Abstract

Adjuvants based on aluminum salts (Alum) are commonly used in vaccines to boost the immune response against infectious agents. However, the detailed mechanism of how Alum enhances adaptive immunity and exerts its adjuvant immune effect remains unclear. Other than being comprised of micron-sized aggregates that include nanoscale particulates, Alum lacks specific physicochemical properties to explain activation of the innate immune system, including the mechanism by which aluminum-based adjuvants engage the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β production. This is putatively one of the major mechanisms required for an adjuvant effect. Because we know that long aspect ratio nanomaterials trigger the NLRP3 inflammasome, we synthesized a library of aluminum oxyhydroxide (AlOOH) nanorods to determine whether control of the material shape and crystalline properties could be used to quantitatively assess NLRP3 inflammasome activation and linkage of the cellular response to the material’s adjuvant activities in vivo. Using comparison to commercial Alum, we demonstrate that the crystallinity and surface hydroxyl group display of AlOOH nanoparticles quantitatively impact the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in human THP-1 myeloid cells or murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). Moreover, these in vitro effects were correlated with the immunopotentiation capabilities of the AlOOH nanorods in a murine OVA immunization model. These results demonstrate that shape, crystallinity and hydroxyl content play an important role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation and are therefore useful for quantitative boosting of antigen-specific immune responses. These results show that the engineered design of aluminum-based adjuvants in combination with dendritic cell property-activity analysis can be used to design more potent aluminum-based adjuvants.

Keywords: NLRP3 Inflammasome, IL-1β, Aluminum Oxyhydroxide, Oxidative Stress, Vaccine Adjuvant, Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses, Alum

Vaccination remains one of the most effective tools to prevent infectious disease.1–3 In addition to ensuring that the best possible antigenic components are included to stimulate a cognitive immune response, appropriate consideration should also be given to vaccine adjuvants that can reproducibly boost antigen presentation. In addition to traditional chemical and biological components such as aluminum salts (Alum), liposomes, polymers, microbial derivatives, and cytokines,4, 5 engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) are rapidly emerging as a new class of adjuvants that allows tuning of the immune responses to facilitate antigen delivery, activate or modulate antigen presenting cell (APC) activity, recruit dendritic cells and/or lead to direct antigen targeting of regional lymph nodes.6–9 The use of ENMs for vaccine development include polyethyleneimine (PEI),10 poly(D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA),11, 12 silica,13, 14 multilamellar lipid vesicles,15 liposomes,16 and hydrogels.17

In this communication, we address the nanoscale design of aluminum-containing adjuvants. Alum, depending on the commercial source, is composed of aluminum hydroxide, aluminum phosphate, or a mixture of aluminum and magnesium hydroxides.18, 19 Alum has a long track record as a safe and efficient adjuvant for clinical use, including be used currently in DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and papilloma virus vaccines.19–21 While “Alum” is classically thought of as aluminum hydroxide, X-ray diffraction analysis and infrared spectroscopy have identified aluminum hydroxide adjuvant as crystalline aluminum oxyhydroxide, AlOOH.22 AlOOH adjuvants are composed of nano-length scale plate-like primary particles that form aggregates, representing the functional subunits in the material. These aggregates are porous and have irregular shapes that range from 1–20 μm in diameter.22 Upon mixing with antigen, the aggregates are broken into smaller fragments that can re-aggregate to distribute the absorbed antigen throughout the vaccine. While it is known that Alum tightly binds to antigens and provides slow release of antigens as a result of this material’s astringent characteristics, the specific structural details of how the physicochemical properties of the material lead to immunopotentiation are unclear.22 According to one source, the size dimensions of the Alum aggregates could determine the abundance of antigen internalization by the APC.23 Recently, it was shown that Alum could activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β production, which could explain its ability to induce local inflammation, recruitment of APCs, enhanced antigen uptake, dendritic cell maturation, and stimulation of T-cell activation and T-cell differentiation.24,19 While the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome as the primary event leading to in vivo adjuvancy is still controversial,25–27 it is noted that long aspect ratio (LAR) ENMs (e.g., nanowires and carbon nanotubes) trigger activation of the inflammasome secondary to shape-dependent and oxidative stress effects at lysosomal level.28, 29 It is possible, therefore, that the adjuvant effects of aluminum-based adjuvants could depend on shape and that tuning of the material’s aspect ratio could be used to increase inflammasome activation in dendritic cells in vitro and in vivo. A rigorously controlled structure-based adjuvant may also allow us to address the controversy regarding whether activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is essential for inducing immunopotentiating effects in vivo.24–27, 30

In this study, we synthesized a comprehensive library of γ-phase aluminum oxyhydroxide (γ-AlOOH, boehmite) nanomaterials for comparison to commercial Alum. While γ-AlOOH is a major component of most aluminum salt-based adjuvants, our well-characterized library of materials allowed us to study the role of material shape, crystallinity and surface reactivity as tunable features to trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation in THP-1 cells and murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). Some of these materials were chosen to study the relationship of the in vitro dendritic cell (DC) response to boosting the immune response to ovalbumin (OVA) in vivo. We also used adoptive DC transfer to demonstrate that ex vivo boosting of APC activity predicts the ability of AlOOH nanorods to exert an adjuvant effect in intact animals. We demonstrate that the crystallinity, hydroxyl content and ability of AlOOH nanorods to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and IL-1β production are good structure-activity relationships (SARs) on which to base the design of an improved aluminum adjuvant. These results demonstrate that the engineered design of aluminum-based adjuvants, in combination with structure-activity analysis, can be used to develop more potent aluminum-based adjuvants.

RESULTS

Synthesis and Physicochemical Characterization of AlOOH Nanoparticles

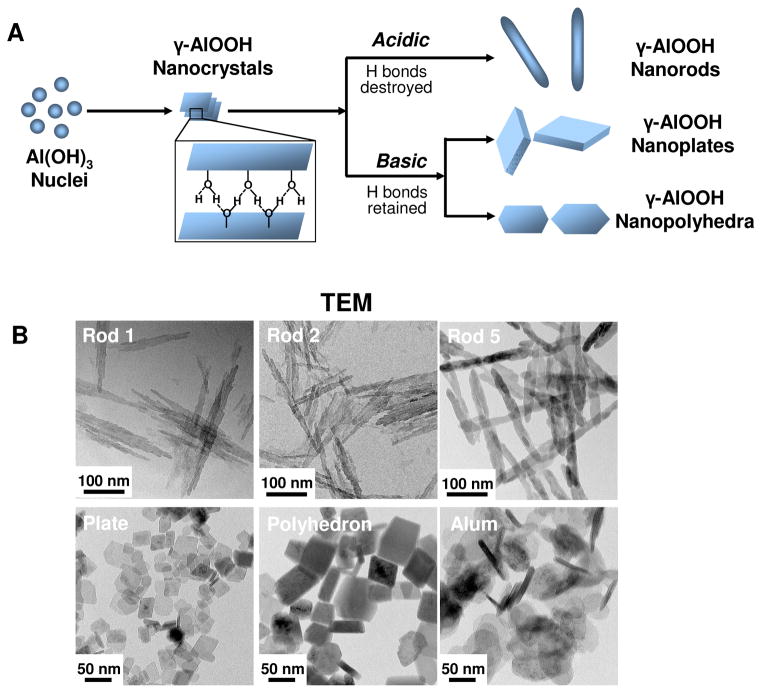

A comprehensive library of γ-phase aluminum oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (γ-AlOOH, boehmite) with variation in shape and crystal structure was established using a hydrothermal method. This library of nanoscale rods, plates, and polyhedra was prepared through precise control of the pH and the composition of the synthesis mixtures, which were devoid of surfactants or organic components. The influence of pH on particle morphology can be attributed to the characteristic γ-AlOOH structure, which is composed of octahedral AlO6 double layers. Since the interaction between the octahedral double layers is weaker than the interactions within each layer, crystal cleavage of the double layers produces a crystalline surface totally covered with hydroxyl groups. Because of the free orbital in the oxygen atom of each hydroxide, the formation of hydrogen bonds is capable of sustaining lamellar structures such as nanoplates or nanopolyhedra under basic conditions.31 However, reaction of the free orbitals with protons under acidic conditions leads to the formation of aquo-ligands, which destroy the lamellae, leading to the formation of rod-like structures.32 A schematic representation explaining the principles of AlOOH nanoparticle formation is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the synthetic chemistry and TEM analysis of AlOOH nanoparticles.

(A) Schematic representation of the synthetic chemistry and mechanisms of AlOOH nanoparticle formation under acidic and basic conditions. (B) Representative TEM images of AlOOH nanorods obtained after a synthesis period of 2 h (Rod 1), 3 h (Rod 2), and 24 h (Rod 5). AlOOH nanoplates were synthesized using a reaction time of 24 h, while nanopolyhedra were generated after a reaction time of 72 h. All synthesis was conducted at 200 °C. The TEM image of commercial Alum, used as control material, is also shown. The images were taken with a JEOL 1200 EX TEM with an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

TEM analysis (Figures 1B and S1) shows that the as-synthesized samples are composed of a series of nanoparticles with uniform size and morphology. Particles prepared at pH 5 were rod-shaped (Rods 1–5), with an average diameter of ~20 nm and lengths of 150–200 nm. In contrast, particle synthesis at pH 10 catalyzed the formation of nanoplates, with an average width of ~30 nm and thickness of ~8 nm (Figures 1B and S1). The polyhedral particles, synthesized at pH 9, were in the size range of 30–60 nm. XRD analysis demonstrated that the entire material phase was orthorhombic boehmite, without displaying diffraction peaks indicative of any impurities. The crystallinity of the rod-shaped particles could be finely tuned through the control of synthesis time and reaction temperature. For instance, 2 h hydrothermal treatment of the synthesis mixture (pH 5) at 200 °C led to the formation of AlOOH nanorods with an extremely low degree (~6%) of crystallinity (Figure 2A). However, as the synthesis reaction was allowed to continue, the crystallinity gradually increased to 21%, 45 % and 79% at 3, 4 and 6 h, respectively (Figure 2A). 100% crystallinity was obtained after 16 h. In contrast, similar crystallinity control could not be achieved for nanoplates and nanopolyhedra because of a more rapid rate of crystallization under basic conditions (100% crystallinity after 2 h, Figure S2A). Commercial Alum (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), which was used as a control material throughout our study, exhibited a plate-like morphology (Figure 1B), with a relatively low level of crystallinity (Figure S2A). XRD analysis also demonstrated multiple phases in Alum, indicative of the presence of magnesium hydroxide and aluminum oxide hydrate (Figure S2A).

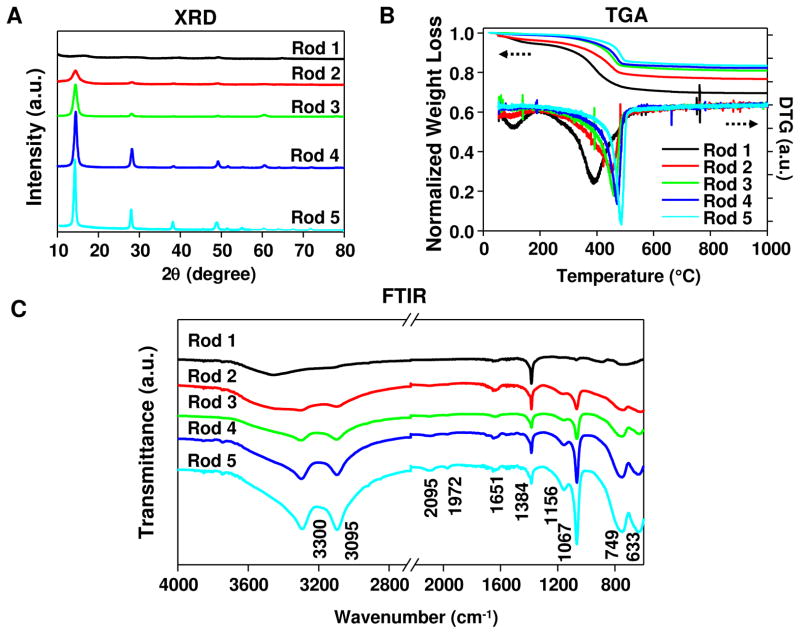

Figure 2. XRD, TGA and FTIR analysis of AlOOH nanorods.

(A) XRD patterns of the nanorods. (B) TGA and DTG analyses of the nanorods. (C) FTIR spectra of the nanorods.

To characterize the content of hydroxyl groups at the particle surface, TGA analysis was performed and demonstrated significant weight loss over 20–1000 °C (Figure 2B). This amounted to 30.4, 23.2, 19.0, 17.7, and 16.5 % weight loss for Rods 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. All samples showed higher weight loss than the theoretical (~15 wt%) loss that was expected for the transformation of AlOOH to Al2O3. This suggests that these particles, from inception, carry a relatively high water content and hydroxyl display on their surfaces. The first derivative TGA curve (DTG in Figure 2B) demonstrates the emergence of two weight loss stages over the applied temperature range. The first stage, leading to a weight loss of 0.5–2.9 wt% at ~100 °C, can be attributed to the desorption of water from the particle surface. The second stage, showing a weight loss of 13.6–24.8 wt% at 395–485 °C, can be attributed to the removal of interstitial water and hydroxyl groups on the AlOOH nanorods.33 Generally speaking, particles of lower crystallinity tend to have higher weight loss at the second stage and the dehydroxylation occurs at a relatively lower temperature. Since the dehydroxylation process starts with the diffusion of protons and reaction with hydroxyl ions to form water, followed by desorption from the internal surface, it is possible that the diffusion occurs much easier in the lower-crystallinity particles (therefore requiring a lower dehydroxylation temperature). The ~2 wt% weight loss above 500 °C presents the hydroxyl content of the converted product (Al2O3), and is similar for all particles. Consistent with the XRD results, all nanoplates and nanopolyhedra showed relatively low weight loss by TGA analysis (16.0–19.0 wt% for the plates and 16.1 wt% for the polyhedra) because of high crystallinity. In contrast, Alum displayed a multi-stage TGA profile with the total weight loss up to 37 wt.%, which could be attributed to the dehydroxylation and/or decomposition of various active components in the product (Figure S2B), suggesting that Alum is composed of different materials.

To further characterize the particle structure, FTIR analysis was performed (Figures 2C and S2C). Figure 2C shows the FTIR spectra of all AlOOH nanorods in the 600–4000 cm−1 region. Two strong bands at 3300 and 3095 cm−1 can be ascribed to the asymmetric (νas(Al)O-H) and symmetric (νs(Al)O-H) stretching vibration of OH groups in AlOOH particles.34 Similarly, the two bands at 1156 and 1067 cm−1 are assigned to asymmetric (νasAl-O-H) and symmetric (νsAl-O-H) OH deformation. Torsion modes at 749 and 633 cm−1 are also observed in the spectra. All six bands listed above are characteristic of crystalline AlOOH, therefore a gradual increase in their intensities from Rod 1 to 5 suggests increased crystallinity with prolonged synthesis time; this is in good agreement with the XRD data. Two weak bands at 2095 and 1972 cm−1 represent combination bands (i.e., sum of multiple vibration bands)34, which also show a slight increase in intensity from Rod 1 to 5. The band at 1384 cm−1 corresponds to the presence of a small amount of nitrate ions carried through the synthesis mixture containing Al(NO3)3. The 1651 cm−1 band is attributed to the bending mode of adsorbed water. The low intensity of this band indicates a very small amount of physically adsorbed water in the AlOOH nanorods, which is consistent with the TGA results. FTIR spectra of AlOOH nanoplates and nanopolyhedra also exhibited characteristic AlOOH bands (Figure S2C). In contrast, FTIR analysis of Alum showed various unidentified peaks, confirming that Alum is a mixture of different materials without defined structure.

Because the biological experiments are carried out in aqueous media, we determined the hydrodynamic size and surface charge of the nanoparticles in a variety of solutions. The hydrodynamic sizes of AlOOH nanoparticles in water and complete cell culture medium (RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS) or PBS supplemented with 0.2 mg/ml OVA (for in vivo studies) were determined using dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Table 1). Although DLS is not accurate for LAR materials, we have previously shown that this technique can be used to compare the agglomeration states of LAR materials like CeO2 nanorods and MWCNTs.29, 35 The size of nanorods in water ranged from 244 nm to 810 nm, among which the materials with lower crystallinity tended to form bigger agglomerates. The average sizes of the nanoplates and nanopolyhedra were 93 nm and 333 nm, respectively. The hydrodynamic sizes of the particles in protein supplemented RPMI or PBS were similar to those in water.

Table 1.

Hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of AlOOH nanoparticles

| Sample | Hydrodynamic Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Water | RPMI-1640 & 10% FBS | PBS&0.2% OVA | Water | RPMI-1640 & 10% FBS | PBS&0.2% OVA | |

| Rod 1 | 810±67 | 957±89 | 717±8 | 39±2 | −6±8 | −14±19 |

| Rod 2 | 592±50 | 522±74 | 406±15 | 32±3 | −10±4 | −7±5 |

| Rod 3 | 451±20 | 552±36 | 297±2 | 36±3 | −10±8 | −14±6 |

| Rod 4 | 434±27 | 504±11 | 330±2 | 33±3 | −13±4 | −8±4 |

| Rod 5 | 244±17 | 320±15 | 228±4 | 48±1 | −8±1 | −16±6 |

| Plate | 93±3 | 159±10 | 180±7 | 50±1 | −4±1 | −2±5 |

| Polyhedron | 333±25 | 711±40 | 535±48 | 30±2 | −4±7 | −9±8 |

| Alum | 452±32 | 315±1 | 686±61 | −3±1 | −8±2 | −15±3 |

The surface charge of particles was also determined by measuring zeta potential (Table 1). All AlOOH nanoparticles exhibited positive surface charges in water, which may facilitate the electrostatic binding of negatively charged proteins in the medium. This is likely the reason why the zeta potential of most of the materials became negative (around −10 mV) when incubated with complete culture medium or PBS supplemented with OVA (Table 1).36 Commercial Alum was negatively charged in all media, suggesting the contribution of materials other than AlOOH.

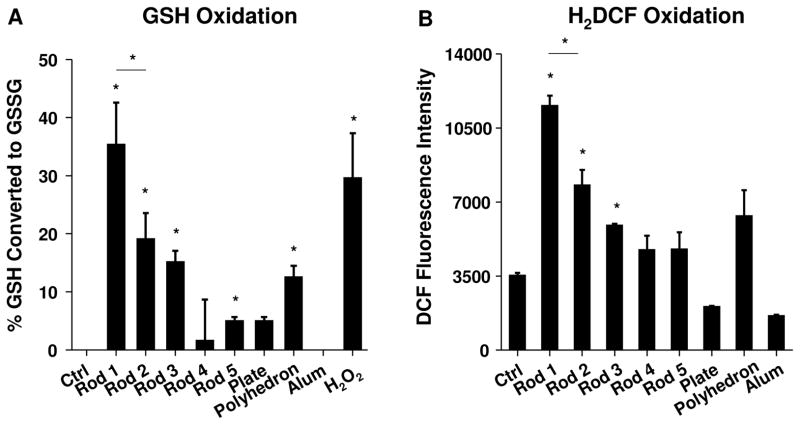

The high hydroxyl content of our specially synthesized AlOOH materials make these nanoparticles highly reactive, including the ability to generate ROS.37 We used Ellman’s reagent to compare the ability of various nanoparticles to abiotically oxidize glutathione (GSH) (Figure 3A). This demonstrated that an incremental increase in hydroxyl content as a result of the decreased crystallinity is accompanied by a progressive decline in GSH content when nanorods are introduced into the reaction mixture. Also, the higher crystallinity of nanoplates and nanopolyhedra was accompanied by a low oxidation potential, while commercial Alum had minimal oxidative effects (Figure 3A). We also conducted a DCF assay to directly measure ROS generation by the nanoparticles (Figure 3B). This confirmed that the abundance of abiotic ROS production is commensurate with the extent of GSH consumption (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Abiotic ROS generation by AlOOH nanoparticles.

(A) Abiotic oxidation of GSH by AlOOH nanoparticles was conducted with Ellman’s reagent, which measures reduced glutathione (GSH). 1.6 mg/ml AlOOH NPs was incubated with 4.5 mM GSH in a volume of 150 μl in the wells of a 96-well plate for 30 min at 37 °C. Absorbance was read at 414 nm using a plate reader. H2O2 (4 mM) was used as a positive control. *p<0.05 compared to control sample without particles. (B) Abiotic ROS generation potential of AlOOH nanoparticles was conducted using H2DCF. 25 μg/ml AlOOH nanoparticles were incubated with H2DCF working solution in a volume of 100 μl in a 96-well plate at room temperature for 3h. Fluorescence was measured at Ex492/Em527 nm by microplate reader. *p<0.05 compared to control sample without particles.

AlOOH Nanoparticles Induce NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation through a Lysosomal Process that Involves Generation of Oxidative Stress

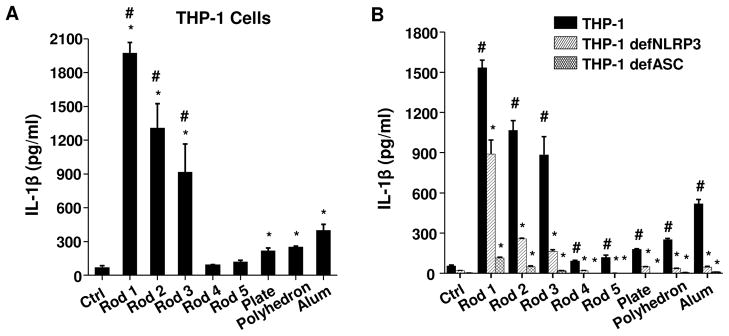

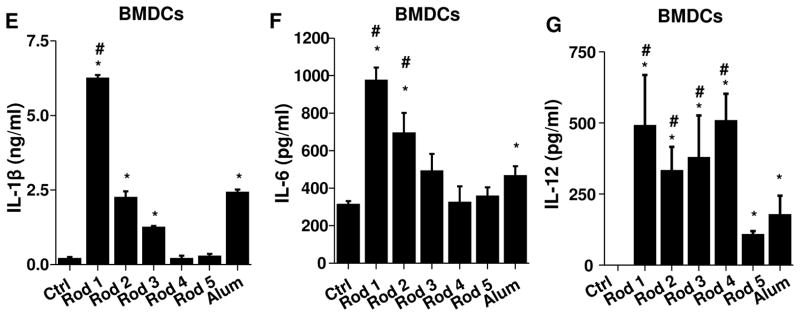

Nanoparticle effects on NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production were studied by using the human myeloid cell line THP-1, which is frequently used for studying ENM impact on the assembly of this pro-inflammatory structure.38 PMA (1 μg/ml) was used to differentiate the THP-1 cells into macrophages.28, 29, 37 LPS (10 ng/ml) was added to prime the cells to produce pro-IL-1β, which were measured in cellular extracts by an ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). This demonstrated similar levels of expression of pro-IL-1β across all cell samples irrespective of exposure to AlOOH (Figure S3). We performed a MTS assay to rule out the generation of cytotoxicity by AlOOH nanoparticles and Alum (Figure S4). We also assessed endotoxin levels of the AlOOH nanorods and Alum to eliminate endotoxin contamination. The endotoxin levels were below 0.2 EU/ml (Figure S5), showing absence of bacterial contamination. Subsequent assessment of IL-1β production demonstrated that Rods 1–3 could induce significantly higher levels of IL-1β release into the cellular supernatant compared to Rods 4 and 5, nanoplates, or nanopolyhedra (Figure 4A). Rods 1–3 also induced significantly higher IL-1β production than commercial Alum. Please notice that during performance of cellular studies, we used 250 or 500 μg/ml as the administered dose since these quantities have been used consistently in the literature to study NLRP3 inflammasome activation.24, 25, 39, 40 This is confirmed by our dose response analysis as shown for Rods 1–3 in Figure S6. The generation of this cytokine response by the rods and Alum was markedly suppressed in NLRP3-deficient (defNLRP3) and ASC-deficient (defASC) THP-1 cells (Figure 4B), confirming the involvement of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Because of the low level of IL-1β production, nanoplates and nanopolyhedra were omitted from subsequent in vitro studies.

Figure 4. IL-1β production and oxidative stress induced by AlOOH nanoparticles in THP-1 cells.

(A) THP-1 cells were exposed to AlOOH nanorods, AlOOH nanoplates and AlOOH nanopolyhedra at 500 μg/ml for 6 h. Cells exposed to Alum (500 μg/ml) were used as a control. IL-1β production in response to the nanoparticles was quantified by ELISA. *p<0.05 compared to control; #p<0.05 compared to Alum. (B) THP-1, NLRP3-deficient (defNLRP3) and ASC-deficient (defASC) THP-1 cells were exposed to AlOOH nanoparticles and Alum (500 μg/ml) for 6 h, and the IL-1β production was determined by ELISA. *p<0.05 compared to wild type THP-1 cells treated with the same materials; #p<0.05 compared to control. (C) Intracellular GSH levels in THP-1 cells after exposure to AlOOH nanorods. THP-1 cells were exposed to 500 μg/ml AlOOH nanorods for the indicated time period and intracellular GSH level was determined using a GSH-Glo assay. Zinc oxide (ZnO) (50 μg/ml) was used as a positive control. *p<0.05 compared to control. (D) The antioxidant, NAC, suppressed the IL-1β production induced by AlOOH nanorods in THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were pre-treated with 25 mM NAC for 30 min and then exposed to AlOOH nanorods for 6 h. IL-1β production was determined by ELISA. *p<0.05 compared to THP-1 cells without NAC treatment; #p<0.05 compared to control.

Because activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by LAR materials is known to depend on direct physical interaction with the cell,38 we assessed the cellular uptake of the AlOOH nanorods by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and flow cytometry. The TEM images showed that all AlOOH nanorods were taken up into membrane-lined vesicles in THP-1 cells (Figure S7A). Because TEM analysis is not quantitative, we performed a flow cytometry study using FITC-labeled Rods. We found that Rods 1 and 2 were taken up in significantly higher quantities than Rods 3–5 (Figure S7B). This could be explained by the larger agglomeration of Rods 1 and 2 as shown by TEM (Figure S7A). To confirm that cellular uptake is important for inflammasome activation, the actin polymerization inhibitor, cytochalasin D (Cyto D) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), was used to show that interference in rod uptake is accompanied by reduced IL-1β production (Figure S7C). Following phagocytic uptake in macrophages and THP-1 cells, we have previously shown that LAR materials (e.g., CeO2 nanowires, asbestos, and carbon nanotubes) enter the lysosomal compartment, where membrane damage and cathepsin B release act as upstream signals that contribute to NLRP3 inflammasome activation.28, 29, 38 We used confocal microscopy to see if the AlOOH nanorods have the same effect on THP-1 cells by following the release of the cathepsin B from the lysosome to the cytosol. Exposure of the cells to Rods 1–3 demonstrate cytosolic release of this enzyme, while in the case of Rods 4 and 5, the Magic Red (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, Bloomington, MN) staining was contained as punctate red fluorescence dots in intact lysosomes (Figure S8A). Alum could also induce cathepsin B release, which is consistent with a previous report.40 The role of cathepsin B release in inflammasome activation was confirmed by showing suppression of IL-1β production by a cathepsin B-specific inhibitor, CA-074-Me (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (Figure S8B).

To determine whether the pro-oxidative effects of the AlOOH nanorods, as demonstrated by Ellman’s reagent and H2DCF, can be confirmed at cellular level, we assessed whether the nanorods induce cellular ROS production and oxidative stress in THP-1 cells. Assessment of cellular GSH levels demonstrated that while Rods 1 and 2 could significantly elevate cellular GSH levels at 6 h, all rods ultimately induced a small but significant decrease by 24 h (Figure 4C). The early increase in GSH levels likely reflects an induced antioxidant response in response to low level ROS production, which leads to transcriptional activation of the Nrf2 transcription factor.41 Nrf2 induces the expression of multiple antioxidant enzymes, including phase II enzymes involved in GSH synthesis.41 Similar to previously published data,42 the use of zinc oxide (ZnO) as a positive control demonstrated a significant decrease in cellular GSH levels, which indicates an injurious oxidative stress response when the antioxidant defense is overwhelmed (Figure 4C). Further assessment of mitochondrial superoxide production by MitoSOX staining demonstrated that Rods 1–3 induce significantly more ROS production than other rods (Figures S9). Alum also induced ROS production. To confirm the role of oxidative stress, pretreatment of the cells with the radical scavenger and glutathione precursor, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) (American Regent, Shirley, NY), demonstrated suppression of mitochondrial ROS production (Figure S9). Moreover, IL-1β production by Rods 1–3 was also significantly suppressed by NAC (Figure 4D). All considered, these data demonstrate the contribution of ROS generation to lysosomal damage and NLRP3 inflammasome activation by Rods 1–3.

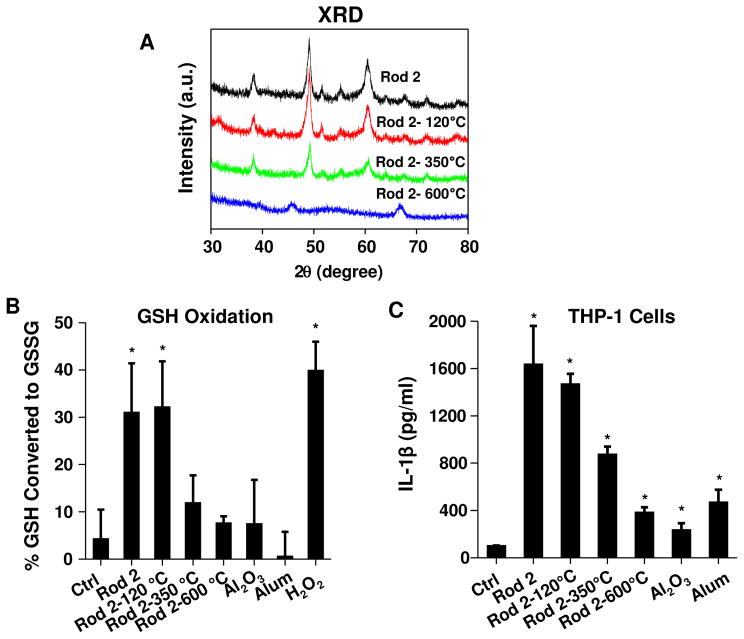

In order to confirm the role of crystallinity and the hydroxyl display on nanorods towards ROS generation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, Rod 2 was selected to show whether heating of material and reduction of the hydroxyl content would impact the biological responses. The heating temperatures were chosen based on the TGA analysis (Figure 2B). Although heating up to 600 °C did not affect the rod morphology (TEM data, not shown), there was a change in the crystal structure according to XRD patterns (Figure 5A). This is evidenced by the loss of the characteristic AlOOH peaks and the appearance of Al2O3 diffraction peaks at 2θ of 45.7 and 66.9° at 600 °C. Use of Ellman’s reagent demonstrated that removal of physically adsorbed water without changing crystal structure by heating to 120 °C did not change the material’s pro-oxidative activity (Figure 5B). However, as the temperature rose above 350 °C, a dramatic reduction in hydroxyl content (TGA analysis, Figure 2B) was accompanied by a significant decline in pro-oxidative activity (Figure 5B). At 600 °C, the bulk of material was transformed to an Al2O3 phase, which was almost totally lacking in oxidant activity (Figure 5B). Consistent with these results, IL-1β production by Rod 2 showed a progressive decline during incremental heating of this material (Figure 5C). These results show that crystallinity and the hydroxyl group content in AlOOH nanorods affect the redox potential, which plays a role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Figure 5. IL-1β production correlates with the hydroxyl content of the AlOOH nanorods.

(A) XRD patterns of the AlOOH Rod 2 after thermal treatment. Rod 2 was calcined at the indicated temperature for 2 hours and then subjected to XRD analysis. (B) Abiotic GSH oxidation as determined by Ellman’s reagent. (C) IL-1β production in THP-1 cells induced by thermally treated Rod 2. *p<0.05 compared to control.

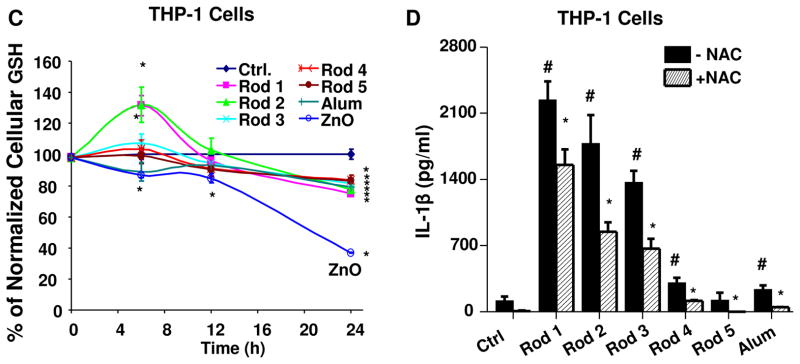

AlOOH Nanorods Induce the Maturation and Cytokine Production in Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells (BMDCs)

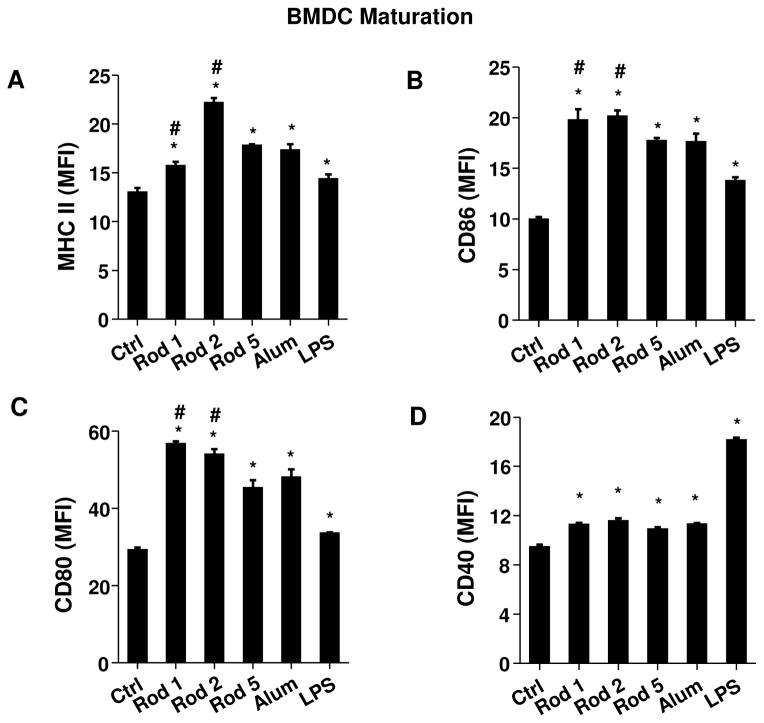

To verify the structure-activity analysis in THP-1 cells, we determined whether AlOOH nanorods could stimulate BMDCs ex vivo. Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional APCs that play a key role in the adjuvant effect of vaccines.43 First, we assessed the cytotoxic effects of AlOOH nanorods on BMDCs. As shown in Figure S10, neither AlOOH nanorods nor Alum had significant toxic effects on BMDCs. Since Alum has been reported to induce DC maturation,44 flow cytometry analysis was performed to examine the expression of the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) on CD11c+ DCs (Figures 6A and S11A). This demonstrated that while all nanorods are capable of inducing MHC-II expression, the effect of Rod 2 was significantly higher than that of Alum or other Rods. Exposure to the nanorods also significantly induced the expression of the co-stimulatory molecules, CD86, CD80 and CD40 (Figures 6B–6D and S11B–S11D). Both Rods 1 and 2 induced significantly higher levels of CD86 (Figures 6B and S11B) and CD80 (Figures 6C and S11C) expression compared to Alum, while the CD40 expression level was comparatively minor (Figures 6D and S11D).

Figure 6. Mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cell (BMDC) maturation and cytokine production.

BMDCs were exposed to AlOOH nanorods (100 μg/ml) for 16 h. Surface membrane expression of (A) MHC-II, (B) CD86, (C) CD80 and (D) CD40 on CD11c+ cells was determined by flow cytometry. LPS-treated (10 ng/ml) BMDCs were used as a control. (E) IL-1β, (F) IL-6 and (G) IL-12 production in response to AlOOH nanorods (500 μg/ml) for 8 h in the presence of 10 ng/ml LPS were quantified by ELISA. *p<0.05 compared to control; #p<0.05 compared to Alum.

We also assessed cytokine production in BMDCs. This demonstrated that Rods 1–3 induced IL-1β production that varied with these materials’ hydroxyl content (Figure 6E). This response was also dose-dependent (Figure S12). In addition to IL-1β, AlOOH nanorods induced IL-6 and IL-12 production (Figures 6F–6G). IL-6 has been reported to be involved in the generation of Th2 immune responses by Alum.45 In contrast, IL-12 is a Th1 polarizing cytokine.46 The trend for IL-12 production differs from IL-1β and IL-6. This is likely due to IL-12 production involving multiple signaling pathways including Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4),47–50 while TLR4 is the major pathway for the production of IL-1β and IL-6. To confirm the role of oxidative stress in cytokine production, pre-treatment with NAC was used to show that the generation of IL-1β in BMDCs was suppressed (Figure S13A). In addition, the reduction of hydroxyl content in Rod 2 by heating to 600 °C also decreased IL-1β production (Figure S13B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that AlOOH nanorods are capable of inducing BMDC maturation and cytokine production that can be predicted by the material’s physicochemical properties.

Vaccination with AlOOH Nanorods Induce Adaptive Humoral Immune Responses

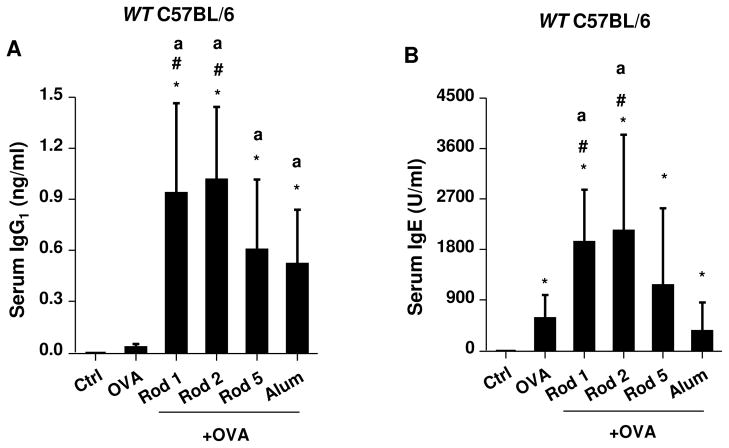

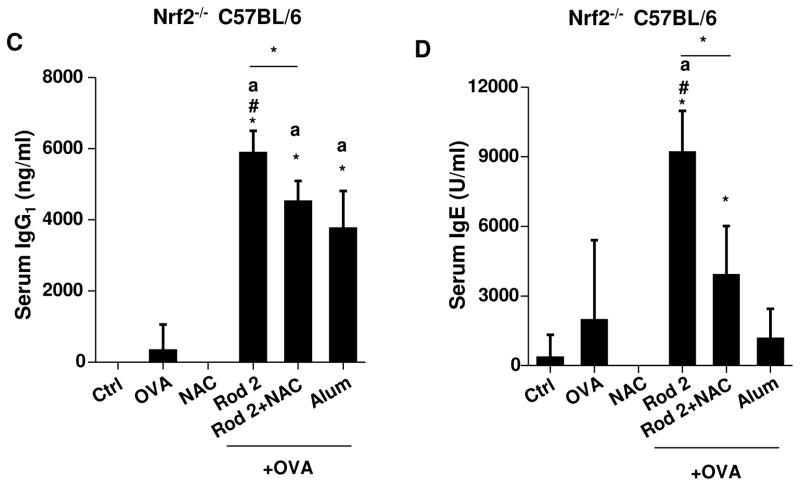

Because of their in vitro potency in cellular ROS generation and IL-1β production, Rods 1 and 2 were chosen to perform a comparative analysis with Rod 5 and Alum. Mice were selected as the animal model, because their genetic and immunological characteristics closely parallel human physiology.51, 52 Endotoxin-free OVA (BioVendor R&D, Asheville, NC) was used as the antigen for generating antigen-specific antibody responses in mice 2 weeks after receiving intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, in the absence or presence of the adjuvant. Binding affinity of OVA to the particles was assessed by mixing of 100 μg/ml AlOOH nanorods with the same amount of OVA in PBS, followed by measuring the amount of OVA that remain in the supernatant (Figure S14). This demonstrated that roughly equal amounts of OVA attached to the particle surface, irrespective of composition. Following i.p. administration and collection of serum 2 weeks later, we found that Rods 1 and 2 showed similar adjuvant effects. Measurement of OVA-specific IgG1 titers demonstrated that Rods 1 and 2 had a significantly higher adjuvant activity compared to Alum (Figure 7A). They also generated significantly higher IgE titers than Alum (Figure 7B). We also found that Rod 5 boosted IgG1 antibody production but not IgE. However, the increase in IgG1 was not significant compared to Alum. Though Rod 5 has comparatively much lower bioactivity in cells (Figures 4A and 6E), its bigger boosting effect in vivo is likely due to OVA binding to the rod surface (Figure S14), thereby serving as a carrier to increase antigen uptake in dendritic cells in vivo. We also performed a second experiment, in which we tested the adjuvant effects of plates and polyhedra, which had little effect on antibody production (Figure S15). In order to confirm the role of oxidative stress in the generation of these Th2-like humoral immune responses, comparative studies were performed in Nrf2−/− mice, which exhibit a blunted phase II antioxidant in response to pro-oxidative particulates.53 This analysis demonstrated an even more robust adjuvant effect for Rod 2 towards OVA-specific IgG1 (>4000 times) and IgE (>4 times) production compared to wild type mice (Figures 7C and 7D). Moreover, NAC administration could suppress IgG1 and IgE responses in Nrf2−/− mice. These data confirm the importance of oxidative stress in AlOOH nanorod-induced adjuvant effects in vivo. To determine whether the AlOOH nanorods induce systemic toxicity, biochemical analysis of the blood serum failed to show any significant changes in biomarkers for liver or kidney toxicity (Table S1).

Figure 7. Adjuvant effect of AlOOH nanorods on humoral immune responses in mice.

Eight week old female wt C57BL/6 or Nrf2−/− C57BL/6 mice (6 animals per group) were treated with endotoxin-free OVA (400 μg) or OVA/AlOOH nanorods (400 μg/2mg) via i.p. on day 0. OVA/Alum immunized mice were used as a control. On day 7, the animals were treated with endotoxin-free OVA (200 μg) via i.p. injection. On day 14, the blood serum was collected to determine (A) IgG1 and (B) IgE titers in wt C57BL/6, (C) IgG1 and (D) IgE in Nrf2−/− C57BL/6 mice. For NAC-treated mice, the mice were treated with 8 mg NAC i.p. every other day for a total of 14 days. *p<0.05 compared to control mice; ap<0.05 compared to OVA-treated mice; #p<0.05 compared to OVA/Alum-treated mice.

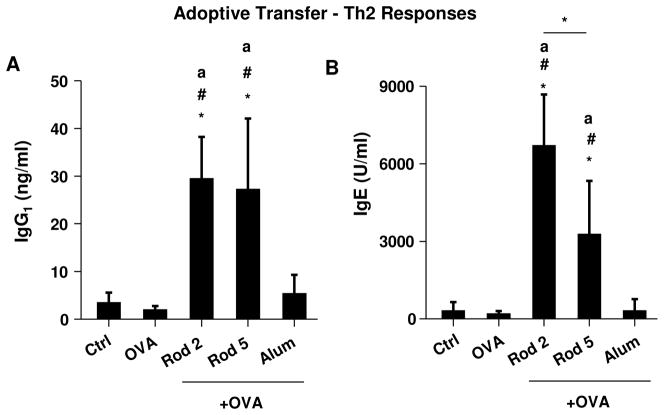

To more directly extrapolate the in vitro to the in vivo outcome of AlOOH nanorods, adoptive transfer of BMDCs was used after ex vivo exposure to 20 μg/ml OVA plus 100 μg/ml AlOOH nanorods or Alum. The BMDCs were i.p. injected in mice on two occasions (day 0 and day 7). Animals were sacrificed on day 14 and serum was obtained to measure antibody levels. As shown in Figure 8A, animals receiving BMDCs primed with Rod 2 plus OVA showed significantly higher anti-OVA IgG1 levels than mice receiving BMDCs primed with OVA alone or OVA plus Alum. Curiously, while Rod 5 induced an effect comparable to Rod 2 for IgG1 production, the effect of Rod 2 was significantly higher than Rod 5 in IgE production (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Humoral immune responses after adoptive transfer of BMDCs.

OVA/AlOOH nanorod-primed BMDCs were i.p. injected into eight week old female C57BL/6 mice (6 animals per group) on day 0. On day 7, the animals were i.p. boosted with OVA/AlOOH nanorod-primed BMDCs. On day 14, the blood serum was collected to determine (A) IgG1 and (B) IgE titers. *p<0.05 compared to control mice; ap<0.05 compared to OVA-primed BMDC sensitized mice; #p<0.05 compared to OVA/Alum-primed BMDC sensitized mice.

DISCUSSION

In this study, a library of AlOOH nanoparticles with defined physicochemical properties was synthesized to determine whether crystal structure, hydroxyl content and particle shape could induce THP-1 and BMDC responses that are predictive of the potential of these materials to exert an adjuvant effect in vivo. We demonstrate that the AlOOH nanorods with the highest hydroxyl content (and the lowest crystallinity) are the most redox active materials, capable of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and stimulating IL-1β production in THP-1 cells and BMDCs. Comparison of the in vitro response profiles to the adjuvant effect in vivo demonstrated that Rods 1 and 2 provided a superior adjuvant effect compared to commercial Alum. Moreover, adoptive transfer was used to show that the BMDC structure-activity relationships relate to their ability to boost the in vivo immune response.

This study establishes an in vitro structure-activity analysis that can be used to quantitatively adjust the adjuvant effect of aluminum-based adjuvants in vivo. By using a comprehensive library of AlOOH nanoparticles with defined shape, crystallinity, and hydroxyl display, we demonstrate that several properties play a role in the adjuvant effect of these materials. One is aspect ratio, which influence cellular uptake and localization in lysosomes. However, this property does not explain the differences between rods, because they all had an aspect ratio of ~10. The second set of properties influencing the adjuvant effect is crystallinity and surface hydroxyl display, which differs from rod to rod and does correlate with the extent of lysosome damage, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production. Although it is possible that other physical properties may play a role, we did not see any clear correlation between IL-β production and the surface area (S), volume (V), or SA/V ratios of the particles (data not shown). We also noticed that AlOOH nanoparticles with higher crystallinity (Rods 1 and 2) formed larger agglomeration and resulted in higher cellular uptake (Figure S7A), suggesting that agglomeration also plays a role in the adjuvant effect. In addition, Rod 5 also induced increased IgG1 production in vivo despite low bioactivity in vitro, suggesting that the binding of OVA and delivery to dendritic cells play a role in boosting the immune response in vivo. Furthermore, the adjuvant effect of AlOOH depends on lysosomal damage and NLRP3 inflammasome assembly. Recruitment of caspase 1 to the inflammasome is responsible for IL-1β production, as evidenced by the suppressed cytokine production in THP-1 cells in which NLRP3 and ASC are deficient (Figure 4B). These SARs are also important in shaping the increased adjuvant effect of Rod 1 and Rod 2 in vivo.

The pro-oxidative effects of aluminum-based materials have not been systematically explored for adjuvant potency. ROS is a critical regulator of different aspects of the immune response.54 Consistent with reports that ROS play an important role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation,55, 56 we demonstrate that AlOOH nanorods induce cellular ROS production and oxidative stress, which contributes to inflammasome assembly as well as in vivo adjuvant effects.57–59 This is further substantiated by the finding that a reduced antioxidant defense (Nrf2 knockout) or treatment with an antioxidant (NAC) could suppress ROS production and IL-1β release in BMDC. Similarly, the boosting of antibody titers in Nrf2−/− mice was 4000 times stronger for IgG1 and 4 times stronger for IgE compared to wild type animals (Figure 7). Moreover, the immunostimulatory effects of the nanorods were blunted by NAC administration (Figures 7C and 7D). These findings are in agreement with previous studies looking at boosting of immune responses to environmental allergens by particulate pollutants. Whitekus et al. demonstrated that the generation of ROS is involved in the adjuvant effects (Th2 response) of diesel exhaust particles (DEP),57 while Li et al. showed that the higher oxidant potential of ultrafine particles (including DEP) make them more effective immune adjuvants than fine (PM 2.5) particulates.58 Moreover, Nrf2 deficiency enhanced the adjuvant effect of UFPs in DCs as a result of compromised antioxidant defense.60

Our study is in agreement with previous findings showing that aluminum-based adjuvants predominantly trigger Th2-like antibody responses (antigen-specific IgG1 and IgE production). It is also known that the adjuvant effects of aluminum-containing adjuvants are preserved in MyD88 and TRIF knockout animals; these are key adapters that impact the induction of Th1 immunity by ligands that engage Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways.61, 62 It is interesting, that in addition to boosting of IL-1β production, AlOOH nanorods could also increase IL-6 and IL-12 production in BMDCs (Figures 6F and 6G). IL-12 plays a key role in promoting the development of Th1 cells from precursors that interact with antigen-presenting DC.46, 63, 64 Future studies will address whether AlOOH nanorods can boost antigen-specific Th1 immune responses, which are key to the development of protective immunity.

Although it is generally agreed that Alum is capable of inducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation at the cellular level, there is some disagreement about the necessity of this pro-inflammatory response pathway in generating adjuvant effects in vivo.24–27, 30 Using NLRP3 knockout mice, Eisenbarth et al. showed that Alum failed to boost OVA-specific antibody responses in NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 knockout mice.24 Similarly, Kool et al. showed that the collection of Alum-induced inflammatory cells in the peritoneal cavity is decreased in NLRP3 deficient mice, supporting the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the induction of adjuvant effects.30 In contrast, Franchi et al. showed that the NLRP3 inflammasome was not required for the induction of an antigen-specific antibody response during immunization with Alum25. Moreover, Kool et al. in another study demonstrated that while NLRP3 deficient mice were partially defective at priming antigen-specific T cells, these animals mounted a normal OVA-specific IgG1 response.26 One possible reason for this discrepancy is the existence of different adjuvant mechanisms by which Alum boost in vivo immune responses, as suggested by studies showing that Alum also induce cytotoxicity and DNA release65, 66 as well as being able to perturb the DC membrane as a way of providing immune stimulation.44 Nonetheless, our study shows excellent correlation between NLRP3 activation at cellular level and the generation of in vivo adjuvant effects (Figures 4 and 7). We propose that this structure-activity relationship will be helpful to design and develop additional aluminum-based adjuvants. Our future studies will address the adjuvant activity of AlOOH nanorods in NLRP3 knockout mice as well as the impact on the alternative pathways. It should be possible to use our rods as reference materials to show whether the paradoxical outcome in NLRP3 knockout mice could be due to the differences in the physicochemical properties of various aluminum-based materials that were used previously. It is possible that differences in the colloidal chemistry during reconstitution of the vaccine could give rise to a number of physicochemical compositions or states of suspension that can engage more than one immunostimulatory pathway.

CONCLUSION

In this paper, we designed and synthesized a library of AlOOH nanoparticles with defined shape, crystallinity and hydroxyl content. Moreover, we demonstrated that these physicochemical properties play a key role in the ability of AlOOH nanorods to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to IL-1β production in dendritic cells and boosting OVA-specific immune responses in mice. Not only are these adjuvants superior to Alum in terms of relative strength, but we also demonstrate that it is possible to boost in vivo immune responses by co-injection with antigen or dendritic cell adoptive transfer. These results demonstrate that the engineered design of aluminum-based adjuvants in combination with structure-activity analysis of the events around NLRP3 inflammasome activation can be used as a design platform to develop improved aluminum-based vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Materials

Alum was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA); Monosodium urate (MSU) crystal was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA); CA-074-Me and Cytochalasin D were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) was purchased from American Regent, INC. (Shirley, NY); endotoxin-free OVA was purchased from BioVendor R&D (Asheville, NC), Magic Red cathepsin B detection kit was purchased from ImmunoChemistry Technologies (Bloomington, MN). The ELISA kits for human IL-1β and pro-IL-1β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); the ELISA kits for mouse IL-1β, IL-12 and IL-6 were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Aluminum (III) nitrate nonahydrate [Al(NO3)3·9H2O], ethylenediamine (EDA), fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I (FITC), (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and aluminum isoproxide [Al(OC3H7)3] were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Synthesis of Aluminum Oxyhydroxide (γ-AlOOH) Nanoparticles

In a typical synthesis of γ-AlOOH nanorods, 1.3933 g of aluminum (III) nitrate nonahydrate [Al(NO3)3·9H2O] was dissolved in 20 ml deionized water to form a clear solution. 0.238 ml of ethylenediamine (EDA) was then added dropwise to the solution during continuous stirring. The pH of the milky precipitate was ~5. After vigorous stirring for 15 min, the reaction mixture was transferred into a 23-ml Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and kept at 140–220 °C in an electric oven for 2–72 h. Once the reaction was completed, the autoclave was immediately cooled in a water bath. The fresh precipitate was separated by centrifugation, washed sequentially with deionized water and ethanol for three cycles to remove all ionic remnants. The final product was dried at 60 °C overnight. Synthesis of γ-AlOOH nanoplates and nanopolyhedra were prepared using the same method except that the pH of the synthesis mixture was adjusted to ~10 by increasing EDA content (0.397 ml). Boehmite nano-polyhedra were prepared following a published procedure, using aluminum isoproxide (Al(OC3H7)3) as aluminum precursor.67

Characterization of γ-AlOOH Nanoparticles

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), using a JEOL 1200 EX (accelerating voltage 80 kV), was used to observe the morphology and to determine the primary size of γ-AlOOH nanoparticles. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD), using a Panalytical X’Pert Pro diffractometer (CuKα radiation), was used to determine the phase and crystallinity of the final γ-AlOOH product. All XRD patterns were collected with a step size of 0.02° and counting time of 0.5 s per step over a 2θ range of 10–80°. Fourier transformed infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded using a Bruker Vertex-70 FTIR spectrometer, using the KBr pellet technique. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed by heating the samples from 20 °C to 1000 °C at a rate of 10 °C/minute under air with a Perkin Elmer Diamond Thermogravimmetric/Differential Thermal Analyzer. High throughput dynamic light scattering (HT-DLS, Dynapro™ Plate Reader, Wyatt Technology) was performed to determine the particle size and size distribution of the γ-AlOOH nanoparticles in water, cell culture medium and PBS supplemented with 0.2% OVA following our recently developed protocol. Zeta potential measurement was conducted using a Brookhaven ZetaPALS instrument.

Abiotic Quantification of Glutathione (GSH) Oxidation by Ellman’s Reagent

Assessment of the GSH content was performed using Ellman’s reagent (5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid), or DTNB. This reagent reacts with GSH to yield yellow colored 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid (TNB), which absorbs at 414 nm. 1.6 mg/ml AlOOH nanoparticles were incubated with 4.5 mM GSH in a volume of 150 μl in a 96-well plate at 37 °C for 30 min. The GSH concentration in the reactant was calculated by constructing a standard curve with known GSH concentrations. GSH oxidation by H2O2 (4 mM) was used as a control.

Abiotic Quantification of ROS generation by the H2DCF Reagent

Assessment of the ROS generation was performed using H2DCF (2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein). H2DCF working solution was prepared by dissolving 50 μg H2DCFDA (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate) in 17.3 μl ethanol. To facilitate cleavage of the diacetate group, 692 μl 0.01 M sodium hydroxide was added to the solution, and the mixture placed at room temperature for 30 min. Then, 3.5 ml sodium phosphate buffer (pH=7.1) was added to neutralize the reaction. The mixture was used as H2DCF working solution. 25 μg/ml AlOOH nanoparticles were incubated with H2DCF working solution in a volume of 100 μl in a 96-well plate at room temperature for 3h. The fluorescence was measured at Ex492/Em527 nm in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Cell Culture

Human THP-1 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml-100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 50 μM beta-mercaptoethanol. NLRP3-deficient (defNLRP3) and ASC-deficient (defASC) THP-1 cells (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) were grown in RPMI-1640 media, supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 200 μg/ml HygroGold, and 100 μg/ml Normocin. BMDCs were prepared from the bone marrow of female C57BL/6 mice, following the protocol described by Williams et al.68 Briefly, bone marrow precursor cells were collected from the femora and tibiae of female C57BL/6 mice and cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 10 μg/ml gentamicin, 250 ng/ml amphotericin B, 50 μM β-ME, 20 mM HEPES and 2 mM L-glutamine. Cells were grown in a volume of 4 ml in a 6-well plate at 5×105 cells/well. On day 0, the cells were maintained with addition of 25 ng/ml GM-CSF. Two days later, the cells were treated with a combination of 20 ng/ml GM-CSF and 10 ng/ml IL-4, and the medium was replaced every other day. On day 8, the immature BMDCs were collected and washed with PBS before use.

Determination of the Cytotoxic Potential of AlOOH Nanoparticles

The cytotoxicity in THP-1 cells and BMDCs was determined by the MTS assay, using CellTiter 96 AQueous (Promega, Madison, WI). After 6 h exposure to AlOOH nanoparticles (500 μg/ml) in a 96-well plate, cell culture medium was removed, and each well was replaced with 120 μl of complete culture medium containing 16.7% MTS stock solution for an hour at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Plates were centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min in an Eppendorf 5430 microcentrifuge with microplate rotor to spin down the cell debris and nanoparticles. 100 μl of the supernatant was removed from each well and transferred into a new 96-well plate. The absorbance of the formazan was read at 490 nm in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Determination of the Endotoxin Level in AlOOH Nanorods

The endotoxin level in AlOOH nanorods was determined using a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay kit (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Briefly, 25 μg AlOOH nanorods were mixed with 50 μl Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) reagent in the wells of a 96-well plate. Then, 50 μl reconstructed LAL was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. 100 μl chromogenic substrate solution was added to each well, and incubated at 37 °C for 6 min. 100 μl 25% aqueous glacial acetic acid solution was added to each well to stop the reaction, and the absorbance was read at 405 nm using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA). A standard curve with known concentrations of endotoxin was used to calculate the concentration of endotoxin level in AlOOH nanorods.

Determination of IL-1β Production by AlOOH Nanoparticles

THP-1 cells in 100 μl tissue culture medium were plated at the density of 3×104 per well in a 96-well plate with the addition of 1 μg/ml phorbol, 12-myristate, 13-acetate (PMA) for 16 h. For BMDCs, cells in 100 μl tissue culture medium were plated at the density of 4×104 per well in a 96-well plate with the addition of 10 ng/ml LPS for 16 h. The medium was replaced with fresh medium and the primed cells treated with AlOOH nanoparticles (500 μg/ml) in the presence of LPS (10 ng/ml) for 6 h. The supernatant of the activated cells was collected to perform the cytokine assay. In another version of the experiment, THP-1 cells were pre-treated with NAC (25 mM), cytochalasin D (5 μM), and CA-074-Me (20 μM) for 30 min before the addition of AlOOH nanoparticles. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacture’s instructions.28

Determination of Intracellular Pro-IL-1β Production by AlOOH Nanoparticles

THP-1 cells in 100 μl tissue culture medium were plated at the density of 3×104 per well in a 96-well plate with the addition of 1 μg/ml phorbol, 12-myristate, 13-acetate (PMA) for 16 h. The medium was replaced with fresh medium and the primed cells treated with AlOOH nanoparticles (500 μg/ml) in the presence of LPS (10 ng/ml) for 6 h. The supernatant of the activated cells were removed and cells were lysed using lysis buffer (100 μl/well). Intracellular pro-IL-1β production by AlOOH nanoparticles was determined using an ELISA, according to the manufacture’s instructions. Briefly, 50 μl assay diluent was added to each well of monoclonal pro-IL-1β antibody pre-coated 96-well plate; then 200 μl diluted samples were added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. After three washes, 100 μl pro-IL-1β antiserum was added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 0.5 h. After three washes, 100 μl pro-IL-1β conjugate was added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 0.5 h. Following three washes, 200 μl substrate solution was added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Finally, 50 μl stop solution was added to each well, and the plate was read at 450 nm in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Determination of Intracellular GSH Content

A GSH-Glo assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to determine the intracellular GSH levels after AlOOH nanoparticle exposure. The THP-1 cells were exposed to AlOOH nanoparticles (250 μg/ml) in a 96-well plate at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for the indicated time. After exposure, the cellular supernatant was removed and 100 μl GSH-Glo reaction buffer containing Luciferin-NT and glutathione S-transferase was added to each well in the plate and incubated at room temperature with constant shaking for 30 min. Then, 100 ul of Luciferin D detection reagent was added to each well and the plate was incubated at room temperature with constant shaking for another 15 min. The luminescent signal was quantified using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA).

Use of TEM to Determine Cellular Uptake

PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells were treated with AlOOH nanoparticles (500 μg/ml) in the presence of LPS (10 ng/ml) for 12 h. The cells were collected and washed with PBS. The cells were treated with 2.5 % glutaraldehyde (in PBS) for 2 h at room temperature. After post-fixation in 1% OsO4 in PBS for 1 h, the cells were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, followed by treatment with propylene oxide, and then embedded in Epon. Approximately 60–70 nm thick sections were sectioned on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome and placed on Formvar-coated copper grids. The sections were stained with uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate and examined on a JEOL 1200EX electron microscope at 80 kV in the Electron Imaging Center for NanoMachines at UCLA.

Quantification of Intracellular Nanoparticle Uptake by Flow Cytometry

Fluorescent labeling of AlOOH nanorods was previously described by us.42 Briefly, AlOOH nanoparticles were labeled with the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) by resuspending 7 mg nanoparticles in 1.5 ml of dimethylformamide (DMF). To this we added 2.5 μl 4% (vol/vol) aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES). The nanoparticle-APTES mixed solution was allowed to interact under nitrogen gas at room temperature for 24 h. The reactant was washed with DMF and resuspended in 0.5 ml DMF. The FITC-DMF solution was prepared by dissolving 2 mg FITC in 1 ml DMF. 88 μl of FITC DMF solution was added into the nanoparticle-DMF mixture, and reacted overnight. The FITC-labeled nanoparticles were washed with purified water several times and suspended in water at 20 mg/ml for future use. THP-1 cells in 2 ml tissue culture medium were plated at the density of 4×105 per well in a 12-well plate in the presence of 1 μg/ml phorbol, 12-myristate, 13-acetate (PMA) for 16 h. The medium was replenished and the differentiated THP-1 cells treated with AlOOH nanoparticles (500 μg/ml) in the presence of LPS (10 ng/ml) for 6 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in PBS for flow cytometry analysis. The cells were analyzed using FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo (Ashland, OR).

Lysosomal Damage and Cathepsin B Release Determined by Confocal Microscopy

Differentiated THP-1 cells were exposed to AlOOH nanoparticles (500 μg/ml) for 5 h in an 8-well chamber at 1×106 cells/400 μl medium for 3 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cells were washed twice with PBS and stained with 420 μl Magic Red (Immunochemistry Technologies, Bloomington, MN) working solution for 1 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cells were washed twice with PBS, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. The cells were then stained with 10 μM Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1 μg/ml WGA-Oregon Green® 488 conjugate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at room temperature for another 20 min. Finally, cells were washed with PBS twice and examined using a Leica Confocal SP2 1P-FCS microscope (Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Facility, UCLA). High-magnification images were obtained with a 63× objective (Leica, N.A.=1.4). Optical sections were averaged 4 times to reduce background noise. Images were processed using Leica Confocal Software.

Assessing Mitochondrial ROS Production by MitoSOX Red

Differentiated THP-1 cells were exposed to AlOOH nanoparticles for 3 h, following which cells were washed twice with PBS and treated with 5 μM MitoSOX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in HBSS for 20 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min. Following two more washes, cells were stained with 10 μM Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 20 min. Cells were washed with PBS twice and examined using a Leica confocal SP2 1P-FCS microscope (Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Facility, UCLA). High-magnification images were obtained with a 63× objective (Leica, N.A.=1.4). Optical sections were averaged 4 times to reduce background noise. Images were processed using Leica Confocal Software. Fluorescence intensity was analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH).

Analysis of BMDC Maturation and Cytokine Production Induced by AlOOH Nanoparticles

BMDCs were exposed to AlOOH nanoparticles at 100 μg/ml for 16 h. The particle effect on BMDC activation was assessed by analyzing the expression of maturation markers (MHC-II, CD86, CD80, and CD40) on the cell surface. The expression of these markers was determined by flow cytometry using the following mAbs: anti-CD11c PE plus one of the following FITC-labeled antibodies: anti-MHC-II, anti-CD86, anti-CD80, or anti-CD40.59 Briefly, cells were exposed to blocking mAbs (CD16/CD32) for 10 min on ice. After washing, cells were incubated with mAbs for 30 min at 4 °C. The cells were analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), and the data analyzed using FlowJo (Ashland, OR). For cytokine production, the BMDCs were treated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 16 h before the addition of AlOOH nanoparticles (500 μg/ml). The cells were treated for 8 h and supernatants were collected for quantification of IL-1β, IL-12 and IL-6 by ELISA. IL-1β, IL-12 and IL-6 were measured by the mouse ELISA sets (BD Biosciences; San Diego, CA) according to the manufacture’s protocols.

Animal Vaccination Using AlOOH Nanoparticles and OVA

Eight week old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Hollister, CA). Nrf2−/− mice were bred in our lab and backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background for 10 generations.69 All animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions that have been set up according to UCLA guidelines for care and treatment of laboratory animals as well as the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Research (DHEW78-23). Our protocols were approved by the Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee at UCLA and include standard operating procedures for animal housing (filter-topped cages; room temperature at 23 ± 2 °C; 60% relative humidity; 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle) and hygiene status (autoclaved food and acidified water). Test animals were treated with endotoxin-free OVA (400 μg) or OVA/AlOOH nanoparticles (400 μg/2mg) via i.p. on day 0. On day 7, the animals were i.p. treated with endotoxin-free OVA (200 μg). For NAC treatment, the mice were i.p. injected with 8 mg NAC every other day for a total of 14 days. After animal sacrifice on day 14, blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture after pentobarbital anesthesia (0.1 ml of 50 mg/kg via i.p.). The mouse chest was opened and the blood was drawn by using a 21G needle and a 1 ml heparin-treated syringe. The serum was separated by centrifugation in a CAPIJECT blood collection tube (Terumo, Somerset, NJ) for 5 min (1500 rpm) and used for IgG1 and IgE measurement by ELISA.57 Briefly, for analysis of OVA-specific IgG1 and IgE, ELISA plate was first coated with 50 μg/ml OVA and exposed to serum samples, and then biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1 or IgE antibody (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was used for detection. During the ELISA experiment, the OVA-coated ELISA plate was also blocked with 10% FBS/PBS to eliminate non-specific binding and background before the addition of serum samples.

Adoptive Transfer of BMDCs

1×106 BMDCs (in 2 ml medium in 6-well plates) were stimulated with endotoxin-free OVA (20 μg/ml) with or without the addition of AlOOH nanoparticles or Alum (100 μg/ml) for 16 h. The stimulated DCs were collected and washed 3 times in cold PBS. On day 0 and day 7, adoptive transfer was performed by i.p. injection of 1×106 cells/mouse in a volume of 200 μl in PBS. On day 14, the mice were sacrificed, and blood was collected. The serum was used for IgG1 and IgE measurement by ELISA.57

Statistical Analysis

For all the figures, the values shown represent mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test for two-group analysis or one-way ANOVA for multiple group comparisons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported by the US Public Health Service Grant U19 ES019528 (UCLA Center for NanoBiology and Predictive Toxicology), but also leveraged support from the National Science Foundation and the Environmental Protection Agency under Cooperative Agreement Number DBI 0830117. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Environmental Protection Agency. This work has not been subjected to EPA review and no official endorsement should be inferred. The authors would thank the CNSI Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Facility at UCLA for confocal fluorescent microscopy, the Janis V. Giorgi Cytometry Core Facility at UCLA for flow cytometry analysis, and the use of TEM instruments at the Electron Imaging Center for NanoMachines supported by NIH (1S10RR23057 to Z.H.Z.) and CNSI at UCLA.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Blood Serum Biochemistry (Table S1), TEM analysis of AlOOH nanoparticles (Figure S1), Characterization of AlOOH nanoplates, AlOOH nanopolyhedra, and Alum (Figure S2), Intracellular pro-IL-1β levels induced by AlOOH nanoparticles in THP-1 cells (Figure S3), Cell viability analysis of AlOOH nanoparticles to THP-1 cells (Figure S4), Endotoxin levels of AlOOH nanorods (Figure S5), Dose-dependent IL-1β production induced by AlOOH nanorods in THP-1 cells (Figure S6), Cellular uptake and subcellular localization of AlOOH nanorods in THP-1 cells (Figure S7), Lysosomal damage and cathepsin B release induced by AlOOH nanorods in THP-1 cells (Figure S8), AlOOH nanorods induce ROS generation in THP-1 cells (Figure S9), Cell viability analysis of AlOOH nanorods to BMDCs (Figure S10), Quantitative measurement of mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cell (BMDC) maturation (Figure S11), Dose-dependent IL-1β production induced by AlOOH nanorods in BMDCs (Figure S12), AlOOH nanorods induce IL-1β production that can be restored by NAC and calcination in BMDCs (Figure S13), OVA binding efficiency to AlOOH nanorods (Figure S14), and Adjuvant effect of AlOOH nanorods, nanoplates, and nanopolyhedra on humoral immune responses in mice (Figure S15). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Translating Innate Immunity into Immunological Memory: Implications for Vaccine Development. Cell. 2006;124:849–863. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogra PL, Faden H, Welliver RC. Vaccination Strategies for Mucosal Immune Responses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:430–445. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.430-445.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Lynfield R, Reingold A, Cieslak PR, Pilishvili T, Jackson D, et al. Decline in Invasive Pneumococcal Disease after the Introduction of Protein-Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1737–1746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta RK, Siber GR. Adjuvants for Human Vaccines-Current Status, Problems and Future Prospects. Vaccine. 1995;13:1263–1276. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00011-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharp FA, Ruane D, Claass B, Creagh E, Harris J, Malyala P, Singh M, O’Hagan DT, Petrilli V, Tschopp J, et al. Uptake of Particulate Vaccine Adjuvants by Dendritic Cells Activates the NALP3 Inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:870–875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804897106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Awate S, Babiuk LA, Mutwiri G. Mechanisms of Action of Adjuvants. Front Immunol. 2013;4:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith DM, Simon JK, Baker JR., Jr Applications of Nanotechnology for Immunology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:592–605. doi: 10.1038/nri3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon JJ, Huang B, Irvine DJ. Engineering Nano- and Microparticles to Tune Immunity. Adv Mater. 2012;24:3724–3746. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Mooney DJ. In Vivo Modulation of Dendritic Cells by Engineered Materials: Towards New Cancer Vaccines. Nano Today. 2011;6:466–477. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wegmann F, Gartlan KH, Harandi AM, Brinckmann SA, Coccia M, Hillson WR, Kok WL, Cole S, Ho LP, Lambe T, et al. Polyethyleneimine Is a Potent Mucosal Adjuvant for Viral Glycoprotein Antigens. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:883–888. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berezhna S, Schaefer S, Heintzmann R, Jahnz M, Boese G, Deniz A, Schwille P. New Effects in Polynucleotide Release from Cationic Lipid Carriers Revealed by Confocal Imaging, Fluorescence Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy and Single Particle Tracking. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2005;1669:193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demento SL, Eisenbarth SC, Foellmer HG, Platt C, Caplan MJ, Saltzman WM, Mellman I, Ledizet M, Fikrig E, Flavell RA, et al. Inflammasome-Cctivating Nanoparticles As Modular Systems for Optimizing Vaccine Efficacy. Vaccine. 2009;27:3013–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvalho LV, Ruiz RdC, Scaramuzzi K, Marengo EB, Matos JR, Tambourgi DV, Fantini MCA, Sant’Anna OA. Immunological Parameters Related To the Adjuvant Effect of the Ordered Mesoporous Silica SBA-15. Vaccine. 2010;28:7829–7836. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercuri LP, Carvalho LV, Lima FA, Quayle C, Fantini MCA, Tanaka GS, Cabrera WH, Furtado MFD, Tambourgi DV, Matos JDR, et al. Ordered Mesoporous Silica SBA-15: A New Effective Adjuvant to Induce Antibody Response. Small. 2006;2:254–256. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensebaa F, Zhou Y, Brolo AG, Irish DE, Deslandes Y, Kruus E, Ellis TH. Raman Characterization of Metal-Alkanethiolates. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectros. 1999;55:1229–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii N, Fukushima J, Kaneko T, Okada E, Tani K, Tanaka SI, Hamajima K, Xin KQ, Kawamoto S, Koff W, et al. Cationic Liposomes Are a Strong Adjuvant For a DNA Vaccine of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:1421–1428. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augst AD, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ. Alginate Hydrogels as Biomaterials. Macromol Biosci. 2006;6:623–633. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200600069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HogenEsch H. Mechanism of Immunopotentiation and Safety of Aluminum Adjuvants. Front Immunol. 2013;3:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baylor NW, Egan W, Richman P. Aluminum Salts in Vaccines - US Perspective. Vaccine. 2002;20:S18–S23. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindblad EB. Aluminium Adjuvants - in Retrospect and Prospect. Vaccine. 2004;22:3658–3668. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glenny AT, Pope CG, Waddington H, Wallace U. The Antigenic Value of Toxoid Precipitated by Potassium Alum. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1926;29:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hem SL, HogenEsch H. Relationship Between Physical and Chemical Properties of Aluminum-Containing Adjuvants and Immunopotentiation. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:685–698. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morefield GL, Sokolovska A, Jiang DP, Hogenesch H, Robinson JP, Hem SL. Role of Aluminum-Containing Adjuvants in Antigen Internalization by Dendritic Cells In Vitro. Vaccine. 2005;23:1588–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O’Connor W, Jr, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. Crucial Role for the Nalp3 Inflammasome in the Immunostimulatory Properties of Aluminium Adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franchi L, Nunez G. The Nlrp3 Inflammasome is Critical for Aluminium Hydroxide-Mediated IL-1 Beta Secretion but Dispensable for Adjuvant Activity. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2085–2089. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kool M, Pétrilli V, De Smedt T, Rolaz A, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, Bergen IM, Castillo R, Lambrecht BN, Tschopp J. Cutting Edge: Alum Adjuvant Stimulates Inflammatory Dendritic Cells through Activation of the NALP3 Inflammasome. J Immunol. 2008;181:3755–3759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKee AS, Munks MW, MacLeod MKL, Fleenor CJ, Van Rooijen N, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Alum Induces Innate Immune Responses through Macrophage and Mast Cell Sensors, But These Sensors Are Not Required for Alum to Act As an Adjuvant for Specific Immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:4403–4414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Xia T, Duch M, Ji Z, Zhang H, Li R, Sun B, Lin S, Meng H, Liao YP, et al. Pluronic F108 Coating Decreases the Lung Fibrosis Potential of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes by Reducing Lysosomal Injury. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3050–3061. doi: 10.1021/nl300895y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji Z, Wang X, Zhang H, Lin S, Meng H, Sun B, George S, Xia T, Nel A, Zink J. Designed Synthesis of CeO2 Nanorods and Nanowires for Studying Toxicological Effects of High Aspect Ratio Nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5366–5380. doi: 10.1021/nn3012114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kool M, Petrilli V, De Smedt T, Rolaz A, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, Bergen IM, Castillo R, Lambrecht BN, Tschopp J. Alum Adjuvant Stimulates Inflammatory Dendritic Cells through Activation of the NALP3 Inflammasome. J Immunol. 2008;181:3755–3759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen XY, Lee SW. PH-Dependent Formation of Boehmite (Gamma-AlOOH) Nanorods and Nanoflakes. Chem Phys Lett. 2007;438:279–284. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou HW, Xie Y, Yang Q, Guo QX, Tan CR. Preparation and Characterization of Gamma-AlOOH Nanotubes and Nanorods. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:741–745. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen SC, Ng WK, Chia LSO, Dong YC, Tan RBH. Morphology Controllable Synthesis of Nanostructured Boehmite and gamma-Alumina by Facile Dry Gel Conversion. Cryst Growth Des. 2012;12:4987–4994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu CL, Lv JG, Xu L, Guo XF, Hou WH, Hu Y, Huang H. Crystalline Nanotubes of Gamma-AlOOH and Gamma-Al2O3: Hydrothermal Synthesis, Formation Mechanism and Catalytic Performance. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:1–9. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/21/215604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Xia T, Ntim SA, Ji Z, George S, Meng H, Zhang H, Castranova V, Mitra S, Nel AE. Quantitative Techniques for Assessing and Controlling the Dispersion and Biological Effects of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes in Mammalian Tissue Culture Cells. ACS Nano. 2010;4:7241–7252. doi: 10.1021/nn102112b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nel AE, Maedler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EMV, Somasundaran P, Klaessig F, Castranova V, Thompson M. Understanding Biophysicochemical Interactions at the Nano-Bio Interface. Nat Mater. 2009;8:543–557. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Dunphy DR, Jiang X, Meng H, Sun B, Tarn D, Xue M, Wang X, Lin S, Ji Z, et al. Processing Pathway Dependence of Amorphous Silica Nanoparticle Toxicity: Colloidal vs Pyrolytic. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15790–15804. doi: 10.1021/ja304907c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun B, Wang X, Ji Z, Li R, Xia T. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Induced by Engineered Nanomaterials. Small. 2013;9:1595–1607. doi: 10.1002/smll.201201962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin C, Frayssinet P, Pelker R, Cwirka D, Hu B, Vignery A, Eisenbarth SC, Flavell RA. NLRP3 Inflammasome Plays a Critical Role in the Pathogenesis of Hydroxyapatite-Associated Arthropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14867–14872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111101108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E. Silica Crystals and Aluminum Salts Activate the NALP3 Inflammasome through Phagosomal Destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. Toxic Potential of Materials at the Nanolevel. Science. 2006;311:622–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1114397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia T, Kovochich M, Liong M, Maedler L, Gilbert B, Shi H, Yeh JI, Zink JI, Nel AE. Comparison of the Mechanism of Toxicity of Zinc Oxide and Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Based on Dissolution and Oxidative Stress Properties. ACS Nano. 2008;2:2121–2134. doi: 10.1021/nn800511k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YT, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of Dendritic Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flach TL, Ng G, Hari A, Desrosiers MD, Zhang P, Ward SM, Seamone ME, Vilaysane A, Mucsi AD, Fong Y, et al. Alum Interaction with Cendritic Cell Membrane Lipids is Essential for Its Adjuvanticity. Nat Med. 2011;17:479–487. doi: 10.1038/nm.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serre K, Mohr E, Toellner KM, Cunningham AF, Granjeaud S, Bird R, MacLennan ICM. Molecular Differences between the Divergent Responses of Ovalbumin-Specific CD4 T Cells to Alum-Precipitated Ovalbumin Compared to Ovalbumin Expressed by Salmonella. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:3558–3566. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Garra A, Murphy KM. From IL-10 to IL-12: How Pathogens and Their Products Stimulate APCs to Induce T(H)1 Development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:929–932. doi: 10.1038/ni0909-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang FX, Kirschning CJ, Mancinelli R, Xu XP, Jin YP, Faure E, Mantovani A, Rothe M, Muzio M, Arditi M. Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Activates Nuclear Factor-kappa B Through Interleukin-1 Signaling Mediators in Cultured Human Dermal Endothelial Cells and Mononuclear Phagocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7611–7614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krummen M, Balkow S, Shen L, Heinz S, Loquai C, Probst HC, Grabbe S. Release of IL-12 by Dendritic Cells Activated by TLR Ligation is Dependent on MyD88 Signaling, Whereas TRIF Signaling is Indispensable for TLR Synergy. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:189–199. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0408228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tada H, Aiba S, Shibata KI, Ohteki T, Takada H. Synergistic Effect of Nod1 and Nod2 Agonists with Toll-Like Receptor Agonists on Human Dendritic Cells to Generate Interleukin-12 and T Helper Type 1 Cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7967–7976. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.7967-7976.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wesa AK, Galy A. IL-1 beta induces dendritic cells to produce IL-12. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1053–1061. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.8.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shay T, Jojic V, Zuk O, Rothamel K, Puyraimond-Zemmour D, Feng T, Wakamatsu E, Benoist C, Koller D, Regev A, et al. Conservation and Divergence in the Transcriptional Programs of the Human and Mouse Immune Systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2946–2951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222738110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mestas J, Hughes CCW. Of Mice and Not Men: Differences between Mouse and Human Immunology. J Immunol. 2004;172:2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li N, Nel AE. Role of the Nrf2-Mediated Signaling Pathway as a Negative Regulator of Inflammation: Implications for the Impact of Particulate Pollutants on Asthma. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2006;8:88–98. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein Links Oxidative Stress to Inflammasome Activation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:136–141. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate Immune Activation through Nalp3 Inflammasome Sensing of Asbestos and Silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A Role for Mitochondria in NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]