Background: H+ transport through membrane-traversing ATP synthase mechanically drives bond formation.

Results: Metal chelation with cysteine residues in cytoplasmic domains near the surface of the membrane blocks proton transport.

Conclusion: Gating from the H+ channel traversing the lipid bilayer occurs in cytoplasmic loops of transmembrane proteins.

Significance: The proton transport pathway traversing ATP synthase extends beyond the lipid bilayer into the cytoplasm.

Keywords: ATP Synthase, F1F0-ATPase, Membrane Energetics, Membrane Transport, Proton Transport, Chemical Modifications Inhibiting Function, Cysteine Substitution Mutagenesis, Loops of Transmembrane Proteins, Subunit c

Abstract

Rotary catalysis in F1F0 ATP synthase is powered by proton translocation through the membrane-embedded F0 sector. Proton binding and release occur in the middle of the membrane at Asp-61 on the second transmembrane helix (TMH) of subunit c, which folds in a hairpin-like structure with two TMHs. Previously, the aqueous accessibility of Cys substitutions in the transmembrane regions of subunit c was probed by testing the inhibitory effects of Ag+ or Cd2+ on function, which revealed extensive aqueous access in the region around Asp-61 and on the half of TMH2 extending to the cytoplasm. In the current study, we surveyed the Ag+ and Cd2+ sensitivity of Cys substitutions in the loop of the helical hairpin and used a variety of assays to categorize the mechanisms by which Ag+ or Cd2+ chelation with the Cys thiolates caused inhibition. We identified two distinct metal-sensitive regions in the cytoplasmic loop where function was inhibited by different mechanisms. Metal binding to Cys substitutions in the N-terminal half of the loop resulted in an uncoupling of F1 from F0 with release of F1 from the membrane. In contrast, substitutions in the C-terminal half of the loop retained membrane-bound F1 after metal treatment. In several of these cases, inhibition was shown to be due to blockage of passive H+ translocation through F0 as assayed with F0 reconstituted into liposomes. The results suggest that the C-terminal domain of the cytoplasmic loop may function in gating H+ translocation to the cytoplasm.

Introduction

F1F0 ATP synthase utilizes the energy stored in an H+ or Na+ electrochemical gradient to synthesize ATP in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts (1–3). The ATP synthase complex is composed of two sectors, i.e. a water-soluble F1 sector that is bound to a membrane-embedded F0 sector. In eubacteria, F1 is composed of five subunits in an α3β3γδϵ ratio and contains three catalytic sites for ATP synthesis and/or hydrolysis centered at the α-β subunit interfaces. F0 is composed of three subunits in an a1b2c10–15 ratio in eubacteria and functions as the ion-conducting pathway (4–8). The c-ring composition in mitochondria varies between species, being eight for bovine and 10 in yeast (9, 10). Ion translocation through F0 drives rotation of a cylindrical ring of c subunits that is coupled to rotation of the γ subunit within the (αβ)3 hexamer of F1 to force conformational changes in the three active sites and in turn drive synthesis of ATP by the binding change mechanism (1–3, 11–14).

Subunit c of F0 folds in the membrane as a hairpin of two extended α-helices connected by a short cytoplasmic loop. In Escherichia coli, 10 copies of subunit c pack together to form a decameric cylindrical ring with TMH12 on the inside and TMH2 on the periphery (5, 15, 16). In the atomic resolution structures of H+-translocating c14-ring from spinach chloroplast (17, 18) and the c15-ring from Spirulina platensis (19), the H+-binding Glu, which corresponds to Asp-61 in E. coli, is located in TMH2 at the middle of the lipid bilayer. Several other neighboring residues form a hydrogen bonding network between TMHs 1 and 2 of one subunit and TMH2 from the adjacent subunit. A more recent structure of the c13-ring from Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4 (20) revealed a more hydrophobic H+ binding site in which a water molecule is coordinated by the H+-binding Glu and the backbone of the adjacent TMH2, an architecture likely shared by the E. coli c-ring. The loop of subunit c, particularly a conserved R(Q/N)P motif, is involved in binding the γ and ϵ subunits of F1 and coupling H+ translocation to ATP synthesis/hydrolysis (21–30).

Subunit a consists of five transmembrane helices, four of which likely interact as a four-helix bundle (31–34). Subunit a lies on the periphery of the c-ring with TMHs 4 and 5 from subunit a and TMH2 from subunit c forming the a-c interface (35, 36). During ion translocation through F0, the essential Arg-210 on TMH4 of subunit a is postulated to facilitate the protonation/deprotonation cycle at Asp-61 of subunit c and cause the rotation of the c-ring past the stationary subunit a (2, 3, 37).

Chemical modification of cysteine-substituted transmembrane proteins has been widely used as a means of probing the aqueous accessible regions (38–40). The reactivity of a substituted cysteine to thiolate-directed probes provides an indication of aqueous accessibility because the reactive thiolate species is preferentially formed in an aqueous environment. The aqueous accessibility of subunits a and c in E. coli F0 has been probed using Ag+, Cd2+, and other thiolate-reactive probes (37, 41–47). The results suggested the presence of an aqueous accessible channel in subunit a in the center of TMHs 2–5 extending from the periplasm to the center of the membrane (34, 36, 37, 44). Protons entering through this periplasmic access channel are postulated to bind to the essential Asp-61 residues of the c-ring with the protonation and deprotonation of Asp-61 driving c-ring rotation. A second putative channel was suggested at the interface of TMH4 of subunit a and TMH2 of subunit c, providing an exit pathway at the a-c interface leading from Asp-61 to the cytoplasm (47).

In previous studies (46, 47), we probed the thiolate reactivity of Cys substitutions in the transmembrane regions of subunit c based upon inhibition of function in response to Ag+ or Cd2+ treatment. Here we report on the reactivity of Cys substitutions in the cytoplasmic loop and at the N- and C-terminal ends of subunit c, completing the screening of nearly all residues in the subunit. The sensitivity of function to inhibition by Ag+ and Cd2+ proved to be widespread in the loop. Inhibition in this region was surprising because metal chelation to the transmembrane Cys thiolates was thought to inhibit function by blocking proton translocation through F0, a function in which the loop was not thought to directly participate. We sought to distinguish between several possible mechanisms of inhibition by Ag+ and Cd2+. Our experiments support the well characterized role of the loop in F1 binding, which proved to be disrupted by Ag+ and Cd2+ in some substitutions, but also suggest involvement of a distinct section of the loop in gating H+ transport to the cytoplasm. In light of this and other data, we hypothesize that the aqueous half-channel from the middle of the membrane to the cytoplasm continues through a cytoplasmic domain at the subunit a-c interface formed by cytoplasmic loops from both subunits.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strain Construction

The mutagenesis procedure of Barik (48) described previously (46, 47) was used to generate the Cys substitutions in subunit c, and all substitutions were expressed in plasmid pCMA113 (41). Fused subunit c dimers containing a single Cys substitution in the C-terminal copy were generated from plasmid pPJC2R, which encodes two c subunits joined by a short linker (49). For purification of wild type and mutant F1F0 complexes, mutant uncE was excised from the pCMA113 derivative plasmid and transferred into pFV2 between the PflMI and BssHII restriction sites (50). Like pCMA113, pFV2 codes a Cys-less F1F0 complex; however, a His tag is present at the N terminus of subunit β rather than subunit a (50). The presence of modifications in either plasmid was confirmed by DNA sequencing through the ligation sites. Mutant plasmids were transferred into the chromosomal unc (atp) operon deletion strain JWP292 (5) for growth and biochemical characterization or DK8 (51) for purification. Growth yields of the mutant strains on glucose minimal medium and succinate minimal medium agar plates were assayed as described previously (41).

ATP-driven ACMA Fluorescence Quenching

Inside-out membrane vesicles were prepared from JWP292 transformant strains, and protein concentrations were determined as described previously (46). Aliquots of membranes (1.6 mg at 10 mg/ml) were suspended in 3.2 ml of HMK-NO3 buffer (10 mm HEPES-KOH, 1 mm Mg(NO3)2, 10 mm KNO3, pH 7.5) or HMK-Cl buffer (10 mm HEPES-KOH, 5 mm MgCl2, 300 mm KCl, pH 7.5) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. ACMA was added to 0.3 μg/ml, and fluorescence quenching was initiated by the addition of 30 μl of 2.5 mm ATP, pH 7. Each experiment was terminated by adding nigericin to 0.5 μg/ml. The fluorescence measured after the addition of nigericin was used as the base line from which the relative quenching of the mutant membranes was calculated. Treatments with Ag+ or Cd2+ were carried out in HMK-NO3 buffer or HMK-Cl buffer, respectively. Inhibition caused by metal treatment was reversed by adding dithiothreitol (DTT) to 2 mm or β-mercaptoethanol (β-MSH) to 4 mm after initiation of quenching with ATP.

Measurement of ATPase Activity

Typically, 10 μg of membrane protein were diluted into 0.9 ml of TM buffer (55.5 mm Tris-SO4, 0.2 mm MgSO4, pH 7.8). The assay was initiated by the addition of 100 μl of 4 mm ATP supplemented with 0.8 μCi/ml [γ-32P]ATP. After incubation for 6 min at 30 °C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 800 μl of 11.25% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid and immediately placed on ice for 10 min. Liberated phosphate was extracted from aqueous solution by adding 0.3 ml of 5 m H2SO4, 0.6 ml of 6% (w/v) ammonium molybdate, and 3 ml of benzene:isobutanol (1:1) followed by Vortex mixing. After phase separation, 0.5 ml of the organic phase was removed for scintillation counting. For treatments with DCCD, HMK-NO3 buffer containing membrane protein at 0.5 mg/ml was supplemented with 50 μm DCCD from a 0.1 m ethanolic stock solution and incubated for 20 min at room temperature prior to additional treatment. For silver and cadmium treatments, membrane protein in HMK-NO3 buffer was incubated with 40 μm AgNO3 or 300 μm CdCl2 for 10 min at room temperature. To measure F1 dissociation, membranes at 0.5 mg/ml in HMK-NO3 buffer were incubated at room temperature for 5 min with or without the inclusion of 40 μm AgNO3 or 300 μm CdCl2. Half of this suspension was centrifuged at 541,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature to pellet the membrane vesicles. Membranes were exposed to metal a total of 15 min prior to the ATPase assay. A 10-μg aliquot from the uncentrifuged suspension and an equivalent volume of supernatant from the centrifuged suspension were transferred to TM buffer and assayed as above.

Purification of F1F0

The His-tagged F1F0 complex was purified as described previously (50, 52). Membrane vesicles from 12 g of plasmid pFV2/strain DK8-transformed cells were suspended at ∼20–25 mg/ml in 10 ml of extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm KCl, 250 mm sucrose, 30 mm imidazole, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm K2-EDTA, 40 mm 6-aminocaproic acid, 15 mm p-aminobenzamidine, 0.2 mm DTT, 0.8% soybean phosphatidylcholine (Sigma, Type IV-S), 1% octyl glucoside, 0.5% cholate, 0.5% deoxycholate, 2.5% glycerol, pH 7.5) and incubated at 4 °C with rocking for 30 min. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 541,000 × g for 30 min. A 1.25-ml nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (His Select, Sigma) was preequilibrated with 5 volumes of extraction buffer, and the supernatant fraction of the extract was loaded at a flow rate of 0.18 ml/min. The column was washed with 10 volumes of extraction buffer. Bound protein was eluted with 5 ml of elution buffer (extraction buffer containing 400 mm imidazole) at a flow rate of 0.27 ml/min. Ten 0.5-ml fractions were flash frozen in a dry ice and ethanol slurry and stored at −80 °C. Fractions were screened for F1F0 components by SDS-PAGE, and protein concentrations were determined using a modified Lowry method (53).

Reconstitution of F1F0 in Liposomes

Liposomes were prepared as described previously (52) with some modifications. Phosphatidylcholine (Sigma, Type IV-S) was suspended at 30 mg/ml in reconstitution buffer (10 mm Tricine-KOH, 2.5 mm MgSO4, 0.1 mm K2-EDTA, 0.5 mm DTT, pH 8.0) by incubation at 50 °C with periodic mixing with a vortexer. Unilamellar liposomes were produced by sonication (with a Heat Systems Ultrasonics 200R sonicator using a 3-mm probe) on ice twice for 30 s at 20-watt power output with a 1-min interval between sonications. Liposomes were mixed with 10% cholate (1% final concentration) and then with purified F1F0 at a protein to lipid ratio of 1:20 and then incubated at 4 °C with rocking for 30 min. This suspension was passed through a centrifuged gel filtration column containing 5 ml of G-25 Sephadex (Sigma) preswollen with reconstitution buffer according to the method of Penefsky (54). At this point, F1F0 liposomes were either used immediately for the preparation of F0 liposomes or frozen in liquid nitrogen for later determination of ATP-driven H+ pumping activity.

Preparation of K+-loaded F0 Liposomes

F1F0 liposomes were dialyzed against 1000 volumes of stripping buffer (0.5 mm Tricine, 0.5 mm K2EDTA, 0.5 mm DTT, pH 8.5) overnight at 4 °C to remove F1. F0 liposomes were diluted with stripping buffer lacking DTT and collected by centrifugation at 195,000 × g for 20 min and resuspended at 60 mg/ml lipid in HMK-SO4 buffer (10 mm HEPES-KOH, 2.5 mm MgSO4, 25 mm K2SO4, pH 7.5). The suspension was frozen in liquid nitrogen, thawed in cold water, and sonicated in a Bransonic bath sonicator twice for 10 s with an intervening 20-s interval. This procedure was repeated once. K+-loaded F0 liposomes were collected by centrifugation at 541,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended at 120 mg/ml lipid in HMK-SO4 buffer. F0 liposomes were stored at 4 °C and were stable for several days.

Electrical Gradient (Δψ)-driven ACMA Fluorescence Quenching

A 5-μl aliquot of K+-loaded F0 liposomes (0.6 mg of lipid) was added to 3.2 ml of stirring HMN-SO4 buffer (10 mm HEPES-NaOH, 2.5 mm MgSO4, 25 mm Na2SO4, pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.3 μg/ml ACMA in a fluorometer cuvette. Quenching of fluorescence was initiated by the addition of valinomycin to 14 ng/ml and terminated by the addition of nigericin to 0.5 μg/ml. For Cd2+ treatment, CdSO4 was added to the indicated concentration after the addition of liposomes and ∼20 s before the initiation of quenching with valinomycin.

RESULTS

Phenotype and Metal Sensitivity of Cys Substitutions

We report the phenotype and metal sensitivity of function for Cys substitutions in the cytoplasmic loop and the N terminus and C terminus of subunit c. This study nearly completes the screening of subunit c with 71 of 79 positions tested for function by in vivo oxidative phosphorylation, ATP-driven H+ pumping activity, and its sensitivity to treatment with Ag+ and Cd2+, and the entirety of this data set is tabulated in Table 1. Most of the new Cys substitution mutants generated in this study grew nearly as well as wild type on both glucose and succinate minimal media (Table 1), indicating a functional oxidative phosphorylation system. Only the R41C substitution abolished growth on succinate, and this substitution was not further characterized. Previous studies determined that Arg-41 is essential for F1 binding and intolerant of even conservative mutations (24, 25). Inverted membrane vesicles from most of the remaining Cys substitution strains were functional in ATP-driven proton pumping as assayed by ACMA fluorescence quenching (Table 1). For mutant F1F0 complexes that were functional in this assay, we tested the effects of 40 μm Ag+ and 300 μm Cd2+ on H+ pumping as described previously (46, 47). Sensitivity values are tabulated in Table 1. Notably, substitutions at most positions in the loop (residues 33–49) were strongly inhibited by Ag+ (Table 1). Only the G33C, K34C, and E37C substitutions at the C-terminal end of TMH1 showed minimal inhibition. Substitutions at positions 35 and 42–49 were also sensitive to inhibition by Cd2+ (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic characterization and metal sensitivity of Cys substitution mutants

| Substitution | Colony size on succinatea | Growth yield on glucoseb | ATP-driven quenchingc | Inhibition of H+ pumpingd |

Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag+ | Cd2+ | |||||

| mm | % | % | % | |||

| TMH1 | ||||||

| L9C | 2.2 | 106 | 74 | 32 | 12 | This study |

| Y10C | 2.2 | 104 | 70 | 49 | 13 | This study |

| M11C | 2.2 | 107 | 76 | 57 | 12 | This study |

| A12C | 1.7 | 101 | 83 | 32 | 7 | This study |

| A13C | 2.2 | 107 | 80 | 19 | 8 | This study |

| A14C | 2.2 | 98 | 82 | 35 | 11 | This study |

| V15C | 2.0 | 104 | 78 | 8 | 8 | 47 |

| M16C | 2.2 | 105 | 76 | 5 | 9 | 47 |

| M17C | 2.0 | 108 | 77 | 1 | 8 | 47 |

| G18C | 0 | 62 | ≤3 | 47 | ||

| L19C | 2.3 | 109 | 76 | 3 | 2 | 47 |

| A20C | 2.0 | 96 | 75 | 97 | 4 | 47 |

| A21C | 2.1 | 99 | 78 | 14 | 4 | 47 |

| I22C | 2.5 | 97 | 76 | 2 | 4 | 47 |

| G23C | 0 | 57 | ≤3 | 47 | ||

| A24C | 2.2 | 98 | 75 | 97 | 13 | 47 |

| A25C | 1.5 | 80 | 46 | 90 | 5 | 47 |

| I26C | 2.1 | 97 | 76 | 3 | 8 | 47 |

| G27C | 0.1 | 56 | ≤3 | 47 | ||

| I28C | 2.3 | 108 | 72 | 97 | 96 | 47 |

| G29C | 0.5 | 59 | ≤3 | 47 | ||

| I30C | 2.0 | 100 | 76 | 0 | 6 | 47 |

| L31C | 2.0 | 99 | 70 | 16 | 14 | 47 |

| G32C | 0.1 | 58 | ≤3 | 47 | ||

| Loop | ||||||

| G33C | 1.9 | 100 | 78 | 36 | 9 | This study |

| K34C | 1.8 | 100 | 79 | 42 | 12 | This study |

| F35C | 1.2 | 63 | 47 | 96 | 79 | This study |

| L36C | 2.2 | 102 | 66 | 94 | 4 | This study |

| E37C | 2.2 | 97 | 48 | 22 | 9 | This study |

| G38C | 2.0 | 98 | 63 | 96 | 15 | This study |

| A39C | 2.0 | 100 | 71 | 91 | 8 | This study |

| A40C | 1.8 | 100 | 57 | 96 | 14 | This study |

| R41C | 0 | 58 | This study | |||

| Q42C | 1.8 | 100 | 81 | 96 | 51 | This study |

| P43C | 1.8 | 96 | 52 | 96 | 64 | This study |

| D44C | 2.0 | 102 | 76 | 97 | 91 | This study |

| L45C | 1.8 | 99 | 73 | 96 | 59 | This study |

| I46C | 1.5 | 101 | 69 | 97 | 86 | This study |

| P47C | 2.0 | 104 | 13e | This study | ||

| L48C | 1.8 | 102 | 42 | 94 | 66 | This study |

| L49C | 2.0 | 100 | 61 | 96 | 87 | This study |

| R50Cf | 2.0 | 75 | ≤3 | This study | ||

| T51C | 2.0 | 100 | ≤3 | This study | ||

| TMH2 | ||||||

| Q52C | 2.1 | 87 | 61 | 97 | 76 | 46 |

| F53C | 2.1 | 91 | 64 | 99 | 21 | 46 |

| F54C | 2.1 | 100 | 6 | 46 | ||

| I55C | 2.1 | 95 | 3 | 46 | ||

| V56C | 2.2 | 108 | 68 | 97 | 24 | 46 |

| M57C | 2.0 | 89 | 71 | 97 | 78 | 46 |

| G58C | 2.1 | 87 | 57 | 99 | 95 | 46 |

| L59C | 2.1 | 90 | 48 | 84 | 90 | 46 |

| V60C | 2.2 | 103 | 65 | 99 | 8 | 46 |

| D61C | 0 | 65 | ≤2 | 46 | ||

| A62C | 1.1 | 98 | 78 | 99 | 35 | 46 |

| I63C | 2.1 | 100 | 74 | 98 | 93 | 46 |

| P64Cg | 2.1 | 95 | 69 | 95 | 44 | 46 |

| M65C | 2.1 | 94 | 66 | 97 | 28 | 46 |

| I66C | 2.4 | 105 | 73 | 91 | 7 | 46 |

| A67C | 2.4 | 100 | 67 | 5 | 6 | 46 |

| V68C | 2.0 | 108 | 82 | 45 | 8 | 46 |

| G69C | 2.0 | 85 | 71 | 62 | 11 | 46 |

| L70C | 2.2 | 103 | 79 | 18 | 9 | 46 |

| G71C | 2.1 | 106 | 77 | 4 | 7 | 46 |

| L72C | 2.0 | 99 | 69 | 50 | 7 | This study |

| Y73C | 2.0 | 79 | ≤3 | This study | ||

| V74C | 2.2 | 101 | 73 | 87 | 4 | This study |

| M75C | 2.0 | 100 | 69 | 91 | 3 | This study |

| F76C | 2.5 | 100 | 29 | This study | ||

| mm | % | % | % | |||

| A77C | 2.0 | 100 | 27 | This study | ||

| V78C | 2.0 | 99 | 78 | 75 | 18 | This study |

| A79C | 2.0 | 100 | 70 | 33 | 16 | This study |

a After 72 h of growth at 37 °C. Average colony size of WT is 2.2 mm.

b Maximum A550 relative to WT on 0.04% glucose. The unc deletion strain grows to 60 ± 5% of WT.

c Average quenching of wild type is 70 ± 5%.

d Extent of reduction in ATP-driven quenching upon metal treatment.

e Function was enhanced after treatment with 2 mm DTT suggesting auto-oxidation of this Cys.

f Substitutions of Arg-50, Thr-51, and Tyr-73 cause a puzzling phenotype in which mutants grow on succinate but are incapable of ATP-driven H+ pumping. The phenotype is consistent with Cys substitutions of Phe-54 and Ile-55 described previously (46) and with the cD61N/M65D double mutation (55), which supports ATP synthesis but not H+ pumping.

g Constructed with an A20P suppressor mutation.

Distinguishing the Mechanisms of Inhibition for the Cytoplasmic Loop Cys Substitutions

Ag+ and Cd2+ react with the thiolate form of Cys, which should predominate in an aqueous versus a lipid-exposed environment. In previous studies of Cys substitutions in transmembrane regions, sensitivity to a metal was thought to be indicative of aqueous exposure, and inhibition was thought to reflect direct obstruction of an aqueous proton translocation pathway (41–44, 46, 47). It is possible that substitution of a hydrophobic residue with Cys could introduce novel aqueous accessibility into subunit c. However, such a Cys residue would not be expected to be sensitive to metal inhibition of ATP-driven H+ pumping unless the Cys side chain packed in a position that was proximal to the native H+ translocation pathway. Cys substitutions outside the membrane should also have access to the bulk aqueous solvent except for those where the side chain is buried in the protein. Ag+ sensitivity is therefore less likely to reflect blockage of an aqueous proton channel unless the channel continues through a protein domain after exiting the lipid bilayer of the membrane. Alternatively, reaction of Cys in the loop region with a metal may disrupt the binding of F1 or the coupling of F1 to F0 and thus prevent ATP-driven quenching while making membranes proton-permeable. Substitutions in this region have been shown previously to reduce the affinity of F1 binding to F0 (22–26), and modification of an ϵH38C mutation at the interface of subunits ϵ and c with N-ethylmaleimide disrupts F1 binding (56). To determine whether sensitive residues in the cytoplasmic loop of subunit c are directly involved in H+ transport and/or gating, we sought to distinguish these possible mechanisms of Ag+ and Cd2+ inhibition.

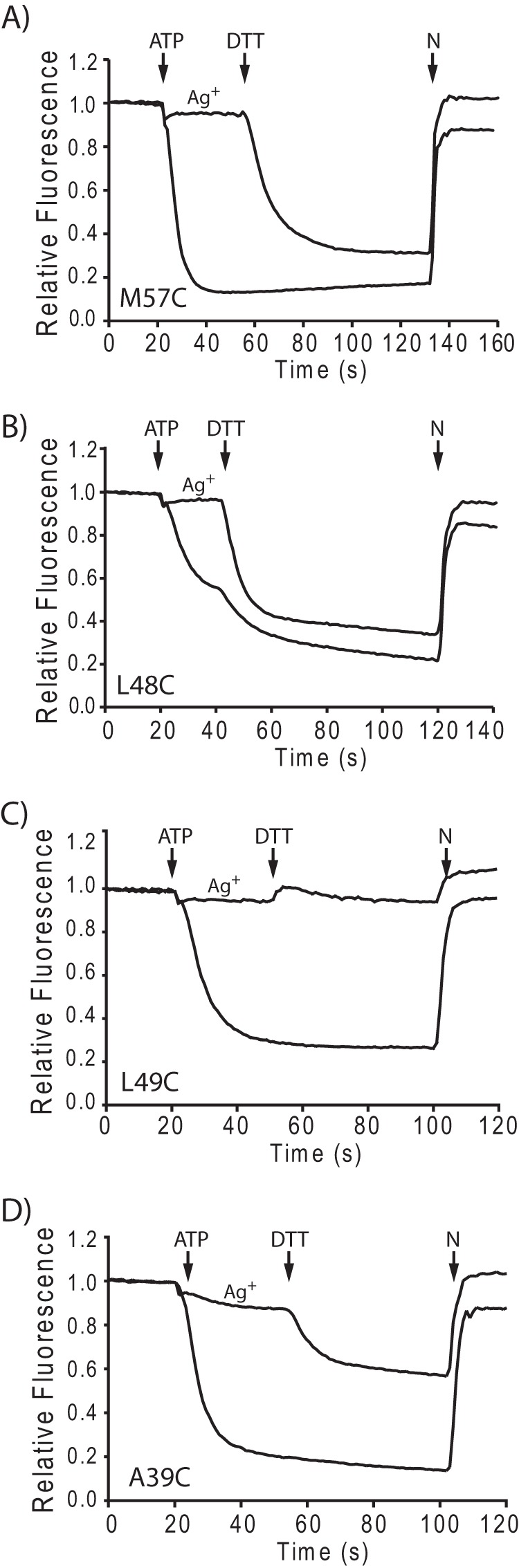

Irreversibility of Metal Inhibition Suggests Disruption of F1 Binding to F0

If metal binding to a substituted Cys disrupts F1 binding to F0, then removal of the bound metal may not restore function. Conversely, if metal binding simply blocks the H+ translocation pathway, then function would more likely be restored upon removal of the blocking metal. Binding of Ag+ or Cd2+ to a substituted Cys should be readily reversed by the addition of a metal-chelating agent such as DTT or β-MSH. The thiolates of the reduced forms of these reagents compete with protein Cys residues for the Ag+ or Cd2+ ions causing the inhibition. Extended incubation with DTT reversed Ag+ inhibition in previous studies of subunit a (41), and both DTT and β-MSH have been used in electrophysiological experiments of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator to rapidly reverse silver modifications of Cys substitutions (57). To determine whether treatment with metals disrupts the integrity of the F1F0 complex, we attempted to rapidly reverse metal inhibition by treatment with DTT or β-MSH during ATP-driven H+ pumping.

Inverted membrane vesicles were treated with 40 μm Ag+ or 300 μm Cd2+ and assayed for ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence. During the quenching assay, DTT or β-MSH was added shortly after the addition of ATP. For most transmembrane Cys substitutions in subunit c, addition of DTT or β-MSH immediately reversed inhibition as represented by quenching of ACMA fluorescence for the M57C substitution (Fig. 1A). Addition of DTT also reversed inhibition at several Cys substitutions in the loop as represented by the L48C substitution (Fig. 1B). The reversal effect is consistent with the removal of a blockage of the H+ translocation pathway and was seen with most transmembrane substitutions as summarized in Table 2. On the other hand, ≤20% reversal of inhibition was observed for substitutions at positions 40, 42, and 49 in the loop region of subunit c (Fig. 1C and Table 2), and only partial reversal was observed for substitutions at positions 25, 35, 36, 38, 39, 43, and 52 (Fig. 1D and Table 2). Persistence of Ag+ inhibition after the addition of DTT suggested that metal treatment caused an irreversible alteration of the Cys-substituted F1F0 complex or a slowly reversible alteration where reversal is beyond the time course of the experiment. The lack of reversal is consistent with disruption of the interactions between F1 to F0 and possible loss of F1 from the membrane.

FIGURE 1.

Reversal of Ag+ inhibition of H+ pumping by DTT. Inverted membrane vesicles were incubated at room temperature for 10 min either with or without 40 μm AgNO3 and then assayed for ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence. In samples treated with Ag+, 2 mm DTT was added at the time indicated. The times of addition of ATP and nigericin (N) are also indicated. A–D show fluorescence traces representing reversible inhibition (A and B), irreversible inhibition (C), and partially reversible inhibition (D).

TABLE 2.

Reversibility of Ag+ inhibition of H+ pumping by DTT

| Substitution | Inhibition by Ag+a | Restoration by DTTb |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| TM1 | ||

| A20C | 97 | 88 |

| A24C | 97 | 78 |

| A25C | 90 | 47 |

| I28C | 97 | 95 |

| Loop | ||

| F35C | 96 | 29 |

| L36C | 94 | 34 |

| G38C | 96 | 24 |

| A39C | 91 | 65 |

| A40C | 96 | 16 |

| Q42C | 96 | 12 |

| P43C | 96 | 70 |

| D44C | 97 | 97 |

| L45C | 96 | 94 |

| I46C | 97 | 100 |

| L48C | 94 | 96 |

| L49C | 96 | 20 |

| TM2 | ||

| Q52C | 97 | 69 |

| F53C | 99 | 90 |

| V56C | 97 | 95 |

| M57C | 97 | 96 |

| G58C | 99 | 90 |

| L59C | 84 | 99 |

| V60C | 99 | 83 |

| A62C | 99 | 88 |

| I63C | 98 | 95 |

| P64Cc | 95 | 75 |

| M65C | 97 | 97 |

| I66C | 91 | 85 |

| V74C | 87 | 94d |

| M75C | 91 | 79d |

a Inhibition of quenching of ACMA fluorescence after the addition of ATP but before the addition of DTT.

b Percentage of quenching response restored by DTT relative to the maximum quenching in the absence of Ag+.

c Constructed with an A20P suppressor mutation.

d 4 mm β-mercaptoethanol used in place of 2 mm DTT.

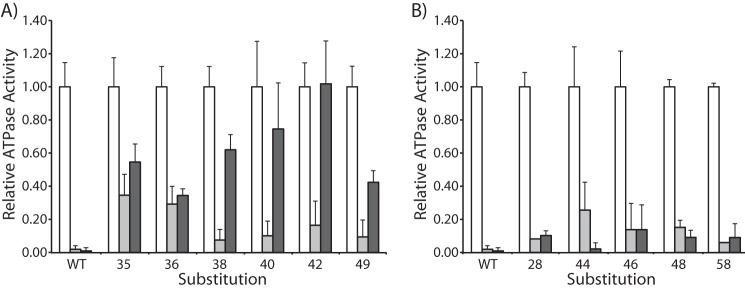

Effect of Ag+ on Dissociation of F1

To investigate the possibility that the irreversible inhibition of proton pumping by metal binding at some positions in the cytoplasmic loop was caused by disruption of F1 binding to F0, we measured the effect of Ag+ treatment on the ATPase activity of the six substitutions in the c loop showing the least reversibility in Ag+-inhibited ATP-driven H+ pumping. Inverted membrane vesicles from each substitution were incubated in HMK-NO3 buffer with 40 μm Ag+, and then half of this suspension was centrifuged to remove the membranes and any bound ATPase. Equivalent volumes of the suspension before centrifugation and the supernatant fraction after centrifugation were assayed for ATPase activity. No significant release of ATPase activity from wild type membranes was observed even after metal treatment (Fig. 2). For the three substitutions where the Ag+ inhibition of proton pumping was essentially irreversible (i.e. A40C, Q42C, and L49C), only a small fraction of ATPase activity was released from membranes without metal treatment. However, Ag+ treatment markedly increased the amount of the ATPase activity in the supernatant for each of these substitutions (Fig. 2A). Similar results were seen for the G38C substitution. For the two substitutions showing more moderate reversibility, F35C and L36C, approximately a third of the ATPase activity measured in the uncentrifuged membrane suspension was present in the supernatant after centrifugation without metal treatment, suggesting that the Cys substitutions themselves cause a degree of disruption of F1 binding to F0 (Fig. 2A). Treatment with Ag+ did not significantly further increase the ATPase activity released from the membranes of these mutants. For substitutions classified as fully reversible (i.e. I28C, D44C, I46C, L48C, and G58C), only a small amount of ATPase activity was released without metal treatment, and treatment with Ag+ did not significantly increase the activity released to the supernatant (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of Ag+ on the release of F1 from the membrane. Inverted membrane vesicles were assayed for ATPase activity. White bars indicate the ATPase activity of untreated, uncentrifuged membranes. The substitutions tested showed inhibition of ACMA quenching by Ag+ that was irreversible (A) or reversible (B) by DTT treatment. Prior to the assay, membranes in HMK-NO3 buffer were incubated at room temperature without metal (light gray bars) or with 40 μm AgNO3 (dark gray bars). After 1 min, half of the membrane suspension was centrifuged to collect the membrane fraction. The light and dark gray bars indicate the ATPase activity measured in the supernatant fraction expressed as a ratio relative to the total ATPase activity of the untreated membrane suspension. Error bars represent the S.D. for each measurement.

Effects of Ag+ and Cd2+ on Total ATPase Activity and Its Sensitivity to DCCD

Disruption of the functional coupling of F1 and F0 during Ag+ or Cd2+ treatment with or without release of F1 from the membrane surface should reduce the sensitivity of ATPase activity to DCCD, an inhibitor that specifically modifies Asp-61 of subunit c and blocks H+ translocation with a consequential inhibition of F1-ATPase activity. To test the effects of metals (both Ag+ and Cd2+) on DCCD sensitivity, which is a measure of the coupling of F1 to F0, inverted membrane vesicles were incubated with or without 50 μm DCCD for 30 min at room temperature, and for the final 10 min of incubation, samples were treated with or without 40 μm Ag+ (or 300 μm Cd2+). The ATPase activity of these membrane suspensions was then assayed. For wild type membranes, Ag+ slightly stimulated activity (Fig. 3). DCCD inhibited wild type ATPase activity by 70 ± 5%, and inhibition was not significantly affected by metal treatment. The ATPase activities of L36C, G38C, A40C, Q42C, and L49C membrane suspensions were greatly stimulated by treatment with Ag+, and metal treatment strikingly reduced the DCCD sensitivity of the reaction, most strikingly for the A40C substitution (Fig. 3A). We observed similar effects after Cd2+ treatment of Q42C and L49C (data not shown). The enhancement of ATPase activity can be attributed to the release of F1-ATPase from the membrane (as shown in Fig. 2) with removal of the drag resistance by the F0 rotary motor on the F1 rotary motor. The loss of DCCD sensitivity on metal treatment of the L36C, G38C, A40C, Q42C, and L49C substitutions supports the conclusion that F1 is uncoupled from F0. In contrast, the ATPase activity of Cys substitutions thought to be involved in H+ translocation (i.e. mutants where metal inhibition was reversed by DTT) was inhibited by Ag+ in a manner similar to the inhibition observed after treatment with DCCD (Fig. 3B). In the case of transmembrane residues I28C and G58C and loop residue L48C, DCCD inhibition of ATPase activity was not reversed by Ag+ (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of Ag+ on total ATPase activity and its sensitivity to DCCD. Inverted membrane vesicles were assayed for ATPase activity. The substitutions tested showed inhibition of ACMA quenching by Ag+ that was irreversible (A) or reversible (B) following treatment with DTT. Prior to the assay, membranes were incubated for 20 min at room temperature in HMK-NO3 buffer with no additions (solid bars) or 50 μm DCCD (hatched bars). These incubations were followed by treatment with no metal (white bars) or 40 μm AgNO3 (gray bars). Activity is expressed as a ratio relative to the activity of untreated membranes. Error bars represent the S.D. for each measurement.

Effect of Cd2+ on H+ Transport through F0

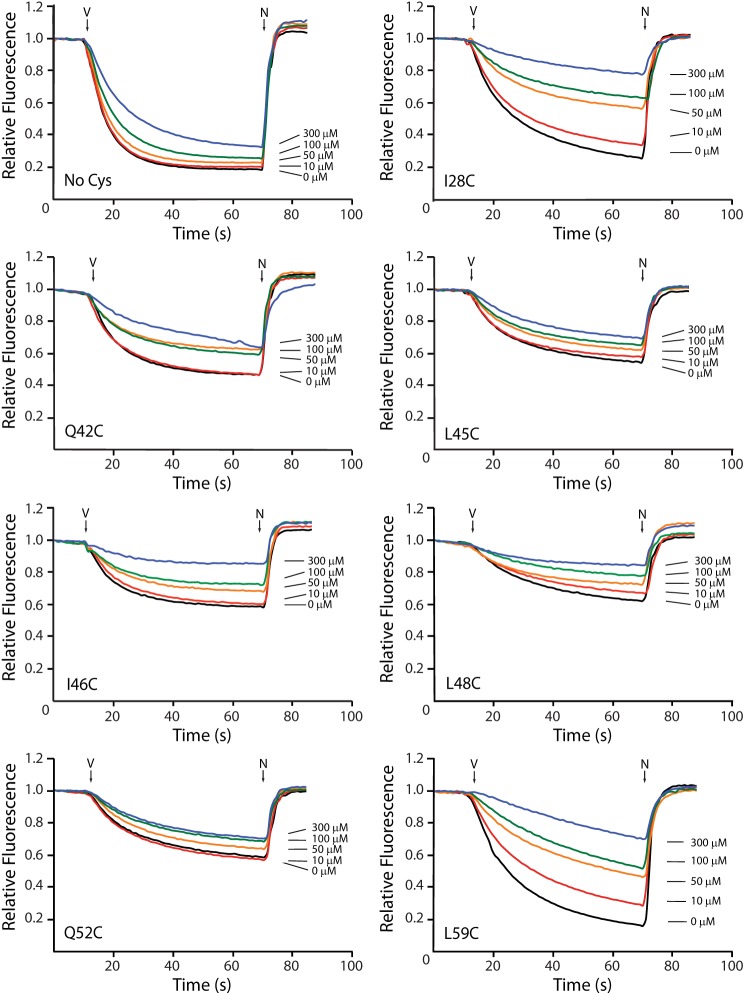

To support the hypothesis that Ag+ and Cd2+ block H+ translocation in the Cys substitutions where inhibition was reversed by DTT, we directly measured the effects of metal treatment on H+ transport by Cys-substituted F0. We reconstituted wild type and mutant F0 into liposomes and measured the quenching of ACMA fluorescence driven by a Δψ. As described under “Experimental Procedures,” His-tagged F1F0 was purified by detergent extraction and affinity chromatography and then reconstituted into unilamellar phosphatidylcholine liposomes. F1 was removed under conditions of high pH and low ionic strength, and the resultant F0 liposomes were loaded with K+. To measure H+ influx through F0, we diluted K+-loaded F0 liposomes into a K+-free buffer containing ACMA and added valinomycin to generate a Δψ in response to the K+ diffusion potential, which then drove H+ import into the liposomes through F0. Ag+ interfered with the valinomycin-driven quenching assay likely because of its affinity for valinomycin (58), so we only examined Cd2+-sensitive mutants here. Wild type F0 and several mutant F0 complexes containing Cys substitutions in subunit c were purified and functionally reconstituted; however, complexes containing mutations F35C, D44C, L49C, M57C, G58C, and I63C were not successfully reconstituted. To determine whether Cd2+ when bound to a substituted Cys blocks H+ permeability, we supplemented the Δψ-driven quenching assay with various concentrations of CdSO4. Wild type F0 was minimally sensitive with <15% inhibition being seen at 300 μm Cd2+ (Fig. 4). Cd2+ markedly reduced the quenching response of F0 liposomes with I28C or L59C transmembrane substitutions and markedly inhibited the quenching response of the I46C and L48C loop substitutions (Fig. 4). The Cd2+ inhibition of this quenching response, which directly measures passive H+ translocation through F0, strongly suggests that Cd2+ also inhibits ATP-driven H+ pumping in these four mutants by directly blocking H+ transport through F0. Relative to that seen in wild type, Cd2+ treatment resulted in somewhat greater inhibition of the quenching response with Q42C, L45C, or Q52C F0 liposomes (Fig. 4), which suggested that the structural changes causing uncoupling upon metal treatment may also result in minor effects on H+ movement through the loop region at the surface of F0. The relatively minor inhibition observed for these substitutions is consistent with the conclusion that uncoupling is the primary mechanism of metal inhibition at these positions.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of Cd2+ on the H+ permeability of reconstituted F0. The H+ permeability of K+-loaded F0 liposomes was assayed by Δψ-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After base-line fluorescence was established with 0.6 mg of F0 liposomes, quenching was initiated by the addition of valinomycin (arrow V). CdSO4 was included at the indicated concentration. Quenching was stopped by the addition of nigericin (arrow N).

Flexibility of the Cytoplasmic Loop

The length of the cytoplasmic loop of subunit c (i.e. the number of residues between the conserved GXGXGXG motif in TMH1 and the Asp-61 or equivalent residue in TMH2 is invariant among the c subunits of eubacteria and eukaryotes (Fig. 5A)) and an NMR study of the loop from E. coli subunit c suggested that it forms a rigid structure (59). We tested the structural flexibility of the region of the cytoplasmic loop implicated in H+ translocation by inserting or deleting 1–3 residues near Ile-46 (Fig. 5B). This region of the loop was chosen for alteration due to its low sequence conservation. Residues were genetically inserted or deleted by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” We then assayed the insertion or deletion mutants for ATP-driven H+ pumping to determine whether the alterations disrupted activity. To our surprise, inverted membrane vesicles from mutants in which Ile-46 was deleted or Ala was inserted after Leu-45 were functional in ATP-driven proton pumping as assayed by ACMA fluorescence quenching (Fig. 5C). Mutants in which Ile-46 and Leu-48 were both deleted or Ala-Gly-Ala was inserted after Leu-45 were not functional in this assay (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Function of mutants with an altered subunit c loop. A, alignment of subunit c sequences from various bacterial and eukaryotic species indicates a distance of 31 residues between the helix packing motif (GXGXGXG) and the proton binding motif (D/E). B, a portion of the amino acid sequence of E. coli subunit c is shown with conserved motifs marked in bold. Deletions (del) or insertions (ins) of amino acids (marked in gray italics) were made in the subunit c loop downstream of the conserved RQP motif. C, inverted membrane vesicles containing F1F0 with an altered subunit c loop were assayed for ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence in HMK-Cl buffer. Fluorescence traces are labeled to correspond to the alterations described in A. N, nigericin.

Metal-mediated Cross-linking at Some Cys Positions

A third effect of Ag+ may contribute to inhibition at several positions. Ag+ is multicoordinate and has been shown to simultaneously bind multiple thiolates (60). A Cys substituted into subunit c would be present in every subunit making up the decameric ring so that any substituted Cys would be in close proximity to the Cys in subunits on either side. Single Cys substitutions at the C-terminal end of cTMH2 have been shown to form dimers in the presence of Cu2+-phenanthroline (15), and other cross-linking experiments indicate that cTMH2 is capable of significant mobility (61). To test the possibility that inhibition of H+ pumping could be caused by metal-mediated cross-linking, we have created genetically fused subunit c dimers that contain a single substituted Cys in only one copy of the two fused subunits. A c-ring assembled from these dimers would not position Cys in adjacent subunits, so formation of a metal-mediated cross-link would be unlikely. Inverted membrane vesicles isolated from these fusion mutants are competent in ATP-driven proton pumping as assayed by quenching of ACMA fluorescence (Table 3). When assayed for Ag+ sensitivity, most dimer substitutions retained the sensitivity observed in the Cys-substituted c monomer, suggesting that cross-linking is not the source of inhibition for these sensitive substitutions. Marked reductions in Ag+ sensitivity occurred for several substitutions on the periplasmic half of subunit c, including c′A20C, c′V60C, c′M75C, and c′V78C where the c′ substitution is placed in only the C-terminal subunit of the c-c′ dimer. A reduction in sensitivity to Ag+ resulting from increased spacing between Cys suggests that metal-mediated cross-linking may contribute significantly to inhibition at these positions. This conclusion for c′M75C and c′V78C is supported by Cu2+-mediated cross-linking of these residues, suggesting increased flexibility in the C terminus (15). On the other hand, a more likely explanation for the c(wild type)-c′A20C and c(wild type)-c′V60C dimers may be a reduced disruption of structure in rigidly packed regions of the c-ring, especially for the V60C substitution, which lies on the buried side of TMH2 proximal to TMH1.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity of fused c dimers to Ag+

| Substitution | ATP-driven quenching by c2 | Inhibition by Ag+ |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| cCys | c2WT/Cys | ||

| % | % | ||

| A12C | 69 | 32 | 29 |

| A20C | 73 | 97a | 44 |

| A24C | 59 | 97a | 95 |

| I28C | 42 | 97a | 94 |

| L36C | 78 | 94 | 70 |

| A40C | 47 | 96 | 90 |

| L48C | 43 | 94 | 95 |

| L49C | 72 | 96 | 95 |

| Q52C | 18 | 95b | 81 |

| F53C | 71 | 95b | 97 |

| V56C | 55 | 96b | 90 |

| G58C | 39 | 97b | 95 |

| V60C | 72 | 97b | 25 |

| I63C | 51 | 96b | 94 |

| M75C | 74 | 91 | 29 |

| V78C | 65 | 75 | 42 |

DISCUSSION

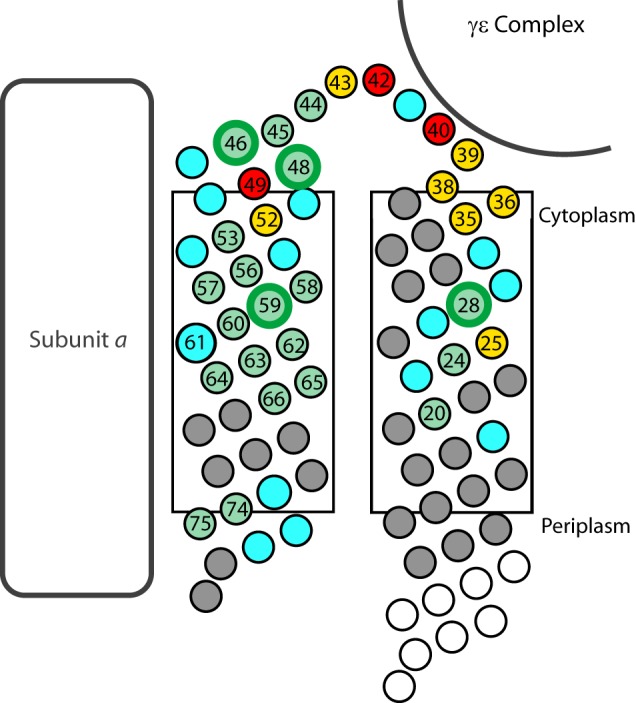

Previous studies demonstrated that Ag+ and Cd2+ ions and presumably H2O can access Cys substitutions in the transmembrane regions of subunit c and defined an aqueous pathway by which protons can travel from the proton-binding Asp-61 in the middle of the membrane to the cytoplasmic surface (46, 47). In the current study, we surveyed the Ag+ and Cd2+ sensitivity of Cys substitutions in the polar loop and at the N- and C-terminal ends of subunit c and identified several Ag+-sensitive regions lying outside of the membrane bilayer with distinctly different properties. Two distinct regions were identified in the cytoplasmic loop. In the first region including residues between positions 35 and 43 on the N-terminal side and 49 and 52 on the C-terminal side of the loop (Fig. 6), substitutions became uncoupled upon treatment with Ag+ or Cd2+, suggesting that metal treatment of Cys substitutions in this region disrupts F1 binding to the c-ring. In a second region of the loop including residues 44–48 (Fig. 6), metals inhibited ATP-coupled H+ transport without uncoupling F1 from F0, and Cd2+ was shown to block passive F0-mediated H+ transport, suggesting that this was the mechanism of inhibition. Finally, in the C-terminal region at positions 74–78, inhibition appeared to be the result of Ag+-mediated cross-linking between Cys in adjacent c subunits in the ring. This hypothesis is plausible given that Ag+ is bicoordinate (60) and that Cys substitutions at positions 74, 75, and 78 form high yield dimers in the presence of Cu2+-phenanthroline, suggesting structural flexibility in this region (15).

FIGURE 6.

Two distinct regions of metal sensitivity in the polar loop of subunit c. Residues in subunit c are shown as circles. Cys substitutions of the numbered residues were Ag+-sensitive in this and previous studies (46, 47). Circles are colored to represent the reversibility of Ag+ inhibition upon treatment with DTT: green indicates essentially full reversibility (≥70%), yellow indicates partial reversibility (>20–70%), and red indicates little or no reversibility (≤20%). Enlarged green circles indicate residues where Cd2+ blocked passive H+ translocation. Gray circles represent residues that were not sensitive to Ag+. Positions where a Cys substitution abolishes function are colored cyan. Positions colored white were not tested. The approximate proximity of other F1F0 subunit domains is indicated.

Most of the metal-inhibited Cys substitutions in the loop, including positions 35, 36, 38–43, 49, and 52, show defects in the binding or coupling of F1 to F0 as initially evidenced by the irreversibility of inhibitory effects of Ag+ by subsequent addition of DTT. At the positions studied in greater detail, metal treatment resulted in increased F1 release from the membrane with a resultant increase in ATPase activity, reduced DCCD sensitivity, and Ag+ inhibition of H+ pumping that was unaffected or only partially reversed by treatment with DTT (Figs. 2 and 3). These effects are consistent with previous mutagenesis results supporting the role of this region in F1 binding. Arg-41, Gln-42, and Pro-43 form a conserved motif, and in general, mutations in this region are characterized by reduced binding affinity of the c-ring with F1, increased dissociation of F1, reduced DCCD sensitivity, and a defect in ATP-driven H+ pumping, all of which are indicators of defective coupling of F1 and F0 (21–27). The deleterious effect of a Q42E mutation in this motif can be suppressed by a second, compensating mutation at Glu-31 in subunit ϵ (26). Furthermore, disulfide cross-linking experiments indicate that Cys at positions 40, 42, 43, and 44 can be cross-linked to subunits γ and ϵ in F1 (28, 29, 56).

A recent structure of the F1c complex from yeast mitochondria revealed the c-γϵ interface at high resolution and supports the electrostatic interaction of this region of the loop with the F1 stalk (62). Ag+ or Cd2+ modification of a Cys at this position might easily alter the chemical environment required for F1 binding. Despite its role as a binding site for the γ and ϵ subunits of F1, the loop is remarkably tolerant of substitution, even at the latter two positions in the highly conserved RQP motif. This tolerance is consistent with the results of a random mutagenesis study where mutants with substitutions at every position in the loop except for Arg-41 still supported growth on succinate (63). In a striking example of loop plasticity, we observed that ATP-driven H+ pumping activity is not significantly affected by the insertion of an Ala after Leu-45 or the deletion of Ile-46 even though the length of the loop is invariant across bacterial and eukaryotic c subunits (Fig. 5A).

We have also identified a region of the loop in which binding of metals to Cys block ATP-coupled H+ transport in a manner that was totally reversed by DTT as was the case for most transmembrane substitutions. This region includes positions 44–48 and is continuous with the aqueous accessible cytoplasmic end of TMH2. Two of the loop substitutions also show passive F0-mediated proton transport activity that was inhibited by Cd2+ in a manner akin to the inhibition seen with representative transmembrane substitutions where metals are thought to inhibit function by directly blocking proton transport through F0. These two Cys substitutions, i.e. I46C and L48C, show no indication of dissociation of F1 from F0 on treatment with Ag+ or Cd2+. Two other Cys substitutions in this region, D44C and L45C, also show complete reversal of inhibition by DTT and no evidence of uncoupling F1 from F0. In addition, metal treatment was shown to inhibit ATPase activity for several representative substitutions both in this region of the loop and in TMH substitutions in contrast to the metal-dependent stimulation of ATPase activity in mutants that became uncoupled (Figs. 2 and 3). Although the effects of Ag+ on the H+ permeability of F0 could not be tested, the common chemistry shared by Ag+ and Cd2+ in sulfur chelation as well as the identical effects caused by both metals for many substitutions in the other assays reported here (i.e. inhibition of ATP-driven H+ pumping, reversibility of inhibition by DTT, and inhibition of ATPase activity) suggests that Ag+ also blocks H+ translocation in these regions (64). These results support our previous interpretations (41–44, 46, 47) that the sensitivity of substitutions in transmembrane regions to Ag+ and Cd2+ is due to blockage of the H+ translocation pathway and that accessibility to the metals is provided by an aqueous channel that functions in F0-mediated H+ transport.

The occurrence of metal sensitivity in the residue 44–48 region of the loop that is likely to be caused by steric or electrostatic blockage of H+ transport suggests that the H+ translocation pathway does not end at the surface of the lipid bilayer but rather continues through a protein domain into the cytoplasm. Although the structure of the E. coli c-ring has not been determined, several crystal structures of H+-translocating c-rings indicate that residues 46 and 48 lie on the end of TMH2 and project toward each other at the interface of two c subunits (17, 19, 20, 62, 65). Furthermore, residue 44 projects into the cytoplasm from the loop. The arrangement of the side chains of residues 46 and 48 suggests that the H+ translocation pathway may run at the interface of two c subunits packing against subunit a in this region. Recently, Moore et al. (45) reported on the Ag+ sensitivity of two Cys substitutions in the 1-2 loop and substitutions in the 194–199 region of the 3-4 loop of subunit a. Cross-linking experiments showed that the residues in the 1-2 loop, including M93C, lie in close proximity to the highly Ag+-sensitive L195C substitution. The authors concluded that these Ag+-sensitive regions pack into a single cytoplasmic domain that is somehow involved in the H+ translocation pathway, perhaps as part of a gating mechanism. Residues 194–199 in the 3-4 loop lie at the cytoplasmic end of TMH4 just outside of the membrane, and earlier cross-linking studies (35) indicate that an extensive face of the cytoplasmic side of aTMH4 packs against cTMH2 in the membrane. These observations suggest that the Ag+-sensitive residues in the 3-4 loop of subunit a lie in close proximity to the portion of the cytoplasmic loop of subunit c proposed in this study to be involved in H+ translocation. Given the expected proximity of aM93C to the region of the subunit c loop implicated here in H+ translocation, interaction between each of these Ag+-sensitive domains is a reasonable expectation. The exit channel at the aTMH4 and cTMH2 interface from the middle of the membrane to the cytoplasm may then be gated by interacting cytoplasmic domains of the polar loop of subunit c and the cytoplasmic loops of subunit a.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rachael Patterson, Hun Sun Chung, and Andrew Larkin for assistance with some of these experiments. Professor Wayne Frasch of Arizona State University generously provided the pFV2 plasmid. We also thank Drs. Robert Nakamoto and Christoph von Ballmoos for helpful suggestions on the preparation of F0 liposomes.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM23105 from the United States Public Health Service.

- TMH

- transmembrane helix

- ACMA

- 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine

- β-MSH

- β-mercaptoethanol

- DCCD

- dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yoshida M., Muneyuki E., Hisabori T. (2001) ATP synthase—a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakamoto R. K., Baylis Scanlon J. A., Al-Shawi M. K. (2008) The rotary mechanism of the ATP synthase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 476, 43–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. von Ballmoos C., Wiedenmann A., Dimroth P. (2009) Essentials for ATP synthesis by F1F0 ATP synthases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 649–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Foster D. L., Fillingame R. H. (1982) Stoichiometry of subunits in the H+-ATPase complex of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 2009–2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jiang W., Hermolin J., Fillingame R. H. (2001) The preferred stoichiometry of c subunits in the rotary motor sector of Escherichia coli ATP synthase is 10. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4966–4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitome N., Suzuki T., Hayashi S., Yoshida M. (2004) Thermophilic ATP synthase has a decamer c-ring: indication of noninteger 10:3 H+/ATP ratio and permissive elastic coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12159–12164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meier T., Polzer P., Diederichs K., Welte W., Dimroth P. (2005) Structure of the rotor ring of F-type Na+-ATPase from Ilyobacter tartaricus. Science 308, 659–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pogoryelov D., Yu J., Meier T., Vonck J., Dimroth P., Muller D. J. (2005) The c15 ring of the Spirulina platensis F-ATP synthase: F1/F0 symmetry mismatch is not obligatory. EMBO Rep. 6, 1040–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watt I. N., Montgomery M. G., Runswick M. J., Leslie A. G., Walker J. E. (2010) Bioenergetic cost of making an adenosine triphosphate molecule in animal mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16823–16827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stock D., Leslie A. G., Walker J. E. (1999) Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science 286, 1700–1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boyer P. (1989) A perspective of the binding change mechanism for ATP synthesis. FASEB J. 3, 2164–2178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abrahams J. P., Leslie A. G., Lutter R., Walker J. E. (1994) Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature 370, 621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Noji H., Yasuda R., Yoshida M., Kinosita K. (1997) Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature 386, 299–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weber J., Senior A. E. (2003) ATP synthesis driven by proton transport in F1F0-ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 545, 61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones P. C., Jiang W., Fillingame R. H. (1998) Arrangement of the multicopy H+-translocating subunit c in the membrane sector of the Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 17178–17185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dmitriev O. Y., Jones P. C., Fillingame R. H. (1999) Structure of the subunit c oligomer in the F1Fo ATP synthase: model derived from solution structure of the monomer and cross-linking in the native enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7785–7790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vollmar M., Schlieper D., Winn M., Büchner C., Groth G. (2009) Structure of the c14 rotor ring of the proton translocating chloroplast ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18228–18235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krah A., Pogoryelov D., Langer J. D., Bond P. J., Meier T., Faraldo-Gómez J. D. (2010) Structural and energetic basis for H+ versus Na+ binding selectivity in ATP synthase Fo rotors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 763–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pogoryelov D., Yildiz O., Faraldo-Gómez J. D., Meier T. (2009) High-resolution structure of the rotor ring of a proton-dependent ATP synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1068–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Preiss L., Yildiz O., Hicks D. B., Krulwich T. A., Meier T. (2010) A new type of proton coordination in an F1F0-ATP synthase rotor ring. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mosher M. E., White L. K., Hermolin J., Fillingame R. H. (1985) H+-ATPase of Escherichia coli. An uncE mutation impairing coupling between F1 and F0 but not F0-mediated H+ translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 4807–4814 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller M. J., Fraga D., Paule C. R., Fillingame R. H. (1989) Mutations in the conserved proline 43 residue of the uncE protein (subunit c) of Escherichia coli F1F0-ATPase alter the coupling of F1 to F0. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 305–311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fraga D., Fillingame R. H. (1989) Conserved polar loop region of Escherichia coli subunit c of the F1F0 H+-ATPase. Glutamine 42 is not absolutely essential, but substitutions alter binding and coupling of F1 to F0. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 6797–6803 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hatch L., Fimmel A. L., Gibson F. (1993) The role of arginine in the conserved polar loop of the c-subunit of the Escherichia coli H+-ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1141, 183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fraga D., Hermolin J., Oldenburg M., Miller M. J., Fillingame R. H. (1994) Arginine 41 of subunit c of the Escherichia coli H+-ATP synthase is essential in binding and coupling of F1 to F0. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 7532–7537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y., Oldenburg M., Fillingame R. H. (1994) Suppressor mutations in F1 subunit ϵ recouple ATP-driven H+ translocation in uncoupled Q42E subunit c mutant of Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 10221–10224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Y., Fillingame R. H. (1995) Subunits coupling H+ transport and ATP synthesis in the Escherichia coli ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 24609–24614 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Watts S. D., Zhang Y., Fillingame R. H., Capaldi R. A. (1995) The γ subunit in the Escherichia coli ATP synthase complex (ECF1F0) extends through the stalk and contacts the c subunits of the F0 part. FEBS Lett. 368, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hermolin J., Dmitriev O. Y., Zhang Y., Fillingame R. H. (1999) Defining the domain of binding of F1 subunit ϵ with the polar loop of F0 subunit c in the Escherichia coli ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17011–17016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pogoryelov D., Nikolaev Y., Schlattner U., Pervushin K., Dimroth P., Meier T. (2008) Probing the rotor subunit interface of the ATP synthase from Ilyobacter tartaricus. FEBS J. 275, 4850–4862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Valiyaveetil F. I., Fillingame R. H. (1998) Transmembrane topography of subunit a in the Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16241–16247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Long J. C., Wang S., Vik S. B. (1998) Membrane topology of subunit a of the F1F0 ATP synthase as determined by labeling of unique cysteine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16235–16240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wada T., Long J. C., Zhang D., Vik S. B. (1999) A novel labeling approach supports the five-transmembrane model of subunit a of the Escherichia coli ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17353–17357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwem B. E., Fillingame R. H. (2006) Cross-linking between helices within subunit a of Escherichia coli ATP synthase defines the transmembrane packing of a four-helix bundle. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37861–37867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang W., Fillingame R. H. (1998) Interacting helical faces of subunits a and c in the F1F0 ATP synthase of Eschericia coli defined by disulfide cross-linking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6607–6612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moore K. J., Fillingame R. H. (2008) Structural interactions between transmembrane helices 4 and 5 of subunit a and the subunit c ring of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31726–31735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fillingame R. H., Angevine C. M., Dmitriev O. Y. (2003) Mechanics of coupling proton movements to c-ring rotation in ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 555, 29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karlin A., Akabas M. H. (1998) Substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Methods Enzymol. 293, 123–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaback H. R., Dunten R., Frillingos S., Venkatesan P., Kwaw I., Zhang W., Ermolova N. (2007) Site-directed alkylation and the alternating access model for LacY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 491–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lü Q., Miller C. (1995) Silver as a probe of pore-forming residues in a potassium channel. Science 268, 304–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Angevine C. M., Fillingame R. H. (2003) Aqueous access channels in subunit a of rotary ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6066–6074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Angevine C. M., Herold K. A., Fillingame R. H. (2003) Aqueous access pathways in subunit a of rotary ATP synthase extend to both sides of the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13179–13183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Angevine C. M., Herold K. A., Vincent O. D., Fillingame R. H. (2007) Aqueous access pathways in ATP synthase subunit a. Reactivity of cysteine substituted into transmembrane helices 1, 3, and 5. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9001–9007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dong H., Fillingame R. H. (2010) Chemical reactivities of cysteine substitutions in subunit a of ATP synthase define residues gating H+ transport from each side of the membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39811–39818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moore K. J., Angevine C. M., Vincent O. D., Schwem B. E., Fillingame R. H. (2008) The cytoplasmic loops of subunit a of Escherichia coli ATP synthase may participate in the proton translocating mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13044–13052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Steed P. R., Fillingame R. H. (2008) Subunit a facilitates aqueous access to a membrane-embedded region of subunit c in Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12365–12372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Steed P. R., Fillingame R. H. (2009) Aqueous accessibility to the transmembrane regions of subunit c of the Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23243–23250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barik S. (1996) Site-directed mutagenesis in vitro by megaprimer PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 57, 203–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jones P. C., Hermolin J., Fillingame R. H. (2000) Mutations in single hairpin units of genetically fused subunit c provide support for a rotary catalytic mechanism in F0F1 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 11355–11360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ishmukhametov R. R., Galkin M. A., Vik S. B. (2005) Ultrafast purification and reconstitution of His-tagged cysteine-less Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1706, 110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Klionsky D. J., Brusilow W. S., Simoni R. D. (1984) In vivo evidence for the role of the ϵ subunit as an inhibitor of the proton-translocating ATPase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 160, 1055–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wiedenmann A., Dimroth P., von Ballmoos C. (2008) Δψ and ΔpH are equivalent driving forces for proton transport through isolated F0 complexes of ATP synthases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 1301–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fillingame R. H. (1976) Purification of the carbodiimide-reactive protein component of the ATP energy-transducing system of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 6630–6637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Penefsky H. S. (1979) A centrifuged-column procedure for the measurement of ligand binding by beef heart F1. Methods Enzymol. 56, 527–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Langemeyer L., Engelbrecht S. (2007) Essential arginine in subunit a and aspartate in subunit c of FoF1 ATP synthase: effect of repositioning within helix 4 of subunit a and helix 2 of subunit c. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 998–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aggeler R., Weinreich F., Capaldi R. A. (1995) Arrangement of the ϵ subunit in the Escherichia coli ATP synthase from the reactivity of cysteine residues introduced at different positions in this subunit. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1230, 62–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Alexander C., Ivetac A., Liu X., Norimatsu Y., Serrano J. R., Landstrom A., Sansom M., Dawson D. C. (2009) Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: using differential reactivity toward channel-permeant and channel-impermeant thiol-reactive probes to test a molecular model for the pore. Biochemistry 48, 10078–10088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Reed P. W. (1979) Ionophores. Methods Enzymol. 55, 435–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dmitriev O. Y., Fillingame R. H. (2007) The rigid connecting loop stabilizes hairpin folding of the two helices of the ATP synthase subunit c. Protein Sci. 16, 2118–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bell R., Kramer J. (1999) Structural chemistry and geochemistry of silver-sulfur compounds: critical review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 18, 9–22 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vincent O. D., Schwem B. E., Steed P. R., Jiang W., Fillingame R. H. (2007) Fluidity of structure and swiveling of helices in the subunit c ring of Escherichia coli ATP synthase as revealed by cysteine-cysteine cross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33788–33794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dautant A., Velours J., Giraud M.-F. (2010) Crystal structure of the Mg·ADP-inhibited state of the yeast F1c10-ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29502–29510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fraga D., Fillingame R. H. (1991) Essential residues in the polar loop region of subunit c of Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase defined by random oligonucleotide-primed mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 173, 2639–2643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Steed P. R. (2010) Proton Transport at the Interface of Subunit c and the Rotor Ring of Escherichia coli ATP Synthase. Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saroussi S., Schushan M., Ben-Tal N., Junge W., Nelson N. (2012) Structure and flexibility of the C-ring in the electromotor of rotary F0F1-ATPase of pea chloroplasts. PLoS One 7, e43045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]