Abstract

Objective

Youth with type 1 diabetes frequently do not achieve glycemic targets. We aimed to improve glycemic control with a Care Ambassador (CA) and family-focused psychoeducational intervention.

Research Design and Methods

In a 2-year, randomized, clinical trial, we compared 3 groups: 1) standard care, 2) monthly outreach by a CA, and 3) monthly outreach by a CA plus a quarterly clinic-based psychoeducational intervention. The psychoeducational intervention provided realistic expectations and problem-solving strategies related to family diabetes management. Data on diabetes management and A1c were collected, and participants completed surveys assessing parental involvement in management, diabetes-specific family conflict, and youth quality of life. The primary outcome was A1c at 2 years; secondary outcomes included maintaining parent involvement and avoiding deterioration in glycemic control.

Results

We studied 153 youth (56% female, median age 12.9 years) with type 1 diabetes (mean A1c 8.4±1.4%). There were no differences in A1c across treatment groups. Among youth with suboptimal baseline A1c ≥8%, more youth in the psychoeducation group maintained or improved their A1c and maintained or increased parent involvement than youth in the other 2 groups combined (77% vs. 52%, p=.03; 36% vs. 11%, p=.01, respectively) without negative impact on youth quality of life or increased diabetes-specific family conflict.

Conclusions

No differences in A1c were detected among the 3 groups at 2 years. The psychoeducational intervention was effective in maintaining or improving A1c and parent involvement in youth with suboptimal baseline glycemic control.

Keywords: Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Patient adherence

Introduction

Contemporary type 1 diabetes management requires adherence to a complex daily therapeutic regimen. For youth with type 1 diabetes, this involves close collaboration between the youth, the family, and the diabetes team. Unfortunately, research has demonstrated that parent involvement diminishes (1;2), and glycemic control deteriorates (3;4) over the course of childhood and adolescence for the majority of youth with type 1 diabetes.

Despite availability of insulin analogs and advanced treatment technologies such as insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors, most youth do not attain optimal targets for glycemic control(5;6). Regular diabetes follow-up clinic visits have been shown to be integral to good glycemic control (7). Additionally, parent involvement in diabetes management is associated with better glycemic control in adolescents (8). Furthermore, family-based behavioral interventions focused on family teamwork around diabetes management have demonstrated positive impacts on glycemic outcomes (9;10).

We designed and evaluated a multi-faceted set of interventions targeting regular clinic follow-up and family involvement. First, we used a nonmedical Care Ambassador (CA) to facilitate care coordination for quarterly clinic visits and to enhance communication between families and clinic staff between visits with monthly outreach(11;12); the Care Ambassador did not provide any medical advice. Next, we created a family-focused teamwork intervention, adapted from our earlier validated interventions (9;10) aimed at improving adherence to diabetes management through realistic expectations and problem-solving strategies.

We designed a 3-arm, randomized, 2-year clinical study of youth with type 1 diabetes aimed at assessing this multi-faceted set of interventions. We compared (1) standard care, which included quarterly clinic visits facilitated by a CA (who assisted only with basic care coordination by scheduling timely quarterly clinic visits), (2) monthly telephonic outreach by a CA in addition to the basic quarterly visit-based care coordination and (3) a family-focused and psychoeducational intervention provided at quarterly clinic visits in addition to the monthly CA telephone outreach and the visit-based care coordination. We evaluated the effects of the interventions on glycemic control, parent involvement in diabetes tasks, and diabetes-specific family conflict.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from a multidisciplinary pediatric diabetes program. Inclusion criteria were: youth age between 8-16 years, type 1 diabetes duration ≥6 months, and established care at our center (as defined by ≥3 visits in the past 2 years or ≥2 visits in the past year if diabetes duration was <1 year). Exclusion criteria included major psychiatric illness, neuro-cognitive disability, another significant medical condition, or unstable living environment as defined by department of social services or department of youth services involvement. The Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and parents/youth provided written informed consent/assent before beginning any study procedures.

Eligible patients were recruited over a four-month period. One hundred seventy-four patients were approached and 154 (89%) agreed to participate in the study. Of the 20 families who declined, 16 families reported a lack of time or interest, two reported family problems, one had concerns regarding privacy and one anticipated moving during the study. One participant was excluded from data analyses because subsequent review revealed ineligibility; the participant had maturity onset diabetes of youth. Of the remaining 153 participants enrolled, 6 participants withdrew before the end of the study because they moved or transferred their care. Another participant had repeated psychiatric hospitalizations; this participant’s data were truncated at the visit preceding the hospitalizations. We conducted an intention-to-treat analysis with the last visit carried forward for the 7 participants with incomplete follow-up. For those who completed the study, the median follow-up time was 2.1 years (range 1.8-2.9 years). For the seven participants with incomplete data, the median follow-up time was 0.9 years (range 0.3-1.1 years).

Participants were randomized in 2 strata according to age (8-12 years or ≥13 years) to one of three groups: Standard Care (SC), Care Ambassador Plus (CA+), or Care Ambassador Ultra (CA+Ultra). The interventions occurred in parallel. Participants provided demographic, clinical, and laboratory evaluations at each visit. SC participants received usual pediatric diabetes subspecialty care including basic care coordination by the Care Ambassador (to assist in scheduling quarterly clinic visits). CA+ participants received monthly outreach by the Care Ambassador via phone or email, in addition to the quarterly diabetes care and care coordination given to the SC group. Finally, CA+Ultra participants received a psychoeducational intervention conducted at quarterly study visits (see below), in addition to monthly outreach and quarterly diabetes care and care coordination.

A CA was a research assistant with a 4-year college degree and no medical background who was trained in study protocol implementation and care coordination. The Care Ambassador role included outreach to families toschedule clinic appointments or to relay family concerns to medical providers (11;12). Care Ambassadors did not give medical advice. The CA also delivered the psychoeducational intervention to the CA+Ultra group using a manualized curriculum.

The psychoeducational intervention, adapted from our earlier validated materials (9;10), consisted of a 30-minute session with participants and their parent/guardian on the day of a regularly scheduled, quarterly clinic visit. The psychoeducational materials related to family management of diabetes. The CA facilitated problem-solving exercises and role-playing of realistic expectations for family teamwork. Senior study staff monitored the study integrity and fidelity by review of taped intervention sessions. Session topics included: (1) Family teamwork and communication; (2) Avoiding perfectionism and setting realistic goals; (3) Blood sugar monitoring and A1C; (4) Avoiding family conflict related to diabetes; (5) Weight gain and hypoglycemia awareness; (6) Decreasing feelings of burnout and isolation (7) Sessions in review and (8) Research and technology update. Contact the authors for further information about the psychoeducational intervention materials.

Surveys

Youth and parents completed surveys at baseline, one year, and two years. Three families completed only the initial survey assessment and their data were excluded from the analysis of survey results. Three families completed only baseline and one year survey data and their one year survey data were carried forward in the analysis.

Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire

Youth and parents independently completed the Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire (DFRQ) (13) which measures parental involvement in diabetes management tasks such as checking blood sugars. On this 17-item questionnaire, participants chose between four response options on each item to rate who had primary responsibility for each task (child/teen responsibility, equal responsibility, parent responsibility and not applicable) with possible total scores ranging from 17-51, adjusting for any missing items. Responses of ‘not applicable’ were scored the same as missing. Higher scores indicate more parental involvement. Youth and parent scores were strongly correlated (R= 0.7, p<.0001) and so we used the mean of parent and youth scores in our analyses.

Diabetes Family Conflict Scale

Youth and parents independently completed the validated revised Diabetes Family Conflict Scale (DFCS) (14) which measures diabetes-specific family conflict regarding tasks such as remembering to check blood sugars or scheduling doctor and dental visits. On this 19-item questionnaire, participants chose among three response options (never argue, sometimes argue, always argue) with possible scores ranging from 19-57. Higher scores indicate more conflict. Because parent and youth scores were not strongly correlated (R=0.4, p<.0001), we present parent and youth scores separately.

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory—Generic Core Scales (PedsQL)

Youth and parents completed the validated PedsQL—Generic Core Scales (15) (youth and parent proxy versions) which measures youth health-related quality of life in two domains: physical and psychosocial (includes emotional, school and social functioning). On this 23-item questionnaire, respondents chose between five response options (never, almost never, sometimes, often, almost always) to indicate how much an item had been a problem in the past 1 month. Responses were linearly transformed and reverse-scored to produce a possible total score range from 0-100. Higher scores indicate better youth health-related quality of life. Parent and youth scores were not strongly correlated (R=0.4, p<.0001), thus parent proxy and youth scores are reported separately.

Outcome Variable: A1c

A1C was measured at routine quarterly visits by high performance liquid chromatography (ref. range 4.0-6.0%; Tosoh 2.2, Tosoh Corp., Foster City, CA). In order to look at the cumulative effect of the intervention over the time, we also looked at the average A1c beginning at the third visit, corresponding to a median time enrolled of 6.6 months. This visit was selected as it followed the implementation of the psychoeducational intervention for the Ca+Ultra group at visit 2.

Additional Variables

At study entry, parents provided demographic information and chart review yielded physical exam and treatment information. Pubertal stage at entry reflected the most recent exam in which pubertal staging was assessed. Pubertal stage was categorized into three categories (prepubertal, pubertal, and post-pubertal). Body mass index (BMI) z-scores were calculated according to standardized tables (16). The frequency of blood glucose monitoring was provided by clinician report at the clinical visit. Clinicians used a combination of glucose data from the meter download and/or logbook to determine blood glucose monitoring frequency. If clinician report was not available, participant report was used.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For the baseline data and bivariate analyses, continuous variables were compared using unpaired T tests or Wilcoxon rank sum depending upon the distribution of the data. Fisher Exact Test was used for categorical analysis for 2×2 tables and chi-squared analyses were used with >2 categories. Because the distribution of sex and race/ethnicity were significantly different among the groups, multivariate analyses were adjusted for sex and race/ethnicity. We also adjusted for baseline values of the outcome of interest in multivariate analyses. For continuous outcomes, MANOVA was done using the Tukey method for multiple comparisons within the same model and means and standard deviations are presented. Because of the unequal distribution of demographic characteristics among the groups, the OBSMARGINS function was used to estimate the means. This provides estimates according to the actual proportions assigned to the groups instead of assuming a balanced distribution among the groups. For binary outcomes, logistic regression was used and odds ratios and associated p values are presented. Because past research has demonstrated deterioration in adherence to diabetes management and glycemic control with increased duration of diabetes and progression through adolescence (4;17), the proportion of participants that maintained or improved their outcomes was evaluated using logistic regression.

Subgroup Analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis to evaluate those with suboptimal baseline glycemic control (A1C ≥8%). An A1C ≥8% was defined as suboptimal because it is above the American Diabetes Association goal for 6-12 year olds with diabetes (18). An additional subgroup analysis was aimed at evaluating the effect of the psychoeducational intervention in those with suboptimal glycemic control. Thus, SC and CA+ groups were combined into one group designated SC/CA+ as these two groups did not receive the psychoeducational intervention.

Results

Overall, participants (N=153, 56% female) had a median age of 12.9 years (range 8.2-16.5), median diabetes duration of 6.1 years (range 0.8-14.3), with 15% on 2 injections per day and 85% on some form of intensive insulin therapy (see details in Table 1) and a mean A1c 8.4±1.4%. The three groups were comparable with regards to age, diabetes duration, proportion on insulin pump, frequency of blood glucose monitoring, A1c, pubertal stage, parental involvement in diabetes management, parent- and child-report of diabetes-specific family conflict, and parent proxy-report and child self-report of youth QOL at baseline (Table 2). There were statistically significant differences in sex and race/ethnicity between the SC and CA+ groups, suggesting the need to adjust for these in the multivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| SC | CA+ | CA+Ultra | |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | (n=51) | (n=52) | (n=50) |

| Age (years) | 12.5±2.3 | 13.4±2.4 | 12.7±2.2 |

| Diabetes Duration (years) | 5.7±3.5 | 6.8±3.2 | 6.5±3.8 |

| A1C (%) | 8.4 ±1.3 | 8.6±1.6 | 8.4±1.4 |

| BG Monitoring (times/day) | 3.8±1.3 | 3.8±1.3 | 3.8±1.0 |

| zBMI (SDS) | 0.6± 0.8 | 0.9±0.7 | 0.8±0.7 |

| Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| Sex (% female)* | 45 | 65 | 58 |

| Race/Ethnicity (% non-white)* | 2 | 15 | 10 |

| A1c ≥8% (%) | 55 | 58 | 52 |

| Insulin regimen (Injection Based) (%) | 80 | 73 | 78 |

| Pubertal Status (%) | |||

| Prepubertal | 25 | 17 | 22 |

| Pubertal | 55 | 42 | 48 |

| Post-Pubertal | 20 | 40 | 30 |

| Highest Parental Education (%) | |||

| High School or Less | 14 | 15 | 6 |

| Some College | 18 | 17 | 30 |

| College Degree or More | 69 | 67 | 64 |

Mean ± standard deviation presented.

p <.05 for difference between SC and CA+

Table 2.

Adjusted Baseline and 2 year Comparisons in the 3 groups

| Baseline | 1 Year | 2 Years | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | CA+ | CA+Ultra | SC | CA+ | CA+Ultra | SC | CA+ | CA+Ultra | |

| A1c (%) | 8.5±1.4 | 8.5±1.4 | 8.3±1.4 | 8.6±0.9 | 8.7±0.9 | 8.5±0.9 | 8.6±1.0 | 8.8±1.0 | 8.6±1.0 |

| Average A1c (%) | 8.6±0.8 | 8.7±0.8 | 8.6±0.8 | ||||||

| BG Monitoring (x/day) |

3.7±1.2 | 3.9±1.2 | 3.9±1.2 | 4.0±1.3 | 3.6±1.3 | 3.6±1.3 | 3.8±1.4 | 3.3±1.3 | 3.9±1.3 |

| Parent diabetes involvement# |

36.3±4.8 | 35.0±4.8 | 36.6±4.7 | 35.2±3.0 | 34.2±3.0 | 34.6±2.9 | 33.2±3.4 | 32.1±3.4 | 33.8±3.3 |

| Diabetes-specific family conflict | |||||||||

| Parent report | 24.1±3.9 | 24.4±3.8 | 24.3±3.8 | 25.2±4.4 | 24.8±4.4 | 25.5±4.4 | 25.2±4.3 | 24.1±4.3 | 25.6±4.1 |

| Child report | 24.4±5.1 | 25.4± 5.1 | 24.5±5.1 | 24.2±4.4 | 23.4±4.4 | 24.3±4.3 | 24.8±5.0 | 23.4±5.0 | 24.9±4.8 |

| Child Quality of Life | |||||||||

| Parent proxy | 78.7±19.4 | 79.9±17.3 | 81.3±18.1 | 84.7±11.9 | 82.0±11.8 | 80.1±11.7 | 81.9±11.4 | 85.2±11.3 | 81.7±11.0 |

| Child report | 84.1±11.7 | 81.8±11.7 | 84.6±11.6 | 84.9±7.6 | 85.0±7.6 | 85.7±7.5 | 83.3±8.6 | 85.9±8.6 | 85.4±8.3 |

Means± standard deviation presented.

All values adjusted for race/ethnicity and sex, 1 and 2 year values adjusted for baseline value;

2 year comparison between CA+ and CA+Ultra, significant to p=0.04

Process of Care

The total number of diabetes follow-up visits for participants in the study generally met the recommended every 3 months interval with 9.6±1.1 visits in the SC group, 9.0±1.7 visits in the CA+ group, and 9.4±1.5 visits in the CA+Ultra group over a median of 2.1 years (range 0.3-2.9 years) of study participation. This supports the success of the basic care coordination given to all 3 groups by the CA in ensuring recommended follow-up diabetes care (and thereby matching for visit frequency among the three groups).

One Year Study Outcomes

There were no differences among the groups at one year (Table 2).

Two Year Study Outcomes

In bivariate analyses, no differences were demonstrated among the 3 groups in glycemic control (mean±SD of SC, CA+ and CA+Ultra: 8.5±1.3%, 9.0±1.7% and 8.6±1.3%, respectively) at study end. Differences in sex and race/ethnicity may influence glycemic outcomes (4;19) and thus we accounted for them in our multivariate analyses. Multivariate analyses adjusting for sex, race/ethnicity, and baseline values of the outcome of interest were similar to bivariate results and are presented in Table 2. There were also no differences in the primary outcome of glycemic control after accounting for differences in baseline values. There were no differences in diabetes-specific family conflict or youth quality of life among the three groups. The only significant difference among the groups was greater parental involvement in CA+Ultra vs. CA+ (p=0.04).

There were no differences in the odds of maintaining or improving A1c among the three groups. Both the SC and CA+Ultra groups had greater odds of maintaining or increasing the frequency of blood glucose monitoring versus the CA+ group (OR: 3.0; 95% CI 1.2-7.7 for SC vs CA+ and OR: 2.8; 95% CI 1.1-6.8 for CA+Ultra vs CA+). The CA+Ultra group had almost 5 times the chance of maintaining or increasing parental involvement in diabetes management at 2 years versus CA+ (OR: 4.9; 95% CI 1.6-15.6) and had a trend towards increased odds maintaining or increasing parental involvement versus SC (OR 2.5; 95% CI 0.9-7.4).

Subgroup Analyses of Participants with Baseline A1c ≥8%

In order to determine the impact of the interventions in youth with the greatest need for improvement, we performed a sub-analysis of participants with baseline A1c ≥8.0% (SC n=28, CA+ n = 30, CA+Ultra n = 26). At baseline, this subgroup displayed similar unequal distributions according to racial/ethnic minority status (SC 4%, CA+ 23%, and CA+Ultra intermediate at 15%). Participants in CA+Ultra had greater odds of maintaining or improving their A1c versus those in CA+ (OR 3.7, CI 1.1-12.7) with similar findings in the comparison of CA+Ultra versus SC (OR 3.4, CI 1.0-11.9). Participants in CA+Ultra also had greater odds of maintaining or improving parental involvement in diabetes management versus those in CA+ (OR 13.0, CI 2.0-83.3) and nonsignificantly greater odds versus SC (OR 3.6, CI 0.8-15.6).

To assess the effects of the psychoeducational intervention in those with suboptimal baseline glycemic control, we combined SC and CA+, as these two groups did not receive the psychoeducational intervention. There were no significant differences between SC/CA+ (n=58) and CA+Ultra (n=26) in baseline characteristics (Table 3). There were also no significant differences in the bivariate analyses of A1c, blood glucose monitoring frequency, parental involvement, diabetes-specific family conflict, or youth quality of life. In bivariate analyses, about 50% more participants in CA+Ultra than SC/CA+ maintained or improved their A1c (77% vs. 52%, p=.03). In addition, more than three times as many families maintained or increased their parental involvement in diabetes management in the CA+Ultra group versus SC/CA+ groups (36% vs 11%, p=.03).

Table 3.

Adjusted Baseline and 2 year Comparisons in those Not Receiving vs. Receiving the Psychoeducational Intervention among Participants with Suboptimal Baseline Glycemic Control

| Baseline | 1 Year | 2 Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC/CA+ (n=58) |

CA+Ultra (n=26) |

SC/CA+ | CA+Ultra | SC/CA+ | CA+Ultra | |

| A1c (%) | 9.4±1.2 | 9.3±1.2 | 9.4±1.0 | 9.2±1.0 | 9.4±1.1 | 9.1±1.1 |

| Average A1c (%) | 9.4±0.9 | 9.2±0.9 | ||||

| BG Monitoring (times/day) |

3.6± 0.9 | 3.6±0.9 | 3.4±0.9 | 3.4±0.9 | 3.2±1.2 | 3.4±1.2 |

| Parent diabetes involvement |

36.5±4.5 | 36.4±4.5 | 35.1±2.8 | 35.7±2.8 | 33.2±3.8 | 34.8±3.5 |

| Diabetes-specific family conflict | ||||||

| Parent report | 24.3±3.7 | 25.2±3.7 | 25.3±3.3 | 25.0±3.3 | 25.2±4.8 | 26.3±4.8 |

| Child report | 25.6±5.1 | 25.2±5.2 | 24.5±4.8 | 24.9±4.8 | 24.5±5.4 | 26.4±5.4 |

| Child Quality of Life | ||||||

| Parent proxy | 78.9±13.9 | 80.8±13.9 | 81.6±11.5 | 77.9±11.5 | 82.1±10.7 | 79.9±10.8 |

| Child report | 81.6±11.8 | 84.8±11.8 | 84.3±7.8 | 85.5±7.8 | 83.7±9.4 | 83.5±9.5 |

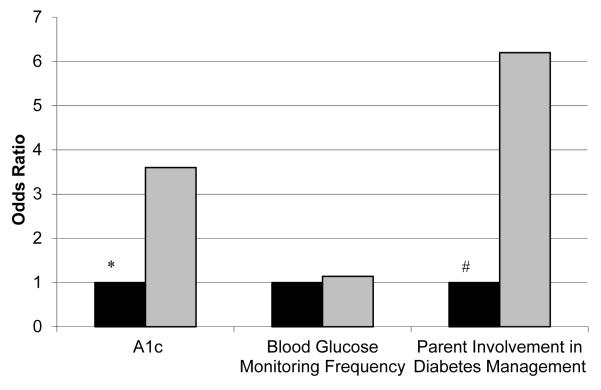

In multivariate analyses, there were not significant differences between the groups at one year (Table 3). After 2 years, the adjusted A1C (mean±SD) in participants with initial A1c ≥8.0% was comparable (9.4±1.5 in SC/CA+ and 9.1±1.5 in CA+Ultra; Table 3). The odds of maintaining or increasing blood glucose monitoring frequency did not differ between the groups (CA+Ultra vs SC/CA+ OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.4-3.1, Figure 1). The CA+Ultra group had more than 3 times the odds of maintaining or improving their A1C versus the SC/CA+ group (OR 3.6; 95% CI 1.2-10.8). The CA+Ultra group also had increased odds of maintaining or increasing parental involvement (OR 6.2; 1.7-22.9). There was no difference in child- or parent-reported diabetes-specific family conflict in the CA+Ultra group versus SC/CA+ groups associated with the increased family involvement. There were no differences in the child’s quality of life as reported by parents or youth in CA+Ultra group versus SC/CA+ groups.

Figure 1.

Odds of Maintenance or Improvement in Selected Study Outcomes in those with Suboptimal Baseline Glycemic Control, SC/CA+ (■) in Comparison with CA+Ultra ( ), * p=.02, # p=.006.

), * p=.02, # p=.006.

Discussion

In this three-arm, randomized clinical trial of gradations of care coordination with and without a family-focused psychoeducational intervention, we achieved a uniform process of care delivery with clinic visits at 3-4 month intervals as recommended by the American Diabetes Association (18). We anticipated that greater intensity of care coordination with or without psychoeducation could improve A1c but we were unable to detect any differences between the groups. Psychoeducation involving problem-solving, parent involvement in diabetes management, and setting realistic expectations for diabetes care did not yield differences in glycemic outcomes in the entire sample. However, in subgroup analyses of those with suboptimal baseline glycemic control, the psychoeducational intervention was associated with maintained or improved A1c and maintained or increased parent involvement in diabetes management tasks at 2 years although no differences were detectable using continuous measures. Notably, the maintained involvement was not associated with an increase in diabetes-specific family conflict.

Like previous studies at our center, this study utilized a CA to provide care coordination (11;12). In an earlier study (12), those receiving care coordination by a CA had more clinic visits and fewer episodes of severe hypoglycemia, emergency room visits and hospitalizations than controls; the effect was greatest in those with poor baseline glycemic control. In another study (11), the group receiving the psychoeducational intervention in addition to care coordination from a CA demonstrated lower rates of hypoglycemia, emergency department use, and hospitalization. In participants with poor glycemic control, the psychoeducational intervention was significantly related to maintenance or improvement in A1c.

Since lay care coordination altered the process of care through improved clinic visit frequency and decreased acute events in our clinic population, basic care coordination has become standard of care in our clinic during the patient’s first year of clinic attendance. Thus, the standard care group in our study incorporated some basic care coordination to facilitate matching for attendance at clinic visits across study groups. This study aimed to evaluate monthly outreach and monthly outreach supplemented by quarterly psychoeducation. Our study suggests that monthly outreach does not lead to added benefit when participants are already adherent to quarterly clinic visits. Another possibility is that in the current era of alternative outlets for social support using community and technology-based diabetes websites (20), monthly case management outreach does not offer unique benefits to families. The psychoeducational intervention was also ineffective in the entire population. This may demonstrate the difficulty of improving glycemic control through a psychoeducational intervention in those youth that are already adherent to diabetes management as demonstrated by their A1c. Alternatively, it could indicate that the quarterly frequency of the intervention was not intense enough to impact behavior substantially in the entire sample.

Consistent with our previous investigations validating the efficacy of family teamwork (9-11), the current studies demonstrates maintenance or improvement in A1c in those youth receiving the psychoeducational intervention who had a suboptimal baseline A1c. However, it is notable that there was not a significant absolute difference in A1c from baseline to 2 years in this group.Youth with suboptimal glycemic control remain at the highest risk for acute (21) and chronic complications (22). In these youth, maintaining or improving glycemic control was accompanied by avoiding diminished parent involvement in diabetes management. Previous research has demonstrated both a decline in glycemic control (4;17) and in family involvement in diabetes management (23) over the course of adolescence.

Parent involvement has been shown to be an important protective factor in promoting diabetes adherence and glycemic control (24). Greater collaborative involvement by both parents is correlated with better glycemic control and treatment adherence (8). Additionally, parental supervision of diabetes-specific tasks is related to better adherence to diabetes management in adolescents with diabetes (25). While such non-interventional research has suggested that maintaining parent involvement during adolescence is associated with better adherence to diabetes management and better glycemic control, a number of interventional studies of youth with type 1 diabetes performed outside of routine clinical care have had mixed results (26-28). Nonetheless, in a recent meta-analysis (29) of pediatric type 1 diabetes interventional studies with adherence-promoting components, the authors note that, in general, the effect of adherence-promoting interventions on glycemic control has been modest but can be enhanced when the interventions target multiple processes such as family functioning and problem-solving in addition to adherence. Our intervention targeted multiple processes such as teamwork, problem-solving, and setting realistic expectations. In addition, our intervention offered the ease of delivery at the time of routine clinic appointments and therefore may be less expensive than alternatives that are not clinic-based.

Our study has three notable limitations. First, there were demographic imbalances among the groups after randomization. Second, differences among the groups were only demonstrated in post-hoc analyses. Third, we designed the study as a 3 group comparison rather than a 2×2 factorial design. A 2×2 factorial design would have allowed us to isolate the impact of the psychoeducational intervention alone from the psychoeducational intervention combined with monthly outreach, which the present design did not allow us to do. Future studies could incorporate new research demonstrating the importance of effective parenting styles in diabetes management (30) as well as approaches that incorporate both group visits and family sessions since the latter may be promising in this age group (31). Future interventions could also use text messaging, message boards, and video conferencing as a means to intensify the intervention without substantially increasing costs.

The current study is important in that it expands on our previous work (9-11) utilizing a trained layperson to deliver a family-focused clinic-based psychoeducational intervention for youth with type 1 diabetes and their families. Additionally, it demonstrates that monthly outreach to patients with type 1 diabetes may not be beneficial when families already demonstrate adherence to quarterly clinic visits. This randomized, low-cost, low intensity intervention evaluated in a large cohort of youth with type 1 diabetes was able to demonstrate limited efficacy in those with suboptimal glycemic control, suggesting this sub-population as a promising target for future psychoeducational interventions. Notably, it is this population of youth unable to achieve target A1c levels that remain at highest risk for both acute and chronic diabetes complications. Despite recent technological advances both in diabetes management and in communication modalities, improving adherence and glycemic control remain important therapeutic targets for youth with type 1 diabetes and their families.

Acknowledgements

Lori Laffel, MD, MPH is the guarantor of this work. MLK conducted analyses, wrote manuscript, contributed to discussion. BJA researched data, contributed to discussion, reviewed/edited manuscript. LKV researched data, contributed to discussion, reviewed/edited manuscript. DAB researched data and contributed to discussion. LML researched data, contributed to manuscript writing and discussion, reviewed/edited manuscript. Research support from the Charles H. Hood Foundation, the Katherine Adler Astrove Youth Education Fund, the Maria Griffin Drury Pediatric Fund, the Eleanor Chesterman Beatson Fund, NIH T32 DK 7260-35 to the Joslin Diabetes Center, Health Resources and Services Administration grant T32 HP10018 to the Harvard Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship Program, K12 DK094721-02 to the Joslin Diabetes Center/Children’s Hospital Boston and grant P30DK036836 to the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center.

Footnotes

None of the authors has any relevant conflicts of interest.

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the 71st Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association (2011).

Reference List

- (1).Ingerski LM, Anderson BJ, Dolan LM, Hood KK. Blood glucose monitoring and glycemic control in adolescence: contribution of diabetes-specific responsibility and family conflict. J Adolesc Health. 2010 Aug;47(2):191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Schilling LS, Knafl KA, Grey M. Changing patterns of self-management in youth with type I diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2006 Dec;21(6):412–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mortensen HB, Robertson KJ, Aanstoot HJ, Danne T, Holl RW, Hougaard P, Atchison JA, Chiarelli F, Daneman D, Dinesen B, Dorchy H, Garandeau P, Greene S, Hoey H, Kaprio EA, Kocova M, Martul P, Matsuura N, Schoenle EJ, Sovik O, Swift PG, Tsou RM, Vanelli M, Aman J. Insulin management and metabolic control of type 1 diabetes mellitus in childhood and adolescence in 18 countries. Hvidore Study Group on Childhood Diabetes. Diabet Med. 1998 Sep;15(9):752–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199809)15:9<752::AID-DIA678>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Bryden KS, Peveler RC, Stein A, Neil A, Mayou RA, Dunger DB. Clinical and psychological course of diabetes from adolescence to young adulthood: a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2001 Sep;24(9):1536–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Paris CA, Imperatore G, Klingensmith G, Petitti D, Rodriguez B, Anderson AM, Schwartz ID, Standiford DA, Pihoker C. Predictors of insulin regimens and impact on outcomes in youth with type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. J Pediatr. 2009 Aug;155(2):183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 2;359(14):1464–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kaufman FR, Halvorson M, Carpenter S. Association between diabetes control and visits to a multidisciplinary pediatric diabetes clinic. Pediatrics. 1999 May;103(5 Pt 1):948–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wysocki T, Nansel TR, Holmbeck GN, Chen R, Laffel L, Anderson BJ, Weissberg-Benchell J. Collaborative involvement of primary and secondary caregivers: associations with youths’ diabetes outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 Sep;34(8):869–81. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Laffel LM, Vangsness L, Connell A, Goebel-Fabbri A, Butler D, Anderson BJ. Impact of ambulatory, family-focused teamwork intervention on glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2003 Apr;142(4):409–16. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Anderson BJ, Brackett J, Ho J, Laffel LM. An office-based intervention to maintain parent-adolescent teamwork in diabetes management: Impact on parent involvement, family conflict, and subsequent glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 1999 May;22(5):713–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Svoren B, Butler D, Levine B, Anderson B, Laffel L. Reducing acute adverse outcomes in youths with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):914–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Laffel LM, Brackett J, Ho J, Anderson BJ. Changing the process of diabetes care improves metabolic outcomes and reduces hospitalizations. Qual Manag Health Care. 1998 Sep;6(4):53–62. doi: 10.1097/00019514-199806040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Anderson BJ, Auslander WF, Jung KC, Miller JP, Santiago JV. Assessing family sharing of diabetes responsibilities. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990 Aug;15(4):477–92. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hood KK, Butler DA, Anderson BJ, Laffel LMB. Updated and revised Diabetes Family Conflict Scale. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(7):1764–9. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001 Aug;39(8):800–12. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002 May;11(246):1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Helgeson VS, Siminerio L, Escobar O, Becker D. Predictors of metabolic control among adolescents with diabetes: a 4-year longitudinal study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 Apr;34(3):254–70. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes--2012. Diabetes Care. 2012 Jan;35(Suppl 1):S11–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Klingensmith G, Miller KM, Beck RW, Cruz E, Laffel LM, Lipman T, Schatz DA. Racial Disparities in Insulin Pump Therapy and Hemoglobin A1c Among T1D Exchange Participants. Diabetes. 2012;61(Suppl 1):A358. Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zrebiec JF. Internet communities: do they improve coping with diabetes? Diabetes Educ. 2005 Nov;31(6):825–2. 834, 836. doi: 10.1177/0145721705282162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rewers A, Chase HP, Mackenzie T, Walravens P, Roback M, Rewers M, Hamman RF, Klingensmith G. Predictors of acute complications in children with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2002 May 15;287(19):2511–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).White NH, Cleary PA, Dahms W, Goldstein D, Malone J, Tamborlane WV. Beneficial effects of intensive therapy of diabetes during adolescence: outcomes after the conclusion of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) J Pediatr. 2001 Dec;139(6):804–12. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.118887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Anderson B, Ho J, Brackett J, Finkelstein D, Laffel L. Parental involvement in diabetes management tasks: relationships to blood glucose monitoring adherence and metabolic control in young adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 1997 Feb;130(2):257–65. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Siminerio L, Escobar O, Becker D. Parent and adolescent distribution of responsibility for diabetes self-care: links to health outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008 Jun;33(5):497–508. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ellis DA, Podolski CL, Frey M, Naar-King S, Wang B, Moltz K. The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: impact on regimen adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007 Sep;32(8):907–17. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ambrosino JM, Fennie K, Whittemore R, Jaser S, Dowd MF, Grey M. Short-term effects of coping skills training in school-age children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008 Jun;9(3 Pt 2):74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wysocki T, Harris MA, Buckloh LM, Mertlich D, Lochrie AS, Taylor A, Sadler M, White NH. Randomized, controlled trial of Behavioral Family Systems Therapy for Diabetes: maintenance and generalization of effects on parent-adolescent communication. Behav Ther. 2008 Mar;39(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ellis D, Naar-King S, Templin T, Frey M, Cunningham P, Sheidow A, Cakan N, Idalski A. Multisystemic therapy for adolescents with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes: reduced diabetic ketoacidosis admissions and related costs over 24 months. Diabetes Care. 2008 Sep;31(9):1746–7. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hood KK, Rohan JM, Peterson CM, Drotar D. Interventions with adherence-promoting components in pediatric type 1 diabetes: meta-analysis of their impact on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jul;33(7):1658–64. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Shorer M, David R, Schoenberg-Taz M, Levavi-Lavi I, Phillip M, Meyerovitch J. Role of parenting style in achieving metabolic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011 Aug;34(8):1735–7. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Grey M, Whittemore R, Jaser S, Ambrosino J, Lindemann E, Liberti L, Northrup V, Dziura J. Effects of coping skills training in school-age children with type 1 diabetes. Res Nurs Health. 2009 Aug;32(4):405–18. doi: 10.1002/nur.20336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]