ABSTRACT

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is causatively linked to two B cell lymphoproliferative disorders, multicentric Castleman's disease and primary effusion lymphoma. Latently infected B cells are a major KSHV reservoir, and virus activation from tonsillar B cells can result in salivary shedding and virus transmission. Paradoxically, human B cells (primary and continuous) are notoriously refractory to infection, thus posing a major obstacle to the study of KSHV in this cell type. By performing a strategic search of human B cell lymphoma lines, we found that MC116 cells were efficiently infected by cell-free KSHV. Upon exposure to recombinant KSHV.219, enhanced green fluorescent protein reporter expression was detected in 17 to 20% of MC116 cells. Latent-phase transcription and protein synthesis were detected by reverse transcription-PCR and detection of latency-associated nuclear antigen expression, respectively, in cell lysates and individual cells. Selection based on the puromycin resistance gene in KSHV.219 yielded cultures with all cells infected. After repeated passaging of the selected KSHV-infected cells without puromycin, latent KSHV was maintained in a small fraction of cells. Infected MC116 cells could be induced into lytic phase with histone deacetylase inhibitors, as is known for latently infected non-B cell lines, and also selectively by the B cell-specific pathway involving B cell receptor cross-linking. Lytic-phase transition was documented by red fluorescent protein reporter expression, late structural glycoprotein (K8.1A, gH) detection, and infectious KSHV production. MC116 cells were CD27−/CD10+, characteristic of transitional B cells. These findings represent an important step in the establishment of an efficient continuous B cell line model to study the biologically relevant steps of KSHV infection.

IMPORTANCE

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV; human herpesvirus 8) is a human gammaherpesvirus (1–3) initially identified in 1994 by representational differential analysis of DNA from AIDS-associated KS tissues (4). In addition to KS (5–7), which arises from endothelium, this oncovirus is causatively linked to two B cell lymphoproliferative disorders often associated with HIV infection: primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and the plasmablastic variant of multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) (8, 9). Detection of KSHV in tissues parallels the specific pathology; i.e., in KS nodules, the virus is found in the endothelium-derived spindle cells, whereas in PEL and MCD, it is detected in B cells (10). Consistent with its etiologic association with B cell pathologies, early studies demonstrated that development of KS is predicted by detection of KSHV in peripheral blood (11), where the virus is found predominantly in the B lymphocyte population (12, 13).

PEL-derived B cell lines have figured prominently in the study of KSHV in vitro (14). Indeed, such cells provided the first culture systems for analyzing the virus, enabling the demonstration that latently infected PEL cell lines could be chemically induced to produce KSHV virions (15, 16). Infection could be transmitted to cord blood-derived B lymphocytes but not to the corresponding B cell-depleted mononuclear cells, thus establishing KSHV as a lymphotropic virus (15). Sequence analysis of the KSHV genome confirmed its phylogenetic classification with the lymphotropic gammaherpesviruses (17). Subsequent studies have demonstrated in vitro KSHV infection of primary B lymphocytes obtained from various sources, including peripheral blood (18) and tonsillar tissue (18–21). Infected B cells in the latter site assume particular significance, in view of detection of the virus in saliva, where frequent intermittent shedding occurs even in asymptomatic individuals (22–26); indeed, saliva is believed to be a major route of KSHV transmission (27). Thus, as for other gammaherpesviruses (28), B cells are major reservoirs for KSHV infection in both the latent and lytic phases.

Paradoxically, while KSHV can readily establish latent infection in several irrelevant cells, such as human (e.g., 293, HeLa) and African green monkey (e.g., CV-1, Vero) adherent kidney epithelial cell lines (29–31), human immortalized B lymphoblastoid cell lines are notoriously refractory to infection (30, 32, 33). The Louckes human B cell line was shown to be susceptible to KSHV virions produced from KS lesions but, oddly, not KSHV virions from PEL-derived cell lines (34). The failure of B lymphoblastoid cell lines to support infection by cell-free KSHV virions could be bypassed via transmission of cell-associated virus from a stably infected cell line (35). Thus, a culture system involving a human continuous B cell line that is permissive for infection with experimentally produced cell-free KSHV would be of great value in the study of the various steps of the viral infection cycle. This report describes our directed search for such a cell line, leading to the identification and characterization of the MC116 cell line as a model for KSHV infection and activation in human B lymphocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B cell lymphoma cell lines.

JM-1, MC116, Ramos, Reh, and SU-DHL-6 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and maintained under the recommended conditions. EJ-1 cells were a gift from K. Stephen Suh (Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ). Louckes cells were a gift from John Yates (Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY). BJAB, Louckes, and EJ-1 cells were maintained in RPMI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma, Atlanta, GA), glutamine (Quality Biologicals), and penicillin and streptomycin (Quality Biologicals). All cultures were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Virus propagation and titration.

KSHV infections were performed with KSHV recombinant strain KSHV.219 (rKSHV.219) (31) generated from iSLK.219 cells, which were propagated in the presence of puromycin and induced to produce cell-free KSHV as described previously (36). Briefly, 80% confluent iSLK.219 cells were induced with growth medium containing 1 mM sodium butyrate and 0.2 μg/ml doxycycline in the absence of puromycin. Virus was collected by harvesting the culture medium when 90% of cells no longer appeared to be adherent. Debris was pelleted and discarded twice, and passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride filter (Corning, Charlotte, NC) to remove cells and large debris. Virus was concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 1 h at 13,500 rpm in an SW28 rotor; the pellets were reconstituted with RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin at 1% of the original volume and stored at −80°C. The number of infectious units of virus was determined by titration on 293F cells by measurement of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and/or a Leica DM IRB fluorescence microscope. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo software (version 6.3; Tree Star). Fluorescent images were obtained using a SPOT insight digital camera and SPOT software (version 4.5.9.3). Images were processed in the Adobe Photoshop (version 8.0) program. 293F cells were maintained during propagation and infection in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Puromycin selection of uniformly infected cells.

Following exposure to rKSHV.219, infected B cell lymphoma cell lines were selected by propagation in puromycin-containing medium. Initially, 0.2 μg/ml of puromycin (Sigma) was used. For Reh and BJAB cells, the puromycin concentration was increased to 5 μg/ml after several weeks. For MC116 cells, the puromycin concentration was increased in increments up to 45 μg/ml. KSHV-positive cells were monitored by flow cytometry and/or fluorescence microscopy.

Induction of lytic phase.

To induce the lytic phase in chronically infected B cells, the indicated reagents were added to the growth medium. Induction of red fluorescent protein (RFP) was monitored daily via microscopy and determination of the production of infectious units of virus. Sodium butyrate (SB; Sigma), valproic acid (VPA; Sigma), and anti-human IgM Fc fragment-specific antibody (Fc5μ fragment specific; Jackson Laboratories) were added at the concentrations indicated below. Images were obtained on day 5 posttreatment. Images are representative of those from at least 3 experiments. For quantification of nascent virus production from induced MC116.219 cells, 4 ml of supernatant from cultures induced for 3 days was cleared, and virus was prepared via a previously reported protocol (37).

Immunodetection of viral protein.

Approximately 1 million cells (infected or controls) were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, diluted in SDS sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, and boiled for 10 min. Samples were cooled, and the debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min and discarded. Equal volumes of sample were added to a NuPAGE 4 to 12% bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies) for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Transfer to nitrocellulose was performed with an iBlot gel transfer system. To detect viral proteins, monoclonal antibody (MAb) LN53 (ABI Advanced Biotechnologies, Columbia, MD) recognizing an acid-rich epitope in the central repeat region of latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) was used as a primary antibody, and goat anti-rat antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used as a secondary antibody. Visualization was via chemiluminescent substrate (West Dura; Pierce, Philadelphia, PA) and exposure to Kodak X-ray film (Fisher, Pittsburg, PA).

Immunoconfocal microscopy.

Newly infected or infected and selected cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 4% phosphonoformic acid (PFA)–PBS for 10 min and then washed in PBS. For LANA staining, cells were permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min and washed 2 times prior to blocking. Cells were blocked in PBS containing 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min and stained in primary specific MAb or control MAb for 1 h at room temperature (for LANA, MAb LN53 [Advanced Biotechnologies]; for K8.1A, MAb 4C3 [67, 68]; for gH, MAb15 [69]; mouse IgG was used as a control [BD Pharmingen]). Cells were washed in PBS and probed with anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody conjugated to allophycocyanin (APC; BD Pharmingen) for 1 h. Samples were washed 3 times, pelleted, resuspended in 10 μl of PBS, and spread on microscope slides. Following a 1- to 2-min drying period at room temperature, samples were mounted using Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Life Technologies), coverslips were added, and the samples were dried overnight.

Real-time PCR.

For the quantitation of the relative KSHV genomic DNA copy number, real-time PCR of the LANA gene was performed as described previously (38). Reactions were performed using a Step One Plus real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems). A TaqMan probe to the LANA nucleic acid sequence was generated by Invitrogen (Life Technologies). For genomic copy number amplification and detection, Absolute quantitative PCR–carboxy-X-rhodamine master mix was used (Thermo Fisher, Atlanta, GA). A SuperScript III one-step reverse transcription-PCR system with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) was used to detect transcription of LANA mRNA. DNA and RNA were prepared using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit and an RNeasy Plus minikit, respectively (Qiagen), as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Phenotypic analysis of immunological and cytogenetic markers.

For detection of IgM and the κ or λ immunoglobulin light chain, the following antibodies were used: IgM-biotin (Invitrogen) detected with streptavidin-conjugated peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP; BD), κ-APC, λ (mouse IgG), and antimouse antibody conjugated to APC (BD). Samples were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). For glycoprotein analysis, MC116.219 cells were induced or cultured in the absence of inducing agent for 3 days, washed in PBS, and fixed in 4% PFA–PBS for 10 min and then washed 2 times in PBS containing 1% BSA. Cells were stained in primary antibody or the control for 1 h at room temperature (for K8.1A, MAb 4C3; for gH MAb15 control [BD Pharmingen]). Cells were washed in PBS and probed with anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody conjugated to APC (BD Pharmingen) for 1 h. Samples were washed 3 times and pelleted. For analysis of other phenotypic markers on MC116, MC116.219, and Ramos cells, cells were stained with the following antihuman MAbs: CD19-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD38-PerCP-Cy5.5, and CD23-phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7 (eBioscience); CD21-fluorescein isothiocyanate (Beckman Coulter); and CD10-APC, CD20-APC-H7, CD3-PE, and CD27-PE/CD27-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences). Samples were acquired on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

RESULTS

Directed search to identify a KSHV-susceptible B cell line(s).

The following criteria were employed in our directed search for a KSHV-susceptible human B cell line. (i) Only cells negative for both EBV and KSHV were examined. (ii) The possible relevance of IgM(λ) expression was considered in view of the findings that in vivo, KSHV-infected plasmablasts in the mantle zone of MCD patients are monotypic IgM(λ) (39), despite polyclonality (40), and in vitro, KSHV infection of human tonsillar explants is restricted to a subset of B cells expressing IgM(λ) (19). Therefore, we examined the IgM(λ)-expressing MC116 B cell line (41) as well as SU-DHL-6 B cells based on its originally reported IgM(λ) phenotype (42). (iii) The absence of somatic mutations in the rearranged immunoglobulin genes of KSHV-infected plasmablasts suggested that they arose at an early stage of B cell differentiation (40). Therefore, we included two early-stage lymphoma B cell lines, JM-1 (43) and Reh (44). (iv) We tested the Louckes cell line, given its reported susceptibility to KSHV from KS lesions (34). (v) Following generation of preliminary data, the EJ-1 cell line was chosen for analysis on the basis of the reported similarity of its gene expression profile to that of MC116 cells (45). For comparison, we examined two human B cell lines that are IgM positive, the Ramos (46) and BJAB (47) B cell lines, which are reportedly resistant or marginally sensitive to KSHV infection, respectively (30, 33). Table 1 summarizes the properties of the human B cell lines examined.

TABLE 1.

Summary of attributes for cell lines tested

| Cell line | Phenotype | Criteria for testing |

|---|---|---|

| BJAB | Burkitt's-like lymphoma | Control for minimal KSHV susceptibility |

| Ramos | Burkitt's lymphoma | Control for KSHV nonsusceptibility |

| JM-1 | Immunoblastic B cell lymphoma, pre-B lymphoblast | Pre-B cell |

| Reh | Acute lymphocytic leukemia (pre-B) | Pre-B cell |

| MC116 | Undifferentiated lymphoma | IgM(λ) |

| SU-DHL-6 | Large cell lymphoma, diffuse mixed histiocytic and lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular B cell lymphoma | IgM(λ) |

| EJ-1 | Large diffuse B cell lymphoma | Reportedly similar to MC116 in gene expression pattern |

| Louckes | Burkitt's B cell lymphoma | Susceptible to KSHV from KS lesions |

The MC116 human B cell line displays distinctive susceptibility to KSHV infection.

Infectivity was evaluated with recombinant virus rKSHV.219 (31) containing the EGFP reporter gene driven by the constitutive elongation factor 1α cellular promoter; EGFP expression requires only virus entry and transfer of the viral episome to the nucleus and occurs during both latent and lytic phases of infection. rKSHV.219 also contains the reporter gene encoding RFP under the control of the KSHV early-lytic-phase PAN promoter, which directs RFP expression only during lytic phase. Finally, the puromycin resistance gene, under the control of a constitutive promoter, enables positive selection of cells harboring the viral episome.

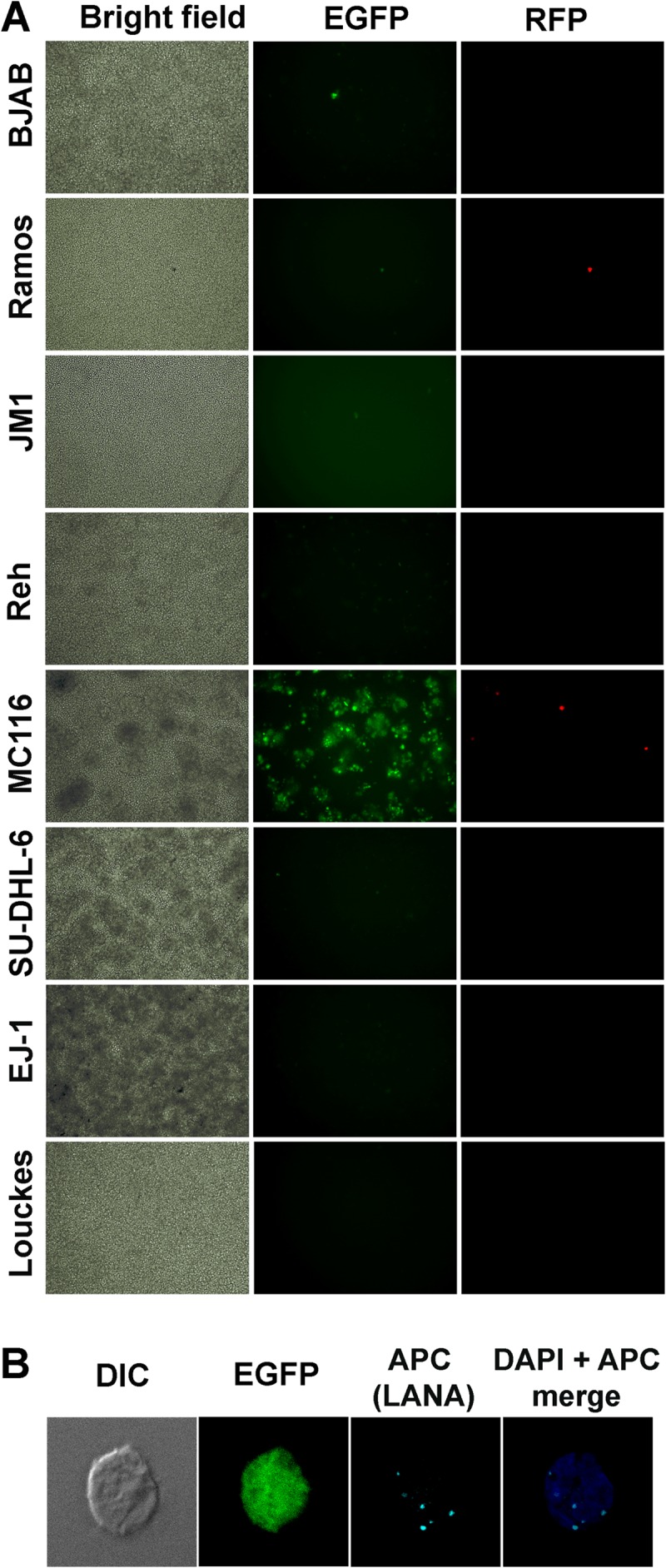

In Fig. 1A, candidate B cell lines were exposed to rKSHV.219 at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 (based on titration on 293F cells). Cells were monitored daily for fluorescence indicative of infection; the results at day 3 are shown. Bright-field images indicated that MC116, SU-DHL-6, and EJ-1 cells tended to form clusters (uninfected and KSHV exposed), whereas the other B cell lines mainly grew as individual cells. Little or no green fluorescence was observed in BJAB or Ramos control cells, consistent with previous findings of the minimal KSHV susceptibility of these and other human B cell lines (30, 32, 33). Lack of infection was also found for JM-1, Reh, SU-DHL-6, EJ-1, and Louckes cells, although the Reh cells variably showed very low level fluorescence (barely above the background). Thus, these cells displayed the KSHV-nonsusceptible phenotype typically observed for continuous B cell lines. The MC116 cells displayed a markedly contrasting profile; EGFP expression was clearly observed in a sizeable fraction (up to 20%) of cells exposed to rKSHV.219 (but not in the absence of the virus; not shown). Green fluorescence typically peaked at days 3 to 5. In subcloning experiments performed by either limiting dilution or fluorescence-activated cell sorting, no variations of the KSHV-susceptible fraction were observed in individual subclones (not shown). Additional studies are required to understand the mechanism underlying this restricted level of infection.

FIG 1.

Comparison of human B cell lines for susceptibility to KSHV infection. (A) The indicated cell lines were exposed to rKSHV.219 (MOI, 100, based on titration on 293F cells). Cultures were observed daily and photographed at day 3 postexposure. Bright-field microscopy, EGFP, and RFP images were observed. Magnification, ×10. (B) MC116 cells were exposed to rKSHV.219 as described for panel A. Cells were fixed and stained as indicated and then observed by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy or immunoconfocal microscopy. LANA was stained using anti-LANA MAb LN53, followed by APC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG MAb. Images were taken using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope at a 1-μm depth per slice. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Magnification, ×60.

Occasional RFP expression was observed over this time range, consistent with low-level spontaneous activation, as has been reported for PEL cells (16) as well as for other cell types infected with rKSHV.219 (31). Figure 1B demonstrates the expression of punctate LANA protein dots in the nucleus of an acutely infected (i.e., EFGP-positive) cell determined by immunoconfocal microscopy. Thus, under conditions of acute infection, a subfraction of MC116 cells becomes latently infected.

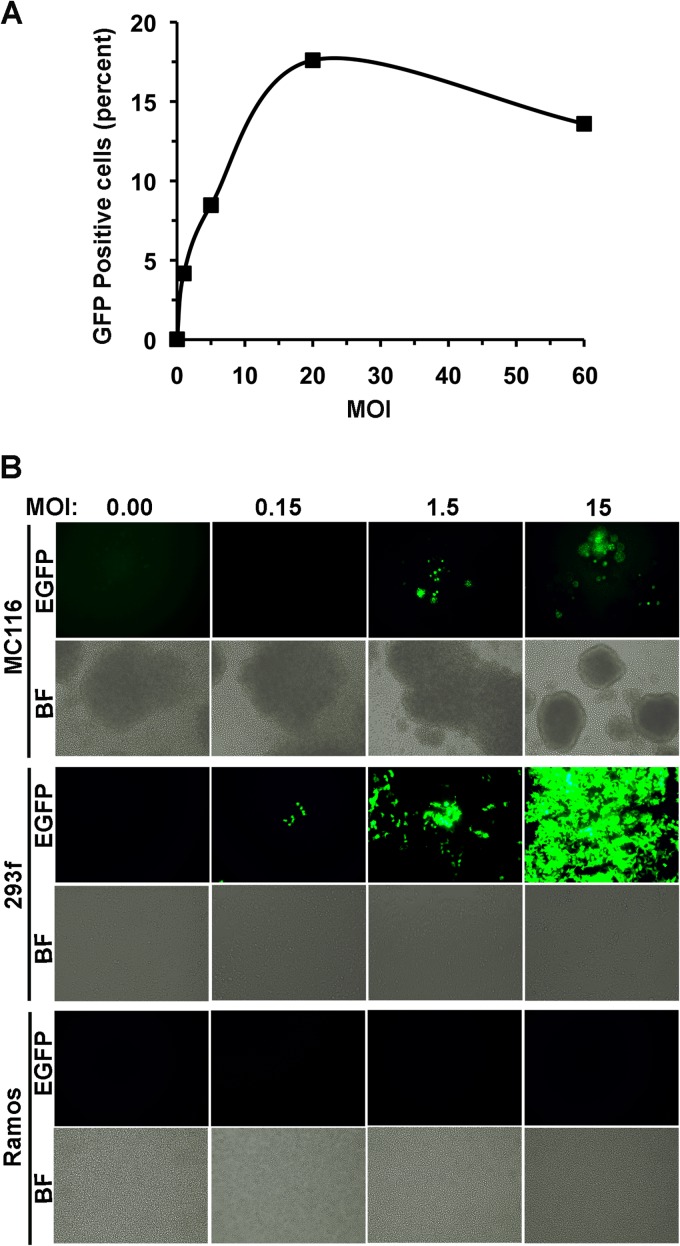

Flow cytometry was performed to quantitate the fraction of MC116 cells that expressed EGFP following exposure to rKSHV.219 at various MOIs. The fraction of infected cells increased in a dose-dependent fashion through an MOI of 20 (Fig. 2A); in repeated experiments, the maximal fraction of infected MC116 cells was 17 to 20%, on the basis of EGFP expression. The KSHV susceptibility of MC116 cells was compared to that of cells of the 293F cell line, which are known to be highly susceptible to infection (30, 31, 33). In the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 2B, MC116 cells were clearly infected at the higher MOIs (up to 15); as expected, the 293F cells strongly fluoresced in a dose-dependent fashion over the same range of exposure, whereas the Ramos cells were refractory to infection throughout this range. Taken together, these results indicate that among continuous human B cell lines, MC116 displayed a distinctively high susceptibility to KSHV infection; the infected cells were predominantly in latent phase.

FIG 2.

Effect of MOI on KSHV infection of various human cell lines. (A) MC116 cells were exposed to rKSHV.219 at the indicated MOI (based on titration on 293F cells) for 3 days. The percentage of cells expressing EGFP was determined by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. EGFP-positive cells were plotted as a percentage of the population. (B) The designated cell lines were exposed to rKSHV.219 at the indicated MOIs. Images were taken at day 4 after virus exposure. Magnification, ×10.

Phenotypic analysis of MC116 cells based on surface marker expression.

We analyzed the various human B cell lines by flow cytometry for surface expression of IgM and immunoglobulin light chains (summarized in Table 2). The IgM(λ) phenotype was confirmed for MC116 cells, as previously reported (41), and for Ramos cells (46). SU-DHL-6 cells were of the IgM(κ) phenotype, consistent with the correction (48) of the originally reported IgM(λ) phenotype (42). BJAB cells were confirmed to express IgM, as previously described (47), and were also found to express the κ light chain. Louckes cells were similarly IgM(κ) positive, whereas EJ-1 cell were IgM negative and λ positive, and JM-1 and Reh cells were negative for IgM and immunoglobulin light chain surface expression.

TABLE 2.

B cell line expression of IgM and immunoglobulin κ and λ light chains

| Cell line | Mean fluorescence intensitya |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | κ | λ | |

| BJAB | 98 | 61 | <2 |

| Ramos | 168 | <1 | 478 |

| JM-1 | 4 | <1 | <2 |

| Reh | 7 | <1 | <2 |

| MC116 | 107 | <1 | 140 |

| SU-DHL-6 | 160 | 122 | <2 |

| EJ-1 | 5 | <1 | 182 |

| Louckes | 115 | 343 | <2 |

Mean fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry.

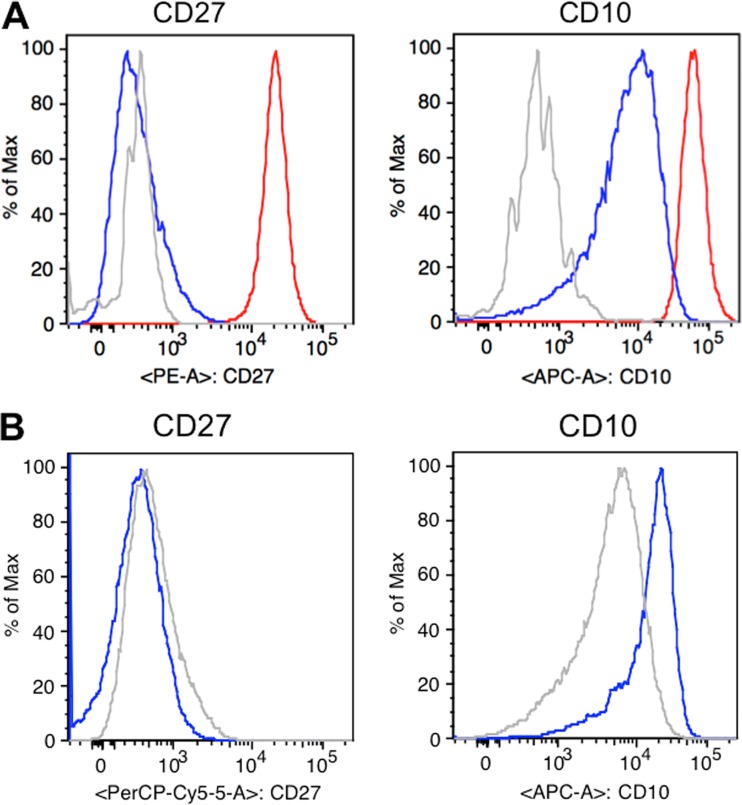

MC116 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for typical phenotypic markers, with the well-studied Ramos cells used for comparison (Fig. 3A). Both cell lines showed comparable profiles for most markers examined, including expression of CD10, CD19, CD20, and CD38 and a lack of expression of CD21 and CD23. The major difference between the two cell lines was a lack of CD27 expression on MC116 cells, in contrast to the expression of CD27 on Ramos cells. The expression of CD10 in the absence of CD27 on MC116 cells is characteristic of more immature transitional B cells (49), whereas the double CD10+/CD27+ profile of Ramos cells is consistent with more mature germinal center B cells (50).

FIG 3.

(A) Phenotypic characterization of B cell surface markers. Histograms showing unstained MC116 cells (gray) and MC116 (blue) and Ramos (red) cells stained with anti-CD27-PE (left) or anti-CD10-APC (right). Samples were acquired on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo software. (B) Effects of KSHV infection on B cell surface phenotypic marker expression. The histograms show uninfected MC116 cells (gray) and MC116.219 cells (blue) stained with anti-CD27-PerCP-Cy5.5 (left) and anti-CD10-APC (right).

Selection of uniformly infected MC116 cells.

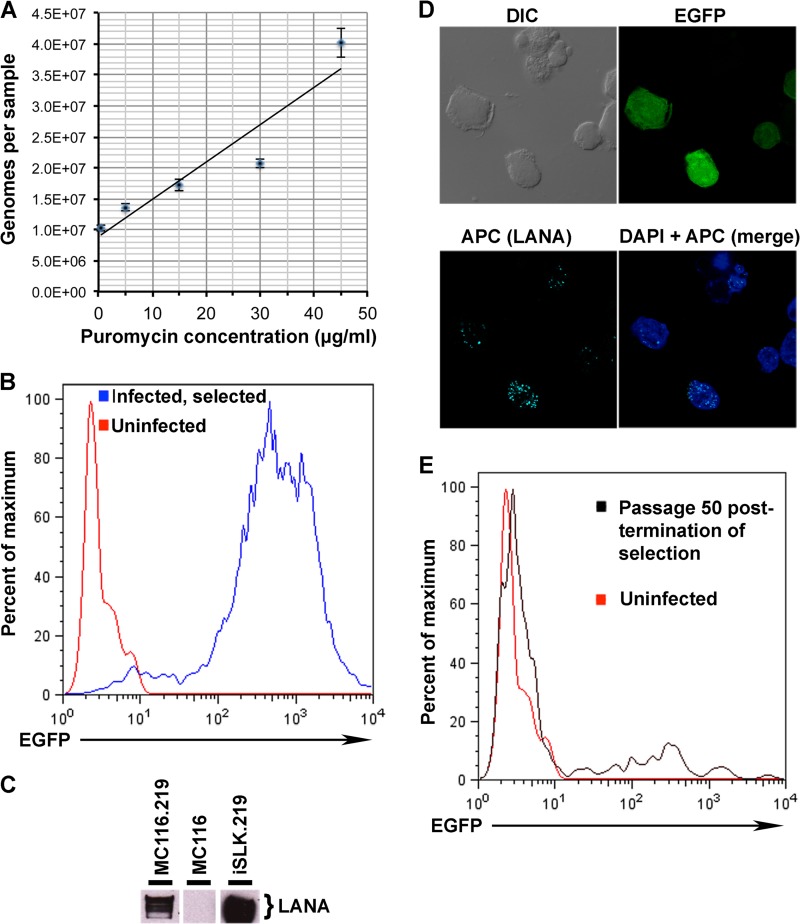

We exploited the puromycin resistance gene in rKSHV.219 to select cultures of uniformly infected B cells. The panel of B cell lines was initially exposed to rKSHV.219 over a range of MOIs (0.5 to 20) and then cultured in the presence of 0.5 μg/ml puromycin for 14 days. With MC116 cells, KSHV-exposed cell survival was high over the entire MOI range, whereas with the BJAB and Reh cell lines, surviving cells were observed only at the highest MOI and to a lesser extent than surviving MC116 cells; no survival was detected with the other B cell lines, even at the highest MOI tested (data not shown). These results are consistent with the greater susceptibility of MC116 cells to KSHV infection. In the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 4A, MC116 cells were infected with rKSHV.219 and initially cultured in 0.5 μg/ml puromycin; the puromycin concentration was then incrementally increased (3 passages at each dose). Real-time PCR analysis revealed that puromycin dose escalation up to 45 μg/ml resulted in an increase in KSHV copy number, similar to what has been reported for chronically infected iSLK.219 cells (36), derived from cells of the SLK cell line originally considered to be of endothelial origin but recently shown to be indistinguishable from the Caki-1 cell line of the epithelial cell lineage derived from a renal cell carcinoma (51); MC116 cell survival was poor at 60 μg/ml puromycin (not shown). Subsequent experiments were performed with infected selected cells maintained in the presence of 5 μg/ml puromycin; these cells were designated MC116.219.

FIG 4.

Puromycin selection of KSHV-infected MC116 cells. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of KSHV genomes in the selected cell lines. The relative numbers of genomes per sample (200 ng of total cellular DNA) are shown on the y axis; puromycin treatment levels are indicated along the x axis (0.5 to 45 μg/ml). (B) Histogram depicting flow cytometric data from uninfected MC116 cells (red) or infected MC116.219 cells (blue) following selection in 15 μg/ml puromycin. (C) Western blot analysis of LANA in infected/selected cells (MC116.219 or iSLK.219) or uninfected cells (MC116). (D) Confocal images of MC116.219 cells stained for DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and LANA, as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. Differential interference contrast microscopy and EGFP images are shown as indicated. At the top center in the differential interference contrast (DIC) and APC panels is an example of the occasionally observed cell cluster displaying LANA dots but minimal EGFP; this may represent an unhealthy or dying cell depleted of its cytoplasmic contents. (E) Analysis of loss/retention of KSHV infection (EGFP expression) after 50 passages of MC116.219 cells in the absence of puromycin (black); results are shown for uninfected MC116 cells, used as negative controls (red).

Flow cytometric analysis of MC116.219 cells indicated that nearly the entire cell population displayed strong EGFP expression, indicative of rKSHV.219 infection (Fig. 4B). The absence of RFP expression suggested that the cells maintained under these conditions were predominantly in the latent phase. To test directly for latency, we examined the expression of LANA protein. The results of the Western blot analysis in Fig. 4C confirm LANA expression in MC116.219 cells, as in the iSLK.219 positive-control cells; as expected, LANA was not detected in uninfected MC116 cells. At the individual cell level, immunoconfocal microscopy revealed that most of the MC116.219 cells displayed nuclear LANA dots (Fig. 4D), which have been shown to correlate quantitatively with viral episome presence (52). These results confirm that MC116.219 cells are mainly in the latent phase of KSHV infection. Analysis of B cell phenotypic markers (Fig. 3B) indicated that KSHV-infected MC116.219 cells remained CD27 negative and showed increased CD10 positivity (that level was elevated approximately 7-fold, on the basis of the mean fluorescence intensity).

The effects of removing the puromycin selection pressure were examined. Figure 4E shows the pattern of fluorescence of MC116.219 cells at 50 passages in the absence of puromycin; while the bulk of the population displayed only minimal EGFP expression, a minor subpopulation (∼5%) maintained significant expression; this pattern was observed earlier (at approximately passage 20) and was maintained through subsequent passages. The large number of EGFP-expressing cells presumably reflects selection-independent maintenance of the rKSHV.219 genome in only a small subpopulation of infected cells; a less likely alternative is that the viral genomes are retained throughout the infected cell population but silenced in all but a small subset of the cells.

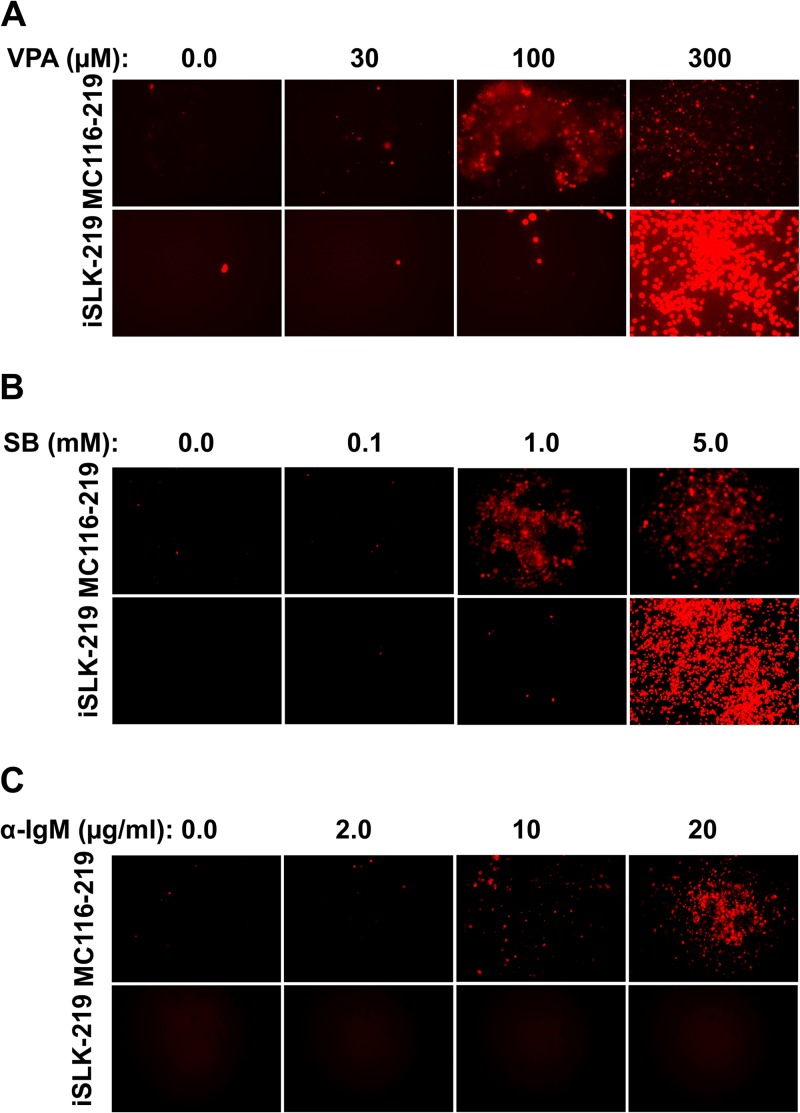

Activation of lytic replication by general and B cell-specific pathways.

In PEL cells as well as in KSHV-infected non-B cell systems, histone deacetylase inhibitors have been found to induce the transition from latent to lytic infection (31, 36, 53, 54). We examined this effect in the MC116.219 cells and, for comparison, in iSLK.219 cells. The responses of these cells to VPA or SB were initially assessed by monitoring the expression of RFP, encoded in the rKSHV.219 recombinant virus under the control of the early lytic PAN promoter. As observed at day 5 posttreatment (Fig. 5A), cells of both chronically infected cell lines were induced by VPA in a dose-dependent fashion; at concentrations up to 100 μM, the MC116.219 cells showed somewhat greater responsiveness than the iSLK.219 cells; at a higher VPA concentration (300 μM), RFP expression was further induced for iSLK.219 cells but not for MC116.219 cells. A similar pattern was observed with SB as the lytic-phase inducer (Fig. 5B), with MC116.219 cells displaying a greater response than iSLK.219 cells at lower concentrations (up to 1 mM), but the dramatic increase at a higher concentration (5 mM) was not observed. These results confirm that MC116.219 cells can be induced to enter the early lytic phase of KSHV infection in response to histone deacetylase inhibitors, as is commonly observed for other KSHV-infected cell lines.

FIG 5.

Comparison of treatments for activating RFP expression in cells chronically infected with rKSHV.219. Micrographs display MC116.219 or iSLK.219 cells treated for 5 days with the indicated amounts of valproic acid (VPA) (A), sodium butyrate (SB) (B), or anti-IgM polyclonal antibody (α-IgM) (C).

We next tested whether early-lytic-phase induction could be induced in MC116.219 cells via a B cell-specific pathway, i.e., activation of the B cell receptor (BCR) by cross-linking with anti-IgM antibody. Figure 5C shows that RFP expression in MC116.219 cells was prominently induced by anti-IgM antibody in a dose-dependent fashion at concentrations up to 20 μg/ml; in contrast, this treatment had no effect on the iSLK.219 cells at this dose range (and even up to 100 μg/ml; not shown). Thus, BCR activation represents a B cell-specific pathway for activating the lytic phase in MC116.219 cells.

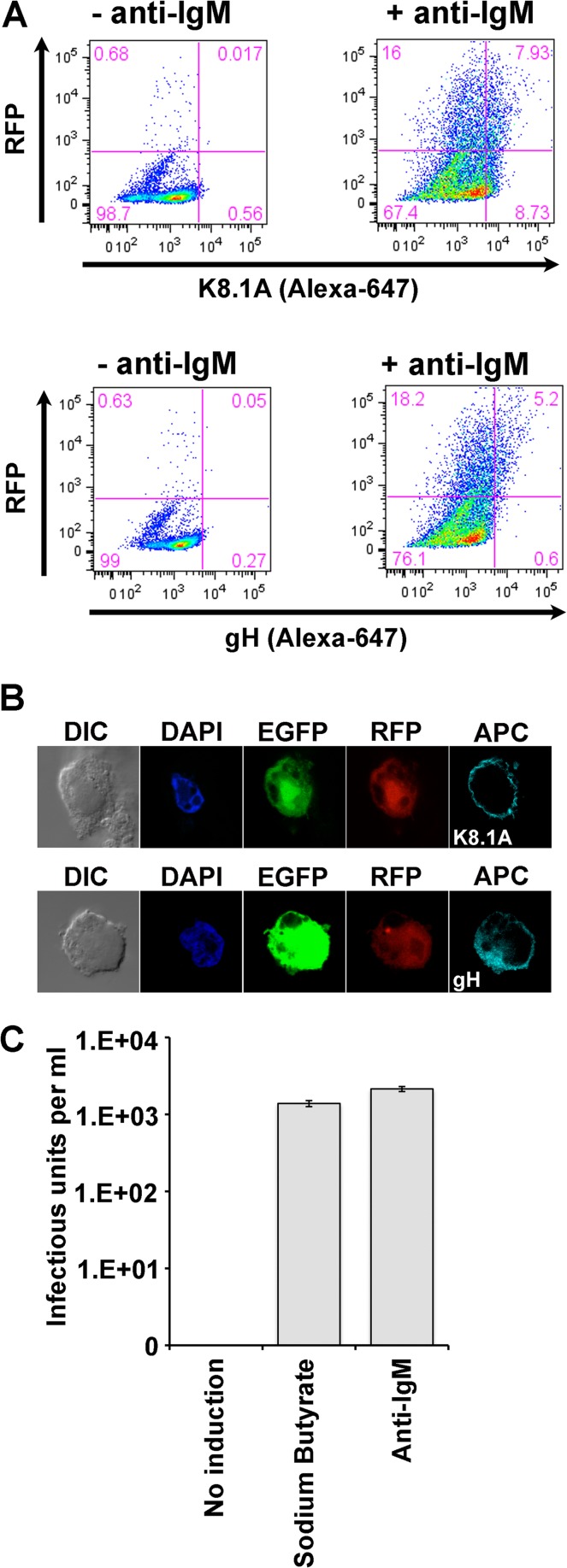

We extended these findings to examine induction of late-lytic-phase KSHV gene expression, specifically, expression of the structural glycoproteins K8.1A and gH (Fig. 6). Flow cytometry analyses (Fig. 6A) confirmed that BCR activation with anti-IgM antibody induced a significant fraction of MC116.219 cells to express not only RFP (23 to 24%) but also K8.1A (7.9%; Fig. 6A, bottom) and gH (5.2%; Fig. 6A, top). Immunoconfocal microscopy after anti-IgM treatment (Fig. 6B) revealed surface staining for both glycoproteins on some of the RFP-positive cells; no K8.1A or gH staining was observed in untreated cells (not shown). Thus, BCR activation is capable of inducing late-lytic-phase gene expression in at least a fraction of the MC116.219 cells.

FIG 6.

Induction of lytic phase in MC116.219 cells. (A) MC116.219 cells were treated with 10 μg/ml of anti-IgM polyclonal antibody for 3 days. Cells were fixed and probed for viral glycoprotein K8.1A (MAb 4C3) or gH (MAb15), followed by probing with an antimouse-APC conjugate. Data acquisition was performed using a FACSAria cytometer, and analysis was performed using FlowJo software. (B) Confocal micrographs of MC116.219 cells treated as described for panel A and examined as indicated. Glycoprotein detection was with anti-mouse IgG1 conjugated to APC, depicted in cyan. (C) MC116.219 cells were induced with 2.5 mM sodium butyrate or 10 μg/ml of anti-IgM polyclonal antibody, as indicated. Supernatants were cleared of debris, concentrated, and titrated for infectious KSHV on adherent 293F cells, scoring for EFGP-positive (infected) cells.

Finally, we examined whether MC116.219 cells could be activated to produce and release infectious KSHV virions. The cells were exposed to the indicated treatments for 3 days, and infectious virus titers in the cell supernatants were determined by titration on 293F cells on the basis of flow cytometric quantification of EGFP-expressing cells. The experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 6C demonstrates marked stimulation of infectious KSHV release by treatment with either SB or anti-IgM compared to that with no treatment, in which cells yielded negligible infectious virus. We conclude that at least some MC116.219 cells can be induced to proceed through the full KSHV lytic cascade; this was achieved not only with the broadly acting SB but also with the B cell-specific activation of the BCR.

DISCUSSION

The etiologic association of KSHV with two B cell pathologies (MCD and PEL), coupled with the likely role of B cells as a major KSHV reservoir in vivo and a source of transmitted virus, highlights the critical need for a practical experimental system in which to study infection of this cell type. Indeed cell-free infection of B cell lines has proven valuable for the study of other gammaherpesviruses, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (55), murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (56), and rhesus rhadinovirus (57). The MC116 human B cell line provides a comparable system for KSHV. Its susceptibility to infection by cell-free virus overcomes the infection resistance of other previously analyzed B cell lines (30, 32, 33) as well as the requirement for the use of cell-associated virus, which is employed for infectivity studies of primary B cells (35) and stable B cell lines (58).

Our search for a KSHV-susceptible human B cell line was guided in part by previous reports indicating that B cells expressing IgM(λ) were preferentially infected in vivo (39) and in human tonsillar explants (19). MC116 cells display the IgM(λ) phenotype. However, this property is not sufficient for KSHV susceptibility, given that the Ramos cell line was refractory to KSHV infection, despite IgM(λ) surface expression. Whether this phenotype is mechanistically necessary for KSHV susceptibility is unknown; it is possible that IgM(λ) expression and KSHV susceptibility are simply unrelated consequences of the same molecular regulatory events or that the phenotypes are purely coincidental with no underlying mechanistic relationships. The phenotypic characterization of MC116 cells as transitional B cells suggests that KSHV might parallel murine gammaherpesvirus 68, which has recently been shown to establish latency in immature and transitional B cells during in vivo infection (59). Our results are also consistent with early findings that KSHV can be transmitted to B cells present in cord blood mononuclear cells (15), which contain a high frequency of transitional B cells (49).

Cross-linking of surface immunoglobulin has been reported to activate gammaherpesviruses from latent to lytic phase, as shown for EBV with anti-IgG (60, 61) and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 with anti-mouse IgM-IgG (62). Our findings demonstrate that KSHV also follows this pattern, in this case, by cross-linking of the surface IgM present on MC116 cells. Our finding that, upon BCR stimulation, only a fraction of the RFP-positive cells also expressed late structural glycoproteins (K8.1A, gH) is consistent with the asynchronous nature of KSHV lytic reactivation (52). These findings expand on the well-known complex relationships between the replication cycles of gammaherpesviruses and BCR signaling pathways (1, 63–65).

Note.

While the manuscript was under review, it was reported (66) that BJAB cells latently infected with KSHV can be reactivated into lytic phase by anti-IgM antibody stimulation of the BCR and consequent activation of specific intracellular signaling pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Stephen Suh and John Yates for donation of the EJ-1 and Louckes B cell lines, respectively, and Don Ganem for the iSLK.219 cells. The outstanding technical assistance of Virgilio Bundoc is gratefully appreciated, as are the discussions with Deboeeta Chatterjee.

This research was funded in part by the Intramural Program of the NIH, NIAID.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 November 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Wen KW, Damania B. 2010. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV): molecular biology and oncogenesis. Cancer Lett. 289:140–150. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cesarman E. 2011. Gammaherpesvirus and lymphoproliferative disorders in immunocompromised patients. Cancer Lett. 305:163–174. 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gantt S, Casper C. 2011. Human herpesvirus 8-associated neoplasms: the roles of viral replication and antiviral treatment. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 24:295–301. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283486d04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA-sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's-sarcoma. Science 266:1865–1869. 10.1126/science.7997879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. 2010. Kaposi's sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10:707–719. 10.1038/nrc2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganem D. 2010. KSHV and the pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma: listening to human biology and medicine. J. Clin. Invest. 120:939–949. 10.1172/JCI40567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uldrick TS, Whitby D. 2011. Update on KSHV epidemiology, Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 305:150–162. 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy D, Mitsuyasu R. 2011. HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 23:475–481. 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328349c233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Yarchoan R. 2012. Recent advances in Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 24:495–505. 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328355e0f3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupin N, Fisher C, Kellam P, Ariad S, Tulliez M, Franck N, van Marck E, Salmon D, Gorin I, Escande JP, Weiss RA, Alitalo K, Boshoff C. 1999. Distribution of human herpesvirus-8 latently infected cells in Kaposi's sarcoma, multicentric Castleman's disease, and primary effusion lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:4546–4551. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitby D, Howard MR, Tenantflowers M, Brink NS, Copas A, Boshoff C, Hatzioannou T, Suggett FEA, Aldam DM, Denton AS, Miller RF, Weller IVD, Weiss RA, Tedder RS, Schulz TF. 1995. Detections of Kaposi-sarcoma associated herpesvirus in peripheral-blood of HIV-infected individuals and progression to Kaposi's-sarcoma. Lancet 346:799–802. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91619-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambroziak JA, Blackbourn DJ, Herndier BG, Glogau RG, Gullett JH, McDonald AR, Lennette ET, Levy JA. 1995. Herpes-like sequences in HIV-infected and uninfected Kaposi's-sarcoma patients. Science 268:582–583. 10.1126/science.7725108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang YQ, Li JJ, Poiesz BJ, Kaplan MH, FriedmanKien AE. 1997. Detection of the herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in matched specimens of semen and blood from patients with AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma by polymerase chain reaction in situ hybridization. Am. J. Pathol. 150:147–153 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbone A, Cesarman E, Gloghini A, Drexler HG. 2010. Understanding pathogenetic aspects and clinical presentation of primary effusion lymphoma through its derived cell lines. AIDS 24:479–490. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283365395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Arvanitakis L, Rafii S, Moore MAS, Posnett DN, Knowles DM, Asch AS. 1996. Human herpesvirus-8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a new transmissible virus that infects B cells. J. Exp. Med. 183:2385–2390. 10.1084/jem.183.5.2385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renne R, Zhong WD, Herndier B, McGrath M, Abbey N, Kedes D, Ganem D. 1996. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat. Med. 2:342–346. 10.1038/nm0396-342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo JJ, Bohenzky RA, Chien MC, Chen J, Yan M, Maddalena D, Parry JP, Peruzzi D, Edelman IS, Chang Y, Moore PS. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:14862–14867. 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rappocciolo G, Hensler HR, Jais M, Reinhart TA, Pegu A, Jenkins FJ, Rinaldo CR. 2008. Human herpesvirus 8 infects and replicates in primary cultures of activated B lymphocytes through DC-SIGN. J. Virol. 82:4793–4806. 10.1128/JVI.01587-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassman LM, Ellison TJ, Kedes DH. 2011. KSHV infects a subset of human tonsillar B cells, driving proliferation and plasmablast differentiation. J. Clin. Invest. 121:752–768. 10.1172/JCI44185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myoung J, Ganem D. 2011. Active lytic infection of human primary tonsillar B cells by KSHV and its noncytolytic control by activated CD4(+) T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 121:1130–1140. 10.1172/JCI43755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myoung JJ, Ganem D. 2011. Infection of primary human tonsillar lymphoid cells by KSHV reveals frequent but abortive infection of T cells. Virology 413:1–11. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieira J, Huang ML, Koelle DM, Corey L. 1997. Transmissible Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in saliva of men with history of Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Virol. 71:7083–7087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koelle DM, Huang ML, Chandran B, Vieira J, Piepkorn M, Corey L. 1997. Frequent detection of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) DNA in saliva of human immunodeficiency virus-infected men: clinical and immunologic correlates. J. Infect. Dis. 176:94–102. 10.1086/514045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauk J, Huang ML, Brodie SJ, Wald A, Koelle DM, Schacker T, Celum C, Selke S, Corey L. 2000. Mucosal shedding of human herpesvirus 8 in men. N. Engl. J. Med. 343:1369–1377. 10.1056/NEJM200011093431904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dedicoat M, Newton R, Alkharsah KR, Sheldon J, Szabados I, Ndlovu B, Page T, Casabonne D, Gilks CF, Cassol SA, Whitby D, Schulz TF. 2004. Mother-to-child transmission of human herpesvirus-8 in South Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1068–1075. 10.1086/423326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casper C, Krantz E, Selke S, Kuntz SR, Wang J, Huang ML, Pauk JS, Corey L, Wald A. 2007. Frequent and asymptomatic oropharyngeal shedding of human herpesvirus 8 among immunocompetent men. J. Infect. Dis. 195:30–36. 10.1086/509621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bagni R, Whitby D. 2009. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus transmission and primary infection. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 4:22–26. 10.1097/COH.0b013e32831add5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speck SH, Ganem D. 2010. Viral latency and its regulation: lessons from the gamma-herpesviruses. Cell Host Microbe 8:100–115. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou FC, Zhang YJ, Deng JH, Wang XP, Pan HY, Hettler E, Gao SJ. 2002. Efficient infection by a recombinant Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cloned in a bacterial artificial chromosome: application for genetic analysis. J. Virol. 76:6185–6196. 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6185-6196.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bechtel JT, Liang YY, Hvidding J, Ganem D. 2003. Host range of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured cells. J. Virol. 77:6474–6481. 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6474-6481.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vieira J, O'Hearn PM. 2004. Use of the red fluorescent protein as a marker of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression. Virology 325:225–240. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renne R, Blackbourn D, Whitby D, Levy J, Ganem D. 1998. Limited transmission of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured cells. J. Virol. 72:5182–5188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blackbourn DJ, Lennette E, Klencke B, Moses A, Chandran B, Weinstein M, Glogau RG, Witte MH, Way DL, Kutzkey T, Herndier B, Levy JA. 2000. The restricted cellular host range of human herpesvirus 8. AIDS 14:1123–1133. 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friborg J, Kong WP, Flowers CC, Flowers SL, Sun YN, Foreman KE, Nickoloff BJ, Nabel GJ. 1998. Distinct biology of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus from primary lesions and body cavity lymphomas. J. Virol. 72:10073–10082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myoung J, Ganem D. 2011. Infection of lymphoblastoid cell lines by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: critical role of cell-associated virus. J. Virol. 85:9767–9777. 10.1128/JVI.05136-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myoung J, Ganem D. 2011. Generation of a doxycycline-inducible KSHV producer cell line of endothelial origin: maintenance of tight latency with efficient reactivation upon induction. J. Virol. Methods 174:12–21. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hahn A, Birkmann A, Wies E, Dorer D, Mahr K, Sturzl M, Titgemeyer F, Neipel F. 2009. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gH/gL: glycoprotein export and interaction with cellular receptors. J. Virol. 83:396–407. 10.1128/JVI.01170-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Godfrey A, Anderson J, Papanastasiou A, Takeuchi Y, Boshoff C. 2005. Inhibiting primary effusion lymphoma, by lentiviral vectors encoding short hairpin RNA. Blood 105:2510–2518. 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dupin N, Diss TL, Kellam P, Tulliez M, Du MQ, Sicard D, Weiss RA, Isaacson PG, Boshoff C. 2000. HHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8-positive plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood 95:1406–1412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du MQ, Liu HX, Diss TC, Ye HT, Hamoudi RA, Dupin N, Meignin V, Oksenhendler E, Boshoff C, Isaacson PG. 2001. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infects monotypic (IgM lambda) but polyclonal naive B cells in Castleman disease and associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood 97:2130–2136. 10.1182/blood.V97.7.2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magrath IT, Pizzo PA, Whangpeng J, Douglass EC, Alabaster O, Gerber P, Freeman CB, Novikovs L. 1980. Characterization of lymphoma-derived cell-lines—comparison of cell-lines positive and negative for Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen. 1. Physical, cytogenetic, and growth-characteristics. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 64:465–476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein AL, Levy R, Kim H, Henle W, Henle G, Kaplan HS. 1978. Biology of human malignant-lymphomas. 4. Functional characterization of 10 diffuse histiocytic lymphoma cell lines. Cancer 42:2379–2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park LS, Friend D, Price V, Anderson D, Singer J, Prickett KS, Urdal DL. 1989. Heterogeneity in human interleukin-3 receptors—a subclass that binds human granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor. J. Biol. Chem. 264:5420–5427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greaves M, Janossy G. 1978. Patterns of gene expression and cellular origins of human leukemias. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 516:193–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goy A, Ramdas L, Remache YK, Gu J, Fayad L, Hayes KJ, Coombes KR, Barkoh BA, Katz R, Ford R, Cabanillas F, Gilles F. 2003. Establishment and characterization by gene expression profiling of a new diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell line, EJ-1, carrying t(14;18) and t(8;14) translocations. Lab. Invest. 83:913–916. 10.1097/01.LAB.0000074890.89650.AD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spira G, Aman P, Koide N, Lundin G, Klein G, Hall K. 1981. Cell-surface immunoglobulin and insulin-receptor expression in an EBV-negative lymphoma cell-line and its EBV-converted sublines. J. Immunol. 126:122–126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer PA, Williamson AR. 1980. Cell-surface immunoglobulin mu-chains and gamma-chains of human lymphoid-cells are of higher apparent molecular-weight than their secreted counterparts. Eur. J. Immunol. 10:180–186. 10.1002/eji.1830100305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winter JN, Variakojis D, Epstein AL. 1984. Phenotypic analysis of established diffuse histiocytic lymphoma cell-lines utilizing monoclonal-antibodies and cytochemical techniques. Blood 63:140–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sims GP, Ettinger R, Shirota Y, Yarboro CH, Illei GG, Lipsky PE. 2005. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood 105:4390–4398. 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bohnhorst JO, Bjorgan MB, Thoen JE, Natvig JB, Thompson KM. 2001. Bm1-Bm5 classification of peripheral blood B cells reveals circulating germinal center founder cells in healthy individuals and disturbance in the B cell subpopulations in patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. J. Immunol. 167:3610–3618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sturzl M, Gaus D, Dirks WG, Ganem D, Jochmann R. 2013. Kaposi's sarcoma-derived cell line SLK is not of endothelial origin, but is a contaminant from a known renal carcinoma cell line. Int. J. Cancer 132:1954–1958. 10.1002/ijc.27849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adang LA, Parsons CH, Kedes DH. 2006. Asynchronous progression through the lytic cascade and variations in intracellular viral loads revealed by high-throughput single-cell analysis of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection. J. Virol. 80:10073–10082. 10.1128/JVI.01156-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller G, Rigsby MO, Heston L, Grogan E, Sun R, Metroka C, Levy JA, Gao SJ, Chang Y, Moore PS. 1996. Antibodies to butyrate-inducible antigens of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in patients with HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:1292–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaw RN, Arbiser JL, Offermann MK. 2000. Valproic acid induces human herpesvirus 8 lytic gene expression in BCBL-1 cells. AIDS 14:899–902. 10.1097/00002030-200005050-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calender A, Billaud M, Aubry JP, Banchereau J, Vuillaume M, Lenoir GM. 1987. Epstein-Barr-virus (EBV) induces expression of B-cell activation markers on in vitro infection of EBV-negative B-lymphoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84:8060–8064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Forrest JC, Speck SH. 2008. Establishment of B-cell lines latently infected with reactivation-competent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 provides evidence for viral alteration of a DNA damage-signaling cascade. J. Virol. 82:7688–7699. 10.1128/JVI.02689-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bilello JP, Lang SM, Wang F, Aster JC, Desrosiers RC. 2006. Infection and persistence of rhesus monkey rhadinovirus in immortalized B-cell lines. J. Virol. 80:3644–3649. 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3644-3649.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hahn HS, Desrosiers RC. 2013. Rhesus monkey rhadinovirus uses Eph family receptors for entry into B cells and endothelial cells but not fibroblasts. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003360. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coleman CB, Nealy MS, Tibbetts SA. 2010. Immature and transitional B cells are latency reservoirs for a gammaherpesvirus. J. Virol. 84:13045–13052. 10.1128/JVI.01455-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takada K. 1984. Cross-linking of cell-surface immunoglobulins induces Epstein-Barr virus in Burkitt-lymphoma lines. Int. J. Cancer 33:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tovey MG, Lenoir G, Begonlours J. 1978. Activation of latent Epstein-Barr virus by antibody to human IgM. Nature 276:270–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moser JM, Upton JW, Gray KS, Speck SH. 2005. Ex vivo stimulation of B cells latently infected with gammaherpesvirus 68 triggers reactivation from latency. J. Virol. 79:5227–5231. 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5227-5231.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Damania B, Desrosiers RC. 2001. Simian homologues of human herpesvirus 8. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356:535–543. 10.1098/rstb.2000.0782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barton E, Mandal P, Speck SH. 2011. Pathogenesis and host control of gammaherpesviruses: lessons from the mouse. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29:351–397. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-072710-081639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalla M, Hammerschmidt W. 2012. Human B cells on their route to latent infection—early but transient expression of lytic genes of Epstein-Barr virus. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 91:65–69. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kati S, Tsao EH, Gunther T, Weidner-Glunde M, Rothamel T, Grundhoff A, Kellam P, Schulz TF. 2013. Activation of the B cell antigen receptor triggers reactivation of latent Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in B cells. J. Virol. 87:8004–8016. 10.1128/JVI.00506-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu L, Puri V, Chandran B. 1999. Characterization of human herpesvirus-8 K8.1A/B glycoproteins by monoclonal antibodies. Virology 262:237–249. 10.1006/viro.1999.9900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chatterjee D, Chandran B, Berger EA. 2012. Selective killing of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytically infected cells with a recombinant immunotoxin targeting the viral gpK8.1A envelope glycoprotein. MAbs 4:233–242. 10.4161/mabs.4.2.19262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cai Y, Berger EA. 2011. An immunotoxin targeting the gH glycoprotein of KSHV for selective killing of cells in the lytic phase of infection. Antiviral Res. 90:143–150. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.03.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]