Abstract

Egg activation is the final transition that an oocyte goes through to become a developmentally competent egg. This transition is usually triggered by a calcium-based signal that is often, but not always, initiated by fertilization. Activation encompasses a number of changes within the egg. These include changes to the egg's membranes and outer coverings to prevent polyspermy and support the developing embryo, as well as resumption and completion of the meiotic cell cycle, mRNA poly-adenylation, translation of new proteins, and the degradation of specific maternal mRNAs and proteins. The transition from an arrested, highly differentiated cell, the oocyte, to a developmentally active, totipotent cell, the activated egg or embryo, represents a complete change in cellular state. This is accomplished by altering ion concentrations and widespread changes in both the proteome and the suite of mRNAS present in the cell. Here, we review the role of calcium and zinc in the events of egg activation, and the importance of macromolecular changes during this transition. The latter include the degradation and translation of proteins, protein post-translational regulation through phosphorylation, and the cytoplasmic polyadenylation, or the degradation, of maternal mRNAs.

Keywords: oocyte-to-embryo transition, calcium, phosphorylation, proteome, maternal mRNAs and proteins, fertilization

Introduction

At the end of oogenesis, mature oocytes are held in a developmentally-quiescent, arrested state until an appropriate trigger initiates development. In these specialized cells, the cell cycle is paused and maternally provided mRNAs and proteins are stored until their time to function. If development is to be successful, the oocyte must undergo one final transition from this steady state to a new cellular state that can support embryogenesis. This transition is referred to as “egg activation”. Without this step of oocyte development, fertilization cannot lead to the creation of an embryo.

The events of egg activation include cortical granule exocytosis (in many taxa) and the block to polyspermy, translation of new proteins, decreases in Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) activity, and resumption of the cell cycle through inactivation of Maturation Promoting Factor (MPF; composed of Cdc2 kinase and cyclin B) and activation of the Anaphase Promoting Complex (APC/c). Without these changes the egg cannot limit fertilization to a single sperm, nor direct events of development such as mitosis and embryonic patterning. Egg activation as a whole process, as well as specific events such as meiotic cell cycle regulation, have been well reviewed elsewhere (Tsaadon et al., 2006; Horner and Wolfner; 2008b; Li et al., 2010; Marcello and Singson, 2010; Gadella and Evans, 2011; Liu, 2011). Here we present egg activation as it relates to a complete cellular/molecular transition through the regulation of ion concentrations, the suite of mRNAs present within the cell, and the composition of the proteome.

Understanding how an oocyte becomes developmentally competent through egg activation is an important aspect of diagnosis and treatment of female infertility, especially as the field continues to work towards improved assisted reproductive technologies. In addition, egg activation provides a unique model system to study the transition from a differentiated cell to a totipotent cell. In some ways, egg activation can be viewed as the converse of the change that the daughter cell of a stem cell undergoes when it differentiates, and is similar in concept to the cellular change required to form induced pluripotent cells. Upon fertilization, the highly differentiated oocyte suddenly becomes a one-cell embryo, which will give rise to all the varied cells, tissues, and organs of a complete multicellular organism. This transition represents a large and rapid change in cellular state and requires a number of molecular changes that must be both highly regulated and properly coordinated.

Ion Levels

Calcium

While the specific trigger of egg activation varies between organisms – from fertilization in vertebrates, to mechanical stimulation in some insects, to changes in pH or ionic environment for some marine invertebrates (reviewed in Horner and Wolfner, 2008b) – a rise in intracellular calcium appears to be the nearly universal signal that sets off the events of egg activation. As the regulation and role of this calcium signal has been extensively reviewed (Parrington et al., 2007; Horner and Wolfner, 2008b; Wakai et al., 2011; Nomikos et al., 2012), we will describe it only briefly here.

In vertebrates, fertilization leads to a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ in the egg which is responsible for initiating all of the events of egg activation (Horner and Wolfner, 2008b; Wakai et al., 2011). In mammals, this Ca2+ rise is mediated by a sperm-specific phospholipase C (PLCζ) (Saunders et al., 2002; reviewed in Wakai et al., 2011 and Nomikos et al., 2012). When a sperm enters the egg, PLCζ hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacyl glycerol (DAG). IP3 then binds its receptor (IP3R1), which results in the release of Ca2+ from internal stores in the endoplasmic reticulum and an overall rise in cytosolic Ca2+ in the egg (Wakai et al., 2011). A recent report also showed that Ca2+-influx is necessary for complete egg activation in the mouse, suggesting greater complexity to the regulation of the Ca2+ signal than previously presumed (Miao et al., 2012).

In some organisms, Ca2+ levels in the egg continue to rise and fall in an oscillatory pattern following fertilization. In mammals, these oscillations last for several hours (Stricker, 1999). The importance of the oscillatory nature of the Ca2+ signal is still a matter of discussion, though a couple of theories have been proposed (reviewed in Wakai et al., 2011). Ducibella et al. (2002) showed that, in mouse, different egg activation events are sensitive to different numbers of calcium oscillations. For instance, a single Ca2+ pulse is enough to initiate cortical granule exocytosis, while resumption of the cell cycle requires at least 4 Ca2+ pulses (Ducibella et al., 2002). In addition, the number of Ca2+ pulses required for completion of egg activation events is greater than the number required to initiate those events; 8 Ca2+ pulses is not enough for polar body formation even though exit from metaphase arrest had been initiated (Ducibella et al., 2002). However, other evidence suggests that the Ca2+ oscillations are not strictly required for proper egg activation. A single large Ca2+ rise induced by ethanol can generate an equal number of embryos with a polar body as Ca2+ oscillations induced by Sr2+ (when observed six hours after exposure) and produces an equivalent percentage of embryos that develop full term (Rogers et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2010b). This has led to the proposal that it is the overall magnitude of the Ca2+ increase produced by the oscillations, rather than the actual oscillatory nature of the Ca2+ rise, that is necessary for the events of egg activation to occur (Ducibella et al., 2006; Ozil et al., 2006).

The mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation at egg activation are less characterized in non-mammalian systems, though Ca2+ signaling itself appears to be a relatively conserved feature of the oocyte-to-embryo transition. A sperm PLC has not yet been identified outside of mammals, though a different PLC (PLCγ), along with Src-family kinases, has been implicated in the activation of the phosphoinositide pathway during fertilization in Xenopus (reviewed in Sato et al., 2006). In C. elegans, a single Ca2+ increase has been observed at the time of fertilization, but how this Ca2+ signal relates to the events of egg activation, or if it is dependent on a sperm-derived factor, is not yet known (Samuel et al., 2001). Supporting the idea that the Ca2+ rise seen in C. elegans plays a role analogous to that seen in other species, knocking out a C. elegans IP3 receptor, itr-1, results in sterility, suggesting that the Ca2+ rise is necessary for development (Dal Santo P et al., 1999; Samuel et al., 2001). A single Ca2+ rise also occurs in zebrafish during egg activation (Lee et al., 1999). Here, the Ca2+ rise is dependent on the RNA-binding protein brom bones, which acts upstream of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release (Mei et al., 2009). In Drosophila, in vitro experiments show that removal of Ca2+ from the buffer, through the use of the calcium chelators BAPTA or EGTA, prevents egg activation from occurring (Horner and Wolfner, 2008a). Gadolinium, which inhibits calcium influx into the cell, also prevents egg activation in this system (Horner and Wolfner, 2008a). Thus, like other species, Drosophila requires Ca2+ for egg activation and some, or all, of the Ca2+ must come from the external environment.

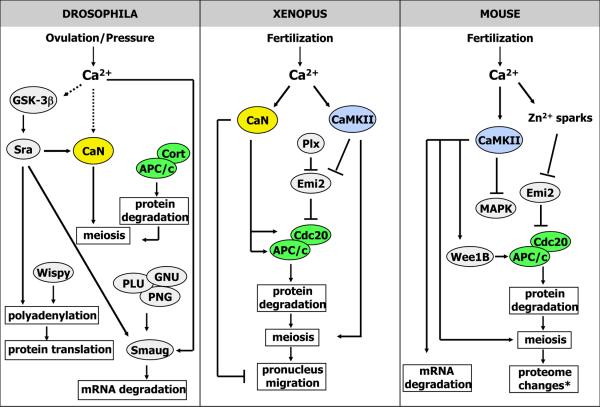

A number of questions still remain regarding how well the mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation are conserved between invertebrates and mammals, and between species with sperm-dependent versus sperm-independent triggers of egg activation. What is clear is that for a complete cellular transition, where coordination of all the changes is key, all of the events are initiated by a single signal. An increase of cytosolic Ca2+ is typically the signal that triggers egg activation, after which individual events then appear to be carried out by various Ca2+-binding/Ca2+-dependent proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of known egg activation pathways in Drosophila, Xenopus, and mouse. See text for references.

*Knott et al. (2006) and Backs et al. (2010) show that the protein patterns observed by 2D- and 1D-gel electrophoresis in activated eggs are regulated by CaMKII and attribute these changes to maternal mRNA recruitment and protein synthesis. However, it can not be ruled out that some of the observed changes are due to post-translational modifications. As such, we have placed “proteome changes” in the pathway to encompass both of these possibilities.

Zinc

While a role for Ca2+ has long been established in egg activation, the regulation of Zn2+ levels during mammalian fertilization has gained attention in recent years. In contrast to Ca2+, where increasing levels are required to activate egg activation pathways, Zn2+ levels decrease at egg activation. Upon fertilization or parthenogenetic activation in mouse, zinc is rapidly released from the egg in 1–5 exocytosis events termed “zinc sparks” (Kim et al., 2011). Zinc sparks are also observed in the two non-human primate species that have been tested (Kim et al., 2011). Each zinc spark is immediately preceded by a Ca2+ rise and none occur when Ca2+ rises are blocked by the calcium chelator BAPTA (Kim et al., 2011). This suggests that the release of Zn2+ may be dependent on the Ca2+ signal. If Zn2+ is artificially reduced in the mature oocyte by the zinc chelator TPEN, MAPK kinase activity decreases, cyclin B is degraded, and meiotic arrest is released (Suzuki et al., 2010b; Kim et al., 2011). These events occur in the absence of a Ca2+ increase in the oocyte and are unaffected by the addition of BAPTA, once again suggesting that the decrease of Zn2+ levels is downstream of the Ca2+ signal (Suzuki et al., 2010b). Zn2+ sequestration by TPEN appears to be sufficient to induce all the events of egg activation, as eggs fertilized with heat-inactivated sperm heads (that cannot produce a Ca2+ signal), and then activated with TPEN, are able to fully develop into viable mice (Suzuki et al., 2010b). Additionally, when zinc levels are increased with the zinc ionophore, ZnPT, mouse oocytes can no longer be parthenogenetically activated with SrCl2 (Bernhardt et al., 2012). Thus, release of zinc is not only sufficient, but also necessary for the events of egg activation

Precisely how Zn2+ release triggers exit from meiotic arrest has not yet been worked out. TPEN-induced resumption of the cell cycle is dependent on the APC/c activator Cdc20, suggesting that it requires APC/c activity (Suzuki et al., 2010b). However, TPEN does not induce degradation of the APC/c inhibitor Emi2 (Suzuki et al., 2010b). The Emi2 protein is required to maintain the metaphase II arrest in mature mouse oocytes by inhibiting the APC/c; Emi2 is typically degraded at egg activation to allow cell cycle progression (discussed below; Schmidt et al., 2005; Shoji et al., 2006). The fact that chelation of Zn2+ can induce resumption of the cell cycle without degradation of Emi2, along with the fact that Emi2 contains a putative zinc-binding region, has led to the model that zinc binding may directly modulate the activity of Emi2 (Bernhardt et al., 2012). This model is supported by the finding that a single mutation in the zinc-binding region of Emi2 completely inhibits its function (Schmidt et al., 2005). In addition, Zn2+ has been shown to affect the activity of the phosphatase Cdc25 and thus its ability to dephosphorylate Cdc2 (also known as Cdk1) (Sun et al., 2007). Therefore, it is possible that decreases in Zn2+ levels also contribute to progression of the cell cycle by reducing the efficiency of Cdc25 and allowing Cdc2 to become phosphorylated and inhibited. Further work is required to determine if these models are correct and to identify whether additional proteins are modulated by Zn2+ levels in the oocyte.

Changes in Proteome Composition

Large-scale changes in the egg's proteome take place at egg activation that drastically alter the cellular properties from those of the mature oocyte. Because there is little or no transcription associated with the oocyte-to-embryo transition, changes in protein composition within the cell rely on post-transcriptional and post-translational methods of regulation. Studies have been undertaken to characterize the proteome of oocytes and/or embryos in multiple organisms including mouse, frog, sea urchin, and Drosophila and provide an overview of the dynamic changes that occur during egg activation. In the mouse, over 3500 proteins have been identified in metaphase II oocytes and approximately 2000 have been found in zygotes (Pfeiffer et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010; reviewed in Yurttas et al., 2010). This discrepancy in the number of proteins identified between oocytes and zygotes is suggestive of significant degradation of maternal proteins (Wang et al., 2010). A functional role for this degradation is seen in sea urchins, where inhibition of the proteasome blocks proper entry into the first mitosis following fertilization (Kawahara et al., 2000). In agreement with this result, 2-dimensional gel analysis of unfertilized and fertilized sea urchin eggs shows a 23% decrease in the number of detectable spots 2 minutes post-fertilization (Roux et al., 2006). This is likely due to a combination of protein degradation as well as post-translational modifications as the same study showed that approximately 30% of the proteins in unfertilized eggs are phosphorylated (Roux et al., 2006). It is the overall combination of degradation and post-translation modification of existing maternal proteins, and new protein translation from maternal mRNAs, that transitions an oocyte into an embryo.

Protein degradation

As mentioned above, substantial protein degradation is observed upon egg activation. One important role for this degradation is the regulation of the meiotic cell cycle by the APC/c, an E3 ubiquitin-ligase that targets proteins for degradation by the 26S proteosome (reviewed in McLean et al., 2011). Targets of the APC/c include securin and cyclins, which hold the mature oocyte in metaphase arrest until egg activation. As there are several recent reviews on the function and regulation of the APC/c (Pensin and Orr-Weaver, 2008; Verlhac et al., 2010; McLean et al., 2011), we will only mention the key points here.

The APC/c is regulated by the adaptor protein Cdc20, which acts as an activator of the APC/c and confers substrate specificity. While the role of Cdc20 in mitosis is well studied, its role in meiosis remains more elusive (reviewed in Pesin and Orr-Weaver, 2008). However, in Drosophila, a meiosis-specific Cdc20, Cortex, has been identified that is required for cyclin degradation and completion of meiosis during egg activation (Page and Orr-Weaver, 1996; Chu et al., 2006; Pesin and Orr-Weaver, 2007; Swan and Schupbach, 2007). Cortex is also responsible for regulating its own degradation by the APC/c following egg activation, presumably to allow the canonical Cdc20 (Fizzy) to regulate the subsequent embryonic mitoses (Pesin and Orr-Weaver, 2007). Continuing studies in Drosophila will provide a unique model system for understanding how Cdc20 is regulated to activate the metaphase-to-anaphase transition during egg activation.

In Xenopus and mice, a novel mechanism for regulating the APC/c during egg activation was found through the identification of Emi2/XErp1 as a necessary protein for maintaining metaphase arrest (Schmidt et al., 2005; Shoji et al., 2006). Emi2 inhibits the APC/c in metaphase-arrested oocytes/egg extracts, evidenced by the fact that removal of Emi2 results in precocious metaphase exit, while overexpression of Emi2 prevents APC/c activation upon addition of SrCl2 or Ca2+ (Schmidt et al., 2005; Shoji et al., 2006). Upon egg activation in Xenopus, Emi2 protein is degraded by the Skp1-Cullin F-box (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex, showing that at least one other degradation pathway besides the APC/c is active during egg activation (Schmidt et al., 2005). This degradation is believed to be dependent on phosphorylation by Polo-like kinase 1 (Plx1). Two Plx1 phosphorylation sites are present within the DSGX3S motif required for Emi2 degradation, and mutation of either of these sites reduces Emi2 degradation in vivo and Plx1 phosphorylation of Emi2 in vitro (Schmidt et al., 2005). While Emi2 is also degraded upon egg activation in the mouse, a similar mechanism of phosphorylation by Plx1, and degradation by the SCF, has not been demonstrated (Shoji et al., 2006). In addition, though Emi2 clearly inhibits the APC/c, the exact mechanism of this inhibition is not yet known. Emi2 has been proposed to interact with, and inhibit, both Cdc20 and the core APC/c (Shoji et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2007). Finally, it is possible that once activated, the APC/c can contribute to the inactivation of Emi2. Studies in Xenopus show that overexpression of the APC/c-cooperating E2 enzyme leads to the ubiquitylation of Emi2 and its disassociation from the APC/c (Hormanseder et al., 2011). Although the APC/c clearly plays a critical role in protein degradation during egg activation, it is not known to what extent other pathways contribute to the global degradation that is observed. In Xenopus, action of the SCF is implicated by its role in Emi2 degradation, but whether it has any additional targets at this time remains to be investigated. Additionally, autophagy [a bulk degradation system of the cell (reviewed in Mizushima, 2007)] is highly induced in early mouse embryos and is required for preimplantation development (Tsukamoto et al., 2008a; Tsukamoto et al., 2008b). A full understanding of the role of protein degradation, and the ways in which individual pathways regulate unique or overlapping sets of targets, will require a more complete characterization of the proteome after egg activation and how inhibition of each pathway affects global changes in protein composition in the egg.

Protein phosphorylation

Multiple types of post-translational modification are likely to act on the proteome during egg activation. For instance, maternal sumoylation is important for eggshell patterning and mitosis during Drosophila embryogenesis (Nie et al., 2009). However, the main focus thus far has been on the role of phosphorylation, and that is where we will also focus in this review. In sea urchins, fertilization causes the number of phosphorylated proteins to double within 2 minutes, before returning to pre-fertilization levels 30 minutes later (Roux et al., 2006). In Xenopus, phosphoproteomic analysis has identified a combined total of 654 phosphoproteins in oocytes, unfertilized eggs, and embryos (McGivern et al., 2009). And in Drosophila, we have identified 311 proteins that change in phosphorylation state between mature oocytes and unfertilized, activated eggs (Krauchunas et al., submitted).

Phosphorylation can be a major contributor to a change in cellular state since it has the ability to rapidly modulate a large number of proteins and has a wide array of regulatory affects [ie. altering protein activity (Cargnello and Roux, 2011) or localization (Jans and Hubner, 1996)]. The importance of phosphorylation during egg activation is evidenced by the dynamic phosphorylation changes that take place during the oocyte-to-embryo transition, and the finding that phosphorylation modulators such as CaMKII and calcineurin (discussed below) are critical for successful egg activation.

CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a serine/threonine protein kinase that is regulated by calcium and the calcium receptor molecule calmodulin (reviewed in Hudmon and Schulman, 2002). Because of the relationship between Ca2+ and CaMKII, and the importance of Ca2+ to initiate egg activation, CaMKII has been proposed to be one of the main effectors of the Ca2+ signal at egg activation. Numerous studies support this hypothesis, pointing primarily to a key role for CaMKII in the resumption of the cell cycle.

An increase in CaMKII activity occurs at the time of fertilization/egg activation that correlates with the observed increase in Ca2+ levels in both Xenopus and mouse. In Xenopus, where one Ca2+ spike occurs, CaMKII activity transiently spikes in the first 5 minutes after calcium addition (Liu and Maller, 2005; Nishiyama et al., 2007). In mice, the activity of CaMKII is oscillatory, once again correlating with the pattern of Ca2+ rises in the egg (Johnson et al., 1998; Tatone et al., 2002; Markoulaki et al., 2003; Markoulaki et al., 2004). When Ca2+ oscillations are produced by fertilization, or artificially induced, CaMKII activity is seen to peak at the time of Ca2+ peaks followed by a return to baseline activity levels; these increases in kinase activity can be observed for up to one hour post-insemination (Markoulaki et al., 2003; Markoulaki et al., 2004). In contrast, if mouse oocytes are activated by ethanol, which produces only a single Ca2+ rise, CaMKII activity increases only once, showing that the oscillations of CaMKII activity are dependent on the oscillations of Ca2+ levels in the egg (Tatone et al., 2002). When CaMKII is inhibited in Xenopus or mouse oocytes, cyclin B fails to be degraded, Cdc2 remains active, and the cell cycle remains arrested in metaphase (Lorca et al., 1993; Morin et al., 1994; Johnson et al., 1998; Tatone et al., 1999; Markoulaki et al., 2003; Madgwick et al., 2005). If a constitutively active form of CaMKII is added to the oocyte, cyclin B degradation is induced, Cdc2 and MAPK levels decrease, and meiosis resumes (Lorca et al., 1993; Morin et al., 1994; Madgwick et al., 2005; Knott et al., 2006).

CaMKII exists in four different isoforms - α, β, δ, γ. In mouse oocytes, two splice forms of CaMKIIγ are predominantly expressed, while the other isoforms are present at low or undetectable levels (Backs et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2009; Suzuki et al., 2010a). In CaMKIIγ conditional knockout mice, or when CaMKIIγ is knocked down by an antisense morpholino, eggs remain arrested in metaphase and MAPK and Cdc2 kinase levels remain high (Backs et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2009). Injection of CaMKII cDNA rescues this phenotype. Rescue is not isoform-specific, suggesting that it is the general activity of CaMKII that is required for meiotic resumption rather than any CaMKIIγ-specific targets (Backs et al., 2010). In addition, characteristic proteome changes that occur at egg activation, observed by either 2D- or 1D-gel electrophoresis, are not seen in the CaMKIIγ mutants (Backs et al., 2010), though they can be triggered by addition of constitutively active CaMKII (Knott et al., 2006). However, these proteome changes can also be induced by a Ca2+ signal and direct inactivation of Cdc2 kinase, even when CaMKII is not present (Backs et al., 2010). Thus, these observed changes in proteome composition appear to rely on resumption of the cell cycle but are only indirectly regulated by CaMKII.

Two mechanisms for how CaMKII initiates the metaphase to anaphase transition have been elucidated in Xenopus. The first comes from the finding that CaMKII is both necessary and sufficient for Emi2 degradation in Xenopus egg extracts (Rauh et al., 2005; Hansen et al., 2006). As mentioned earlier, in Xenopus, Polo-like kinase 1 (Plx1) phosphorylates Emi2 to target it for degradation (Schmidt et al., 2005). Removing Plx1 prevents release from the metaphase arrest, even when constitutively active CaMKII is added (Lui and Maller, 2005). CaMKII is equally required for Plx1 to induce resumption of the cell cycle (Lui and Maller, 2005). Additionally, while expression of either CaMKII or Plx1 alone cannot overcome the arrest caused by Emi2 overexpression, a combination of both kinases can (Lui and Maller, 2005). This suggests that the kinases work together to regulate Emi2 degradation and the subsequent exit from meiotic arrest. In vitro experiments show that Emi2 is a good substrate for CaMKII and that Emi2 interacts with, and is phosphorylated by, Plx1 in a CaMKII-dependent manner (Lui and Maller, 2005; Rauh et al., 2005; Hansen et al., 2006). Thus, the current model is that when CaMKII is activated by the Ca2+ rise at egg activation it phosphorylates Emi2, which primes Emi2 for subsequent phosphorylation by Plx1, eventually leading to its degradation (Lui and Maller, 2005; Rauh et al., 2005; Hansen et al., 2006). CaMKII also promotes microtubule destabilization at the onset of anaphase (Reber et al., 2008). This function is independent of APC/c activation, suggesting that CaMKII works at multiple levels to regulate progression of the cell cycle at egg activation.

Whether a similar mechanism for the role of CaMKII in Emi2 degradation or microtubule destabilization exists in mammals has not yet been established. However, in mouse, the kinase Wee1B has been shown to be a CaMKII target at egg activation. Knockdown of Wee1B in oocytes prevents parthenogenetically activated eggs from exiting metaphase due to a failure to completely activate the APC/c and high levels of MAPK (Oh et al., 2010). In addition, Wee1B knockdown reduces the ability of constitutively active CaMKII to induce polar body formation (Oh et al., 2010). In vitro experiments show that Wee1B can be phosphorylated by CaMKII, and that this phosphorylation increases Wee1B activity (Oh et al., 2010). Thus, in mouse, it has been shown that CaMKII regulates resumption of the cell cycle through phosphorylation of Wee1B, which in turn phosphorylates and inhibits Cdc2, leading to the inhibition of MPF activity and the transition from metaphase to anaphase.

Calcineurin

Calcineurin is a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase composed of a catalytic A subunit (CnA) and regulatory B subunit (Rusnak and Mertz, 2000). A role for calcineurin at egg activation was first suggested by studies in Drosophila which showed that the calcineurin regulator, Sarah (Sra), is necessary for multiple aspects of egg activation (Horner et al., 2006; Takeo et al., 2006). Eggs laid by sra mutant females have defects in the polyadenylation and translation of maternal mRNAs and defects in protein degradation (Horner et al., 2006). In addition, while meiosis briefly resumes in eggs laid by sra mutants, it re-arrests at anaphase I, perhaps due to the high levels of cyclin B in these eggs (Horner et al., 2006; Takeo et al., 2006).

The absence of these egg activation events in eggs laid by sra mutants is presumed to be due to misregulation of calcineurin when Sra is not present. This hypothesis is supported by both genetic and biochemical assays. Three calcineurin subunits are present in Drosophila oocytes and early embryos: two A subunits (Pp2B-14D and CanA-14F) and one B subunit (CanB2) (Takeo et al., 2006). Sra has been shown to interact with all three of these subunits, both in cell culture and in vivo by mass spectrometry experiments (Takeo et al., 2006; Takeo et al., 2012). In addition, genetic interaction studies showed that the phenotype caused by expression of a dominant negative CnA is rescued by Sra overexpression and enhanced in sra heterozygotes (Takeo et al., 2010).

A direct role for calcineurin in Drosophila egg activation has been shown through germline clonal analysis of both CanB2 mutants and CnA double mutants. In both cases elimination of calcineurin function from the oocyte/embryo led to an anaphase I arrest identical to that seen in sra mutants (Takeo et al., 2010; Takeo et al., 2012). As the CnA double mutants can be rescued by expression of wild-type Pp2B-14D, but not by a phosphatase-dead version of the protein, the phosphatase activity of calcineurin is required for its role at egg activation in Drosophila (Takeo et al., 2012). What remains to be determined is whether the defect in polyadenylation and translation seen in sra mutants also occurs in calcineurin mutants, or if sra has additional functions beyond the regulation of calcineurin. If calcineurin is indeed necessary for these events, it provides a link between the Ca2+ signal and maternal mRNA translation. However, the possible calcineurin target(s) regulating this event remain unidentified.

A role for calcineurin in egg activation has also been observed in Xenopus (Mochida and Hunt, 2007; Nishiyama et al., 2007). Addition of Ca2+ to Xenopus egg extracts causes a transient increase in calcineurin activity (Mochida and Hunt, 2007; Nishiyama et al., 2007). This transient activity occurs along the same time frame as the spike in CamKII activity that is seen upon addition of calcium, and precedes the degradation of cyclin B (Nishiyama et al., 2007). When calcineurin is inhibited, Cdc2 activity remains high and eggs/extracts are not able to exit metaphase II (Nishiyama et al., 2007). Immunodepletion of calcineurin confirms these results, showing a failure to degrade both cyclin B and securin (Nishiyama et al., 2007). Similar to the results in Drosophila, adding back constitutively active calcineurin reverses this phenotype but a phosphatase-dead version of the protein does not (Nishiyama et al., 2007). Surprisingly, constitutively active calcineurin reduces the size of sperm asters formed around demembranated sperm added to Ca2+-activated Xenopus egg extracts. This is in contrast to Drosophila, where sperm asters fail to form in eggs laid by sra mutants (Horner et al., 2006). Thus, at least in Xenopus, it appears that it is important that calcineurin is activated only transiently.

The necessity of calcineurin for cyclin B degradation and metaphase II exit leads to the hypothesis that calcineurin is involved in the regulation of the APC/c. In Xenopus, it appears that calcineurin does directly regulate components of the APC/c (Mochida and Hunt, 2007). Two APC/c subunits, Apc3 (a core subunit) and Fizzy (Cdc20), are phospho-regulated during the cell cycle (Peters et al., 1996; Chung and Chen, 2003) and both proteins undergo dephosphorylation when calcium is added to egg extracts (Mochida and Hunt, 2007). However, the calcineurin inhibitor Cyclosporin A prevents this dephosphorylation from occurring (Mochida and Hunt, 2007). The ability of calcineurin to dephosphorylate immunopurified Apc3 and Fizzy suggests that these proteins are direct targets of the phosphatase (Mochida and Hunt, 2007). Whether calcineurin also contributes to the regulation of the APC/c through Emi2 is less clear. While Nishiyama et al. (2007) report that inhibiting calcineurin reduces the degradation of Emi2, Mochida and Hunt (2007) find that Emi2 dephosphorylation and degradation is unaffected in the presence of Cyclosporin A. Almost all the Ca2+ induced dephosphorylations that can be observed with an anti-(phospho-Ser-Pro) antibody are prevented by Cyclosporin A, suggesting that there are many more calcineurin targets that remain to be identified (Mochida and Hunt, 2007). However, how many of these dephosphorylations are direct targets, and how many are indirect effects due to misregulation of the APC/c, is unknown.

As with CamKII, calcineurin appears to be a key regulator activated by the Ca2+ signal that triggers egg activation. The activation of calcineurin is independent of CamKII activity, and vice versa (Nishiyama et al., 2007). However the transient activity of both proteins is required for metaphase II exit in Xenopus (Nishiyama et al., 2007). This appears to contrast with the findings that addition of constitutively active CaMKII alone can induce resumption of the cell cycle. However, in those experiments the activity of CaMKII is not transient, the way it is under fertilization or Ca2+-induced activation. When constitutively active CaMKII is inactivated 25 minutes after its addition to Xenopus egg extracts, the inactivation of Cdc2 is no longer observed unless active calcineurin is also added (Nishiyama et al., 2007). In addition, the results from Xenopus show that calcineurin activity and the appropriately timed inhibition of calcineurin are both required for successful egg activation and the initiation of embryogenesis. In Drosophila, the regulation of calcineurin itself is more complex than simply direct activation by Ca2+, as Sra is also required for calcineurin activity. Additionally, Sra itself is regulated through phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) (Takeo et al., 2012). Whether similar regulators of calcineurin are also present in Xenopus oocytes, or if GSK-3β plays a role in egg activation of other organisms remains to be tested.

At present, there is no evidence to show that calcineurin plays an analogous role in mammalian egg activation. Suzuki et al. (2010a) failed to detect the CnA subunit in mouse oocytes, and although ICSI-induced metaphase II exit was slowed by the addition of calcineurin inhibitors, it was not prevented. More experimentation is required to conclusively rule out any contributions that calcineurin may make to egg activation in mammals, including testing Cyclosporin A and other inhibitors when eggs are activated by Ca2+ (rather than ICSI), a thorough investigation into what, if any, calcineurin subunits are present in mammalian oocytes, and subsequent knockout analysis of those proteins.

Other phosphorylation regulators

While CaMKII and calcineurin have been identified as two of the most upstream regulators that transduce the Ca2+ signal and initiate multiple aspects of egg activation, other phosphorylation regulators have also been implicated in egg activation events and early embryogenesis. Polo-like kinase, GSK-3, Cdc25, and Wee1B have all been mentioned above. Pan Gu (PNG), is a serine/threonine kinase in Drosophila that complexes with two other proteins, Giant Nuclei (GNU) and Plutonium (PLU), to function in the oocyte-to-embryo transition (Lee et al., 2003). Both GNU and PLU can be phosphorylated by the PNG kinase complex in vitro and GNU is dephosphorylated upon egg activation, suggesting that function of the complex is itself phospho-regulated (Lee et al., 2003; Renault et al., 2003). However, other phosphorylation targets of PNG and the importance of GNU dephosphorylation remain to be determined.

In C. elegans, one critical phosphorylation regulator is the kinase MBK-2, which regulates maternal protein degradation during the oocyte-to-embryo transition (Pellettieri et al., 2003). MBK-2 is regulated by the pseudo-phosphatases EGG-3, EGG-4, and EGG-5 (Maruyama et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2009; Parry et al., 2009; reviewed in Parry and Singson, 2011). Some of the targets of MBK-2 have been identified, and include major regulators of the oocyte-to-embryo transition (reviewed in Marcello and Singson, 2010). At least one role of MBK-2 phosphorylation appears to be providing a priming phosphorylation for subsequent modification by an additional kinase, as MBK-2 targets have been shown to be further phosphorylated by GSK-3 and polo kinases (Nishi and Lin, 2005; Nishi et al., 2008).

Other kinases that have been implicated in the oocyte-to-embryo transition of various species include protein kinase C (PKC), myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), and MAPKs. However, in many cases the roles of these kinases at egg activation are less clear than the findings on CaMKII and calcineurin. The evidence for potential functions of these kinases as they relate to the events of egg activation are reviewed elsewhere (Ducibella and Fissore, 2008).

New Protein Translation

Some of the proteins necessary for the oocyte-to-embryo transition and early embryogenesis are not present in the mature oocyte. Instead these proteins are translated from maternal mRNAs that had been loaded into the oocyte and held in a repressed state until egg activation. Analysis of the protein classes that are required in the early embryo, as well as the function of specific proteins encoded by the maternally deposited mRNAs, will inform us of the cellular events that are critical at this time and help identify potential regulators of those processes.

One way to determine the full set of proteins that are translated in the activated egg is by analyzing the transcripts that are associated with the polysome. This analysis has been carried out in mouse oocytes and in one-cell embryos to determine which maternal mRNAs are recruited to the polysome after egg activation (Potireddy et al., 2006). Nearly 2000 individual mRNAs were found to have greater signals in the one-cell polysomal RNA population when compared to the oocyte polysomal RNA population (Potireddy et al., 2006). These RNAs were enriched for functional classes related to metabolism, transcription, and cell cycle regulation, consistent with the idea that the proteins translated from maternal mRNAs are important for early embryonic mitosis and activation of the zygotic genome (Potireddy et al., 2006).

Proteomic studies comparing mouse oocytes and zygotes also provide information on protein translation at egg activation. While the overall number of proteins identified in zygotes was lower than the number of proteins in oocytes (Wang et al., 2010), a comparison of the identities of the proteins in each sample should reveal proteins that are present only in the zygote, indicating that they are not translated until egg activation. It will also be of interest to compare the polysomal mRNA and proteomic data sets to determine how well polysomal recruitment correlates with identification of proteins in the embryo and/or the level of saturation reached by either of these screens.

In addition to determining the identities of these proteins, another important aspect of protein translation at egg activation is understanding how maternal transcripts are regulated to ensure they are translated at the appropriate time. One mechanism by which the translation of these transcripts is regulated is through polyadenylation of the 3' untranslated regions (UTR). During oocyte maturation in Xenopus, this process is regulated by opposing polymerase and deadenylase activities (Kim and Richter, 2006). The polymerase and deadenylase are both bound to the transcript through the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB) and the cleavage and specificity factor (CPSF), which recognize cis-elements in the 3' UTR (Kim and Richter, 2006). When maturation is signaled, CPEB is phosphorylated and the deadenylase subsequently disassociates from the transcript. As only the poly-A polymerase remains, the result is a lengthening of the poly-A tail. It is possible that a similar mechanism works during egg activation to regulate the polyadenylation and translation that occurs at this time.

In Drosophila, the maternal protein Wispy is a cytoplasmic poly-A polymerase that is responsible for the polyadenylation of numerous targets during both oocyte maturation and egg activation (Cui et al., 2008; Benoit et al., 2008). Targets of Wispy include Bicoid and Torso, which are important for patterning the early embryo and have been previously shown to be translated upon egg activation (Driever and Nusslein-Volhard, 1988; Casanova and Struhl, 1989). In Wispy mutants, the bicoid and torso transcripts fail to be polyadenylated in activated eggs; for bicoid this has been shown to result in a failure to translate the Bicoid protein (Cui et al., 2008; Benoit et al., 2008). However, lengthening of the poly-A tail alone is not sufficient for translation, as elongation of the bicoid poly-A tail by overexpression of a poly-A polymerase in the oocyte does not result in Bicoid protein expression in oocytes (Juge et al., 2002). Thus, it appears that protein translation at egg activation not only requires the lengthening of maternal mRNA poly-A tails, but either an additional activational pathway or the repression of an inhibitory pathway that is present in the mature oocyte.

Wispy is not necessary for all protein translation during egg activation, as translation of the Smaug protein is unaffected in wispy mutants (Cui et al., 2008; Benoit et al., 2008). Smaug is important for degradation of maternal transcripts after egg activation (discussed below) (Tadros et al., 2007). To ensure that maternal transcripts are protected from Smaug-mediated degradation prior to egg activation, Smaug protein is not present in the mature oocyte (Dahanukar et al., 1999; Smibert et al., 1999). Instead, maternal smaug mRNA is actively translated at egg activation; a process dependent on both pan gu and sra (Tadros et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2008). When pan gu is mutated smaug mRNA polyadenylation is also reduced (Tadros et al., 2007). Overexpression of a poly-A polymerase can rescue the poly-A tail phenotype of the pan gu mutant, however Smaug protein is still not translated, suggesting that Pan Gu works at multiple levels to control the translation of Smaug (Tadros et al., 2007). Pan Gu is also required for the translation of cyclin B in the early Drosophila embryo (Vardy and Orr-Weaver, 2007). In the case of cyclin B, loss of Pumilio (a translational repressor) can restore cyclin B translation in a pan gu mutant background, suggesting that at least one additional function of Pan Gu is to inhibit Pumilio (Vardy and Orr-Weaver, 2007). However, Smaug translation is not restored in pumilio; pan gu double mutants, indicating that additional mechanisms of Pan Gu translational regulation still remain to be discovered (Tadros et al., 2007).

mRNA Degradation

The mature oocyte is stocked full of maternal mRNAs that were transcribed and loaded into the oocyte during oogenesis. In Drosophila, it is estimated that up to 55% of the genes in the genome are represented in maternal transcripts in the oocyte (Tadros et al., 2007). For the transition to a totipotent cell (the embryo), the transcriptional profile of the differentiated cell (the oocyte) must be removed. Thus, while some of the maternal mRNAs are translated in the early embryo, another key facet of egg activation is the targeted degradation of other maternal mRNAs.

Maternal transcript degradation in the early embryo has been observed in a number of species including mouse, zebrafish, and Drosophila (Hamatani et al., 2004; Mathavan et al., 2005; Tadros et al., 2007; Thomsen et al., 2010). In Drosophila, egg activation is both necessary and sufficient for this maternal mRNA degradation, at least for the specific transcripts examined so far (Bashirullah et al., 1999; Tadros et al., 2003). While the mechanistic connection between the Ca2+ signal and maternal mRNA degradation remains elusive, studies in Drosophila provide some insight into the regulation of this process. Here, the maternal protein Smaug is required for two-thirds of the transcript degradation that is observed upon egg activation (Tadros et al., 2007). Studies of two known Smaug targets, nanos and Hsp83, show that Smaug acts by binding to cis-elements, known as Smaug Recognition Elements (SREs), in maternal transcripts and recruiting the CCR4/POP2/NOT-deadenylase complex (Smibert et al., 1996; Semotok et al., 2005; Semotok et al., 2008). This leads to the deadenylation of these transcripts and their subsequent degradation. In addition, it has been proposed that Smaug interacts with the piRNA pathway to promote the deadenylation and degradation of a subset of maternal transcripts (Rouget et al., 2010).

Once the zygotic genome is activated, a second wave of maternal transcript degradation is activated which relies on zygotic, as well as maternal, products (Bashirullah et al., 1999). We will not discuss this second round of degradation and instead refer you to two comprehensive reviews on the maternal and zygotic regulation of mRNA degradation during egg activation and the maternal-to-zygotic transition by Tadros and Lipshitz (2005; 2009) and the role of microRNAs in maternal transcript degradation by Giraldez (2010). These authors also discuss the possible biological consequences of maternal transcript degradation, presenting potential roles in producing localized expression of RNA and proteins or acting as a permissive phenomenon to avoid interfering with zygotic transcripts.

Summary

Egg activation represents a cellular transition from a highly differentiated oocyte into a totipotent embryo. There is a single initiating signal at the start of this transition, which ensures that all of the downstream signals and events are properly coordinated within the cell This is especially important considering each event is regulated at multiple levels. During egg activation, a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ independently activates the effector proteins CaMKII and calcineurin, and at least one other pathway, to initiate this cellular transition. [At least one other pathway must be involved as cortical granule exocytosis occurs in the absence of both calcineurin and CaMKII, and CaMKII only partially contributes to the membrane block to polyspermy (Mochida and Hunt, 2007; Nishiyama et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2009; Backs et al., 2010; Gardner et al., 2007).] These effectors then have the potential to amplify the initial signal through phosphorylation of multiple target proteins, activating multiple pathways within the cell (Figure 1).

Because the oocyte-to-embryo transition represents a complete change in cellular state, it requires global changes in the composition of both RNAs and proteins within the cell. Indeed, large-scale degradation of maternal mRNAs and proteins, translation of new proteins not present in the oocyte, and protein phosphorylation changes occur during egg activation. To fully understand how the embryo differs from the oocyte will require a complete identification of the molecules that are removed (degraded) and the molecules that take their place. In addition, a consistent trend in the literature is the proposal that finding the targets of the phosphorylation regulators CamKII and calcineurin will be critical to improving our understanding of how these molecules effect the cellular changes that encompass egg activation. Identifying the proteins that are phosphorylated/dephosphorylated during egg activation will provide new proteins and pathways to explore in connecting Ca2+ to all of the egg activation events. Xenopus is the only species in which CaMKII and calcineurin are both known to be critical for egg activation. At present there is no evidence of a role for calcineurin in mouse egg activation, or for CaMKII in Drosophila egg activation. However, the possibility that roles for both pathways are conserved has not been definitively excluded and remains an important area for future studies.

Our current knowledge of egg activation shows that overlapping regulatory mechanisms ensure these cellular changes are tightly controlled. For example, Emi2 has been shown to be regulated by phosphorylation and subsequent degradation, ubiquitination, and Zn2+ levels. Following that, Emi2 is only one regulator of the APC/c, which is also regulated by the activator protein Cdc20 and phosphorylation of other core subunits. All of this works together so that the APC/c can activate the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, while at the same time activation of Wee1B kinase phosphorylates and inhibits Cdc2 (which is necessary for the metaphase arrest). Presumably, in an activated egg, all of these regulatory mechanisms are coordinated by proteins downstream of the Ca2+ signal to ensure the efficient transition from meiotic arrest to embryonic mitosis. Understanding how these regulatory mechanisms inter-relate, or if they simply represent redundancy within the system, will be critical to our success in understanding this type of cellular transition, as well manipulating it therapeutically.

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul Wassarman for the opportunity to write this review, J. Bird, B. LaFlamme, and F. Avila for comments on the manuscript, and NIH grant R01-GM044659 (to MFW) for support.

References

- Backs J, Stein P, Backs T, Duncan FE, Grueter CE, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:81–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912658106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashirullah A, Halsell SR, Cooperstock RL, Kloc M, Karaiskakis A, et al. EMBO J. 1999;18:2610–20. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit P, Papin C, Kwak JE, Wickens M, Simonelig M. Development. 2008;135:1969–79. doi: 10.1242/dev.021444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt ML, Kong BY, Kim AM, O'Halloran TV, Woodruff TK. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:114. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.097253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargnello M, Roux PP. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:50–83. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00031-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J, Struhl G. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2025–38. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HY, Minahan K, Merriman JA, Jones KT. Development. 2009;136:4077–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.042143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng KC, Klancer R, Singson A, Seydoux G. Cell. 2009;139:560–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T, Henrion G, Haegeli V, Strickland S. Genesis. 2001;29:141–52. doi: 10.1002/gene.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E, Chen RH. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:748–53. doi: 10.1038/ncb1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Sackton KL, Horner VL, Kumar KE, Wolfner MF. Genetics. 2008;178:2017–29. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahanukar A, Walker JA, Wharton RP. Mol Cell. 1999;4:209–18. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80368-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Santo P, Logan MA, Chisholm AD, Jorgensen EM. Cell. 1999;98:757–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W, Nusslein-Volhard C. Cell. 1988;54:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducibella T, Fissore R. Dev Biol. 2008;315:257–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducibella T, Huneau D, Angelichio E, Xu Z, Schultz RM, et al. Dev Biol. 2002;250:280–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducibella T, Schultz RM, Ozil JP. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:324–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadella BM, Evans JP. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;713:65–80. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0763-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner AJ, Knott JG, Jones KT, Evans JP. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:275–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamatani T, Carter MG, Sharov AA, Ko MS. Dev Cell. 2004;6:117–31. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Tung JJ, Jackson PK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509549102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormanseder E, Tischer T, Heubes S, Stemmann O, Mayer TU. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:436–43. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner VL, Czank A, Jang JK, Singh N, Williams BC, et al. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1441–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner VL, Wolfner MF. Dev Biol. 2008;316:100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner VL, Wolfner MF. Developmental Dynamics. 2008;237:527–44. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudmon A, Schulman H. Biochem J. 2002;364:593–611. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans DA, Hubner S. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:651–85. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Bierle BM, Gallicano GI, Capco DG. Dev Biol. 1998;204:464–77. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juge F, Zaessinger S, Temme C, Wahle E, Simonelig M. EMBO J. 2002;21:6603–13. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara H, Philipova R, Yokosawa H, Patel R, Tanaka K, Whitaker M. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 15):2659–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.15.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AM, Bernhardt ML, Kong BY, Ahn RW, Vogt S, et al. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:716–23. doi: 10.1021/cb200084y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Richter JD. Mol Cell. 2006;24:173–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott JG, Gardner AJ, Madgwick S, Jones KT, Williams CJ, Schultz RM. Dev Biol. 2006;296:388–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauchunas AR, Horner VL, Wolfner MF. submitted.

- Lee KW, Webb SE, Miller AL. Dev Biol. 1999;214:168–80. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LA, Van Hoewyk D, Orr-Weaver TL. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2979–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.1132603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zheng P, Dean J. Development. 2010;137:859–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.039487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Maller JL. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1458–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:149. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorca T, Cruzalegui FH, Fesquet D, Cavadore JC, Mery J, et al. Nature. 1993;366:270–3. doi: 10.1038/366270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madgwick S, Levasseur M, Jones KT. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3849–59. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcello MR, Singson A. BMB Rep. 2010;43:389–99. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2010.43.6.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoulaki S, Matson S, Abbott AL, Ducibella T. Dev Biol. 2003;258:464–74. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoulaki S, Matson S, Ducibella T. Dev Biol. 2004;272:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama R, Velarde NV, Klancer R, Gordon S, Kadandale P, et al. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1555–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathavan S, Lee SG, Mak A, Miller LD, Murthy KR, et al. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:260–76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern JV, Swaney DL, Coon JJ, Sheets MD. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1433–43. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean JR, Chaix D, Ohi MD, Gould KL. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;46:118–36. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.541420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei W, Lee KW, Marlow FL, Miller AL, Mullins MC. Development. 2009;136:3007–17. doi: 10.1242/dev.037879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao YL, Stein P, Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Williams CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4169–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112333109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida S, Hunt T. Nature. 2007;449:336–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin N, Abrieu A, Lorca T, Martin F, Doree M. EMBO J. 1994;13:4343–52. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie M, Xie Y, Loo JA, Courey AJ. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Y, Lin R. Dev Biol. 2005;288:139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi Y, Rogers E, Robertson SM, Lin R. Development. 2008;135:687–97. doi: 10.1242/dev.013425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T, Yoshizaki N, Kishimoto T, Ohsumi K. Nature. 2007;449:341–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Swann K, Lai FA. Bioessays. 2012;34:126–34. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JS, Susor A, Conti M. Science. 2011;332:462–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1199211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozil JP, Banrezes B, Toth S, Pan H, Schultz RM. Dev Biol. 2006;300:534–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AW, Orr-Weaver TL. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 7):1707–15. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrington J, Davis LC, Galione A, Wessel G. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2027–38. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry JM, Singson A. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2011;53:135–51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19065-0_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry JM, Velarde NV, Lefkovith AJ, Zegarek MH, Hang JS, et al. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1752–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Reinke V, Kim SK, Seydoux G. Dev Cell. 2003;5:451–62. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesin JA, Orr-Weaver TL. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesin JA, Orr-Weaver TL. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:475–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.041408.115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, King RW, Hoog C, Kirschner MW. Science. 1996;274:1199–201. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer MJ, Siatkowski M, Paudel Y, Balbach ST, Baeumer N, et al. J Proteome Res. 2011 doi: 10.1021/pr100706k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh NR, Schmidt A, Bormann J, Nigg EA, Mayer TU. Nature. 2005;437:1048–52. doi: 10.1038/nature04093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber S, Over S, Kronja I, Gruss OJ. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:1007–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renault AD, Zhang XH, Alphey LS, Frenz LM, Glover DM, et al. Development. 2003;130:2997–3005. doi: 10.1242/dev.00501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers NT, Halet G, Piao Y, Carroll J, Ko MS, Swann K. Reproduction. 2006;132:45–57. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouget C, Papin C, Boureux A, Meunier AC, Franco B, et al. Nature. 2010;467:1128–32. doi: 10.1038/nature09465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux M, Townley I, Raisch M, Reade A, Bradham C, et al. Developmental Biology. 2006;300:416–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak F, Mertz P. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1483–521. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel AD, Murthy VN, Hengartner MO. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Fukami Y, Stith BJ. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:285–92. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders CM, Larman MG, Parrington J, Cox LJ, Royse J, et al. Development. 2002;129:3533–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Duncan PI, Rauh NR, Sauer G, Fry AM, et al. Genes Dev. 2005;19:502–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.320705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semotok JL, Cooperstock RL, Pinder BD, Vari HK, Lipshitz HD, Smibert CA. Curr Biol. 2005;15:284–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semotok JL, Luo H, Cooperstock RL, Karaiskakis A, Vari HK, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6757–72. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00037-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji S, Yoshida N, Amanai M, Ohgishi M, Fukui T, et al. EMBO J. 2006;25:834–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert CA, Lie YS, Shillinglaw W, Henzel WJ, Macdonald PM. RNA. 1999;5:1535–47. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert CA, Wilson JE, Kerr K, Macdonald PM. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2600–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stricker SA. Dev Biol. 1999;211:157–76. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Chai Y, Hannigan R, Bhogaraju VK, Machaca K. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:98–104. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Suzuki E, Yoshida N, Kubo A, Li H, et al. Development. 2010;137:3281–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.052480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Yoshida N, Suzuki E, Okuda E, Perry AC. Development. 2010;137:2659–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.049791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan A, Schupbach T. Development. 2007;134:891–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.02784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros W, Goldman AL, Babak T, Menzies F, Vardy L, et al. Dev Cell. 2007;12:143–55. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros W, Houston SA, Bashirullah A, Cooperstock RL, Semotok JL, et al. Genetics. 2003;164:989–1001. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.3.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros W, Lipshitz HD. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:593–608. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros W, Lipshitz HD. Development. 2009;136:3033–42. doi: 10.1242/dev.033183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S, Hawley RS, Aigaki T. Dev Biol. 2010;344:957–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S, Swanson SK, Nandanan K, Nakai Y, Aigaki T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6382–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120367109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S, Tsuda M, Akahori S, Matsuo T, Aigaki T. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatone C, Delle Monache S, Iorio R, Caserta D, Di Cola M, Colonna R. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:750–7. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.8.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatone C, Iorio R, Francione A, Gioia L, Colonna R. J Reprod Fertil. 1999;115:151–7. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1150151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen S, Anders S, Janga SC, Huber W, Alonso CR. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R93. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-9-r93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaadon A, Eliyahu E, Shtraizent N, Shalgi R. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;252:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto S, Kuma A, Mizushima N. Autophagy. 2008;4:1076–8. doi: 10.4161/auto.7065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto S, Kuma A, Murakami M, Kishi C, Yamamoto A, Mizushima N. Science. 2008;321:117–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1154822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardy L, Orr-Weaver TL. Dev Cell. 2007;12:157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlhac MH, Terret ME, Pintard L. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:758–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakai T, Vanderheyden V, Fissore RA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Kou Z, Jing Z, Zhang Y, Guo X, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17639–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013185107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Guo Y, Yamada A, Perry JA, Wang MZ, et al. Curr Biol. 2007;17:213–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurttas P, Morency E, Coonrod SA. Reproduction. 2010;139:809–23. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]