. A paper factory and chemical processing plant are located in the adjacent area. Basic facilities like clean water, sanitation and electricity are not available to the majority of the residents. The traditions of this area are such women are not expected to smoke tobacco or drink alcohol to the same degree as men. The most commonly used tobacco and alcohol products are manufactured and homemade, respectively. The community’s drinking pattern is that alcohol is usually consumed during ceremonies (i.e., weddings, circumcision) and after harvest season. The legal age for smoking and drinking alcohol is above 18 years.

Figure 1.

Map of the Webuye Health and Demographic Surveillance System Area

A: Map of the Republic of Kenya with Bungoma District shown by Point A. B: Map of the Webuye Health and Demographic Surveillance System (WHDSS) catchment area illustrating the six sub-locations and major public health facilities. The WHDSS is located in Bungoma District (Point A from Figure 1A). Map courtesy of GoogleMaps © 2012 Google

Study population and design

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study of the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among the adult (≥18 years) residents within the Webuye HDSS. Administration of the survey occurred during a routine data collection phase of the HDSS. Stratified random sampling was used to select the individuals stratified by sub-location and village. Proportionate sampling was used to assign quotas to each sub-location and village based on its population. Individuals were randomly selected from the two clusters of males and females per sub-location and village. A total of 4400 participants were sampled from a sampling frame of 39,829 individuals residing in the study area who were 18 years old and above at the time of the study. Three hundred and eight (308) of these participants could not be contacted because they were either away in school/college or had moved out of the study area at the time of the study. None of the individuals selected refused to participate in the study. Questionnaires were administered in each participant’s home using paper forms. The participant completed the questionnaire with the assistance of field assistants. Several attempts were made to contact residents who were not at home during the initial home visit. Non-residents of the community during the study period would not have been able to participate.

Study instruments and data collection

The data collection was conducted using the a World Health Organization STEPwise approach (STEPs) to chronic disease risk factor surveillance.[13] Some existing questions were modified and new questions designed to reflect the local situation after a field-testing. The questionnaire was administered in English, Kiswahili or Bukusu. All risk factor data was self-reported. Tobacco use was recorded as ever daily, currently daily (within the last 30 days) or currently but not daily. Alcohol drinking was recorded as lifetime abstainer, current (within the last 30 days) and not current (within the last 12 months but not the last 30 days). Vigorous physical activity for work was defined as carrying or lifting heavy loads, digging or construction work for 10 minutes continuously. Physical activity for travel was defined as walking or using a bicycle for at least 10 minutes to get to and from places. Leisure time physical activity was defined as engaging in sports, fitness or recreation for at least 10 minutes continuously. Fruit and vegetable consumption was recorded in terms of number of servings per day and number of days per week. Adequate fruit and vegetable intake was defined as consuming five or more servings of fruits or vegetables per day.[14] Our main independent variables were self-reported high blood pressure, high blood sugar, tobacco use, alcohol, physical activity and adequate fruit and vegetables consumption.

Field assistants received classroom and field-based training to optimize uniform understanding and accurate completion of questionnaires. At the end of the training, each field assistant achieved certification in human subjects protection. During pilot testing, it became apparent that the questions on vegetable consumption might not be capturing nutritional vegetable intake due to local descriptions of vegetables and cooking habits. We restricted the criteria for vegetable consumption to be based on vegetables that were cooked for ≤ 5 minutes.

Data management and cleaning

Completed questionnaires went through a series of checks in the field, field office and by automated internal consistency checks. Flagged questionnaires were returned back to the respective field assistants for correction. Before data cleaning, the sample included 4092 observations. Duplicate entries, observations with missing data elements, abnormal skip patterns, outliers and impossible values were reconciled with the paper questionnaires and were either corrected in the most logical way or excluded from the analysis. After data cleaning, there were 4037 participant questionnaires included for analysis.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 10.0. Descriptive statistics were used for continuous variables using mean, median, standard deviation and inter-quartile range (IQR). Frequency listings and percentages were used for categorical variables. To assess whether there were any associations between the outcomes of interest and the independent variables multiple logistic regression models were used. In all the analyses we provided the 95% confidence intervals. For the logistic regression model a significance level of 5% was considered statistically significant.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of Moi University and Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, the Webuye HDSS site authorities, community chiefs, assistant chiefs, and village elders from the study area. Written consent was obtained from each respondent.

RESULTS

Fifty-five of 4092 surveys (1.3%) were excluded from the analysis due to missing or incorrect data. Of the 4037 adults included in the analysis, 61% (2475) were women. Demographic characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1. The median (IQR) age of the population was 35 (26–50) years. Primary education was the highest education level for >50% of the participants with lower proportions reporting completing secondary (30%), technical (4%) or higher education (2%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Both sexes (n=4037) | Male (n= 1562) | Female (n=2475) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age category (years) | ||||||

| 16–24 | 828 | 20.51 | 352 | 22.54 | 476 | 19.23 |

| 25–34 | 1117 | 27.67 | 392 | 25.10 | 725 | 29.29 |

| 35–44 | 741 | 18.36 | 266 | 17.03 | 475 | 19.19 |

| 45–54 | 573 | 14.19 | 221 | 14.15 | 352 | 14.22 |

| 55–64 | 391 | 9.69 | 158 | 10.12 | 233 | 9.41 |

| >64 | 387 | 9.59 | 173 | 11.08 | 214 | 8.65 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never | 576 | 14.27 | 343 | 21.96 | 233 | 9.42 |

| Currently married | 2978 | 73.79 | 1144 | 73.24 | 1834 | 74.13 |

| Separated/Divorced | 107 | 2.65 | 32 | 2.05 | 75 | 3.03 |

| Widowed | 337 | 8.35 | 31 | 1.98 | 306 | 12.37 |

| Other | 38 | 0.94 | 12 | 0.77 | 26 | 1.05 |

| Education | ||||||

| None | 167 | 4.14 | 23 | 1.47 | 144 | 5.82 |

| Primary | 2421 | 59.99 | 847 | 54.23 | 1574 | 63.62 |

| Secondary | 1214 | 30.08 | 569 | 36.43 | 645 | 26.07 |

| Technical* | 155 | 3.84 | 81 | 5.19 | 74 | 2.99 |

| Higher | 79 | 1.96 | 42 | 2.69 | 37 | 1.50 |

| Type of work | ||||||

| Employed | 290 | 7.19 | 206 | 13.19 | 84 | 3.40 |

| Self Employed | 2520 | 62.44 | 893 | 57.17 | 1627 | 65.76 |

| Unemployed | 1153 | 28.57 | 432 | 27.66 | 721 | 29.14 |

| Not applicable | 71 | 1.76 | 29 | 1.86 | 42 | 1.70 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.05 |

Technical education includes vocational and informal

High blood pressure was reported in 3% of men and 6% of women (Table 2). The rate of taking medication for high blood pressure was lower than the rate of high blood pressure for both sexes (1% among men, 2% among women). The reported rates of having high blood sugar were less than 1% for both sexes.

Table 2.

Burden of selected non-communicable disease risk factors

| Risk factor | Both sexes | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | 95% CI or IQR | n | % | 95% CI or IQR | n | % | 95% CI or IQR | |

| Raised blood pressure | 197 | 4.88 | (4–6) | 42 | 2.7 | (1.9–3.6) | 155 | 6.3 | (5.3–7.3) |

| Raised blood pressure on medication | 69 | 1.71 | (1.3–2.1) | 15 | 0.96 | (0.5–1.6) | 54 | 2.18 | (1.6–2.8) |

| Raised blood sugar on medications | 16 | 0.40 | (0.2–0.6) | 8 | 0.51 | (0.2–1.0) | 8 | 0.32 | (0.1–0.6) |

| Tobacco smoking | |||||||||

| Ever daily | 263 | 6.63 | (5.9–7.4) | 213 | 14.05 | (12–16) | 50 | 2.05 | (1–3) |

| Current daily | 162 | 4.09 | (3.5–4.7) | 145 | 9.53 | (8–11) | 17 | 0.7 | (0.1–1) |

| Current non-daily | 49 | 1.24 | (0.9–1.6) | 38 | 2.5 | (2, 3) | 11 | 0.45 | (0.2–0.7) |

| Smokeless tobacco | |||||||||

| Ever daily | 170 | 4.26 | (3.6–4.9) | 132 | 8.61 | (7–10) | 38 | 1.55 | (1–2) |

| Current daily | 111 | 2.82 | (2.3–3.3) | 103 | 6.84 | (6–8) | 8 | 0.33 | (0.1–0.6) |

| Current non-daily | 41 | 1.04 | (0.7–1.4) | 35 | 2.33 | (2–3) | 6 | 0.25 | (0.1–0.4) |

| Alcohol drinking | |||||||||

| Abstainer | 3138 | 78.49 | (77.2–79.8) | 955 | 62.01 | (59.6–64.4) | 2183 | 88.81) | (87.6–90.1 |

| Last 12 months | 210 | 5.25 | (4.6–5.9) | 105 | 6.82 | (5.5–8.1) | 105 | 4.21 | (3.5–5.1) |

| Current (w/in 30 days) | 650 | 16.26 | (15.11–17.40) | 480 | 31.17 | (28.9–33.5) | 170 | 6.93 | (5.9–7.9) |

| Physical Activity | |||||||||

| At work | 3702 | 92.53 | (91.7–93.3) | 1426 | 92.48 | (91–94) | 2276 | 92.56 | (91–94) |

| For recreation | 1156 | 28.93 | (27.5–30.3) | 592 | 38.39 | (36–41) | 564 | 22.97 | (21–25) |

| For travel | 3826 | 95.75 | (95.1–96.4) | 1502 | 97.47 | (97–98) | 2324 | 94.66 | (94–96) |

| Sedentary minutes/day | 126 | n/a | (122–129)* | 138 | n/a | 132–144 | 118 | n/a | (114–123)* |

| Fruit consumption | |||||||||

| 7 days per week | 645 | 16.3 | (15.1–17.4) | 266 | 14.8 | (13–17) | 419 | 17.3 | (16–19) |

| Days per week | 3.1 | n/a | (3.1–3.2)* | 2.9 | n/a | (2.8–3.1)* | 3.2 | n/a | (3.1–3.3)* |

| Servings per day | 1.8 | n/a | (1.7–1.9)* | 1.8 | n/a | (1.7–1.9)* | 1.8 | n/a | (1.7–1.9)* |

| Vegetable consumption | |||||||||

| 7 days per week | 53 | 1.67 | (1.2–2.1) | 26 | 2.1 | (1.3–2.9) | 27 | 1.4 | (0.9–1.9) |

| Days per week | 1.6 | n/a | (1.5–1.6)* | 1.6 | n/a | (1.5–1.7)* | 1.5 | n/a | (1.5–1.6)* |

| Servings per day | 6.8 | n/a | (6.7–7.0)* | 6.7 | n/a | (6.5–7.0)* | 6.9 | n/a | (6.7–7.1)* |

denotes interquartile range (IQR)

Only 7% of the population reported ever smoking tobacco on a daily basis with more men than women (14% vs. 2%, respectively). Ten percent of men and less than 1% of women were currently smoking tobacco on a daily basis. Use of smokeless tobacco was generally less common than smoking tobacco but still more common among men (Table 2). Over 60% of men and 80% of women reported lifetime abstinence from alcohol consumption. Approximately 30% of men reported current (within the last 30 days) alcohol use.

Vigorous physical activity for work, travel or leisure was reported for >90% of the population. Most participants reported vigorous physical activity at work (93%) or during travel (96%). A relatively smaller proportion of individuals (38% of men and 23% of women) reported physical activity for recreation. The median number of minutes per day spent sedentary was 126 (IQR: 122–129).

A small proportion of participants (16%) reported eating fruits daily. The average (SD) number of days per week that participants reported eating any fruits was 3.1 (±0.1) with an average of 1.8 (±0.1) servings per day. Only 2% of participants reported eating vegetables every day of the week. The average (SD) number of days reported for eating any vegetables was 1.6 (±0.1) with a median of 6.8 (±0.1) servings per day.

Table 3 shows the results of our logistic regression analysis for associations between the non-communicable disease risk factors and demographic variables. High blood pressure was more commonly reported among women compared to men (OR 2.72 95% CI 1.9–3.9, p<0.001) and among older age groups compared to the younger. Reporting high blood sugar was rare but more common among older participants with a wide range for the 95% confidence intervals for the estimate of the odds.

Table 3.

Results of Logistic Regression Analysis for Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors

| Variables | High blood pressure | High blood sugar | Tobacco use | Alcohol use | Physical Activity | Fruit and Vegetable use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Female | 2.72 | 1.90–3.90 | 1.31 | 0.63–2.74 | 0.08 | 0.06–0.11 | 0.18 | 0.15–0.21 | 0.86 | 0.56–1.33 | 0.87 | 0.76–0.99 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 16–24 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| 25–34 | 1.23 | 0.65–2.35 | 1.22 | 0.29–5.13 | 3.49 | 2.14–5.72 | 2.01 | 1.55–2.62 | 1.43 | 0.72–2.86 | 1.22 | 1.01–1.48 |

| 35–44 | 2.92 | 1.59–5.35 | 0.74 | 0.12–4.42 | 5.68 | 3.46–9.33 | 2.51 | 1.90–3.32 | 2.24 | 0.92–5.43 | 1.41 | 1.14–1.73 |

| 45–54 | 4.77 | 2.63–8.66 | 3.98 | 1.05–15.08 | 8.67 | 5.28–14.23 | 2.68 | 2.00–3.81 | 1.04 | 0.49–2.20 | 1.52 | 1.22–1.90 |

| 55–64 | 5.89 | 3.16–11.0 | 6.29 | 1.64–24.07 | 5.58 | 3.26–9.54 | 2.77 | 2.01–3.81 | 0.96 | 0.42–2.15 | 1.07 | 0.82–1.38 |

| >64 | 6.18 | 3.25–11.75 | 6.24 | 1.55–25.13 | 5.29 | 3.09–9.03 | 1.92 | 1.37–2.68 | 0.24 | 0.13–0.45 | 1.19 | 0.91–1.55 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| None | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||

| Primary | 1.32 | 0.76–2.48 | 3.10 | 0.40–24.22 | 0.26 | 0.16–0.44 | 0.72 | 0.48–1.09 | 3.35 | 1.86–6.05 | 0.90 | 0.64–1.26 |

| Secondary | 1.65 | 0.83–3.26 | 4.00 | 0.47–34.32 | 0.21 | 0.12–0.36 | 0.45 | 0.29–0.70 | 3.44 | 1.65–7.18 | 0.73 | 0.51–1.04 |

| Technical | 2.22 | 0.94–5.25 | 4.30 | 0.37–49.39 | 0.21 | 0.10–0.44 | 0.39 | 0.22–0.70 | 1.97 | 0.78–4.95 | 0.52 | 0.32–0.84 |

| Higher | 1.49 | 0.40–5.62 | -- | 0.23 | 0.09–0.57 | 0.55 | 0.27–1.11 | 1.27 | 0.40–4.11 | 0.72 | 0.40–1.27 | |

--; there were no participants meeting these criteria

Women were 92% less likely to report using tobacco than men (OR 0.08 95% CI 0.06–0.11, p<0.001) and were also less likely to report alcohol use (OR 0.18 95% CI 0.15–0.21 p<0.001) or have ≥5 servings per day of fruits or vegetables (OR 0.87 95% CI 0.76–0.99). Both alcohol and tobacco use were more likely among those 45–54 years (OR 8.67, 95% CI 5.28–14.23) compared to 18–24 year olds. Adequate fruit/vegetable intake was more common among those 25–54 years compared to those <24 years old. A history of alcohol use was approximately two-fold greater for participants 25 years or older compared to those <24 years (Table 3). Participants with a formal education were 79% less likely (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.12–0.36) to report tobacco smoking than those without formal education. Those with a primary or secondary education reported significantly more physical activity (primary education OR 3.35, 95% CI 1.86–6.05; secondary education OR 3.44, 95% CI 1.65–7.18) compared to those without formal education. There were more men than women with ≥2 cardiovascular risk factors within each age category (Figure 2 online supplemental material). Men in the 45–54 years age range and women >64 years accounted for the greatest proportion of those with ≥2 cardiovascular risk factors (52% and 36%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The few data on cardiovascular risk factors in SSA are based on studies from a small number of countries.[15, 16] Although chronic cardiovascular diseases have been reported in necropsy reports from Kenya since the 1930s, the country is also thought to be in the midst of significant epidemiologic transition currently.[6, 7, 8, 17] This study, therefore, fills a clear gap in the literature with regard to community-based cardiovascular risk factor data from a country in SSA that has been underrepresented in this field. By using a standard approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance in this regional HDSS we have made several observations regarding the relative burden and distribution of cardiovascular risk factors in western Kenya. First, we found a moderate prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors with 24% of the population having at least two. Second, tobacco and alcohol use are more common among older men and those with less education. Third, adequate fruit and vegetable intake is a rarity. Fourth, adults in rural western Kenya are physically active mostly for work and travel with little recreational activity. Lastly, self-report of high blood pressure is low and self-report of high blood sugar is rare in this population. A benefit of the current approach is the comparability with studies using the same instrument.

Patterns of tobacco use

Tobacco use patterns across SSA are varied. Surveys using STEPs across SSA demonstrate that rates of current use of tobacco ranges from <5% (e.g., Niger) to >16% (e.g., Seychelles).[18, 19] The rates of current smoking among men are usually 10 times higher than women. The rates we currently report are most similar to those reported in Niger (4.6%), Zambia (6.5%) and São Tomé and Principe (5.5%).[19] We have also shown that the rate of using smokeless tobacco products is only slighter lower than smoking rates suggesting that attention to both forms of harmful tobacco use are prevalent. Though rates of tobacco use are generally low among adults in Kenya,[20] the worldwide smoking prevalence is increasing in LMICs (2% annual prevalence increase) and the increase is higher in SSA (3.2%) highlighting the importance of this cardiovascular risk factor.[21]

Patterns of alcohol use

With few exceptions, the overall rate of alcohol use in western Kenya is lower than reported in other African countries using the WHO STEPwise instrument. Our rates of alcohol abstinence for men and women (62% and 88%, respectively) are higher than most countries in SSA except for Swaziland (75% and 94%), Tanzania (Zanzibar) (84% and 97%) and Niger (99% and 99%).[19] Factors contributing to these differences include financial resources, social and religious norms, the legal drinking age and communal drinking patterns. However, the rate of current drinking in western Kenya was high among men. Thirty-one percent (31%) of men reported drinking alcohol within the last 30 days and this rate is similar to men in many SSA countries. Alcohol use appears to be an important chronic disease factor for men, older persons and, to a lesser degree, those without formal education in the present analysis.

Pattern of fruit and vegetable consumption

Daily fruit and vegetable intake of at least 5 servings (400g) per day is recommended for the prevention of chronic diseases.[14] Inadequate consumption, however, is most commonly seen in many countries in SSA,[22] and our findings are no exception. Approximately 1 out of every 7 adults reported daily fruits or vegetables consumption while most people reported consuming fruits or vegetables 2–3 days per week. Even then, the number of servings that were reported was low. Lower intake, however, has been reported across the continent.[19, 23] The reasons for this trend are multifactorial but may include affordability, availability, taste preferences and the need for storage of fresh fruits and vegetables. Especially for the poor, the need to refrigerate and preserve fresh foods may limit these as food choices if refrigeration is unavailable.

In western Kenya, it is not uncommon for vegetables to be cooked for many hours before ingestion. To most closely approximate nutritionally meaningful vegetable intake we decided not to consider this type of intake as a vegetable serving. Cooking most vegetables appears to decrease the content of micronutrients, vitamins, antioxidant activity and biologically active compounds such as beta-carotene.[24, 25, 26, 27] Long-term epidemiologic studies of NCDs also associate consumption of uncooked vegetables with lower all-cause mortality than consuming cooked vegetables.[28] After field-testing, we ultimately asked participants if the vegetables they ate were cooked at home and for how long they cooked their vegetables. This was a crude proxy for the likely nutritional value of the vegetable in the absence of literature from our region of the nutritional content of the cooked and uncooked vegetables that are consumed in this community. Subsequent studies in similar areas should take nutritional content of cooked and uncooked vegetables into consideration as it may influence the proper interpretation of reported vegetable intake. By excluding vegetable servings that were cooked for prolonged periods, we may have underestimated total vegetable intake which includes those cooked for short and long periods of time and uncooked vegetables.

Patterns of physical activity

Almost all respondents reported engaging in some form of physical activity. Recreational physical activity in Webuye was much less common than work- or travel-related activity. This probably reflects the fact that farming is the main type of work performed and that walking or bicycle riding is the usual mode for traversing the physical environment. Greater physical activity was seen among those with less education, which may also relate to the physical types of occupations available to this group compared to those with more formal education. Taken together with the short length of time spent sedentary on a daily basis (~2 hours per day), it appears that physical inactivity would not be a major cardiovascular health intervention target for this region and is also consistent with epidemiologic data that suggests that physical inactivity is not a major predictor of cardiovascular disease in SSA.[15]

Patterns of self-reported high blood pressure and blood sugar

The higher prevalence of self-reported high blood pressure among women is commonly found in surveys employing a similar methodology.[29] Data from Botswana, for example, are that the proportion of women reporting a history of hypertension was twice that of men (20% vs. 10%).[19] These surveys are usually carried out in the home during daytime hours when many women in rural and peri-urban SSA are at home and men are not. In addition, the more regular health-seeking behavior of women[30] may have led to more women being aware of their condition. Prevalence rates of confirmed hypertension vary widely across the region but have been reported as high as 50% in some ethnic groups.[7] Moreover, awareness is generally low. In Ethiopia and Tanzania (neighboring East African countries) 65% and 50%, respectively, of those found to have hypertension were unaware of their condition.[19, 31] Confirmatory testing, which is part of the second “step” of the risk factor surveillance is needed to put our findings in context. Data from the region suggests that awareness of hypertension may also be low in Webuye, though the actual prevalence remains unknown. Similar to high blood pressure, women are more likely to report a history of high blood sugar than men or to have had their blood sugar measured as has been reported in Zimbabwe and Tanzania (Zanzibar).[19] Rates of diagnosed diabetes or impaired fasting glucose range from 2.4% in Zimbabwe to 10% in Seychelles.[19] Our rates of a reported history of raised blood sugar were <1% for both sexes and this could be attributed to lack of testing or low awareness. Awareness of diabetes is also known to be generally low in SSA, even among those who have previously diagnosed.[32, 33] The reasons for this are myriad but include factors such as the generally low public awareness of the condition, misconceptions about the causes and access to appropriate medical services.[34]

Our findings should be taken in the context of the following limitations. The Webuye HDSS was initially developed as a district-level demographic surveillance system in a peri-urban setting. It is not possible, therefore, to generalize our findings to the country level. In addition, most of the risk factors we studied are contextually bound and relate to the social and cultural factors shaping individual behavior related to these risk factors. For example, physical activity is high in this community but is directed towards work and travel, not recreation or exercise. Whether these types of physical activities confer the same benefit as regular exercise in SSA should be explored in the appropriate sociocultural context. The behavioral risk factors in this study (i.e. tobacco use, alcohol use, and physical activity) were self-reported which might underestimate the actual levels of risk factors reported. It is well known, for example, that self-reported tobacco or alcohol use is usually lower than actual, especially in settings where these behaviors are discouraged for religious reasons or among women. While we may have obtained an incorrect estimate of the usage patterns using STEPs, the benefit of this approach is comparability between various regions and countries. Although fruit and vegetable intake was low, self-report bias would have also over-represented the amount of fruit and vegetable intake due to social desirability and the fact that the concept of vegetables is broad in this community. The nutrient content of vegetables in this region after prolonged cooking also remains unknown. We were also not able to measure blood pressure, other physical measurements or lipid levels at this time but plan to perform these measures during a subsequent phase of data collection in the HDSS as they are critical to understanding cardiovascular risk. Confirmatory testing for raised blood sugar, for example, could be compared to self-report in order to quantify the level of awareness.

CONCLUSIONS

Cardiovascular risk factors are present in peri-urban western Kenya with the most commonly reported ones being tobacco and alcohol use and inadequate fruit and vegetable intake. There are sub-group differences whereby tobacco and alcohol use was more common among men and those who are older. Inadequate fruit and vegetable intake is common in this community while physical activity appears adequate. Self-report of high blood sugar is absolutely low and more women than men reported having high blood pressure. Confirmatory testing for these latter two risk factors is necessary. Taken together, these findings identify and document that cardiovascular risk factors are present in this region. Our findings from this district-level HDSS may have limited generalizability owing to the structure of the surveillance system. Educational and preventive efforts regarding tobacco and alcohol cessation appear most relevant to older adults and men in this community while dietary change is more relevant to women in order to address the burden of cardiovascular risk factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Health Sciences Project of the Moi University-Kenya-VLIR UOS Institutional University Cooperation program (lead by BO) and grant 5K01TW008407 from the Fogarty International Center (to GSB) of the US National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaziano TA. Cardiovascular disease in the developing world and its cost-effective management. Circulation. 2005;112:3547–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strong KL, Bonita R. Investing in surveillance: a fundamental tool of public health. Soz Praventivmed. 2004;49:269–75. doi: 10.1007/s00038-004-3076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sankoh O. Global health estimates: stronger collaboration needed with low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1001005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloomfield GS, Kimaiyo S, Carter EJ, et al. Chronic noncommunicable cardiovascular and pulmonary disease in sub-Saharan Africa: An academic model for countering the epidemic. Am Heart J. 2011;161:842–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulter NR, Khaw KT, Hopwood BE, et al. The Kenyan Luo migration study: observations on the initiation of a rise in blood pressure. BMJ. 1990;300:967–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6730.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathenge W, Foster A, Kuper H. Urbanization, ethnicity and cardiovascular risk in a population in transition in Nakuru, Kenya: a population-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:569. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogeng’o JA, Gatonga P, Olabu BO. Cardiovascular causes of death in an east African country: an autopsy study. Cardiol J. 2011;18:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng N, Van Minh H, Juvekar S, et al. Using the INDEPTH HDSS to build capacity for chronic non-communicable disease risk factor surveillance in low and middle-income countries. Glob Health Action. 2009:2. doi: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan A, Nongkynrih B, Kapoor SK, et al. A role for INDEPTH Asian sites in translating research to action for non-communicable disease prevention and control: a case study from Ballabgarh, India. Glob Health Action. 2009:2. doi: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simiyu CJ, Naanyu V, Obala AA, et al. Population Association of America. New Orleans, Louisiana: 2013. A Profile of Webuye Health and Demographic Surveillance System in Western Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strong KL, Bonita R. Surveillance of Risk Factors related to Noncommunicable Diseases: Current Status of Global Data. Geneva: WHO; 2003. The SuRF Report 1; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases, Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steyn K, Sliwa K, Hawken S, et al. Risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in Africa: the INTERHEART Africa study. Circulation. 2005;112:3554–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.563452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalal S, Beunza JJ, Volmink J, et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:885–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vint F. Post-mortem findings in the natives of Kenya. East African Medical Journal. 1937;13:332–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bovet P, Romain S, Shamlaye C, et al. Divergent fifteen-year trends in traditional and cardiometabolic risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in the Seychelles. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. [Accessed June 2013];STEPS Country Reports. http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/index.html.

- 20.WHO. Report on the global tobacco epidemic: implementing smoke-free environments. WHO Press; Geneva: 2009. pp. 1–568. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization; World Health Organization, editor. Tobacco or Health: A Global Status Report. Geneva: 1997. Smoking Prevalence; pp. 10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padrão P, Laszczyńska O, Silva-Matos C, et al. Low fruit and vegetable consumption in Mozambique: results from a WHO STEPwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:428–35. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Msyamboza KP, Ngwira B, Dzowela T, et al. The burden of selected chronic non-communicable diseases and their risk factors in Malawi: nationwide STEPS survey. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan L, O’Connell O, O’Sullivan L, et al. Micellarisation of carotenoids from raw and cooked vegetables. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2008;63:127–33. doi: 10.1007/s11130-008-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikora E, Bodziarczyk I. Composition and antioxidant activity of kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) raw and cooked. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2012;11:239–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellegrini N, Chiavaro E, Gardana C, et al. Effect of different cooking methods on color, phytochemical concentration, and antioxidant capacity of raw and frozen brassica vegetables. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:4310–21. doi: 10.1021/jf904306r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiménez-Monreal AM, García-Diz L, Martínez-Tomé M, et al. Influence of cooking methods on antioxidant activity of vegetables. J Food Sci. 2009;74:H97–H103. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leenders M, Sluijs I, Ros MM, et al. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Mortality: European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Central Statistical Office (CSO) [Zimbabwe] and Macro International Inc. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2005–06. Calverton, Maryland: CSO and Macro International Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Pretorius S, et al. Elevated risk factors but low burden of heart disease in urban African primary care patients: a fundamental role for primary prevention. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tesfaye F, Byass P, Wall S. Population based prevalence of high blood pressure among adults in Addis Ababa: uncovering a silent epidemic. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azevedo M, Alla S. Diabetes in sub-saharan Africa: kenya, mali, mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa and zambia. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2008;28:101–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-3930.45268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elbagir MN, Eltom MA, Elmahadi EM, et al. A population-based study of the prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in adults in northern Sudan. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1126–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiawi E, Edwards R, Shu J, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior relating to diabetes and its main risk factors among urban residents in Cameroon: a qualitative survey. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:503–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.