Abstract

Objectives

The detailed course of mental disorders at the acute and subacute stages of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), especially with regard to recovery from sleep disturbances, has not been well characterised. The aim of this study was to determine the course of depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance, following an mTBI.

Setting

We recruited patients with mTBI from three university hospitals in Taipei and healthy participants as control group for this study.

Participants

100 patients with mTBI (35 men) who were older than 20 years, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13–15 and loss of consciousness for <30 min, completed the baseline and 6-week follow-up assessments. 137 controls (47 men) without TBI were recruited in the study. None of the participants had a history of cerebrovascular disease, mental retardation, previous TBI, epilepsy or severe systemic medical illness.

Primary outcome measures

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were assessed for the patients with mTBI at baseline and 6 weeks after mTBI and for the controls.

Results

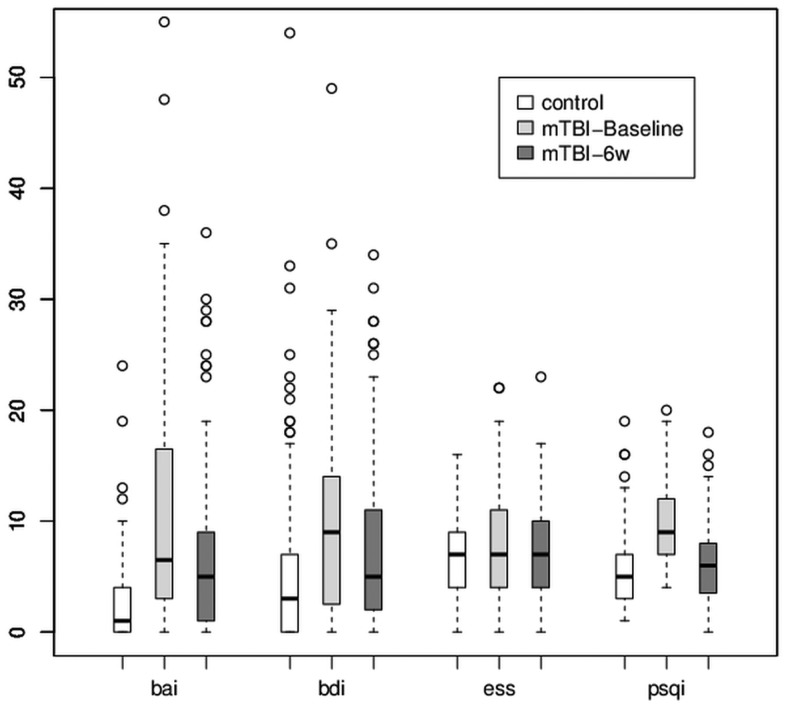

The ESS scores were not significantly different between the mTBI at baseline or at 6 weeks after mTBI and controls. Although the BAI, BDI and PSQI scores of the mTBI group were significantly different than those of the control group at baseline, all had improved significantly 6 weeks later. However, only the PSQI score improved to a level that was not significantly different from that of the control group.

Conclusions

Daytime sleepiness is not affected by mTBI. However, mTBI causes depression and anxiety and diminished sleep quality. Although all these conditions improve significantly within 6 weeks post-mTBI, only sleep quality improves to a pre-mTBI level. Thus, recovery from mTBI-induced sleep disturbance occurs more rapidly than that of mTBI-induced depression and anxiety.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHYSIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Previous reports of the incidence of insomnia among postacute patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) ranged from 2 to 56%. In our study, 90% of the patients with (mTBI) and 44% of the control participants reported sleep disturbances. Our data showed that recovery from sleep disturbance occurred more rapidly among the patients with mTBI than did recovery from postinjury depression and anxiety.

Previous studies have demonstrated significant changes in anxiety-related and depression-related symptoms between 1 week and 3 months following an mTBI. We observed an improvement in the depression and anxiety assessment scores in our mTBI cohort at 6 weeks postinjury. Nonetheless, the Beck Depression Inventory II and the Beck Anxiety Inventory scores differed significantly between the mTBI and control groups at 6-week postinjury assessment.

Some of our patients with mTBI may have used medications before or after suffering mTBI that may have influenced their assessment scores. It is also possible that some of our patients with mTBI may have had unrelated diseases or preinjury conditions that were not identified before or during their participation in our study. In addition, we investigated only the subacute stages of depression, anxiety and diminished sleep quality, rather than the chronic stages of these diseases.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TMI) and mild TBI (mTBI) are major public health problems. Studies in Australia have estimated lifetime costs of over $A 2.5 million per TMI survivor.1 Headache, blurred vision, fatigue and sleep disturbance are the most common physical symptoms following a brain injury.2 Previous studies have reported that the symptom scores following an mTBI were equal to that of control patients within 7 days postinjury.3

However, increasing evidence suggests that the risk of developing a psychiatric disorder increases following an mTBI.4 Although multiple studies have investigated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the risk of other disorders, such as depression, has also been found to increase following an mTBI.5 The most common psychiatric disorders during the first 12 months following an injury are depression, anxiety disorder and agoraphobia.4

Diminished sleep quality is one of the most commonly reported symptoms following an mTBI,6 and depression and anxiety are also prevalent. However, these conditions are often under-reported, and may become chronic in the absence of treatment. The objectives of our study were to characterise the course of post-mTBI depression, anxiety and diminished sleep quality during a 6-week follow-up, and to compare the baseline and 6-week clinical assessments of patients with mTBI with those of healthy participants.

Methods

Participants and study design

Our prospective study was approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board of Taipei Medical University. Eligible patients aged ≥20 years who were treated in an emergency room within 24 h after closed head trauma were recruited from three hospitals in Taiwan between January 2011 and July 2012. The definition of mTBI was based on the diagnostic criteria established by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, which consist of a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13–15 at presentation and loss of consciousness for <30 min. Patients with a history of cerebrovascular disease, mental retardation, previous TBI, epilepsy or severe systemic medical illness were excluded from our study. The inclusion criteria for the healthy control participants were no brain injury history and age over 20 years.

Patients were initially contacted through phone. A total of 607 patients with mTBI were recruited for our study, among whom 250 (41.19%) provided informed consent, and completed a baseline assessment during an initial evaluation within 1 month after experiencing an mTBI. Six weeks after completing the baseline assessment, 100 (40%) patients with mTBI completed the final assessment. The baseline and 6-week assessments consisted of four investigator-administered questionnaires, namely the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),7 the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI),8 the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)9 and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).10

Outcome measures

The patients’ demographic information, injury-related data and smoking and drinking history were recorded at the baseline evaluation. Chinese versions of the BDI, the BAI, the ESS and the PSQI were used in our study.11–13 Depression was assessed using the BDI, which scored the patient's selection of one of four possible responses to 21 multiple-choice items on a scale of 0–3 based on their response. The severity of anxiety symptoms was assessed using the BAI, which also scored the patient's selection of one of four possible responses to 21 multiple-choice items on a scale of 0–3 based on their response. A high score on the BAI indicates a high level of anxiety. Daytime sleepiness was subjectively assessed using the ESS, which asked the patient to rate their risk of falling asleep on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3) in eight different situations. Overall sleep quality was assessed using the PSQI, which evaluated seven aspects of sleep quality. A high overall score on the PSQI indicates a poor sleep quality.

Statistical methods

Associations between the categorical variables were evaluated using a χ² analysis, and the Fisher exact test was used when at least one of the values was <5. Associations between the normally distributed continuous variables were evaluated using t tests, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to evaluate the continuous variables with an asymmetrical distribution. Paired t tests and a paired Mann–Whitney U test were used to evaluate the intragroup differences between the baseline and 6-week assessments for normally and asymmetrically distributed data, respectively. In this study, all outcomes were abnormally distributed, thus the non-parametric method was used. In addition, generalised linear regression analyses were conducted for outcomes with or without adjustment for age and sex. All the statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software, V.3.0.1 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

The demographic information and clinical data of all the mTBI and control participants who were initially enrolled in the study are shown in table 1. Six weeks following their baseline assessment, 150 patients could not be contacted, or declined to participate further in our study. The age, sex, education level, smoking status, alcohol use, proportion reporting depression, mechanism of injury and GCS, BDI, ESS scores of patients who completed the study did not differ significantly from those of patients who did not complete the study. The patients who did not complete the study had lower mean scores for the BAI and the PSQI than the patients who completed the study.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of all patients with mTBI initially enrolled in our study

| Lost to follow-up | Completed 6-week follow-up | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.88 | 39.53 | NS |

| Male/female (n) | 56/94 | 35/65 | NS |

| Education (years) | 15.04 | 15.46 | NS |

| Smoker (N/Y) | 113/37 | 82/18 | NS |

| Drink alcohol (N/Y) | 94/56 | 58/ 42 | NS |

| Headache (N/Y) | 50/100 | 25/75 | 0.02 |

| Depression (N/Y) | 91/59 | 51/49 | NS |

| GCS | 14.80 | 14.98 | NS |

| Mechanism of injury | |||

| Transportation accident | 77 | 39 | NS |

| Falls | 40 | 34 | |

| Other | 33 | 27 | |

| BAI | 7.85 | 10.74 | .03 |

| BDI | 8.19 | 9.80 | NS |

| ESS | 6.89 | 7.95 | NS |

| PSQI | 6.27 | 9.51 | <0.01 |

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory II; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; NS, p>0.05; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

The demographic information and clinical data of the 100 patients with mTBI and the 137 control participants who completed the study are shown in table 2. The mean age of the mTBI group was significantly higher than the mean age of the control group. The proportions reporting alcohol use, headache and depression were significantly different between the mTBI and control groups. The percentages of patients with mTBI who reported headache or depression were higher than those of the control group. Transportation accidents and falls caused 39% and 34% of the mTBI cases, respectively. Considering the clinical cut-off for each questionnaire, most of the control patients did not have depression, anxiety, daytime sleepiness or diminished sleep quality, whereas most of the patients with mTBI had high PSQI scores.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical data of the patients with mTBI and the control participants who completed the 6-week follow-up

| mTBI | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (n) | 100 | 137 | |

| Age (years) | 39.53 | 29.86 | <0.001 |

| Male/female (n) | 35/65 | 47/90 | NS |

| Education (years) | 15.46 | 14.91 | 0.045 |

| Smoker (N/Y) | 82/18 | 115/22 | NS |

| Drink (N/Y) | 58/42 | 51/82 | <0.01 |

| Headache (N/Y) | 25/75 | 98/39 | <0.01 |

| Depression (N/Y) | 51/49 | 103/34 | <0.01 |

| GCS | 14.98 | – | – |

| Questionnaires | |||

| BAI >7 (N/Y) | 57/43 | 125/12 | <0.01 |

| BDI >9 (N/Y) | 53/47 | 111/26 | <0.01 |

| ESS >9 (N/Y) | 66/34 | 108/29 | <0.01 |

| PSQI >5 (N/Y) | 10/90 | 77/60 | <0.01 |

| Mechanisms of injury | |||

| Transportation accident | 39 | – | – |

| Falls | 34 | – | – |

| Other | 27 | – | – |

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory II; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; NS, p>0.05; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

The mean scores of the four outcome measures are shown in figure 1. The average scores for the patients with mTBI at baseline were the highest. After 6 weeks, the average scores for the patients with mTBI decreased. The differences between the outcomes of the mTBI and control groups are shown in table 3. The average baseline and 6-week BAI scores for mTBI group were 10.74 and 7.23, respectively. The BAI scores of the patients in the mTBI group significantly improved at 6 weeks postinjury. However, the mean BAI scores for the mTBI group for the baseline and 6-week assessments were significantly different from those of the control group at the baseline assessment. The mean BDI scores of the mTBI group were 9.8 and 7.99 at the baseline and 6-week assessments, respectively. The mean BDI score for mTBI group significantly decreased to the value of 1.81 at 6 weeks postinjury. The mean BDI score of the control group was 5.72. The mean BDI scores of the mTBI group were significantly different from those of the control group.

Figure 1.

Box plot of the baseline and 6-week postinjury assessments of the clinical outcomes. White bars represent the data for the control group. Light grey and dark grey bars represent the patients with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) at baseline and 6 weeks postinjury, respectively. From left to right, the data for the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores are represented.

Table 3.

Differences between control participants and patients with mTBI at baseline and 6 weeks postinjury

| BAI | BDI | ESS | PSQI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTBI baseline vs control | 8.02* | 4.08* | 1.33 | 3.81* |

| mTBI 6 weeks vs control | 4.51* | 2.27* | 0.87 | 0.7 |

| mTBI baseline vs mTBI 6 weeks† | 3.51* | 1.81* | 0.46 | 3.11* |

*p<0.05.

†paired t test.

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory II; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

No significant difference was observed between the baseline and 6-week ESS scores for the mTBI group. The mean daytime sleepiness score for the control group was 6.62, which was not significantly different from that of the mTBI group. The mean baseline PSQI score for the mTBI group was greater than 9, which was higher than the clinical cut-off point of 5. In addition, the mean PSQI score of mTBI at baseline assessment was higher than the mean score of 5.7 for the control group. The mean 6-week PSQI score for the mTBI group improved significantly to 6.4. The sleep quality of the mTBI group at 6 weeks postinjury was not significantly different from that of the control group. Owing to the significant difference in mean age between the mTBI and control groups and the predominance of women in both groups, we performed generalised linear regression analysis of the outcome measures with adjusting for age and sex (table 4). The differences in depression, anxiety and sleep quality between the mTBI and control patients kept significance after adjusting for age or sex. However, sex was found to be a significant predictor of sleep quality, anxiety and depression in the baseline and 6-week assessments. After adjusting for age and sex, the ESS score was significantly different between the control and mTBI groups at the baseline and 6-week assessments, and age was determined to be a significant predictor of daytime sleepiness. In addition, the scores for all four outcome measures were higher among women than among men.

Table 4.

Generalised linear regression coefficient estimates of four measurements in controls and patients with mTBI at baseline and 6 weeks postinjury

| Control vs mTBI (baseline) |

Control vs mTBI (6 weeks) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAI | BDI | ESS | PSQI | BAI | BDI | ESS | PSQI | |

| mTBI | 1.4* | 0.567* | 0.245* | 0.487* | 1.026* | 2.632* | 1.309* | 0.557 |

| Age | 0.0007 | −0.003 | −0.007* | 0.003 | −0.001 | −0.035 | −0.045* | 0.016 |

| Women | 0.437* | 0.056* | 0.137* | 0.137* | 0.562* | 2.945* | 1.263* | 1.170* |

*p<0.05.

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory II; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that 85% of patients with mTBI demonstrate improvement in psychiatric-related symptoms, whereas the remainder develop chronic psychosocial problems.14–16 Often presenting with anxiety, depression or sleep disturbances, patients with TBI are at an increased risk of developing a psychiatric disorder within 3 months to 1-year postinjury.4 It is unclear whether post-mTBI sleep disturbances are related to depression or anxiety. Thus, sleep disturbance may be a risk factor of subsequent depression. A meta-analysis of 21 studies demonstrated that insomnia patients have a twofold risk of developing depression.17 The detailed course of post-mTBI depression, anxiety and diminished sleep quality, especially during the early stages of recovery, has not been well characterised.

We examined the early stages of recovery from mTBI by using self-reported measures of depression, anxiety, sleep quality and daytime sleepiness. Most of them were injured by transportation accident and falls. Other mechanism of injury included hit by something, and sport injury. There was no participant who was injured by an industrial accident. We determined that daytime sleepiness is not significantly affected by mTBI. The anxiety and depression symptoms in the mTBI group improved by the sixth week of recovery, but remained more severe than those of the control participants. However, sleep quality significantly improved within 6 weeks of experiencing mTBI, returning to a level that did not differ significantly from that of the control group. These results indicate that recovery from diminished sleep quality occurred more rapidly than did recovery from depression and anxiety.

Our prospective cohorts contained more women than men, and the mean ages of the mTBI and control groups differed significantly. Thus, we adjusted our analysis for effects of age and sex. The BAI, BDI, PSQI and ESS scores were influenced by sex. However, our results demonstrated that the BAI, BDI and PSQI scores were significantly affected by mTBI, whereas the ESS scores were not. We found the women in the mTBI group reported more severe symptoms for depression, anxiety and diminished sleep quality at baseline. After 6 weeks of recovery, although the depression-related and anxiety-related symptoms of male and female patients with mTBI improved, those of the female patients with mTBI remained more severe than those of the male patients with mTBI. Female patients with mTBI also reported more severe symptoms related to diminished sleep quality and daytime sleepiness than did male patients with mTBI.

Previous reports of the incidence of insomnia among postacute patients with TBI ranged from 2% to 56%.18 19 Bryan20 found that sleep disturbance increases in patients who suffer a repetitive TBI. In our study, 90% of the patients with mTBI and 44% of the control participants reported sleep disturbances. The average score of PSQI in the control group (5.7) is higher than the previously published values (2.7),10 but it is close to the result of another study in Taiwan also by use of the Chinese PSQI study in healthy group (5.7).13 It may result from the different versions of questionnaire (English and Chinese) or other uncertain reasons. Our data showed that recovery from sleep disturbance occurred more rapidly among the patients with mTBI than did recovery from postinjury depression and anxiety. There are two possible reasons for this finding. Sleep disturbance may be an independent symptom of mTBI that alters the circadian rhythm through injury-related changes in gene expression.21 Alternatively, sleep disturbance may simply be a symptom of depression or anxiety that improves early during recovery.22

Previous studies have demonstrated significant changes in anxiety-related and depression-related symptoms between 1 week and 3 months following an mTBI.23 We observed improvement in the depression and anxiety assessment scores in our mTBI cohort at 6 weeks postinjury. Nonetheless, the BDI and the BAI scores differed significantly between the mTBI and control groups at the 6-week postinjury assessment.

Depression and PTSD have been shown to be critical mediators of the recovery of physical health following an mTBI.24 Multiple studies have investigated the incidence of PTSD following TBI.25 Psychiatric comorbidities have been associated with PTSD following TBI, and depression was shown to be a predictor of the post-TBI chronicity of PTSD.26 27 We did not explore the role of PTSD in recovery from depression, anxiety and diminished sleep quality, but we speculate that PTSD is associated with all of these mental disorders in patients with mTBI.

Certain limitations to our findings should be considered. First, some of our patients with mTBI may have used medications before or after suffering mTBI that may have influenced their assessment scores. Second, it is possible that some of our patients with mTBI may have had unrelated diseases or preinjury conditions that were not identified before or during their participation in our study. Third, we investigated only the subacute stages of depression, anxiety and diminished sleep quality, rather than the chronic stages of these diseases. In addition, REM sleep plays an important role in mood disorders. The changes of REM sleep after mTBI are still controversial.28 29 This is certainly a major issue for the study. However, sleep architecture was not measured in our study. Although long-term observational studies are required to confirm our findings, our results provide valuable information for understanding the development and recovery of mental disorders following an mTBI.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: H-P M participated in conception, design and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and its final approval; J-C O participated in analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and its final approval; C-T Y participated in acquisition of data and its final approval; D W and S-H T provided final approval of the manuscript; W-T C participated in conception, design and final approval of the manuscript; C-J H participated in conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and its final approval.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 98-2321-B-038-005-MY3, NSC 101-2321-B-038-005, DOH 101-TD-B-111-003).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Taipei Medical University—Joint Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Access Economics Pty Limited The economic cost of spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury in Australia. Geelong, Victoria, Australia: Victorian Neurotrauma Initiative, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense, 2009. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/mtbi/concussion_mtbi_full_1_0.pdf (accessed 18 Jun 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCrea M, Iverson GL, McAllister TW, et al. An integrated review of recovery after mild traumatic brain injury(MTBI): implications for clinical management. Clin Neuropsychol 2009;23:1368–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant RA, O'Donnell M, Creamer M, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of traumatic injury. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:312–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Donnell ML, Creamer M, Bryant RA, et al. Posttraumatic disorders following injury: an empirical and methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev 2003;23:587–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orff H, Ayalon L, Drummond S. Traumatic brain injury and sleep disturbance: a review of current research. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2009;24:155–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometirc properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988;56:893–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 9.John MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng YP, Wei LA, Goa LG, et al. Applicability of the Chinese Beck Depression Inventory. Compr Psychiatry 1988;29:484–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen NH, Johns MW, Li HY, et al. Validatio of a Chinese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Qual life Res 2002;11:817–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality index in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1943–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruff R. Two decades of advances in understanding of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rebabil 2005;20:5–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood RL. Understanding the ‘miserable minority’: a diathesis-stress paradigm for postconcussional syndrome. Brain Injury 2004;18:1135–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazarian J, McClung J, Shah M, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in the US 1998–2000. Brain Injury 2005;19:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord 2011;135:10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutherford WH, Merrett JD, McDonald JR. Symptoms at one year following concussion from minor head injuries. Injury 1977;1:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beetar JT, Guilmette TJ, Sparadeo FR. Sleep and pain complaints in symptomatic traumatic brain injury and neurologic populations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77:1298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryan CJ. Repetitive traumatic brain injury (or concussion) increases severity of sleep disturbance among deployed military personnel. Sleep 2013;36:941–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palagini L, Biber K, Riemann D. The genetics of insomnia—evidence for epigenetic mechanisms? Sleep Med Rev 2013:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, et al. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry 1996;30:411–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponsford J, Cameron P, Fitzqerald M, et al. Long-term outcomes after uncomplicated mild traumatic brain injury: a comparison with trauma controls. J Neurotrauma 2011;28:937–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas Jeffrey L., et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med 2008;358:453–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donnell ML, Creamer M, Pattison P, et al. Psychiatric morbidity following injury. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:507–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, et al. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:630–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McFarlane AC, Papay P. Multiple diagnoses in posttraumatic stress disorder in the victims of a natural disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992;180:498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gosselin N, Lassonde M, Petit D, et al. Sleep following sport-related concussions. Sleep Med 2009;10:35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shekleton JA, Parcell DL, Redman JR, et al. Sleep disturbance and melatonin levels following traumatic brain injury. Neurology 2010;74:1732–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.