Abstract

Background

Low muscle strength is central to geriatric syndromes including sarcopenia and frailty. It is well described in community dwelling older people but the epidemiology of grip strength of older people in rehabilitation or long term care has been little explored.

Objective

To describe grip strength of older people in rehabilitation and nursing home settings.

Design

Cross-sectional epidemiological study.

Setting

3 healthcare settings in one town.

Subjects

101 inpatients on a rehabilitation ward, 47 community rehabilitation referrals and 100 nursing home residents.

Methods

Grip strength, age, height, weight, body mass index, number of co-morbidities and medications, Barthel score, mini mental state examination (MMSE), nutritional status, and number of falls in the last year were recorded.

Results

Grip strength differed substantially between healthcare settings for both men and women (p<0.0001). Nursing home residents had the lowest age-adjusted mean grip strength and community rehabilitation referrals the highest. Broadly higher grip strength was associated in univariate analyses with younger age, greater height and weight, fewer comorbidities, higher Barthel score, higher MMSE score, better nutritional status and fewer falls. However after mutual adjustment for these factors, the difference in grip strength between settings remained significant. Barthel score was the characteristic most strongly associated with grip strength.

Conclusions

Older people in rehabilitation and care home settings had lower grip strength than reported for those living at home. Furthermore grip strength varied widely between healthcare settings independent of known major influences. Further research is required to ascertain whether grip strength may help identify people at risk of adverse health outcomes within these settings.

Keywords: grip strength, older, healthcare setting, rehabilitation, nursing home

INTRODUCTION

Characterisation of muscle strength is important because loss of strength is central to a number of major geriatric syndromes including sarcopenia (1), frailty (2), mobility impairment (3) and falls (4). Low muscle strength is also associated with poor future health. Among community dwelling adults, it has been found to be predictive of increased future functional limitations and disability (5) (6) (7), increased fracture risk (8;9), development of chronic diseases (10;11), higher risk of cognitive decline (8;12), and increased all-cause mortality (13), particularly for those aged over 60 years.

Grip strength is recommended as a ‘good simple measure’ of muscle strength (14), with the caveat that grip strength should be measured with a well-studied model of dynamometer in standard conditions and with known reference populations. The Jamar dynamometer is the most widely used with established reliability and reproducibility (15) and standardised protocols have been described (16). However, grip strength values such as the widely reported ‘consolidated norms’ developed by Bohannon et al from a meta-analysis of 12 studies from 5 countries are derived from community dwelling adults (17), and no studies report grip strength values for patients in rehabilitation healthcare settings or residents in care homes although Roberts et al have reported that relatively lower grip strength was associated with a longer length of stay within an in-patient rehabilitation setting (18).

The aim of this study was to describe grip strength, and its cross-sectional associations with clinical characteristics, among older men and women undergoing in-patient rehabilitation, community based rehabilitation and resident in nursing homes.

METHODS

Participants

This cross-sectional epidemiological study was conducted in one town in England. Patients aged 70 years and over were prospectively recruited from in-patient rehabilitation at the community hospital, referrals to the community rehabilitation team for physiotherapy, and residents of five local nursing homes (one registered for general nursing care, one for dementia care, three dual registered). Exclusion criteria included inability to give written informed consent or hold the dynamometer, terminal phase of illness (on / about to be started on the Liverpool Care pathway for the dying), and researcher unable to review participants within one week of admission to hospital or four weeks of community referral. The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee.

Data collection

Participants’ demographic details, dates of admission or referral, current weight and body mass index (BMI), co-morbidities and current medications were abstracted from their clinical records. Grip strength was measured three times with each hand using a Jamar hand dynamometer (Promedics, UK) according to a standard protocol with standardised encouragement (15). Maximum grip strength was recorded to the nearest 1kg. Height was calculated from forearm length (cm) (19) since many participants were unable to stand. All in-patients and nursing home residents had current weights in their records and the community referrals were weighed to the nearest 0.1kg on standing scales such that their BMI could be calculated. Physical function was assessed using the 100 point Barthel Score (maximum score 100, higher scores representing greater independence) (20). The number of self-reported falls in the last year was recorded and corroborated with medical records or care staff where possible to improve the reliability of these data. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to assess cognitive function (maximum score 30 points representing intact cognition, < 24 points representing impaired cognition) (21). The ‘malnutrition universal screening tool’ (‘MUST’) score (22) was assessed for each participant.

Statistical analyses

The database was created by double entry, and cleaned and prepared for use with the Stata statistical software package (StataCorp, Texas, 2010). Descriptive statistics (number, percentage) were used to report participant recruitment rates and reasons for exclusion in each healthcare setting.

Participants’ characteristics including age, anthropometry, numbers of co-morbidities and medications, grip strength, Barthel score, MMSE score, ‘MUST’ score and falls were described using summary statistics: means and standard deviations (SD), medians and inter quartile ranges (IQR), and number (percentage) were presented for each healthcare setting. The ‘MUST’ score was re-coded from five categories (score of zero representing low risk of malnutrition, one (modest risk), two (high risk), three and four representing extremely high risk) to three categories (score 0, 1, and 2-4) since a score of two or more is used clinically to denote a high risk of malnutrition and very few participants scored above two. There was a large range in the number of falls (0 – 352) in the last year, although only 28 people had fallen more than five times. The number of falls was therefore recoded into three categories: none, one, and two or more falls, since clinically two or more falls denotes a higher risk of further falls.

The men were taller and heavier than the women in each healthcare setting and since body size is associated with grip strength data were presented by gender and setting throughout. Men and women were compared within each setting using the 2-sample t-test, Mann-Whitney test and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Men or women were compared between healthcare settings using ANOVA, the Kruskal-Wallis test and Fisher’s exact test.

Maximum grip strength was described using means (standard deviation) and percentiles for men and women separately in each setting with and without adjustment for age. The mean maximum grip strength for men and women was compared within each setting using the 2-sample t-test, and between study settings using ANOVA. The associations of maximum grip with participants’ clinical characteristics - the number of co-morbidities and medications, the Barthel, MMSE and MUST scores and the number of falls during the last year - were analysed individually for men and women separately in each setting using linear regression analysis. Participants’ height and weight were strongly correlated and so a standardised residual of weight adjusted for height (‘weight-for-height’) was derived for inclusion in regression analysis. Thus results were presented adjusted for age, height and weight-for-height, using regression estimates with confidence intervals, and statistical significance was indicated using P-values.

RESULTS

Recruitment

101/ 137 eligible rehabilitation in-patients (37 men, 64 women; 41% admitted from acute hospital, 59% from home) were prospectively consecutively recruited a median of 4 days after admission (IQR 2 – 6). 47 / 94 eligible patients (24 men, 23 women) referred to the community rehabilitation team were recruited, with a median time between initial assessment and recruitment of 8 days (IQR 6 - 14). 100 /111 eligible nursing home residents (35 men, 65 women) were recruited with a median duration of residence of 298 days (IQR 106 - 727): since these participants were medically stable there was no time constraint on time from admission to recruitment.

Description of participants

Men were significantly taller than women within each setting (p<0.0001), and heavier (except among the community rehabilitation referrals). Age and body size also varied between settings with the community rehabilitation referrals being the youngest and heaviest (Table 1). There was a median of four co-morbidities for men and women in all three settings. There was a similar prevalence of hypertension and stroke in all settings: falls and fracture were common among the inpatients, and osteoarthritis and joint replacement among the community rehabilitation patients. Poor mobility and dementia were common among the nursing home residents. However there was a significant difference in the number of medications for both men and women across settings, with inpatients taking the most (median of eight). The Barthel and MMSE scores were both highest among the community referrals and lowest among nursing home residents, with a significant difference for both men and women between settings (p=0.0001).

Table 1. Description of Participants’ Characteristics by Setting.

| Mean (SD) | Hospital Rehabilitation Inpatients |

Community Rehabilitation Referrals |

Nursing Home Residents | P valued | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (N=37) | Female (N=64) | Male (N=24) | Female (N=23) | Male (N=35) | Female (N=65) | |||

| Age (years) | 82.6 (5.6) | 84.9 (6.2) | 79.2 (5.5) | 79.4 (5.8) | 85.1 (7.6) | 87.5 (6.4) | M 0.003; | |

| P valuec | P=0.07 | P=0.88 | P=0.10 | F<0.0001 | ||||

| Height (cm) | 170.9 (3.5) | 157.9 (4.0) | 173.3 (4.7) | 162.0 (5.4) | 172.8 (5.7) | 156.6 (5.3) | M 0.10; | |

| P valuec | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | F 0.0001 | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 70.1 (11.9) | 57.9 (15.7) | 79.5 (13.6) | 75.0 (17.0) | 70.1 (11.0) | 58.4 (11.4) | M 0.007; | |

| P valuec | P=0.0001 | P=0.33 | P<0.0001 | F<0.0001 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 (3.9) | 23.1 (5.8) | 26.5 (4.2) | 28.6 (6.5) | 23.4 (3.2) | 23.9 (5.1) | M 0.01; | |

| P valuec | P=0.42 | P=0.20 | P=0.64 | F0.0004 | ||||

| Number of comorbiditiesa | 4(3,5) | 4 (3,5.0) | 4 (3,5.5) | 4 (3,5) | 4 (3,6) | 4 (3,5) | M 0.32; | |

| P valuec | P=0.63 | P=0.37 | P=0.63 | F 0.37 | ||||

| Number of medicationsa | 8 (7,10) | 8 (6,11) | 6 (3.5,7.5) | 7(4,8) | 6 (5,7) | 7 (5,8) | M 0.004; | |

| P valuec | P=0.87 | P=0.77 | P=0.44 | F 0.03 | ||||

| Barthel scorea | 62 (31,78) | 69.5 (48,83) | 99.5 (92,100) | 96 (91,100) | 46 (29,73) | 44 (31,58) | M&F | |

| P valuec | P=0.12 | P=0.21 | P=0.52 | 0.0001 | ||||

| MMSEa | 24 (21,26) | 25 (20,27) | 28 (24,30) | 28 (25,30) | 15 (13,20) | 17 (12,24) | M&F | |

| P valuec | P=0.94 | P=0.54 | P=0.58 | 0.0001 | ||||

| MUST scoreb: | 0 | 21 (68) | 28 (47) | 20 (87) | 21 (91) | 29 (83) | 48 (74) | M 0.36; |

| 1 | 4(13) | 11(18) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 4 (11) | 6 (9) | F 0.001 | |

| 2-4 | 6(19) | 21(35) | 2 (9) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 11 (17) | ||

| P valuec | P=0.17 | P=1.000 | P=0.31 | |||||

| Falls in past yearb: | 0 | 8 (22) | 16 (25) | 8 (33) | 12 (52) | 20 (57) | 35 (54) | M 0.005; |

| 1 | 11 (31) | 19 (30) | 4 (17) | 4 (17) | 10 (29) | 15 (23) | F 0.01 | |

| 2 or more | 17 (47) | 28 (44) | 12 (50) | 7 (30) | 5 (14) | 15 (23) | ||

| P valuec | P=0.96 | P=0.40 | P=0.59 | |||||

Median (inter-quartile range,IQR);

Number (percentage,%); SD: standard deviation; N: number; cm: centimetres; kg: kilograms; BMI: body mass index; m: metre;

MMSE: mini mental state examination; MUST: Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool.

P value for differences between genders within settings calculated using 2-sample t-test, Mann Whitney rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test.

P valuefor differences between settings by gender calculated using ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test and Fisher’ss exact test.

Weight and BMI missing for 3 male and 1 female inpatients, and 1 male community referral, MMSE missing for 1 male community referral, MUST missing for 6 male and 4 female inpatients, and 1 male community referral, falls missing for 1 male and 1 female inpatient.

There was no significant difference in ‘MUST’ scores between men and women within each setting, but there was a difference between the settings for women (p=0.001) with the poorest nutritional scores among the female inpatients. Men and women within each setting experienced similar numbers of falls, but again there was a significant difference between settings with nursing home residents experiencing the fewest falls.

Maximum grip strength values for men and women by setting

Men had significantly higher mean maximum grip strength than women within each setting (p<0.0001), but there was a wide variation in grip strength within each setting as demonstrated by the percentiles (Table 2). In general higher grip strength was associated in univariate analyses with younger age, increased height and weight, fewer co-morbidities, higher Barthel score, higher MMSE score, lower ‘MUST’ score and fewer falls. After mutual adjustment for all of these factors in a multivariate analysis, Barthel score was most strongly associated with grip strength and was the only factor significantly associated with grip strength in each setting for both men and women.

Table 2. Maximum Grip Strength by Setting.

| Grip strength (kg) | Hospital Rehabilitation Inpatients |

Community Rehabilitation Referrals |

Nursing Home Residents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (N=37) |

Female (N=64) |

Male (N=24) |

Female (N=23) |

Male (N=35) |

Female (N=65) |

||

| P value1 | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 21.7 (7.7) | 13.6 (5.0) | 31.1 (6.4) | 19.6 (6.9) | 14.2 (7.8) | 6.6 (3.5) |

M:<0.0001

F: <0.0001 |

| P value2 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | ||||

| Percentiles | |||||||

| 1st | 6 | 2 | 19 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5th | 7 | 6 | 19 | 9 | 3 | 2 | |

| 10th | 12 | 8 | 22 | 12 | 4 | 3 | |

| 20th | 14 | 10 | 25 | 14 | 5 | 3 | |

| 25th | 17 | 11 | 26.5 | 15 | 8 | 4 | |

| 50th(median) | 22 | 14 | 32 | 20 | 14 | 6 | |

| 75th | 27 | 16 | 35.5 | 24 | 20 | 9 | |

| 90th | 31 | 19 | 39 | 28 | 26 | 12 | |

| 95th | 37 | 21 | 39 | 30 | 30 | 13 | |

| 99th | 39 | 31 | 43 | 36 | 32 | 14 | |

| Mean (SD)a | 21.7.(7.5) | 13.5 (4.8) | 29.3 (6.6) | 17.8 (7.2) | 15.5 (8.3) | 7.3 (4.2) |

P value3

M:<0.0001 F: <0.0001 |

kg: kilograms; N: number; SD: standard deviation;

pvalue for differences between settings by gender calculated using ANOVA

P value for differences between gender within settings calculated using 2-sample t-test

P value for differences between settings adjusted for age calculated using ANOVA

Mean grip strength adjusted for age

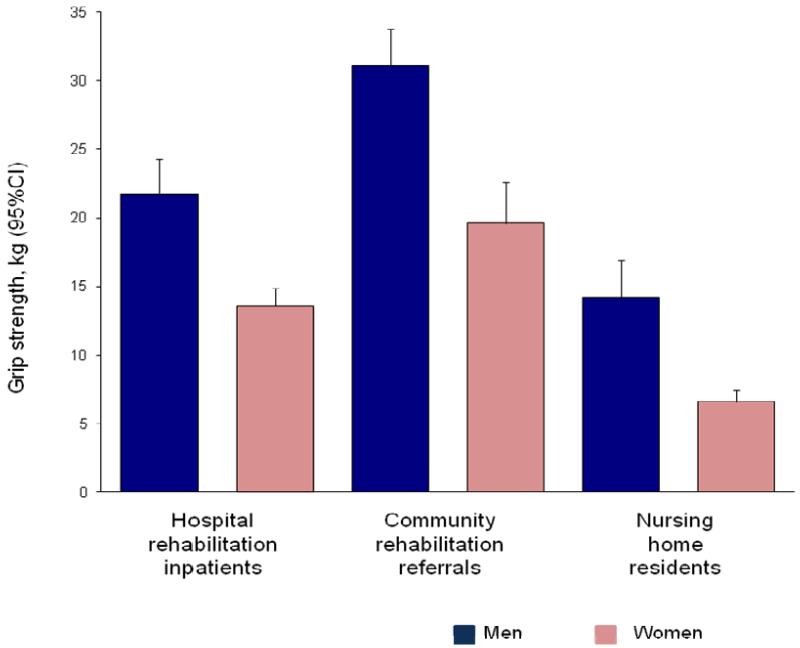

For both men and women there was a substantial difference in mean maximum grip strength between settings (p<0.0001) as shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Even after adjustment for age, nursing home residents had the lowest mean age-adjusted maximum grip strength (men 18.9 kg [SD 9.5]; women 8.4 kg [SD 5.0]) and community referrals the highest (men 30.6 kg [SD 7.4]; women 17.7 kg [SD 7.6]). The difference in grip strength values between the healthcare settings were so substantial that they remained significant (p<0.0001 for both men and women) after univariate adjustment in turn for the following factors: age, height, weight, BMI, number of co-morbidities and medications, Barthel Score, MMSE, ‘MUST’ score, and falls category. The difference in grip strength values between settings remained significant after mutual adjustment for all these factors (p=0.008 men; p<0.001 women).

Figure 1. Maximum grip strength (mean, SD) for each setting by gender.

DISCUSSION

The participants differed significantly between the three healthcare settings in many respects, notably age, height, weight, BMI, number of medications, Barthel score, MMSE, ‘MUST’ score and number of falls in the last year. Importantly, grip strength also differed significantly between the healthcare settings for both men and women with lower average values among nursing home residents and higher average values among community rehabilitation referrals. Grip strength was associated with Barthel score in particular, but the differences in grip strength between settings remained significant after adjustment for other co-variates. While the nursing home residents had the lowest MMSE scores they nevertheless appeared to understand at the time how to grip the dynamometer and to attempt to squeeze as hard as possible. In fact maximum grip strength was only significantly associated with MMSE among the female inpatients (please see Appendix Table 1 in the supplementary data ). The substantial differences in grip strength between the participants from the different healthcare settings included in this study were not surprising given the heterogeneity of the older people taking part. However there was also a wide variation in grip strength among people within each healthcare setting.

Three studies in North America have described grip strength in rehabilitation and care home settings and they also report low grip strength values. A retrospective study of 188 patients (mean age 58 years, range 18 – 87) under-going acute rehabilitation found that 76% had grip strength lower than age-adjusted reference values in both hands (23)(22) and overall the group’s mean grip strength was 37% lower in the left hand and 43% lower in the right hand. A similar retrospective notes review of 41 consecutive patients (mean age 74 years) receiving domiciliary rehabilitation for stroke disease, cancer, osteoarthritis and fractures reported a reduction in grip strength with mean values 25% lower than age-adjusted normative values for both left and right hands (24). In the third study Giuliani et al assessed 1,791 residents (mean age 84 years) of 189 residential care homes in North America. Mean (SD) grip strength for the 90% of participants who were able to complete the assessment was 14 (6.9) kg for both men and women, which was again lower than reported values for community dwelling older adults (25).

Grip strength of older people in different healthcare settings has been little studied in Europe. A Portuguese study which measured grip strength of 25 older people in residential care and 30 attending a social day care centre (mean age 79 years) reported a mean grip strength of 24.8 kg for men and 15.5 kg for women (26). A UK study comparing frailty assessment methods in older people who were either community dwelling, referred for outpatient rehabilitation, or resident in continuing care hospital wards did not report grip strength values (27). However it did describe the Fried Frailty Score (of which low grip is a component), the prevalence of which differed significantly across the three groups (p<0.05). There is growing evidence that measurement of grip strength is acceptable to older people in different healthcare settings (28) and may be simpler and more feasible for people with mobility issues than other physical performance measures such as gait speed.

This study had manystrengths including the recruitment of participants from three settings within one locality. In addition a high proportion of eligible subjects were recruited (74% inpatients and 90% nursing home residents). Thus this study adds valuable data on participants in UK healthcare settings.

A number of limitations also need to be considered. Firstly a lower recruitment rate was achieved among the community referrals despite recruiting over a period of 18 months, whereas it was achieved in the other settings in a shorter time scale. Secondly it was not possible to simultaneously recruit participants from an acute hospital setting. However a previous study by Kerr et al based in the local acute hospital recruited 120 men and women aged 75-101 years admitted to the Medical Admissions Unit between October 2004 and March 2005 (29). Data collection was similar and retrospective analysis of Kerr’s study shows that the participants’ characteristics were broadly comparable with those in this study. Mean grip strength among Kerr’s participants was 29.5 kg (men) and 16.8 kg (women), confirming the difference in grip strength between healthcare settings within one locality. Please see Appendix table 2 and Appendix table 3 in the supplementary data.

Current reference ranges typically derive from studies of community dwelling older adults who are often younger and fitter and have higher grip strength values than people presenting to healthcare settings similar to those in this study. Low grip (20th centile) among community dwelling populations is often defined as <30 kg for men and < 20 kg for women (30), and thus half of the community referrals and most of the inpatients and nursing home residents in this study would have been defined as having low grip, limiting discriminatory power. However future research could further define low grip strength within each setting. The ability to distinguish between people at increased risk of poor health within healthcare settings would allow appropriate interventions to be undertaken: for example there is evidence that low grip strength is associated with longer length of stay within an in-patient rehabilitation setting (18).

In conclusion this is the first study to describe the epidemiology of grip strength in a range of healthcare settings within one locality in the UK. Older people in rehabilitation and care home settings had lower grip strength than those living at home. Grip strength in these healthcare settings was influenced by the major determinants described in studies of community dwelling people, but the wide variation in grip strength was independent of these variables. Further research is required to ascertain whether grip strength can help identify people at risk of adverse health outcomes within each of these healthcare settings

Supplementary Material

Key points.

This is the first study to describe the epidemiology of grip strength of older people in different healthcare settings within one locality in the UK

Older people in rehabilitation and care home settings had lower grip strength than those living at home

The variation in grip strength between healthcare settings was independent of known major determinants of grip strength

Better grip strength was particularly associated with higher Barthel score, as a measure of physical function, in each setting

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants and the staff in each healthcare setting

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Southampton and BUPA Giving [grant 60].

Sponsor’s role

The sponsor had no role in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Patel HP, Shavlakadze T, Cooper C, Grounds MD. New horizons in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of sarcopenia. Age Ageing. 2013 Jan 11; doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Syddall H, Cooper C, Martin F, Briggs R, Aihie SA. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty? Age Ageing. 2003 Nov;32(6):650–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Choquette S, Bouchard DR, Doyon CY, Senechal M, Brochu M, Dionne IJ. Relative strength as a determinant of mobility in elders 67-84 years of age. a nuage study: nutrition as a determinant of successful aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010 Mar;14(3):190–5. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Dennison EM, Anderson FH, Cooper C. Falls, sarcopenia, and growth in early life: findings from the Hertfordshire cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Oct 1;164(7):665–71. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, Masaki K, Leveille S, Curb JD, et al. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. JAMA. 1999 Feb 10;281(6):558–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wennie Huang WN, Perera S, VanSwearingen J, Studenski S. Performance measures predict onset of activity of daily living difficulty in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 May;58(5):844–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Al SS, Markides KS, Ostir GV, Ray L, Goodwin JS. Predictors of recovery in activities of daily living among disabled older Mexican Americans. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003 Aug;15(4):315–20. doi: 10.1007/BF03324516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cooper R, Kuh D, Cooper C, Gale CR, Lawlor DA, Matthews F, et al. Objective measures of physical capability and subsequent health: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011 Jan;40(1):14–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cawthon PM, Fullman RL, Marshall L, Mackey DC, Fink HA, Cauley JA, et al. Physical performance and risk of hip fractures in older men. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 Jul;23(7):1037–44. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Silventoinen K, Magnusson PK, Tynelius P, Batty GD, Rasmussen F. Association of body size and muscle strength with incidence of coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular diseases: a population-based cohort study of one million Swedish men. Int J Epidemiol. 2009 Feb;38(1):110–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rantanen T, Masaki K, Foley D, Izmirlian G, White L, Guralnik JM. Grip strength changes over 27 yr in Japanese-American men. J Appl Physiol. 1998 Dec;85(6):2047–53. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Taekema DG, Gussekloo J, Maier AB, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ. Handgrip strength as a predictor of functional, psychological and social health. A prospective population-based study among the oldest old. Age Ageing. 2010 May;39(3):331–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R. Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010 Jul;39(4):412–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mathiowetz V. Comparison of Rolyan and Jamar dynamometers for measuring grip strength. Occup Ther Int. 2002;9(3):201–9. doi: 10.1002/oti.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, Patel HP, Syddall H, Cooper C, et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing. 2011 Jul;40(4):423–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bohannon RW, Bear-Lehman J, Desrosiers J, Massy-Westropp N, Mathiowetz V. Average grip strength: a meta-analysis of data obtained with a Jamar dynamometer from individuals 75 years or more of age. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2007;30(1):28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Roberts HC, Syddall HE, Cooper C, Aihie SA. Is grip strength associated with length of stay in hospitalised older patients admitted for rehabilitation? Findings from the Southampton grip strength study. Age Ageing. 2012 Sep;41(5):641–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Haboubi NY, Hudson PR, Pathy MS. Measurement of height in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990 Sep;38(9):1008–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb04424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).MAHONEY FI, BARTHEL DW. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J. 1965 Feb;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Stratton RJ, Hackston A, Longmore D, Dixon R, Price S, Stroud M, et al. Malnutrition in hospital outpatients and inpatients: prevalence, concurrent validity and ease of use of the ‘malnutrition universal screening tool’ (‘MUST’) for adults. Br J Nutr. 2004 Nov;92(5):799–808. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).McAniff CM, Bohannon RW. Validity of grip strength dynamometry in acute rehabilitation. J Phys Ther Sci. 2002;14(1):41–6. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bohannon RW. Grip strength impairments among older adults receiving physical therapy in a home-care setting. Percept Mot Skills. 2010;111(3):761–4. doi: 10.2466/03.10.15.PMS.111.6.761-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Giuliani CA, Gruber-Baldini AL, Park NS, Schrodt LA, Rokoske F, Sloane PD, et al. Physical performance characteristics of assisted living residents and risk for adverse health outcomes. Gerontologist. 2008 Apr;48(2):203–12. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Guerra RS, Amaral TF. Comparison of hand dynamometers in elderly people. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009 Dec;13(10):907–12. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hubbard RE, O’Mahony MS, Woodhouse KW. Characterising frailty in the clinical setting--a comparison of different approaches. Age Ageing. 2009 Jan;38(1):115–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Roberts HC, Sparkes J, Syddall H, Butchart J, Ritchie J, Cooper C, et al. Is measuring grip strength acceptable to older people?The Southampton Grip Strength Study. Journal of Aging Research and Clinical Practice. 2012;1(2):135–40. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kerr A, Syddall HE, Cooper C, Turner GF, Briggs RS, Sayer AA. Does admission grip strength predict length of stay in hospitalised older patients? Age Ageing. 2006 Jan;35:82–4. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Cavazzini C, Di IA, et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol. 2003 Nov;95(5):1851–60. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.