Abstract

Context:

It has been suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction in adipocytes contributes to obesity-related metabolic complications. However, obesity results in adipocyte hypertrophy, and large and small adipocytes from the same depot have different characteristics, raising the possibility that obesity-related mitochondrial defects are an inherent function of large adipocytes.

Objective:

Our goal was to examine whether obesity, independent of fat cell size and fat depot, is associated with mitochondria dysfunction.

Design:

We compared adipocyte mitochondrial function using a cross-sectional comparison study design.

Setting:

The studies were performed at Mayo Clinic, an academic medical center.

Patients or Other Participants:

Omental and/or abdominal subcutaneous adipose samples were collected from 20 age-matched obese and nonobese nondiabetic men and women undergoing either elective abdominal surgery or research needle biopsy.

Intervention:

Interventions were not conducted as part of these studies.

Main Outcome Measures:

We measured mitochondrial DNA abundance, oxygen consumption rates, and citrate synthase activity from populations of large and small adipocytes (separated with differential floatation).

Results:

For both omental and subcutaneous adipocytes, at the cell and organelle level, oxygen consumption rates and citrate synthase activity were significantly reduced in cells from obese compared with nonobese volunteers, even when matched for cell size by comparing large adipocytes from nonobese and small adipocytes from obese. Adipocyte mitochondrial content was not significantly different between obese and nonobese volunteers. Mitochondrial function and content parameters were not different between small and large cells, omental, and subcutaneous adipocytes from the same person.

Conclusion:

Adipocyte mitochondrial oxidative capacity is reduced in obese compared with nonobese adults and this difference is not due to cell size differences. Adipocyte mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity is therefore related to overall adiposity rather than adipocyte hypertrophy.

Although adipocytes are considered to be relatively inert from the perspective of energy metabolism, they nonetheless require functional mitochondria to generate ATP needed for adipokine synthesis/secretion, lipogenesis, and lipolysis. Both rodent (1) and human (2) obesity are associated with decreased mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity, suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to adipocyte dysfunction. Reduced numbers or function of adipocyte mitochondrial may explain some of the functional abnormalities of adipose tissue associated with obesity.

Assessments of mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative capacity of cultured adipocytes (3, 4) and rodent adipose tissue (1, 5) have been performed. Although cell lines and animal models can be useful tools, they suffer from the disadvantage that they might not reflect the function of human adipose tissue. In addition, some investigators assess mitochondrial oxidative capacity by measuring the activities of key mitochondrial enzymes, whereas measuring oxygen consumption of isolated mitochondria more directly evaluates adipocyte mitochondrial function (6).

Despite this interest in adipocyte mitochondrial function, relatively little is known about the effects of obesity, fat cell size, and fat depot of origin on adipocyte mitochondrial capacity for oxidative phosphorylation. Furthermore, recent studies indicate that large and small adipocytes from the same depot differ with regards to gene expression (7) and a number of other properties (8–10). These studies were performed to test the hypothesis that any decreased oxygen consumption capacity of adipocyte mitochondrial from obese adults is due to the greater fat cell size of the donor. To test this hypothesis, we measured the oxygen consumption rates (OCR) of isolated mitochondria harvested from large adipocytes from nonobese adults and small adipocytes from obese adults to create comparisons where adipocyte size was not different between obese and nonobese.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Adipose tissue samples (4–6 g) from the abdominal subcutaneous (periumbilical) region and the peripheral portion of the greater omentum were collected from a total of 23 patients, 20 (12 female) undergoing elective abdominal surgery and 3 undergoing outpatient needle aspiration biopsy as previously described (11). Entry criteria were age 18 to 75 years old; patients were recruited to have a wide range of body mass index (BMI) values. No patient had intra-abdominal inflammatory disorders, advanced cancer, or diabetes. Patients taking thiazolidinediones or medications that could potentially affect mitochondrial function were excluded. Written, informed consent was obtained before the procedure.

Adipose tissue digestion

Approximately 3 g of minced adipose tissue was digested in collagenase (type II C-6885; Sigma Chemical Co) in HEPES buffer (0.1 mol HEPES/L, 0.12 mol NaCl/L, 0.05 mol KCl/L, 0.005 mol glucose/L, 1.5% [wt:vol] bovine serum albumin, and 1 mmol CaCl2/L [pH 7.4]) in a 37°C water bath shaking at 100–115 rotations per minute. The digestion was typically complete within 20–60 minutes. The resulting cell suspension was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 300g at room temperature to bring the cells to the top, allowing us to pipette off the buffer below the cells. These cells were resuspended in 10 mL HEPES.

Adipocytes separation by size

When suspended in an aqueous solution, larger adipocytes float to the surface faster than small adipocytes. This property allowed us to separate two populations of different size cells. Briefly, 10 mL of the adipocyte mixture and 40 mL HEPES were carefully added to a 250-cc separation funnel, mixed gently, and allowed to settle for 60 seconds. At 60 seconds we drained the lower 35 mL from the separation funnel into a beaker to collect the smaller cells. We then added 35 mL HEPES buffer to the funnel and repeated this operation three times. The second and third float times were 45 and 30 seconds, respectively. The remaining upper 15 mL of adipocytes-containing buffer contained the large cells. Portions of the large and small cell fractions were saved at −70°C for DNA extraction.

Measurement of adipocyte size

The size of cells in total tissue, as well as the isolated large and small fat cells, was measured using digital photomicrographs and an automated software program as previously described (12). We measured an average of 500 cells per sample to calculate average adipocyte size and to confirm adequate separation by cell size.

Mitochondria isolation by differential centrifugation

Homogenization buffer A (100 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris, 5 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM ATP, and 1 mM EDTA) was added to the suspensions of large and small cells. Cells were homogenized and centrifuged at 2100g for 10 minutes (4 C). The middle layer of the solution was transferred to 6 mL ultracentrifuge tubes and spun at 10 000g for 10 minutes to pellet the mitochondria. The mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in buffer A (volume 2 mL) and a second high-speed centrifugation was performed at 10 000g for 10 minutes, and the mitochondrial pellets were gently resuspended in buffer B (225 mM sucrose, 44 mM KH2PO4, 12.5 mM Mg acetate, and 6 mM EDTA) and were used for OCR and citrate synthase (CS) activity measurements.

Determination of adipocyte number

After homogenization, the top fat layer of the solution was collected and weighed (as described in [11]). The numbers of adipocytes for each sample used for measurement of OCR and CS activity measurements were calculated by dividing the fat weight by the mean adipocyte size (μg lipid/cell).

Measurement of oxygen consumption in isolated mitochondria

The function of isolated adipocyte mitochondria was assessed using OCR measurements with high-resolution respirometry (Oxygraph-2k; Oroboros) as described previously (6, 13). Briefly, a 90-μL aliquot of the mitochondrial suspension was added to the 2-mL oxygraph chamber filled with respiration medium. After equilibration, the substrates, including 10 mM glutamate, 2 mM malate, 2.5 mM ADP, and 10 mM succinate, were then added to the chamber. Oxygen concentration was recorded and respiration rates were calculated as the negative time derivative of oxygen concentration (Datlab Version 4.2.1.50; Oroboros Instruments). The OCR value represents the maximum mitochondrial oxidative capacity with electron flow through both complexes I and II (6), which we present normalized to both the amount of mitochondrial protein (organelle level) and the cell number (by using data regarding the number of cells in the large and small fractions assuming complete recovery of mitochondria) to allow comparison across groups. Mitochondrial CS activity was measured spectrophotometrically as described previously (13).

Mitochondrial DNA abundance

DNA was extracted from large and small adipocyte samples using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen). The abundance of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)-encoded reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase 1 gene was measured using a real-time quantitative PCR system (PE Biosystems). Samples were run in duplicate and mtDNA content was normalized to 28S ribosomal DNA, as described previously (14).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp). All values are expressed as mean ± SD. We performed nonpaired t-tests to compare mitochondrial function and mass values between nonobese and obese, large and small adipocyte groups. We also compared the adipocyte mitochondrial function and mass between different depots by using data from a subset of volunteers for whom we had measured mitochondrial function (n = 14) and mass (n = 16) data in both omental and subcutaneous depots using paired t-tests. Univariate linear regression analysis was used to analyze the relationships of mitochondrial function and mass values with BMI, sex, age and cell size. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Volunteer characteristics

The demographic information of the participants is provided in Table 1. We collected omental and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue from 19 and 20 patients, respectively. The participants were 25 to 75 years old and their BMI values ranged from 17.8 to 58.0 kg/m2. The nonobese and obese groups were well-matched for age, with similar numbers of men and women.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Volunteers

| Group | N | Sex (F) | Age | BMI | Cell Size (μg lipid/cell) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cells | Large Cells | Small Cells | |||||

| Omental | |||||||

| Nonobese | 9 | 5 | 53 ± 10 | 23.8 ± 3.3 | 0.37 ± 0.24 | 0.50 ± 0.21a | 0.23 ± 0.27 |

| Obese | 10 | 5 | 53 ± 9 | 42.0 ± 7.8 | 0.73 ± 0.31 | 0.99 ± 0.20a | 0.46 ± 0.09 |

| Abdominal subcutaneous | |||||||

| Nonobese | 10 | 5 | 45 ± 14 | 24.9 ± 3.2 | 0.61 ± 0.42 | 0.85 ± 0.18a | 0.37 ± 0.25 |

| Obese | 10 | 5 | 42 ± 10 | 36.9 ± 4.1 | 0.96 ± 0.46 | 1.29 ± 0.39a | 0.61 ± 0.16 |

Data show as mean ± SD for continuous variables.

P < .05 compared with small cells.

As expected, omental and abdominal subcutaneous adipocytes from obese volunteers were significantly larger than those from nonobese volunteers. Subcutaneous adipocytes were larger than omental adipocytes (0.66 ± 0.43 vs 0.51 ± 0.32 μg lipid/cells, P < .05).

Adipocyte fractionation

The floatation separation method allowed us to create two populations of adipocytes of different sizes from each sample. For both groups and both depots, we were able to obtain small and large cells of significantly different sizes (Table 1). This separation by size allowed us to investigate whether mtDNA content and function were different in cells of different sizes within the same adipose depot. We were also able to examine whether the mitochondria harvested from large abdominal subcutaneous adipocyte obtained from nonobese patients functioned differently than mitochondrial from small abdominal subcutaneous adipocytes from obese patients when fat cell size was not different (0.85 ± 0.18 vs 0.61 ± 0.16 μg lipid/cell, lean vs obese, respectively, P = .20). Similarly, we compared mitochondria from large omental adipocytes from nonobese patients and small omental adipocytes from obese patients matched for fat cell size (0.50 ± 0.21 vs 0.46 ± 0.09 μg lipid/cell, lean vs obese, respectively, P = .85).

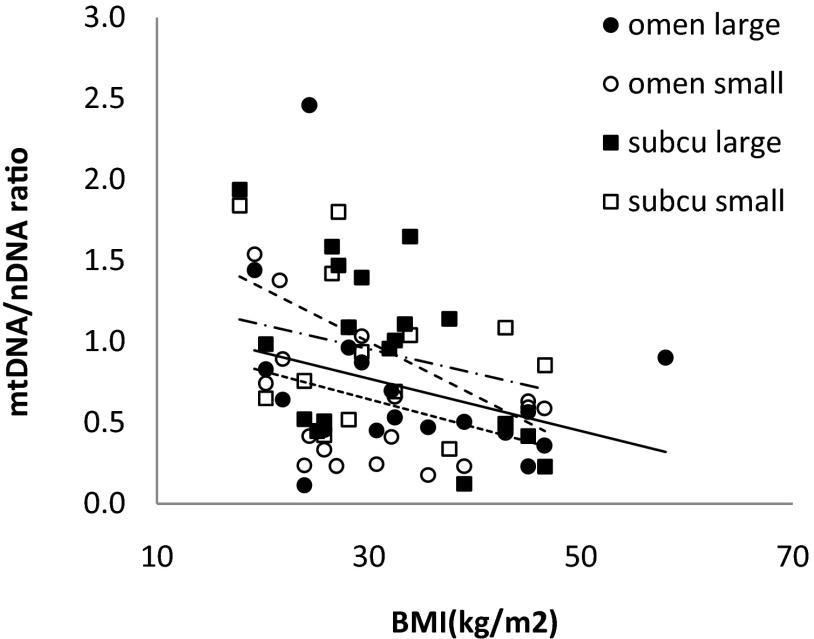

Adipocyte mitochondria content

We used the mtDNA-encoded reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase 1 (ND1) gene expression, normalized to the 28S nuclear gene, to examine mitochondrial content relative to cell number. The data are summarized in Table 2. By this measure, the mitochondrial content of large adipocytes from nonobese volunteer and small adipocytes from obese volunteers (both depots) was not statistically different. The ND1 copy number was not significantly different between omental and subcutaneous adipocytes from the same person, nor was it different between large and small cells from same person and same depot. Although there was a trend for lesser adipocyte mtDNA content with greater BMI (Figure 1), the negative relationship was statistically significant only for subcutaneous large cells (r = −0.51, P = .03). We did not find any statistically significant associations between adipocyte mtDNA copy number and age for small cells or large cells in omental or abdominal subcutaneous fat. Likewise, we detected no differences between men and women with respect to mtDNA.

Table 2.

Adipocyte Mitochondria Content and Function

| Group | ND1/28SnDNA | Citrate Synthase (μmol/mL/min/mg protein) | Oxygen Consumption Rate (pmol/[smL]/mg protein) | Citrate Synthase (μmol/mL/min/cell) | Oxygen Consumption Rate (pmol/[smL]/cell) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonobese | |||||

| Omental large | 0.97 ± 0.71 (8) | 1.0 ± 0.43 (9) | 118 ± 56 (9)a | 1.97 ± 1.09 (5)a | 263 ± 141 (5)a |

| Subcutaneous large | 1.11 ± 0.53 (9) | 1.2 ± 0.58 (10)b | 134 ± 69 (10)b | 2.29 ± 0.77 (9)b | 290 ± 160 (9)a |

| Omental small | 0.79 ± 0.47 (10) | 1.05 ± 0.36 (9) | 120 ± 57 (9) | 1.32 ± 0.30 (6) | 169 ± 48 (6) |

| Subcutaneous small | 1.04 ± 0.57 (8) | 1.10 ± 0.53 (10) | 126 ± 67 (10) | 1.52 ± 0.85 (9) | 169 ± 63 (9) |

| Obese | |||||

| Omental large | 0.52 ± 0.18 (10) | 0.52 ± 0.21 (10)d | 66 ± 30 (10)c | 0.49 ± 0.20 (6)d | 61.2 ± 30 (6)c |

| Subcutaneous large | 0.79 ± 0.50 (9) | 0.50 ± 0.13 (11)d | 62 ± 38 (11)d | 1.14 ± 0.58 (8)d | 119 ± 64 (8)c |

| Omental small | 0.44 ± 0.20 (8) | 0.67 ± 0.36 (10)d | 69 ± 27 (10)c | 0.58 ± 0.32 (4)d | 79 ± 46 (4)c |

| Subcutaneous small | 0.80 ± 0.30 (5) | 0.56 ± 0.19 (11)d | 63 ± 24 (11)d | 1.02 ± 0.58 (9) | 123 ± 79 (9) |

| Omentale | 0.63 ± 0.30 (14) | 0.75 ± 0.41 (16) | 91 ± 55 (16) | 1.03 ± 0.57 (10) | 136 ± 98 (10) |

| Subcutaneous | 0.76 ± 0.31 (14) | 0.88 ± 0.50 (16) | 97 ± 62 (16) | 1.23 ± 0.63 (10) | 146 ± 71 (10) |

| Large cellse | 0.88 ± 0.56 (29) | 0.79 ± 0.47 (40) | 94 ± 59 (40) | 1.50 ± 0.99 (27) | 186 ± 147 (27) |

| Small cells | 0.77 ± 0.45 (29) | 0.83 ± 0.43 (40) | 93 ± 58 (40) | 1.18 ± 0.67 (27) | 138 ± 70 (27) |

Results are means ± SD (n). CS-specific activities and ND1 copy numbers were measured in triplicate; OCR was measured duplicate as described in Methods.

P < .05;

P < .01, compared with the same subgroup in obese small cells.

P < .05;

P < 0.01, compared with the same subgroup vs non-obese.

These are the comparisons using only paired data from omental and abdominal subcutaneous adipocyte from the same individuals or large and small cells were from the same individuals, same adipose tissue depots as described in Methods.

Figure 1.

Correlations between BMI and mtDNA. mtDNA content values are plotted vs BMI. Correlation coefficients were r = −0.33, P = .18 in omental large cells; r = −0.37, P = .128 in omental small cells; r = −0.51, P = .028 in subcutaneous large cells; r = −.26, P = .39 in subcutaneous small cell group.

Adipocyte mitochondria function—effects of obesity and fat cell size

The OCR and CS activities were normalized to mitochondrial protein concentration (organelle parameter) and cell number to allow both options for examining the data. At the cell and organelle level, adipocyte mitochondria OCR and CS activity were twice as great in cells from nonobese volunteers as obese volunteers (P < .01). Comparing large adipocytes from nonobese volunteers and small adipocytes from obese volunteers, for both omental and subcutaneous adipocytes, mitochondrial OCR values and CS activity were greater in cells from nonobese than in cells from obese volunteers, at both the cell and the organelle level (P < .01, Table 2).

For adipocytes from the same person and same depot, there were no significant differences in OCR values and CS activities between large and small adipocytes at either the organelle or the cell level. At both the cell and the organelle levels, there were no significant differences in mitochondrial OCR and CS activities between omental and abdominal subcutaneous adipocytes collected from the same person.

We found negative correlations between OCR values (Figure 2A), CS-specific activity (Figure 3A), and BMI at the organelle level for the large and small adipocytes from both omental and abdominal subcutaneous depots. Similar negative correlations between OCR, CS-specific activity, and BMI at the cell level were also observed (Figures 2B and 3B). These findings are in agreement with the nonpaired comparisons of OCR and CS between nonobese and obese groups (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Correlation between BMI and oxidative capacity. OCR values were normalized by mitochondrial protein concentration (A) and cell numbers (B), respectively. OCR values were plotted against BMI. Correlation coefficients were r = −0.50, P = .03 in the omental large cell group; r = −0.47, P = .04 in the omental small group; r = −0.57, P = .007 in the subcutaneous large cell group; r = −0.53; P = .013 in the subcutaneous small cell group for OCR per milligram mitochondrial protein (A). Correlation coefficients were r = −0.83, P = .001 in the omental large cell group; r = −0.86, P = .0011 in the omental small cell group; r = −0.72, P = .001 in the subcutaneous large cell group; r = −0.51; P = .032 in the subcutaneous small cell group for OCR per cell (B). We were unable to calculate the cell number for all individuals, including two with BMI >50; thus, the x-axis for B is different than A.

Figure 3.

Correlations between BMI and CS-specific activity of adipocytes. CS activities were normalized by mitochondrial protein (A) and cell number (B), respectively. Correlation coefficients were r = −0.57 P = .01 in the omental large cell group; r = −0.19 P = .43 in the omental small cell group; r = −0.58 P = .005 in the subcutaneous large cell group; r = −0.52; P = .016 in the subcutaneous small cell group for CS activity per milligram mitochondrial protein (A). Correlation coefficients were r = −0.80, P = .003 in the omental large cell group; r = −0.69, P = .027 in the omental small cell group; r = −0.81, P = .0001in the subcutaneous large cell group; r = −0.35; P = .15 in the subcutaneous small cell group for CS activity per cell (B). We were unable to calculate the cell number for all individuals, including two with BMI >50; thus, the x-axis for B is different than A.

We examined whether parameters of mitochondrial function varied as a function of fat cell size in both fat depots in obese and nonobese patients; the results are provided in Table 3. At both the cell and the organelle levels, the fat cell size (μg lipid/cell) of large omental adipocytes was negatively correlated with mitochondrial OCR values and CS-specific activity (P < .01). We also found a negative correlation between fat cell size and OCR values at the organelle level for omental small and subcutaneous large cells (P < .05).

Table 3.

Correlations Between Cell Size and Mitochondrial Oxidative Capacity, Specific Activity of Citrate Synthase

| Group | OCR (pmol/[s · mL]/cell) |

CS (μmol/mL/min/cell) |

OCR (pmol/[s · mL]/mg protein) |

CS (μmol/mL/min/mg protein) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | r | n | r | n | r | n | r | |

| Omental large | 11 | −0.84a | 11 | −0.77a | 19 | −0.59a | 19 | −0.56a |

| Omental small | 10 | −0.07 | 10 | −0.32 | 19 | −0.47b | 19 | −0.40 |

| Subcutaneous large | 17 | −0.30 | 17 | −0.13 | 21 | −0.45b | 21 | −0.38 |

| Subcutaneous small | 18 | −0.08 | 18 | −0.21 | 21 | −0.30 | 21 | −0.14 |

P < .01;

P < .05.

Adipocyte mitochondria function—effects of age and sex

We tested whether there was a relationship between age and adipocyte mitochondrial OCR and CS, normalized to cell number and mitochondrial protein content, respectively. At cell level, there was negative correlation between age and CS activity for small subcutaneous cells (r = 0.56, P = .016). Similarly, there was moderate correlation between age and OCR for small subcutaneous cells (r = 0.45, P = .058). We found no significant relationships between age and OCR or CS activity for omental adipocytes or subcutaneous large cells. At the organelle level, there was no significant relationship between mitochondrial OCR or CS-specific activity and age. We also examined whether, when analyzing samples from men vs women, there were differences in mitochondrial OCR or CS parameters; no differences were found.

Discussion

These studies were designed to understand whether adipocyte mitochondrial content and function are reduced in obesity independent of fat cell size. By using a differential floatation method, we were able compare mitochondria from adipocytes of comparable size isolated from nonobese and obese humans. We also examined whether mitochondrial content and function varied as between depots (visceral vs subcutaneous) and characteristics such as BMI, age, and sex. We found a modest and largely nonsignificant trend for reduced mtDNA in adipocytes from obese individuals, but clear evidence of reduced mitochondrial aerobic capacity and CS-specific activity in adipocytes from obese adults, independent of fat cell size. Of note, there were no significant differences in mitochondrial OCR or CS between small and large adipocytes from the same person or between omental and abdominal subcutaneous adipocytes. These findings indicate that something about the obese state results in impaired adipocyte mitochondrial function irrespective of fat cell size or location.

Several investigators have shown that adipocyte mitochondrial DNA content and genes encoding mitochondrial proteins are decreased in obese db/db mice (1) and ob/ob mice (15). Some authors have reported increased mtDNA content in adipocytes from morbidly obese humans (16, 17), whereas our findings are more in accordance with Yehuda-Shnaidman et al (18), who found no statistically significant differences in adipocyte mitochondrial content between obese and nonobese humans. The same group demonstrated that adipocytes from obese donors had a lesser OCR response to β-adrenergic stimulation (18), again consistent with our data. However, Yehuda-Shnaidman et al (18) could not discern whether the decreased mitochondrial function in obesity was related merely to increased fat cell size. Our results clearly indicate that mitochondrial oxidative capacity in adipocyte from obese humans cannot be attributed to adipocyte hypertrophy. This observation leads us to propose that the reduced oxidative capacity per mitochondria is the primary contributor to the compromised mitochondrial function in adipocytes from obese humans.

We were particularly interested in the question of whether adipocyte mitochondrial oxidative capacity and content are altered as a result of adipocyte hypertrophy vs obesity itself, because a number of adipocyte characteristics vary as a function of cell size (19–24). If cell enlargement per se decreases mitochondrial oxidative capacity, that could explain some of the relationships between obesity and adipocyte dysfunction. Our observation that even small adipocytes from obese humans have decreased OCR compared with nonobese controls suggests that obesity itself, not adipocyte hypertrophy, is the cause of mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition, the nature of the continuous associations shown in Figures 2 and 3 suggests that much of the decline in function occurs between a BMI of 20 and 30 kg/m2.

Although many differences have been described between visceral and subcutaneous fat (25–27), we were surprised that the measures of mitochondrial function we used were not different between omental and abdominal subcutaneous fat from either obese or nonobese adults. Likewise, large and small cells from the same depot from the same person were similar. Obesity had a much greater effect on mitochondrial function than either cell size or depot of origin. Perhaps the energy requirements for basic functions are sufficiently similar that, absent obesity, the adipocyte need for ATP from mitochondria is very similar irrespective of site or cell size.

There are several potential explanations for mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. One is that increased mitochondrial substrate load from overnutrition results in greater activity in the electron transport chain, reactive oxygen species production (28), and oxidative stress (29). Excess lipid storage might also cause functional abnormalities of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The ER actively participates in the lipid storage steps of synthesizing of fatty acids into triglycerides and bundling of triglycerides into lipid droplets; these pathways must respond to challenges of excess nutrient supply. If adipocytes suffer ER stress, accumulation of unfolded proteins may result, which generate high levels of reactive oxygen species (30) and disrupt the functional relationship between the mitochondrial and the ER (31). Finally, the chronic proinflammatory process in adipose tissue may compromise mitochondrial function in human obesity (32). In this case, the nonfat cells of adipose tissue, rather than fat cells, may be the main source of inflammatory cytokines produced by fat (33, 34). The present study did not address which, if any, of these factors contributed to the decreased adipocyte mitochondrial oxidative capacity.

We also examined whether some mitochondrial parameters relate to adipocyte size. Mitochondrial content, as measured by mtDNA copy number, was somewhat greater in large than small cells in samples from the nonobese group (Table 2), but not in the obese group. This may indicate that larger adipocytes in nonobese humans require/have more mitochondria to meet the ATP of larger cells. When the total adiposity reaches a critical level, there appears to be no further increase in mitochondrial content with larger adipocytes. This compromised adipocyte mitochondrial function might impair glucose and lipid metabolism at cellular level (35).

A limitation of the present study is that we did not examine the relationship between adipocyte mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity of the donors. Obesity is a high risk factor for insulin resistance. The mechanism or mechanisms by which excessive energy intake and weight gain cause insulin resistance have not completely been elucidated. Mitochondrial dysfunction is thought to be involved in accumulation of fatty acids in liver (36) and muscle (37–39), leading to insulin resistance of these organs; however, findings on mitochondrial function in relation to insulin resistance are inconsistent in human subjects (40), and few have focused on the relation between mitochondrial function and insulin resistance in adipocytes. Whether reduced mitochondrial function in adipocyte is causally related to insulin resistance remains to be elucidated, and further studies may clarify this issue.

In summary, the present study suggested that adipocyte mitochondrial oxidative capacity measured in vitro is decreased in obese compared with lean adults and the difference cannot be attributed merely to differences in fat cell size. There was no difference in mtDNA content and oxidative capacity between adipocytes from omental and subcutaneous depots and of different fat cell sizes in the same person. The results lead us to propose that obesity per se is a greater factor than adipocyte hypertrophy as a cause of mitochondrial dysfunction. Adipocyte hypertrophy and decreased mitochondrial function may mutually amplify each other during overnutrition and the metabolic imbalance in obesity. We also propose that reduced oxidative capacity per mitochondria is the primary contributor to the compromised mitochondrial function in adipocytes from obese humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deborah Harteneck and Jill Schimke for technical assistance with the analyses for these studies.

This work was supported by 1 UL1 RR024150 from the National Center for Research Resources, by Grants DK40484, DK45343, RO1DK41973, and DK50456 from the U.S. Public Health Service, and by the Mayo Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMI

- body mass index

- CS

- citrate synthase

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- mtDNA

- mitochondrial DNA

- ND1

- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase 1

- OCR

- oxygen consumption rates.

References

- 1. Koh EH, Park JY, Park HS, et al. Essential role of mitochondrial function in adiponectin synthesis in adipocytes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2973–2981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heilbronn LK, Gan SK, Turner N, Campbell LV, Chisholm DJ. Markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism are lower in overweight and obese insulin-resistant subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1467–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilson-Fritch L, Burkart A, Bell G, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis and remodeling during adipogenesis and in response to the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1085–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newton BW, Cologna SM, Moya C, Russell DH, Russell WK, Jayaraman A. Proteomic analysis of 3T3–L1 adipocyte mitochondria during differentiation and enlargement. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4692–4702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deveaud C, Beauvoit B, Salin B, Schaeffer J, Rigoulet M. Regional differences in oxidative capacity of rat white adipose tissue are linked to the mitochondrial content of mature adipocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;267:157–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lanza IR, Nair KS. Functional assessment of isolated mitochondria in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 2009;457:349–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jernås M, Palming J, Sjöholm K, et al. Separation of human adipocytes by size: hypertrophic fat cells display distinct gene expression. FASEB J. 2006;20:1540–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farnier C, Krief S, Blache M, et al. Adipocyte functions are modulated by cell size change: potential involvement of an integrin/ERK signalling pathway. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1178–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wueest S, Rapold RA, Rytka JM, Schoenle EJ, Konrad D. Basal lipolysis, not the degree of insulin resistance, differentiates large from small isolated adipocytes in high-fat fed mice. Diabetologia. 2009;52:541–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laurencikiene J, Skurk T, Kulyté A, et al. Regulation of lipolysis in small and large fat cells of the same subject. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E2045–E2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tchoukalova YD, Koutsari C, Karpyak MV, Votruba SB, Wendland E, Jensen MD. Subcutaneous adipocyte size and body fat distribution. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tchoukalova YD, Harteneck DA, Karwoski RA, Tarara J, Jensen MD. A quick, reliable, and automated method for fat cell sizing. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1795–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lanza IR, Zabielski P, Klaus KA, et al. Chronic caloric restriction preserves mitochondrial function in senescence without increasing mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2012;16:777–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Short KR, Bigelow ML, Kahl J, et al. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5618–5623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson-Fritch L, Nicoloro S, Chouinard M, et al. Mitochondrial remodeling in adipose tissue associated with obesity and treatment with rosiglitazone. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1281–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Naeyer H, Ouwens DM, Van Nieuwenhove Y, et al. Combined gene and protein expression of hormone-sensitive lipase and adipose triglyceride lipase, mitochondrial content, and adipocyte size in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue of morbidly obese men. Obes Facts. 2011;4:407–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lindinger A, Peterli R, Peters T, et al. Mitochondrial DNA content in human omental adipose tissue. Obes Surg. 2010;20:84–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Buehrer B, Pi J, Kumar N, Collins S. Acute stimulation of white adipocyte respiration by PKA-induced lipolysis. Diabetes. 2010;59:2474–2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Allred CC, Krennmayr T, Koutsari C, Zhou L, Ali AH, Jensen MD. A novel ELISA for measuring CD36 protein in human adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:408–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rebuffe-Scrive M, Guy-Grand B. Lipogenesis in human adipose tissue in vitro: effect of fat cell size on some enzymatic activities. Diabetes Metab. 1979;5:129–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arner P, Ostman J. Relationship between the tissue level of cyclic AMP and the fat cell size of human adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 1978;19:613–618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fried SK, Kral JG. Sex differences in regional distribution of fat cell size and lipoprotein lipase activity in morbidly obese patients. Int J Obes. 1987;11:129–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elbers JM, de Jong S, Teerlink T, Asscheman H, Seidell JC, Gooren LJ. Changes in fat cell size and in vitro lipolytic activity of abdominal and gluteal adipocytes after a one-year cross-sex hormone administration in transsexuals. Metabolism. 1999;48:1371–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jacobsson B, Smith U. Effect of cell size on lipolysis and antilipolytic action of insulin in human fat cells. J Lipid Res. 1972;13:651–656 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hellmér J, Marcus C, Sonnenfeld T, Arner P. Mechanisms for differences in lipolysis between human subcutaneous and omental fat cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leibel RL, Hirsch J. Site- and sex-related differences in adrenoreceptor status of human adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:1205–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ali AH, Koutsari C, Mundi M, et al. Free fatty acid storage in human visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue: role of adipocyte proteins. Diabetes. 2011;60:2300–2307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Subauste AR, Burant CF. Role of FoxO1 in FFA-induced oxidative stress in adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E159–E164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Curtis JM, Grimsrud PA, Wright WS, et al. Downregulation of adipose glutathione S-transferase A4 leads to increased protein carbonylation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Diabetes. 2010;59:1132–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lim JH, Lee HJ, Ho Jung M, Song J. Coupling mitochondrial dysfunction to endoplasmic reticulum stress response: a molecular mechanism leading to hepatic insulin resistance. Cell Signal. 2009;21:169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rieusset J. Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum: mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum interplay in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1257–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bondia-Pons I, Ryan L, Martinez JA. Oxidative stress and inflammation interactions in human obesity. J Physiol Chem. 2012;68:701–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fain JN, Tagele BM, Cheema P, Madan AK, Tichansky DS. Release of 12 adipokines by adipose tissue, nonfat cells, and fat cells from obese women. Obesity. 2010;18:890–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gustafson B, Gogg S, Hedjazifar S, Jenndahl L, Hammarstedt A, Smith U. Inflammation and impaired adipogenesis in hypertrophic obesity in man. Am J Phyiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E999–E1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brookheart RT, Michel CI, Schaffer JE. As a matter of fat. Cell Metab. 2009;10:9–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee HJ, Chung K, Lee H, Lee K, Lim JH, Song J. Downregulation of mitochondrial lon protease impairs mitochondrial function and causes hepatic insulin resistance in human liver SK-HEP-1 cells. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1437–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martins AR, Nachbar RT, Gorjao R, et al. Mechanisms underlying skeletal muscle insulin resistance induced by fatty acids: importance of the mitochondrial function. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zheng J, Chen LL, Zhang HH, Hu X, Kong W, Hu D. Resveratrol improves insulin resistance of catch-up growth by increasing mitochondrial complexes and antioxidant function in skeletal muscle. Metabolism. 2012;61:954–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fleischman A, Kron M, Systrom DM, Hrovat M, Grinspoon SK. Mitochondrial function and insulin resistance in overweight and normal-weight children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4923–4930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brands M, van Raalte DH, João Ferraz M, et al. No difference in glycosphingolipid metabolism and mitochondrial function in glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1219–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]