Abstract

Objective

To determine Mycoplasma genitalium infection and correlates among young women undergoing population-based screening or clinic-based testing for Chlamydia infection.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) and two London sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics.

Participants

2441 women aged 15–64 years who participated in the NCSP and 2172 women who attended two London STI clinics over a 4-month period in 2009.

Outcome measures

(1) M genitalium prevalence in defined populations (%). (2) Age-adjusted ORs (aORs) for correlates of M genitalium infection.

Results

The overall frequency of M genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis was 3% and 5.4%, respectively. Co-infection was relatively uncommon (0.5% of all women); however 9% of women with C trachomatis also had M genitalium infection. M genitalium was more frequently detected in swab than urine samples (3.9 vs 1.3%, p<0.001) with a significantly higher mean bacterial load (p ≤ 0.001). Among NCSP participants, M genitalium was significantly more likely to be diagnosed in women of black/black British ethnicity (aOR 2.3, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.5, p=0.01). M genitalium and C trachomatis and were both significantly associated with multiple sexual partners in the past year (aOR 2.4, 95% CI 1.3 to 4.4, p=0.01 and aOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4 to 2.8, p<0.01). Among STI clinic attendees, M genitalium was more common in women who were less than 25 years in age.

Conclusions

M genitalium is a relatively common infection among young women in London. It is significantly more likely to be detected in vulvovaginal swabs than in urine samples. Co-infection with Chlamydia is uncommon. The clinical effectiveness of testing and treatment strategies for M genitalium needs further investigation.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Genitourinary Medicine, Microbiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest UK based-cross-sectional study to date to provide estimates of Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence in both community and sexually transmitted infection clinic-based populations.

M genitalium PCR results were confirmed positive by genotype sequencing.

Our analysis of potential correlates for M genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis is limited by the availability of data.

Introduction

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and its sequelae (chronic pelvic pain, ectopic pregnancy and tubal infertility) are major causes of morbidity in women in developed and developing countries.1 In the USA more than $10 billion is spent annually in treating these conditions.2 Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, two sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are known causes of PID. However, in up to 70% of PID cases no cause is found3 and there is increasing evidence that Mycoplasma genitalium might be a cause of PID.4–8

There is also strong evidence that it is sexually transmitted.5 6 It is significantly associated with endometritis and9 tubal factor infertility10 although the association with cervicitis is complex.11 12 As with C trachomatis it can be asymptomatic, acting as a reservoir for further spread.13 It may also be associated with HIV acquisition.14

Although at present M genitalium is not routinely tested for in most countries, there is interest in introducing testing and treatment. However, before this is done there is a need to gain a better understanding of the infection to avoid repeating the problems encountered with C trachomatis screening.15 In the UK there are few data on the frequency of M genitalium infection in different population groups of women. Oakeshott et al16 found that M genitalium prevalence was 3.3% among young women in a community based sample who took part in a C trachomatis screening trial in the UK. Estimates from studies in other countries indicate that levels of M genitalium are 40–60% lower than C trachomatis, with little co-infection.17 18 The recommended treatment for uncomplicated Chlamydia infection is a single dose of azithromycin 1 g stat. There is growing evidence of considerably lower M genitalium cure rates with this dose of azithromycin compared with C trachomatis (79–87% vs 92–97%, respectively).19–21 Resistance has been shown to develop following 1 g of azithromycin and macrolide resistance is endemic in some populations.22–24

We investigated M genitalium infection by real-time PCR and determined its correlates in the largest cross-sectional study of M genitalium among women screened for C trachomatis in the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) and STI clinics in the UK.

Methods

Patients and specimens

We used an unlinked anonymised method to test routinely collected and stored cervical swabs, self-taken vaginal swabs and first catch urine samples for M genitalium. The samples were from 2180 women aged 15–64 years who had C trachomatis screening when they attended two STI clinics in central and North London and 2455 women aged 15–24 years who participated in the NCSP in London in a 4-month period in 2009. Each clinic offers comprehensive STI screening, treatment and partner notification services to symptomatic and asymptomatic women and men, irrespective of age. Samples from all female clinic attendees were eligible for the study. The NCSP is a national screening programme for Chlamydia in the UK among women and men who are under 25 years in age. The NCSP samples were from a variety of low and high STI risk settings within two London boroughs. In 2009 the majority of participating sites from which the samples were tested were family planning clinics (47%), universities (17%) and general practices (16%). Other testing sites included pharmacies, abortion services, outreach, young persons' services, schools and postal testing (Tina Sharp, NCSP Chlamydia Coordinator, personal communication).

The samples were originally collected from the NCSP and clinics and transported to the Microbiology Laboratory at University College London Hospital in 3 mL (self-taken vaginal and cervical swabs) or 4 mL (urine samples diluted 1 : 1) of APTIMA transport medium (Gen-Probe Inc, San Diego, USA) for routine C trachomatis testing. After C trachomatis testing the negative samples were stored for 6 weeks at −20°C and positive samples were stored for 3 months at −20°C before they were released for testing as part of this study. Available demographic, sexual behaviour, clinical PID diagnosis and STIs data were recorded before samples were unlinked from all personal identifiers prior to M genitalium testing.

M genitalium testing

Samples were thawed and DNA from 200 µL of the APTIMA transport medium was purified by BioRobot 9604 automated workstation using the QIAamp Virus BioRobot 9604 Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Before freezing and storing the eluate at −20°C it was tested by quantitative PCR (qPCR) adapted from a method by Jensen et al.17 25 The qPCR targeted the MgPa adhesion gene (MG191) using MgPa-355FW and MgPa-432R primers and MgPa-380 MGB probe (primers and probes were provided by Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). Pilot laboratory work showed no difference in APTIMA Urine Specimen Transport Tubes and APTIMA Vaginal Swab Specimen Collection Kit transport medium and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) spiked with M genitalium DNA in different concentrations.

We introduced a degenerate oligonucleotide (‘wobble’) in the forward primer to account for a frequent detected base substitution that has previously been shown to be successful in another study by Chalker et al.26 As an internal control for PCR inhibition we used murine cytomegalovirus (mCMV) and primers mCMVTAQ1 (forward primer) and mCMVTAQ2 (reverse primer) and mCMVTAQPR probe labelled with JOE (Primers and probe were provided by Eurofins MWG Operon) designed by Garson et al.27 The qPCR assays were performed in 25 µL volumes; comprising 1× EXPRESS qPCR Supermix (Universal, Invitrogen, Life technologies Ltd Paisley, UK), 0.4 µM forward and reverse primers, 0.2 µM probes and 7.5 µL of samples and nuclease-free water (Promega UK Ltd, Southampton, UK).

Thermal cycling was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-time PCR instrument using the following conditions: hotstart at 95°C for 2 min and 1 cycle, denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing and extension at 60°C for 1 min and 45 cycles. The data was analysed using Sequence Detection Software (SDS) V.1.4 with manual baseline/threshold settings to estimate quantification cycle.

Positive samples were re-extracted and retested by qPCR. If these tested negative the samples were re-extracted and tested by qPCR a third time. If negative again the sample was considered equivocal and was excluded from the analysis.

M genitalium genotyping

M genitalium PCR-positive samples were sequenced by MgPa1–3 typing assay according to Hjort et al.28 The assay was modified with respect to PCR reagents and PCR conditions. In a total volume of 50 µL the following were mixed: 25 µL of Taq PCR Master Mix kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), 0.4 µM of mgpa-1 and mgpa-3 primers, 5 µL of template and nuclease-free water. To increase the sensitivity of the assay 10 µL of the template was used in cases where the bacterial load was less than 1 genome copy/µL.

The PCR was performed on an ABI9700 instrument and in three-step cycling conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min and 50 cycles.

The amplified product were purified manually by QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and sent to the UCL sequencing service for sequencing of both the forward and reverse strand.

Statistical analysis

We have only included data from women who are at least 15 years old in the analysis. Data were analysed using SPSS V.14.0 for Windows. Paired sample t test was used to compare the difference of mean values. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the relationship between M genitalium or C trachomatis infection and demographic and sexual behaviour characteristics in women attending NCSP or STI clinics.

Categorical variables in the NCSP model included participant age, specimen type, a new sexual partner within 3 months, more than one partner within 12 months and ethnicity. The categorical variables included in the STI model were participant age, specimen type, current STI infections and ethnicity. Frequency, ORs adjusted for age (aOR) and 95% CIs were calculated and values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

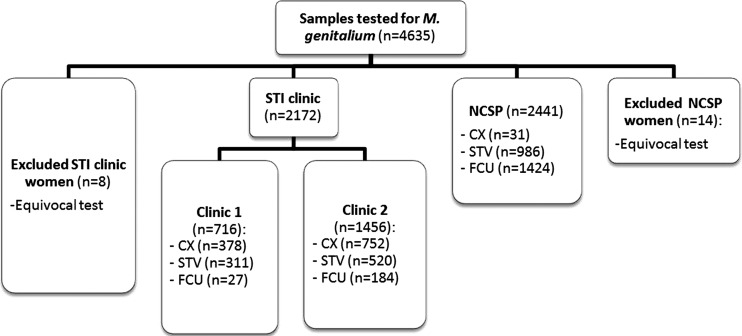

Of 4635 samples, we excluded 21 samples for which the M genitalium test result was equivocal and included 4613 samples in our analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Of 4635 samples, 21 samples were excluded for which the M genitalium test result was equivocal and 4613 samples were included in the analysis.

NCSP participants were aged 15–24 years whereas STI clinic attendees were aged 15–64 years. Women attending the two clinics had significantly different mean ages (20.1 years, SD 2.5 vs 27.8 years, SD 7.6 years, p<0.0001). The highest prevalence of M genitalium and C trachomatis was in age groups 15–24 years in NCSP and the STI clinics. As we only had ethnicity data for 39% (851/2172) of the STI clinic attendees, we did not compare ethnicity across the clinics.

M genitalium and C trachomatis infection

As shown in table 1, the overall frequency of M genitalium and C trachomatis was 3% (138/4613, 95% CI 2.5% to 3.5%) and 5.4% (249/4613, 95% CI 4.8% to 6.1%), respectively. The overall co-infection rate was 0.5% (23/4613, 95% CI 0.3% to 0.7%). Of 249 women with C trachomatis, 23 (9%) women had M genitalium infection.

Table 1.

Mycoplasma genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis infection among NCSP and STI clinic attendees

| Infection | Clinic 2 N=716 | Clinic 1 N=1456 | NCSP N=2441 | Total N=4613 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%, 95% CI) | N (%, 95% CI) | N (%, 95% CI) | N (%, 95% CI) | |

| M genitalium and C trachomatis | 3 (0.4, 0 to 0.9) | 4 (0.3, 0 to 0.6) | 16 (0.7, 0.4 to 1.0) | 23 (0.5, 0.3 to 0.7) |

| Total M genitalium | 38 (5.3, 3.7 to 7.0) | 43 (3.0, 2.0 to 3.9) | 57 (2.3, 1.7 to 2.9) | 138 (3.0, 2.5 to 3.5) |

| M genitalium only | 35 (4.9, 3.3 to 6.5) | 41 (2.8, 2.0 to 3.7) | 39 (1.6, 1.1 to 2.1) | 115 (2.5, 2.0 to 2.9) |

| Total C trachomatis | 23 (3.2, 1.9 to 4.5) | 60 (4.1, 3.1 to 5.1) | 166 (6.8, 5.8 to 7.8) | 249 (5.4, 4.8 to 6.1) |

| C trachomatis only | 20 (2.8, 1.6 to 4.0) | 56 (3.8, 2.9 to 4.8) | 150 (6.1, 5.2 to 7.1) | 226 (4.9, 4.3 to 5.5) |

NCSP, National Chlamydia Screening Programme; M genitalium, Mycoplasma genitalium; C trachomatis, Chlamydia trachomatis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Among NCSP participants, M genitalium and C trachomatis frequency were 2.3% (57/2441, 95% CI 1.7% to 2.9%) and 6.8% (166/2441, 95% CI 5.8% to 7.8%), respectively.

M genitalium infection significantly differed between the two clinics (5.3%, 95% CI 3.7% to 7.0% and 3.0%, 95% CI 2.1% to 3.8%, p<0.01) but the difference was not significant after adjusting for age (p=0.16). C trachomatis did not differ significantly between the two clinics (3.2%, 95% CI 1.9% to 4.5% and 4.1%, 95% CI 3.1% to 5.1%, p=0.30).

Association of M genitalium and C trachomatis with sexual behaviour and demographic characteristics of participants in the NCSP

Table 2 shows the association of M genitalium and C trachomatis with sexual behaviour and demographic characteristics among NCSP participants. M genitalium was less frequently detected than C trachomatis in both age groups (15–19 years old 2.8%, 29/1045 vs 8.3%, 83/1045 and 20–24 years old 2.0%, 28/1396 vs 5.7%, 79/1396, respectively). When adjusted for age M genitalium was significantly more common in black/black British women compared with white women (aOR 2.3, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.5, p=0.01). Women who reported multiple sexual partners in the past 12 months were twice as likely to have both M genitalium and C trachomatis infections compared with women who reported only one partner (aOR 2.4, 95% CI 1.3 to 4.4, p=0.01) and (aOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4 to 2.8, p<0.01), respectively. Women who reported new sexual partners in the previous 3 months were also more likely to have C trachomatis infection (aOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.3, p=0.01). Those who did not self-identify as white, black/black British, Asian/Asian British or mixed ethnicity were less likely to be infected with C trachomatis compared with white women (aOR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9, p=0.01).

Table 2.

Association of characteristics with Mycoplasma genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis in NCSP attendees

| Characteristic | (N=2441) Per centage of women with characteristic | M genitalium (%) (proportion of women) | aOR* (95% CI) | p Value | C trachomatis (%) (proportion of women) | aOR* (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| 15–19 | 41.6 | 2.8 (29/1045) | 8.3 (87/1045) | ||||

| 20–24 | 56.5 | 2.0 (28/1396) | 5.7 (79/1396) | ||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 46.6 | 2.0 (23/1138) | 1 | 7.4 (84/1138) | 1 | ||

| Black or black British | 12.8 | 4.8 (15/314) | 2.3 (1.2 to 4.5) | 0.01 | 8.3 (26/314) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) | 0.83 |

| Asian or Asian British | 4.4 | 1.9 (2/108) | 0.9 (0.2 to 4.0) | 0.93 | 6.2 (5/108) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.6) | 0.33 |

| Mixed | 7.7 | 3.7 (7/187) | 1.8 (0.8 to 4.3) | 0.18 | 10.2 (19/187) | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.3) | 0.29 |

| Other ethnic groups | 28.4 | 1.4 (10/694) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.5) | 0.35 | 4.6 (32/694) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.01 |

| New sexual partner in previous 3 months | |||||||

| Yes | 31.5 | 3.2 (25/770) | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.6) | 0.20 | 9.2 (71/770) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) | 0.01 |

| No | 39.3 | 2.2 (21/959) | 1 | 5.8 (56/959) | 1 | ||

| Do not want to answer | 0.2 | 0.0 (0/6) | – | – | 0.0 (0/6) | – | – |

| Not filled in | 28.9 | 1.6 (11/706) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.4) | 0.33 | 5.5 (39/706) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) | 0.69 |

| Sex with >1 partner within 12 months | |||||||

| Yes | 30.8 | 3.9 (29/751) | 2.4 (1.3 to 4.4) | 0.01 | 10.0 (75/751) | 2.0 (1.4 to 2.8) | <0.01 |

| No | 39.5 | 1.7 (16/963) | 1 | 5.4 (52/963) | 1 | ||

| Do not want to answer | 0.3 | 0.0 (0/8) | – | – | 0.0 (0/8) | – | – |

| Not filled in | 29.5 | 1.7 (12/719) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.1) | 0.99 | 5.4 (39/719) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.5) | 0.99 |

| Specimen | |||||||

| Cervical/ | 1.3 | 3.2 (1/31) | 3.3 (0.4 to 25.8) | 0.26 | 9.7 (3/31) | 2.0 (0.6 to 7.4) | 0.21 |

| Self-taken vaginal | 40.4 | 4.2 (41/986) | 4.2 (2.3 to 7.6) | <0.001 | 9.3 (92/986) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.8) | <0.001 |

| First catch urine | 58.3 | 1.0 (15/1424) | 1 | 5.0 (71/1424) | 1 | ||

*aOR, ORs adjusted for age only.

Association of M genitalium and C trachomatis with sexual behaviour and demographic characteristics of STI clinic attendees

Table 3 shows the association of M genitalium and C trachomatis with sexual behaviour and demographic characteristics among STI clinic attendees. The age distribution for both M genitalium and C trachomatis was similar with infections more frequently detected in younger women (15–19 years 9.7%, 18/186 vs 6.4%, 12/186, respectively and 20–24 years 6.2%, 41/665 vs 6.0%, 40/665) than other age groups. M genitalium was more frequently detected in 15–19 year-old women than C trachomatis although this was not statistically significant (p=0.28).

Table 3.

Association of characteristics with Mycoplasma genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis in women attending two London STI clinics

| Characteristic | (N=2172) Percentage of women with characteristic | M genitalium (%) (proportion of women) | aOR* (95% CI) | p Value | C trachomatis proportion of women) | aOR* (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| 15–19 | 8.6 | 9.7 (18/186) | 6.4 (12/186) | ||||

| 20–24 | 30.6 | 6.2 (41/665) | 6.0 (40/665) | ||||

| 25–29 | 28.6 | 1.6 (10/621) | 2.9 (18/621) | ||||

| 30–34 | 15.6 | 2.3 (9/339) | 3.2 (11/339) | ||||

| 35–64 | 16.6 | 0.8 (3/361) | 0.6 (2/361) | ||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 23.0 | 6.0 (30/499) | 1 | 7.0 (35/499) | 1 | ||

| Black or black British | 6.9 | 7.4 (11/149) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.5) | 0.60 | 4.0 (6/149) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.3) | 0.54 |

| Asian or Asian British | 1.7 | 17.6 (6/36) | 3.1 (1.2 to 8.1) | 0.19 | 5.6 (2/36) | 0.8 (0.2 to 3.4) | 0.73 |

| Mixed | 3.9 | 4.8 (4/84) | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.1) | 0.54 | 7.1 (6/84) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.3) | 0.91 |

| Other Ethnic groups | 3.9 | 9.5 (8/83) | 1.6 (0.7 to 3.7) | 0.24 | 3.6 (3/83) | 0.5 (0.1 to 1.6) | 0.49 |

| Unknown | 60.8 | 1.7 (22/1321) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) | 0.09 | 2.3 (31/1321) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.4) | 0.66 |

| Specimen | |||||||

| Cervical/ | 90.3 | 3.8 (75/1961) | 1.4 (0.6 to 3.2) | 0.48 | 3.4 (38/1130) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.6) | 0.44 |

| Self-taken vaginal | 4.3 (36/831) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) | 0.83 | ||||

| First catch urine | 9.7 | 2.8 (6/211) | 1 | 4.3 (9/211) | 1 | ||

*aOR, ORs adjusted for age only.

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Specimen type and bacterial load

Overall M genitalium was detected in 3.7% (43/1161), 4.0% (74/1817) and 1.3% (21/1635) of cervical swabs, self-taken vulval swabs and first-void urine samples, respectively. Since M genitalium frequency in cervical and self-taken swabs was similar (p=0.86), the results for the two groups of swabs were merged and tested against first-void urine samples in the statistical model. M genitalium was significantly more likely to be detected in swabs compared with urine specimens (3.9 vs 1.3%, p<0.001).

The overall frequency of C trachomatis in cervical swabs, self-taken vulval swabs and first-void urine samples was 3.5% (41/1161), 7.0% (128/1817) and 4.9% (80/1635), respectively. C trachomatis significantly differed between cervical and self-taken swabs (p<0.001) and the two groups were separately tested against the urine samples in the statistical model.

The majority (58%, 1424/2441) of specimens provided by the women in NCSP were urine samples. However, swab samples were almost four times more likely to test positive for M genitalium compared with urine samples (aOR 3.6, 95% CI 1.9 to 6.7, p<0.001) and C trachomatis infection was almost twice as high among swabs compared with urine samples (aOR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.4 p=0.001). Conversely the majority (90.3%, 1961/2172) of clinic specimens were swabs. M genitalium and C trachomatis in the clinic swab and urine specimens also differed (M genitalium 3.8%, 75/1961 vs 2.8%, 6/211 and C trachomatis 3.8%, 74/1961 vs 4.3%, 9/211, respectively).

In quantitative analysis of M genitalium positive specimens, mean M genitalium bacterial load in swab and urine samples did not significantly differ between the clinics or NCSP. Clinical data were therefore combined for comparison of the mean bacterial load in different specimen types. There was no difference in overall cervical and self-taken vaginal swab bacterial loads (3.72 (CI 3.39 to 4.05) vs 3.91 (CI 3.66 to 4.17) log10 genome copies/mL, equivalent to geometric means of 5218 (CI 2438 to 11 171) and 8192 (CI 4575 to 14 669) organisms/mL, respectively; p=0.349). The overall mean bacterial load in swabs 3.84 (CI 3.52 to 4.11) equivalent to 6705 (CI 3506 to 12 920) organisms/mL was significantly higher than in first-void urine samples (3.14 (CI 2.87 to 3.41) equivalent to 1386 (CI 740 to 2597) organisms/mL) (p<0.0001, equal variances not assumed).

Genetic diversity

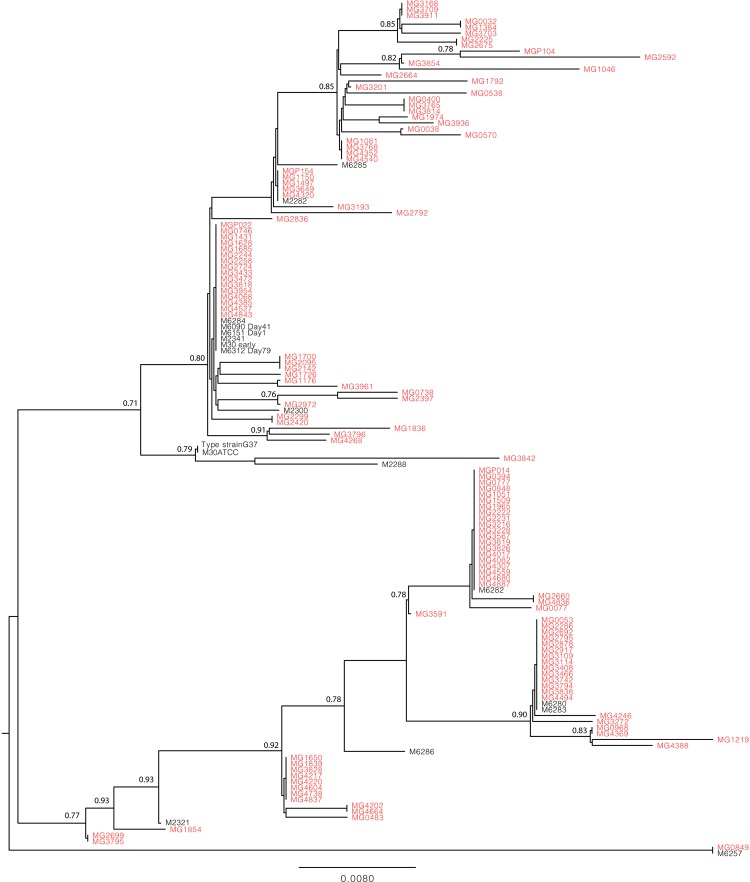

The absence of false-positive results was confirmed by the presence of 57 different genotypes by sequence analysis of 127 M genitalium-positive specimens and 13 sequences from previously isolated strains (figure 2). The discriminatory index by Hunter and Gaston29 was calculated to be 0.94 both with and without inclusion of the previously isolated strain sequences. None of the sequenced samples were identical with the type strain G37 used as a PCR standard control. Genetic diversity data are available in FASTA format for download in the online supplementary material.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing clustering of 127 DNA sequences from the Mycoplasma genitalium-positive specimens of the study (marked with grey font) and 13 DNA sequences from M genitalium strain from patients with no known sexual relationship (marked with black font).

Discussion

Overall M genitalium was relatively common at 3% among NCSP participants and STI clinical attendees. M genitalium was more likely to be found in swabs compared with urine samples (3.9% vs 1.3%, respectively) and the mean bacterial load was also much higher (6705 (CI 3506 to 12 920) organisms/mL vs 1386 (CI 740 to 2597) organisms/mL, respectively).

Only 0.5% of all the women had both C trachomatis and M genitalium infections. Among women who had C trachomatis, 9% were coinfected with M genitalium compared with <5% in population-based studies.16 18 30 31 Among NCSP participants the age-adjusted odds of detecting M genitalium were twice as high among women of black/black British ethnicity (aOR 2.3) and those reporting multiple sexual partners in the past year (aOR 2.4) compared with women of white ethnicity or those who reported only one partner, respectively. After adjusting for age, C trachomatis was also significantly more likely to be diagnosed in women with multiple partners (aOR 2.0) and new sexual partners in the previous 3 months (aOR 1.6) but was less likely to be detected in women who did not give a self-identified ethnic group (aOR 0.6) compared with reporting only one partner, not reporting new partners or being of white ethnicity, respectively. No significant associations were observed for either infection among STI clinical attendees.

This is the largest UK-based M genitalium study to date to provide estimates of infection among both community and STI clinic-based populations. Transport media may affect the sensitivity of DNA-based PCR tests. The study samples were originally collected in APTIMA medium. We, therefore, tested APTIMA and PBS media with M genitalium DNA and did not find any differences. We confirmed positive M genitalium PCR results by genotype sequencing. Our analysis of M genitalium and C trachomatis correlates is limited by availability of data: only age and ethnicity were available for both clinical and NCSP datasets and ethnicity data was missing for 61% of STI clinical attendees. There is also a possibility that some young women may have had Chlamydia tests through both the NCSP and the STI clinics during the sample collection period. It is not possible to quantify this although we speculate that the numbers are likely to be low given the relatively short time frame.

Our STI clinical M genitalium frequency is similar to that found in several studies of female STI clinical attendees (4.5–7%)32 33 although other studies have reported much higher frequencies (19.3–38.2%).12 34 In lower risk non-STI clinical attendees such as college students infection has been shown to range from <1% to 5%5 35 which is in keeping with our estimate in the Chlamydia screening population. The higher frequency of M genitalium in women attending clinics than the NCSP (3–5.3% vs 2.3%, respectively) may in part reflect the higher proportion of swabs taken in clinics than in NCSP settings. Urine samples have been shown to be less sensitive for M genitalium diagnosis than swabs (61–65% compared with 74–91%).36 37 It is therefore likely that our NCSP M genitalium frequency is an underestimation. Although urine sample sensitivity may be increased by up-concentrating the samples by centrifugation this is not a practical step for large scale testing. A higher bacterial load may be associated with symptoms as has been shown for men.25 This may also explain the difference in infection between the two populations since STI clinical attendees are more likely to be symptomatic than NCSP participants. The association of M genitalium with multiple sexual partners and black ethnicity has been previously observed.16 31 Additional risk factors include younger age as observed in our STI clinical attendees, bacterial vaginosis, being symptomatic, cervicitis, douching, smoking, prior miscarriage, menstrual cycle, social class and marital status.12 16 31 38–40

M genitalium appears to be a relatively common infection among women in London. The low level of M genitalium and C trachomatis co-infection (0.5%) suggests that diagnosing and treating Chlamydia will have little impact on M genitalium. However, azithromycin 1 g used to treat uncomplicated C trachomatis infection appears to be suboptimal for M genitalium treatment.24 This treatment dose has also been associated with the development of M genitalium macrolide resistance in some studies of predominantly symptomatic men.22 24 The risk of inadvertent M genitalium antibiotic resistance in coinfected women who are treated for Chlamydia with 1 g of azithromycin is therefore potentially a cause for concern although further research is required to confirm this.

To avoid the problems encountered with C trachomatis screening and M genitalium antimicrobial resistance, prior to introducing routine testing for M genitalium, further research is needed to better understand its natural history, the role of asymptomatic and symptomatic M genitalium in PID and determine optimum treatment guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Menelaos Pavlou (Centre for Sexual Health and HIV Research, Mortimer Market Centre, London, UK) and Tina Sharp (Mortimer Market Centre, London, UK, previously NCSP Chlamydia Coordinator, Camden Primary Care Trust) for extracting clinical data from the Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinics and the National Chlamydia Screening Programme, respectively. The authors also thank Dr Stephane Hue, Center for Virology, UCL for aligning the sequenced fragments and create the resulting phylogenetic tree.

Footnotes

Contributors: HFS, SSD, CC, PG, SM-J, MK and JMS contributed to conception and design of the study and/or to acquisition of data. HFS performed the experiments. HFS, SSD and JS drafted the paper and all authors contributed to critical revision of the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by UCLH/UCL Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre grant no. 59.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: None.

Ethics approval: On the advice of the chair of the local ethics committee, ethical approval was not required since the study team received anonymised samples for testing in the study from the laboratory and no other identifiable data were available.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Barrett S, Taylor C. A review on pelvic inflammatory disease. Int J STD AIDS 2005;16:715–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simms I, Stephenson JM. Pelvic inflammatory disease epidemiology: what do we know and what do we need to know? Sex Transm Infect 2000;76:80–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haggerty CL, Ness RB. Diagnosis and treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2008;4:383–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haggerty CL, Taylor BD. Mycoplasma genitalium: an emerging cause of pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:959816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGowin CL, Anderson-Smits C. Mycoplasma genitalium: an emerging cause of sexually transmitted disease in women. PLoS Pathog 2011;7:e1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from Chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:498–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjartling C. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and pelvic inflammatory disease after termination of pregnancy. BJOG 2010;117:361–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjartling C. Mycoplasma genitalium in cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease among women at a gynecologic outpatient service. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen CR, Manhart LE, Bukusi EA, et al. Association between Mycoplasma genitalium and acute endometritis. Lancet 2002;359:765–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svenstrup HF, Fedder J, Kristoffersen SE, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis, and tubal factor infertility—a prospective study. Fertil Steril 2008;90:513–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manhart LE, Broad JM, Golden MR. Mycoplasma genitalium: should we treat and how? Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(s3):s129–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mobley VL, Hobbs MM, Lau Ket al. Mycoplasma genitalium infection in women attending a sexually transmitted infection clinic: diagnostic specimen type, coinfections, and predictors. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:706–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium—the etiological agent of urethritis and other sexually transmitted diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2004;18:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mavedzenge SN, Van Der PB, Weiss HA, et al. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and HIV-1 acquisition in African women. AIDS 2012;26:617–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low N, Bender N, Nartey L, et al. Effectiveness of chlamydia screening: systematic review. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:435–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oakeshott P, Aghaizu A, Hay P, et al. Is Mycoplasma genitalium in women the “New Chlamydia?” A community-based prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:1160–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anagrius C, Lore B, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence, clinical significance, and transmission. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:458–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen B, Sokolowski I, Ostergaard L, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence and behavioural risk factors in the general population. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:237–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen JS, Bradshaw CS, Tabrizi SN, et al. Azithromycin treatment failure in Mycoplasma genitalium-positive patients with nongonococcal urethritis is associated with induced macrolide resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:1546–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau CY, Qureshi AK. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for genital chlamydial infections: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:497.– [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horner PJ. Azithromycin antimicrobial resistance and genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection: duration of therapy may be the key to improving efficacy. Sex Transm Infect 2012;88:154.– [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anagrius C, Lore B, Jensen JS. Treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium. Observations from a Swedish STD clinic. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e61481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tagg KA, Jeoffreys NJ, Couldwell DL, et al. Fluoroquinolone and macrolide resistance-associated mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:2245–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Twin J. Transmission and selection of macrolide resistant Mycoplasma genitalium infections detected by rapid high resolution melt analysis. PLoS One 2012;7(4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen JS, Bjornelius E, Dohn B, et al. Use of TaqMan 5′ nuclease real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Mycoplasma genitalium DNA in males with and without urethritis who were attendees at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:683–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalker VJ, Jordan K, Ali T, et al. Real-time PCR detection of the mg219 gene of unknown function of Mycoplasma genitalium in men with and without non-gonococcal urethritis and their female partners in England. J Med Microbiol 2009;58(Pt 7):895–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garson JA, Grant PR, Ayliffe U, et al. Real-time PCR quantitation of hepatitis B virus DNA using automated sample preparation and murine cytomegalovirus internal control. J Virol Methods 2005;126:207–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hjorth SV, Bjornelius E, Lidbrink P, et al. Sequence-based typing of Mycoplasma genitalium reveals sexual transmission. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:2078–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol 1988;26:2465–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manhart LE, Holmes KK, Hughes JP, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium among young adults in the United States: an emerging sexually transmitted infection. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1118–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker J, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS, et al. The difference in determinants of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium in a sample of young Australian women. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manhart LE, Critchlow CW, Holmes KK, et al. Mucopurulent cervicitis and Mycoplasma genitalium. J Infect Dis 2003;187:650–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moi H, Reinton N, Moghaddam A. Mycoplasma genitalium in women with lower genital tract inflammation. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casin I, Vexiau-Robert D, De La SP, et al. High prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in the lower genitourinary tract of women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic in Paris, France. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:353–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen AJ, Kleveland CR, Moghaddam A, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum among students in northern Norway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:e91–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lillis RA, Nsuami MJ, Myers L, et al. Utility of urine, vaginal, cervical, and rectal specimens for detection of Mycoplasma genitalium in women. J Clin Microbiol 2011;49:1990–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wroblewski JK, Manhart LE, Dickey KA, et al. Comparison of transcription-mediated amplification and PCR assay results for various genital specimen types for detection of Mycoplasma genitalium. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:3306–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Short VL, Totten PA, Ness RB, et al. The demographic, sexual health and behavioural correlates of Mycoplasma genitalium infection among women with clinically suspected pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:29–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oakeshott P, Hay P, Taylor-Robinson D, et al. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in early pregnancy and relationship between its presence and pregnancy outcome. BJOG 2004;111:1464–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandepitte J, Muller E, Bukenya J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Mycoplasma genitalium infection among female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. J Infect Dis 2012;205:289–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.