Abstract

Purkinje cells receive both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs and send sole output from the cerebellar cortex. Long-term depression (LTD), a type of synaptic plasticity, at excitatory parallel fiber–Purkinje cell synapses has been studied extensively as a primary cellular mechanism of motor learning. On the other hand, at inhibitory synapses on a Purkinje cell, postsynaptic depolarization induces long-lasting potentiation of GABAergic synaptic transmission. This synaptic plasticity is called rebound potentiation (RP), and its molecular regulatory mechanisms have been studied. The increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration caused by depolarization induces RP through enhancement of GABAA receptor (GABAAR) responsiveness. RP induction depends on binding of GABAAR with GABAAR associated protein (GABARAP) which is regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII). Whether RP is induced or not is determined by the balance between phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation activities regulated by intracellular Ca2+ and by metabotropic GABA and glutamate receptors. Recent studies have revealed that the subunit composition of CaMKII has significant impact on RP induction. A Purkinje cell expresses both α- and β-CaMKII, and the latter has much higher affinity for Ca2+/calmodulin than the former. It was shown that when the relative amount of α- to β-CaMKII is large, RP induction is suppressed. The functional significance of RP has also been studied using transgenic mice in which a peptide inhibiting association of GABARAP and GABAAR is expressed selectively in Purkinje cells. The transgenic mice show abrogation of RP and subnormal adaptation of vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), a type of motor learning. Thus, RP is involved in a certain type of motor learning.

Keywords: cerebellum, Purkinje cell, synaptic plasticity, rebound potentiation, long-term potentiation, motor learning, inhibitory synapse, GABA

Introduction

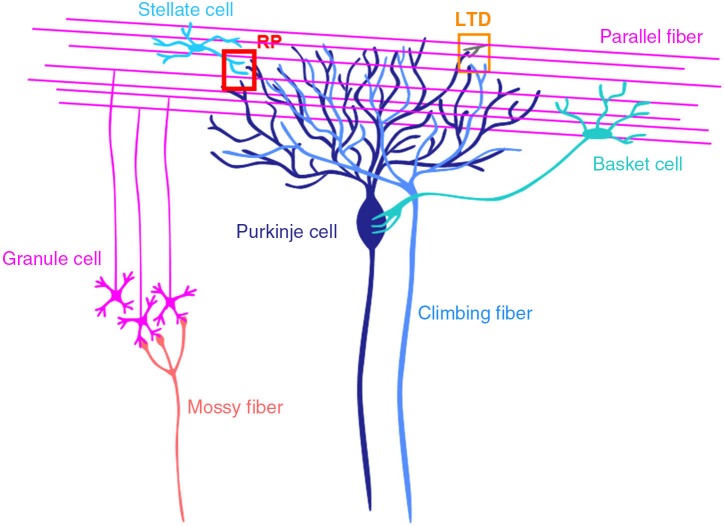

The cerebellum consists of cortex and nuclei, and is involved in motor control (Figure 1; Ito, 1984, 2011; Llinás et al., 2004). There are two major inputs to the cerebellum, mossy fibers and climbing fibers. Mossy fibers coming from pons, medulla oblongata etc., innervate neurons in cerebellar nuclei and granule cells in the granular layer of cortex. Granule cells extend axons to the molecular layer, where they bifurcate. The bifurcated granule cell axons are called parallel fibers, and form excitatory glutamatergic synapses on dendrites of Purkinje cells and inhibitory GABAergic interneurons in the molecular layer, stellate and basket cells. Climbing fibers coming from inferior olivary nuclei innervate neurons in cerebellar nuclei and Purkinje cells. A single climbing fiber forms hundreds synapses on a Purkinje cell, and thus sends a powerful excitatory drive. Purkinje cells are GABAergic neuron, and send sole output from the cortex to nuclear neurons.

Figure 1.

Cerebellar cortical neuronal circuits. Mossy fibers from pontine nuclei etc., send excitatory synaptic outputs to granule cells. A granule cell forms one or a few excitatory glutamatergic synapses on a Purkinje cell, where LTD occurs depending on the activity of the granule cell and a climbing fiber. Molecular layer interneurons (stellate and basket cells) receive excitatory synaptic inputs from granule cells and inhibit Purkinje cells. At inhibitory GABAergic synapses between a stellate cell and a Purkinje cell, rebound potentiation (RP) is induced by climbing fiber activity.

Climbing fibers are thought to code error signals (Maekawa and Simpson, 1973), and regulate activities of Purkinje cells. Activation of parallel fibers followed by activation of a climbing fiber depresses the efficacy of synaptic transmission between the activated parallel fibers and a Purkinje cell long-term. This synaptic plasticity is called long-term depression (LTD), and has been considered to be a cellular basis of motor learning such as adaptation of reflex eye movements and classical conditioning of eye blink response (Ito, 1982, 2011; du Lac et al., 1995; Thompson, 2005; Hirano, 2013a). However, mice defective in LTD were shown to display normal motor learning (Welsh et al., 2005; Schonewille et al., 2011), and the involvement of other plasticity mechanisms in motor learning has been suggested (Hansel et al., 2001; Jörntell and Hansel, 2006; Dean et al., 2010; Jörntell et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2012; Hirano, 2013a).

Plasticity also takes place at synapses other than parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses in the cerebellum such as excitatory synapses on granule cells, those between parallel fibers and inhibitory interneuron and those in the nuclei (Jörntell and Ekerot, 2002, 2003; D’Angelo et al., 2005; Pugh and Raman, 2006). At GABAergic synapses formed by stellate cells on Purkinje cells, three types of plasticity induced by postsynaptic depolarization have been reported (Figure 2), namely, depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI), depolarization-induced potentiation of inhibition (DPI) and rebound potentiation (RP) (Hirano, 2013b). DSI is short-lasting suppression of presynaptic GABA release mediated by endocannabinoid, which is released from a Purkinje cell and binds to presynaptic cannabinoid receptor (Llano et al., 1991; Yoshida et al., 2002). DPI is longer-lasting potentiation of presynaptic GABA release mediated by glutamate, which is released from a postsynaptic Purkinje cell and binds to presynaptic NMDA receptors (Duguid and Smart, 2004). RP occurs postsynaptically and lasts longer (Kano et al., 1992; Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2000; Tanaka et al., 2013). In RP, postsynaptic responsiveness to GABA is enhanced. These plasticity mechanisms are triggered by the postsynaptic Purkinje cell depolarization and subsequent intracellular Ca2+ increase (Figure 2). Thus, they are hetero-synaptic plasticity induced by excitatory inputs. In this article, molecular regulatory mechanisms of RP induction and functional roles of RP are reviewed.

Figure 2.

Three forms of synaptic plasticity at stellate cell—Purkinje cell synapses. Time courses (left) and induction mechanisms (right) of DSI, DPI and RP are presented. In DSI the Ca2+ increase caused by postsynaptic depolarization produces diacylglycerol (DG), which is broken down to 2-arachidonylglycerol (2AG). 2AG reaches the presynaptic terminal and activates cannabinoid receptor 1 (CBR) on the cell membrane, which suppresses presynaptic vesicular release of GABA. In DPI, the intracellular Ca2+ increase causes postsynaptic release of glutamate, which activates presynaptic NMDA receptor (NMDAR) potentiating presynaptic GABA release. In RP, the postsynaptic Ca2+ increase potentiates postsynaptic GABAAR responsiveness.

Mechanism of rebound potentiation (RP) induction

RP is induced by activation of a climbing fiber or direct depolarization of a postsynaptic Purkinje cell that causes large increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i (Kano et al., 1992; Miyakawa et al., 1992). Stimulation of a climbing fiber five times at 0.5 Hz induces RP in juvenile cerebellar slice preparations (Kano et al., 1992). However, in that study an intracellular solution containing high concentration of Cs+ was used, and subsequent studies used direct depolarization of a Purkinje cell (Kano et al., 1992; Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2000, 2002, 2007; Kitagawa et al., 2009; Tanaka et al., 2013). Thus, patterns of climbing fiber activity sufficient to induce RP in vivo remain unclear. The time integral of [Ca2+]i is correlated with the induction of RP, and RP is induced in an all-or-none fashion with a certain threshold (Kitagawa et al., 2009; Kawaguchi et al., 2011). RP has been monitored with the amplitude of inhibitory postsynaptic current or that of Cl− current induced by GABA applied to dendrites, and it has been shown that RP is expressed as enhanced postsynaptic responsiveness to GABA (Kano et al., 1992; Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2000, 2002, 2007). Stellate cells form inhibitory synapses on dendrites, whereas basket cells form them on the soma of a Purkinje cell. RP has been studied primarily at stellate cell—Purkinje cell synapses in dendrites. Whether RP occurs similarly at basket cell—Purkinje cell synapses is unclear. It was difficult to record RP when GABA was applied to a soma (our unpublished observation). However, this difficulty might have been ascribed to washout of intracellular molecules necessary for RP induction caused inadvertently by the whole-cell recording conditions.

Increased intracellular Ca2+ binds to calmodulin, which in turn binds to Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII). CaMKII activity is necessary for RP induction (Kano et al., 1996; Kitagawa et al., 2009). CaMKII is known to phosphorylate many proteins including GABAAR β and γ2 subunits (Moss and Smart, 1996; Brandon et al., 2002; Houston et al., 2009). Purkinje cells express α1, β2, β3 and γ2 subunits which form a heteropentameric GABAAR, and β2 is more abundant than β3 (Laurie et al., 1992; Wisden et al., 1996; Pirker et al., 2000; Hirano, 2013b). Houston et al. (2008) reported the CaMKII mediated increase in IPSC amplitudes in cerebellar granule cells expressing GABAAR containing β2 subunit. Thus, direct phosphorylation of β2 subunit of GABAAR by CaMKII could be involved in RP. However, it was also reported that CaMKII potentiates α1β3γ2 GABAAR but not α1β2γ2 receptor in undifferentiated NG108-15 neuroblastoma cells (Houston and Smart, 2006), suggesting that the potentiation of β2 subunit-containing GABAAR by CaMKII may not work in some conditions or in certain cells (Houston et al., 2009). Thus, roles of direct phosphorylation of GABAAR by CaMKII in RP remain enigmatic.

Another target molecule of CaMKII in RP induction is GABAAR associated protein (GABARAP). GABARAP has a binding site for GABAAR γ2 subunit (Wang et al., 1999). RP induction is impaired by competitive inhibition of association between GABARAP and GABAAR γ2 subunit with a peptide (γ2 peptide) corresponding to the intracellular region of γ2 subunit that mediates the binding to GABARAP (Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2007). Application of this peptide after establishment of RP also attenuates once-established RP, suggesting that the interaction of GABARAP and γ2 subunit is required not only for induction of RP but also for its maintenance. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) imaging experiments showed that GABARAP undergoes a sustained structural change in response to depolarization of a Purkinje cell (Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2007). This conformational change of GABARAP depends on activity of CaMKII. Further, single amino acid replacement of GABARAP V33E blocks structural change of GABARAP and suppresses RP induction. Thus, CaMKII-mediated conformational change of GABARAP seems to be essential for RP. GABARAP is involved in intracellular trafficking and targeting of GABAAR to the cell membrane (Kneussel et al., 2000; Kittler et al., 2001; Moss and Smart, 2001; Kneussel, 2002; Nymann-Andersen et al., 2002; Leil et al., 2004; Lüscher and Keller, 2004; Chen and Olsen, 2007; Kanematsu et al., 2007). Thus, GABARAP might induce RP through facilitating GABAAR transport to the cell membrane. In hippocampal neurons, inhibitory synaptic potentiation is induced by activation of NMDA-type glutamate receptors through GABARAP-dependent exocytosis of GABAAR (Marsden et al., 2007). Another possible role of GABARAP in RP is to enhance the function of individual GABAAR by increasing the single channel conductance or the open time (Everitt et al., 2004; Luu et al., 2006). GABARAP is also known to bind to tubulin, and it has been suggested that association of GABARAP with tubulin is required for RP induction (Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2007).

Mechanism of rebound potentiation (RP) suppression

RP is induced by cell-wide depolarization of a Purkinje cell caused by hetero-synaptic excitatory climbing fiber inputs (Kano et al., 1992). Thus, RP should occur at many inhibitory synapses on a Purkinje cell simultaneously, and should not be synapse-specific. However, there is a synapse-specific regulatory mechanism for RP induction. GABAergic synaptic transmission or GABAB receptor activation during the postsynaptic depolarization suppresses RP (Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2000). This regulation is unique in that homo-synaptic activity suppresses induction of synaptic plasticity. Usually, homo-synaptic activity triggers the plasticity of transmission.

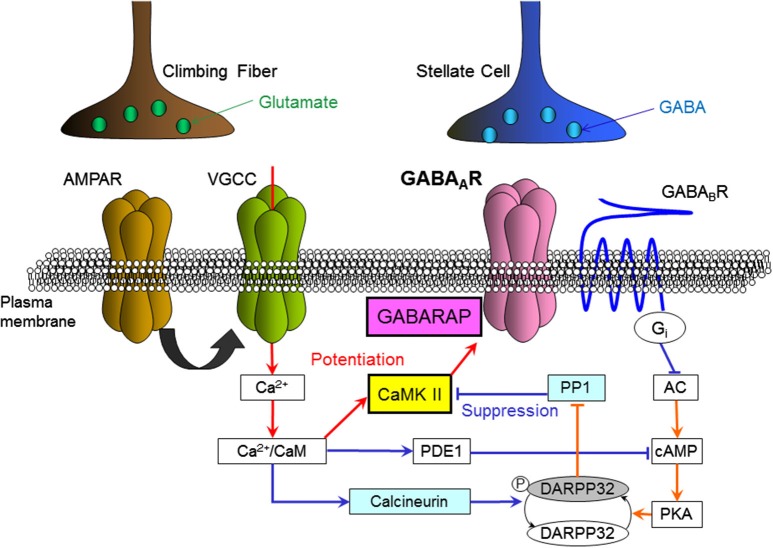

This GABAB receptor-dependent suppression of synaptic plasticity is mediated by down-regulation of the activity of protein kinase A (PKA). It was revealed that down-regulation of PKA activity decreases the amount of phosphorylated dopamine- and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-regulated phospho-protein 32 kDa (DARPP-32; Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2002; Figure 3). Phosphorylated DARPP-32 is known to inhibit protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), which de-phosphorylates CaMKII and other phosphorylated proteins (Greengard et al., 1999). Thus, GABAB receptor activation works to enhance PP1 activity counteracting CaMKII. It was also shown that a Ca2+-dependent phosphatase calcineurin de-phosphorylates DARPP-32 upon a [Ca2+]i increase and supports suppression of RP (Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2002). A later study showed that the basal PKA activity in a Purkinje cell is partly supported by the activity of metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR1 (Sugiyama et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Intracellular molecular signaling cascades regulating RP. Arrows indicate an increase, activation or enhancement, and T-bars indicate a decrease or suppression. Red lines indicate signal transmissions which work to induce RP, and blue lines indicate those work to suppress RP. AMPAR, AMPA-type glutamate receptor; VGCC, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel; GABAAR, GABAA receptor; GABABR, GABAB receptor; CaM, calmodulin; CaMKII, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II; GABARAP, GABAAR associated protein; PDE1, phosphodiesterase 1, PP1, protein phosphatase 1; DARPP32, dopamine and cAMP-regulated phospho-protein 32 kDa; PKA, protein kinase A; cAMP, cyclic-adenosine-monophosphate; AC, adenylyl cyclase; Gi, Gi protein.

Signaling cascade regulating rebound potentiation (RP)

The preceding sections have introduced molecules involved in regulation of RP. Among them CaMKII is a key molecule for RP induction. There are two subtypes of CaMKII, α and β, and the relative expression level of β-CaMKII to α-CaMKII is higher in the cerebellum than in the forebrain (McGuinness et al., 1985; Walaas et al., 1988). In the cerebellar cortex β-CaMKII is expressed in several types of cells including Purkinje cells, whereas α-CaMKII is expressed only in Purkinje cells. It has been reported that the relative amounts of α- and β-CaMKII change depending on the neuronal activity and developmental stage in the mammalian central nervous system (Bayer et al., 1999; Thiagarajan et al., 2002). β-CaMKII has much higher affinity to Ca2+/calmodulin than α-CaMKII (Brocke et al., 1999). In addition β-CaMKII binds to actin but α-CaMKII does not (Okamoto et al., 2009). Thus, subtypes of CaMKII may have different roles in a Purkinje cell. Recently, we addressed this point by overexpressing or knocking-down each type of CaMKII, and found that the subunit composition of CaMKII has a significant impact on RP induction (Nagasaki et al., 2012). Suppression of the expression of β-CaMKII but not that of α-CaMKII inhibits RP induction, whereas overexpression of α-CaMKII but not that of β-CaMKII inhibits the induction. Thus, the relative amount of β- to α-CaMKII seems to be critical for RP induction.

Interactions among molecules regulating RP including CaMKII are complex, as there are multiple branchings and feedback loops in the signaling cascades (Figure 3). Thus, it is difficult to intuitively predict how they behave quantitatively. To address this question, a theoretical model of molecular signaling networks for RP regulation has been built and computational simulation has been performed (Kitagawa et al., 2009; Kawaguchi et al., 2011). During this process phosphodiesterase 1 (PDE1), a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzyme that breaks down cAMP, was added as a critical element. The simulation reproduced essential features of induction and suppression of RP, and suggested that PDE1 plays a predominant role in determination of the Ca2+ threshold for RP induction (Kitagawa et al., 2009). Regulation of RP induction by a cell adhesion molecule integrin was also reported (Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2006).

Ca2+ context regulates rebound potentiation (RP)

RP induction depends on leaky integration of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (Kawaguchi et al., 2011) as induction of LTD at glutamatergic parallel fiber—Purkinje cell synapses does (Tanaka et al., 2007). However, it is not just integration of the Ca2+ signal that is critical for RP induction. We found that the context or order of the Ca2+ signal affects RP induction (Kawaguchi et al., 2011). Either a large and short increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, or a small and long one can induce RP by itself. However, when a large and short increase is followed by a small and long increase, RP is not induced. In contrast, when the order is reversed, RP is induced. Thus, RP induction depends on the context or the time course of intracellular Ca2+ change. It was suggested that this interesting context-dependence of RP induction on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration is brought about by context-dependent autophosphorylation at Thr305/306 of CaMKII, which negatively regulates the subsequent Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent activation of CaMKII (Figure 3).

Involvement of rebound potentiation (RP) in motor learning

Until recently there was no experimental evidence about roles of RP in cerebellar functions. We thought that RP might work together with LTD for establishment of motor learning, because activation of an inferior olivary neuron contributes to induction of both LTD and RP (Kano et al., 1992; Ito, 2011; Hirano, 2013a), and also because both down-regulation of excitatory synaptic inputs by LTD and up-regulation of inhibitory synaptic inputs by RP should work to suppress activity of a Purkinje cell. To test this idea, we generated transgenic mice defective in RP (Tanaka et al., 2013). As explained above, binding of GABAAR and an intracellular protein GABARAP is necessary for RP induction, and γ2 peptide which blocks this binding suppresses the induction. Transgenic mice which express γ2 peptide fused to a fluorescent protein only in Purkinje cells were generated. The transgenic mice do not show RP as we expected, and other physiological and morphological properties of the cerebellum including LTD induction appear normal.

Then, we evaluated the motor control and learning ability of the transgenic mice by examining reflex eye movement, vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR; Figure 4). VOR is a reflex to turn an eyeball in the opposite direction of head turn, and works to stabilize visual image during head motion (Robinson, 1981). VOR undergoes adaptive modification in the direction to reduce image slip on a retina, which has been regarded as a model paradigm of cerebellum-dependent motor learning (Ito, 1982, 2011; Nagao, 1989; Lisberger et al., 1994; du Lac et al., 1995; Hirata and Highstein, 2001; Katoh et al., 2005; Hirano, 2013a). In experiments, a mouse is rotated sinusoidally on a rotating table, and a surrounding external screen with vertical black and white stripes is also rotated simultaneously (Tanaka et al., 2013). When the screen rotation is in the opposite direction to mouse rotation, the gain of VOR increases gradually in a wild-type mouse, and when the rotation is in the same direction, the gain decreases. These changes of VOR in a wild-type mouse are in the direction to reduce image motion on a retina and adaptive (Figure 4). These adaptive modifications of VOR amplitudes are suppressed in the transgenic mice defective in RP. Thus, transgenic mice defective in RP show defects in a type of motor learning, indicating that RP contributes to motor learning. However, it should be noted that these results do not rule out a possible contribution of LTD or other plasticity to motor learning. Indeed, adaptation of optokinetic response, another type of reflex eye movement, and reduced VOR adaptation occur in the RP-deficient mice (Tanaka et al., 2013). Considering similarities in induction conditions (Kawaguchi and Hirano, 2013) and suppressive effects on Purkinje cell activity between RP and LTD, they might synergistically support motor learning.

Figure 4.

Vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) and its adaptation. VOR is induced by rotating a turntable on which a mouse is fixed in the dark. In VOR eyeballs turn in the opposite direction of head turn. VOR undergoes adaptive modifications. When a wild-type mouse and a surrounding screen with vertical black and white stripes are rotated in opposite directions in the light (VOR-up training), the gain of VOR increases gradually. In contrast, when the rotations are in the same direction (VOR-down training), the gain decreases.

Conclusion

Postsynaptic depolarization of a cerebellar Purkinje cell induces long-term potentiation (LTP) of GABAergic inhibitory synaptic transmission which is called RP. Induction of RP depends on Ca2+, CaMKII, GABARAP etc., and intricate regulatory mechanisms have been delineated. Transgenic mice defective in RP show defects in adaptation of VOR, indicating involvement of RP in motor learning.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Tagawa, H. Tanaka and E. Nakajima for their constructive comments on the manuscript and Ms. Y. Tanaka for preparation of figures.

References

- Bayer K.-U., Löhler J., Schulman H., Harbers K. (1999). Developmental expression of the CaM kinase II isoforms: ubiquitous γ- and δ-CaM kinase II are the early isoforms and most abundant in the developing nervous system. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 70, 147–154 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00131-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon N. J., Jovanovic J. N., Smart T. G., Moss S. J. (2002). Receptor for activated C kinase-1 facilitates protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation and functional modulation of GABAA receptors with the activation of G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Neurosci. 22, 6353–6361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocke L., Chiang L. W., Wagner P. D., Schulman H. (1999). Functional implications of the subunit composition of neuronal CaM kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22713–22722 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Olsen R. W. (2007). GABAA receptor associated proteins: a key factor regulating GABAA receptor function. J. Neurochem. 100, 279–294 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo E., Rossi P., Gall D., Prestori F., Nieus T., Maffei A., et al. (2005). Long-term potentiation of synaptic transmission at the mossy fiber-granule cell relay of cerebellum. Prog. Brain Res. 148, 69–80 10.1016/s0079-6123(04)48007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P., Porrill J., Ekerot C. F., Jörntell H. (2010). The cerebellar microcircuit as an adaptive filter: experimental and computational evidence. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 30–43 10.1038/nrn2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Lac S., Raymond J. L., Sejnowski T. J., Lisberger S. G. (1995). Learning and memory in the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 409–441 10.1146/annurev.neuro.18.1.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid I. C., Smart T. G. (2004). Retrograde activation of presynaptic NMDA receptors enhances GABA release at cerebellar interneuron-Purkinje cell synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 525–533 10.1038/nn1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt A. B., Luu T., Cromer B., Tierney M. L., Birnir B., Olsen R. W., et al. (2004). Conductance of recombinant GABAA channels is increased in cells co-expressing GABAA receptor-associated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21701–21706 10.1074/jbc.m312806200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., van Beugen B. J., De Zeeuw C. I. (2012). Distributed synergistic plasticity and cerebellar learning. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 619–635 10.1038/nrn3312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P., Allen P. B., Nairn A. C. (1999). Beyond the dopamine receptor: the DARPP-32/protein phosphatase-1 cascade. Neuron 23, 435–447 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80798-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel C., Linden D. J., D’Angelo E. (2001). Beyond parallel fiber LTD: the diversity of synaptic and non-synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 467–475 10.1038/87419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. (2013a). Long-term depression and other synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 89, 183–195 10.2183/pjab.89.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. (2013b). “GABA and synaptic transmission in the cerebellum,” in Handbook of the Cerebellum and Cerebellar Disorders, eds Manto M., Schmahmann J. D., Rossi F., Gruol D. L., Koibuchi N. (Heidelberg: Springer; ), 881–893 [Google Scholar]

- Hirata Y., Highstein S. (2001). Acute adaptation of the vestibuloocular reflex: signal processing by floccular and ventral parafloccular Purkinje cells. J. Neurophysiol. 85, 2267–2288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston C. M., He Q., Smart T. G. (2009). CaMKII phosphorylation of the GABAA receptor: receptor subtype- and synapse-specific modulation. J. Physiol. 587, 2115–2125 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston C. M., Hosie A. M., Smart T. G. (2008). Distinct regulation of β2 and β3 subunit-containing cerebellar synaptic GABAA receptors by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Neurosci. 28, 7574–7584 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5531-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston C. M., Smart T. G. (2006). CaMK-II modulation of GABAA receptors expressed in HEK293, NG108–15 and rat cerebellar granule neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 2504–2514 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. (1982). Cerebellar control of the vestibulo-ocular reflex—around the flocculus hypothesis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 275–296 10.1146/annurev.ne.05.030182.001423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. (1984). The Cerebellum and Neural Control. New York: Raven [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. (2011). The Cerebellum: Brain for an Implicit Self. New Jersey: FT Press [Google Scholar]

- Jörntell H., Bengstsson F., Schonewille M., De Zeeuw C. I. (2010). Cerebellar molecular layer interneurons – computational properties and roles in learning. Trends Neurosci. 33, 524–532 10.1016/j.tins.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörntell H., Ekerot C. F. (2002). Reciprocal bidirectional plasticity of parallel fiber receptive fields in cerebellar Purkinje cells and their afferent interneurons. Neuron 34, 797–806 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00713-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörntell H., Ekerot C. F. (2003). Receptive field plasticity profoundly alters the cutaneous parallel fiber synaptic input to cerebellar interneurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 23, 9620–9631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörntell H., Hansel C. (2006). Synaptic memories upside down: bidirectional plasticity at cerebellar parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Neuron 52, 227–238 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanematsu T., Mizokami A., Watanabe K., Hirata M. (2007). Regulation of GABAA-receptor surface expression with special reference to the involvement of GABARAP (GABAA receptor-associated protein) and PRIP (phospholipase C-related, but catalytically inactive protein). J. Pharmacol. Sci. 104, 285–292 10.1254/jphs.CP0070063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M., Kano M., Fukunaga K., Konnerth A. (1996). Ca2+-induced rebound potentiation of γ-aminobutyric acid-mediated currents requires activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 93, 13351–13356 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M., Rexhausen U., Dreessen J., Konnerth A. (1992). Synaptic excitation produces a long-lasting rebound potentiation of inhibitory synaptic signals in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Nature 356, 601–604 10.1038/356601a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh A., Yoshida T., Himeshima Y., Mishina M., Hirano T. (2005). Defective control and adaptation of reflex eye movements in mutant mice deficient in either the glutamate receptor δ2 subunit or Purkinje cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21, 1315–1326 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S., Hirano T. (2000). Suppression of inhibitory synaptic potentiation by presynaptic activity through postsynaptic GABAB receptors in a Purkinje neuron. Neuron 27, 339–347 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00041-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S., Hirano T. (2002). Signaling cascade regulating long-term potentiation of GABAA receptor responsiveness in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J. Neurosci. 22, 3969–3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S., Hirano T. (2006). Integrin α3β1 suppresses long-term potentiation at inhibitory synapses on the cerebellar Purkinje neuron. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 31, 416–426 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S., Hirano T. (2007). Sustained structural change of GABAA receptor-associated protein underlies long-term potentiation at inhibitory synapses on a cerebellar Purkinje neuron. J. Neurosci. 27, 6788–6799 10.1523/jneurosci.1981-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S., Hirano T. (2013). Gating of long-term depression by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II through enhanced cGMP signalling in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J. Physiol. 591, 1707–1730 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.245787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S., Nagasaki N., Hirano T. (2011). Dynamic impact of temporal context of Ca2+ signals on inhibitory synaptic plasticity. Sci. Rep. 1:143 10.1038/srep00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa Y., Hirano T., Kawaguchi S. (2009). Prediction and validation of a mechanism to control the threshold for inhibitory synaptic plasticity. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5:280 10.1038/msb.2009.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler J. T., Rostaing P., Schiavo G., Fritschy J. M., Olsen R., Triller A., et al. (2001). The subcellular distribution of GABARAP and its ability to interact with NSF suggest a role for this protein in the intracellular transport of GABAA receptors. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 18, 13–25 10.1006/mcne.2001.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneussel M. (2002). Dynamic regulation of GABAA receptors at synaptic sites. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 39, 74–83 10.1016/S0165-0173(02)00159-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneussel M., Haverkamp S., Fuhrmann J. C., Wang H., Wassle H., Olsen R. W., et al. (2000). The γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABAAR)- associated protein GABARAP interacts with gephyrin but is not involved in receptor anchoring at the synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 97, 8594–8599 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie D. J., Wisden W., Seeburg P. H. (1992). The distribution of thirteen GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J. Neurosci. 12, 4151–4172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leil T. A., Chen Z. W., Chang C. S., Olsen R. W. (2004). GABAA receptor- associated protein traffics GABAA receptors to the plasma membrane in neurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 11429–11438 10.1523/jneurosci.3355-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisberger S. G., Pavelko T. A., Bronte-Stewart H. M., Stone L. S. (1994). Neural basis for motor learning in the vestibuloocular reflex of primates. II. Changes in the responses of horizontal gaze velocity Purkinje cells in the cerebellar flocculus and ventral paraflocculus. J. Neurophysiol. 72, 954–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I., Leresche N., Marty A. (1991). Calcium entry increases the sensitivity of cerebellar Purkinje cells to applied GABA and decreases inhibitory synaptic currents. Neuron 6, 565–574 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R. R., Walton K. D., Lang E. J. (2004). “Cerebellum,” in The Synaptic Organization of the Brain , ed Shepherd G. M. (New York: Oxford University Press; ), 271–309 [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher B., Keller C. A. (2004). Regulation of GABAA receptor trafficking, channel activity and functional plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Pharmacol. Ther. 102, 195–221 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu T., Gage P. W., Tierney M. L. (2006). GABA increases both the conductance and mean open time of recombinant GABAA channels co-expressed with GABARAP. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35699–35708 10.1074/jbc.m605590200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa K., Simpson J. I. (1973). Climbing fiber responses evoked in vestibulocerebellum of rabbit from visual pathway. J. Neurophysiol. 36, 649–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden K. C., Beattie J. B., Friedenthal J., Carroll R. C. (2007). NMDA receptor activation potentiates inhibitory transmission through GABA receptor-associated protein-dependent exocytosis of GABAA receptors. J. Neurosci. 27, 14326–14337 10.1523/jneurosci.4433-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness T. L., Lai Y., Greengard P. (1985). Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Isozymic forms from rat forebrain and cerebellum. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 1696–1704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa H., Lev-Ram V., Lasser-Ross N., Ross W. N. (1992). Calcium transients evoked by climbing fiber and parallel fiber synaptic inputs in guinea pig cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 68, 1178–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss S. J., Smart T. G. (1996). Modulation of amino acid-gated ion channels by protein phosphorylation. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 39, 1–52 10.1016/S0074-7742(08)60662-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss S. J., Smart T. G. (2001). Constructing inhibitory synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 240–250 10.1038/35067500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao S. (1989). Behavior of floccular Purkinje cells correlated with adaptation of vestibulo-ocular reflex in pigmented rabbits. Exp. Brain Res. 77, 531–540 10.1007/bf00249606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki N., Hirano T., Kawaguchi S. (2012). “Critical role of CaMKII subunit composition in Ca2+ threshold for inhibitory synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum,” Abstract in the 35th Annual Meeting of Japan Neuroscience Society. (Tokyo: Japan Neuroscience Society; ), P4–a37 [Google Scholar]

- Nymann-Andersen J., Wang H., Chen L., Kittler J. T., Moss S. J., Olsen R. W. (2002). Subunit specificity and interaction domain between GABAA receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) and GABAA receptors. J. Neurochem. 80, 815–823 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K., Bosch M., Hayashi Y. (2009). The roles of CaMKII and F-actin in the structural plasticity of dendritic spines: a potential molecular identity of a synaptic tag? Physiology (Bethesda) 24, 357–366 10.1152/physiol.00029.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirker S., Schwarzer C., Wieselthaler A., Sieghart W., Sperk G. (2000). GABAA receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience 101, 815–850 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh J., Raman I. (2006). Potentiation of mossy fiber EPSCs in the cerebellar nuclei by NMDA receptor activation followed by postinhibitory rebound current. Neuron 51, 113–123 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. A. (1981). The use of control systems analysis in the neurophysiology of eye movements. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 463–503 10.1146/annurev.ne.04.030181.002335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonewille M., Gao Z., Boele H. J., Veloz M. F., Amerika W. E., Simek A. A., et al. (2011). Reevaluating the role of LTD in cerebellar motor learning. Neuron 70, 43–50 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama Y., Kawaguchi S., Hirano T. (2008). mGluR1-mediated facilitation of long-term potentiation at inhibitory synapses on a cerebellar Purkinje neuron. Eur. J. Neurosci. 27, 884–896 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Khiroug L., Santamaria F., Doi T., Ogasawara H., Ellis-Davies G., et al. (2007). Ca2+ requirements for cerebellar long-term synaptic depression: role for a postsynaptic leaky integrator. Neuron 54, 787–800 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S., Kawaguchi S., Shioi G., Hirano T. (2013). Long-term potentiation of inhibitory synaptic transmission onto cerebellar Purkinje neurons contributes to adaptation of vestibulo-ocular reflex. J. Neurosci. 33, 17209–17220 10.1523/jneurosci.0793-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan T. C., Piedras-Renteria E. S., Tsien R. W. (2002). α- and βCaMKII: inverse regulation by neuronal activity and opposing effects on synaptic strength. Neuron 36, 1103–1114 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. F. (2005). In search of memory traces. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 1–23 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walaas S. I., Lai Y., Gorelick F. S., DeCamilli P., Moretti M., Greengard P. (1988). Cell-specific localization of the α-subunit of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in Purkinje cells in rodent cerebellum. Brain Res. 4, 233–242 10.1016/0169-328x(88)90029-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Bedford F. K., Brandon N. J., Moss S. J., Olsen R. W. (1999). GABAA-receptor-associated protein links GABAA receptors and the cytoskeleton. Nature 397, 69–72 10.1038/16264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh J. P., Yamaguchi H., Zeng X. H., Kojo M., Nakada Y., Takagi A., et al. (2005). Normal motor learning during pharmacological prevention of Purkinje cell long-term depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 102, 17166–17171 10.1073/pnas.0508191102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W., Korpi E. R., Bahn S. (1996). The cerebellum: a model system for studying GABAA receptor diversity. Neuropharmacology 35, 1139–1160 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00076-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T., Hashimoto K., Zimmer A., Maejima T., Araishi K., Kano M. (2002). The cannabinoid CB1 receptor mediates retrograde signals for depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J. Neurosci. 22, 1690–1697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]