Abstract

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically determined process in all multicellular organisms. Plant PCD is effected by a unique group of papain-type cysteine endopeptidases (CysEP) with a C-terminal KDEL endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal (KDEL CysEP). KDEL CysEPs can be stored as pro-enzymes in ER-derived endomembrane compartments and are released as mature CysEPs in the final stages of organelle disintegration. KDEL CysEPs accept a wide variety of amino acids at the active site, including the glycosylated hydroxyprolines of the extensins that form the basic scaffold of the cell wall. In Arabidopsis, three KDEL CysEPs (AtCEP1, AtCEP2, and AtCEP3) are expressed. Cell- and tissue-specific activities of these three genes suggest that KDEL CysEPs participate in the abscission of flower organs and in the collapse of tissues in the final stage of PCD as well as in developmental tissue remodeling. We observed that AtCEP1 is expressed in response to biotic stress stimuli in the leaf. atcep1 knockout mutants showed enhanced susceptibility to powdery mildew caused by the biotrophic ascomycete Erysiphe cruciferarum. A translational fusion protein of AtCEP1 with a three-fold hemaglutinin-tag and the green fluorescent protein under control of the endogenous AtCEP1 promoter (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL) rescued the pathogenesis phenotype demonstrating the function of AtCEP1 in restriction of powdery mildew. The spatiotemporal AtCEP1-reporter expression during fungal infection together with microscopic inspection of the interaction phenotype suggested a function of AtCEP1 in controlling late stages of compatible interaction including late epidermal cell death. Additionally, expression of stress response genes appeared to be deregulated in the interaction of atcep1 mutants and E. cruciferarum. Possible functions of AtCEP1 in restricting parasitic success of the obligate biotrophic powdery mildew fungus are discussed.

Keywords: programmed cell death, plant immunity, sporulation, haustorium, cell wall

Introduction

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically determined, highly regulated process in all multicellular organisms (Hadfield and Bennett, 1997). PCD causes the loss of unpollinated ovules and the collapse of nucellus cells; it eliminates tissues and cells serving temporary functions during development such as the tapetum cells in anthers, the elimination of suspensor cells connecting the embryo to the mother plant and dissolution of endosperm cells in germinating castor beans (Pennel and Lamb, 1997; Olsen et al., 1999; Young and Gallie, 2000). Plants furthermore limit the spread of fungal or bacterial pathogens by rapid cell death at the site of infection through a mechanism called the hypersensitive response (HR) (Dickman and Fluhr, 2013).

Diverse classes of proteases are involved in PCD, including cysteine proteases, serine proteases, aspartic proteases and metalloproteases (Beers, 1997; Beers et al., 2000, 2004; Schaller, 2004). In plant PCD, special functions are described for vacuolar proteases (Müntz, 2007; Hara-Nishimura and Hatsugai, 2011), metacaspases (Lam and del Pozo, 2000; Xu and Zhang, 2009; Tsiatsiani et al., 2011) or subtilisin-like proteases (Vartapetian et al., 2011). Specific for plant PCD is a unique group of papain-type cysteine endopeptidases (CysEPs) characterized by a C-terminal KDEL endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal (KDEL CysEPs) with RcCysEP from castor bean (Ricinus communis) as the founding member (Schmid et al., 1998). KDEL CysEPs are not present in mammals or fungi, but are ubiquitous in plants (Hierl et al., 2012).

KDEL CysEPs exhibit a characteristic and unusually broad substrate specificity. The cleavage site ↓ within a substrate is denoted as P2-P1-↓-P1′-P2′. KDEL CysEPs have a clear preference for neutral amino acids with large aliphatic and non-polar (Leu, Val, Met) or aromatic (Phe, Tyr, Trp) side-chains in the P2 position and no clear preference in the P1 position, as it is typical for papain-type CysEPs. Unusually, they accept proline in the P1 and P1′ positions (Than et al., 2004; Hierl et al., 2013). Crystallization of the purified RcCysEP from castor bean as the founding member of KDEL CysEPs (Schmid et al., 1998) revealed that castor bean CysEP folds into two distinct domains of roughly equal size, as it is usual for papain-like CysEPs. The folding of RcCysEP is also very similar to the proline-specific cysteine peptidase from ginger (Zingiber officinale). The active site cleft of RcCysEP, however, is wider when compared to the ginger protease and papain (Than et al., 2004). RcCysEP can therefore digest extensins with its ability to accept glycosylated hydroxy-proline near the cleavage site (Helm et al., 2008). The respective amino acids (Leu, Met, Ala, Leu, Asn, Gly), which are decisive for this generally more open appearance of the active site cleft, together with the amino acids defining the catalytic pocket (Cys, His, Gln, Asn), are highly conserved among all known KDEL CysEPs (Hierl et al., 2012). Possibly, all KDEL CysEPs share the same broad substrate specificity. Extensins build the basic scaffold of the plant cell wall (Cannon et al., 2008), and thus KDEL CysEPs might support final cell collapse. KDEL CysEPs seem to have a dual set of substrates: digesting cytoplasmic components in cells of dying tissues for recycling to the surviving parts of the plant or in cells of germinating seedlings for mobilization of storage proteins, respectively, and digesting cell wall extensins in the final stage of PCD in support of the general cell collapse for tissue break down. Furthermore, KDEL CysEPs are expressed during tissue remodeling, possibly for clearance of dead cells and for generating space for plant organ outgrowth (Helm et al., 2008; Hierl et al., 2013).

It is obvious that KDEL-CysEPs are found in tissues undergoing PCD, especially in cells that finally collapse, such as the hypogeous cotyledons of Vicia sativa (Becker et al., 1997), the maturing pods of Phaseolus vulgaris (Tanaka et al., 1991), the unpollinated ovaries of Pisum sativum (Cercos et al., 1999), the outer integument developing into the seed coat of Phalaenopsis (Nadeau et al., 1996), the senescing flower petals of Hemerocallis (Valpuesta et al., 1995) and Sandersonia aurantiaca (O'Donghue et al., 2002), the megagametophyte cells after germination of Picea glauca seeds (He and Kermode, 2003), and the epigeous cotyledons of Vigna mungo (Toyooka et al., 2000). KDEL CysEPs were found in the senescing endosperm of germinating castor bean seeds (Schmid et al., 1999, 2001) and in the nucellus in maturing castor bean seeds, where the endosperm expands at the expense of the nucellus cells (Greenwood et al., 2005). They are expressed in both developing and dehiscing tomato anthers (Solanum lycopersicum) (Senatore et al., 2009) and in endosperm cells of imbibed tomato seeds (Trobacher et al., 2013).

In Arabidopsis, three KDEL CysEPs: AtCEP1 (At5g50260), AtCEP2 (At3g48340), and AtCEP3 (At3g48350) have been identified that are expressed in tissues undergoing PCD. Determination of promoter activities using β-glucuronidase as reporter in Arabidopsis transformants elucidated a remarkable tissue- and organ-specificity: AtCEP1 and AtCEP3 promoter activities were found in generative tissues at several stages of seed and fruit development such as AtCEP1 in the abscission zone and the nectaries of a silique or AtCEP3 in the maturing carpels. AtCEP1, AtCEP2, and AtCEP3 promoter activities were found in vegetative tissue such as AtCEP1 in the course of lateral root formation, AtCEP2 in roots within the root elongation zone and the beginning root cap, and AtCEP3 at the hypocotyl-root transition zone or in trichomes of leaves (Helm et al., 2008; Hierl et al., 2013).

KDEL CysEP are synthesized as pre-pro-enzymes and are co-translationally transferred into the ER, where the pre-sequence is removed. KDEL CysEPs can be stored as enzymatically inactive pro-enzymes in ER-derived compartments.

A spherical organelle surrounded by a single ribosome-studded membrane with a diameter averaging 1 μm was found in senescing endosperm tissue from castor bean. This organelle was discovered in ultrastructural and cytochemical studies independently by two groups in 1970. It was called “dilated cisternae,” since it seemed to develop from the ER (Vigil, 1970), or “ricinosome,” since it was found only in castor bean at that time (Mollenhauer and Totten, 1970). The ricinosomes were “re-discovered” with the identification of their marker enzyme, the KDEL CysEP (Schmid et al., 1998). Ricinosomes with their KDEL CysEP have been identified by immuno-electron-microscopy in the endosperm of germinating castor bean seeds (Schmid et al., 1999, 2001), in the nucellus of maturing castor bean seeds (Greenwood et al., 2005), in flower petals of Hemerocallis (Schmid et al., 1999), in the cotyledons of Vicia sativa (Becker et al., 1997), the unpollinated ovaries of Pisum sativum (Cercos et al., 1999), in tomato anthers (Senatore et al., 2009) and in endosperm cells of tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum) (Trobacher et al., 2013). Hence, the accumulation of KDEL CysEPs and the appearance of ricinosomes may be used as an early predictor of PCD.

KDEL-tailed protease-accumulating vesicles (KDEL vesicles, KVs) in germinating mung bean (Vigna mungo) cotyledons are similar to ricinosomes in that they accumulate the KDEL-tailed cysteine protease SH-EP (Toyooka et al., 2000). In contrast to ricinosomes, immunocytochemistry identified KDEL vesicles to transport large amounts of SH-EP from the endoplasmic reticulum to protein storage vacuoles. The mass transport of the proteinase by KDEL vesicles is thus involved in the protein mobilization of plants (Toyooka et al., 2000; Okamoto et al., 2003).

Interestingly, two different types of ER-derived organelles were found in Arabidopsis seedlings for storage of KDEL CysEPs using the mCherry-AtCEP2 reporter fusion protein (Hierl et al., 2013). mCherry-AtCEP2 was detected in the epidermal layers of leaves, hypocotyls and roots; in the root, it was predominantly found in the elongation zone and root cap. Co-localization with an ER membrane marker showed that mCherry-AtCEP2 was stored in 10 μm long spindle shaped organelles as well as round vesicles with a diameter of approximately 1 μm. The long organelles appear to be ER bodies, which are found specifically in Brassicales. The round vesicles strongly resemble ricinosomes (Hierl et al., 2013).

In plant microbe-interaction PCD has to be tightly controlled. Biotrophic pathogens are restricted by PCD because they strictly depend on living host tissue to feed from. PCD is an integral part of the HR by which plants restrict biotrophs in particular if triggered by recognition of microbial effectors. By contrast, if host PCD is triggered by hemibiotrophic or necrotrophic pathogens, it may foster disease by producing dead defenseless tissue that is easily accessible for the pathogen (Dickman and Fluhr, 2013). Papain-type cysteine proteases are involved in plant-microbe interactions. They are expressed in response to biotic stress and can be direct or indirect targets of microbial virulence effectors (Shindo and Van der Hoorn, 2008). Publicly available expression data (www.genevestigator.com; Zimmermann et al., 2004) suggested that AtCEP1 (At5g50260, probe set ID 248545_at) is expressed in hormone response such as auxin in mutants of the constitutive photomorphogenic9 signalosome (csn4 and csn3; Dohmann et al., 2008) and in mutants that constitutively express defense responses such as cpr5 (Bowling et al., 1997; Clarke et al., 2000). AtCEP3 (At3g48350; probe set ID 252365_at) does not exhibit such a pronounced response, and no expression data are available for AtCEP2 (At3g48340). We hence wanted to know, if AtCEP1 is involved in pathogen defense. Therefore, we chose the interaction with an obligate biotrophic powdery mildew fungus Erysiphe cruciferarum because it allows for observation of quantitative disease phenotypes. We further had observed that a certain degree of late epidermal cell death occurred in the interaction of Arabidopsis with E. cruciferarum and thus analyzed wild type AtCEP1 and atcep1 mutant phenotypes in this interaction. Data introduce a function for AtCEP1 in limiting susceptibility of Arabidopsis to E. cruciferarum and suggest a role in controlling late stages of the compatible interaction. Apparently, AtCEP1-dependent PCD at late stages of the compatible interaction fulfills a function in limiting parasitic growth of the fungus.

Materials and methods

Generation of reporter lines expressing pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL and pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL, respectively, under control of the endogenous AtCEP1 promoter in the atcep1 knockout mutant

For the cloning strategy of the fusion gene coding for pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL under the control of the endogenous promoter of AtCEP1 (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL) and the primers used see Supplemental Figure S1. The sequence approximately 2000 bp upstream of the start Met, that was previously shown to confer tissue specific expression (Helm et al., 2008), was used as the AtCEP1 promoter region. We placed the first three amino acids Leu-Pro-Thr of the mature subunit C-terminal to the pro-sequence in front of the 3xHA tag in order to ensure processing of the pro-peptide during maturation of AtCEP1. The AtCEP1 promoter with the adjacent 5'UTR and the coding region for the pre-pro-sequence were amplified from WT (Col0) genomic DNA isolated by cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction (Murray and Thompson, 1980). The 3xHA tag was amplified from pNIGEL18 (Geldner et al., 2009) and EGFP was amplified from pEZS-CL (Cutler et al., 2000). The mature AtCEP1 subunit with the 3'UTR was amplified from WT (Col0) genomic DNA. The resulting PCR products were cloned into pGREEN conferring kanamycin resistance (Hellens et al., 2000; www.ac.uk). The final plasmid construct was sequenced and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (pGV3101) by electroporation. The construct PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL as a non-functional reporter protein lacking the mature AtCEP1 protease subunit was obtained in an analogous manner. It comprised the endogenous AtCEP1 promoter, the 5′UTR and the coding regions for the N-terminal pre-pro-peptide, for the 3xHA tag and EGFP and for the nine C-terminal amino acids of the mature AtCEP1 subunit, including the ER retention signal KDEL (for cloning strategy and primers used see Supplemental Figure S2). The resulting PCR products were cloned into pGREEN (Hellens et al., 2000). The final plasmid construct was sequenced and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (pGV3101) by electroporation.

Flowers from homozygous atcep1 knock out mutant plants (SAIL_158_B06) were transformed by floral dipping (Clough and Bent, 1998) resulting in plants expressing the functional (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL) or non-functional (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL) EGFP-reporter proteins, respectively. Eight different homozygous transformants for each construct were screened for high expression of the fusion protein by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and three were chosen for further analysis.

Leaf infection with powdery mildew and symptoms rating

Arabidopsis thaliana Col0 plants and the AtCEP1 T-DNA insertion mutants (SAIL_158_B06 and SALK_013036) as well as atcep1 knock out plants transformed with the functional reporter (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL in SAIL_158_B06) and atcep1 knock out plants transformed with the non-functional reporter (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL in SAIL_158_B06) were grown in a growth chamber at 22°C and a 10-h photoperiod with 120 μmol m−2 s−2 light and 65% relative humidity. The Arabidopsis compatible powdery mildew fungus Erysiphe cruciferarum was grown on Arabidopsis Col-0 plants and for increased conidia production on Arabidopsis pad4 mutant plants (Glazebrook et al., 1996) at the same conditions. Five-week-old Arabidopsis plants were inoculated with E. cruciferarum for macroscopy and microscopy evaluation of disease progression with a density of 5–7 conidia mm−2. Arabidopsis susceptibility to E. cruciferarum was scored by visual examination of the whole plant 7, 9, 11, and 13 d after inoculation. Plants were distributed in three categories of susceptibility with 0–30%, 30–60%, and >60% diseased leaf area.

Staining of fungal structures with wheat germ agglutinine-tetramethylrhodamine

Wheat germ agglutinin tetramethylrhodamin conjugate (WGA-TMR, Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Germany) binds to extra- and intracellular chitin of fungi. To investigate the development of E. cruciferarum on Arabidopsis, inoculated leaves were harvested 5 days after inoculation and were discolored in ethanol-acetic acid glacial (EtOH-HAc; 6:1). Before WGA-TMR staining, the leaves were washed with H2Odest to remove the EtOH-HAc solution and were incubated for 6 min in PBS buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, pH7.4). The leaves were placed into the staining solution [0.01 μ g/μ l WGA-TMR (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen), 0.01 μ g/μ l BSA, PBS buffer] and were vacuum infiltrated twice at −0,8 bar. After 24–48 h incubation in the dark at 4°C, three leaves from WT or atcep1 plants each containing 54 colonies, respectively, were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus BX61TRF, Japan). The results were reproduced in a second independent inoculation with 48 colonies analyzed on three leaves of WT and atcep1 plants, respectively.

Callose staining with methyl blue

Callose depositions in Arabidopsis cells were visualized by methyl blue (Sigma Aldrich Chemie GmbH, München, Germany) staining. The discolored and WGA-TMR stained leaves were rinsed with distilled water and transferred into 67 mM K2HPO4 buffer for 10 min followed by incubation for 3–4 h in the staining solution (0.05% methyl blue in 67 mM K2HPO4) in the dark and direct analysis by fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61TRF, Japan).

qRT-PCR

Primers used for qRT-PCR are: ACT8 qRT fw: TGAGACCTTTAATTCTCCAGCTATG; ACT8 qRT rv: CCAGAGTCCAACACAATACCG; PR1 qRT fw: GATGTGCCAAAGTGAGGTGTAA; PR1 qRT rv: TTCACATAATTCCCACGAGGA; PDF1.2 qRT fw: GTTCTCTTTGCTGCTTTCGAC; PDF1.2 qRT rv: GCAAACCCCTGACCATGT. Total RNA was extracted from leaves before and 12 h (hpi) and 1, 2, 3, and 5 days (dpi) post mildew inoculation. Leaves were collected from at least five individual plants and total RNA was extracted with a NucleoSpin RNA plant kit (Machery-Nagel) and 2 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with an oligo-dT primer and M-MulV Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas) following the manufacturers' instructions. Quantitive real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a CFX96 Real-Time System Cycler (Bio-Rad). A 50-cycle two-step amplification protocol (10 s at 95°C, 25 s at 60°C) was used for all measurements.

Biochemical methods

Leaves were harvested 0–18 dpi days post inoculation with powdery mildew. A protein extract was prepared from one leaf (20–30 mg fresh weight). The plant material was ground with mortar and pestle under liquid N2 followed by the addition of loading dye (60 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.6, 5% glycerine, 1.5% SDS, 1.5% β-ME, 0.1% bromophenol blue final concentration), incubation for 10 min/95°C and analysation by SDS-PAGE followed by western blot analysis with anti-HA antibodies (Roche).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

CLSM (Fluoview FV 1000, Olympus, Japan) was performed using excitation at 488nm and emission detection between 503 and 550 nm for GFP. Single pictures or stacks of pictures with 0.5 μm increments at higher resolution and 2.5 μm increments at lower resolution were made.

Results

Homozygous atcep1 knock out mutants exhibit enhanced susceptibility to the biotrophic fungus erysiphe cruciferarum

Two AtCEP1 insertion lines, SAIL_158_B06 and SALK_013036, have the T-DNA insertion within the 3rd Exon. Both lines were homozygous, and RT-PCR using primers that amplified the coding region (spanning the T-DNA) confirmed the knock out of AtCEP1 (Figure 1). Wild type Col0 plants and the two homozygous atcep1 knock out mutants were inoculated with conidia of the powdery mildew fungus E. cruciferarum, an obligate biotroph that requires living cells for growth. Five week old plants were inoculated for evaluation of disease progression. Arabidopsis susceptibility to E. cruciferarum was scored by visual examination of the whole plant 7, 9, 11, and 13 days after inoculation. Both independent atcep1 knock out mutants lines exhibited the same phenotype, that is enhanced susceptibility to E. cruciferarum as compared to the parental wild type, as can be seen by visual examination of the whole plant for scoring the leaf area covered by powdery mildew symptoms (Figure 2, Supplemental Figure S3, see also below).

Figure 1.

Both AtCEP1 mutants SAIL_158_B06 and SALK_013036, harboring the T-DNA insertion in the 3. exon represents loss of function mutants. No corresponding transcript could be amplified by RT-PCR using primers that comprise the complete coding region from 7 days old seedlings, whereas the parent Col-0 wild type expressed the gene. wt, RT-PCR on wild type RNA; wt gen, PCR on wild type genomic DNA.

Figure 2.

Homozygous atcep1 knock out mutants with a T-DNA insertion in the 3. Exon exhibit enhanced susceptibility upon leaf inoculation with the biotrophic fungus Erysiphe cruciferarum. Leaves are shown 11 days post low density inoculation.

A functional reporter construct complements the pathogenesis phenotype of atcep1 knock out

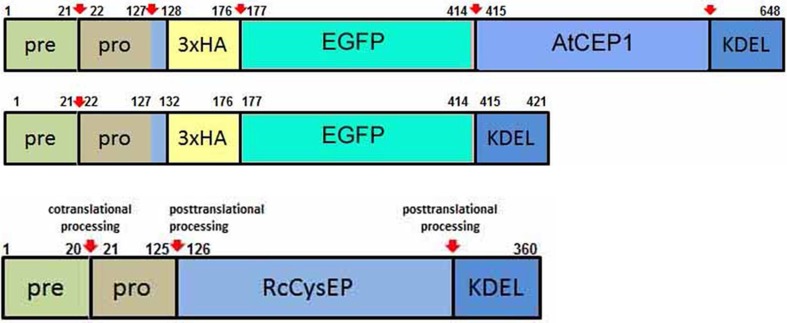

We constructed the fusion genes under the control of the endogenous AtCEP1 promoter for functional (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL) and non-functional (PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL) reporter constructs including EGFP with and without the mature AtCEP1 subunit (Figure 3, Supplemental Figures S1, S2, see Materials and Methods). The final plasmid constructs were sequenced and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens for subsequent transformation into atcep1 knock out plants SAIL_158_B06 in order to obtain plants expressing the functional or non-functional reporter proteins, respectively. Eight homozygous transformants for each construct were obtained. Three transformants for each construct exhibiting the highest fluorescence were chosen for further pathogen inoculation.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the functional reporter protein pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL and the non-functional reporter protein pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL expressed under the control of the endogenous AtCEP1 promoter. Both constructs were transformed into atcep1 knock out mutant line SAIL_158_B06. Pre-pro-RcCysEP is shown for comparison. Red arrows indicate proven or predicted protein cleavage sites.

Five week old plants were inoculated with the powdery mildew fungus E. cruciferarum and were scored for disease progression by visual examination of the whole plant 9, 11, and 13 days post inoculation: Plants were distributed in the three categories of susceptibility with less than 30%, 30–60%, and more than 60% of infected leaf area (Figure 4A). Significantly more plants of the atcep1 knock out line SAIL_158_B06 were classified in the category with >60% diseased leaf area compared to Col0 control plants. This was particularly obvious at later stages of the interaction, resulting in a super-susceptibility phenotype of the mutants. By contrast, atcep1 knock out plants transformed with the functional reporter construct reporter PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL exhibited a similar basal resistance to E. cruciferarum as compared to wild type Col0 plants thus proving the functionality of the reporter protein and complementation of the mutant phenotype. On the other hand, atcep1 knock out plants transformed with the non-functional reporter construct reporter PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL behaved similar to the original atcep1 knock out plants in showing super-susceptibility (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Disease symptoms of wild type and atcep1 mutant plants (SAIL_158_B06) upon leaf infection with Erysiphe cruciferarum spores. Wild type Col0 plants and atcep1 (SAIL_158_B06) plants transformed with the functional construct PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL that are comparable to wild type plants, and atcep1 mutant plants (SAIL_158_B06) transformed with the non-functional reporter PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL that are comparable to atcep1 knock out plants were infected with E. cruciferarum and disease symptoms were scored after visual inspection of the whole plant 9, 11, and 13 days post inoculation (dpi). Infected leaf were distributed in the three categories <30%, 30–60%, and >60% diseased leaf area. (A) Representative leaves were excised and photographed 11 dpi. (B) Columns marked with different letters indicate statistically different groups according to the ANOVA- and Duncan test (p < 0.05) and represent the frequency of plants distributed in the three categories of susceptibility. Data represent the respective means of seven experiments from independent inoculation events of the mutants with the corresponding parent background control. Each experiment comprised 5 plants per line.

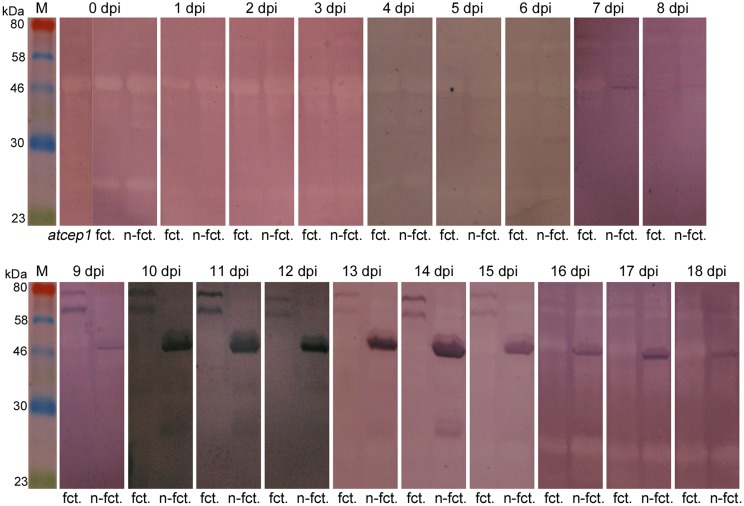

EGFP-AtCEP1 expression correlates with the appearance of leaf symptoms during infection with powdery mildew

For detection of AtCEP1 protein expression, we scored the appearance of AtCEP1 on total protein extracts from infected leaves of atcep1 knock out plants transformed with the functional reporter PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL that are comparable to wild type Col0 plants and atcep1 knock out plants transformed with the non-functional reporter PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL that are comparable to atcep1 knock out plants by immunoblot analysis with anti-HA antibodies (Figure 5). Pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL was detectable from day 9 on post inoculation and disappeared after day 15. Typically, two distinct protein bands are recognized by the anti-HA antibodies. Both proteins exhibit with molecular masses smaller than the 80 kDa marker the expected sizes based on their sequence with a calculated mass of 72.03 kDa and thus probably represent the intact pro-form of AtCEP1 with the C-terminal KDEL-motif still attached, however in different conformation. This double band was already found for the analogous pro-3xHA-mCherry-AtCEP2-KDEL reporter protein (Hierl et al., 2013). The non-functional reporter protein pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL was also detectable from day 7 post inoculation on and was found until day 18 post inoculation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL and pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL, respectively, are detectable from 9 days post inoculation (dpi) on upon leaf inoculation with Erysiphe cruciferarum. Immunoblots with anti-HA antibodies on total protein extracts from leaves of “wild type” plants (atcep1 SAIL_158_B06 transformed with the functional construct PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL) and atcep1 knock out plants (SAIL_158_B06 and SAIL_158_B06 transformed with the non-functional construct PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL). atcep1, SAIL_158_B06; fct, atcep1 plants transformed with the functional reporter pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL; n-fct, atcep1 plants transformed with the non-functional reporter pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-KDEL.

Cells attacked by erysiphe cruciferarum express EGFP-AtCEP1 in the endoplasmic reticulum and accumulate it around haustoria

To investigate the subcellular localization of AtCEP1 in vivo, we analyzed complemented mutant plants (atcep1 knock out plants transformed with the functional reporter PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL) during interaction with E. cruciferarum (12 dpi) by CLSM (Figure 6). Without inoculation, we never detected the functional EGFP fusion of AtCEP1. 12 dpi, the EGFP-AtCEP1 fusion protein displayed localization within the entire endoplasmatic reticulum of cells that were successfully penetrated by the fungus and accumulated especially around established haustoria (Figures 6A–C). A strong labeling around haustoria was also observed at the haustorial plane, where the network of the endoplasmic reticulum seemed to be very dense (Figures 6D–F).

Figure 6.

Cells attacked by Erysiphe cruciferarum express EGFP-AtCEP1 in the endoplasmic reticulum and accumulate it around haustoria. Localization of EGFP tagged AtCEP1 in Erysiphe cruciferarum attacked cells of Arabidopsis WT cells (atcep1 mutant plants transformed with the functional reporter PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL) upon fungal leaf inoculation 12 dpi. Brick like epidermis cells close to the main vessel are shown; cell outlines are indicated by white dotted lines (A,D). (A) Brightfield image of fungal structures on the leaf. Six bulbous haustoria are visible in the attacked cell (arrows and arrowheads). (B) EGFP-AtCEP1 shows localization in cortical net like structures and around haustoria. (C) Overlay of (A,B). (D–F) Strong accumulation of EGFP-AtCEP1 can be observed around the haustoria. Pictures display a magnified optical section of the area marked by the blue box in the pictures (A–C) in the level of the intracellular haustoria. Pictures are maximum projections of 24 optical sections (A–C) or 12 optical sections (D,E), respectively, with 0.5 μm increments.

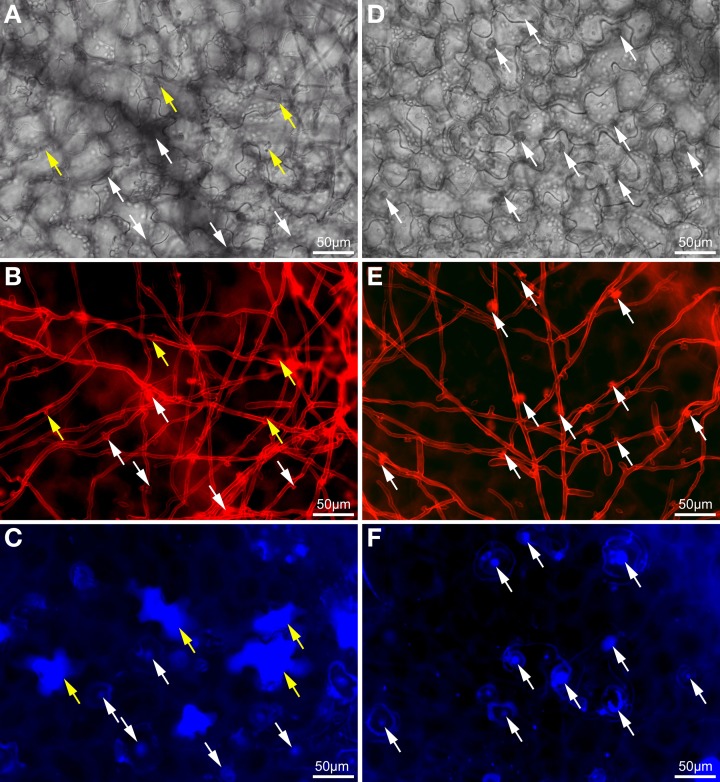

Wild type plants exhibit significantly more dead epidermal cells and less established haustoria as compared to atcep1 mutants upon inoculation with erysiphe cruciferarum

Visual examination of wild type and atcep1 mutant plants upon infection with E. cruciferarum suggested a role for AtCEP1 in restricting the development of a biotrophic fungus (Figure 4, Supplemental Figure S3). To assess the atcep1 knock out phenotype on a microscopic level we used two different labels: red fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin that stains the chitin of fungal hyphae and methyl blue that stains the callose at papillae and encasements of established haustoria as well as whole cells that die in the course of epidermal HR-like cell death (Figure 7). At 5dpi, fungal colonies on the wild type were grown to a size that about 24 haustoria were established per single fungal colony. In an average colony, 17 fungal attempts to penetrate were associated with localized callose depositions (papillae) without a visible haustorium. More than 19 cells per fungal colony displayed whole-cell callose deposition indicative of cell death, which was associated with fungal infection structures, in most cases collapsed haustoria. By contrast, the atcep1 mutant displayed significantly less epidermal cell death (7 cells per colony) per fungal colony and at the same time supported the development of more haustoria (37 per colony) in living cells. Hence, the atcep1 mutants displayed a failure to restrict establishment or maintenance of fungal haustoria under execution of an HR-like epidermal cell death (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Wild type plants exhibit significantly more dead epidermal cells and less established haustoria as compared to atcep1 mutants upon inoculation with Erysiphe cruciferarum. Microscopic phenotype of powdery mildew attacked cells on Arabidopsis WT (Col0) and the atcep1 knock out mutant (SAIL_158_B06) 5 dpi. WT cells show a frequent hypersensitive response (HR)-like reaction of penetrated cells (A–C) whereas no HR-like reaction is observed in the atcep1 mutant (D–F). (A,D) Brightfield image of the selected areas. (B,E) Fungal structures on the leaf surface and bulbous haustoria marked by white arrows were stained with wheat germ agglutinine-tetramethylrhodamine. (C,F) Callose was stained by methyl blue staining. Punctate methyl blue stained structures show papilla/cell wall appositions and encapsulated haustoria. Completely stained cells marked by yellow arrows indicate an HR-like cell death.

Figure 8.

The epidermal cell death is suppressed in cells attacked by Erysiphe cruciferarum on the atcep1 mutant 5 dpi compared to the WT. Columns show the frequency per colony of epidermal cell death, haustoria and papilla in cells attacked by E. cruciferarum. Data present the mean of 54 colonies on three leaves per wild type and atcep1 mutant line, respectively. Error bars are standard deviations. Differences between wild type and atcep1 are highly significant after two sided student's t-test p < 0.001 (***). The results were similarly reproduced in a second independent inoculation with 48 colonies on three leaves per WT and atcep1 mutant line, respectively.

Pathogen-responsive genes expression in atcep1

The difference in visual scoring leaf symptoms between wild type and atcep1 mutant plants was most obvious at 9 to 13 dpi. However, differences were observed in fungal development and in plant cell death responses at the microscopic level already at 5 dpi. By contrast, no differences were observed in fungal development or host defense responses at 1 dpi (data not shown). We also tested wild type and atcep1 mutants for differential expression of defense associated genes at 12 hpi, 1 dpi, 2 dpi, 3 dpi and 5 dpi. We measured relative expression of biotic stress markers PR1 and PDF1.2 (Reymond and Farmer, 1998) in wild type and atcep1 plants after powdery mildew inoculation. Expression levels were normalized to the reference gene ATC8, and expression before inoculation in each genotype was set to 1. At distinct stages of the interaction, powdery mildew inoculation provoked very high induction of PR1. PR1 gene expression was attenuated in super-susceptible atcep1 mutants at 5 dpi, which was coinciding with lower levels of epidermal cell death at this time (Figures 8, 9). By contrast, PDF1.2 expression in atcep1 transiently exceeded wild type level at 0.5 dpi and at 1 dpi (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Pathogen-responsive genes expression in atcep1. Relative gene expression of PR1 and PDF1.2 in wild type and atcep1 plants 12 h post mildew inoculation (hpi) and 1, 2, 3, and 5 days post mildew inoculation (dpi). qRT-PCR was performed with PR1 and PDF1.2 gene-specific primers. Expression levels were normalized to the reference gene ACT8 and expression before inoculation in each genotype was set to 1. The results were similarly reproduced by three independent inoculations. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE).

Discussion

PCD is part of the HR, which restricts growth of biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens in both basal resistance and in effector-triggered immunity (Dickman and Fluhr, 2013). In plants like in animals, proteases often mediate the decisive or executing steps of PCD. Papain-type cysteine proteases are involved in plant-microbe interactions. They are expressed in response to biotic stress and can be direct or indirect targets of microbial virulence effectors (Shindo and Van der Hoorn, 2008). This supports a fundamental function of papain-type proteases in plant defense. However, the identity and regulation of the proteases that are functional in particular plant-microbe interactions or in specific stages of such interactions are largely unknown. We show here that an ER-resident papain-type protease, which has been implicated in developmental cell death and tissue remodeling, is co-opted for a late defense reaction in a compatible interaction with a biotrophic fungus.

We tested the ability of wild type and atcep1 mutants to restrict growth of the biotrophic fungus E. cruciferarum to find possible evidence for a role of AtCEP1 in biotic stress responses and for a role of late epidermal cell death in restricting parasitic growth of an adapted powdery mildew fungus. This revealed super-susceptibility of two independent AtCEP1 T-DNA insertion mutants to powdery mildew. Both mutants lacked expression of AtCEP1 and can thus be considered as loss-of-function mutants. Basal resistance of Arabidopsis was re-constituted by a functional but not by a non-functional complementation construct. A native promoter functional AtCEP1-reporter construct allowed for the detection of AtCEP1 protein accumulation during late stages of the interaction. Together, this suggests that AtCEP1 is involved in basal resistance of Arabidopsis to powdery mildew.

Little is known about the function and efficacy of plant defense responses in compatible plant-pathogen interactions. Late epidermal PCD, as observed here, could either be an indication of fungal failure to maintain compatibility at the single cell level for a long time or an effective basal defense response of the susceptible host. Our data suggest that this type of PCD is under genetic control of the host and partially restricts fungal development during late stages of the interaction and sporulation. It is generally believed that in a compatible interaction of a susceptible host with a virulent pathogen most plant immune responses are successfully suppressed by pathogen effector molecules. Indeed, host papain proteases, which function in defense against nematodes, fungi or oomycetes, are inhibited by host and pathogen protease inhibitors that are delivered during compatible interactions (Bozkurt et al., 2011; Lozano-Torres et al., 2012; van der Linde et al., 2012). Partial inhibition of AtCEP1 by a protease inhibitor from E. cruciferarum or the late accumulation of AtCEP1 protein during pathogen interaction would explain why the pathogenesis phenotype of atcep1 was of quantitative nature. Furthermore, reporter expression of EGFP-AtCEP1 from PCEP1::pre-pro-3xHA-EGFP-AtCEP1-KDEL was detectable but irregular in cells penetrated by E. cruciferarum. Basal expression of the AtCEP1 gene is also low but detectable in leaves but higher in seeds, siliques, generative tissues and parts of the root (Helm et al., 2008 and unpublished results of the authors). Late defense-related expression points to possible hormone regulation of AtCEP1 during pathogenesis-induced physiological perturbations rather than expression in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns, which trigger early immune responses. Alternatively, pathogenesis might have caused a loss of tissue identity.

Cells attacked by E. cruciferarum expressed EGFP-AtCEP1 in the ER and accumulated it around haustoria but not in ricinosome-like structures or ER-bodies, in which AtCEP2 can be found (Hierl et al., 2012, 2013). Interestingly, mutants lacking functional AtCEP1 did not show the same frequency of cell death in attacked epidermal cells, when compared to wild type. This suggests that AtCEP1 is required to undergo this type of PCD during interaction with E. cruciferarum. However, we cannot yet distinguish whether this is due to a function in regulating epidermal PCD or in affecting the functionality of fungal haustoria. The accumulation of ER and EGFP-AtCEP1 at the plant-fungus interface let us speculate about a possible leakiness of the plant ER to the apoplast or to the extrahaustorial matrix. There are examples of plant KDEL-motif containing ER proteins, including papain-type proteases, that have a second destination in the apoplast or in the vacuole (Jones and Herman, 1993; Okamoto et al., 2003). Late-endosomal multivesicular compartments, which are by default delivered to the vacuole, and the tonoplast can also fuse with the plasma membrane during plant-pathogen interactions. Additionally, it is still unclear whether the host extrahaustorial membrane is an extension of the plasma membrane or originates from an endomembrane (An et al., 2007; Hatsugai et al., 2009; Hückelhoven and Panstruga, 2011; Dickman and Fluhr, 2013; Drakakaki and Dandekar, 2013). Hence, AtCEP1 could function in inhibiting haustorial functions when the protein leaks into the apoplast. Since KDEL CysEPs contain a cleavable KDEL ER retention motif (Figure 3), which is processed during protein activation (Than et al., 2004; Hierl et al., 2013), a novel mechanism would need to be postulated for controlled release of proteins from the ER.

Haustoria are likely the fungal cells, from which effector proteins are released to suppress host immune responses including the PCD. Therefore late expression of AtCEP1 could restrict haustorial functions in suppression of cell death. This is further supported because the reduction of cell death events in atcep1 was accompanied by a complementary increase in haustoria per fungal colony. Indeed, most of the dead cells in the wild type were successfully penetrated and contained haustoria. Alternatively, AtCEP1 might directly function in epidermal PCD. KDEL-cysteine peptidases like AtCEP1 are considered as late-acting proteases that digest cell wall proteins during the final stages of PCD and tissue remodeling after cellular disintegration (Helm et al., 2008; Hierl et al., 2012). However, a sole post cell death digestive function of AtCEP1 would not explain restriction of fungal growth. Post-cell death tissue-clearance cannot determine the outcome of the interaction, because the fungus strictly depends on an intact host cell for biotrophy at the single-cell level. An alternative explanation for the phenotype would be a new function of AtCEP1 in the initiation of epidermal cell death.

Epidermal PCD occurred late in the interaction with the virulent powdery mildew fungus. This makes it different from a canonical HR, which is observed early in effector-triggered immunity and is based on specific nonself recognition. We do not yet know whether this type of late epidermal cell death mechanistically resembles HR or a novel type of PCD. Additionally, defense gene expression was altered in atcep1 mutants before the pathogenesis-related phenotype became detectable. This might hind at a function of AtCEP1 in communication of the ER with the nucleus in stress-related gene expression.

Conclusion

Our data suggest a new function of AtCEP1 in late epidermal PCD in the interaction with the powdery mildew fungus. This PCD might possibly be a new type of PCD rather than classical HR. Future studies will shed light on the nature and regulation of this type of PCD and its role in interaction with other pathogens. Additionally, early differential expression of stress markers in atcep1 points to a possible involvement of AtCEP1 in crosstalk between the ER and biotic stress responses, that takes place before cell death is observed. Apparently, the ER KDEL-peptidase AtCEP1, which otherwise may function in developmental PCD, has an additional and pivotal function in translation of pathogenesis-related stress into leaf epidermal cell death and pathogen defense.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft: SFB924 to Erika Isono (A06), Christine Gietl (A07) and Ralph Hückelhoven (B08) and Gi154/14-1 to Christine Gietl.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscopy

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- 3xHA

three-fold hemagglutinin (HA) tag

- HR

hypersensitive response.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2014.00058/abstract

References

- An Q., van Bel A. J., Hückelhoven R. (2007). Do plant cells secrete exosomes derived from multivesicular bodies? Plant Signal. Behav. 2, 4–7 10.4161/psb.2.1.3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C., Senyuk V. I., Shutov A. D., Nong V. H., Fischer J., Horstmann C., et al. (1997). Proteinase A, a storage-globulin-degrading endopeptidase of vetch (Vicia sativa L.) seeds, is not involved in early steps of storage protein mobilization. Eur. J. Biochem. 248, 304–312 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers E. P. (1997). Programmed cell death during plant growth and development. Cell Death Differ. 4, 649–661 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers E. P., Jones A. M., Dickerman A. W. (2004). The S8 serine, C1A cysteine and A1 aspartic protease families in Arabidopsis. Phytochemistry 65, 43–58 10.1016/j.phytochem.2003.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers E. P., Woffenden B. J., Zhao C. (2000). Plant proteolytic enzymes: possible role during programmed cell death. Plant Mol. Biol. 44, 399–415 10.1023/A:1026556928624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling S. A., Clarke J. D., Liu Y., Klessig D. F., Dong X. (1997). The cpr5 mutant of Arabidopsis expresses both NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance. Plant Cell 9, 1573–1584 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt T. O., Schornack S., Win J., Shindo T., Ilyas M., Oliva R., et al. (2011). Phytophthora infestans effector AVRblb2 prevents secretion of a plant immune protease at the haustorial interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20832–20837 10.1073/pnas.1112708109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M. C., Terneus K., Hall Q., Tan L., Wang Y., Wegenhart B. L., et al. (2008). Self-assembly of the plant cell wall requires an extensin scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2226–2231 10.1073/pnas.0711980105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cercos M., Santamaria S., Carbonell J. S. O. (1999). Cloning and characterization of TPE4A, a thiol-protease gene induced during ovary senescence and seed germination in pea. Plant Physiol. 119, 1341–1348 10.1104/pp.119.4.1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J. D., Volko S. M., Ledford H., Ausubel F. M., Dong X. (2000). Roles of salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, and ethylene in cpr -induced resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12, 2175–2190 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S. R., Ehrhardt D. W., Griffitts J. S., Somerville C. R. (2000). Random GFP::cDNA fusions enable visualization of subcellular structures in cells of Arabidopsis at high frequency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3718–3723 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman M. B., Fluhr R. (2013). Centrality of host cell death in plant-microbe interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 543–570 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmann E. M. N., Levesque M. P., Isono E., Schmid M., Schwechheimer C. (2008). Auxin responses in mutants of the Arabidopsis CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC9 signalosome. Plant Physiol. 147, 1369–1379 10.1104/pp.108.121061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakakaki G., Dandekar A. (2013). Protein secretion: how many secretory routes does a plant cell have? Plant Sci. 203–204, 74–78 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldner N., Denervaud-Tendon V., Hyman D. L., Mayer U., Stierhof Y.-D., Chory J. (2009). Rapid combinatorial analysis of membrane compartments in intact plants with a multicolor marker set. Plant J. 59, 169–178 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03851.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J., Rogers E. E., Ausubel F. M. (1996). Isolation of Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced disease susceptibility by direct screening. Genetics 143, 973–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood J. S., Helm M., Gietl C. (2005). Ricinosomes and endosperm transfer cell structure in programmed cell death of the nucellus during Ricinus seed development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2238–2243 10.1073/pnas.0409429102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield K. A., Bennett A. B. (1997). Programmed senescence of plant organs. Cell Death Differ. 4, 662–670 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara-Nishimura I., Hatsugai N. (2011). The role of vacuole in plant death. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1298–1304 10.1038/cdd.2011.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsugai N., Iwasaki S., Tamura K., Kondo M., Fuji K., Ogasawara K., et al. (2009). A novel membrane fusion-mediated plant immunity against bacterial pathogens. Genes Dev. 23, 2496–2506 10.1101/gad.1825209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens R. P., Edwards E. A., Leyland N. R., Bean S., Mulineaux P. M. (2000). pGreen: a versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 42, 819–832 10.1023/A:1006496308160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M., Schmid M., Hierl G., Terneus K., Tan M., Lottspeich F., et al. (2008). KDEL-tailed cysteine endopeptidases involved in programmed cell death, intercalation of new cells and dismantling of extensin scaffolds. Am. J. Bot. 95, 1049–1062 10.3732/ajb.2007404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Kermode A. R. (2003). Proteases associated with programmed cell death of megagametophyte cells after germination of white spruce (Picea glauca) seeds. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 729–744 10.1023/A:1025008117046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierl G., Höwing T., Isono E., Lottspeich F., Gietl C. (2013). Ex vivo processing for maturation of Arabidopsis KDEL-tailed cysteine endopeptidase 2 (AtCEP2) pro-enzyme and its storage in in endoplasmic reticulum derived organelles. Plant Mol. Biol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s11103-013-0157-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierl G., Vothknecht U., Gietl C. (2012). Programmed cell death in Ricinus and Arabidopsis: the function of KDEL cysteine peptidases in development. Physiol. Plant. 145, 103–113 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01580.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hückelhoven R., Panstruga R. (2011). Cell biology of the plant-powdery mildew interaction. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 738–746 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. M., Herman E. M. (1993). KDEL-containing auxin-binding protein is secreted to the plasma membrane and cell wall. Plant Physiol. 101, 595–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E., del Pozo O. (2000). Caspase-like protease involvement in the control of plant cell death. Plant Mol. Biol. 44, 417–428 10.1023/A:1026509012695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Torres J. L., Wilbers R. H., Gawronski P., Boshoven J. C., Finkers-Tomczak A., Cordewener J. H., et al. (2012). Dual disease resistance mediated by the immune receptor Cf-2 in tomato requires a common virulence target of a fungus and a nematode. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 10119–10124 10.1073/pnas.1202867109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer H. H., Totten C. (1970). Studies on seeds. V. Microbodies, glyoxysomes, and ricinosomes of castor bean endosperm. Plant Physiol. 46, 794–700 10.1104/pp.46.6.794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müntz K. (2007). Protein dynamics and proteolysis in plant vacuoles. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2391–2407 10.1093/jxb/erm089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. G., Thompson W. F. (1980). Rapid isolation of high-molecular-weight plant DNA. Nucl. Acid. Res. 8, 4321–4325 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau J. A., Zhang X. S., Li J., O'Neill S. D. (1996). Ovule development: identification of stage-specific and tissue-specific cDNAs. Plant Cell 8, 213–239 10.1105/tpc.8.2.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donghue E. M., Somerfield S. D., Heyes J. A. (2002). Organization of cell walls in Sandersonia aurantiaca floral tissues. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 513–523 10.1093/jexbot/53.368.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T., Shimada T., Hara-Nishimura I., Nishimura M., Minamikawa T. (2003). C-terminal KDEL sequence of a KDEL-tailed cysteine proteinase (sulfhydryl-endopeptidase) is involved in formation of KDEL vesicle and in efficient vacuolar transport of sulfhydryl-endopeptidase. Plant Physiol. 132, 1892–1900 10.1104/pp.103.021147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen O. A., Linnestad C., Nichols S. E. (1999). Developmental biology of the cereal endosperm. Trends Plant Sci. 4, 253–257 10.1016/S1360-1385(99)01431-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennel R. I., Lamb C. (1997). Programmed cell death in plants. Plant Cell 9, 1157–1168 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond P., Farmer E. E. (1998). Jasmonate and salicylate as global signals for defense gene expression. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 404–411 10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80264-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller A. (2004). A cut above the rest: the regulatory function of plant proteases. Planta 220, 183–197 10.1007/s00425-004-1407-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Simpson D., Gietl C. (1999). Programmed cell death in castor bean endosperm is associated with the accumulation and release of a cysteine endopeptidase from ricinosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14159–14164 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Simpson D. J., Sarioglu H., Lottspeich F., Gietl C. (2001). The ricinosomes of senescing plant tissue bud from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5353–5358 10.1073/pnas.061038298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Simpson D., Kalousek F., Gietl C. (1998). A cysteine endopeptidase with a C-terminal KDEL motif isolated from castor bean endosperm is a marker enzyme for the ricinosome, a putative lytic compartment. Planta 206, 466–475 10.1007/s004250050423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senatore A., Trobacher C. P., Greenwood J. S. (2009). Ricinosomes predict programmed cell death leading to anther dehiscence in tomato. Plant Physiol. 149, 775–790 10.1104/pp.108.132720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo T., Van der Hoorn R. A. (2008). Papain-like cysteine proteases: key players at molecular battlefields employed by both plants and their invaders. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9, 119–125 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00439.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Yamauchi D., Minamikawa T. (1991). Nucleotide sequence of cDNA for an endopeptidase (EP-C1) from pods of maturing Phaseolus vulgaris fruits. Plant Mol. Biol. 16, 1083–1084 10.1007/BF00016081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Than M. E., Helm M., Simpson D. J., Lottspeich F., Huber R., Gietl C. (2004). The 2.0-Å crystal structure of the KDEL-tailed cysteine endopeptidase from germinating endosperm of Ricinus communis confirms its function in the final stage of programmed cell death. J. Mol. Biol. 336, 1103–1116 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyooka K., Okamoto T., Minamikawa T. (2000). Mass transport of a KDEL-tailed cysteine protease (SH-EP) to protein storage vacuoles by endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicle is involved in protein mobilization in germinating seeds. J. Cell Biol. 148, 453–463 10.1083/jcb.148.3.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trobacher C. P., Senatore A., Holley C., Greenwood J. S. (2013). Induction of a ricinosomal-protease and programmed cell death in tomato endosperm by gibberellic acid. Planta 237, 665–679 10.1007/s00425-012-1780-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatsiani L., Van Breusegem F., Gallois P., Zavialov A., Lam F., Bozhkov P. V. (2011). Metacaspases. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1279–1288 10.1038/cdd.2011.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valpuesta V., Lange N. E., Guerriero C., Reid M. S. (1995). Up-regulation of a cysteine protease accompanies the ethylene-insensitive senescence of daylily (Hemerocallis) flowers. Plant Mol. Biol. 28, 575–582 10.1007/BF00020403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linde K., Hemetsberger C., Kastner C., Kaschani F., van der Hoorn R. A., Kumlehn J., et al. (2012). A maize cystatin suppresses host immunity by inhibiting apoplastic cysteine proteases. Plant Cell 24, 1285–1300 10.1105/tpc.111.093732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartapetian A. B., Tuzhikov A. I., Chichkova N. V., Taliansky M., Wolpert T. J. (2011). A plant alternative to animal caspases: subtilisin-like proteases. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1289–1297 10.1038/cdd.2011.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil E. L. (1970). Cytochemical and developmental changes in microbodies (glyoxysomes) and related organelles of castor bean endosperm. J. Cell Biol. 46, 435–454 10.1083/jcb.46.3.435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Zhang L. (2009). Plant caspase-like proteases in plant programmed cell death. Plant Signal. Behav. 4, 902–904 10.4161/psb.4.9.9531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T. E., Gallie D. R. (2000). Programmed cell death during endosperm development. Plant Mol. Biol. 44, 283–301 10.1023/A:1026588408152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P., Hirsch-Hoffmann M., Hennig L., Gruissem W. (2004). GENEVESTIGATOR. Arabidopsis microarray database and analysis toolbox. Plant Physiol. 136, 2621–2632 10.1104/pp.104.046367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.