Abstract

Introduction

Long-term medical conditions (LTCs) cause reduced health-related quality of life and considerable health service expenditure. Writing therapy has potential to improve physical and mental health in people with LTCs, but its effectiveness is not established. This project aims to establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness of therapeutic writing in LTCs by systematic review and economic evaluation, and to evaluate context and mechanisms by which it might work, through realist synthesis.

Methods

Included are any comparative study of therapeutic writing compared with no writing, waiting list, attention control or placebo writing in patients with any diagnosed LTCs that report at least one of the following: relevant clinical outcomes; quality of life; health service use; psychological, behavioural or social functioning; adherence or adverse events. Searches will be conducted in the main medical databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, The Cochrane Library and Science Citation Index. For the realist review, further purposive and iterative searches through snowballing techniques will be undertaken. Inclusions, data extraction and quality assessment will be in duplicate with disagreements resolved through discussion. Quality assessment will include using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria. Data synthesis will be narrative and tabular with meta-analysis where appropriate. De novo economic modelling will be attempted in one clinical area if sufficient evidence is available and performed according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) reference case.

Keywords: Systematic Review, Realist Review, Public Health

Background

Therapeutic writing

Writing as a form of therapy to improve physical or mental health has a long history1 and can take many formats including those from a psychotherapeutic background such as therapeutic letter writing,2 specific controlled interventions such as emotional disclosure/expressive writing,3 to more recent approaches such as developmental creative writing4 and other epistolary approaches such as blogging.5 Other forms of potentially therapeutic writing include reflective diaries, free writing, short stories, song writing, unsent letters and memoirs. In addition, therapeutic writing interventions might be delivered in different contexts: as individual self-help therapy at home, in a healthcare centre, as part of a programme in a rehabilitation clinic or within a group of people with similar or different health conditions, in person or through the world wide web. People engaging in therapeutic writing can either receive feedback from a peer, from a healthcare professional, from their writing group or receive no feedback.6

With the development of UK organisations such as LAPIDUS (Association for Literary Arts in Personal Development) dedicated to the promotion of therapeutic writing based on the premise that it has health benefits, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of a variety of different approaches.

The most evaluated form of therapeutic writing is the expressive writing intervention as described by Pennebaker et al.3 7–9 Expressive writing is a technique whereby people are encouraged to write (or talk into a tape recorder) in private about a traumatic, stressful or upsetting event, usually from their recent or distant past. They write for 15–30 min typically for 3–4 days within a relatively short time period such as consecutive days or within 2 weeks. Participants are encouraged to write about their deepest thoughts and feelings concerning an event or experience they have not talked about with others. The control group may receive no treatment, or a written exercise with a non-emotional topic or be on a waiting list. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of expressive writing have been conducted in a wide variety of participants including healthy students, people undergoing psychological stressors, such as bereavement, or in people with long-term medical conditions (LTCs), such as rheumatoid arthritis and asthma.

Expressive writing is thought to be beneficial for longer term health effects and as such is now frequently referred to in general psychology textbooks as a potentially beneficial intervention.10 However, some have argued that this intervention is too brief to have any long lasting effects.9 11 There has been remarkably little critique published specifically on expressive writing.

Those within the field of developmental creative writing, however, consider that Pennebaker's expressive writing paradigm may be more a starting point in learning to release emotion through writing, but that added benefit may occur with more ‘free writing’ which could allow for development and shaping of the material, which leads to a ‘a new relationship with aspects of self-experience’.4 It is this connection with a core sense of self from which creative writing is said to derive benefit.4 With newer forms of writing, such as blogging, association with increased perceived social support has been demonstrated.5 Given the importance of social support to well-being, this suggests yet further mechanisms by which writing in its various formats may improve health.

It is a popular assumption that creative writing helps overcome life's stresses, and some professional writers have noted this. Notwithstanding the epistemological, methodological and ethical challenges of studying the impact of creative writing on mental health, it seems appropriate to evaluate whether the wider field of therapeutic writing might help with mental and physical LTCs.

There have been several systematic reviews and meta-analyses on emotional disclosure/expressive writing, one of which was undertaken by our own team.8 12–15 The Cochrane Library lists a protocol for evaluation of written emotional disclosure for asthma.16 Our preliminary scoping searches did not find any previous economic evaluations of any forms of therapeutic writing. None of the systematic reviews or meta-analyses incorporates a qualitative systematic review or a realist review to make sense of how and why therapeutic writing might work.

Long-term medical conditions

The prevalence of LTCs increases with ageing populations. In 2002, the leading chronic diseases (cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes) were responsible for 29 million deaths worldwide.17 According to the UK Department of Health (DoH),18 more than 15 million people in England (including half of all those aged over 60 years) are living with at least one LTC, and the risk of death is particularly high in those with three or more conditions occurring concurrently.19 LTCs also result in a huge burden on National Health Service (NHS) resources. Although some are preventable, for most LTCs continuing care is the only realistic management strategy, as biological and psychosocial mechanisms regulating disease progression are not yet fully understood. Since LTCs are difficult to improve, especially for elderly populations, healthcare programmes such as self-management support and patient education, often combined with structured clinical follow-up, have been suggested as a way to improve the quality of life of such patients.20 New therapeutic approaches may help to extend the lifespan and quality of life in people with LTCs.

Realist reviews

These reviews ask ‘what works for whom in what circumstances?’ and consider the interaction between context, mechanism and outcome (CMO), that is, how particular contexts have ‘triggered’ (or, conversely, interfered with) mechanisms to generate the observed outcomes.21 The philosophical basis is realism, which assumes the existence of an external reality (a ‘real world’) but one that is ‘filtered’ (ie, perceived, interpreted and responded to) through human senses, volitions, language and culture. Such human processing initiates a constant process of self-generated change in all social intuitions, a vital process that has to be accommodated in evaluating social programmes.

In order to understand how outcomes are generated, the roles of external reality and human understanding and response need to be incorporated. Realism does this through the concept of mechanisms, whose precise definition is contested but for which a working definition is “underlying entities, processes or structures which operate in particular contexts to generate outcomes of interest.”22 Different contexts interact with different mechanisms to make particular outcomes more or less likely—hence a realist review produces recommendations of the general format “In situations [X], complex intervention [Y], modified in this way and taking account of these contingencies, may be appropriate.” This approach, when performed well, is widely recognised as a robust methodology which is particularly appropriate when seeking to explore the interaction between CMO in a complex intervention (see eg, Berwick's editorial in JAMA explaining why experimental (RCT/meta-analysis) designs may need to be supplemented (or perhaps in some circumstances replaced) by realist studies aimed at elucidating CMO configurations (CMOCs)).23

A realist approach is particularly useful for this project because therapeutic writing is a complex intervention which could be useful in a variety of patient groups and currently it is unclear whether it is effective for all or some, and how and why it might be effective.

Objectives of the project

What are the different types of therapeutic writing that have been evaluated in comparative studies? What are their defining characteristics? How are they delivered? What underlying theories have been proposed for their effect/s?

What is the clinical effectiveness of the different types of therapeutic writing for LTCs compared with no writing or other suitable comparators?

How is heterogeneity in results of empirical studies accounted for in terms of patient and/or contextual factors, and what are the mechanisms and moderators responsible for the success, failure or partial success of interventions (ie, what works for whom in what circumstances and why)?

What is the cost-effectiveness of one or more types of therapeutic writing in one or more representative LTCs where there is sufficient information on the intervention, comparator and outcomes to conduct an economic evaluation.

Research methods

Systematic review of effectiveness and realist review

We will undertake two interlinked reviews simultaneously (see table 1 for inclusion criteria). No language restrictions will be applied.

Table 1.

Review question components

| Question components | Systematic review | |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Population | Any LTC as per DoH definition18 | Acute conditions, stress, bereavement etc |

| Exposure/intervention | Any form of therapeutic writing including emotional disclosure/expressive writing, poetry, diaries, etc | Talking to a listener, counselling, psychotherapy, talking into a tape recorder, mobile phone or similar where this is the primary mode of delivering the intervention, expressive drama, dance, film-making. Evaluation of other people's writing |

| Comparison | Non-writing, waiting list, inexpressive writing, attention controls and any control thought to be inactive | Any active or possibly active control including therapeutic writing |

| Outcome | Any relevant clinical outcomes including disease-specific outcomes and generic outcomes such as: quality of life, health service use, psychological outcomes, behavioural outcomes, social functioning, adverse events, adherence to therapies and costs | Intermediate physiological outcomes such as salivary cortisol, immune parameters not routinely measured in the management of LTCs No reporting of numerical results for each group |

| Study designs | Any comparative studies including RCTs, cohort or case–control studies. Economic evaluations | Single case reports, case series, studies where results for intervention and control groups are not presented separately |

DoH, Department of Health; LTC, long-term medical condition; RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

Search strategy

The searches inform both reviews, find any previous models that have been conducted in therapeutic writing and provide some inputs to the decision-analytic model. A database of published and unpublished literature will be assembled from searches using a comprehensive search strategy, examination of reference lists in systematic reviews, hand searching journals and contact with experts in the area. The wider searches will map the extent of relevant literature (mapping review). From this list of studies, appropriately includable studies for the systematic review will be selected, according to the inclusion criteria in table 1.

The following databases will be searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CAB Abstracts, PEDro, PILOTS, Zetoc, Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, Periodicals Index Online, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), ERIC, AMED, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for primary studies. Grey literature searching is important because of the possibility that effect size estimates may have been overestimated due to selective reporting bias and unpublished studies are known to be less likely to have statistically significant results compared with published studies.24 Information on studies in progress and unpublished research or research reported in the grey literature will be sought by searching a range of relevant databases including the Inside Conferences, Systems for Information in Grey Literature (OpenSIGLE), Dissertation Abstracts, Current Controlled Trials database and Clinical Trials.gov. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) and the Campbell Library will be searched for systematic reviews and economic evaluations. In addition, Internet searches will also be carried out using specialist search gateways (such as OMNI: http://www.omni.ac.uk/), general search engines (such as Google: http://www.google.co.uk/) and metasearch engines (such as Copernic: http://www.copernic.com/).

Citations will be selected for inclusion in each review in a two-stage process using the criteria in table 1 by one reviewer with a random 10% of citations independently checked by a second reviewer. Copies of full manuscripts of all citations that are likely to meet the selection criteria will be obtained. Two reviewers will then independently select studies that meet the predefined criteria. Disagreements will be resolved by consensus and/or arbitration involving a third reviewer. Authors of conference abstracts will be contacted for fully published articles. If an abstract only is available, results will be in an appendix. Once the final sample for the systematic review has been identified, each paper will be tracked in Science Citation Index and titles screened independently to identify sister papers of these documents.

Definition of LTCs

There is no definitive list of LTCs and the potential range of diseases of interest is extensive and diverse. For the purposes of this review, we will adopt the UK DoH definition of an LTC: “Long term conditions are those conditions that cannot, at present, be cured, but can be controlled by medication and other therapies. They include diabetes, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.” Our working definition of LTCs also includes mental health problems, including eating disorders, and chronic infections such as HIV. All cancer studies will be included because previous reviewing experience has shown that patients may receive palliative care for prolonged periods and terminally ill patients in hospices may still be receiving active treatment. Thus the distinction between active treatment and palliation may become difficult to distinguish and furthermore disease trajectories are not always predictable. There is a debate around whether obesity in the absence of any comorbidity is a disease25 and we will exclude studies in people with uncomplicated overweight and obesity. We will also evaluate addictive conditions (alcohol, smoking, illegal drugs and legal drugs) and learning disability because the results would be useful to the NHS, although these may not meet the current definition of LTCs. We have excluded the following:

Personality traits such as alexithymia, body dissatisfaction.

People who have undergone stressful life events such as bereavement, domestic violence and child sex abuse.

People found to be at increased risk of developing an LTC.

Systematic review of effectiveness

Studies’ findings will be extracted in duplicate using predesigned and piloted data extraction forms, based on those previously developed. Any disagreements will be resolved by consensus and/or arbitration involving a third reviewer. Missing information will be obtained from investigators if it is crucial to subsequent analysis. To avoid introducing bias, unpublished information will be coded in the same fashion as published information. In addition to using multiple coders to ensure the reproducibility of the overview, sensitivity analyses around important or questionable judgements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies, the validity assessments and data extraction will be performed.

Quality of selected studies will be assessed based on accepted contemporary standards such as the Newcastle Ottawa scale for cohort and case–control studies26 and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). The GRADE methodology27–29 will guide us when assessing the quality of the evidence overall and summarising the results.30 31

Meta-analyses will be conducted using standard software packages such as STATA. A special problem that we are likely to face is very little RCT evidence, which is why observational studies will be included for some types of interventions. Separate analyses will be performed on randomised and non-randomised data. Any heterogeneity of results between studies will be statistically assessed using I2 and graphically assessed, including use of funnel plots. We will explore causes of the heterogeneity and proceed to perform meta-analysis if appropriate.31 To explore causes of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses will be planned a priori to see whether variations in clinical factors, for example, populations, interventions, outcomes or study quality, affect the estimation of effects. Individual factors explaining heterogeneity will also be analysed using meta-regression, to determine their unique contribution to the heterogeneity, if possible.32 Conclusions regarding the typical estimate of an effect size of the intervention will be interpreted cautiously if there is significant heterogeneity. If necessary, we will use indirect comparisons to inform the economic model.

Health economic evaluation

This is a broad term to describe a variety of approaches that can be used to illustrate the economic consequences of a therapeutic strategy. In a project such as this, it is important to be flexible with regard to planning an economic evaluation because the depth of complexity of any economic modelling, for example, will be driven partially by the data available. If no health-related quality of life information is found, it may not be appropriate to state in advance that a cost utility analysis will be conducted. However, value for money is an important consideration in the current economic climate. So any information on costs and cost-effectiveness compared with an appropriate comparator will be presented. If any economic evaluations were found, they will be evaluated for quality using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) reference case and for publication standards using Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards statement.33

If there are well-powered RCTs with homogeneous outcomes in the same disease area or areas, we will then associate improvements in outcomes with gains in health-related quality of life where possible. This may include use of decision-analytic modelling either by using an existing disease-specific model available in the literature or by constructing a de novo model. The aim will be to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of incorporating therapeutic writing into the currently recommended NHS treatment regimen for the particular disease area. Results will be presented in terms of cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, with the uncertainty in both the RCT evidence and the modelling incorporated. If the information in the literature found in the systematic review is not sufficient, then we will carry out more general forms of economic evaluation such as cost-consequences or cost-minimisation analyses. All economic evaluations will follow the reference case used by the NICE as far as the available evidence permits, for example, discounting costs and benefits at 3% per annum, and using the perspective of the NHS and social services.

The economic modelling component of the work is likely to be challenging. Some of these challenges are likely to include the following: (1) the intervention is likely to affect a wide range of disease areas and clinical outcomes, which cannot be captured in a single disease model; (2) there may be a need to combine evidence, that is, heterogeneous in terms of quality (mixture of observational studies, trials and qualitative studies) as well as the nature of the intervention and population studied and (3) there may not be sufficient disease natural history and quality of life information in the literature to conduct a cost-utility analysis to the specifications of the NICE reference case.

To address these challenges, we have deliberately left the precise nature of the health economic evaluation open ended until after the literature reviews are completed. Whenever possible, we will conduct a ‘gold standard’ cost-utility analysis, using a decision analytic model to examine the impact of the intervention on disease progression, with its parameters informed by a synthesis of the highest quality RCT evidence, and with outcomes presented in terms of costs per QALY. However, we envision that the opportunities for this kind of analysis are likely to be slim. In most cases, we will make the most of any evidence available, for instance conducting cost-consequences analyses if there is no quality of life information or if there are a range of different outcomes that cannot be captured within a single model. Such analyses will still provide useful information to guide decision-making, and will also highlight the gaps in evidence that can be addressed by future studies.

Realist review

The realist review will cover the articles in the above sampling frame (table 1) along with ‘sister papers’ that is, any qualitative or mixed-method studies linked to these index papers, but published as a separate paper. The review team will begin by attempting to develop a ‘generic’ initial programme theory for therapeutic writing. That is, to build a model that tries to explain how therapeutic writing is meant to go about producing its potential benefits. When analysing the findings from the effectiveness review, we will use interpretive cross-case comparison to understand and explain how and why observed outcomes have occurred in the studies included in our review. In other words we will compare interventions where therapeutic writing has been ‘successful’ against those which have not; to try to understand how the context has (or has not) influenced the reported findings. Specifically, when analysing the findings from the effectiveness review, we will be using a realist logic that seeks to construct CMOCs for the findings in the ‘successful’ and ‘less successful’ therapeutic writing interventions. The purpose of this process is to construct for each finding (outcome) an explanation of what has caused the outcome to occur (mechanism) and the conditions (context) that have triggered this putative mechanism. If necessary, we will seek to iteratively develop one or more explanatory theories to account for these CMOCs. An important process is to build an understanding of how the CMOCs we have constructed fit in with our initial programme theory. In other words, for any one CMOC, how does it (if at all) explain how therapeutic writing is meant to go about producing its potential benefits? For example, does the CMOCs tell us anything about how we might need to refine our initial programme theory? Thus throughout the realist review, we move iteratively between the analysis of particular examples, a refinement of the over-arching programme theory and (if necessary) further iterative searching for data to test particular theories or subtheories. The pursuit of rigour in realist research reflects principles usually seen in qualitative research, although it may draw on qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. Much rests on achieving immersion (ie, reading and re-reading papers to really understand what was done and why), thinking reflexively about findings, developing theory iteratively as emerging data are analysed, seeking disconfirming cases and alternative explanations, and defending one's interpretations to researchers within and outside one's own team.34

Two coapplicants (TG and GW) have recently led an international project, the RAMESES study, which has developed guidance for realist review. This involved a systematically recruited group of international experts who have produced methodological guidance and publication standards (http://www.ramesesproject.org). We will ensure that the new RAMESES standards (which we anticipate will become the gold standard for realist review internationally) are strictly followed in the realist component of this study.

Narrative synthesis of systematic review of effectiveness, realist review and health economic evaluation

There are two published examples of combining conventional systematic review methods with realist review methods. One addressed the question “What is the impact of school feeding programmes on growth and educational achievement in deprived children, and what explains variation in the findings across studies?”35 36 The other addressed the question “What are the components and statistical properties of different risk scores for type 2 diabetes, and what explains whether and how these scores were used?”34 This review considered longitudinal and cross-sectional population cohort studies and papers describing case studies of attempts to implement the risk score. The therapeutic writing will use a similar approach to these two projects, using joining text and commentary (‘narrative synthesis’). This ‘narrative summary’ or ‘narrative synthesis’ is a very well established and robust way of linking two sets of review findings, especially when those sets of findings are philosophically incommensurable and/or address different research questions within a single study (hence do not lend themselves to a ‘technical’ approach to combining findings).37 38

We will also be integrating the results of the economic evaluation with the realist and conventional systematic reviews. Combining economic evaluation with systematic reviews is very commonly done for HTA reports, so needs no further explanation here. However, what is frequently not discussed is how the clinical context is combined with the economic evaluation to enable the HTA report to have clinical credibility. This is frequently done by ensuring that the clinicians on the project are present when discussing the economic model, fully understand it and can appreciate the implications of the assumptions made. Their insights into the patient experience often result in the structure of the model needing to be changed, or different numerical inputs being used to reflect clinical reality. In our project we will be fully involving patient representatives and therapeutic writing experts in all aspects of the project.

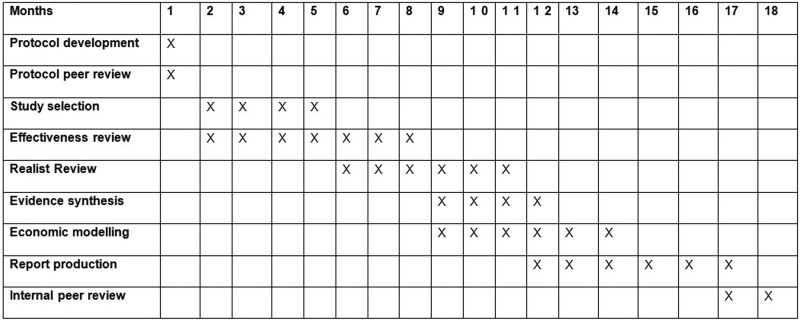

The reviews are currently underway and this 18-month project will be complete in summer 2014 (see figure 1—Gantt chart) with peer reviewed results available by the end of 2014.

Figure 1.

Timetable.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding and dissemination: This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) Programme (project number 11/70/01) and will be published in full in Health Technology Assessment. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, National Health Service (NHS) or the Department of Health. Findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, national and international conferences and relevant public health networks. This project is registered with PROSPERO database—CRD42012003343.

Funding: This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) Programme (grant number 11/70/01). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pearson L. The use of written communications in psychotherapy. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1965 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jolly M. What I never wanted to tell you: therapeutic letter writing in cultural context. J Med Humanit 2011;32:47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol 1986;95:274–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholls S. Beyond expressive writing: evolving models of developmental creative writing. J Health Psychol 2009;14:171–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker JR, Moore SM. Blogging as a social tool: a psychosocial examination of the effects of blogging. CyberPsychol Behav 2008;11:747–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton G, Field V, Thompson K, foreword by,et al. Writing works: a resource handbook for therapeutic workshops and activities. London and Philadelphia, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meads CA. Emotional disclosure (expressive writing) and health. Saarbrucken: VDM-Verlag, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meads C, Nouwen A. Does emotional disclosure have any effects? A systematic review of the literature with meta-analyses. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:153–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meads C, Sheffield D. Issues Regarding Systematic Review Reports and Trial Heterogeneity. J Nerv Ment Dis 2005;193:424–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogden J. Health psychology: a textbook. Maidenhead, BRK, England: Open University Press, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenhalgh T. Writing as therapy. Effects on immune mediated illness need substantiation in independent studies. BMJ 1999;319:270–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:174–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frisina PG, Borod JC, Lepore SJ. A meta-analysis of the effects of written emotional disclosure on the health outcomes of clinical populations. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192:629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2006;132:823–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris AH. Does expressive writing reduce health care utilization? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:243–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theadom A, Smith HE, Yorke J, et al. Written emotional disclosure for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD007676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, et al. The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA 2004;291:2616–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health U Ten things you need to know about long term conditions. 2011. [cited Mar 2011]. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Longtermconditions/tenthingsyouneedtoknow/index.htm

- 19.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouwens M, Wollersheim H, Hermens R, et al. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:141–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Astbury B, Leeuw FL. Unpacking black boxes: mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. Am J Eval 2010;31:363–81 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berwick D. The science of improvement. JAMA 2008;299:1182–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger MDK, Davey-Smith G. Problems and limitations in conducting systematic reviews. In: Egger MD-SG, Altman DG. ed Systematic reviews in healthcare, meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ Books, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heshka S, Allison DB. Is obesity a disease? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25:1401–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson A, Lissauer D, Thangaratinam S, et al. A comparison of clinical officers with medical doctors on outcomes of caesarean section in the developing world: meta-analysis of controlled studies. BMJ 2011;342:d2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, et al. GRADE: what is ‘quality of evidence’ and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008;336:995–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guyatt G, Oxman A, GE V, et al. Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latthe PM, Foon R, Khan K. Nonsurgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI): grading of evidence in systematic reviews. BJOG 2008;115:435–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, et al. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine: how to review and apply findings of healthcare research. London Royal Society of Medicine Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sterne JAC, Egger M. Regression methods to detect publication and other bias in meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ 2013;346:f1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noble D, Mathur R, Dent T, et al. A statistical feast but an impact famine: systematic review of risk scores for type 2 diabetes. BMJ 2011;343:d7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson E, Robinson V. Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programmes. BMJ 2007;335:858–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kristjansson E, Robinson V, Petticrew M, et al. School feeding for improving the physical and psychosocial health of disadvantaged elementary school children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD004676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Popay J. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC, 2006. http://citeseerxistpsuedu/viewdoc/download?doi=10111783100&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.