Summary

Background

Physical and mental health could greatly affect sexual activity and fulfilment, but the nature of associations at a population level is poorly understood. We used data from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3) to explore associations between health and sexual lifestyles in Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales).

Methods

Men and women aged 16–74 years who were resident in households in Britain were interviewed between Sept 6, 2010, and Aug 31, 2012. Participants completed the survey in their own homes through computer-assisted face-to-face interviews and self-interview. We analysed data for self-reported health status, chronic conditions, and sexual lifestyles, weighted to account for unequal selection probabilities and non-response to correct for differences in sex, age group, and region according to 2011 Census figures.

Findings

Interviews were done with 15 162 participants (6293 men, 8869 women). The proportion reporting recent sexual activity (one or more occasion of vaginal, oral, or anal sex with a partner of the opposite sex, or oral or anal sex or genital contact with a partner of the same sex in the past 4 weeks) decreased with age after the age of 45 years in men and after the age of 35 years in women, while the proportion in poorer health categories increased with age. Recent sexual activity was less common in participants reporting bad or very bad health than in those reporting very good health (men: 35·7% [95% CI 28·6–43·5] vs 74·8% [72·7–76·7]; women: 34·0% [28·6–39·9] vs 67·4% [65·4–69·3]), and this association remained after adjusting for age and relationship status (men: adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0·29 [95% CI 0·19–0·44]; women: 0·43 [0·31–0·61]). Sexual satisfaction generally decreased with age, and was significantly lower in those reporting bad or very bad health than in those reporting very good health (men: 45·4% [38·4–52·7] vs 69·5% [67·3–71·6], AOR 0·51 [0·36–0·72]; women: 48·6% [42·9–54·3] vs 65·6% [63·6–67·4], AOR 0·69 [0·53–0·91]). In both sexes, reduced sexual activity and reduced satisfaction were associated with limiting disability and depressive symptoms, and reduced sexual activity was associated with chronic airways disease and difficulty walking up the stairs because of a health problem. 16·6% (95% CI 15·4–17·7) of men and 17·2% (16·3–18·2) of women reported that their health had affected their sex life in the past year, increasing to about 60% in those reporting bad or very bad health. 23·5% (20·3–26·9) of men and 18·4% (16·0–20·9) of women who reported that their health affected their sex life reported that they had sought clinical help (>80% from general practitioners; <10% from specialist services).

Interpretation

Poor health is independently associated with decreased sexual activity and satisfaction at all ages in Britain. Many people in poor health report an effect on their sex life, but few seek clinical help. Sexual lifestyle advice should be a component of holistic health care for patients with chronic ill health.

Funding

Grants from the UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust, with support from the Economic and Social Research Council and Department of Health.

Introduction

Physical and mental health disorders, the drugs used to treat them, and long-term disability could greatly affect sexual lifestyles1, 2, 3, 4—ie, sexual activity, sexual behaviours, sexual problems, the formation and maintenance of relationships, and sexual satisfaction.5, 6, 7 For example, poor self-assessed general health is associated with reduced sexual activity and frequency of sexual activity in older people.4 However, most population-based studies investigating these associations have not been specifically designed to measure sexual behaviour, and have included only one or a few measures of health,8, 9, 10, 11, 12 surveyed only men,13, 14, 15 or been focused on older people.4, 8, 13, 14, 16 In the past 5 years, some studies have included both self-reported and biological or physical measures of a few specific disorders to explore associations with sexual function.17, 18 However, some chronic conditions—eg, arthritis, stroke, or heart disease—cannot easily be measured with biological or physical measures in large surveys of this kind. Therefore, the associations between ill health or disabilities and sexual lifestyles are not well described across the sexually active adult life at a population level. Moreover, the effect of health on people's sex lives is seldom considered in clinical practice,19, 20 and the evidence base that can be used to guide clinical management is small.

A decrease in sexual activity and frequency of sexual activity is associated with increasing age, although about half of people aged 65–74 years report sexual activity in the past year.4, 5, 8, 9, 13, 21 As the strongest driver of chronic ill health and long-term disability, age is therefore an important confounder in studies of the associations between health and sexual lifestyles. Likewise, the availability of partners—which could be limited by widowhood, no stable partner, or other reasons—affects these associations.1

In the past two decades, detailed information about sexual lifestyles across the population in Britain (England, Scotland, and Wales) has been obtained in the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Howevever, these large probability sample surveys have not previously included detailed questions about health.5, 6, 7 In the third Natsal survey (Natsal-3), participants were asked to provide information about their health, including self-assessed general health, disability, functional impairment, and specific chronic conditions. Furthermore, people aged 16–74 years were included, which provides a rare opportunity to investigate the associations between sexual lifestyles and health across the life course in men and women.

We tested the hypothesis that poor health, disability, and specific chronic conditions would remain associated with three measures of sexual lifestyles after adjustment for age and relationship status: recent sexual activity, sexual satisfaction, and sexual response problems specific to men or women (erectile difficulties and vaginal dryness). To provide actionable information for clinicians and policy makers, we investigated whether people felt that any health condition or disability had affected their sex lives and the extent to which clinical advice had been sought.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Full details of the methods of Natsal-3 have been reported elsewhere.5, 22, 23 Briefly, we used a multistage, clustered, and stratified probability sample design. Men and women aged 16–74 years who were resident in households in Britain were interviewed between Sept 6, 2010, and Aug 31, 2012. An anonymised dataset will be deposited with the UK Data Archive, and the complete questionnaire and technical report will be available on the Natsal website on the day of publication.

Participants were interviewed in their own homes by professional interviewers without clinical qualifications using computer-assisted personal interview. Participants were asked about self-assessed general health with a widely cited and validated question,24 and about any longstanding and restricting illness or disability. To measure self-reported functional ability, participants were asked whether they had any difficulty walking up a flight of stairs because of a health problem.25 Body-mass index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported height and weight. To obtain information about self-reported clinical diagnoses of a range of chronic conditions, interviewers used show cards listing different disorders to ask participants whether they had any of the conditions listed. The first card asked whether a doctor had ever told them that they had cardiac or vascular diseases, hypertension, diabetes, chronic airways disease, and arthritis. Separate cards asked whether participants had ever had prostate diseases, broken hip or pelvis, and hip replacement, and whether they had received treatment from a health-care professional for any backache or bone or muscle disease lasting for more than 3 months in the past year.

Participants subsequently completed a computer-assisted self-interview, which included a validated two-question patient health questionnaire (PHQ-2), with which depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks were assessed with two screening questions (scored 0–3).26 Participants were deemed to have depressive symptoms if they had a total score of 3 or more, a cutoff which has been previously validated.27 Participants were asked whether they had had any health condition or disability in the past year that they felt had affected their sexual activity or enjoyment in any way. Additionally, participants were asked whether they had sought help or advice about their sex life from a range of sources in the past year; more than one answer was allowed. The questionnaire underwent thorough cognitive testing and piloting, as previously reported.23, 28

The computer-assisted self-interview included many questions about sexual practices, partners, and activity.22 Here, we focus on four measures: recent sexual activity, satisfaction with sex life, sexual response problems, and relationship status. Recent sexual activity was defined as reporting of one or more occasion of vaginal, oral, or anal sex with a partner of the opposite sex, or oral or anal sex or genital contact with a partner of the same sex in the past 4 weeks. Participants were asked to think about their sex life in the past year in response to the statement “I feel satisfied with my sex life”. We deemed that those answering that they agreed or agreed strongly were satisfied with their sex life. Participants reporting at least one sexual partner in the past year were asked to report which, if any, of a range of sexual difficulties they had experienced for at least 6 months in the past year (the duration of symptoms corresponded to criteria in the 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition29). Here, we focus on trouble achieving or maintaining an erection in men and an uncomfortably dry vagina in women, because these difficulties capture both physiological and psychological elements of sexual response and are associated with ageing.30 Finally, participants were divided into four categories on the basis of their relationship status at the time of interview: cohabiting with a partner (including marriage and civil partnerships); in a steady relationship (ie, expected to engage in sexual activity again with their partner) but not cohabiting with their partner; no steady relationship but reported previous cohabitation; and no steady relationship and never cohabited.

The Natsal-3 study was approved by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee A (reference: 09/H0604/27). Participants provided oral informed consent for interviews.

Statistical analysis

We did all analyses with the complex survey functions of Stata (version 12.1), accounting for stratification, clustering, and weighting of data. We included only participants who reported having had one or more sexual partner over the lifetime in our analysis, because those reporting no previous sexual experience did not complete the computer-assisted self-interview.

For sexual activity, satisfaction, response, and the perception of health effects on sex life, we report prevalences and 95% CIs in men and women by age group, relationship status, and each health variable. We weighted Natsal-3 data to adjust for the unequal probabilities of selection in terms of age and the number of adults in the eligible age range at an address. After application of these selection weights, the Natsal-3 sample was broadly representative of the British population compared with 2011 Census figures,22, 31 although men and London residents were slightly under-represented. Therefore, we also applied a non-response post-stratification weight to correct for differences in sex, age and Government Office Region between the achieved sample and the 2011 Census.

We used logistic regression models to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for associations with demographic and health variables, adjusting for age and relationship status. We additionally adjusted models investigating age and relationship status for self-assessed general health to understand the associations with age and relationship status independently of health status. We adjusted models investigating specific chronic health conditions for age, relationship status, and comorbidity (using categories of zero or one condition and more than one condition) to take account of the clustering of illnesses.

Role of the funding source

The sponsors of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Interviews were done with 15 162 participants (6293 men, 8869 women). 5994 men and 8452 women reported having had one or more sexual partner over the lifetime. The proportion of people in the worst self-reported health categories increased with age (table 1). The proportion of individuals reporting sexual activity in the past 4 weeks was highest in men aged 25–44 years and in women aged 25–34 years and decreased with age thereafter (table 2). The proportion of individuals reporting sexual activity in the past 4 weeks also varied by relationship status, with single people much less likely to report sexual activity than those in a steady relationship (table 2).

Table 1.

General health characteristics of participants reporting at least one sexual partner over the lifetime, by age group and sex

| 16–24 years | 25–34 years | 35–44 years | 45–54 years | 55–64 years | 65–74 years | All age groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||||||

| Self-reported general health status | ||||||||

| Very good | 49·4% (46·6–52·2) | 47·8% (45·0–50·6) | 41·6% (37·9–45·4) | 35·8% (40·6–48·8) | 26·6% (38·2–46·3) | 24·6% (37·7–46·2) | 38·8% (37·4–40·3) | |

| Good | 42·4% (39·6–45·1) | 41·0% (38·2–43·9) | 45·1% (41·3–48·9) | 44·6% (40·6–48·8) | 42·2% (38·2–46·3) | 41·9% (37·7–46·2) | 43·0% (41·4–44·6) | |

| Fair | 7·5% (6·2–9·0) | 9·9% (8·2–11·9) | 10·9% (9·0–13·3) | 15·2% (12·6–18·2) | 21·7% (18·5–25·4) | 27·1% (23·5–31·0) | 14·4% (13·3–15·5) | |

| Bad or very bad | 0·7% (0·4–1·2) | 1·2% (0·8–1·9) | 2·4% (1·6–3·6) | 4·4% (3·2–6·0) | 9·5% (7·4–12·1) | 6·4% (4·6–8·9) | 3·8% (3·3–4·4) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 1689 | 1473 | 783 | 747 | 697 | 603 | 5992 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1210 | 1332 | 1386 | 1334 | 1093 | 779 | 7133 | |

| Longstanding illnesses or disability | ||||||||

| None | 86·2% (84·1–88·1) | 82·6% (80·4–84·6) | 76·2% (72·8–79·3) | 63·8% (59·9–67·6) | 46·6% (42·7–50·5) | 43·2% (39·1–47·3) | 68·6% (67·2–70·0) | |

| Non-limiting | 8·3% (7·0–10·0) | 8·4% (7·0–10·1) | 10·6% (8·4–13·3) | 18·2% (15·2–21·7) | 24·4% (21·1–28·1) | 27·3% (23·8–31·2) | 15·2% (14·1–16·3) | |

| Limiting | 5·4% (4·3–6·8) | 9·0% (7·5–10·8) | 13·2% (11·0–15·8) | 17·9% (15·2–21·0) | 29·0% (25·5–32·7) | 29·5% (25·9–33·4) | 16·2% (15·1–17·3) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 1689 | 1472 | 783 | 748 | 697 | 603 | 5992 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1210 | 1332 | 1386 | 1335 | 1094 | 779 | 7135 | |

| Number of self-reported chronic conditions* | ||||||||

| 0 | 90·6% (89·0–92·1) | 82·4% (80·0–84·6) | 71·8% (68·1–75·2) | 58·0% (54·1–61·8) | 38·5% (34·7–42·4) | 30·0% (26·1–34·1) | 64·7% (63·2–66·2) | |

| 1 | 8·5% (7·1–10·1) | 14·5% (12·6–16·7) | 21·4% (18·4–24·8) | 28·3% (24·9–32·0) | 33·0% (29·5–36·7) | 33·8% (29·8–38·0) | 22·3% (21·0–23·7) | |

| ≥2 | 0·9% (0·6–1·4) | 3·1% (2·1–4·6) | 6·8% (5·3–8·7) | 13·7% (11·2–16·6) | 28·5% (25·2–32·1) | 36·3% (32·3–40·5) | 13·0% (11·9–14·0) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 1687 | 1471 | 783 | 748 | 697 | 602 | 5988 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1208 | 1331 | 1386 | 1335 | 1094 | 778 | 7132 | |

| Difficulty walking up stairs because of a health problem | ||||||||

| No difficulty | 98·2% (97·4–98·8) | 96·5% (95·0–97·5) | 94·4% (92·5–95·8) | 88·2% (85·5–90·5) | 79·6% (76·3–82·7) | 72·4% (68·3–76·2) | 89·6% (88·6–90·5) | |

| Some difficulty | 1·7% (1·1–2·5) | 3·1% (2·1–4·6) | 3·8% (2·6–5·5) | 9·7% (7·7–12·2) | 13·1% (10·6–16·0) | 19·5% (16·3–23·1) | 7·6% (6·8–8·4) | |

| Much difficulty or unable | 0·1% (0·0–0·4) | 0·4% (0·2–0·8) | 1·8% (1·1–3·0) | 2·1% (1·3–3·3) | 7·3% (5·4–9·7) | 8·1% (5·9–10·9) | 2·8% (2·4–3·4) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 1689 | 1473 | 782 | 748 | 698 | 603 | 5993 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1210 | 1332 | 1384 | 1335 | 1095 | 779 | 7135 | |

| Women | ||||||||

| Self-reported general health status | ||||||||

| Very good | 45·7% (43·4–48·1) | 46·1% (43·8–48·3) | 47·7% (44·6–50·9) | 36·5% (39·1–45·7) | 32·6% (36·5–43·0) | 26·0% (37·6–44·8) | 40·0% (38·8–41·2) | |

| Good | 43·5% (41·1–45·8) | 42·8% (40·6–45·1) | 39·4% (36·4–42·6) | 42·4% (39·1–45·7) | 39·7% (36·5–43·0) | 41·2% (37·6–44·8) | 41·5% (40·3–42·7) | |

| Fair | 8·9% (7·7–10·2) | 9·5% (8·2–10·9) | 10·0% (8·3–12·0) | 15·5% (13·2–18·1) | 19·6% (17·2–22·3) | 23·6% (20·7–26·7) | 13·9% (13·0–14·8) | |

| Bad or very bad | 1·9% (1·4–2·7) | 1·7% (1·2–2·3) | 2·8% (2·0–4·0) | 5·7% (4·4–7·2) | 8·1% (6·4–10·2) | 9·3% (7·3–11·8) | 4·6% (4·1–5·2) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 2081 | 2379 | 1158 | 1057 | 974 | 803 | 8452 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1172 | 1325 | 1393 | 1366 | 1166 | 856 | 7278 | |

| Longstanding illnesses or disability | ||||||||

| None | 82·6% (80·7–84·4) | 78·7% (77·0–80·4) | 73·6% (70·9–76·1) | 63·7% (60·4–66·8) | 51·4% (47·8–55·0) | 41·4% (37·6–45·2) | 66·8% (65·5–68·0) | |

| Non-limiting | 8·5% (7·1–10·0) | 11·0% (9·8–12·3) | 12·8% (10·9–15·0) | 12·9% (10·8–15·4) | 20·2% (17·5–23·2) | 26·2% (22·9–29·7) | 14·5% (13·6–15·5) | |

| Limiting | 8·9% (7·7–10·3) | 10·3% (9·0–11·7) | 13·7% (11·7–15·9) | 23·4% (20·8–26·3) | 28·4% (25·3–31·7) | 32·5% (29·0–36·2) | 18·7% (17·7–19·7) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 2081 | 2378 | 1158 | 1057 | 974 | 803 | 8451 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1172 | 1324 | 1393 | 1366 | 1166 | 856 | 7278 | |

| Number of self-reported chronic conditions* | ||||||||

| 0 | 81·9% (80·0–83·6) | 72·9% (70·9–74·9) | 66·6% (63·7–69·4) | 51·2% (47·8–54·7) | 36·6% (33·3–40·1) | 23·5% (20·5–26·8) | 57·5% (56·2–58·7) | |

| 1 | 15·8% (14·2–17·5) | 21·3% (19·5–23·2) | 23·0% (20·5–25·7) | 28·6% (25·6–31·8) | 31·9% (28·6–35·3) | 30·9% (27·5–34·5) | 24·9% (23·8–26·0) | |

| ≥2 | 2·4% (1·8–3·2) | 5·7% (4·8–6·8) | 10·4% (8·7–12·3) | 20·2% (17·7–22·9) | 31·5% (28·4–34·8) | 45·6% (41·9–49·4) | 17·6% (16·6–18·6) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 2080 | 2378 | 1156 | 1055 | 974 | 803 | 8446 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1171 | 1324 | 1391 | 1364 | 1166 | 856 | 7273 | |

| Difficulty walking up stairs because of health problem | ||||||||

| No difficulty | 96·4% (95·5–97·2) | 95·7% (94·7–96·6) | 92·0% (90·2–93·6) | 82·5% (79·8–84·8) | 74·5% (71·4–77·5) | 61·4% (57·7–65·1) | 85·2% (84·2–86·2) | |

| Some difficulty | 3·2% (2·5–4·1) | 3·4% (2·6–4·3) | 6·1% (4·7–7·7) | 12·2% (10·2–14·6) | 17·5% (15·1–20·2) | 25·9% (22·8–29·2) | 10·4% (9·6–11·3) | |

| Much difficulty or unable | 0·4% (0·2–0·7) | 0·9% (0·6–1·4) | 1·9% (1·2–2·9) | 5·3% (4·1–6·8) | 7·9% (6·2–10·0) | 12·7% (10·4–15·5) | 4·3% (3·8–4·9) | |

| Unweighted denominator | 2081 | 2379 | 1158 | 1057 | 973 | 803 | 8451 | |

| Weighted denominator | 1172 | 1325 | 1393 | 1366 | 1165 | 856 | 7276 | |

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs. Denominators are all individuals reporting one or more sexual partner over the lifetime and vary across variables because of item non-response. For all variables and both sexes, the χ2 p value for association with age was <0·0001.

Measure of comorbidity includes arthritis, heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, broken hip or pelvis bone or hip replacement ever, backache lasting longer than 3 months, any other muscle or bone disease lasting longer than 3 months, depression, cancer, and any thyroid condition treated in the past year.

Table 2.

Reporting of sexual activity in the past 4 weeks in relation to demographic and health characteristics, by sex

|

Men |

Women |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage reporting sexual activity | AOR | p value | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | Percentage reporting sexual activity | AOR | p value | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | |||

| All | 67·4% (66·0–68·8) | .. | .. | 5994 | 7137 | 61·6% (60·4–62·9) | .. | .. | 8452 | 7278 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age group | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| 16–24 years | 58·2% (55·5–60·8) | 1·00 | .. | 1689 | 1210 | 63·4% (60·9–65·7) | 1·00 | .. | 2081 | 1172 | ||

| 25–34 years | 79·4% (77·1–81·5) | 1·05 (0·82–1·35) | .. | 1473 | 1332 | 80·0% (78·1–81·7) | 0·82 (0·65–1·03) | .. | 2379 | 1325 | ||

| 35–44 years | 79·4% (76·3–82·2) | 0·62 (0·46–0·82) | .. | 783 | 1386 | 75·8% (73·1–78·4) | 0·45 (0·34–0·58) | .. | 1158 | 1393 | ||

| 45–54 years | 74·9% (71·4–78·2) | 0·53 (0·39–0·72) | .. | 748 | 1335 | 68·0% (64·9–70·9) | 0·30 (0·23–0·39) | .. | 1057 | 1366 | ||

| 55–64 years | 58·8% (54·7–62·7) | 0·24 (0·18–0·32) | .. | 698 | 1095 | 43·2% (39·7–46·6) | 0·10 (0·08–0·13) | .. | 974 | 1166 | ||

| 65–74 years | 39·3% (35·2–43·6) | 0·09 (0·07–0·13) | .. | 603 | 779 | 22·7% (19·6–26·1) | 0·04 (0·03–0·06) | .. | 803 | 856 | ||

| Relationship status | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| Living with a partner | 78·2% (76·5–79·9) | 1·00 | .. | 2938 | 4649 | 73·5% (71·9–75·1) | 1·00 | .. | 4329 | 4646 | ||

| In a steady relationship, not cohabiting | 90·7% (88·2–92·7) | 1·35 (0·98–1·84) | .. | 955 | 766 | 88·4% (86·3–90·3) | 1·18 (0·93–1·49) | .. | 1355 | 784 | ||

| No steady relationship, previously cohabited | 27·7% (24·2–31·4) | 0·09 (0·07–0·12) | .. | 752 | 669 | 17·9% (15·9–20·1) | 0·07 (0·05–0·08) | .. | 1560 | 1118 | ||

| No steady relationship, never cohabited | 27·8% (25·1–30·7) | 0·02 (0·02–0·03) | .. | 1297 | 1003 | 23·6% (20·8–26·6) | 0·02 (0·01–0·02) | .. | 1162 | 697 | ||

| General health | ||||||||||||

| Self-reported general health status | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| Very good | 74·8% (72·7–76·7) | 1·00 | .. | 2411 | 2771 | 67·4% (65·4–69·3) | 1·00 | .. | 3429 | 2912 | ||

| Good | 68·0% (65·9–69·9) | 0·73 (0·62–0·87) | .. | 2532 | 3067 | 62·7% (60·8–64·6) | 0·92 (0·79–1·07) | .. | 3545 | 3020 | ||

| Fair | 54·5% (50·4–58·5) | 0·51 (0·40–0·66) | .. | 826 | 1025 | 50·9% (47·6–54·3) | 0·81 (0·65–1·01) | .. | 1125 | 1010 | ||

| Bad or very bad | 35·7% (28·6–43·5) | 0·29 (0·19–0·44) | .. | 223 | 270 | 34·0% (28·6–39·9) | 0·43 (0·31–0·61) | .. | 353 | 335 | ||

| Longstanding illnesses or disability | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| None | 71·7% (70·1–73·2) | 1·00 | .. | 4269 | 4897 | 67·1% (65·7–68·6) | 1·00 | .. | 5856 | 4859 | ||

| Non-limiting | 64·1% (60·3–67·7) | 0·92 (0·74–1·14) | .. | 803 | 1084 | 55·3% (51·8–58·7) | 0·86 (0·71–1·04) | .. | 1131 | 1058 | ||

| Limiting | 52·6% (48·9–56·2) | 0·62 (0·51–0·76) | .. | 920 | 1155 | 46·8% (43·8–49·9) | 0·43 (0·38–0·50) | .. | 1464 | 1360 | ||

| Number of self-reported chronic conditions* | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| 0 | 71·7% (70·1–73·2) | 1·00 | .. | 4140 | 4615 | 68·5% (66·9–70·0) | 1·00 | .. | 5196 | 4179 | ||

| 1 | 66·0% (62·8–69·0) | 0·91 (0·74–1·11) | .. | 1178 | 1593 | 60·3% (57·7–62·9) | 0·96 (0·81–1·13) | .. | 1993 | 1813 | ||

| ≥2 | 48·9% (44·6–53·2) | 0·58 (0·46–0·74) | .. | 670 | 924 | 41·1% (38·0–44·3) | 0·67 (0·55–0·81) | .. | 1257 | 1282 | ||

| Body-mass index | 0·0134 | 0·0011 | ||||||||||

| Normal: 18·5–25 kg/m2 | 67·3% (65·1–69·4) | 1·00 | .. | 2633 | 2820 | 67·0% (65·2–68·7) | 1·00 | .. | 3326 | 4020 | ||

| Underweight: <18·5 kg/m2 | 46·0% (35·9–56·5) | 0·51 (0·28–0·92) | .. | 128 | 105 | 59·3% (53·2–65·2) | 0·80 (0·53–1·22) | .. | 315 | 211 | ||

| Overweight: 25–30 kg/m2 | 70·8% (68·5–73·0) | 1·02 (0·85–1·23) | .. | 2009 | 2660 | 59·9% (57·5–62·3) | 0·87 (0·74–1·03) | .. | 2062 | 1918 | ||

| Obese: 30–35 kg/m2 | 67·5% (63·6–71·2) | 0·87 (0·69–1·10) | .. | 711 | 965 | 55·6% (51·9–59·3) | 0·78 (0·63–0·96) | .. | 937 | 879 | ||

| Obese: >35 kg/m2 | 56·3% (48·8–63·6) | 0·60 (0·40–0·90) | .. | 263 | 353 | 48·4% (43·5–53·3) | 0·57 (0·43–0·76) | .. | 535 | 484 | ||

| Difficulty walking up stairs because of health problem | <0·0001 | 0·0008 | ||||||||||

| No difficulty | 69·8% (68·4–71·2) | 1·00 | .. | 5432 | 6393 | 65·3% (64·0–66·7) | 1·00 | .. | 7385 | 6201 | ||

| Some difficulty | 52·7% (47·2–58·1) | 0·68 (0·53–0·89) | .. | 406 | 540 | 42·8% (38·8–47·0) | 0·72 (0·57–0·90) | .. | 749 | 759 | ||

| Much difficulty or unable | 32·5% (24·6–41·7) | 0·34 (0·21–0·54) | .. | 155 | 202 | 34·1% (28·3–40·5) | 0·56 (0·40–0·78) | .. | 317 | 316 | ||

| Specific health conditions | ||||||||||||

| Any cardiac or vascular disease† | 0·4173 | 0·2769 | ||||||||||

| No | 68·7% (67·2–70·1) | 1·00 | .. | 5697 | 6738 | 62·7% (61·4–64·0) | 1·00 | .. | 8193 | 7013 | ||

| Yes | 46·6% (40·4–52·9) | 0·88 (0·63–1·21) | .. | 296 | 398 | 32·4% (26·3–39·2) | 0·82 (0·57–1·17) | .. | 256 | 263 | ||

| Hypertension | 0·4103 | 0·6093 | ||||||||||

| No | 69·2% (67·7–70·6) | 1·00 | .. | 5401 | 6257 | 64·2% (62·9–65·5) | 1·00 | .. | 7612 | 6365 | ||

| Yes | 55·0% (50·6–59·3) | 0·90 (0·70–1·16) | .. | 592 | 879 | 43·5% (39·9–47·2) | 1·06 (0·85–1·31) | .. | 837 | 911 | ||

| Diabetes | 0·0384 | 0·1933 | ||||||||||

| No | 68·5% (67·1–69·9) | 1·00 | .. | 5719 | 6746 | 62·6% (61·3–63·9) | 1·00 | .. | 8158 | 6973 | ||

| Yes | 48·3% (41·7–55·0) | 0·69 (0·49–0·98) | .. | 274 | 391 | 38·8% (32·9–45·1) | 0·80 (0·56 −1·12) | .. | 291 | 303 | ||

| Chronic airways disease | 0·0041 | 0·0017 | ||||||||||

| No | 67·9% (66·5–69·3) | 1·00 | .. | 5931 | 7052 | 62·0% (60·8–63·3) | 1·00 | .. | 8365 | 7191 | ||

| Yes | 27·3% (16·0–42·4) | 0·35 (0·17–0·71) | .. | 62 | 84 | 25·3% (16·8–36·3) | 0·41 (0·23–0·71) | .. | 84 | 84 | ||

| Arthritis | 0·4949 | 0·0230 | ||||||||||

| No | 69·0% (67·6–70·4) | 1·00 | .. | 5535 | 6490 | 65·5% (64·2–66·8) | 1·00 | .. | 7495 | 6248 | ||

| Yes | 51·3% (46·4–56·3) | 0·91 (0·68–1·20) | .. | 458 | 646 | 37·8% (34·2–41·5) | 0·76 (0·60–0·96) | .. | 954 | 1028 | ||

| Broken hip or pelvis or hip replacement | 0·8368 | 0·0886 | ||||||||||

| No | 67·7% (66·3–69·1) | 1·00 | .. | 5909 | 7020 | 62·2% (60·9–63·4) | 1·00 | .. | 8326 | 7146 | ||

| Yes | 53·8% (41·8–65·4) | 0·94 (0·51–1·74) | .. | 81 | 114 | 31·2% (22·5–41·3) | 0·62 (0·35–1·08) | .. | 123 | 129 | ||

| Backache, or bone or muscle disease for >3 months in past year | 0·1032 | 0·7451 | ||||||||||

| No | 67·7% (66·2–69·2) | 1·00 | .. | 5367 | 6286 | 63·4% (62·0–64·7) | 1·00 | .. | 7292 | 6195 | ||

| Yes | 65·4% (61·1–69·4) | 1·23 (0·96–1·58) | .. | 625 | 849 | 51·5% (48·2–54·9) | 1·04 (0·84–1·28) | .. | 1158 | 1081 | ||

| Depressive symptoms‡ | <0·0001 | 0·0178 | ||||||||||

| No | 70·2% (68·8–71·6) | 1·00 | .. | 5214 | 6331 | 63·6% (62·3–65·0) | 1·00 | .. | 7292 | 6374 | ||

| Yes | 52·3% (47·5–57·0) | 0·55 (0·43–0·72) | .. | 607 | 660 | 53·5% (50·0–57·0) | 0·76 (0·61–0·95) | .. | 983 | 780 | ||

| Prostate disease or surgery | 0·8643 | |||||||||||

| No | 68·0% (66·6–69·4) | 1·00 | .. | 5805 | 6873 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Yes | 52·4% (44·3–60·3) | 0·97 (0·66–1·42) | .. | 185 | 261 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Menopause§ | 0·0060 | |||||||||||

| No | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 23·7% (21·6–25·9) | 1·00 | .. | 1007 | 1092 | ||

| Yes | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 32·8% (30·6–35·1) | 0·61 (0·42–0·87) | .. | 1006 | 1418 | ||

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs. Sexual activity was defined as one or more occasion of vaginal, oral, or anal sex with a partner of the opposite sex, or oral or anal sex or genital contact with a partner of the same sex in the past 4 weeks. All models were adjusted for age and relationship status. Models investigating age and relationship status also adjusted for self–assessed general health status. Models investigating specific conditions were also adjusted for comorbidity, for which comorbidity was coded as 0=0–1 specific conditions and 1=≥2 specific conditions. AOR=adjusted odds ratio.

Measure of comorbidity and includes arthritis, heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, broken hip or pelvis bone or hip replacement ever, backache lasting longer than 3 months, any other muscle or bone disease lasting longer than 3 months, depression, cancer, and any thyroid condition treated in the past year.

Heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, and stroke.

Respondents were asked whether they had often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in the past 2 weeks, and whether they had often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things in the past 2 weeks, with a validated two-question patient health questionnaire (PHQ-2).

Women deemed to be postmenopausal when they had not menstruated in the past year, with analysis restricted to those aged 45–64 years.

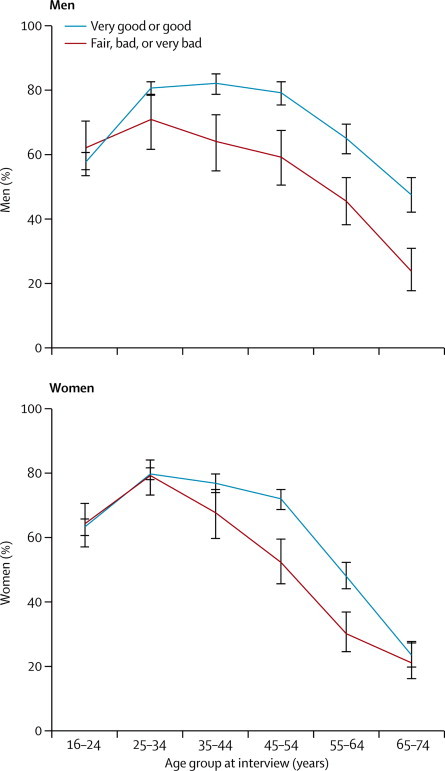

Overall, the proportion of men and women reporting sexual activity in the past 4 weeks was lower in those reporting bad or very bad health than in those reporting very good health, and this association remained after adjustment for age and relationship status (table 2). We recorded significant differences in the proportion reporting sexual activity in the past 4 weeks by health status in men aged 35–44 years and older, and in women aged 45–64 years (figure).

Figure.

Reporting of sexual activity in past 4 weeks by sex and self-assessed general health status

Bars show 95% CIs. Sexual activity was defined as one or more occasion of vaginal, oral, or anal sex with a partner of the opposite sex, or oral or anal sex or genital contact with a partner of the same sex in the past 4 weeks.

Similarly, we recorded strong associations between other broad measures of self-reported health and sexual activity in the past 4 weeks. After adjustment for age and relationship status, men and women reporting a limiting longstanding illness, two or more chronic conditions, a BMI of more than 35 kg/m2, or difficulty walking up stairs because of a health problem were significantly less likely to report sexual activity in the past 4 weeks than were those who did not report these issues (table 2). Although fewer individuals reporting specific health conditions reported sexual activity in the past 4 weeks than did those without these disorders, after adjustment for age, relationship status, and comorbidities, the associations were significant only for men and women with chronic airways disease or depressive symptoms, men with diabetes, and women with arthritis or who were postmenopausal (table 2). In sensitivity analyses, the patterns of association were broadly in the same direction and of a similar magnitude for reporting of sexual activity in the past 6 months and when the analysis was restricted to individuals aged 45–74 (data not shown).

More than 60% of men and women reported being satisfied with their sex life (table 3). Overall, after adjustment for relationship status and health, satisfaction decreased significantly after the age of 35 years in men and after the age of 25 years in women (table 3), but the association with age was weaker than for sexual activity. The percentage of men reporting sexual satisfaction was significantly lower in those reporting good, fair, or bad or very bad health than in those reporting very good health (table 3). The percentage of women reporting sexual satisfaction was also significantly lower in those reporting fair, bad, or very bad health than in those reporting very good health (table 3). Similar associations were recorded for other broad measures of health (table 3). However, after adjustment for age, relationship status, and comorbidities, depressive symptoms was the only specific health condition to be significantly associated with low sexual satisfaction (table 3).

Table 3.

Reporting of satisfaction with sex life in the past year in relation to demographic and health characteristics, by sex

|

Men |

Women |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage reporting sexual satisfaction | AOR | p value | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | Percentage reporting sexual satisfaction | AOR | p value | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | |||

| All | 61·7% (60·3–63·1) | .. | .. | 5933 | 7110 | 61·4% (60·2–62·7) | .. | .. | 8428 | 7278 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age group | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| 16–24 years | 64·8% (62·2–67·3) | 1·00 | .. | 1601 | 1150 | 68·3% (66·0–70·5) | 1·00 | .. | 1985 | 1109 | ||

| 25–34 years | 68·7% (66·1–71·2) | 0·88 (0·72–1·08) | .. | 1477 | 1332 | 68·5% (66·4–70·6) | 0·70 (0·59–0·83) | .. | 2409 | 1334 | ||

| 35–44 years | 63·1% (59·4–66·7) | 0·62 (0·49–0·79) | .. | 788 | 1390 | 64·0% (61·0–66·9) | 0·53 (0·43–0·64) | .. | 1179 | 1416 | ||

| 45–54 years | 61·2% (57·2–65·0) | 0·61 (0·47–0·78) | .. | 759 | 1355 | 59·8% (56·5–63·0) | 0·46 (0·38–0·56) | .. | 1085 | 1395 | ||

| 55–64 years | 54·3% (50·2–58·3) | 0·50 (0·39–0·64) | .. | 707 | 1106 | 54·8% (51·5–58·1) | 0·41 (0·33–0·50) | .. | 977 | 1174 | ||

| 65–74 years | 53·9% (49·5–58·2) | 0·51 (0·39–0·66) | .. | 601 | 778 | 48·9% (45·1–52·8) | 0·38 (0·30–0·47) | .. | 793 | 849 | ||

| Relationship status | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| Living with a partner | 64·9% (63·0–66·8) | 1·00 | .. | 2957 | 4685 | 67·0% (65·4–68·6) | 1·00 | .. | 4377 | 4709 | ||

| In a steady relationship, not cohabiting | 83·0% (80·0–85·6) | 2·04 (1·62–2·56) | .. | 959 | 768 | 79·6% (76·8–82·1) | 1·47 (1·22–1·78) | .. | 1375 | 797 | ||

| No steady relationship, previously cohabited | 38·5% (34·8–42·3) | 0·37 (0·30–0·44) | .. | 791 | 704 | 34·9% (32·3–37·6) | 0·29 (0·25–0·34) | .. | 1599 | 1131 | ||

| No steady relationship, never cohabited | 45·7% (42·7–48·8) | 0·31 (0·26–0·37) | .. | 1196 | 929 | 43·7% (40·5–47·0) | 0·25 (0·21–0·30) | .. | 1042 | 616 | ||

| General health | ||||||||||||

| Self-reported general health status | <0·0001 | 0·0018 | ||||||||||

| Very good | 69·5% (67·3–71·6) | 1·00 | .. | 2382 | 2752 | 65·6% (63·6–67·4) | 1·00 | .. | 3408 | 2902 | ||

| Good | 60·1% (57·8–62·3) | 0·69 (0·59–0·80) | .. | 2502 | 3063 | 61·7% (59·7–63·6) | 0·90 (0·79–1·01) | .. | 3533 | 3022 | ||

| Fair | 50·0% (45·8–54·1) | 0·52 (0·42–0·65) | .. | 816 | 1013 | 53·1% (49·8–56·4) | 0·75 (0·63–0·89) | .. | 1132 | 1016 | ||

| Bad or very bad | 45·4% (38·4–52·7) | 0·51 (0·36–0·72) | .. | 231 | 280 | 48·6% (42·9–54·3) | 0·69 (0·53–0·91) | .. | 355 | 338 | ||

| Longstanding illnesses or disability | 0·0052 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| None | 64·6% (63·0–66·3) | 1·00 | .. | 4209 | 4865 | 64·8% (63·3–66·3) | 1·00 | .. | 5828 | 4840 | ||

| Non-limiting | 58·2% (53·9–62·3) | 0·88 (0·72–1·08) | .. | 798 | 1085 | 57·7% (54·4–60·9) | 0·86 (0·74–1·01) | .. | 1130 | 1057 | ||

| Limiting | 52·5% (48·8–56·2) | 0·77 (0·64–0·92) | .. | 924 | 1159 | 52·3% (49·4–55·1) | 0·59 (0·52–0·68) | .. | 1469 | 1381 | ||

| Number of self-reported chronic conditions* | 0·0075 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| 0 | 65·1% (63·4–66·7) | 1·00 | .. | 4068 | 4577 | 67·0% (65·5–68·6) | 1·00 | .. | 5141 | 4142 | ||

| 1 | 58·2% (55·0–61·3) | 0·84 (0·71–1·00) | .. | 1179 | 1599 | 58·1% (55·6–60·6) | 0·77 (0·67–0·88) | .. | 2020 | 1841 | ||

| ≥2 | 51·0% (46·8–55·3) | 0·74 (0·60–0·92) | .. | 679 | 929 | 48·1% (45·1–51·2) | 0·62 (0·52–0·73) | .. | 1262 | 1291 | ||

| Body-mass index | 0·0045 | 0·1190 | ||||||||||

| Normal: 18·5–25 kg/m2 | 63·6% (61·4–65·8) | 1·00 | .. | 2599 | 2800 | 63·7% (61·9–65·5) | 1·00 | .. | 3329 | 4013 | ||

| Underweight: <18·5 kg/m2 | 58·2% (48·1–67·6) | 0·94 (0·61–1·44) | .. | 120 | 100 | 65·7% (59·1–71·7) | 1·20 (0·88–1·64) | .. | 302 | 200 | ||

| Overweight: 25–30 kg/m2 | 61·3% (58·9–63·6) | 0·90 (0·77–1·04) | .. | 2007 | 2669 | 60·9% (58·5–63·3) | 0·98 (0·86–1·12) | .. | 2084 | 1941 | ||

| Obese: 30–35 kg/m2 | 61·7% (57·6–65·7) | 0·95 (0·77–1·17) | .. | 714 | 967 | 56·2% (52·7–59·8) | 0·86 (0·72–1·02) | .. | 935 | 879 | ||

| Obese: >35 kg/m2 | 46·4% (39·5–53·6) | 0·53 (0·38–0·74) | .. | 259 | 347 | 54·3% (49·4–59·2) | 0·81 (0·64–1·02) | .. | 534 | 483 | ||

| Difficulty walking up stairs because of health problem | 0·0119 | 0·0873 | ||||||||||

| No difficulty | 62·8% (61·3–64·3) | 1·00 | .. | 5366 | 6361 | 63·1% (61·7–64·4) | 1·00 | .. | 7361 | 6197 | ||

| Some difficulty | 56·1% (50·5–61·6) | 1·01 (0·78–1·30) | .. | 413 | 550 | 53·8% (49·8–57·7) | 0·94 (0·78–1·14) | .. | 749 | 764 | ||

| Much difficulty or unable | 42·2% (33·8–51·0) | 0·61 (0·42–0·90) | .. | 153 | 198 | 47·6% (41·3–54·0) | 0·77 (0·58–1·04) | .. | 317 | 316 | ||

| Specific health conditions | ||||||||||||

| Any cardiac or vascular disease† | 0·7804 | 0·3598 | ||||||||||

| No | 62·3% (60·9–63·7) | 1·00 | .. | 5630 | 6706 | 61·9% (60·6–63·2) | 1·00 | .. | 8174 | 7015 | ||

| Yes | 51·4% (45·2–57·5) | 1·04 (0·77 – 1·41) | .. | 302 | 404 | 49·3% (42·4–56·2) | 1·17 (0·84–1·64) | .. | 251 | 261 | ||

| Hypertension | 0·3162 | 0·2841 | ||||||||||

| No | 62·9% (61·5–64·4) | 1·00 | .. | 5334 | 6226 | 62·7% (61·3–64·0) | 1·00 | .. | 7581 | 6358 | ||

| Yes | 52·8% (48·4–57·2) | 0·89 (0·71 – 1·12) | .. | 598 | 884 | 52·7% (49·0–56·3) | 1·11 (0·92–1·35) | .. | 844 | 918 | ||

| Diabetes | 0·4124 | 0·3036 | ||||||||||

| No | 62·3% (60·8–63·7) | 1·00 | .. | 5661 | 6719 | 62·1% (60·8–63·4) | 1·00 | .. | 8134 | 6968 | ||

| Yes | 51·7% (44·7–58·7) | 0·87 (0·63 – 1·21) | .. | 271 | 390 | 46·1% (39·8–52·5) | 0·85 (0·62–1·16) | .. | 291 | 307 | ||

| Chronic airways disease | 0·5281 | 0·1941 | ||||||||||

| No | 61·8% (60·3–63·2) | 1·00 | .. | 5868 | 7026 | 61·6% (60·4–62·9) | 1·00 | .. | 8341 | 7191 | ||

| Yes | 55·2% (41·8–67·9) | 1·22 (0·66 – 2·23) | .. | 64 | 84 | 42·1% (31·2–53·8) | 0·72 (0·44 – 1·18) | .. | 84 | 85 | ||

| Arthritis | 0·2272 | 0·4645 | ||||||||||

| No | 62·3% (60·8–63·7) | 1·00 | .. | 5472 | 6464 | 63·5% (62·2–64·8) | 1·00 | .. | 7476 | 6247 | ||

| Yes | 55·6% (50·5–60·6) | 1·18 (0·90 – 1·54) | .. | 460 | 646 | 48·9% (45·5–52·4) | 0·93 (0·75–1·14) | .. | 949 | 1029 | ||

| Broken hip or pelvis or hip replacement | 0·4519 | 0·1319 | ||||||||||

| No | 61·7% (60·3–63·1) | 1·00 | .. | 5847 | 6994 | 61·8% (60·5–63·0) | 1·00 | .. | 8301 | 7143 | ||

| Yes | 59·3% (47·0–70·5) | 1·24 (0·71 – 2·14) | .. | 81 | 112 | 41·5% (32·4–51·3) | 0·72 (0·46–1·11) | .. | 125 | 134 | ||

| Backache, or bone or muscle disease for >3 months in past year | 0·7165 | 0·0782 | ||||||||||

| No | 62·1% (60·6–63·6) | 1·00 | .. | 5301 | 6256 | 63·1% (61·7–64·4) | 1·00 | .. | 7252 | 6179 | ||

| Yes | 58·7% (54·3–63·0) | 1·04 (0·84 – 1·30) | .. | 630 | 853 | 52·1% (48·9–55·4) | 0·85 (0·70–1·02) | .. | 1174 | 1079 | ||

| Depressive symptoms‡ | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| No | 63·8% (62·4–65·3) | 1·00 | .. | 5303 | 6430 | 64·0% (62·7–65·3) | 1·00 | .. | 7400 | 6466 | ||

| Yes | 40·6% (36·1–45·3) | 0·42 (0·33 – 0·52) | .. | 621 | 667 | 40·6% (37·1–44·2) | 0·41 (0·34–0·49) | .. | 1020 | 804 | ||

| Prostate disease or surgery | 0·3774 | |||||||||||

| No | 62·1% (60·7–63·6) | 1·00 | .. | 5737 | 6837 | .. | .. | .. | ..- | .. | ||

| Yes | 49·9% (42·4–57·5) | 0·85 (0·60 – 1·21) | .. | 191 | 269 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | ||

| Menopause§ | 0·7000 | |||||||||||

| No | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 19·6% (17·7–21·7) | 1·00 | .. | 644 | 831 | ||

| Yes | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 37·8% (35·4–40·2) | 1·05 (0·79–1·40) | .. | 1339 | 1714 | ||

| Sexual activity | .. | |||||||||||

| Sexually active in the past 4 weeks | <0·0001 | <0·0001 | ||||||||||

| No | 37·1% (34·8–39·6) | 1·00 | .. | 1995 | 2174 | 38·0% (35·9–40·0) | 1·00 | .. | 3035 | 2645 | ||

| Yes | 73·7% (71·9–75·4) | 3·69 (3·13–4·35) | .. | 3801 | 4789 | 75·9% (74·5–77·3) | 3·73 (3·22–4·32) | .. | 5184 | 4465 | ||

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs. All models were adjusted for age and relationship status. Models investigating age and relationship status also adjusted for self-assessed general health status. Models investigating specific conditions were also adjusted for comorbidity, for which comorbidity was coded as 0=0–1 specific conditions and 1=≥2 specific conditions. AOR=adjusted odds ratio.

Measure of comorbidity and includes arthritis, heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, broken hip or pelvis bone or hip replacement ever, backache lasting longer than 3 months, any other muscle or bone disease lasting longer than 3 months, depression, cancer, and any thyroid condition treated in the past year.

Heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, and stroke.

Respondents were asked whether they had often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in the past 2 weeks, and whether they had often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things in the past 2 weeks, with a validated two-question patient health questionnaire (PHQ-2).

Women deemed to be postmenopausal when they had not menstruated in the past year, with analysis restricted to those aged 45–64 years.

The percentage of individuals reporting sexual response problems increased with age: erectile difficulties were most common in men aged 65–74 years (affecting 26·2%, 95% CI 21·5–31·6) and vaginal dryness was most common in women aged 55–64 years (affecting 22·1%, 18·7–25·9; appendix). After adjustment for age and relationship status, participants with poorer general health, a limiting disability, or two or more chronic conditions were more likely than those who did not report these issues to have erectile difficulties or vaginal dryness (appendix). For specific health conditions in men, reporting of erectile difficulties was associated only with depressive symptoms after adjustment for age, relationship status, and comorbidities. In women, reporting of vaginal dryness was associated with a previous broken hip or pelvis or a hip replacement, depressive symptoms, being postmenopausal, and backache or bone or muscle disease for more than 3 months in the past year (appendix).

The percentage of male participants reporting that a health condition had affected their sex life in the past year increased in each successive age group (table 4). In women, the pattern was different: the percentage was highest in those aged 45–54 years, and lowest in those aged 16–24 years and 65–74 years (table 5). After adjustment for age and relationship status, we recorded strong associations in men and women between reporting that a health condition affected one's sex life and poorer self-assessed general health, limiting disabilities, one or more comorbidity, and difficulty with walking up stairs (Table 4, Table 5). By contrast with the small number of specific chronic conditions associated with sexual activity, satisfaction, and sexual response problems, reporting of an effect of health conditions on one's sex life was associated with a range of chronic health conditions: cardiac or vascular disease, chronic airways disease, backache, and depressive symptoms in both men and women; diabetes and prostate disease in men; and arthritis and hip or pelvis fracture or hip replacement in women (Table 4, Table 5).

Table 4.

Reporting of health conditions affecting sexual activity or enjoyment in the past year and whether clinical advice has been sought, in relation to demographic and health characteristics of men

|

All men |

Men whose health affects sex life |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage reporting that their health affects sex life | Adjusted odds ratio | p value | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | Percentage reporting that they sought clinical advice* | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | |||

| All | 16·6% (15·4–17·7) | .. | .. | 5621 | 6870 | 23·5% (20·3–26·9) | 845 | 1134 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age group | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| 16–24 years | 6·1% (4·9–7·7) | 1·00 | .. | 1362 | 995 | 11·3% (5·7–21·2) | 87 | 61 | ||

| 25–34 years | 10·6% (9·1–12·3) | 1·64 (1·20–2·24) | .. | 1445 | 1296 | 15·9% (10·7–23·1) | 161 | 137 | ||

| 35–44 years | 14·2% (11·7–17·0) | 2·10 (1·47–3·01) | .. | 782 | 1378 | 23·6% (16·1–33·1) | 121 | 195 | ||

| 45–54 years | 18·1% (15·2–21·4) | 2·48 (1·76–3·49) | .. | 749 | 1343 | 25·2% (17·8–34·4) | 139 | 240 | ||

| 55–64 years | 25·4% (22·0–29·0) | 3·03 (2·17–4·21) | .. | 698 | 1095 | 25·5% (19·2–33·1) | 178 | 278 | ||

| 65–74 years | 29·2% (25·2–33·5) | 3·83 (2·73–5·38) | .. | 585 | 762 | 26·9% (20·3–34·6) | 159 | 222 | ||

| Relationship status | 0·4449 | |||||||||

| Living with a partner | 17·5% (16·0–19·1) | 1·00 | .. | 2944 | 4665 | 23·5% (19·6–27·8) | 496 | 813 | ||

| In a steady relationship, not cohabiting | 12·6% (10·2–15·4) | 1·05 (0·80–1·39) | .. | 955 | 766 | 34·6% (24·2–46·8) | 109 | 96 | ||

| No steady relationship, previously cohabited | 21·5% (18·4–25·0) | 0·86 (0·67–1·11) | .. | 796 | 709 | 22·0% (15·0–31·1) | 159 | 152 | ||

| No steady relationship, never cohabited | 9·9% (7·8–12·5) | 0·84 (0·62–1·14) | .. | 920 | 725 | 11·4% (5·7–21·5) | 81 | 72 | ||

| General health | ||||||||||

| Self-reported health status | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| Very good | 7·6% (6·4–9·1) | 1·00 | .. | 2241 | 2638 | 21·7% (15·1–30·3) | 154 | 201 | ||

| Good | 14·6% (13·0–16·3) | 1·88 (1·49–2·38) | .. | 2367 | 2963 | 22·7% (17·8–28·6) | 311 | 432 | ||

| Fair | 33·8% (30·2–37·6) | 5·05 (3·90–6·54) | .. | 787 | 993 | 24·9% (19·2–31·6) | 250 | 332 | ||

| Bad or very bad | 60·7% (53·0–67·9) | 14·57 (9·86–21·52) | .. | 224 | 273 | 24·8% (17·4–34·0) | 129 | 166 | ||

| Longstanding illness or disability | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| None | 9·0% (8·0–10·2) | 1·00 | .. | 3957 | 4669 | 20·5% (15·7–26·4) | 319 | 421 | ||

| Non-limiting | 21·2% (18·1–24·7) | 2·19 (1·70–2·81) | .. | 765 | 1061 | 26·0% (18·9–34·6) | 154 | 225 | ||

| Limiting | 43·1% (39·4–46·9) | 6·22 (4·99–7·76) | .. | 897 | 1139 | 24·8% (20·3–29·9) | 372 | 488 | ||

| Number of self-reported chronic conditions† | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| 0 | 8·3% (7·3–9·4) | 1·00 | .. | 3812 | 4381 | 17·7% (12·8–24·1) | 297 | 364 | ||

| 1 | 22·7% (20·2–25·5) | 2·82 (2·26–3·52) | .. | 1123 | 1540 | 27·3% (21·5–34·1) | 253 | 347 | ||

| ≥2 | 44·6% (40·6–48·8) | 7·16 (5·59–9·17) | .. | 686 | 948 | 25·2% (20·2–30·9) | 295 | 423 | ||

| Body-mass index | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| Normal: 18·5–25 kg/m2 | 13·4% (11·8–15·1) | 1·00 | .. | 2428 | 2669 | 22·3% (17·2–28·3) | 296 | 356 | ||

| Underweight: <18·5 kg/m2 | 12·3% (6·4–22·4) | 1·28 (0·62–2·65) | .. | 95 | 84 | 33·0% (7·8–74·3) | 11 | 10 | ||

| Overweight: 25–30 kg/m2 | 16·4% (14·6–18·4) | 1·06 (0·86–1·30) | .. | 1948 | 2615 | 25·1% (20·0–31·1) | 299 | 428 | ||

| Obese: 30–35 kg/m2 | 20·2% (17·1–23·8) | 1·30 (1·01–1·68) | .. | 696 | 954 | 25·8% (18·4–34·9) | 133 | 190 | ||

| Obese: >35 kg/m2 | 31·4% (25·4–38·2) | 2·27 (1·62–3·17) | .. | 254 | 342 | 22·2% (13·5–34·2) | 77 | 107 | ||

| Difficulty walking up stairs because of health problem | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No difficulty | 12·6% (11·5–13·8) | 1·00 | .. | 5069 | 6133 | 23·9% (20·0–28·3) | 584 | 773 | ||

| Some difficulty | 43·4% (38·0–49·1) | 4·06 (3·13–5·28) | .. | 401 | 542 | 24·7% (18·3–32·5) | 169 | 232 | ||

| Much difficulty or unable | 65·6% (56·9–73·3) | 9·80 (6·51–14·76) | .. | 150 | 193 | 17·7% (10·4–28·4) | 91 | 127 | ||

| Specific health conditions | ||||||||||

| Any cardiac or vascular disease‡ | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No | 14·9% (13·8–16·0) | 1·00 | .. | 5376 | 6528 | 22·0% (18·7–25·7) | 735 | 967 | ||

| Yes | 48·8% (42·0–55·6) | 2·14 (1·57–2·91) | .. | 244 | 341 | 31·9% (23·5–41·7) | 110 | 166 | ||

| Hypertension | 0·7823 | |||||||||

| No | 14·1% (13·0–15·3) | 1·00 | .. | 5031 | 5994 | 23·6% (19·9–27·7) | 652 | 843 | ||

| Yes | 33·2% (29·1–37·6) | 1·04 (0·81–1·32) | .. | 589 | 876 | 23·0% (17·4–29·8) | 193 | 291 | ||

| Diabetes | 0·0045 | |||||||||

| No | 15·1% (14·0–16·3) | 1·00 | .. | 5357 | 6486 | 22·6% (19·2–26·3) | 732 | 976 | ||

| Yes | 41·1% (34·7–47·9) | 1·55 (1·15–2·09) | .. | 263 | 383 | 28·8% (20·3–39·2) | 113 | 158 | ||

| Chronic airways disease | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No | 16·1% (15·0–17·2) | 1·00 | .. | 5558 | 6787 | 23·8% (20·6–27·4) | 812 | 1087 | ||

| Yes | 56·5% (42·0–69·9) | 4·12 (2·09–8·12) | .. | 62 | 83 | 15·1% (6·1–32·8) | 33 | 47 | ||

| Arthritis | 0·5600 | |||||||||

| No | 14·8% (13·6–16·0) | 1·00 | .. | 5172 | 6235 | 24·1% (20·6–28·0) | 694 | 917 | ||

| Yes | 34·1% (29·4–39·2) | 1·08 (0·83–1·41) | .. | 448 | 635 | 20·6% (14·4–28·5) | 151 | 217 | ||

| Broken hip or pelvis or hip replacement | 0·1012 | |||||||||

| No | 16·1% (15·0–17·3) | 1·00 | 5536 | 6754 | 23·2% (20·0–26·8) | 813 | 1086 | |||

| Yes | 41·4% (29·9–53·9) | 1·55 (0·92–2·61) | .. | 81 | 112 | 29·9% (15·9–49·0) | 31 | 46 | ||

| Backache, or bone or muscle disease for >3 months in past year | 0·0277 | |||||||||

| No | 14·2% (13·1–15·4) | 1·00 | .. | 5013 | 6035 | 24·9% (21·1–29·0) | 649 | 855 | ||

| Yes | 33·3% (29·3–37·5) | 1·31 (1·03–1·67) | .. | 606 | 834 | 19·1% (13·8–25·9) | 195 | 278 | ||

| Depressive symptoms§ | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No | 14·8% (13·7–16·0) | 1·00 | .. | 5027 | 6215 | 22·6% (19·1–26·5) | 664 | 916 | ||

| Yes | 33·7% (29·4–38·4) | 2·62 (2·05–3·34) | .. | 582 | 638 | 26·6% (19·8–34·8) | 179 | 215 | ||

| Prostate disease or surgery | 0·0026 | |||||||||

| No | 15·7% (14·6–16·9) | 1·00 | .. | 5427 | 6598 | 22·6% (19·4–26·3) | 768 | 1032 | ||

| Yes | 37·6% (30·3–45·5) | 1·82 (1·23–2·68) | .. | 190 | 269 | 32·0% (22·0–43·9) | 76 | 101 | ||

| Sexual activity | ||||||||||

| Sexually active in the past 4 weeks | 0·0275 | |||||||||

| No | 21·2% (19·0–23·5) | 1·00 | .. | 1704 | 1952 | 20·3% (15·7–25·9) | 314 | 413 | ||

| Yes | 14·3% (13·0–15·7) | 0·80 (0·65–0·97) | .. | 3780 | 4769 | 25·1% (21·0–29·7) | 492 | 682 | ||

| Satisfied with sex life | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No | 23·6% (21·5–25·8) | 1·00 | .. | 2099 | 2586 | 27·4% (23·1–32·3) | 458 | 610 | ||

| Yes | 12·3% (11·0–13·6) | 0·50 (0·42–0·59) | .. | 3510 | 4269 | 18·8% (14·7–23·8) | 387 | 524 | ||

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs. All models were adjusted for age and relationship status. Models investigating age and relationship status also adjusted for self-assessed general health status. Models investigating specific conditions were also adjusted for comorbidity, for which comorbidity was coded as 0=0–1 specific conditions and 1=≥2 specific conditions.

General practitioner, sexual health clinic, other clinics or doctors, or psychiatrist or psychologist.

Measure of comorbidity and includes arthritis, heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, broken hip or pelvis bone or hip replacement ever, backache lasting longer than 3 months, any other muscle or bone disease lasting longer than 3 months, depression, cancer, and any thyroid condition treated in the past year.

Heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, and stroke.

Respondents were asked whether they had often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in the past 2 weeks, and whether they had often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things in the past 2 weeks, with a validated two-question patient health questionnaire (PHQ-2).

Table 5.

Reporting of health conditions affecting sexual activity or enjoyment in the past year and whether clinical advice has been sought, in relation to demographic and health characteristics of women

|

All women |

Women whose health affects sex life |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage reporting that their health affects sex life | Adjusted odds ratio | p value | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | Percentage reporting that they sought clinical advice* | Unweighted denominator | Weighted denominator | |||

| All | 17·2% (16·3–18·2) | .. | .. | 8097 | 7071 | 18·4% (16·0–20·9) | 1322 | 1215 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age group | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| 16–24 years | 13·2% (11·5–15·2) | 1·00 | .. | 1716 | 957 | 24·4% (18·7–31·2) | 223 | 126 | ||

| 25–34 years | 18·5% (16·8–20·4) | 1·27 (1·03–1·56) | .. | 2376 | 1312 | 19·9% (15·9–24·6) | 425 | 243 | ||

| 35–44 years | 16·6% (14·4–19·0) | 1·02 (0·80–1·29) | .. | 1174 | 1404 | 16·4% (11·7–22·4) | 190 | 233 | ||

| 45–54 years | 19·6% (17·1–22·3) | 1·03 (0·81–1·31) | .. | 1064 | 1374 | 16·8% (11·9–23·2) | 218 | 269 | ||

| 55–64 years | 18·8% (16·2–21·7) | 0·86 (0·66–1·12) | .. | 975 | 1175 | 22·5% (16·3–30·1) | 165 | 219 | ||

| 65–74 years | 14·8% (12·1–17·9) | 0·58 (0·43–0·77) | .. | 792 | 848 | 9·2% (4·8–16·9) | 101 | 125 | ||

| Relationship status | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| Living with a partner | 19·1% (17·8–20·4) | 1·00 | .. | 4357 | 4678 | 18·5% (15·6–21·7) | 809 | 889 | ||

| In a steady relationship, not cohabiting | 17·2% (14·9–19·8) | 0·81 (0·66–1·00) | .. | 1373 | 796 | 19·2% (14·2–25·5) | 220 | 137 | ||

| No steady relationship, previously cohabited | 12·2% (10·5–14·0) | 0·42 (0·35–0·52) | .. | 1620 | 1153 | 17·1% (12·5–22·9) | 214 | 140 | ||

| No steady relationship, never cohabited | 10·9% (8·5–14·0) | 0·42 (0·32–0·57) | .. | 738 | 439 | 17·7% (10·2–29·0) | 78 | 48 | ||

| General health | ||||||||||

| Self-reported health status | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| Very good | 9·6% (8·4–10·8) | 1·00 | .. | 3245 | 2799 | 21·4% (16·3–27·5) | 299 | 267 | ||

| Good | 15·3% (14·0–16·7) | 1·80 (1·51–2·15) | .. | 3392 | 2928 | 18·0% (14·5–22·1) | 516 | 448 | ||

| Fair | 30·6% (27·7–33·8) | 4·99 (4·05–6·15) | .. | 1110 | 1009 | 20·5% (15·9–26·0) | 319 | 307 | ||

| Bad or very bad | 57·5% (51·5–63·4) | 17·29 (12·96–23·05) | .. | 350 | 335 | 11·7% (7·8–17·1) | 188 | 193 | ||

| Longstanding illness or disability | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| None | 11·3% (10·3–12·3) | 1·00 | .. | 5550 | 4666 | 18·7% (15·3–22·7) | 621 | 525 | ||

| Non-limiting | 14·3% (12·2–16·8) | 1·48 (1·19–1·85) | .. | 1107 | 1042 | 25·2% (18·4–33·5) | 155 | 149 | ||

| Limiting | 39·8% (36·8–42·8) | 6·29 (5·28–7·50) | .. | 1439 | 1363 | 16·2% (13·0–19·8) | 546 | 540 | ||

| Number of self-reported chronic conditions† | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| 0 | 10·6% (9·6–11·7) | 1·00 | .. | 4865 | 3976 | 18·2% (14·5–22·5) | 510 | 421 | ||

| 1 | 20·0% (18·0–22·2) | 2·47 (2·06–2·96) | .. | 1953 | 1788 | 20·0% (16·0–24·7) | 408 | 358 | ||

| ≥2 | 33·5% (30·6–36·4) | 6·26 (5·11–7·68) | .. | 1278 | 1306 | 17·2% (13·5–21·7) | 404 | 435 | ||

| Body-mass index | 0·0039 | |||||||||

| Normal: 18·5–25 kg/m2 | 16·5% (15·1–18·0) | 1·00 | .. | 3844 | 3220 | 20·0% (16·5–24·1) | 601 | 532 | ||

| Underweight: <18·5 kg/m2 | 18·8% (13·8–25·1) | 1·32 (0·89–1·95) | .. | 261 | 178 | 17·3% (7·4–35·4) | 46 | 33 | ||

| Overweight: 25–30 kg/m2 | 15·9% (14·1–17·8) | 0·93 (0·78–1·10) | .. | 2039 | 1906 | 14·2% (10·5–18·9) | 311 | 302 | ||

| Obese: 30–35 kg/m2 | 20·4% (17·4–23·6) | 1·28 (1·03–1·60) | .. | 920 | 874 | 22·3% (15·9–30·4) | 178 | 176 | ||

| Obese: >35 kg/m2 | 22·0% (17·9–26·6) | 1·43 (1·09–1·88) | .. | 529 | 482 | 19·3% (12·5–28·6) | 110 | 105 | ||

| Difficulty walking up stairs because of health problem | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No difficulty | 13·8% (12·9–14·8) | 1·00 | .. | 7041 | 5995 | 20·2% (17·3–23·5) | 949 | 827 | ||

| Some difficulty | 30·1% (26·5–34·0) | 3·34 (2·72–4·11) | .. | 742 | 760 | 19·6% (14·6–25·9) | 225 | 227 | ||

| Much difficulty or unable | 51·3% (44·8–57·7) | 8·81 (6·65–11·68) | .. | 313 | 315 | 7·0% (4·0–12·1) | 148 | 161 | ||

| Specific health conditions | ||||||||||

| Any cardiac or vascular disease‡ | 0·0043 | |||||||||

| No | 16·8% (15·8–17·8) | 1·00 | .. | 7900 | 6864 | 18·7% (16·3–21·3) | 1269 | 1148 | ||

| Yes | 32·1% (25·0–40·2) | 1·71 (1·18–2·46) | .. | 195 | 205 | 12·4% (4·8–28·3) | 52 | 66 | ||

| Hypertension | 0·1057 | |||||||||

| No | 16·5% (15·5–17·6) | 1·00 | .. | 7262 | 6161 | 18·9% (16·4–21·7) | 1162 | 1018 | ||

| Yes | 21·8% (18·7–25·2) | 0·83 (0·67–1·04) | .. | 833 | 909 | 15·5% (10·0–23·1) | 159 | 196 | ||

| Diabetes | 0·0637 | |||||||||

| No | 16·7% (15·7–17·7) | 1·00 | .. | 7808 | 6766 | 18·1% (15·7–20·7) | 1243 | 1125 | ||

| Yes | 29·2% (23·5–35·7) | 1·35 (0·98–1·85) | .. | 287 | 304 | 21·8% (13·9–32·5) | 78 | 89 | ||

| Chronic airways disease | 0·0002 | |||||||||

| No | 16·9% (16·0–17·9) | 1·00 | .. | 8009 | 6983 | 18·5% (16·2–21·2) | 1292 | 1180 | ||

| Yes | 38·9% (27·7–51·4) | 2·69 (1·62–4·49) | .. | 86 | 86 | 11·0% (3·7–28·5) | 29 | 34 | ||

| Arthritis | 0·0177 | |||||||||

| No | 15·6% (14·7–16·7) | 1·00 | .. | 7146 | 6038 | 19·2% (16·6–22·2) | 1078 | 942 | ||

| Yes | 26·4% (23·3–29·8) | 1·29 (1·05–1·60) | .. | 949 | 1031 | 15·2% (10·9–20·8) | 243 | 272 | ||

| Broken hip or pelvis or hip replacement | 0·0069 | |||||||||

| No | 16·9% (15·9–17·9) | 1·00 | .. | 7972 | 6939 | 18·9% (16·5–21·5) | 1285 | 1168 | ||

| Yes | 35·0% (25·8–45·4) | 1·85 (1·19–2·88) | .. | 122 | 130 | 6·3% (1·9–18·6) | 36 | 46 | ||

| Backache, or bone or muscle disease for >3 months in past year | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No | 14·5% (13·5–15·5) | 1·00 | .. | 6942 | 5988 | 18·6% (15·9–21·6) | 962 | 867 | ||

| Yes | 32·3% (29·3–35·5) | 1·70 (1·40–2·06) | .. | 1153 | 1081 | 17·8% (13·7–22·8) | 360 | 347 | ||

| Depressive symptoms§ | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No | 14·9% (13·9–15·9) | 1·00 | .. | 7102 | 6278 | 17·7% (15·1–20·7) | 1002 | 935 | ||

| Yes | 35·8% (32·2–39·5) | 2·75 (2·28–3·33) | .. | 985 | 781 | 20·6% (16·2–25·9) | 320 | 279 | ||

| Menopause¶ | 0·2097 | |||||||||

| No | 16·9% (14·0–20·3) | 1·00 | .. | 632 | 822 | 9·6% (4·8–18·2) | 109 | 139 | ||

| Yes | 20·3% (18·1–22·8) | 1·25 (0·88–1·76) | .. | 1389 | 1705 | 23·1% (18·0–29·1) | 270 | 345 | ||

| Sexual activity | ||||||||||

| Sexually active in the past 4 weeks | 0·0681 | |||||||||

| No | 16·8% (15·2–18·5) | 1·00 | .. | 2736 | 2469 | 14·7% (11·3–18·9) | 409 | 414 | ||

| Yes | 17·2% (16·0–18·4) | 0·85 (0·71–1·01) | .. | 5168 | 4449 | 20·6% (17·6–24·1) | 866 | 760 | ||

| Satisfied with sex life | <0·0001 | |||||||||

| No | 23·2% (21·5–25·0) | 1·00 | .. | 2999 | 2669 | 20·6% (17·3–24·3) | 669 | 619 | ||

| Yes | 13·5% (12·5–14·7) | 0·45 (0·39–0·52) | .. | 5061 | 4365 | 16·0% (13·0–19·5) | 650 | 591 | ||

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs. All models were adjusted for age and relationship status. Models investigating age and relationship status also adjusted for self-assessed general health status. Models investigating specific conditions were also adjusted for comorbidity, for which comorbidity was coded as 0=0–1 specific conditions and 1=≥2 specific conditions.

General practitioner, sexual health clinic, other clinics or doctors, or psychiatrist or psychologist.

Measure of comorbidity and includes arthritis, heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, broken hip or pelvis bone or hip replacement ever, backache lasting longer than 3 months, any other muscle or bone disease lasting longer than 3 months, depression, cancer, and any thyroid condition treated in the past year.

Heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, other forms of heart disease, and stroke.

Respondents were asked whether they had often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in the past 2 weeks, and whether they had often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things in the past 2 weeks, with a validated two-question patient health questionnaire (PHQ-2).

Women deemed to be postmenopausal when they had not menstruated in the past year, with analysis restricted to those aged 45–64 years.

Overall, 7·0% (95% CI 6·2–7·8) of men and 6·7% (6·1–7·4) of women reported having sought clinical help or advice about their sex life. Seeking clinical help was more common in individuals reporting that a health condition affected their sex lives than in those who did not (men: 23·5% [95% CI 20·3–26·9] vs 3·7% [3·2–4·4]; women: 18·4% [17·5–22·8] vs 4·3% [3·8–4·9]). Most participants who reported seeking help asked a family doctor for advice (men: 85·4%, 95% CI 78·7–90·3; women: 80·7%, 74·9–85·4), with smaller proportions reporting visiting a sexual health clinic (men: 7·6%, 4·5–12·5; women: 11·2%, 8·0–15·5), another type of clinic (men: 6·8%, 4·0–11·3; women: 8·8%, 5·5–13·7), or a psychiatrist or psychologist (men: 6·5%, 3·2–12·5; women: 11·3%, 7·6–16·4; data not shown). A higher proportion of men than women who had reported that their health affected their sex life reported that they had sought clinical advice (Table 4, Table 5). However, the proportions did not vary substantially or consistently by health status (Table 4, Table 5).

Discussion

In our large, population-based study, we have shown that poorer physical health, limiting disabilities, functional impairment, and depressive symptoms are associated with decreased sexual activity and sexual satisfaction and increased reporting of sexual response problems (erectile difficulties and vaginal dryness) in men and women aged 16–74 years in Britain (panel). Furthermore, about 17% of all men and women reported that their health had affected their sex life in the past year. This proportion rose to roughly 60% in participants with bad or very bad health. Less than a quarter of men and a fifth of women who reported that their health affected their sex life had sought clinical help, which was usually from general practitioners rather than specialists. Overall, we have identified strong associations between health and sexual lifestyles, and established that many people are aware of an effect of ill health on their sex life.

Panel. Research in context.

Systematic review

A range of health conditions, disabilities, and drugs affects sexual health and lifestyles.7, 11 The effects are important throughout life, but could be particularly important in older age, when chronic ill health is most common. However, population-based studies in which these issues have been investigated have often had narrow age ranges, few measures of health, and inconsistent findings.3 Moreover, these issues are seldom discussed in clinical practice,11 and the evidence base to guide clinical management and self-help is small.

Interpretation

As far as we are aware, our analysis is the first in which the relationships between sexual lifestyles and health have been studied across a wide age range in men and women, and with a broad range of self-reported health measures. We have shown that health and sexual lifestyles are associated in most sexually active age groups, even after adjustment for age and relationship status. However, we have also shown that many people in poor health and at older ages report an active or satisfying sex life, or both. Many people reported that health conditions had had an effect on their sex lives in the past year—an effect that persisted into older age. This association was significantly higher in participants reporting ill health. However, of individuals reporting a health condition that affected their sex life, only a quarter of men and a fifth of women had sought clinical help or advice. Our findings should help clinicians, their patients, and policy makers to consider the continuation of sexual activity and enjoyment in the face of ill health. Practitioners should consider giving appropriate advice about sexual lifestyles to promote the overall wellbeing of patients with chronic conditions.

Our sample encompasses most of the sexually active lifespan, adding to previous work by emphasising the differences in reported sexual activity according to health status, including at younger ages. For example, the proportion of men aged 35–44 years who reported sexual activity in the past 4 weeks was much lower for those with fair, bad, or very bad health than for those with very good or good health, and similar to the proportion in men reporting good or very good health but 20 years older. We recorded a similar pattern in women, although we noted no difference by health status in the oldest women. This finding could be a result of the low prevalence of sexual activity in older women, and possibly related to their partnership status and their partners' age and health. An area of future research will be to investigate the role of partners' characteristics—eg, through studies of both partners in a relationship. Nevertheless, about a third of men and women in bad or very bad health reported sexual activity in the past 4 weeks, and just less than half of the same group reported satisfaction with their sex lives. Beckman and colleagues21 suggested that more accepting attitudes have contributed to increased reporting of sexual activity in older people; the message that poor health need not mean the end of an active or satisfying sex life is an important one.

Although we sought to minimise reporting bias by using computer-assisted self-interview for the most sensitive questions in addition to non-response weighting,30 our cross-sectional data should be interpreted with caution. We relied on self-reported diagnoses, which can lead to misclassification errors, although previous studies have shown good levels of agreement between self-reported chronic disease and medical records,32, 33 and self-report remains the primary method to assess health status in many large population surveys. Furthermore, the patterns of disease prevalence that we recorded by age and sex were similar to those reported in the Health Survey for England.34 Participants with undiagnosed or preclinical disease could not be identified in our study, which could have meant the effect size was underestimated. Our study did not include physical or biological measures of health, which can be used to validate self-reporting.35 Additionally, we were unable to account for specific drugs or partners' health status, or to explore severity within specific conditions, and we cannot attribute directional causality.

The Natsal-3 sample was broadly representative of the general population of Britain in terms of self-reported general health, marital status, and ethnic origin, on the basis of 2011 census data, after weighting for key sociodemographic characteristics.22, 31 However, the data are susceptible to participation biases—eg, poor health could affect willingness to participate—and the sampling frame did not include individuals in residential or nursing care. Although we have referred to the life course, our findings are not generalisable to people older than 74 years. Our findings at different ages could be partly affected by differences in sexual behaviour between generations.5 In the future, longitudinal studies and investigations including biological and physical measures of health will be important in the refinement of our understanding and establishment of causality. Nevertheless, the strength and novelty of our study lie in its size, population representativeness, and broad range of detailed sexual lifestyle measures. Importantly, we could explore the associations between sexual lifestyles and health, with measures of both broad health and specific conditions, independently of the key confounders of age and partnership status. This Article builds a compelling and consistent picture showing the strong associations between sexual lifestyles and health across the life course.

Although our findings are consistent with previous reports,4, 8, 10, 13, 14, 36 not all studies have reached the same conclusions about the associations with general health, particularly in women. A large Spanish cross-sectional survey of people older than 65 years8 showed that sexual activity was associated with self-assessed general health status in men but not women. A US study11 showed that poor physical health did not contribute to the age-related decrease in sexual frequency in women aged 44–72 years, although health did contribute in men. Additionally, another US study37 showed that ill health was unrelated to frequency of sexual activity in retired men and women older than 45 years. However, these studies were restricted in age range, and, by including a wide age range and using a large sample size, we were able to identify the associations with ill health separately from those with age. With adjustment for age and additionally for the availability of partners and comorbidities, we noted strong associations between sexual lifestyles and some specific chronic health conditions. Our data support other studies linking mental ill health and sexual problems.8, 13, 14 Diabetes was associated with reduced sexual activity in men but not women, but we note other studies showed associations only for women,4, 17 which could be a result of differences in methods used. In our study, hypertension was not associated with sexual activity, satisfaction, or sexual responses, although other studies—in some of which investigators used sphygmomanometry—have shown that sexual activity is reduced in women with hypertension,18 but not in men.13, 18

To our knowledge, no other large population survey of sexual lifestyles has investigated whether people felt that a health condition affected their sexual activity or enjoyment. Reporting of a health condition that affected an individual's sex life increased in each age group in men but not women. These findings are consistent with previous work suggesting that an impaired sexual response is less likely to be problematic for older women than younger women.38

Most people reporting a condition affecting their sex life in the past year had not sought clinical advice. When they had, they consulted general practitioners or family doctors and seldom specialists, which corroborates findings that general practitioners are often the first point of contact for sexual concerns.39 Evidence suggests that, although many major health conditions are recognised to affect sexual function,40 clinical advice about the effect of ill health on sexual activity is often not given, even when the condition is gynaecological or genital,41, 42 and doctors rarely ask patients about their sexual function.43 Not only are patients sometimes unwilling to discuss problems, but health-care professionals might also have poor awareness and little training about advising and communicating with patients about sexual problems.44 This issue needs to be addressed, because sexual problems are common and can cause distress,30 can indicate underlying physical or mental health problems, and can be caused iatrogenically (eg, by drugs or surgery).45 Our findings indicate that many patients with chronic ill health are already aware that their health has an effect on their sex lives. Therefore, awareness needs to increase, guidance improve, and communication skills built so that problems are acknowledged, ameliorated, and openly discussed in appropriate ways.

On the one hand, people are living longer and have expectations of continued sexual fulfilment as they age.46, 47 But on the other hand, ill health increases in old age; the proportion of the English population reporting one or more chronic conditions rises from 17% in individuals younger than 40 years to 60% in those older than 60 years.48 The sexual health of older people has been a neglected area of research.44, 47, 49 More recent public health policy, such as a WHO 2013 report,50 reflects an increasing awareness of the interdependence between sexual health and general health. A UK Department of Health 2013 report51 drew attention to the effects of long-term health conditions on erectile function and the effect of cancer on sexual health in older age. Our study suggests that strategic frameworks could go further and include associations between health—eg, disabilities or mental health—and sexual lifestyles at younger ages, as well as the broader associations between sexual lifestyles and chronic ill health.

Sexual lifestyles are strongly linked to overall health and wellbeing. The finding that many people who felt that their health affected their sex life seldom sought clinical help suggests an unmet clinical need that is inadequately recognised in present medical practice and health policy. Our data should help to challenge stereotypes and inform sexual policy for all ages.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Natsal-3 is a collaboration between University College London (London, UK), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, UK), NatCen Social Research, Public Health England (formerly the Health Protection Agency), and the University of Manchester (Manchester, UK). The study was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council (G0701757) and the Wellcome Trust (084840), with contributions from the Economic and Social Research Council and Department of Health. NF is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Lectureship, and KGJ is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Methodology Fellowship. We thank the study participants; the team of interviewers from NatCen Social Research who did the interviews; Heather Wardle, Vicki Hawkins, Cathy Coshall, and operations and computing staff from NatCen Social Research; and Graham Hart and the reviewers for valuable comments on early drafts of the report.

Contributors

NF, CHM, PS, and AMJ conceived this Article. NF wrote the first draft of the Article, with further contributions from CHM, PS, CT, SC, KRM, BE, WM, FW, JD, KW, and AMJ. NF did statistical analyses, with support from CHM, CT, KGJ, and PP. CHM, PS, BE, WM, FW, AJC, KW, and AMJ, initial applicants for Natsal-3, wrote the study protocol and obtained funding. NF, CHM, PS, CT, SC, KRM, BE, WM, FW, JD, AJC, AP, KW, and AMJ designed the Natsal-3 questionnaire, applied for ethics approval, and undertook piloting of the questionnaire. SC, BE, and AP were responsible for data collection and delivery. CHM, CT, SC, PP, and AP managed data. All authors contributed to data interpretation, reviewed successive drafts, and approved the final version of the report.

Conflicts of interest

AMJ has been a Governor of the Wellcome Trust since 2011. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Results of over 45,000 respondents, recording the dramatic changes in our sexual lifestyles over the past 60 years.

References

- 1.DeLamater J. Sexual expression in later life: a review and synthesis. J Sex Res. 2012;49:125–141. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.603168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison SL, Bell RJ, LaChina M, Holden SL, Davis SR. The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2690–2697. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan HM, Tong SF, Ho CCK. Men's health: sexual dysfunction, physical, and psychological health—is there a link? J Sex Med. 2012;9:663–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O'Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercer CH, Tanton C, Prah P. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and trends over time: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal) Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8. published online Nov 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Field J, Wellings K. Sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Blackwell; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson AM, Mercer CH, Erens B. Sexual behaviour in Britain: partnerships, practices, and HIV risk behaviours. Lancet. 2001;358:1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palacios-Ceña D, Carrasco-Garrido P, Hernández-Barrera V, Alonso-Blanco C, Jiménez-García R, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Sexual behaviors among older adults in Spain: results from a population-based national sexual health survey. J Sex Med. 2012;9:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14–94. J Sex Med. 2010;7(suppl 5):255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richters J, Grulich AE, de Visser RO, Smith AMA, Rissel CE. Sex in Australia: sexual difficulties in a representative sample of adults. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2003.tb00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karraker A, Delamater J, Schwartz CR. Sexual frequency decline from midlife to later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66:502–512. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kontula O, Haavio-Mannila E. The impact of aging on human sexual activity and sexual desire. J Sex Res. 2009;46:46–56. doi: 10.1080/00224490802624414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]