Background: The mechanism underlying cotranslational protein degradation remains poorly understood.

Results: The nuclear import factor Srp1 binds ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides. Sts1 mediates the interaction between Srp1 and the proteasome.

Conclusion: Srp1 and Sts1 couple proteasomes to nascent polypeptides emerging from the ribosome for cotranslational degradation.

Significance: This study unveils a novel role for Srp1 and Sts1 in cotranslational protein degradation.

Keywords: Proteasome, Protein Degradation, Protein Dynamics, Protein Processing, Protein Turnover, Cotranslational Protein Degradation, Nuclear Import Factor Srp1, Ubiquitin-independent Degradation

Abstract

Cotranslational protein degradation plays an important role in protein quality control and proteostasis. Although ubiquitylation has been suggested to signal cotranslational degradation of nascent polypeptides, cotranslational ubiquitylation occurs at a low level, suggesting the existence of an alternative route for delivery of nascent polypeptides to the proteasome. Here we report that the nuclear import factor Srp1 (also known as importin α or karyopherin α) is required for ubiquitin-independent cotranslational degradation of the transcription factor Rpn4. We further demonstrate that cotranslational protein degradation is generally impaired in the srp1–49 mutant. Srp1 binds nascent polypeptides emerging from the ribosome. The association of proteasomes with polysomes is weakened in srp1–49. The interaction between Srp1 and the proteasome is mediated by Sts1, a multicopy suppressor of srp1–49. The srp1–49 and sts1–2 mutants are hypersensitive to stressors that promote protein misfolding, underscoring the physiological function of Srp1 and Sts1 in degradation of misfolded nascent polypeptides. This study unveils a previously unknown role for Srp1 and Sts1 in cotranslational protein degradation and suggests a novel model whereby Srp1 and Sts1 cooperate to couple proteasomes to ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides.

Introduction

Protein homeostasis is maintained by a complex quality control system that controls a delicate balance between protein synthesis, folding, and degradation (1–7). Remarkably, proteins are monitored by the quality control system at the moment they emerge from the ribosome. The N-terminal end of a nascent polypeptide is available for folding before the other end has been synthesized. Cotranslational folding helps to reduce aggregation of translational intermediates and promote accurate folding of newly made polypeptides. However, cotranslational folding is a complicated task that requires the participation of multiple chaperone proteins and is not always successful. To prevent the accumulation of misfolded, potentially toxic proteins arising from inefficient folding and translational errors, the cell must degrade the misfolded polypeptides immediately after their synthesis or even before reaching their mature size. This process is referred to as cotranslational protein degradation. It has been estimated that, under physiological conditions, as many as 30% of total nascent polypeptides are cotranslationally degraded by the proteasome in mammalian cells (8). This finding led to the elaboration of the so-called DRiP (defective ribosomal products) hypothesis by proposing that cotranslational degradation products serve as an important source of MHC class I peptides (8–13). Despite the physiological significance, the underlying mechanism of cotranslational protein degradation remains poorly understood. One of the central questions is how the proteasome targets ribosome-bound nascent chains destined for cotranslational degradation. Early studies suggested that ubiquitylation of nascent polypeptides provides a targeting signal for the proteasome (8, 14–16). This suggestion is supported by the identification of several ribosome-bound ubiquitin (Ub)2 ligases, including Not4 and Lin1 (17, 18). Interestingly, cotranslational ubiquitylation appears to occur at a low level. Two studies recently revealed that only 1–6% of nascent polypeptides are ubiquitylated in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (19, 20). This likely represents only a fraction of the nascent polypeptides that undergo cotranslational degradation (14). We speculate that there may be an alternative route for the handover of nascent polypeptides to the proteasome, particularly for those that are not modified by the Ub system.

The number of proteasomal substrates that are degraded without prior ubiquitylation continues to grow. One of the examples is the transcription factor Rpn4, which regulates the proteasome genes in S. cerevisiae (21, 22). Rpn4 is an extremely short-lived protein (t½ <2 min) and is degraded by the proteasome, thereby forming a negative feedback circuit (23, 24). The degradation of Rpn4 can be mediated via the canonical Ub-dependent pathway, or it occurs in an Ub-independent manner (25–27). The Ub-dependent degron of Rpn4 is located in an acid domain including residues 211–229, whereas the Ub-independent degron is mapped to its N-terminal domain, consisting of the first 80 residues (28–30). Therefore, Rpn4Δ211–229 can serve as a model molecule for studying the mechanism underlying Ub-independent degradation of Rpn4.

In this study, we report that Rpn4Δ211–229 is degraded cotranslationally and that, unexpectedly, this process requires the nuclear import factor Srp1 (also known as importin α or karyopherin α). Moreover, cotranslational protein degradation is generally impaired in the srp1–49 mutant expressing a defective version of Srp1. We show that Srp1 directly binds nascent polypeptides emerging from the ribosome and that the association of proteasomes with polysomes is weakened in srp1–49. The interaction between Srp1 and the proteasome is mediated by Sts1, a multicopy suppressor of srp1–49. The srp1–49 and sts1–2 mutants are hypersensitive to conditions that increase protein misfolding. Our study unveils a new role for Srp1 and Sts1 in cotranslational protein degradation and suggests a model whereby Srp1 and Sts1 couple proteasomes to ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

The yeast strains used in this study included W303-1A (MATa ura3-1 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11 ade2-1 can1-100), JLY555 (MATα ura3-1 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11 ade2-1 can1-100 srp1-49, provided by G. Fink and M. Nomura), LCY827 (MATa ura3-1 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11 ade2-1 sts1-2, a gift from K. Madura), EJY 140 (MATa trp1-Δ63 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 lys2-801 rpn4Δ::LEU2, see Ref. 31), and YXY206 (MATa trp1-Δ63 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 lys2–801 PRE1-Flag-6His::YIplac211, see Ref. 23). Details of the plasmid constructs are available upon request. The replacement vector p304Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA for site-specific recombination to generate strains expressing Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA from the chromosomal locus has been described previously (32). For protein expression and/or purification from Escherichia coli, the pET11d vector was used to express C-terminally FLAG-tagged Rpn4, whereas N-terminally His-tagged Srp1 and Srp1E145K were expressed from the pET30 vector. To produce GST fusion proteins, DNA sequences encoding Srp1, Srp1E145K, Rpn41–229, and Rpn411–229 were subcloned into the pGEX-4T3 vector. Note that Rpn41–229 and Rpn411–229 were fused N-terminally to the GST moiety. The PDR5 deletion vector pYM31 (Δpdr5::hisG-URA3-hisG) was obtained from K. Kuchler. Knockout of PDR5 from W303-1A and srp1–49 was carried out as described previously (33).

Yeast Two-hybrid Screening

The first 151 amino acids of Rpn4 were N-terminally fused to the GAL4 DNA binding domain (GAL4DB) to serve as bait. Rpn41–151-GAL4DB was expressed from the CUP1 promoter on the vector pRS426. The two-hybrid DNA libraries and the host S. cerevisiae strain PJ69-4A were gifts from P. James and E. Craig (34). PJ69-4A expressed three reporters from different inducible promoters: PGAL1-HIS3, PGAL2-ADE2, and PGAL7-lacZ. The bait plasmid was transformed into PJ69-4A. Ura+ transformants were then transformed with the two-hybrid libraries, with selection directly on synthetic complete medium lacking ura and ade, SC (-ura, -ade), plates at 30 °C. Ade+ colonies were isolated, and library plasmids were rescued from the Ade+ transformants and retransformed into PJ69-4A expressing either the bail plasmid or a control vector. The plasmids that induced ADE2 in the presence but not in the absence of the bait plasmid were analyzed by sequencing. One clone thus identified encoded a 478-residue fragment (positions 65–542) of the SRP1 ORF.

TCA Precipitation Assay

A small volume (1.5 μl) of lysate prepared from [35S]methionine (Met)- and cysteine (Cys)-labeled cells was spotted on filter paper, which was then soaked in 10% TCA solution, air dried, rinsed in 100% ethanol, and air-dried. This process was repeated three times, and then the 35S activity remaining on the filter paper was counted by a liquid scintillation counter. The TCA precipitation assay was used to adjust the input of cell extracts for immunoprecipitation and to measure bulk degradation of newly synthesized proteins and protein synthesis rates.

Pulse-Chase Analysis and Cotranslational Degradation Assay

Exponentially growing cells in synthetic defined (SD) medium containing essential amino acids were harvested and resuspended in the same medium supplemented with 0.15 mCi of [35S]Met/Cys for pulse labeling. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in the same SD medium with CHX (0.2 mg/ml) and excess cold Met (2 mg/ml) and Cys (0.4 mg/ml) and chased for various time periods. An equal volume of sample was withdrawn at each time point. Labeled cells were lysed in 2× SDS buffer (2% SDS, 30 mm dithiothreitol, and 90 mm Na-HEPES (pH 7.5)) by incubation at 100 °C for 5 min. Supernatants were recovered by centrifugation and diluted 20-fold with buffer A (150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 50 mm Na-HEPES (pH 7.5), and 1% Triton X-100) before being subjected to IP. The volumes of supernatants applied to IP were adjusted to equalize the amounts of 35S incorporated into proteins using the TCA precipitation assay. To measure cotranslational degradation of ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides, cells were treated with 50 μm of MG-132 for 10 min before pulse labeling. Labeled cells were resuspended in buffer A and disrupted by vortex with glass beads. 100 μl of each cell extract was loaded onto a 25% sucrose cushion in buffer B (50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 140 mm NaCl, and 5 mm MgCl2), followed by ultracentrifugation at 85,000 rpm for 90 min at 4 °C using a TLA 100.2 rotor (Beckmann). Ribosome-nascent chain complexes (RNCs) were recovered and solubilized in buffer C (25 mm Na-HEPES, 80 mm KAOc, 1 mm Mg(OAc)2 (pH 7.5)) and applied to the TCA precipitation assay to quantify the remaining 35S-labeled nascent polypeptides and to autoradiography after SDS-PAGE.

In Vitro Transcription/Translation Reactions and Binding of Rpn4 Nascent Chains

In vitro transcription/translation reactions were carried out using the TnT coupled transcription/translation system (Promega) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. In a typical reaction, a prereaction mixture containing [35S]Met/Cys was prepared without a DNA template. Aliquots of the mixture were added to reaction tubes containing various DNA templates and were incubated for 90 min at 30 °C. The reactions were terminated by the addition of an equal volume of ice-cold buffer C supplemented with DNase I (5 μg/ml), CHX (200 μg/ml), and MG132 (50 μm). The coding sequences for Rpn4, Rpn4Δ1–79, and Srp1 were subcloned into the T7 promoter-based vector pET11d. To generate stop codon-less DNA templates, the Rpn4 and Rpn4Δ1–79 vectors were digested with the restriction enzyme EcoRI. RNCs were isolated by applying the reaction mixture to ultracentrifugation through a 0.5 m sucrose cushion. The pelleted RNCs containing 35S-labeled Rpn41–415 or Rpn480–415 and unloaded ribosomes were rinsed gently twice with buffer C, dissolved in sample buffer, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. For the RNC binding assay, RNCs containing Rpn41–415 and Rpn480–415 were prepared as above but without using [35S]Met/Cys. 35S-labeled Srp1 produced by the in vitro transcription/translation reaction was collected from the supernatant after ultracentrifugation of the reaction mixture at 100,000 rpm for 20 min. This step was able to get rid of the ribosome-bound Srp1. RNCs and unloaded ribosomes were resuspended in buffer C and incubated with 35S-labeled Srp1. The mixture was ultracentrifuged through a 0.5 m sucrose cushion as above to remove unbound Srp1. RNC- or ribosome-bound Srp1 was resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized and quantified using a PhosphorImager.

Puromycin Labeling and Nascent Chain Binding Assay

RNCs were isolated through ultracentrifugation as described above. RNC pellets were dissolved in buffer D (10 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 400 mm KCl, and 3 mm MgCl2) and incubated with 4 μm of puromycin for 1 h at 30 °C. The reversible cross-linker DTSSP (2 mm) was then added to the reaction and kept at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction mixture was heated at 95 °C for 5 min in the presence of 1% SDS. The denatured supernatant was then diluted 10-fold with buffer A before being subjected to IP with anti-puromycin (KeraFAST, Boston, MA) or anti-Srp1 antibody (a gift from M. Nomura). The precipitates were eluted with sample buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 2 mm DTT), resolved by SDS-PAGE, and detected by immunoblotting analysis with either anti-Srp1 or anti-puromycin antibody.

Sucrose Gradient Cosedimentation Assay

Yeast cells grown in 1 liter of YPD (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose) medium to A600 ∼1.2 were harvested, and cell pellets were ground to a fine powder in the presence of liquid nitrogen. Cell extracts were prepared by dissolving the cell powder in buffer E (50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.2% TritonX-100) containing 2 mm ATP, protease inhibitor mixture, and 50 μm MG132, followed by a 30-min incubation on ice. Unbroken cells and debris were removed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 2 min. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method and adjusted to 15 mg/ml. The sucrose gradient sedimentation assay was conducted following a previous procedure (17), with some modifications. Briefly, a 10–50% (w/v) sucrose gradient was prepared by layering sucrose solutions of successively decreasing concentrations in buffer F (10 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 140 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20, and 2 mm ATP) upon one another. 200 μl of cell lysate was carefully loaded onto the sucrose gradient and centrifuged at 38,500 × g for 18 h at 4 °C using a SW55Ti rotor (Beckman). Fractions were collected manually from the top to the bottom of the gradient. Proteins were precipitated from each fraction by chloroform/methanol for concentration and removal of sucrose. Precipitated proteins were dissolved in sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a PVDF membrane for immunoblotting analysis. For the detection of cosedimented Srp1, proteasomes, and ribosomes, the membranes were first incubated with polyclonal antibodies against Srp1 and Rpn12 (a gift from D. Skowyra) or 20 S proteasome (Infiniti Research) and then with a monoclonal anti-L3 antibody (a gift from J. Warner). After removing unbound antibodies by two washes with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, fluorescent dye-conjugated rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor 680, Invitrogen) and mouse IgG (IRDye 800, Rockland) were applied simultaneously to the membranes, visualized, and quantified by an Odyssey infrared imaging system.

GST Pulldown Assay

GST fusion proteins and other proteins were expressed in E. coli (BL21) by induction with 0.3 mm of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h at 25 °C. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and suspended in buffer G (50 mm Na-HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.2% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with 0.2 mg/ml of lysozyme and protease inhibitor mixture and lysed by ultrasonication. Cell extracts were recovered by centrifugation in a TLA-100.2 rotor (Beckman) for 1 h at 100,000 rpm at 4 °C. Input amounts of purified proteins or cell lysates were determined before the pulldown assays. GST fusion proteins were applied to 10 μl of glutathione-agarose in 0.5 ml of buffer G and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Unbound proteins were removed by three washes in buffer A and equilibrated with buffer G. Cell extracts or purified proteins were applied to the equilibrated glutathione-agarose in 0.5 ml of buffer G and allowed to incubate for 3 h at 4 °C. After three washes in buffer G, bound proteins were eluted with sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and examined by immunoblotting analysis with anti-FLAG (Sigma) and anti-Srp1 antibodies, respectively. For the proteasome pulldown assay, GST-Srp1 or GST-Srp1E145K was loaded on glutathione-agarose in the presence or absence of his-Sts1 and equilibrated with buffer H (25 mm Na-HEPES (pH 7.8), 5 mm MgCl2, 25 mm KCl, and 2 mm ATP). 5 μg of purified yeast 26 S proteasomes bearing a His-tagged Pre1 subunit was applied to the pulldown assay. Retained proteasomes were detected by immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Yeast proteasomes were purified as described previously (28).

RESULTS

Srp1 Is Involved in Ub-independent Cotranslational Degradation of Rpn4

To understand the mechanism of Ub-independent degradation of Rpn4, we set out to identify proteins that interact with the N-terminal domain of Rpn4 by conducting a yeast two-hybrid screen. The first 151 amino acids of Rpn4 were N-terminally fused to the GAL4 DNA binding domain (GAL4DB) to serve as bait. One of the clones thus isolated encodes a large fragment of Srp1 including residues 65 to 542. Interestingly, the Srp1 fragment interacted with Rpn41–151-GAL4DB but not Rpn411–151-GAL4DB (Fig. 1A), indicating that the N-terminal 10 residues of Rpn4 are essential for the interaction. This was further confirmed by pulldown assays in which GST-Srp1 was able to retain Rpn4 but not Rpn4Δ1–10 (Fig. 1B). Vice versa, Srp1 was pulled down by Rpn41–229-GST but not Rpn411–229-GST (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that Srp1 binds the Ub-independent degron of Rpn4.

FIGURE 1.

Srp1 binds to the N-terminal domain of Rpn4. A, yeast two-hybrid assay showing the interaction between Srp1 and Rpn4. The isolated Srp1 clone (GAL4AD-Srp165–542) from two-hybrid screening interacted with Rpn41–151-GAL4DB but not Rpn411–151-GAL4DB. B, Rpn4 but not Rpn4Δ1–10 was pulled down by GST-Srp1. C, Srp1 was retained by GST fusion with Rpn41–229 but not Rpn411–229. C-terminally FLAG-tagged Rpn4 and Rpn4Δ1–10 and N-terminally his-tagged Srp1 were expressed in E. coli cells. Input of GST fusion proteins in the pulldown assays was examined by Coomassie Blue staining (B and C, bottom panels).

SRP1, encoding a 542-amino acid polypeptide, was originally identified as a suppressor of mutations in two RNA polymerase I subunits, Rpa190 and Rpa135 (35). Subsequent work firmly established Srp1 as a nuclear import factor, and for this reason, Srp1 is also known as importin α or karyopherin α (Kap60) (36–38). Srp1 forms a heterodimer with Kap95 (importin β or karyopherin β) to transport proteins carrying a classical nuclear localization signal to the nucleus (39–41). Srp1 is responsible for targeting the nuclear localization signal, whereas Kap95 interacts with the nuclear pore complex. The finding that Srp1 interacts with the N-terminal domain of Rpn4 prompted us to examine whether Srp1 plays a role in Ub-independent degradation of Rpn4. We took advantage of the srp1–49 mutant that expresses a defective Srp1 protein carrying an E145K missense mutation (Srp1E145K) (36). Using site-specific recombination, we replaced the endogenous RPN4 with an allele encoding C-terminally triple hemagglutinin (3HA)-tagged Rpn4Δ211–229 (Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA) in srp1-49 and a congenic WT strain, resulting in strains YXY470 (srp1–49) and YXY468 (SRP1). Rpn4Δ211–229 lacks the Ub-dependent degron and is degraded independently of ubiquitylation (25, 29). srp1–49 is a temperature-sensitive mutant and does not grow at 37 °C. At the semipermissive temperature (30 °C), there is no complete block but rather a slowdown of growth, indicating that the activity of Srp1 is impaired at 30 °C. To avoid unexpected, perhaps complicated, phenotypes associated with the restrictive temperature, we decided to perform a pulse-chase analysis to compare the degradation of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA in YXY468 and YXY470 at 30 °C. Cells were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 5 min and chased for 0, 5, and 15 min in the presence of CHX and excess cold Met/Cys. The kinetics of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA turnover were not much different between these two strains during the chase period (Fig. 2, A and B). However, we repeatedly detected a stronger (>2-fold) Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA signal at 0 min (zero time) in YXY470 than in YXY468. Similar results were obtained when the expression of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA was driven by the copper-induced CUP1 promoter from a low-copy plasmid in WT and srp1–49 cells (Fig. 2, C and D). We noticed that protein synthesis was modestly slower in srp1–49 than in WT cells (Fig. 2E). These results indicate that the higher level of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA at zero time in srp1–49 is not caused by up-regulation of transcription and/or translation.

FIGURE 2.

Ub-independent cotranslational degradation of Rpn4 is impaired in srp1–49. A, pulse-chase analysis for the degradation of newly synthesized Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA expressed from the native RPN4 locus in WT and srp1–49 cells. Cells were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 5 min and chased for different intervals as indicated. Cell extracts were subjected to IP with an anti-ha antibody, followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA is marked by an arrow. B, decay curves of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA. 35S-labeled Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA from A was quantified by a PhosphorImager. Remaining 35S-Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA at each time point was plotted as a percentage of that at time 0. Data are mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, pulse-chase analysis was carried out as in A, except that Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA was expressed from the copper-induced CUP1 promoter on a low-copy vector. D, quantification of 35S-labeled Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA from C to show the decay curves. E, comparison of protein synthesis in WT and srp1–49 strains. Aliquots of cells were withdrawn at different time points after addition of [35S]Met/Cys and used to prepare extracts. The incorporation of 35S into polypeptides was measured by TCA precipitation assay. Shown are the results of three independent experiments. F, pulse-chase analysis was performed as in A, with the pulse labeling time shortened to 1 min, followed by a chase for 0 and 5 min. G, quantification of 35S-labeled Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA from F.

We suspected that Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA could be degraded during pulse labeling and that the cotranslational degradation of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA could be impaired in srp1–49, resulting in the zero time effect (e.g. more protein products are detected at time 0). To test this possibility, we shortened the pulse labeling time to 1 min. This experimental design was on the basis of the observation that the average rate of translation in eukaryotic cells is 2–10 residues/s (42). Assuming a rate of 6 residues/s in S. cerevisiae, the complete synthesis of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA containing more than 500 residues needs at least 80 s. Therefore, the decline of 35S-labeled Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA shortly after 1-min pulse labeling (in early chase) is largely caused by cotranslational degradation. We found that the degradation of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA was substantially slower in YXY470 than in YXY468 during a 5-min chase period following 1-min pulse labeling (Fig. 2, F and G). Approximately 70% Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA was degraded in YXY468, whereas less than 30% was degraded in YXY470. The Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA level at zero time was relatively higher (∼15%) in YXY470 than in YXY468, indicating that the degradation readily occurs during the 1-min pulse labeling. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Srp1 is required for cotranslational degradation of Rpn4Δ211–229-3HA.

A Role of Srp1 in Global Cotranslational Protein Degradation

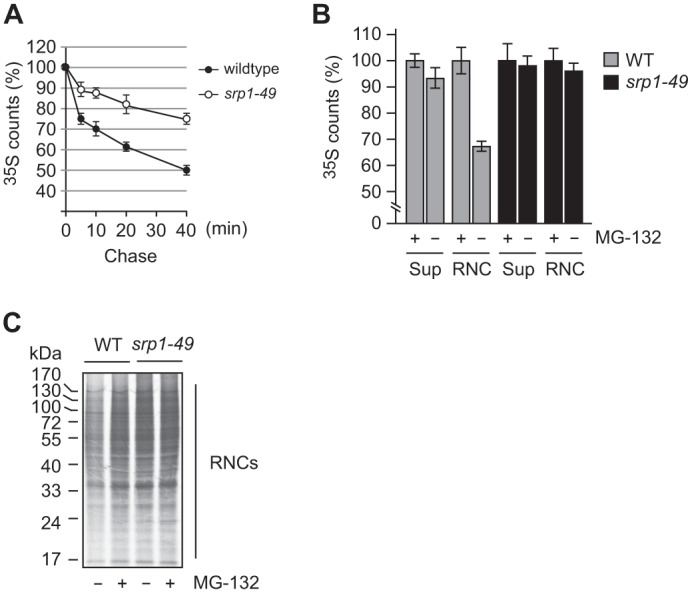

We next examined whether Srp1 plays a broad role in cotranslational protein degradation. We first compared the bulk degradation of newly synthesized proteins in srp1–49 and its WT counterpart. Cells were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 1 min, followed by a chase for up to 40 min in the presence of CHX and cold Met/Cys. Cells were harvested at different intervals, and the remaining 35S-labeled polypeptides were measured by TCA precipitation assay. As shown in Fig. 3A, the degradation of newly made proteins was substantially slower in srp1–49 than in the WT strain. This result suggests that Srp1 is involved in global cotranslational protein degradation. Of note, the outcome of the pulse-chase analysis is the sum of degradation of nascent polypeptides being synthesized on the ribosome; by definition, the bona fide cotranslational degradation and the completed, newly made proteins already released from the ribosome. To further assess the role of Srp1 in cotranslational protein degradation, we wanted to quantify the degradation of nascent polypeptides emerging from the ribosome during pulse labeling in WT and srp1–49 cells. To this end, we deleted the PDR5 gene from the WT and srp1–49 strains to increase the permeability of proteasome inhibitor MG132 so that we could use MG132 to gauge proteasome-dependent cotranslational degradation. MG132, controlled by DMSO, was added to exponentially growing cell cultures to shut down the proteasome activity 10 min before pulse labeling with [35S]Met/Cys. It has been shown that the addition of MG132 shortly prior to pulse labeling does not affect labeling efficiency or translation rates (19). After a short (1-min) pulse labeling, cells were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cell lysates were prepared in the presence of CHX and cold Met/Cys. RNCs were separated from the supernatant by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion. 35S-labeled proteins of the RNCs were quantified by TCA precipitation assay. Degradation of ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides was reflected by the difference in 35S counts of RNCs in the presence and absence of MG132. Approximately 33% of total ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides were degraded in the WT strain but only ∼4% in srp1–49 (Fig. 3B). Impaired degradation of ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides in srp1–49 was also illustrated by autoradiography following SDS-PAGE of the 35S-labeled RNCs (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that Srp1 plays a broad role in cotranslational protein degradation. By measuring the 35S counts of the supernatants in the presence or absence of MG132, we found that the degradation of nascent polypeptides already released from the ribosome was also impaired, to a lesser extent, in srp1–49. Approximately 7% of newly released nascent polypeptides were degraded in the WT strain but only ∼ 1.5% in srp1–49 (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Cotranslational protein degradation is impaired in srp1–49. A, bulk degradation of newly synthesized proteins is slower in srp1–49 than in WT cells. Cells were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 1 min and chased for 0, 5, 10, 20, and 40 min. Remaining 35S-labeled proteins were measured by TCA precipitation assay. B, measurement of cotranslational protein degradation. WT and srp1–49 cells deleted of PDR5 were treated with MG132 or DMSO for 10 min prior to 1-min pulse labeling with [35S]Met/Cys. RNCs were separated from the supernatant (Sup) by ultracentrifugation through a 25% sucrose cushion. 35S-labeled proteins in the RNC and supernatant fractions were quantified by TCA precipitation assay. Data are mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, autoradiogram of RNCs following SDS-PAGE. Equal amounts of RNCs prepared as in B were applied to SDS-PAGE.

Srp1 Binds Ribosome-bound Nascent Chains

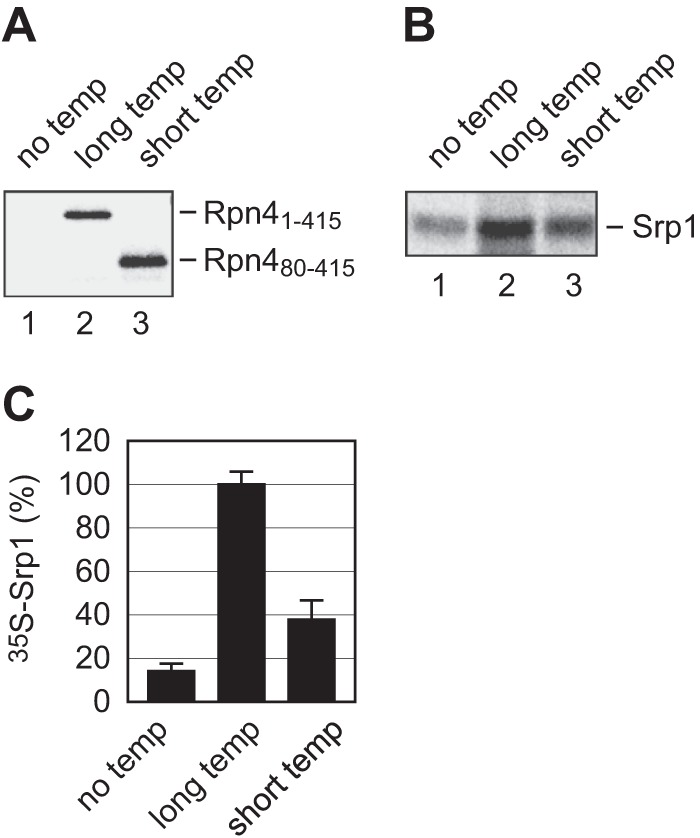

To examine whether Srp1 binds nascent chains emerging from the ribosome, we first used Rpn4 as a model molecule to test this possibility. In addition, we wanted to examine whether the N-terminal sequence of Rpn4 is targeted by Srp1. The TnT coupled transcription/translation system was applied to produce ribosome-bound Rpn4 polypeptides. To overcome the constraint of analysis of the interaction between nascent chains and their binding proteins, i.e. the heterogeneous nature of the elongating nascent chains, we took advantage of the fact that the translation products of mRNAs lacking a stop codon remain ribosome-bound as peptidyl-tRNA and are homogeneous in length (43). Specifically, we digested the DNA templates encoding full-length Rpn4 (“long”) or Rpn4Δ1–79 (“short”) with the restriction enzyme EcoRI, which has a unique cutting site at codon 415. Using the EcoRI-cut DNA templates, we produced homogenous ribosome-bound Rpn41–415 and Rpn480–415 nascent polypeptides (Fig. 4A). No ribosome-bound nascent chains were generated from a control reaction without input of a DNA template. To assay the binding of Srp1 to ribosome-bound nascent chains, RNCs containing non-labeled Rpn41–415 or Rpn480–415 and unloaded ribosomes were separated from other reticulocyte proteins by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion. The recovered RNCs and ribosomes were incubated with an equal amount of 35S-labeled Srp1. The mixtures were then layered on a sucrose cushion and subjected to ultracentrifugation to remove free [35S]Srp1. RNC- or ribosome-bound [35S]Srp1 was eluted by sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and quantified by a PhosphorImager. There was much more Srp1 associated with the RNCs than with the unloaded ribosomes, and Srp1 had a higher affinity for RNCs bearing Rpn41–415 than Rpn480–415 (Fig. 4, B and C). These results indicate that Srp1 binds the ribosome-bound Rpn4 nascent chains and that the N-terminal domain of Rpn4 is important for recognition by Srp1. Note that a small but noticeable amount of Srp1 was associated with the ribosomes bearing no nascent chains. This observation suggests that Srp1 may also bind to the ribosome.

FIGURE 4.

The binding of Srp1 to ribosome-bound Rpn4 nascent chains. A, the production of ribosome-bound Rpn41–415 and Rpn480–415 polypeptides. Stop codon-less DNA templates encoding Rpn41–415 (long temp) and Rpn480–415 (short temp) were applied to the TnT coupled transcription/translation system supplemented with [35S]Met/Cys. A reaction without template DNA (no temp) was used as a control. After the reactions were terminated, the mixtures were ultracentrifuged through a 0.5 m sucrose cushion. Pelleted RNCs containing 35S-labeled Rpn41–415 or Rpn480–415 and unloaded ribosomes were dissolved in sample buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE. B, measurement of the binding of Srp1 to ribosome-bound Rpn4 nascent chains. 35S-labeled Srp1 was incubated with non-labeled RNCs bearing Rpn41–415 (lane 2), Rpn480–415 (lane 3), or unloaded ribosomes (lane 1). Free [35S]Srp1 was removed by ultracentrifugation. Retained [35S]Srp1 was resolved by SDS-PAGE and quantified by a PhosphorImager. C, quantification of the results from B. Data are mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. The amount of Srp1 binding to Rpn41–415 RNC is set at 100%.

We went on to examine the binding of Srp1 to general nascent chains emerging from the ribosome using a method outlined in Fig. 5A. In addition, we wanted to test whether this activity is impaired by the E145K mutation in srp1–49. Polysomes were collected from exponentially growing WT and srp1–49 cells by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion. The nascent polypeptides being translated on the polysomes were labeled with puromycin, which forms a covalent bond with the carboxyl terminus of nascent polypeptides and blocks further translation (44). To stabilize the interaction between nascent polypeptides and Srp1, the thiol-cleavable cross-linker DTSSP was added to the reaction after puromycin labeling. Anti-puromycin immunoblotting analysis confirmed that the nascent polypeptides were labeled with puromycin and that DTSSP was able to cross-link the nascent polypeptides (Fig. 5B). The puromycin-labeled nascent polypeptides appeared as a high molecular weight smear under non-reducing conditions but returned to regular size bands after being treated with DTT. The association of endogenous Srp1 (and Srp1E145K) with RNCs was also demonstrated by cross-linking and anti-Srp1 immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 5C). The detection of cross-linked Srp1 by immunoblotting under nonreducing conditions was somewhat inefficient. To illustrate the binding of Srp1 to nascent polypeptides, we disassembled the RNCs by heating the reaction mixture at 95 °C in the presence of 1% SDS. The samples were then diluted to reduce the SDS concentration and subjected to IP with anti-Srp1 and anti-puromycin antibodies, respectively. The precipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and detected by immunoblotting analysis with anti-puromycin or anti-Srp1 antibody. We found that Srp1 was precipitated by the anti-puromycin antibody (Fig. 5D, lanes 3 and 6). Vice versa, puromycin-labeled nascent polypeptides were brought down by the anti-Srp1 antibody (Fig. 5E, lanes 3 and 6). These results indicated that Srp1 was indeed cross-linked to the nascent polypeptides. This analysis also showed that Srp1E145K had a similar affinity for ribosome-bound nascent chains as for wild-type Srp1.

FIGURE 5.

Srp1 binds ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides. A, flow chart of experiments to show the binding of Srp1 to ribosome-bound nascent chains. Puro, puromycin. B, immunoblot (IB) analysis to show puromycin labeling and cross-linking of nascent chains. RNCs isolated from WT and srp1–49 cells were incubated with puromycin prior to the addition of the cross-linker DTSSP. The reaction mixture was heated at 95 °C for 5 min in sample buffer with or without DTT, followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with an anti-puromycin antibody. Puro-NCs, puromycin-labeled nascent chains; M, molecular markers. C, endogenous Srp1 and Srp1E145K are physically associated with RNCs. The same samples as in B were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-Srp1 antibody. D and E, Srp1 binds ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides. Puromycin-labeled, DTSSP-cross-linked RNCs were disassembled by incubation with 1% SDS at 95 °C for 5 min. The samples were then diluted to reduce the SDS concentration and subjected to IP with anti-puromycin (D) or anti-Srp1 (E) antibody. The precipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Srp1 (D) or anti-puromycin (E) antibody.

Coupling of Proteasomes to Ribosome-bound Nascent Chains via Srp1 and Sts1

It is of interest to note that, although cotranslational protein degradation is impaired in srp1–49, Srp1E145K binds ribosome-bound nascent chains as efficiently as wild-type Srp1 (Fig. 5). These observations suggest that targeting ribosome-bound nascent chains is probably not the only function of Srp1 in cotranslational degradation. We speculated that Srp1 might be involved in coupling proteasomes to ribosome-bound nascent chains and that this critical activity for cotranslational degradation might be impaired in srp1–49. To test this hypothesis, cell extracts prepared from WT and srp1–49 strains were fractionated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation. Fractions were collected from the top to the bottom of the gradient. The bottom fractions containing polysomes or translating ribosomes were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against proteasome subunit Rpn12, ribosome component L3, and Srp1 (Fig. 6, A–C). Although comparable amounts of Srp1 and Srp1E145K were associated with the polysomes, more than 2-fold proteasomes cosedimented with polysomes in the WT strain than in srp1–49. Similar results were obtained when an anti-20 S proteasome antibody was used to measure the cosedimented proteasomes (data not shown). Note that the proteasome abundance was slightly higher in srp1–49 than in WT cells, likely because of the relatively higher steady-state level of Rpn4 in srp1–49 (data not shown). Thus, Srp1 is involved in the coupling of proteasomes to ribosome-bound nascent chains, and this activity is compromised in Srp1E145K.

FIGURE 6.

Srp1 and Sts1 couple proteasomes to polysomes. A, polysome profiles. Cell extracts of various strains were run in parallel on 10–50% sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation. Polysome profiles were determined by plotting 254-nm absorbance against fractions collected from the top to the bottom of the gradient. B, cosedimentation of proteasomes with polysomes in WT, srp1–49, and sts1–2 cells. Fractions containing polysomes were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Rpn12, L3, and Srp1. C, quantification of the data from A to compare the ratio of Rpn12 versus L3 in different strains. D, analysis of the binding of Sts1 to Srp1 and Srp1E145K. N-terminally His-tagged Sts1 expressed in and purified from E. coli was applied to pulldown assays with GST-Srp1 (lane 2), GST-Srp1E145K (lane 3), or GST (lane 4). Retained His-Sts1 was detected by immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody. E, Sts1 links Srp1 to the proteasome. Purified yeast 26 S proteasomes carrying a His-tagged Pre1 subunit were incubated with GST, GST-Srp1, or GST-Srp1E145K in the absence (lanes 1–3) or presence (lanes 5–7) of His-Sts1. Pre1-His and His-Sts1 were detected by immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody.

It has been suggested that the interaction between Srp1 and the proteasome may be mediated or facilitated by Sts1, a multicopy suppressor of srp1–49 (45, 46). We found that the cosedimentation of proteasomes with polysomes significantly decreased in the sts1–2 mutant (Fig. 6, A–C, and data not shown). Using GST pulldown assays, we showed that Sts1 directly interacted with Srp1 (Fig. 6D). Moreover, GST-Srp1 pulled down purified proteasomes in the presence but not in the absence of Sts1 (Fig. 6E, compare lanes 2 and 6). These results indicate that Sts1 links the proteasome to Srp1. It is of interest to note that Sts1 had much lower affinity for Srp1E145K than Srp1 (Fig. 6D, compare lanes 2 and 3). In addition, proteasomes were only weakly retained by GST-Srp1E145K, even in the presence of Sts1 (Fig. 6E, lane 7). These observations explain why the coupling of proteasomes to polysomes is less efficient in srp1–49. Taken together, these results show that Srp1 and Sts1 recruit proteasomes to ribosome-bound nascent chains.

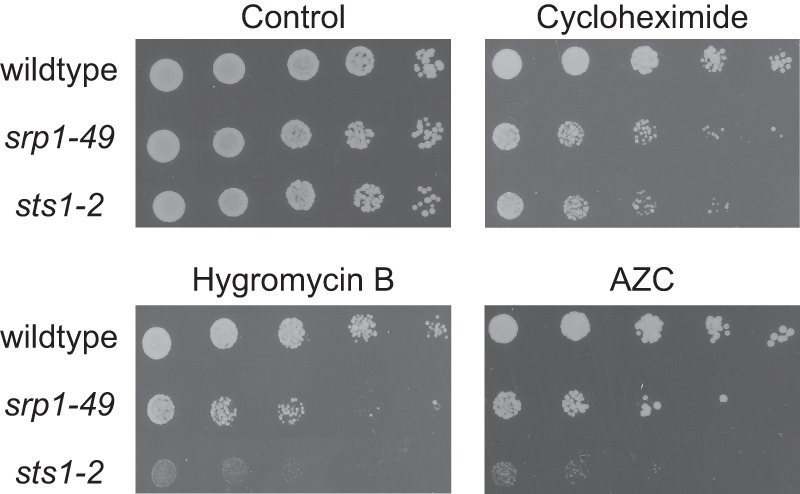

srp1–49 and sts1–2 Are Hypersensitive to Conditions That Increase Protein Misfolding

We have shown that cotranslational protein degradation is defective in srp1–49 (Figs. 3 and 4). Using a short pulse labeling chase assay, we demonstrated that the bulk degradation of newly synthesized proteins was significantly slower in sts1–2 than in the WT strain (data not shown). This result suggests that Sts1 also plays a general role in cotranslational protein degradation. We next examined whether srp1–49 and sts1–2 are hypersensitive to conditions that enhance the production of misfolded nascent polypeptides. Specifically, we compared the sensitivity of WT, srp1–49, and sts1–2 cells to CHX, hygromycin B, and L-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid. CHX and hygromycin B are translation inhibitors that promote the premature release of nascent chains. L-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid is a proline analog that induces protein misfolding after incorporation into nascent polypeptides. Indeed, we found that the srp1–49 and sts1–2 mutants were much more sensitive to these stressors than the WT strain (Fig. 7). These results underscore the physiological function of Srp1 and Sts1 in cotranslational degradation of misfolded nascent polypeptides.

FIGURE 7.

srp1–49 and sts1–2 are hypersensitive to stressors inducing protein misfolding. Five-fold serial dilutions of exponentially growing WT, srp1–49, and sts1–2 cell cultures were spotted on SD plates supplemented with essential amino acids plus CHX (0. 5 μm), hygromycin B (1 mm), or L-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (AZC) (0.1 mm) and incubated at 30 °C for 3 days.

DISCUSSION

Cotranslational protein degradation plays a critical role in preventing the accumulation of misfolded, potentially toxic proteins in the cell. However, the molecular details of cotranslational protein degradation remain poorly understood. One important unanswered question is how the proteasome targets ribosome-bound nascent chains that are destined for cotranslational degradation. It has been suggested that ubiquitylation of nascent polypeptides serves as a targeting signal for the proteasome (8, 14–16). This suggestion is supported by the identification of ribosome-bound ubiquitin ligases and the detection of ubiquitylation of nascent polypeptides (14–18). In addition, several Ub-binding proteins, including translation elongation factor 1A (eEF1A) and Cdc48, are associated with the ribosome and involved in cotranslational degradation of aberrant nascent polypeptides (6, 15, 47). Intriguingly, cotranslational ubiquitylation occurs at a rather low level. In budding yeast cells, ∼1–6% of nascent polypeptides are cotranslationally ubiquitylated (19, 20). This number is apparently lower than the estimated percentage of yeast proteins likely undergoing cotranslational degradation (14). In fact, our quantitative analysis reveals that about one-third of nascent polypeptides are cotranslationally degraded in yeast cells. These results argue that a substantial fraction of nascent polypeptides may be degraded cotranslationally by a Ub-independent pathway. In this study, we demonstrate that cotranslational degradation of Rpn4 can occur without prior ubiquitylation. Our attempts to elucidate the underlying mechanism led to the unveiling of a novel function for Srp1 and Sts1 in cotranslational protein degradation.

Previous studies have firmly established Srp1 as a nuclear import factor whose cargoes include the proteasome (36–41, 48, 49). An early report by Tabb et al. (46) implied the involvement of Srp1 and Sts1 in protein degradation. Although the authors suggested that the function of Srp1 in protein degradation may be separate from its role in nuclear import, the mechanism was not explored. In contrast, Chen et al. (45) proposed recently that the defect of protein degradation in srp1–49 and sts1–2 was caused by a reduced nuclear import of proteasomes. The proposed mechanism may be applicable to nuclear proteins, but it cannot explain impaired degradation of cytosolic substrates such as Ub-Pro-β-gal and R-β-gal (46, 50). Nevertheless, neither of these two studies revealed the role of Srp1 and Sts1 in cotranslational protein degradation, perhaps because of overlook of the zero time effect in pulse-chase analysis, i.e. the degradation of newly synthesized polypeptides during pulse labeling. In this study, we demonstrate that Srp1 binds nascent chains emerging from the ribosome and that cotranslational protein degradation is severely impaired in srp1–49 (Figs. 2–5). In addition, we show that the association of proteasomes to polysomes is markedly reduced in srp1–49 and sts1–2 (Fig. 6). On the basis of these and other data, we propose a model whereby Srp1 and Sts1 cooperate to recruit proteasomes to polysomes to degrade the nascent polypeptides destined for cotranslational degradation. Specifically, Srp1 targets the susceptible nascent polypeptides, whereas Sts1 serves as an adaptor to link the proteasome to Srp1. This model provides a plausible mechanism for cotranslational degradation of Ub-independent substrates, exemplified by the ability of Srp1 to target non-ubiquitylated Rpn4 nascent chains. Of note, Srp1 appears to bind the ribosome as well, although with lower affinity than the nascent chains attached on the ribosome (Fig. 4). This observation suggests that Srp1 may recruit proteasomes to RNCs via interaction with the nascent chains and the ribosome. These two binding activities should not be mutually exclusive but, likely, cooperate with each other to facilitate the delivery of nascent chains to the proteasome. For instance, the dual binding activity may prolong the association of proteasomes with RNCs, allowing enough time for proteasomes to engulf the nascent chains. This may be particularly important for Ub-independent substrates because they probably have a lower affinity for the proteasome than Ub chains.

It is worthy of note that the N-terminal sequence of Rpn4 is critical for recognition by Srp1 (Fig. 4), suggesting that Srp1 has different affinities for different nascent chains. In other words, Srp1 may target specific nascent chains for cotranslational degradation. The specificity is perhaps determined by the structural features of the N-terminal motif of a nascent chain. For instance, a segment of amino acids that cannot fold properly or quickly enough after emerging from the ribosome may be recognized by Srp1. Interestingly, the N-terminal region of Rpn4 indeed harbors a disordered domain (28). It will be of great interest to decipher the determinant or determinants that mark nascent polypeptides for cotranslational degradation. This remains a challenging task because very few protein species have been clearly identified that undergo cotranslational degradation. Given that Srp1 play a broad role in cotranslational protein degradation, the identification of Srp1-bound nascent chains through global proteomic analysis or ribosome profiling will provide a snapshot of the cellular proteins that are subject to cotranslational degradation.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Enenkel, G. Fink, K. Kuchler, K. Madura, M. Nomura, D. Skowyra, J. Warner, and J. Woolford for antibodies, yeast strains, and plasmids.

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0816974 and by a fund from the Office of the Vice President for Research at Wayne State University (to Y. X.).

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- RNC

- ribosome-nascent chain complex

- DTSSP

- 3,3′-dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidyl propionate)

- ura

- uracil

- ade

- adenine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hartl F. U., Bracher A., Hayer-Hartl M. (2011) Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475, 324–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pechmann S., Willmund F., Frydman J. (2013) The ribosome as a hub for protein quality control. Mol. Cell 49, 411–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kramer G., Boehringer D., Ban N., Bukau B. (2009) The ribosome as a platform for co-translational processing, folding and targeting of newly synthesized proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 589–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Preissler S., Deuerling E. (2012) Ribosome-associated chaperones as key players in proteostasis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 274–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tyedmers J., Mogk A., Bukau B. (2010) Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 777–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brandman O., Stewart-Ornstein J., Wong D., Larson A., Williams C. C., Li G.-W., Zhou S., King D., Shen P. S., Weibezahn J., Dunn J. G., Rouskin S., Inada T., Frost A., Weissman J. S. (2012) A ribosome-bound quality control complex triggers degradation of nascent peptides and signals translation stress. Cell 151, 1042–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Willmund F., del Alamo M., Pechmann S., Chen T., Albanèse V., Dammer E. B., Peng J., Frydman J. (2013) The cotranslational function of ribosome-associated Hsp70 in eukaryotic protein homeostasis. Cell 152, 196–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schubert U., Antón L. C., Gibbs J., Norbury C. C., Yewdell J. W., Bennink J. R. (2000) Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteasomes. Nature 404, 770–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reits E. A., Vos J. C., Grommé M., Neefjes J. (2000) The major substrates for TAP in vivo are derived from newly synthesized proteins. Nature 404, 774–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rock K. L., York I. A., Saric T., Goldberg A. L. (2002) Protein degradation and the generation of MHC class I-presented peptides. Adv. Immunol. 80, 1–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yewdell J. W., Antón L. C., Bennink J. R. (1996) Defective ribosomal products (DRiPs). A major source of antigenic peptides for MHC class I molecules? J. Immunol. 157, 1823–1826 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Princiotta M. F., Finzi D., Qian S.-B., Gibbs J., Schuchmann S., Buttgereit F., Bennink J. R., Yewdell J. W. (2003) Quantitating protein synthesis, degradation, and endogenous antigen processing. Immunity 18, 343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yewdell J. W., Nicchitta C. V. (2006) The DRiP hypothesis decennial. Support, controversy, refinement and extension. Trends Immunol. 27, 368–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turner G. C., Varshavsky A. (2000) Detection and measuring cotranslational protein degradation in vivo. Science 289, 2117–2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chuang S. M., Chen L., Lambertson D., Anand M., Kinzy T. G., Madura K. (2005) Proteasome-mediated degradation of cotranslationally damaged proteins involves translation elongation factor 1A. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 403–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sato S., Ward C. L., Kopito R. (1998) Cotranslational ubiquitination of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 7189–7192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bengtson M. H., Joazeiro C. A. (2010) Role of a ribosome-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase in protein quality control. Nature 467, 470–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dimitrova L. N., Kuroha K., Tatematsu T., Inada T. (2009) Nascent peptide-dependent translation arrest leads to Not4p-mediated protein degradation by the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10343–10352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duttler S., Pechmann S., Frydman J. (2013) Principles of cotranslational ubiquitination and quality control at the ribosome. Mol. Cell 50, 379–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang F., Durfee L. A., Huibregtse J. M. (2013) A cotranslational ubiquitination pathway for quality control of misfolded proteins. Mol. Cell 50, 368–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mannhaupt G., Schnall R., Karpov V., Vetter I., Feldmann H. (1999) Rpn4p acts as a transcription factor by binding to PACE, a nonamer box found upstream of 26S proteasomal and other genes in yeast. FEBS Lett. 450, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xie Y., Varshavsky A. (2001) RPN4 is a ligand, substrate, and transcriptional regulator of the 26 S proteasome. A negative feedback circuit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3056–3061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ju D., Wang L., Mao X., Xie Y. (2004) Homeostatic regulation of the proteasome via an Rpn4-dependent feedback circuit. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321, 51–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xie Y. (2010) Structure, assembly and homeostatic regulation of the 26 S proteasome. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 308–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ju D., Xie Y. (2004) Proteasomal degradation of RPN4 via two distinct mechanisms. Ubiquitin-dependent and -independent. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23851–23854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ju D., Wang X., Xu H., Xie Y. (2008) Genome-wide analysis identifies MYND-domain protein Mub1 as an essential factor for Rpn4. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 1404–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang L., Mao X., Ju D., Xie Y. (2004) Rpn4 is a physiological substrate of the Ubr2 ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55218–55223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ha S.-W., Ju D., Xie Y. (2012) The N-terminal domain of Rpn4 serves as a portable ubiquitin-independent degron and is recognized by specific 19S RP subunits. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 226–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ju D., Xie Y. (2006) Identification of the preferential ubiquitination site and ubiquitin-dependent degradation signal of Rpn4. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10657–10662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ju D., Xu H., Wang X., Xie Y. (2007) Ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Rpn4 is controlled by a phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitylation signal. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773, 1672–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson E. S., Ma P. C., Ota I. M., Varshavsky A. (1995) A proteolytic pathway that recognizes ubiquitin as a degradation signal. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17442–17456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang X., Xu H., Ha S.-W., Ju D., Xie Y. (2010) Proteasomal degradation of Rpn4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is critical for cell viability under stressed conditions. Genetics 184, 335–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mahé Y., Lemoine Y., Kuchler K. (1996) The ATP binding cassette transporters Pdr5 and Snq2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae can mediate transport of steroids in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 25167–25172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. James P., Halladay J., Craig E. A. (1996) Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144, 1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yano R., Oakes M., Yamaghishi M., Dodd J. A., Nomura M. (1992) Cloning and characterization of SRP1, a suppressor of temperature-sensitive RNA polymerase I mutations, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 5640–5651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yano R., Oakes M. L., Tabb M. M., Nomura M. (1994) Yeast srp1 has homology to armadillo/plakoglobin/β-catenin and participates in apparently multiple nuclear functions including the maintenance of the nucleolar structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 6880–6884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Enenkel C., Blobel G., Rexach M. (1995) Identification of a yeast karyopherin heterodimer that targets import substrate to mammalian nuclear pore complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16499–16502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loeb J. D., Schlenstedt G., Pellman D., Kornitzer D., Silver P. A., Fink G. R. (1995) The yeast nuclear import receptor is required for mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7647–7651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Enenkel C., Schülke N., Blobel G. (1996) Expression in yeast of binding regions of karyopherin α and β inhibits nuclear import and cell growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12986–12991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Görlich D., Vogel F., Mills A. D., Hartmann E., Laskey R. A. (1995) Distinct functions for the two importin subunits in nuclear import. Nature 377, 246–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Radu A., Blobel G., Moore M. S. (1995) Identification of a protein complex that is required for nuclear protein import and mediates docking of import substrate to distinct nucleoporins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 1769–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Spirin A. S. (1986) Ribosome Structure and Protein Biosynthesis. Cummings, Menlo Park, CA [Google Scholar]

- 43. Krieg U. C., Johnson A. E., Walter P. (1989) Protein translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Identification by photocross-linking of a 39-kD integral membrane glycoprotein as part of a putative translocation tunnel. J. Cell Biol. 109, 2033–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pestka S. (1971) Inhibitors of ribosome functions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 25, 487–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen L., Romero L., Chuang S. M., Tournier V., Joshi K. K., Lee J. A., Kovvali G., Madura K. (2011) Sts1 plays a key role in targeting proteasomes to the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 3104–3118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tabb M. M., Tongaonkar P., Vu L., Nomura M. (2000) Evidence for separable functions of Srp1p, the yeast homolog of importin α (Karyopherin α). Role for Srp1p and Sts1p in protein degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 6062–6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Verma R., Oania R. S., Kolawa N. J., Deshaies R. J. (2013) Cdc48/p97 promotes degradation of aberrant nascent polypeptides bound to the ribosome. Elife 2, e00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lehmann A., Janek K., Braun B., Kloetzel P. M., Enenkel C. (2002) 20 S proteasomes are imported as precursor complexes into the nucleus of yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 317, 401–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wendler P., Lehmann A., Janek K., Baumgart S., Enenkel C. (2004) The bipartite nuclear localization sequence of Rpn2 is required for nuclear import of proteasomal base complexes via karyopherin αβ and proteasome functions. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37751–37762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Romero-Perez L., Chen L., Lambertson D., Madura K. (2007) Sts1 can overcome the loss of Rad23 and Rpn10 and represents a novel regulator of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35574–35582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]