Abstract

Introduction

In the past two decades, childhood vaccination coverage has increased dramatically, averting an estimated 2–3 million deaths per year. Adult vaccination coverage, however, remains inconsistently recorded and substandard. Although structural barriers are known to limit coverage, social and psychological factors can also affect vaccine uptake. Previous qualitative studies have explored beliefs, attitudes and preferences associated with seasonal influenza (flu) vaccination uptake, yet little research has investigated how participants’ context and experiences influence their vaccination decision-making process over time. This paper aims to provide a detailed account of a mixed methods approach designed to understand the wider constellation of social and psychological factors likely to influence adult vaccination decisions, as well as the context in which these decisions take place, in the USA, the UK, France, India, China and Brazil.

Methods and analysis

We employ a combination of qualitative interviewing approaches to reach a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing vaccination decisions, specifically seasonal flu and tetanus. To elicit these factors, we developed the journey to vaccination, a new qualitative approach anchored on the heuristics and biases tradition and the customer journey mapping approach. A purposive sampling strategy is used to select participants who represent a range of key sociodemographic characteristics. Thematic analysis will be used to analyse the data. Typical journeys to vaccination will be proposed.

Ethics and dissemination

Vaccination uptake is significantly influenced by social and psychological factors, some of which are under-reported and poorly understood. This research will provide a deeper understanding of the barriers and drivers to adult vaccination. Our findings will be published in relevant peer-reviewed journals and presented at academic conferences. They will also be presented as practical recommendations at policy and industry meetings and healthcare professionals’ forums. This research was approved by relevant local ethics committees.

Keywords: Public Health, Qualitative Research, Infectious Diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The journey to vaccination, a multidisciplinary qualitative approach, is used to elicit underlying beliefs, attitudes and preferences affecting vaccination decisions.

A multinational and relevant sample population will be recruited.

The interview schedules and local interviewers’ training are standardised, which will enable data comparability.

Challenges in recruiting specific participant categories may be encountered and cross-cultural variations will need to be documented and explained.

Background

In the past two decades, childhood vaccination coverage has increased dramatically, averting an estimated 2–3 million deaths per year, along with myriad episodes of illness and disability.1 2 Adult vaccination coverage, however, remains poorly recorded and substandard.2 3

Two important adult routine vaccines are seasonal influenza (flu) and tetanus-containing vaccines.4 An annual flu vaccine is recommended to all adults, particularly those aged ≥65 years and under 65 years with certain medical conditions such as asthma, heart disease and diabetes. Despite this recommendation, in any given year, flu epidemics can cause between 500 000 and 1 000 000 deaths globally.5 A tetanus-containing booster is recommended every 10 years to prevent tetanus and other diseases such as pertussis, diphtheria and polio. Although tetanus morbidity and mortality is mostly neonatal and maternal, globally, an estimated 13 000 annual non-maternal adults deaths are due to tetanus infection.6 Moreover, it has been established that unvaccinated adolescents and adults, or those with waning immunity, have become a major source of pertussis infection for unvaccinated infants.7 The WHO estimated that, in 2008, 195 000 children under 5 years of age died from pertussis and 199 000 from flu, many of whom were infected by an adult.8

Although structural barriers, such as access to care and vaccine availability, are known to limit coverage, social and psychological factors can also affect vaccine uptake. For example, perceived susceptibility to flu and concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness have been shown to significantly influence vaccination behaviour.9 10 The relevance of these factors to vaccination decisions has become a focus of policy discussions, such that national and supranational immunisation advisory committees are now evaluating how to best measure confidence in vaccines to inform and evaluate future interventions.11

Making decisions about our own health in general, and vaccinations in particular, can be a difficult task. Typically, it involves navigating an often intricate healthcare system, discussing the issue with a healthcare professional (HCP), researching the Internet, consulting family members and peers and trying to make sense of all the available information, which is likely to be incomplete and conflicting.12 A key challenge in decision-making processes regarding health is weighing up the benefits of an intervention versus its potential harm. In the case of vaccinations, this process can be particularly complex as it often entails the assessment of several disease-related variables including severity, likelihood of catching the pathogen and susceptibility to it, as well as vaccine attributes such as effectiveness, side effects and safety, among others.13 Furthermore, the benefits and drawbacks of vaccines are normally conveyed in statistical terms, a language that has proven to be difficult to grasp for most people. For example, results from an experimental study showed that 16–20% of highly educated participants incorrectly answered relatively simple questions about risk magnitudes (eg, Which represents the larger risk: 1%, 5% or 10%?).14 It is, therefore, conceivable that a significantly larger proportion of less-educated individuals, who constitute a majority of the population, are likely to misunderstand this type of data.

A vast body of research has demonstrated that when people are unable to assess risk using statistical reasoning they often rely on heuristics, an experience-based and intuitive approach used to facilitate decision-making.15–17 Heuristics represent what psychologists have termed ‘cognitive shortcuts’; in other words, they allow an inference to be made regarding risk without going through numerous analytical calculations. By its very nature, the use of heuristics can be efficient and accurate in some occasions, but it can also lead to cognitive errors and flawed decision-making when used in circumstances that require thorough logical analysis.18 Furthermore, individuals’ judgement is often influenced by their context and personal or family experiences, whether these are conscious or not.19 Health decisions in general, and vaccination decisions in particular, can also be significantly influenced by patients’ trust in HCPs and the latter's ability to communicate risk effectively.20

Although qualitative studies have explored beliefs, attitudes and preferences associated with flu vaccination uptake, thus far, little research has investigated how participants’ own context and experiences influence their vaccination decision-making process over time.21–23 Furthermore, most studies focus on populations from developed countries; relevant evidence from developing countries is largely missing. Qualitative research on adult tetanus boosters is limited and focuses on neonatal tetanus.

This paper aims to provide a detailed account of a mixed method qualitative approach designed to understand the wider constellation of social and psychological factors likely to influence adult vaccination behaviour, and their relative importance, as well as the context in which these decisions take place. Our focus is on social influences, beliefs and attitudes affecting the uptake of seasonal flu vaccines and tetanus boosters, as these aspects have been found to be particularly influential in vaccination decision-making. Our research will be conducted in key developed and developing economies—the USA, the UK, France, India, China and Brazil.

Conceptual framework

Our research sits well within the constructivist (or interpretivist) paradigm, which is concerned with people's experiences from the perspective of those who live them, and whereby the researcher and participant ‘jointly create findings from their interactive dialogue and interpretation’.24 From an epistemological point of view, however, our position draws from constructivism and positivism, in that we recognise there is a degree of bias introduced by the researcher's experience when creating knowledge, but the researcher will endeavour to be objective and to elicit the participant's experience in an unprejudiced manner.25

The methodology of this study rests on two theoretical approaches: heuristics and biases, specifically the availability heuristic26 and customer journey mapping.27–29 We explain these below.

As mentioned in the previous section, people rely on a limited number of heuristics which reduce the complexity of calculating probabilities and predicting outcomes to simpler mental operations. A frequently used heuristic is availability, the tendency to make judgements about the frequency or probability of an event based on the ease with which a similar episode can be recalled.30 The use of this heuristic could yield accurate actions but it could also lead to erroneous decisions. For example, a high-risk individual may be prompted to have a flu vaccine after being exposed to extensive media coverage about one single flu-related death. The following season, he may decide not to have the flu vaccine due to a friend experiencing side effects (eg, flu-like symptoms) after receiving a flu vaccine. In both cases, his decision-making is determined by the ease with which the risks associated with flu or the flu vaccine spring to mind (which vary between the two seasons), as opposed to the statistical probability of experiencing either adverse effect (which may be constant across the two seasons). The first decision, however, is aligned with current vaccination recommendations, whereas the second is not.

In addition, it has been established that people's evaluation of the logical strength of an argument is often biased by their pre-existent belief in the truth or falsity of the conclusion.31 For example, if the same high-risk individual distrusts the medical establishment and the pharmaceutical industry and prefers alternative medicine instead, it is likely that the news about a flu-related death will have a lesser impact on his vaccination decision than his friend's reported side effects—due to mentally overweighting the adverse effects of the vaccine, which are consistent with his pre-existing beliefs. Importantly, belief-based decision-making need not be conscious.32 33 Thus, a decision based on intuition may be later postrationalised and explained using analytical-sounding arguments, when, in reality, cost–benefit analysis was not employed.

The customer journey mapping approach is commonly used in service design to capture and evaluate people's experience of different services. Although some elements may be more important than others, this approach considers the overall experience of the service user as the result of every element in a journey through a service. The customer journey mapping approach has been mainly used by the transport and tourism industries, yet it has also enabled health providers to improve their services by uncovering key areas which deserve attention and focus improvement efforts on such areas.34 Of particular note is the brand touchpoint wheel developed a decade ago by Dunn and Davies.35 They conceive the customer journey as a wheel comprising three main stages (prepurchase, purchase and postpurchase experience) and a number of touchpoints, which are key points at which the consumer interacts with a particular product or service (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

The brand touchpoint wheel. Source: Dunn and Davis.35

Our approach: journey to vaccination

Most qualitative studies in the field of vaccination decision-making have elicited barriers and enablers to vaccination using traditional methodological approaches such as explicit enquiry (eg, why did you vaccinate?) and indiscriminate use of probes, often within a focus group setting. A key shortcoming of these approaches is that the impact of individuals’ personal circumstances and past experiences on vaccination decisions over time is seldom explored. Thus, researchers may fail to notice participants’ tendency to fall back on readily available information and report postdecisional rationalisations of their behaviours rather than actual drivers.

In an effort to address these shortcomings, we developed a new qualitative approach which we call journey to vaccination. Anchored on the two complementary lines of thought described above and nested within the qualitative research tradition, journey to vaccination is a visual exercise in which the interviewer and the participant jointly build a timeline that captures salient events that lead the participant to get or not to get vaccinated. The exercise starts with a participant's latest flu or tetanus vaccination experience as an adult; it then extends backwards to the participant's first memory of such experience. The participant is asked to describe these events, which in turn allows the interviewer to indirectly elicit a range of factors that affected positively or negatively the decision to get vaccinated. Importantly, this exercise enables the participant to produce a personal historical narrative, through which vaccination decisions are discussed as a continuum and not in isolation from each other or from other important health-related or lifestyle-related decisions.

The journey to vaccination approach is designed to comprehensively capture psychological and also social influences on vaccination decisions. Participants are, therefore, asked to recall key actors who were involved in the vaccination process (eg, their family) and how they influenced the process. Emotional aspects of the decision-making are also explored and taken into account.

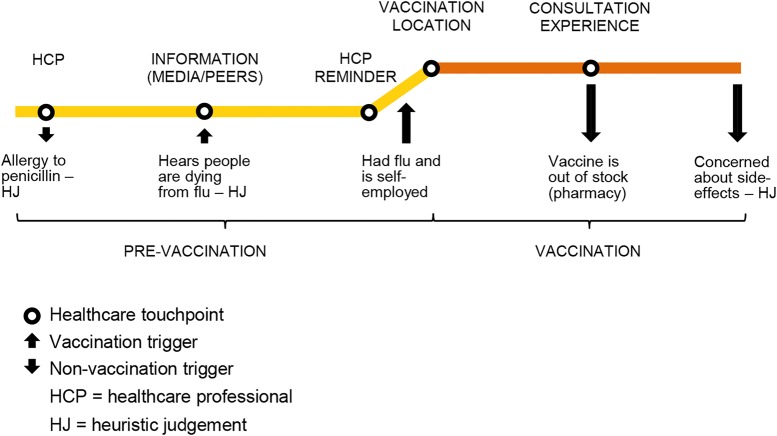

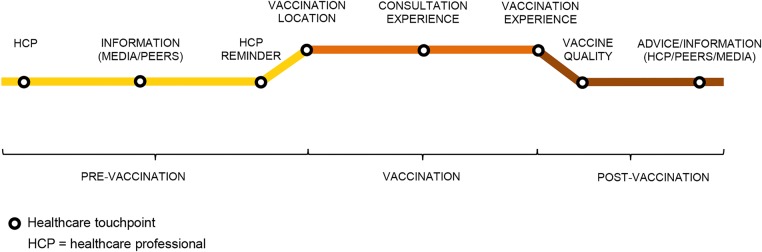

On the basis of the customer journey mapping approach described earlier and previous evidence on vaccination behaviour, we envisage a journey to vaccination to comprise three stages and a number of touchpoints at which the individual interacts with related health services (figure 2): (1) prevaccination period (appointment with HCP, information—websites, news, vaccination campaigns, peers—and HCP reminders); (2) the vaccination experience itself (location, consultation experience and vaccination experience) and (3) a postvaccination experience (vaccine quality—eg, side effects, effectiveness—and postvaccination advice or information—from HCP, peers and other sources).10 35 36 An important component of a journey to vaccination is a cue to action or trigger, which consists of an internal or external stimulus (eg, salient health-related experiences, advice from a relative) that prompts individuals to vaccinate or not to vaccinate. Existing evidence suggests that vaccination triggers may usually take place during the prevaccination stage and could sometimes overlap with vaccination touchpoints.10 For example, a vaccination reminder letter from the general practitioner would be a trigger and a touchpoint, if participants explicitly mention that the letter prompted them to vaccinate.

Figure 2.

Journey to vaccination.

Figure 3 illustrates a journey to flu non-vaccination of a participant from a UK pilot (see Procedure section) who is not at high risk (ie, not eligible for free vaccination). The participant mentioned that an allergy to penicillin discovered when he was younger, which his doctor refused to acknowledge, had made him anxious about other medications’ side effects, including vaccines. This was recorded as the first relevant touchpoint and trigger away from vaccination. He then pointed out that some time ago he had heard on the news that there had been flu-related deaths, and that this had been a cause for concern which made him consider having a flu shot (another touchpoint and trigger to vaccination). Subsequently, he recalled having the flu and worrying about the consequences of being out of work due to his self-employed status (trigger to vaccination). The participant then reported that at that stage he had tried to get a flu vaccine at a pharmacy, but it was out of stock (touchpoint and trigger away from vaccination). Finally, the participant remembered that the vaccine could have side effects and decided to stop trying to get vaccinated (trigger away from vaccination). This journey, therefore, does not include a postvaccination stage. Importantly, analysis of the participant's account of his journey to non-vaccination indicates a tendency to make decisions based on heuristics rather than logical analyses. For example, the participant's motivation to have a flu shot after hearing on the news about flu-related deaths was based on the mental availability of this piece of information and not his actual risk of death from flu.

Figure 3.

Example of a journey to flu non-vaccination.

Study aims

The primary aim of this study was to gain deeper understanding of the social and psychological factors influencing the uptake of two different adult vaccines across key high-income and middle-income countries with diverse healthcare systems: the USA, the UK, France, India, China and Brazil. Specifically, we are interested in exploring how people's experiences shape their beliefs, attitudes and behaviour towards vaccines. A secondary objective was to develop more effective methods to elicit such data.

Methods

Setting

This research is conducted in six countries, in urban, sparsely populated towns and rural areas of the following states or regions: New York, New Jersey and Illinois (USA); West Midlands, London and South East (UK); Nord Pas-de-Calais and Île-de-France (France); Maharashtra and Karnataka (India); Shanghai and Guangzhou (China) and São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil).

Sampling and recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy is used to select adult participants who are vaccinated and not vaccinated against flu and tetanus, and represented a range of sociodemographic characteristics associated with vaccination uptake, notably age and health status (see table 1). In an effort to reduce recall bias,11 only those who have been vaccinated in the past 12 months are eligible to participate. Potential participants are selected at random from current telephone directories. For consistency, a minimum of 20 participants are recruited per country, an acceptable sample size for a qualitative study.37

Table 1.

Purposive sampling strategy

| Key demographic characteristics | Minimum participant quota per country |

|---|---|

| Eligible chronic condition* | 7 with |

| 7 without | |

| Gender | 8 females |

| 8 males | |

| Parent/guardian of child/children under 18 | 4 mothers |

| 4 fathers | |

| Age | 8 18–49 |

| 4 50–64 | |

| 6 ≥65 | |

| Socioeconomic group (social grade)† | 7 ABC1 |

| 7 C2DE | |

| Adults who have had ONE of the vaccines | 4 flu |

| 3 tetanus | |

| Have had tetanus and flu vaccines | 6 |

| Have not had either vaccination | 6 |

| Urban/rural‡ | 5 |

| Total | 20 |

*These include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or bronchitis, heart disease, kidney disease, liver disease, neurological conditions, weakened immune system due to conditions such as HIV and AIDS, or as a result of medication such as steroid tablets or chemotherapy.

†A=higher socioeconomic group and E=lower socioeconomic group. We used country-specific occupation and income data to determine participants’ social grade.

‡The urban/rural quotas for the UK and France were relaxed due to the quality and coverage of their public health systems.

We prioritise unvaccinated participants who state that they will either definitely or probably get vaccinated against flu or tetanus ‘one day’ or that they will probably not get vaccinated against flu or tetanus, as these attitudes are representative of the majority of the non-vaccinated population.38 This is carried out via the following screening question at the time of recruitment: “Which of the following statements most closely reflects your attitude to the flu and tetanus vaccinations? (1) I will definitely get vaccinated against flu or tetanus one day; (2) I will probably get vaccinated against flu or tetanus one day; (3) I will probably not get vaccinated against flu or tetanus; (4) I will definitely not get vaccinated against flu or tetanus.”

Procedure

The data collection is carried out jointly by the first author (UK and USA) and Ipsos MORI, a multinational market research firm and their associates. Interviewers have been trained either face-to-face or via teleconference (USA) by Ipsos MORI researchers. They have also been provided with a manual containing detailed interview instructions. Interview guides and materials have been translated into French (France), Hindi, Marathi and Kannada (India), Chinese (China) and Portuguese (Brazil) by the local research teams. Participants are interviewed face-to-face in their native language for approximately 60 min at home or a central interviewing facility and interviews are digitally recorded. Participants are fully informed about the study via a participant information sheet. Written consent is obtained and each participant receives an equivalent of £11–£78 incentive, depending on the country and location of the interview, in return for their time. Before starting each interview, participants are reminded about the strict confidentiality of their responses.

A prepilot was conducted with N=4 (two researchers from Imperial College London and two from Ipsos MORI not involved in the present study) to test duration and flow of the interview. Consequently, the interview guide was simplified and shortened. These interviews will not be included in the final sample for analysis. A piloting technique was subsequently used for the first three interviews in the UK, whereby the research team observed each interview behind a one-way mirror and evaluated its quality in real time. At the end of the session, minor amendments to the interview guide were agreed and the final interview materials produced.

We use two semistructured and probing interview schedules, one for vaccinated and the other for non-vaccinated participants, constructed through expert consultations and a literature review10 (see table 2). We employ a combination of interviewing techniques to reach a comprehensive understanding of the factors underpinning vaccination decisions. The schedule comprises six sections as follows.

Table 2.

Interview schedule

| Interview topic (sections 1–6) | Key interview questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Overview of life and values |

|

| 2. Information-seeking behaviours and influences |

|

| 3. Views about health and vaccinations |

|

| 4. Journey to vaccination (or non-vaccination) |

|

| 5. Children's vaccinations |

|

| 6. Factual knowledge on flu and tetanus and related vaccines |

|

Section 1 aims to obtain an overview of participants’ life and values, to build rapport and to identify important issues to assist with probing throughout the interview.

Section 2 aims to elicit participants’ general information-seeking behaviours and influences. We explore information sources (eg, media, family, peers, etc) through which people's knowledge about and attitudes towards vaccines may be formed.

Section 3 examines participants’ views towards health, HCPs and adult vaccines. This section aims to understand how people's perceptions towards their own health and their relationship with HCPs influence their stance on vaccines. General views on adult vaccines are evaluated by asking participants to arrange five adult vaccination cards (flu, tetanus, pneumonia, hepatitis and measles, mumps and rubella) into one or more groups. By identifying how people group vaccines, and the reasons for their groupings, we aim to contextualise and gain deeper understanding of their views on flu vaccines and tetanus-containing boosters.

Section 4 explores participants’ journeys to vaccination (or non-vaccination) for flu vaccines and tetanus-containing boosters. We aim to undertake an indepth exploration of the vaccination decision-making process by identifying important aspects that lead people to vaccinate or not to vaccinate.

In an effort to circumvent availability bias, we avoid asking direct questions such as ‘Why did you have a flu shot?’ Instead, we explore the set of circumstances and emotions that drive participants to accept or refuse vaccination, aided by an elicitation technique called laddering, which provides a simple and systematic way of establishing people's core values and beliefs, and the linkages between these and key behaviours, in this case, vaccination.39 To minimise postrationalisation, we do not use probes in this section of the interview.

Section 5 of the interview examines participants’ attitudes towards children's vaccinations. We aim to understand whether people's views about adult vaccines correspond with their views about children's, and if so, how.

Finally, in section 6, we explore participants’ knowledge of the two diseases and vaccines (ie, flu and tetanus) to understand to what extent their decision-making is influenced by facts.

Key sociodemographic information is collected at the end of the interview—including employment status, occupation, health insurance, perceived ability to afford essential goods, level of education, marital status, religion and ethnicity.

Data analyses

The recorded interviews are professionally transcribed and translated into English, and checked for accuracy by Ipsos MORI. To ensure reliability of coding and interpretation, all the transcripts will be analysed by one academic researcher (AW) and 50% of the transcripts will be analysed independently by a second researcher.40 Differences will be resolved through dialogue until consensus is reached. Using thematic analysis, an initial categorising system will be developed based on the study objectives and the topics explored.41 42 New themes and subthemes emerging from the data analysis will be identified and included when consensus is reached regarding their relevance. A final thematic index will be produced to code all data—and verbatim quotes to support the extracted themes will be tabulated. In addition, a journey to vaccination for flu and other for tetanus will be produced for each participant. Differences and commonalities emerging from these data will be identified and synthesised, and, if possible, typical journeys will be proposed.

Ethics and dissemination

This is a collaborative study designed and undertaken by Imperial College London (academic partner), Sanofi Pasteur (commercial partner) and Ipsos MORI (market research partner). A steering group comprising Imperial College London senior researchers, Sanofi Pasteur directors and Ipsos MORI research directors provide ongoing academic input, project management and strategic direction.

Ipsos MORI follows the European Society of Market Research Organisations (ESOMAR) Code of Conduct for international fieldwork. This research is also carried out in accordance with the requirements of the international quality standard for market research, ISO 20252:2006, International general company standard ISO 9001:2008 and International standard for information security ISO 27001:2005.

The nature of the research topic and the sample (general population) make this study one with few ethical issues. However, we recognise that all participants should be willing and able to participate in this study and that there is a small possibility that respondents may disclose information that could potentially cause psychological distress for the individual if the purposes of the research are misunderstood. To address these issues, all participants are informed about the purposes of the research and written consent is obtained from the participants prior to their involvement in the study. Furthermore, when designing the interview schedule, there has been due consideration to the phrasing of the questions so as not to attribute blame, for example, for not carrying out responsible duties associated with participants’ own health or that of the general public.

Our findings will be disseminated to relevant policy, industry, clinical and academic audiences through different outlets. These will be presented as practical recommendations at policy and industry meetings and HCPs’ forums. Our results will also be presented at academic conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Conclusion

Vaccination uptake is significantly influenced by a constellation of social and psychological factors. In order to capture these factors, and to understand their relative importance, we need to go beyond readily available, and in some cases, postrationalised responses, and explore underlying motivations which may be driving vaccination behaviour. This study combines qualitative techniques, service design and psychology theories to develop the journey to vaccination, a new approach aimed at understanding vaccination decision-making processes across time. The journey to vaccination approach will allow us to explore how people's beliefs and attitudes towards vaccination are shaped by their context and experiences, and to evaluate whether vaccination decision-making is driven by heuristic judgement, logical analysis or both, and to what extent.

The global scope of this research will allow us to perform cross-cultural comparisons, which will in turn shed light on key internal (eg, beliefs, perceptions) and external (eg, HCP advice, vaccine availability, cost) stimuli which influence vaccination behaviour across different vaccines, geographies and populations. Our findings can provide a deeper understanding of the barriers and drivers to adult vaccination, which may in turn lead to more effective interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Bruno Rigole and Angus Thomson (Sanofi Pasteur), and Jonathan Nicholls, Helen Cox, Kate Duxbury, Gareth Turley, Reena Sangar and Rebeccah Szyndler (Ipsos MORI), as well as the local research partners, for their valuable advice and management support throughout this study. The authors would also like to thank Marion Dolbeau (Sanofi Pasteur) for her contribution to the design and execution of this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors agree with the manuscript's contents. AW, NS and MM contributed to the design of the study and interview schedule. All authors contributed to the write-up.

Funding: The fieldwork and associated research costs are funded by Sanofi Pasteur.

Competing interests: AW and NS are funded by an unrestricted research grant from Sanofi Pasteur and also by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via the Imperial College's Patient Safety Translational Research Centre (http://www.cpssq.org).

Ethics approval: This study was approved by Imperial College Research Ethical Committee (ICREC) in the UK, American Institutes for Research (AIR) in the USA, Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés (CNIL) and Comité de protection des personnes ‘Ile-de-France III’ in France, Safe Search Independent Ethics Committee in India, Shanghai Clinical Research Center in China and Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa (CONEP) in Brazil.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.UNICEF Immunization: the big picture. http://www.unicef.org/immunization/index_bigpicture.html (accessed 1 Jul 2013).

- 2.UNICEF Global immunization vision and strategy 2006–2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, While AE, Norman IJ. Nurses’ knowledge and risk perception towards seasonal influenza and vaccination and their vaccination behaviours: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:1281–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommended adult immunization schedule—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghendon Y. Influenza—its impact and control. World Health Stat Q 1992;45:306–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Tetanus vaccine. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2006;81:197–208 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nennig ME, Shinefield HR, Edwards KM, et al. Prevalence and incidence of adult pertussis in an urban population. JAMA 1996;275:1672–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system 2010 global summary. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_IVB_2010_eng.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2013).

- 9.Kohlhammer Y, Schnoor M, Schwartz M, et al. Determinants of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in elderly people: a systematic review. Public Health 2007;121:742–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheelock A, Thomson A, Sevdalis N. Social and psychological factors underlying adult vaccination behavior: lessons from seasonal influenza vaccination in the US and the UK. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013;12:893–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NVAC NVAC Vaccine Hesitancy Working Group Charge. http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/subgroups/nvac-vaccine-hesitancy-wgcharge.html (accessed 1 Jul 2013).

- 12.Hunink MM. Decision making in health and medicine: integrating evidence and values. Cambridge University Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serpell L, Green J. Parental decision-making in childhood vaccination. Vaccine 2006;24:4041–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipkus IM, Samsa G, Rimer BK. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples. Med Decis Making 2001;21:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meehl PE. Clinical versus statistical prediction: a theoretical analysis and review of the literature. Minesota: University of Minesota Press, 1954 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon H. Models of man: social and rational. New York: Wiley, 1957 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahneman D, Tversky A. On the psychology of prediction. Psych Rev 1973;80:237–51 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Martino B, Kumaran D, Seymour B, et al. Frames, biases, and rational decision-making in the human brain. Science 2006; 313:684–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alaszewski A, Horlick-Jones T. How can doctors communicate information about risk more effectively? BMJ 2003;327:728–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans MR, Prout H, Prior L, et al. A qualitative study of lay beliefs about influenza immunisation in older people. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong EW-y, Pang SM-c, Choi P-p, et al. Influenza vaccine preference and uptake among older people in nine countries. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:2297–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telford R, Rogers A. What influences elderly peoples’ decisions about whether to accept the influenza vaccination? A qualitative study. Health Educ Res 2003;18:743–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponterotto JG. Qualitative research in counseling psychology: a primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. J Couns Psychol 2005;52:126–36 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sciarra D. The role of the qualitative researcher. In: Kopala M, Suzuki LA. eds. Using qualitative methods in psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999:37–48 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychol 1973;5:207–32 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kingman-Brundage J. The ABCs of Service System Blueprinting. In: Lovelock CH. ed. Managing services: marketing, operations and human resources. Prentice-Hall International, Inc, 1992:96–102 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shostack GL. Designing services that deliver. Harvard Bus Rev 1984;62:133–9 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bitner MJ. Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J Marketing 1992;56:57–71 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 1974;185:1124–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans JSB, Curtis-Holmes J. Rapid responding increases belief bias: evidence for the dual-process theory of reasoning. Think Reasoning 2005;11:382–89 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol Rev 2001;108:814–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson TD. Strangers to ourselves: discovering the adaptive unconscious. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, Gosling AS, et al. Critical incidents and journey mapping as techniques to evaluate the impact of online evidence retrieval systems on health care delivery and patient outcomes. Int J Med Inform 2007;76:234–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunn M, Davis SM. Building the brand-driven business. Operationalize your brand to drive profitable growth. San Francisco: Tossey-Bass, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw C, Ivens J. Building great customer experiences. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds TJ, Olson JC. Understanding consumer decision making: the means-end approach to marketing and advertising strategy. Psychology Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. London: Sage, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. 4th ed. London: Sage, 2009 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.