Abstract

Background & Aims

Paneth cells contribute to the small intestinal niche of Lgr5+ stem cells. Although the colon also contains Lgr5+ stem cells, it does not contain Paneth cells. We investigated the existence of colonic Paneth-like cells that have a distinct transcriptional signature and support Lgr5+ stem cells.

Methods

We used multicolor fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate different subregions of colon crypts, based on known markers, from dissociated colonic epithelium of mice. We performed multiplexed single-cell gene expression analysis with quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction followed by hierarchical clustering analysis to characterize distinct cell types. We used immunostaining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses with in vivo administration of a Notch inhibitor and in vitro organoid cultures to characterize different cell types.

Results

Multicolor fluorescence-activated cell sorting could isolate distinct regions of colonic crypts. Four major epithelial subtypes or transcriptional states were revealed by gene expression analysis of selected populations of single cells. One of these, the goblet cells, contained a distinct cKit/CD117+ crypt base subpopulation that expressed Dll1, Dll4, and epidermal growth factor, similar to Paneth cells, which were also marked by cKit. In the colon, cKit+ goblet cells were interdigitated with Lgr5+ stem cells. In vivo, this colonic cKit+ population was regulated by Notch signaling; administration of a γ-secretase inhibitor to mice increased the number of cKit+ cells. When isolated from mouse colon, cKit+ cells promoted formation of organoids from Lgr5+ stem cells, which expressed Kitl/stem cell factor, the ligand for cKit. When organoids were depleted of cKit+ cells using a toxin-conjugated antibody, organoid formation decreased.

Conclusions

cKit marks small intestinal Paneth cells and a subset of colonic goblet cells that are regulated by Notch signaling and support Lgr5+stem cells.

Keywords: Cancer, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Intestine, Regenerate

The epithelial lining of the colon is continuously replaced every few days, a process driven by self-renewing stem cells at the crypt base. The progeny of these multipotent stem cells migrate toward the lumen as they divide and differentiate into the following mature cell types: absorptive enterocytes, mucous-secreting goblet cells, and hormone-secreting enteroendocrine cells.1,2 Mature cells are eventually extruded from the epithelium into the lumen. In vivo lineage tracing experiments using knock-in mice have demonstrated Lgr5 to be a stem cell marker in both the small intestine and the colon.3 Similarly, in humans, Lgr5 is highly enriched in cells that form self-renewing organoids.4

Cultured Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells require growth factors that activate Notch-signaling, epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor signaling, and Wnt-signaling in order to generate organoids.4–6 In vivo, disruption of these signaling pathways causes severe disruptions of the intestinal epithelium, with decreased crypt base proliferation.7–10 For example, blocking Notch signaling genetically, chemically, or with blocking antibodies (for review, see Vooijs et al11) leads to decreased crypt proliferation, loss and apoptosis of Lgr5+ cells, and the differentiation of progenitor cells toward a secretory phenotype.

In the small intestine, the Paneth cell most likely represents the cellular source for Lgr5+ stem cell trophic factors. Paneth cells are adjacent to the small intestinal Lgr5 cells and provide several crucial factors in intestinal crypt homeostasis and Lgr5+ stem cell proliferation, including Notch ligand (Dll4), EGF receptor ligands (EGF, transforming growth factor–α), and Wnt (Wnt3).6 Although hypothesized to exist,6,12 the identity of a colonic Paneth-like cell that supports the Lgr5+ stem cells has remained obscure.

We hypothesized that a colonic Paneth-like cell exists, has a distinct transcriptional signature, and supports Lgr5+ stem cells. We used multicolor fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with widely available cell surface markers to prospectively isolate distinct colon crypt sub-regions (ie, the bottom vs the top of the crypt) and then used multiplexed single-cell quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) with hierarchical clustering analysis13 to obtain a single-cell characterization of murine colon epithelium. This analysis led to the isolation of a novel cKit+ goblet cell. In vivo, the relative abundance of these cells within the epithelium is regulated by Notch signaling. These cells express factors implicated in stem cell maintenance (such as Dll1, Dll4, and EGF), and in vitro they promote organoid formation by Lgr5 colon cells.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were maintained at the Stanford University Research Animal Facility in accordance with Stanford University guidelines. Mouse strains included C57BL/6, Lgr5-CreER-IRES-GFP3 (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME), and the cKit reporter Tg(Kit-EGFP)IF44Gsat14 (MMRRC). Mice were genotyped by PCR using primers and protocols recommended by the suppliers.

Tissue Preparation

Tissues studied include total adult (2 to 4 months old) murine colon (ascending colon to proximal rectum, omitting the cecum) and the proximal 10 cm small intestine distal to the pylorus. Tissue was dissected, gently flushed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove fecal matter, sliced into 1-mm3 pieces with a razor blade, washed with PBS in a 25 mL pipette by drawing fragments up and allowing them to settle by gravity, and subsequently digested at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 20% O2 for 3 hours, pipetting every 15 minutes in 10 mL digestion buffer per colon. This consisted of advanced Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium/F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1× Glutamax (Invitrogen), 120 μg/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin-B, 10 mM Hepes, 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, with 200 U/mL Collagenase type III (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ), and 100 U/mL DNase I (Worthington). An equal volume of PBS + 10 mM EDTA was then added for 30 minutes to help disaggregate cells. Digestions were monitored with an inverted microscope to check for dissociation into single cells. Cell suspensions were filtered with 40-μm nylon mesh (BD Biosciences), counted in a hemocytometer, and resuspended at 0.5 to 1 × 106 cells/mL in cold digestion media lacking collagenase and DNAse. For culture experiments, cells were supplemented at all times with 10 uM Y-27632 (Sigma), 1× N2 (Invitrogen), 1× B27 minus vitamin A (Invitrogen), and 1 mM N-acetylcysteine (Sigma).

Flow Cytometry

Cells in staining buffer were blocked for 10 minutes with 1 ug/mL rat IgG (Sigma) to eliminate nonspecific binding and were stained in the dark on ice with titered fluorescently conjugated antibodies: Esa-allophycocyanin-cyanine 7 or Alexa 488 (clone G8.8), CD45-phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy5 (clone 30F-11), CD44-PE-Cy7 (clone IM7), CD66a-PE (clone MAb-CC1), CD24-Alexa 647 or fluorescein isothiocyanate (clone M1/69), and cKit-PE or Alexa 488 (clones 2B8, ACK2, and 3C11). Flow cytometry was performed with a 130 uM nozzle on a BD FACSAria II using FACSDiva software. Debris and doublets were excluded by sequential gating on forward scatter area vs side scatter area, followed by forward scatter width vs forward scatter height, followed by side scatter height vs side width area (Supplementary Figure 1). Viable cells were identified by exclusion of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY). Additional details are described in the Supplementary Materials.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Tissue was dissected, flushed with PBS, and fixed at 25°C with 10% buffered formalin (Sigma). For immunofluorescence, tissues were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, embedded in OCT, frozen, and sectioned at −20°C. The 7-uM sections were permeabilized with PBS + 0.1% TritonX-100 (PBS-T), incubated in block (5% bovine serum albumin in PBS-T) for 30 minutes at 25°C, and stained with antibodies in block for 2 to 4 hours at 25°C. After washing in PBS-T, slides were incubated for 2 to 12 hours in secondary antibody, washed in PBS-T, and mounted in ProLong Gold+Dapi (Molecular Probes) and imaged with a Leica DMI6000B microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL). Images were captured with a QImaging Retiga2000R CCD camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada), processed with ImagePro 5.1 software (MediaCybernetics, Bethesda, MD), and post-processed with Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA). For immunohistochemistry, fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned to 4 uM, and processed for H&E staining or periodic acid-Schiff staining. Antibodies and dilutions are listed in Supplementary Table 2. All stainings were performed at least 3 times.

Gene Expression Analysis

RNA was harvested from sorted cells in Trizol (Invitrogen) following manufacturer's instructions using glycogen as a carrier. Complementary DNA was generated using the Superscript3 kit (Invitrogen) with random and gene-specific primers, and then qRT-PCR was conducted on an ABI7900HT Thermocycler using Taqman assays (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) for select genes (Supplementary Table 1) as suggested by the manufacturer. Samples were loaded in triplicate, and fold changes were calculated using Δ ΔCt, normalizing to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Cell Culture

Organoids were grown using published methods15 with minor modifications. Briefly, FACS-sorted cells were collected in cold organoid media (advanced Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium/F12 + 10 mM Hepes + 1× Glutamax + 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum + 1× N2 + 1× B27 + 1 mM n-acetylcysteine + 10 uM Y-27632 + human Rspondin3 (500 ng/mL; R&D) + murine EGF (10 ng/mL; R&D) + murine Noggin (100 ng/mL; R&D), and pelletted at 300g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then resuspended in growth factor reduced Matrigel (BD) with Jag1 peptide (1 uM; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and plated in 96-well plates with 1000 cells/well in 50 uL. Matrigel was polymerized at 37°C for 10 minutes and overlaid with organoid media at 37°C (100 uL/well). Organoids were grown in humidified tissue culture incubators at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 20% O2 and monitored daily under a microscope. For coculture experiments, sorted cells were mixed after FACS before centrifugation. Growth factors (EGF, Noggin, Rspondin) were added every other day, and media was changed weekly. Organoids were defined as viable multicellular (>50 cells) structures with a lumen and were scored 7 days post plating. Organoids were passaged by transferring to a 50-mL tube with cold PBS, centrifuging (100g, 5 minutes, 4°C), resuspending in 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), and incubating for 2 to 5 minutes at 37°C, while monitoring for dissociation into single cells. Organoid media was then added, cells were counted with a hemocytometer, and new organoids were seeded in Matrigel+Jag1 at 200 to 500 cells/well.

For saporin experiments, small intestinal organoids with crypt buds and visible Paneth cells were passaged as single cells as described. Before embedding in Matrigel, dissociated cells were incubated for 30 minutes on ice with biotinylated-2B8 (eBioscience) 1 ug/mL, biotinylated-rat IgG 1 ug/mL, streptavidin-saporin (Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA) 3 ug/mL, or a 1:4 molar mixture of biotinylated antibody and streptavidin-saporin. They were then embedded, overlaid with media, and cultured as described. Organoids were monitored daily and assayed at 7 days.

Single-Cell Gene Expression

Double-sorted (purity >95%) single cells were sorted into individual wells of 96-well plates containing 5 uL lysis buffer (CellsDirect qRT-PCR mix; Invitrogen) and 2 U (0.1 uL) SuperaseIn (Invitrogen) as described.13 Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Dibenzazepine Treatment

Adult female mice were injected intraperitoneally daily for 5 days with dibenzazepine (DBZ; Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ) 10 umol/kg or vehicle as described.7 Mice were sacrificed 12 hours after the final injection and processed for histology and FACS.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least 3 times independently. Values represent mean ± standard deviation or standard error of mean as indicated. Differences between groups were determined using an unpaired Student's t test (2-tailed), with a significance cutoff of P < .05. Analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

Prospective Isolation of Colon Crypt Subregions by Multicolor FACS

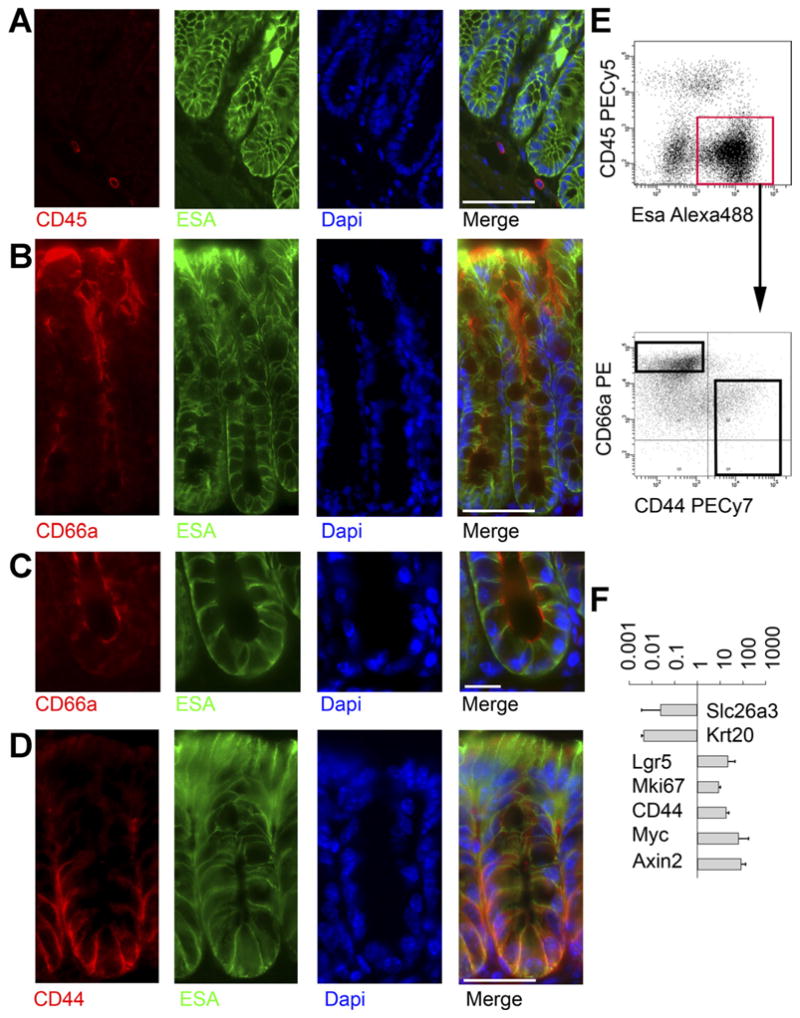

In order to establish a panel of surface antibodies that could isolate different colonic crypt subregions from dissociated colon by multicolor flow cytometry, we first conducted immunostaining on fixed murine colon. Immunofluorescence with the pan-epithelial marker Esa/EpCAM and the hematopoietic marker CD45 shows that Esa labels the colonic epithelium, while CD45 labels a distinct nonepithelial, presumably hematopoietic, population (Figure 1A). In the epithelium, CEACAM1/CD66a stains apical membranes of nearly all cells throughout the crypt, but is strongest at the crypt top (Figure 1B and C).13,16 CD44 marks basolateral membranes of the crypt base (Figure 1D). Thus, CD44 and CD66a label colon crypts in opposing gradients, as in human colon.13

Figure 1.

Prospective FACS separation of colonic crypt subregions. (A) Mouse colon stained for CD45 (red), ESA(green), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) shows that CD45 and ESA stain distinct cells. Scale bar: 50 uM. (B) Staining for CD66a (red), ESA/EpCAM (green), and DAPI (blue) shows a gradient of colonic CD66a expression, with the strongest staining on apical membranes near the lumen. Scale bar: 50 uM. (C) Higher magnification view of crypt base stained for CD66a (red), ESA green), and DAPI (blue) shows CD66a is present at the crypt base. Scale bar: 25 uM. (D) Staining for CD44 (red), ESA green), and DAPI (blue) shows a gradient of CD44, with the strongest staining at the crypt base along basolateral membranes. Scale bar: 50 uM. (E) FACS plot of ESA vs CD45 enables gating on epithelial cells (red box), which are then plotted for CD44 vs CD66a, showing the gradients predicted by immunofluorescence. (F) After sorting cells from the black boxes in (E), RNA was isolated for gene expression analysis. Relative expression (CD44+CD66alow/neg/CD44− CD66ahigh) of genes known to mark the crypt top or bottom is shown. Data are expressed as mean fold-change ± standard deviation. n = 3.

FACS on dissociated colon cells with Esa and CD45 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure 1E) demonstrates the following populations: ESA+CD45− epithelial cells, ES-A−CD45+ hematopoietic cells, and ESA−CD45− nonepithelial nonhematopoietic (stromal) cells. To separate the immature cells of the crypt base from the mature cells of the crypt top, we gated on ESA+ epithelial cells and isolated messenger RNA from FACS-sorted CD44+ CD66alow/neg and CD44−CD66ahigh cells (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure 1E) and compared gene expression using qRT-PCR. The CD44+CD66alow/neg population is enriched for genes known to be up-regulated at the crypt base, including Lgr5, Mki67, CD44, Myc, and Axin2,3,17 and CD44−CD66ahigh cells are enriched for genes known to be more abundant in the crypt top, such as Slc26a3 and Krt2018,19 (Figure 1F). As predicted by this analysis and the published literature,19 mKi67 staining is enriched in the crypt base (Supplementary Figure 2).

Single-Cell Gene Expression Profiling of Colon Epithelium

We next wished to rapidly and more fully define different colon crypt subpopulations at high (single-cell) resolution to determine if a colonic Paneth-like cell could be found. To do this, we paired flow cytometry with a microfluidic platform that reliably performs qRT-PCR on minute amounts of RNA and simultaneously measures up to 96 genes per cell. Such systems have been successfully used for single-cell transcriptional analysis.13,20 We profiled double-sorted (>95% purity) CD44+CD66alow/neg (crypt base) epithelial cells and CD44−CD66ahigh (crypt top) epithelial cells (Figures 1E and 2A, and Supplementary Figure 1), selecting genes from the literature and our own gene expression data. Hierarchical clustering was performed to group cells according to the similarity of their gene expression.13

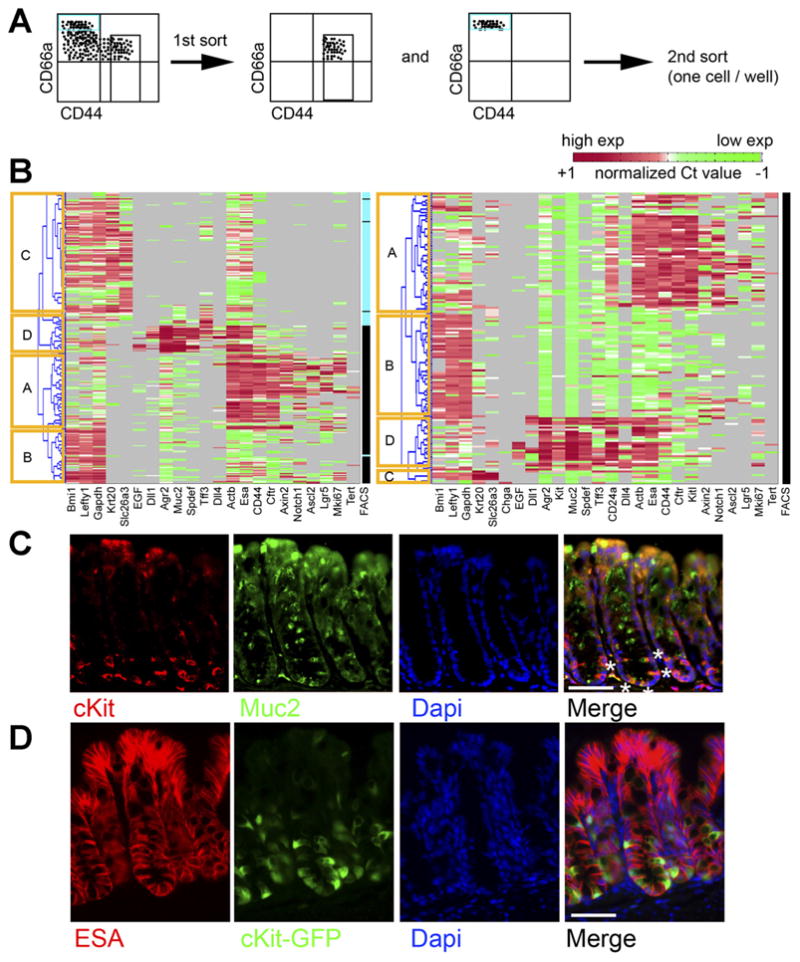

Figure 2.

Single-cell gene expression analysis of sorted colonic crypt subregions reveals distinct transcriptional states. (A) Experimental schema. Crypt base (Esa+CD45−CD44+CD66alow/neg) and crypt top (Esa+CD45− CD44−CD66ahigh) FACS-sorted colonic cells were sorted as shown. (B) Each row indicates a single cell, and each column indicates a gene. Red indicates high expression (normalized Ct < mean), green indicates low expression (normalized Ct > mean). Gray indicates no expression. Columns labeled “FACS” indicate sorted phenotype (black, CD44+ CD66alow/neg; blue, CD44− CD66ahigh). Hierarchical clustering reveals distinct clusters, labeled as (A–D)(yellow boxes). Two separate experiments are shown. (C) Staining colon for cKit (red) and Muc2 (green) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) shows a subset of Muc2+ cells at the crypt base are cKit+. White asterisks on one crypt highlight this in the merge panel. (D) Staining colon from cKit-GFP reporter mice with Esa (red) and DAPI (blue) shows GFP+(green) epithelial cells. Scale bars: 50 uM.

Multiple iterations (>4) revealed 4 major clusters, arbitrarily named clusters A–D, representing different cell types and/or transcriptional states (Figure 2B). These clusters were observed in all experiments. Although single-cell measurements of gene expression are inherently noisy,21,22 and some heterogeneity was seen in each cluster, clear patterns emerged.

Cluster A (mainly CD44+CD66alow/neg, ie, crypt base) contains nearly all of the cells expressing high levels of Lgr5 and thus represents a stem cell cluster. These cells express genes known to be differentially expressed in Lgr5high cells, including Axin2, Ascl2, Notch1, MKi67, and Tert.17,23 They also express high levels of Esa, Actb, and CFTR (Figure 2B).

Cluster B (mainly CD44+CD66alow/neg) expresses high levels of Bmi1, Lefty1, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; however, these transcripts are not unique to this cluster. Cluster B is more notable for what it lacks, that is, high levels of Lgr5-associated transcripts; high expression of goblet cell markers, such as Muc2 and Spdef; the enteroendocrine marker Chga; and high expression of mature enterocyte markers, such as Krt20 and Slc26a3.

Cluster C (CD44−CD66ahigh, ie, top of the crypt) shows high expression of Krt20 and Slc26a3, genes enriched in mature enterocytes that are expressed at the top of the crypt. These cells also lack high expression of goblet and stem cell markers.

Finally, cluster D (both CD44+CD66alow/neg and CD44−CD66ahigh) is enriched for goblet cells, because it is characterized by high expression of goblet cell transcripts, including Muc2,24 Tff3, Spdef (required for goblet and Paneth cell maturation),25,26 and Agr2 (required for Muc2 production).27 Overall, this single-cell transcriptional profiling validated our analysis of bulk-sorted cells (Figure 1F), confirmed that Lgr5+ cells are confined to the CD44+ fraction, and agreed with immunostaining (Figure 1A–D and Supplementary Figure 2).

Interestingly, we noted that some cluster D cells in the crypt base express EGF and the Notch ligands Dll1 and Dll4 (Figure 2B), factors that signal to Lgr5 cells8 and are enriched in Paneth cells.6 We profiled more goblet cells and again saw this subset (Supplementary Figure 3). We hypothesized that these cells might contribute to the niche for colonic Lgr5 cells, and we sought to study them further.

Identification of a cKit+ Goblet Cell Subset

To find additional surface markers that could enrich for these cells, we screened several genes/markers by single-cell analysis and also by multicolor flow cytometry with commercially available antibodies. Interestingly, we observed that cKit/CD117 was highly expressed in crypt base goblet cells (Figure 2B) at the single-cell level. To validate this, we co-stained colon with antibodies to cKit and Muc2 and found that many Muc2+ cells in the bottom third of the crypt are cKit+ (Figure 2C), agreeing with our single-cell analysis. Imaging colon sections from cKit-GFP reporter mice14 and staining for Esa also showed cKit+ crypt base epithelial cells in the bottom one third of the crypt (Figure 2D).

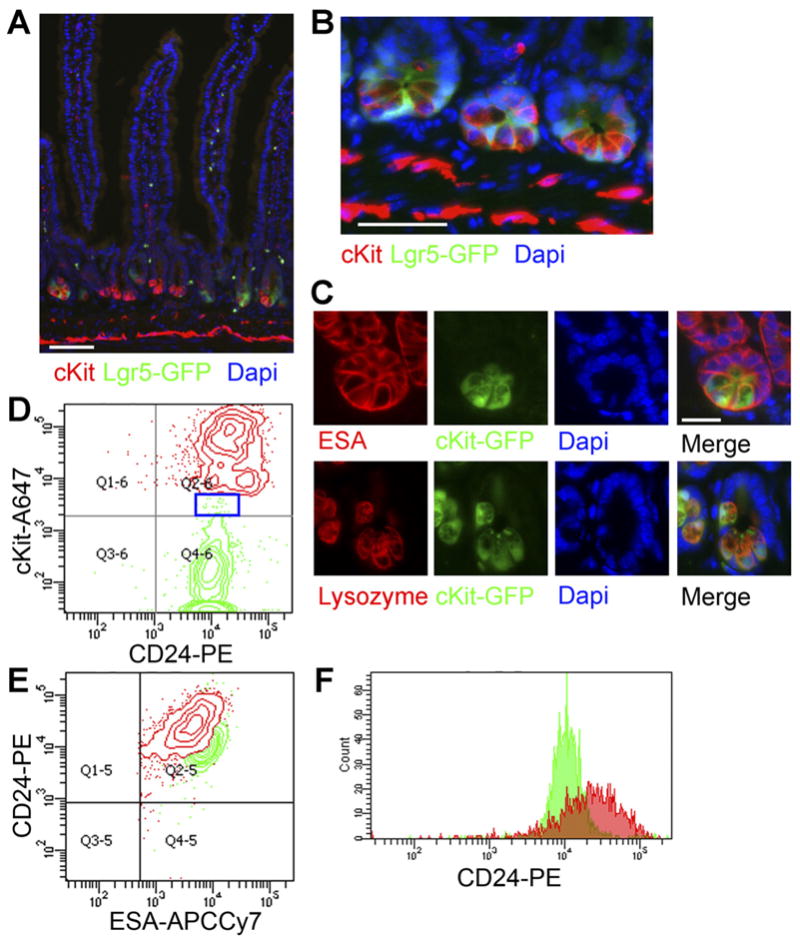

To determine whether cKit also marks Paneth cells, we stained Lgr5-GFP small intestine for cKit. We observed clear Paneth cell labeling with cKit+ cells interspersed between Lgr5+ cells (Figure 3A and B). (We also observed cKit labeling of nonepithelial cells, likely enteric nervous system cells and mast cells.28,29) Small intestine from cKit-GFP reporter mice also showed GFP+ Paneth cells that stained positive for Lysozyme and contained apical cytoplasmic granules (Figure 3C). FACS on dissociated Lgr5-GFP small intestinal epithelium (ESA+CD45−) showed that Lgr5+ cells (2.9% of Esa+CD45−) and cKit+ cells (2.4% of Esa+CD45−) are generally distinct and exhibit different levels of CD24 (Figure 3D–F) with cKit+ Paneth cells being strongly positive for CD24, in agreement with previous work.6 Thus, cKit marks Paneth cells. Of note, a small fraction of Lgr5GFP+ cells (<1%) stained weakly positive for cKit (Figure 3D, blue box). Presuming they are not doublets, a FACS artifact, or a result of GFP perdurance, these cells could represent a tiny but distinct subset of Lgr5+ cells or could be stem cells transitioning to a Paneth cell fate.

Figure 3.

cKit/CD117 marks Paneth cells. (A) Low and (B) high magnification views of Lgr5GFP small-intestine shows cKit expression (red) in Paneth cells interspersed between Lgr5+ cells (green). Nuclei are stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). Stromal cKit immunoreactivity is also seen. Scale bars: 50 uM. (C) Small-intestinal crypts from cKit-GFP reporter mice stained for Esa (red, top row) or Lysozyme (red, bottom row) and 4′,6-di-amidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) show Paneth cell (green) signal. Scale bar: 25 uM. (D) A FACS plot of Lgr5GFP+ cells (ESA+CD45−Lgr5GFP+, green, 2.9% of epithelial cells) and cKit+ cells (ESA+CD45−cKit+, red, 2.4% of epithelial cells) reinforces that the populations are distinct and CD24+. Blue box shows rare Lgr5GFP+cKit+ cells. (E) A plot of the same cells from (C) shows that the cKit+ cells have higher CD24 mean fluorescence. (F) A histogram of CD24 further demonstrates that cKit+ epithelial cells (red) exhibit higher CD24 mean fluorescence than Lgr5GFP cells (green).

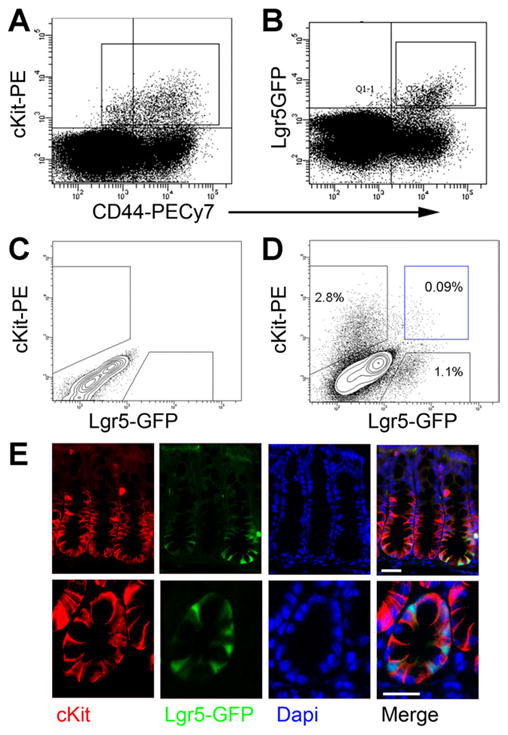

FACS on dissociated colonic epithelial cells from Lgr5-GFP mice shows that both cKit+ (2.1% of Esa+CD45−) and Lgr5GFP+ cells (1.1% of Esa+CD45−) are predominantly CD44+ (Figure 4A and B), consistent with immunostaining and single-cell PCR. As in small intestine, they are generally distinct populations (Figure 4C and D). Staining Lgr5-GFP colon for cKit shows cKit+ cells interdigitated between Lgr5-GFP+ cells, much like small intestinal Paneth cells (Figure 4E). Thus, cKit marks a subset of colonic goblet cells at the crypt base adjacent to Lgr5+ stem cells.

Figure 4.

Lgr5 and cKit label distinct populations in the colon. (A, B) FACS plots of colonic epithelial (Esa+CD45−) cells from an Lgr5-GFP mouse show that cKit+ cells (box in [A], 2.1% of epithelial cells) and GFP+ cells (box in [B], 1.1% of epithelial cells) are mostly CD44+. (C) Wild-type colonic epithelial cells were used to define positive-staining cells in (D). (D) A FACS plot of colonic epithelial cells from an Lgr5-GFP mouse shows distinct cKit+ and Lgr5-GFP populations. Rare (<0.1% of Esa+CD45−) double-positive cells are seen (blue box). (E) Immunostaining Lgr5-GFP colon for cKit (red) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) shown at low (top) and high (bottom) magnification. cKit+ cells interdigitate between Lgr5+(green) cells. Scale bars: 25 uM.

We do reproducibly observe a rare double-positive population (Lgr5+cKit+) that comprises <0.1% of epithelial cells by FACS (Figure 4D). As in small intestine, barring methodological explanations (eg, doublets or FACS artifacts), these cells could represent a small subset (<10%) of Lgr5+ cells or could be cells transitioning from a stem/progenitor state to a goblet cell fate. Of note, single-cell gene expression analysis does show cells in cluster A (Lgr5+ cells) with low levels of cKit transcript; however, we did not reproducibly detect cells in cluster D exhibiting high levels of both cKit and Lgr5 (Figure 2B).

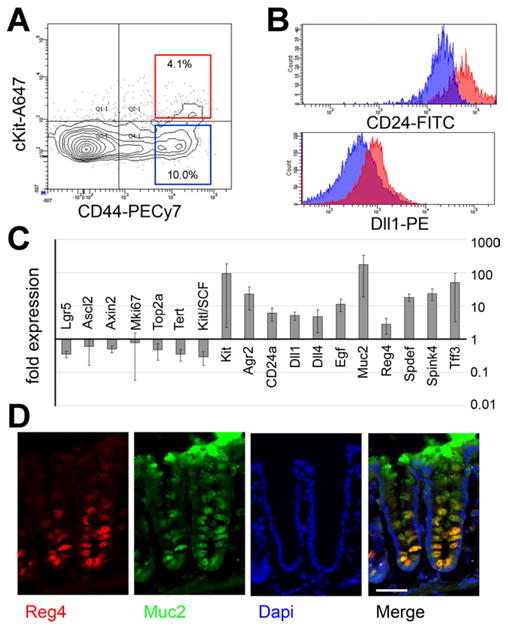

We next further characterized the cKit+ colonic epithelial cells by FACS and conventional qRT-PCR. Compared to their cKit−CD44+ neighbors, cKit+ crypt base cells show higher mean fluorescence for CD24 and Dll1 (Figure 5A and B), much like Paneth cells.6 When the bulk gene expression of those populations is analyzed by qRT-PCR, we find that CD44+cKit+ cells differentially express high levels of cKit messenger RNA (an internal control for our FACS), as well as Muc2, Agr2, Tff3, Spink4, Spdef, CD24, Dll1, Dll4, EGF, and Reg4 (Figure 5C). Reg4 is a factor that is mitogenic for colon cancer cell lines and protects intestinal mucosa from radiation-induced injury.30 We confirmed by immunofluorescence that Reg4 is expressed in colonic Muc2+ crypt base cells (Figure 5D). Transcripts differentially expressed in the CD44+cKit− population included stem/progenitor associated transcripts: Lgr5, Ascl2, Axin2, Mki67, Topoisomerase-2a, and Tert. These data are consistent with our single-cell analysis (Figure 2) and further show that cKit marks crypt base EGF+Dll1+Dll4+ goblet cells. Also, the CD44+cKit− population differentially expresses Kit ligand/stem cell factor, suggesting that Lgr5+ cells may signal to adjacent cKit+ cells through Kit ligand. Both the secreted and membrane-bound isoforms of Kitl/stem cell factor31 are detected in FACS-isolated Lgr5-GFP colonic cells (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 5.

cKit labels crypt base goblet cells. (A) A FACS plot of colonic epithelial cells (Esa+CD45−) shows that cKit+ cells (red box, 4.1% of cells) are mostly CD44+, consistent with immunofluorescence. (B) Comparing cKit+CD44+ cells (redbox[A]) to cKit−CD44+ cells (blue box[A], ∼10% of cells), shows that the cKit+ population exhibits brighter mean fluorescence for CD24 and Dll1. (C) qRT-PCR on FACS-sorted cKit+CD44+ and cKit−CD44+ cells for indicated genes. Data are expressed as mean fold-change ± standard deviation. n = 3. (D) Immunostaining for Muc2 (green), Reg4 (red), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) shows that Reg4 is expressed in crypt base goblet cells. Scale bar: 50 uM.

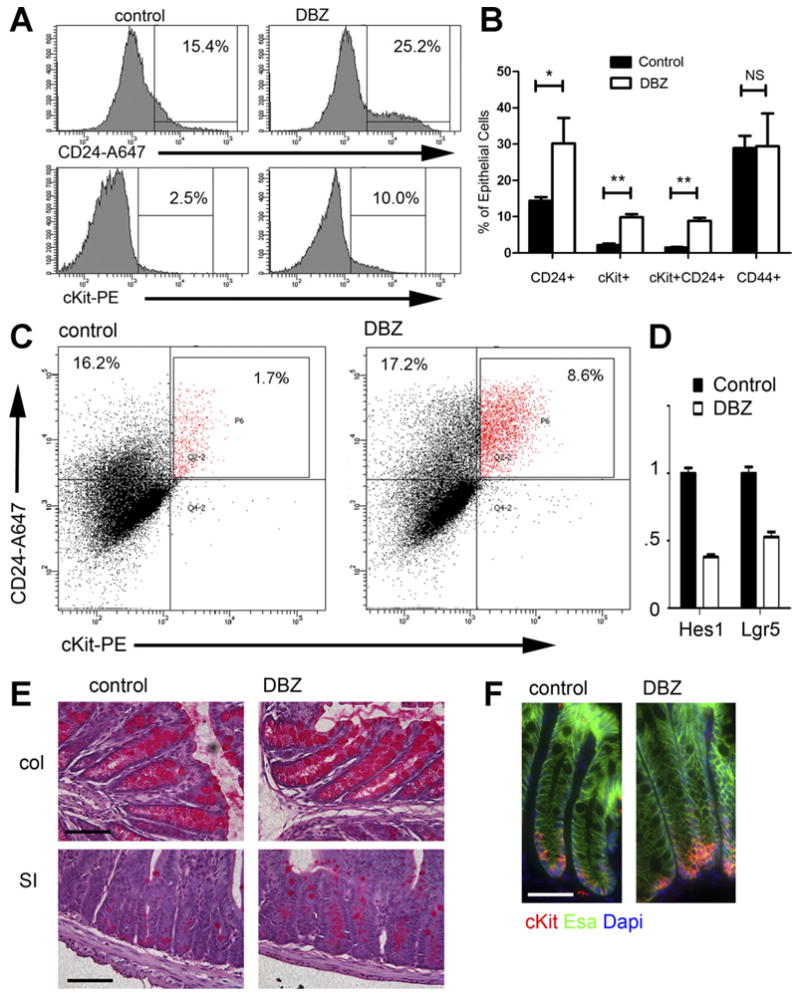

Because cKit marks a subset of goblet cells, and because blocking Notch signaling regulates different small-intestinal crypt base populations and leads to secretory cell hyperplasia,11 we wished to know whether inhibiting Notch signaling would cause a relative increase in colonic cKit+ epithelial cells. We administered a potent γ-secretase inhibitor, DBZ, or vehicle control to adult mice and performed FACS analysis of colonic epithelial cells. We noted a significant increase in the fraction of CD24+ and cKit+ and CD24+cKit+ epithelial cells (Figure 6A and B); however, CD44+ cells were unchanged. Most of the change in CD24 levels was driven by the CD24+cKit+ cells, since the fraction of CD24+cKit− epithelial cells in DBZ vs vehicle control was similar (Figure 6C). We confirmed by qRT-PCR on bulk colon that Notch signaling was significantly reduced in DBZ-treated mice, as indicated by the downstream Notch target gene Hes1 (Figure 6D). In agreement with published data,32 Lgr5 levels also were lower in DBZ-treated mice (Figure 6D). Periodic acid-Schiff staining of DBZ and control small intestine and colon showed the predicted increase in mucin-containing cells at the crypt base (Figure 6E). Also, immunostaining colon for cKit showed an increase in crypt base cKit+ epithelial cells in DBZ-treated mice (Figure 6F). The prevalence of crypt base cKit+ goblet cells is regulated by Notch signaling.

Figure 6.

Blocking Notch signaling increases cKit+ cells. (A) FACS histograms of epithelial (Esa+CD45−) cells from representative control and DBZ-treated mice show an increase in CD24 and cKit. (B) The percent of epithelial (Esa+CD45−) cells staining for different surface markers (x-axis) in control and DBZ-treated mice is plotted, showing an increase in cKit+ cells, CD24+ cells, and cKit+CD24+ cells. No increase in CD44+ cells was seen. n = 4 per group. *P < .005; **P < .001; NS, not significant, P > .05. (C) FACS plot of CD24 vs cKit for epithelial cells from representative control and DBZ-treated mice illustrates the large increase in CD24+cKit+ epithelial cells. (D) qRT-PCR on RNA isolated from control and DBZ colon showed the expected decrease in Lgr5 and Hes1. n = 4 samples per group. P < .05. (E) Periodic acid-Schiff stains of colon (top) and small intestine (bottom) from representative control and DBZ mice shows hyperplasia of mucin-containing secretory cells with DBZ treatment. (F) Immunostaining of control and DBZ-treated colon for cKit (red), Esa (green), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) shows an increase in crypt base cKit+ cells. Scale bars in (E, F): 50 uM.

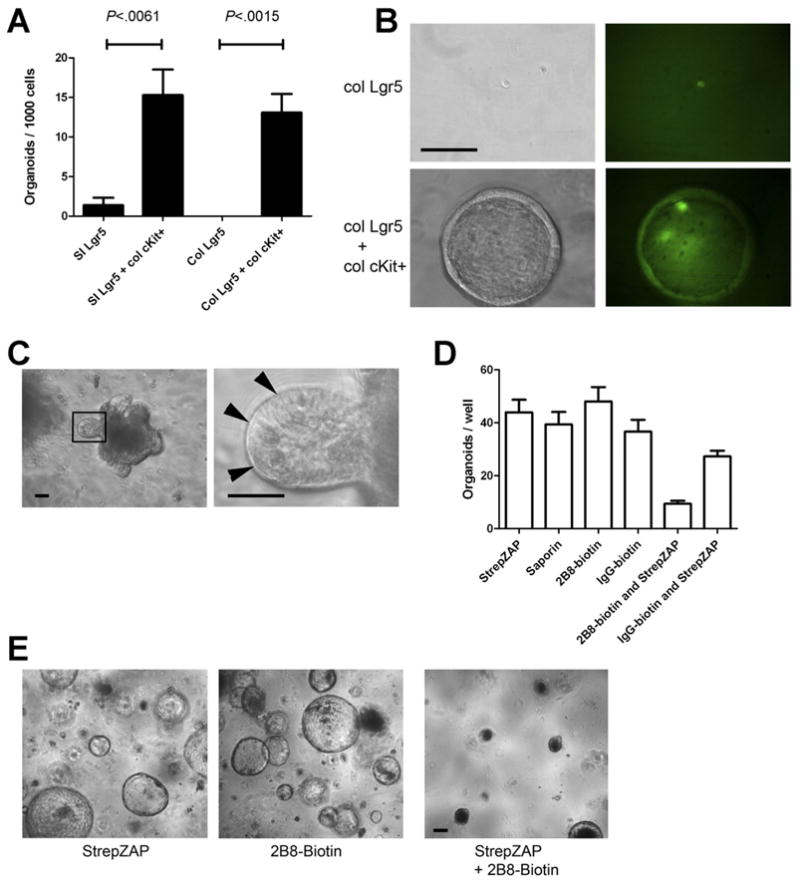

cKit+ Goblet Cells Support Organoid Formation

To ask whether colonic cKit+ epithelial cells could functionally support Lgr5+ stem cells, we FACS-isolated Lgr5GFP+ small intestinal and colonic stem cells and cultured them in the absence or presence of FACS-isolated cKit+ colonic epithelial cells. Sorted small intestinal Lgr5GFP+ singlets grown alone generated organoids at a low frequency (1.4 organoids per 1000 sorted cells). Colonic Lgr5GFP+ singlets did not form organoids. However, when small intestinal or colonic Lgr5+ cells were cultured together with colonic cKit+CD44+ cells in a 1:1 ratio, we observed a large increase in small intestinal (11-fold; P = .0061) organoid formation, and a qualitative difference in colonic organoid formation when assayed 7 days post plating (Figure 7A and B). cKit+CD44+ cells did not form organoids. Colonic organoids were hollow spheroids that showed uniform GFP signal. However, as no exogenous Wnt was added, these organoids stopped growing and could not be passaged, consistent with published reports.5

Figure 7.

cKit+ cells promote organoid formation of Lgr5+ cells. (A) Lgr5-GFP+ cells were FACS isolated from the proximal small intestine or colon and were cultured alone, with FACS-sorted colonic cKit+CD44+ epithelial cells, or with cKit−CD44− epithelial cells. Organoids were scored 7 days after plating. Histogram shows organoids per 1000 FACS-sorted cells. n = 3. P values indicated. Error bars indicate standard error of mean. (B) Representative images at 1 week post plating from Lgr5-GFP colonic cells grown alone (top rows) or with CD44+cKit+ colonic cells (bottom rows). Left column shows phase contrast images, and right shows GFP. (C) Primary small intestinal organoids (left) contained visible Paneth cells (right). (D) Organoids shown in (C) were passaged by dissociation into a single-cell suspension and were treated as shown. StrepZAP is streptavidin-saporin conjugate. n = 3. (E) Representative images from (D) are shown. Images acquired 7 days after passaging. Scale bars: 50 uM.

We asked whether targeted depletion of cKit+ cells from organoids using a specific anti-cKit-conjugated toxin would reduce organoid formation. To do this, we used streptavidin-conjugated saporin, a 30-kDa protein that inactivates ribosomes of cells that internalize it.33. In cKit+ mast cells, cKit is constitutively internalized from the cell surface,34 so we hypothesized that this approach would target cKit+ intestinal cells. We targeted saporin to cKit+ cells using biotinylated-2B8, a monoclonal anti-cKit antibody that does not block cKit signaling.35 We dissociated small intestinal organoids with visible Paneth cells (Figure 7C) into a single-cell suspension and exposed them to streptavidin-saporin, biotinylated-2B8, biotinylated rat IgG isotype control, or either biotinylated antibody with streptavididin-saporin. The combination of biotinylated-2B8 and streptavidin-saporin led to a marked decrease in organoid formation (Figure 7D and E). Although we cannot exclude a bystander effect or the formal possibility that the effect was due to loss of rare cKit+Lgr5+ cells, the percentage of such cells is quite low (<10% of Lgr5+ cells) and therefore this seems unlikely.

Discussion

We have characterized the steady-state murine colonic epithelium at single-cell resolution using widely available surface markers and highly multiplexed qRT- PCR. Our analysis demonstrated the following 4 major cell subtypes or transcriptional states from the top and bottom of the crypt: cluster A (containing Lgr5+ cells), cluster B (which lacks markers of the other known cell types but does not exhibit any unique marker), cluster C (mature enterocytes), and cluster D (goblet cells). Cluster B may contain immature enterocytes because it loosely resembles cluster C and is enriched at the crypt base; however, it expresses MKi67, and thus could also contain transit amplifying cells. Currently, without a unique marker for FACS sorting, additional study of cluster B is difficult. Of note, rare differentiated cell types, such as enteroendocrine cells (marked by chromogranin A) were not seen in significant numbers in the populations we profiled. Additional surface markers that enrich for them would facilitate their characterization. Future studies of crypt regions not analyzed here may reveal other cell types or transcriptional states.

In a parallel single-cell characterization of normal human colon using EpCAM/ESA, CD44, and CD66a,13 we recently observed a remarkably similar spatial organization of surface markers in the crypt and also transcriptional clusters that closely mirror the murine colon. For example, like murine cluster A, an EpCAM+ CD44+CD66a− cluster in human colon expresses high levels of Lgr5, Ascl2, Notch1, and CFTR. Of note, with recent advances in culture conditions, it was shown that human colon cells that possess the capacity to generate self-renewing organoids express high levels of Lgr5.4 Similarly as in mouse, in human colon, Slc26a3 and Krt20 are highly expressed together in an EpCAM+CD44−CD66a+ cluster. Such observations reinforce the idea that many molecular cues governing colonic epithelial homeostasis have been highly conserved.

Interestingly, we found a subset of crypt-base goblet cells expressing high levels of Dll1, Dll4, and EGF, much like Paneth cells. These cells also express cKit/CD117, as do Paneth cells. Functionally, these cells promote the ability of Lgr5+ stem cells to form organoids. In many ways, these cKit+ goblet cells are similar to Paneth cells. Both colonic cKit+ goblet cells and Paneth cells are interdigitated between (and likely directly contacting) Lgr5+ stem cells. Both are cKit+ and may respond to cKit-ligand/stem cell factor from adjacent Lgr5+ cells. They also express several factors important for crypt homeostasis (eg, EGF, Dll1, and Dll4), as well as Muc2, Spdef, and Defensins (data not shown). Given the striking similarities between murine and human colon, we predict that similar niche cells exist in human colon. Indeed, human crypt base goblet cells express Dll1 and Dll4.13 More extensive gene expression studies will likely reveal additional secreted factors made by cKit+ crypt base cells, and might also help determine whether they secrete other factors implicated in crypt homeostasis, such as Wnt activators.

The prevalence of cKit+ colonic epithelial cells is regulated by Notch signaling because administration of DBZ, a potent γ-secretase inhibitor, expands cKit+ cell numbers. DBZ also caused a decrease in Lgr5 expression. Many earlier studies have also shown that Notch inhibition causes secretory cell hyperplasia and a loss of Lgr5.11,32 Because we observed some Notch1 expression in all 4 major crypt base clusters (Figure 2), we cannot currently ascertain whether the DBZ pheno-type is cell autonomous within cKit+ cells or nonautonomous/indirect. In the small intestine, Paneth cell numbers appear to regulate Lgr5+ stem cell numbers.6 A similar regulation could also occur in the colon.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. FACS gating strategy for isolation of colonic crypt subregions.

In the first 3 plots (top row), we exclude debris and doublets by sequentially gating on FSC-A vs. SSC-A, then FSC-W vs. FSC-H, and then SSC-H vs. SSC-W. Live single cells (box in Dapi vs FSC-A plot) are then plotted for Esa vs. CD45, which shows three major populations: hematopoietic Esa-CD45+ cells, stromal Esa-CD45− cells, and epithelial Esa+CD45− cells (box). Epithelial cells represent approximately half (45–60%) of all live single cells. These are next plotted on a CD44 vs. CD66a plot to separate crypt top (blue) from crypt bottom (red) cells. A population hierarchy is shown (lower right). Gating was done with FacsDiva software.

Supplementary Table 1. Taqman Assays used for Single Cell and Conventional qPCR Gene Expression Analysis

Supplementary Table 2. Antibodies used in immunostaining

Supplementary Figure 2. MKi67 staining of adult mouse colon.

Immunostaining for MKi67 (green) and Dapi (blue) shows that proliferating cells are confined to the lower half of the crypts, consistent with published work and with our single cell profiling in Figure 2. Scale bar: 50 uM.

Supplementary Figure 3. Single cell transcriptional profiling of Goblet Cells.

In this experiment, crypt base epithelial cells were analyzed by single cell gene expression analysis as described. A histogram of Muc2 expression (top) shows 3 populations: Muc2 non-expressing cells (Ct = 40), Muc2 low cells (dark blue peak), and Muc2 high cells, i.e., goblet cells (red peak, enclosed in light blue box). The Ct cutoff for Muc2 high cells was 16.5. Nearly all cells express high levels of Agr2, which is required for Muc2 production. Hierarchical clustering shows a subpopulation of EGF+Dll1 + goblet cells (yellow box), as seen in Figure 2. They also express high levels of Dll4, Esa, CD24, and Spdef. cKit was not included in this experiment.

Supplementary Figure 4. Expression of secreted and transmembrane cKit isoforms in Lgr5+ colon cells.

RT-PCR on total mouse colon (lane 2) and FACS-sorted Lgr5-GFP+ cells (lane 3) for membrane-bound (arrow, ∼910 bp) and secreted (arrowhead, ∼830bp) cKit isoforms shows that both are detected. Lane 1 is 1 kB DNA ladder.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jenny Roost, Anson Lowe, Shaheen Sikandar, Pushcar Joshi, Agnieszka Czechowicz, Irv Weissman, Shang Cai, Maddalena Adorno, Maider Zabala, Ken Weinberg, and Maheswaran Mani for helpful discussions and comments.

Funding: MER has been supported by a California Institute for Regenerative Medicine MD Trainee Award, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Working Group GI Fellows Research Award, National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32 DK0070560, and a Stanford NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Digestive Disease Center Pilot/Feasibility Award 5P30DK056339. MFC is supported by 5P01CA139490-03.

Abbreviations in this paper

- DBZ

dibenzazepine

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PBS-T

PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100

- PE

phycoerythrin

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: This author discloses the following: Stephen R. Quake is a founder, consultant, and shareholder of Fluidigm Corporation. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Supplementary Material: Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.006.

References

- 1.Chang WW, Leblond CP. Renewal of the epithelium in the descending colon of the mouse. I. Presence of three cell populations: vacuolated-columnar, mucous and argentaffin. Am J Anat. 1971;131:73–99. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001310105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsubouchi S, Leblond CP. Migration and turnover of entero-endocrine and caveolated cells in the epithelium of the descending colon, as shown by radioautography after continuous infusion of 3H-thymidine into mice. Am J Anat. 1979;156:431–51. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001560403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung P, Sato T, Merlos-Suarez A, et al. Isolation and in vitro expansion of human colonic stem cells. Nat Med. 2011;17:1225–1227. doi: 10.1038/nm.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett's epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Es JH, van Gijn ME, Riccio O, et al. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrinet L, Rodilla V, Liu Z, et al. Dll1- and dll4-mediated notch signaling are required for homeostasis of intestinal stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1230–1240. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.005. e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Troyer KL, Luetteke NC, Saxon ML, et al. Growth retardation, duodenal lesions, and aberrant ileum architecture in triple null mice lacking EGF, amphiregulin, and TGF-alpha. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:68–78. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhnert F, Davis CR, Wang HT, et al. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536800100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vooijs M, Liu Z, Kopan R. Notch: architect, landscaper, and guardian of the intestine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:448–459. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altmann GG. Morphological observations on mucus-secreting non-goblet cells in the deep crypts of the rat ascending colon. Am J Anat. 1983;167:95–117. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001670109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalerba P, Kalisky T, Sahoo D, et al. Single-cell dissection of transcriptional heterogeneity in human colon tumors. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1120–1127. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, et al. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frangsmyr L, Baranov V, Prall F, et al. Cell- and region-specific expression of biliary glycoprotein and its messenger RNA in normal human colonic mucosa. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2963–2967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Flier LG, van Gijn ME, Hatzis P, et al. Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell. 2009;136:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byeon MK, Westerman MA, Maroulakou IG, et al. The down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) gene encodes an intestine-specific membrane glycoprotein. Oncogene. 1996;12:387–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiao YF, Nakamura S, Sugai T, et al. Serrated adenoma of the colorectum undergoes a proliferation versus differentiation process: new conceptual interpretation of morphogenesis. Oncology. 2008;74:127–134. doi: 10.1159/000151359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo G, Huss M, Tong GQ, et al. Resolution of cell fate decisions revealed by single-cell gene expression analysis from zygote to blastocyst. Dev Cell. 2010;18:675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalerba P, Kalisky T, Sahoo D, et al. Single-cell dissection of transcriptional heterogeneity in human colon tumors. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1120–1127. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalisky T, Quake SR. Single-cell genomics. Nat Methods. 2011;8:311–314. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0411-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schepers AG, Vries R, van den Born M, et al. Lgr5 intestinal stem cells have high telomerase activity and randomly segregate their chromosomes. EMBO J. 2011;30:1104–1109. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang SK, Dohrman AF, Basbaum CB, et al. Localization of mucin (MUC2 and MUC3) messenger RNA and peptide expression in human normal intestine and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:28–36. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregorieff A, Stange DE, Kujala P, et al. The ets-domain transcription factor Spdef promotes maturation of goblet and paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1333–1345. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.044. e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sands BE, Podolsky DK. The trefoil peptide family. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:253–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park SW, Zhen G, Verhaeghe C, et al. The protein disulfide isomerase AGR2 is essential for production of intestinal mucus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6950–6955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808722106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda H, Yamagata A, Nishikawa S, et al. Requirement of c-kit for development of intestinal pacemaker system. Development. 1992;116:369–375. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nocka K, Majumder S, Chabot B, et al. Expression of c-kit gene products in known cellular targets of W mutations in normal and W mutant mice–evidence for an impaired c-kit kinase in mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1989;3:816–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bishnupuri KS, Luo Q, Sainathan SK, et al. Reg IV regulates normal intestinal and colorectal cancer cell susceptibility to radiation-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:616–626. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.050. 626 e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flanagan JG, Chan DC, Leder P. Transmembrane form of the kit ligand growth factor is determined by alternative splicing and is missing in the Sld mutant. Cell. 1991;64:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90326-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vandussen KL, Carulli AJ, Keeley TM, et al. Notch signaling modulates proliferation and differentiation of intestinal crypt base columnar stem cells. Development. 2011;139:488–497. doi: 10.1242/dev.070763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorpe PE, Brown AN, Bremner JA, Jr, et al. An immunotoxin composed of monoclonal anti-Thy 1.1 antibody and a ribosome-inactivating protein from Saponaria officinalis: potent antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babina M, Rex C, Guhl S, et al. Baseline and stimulated turnover of cell surface c-Kit expression in different types of human mast cells. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:530–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikuta K, Weissman IL. Evidence that hematopoietic stem cells express mouse c-kit but do not depend on steel factor for their generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1502–1506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. FACS gating strategy for isolation of colonic crypt subregions.

In the first 3 plots (top row), we exclude debris and doublets by sequentially gating on FSC-A vs. SSC-A, then FSC-W vs. FSC-H, and then SSC-H vs. SSC-W. Live single cells (box in Dapi vs FSC-A plot) are then plotted for Esa vs. CD45, which shows three major populations: hematopoietic Esa-CD45+ cells, stromal Esa-CD45− cells, and epithelial Esa+CD45− cells (box). Epithelial cells represent approximately half (45–60%) of all live single cells. These are next plotted on a CD44 vs. CD66a plot to separate crypt top (blue) from crypt bottom (red) cells. A population hierarchy is shown (lower right). Gating was done with FacsDiva software.

Supplementary Table 1. Taqman Assays used for Single Cell and Conventional qPCR Gene Expression Analysis

Supplementary Table 2. Antibodies used in immunostaining

Supplementary Figure 2. MKi67 staining of adult mouse colon.

Immunostaining for MKi67 (green) and Dapi (blue) shows that proliferating cells are confined to the lower half of the crypts, consistent with published work and with our single cell profiling in Figure 2. Scale bar: 50 uM.

Supplementary Figure 3. Single cell transcriptional profiling of Goblet Cells.

In this experiment, crypt base epithelial cells were analyzed by single cell gene expression analysis as described. A histogram of Muc2 expression (top) shows 3 populations: Muc2 non-expressing cells (Ct = 40), Muc2 low cells (dark blue peak), and Muc2 high cells, i.e., goblet cells (red peak, enclosed in light blue box). The Ct cutoff for Muc2 high cells was 16.5. Nearly all cells express high levels of Agr2, which is required for Muc2 production. Hierarchical clustering shows a subpopulation of EGF+Dll1 + goblet cells (yellow box), as seen in Figure 2. They also express high levels of Dll4, Esa, CD24, and Spdef. cKit was not included in this experiment.

Supplementary Figure 4. Expression of secreted and transmembrane cKit isoforms in Lgr5+ colon cells.

RT-PCR on total mouse colon (lane 2) and FACS-sorted Lgr5-GFP+ cells (lane 3) for membrane-bound (arrow, ∼910 bp) and secreted (arrowhead, ∼830bp) cKit isoforms shows that both are detected. Lane 1 is 1 kB DNA ladder.