Background: The TNF family ligand EDA1 is required for development of hair, teeth, and many glands.

Results: Mouse fetuses exposed to anti-EDA antibodies develop a permanent ectodermal dysplasia.

Conclusion: Monoclonal anti-EDA antibodies block EDA at stoichiometric ratio in vitro and in vivo.

Significance: Down-modulation of EDA has useful research and potentially therapeutic applications.

Keywords: Antibodies, Embryo, Receptors, Tooth, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)

Abstract

Development of ectodermal appendages, such as hair, teeth, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and mammary glands, requires the action of the TNF family ligand ectodysplasin A (EDA). Mutations of the X-linked EDA gene cause reduction or absence of many ectodermal appendages and have been identified as a cause of ectodermal dysplasia in humans, mice, dogs, and cattle. We have generated blocking antibodies, raised in Eda-deficient mice, against the conserved, receptor-binding domain of EDA. These antibodies recognize epitopes overlapping the receptor-binding site and prevent EDA from binding and activating EDAR at close to stoichiometric ratios in in vitro binding and activity assays. The antibodies block EDA1 and EDA2 of both mammalian and avian origin and, in vivo, suppress the ability of recombinant Fc-EDA1 to rescue ectodermal dysplasia in Eda-deficient Tabby mice. Moreover, administration of EDA blocking antibodies to pregnant wild type mice induced in developing wild type fetuses a marked and permanent ectodermal dysplasia. These function-blocking anti-EDA antibodies with wide cross-species reactivity will enable study of the developmental and postdevelopmental roles of EDA in a variety of organisms and open the route to therapeutic intervention in conditions in which EDA may be implicated.

Introduction

The surface ectoderm of the embryo acquires a range of appendages over the course of its development that go on to carry out very diverse functions in the adult. The sites of appendage formation are first marked by activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the embryonic skin epithelium (1–3). The action of the TNF family ligand EDA2 on its receptor EDAR, a target gene of Wnt signaling, is required shortly thereafter at least for sweat glands and some hair types, to stimulate the transcription factor NF-κB, itself necessary for the formation of morphologically distinct cellular condensates called placodes (3, 4). Some placodes, such as those of guard hair developing at embryonic day (E) 14.5, are fully dependent on EDA-EDAR interactions and NF-κB for their formation, whereas others, such as those of undercoat hair developing at around birth, can form in the absence of EDA but produce morphologically abnormal hair (4). In the skin, a pattern of regularly spaced placodes forms as a result of sustained EDAR activation within placodes that induces strong inhibitory signals at the placode periphery. Inhibitory signals are mediated by bone morphogenetic protein-mediated repression of EDAR expression (2). Placodes themselves escape the inhibitory action of bone morphogenetic proteins by producing secreted bone morphogenetic protein inhibitors, presumably with short ranges of action (2, 5).

After placode formation, EDA continues to play roles in the development and maintenance of ectodermal structures. For example, in tooth buds after the placode stage, EDAR is expressed in the enamel knots, which are nonproliferating signaling centers that guide the shaping of the tooth crown (6, 7). The observation of morphological abnormalities in hair from Eda-deficient mice further suggests a role for EDA in the regulation of hair morphogenesis at a postplacodal stage (4). In particular, localization of Shh expression by Wnt and EDA affects axial polarity and shape of hairs (8). Finally, postdevelopmental roles for EDA in controlling sebaceous gland size and the timing of the transition from the anagen to the catagen phase during the hair cycle have been proposed (9, 10), in line with the observation that EDA remains expressed in the adult hair follicle and in skin glands (11). In general, postdevelopmental roles of EDA remain poorly studied, in part because of the lack of suitable reagents allowing for long term pharmacological modulation of EDA activity in adults.

EDA is a membrane-bound TNF family member that must be proteolytically processed to a soluble form to display activity on neighboring EDAR-positive cells (12). EDA contains an intracellular domain with no demonstrated function, and an extracellular domain displaying two overlapping furin consensus cleavage sites, a short basic proteoglycan-binding region, a collagen domain with a kink-introducing interruption in the middle, followed by the TNF homology domain (amino acids 245–391 in human EDA1) responsible for homotrimerization and receptor binding (13, 14). Mutations destroying the furin consensus sequence, the collagen domain, or the TNF homology domain can all cause X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (13), a genetic deficiency characterized by reduced numbers and functionality of various ectoderm-derived structures (15–17). Milder mutations that decrease but do not completely abolish EDA-EDAR interactions correlate with selective tooth agenesis, in which teeth are affected but other appendages are spared from clinically relevant defects (18).

EDA transcripts are produced as two main functional splice variants, encoding EDA1 and EDA2, which differ by two amino acid residues. This minor sequence difference is sufficient to switch the receptor binding specificity from EDAR for EDA1 to XEDAR for EDA2 (19). The EDA1-EDAR axis plays a predominant role in the development of skin-derived structures, whereas EDA2 and XEDAR, also known as EDA2R, have little or no role in this respect (20–24). XEDAR is closely related to the orphan receptor TROY, and an NF-κB-independent role for TROY in hair formation was identified in mice deficient for both TROY and EDA (25). TROY may bind to lymphotoxin α (26), but our laboratory did not detect this interaction (27).

The TNF homology domain of EDA (from Gln-247 to Ser-391) is more conserved than that of any other TNF family member, with human EDA being 100 and 98% identical to mouse and chicken EDA, respectively. Consistent with the high degree of sequence conservation, mouse EDA was found to be functionally active in rescuing scale formation in a teleost fish (28).

In this study, we describe two monoclonal antibodies raised in Eda-deficient mice that efficiently inhibit EDA1 activity both in vitro and in vivo. These antibodies will be useful for immunodetection of EDA protein and to explore the developmental and homeostatic roles of EDA signaling in birds and mammals.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

White-bellied agouti B6CBAa Aw-J/A-EdaTa/J Tabby mice (000314; Jackson Laboratory) and their wild type controls were handled according to Swiss Federal Veterinary Office guidelines, under the authorization of the Office Vétérinaire Cantonal du Canton de Vaud (authorization 1370.5 to P. S.).

Plasmids and Recombinant Proteins

Plasmids used in this study were reported before (14, 27, 29, 30) or constructed using standard molecular biology techniques (Table 1). A fully human form of Fc-EDA1 was kindly provided by Edimer Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, MA).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

Signal, MAIIYLILLFTAVRG; Ig signal, METDTLLLWVLLLWVPGSTG; FLAG, DYKDDDDK; linker, RSPQPQPKPQPKPEPEGS; PreSci, LEVLFQGP; aa, amino acids.

| Plasmid | Designation | Protein encoded | Vector | Figure(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ps515 | EGFP | Enhanced green fluorescent protein | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps548 | FLAG-EDA1 | Signal-FLAG-GPGQVQLQVD-mEDA1 (aa 245–391) | PCR3 | 5B |

| ps930 | hEDAR-Fc | hEDAR (aa 1–183)-VD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470) | PCR3 | 5B |

| ps1196 | Fc-hBAFF | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-PreSci-GSLQ-hBAFF (aa 137–285) | PCR3 | 4 |

| ps1235 | Fc-EDA2 | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQVD-hEDA2 (aa 245–389) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps1236 | Fc-EDA1 | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQVD-hEDA1 (aa 245–391) | PCR3 | 4 |

| ps1431 | hEDAR-GPI | hEDAR (aa 1–183)-VD-hTRAILR3 (aa 157–259) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps1432 | hXEDAR-GPI | Ig signal-DVT-hXEDAR (aa 1–134)-VD-hTRAILR3 (aa 157–259) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps1434 | hTROY-GPI | hTROY (aa 1–168)-VD-hTRAILR3 (aa 157–259) | PCR3 | 6 |

| ps1661 | Fc-PS-EDA1 | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-PreSci-GSLQVD-EDA1 (aa 245–391) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps1938 | Fc-EDA1 | Signal-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-hEDA1 (aa 238–391) | PCR3 | 2, 3, 5C, and 8 |

| ps2199 | hEDAR:Fas | hEDAR (aa 1–183)-VD-hFas (aa 169–335) | pMSCV | 5C |

| ps2290 | chEDAR-GPI | chEDAR (aa 1–183)-VD-hTRAILR3 (aa 157–259) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps2303 | Fc-chEDA1 | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQNSG-chEDA1 (aa 207–353) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps2323 | chTROY-GPI | chTROY (aa 1–167)-VD-hTRAILR3 (aa 157–259) | PCR3 | 6 |

| ps2335 | Fc-chEDA2 | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQ-chEDA1 (aa 207–351) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps2340 | chXEDAR-GPI | Signal-LE-chXEDAR (aa 2–137)-GSVD-hTRAILR3 (aa 157–259) | PCR3 | 5A and 6 |

| ps2485 | Fc-EDA1 V365A | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQVD-hEDA1 (aa 245–391; V365A) | PCR3 | 4 |

| ps2486 | Fc-EDA1 S374A | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQVD-hEDA1 (aa 245–391; S374R) | PCR3 | 4 |

| ps2487 | Fc-EDA1 Q358E | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQVD-hEDA1 (aa 245–391; Q358E) | PCR3 | 4 |

| ps2589 | Fc-EDA1 D316G | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQVD-hEDA1 (aa 245–391; D316G) | PCR3 | 4 |

| ps2590 | Fc-EDA1 T338M | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQVD-hEDA1 (aa 245–391; T338M) | PCR3 | 4 |

| ps2826 | Fc-hAPRIL | Signal-LD-hIgG1 (aa 245–470)-linker-LQ-hAPRIL (aa 98–233) | PCR3 | 2, B and C |

Generation and Purification of Anti-EDA Monoclonal Antibodies

Eda-deficient Tabby mice were immunized with Fc-EDA1 as described previously for EDAR-Fc (30). Cells harvested from mice positive for anti-EDA antibodies were used to generate hybridoma. Hybridoma supernatants were tested for their ability to recognize coated FLAG-EDA1 by ELISA and for their ability to block the binding of FLAG-EDA1 to coated EDAR-Fc in the ELISA format described under “ELISA.” Positive clones were subcloned by limiting dilution and then slowly adapted to serum-containing DMEM or to serum-free Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen). Antibodies were purified from conditioned supernatants of hybridoma grown in DMEM containing 10% low Ig fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) or Opti-MEM by affinity chromatography on protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). Anti-EDA monoclonal antibody Renzo-2 and anti-APRIL monoclonal antibody Aprily2 are commercially available (Enzo Life Sciences). Antibodies (1 mg) were biotinylated in Amicon Ultra 10-kDa protein concentrators (Millipore) in 300 μl of 0.1 m sodium borate buffer, pH 8.8, with 10 μl of 10 mg/ml EZ-LinkTM Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce) in DMSO for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 10 μl of 1 m NH4Cl, and buffer was exchanged for PBS (10 mm sodium-potassium phosphate, 140 mm NaCl, pH 7.2) by diafiltration.

Transfections

HEK 293T cells were grown in DMEM, 10% fetal calf serum and transfected by the calcium phosphate method. Cells were grown for 7 days in serum-free Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen) for the production of human or chicken Fc-EDA1 and 2 or for 48 h in complete medium for surface expression of receptors-TRAILR3 fusion proteins.

ELISA

For the detection of anti-EDA antibodies, ELISA plates were coated with FLAG-EDA at 1 μg/ml, blocked, and revealed with anti-EDA antibodies (adequately diluted serum of EDA immunized Tabby mice, hybridoma supernatants, or purified antibodies) followed by a peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse IgG (1/5000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For isotype determination, ELISA plates were coated with 0.2 μg/ml of FLAG-EDA1 and revealed with anti-EDA antibodies followed by peroxidase-coupled antibodies against the heavy chain of mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, or IgM (all from Jackson ImmunoResearch). For epitope mapping, ELISA plates were coated with 1 μg/ml of purified Fc-EDA1 or with 1 μg/ml of Fc-EDA1 carrying point mutations D316G, T338M, Q358E, V365A, and S374R and revealed with anti-EDA antibodies at 1 μg/ml followed by peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse IgG (1/8000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For the differential recognition of plate-bound versus native Fc-EDA1, ELISA plates were coated either directly with Fc-EDA1 at 1 μg/ml, or with a goat anti-human Ig antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch 109-005-098) at 5 μg/ml, followed, after blocking, by Fc-EDA1 at 1 μg/ml. Plates were revealed with serial dilutions of anti-EDA antibodies, followed by peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse IgG (1/8000). For the competition ELISA-like assay, plates were coated with 1 μg/ml of EDAR-Fc and revealed with titrated amounts of FLAG-EDA1 that had been preincubated for 1 h with buffer or with 125 ng/ml of anti-EDA antibodies. Bound FLAG-EDA1 was revealed with 0.5 μg/ml of biotinylated anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma) and peroxidase-coupled streptavidin (1/5000). For the screening of hybridoma supernatants, an amount of FLAG-EDA1 giving maximal, nonsaturating signal was preincubated in hybridoma supernatants for 1 h prior to addition on EDAR-Fc-coated ELISA plates. For the sandwich ELISA, ELISA plates were coated with 5 μg/ml of anti-EDA antibodies or 5 μg/ml of goat anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch 109-005-098). The plates were saturated with 4% powdered skimmed milk and 0.5% Tween 20 in PBS. Titrated amounts of Fc-EDA1 were added (in saturation buffer diluted 1/10 in PBS, in the presence or absence of 50% mouse or 50% human serum) and revealed either with 1 μg/ml of biotinylated anti-EDA antibodies followed by peroxidase-coupled streptavidin (1/5000) or with peroxidase-coupled goat anti-human IgG (1/5000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch 109-035-003).

SDS-PAGE, Western Blot, and Native Gel Electrophoresis

Anti-EDA antibodies (10 μg/lane) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions followed by Coomassie Blue staining. To test the ability of anti-EDA antibodies to recognize denatured EDA1, 50 or 200 ng of Fc-EDA1 and 500 ng of Fc-APRIL were denatured for 3 min at 70 °C in SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 30 mm dithiothreitol and revealed by Western blotting with the various anti-EDA antibodies at 1 μg/ml, followed by peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse antibody (1:8000) and ECL reagent (GE Healthcare).

Sequencing of Anti-EDA Antibodies

RNA was extracted from hybridoma cells with an RNAeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription with Ready-To-Go T-Primed first strand kit (GE Healthcare). Variable sequences of the heavy and light chains were amplified by PCR as described (31, 32). PCR products were sequenced on both strands. Sequences were analyzed for gene usage using the IMGT sequence alignment software.

FACS Analyses

293T cells co-transfected with EGFP and receptor-GPI expression plasmids were stained with human or chicken Fc-EDA1 or Fc-EDA2 in conditioned serum-free medium, or with anti-TRAILR3 antibody essentially as described before (27). In addition, Fc-EDAs in serum-free supernatants of transfected 293T cells (25 μl) were preincubated for 1 h at room temperature in the presence or absence of 2 μg of anti-EDA antibodies prior to staining. Cells were analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays

Fas-deficient hEDAR-Fas Jurkat cells have been described before (14). These reporter cells were exposed to increasing amounts of Fc-EDA1 that had been preincubated with fixed concentrations of anti-EDA antibodies. The cytotoxicity assay using EDAR-Fas Jurkat cells was performed as described for FasL on Jurkat cells (33).

Administration of Proteins to Eda-deficient and Wild Type Animals

Eda-deficient Tabby pups were treated on the day of birth, as described, with one intraperitoneal injection of Fc-EDA1 at 2.5 mg/kg that was preincubated for 1 h with anti-EDA antibodies EctoD1 (n = 3) or EctoD2 (n = 4) at 10 mg/kg (30). Examination of tail hairs and sweat tests were performed at weaning. Pregnant WT mice (one mouse/antibody) were treated intravenously every second to fourth day with anti-EDA antibodies at 4 mg/kg throughout pregnancy. After birth, treatment was continued for 2–3 weeks in half of the pups (n = 2, 3, and 4 for EctoD1, EctoD2, and EctoD3, respectively) with intraperitoneal injections at the same dose and frequency but was interrupted in the other half of the pups (n = 2, 3, and 5 for EctoD1, EctoD2, and EctoD3, respectively). Offspring were analyzed at weaning (3 weeks) for external phenotypes and sweat tests and at 1 month of age for histology and tooth analysis, essentially as described (34). Age-matched wild type and Eda-deficient Tabby mice were similarly analyzed for comparison. Tracheal glands were detected by Alcian blue staining (35). Skulls were prepared by digesting soft tissues for 6 h at 55 °C with proteinase K (20 μl of proteinase K (Roche Applied Science) in 8 ml of 10 mm Tris, pH 8, 5 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5% SDS) and then rinsing with water. Remaining tissues were removed with fine tweezers; jaws were placed in 20% ethanol for 2 days, incubated in 3% H2O2 for 16 h, rinsed with water, dried, and photographed with a M205FA stereomicroscope (Leica).

RESULTS

Generation of Anti-EDA Antibodies That Recognize Surface-exposed Epitopes of EDA

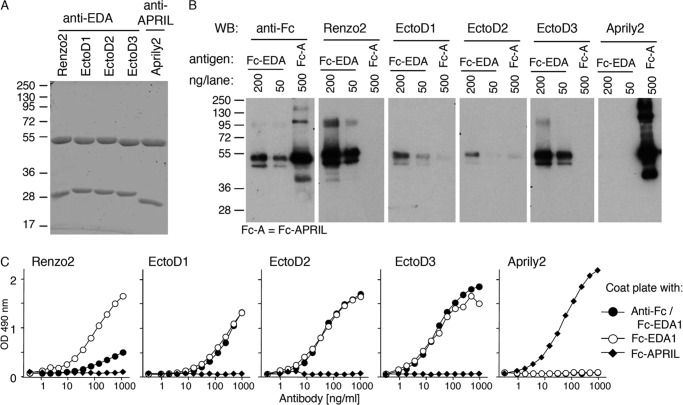

The extracellular, receptor-binding region of EDA is identical at the amino acid level between human and mouse. To generate blocking anti-EDA antibodies, Eda-deficient Tabby mice were immunized with an active recombinant form of EDA1, Fc-EDA1. In this strain, exon 1 of the Eda gene is deleted such that these animals express no EDA protein (36). Though only weak titers of anti-EDA antibodies were detected in immunized mice, their sera displayed EDA blocking activity (data not shown). Three EDA-specific hybridoma were obtained, subcloned, and established. Antibodies secreted by these hybridoma, named EctoD1, EctoD2, and EctoD3, were IgG1 with distinct variable gene usage for both the heavy and light chains (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Purified antibodies (Fig. 2A) were tested for their recognition of denatured and native EDA1. EctoD1 and EctoD2 weakly recognized reduced Fc-EDA by Western blot, whereas EctoD3 produced a more convincing signal on Fc-EDA1, but not on an excess of the control protein Fc-APRIL. This signal remained, however, weaker than that obtained with the commercial anti-EDA antibody Renzo2 (Fig. 2B). An ELISA assay was performed in which the antigen Fc-EDA1 was either coated directly to the plate, a process that partially denatures proteins, or else was captured via its Fc portion to maintain its native structure. Renzo2 displayed better recognition of coated rather than captured Fc-EDA1, suggesting that it preferentially recognized an epitope in the denatured protein (Fig. 2C). In contrast, EctoD1, EctoD2, and EctoD3 recognized both coated and captured Fc-EDA1 with similar signal intensities, suggesting that they recognize surface-exposed epitopes in EDA1 (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results suggest that Renzo2 may recognize a linear, partially buried epitope, whereas EctoD1, EctoD2, and EctoD3 preferentially bind to surface epitopes that may not be linear in the primary sequence.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of anti-EDA monoclonal antibodies

IGHV and IGLV, immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, respectively, variable region genes likely used in the antibody; Block EDA1, able to prevent the binding of EDA1 to EDAR; Block EDA2, able to prevent the binding of EDA2 to XEDAR; mAb/EDA1 ELISA, number of anti-EDA antibody molecules required to block half of the activity of one trimeric FLAG-EDA1 molecule in the ELISA binding assay; mAb/EDA1 reporter, number of anti-EDA antibody molecules required to block half of the killing activity of one hexameric Fc-EDA1 molecule in the reporter cell assay using EDAR, Fas-expressing Jurkat cells.

| Anti-EDA | IGHV gene | IGLV gene | Iso-type | Block EDA1 | Block EDA2 | mAb/EDA1 ELISA | mAb/EDA1 reporter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EctoD1 | 1–26 | 3–4 | IgG1 | No | No | NA | NA |

| EctoD2 | 5–9 | 3–5 | IgG1 | Yes | Yes | 1.4 | 4.9 |

| EctoD3 | 1–81 | 3–12 | IgG1 | Yes | Yes | 1.1 | 2.3 |

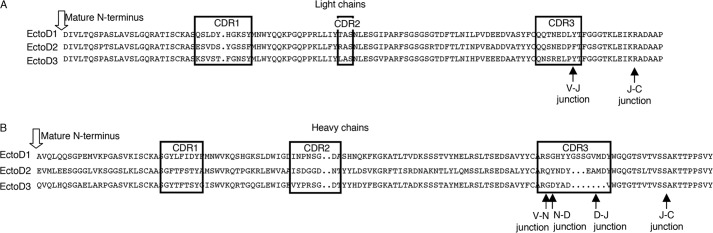

FIGURE 1.

Amino acid sequences of anti-EDA antibodies. A, sequences of light chains. Complementarity-determining regions (CRD) are boxed. B, sequences of heavy chains. Black arrows indicate boundaries of sequences coded by the variable (V), diversity (D), joining (J), and constant (C) genes. N, sequence coded by random addition of nucleotides.

FIGURE 2.

Anti-EDA antibodies recognize epitopes on native EDA1. A, SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie Blue staining of 10 μg/lane of the indicated purified mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibodies under reducing conditions. Migration positions of molecular mass standards (in kDa) are shown. B, Fc-EDA1 (200 or 50 ng) and Fc-hAPRIL (Fc-A, 500 ng) were resolved by Western blotting (WB) under reducing conditions and revealed with anti-human immunoglobulin (anti-Fc), anti-EDA (Renzo2, EctoD1, EctoD2, or EctoD3), or anti-APRIL (Aprily2) antibodies. C, purified Fc-EDA1 and Fc-APRIL proteins were coated directly in an ELISA plate. Fc-EDA1 was also captured via the Fc portion using an anti-human antibody. Coated proteins were revealed with the indicated antibodies at the indicated concentrations.

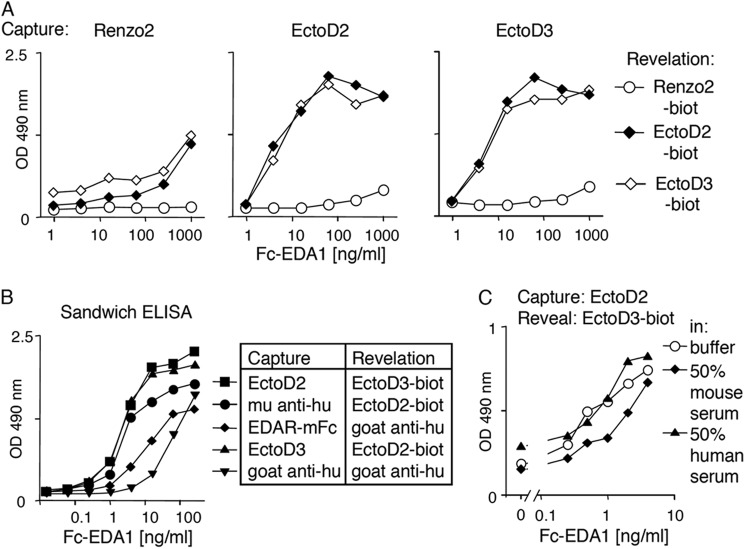

Sensitive Detection of Fc-EDA by Sandwich ELISA

Prenatal or neonatal Fc-EDA1 treatment has successfully been used in different animal models of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia to improve several aspects of the disease (34, 37). Because Fc-EDA1 is currently being tested in clinical trials, its sensitive detection is important to enable monitoring of its pharmacologic parameters. Renzo2, EctoD2, and EctoD3 were tested in various combinations for their ability to recognize Fc-EDA1 in a sandwich ELISA. Whereas Renzo2 was relatively inefficient at both capture and revelation, EctoD2 and EctoD3 detected Fc-EDA1 at less than 1 ng/ml and compared favorably to other sandwich detection systems based on recombinant EDAR or anti-Fc reagents (Fig. 3, A and B). Importantly, sensitive detection of Fc-EDA1 was readily achieved in the presence of 50% human serum and only slightly reduced in the presence of 50% mouse serum (Fig. 3C). Thus, EctoD2 at capture and EctoD3 at revelation form an efficient pair of antibodies for the sensitive detection of Fc-EDA1.

FIGURE 3.

Sensitive detection of Fc-EDA1 in serum by sandwich ELISA. A, sandwich ELISAs for Fc-EDA1 were performed using anti-EDA antibodies (Renzo2, EctoD2, and EctoD3) at capture and biotinylated forms of the same antibodies for detection. Biotinylated antibodies were revealed with horseradish-coupled streptavidin. B, comparison of sandwich ELISAs for Fc-EDA1 using EctoD2, EctoD3, EDAR-Fc, or anti-human immunoglobulin antibodies at capture and biotinylated EcotD2, EctoD3, or horseradish-coupled goat anti-human (hu) immunoglobulin for revelation. C, comparison of sandwich ELISA (EctoD2 and biotinylated EctoD3) for Fc-EDA1 in buffer or in the presence of 50% mouse or human serum.

Anti-EDA Antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3 Recognize Epitopes That Overlap with the Receptor-binding Site on Two Adjacent EDA Monomers

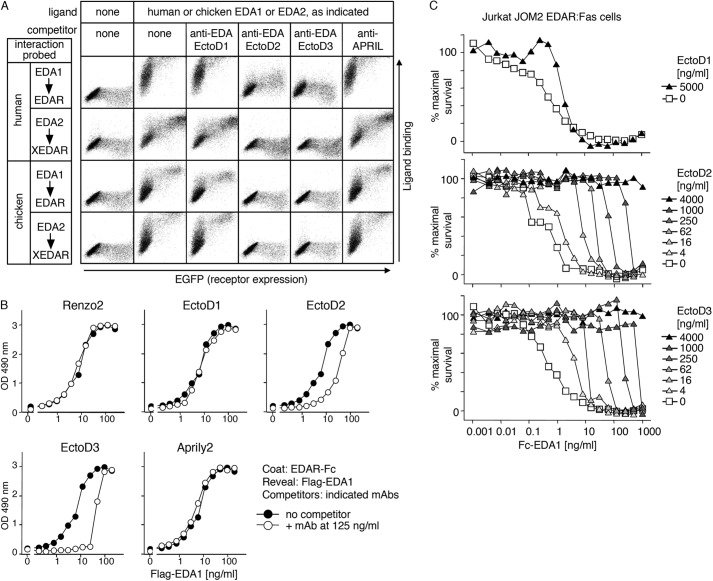

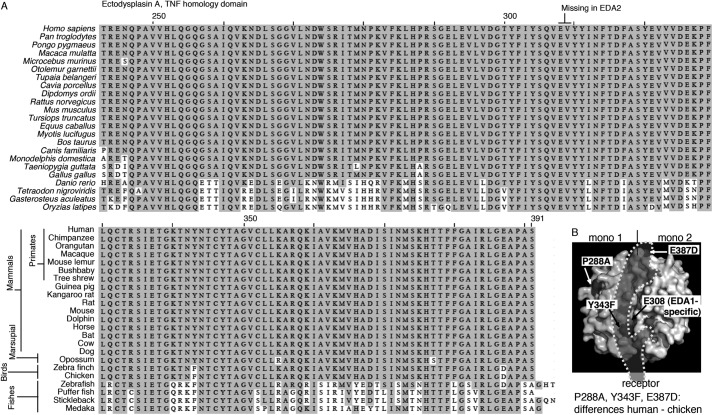

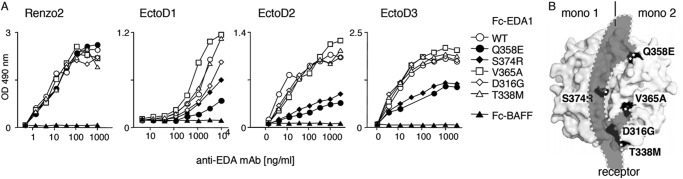

The recognition of Fc-EDA1 by anti-EDA antibodies was tested on a panel of EDA1 mutations occurring in patients with nonsyndromic tooth agenesis. These mutants are characterized by reduced binding to EDAR and/or impaired signaling capability (18). Renzo2 recognized wild type and mutant Fc-EDA1 proteins equally well. EctoD2 and EctoD3 detected mutants Q358E or S374R with reduced intensity, suggesting that these two amino acid residues are part of the epitope (Fig. 4A). EctoD1 displayed the same general behavior as EctoD2 and EctoD3, although with less sharp discrimination between the different EDA mutant proteins (Fig. 4A). In the crystal structure of EDA1 (38), Ser-374 and Gln-358 are located in the membrane-proximal portion of the TNF homology domain, lining the predicted receptor-binding site on two adjacent EDA1 monomers (Fig. 4B). The recognition site of EDA1 by EctoD2 and EctoD3 is therefore predicted to overlap with the receptor-binding site, suggesting that these antibodies may interfere with receptor binding.

FIGURE 4.

Anti-EDA antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3 recognize epitopes overlapping the EDA receptor-binding site. A, Fc-EDA1 WT or containing the indicated point mutations, or Fc-BAFF as a control, were coated onto ELISA plates and revealed with the indicated antibodies at the indicated concentration. B, space filling representation of EDA1 structure (from Protein Data Bank coordinate file 1RJ7), showing one of the EDA1 monomers on the left (mono 1) and one on the right (mono 2). Positions of point mutants used in Fc-EDA1 of A are shown in black. The predicted binding site of EDAR is shown as a shade of gray (receptor). In this representation, the membrane of the receptor-bearing cell would be at the bottom, and the collagen domain of EDA1 would be at the top.

Blocking Anti-EDA Antibodies Inhibit EDA1 and EDA2 of Mammalian and Avian Origin

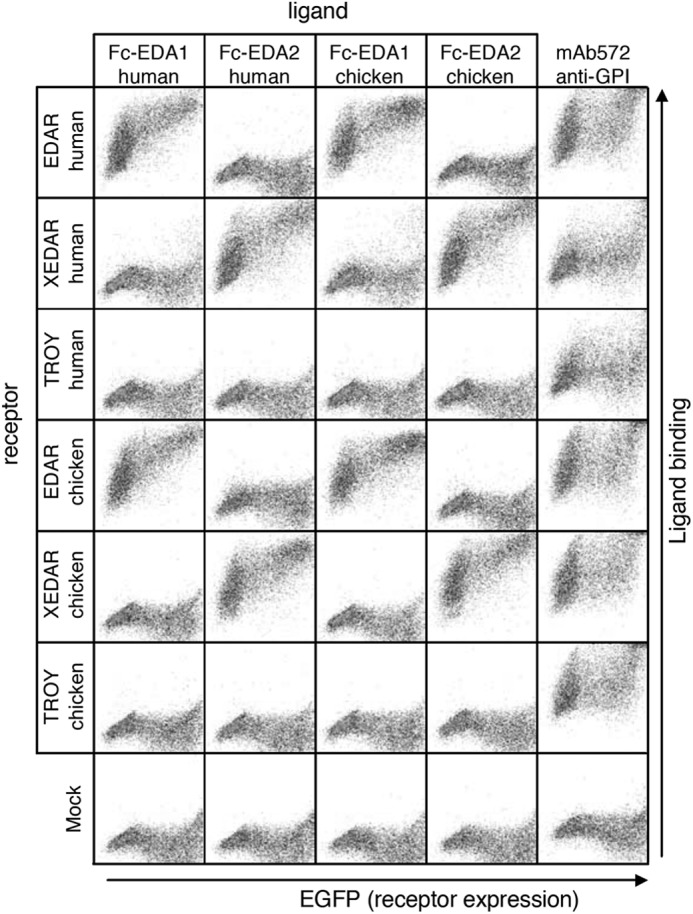

The ability of anti-EDA antibodies to inhibit EDA was first tested in a FACS-based assay in which various Fc-EDA in conditioned medium, preincubated or not with anti-EDA antibodies, were used to stain 293T cells transfected with the extracellular domains of various EDA receptors fused to the glycolipid anchor addition signal of TRAILR3 (27). In this system, human and chicken Fc-EDA1 and Fc-EDA2 specifically stained cells transfected with their cognate receptors (human or chicken EDAR or XEDAR) (Fig. 5A), but none of them bound to human or chicken TROY (Fig. 6). Although the anti-EDA EctoD1 and the control Aprily2 antibodies did not interfere with Fc-EDA staining, anti-EDA antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3 efficiently blocked the binding of Fc-EDA1 to EDAR and of Fc-EDA2 to XEDAR in both human and chicken systems (Fig. 5A). The inhibitory pattern is consistent with (a) the location of epitopes recognized by EctoD2 and EctoD3, (b) with the difference between mammalian and chicken EDA being only three amino acids in the entire C-terminal, receptor-binding region of EDA, and (c) with the fact that, compared with EDA1, EDA2 lacks just two amino acid residues within the receptor-binding sites (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 5.

Anti-EDA monoclonal antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3 inhibit mammalian and avian EDA1 and EDA2. A, receptors (human or chicken EDAR or XEDAR) fused to the GPI anchor of TRAILR3 were expressed in 293T cells together with an EGFP tracer (x axis). Cells were stained with or without cell supernatants containing Fc-EDA1 or Fc-EDA2 of human/mouse (human) or chicken origin (y axis). The interactions of Fc-EDAs with GPI-anchored receptors were challenged by preincubation of the ligand with anti-EDA antibodies (EctoD1, EctoD2, and EctoD3) or with an irrelevant antibody (anti-APRIL). Both scattergram axes show fluorescence intensity on a logarithmic scale (100–104). B, FLAG-EDA1 was diluted at the indicated concentrations and preincubated with or without 125 ng/ml concentration of anti-EDA (Renzo2, EctoD1, EctoD2, or EctoD3) or anti-APRIL (Aprily2) monoclonal antibodies. The binding of FLAG-EDA1 to coated EDAR-Fc protein was then probed by an ELISA-like assay. C, EDA1-sensitized Jurkat JOM2 EDAR-Fas reporter cells were incubated in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Fc-EDA1, in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of anti-EDA monoclonal antibodies EctoD1, EctoD2, or EctoD3. Cell viability was determined by colorimetry (phenazine methosulfate/(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium assay) and expressed as percentage of maximal survival.

FIGURE 6.

Receptor binding specificity of human and chicken EDA1 and EDA2. Receptors (human or chicken EDAR, XEDAR, or TROY) fused to the GPI anchor of TRAILR3 were expressed in 293T cells together with an EGFP tracer (x axis). Cells were stained with cell supernatants containing human or chicken Fc-EDA1 or Fc-EDA2. Expression of GPI-anchored receptors was monitored with a monoclonal antibody (mAb572) recognizing the C-terminal portion of TRAILR3 present in all receptors. Both scattergram axes show fluorescence intensity on a logarithmic scale (100–104).

FIGURE 7.

TNF homology domain alignment of EDA1 from various species. A, scientific and common names of the various species are indicated on the left-hand sides of the top and bottom parts of the alignment, respectively. The two amino acid residues absent in EDA2 are indicated at the top of the sequence. B, space filling representation of EDA1 structure (from Protein Data Bank coordinate file 1RJ7) as described in the legend to Fig. 3B, but highlighting the position of amino acid residues differing between human and chicken EDA. The location of Glu-308 that is present in EDA1 but not in EDA2 is also shown.

Blocking Anti-EDA Antibodies Inhibit Human EDA1 Binding to EDAR at Close to Stoichiometric Ratio

The blocking activity of anti-EDA antibodies was also evaluated in an ELISA-like-based assay, in which the binding of FLAG-tagged EDA1 to coated EDAR-Fc was monitored after preincubation with or without various anti-EDA antibodies. EctoD2 and EctoD3 decreased the binding signal, whereas Renzo2, EctoD1, and Aprily2 did not (Fig. 5B). At the EC50 of inhibition, the ratio of monomeric antibody to FLAG-tagged EDA1 trimer, assuming a molecular mass of 150 kDa for the antibody and 59 kDa for the EDA1 trimer, was 1.4 for EctoD2 and 1.1 for EctoD3, i.e., close to stoichiometry (Table 2). It is noteworthy that the shape of the curve obtained seems to indicate a more potent inhibition by EctoD3 compared with EctoD2 (Fig. 5B).

Blocking Anti-EDA Antibodies Inhibit EDAR Activation in Vitro and in Vivo

The inhibitory activities of anti-EDA antibodies were further evaluated in a functional assay, in which the ability of Fc-EDA1 to trigger the apoptotic Fas pathway in a surrogate reporter cell line expressing the EDAR-Fas fusion receptor was assessed (14). EctoD2 and EctoD3 totally protected the reporter cells from Fc-EDA1-induced death when an excess of inhibitory antibody was preincubated with Fc-EDA1 (Fig. 5C). The average ratio of antibody to hexameric Fc-EDA1 to achieve EC50 of inhibition at different antibody concentrations, assuming a molecular mass of 262 kDa for the Fc-EDA1 hexamer, was 4.9 for EctoD2 and 2.3 for EctoD3 (Table 2). Assuming that each antibody has two binding sites and each Fc-EDA1 hexamer displays six epitopes, this corresponds to 1.6 and 0.8 antibody binding sites per epitope on Fc-EDA1.

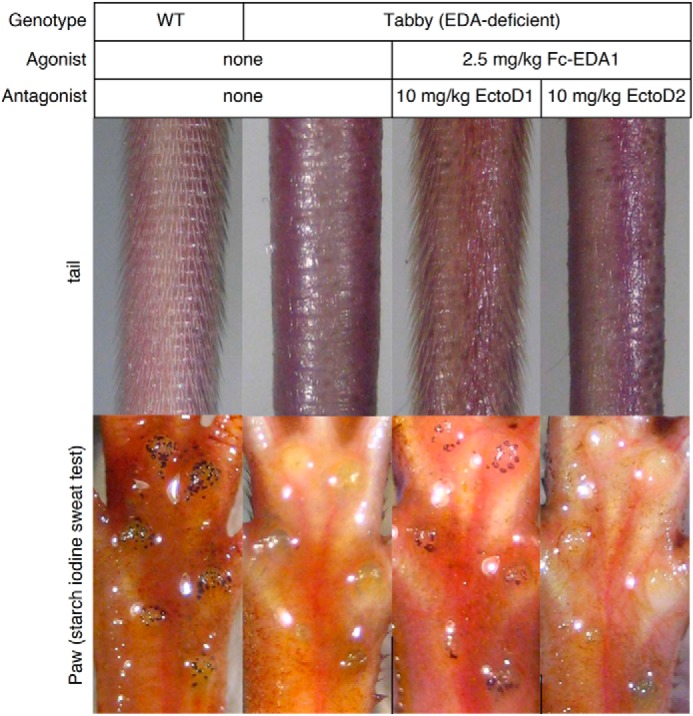

The EDAR-Fas reporter cell line does not measure EDAR signaling achieved through its native intracellular domain. To investigate whether anti-EDA antibodies could block the action of EDA1 in a physiologically relevant context, Fc-EDA1 preincubated with a 4-fold mass excess of either EctoD1 or EctoD2 was administered to newborn Eda-deficient mice, and the ability of Fc-EDA1 to induce development of tail hair and functional sweat glands through activation of endogenous EDAR in these animals was monitored (34). The EctoD1 antibody, which did not block EDA receptor binding or function in vitro, did not prevent Fc-EDA1 from rescuing ectodermal dysplasia symptoms as judged from the formation of tail hair and sweat glands in these mice. The blocking antibody EctoD2, however, was capable of completely suppressing the therapeutic effect of Fc-EDA1 in this model (Fig. 8). Taken together, these results indicate that the anti-EDA antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3 inhibit the action of EDA1 at close to stoichiometric ratio.

FIGURE 8.

Anti-EDA monoclonal antibody EctoD2 blocks the therapeutic activity of Fc-EDA in vivo. Wild type or Eda-deficient Tabby mice were analyzed at weaning (3 weeks old) for the presence or absence of hair on the tail and functional sweat glands in footpads using a starch-iodine sweat assay. Eda-deficient mice were either left untreated or treated on the day of birth with Fc-EDA1 at 2.5 mg/kg that had been preincubated with a 4-fold mass excess of either EctoD1 (n = 3) or EctoD2 (n = 4) monoclonal antibodies, as indicated. All mice in a treatment group displayed identical phenotypes.

Blocking Anti-EDA Antibodies Induce Ectodermal Dysplasia in Developing Wild Type Mice

To assess whether EctoD2 and EctoD3 can inhibit endogenous EDA1 and not only recombinant EDA1 after preincubation, gravid wild type females were administered either EctoD2 or EctoD3, or EctoD1 as a negative control, at a dose of 4 mg/kg at regular intervals throughout pregnancy. After birth, treatment was continued in half of the pups and discontinued in the other half, and the phenotype of pups was assessed after completion of development (at 3 weeks and 1 month of age) (Figs. 9 and 10). Control wild type pups treated with the non-blocking antibody EctoD1 were, as expected, indistinguishable from untreated wild type mice (Figs. 9 and 10). However, wild type mice exposed to the blocking antibodies EctoD2 or EctoD3 throughout development closely resembled Eda-deficient Tabby mice with respect to several characteristics: a total absence of guard hairs, the presence of a kink at the tail tip (however not as marked and more “wavy” than in Eda-deficient mice), absence of hair in the retroauricular region, thick and scaly eyelids with a semi-closed eye phenotype, complete absence of functional sweat glands and glandular tissue in footpads, small upper and lower molars with a simplified cusp pattern compared with wild type, and a total absence of mucus-secreting glands in the trachea and lipid-secreting mebomian glands in eyelids (Figs. 9 and 10). Similar results were obtained in pups where treatment with EctoD2 or EctoD3 ceased at birth (Figs. 9 and 10). Therefore, wild type mice treated with blocking anti-EDA antibodies acquire a phenotype closely resembling that of Eda-deficient mice, with the striking exception of tail hair that still developed in treated mice, although these hairs were present with reduced density in EctoD3-treated mice, where the frequency of antibody administration was higher (Figs. 9 and 10). Taken together, these results indicate that administration of anti-EDA antibodies EctoD2 or EctoD3 in developing wild type mice induces a phenotype of ectodermal dysplasia with almost all of the phenotypic characteristics observed in Eda-deficient mice.

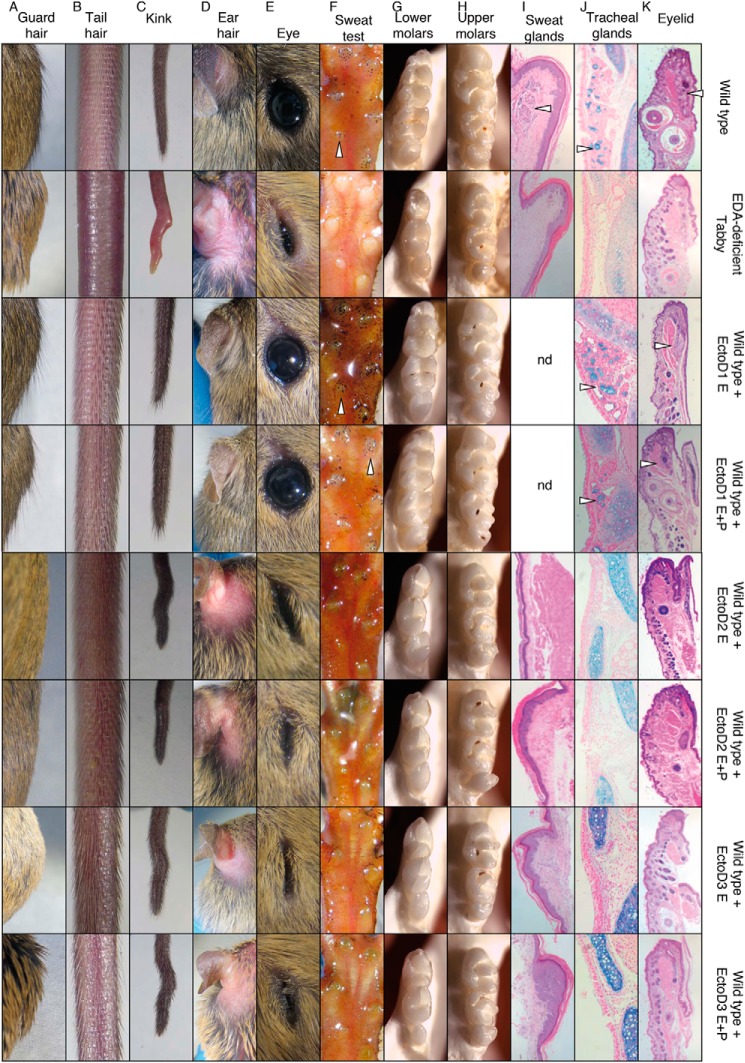

FIGURE 9.

Anti-EDA monoclonal antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3, but not EctoD1, induce ectodermal dysplasia when administered during embryonic development in wild type mice. Pregnant wild type mice were treated intravenously every second or fourth day with EctoD1 (E0, E2, E4, E6, E8, E10, E12, E14, E16, and E18 ±[P1, P2, P4, P6, P8, P10, P14, P16, and P18]), EctoD2 (E5, E9, E12, and E16 ±[P2, P6, P10, P14, and P16]), or EctoD3 (E3, E5, E8, E10, E12, E14, E16, and E18 ±[P1, P3, P5, P7, P9, P11, P13, P15, P17, and P19]) at 4 mg/kg throughout pregnancy. Treatment was stopped at birth in half of the pups and continued in the other half of the pups at the same dose up to the age of 16–19 days. All pups were analyzed at 3 weeks of age for their external appearance and at 1 month for necropsy. Untreated wild type and Eda-deficient Tabby mice were similarly analyzed for comparison. The figure shows results for one animal per group. Phenotype within a group was very similar or identical. Treatment E+P, treatment was performed during embryogenesis and continued postbirth by intraperitoneal injections in pups. Treatment E, treatment was performed during the embryogenesis only, and pups did not receive intraperitoneal injections postbirth. A, back hair with protruding guard hairs. B, tail hair phenotype. C, phenotype of the tip of the tail. D, top view of the retroauricular region. E, eye phenotype. F, footpads with functional sweat glands visualized as black dots (arrowheads) with the starch iodine test. G, lower molars, with the anterior part on the top. H, upper molars, with the anterior part on the top. I, sections of footpads with glandular structures of sweat glands (arrowhead), stained with hematoxylin and eosin. J, sections of the trachea stained with Alcian blue to reveal mucus-secreting glands (arrowheads). K, eyelid sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, with glandular structure of meibomian glands (arrowheads).

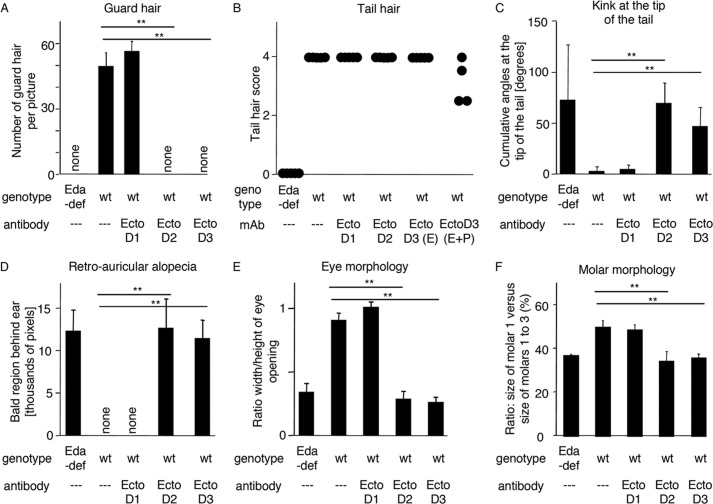

FIGURE 10.

Anti-EDA monoclonal antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3 induce ectodermal dysplasia when administered during embryonic development in wild type mice. Some of the parameters shown in Fig. 9 were quantified. Mice treated in utero and mice treated in utero and postbirth with the same antibody were pooled for the analysis, except for mice treated with the anti-EDA antibody EctoD3 in the analysis of tail hair. A, number of guard hairs visible in pictures similar to those shown in Fig. 9A, as a function of genotype and treatment. B, tail hair score, according to the following scoring system (30): score 0, no hair (like in Eda-deficient mice); score 1, sparse hair on the lower face of the tail; score 2, dense hair on the lower face of the tail; score 3, dense hair on both faces of the tail; score 4, very dense hair (like wild type). Each dot represents a mouse. C, tail kink score. A broken line was drawn on pictures of the tail tip (such as those shown in Fig. 9C), and the sum of the angles was plotted as a function of genotype and treatment. D, the bald area behind the ears was delimited manually on pictures similar to those of Fig. 9D, and the surface area of these regions was quantified using ImageJ. E, the width and height of the eye opening was measured on pictures similar to those of Fig. 9E. The height to width ratio was plotted as a function of genotype and treatment. F, the length of the first lower molar and the length of lower molars 1, 2, and 3 taken together was measured in pictures similar to those of Fig. 9G. The ratio between these distances was calculated. Measures were taken on both lower jaw quadrants. Treatment sometimes resulted in the absence of a third molar, as can sometimes be observed in Eda-deficient mice. Quadrants lacking the third molar were excluded form the analysis (one quadrant for embryonic treatment with EctoD2 and two quadrants for embryonic and postbirth treatment with EctoD3). The numbers of mice were as follows: Eda-deficient (Eda-def): n = 5; wild type (wt): n = 5; wt + anti-EDA EctoD1: n = 4; wt + anti-EDA EctoD2: n = 6; wt + anti-EDA EctoD3: n = 9 (n = 4 for continuous treatment (E+P) and n = 5 for in utero treatment only (E)). Means ± standard deviation are shown. **, p value < 0.005, as determined with Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

The EDA pathway operates early in skin development, such that its abolition by mutation results in the loss or altered development of a range of cutaneous appendages. These early developmental roles of the EDA pathway are the most intensively studied, in part because the lifelong morphological effects of Eda mutation make it difficult to separate its developmental roles from potential homeostatic roles in the adult. To enable sensitive detection and effective suppression of EDA at any developmental stage, we sought to generate function-blocking anti-EDA monoclonal antibodies with broad species specificity.

The TNF homology domain of EDA is 100% conserved across most mammals (Fig. 7). Antibodies against such conserved, functional domains are usually easier to raise by immunizing mutant animals that have never expressed the protein of interest. Two anti-EDA antibodies obtained through this approach inhibited EDA at an approximately 1:1 ratio, pointing to their quality in this respect. In a sandwich ELISA, these antibodies allowed sensitive detection of recombinant EDA in both buffer and serum, which will be useful, for example to measure distribution of the recombinant EDA protein undergoing clinical trials. We identified two amino acid residues in EDA whose mutation partially reduced antibody binding. These residues are most probably recognized on adjacent monomers of the EDA trimer, on each side of the receptor-binding site, because they would be too far apart if recognized within a single monomer (Fig. 4B). Although EctoD2 and EctoD3 still recognized the mutant versions of Fc-EDA by ELISA, it is noteworthy that we selectively failed to purify these mutants by affinity chromatography with immobilized EctoD2 or EctoD3, whereas wild type Fc-EDA and other mutants were readily purified on these affinity columns (data not shown).

Ser-374 of EDA1, which is part of the epitope recognized by both EctoD2 and EctoD3, is relatively close to Glu-308, which is absent in the EDA2 splice form, and Tyr-343, which is substituted with a phenylalanine residue in EDAs of avian origin. The closeness of these sequence differences to the epitope raised the question of whether these antibodies would recognize EDA2 and avian EDA (Figs. 5 and 6). In fact, antibodies EctoD2 and EctoD3 effectively inhibited EDA1 and EDA2 of human and bird origin. These antibodies can thus probably be used to study EDA function in a wide range of species not necessarily easily amenable to genetic manipulations. Of particular relevance, chicken is used as a model for the study of feather development, and EDA is involved in this process (39, 40). Based on the careful sequence analysis of EDA, EDAR, XEDAR, and TROY in various species, it has been hypothesized that TROY might be the receptor for EDA2 in vertebrates, with the exception of therians (i.e., marsupials and placental mammals) where the specificity of EDA2 would have shifted to XEDAR. Indeed, the substitution of Phe-343 (in birds and other tetrapods) by Tyr-343 (in therians) correlates with important sequence differences in XEDAR and TROY within the (putative) EDA2-binding region (41). However, the direct demonstration of the interaction of EDA2 with XEDAR (and not TROY) using chicken proteins goes against this hypothesis and rather suggests that EDA2 binding to XEDAR is conserved across the vertebrates.

To achieve in vivo effects, blocking antibodies should not only inhibit EDA but also be able to penetrate relevant tissues during the stages at which this signal is active. In the experiments described here, which tested the ability of the antibodies to reproduce the developmental effects of EDA signal ablation, this critical time window was through embryonic development. Young mammals need some time after birth until they can produce their own protecting antibodies, for example against common bacteria epitopes. In the meantime, they acquire the spectrum of antibodies present in maternal serum by one or both of the following ways: (a) in utero transplacental antibody transport (active in humans but less efficient in mice (42)) and/or (b) postnatal import of maternal antibodies present in milk via an antibody transport system in the gut epithelium (active in mice but less in humans) (42, 43). The induction of an Eda-deficient phenotype in pups of wild type mothers receiving antibodies intravenously shows that enough antibody was transported to inhibit the developmental function of EDA at relatively early time points, because EDAR expression in the oral epithelium starts at embryonic day 10 (7).

Although wild type mice exposed to blocking anti-EDA antibodies acquired an Eda-deficient phenotype, tail hair formation was not fully abrogated. This cannot be explained by an insufficient amount of systemic antibody at the onset or end of treatment because guard hairs, which develop before tail hairs, were inhibited, and so were sweat glands that can be induced at the same time or even after tail hair (34). We can also rule out the hypothesis that tail hair can form independently of EDA1 and EDAR, because both Eda-deficient and Edar-deficient mice lack tail hair (21). We rather hypothesize that blocking anti-EDA antibody levels have dropped below the efficacy threshold in tail tissue of the developing mice during a short period of time. Tail hair formation in Eda-deficient mice can indeed take place upon exposure to active EDA for a period as short as 4 h (14). It is also possible that access of the antibody to tail tissue is more difficult than to other parts of the body.

There are at least two possible explanations for the origin of the kink at the tip of the tail of Tabby mice. On the one hand, in the absence of hair and hair-associated skin stem cells, tail skin growth is impaired (44). This suggests that kink formation could result from a compression of the forming vertebrae by the skin that is too tight. On the other hand, bone density is reduced in epiphysis of Eda-deficient vertebra (45), a defect that may participate to kink formation. Here, we observe that mice treated with anti-EDA antibodies develop a Tabby phenotype, with the exception of the hairy tail. The observation that these mice have attenuated kinks fits well with the hair-dependent skin growth model but also suggests that additional, vertebra-intrinsic EDA defects may be at play in the genesis of kinks.

Mice in which treatment with the EDA blocking antibody was interrupted after the in utero period displayed a phenotype as severe as those in which treatment was continued post birth. Because it is known that sweat glands can be induced after birth (34), this indicates that half-life of the antibodies is long enough to cover this phase or that it has been transferred postbirth from mother to pups via milk.

Blocking anti-EDA antibodies will be useful to investigate postdevelopmental functions of EDA and may open the way for applications in adults. Eda-deficient mice overexpressing an Eda1 transgene throughout development displayed correction of several ectodermal defects and developed a phenotype of sebaceous gland hyperplasia (9). Sebaceous gland size was normalized following inducible shutdown of the transgene in adult mice, indicating a likely trophic (non-developmental) role for EDA in the regulation of sebaceous gland size (9). Inhibition of EDA might therefore be beneficial in conditions with deregulated glandular activity, such as acne or seborrhea.

Acknowledgment

We thank Kenneth Huttner (Edimer Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA) for interest and suggestions for this project.

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (to P. S.) and by project funding from Edimer Pharmaceuticals (to O. G., H. S., D. H., and P. S.). O. G. and P. S. are shareholders of Edimer Pharmaceuticals. N. K. is shareholder, director, and employee of Edimer Pharmaceuticals. H. S. is a member of the clinical advisory board of Edimer Pharmaceuticals.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the DDBJ/GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) KF790596–KF790601.

- EDA

- ectodysplasin A

- EDAR

- EDA receptor

- GPI

- glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- En

- embryonic day n

- Pn

- postnatal day n.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huelsken J., Vogel R., Erdmann B., Cotsarelis G., Birchmeier W. (2001) β-Catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell 105, 533–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mou C., Jackson B., Schneider P., Overbeek P. A., Headon D. J. (2006) Generation of the primary hair follicle pattern. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9075–9080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Y., Tomann P., Andl T., Gallant N. M., Huelsken J., Jerchow B., Birchmeier W., Paus R., Piccolo S., Mikkola M. L., Morrisey E. E., Overbeek P. A., Scheidereit C., Millar S. E., Schmidt-Ullrich R. (2009) Reciprocal requirements for EDA/EDAR/NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in hair follicle induction. Dev. Cell 17, 49–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmidt-Ullrich R., Tobin D. J., Lenhard D., Schneider P., Paus R., Scheidereit C. (2006) NF-κB transmits Eda A1/EdaR signalling to activate Shh and cyclin D1 expression, and controls post-initiation hair placode down growth. Development 133, 1045–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pummila M., Fliniaux I., Jaatinen R., James M. J., Laurikkala J., Schneider P., Thesleff I., Mikkola M. L. (2007) Ectodysplasin has a dual role in ectodermal organogenesis. Inhibition of Bmp activity and induction of Shh expression. Development 134, 117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pispa J., Jung H. S., Jernvall J., Kettunen P., Mustonen T., Tabata M. J., Kere J., Thesleff I. (1999) Cusp patterning defect in Tabby mouse teeth and its partial rescue by FGF. Dev. Biol. 216, 521–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tucker A. S., Headon D. J., Schneider P., Ferguson B. M., Overbeek P., Tschopp J., Sharpe P. T. (2000) Edar/Eda interactions regulate enamel knot formation in tooth morphogenesis. Development 127, 4691–4700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hammerschmidt B., Schlake T. (2007) Localization of Shh expression by Wnt and Eda affects axial polarity and shape of hairs. Dev. Biol. 305, 246–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cui C. Y., Durmowicz M., Ottolenghi C., Hashimoto T., Griggs B., Srivastava A. K., Schlessinger D. (2003) Inducible mEDA-A1 transgene mediates sebaceous gland hyperplasia and differential formation of two types of mouse hair follicles. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2931–2940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fessing M. Y., Sharova T. Y., Sharov A. A., Atoyan R., Botchkarev V. A. (2006) Involvement of the Edar signaling in the control of hair follicle involution (catagen). Am. J. Pathol. 169, 2075–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kere J., Srivastava A. K., Montonen O., Zonana J., Thomas N., Ferguson B., Munoz F., Morgan D., Clarke A., Baybayan P., Chen E. Y., Ezer S., Saarialho-Kere U., de la Chapelle A., Schlessinger D. (1996) X-linked anhidrotic (hypohidrotic) ectodermal dysplasia is caused by mutation in a novel transmembrane protein. Nat. Genet. 13, 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen Y., Molloy S. S., Thomas L., Gambee J., Bächinger H. P., Ferguson B., Zonana J., Thomas G., Morris N. P. (2001) Mutations within a furin consensus sequence block proteolytic release of ectodysplasin-A and cause X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7218–7223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schneider P., Street S. L., Gaide O., Hertig S., Tardivel A., Tschopp J., Runkel L., Alevizopoulos K., Ferguson B. M., Zonana J. (2001) Mutations leading to X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia affect three major functional domains in the tumor necrosis factor family member ectodysplasin-A. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18819–18827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swee L. K., Ingold-Salamin K., Tardivel A., Willen L., Gaide O., Favre M., Demotz S., Mikkola M., Schneider P. (2009) Biological activity of ectodysplasin A is conditioned by its collagen and heparan sulfate proteoglycan-binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 27567–27576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakata M., Koshiba H., Eto K., Nance W. E. (1980) A genetic study of anodontia in X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 908–919 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pinheiro M., Freire-Maia N. (1979) Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome. A clinical and genetic analysis of a large Brazilian kindred. I. Affected females. Am. J. Med. Genet. 4, 113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zankl A., Addor M. C., Cousin P., Gaide A. C., Gudinchet F., Schorderet D. F. (2001) Fatal outcome in a female monozygotic twin with X-linked hypohydrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED) due to a de novo t(X;9) translocation with probable disruption of the EDA gene. Eur. J. Pediatr. 160, 296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mues G., Tardivel A., Willen L., Kapadia H., Seaman R., Frazier-Bowers S., Schneider P., D'Souza R. N. (2010) Functional analysis of ectodysplasin-A mutations causing selective tooth agenesis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yan M., Wang L. C., Hymowitz S. G., Schilbach S., Lee J., Goddard A., de Vos A. M., Gao W. Q., Dixit V. M. (2000) Two-amino acid molecular switch in an epithelial morphogen that regulates binding to two distinct receptors. Science 290, 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Headon D. J., Emmal S. A., Ferguson B. M., Tucker A. S., Justice M. J., Sharpe P. T., Zonana J., Overbeek P. A. (2001) Gene defect in ectodermal dysplasia implicates a death domain adapter in development. Nature 414, 913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Headon D. J., Overbeek P. A. (1999) Involvement of a novel Tnf receptor homologue in hair follicle induction [see comments]. Nat. Genet. 22, 370–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Monreal A. W., Zonana J., Ferguson B. (1998) Identification of a new splice form of the EDA1 gene permits detection of nearly all X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 380–389; Correction (1998) Am. J. Hum. Genet.63, 1253–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Newton K., French D. M., Yan M., Frantz G. D., Dixit V. M. (2004) Myodegeneration in EDA-A2 transgenic mice is prevented by XEDAR deficiency. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1608–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Srivastava A. K., Pispa J., Hartung A. J., Du Y., Ezer S., Jenks T., Shimada T., Pekkanen M., Mikkola M. L., Ko M. S., Thesleff I., Kere J., Schlessinger D. (1997) The Tabby phenotype is caused by mutation in a mouse homologue of the EDA gene that reveals novel mouse and human exons and encodes a protein (ectodysplasin-A) with collagenous domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13069–13074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pispa J., Pummila M., Barker P. A., Thesleff I., Mikkola M. L. (2008) Edar and Troy signalling pathways act redundantly to regulate initiation of hair follicle development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 3380–3391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hashimoto T., Schlessinger D., Cui C. Y. (2008) Troy binding to lymphotoxin-α activates NF κB mediated transcription. Cell Cycle 7, 106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bossen C., Ingold K., Tardivel A., Bodmer J. L., Gaide O., Hertig S., Ambrose C., Tschopp J., Schneider P. (2006) Interactions of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptor family members in the mouse and human. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13964–13971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Colosimo P. F., Hosemann K. E., Balabhadra S., Villarreal G., Jr., Dickson M., Grimwood J., Schmutz J., Myers R. M., Schluter D., Kingsley D. M. (2005) Widespread parallel evolution in sticklebacks by repeated fixation of Ectodysplasin alleles. Science 307, 1928–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schneider P. (2000) Production of recombinant TRAIL and TRAIL receptor:Fc chimeric proteins. Methods Enzymol. 322, 325–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kowalczyk C., Dunkel N., Willen L., Casal M. L., Mauldin E. A., Gaide O., Tardivel A., Badic G., Etter A. L., Favre M., Jefferson D. M., Headon D. J., Demotz S., Schneider P. (2011) Molecular and therapeutic characterization of anti-ectodysplasin A receptor (EDAR) agonist monoclonal antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 30769–30779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morrison S. L. (2002) Cloning, expression, and modification of antibody V regions. Current Protocols in Immunology, 47, 2.12.1–2.12.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Z., Raifu M., Howard M., Smith L., Hansen D., Goldsby R., Ratner D. (2000) Universal PCR amplification of mouse immunoglobulin gene variable regions. The design of degenerate primers and an assessment of the effect of DNA polymerase 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity. J. Immunol. Methods 233, 167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schneider P., Holler N., Bodmer J. L., Hahne M., Frei K., Fontana A., Tschopp J. (1998) Conversion of membrane-bound Fas(CD95) ligand to its soluble form is associated with downregulation of its proapoptotic activity and loss of liver toxicity. J. Exp. Med. 187, 1205–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gaide O., Schneider P. (2003) Permanent correction of an inherited ectodermal dysplasia with recombinant EDA. Nat. Med. 9, 614–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rawlins E. L., Hogan B. L. (2005) Intercellular growth factor signaling and the development of mouse tracheal submucosal glands. Dev. Dyn. 233, 1378–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ferguson B. M., Brockdorff N., Formstone E., Ngyuen T., Kronmiller J. E., Zonana J. (1997) Cloning of Tabby, the murine homolog of the human EDA gene. Evidence for a membrane-associated protein with a short collagenous domain. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 1589–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Casal M. L., Lewis J. R., Mauldin E. A., Tardivel A., Ingold K., Favre M., Paradies F., Demotz S., Gaide O., Schneider P. (2007) Significant correction of disease after postnatal administration of recombinant ectodysplasin a in canine x-linked ectodermal dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 1050–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hymowitz S. G., Compaan D. M., Yan M., Wallweber H. J., Dixit V. M., Starovasnik M. A., de Vos A. M. (2003) The crystal structures of EDA-A1 and EDA-A2. Splice variants with distinct receptor specificity. Structure 11, 1513–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Houghton L., Lindon C., Morgan B. A. (2005) The ectodysplasin pathway in feather tract development. Development 132, 863–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Houghton L., Lindon C. M., Freeman A., Morgan B. A. (2007) Abortive placode formation in the feather tract of the scaleless chicken embryo. Dev. Dyn. 236, 3020–3030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pantalacci S., Chaumot A., Benoît G., Sadier A., Delsuc F., Douzery E. J., Laudet V. (2008) Conserved features and evolutionary shifts of the EDA signaling pathway involved in vertebrate skin appendage development. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 912–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kraehenbuhl J. P., Campiche M. A. (1969) Early stages of intestinal absorption of specific antibiodies in the newborn. An ultrastructural, cytochemical, and immunological study in the pig, rat, and rabbit. J. Cell Biol. 42, 345–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Israel E. J., Taylor S., Wu Z., Mizoguchi E., Blumberg R. S., Bhan A., Simister N. E. (1997) Expression of the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, on human intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology 92, 69–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Heath J., Langton A. K., Hammond N. L., Overbeek P. A., Dixon M. J., Headon D. J. (2009) Hair follicles are required for optimal growth during lateral skin expansion. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 2358–2364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hill N. L., Laib A., Duncan M. K. (2002) Mutation of the ectodysplasin-A gene results in bone defects in mice. J. Comp. Pathol. 126, 220–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]