Abstract

The persistence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori is due in part to urease and Msr (methionine sulfoxide reductase). Upon exposure to relatively mild (21% partial pressure of O2) oxidative stress, a Δmsr mutant showed both decreased urease specific activity in cell-free extracts and decreased nickel associated with the partially purified urease fraction as compared with the parent strain, yet urease apoprotein levels were the same for the Δmsr and wild-type extracts. Urease activity of the Δmsr mutant was not significantly different from the wild-type upon non-stress microaerobic incubation of strains. Urease maturation occurs through nickel mobilization via a suite of known accessory proteins, one being the GTPase UreG. Treatment of UreG with H2O2 resulted in oxidation of MS-identified methionine residues and loss of up to 70% of its GTPase activity. Incubation of pure H2O2-treated UreG with Msr led to reductive repair of nine methionine residues and recovery of up to full enzyme activity. Binding of Msr to both oxidized and non-oxidized UreG was observed by cross-linking. Therefore we conclude Msr aids the survival of H. pylori in part by ensuring continual UreG-mediated urease maturation under stress conditions.

Keywords: accessory protein, amino acid modification, GTPase, nickel (Ni), oxidative stress, protein oxidation

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium that colonizes the gastric mucosa [1] of approximately one-half of the world’s population [2]. The World Health Organization classifies H. pylori as a carcinogen and it is the causative agent of most peptic ulcer diseases, chronic gastritis and gastric cancer in humans [3]. The pathogenesis and persistence attributes of H. pylori rely on its ability to combat harsh conditions; these include both the acidic environment of the gastric lumen and chronic exposure to ROS (reactive oxygen species) [3]. During colonization, H. pylori induces an inflammatory response from the host in which ROS are produced by gastric cells [4], phagocytes [5] and other immune cells. ROS such as superoxide (O2−), H2O2 and HOCl [6] oxidize free amino acid residues or the residues within proteins, which often renders the proteins non-functional [7]. However, oxidation of a methionine residue can be enzymatically reversed, resulting in restoration of protein function [8]. This is accomplished by Msr (methionine sulfoxide reductase) [9–11]. Other important enzymes involved in combating oxidative stress in H. pylori include a superoxide dismutase (SodB), a catalase (KatA), AhpC (alkyl hydroperoxide reductase), a neutrophil-activating protein (NapA) and an NADPH quinone reductase (MdaB) [9,11].

In bacteria and other organisms, two types of Msr proteins have been described: MsrA and MsrB. These two forms of Msr reduce the two isomers Met(S)O and Met(R)O of methionine sulfoxide respectively [12,13]. In H. pylori, MsrA and MsrB are fused to constitute a 42 kDa protein [14]. An H. pylori msr-deficient strain has been shown to be highly sensitive to oxidative stress, and it has a greatly diminished ability to colonize the stomach [15]. H. pylori Msr has also been shown to play a role in protecting catalase from oxidative damage [16]. However, only a few methionine-rich proteins have been identified as Msr-interacting [16,17] and the full extent of the physiological roles of Msr remain unknown.

H. pylori resists the acidic environment of the gastric region by producing urease, which hydrolyses urea to bicarbonate and ammonia [18,19]. Urease is the most abundant protein made by H. pylori, as it accounts for more than 10% of the total protein synthesized by the bacterium [20,21]. Urease is composed of only two subunits, UreA and UreB [19], unlike other bacterial ureases that are composed of UreA, UreB and UreC subunits [25]. The maturation of urease requires incorporation of Ni (nickel) into the active site, which is accomplished by several accessory proteins [22,23]. In H. pylori, these include UreE, UreF, UreG and UreH [24]. On the basis of studies in Klebsiella aerogenes, it is generally accepted that UreD (UreH in H. pylori), UreF and UreG drive protein conformational change, lysine carbamylation and GTP hydrolysis respectively, whereas UreE functions as a metallochaperone of the maturation system [25–28].

Of the accessory proteins, UreG is the most highly conserved and shares sequence homology with ATP- and GTP-binding proteins [29]. UreG belongs to the group of homologous P-loop GTPases [26]. Loss of all urease activity occurs upon introduction of site-directed mutations at the nucleotide-binding domain for both H. pylori [30] as well as K. aerogenes UreG [26]. In addition to the nucleotide-binding domain, UreG is a methionine-rich protein with methionine comprising ~4.5% of the primary amino acid sequence. From a TAP (tandem affinity purification) approach with UreG as the bait protein, UreG was proposed to interact with up to 33 different proteins, of which one was Msr [27]. However, the role of Msr in this possible interaction has not been studied. The TAP results combined with the high proportion of methionine residues in UreG caused us to examine a role for Msr in urease maturation. The role of Msr was addressed by studying a Δmsr mutant and by assessing the ability of Msr to repair the oxidized methionine residues of UreG. Finally, we demonstrated the intimate interaction between purified UreG and Msr.

EXPERIMENTAL

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

H. pylori strain SS1 was used as the parental strain for all studies. H. pylori were routinely grown on Brucella agar (Oxoid) plates containing 10% defribrinated sheep blood (BA plates) (QuadFive) and maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2, 4% O2, balanced with N2, in a microaerobic humidified chamber. The Δmsr mutant was described previously [11,15]. Escherichia coli cultures were grown aerobically in LB (Luria–Bertani) broth or agar and ampicillin, kanamycin and chloramphenicol were added when needed at a final concentration of 100, 30 and 30 µg/ml respectively.

Protein purification

H. pylori UreG was expressed as a His6-tagged protein in E. coli BL2(DE3)-RIL (Novagen). Briefly, the ureG gene was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from strain 43504 as a template and primers NdeUreG (5′-ACGGCCTCATATGGTAAAAATTGGAG-3′) and XhoUreG (5′-GCGTAAGCTCGAGATCTTCCAATAAAGCGTTG-3′, designed to amplifyureG without its stop codon). The resulting 0.6 kb DNA fragment was digested with NdeI and XhoI, and ligated into the similarly digested expression vector pET21b (Novagen). The recombinant plasmid was sequenced at the Georgia Genomics Facility (University of Georgia, Athens, GA, U.S.A.) to ensure that no error was introduced by PCR. E. coli cultures harbouring the recombinant plasmid were grown to a D600 of 0.6 at 37°C in 500 ml of LB medium with chloramphenicol and ampicillin. Cultures were then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) at 37°C for 3 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellet was resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl and 40 mM imidazole), then broken by four passages through an ice-cold French pressure cell. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 15000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was loaded on to an Ni-NTA (Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid)–agarose (Qiagen) column pre-equilibrated with buffer A. Unbound proteins were removed by washing with the same buffer. Following washing, UreG was released from the column with buffer B (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole). UreG-containing fractions were dialysed against 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5. The dialysed samples were then subjected to SDS/PAGE (12.5%gels) to assess purity. Proteins were visualized with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. Pure UreG was then concentrated using an Amicon Ultra Centrifugal filter (Millipore) and protein concentration was determined with the BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein kit (Pierce) with BSA as the standard.

H. pylori Msr was expressed as a His6-tagged protein and purified in E. coli BL21(DE3)-RIL as described previously [17]. Briefly, E. coli cultures harbouring the recombinant plasmid were grown to a D600 of 0.6 at 37°C in 1 litre of LB medium with ampicillin and kanamycin. Msr was then purified using an Ni-NTA column as described above for UreG. Msr-containing fractions were pooled and loaded on to a Q-sepharose Fast Flow column (Sigma). Msr was washed from the column with 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5. H. pylori Trx (thioredoxin) and TrxR (Trx reductase)were expressed and isolated from E. coli as described previously [17].

GTPase assay

GTPase assays were performed using a Malachite Green-based kit (Innova Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 6 µM untreated, oxidized or repaired (see section on Msr repair) UreG was incubated with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 2.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM GTP for 30 min. Next, Gold mix (PiColorLock™ Gold plus accelerator) was added to the mixture and incubated for an additional 2 min. The stabilizer buffer was then incubated with the mixture for 30 min. Finally, absorbance was determined at 595 nm using a Molecular Devices plate reader. The readings obtained at A595 were compared with a standard curve with known amounts of phosphate. All steps were carried out at room temperature (22 °C).

Exposure of SS1 wild-type and Δmsr strains to oxygen stress and measurement of urease activity

H. pylori strain SS1 wild-type or the Δmsr mutant was grown for 48 h, resuspended in BHI (brain heart infusion) broth with 0.4% β-cyclodextrin, pH 7.0, and exposed to 21% O2 (air) for 2 h while shaking (200 rev./min) at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10000 g for 10 min and broken by sonication (Heat Systems Ultrasonics sonicator, 10 s at 4W output power and 40%duty cycle). Cell debris was removed via centrifugation at 14000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was assayed for urease activity according to the method of Weatherburn [31].

Partial purification of urease and Ni determination

Urease was partially purified from the oxygen-stressed SS1 wild-type and Δmsr strains as described previously [32] with the following modification. Briefly, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, was used as the starting buffer and the protein was washed from the Q-Sepharose HiTrap column (GE Healthcare) with a 0–600 mM NaCl gradient. The peak urease-containing fractions were pooled and dialysed overnight against 20 mM NaCl (atomic absorption grade), assayed for protein concentration (BCA protein assay kit) and Ni levels were measured by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (Shimadzu AA-6701F) as described previously [32].

Immunoblot and quantification of urease in H. pylori crude extracts

H. pylori SS1 wild-type or the Δmsr mutant was exposed to 21% O2 as described above. Cells were then resuspended in BHI broth with 0.4% β-cyclodextrin and broken by sonication. Approximately 10 µg of crude extract from both strains was then loaded on to SDS/PAGE (12.5% gels). One gel was stained with Coomassie Blue silver and proteins from the other gel were transferred electrophoretically on to a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting was carried out as described previously [33]. Briefly, the membranes were blocked in 3% gelatin prepared in TBS (Tris-buffered saline; 50 mM Tris and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6). Following blocking, the membranes were probed with rabbit anti-UreA antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:2000 in TTBS (0.1% Tween 20/TBS) plus 1% gelatin for 1 h and then washed with TTBS. The membranes were then incubated with goat anti-(rabbit IgG) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Bio-Rad Laboratories) diluted 1:2000 in TTBS plus 1%gelatin. After 2 h of incubation, the blot was developed with Nitro Blue Tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloroindol-3-yl phosphate. The relative quantity of the urease structural subunit bands (UreA and UreB) was calculated by densitometry.

Oxidation of purified UreG

Purified UreG at 27 µM was treated with 25–50 mM H2O2 for 3 h in the dark and at room temperature under aseptic conditions. Excess H2O2 was removed by overnight dialysis against 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5.

Repair of oxidant-damaged UreG

UreG or H2O2-treated (50 and 100 mM) UreG was repaired with Msr (equimolar concentration relative to UreG) or buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5) in the presence of 400 µM NADPH (Sigma), 5 µM Trx and 100 nM TrxR for 1 h at 37°C. GTPase activities were then measured.

Repair of oxidant-damaged urease

The Δmsr mutant was exposed to 2 h of oxygen stress and then urease was partially purified from the mutant as described above. Partially purified urease (14 µg of total protein) was incubated with 10 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) alone or with 10 mM DTT and 14 µg Msr at 37°C for 1 h. Urease activity was then measured according to the method of Weatherburn [31].

Asp-N endoproteinase (Asp-N) digestion and pseudo-MRM (multiple reaction monitoring) LC (liquid chromatography)–MS/MS (tandem MS) analysis

UreG samples were digested with Asp-N and analysed by C18 reverse-phase LC coupled with pseudo-MRM MS/MS as described previously [16]. Briefly, samples were heated to 60°C in 50 mM Tris/HCl and 0.5 mM zinc acetate at pH 8.0 in the presence of 10 mM DTT for 45 min. They were then allowed to cool to room temperature and Asp-N protease (Thermo Scientific Pierce) was added at 1:100 (protease/UreG) and digested overnight at 37°C. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis.

After digestion, samples were analysed using the LTQ front-end of an LTQ-FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) coupled to an Agilent 1100 HPLC system with Captive Spray ionization using an Advance Ion Source for Thermo MS (Michrom Bioresources) Samples were autoinjected on to a C18 trapping cartridge for desalting, followed by separation on a C18 capillary column [Michrom Bioresources, 0.2 mm×50 mm, 3 µm, 200 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm)] using a linear gradient from 95% Buffer A and (water and 0.1% formic acid) and 5% Buffer B (acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) to 40% Buffer A and 60% Buffer B, at a flow rate of 3 µl/min for 70 min. Elution times and MS/MS transitions specific for unoxidized and oxidized methionine-containing peptides at 35 V collision energy were manually determined on the basis of MS/MS analysis. For peptides containing two methionine residues, transitions were chosen that differentiated between oxidation on each methionine residue on the basis of fragment ion mass. For quantitative analysis, oxidized and unoxidized methionine-containing peptide m/z values were placed on an include list, and oxidation was carried out on the basis of the abundance of the selected MS/MS product ions determined as specific transitions for that peptide at the appropriate elution time.

Cross-linking and biotin label transfer

Purified UreG or 50 mM H2O2-treated UreG (oxUreG) was conjugated to Sulfo-SBED {sulfosuccinimidyl-2-[6-(biotinamido)-2-(p-azidobenzamido)hexanoamido]ethyl-1,3′-dithiopropionate} using the Sulfo-SBED biotin label transfer kit (Thermo Scientific). Sulfo-SBED was dissolved in dimethylformamide at 40 µg/ml and then added to UreG in PBS at a 5-fold molar excess. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark to preserve the aryl azide group. Excess Sulfo-SBED was removed via overnight dialysis against 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5. UreG or oxUreG conjugated to Sulfo-SBED (4 µM) was then incubated with equal molar concentrations of Msr, lysozyme or alone in a final volume of 40 µl for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. The binding of Msr to UreG was captured upon UV photoactivation of the aryl azide moiety. UV photoactivation was carried out using a 365 nm UV lamp held 5 cm from the mixture for 15 min on ice. The cross-linked mixture (20 µl) was then reduced with 0.5 M DTT in the dark for 10 min. The proteins were then resolved via SDS/PAGE followed by transfer on to a nitrocellulose membrane. The biotin label was detected by incubating the membrane-bound proteins with streptavidin–HRP (horseradish peroxidase) for 1 h. The membrane was developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

Statistical significance

Results are presented as the means ± S.D. All data comparisons were performed using Student’s t test. These values were calculated using the GraphPad QuickCalcs website (http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/).

RESULTS

Purification of UreG

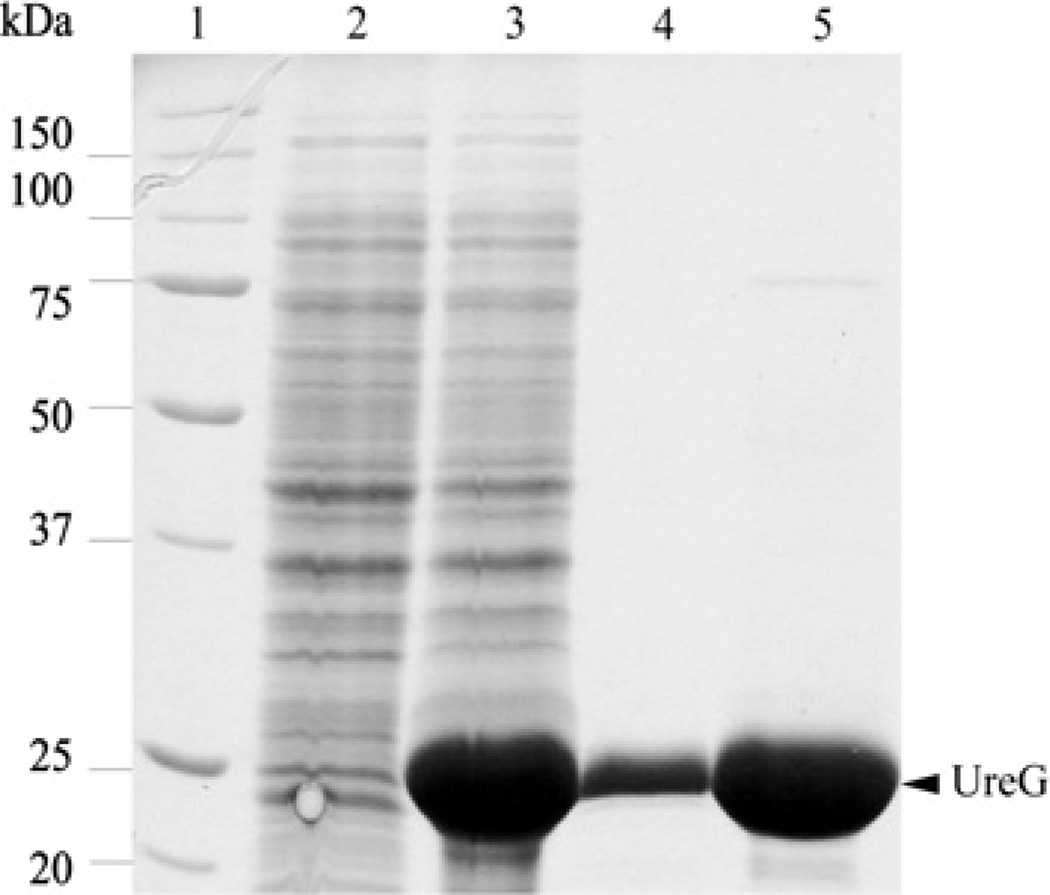

To study H. pylori UreG biochemically, the protein was overexpressed and purified as a recombinant His6-tagged protein from E. coli. The purity of the protein was assessed via SDS/PAGE analysis. The purified UreG migrated at a mass of approximately 24 kDa (Figure 1).

Figure 1. SDS/PAGE of purified UreG.

Lane 1, molecular mass marker with values indicated to the left in kDa; lane 2, cell extract from non-induced E. coli BL21(DE3)-RIL harbouring pET21b-ureG; lane 3, cell extract from IPTG-induced E. coli BL21(DE3)-RIL harbouring pET21b-ureG; lane 4, purified UreG after Ni-NTA extraction; lane 5, concentrated pure UreG. The arrowhead to the right indicates UreG.

Interaction between UreG and Msr

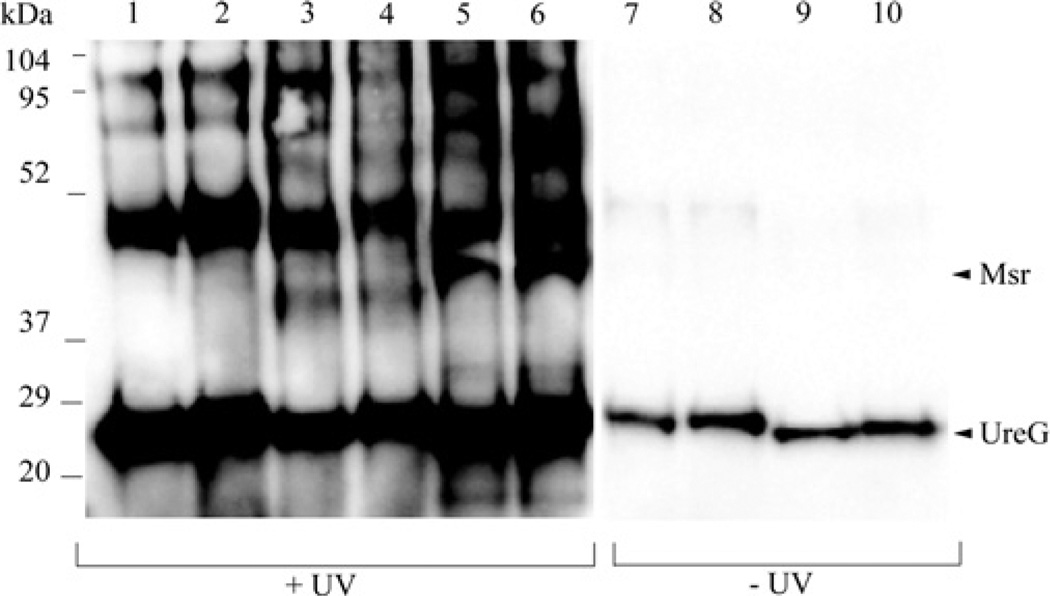

To analyse the direct binding of Msr to UreG we used a Sulfo-SBED trifunctional cross-linking reagent. Sulfo-SBED contains biotin, a sulfo-NHS (sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide) active ester, and a photoactivatable aryl azide. Upon incubation of untreated ‘as-purified’ UreG and separately H2O2-treated UreG (oxUreG) with Sulfo-SBED, the sulfo-NHS ester reacted with the amine groups of UreG at neutral pH, resulting in conjugation of UreG and the cross-linking agent. Unlabelled Msr or lysozyme (as a control) was added to the Sulfo-SBED-conjugated UreG or oxUreG and the aryl azide moiety within Sulfo-SBED was photoactivated with UV light to promote cross-linking. The binding event of Msr with UreG is thus captured so that disulfide bond cleavage by the addition of DTT then results in the transfer of the biotin tag to Msr. Samples were taken before and after UV cross-linking. The biotin label transfer is detected by Western blot using streptavidin–HRP and enhanced chemiluminescence. Msr bound to both oxidized and non-oxidized UreG as shown by the presence of an approximate 42 kDa band (Figure 2, lanes 5 and 6). These bands were not present when non-oxidized UreG or oxUreG was incubated alone (Figure 2, lanes 1 and 2) or with lysozyme (Figure 2, lanes 3 and 4). The absence of these bands from the samples incubated with lysozyme suggests that this 42 kDa band is not caused by protein aggregation and further confirms the specificity of the interaction between UreG and Msr. Higher molecular-mass bands observed in all lanes are believed to be UreG oligomers. UV-treated UreG contained more biotin label than the non-UV treated, presumably due to UV-light-mediated promotion of intramolecular tagging [34]. No intermolecular tag transfer to Msr was detected in the absence of UV light (Figure 2, lanes 9 and 10).

Figure 2. Interaction between UreG and Msr identified by biotin transfer.

Sulfo-SBED-conjugated UreG or 50 mMH2O2-oxidized UreG was incubated with Msr, lysozyme or alone and then the mixture was subjected to UV-cross-linking. Samples were taken before and after exposure to UV light. The conjugated samples were reduced with 0.5 M DTT for label transfer and the proteins were resolved via SDS/PAGE, transferred on to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with streptavidin–HRP. Lane 1, UreG; lane 2, oxidized UreG; lane 3, UreG and lysozyme; lane 4, oxidized UreG and lysozyme; lane 5, UreG and Msr; lane 6, oxidized UreG and Msr; lane 7, UreG; lane 8, oxidized UreG; lane 9, UreG and Msr; lane 10, oxidized UreG and Msr. Samples in lanes 7–10 were not exposed to UV light. The molecular masses are displayed to the left with values in kDa. The arrowheads to the right indicate Msr or UreG. UreG is ~22 kDa and Msr is ~42 kDa.

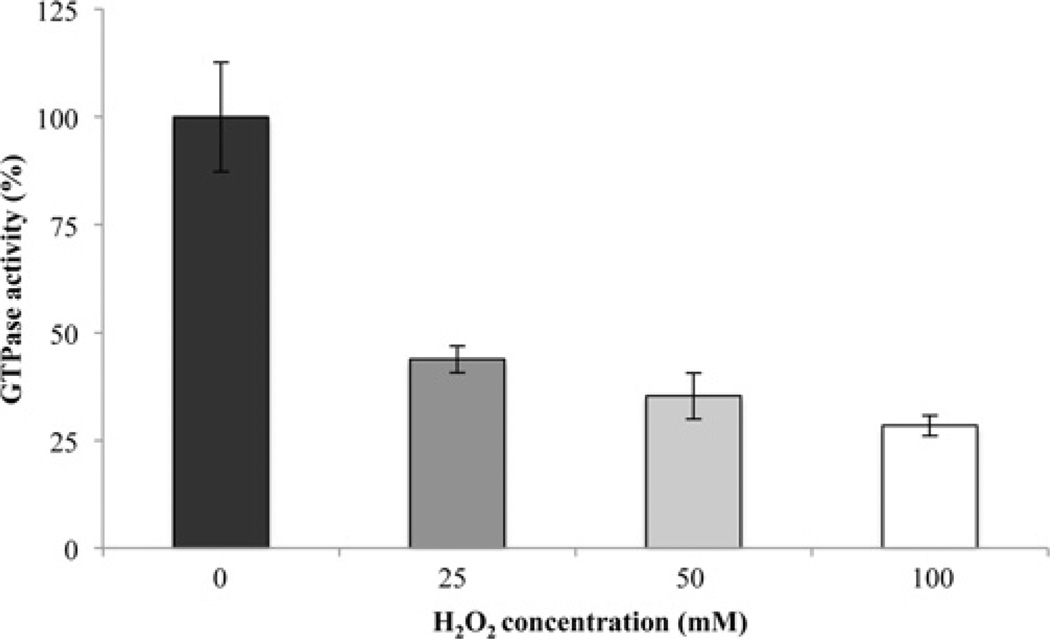

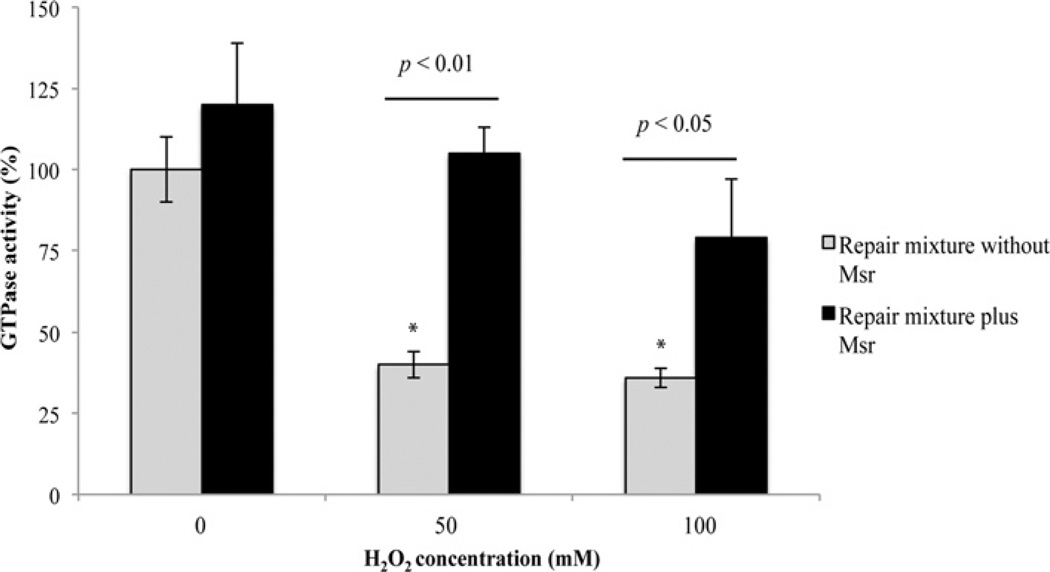

UreG activities in oxidized and repaired samples

To determine the susceptibility of H. pylori UreG to oxidant damage, we incubated purified UreG with H2O2 and measured the resulting GTPase activity. Incubation of purified UreG with H2O2 resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in GTPase activity (Figure 3). After incubation of 6 µM UreG with 25, 50 and 100 mM H2O2, the GTPase activity was significantly decreased to ~44, 35 and 28%of the untreated sample respectively. These oxidant levels seem high, but are the amounts sometimes used to oxidize repair targets. It is also important to note that pathogens are subject to a variety of oxidants simultaneously that are likely to exert a cumulative protein oxidation affect. The GTPase activity of H. pylori UreG has previously been shown to be negligible [30,35]. However, the calculated kcat of 0.032 min−1 for the untreated H. pylori UreG used in the present study is comparable with the measured GTPase activities of UreG in other organisms (Bacillus pasteurii UreG kcat = 0.04 min−1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis UreG kcat = 0.01 min−1, Glycine max UreG kcat = 0.01 min−1) [36–38]. To determine whether the decrease in GTPase activity after UreG incubation with H2O2 was due to methionine oxidation and also whether Msr is capable of restoring activity, oxidized UreG samples were incubated with Msr (plus repair system) and the resulting GTPase activities were measured. As a control, UreG was incubated with the repair components (Trx, TrxR and NADPH) without Msr. The latter sample is considered the untreated sample and is given 100% activity (in earlier experiments it had the same activity as untreated UreG with none of the repair mixture components added). Upon incubation with Msr-containing repair components (Msr, Trx, TrxR and NADPH), the activity of the oxidant-damaged UreG was restored (Figure 4); it achieved full (non-oxidant-treated) levels for the 50 mM H2O2-oxidized sample and ~80% of the non-oxidant-treated levels for the 100 mM H2O2-treated sample. GTPase restoration (i.e. repair) was never seen when the oxidized UreG samples were incubated with the repair system without Msr. These results indicate that Msr can repair oxidatively damaged UreG and restore enzyme activity. Interestingly, a 20% increase in activity with the addition of Msr to the untreated sample was sometimes observed, indicating some spontaneous UreG oxidation during preparation and storage.

Figure 3. H2O2 inactivation of UreG GTPase activity.

Purified UreG (6 µM) was incubated with various concentrations of H2O2 (0, 25, 50 or 100 mM) for 3 h. Excess oxidant was removed via overnight dialysis. GTPase activities were measured using a colorimetric assay to detect the release of Pi and are presented as percentage activity of the untreated sample. The untreated sample (100%) is 0.186 µmol Pi/min per mg of UreG. Each concentration is statistically significantly less than every higher concentration shown in the Figure at P<0.05. Results are means ±S.D. (n = 8, two independent experiments were each sampled four times).

Figure 4. Msr repair of H2O2-damaged UreG.

H2O2-treated UreG (6 µM) was incubated with equimolar amounts of Msr or buffer, along with the Msr repair components (400 µM NADPH, 5 µM Trx and 100 nM TrxR) at 37°C for 1 h. The samples were then assayed for GTPase activity spectrophotometrically. UreG GTPase activity of the untreated sample without the addition of Msr is considered as 100% and is 0.136 µmol of Pi/min per mg of UreG. Results are means ±S.D. (n = 6, three independent experiments sampled in duplicate).

MS/MS identification of methionine residues oxidized and repaired in UreG

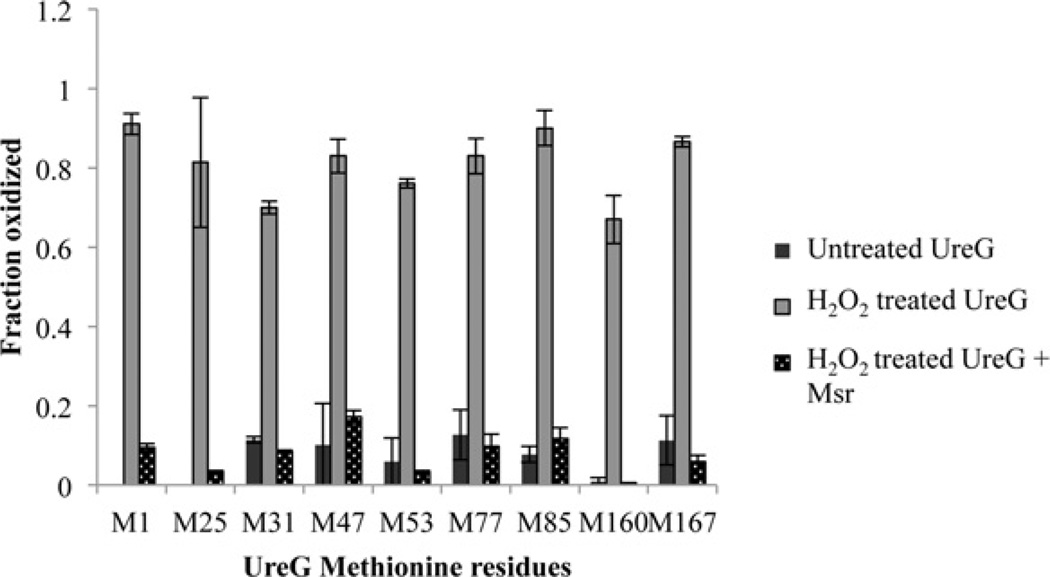

UreG samples were digested with Asp-N and the resulting peptide mixture was then subjected to LC–MS/MS. All nine methionine residues of UreG could be identified and they all showed significant oxidation after treatment with 50 mMH2O2 (Figure 5). For all untreated samples, the oxidation for all methionine residues remained less than 10%. Met1, Met25, Met47, Met77, Met85 and Met167 were all greater than 80% oxidized after treatment with H2O2. Met31, Met53 and Met160 were ~70–80% oxidized. After incubation of the oxidized samples with Msr plus 10 mM DTT as the reducing agent, all methionine residues remained less than 20% oxidized (Figure 5). DTT alone did not cause Met-SO (methionine sulfoxide) repair of any residues. The results indicate that Msr is able to repair all methionine residues of UreG.

Figure 5. MS/MS identification of methionine residues after oxidation and repair of UreG.

UreG was incubated with buffer or 50 mM H2O2 in buffer for 3 h. Excess H2O2 was removed via overnight dialysis. Following dialysis, oxidized UreG samples were incubated with or without Msr in the presence of DTT at 37°C for 1 h. DTT alone did not result in the repair of any methionine residues. No oxidized Met1 or Met25 could be detected in the untreated sample. Samples were digested with Asp-N and methionine residues were identified and quantified by LC–MS/MS.

Urease activities in wild-type and Δ msr strains after exposure to mild oxidative stress

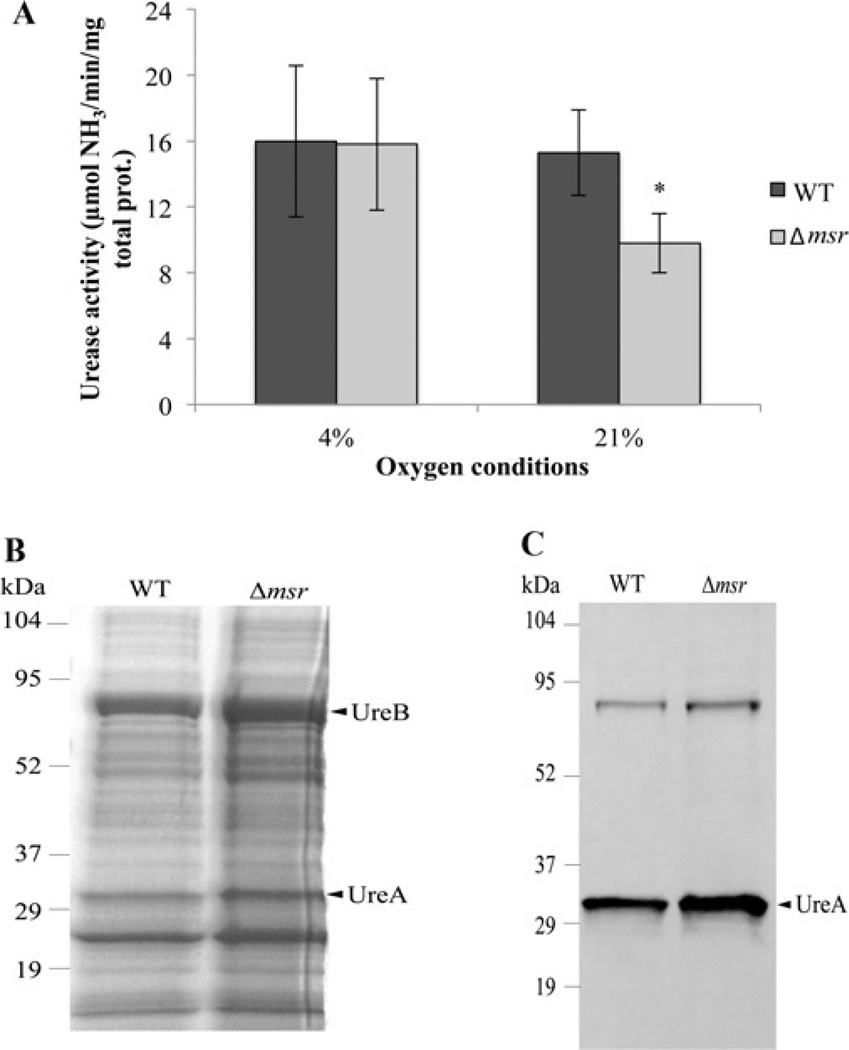

Despite expressing a broad repertoire of stress-combating enzymes and being an obligate aerobe, H. pylori is sensitive to oxidative molecules, including high oxygen. All wild-type strains of the bacterium are routinely grown in controlled atmospheres maintained below 12%partial pressure O2 [10]. We thus addressed the physiological importance of UreG repair under a relatively mild stress condition, i.e. ambient O2 levels. Since the UreG GTPase activity is susceptible to oxidation (Figure 3), and the activity is restored by Msr (Figure 4), we reasoned the importance of UreG repair could be assessed by comparing the Δmsr mutant with the parent in urease activity upon cell exposure to 2 h of ambient O2. This mild oxidant treatment has been used previously to study roles of oxidative stress enzymes in whole H. pylori cells [39,40]; the 2 h treatment causes viability loss of some oxidative-stress-sensitive mutants, but the parent strain maintains full viability (but not growth) during this incubation [15,40]. A significant decrease in cell-free extract urease activity to 64%of the parent strain level was observed in the Δmsr mutant (Figure 6A) after 2 h of air exposure. As a control, the wild-type and Δmsr strains were left at 4%partial pressure oxygen and the Δmsr mutant showed no statistically significant difference from the wild-type in activity over the 2 h period (Figure 6A). If urease maturation is the deficiency associated with the Δmsr mutant, we would expect urease apo-protein levels to be equal in that mutant and the parent. Urease apo-protein levels indeed appear to be similar in the wild-type and Δmsr strains (Figures 6B and 6C), and densitometric scanning [32] of these gels (from Figure 6B) confirmed that UreA and UreB subunits did not differ by more than 5% among the two strains.

Figure 6. Urease activity and expression after oxidant stress.

(A) Urease activity after exposure to oxidative stress. H. pylori SS1 wild-type (WT) and Δmsr strains were exposed to 21% O2 (air) for 2 h or left at 4% O2 as a control. Cells were then lysed by sonication and urease activity was measured in cell-free extracts. Results are means ±S.D (n = 12, based on four independent experiments each sampled in triplicate). *P < 0.01. (B) SDS/PAGE analysis of cell-free extract from SS1 wild-type (9 µg) and Δmsr (10 µg) after exposure to 21%O2. (C) Immunoblot analysis of SS1 wild-type and Δmsr cell-free extract after exposure to 21% O2. Whole-cell extracts were resolved via SDS/PAGE, transferred on to a nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with anti-UreA antibodies. Molecular masses in kDa are indicated to the left-hand side of (B) and (C).

Evidence to suggest this decrease in activity is due to a deficiency of urease maturation was obtained by measuring the Ni content associated with partially purified urease of both parent and mutant strains. Urease was partially purified and the urease fractions were analysed for Ni levels. The Δmsr mutant contained 33% less Ni content than the wild-type (30 ± 1.6 ng of Ni per mg of protein for the wild-type and 20 ± 0.8 ng of Ni per mg of protein for Δmsr). These data were based on 13 replicates for each strain and the difference between the two strains was statistically significant (P<0.01). Still, as urease was only partially purified, some of the Ni measurement could be associated with other proteins in both strains. The decreased urease-specific activity shown in the oxygen-stressed Δmsr mutant raises the possibility that urease itself could be damaged by methionine oxidation during this treatment. To address this concern, partially purified urease from the oxygen-stressed Δmsr mutant was incubated with DTT, or with DTT and Msr. No gain in urease activity was seen in either case (results not shown). These results suggest that the decrease in urease activity observed in the oxidant-stressed strain is not due to methionine oxidation of urease. Rather, UreG and possibly other proteins involved in urease maturation are prone to methionine oxidation and can be repaired by Msr.

DISCUSSION

The long-term survivability of H. pylori in the host requires that the bacterium survive harsh conditions, including the host inflammatory responses. The pathogen’s persistence is key to the most severe disease symptoms, and is in part due to the battery of DNA-and protein-repair enzymes that confer oxidative stress resistance on the pathogen in vivo. Proteins are often the targets of ROS due to their abundance in cells and their ease of reactivity with oxidants, and methionine is one of the most sensitive amino acids to oxidation. It is of obvious benefit for the bacterium to repair damaged Met-SO-containing proteins rather than synthesize new proteins due to energy input costs for synthesis and in order to rapidly maintain key enzyme function.

Many oxidative-stress-combating enzymes have been described in H. pylori, but our knowledge of the significance and physiological role of Msr continues to expand. An H. pylori Δmsr mutant shows attenuated growth in the presence of chemical oxidants and the strain is severely deficient in its ability to colonize the mouse stomach [15]. In addition, carbonylated proteins have been shown to accumulate in a Δmsr mutant after exposure of cells to oxidant damage [16]. These proteins were not oxidized in the parent strain [15]. However, only a few specific targets of Msr-mediated repair in H. pylori have been identified. These include GroEL, SSR (site-specific recombinase), AhpC and catalase [16,17]. Msr-repair targets in other bacteria include GroEL and Ffh [41,42].

In the host gastric region, H. pylori is in frequent contact with acid and oxidative molecules. Urease is essential for H. pylori to survive the acid stress and it is a highly abundant protein that requires Ni to function. Inside the host, H. pylori probably encounters various levels of Ni, so it employs many Ni-sequestering proteins (HspA, Hpn and Hpn-like) thought to gather the ion for storage and possible transfer to the metalloenzymes [43–45]. To achieve optimal urease activity, the active sites must be fully loaded with Ni and the Ni demand is thus high; Ni-saturated urease contains 12 Ni atoms per molecule [46]. As Mobley et al. [47] demonstrated, higher counts of Ni in recombinant urease correlated with higher urease activities. We observed a 31% decrease in urease activity and a concomitant 33%decrease in urease-associated Ni levels in the Δmsr mutant compared with the parent after exposure to mild oxidative conditions (e.g. air). Although modest, we propose that this is significant to the in vivo situation, where methionine damage could be much greater, and more potent oxidants exist. Indeed, Stingl and De Reuse [48] calculated that under in vitro conditions without added Ni, only a small proportion of the urease active sites are filled with Ni, but that is sufficient for full acid resistance. Under similiar conditions (no added Ni), we still see a significant difference in the Ni load between the wild-type and Δmsr mutant, which further suggests a role for Msr in protecting urease maturation. In addition, HOCl is a highly potent oxidant (much more potent than H2O2) and it can achieve levels of 5 mM at sites of inflammation within the host [49]. The Msr-repairable methionine residues in E. coli GroEL were shown to be much more sensitive to oxidation by phagocyte-produced oxidants such as HOCl and peroxynitrite than to oxidants produced by bacterial metabolism such as H2O2 [42]. It seems possible that urease itself could be a target for oxidative inactivation, but a previous study using co-immunoprecipitation found no evidence for urease–Msr interactions [50]. Furthermore, in the present study, we saw no enhancement of activity when Msr was added to urease purified from oxygen-stressed cells. Taken together, our results indicate that non-lethal elevated oxygen (~21% partial pressure) caused a urease maturation defect.

Interestingly, the H. pylori urease maturation proteins have been reported to assemble at the cytoplasmic membrane in a pH-dependent manner when urease is also undergoing increased Ni-dependent maturation [51,52]. H. pylori Msr has also been shown to be membrane associated [15], so studies of Msr–UreG recognition (and perhaps roles of membrane proteins) as a function of pH may be informative. Although UreG complexes with UreE to function in Ni delivery [53,54], UreE does not seem to be a target for Msr; cross-linking approaches to identify such an interaction between the two proteins were negative [17]. Also, UreE is not a methionine-rich protein (~1.8% methionine), and other Msr targets are rich in methionine. In the present study, we found that UreG is sensitive to inactivation by H2O2 and, given that UreG is rich in methionine residues (4.5%), we speculated that it was inactivated due to methionine oxidation. We found that H2O2 greatly inhibited UreG GTPase activity compared with the untreated UreG sample. It is likely that the bulk of inactivation of enzyme activity is due to Met-SO formation since the other residues susceptible to oxidation (tyrosine and cysteine) occur in small amounts within UreG (1.5% each) and Msr (known to repair methionine residues only) restored the oxidized protein’s GTPase activity.

In H. pylori, Msr was able to restore full UreG enzyme activity. This is similar to Msr-mediated catalase repair in which Msr restored up to 82% of full enzyme activity [16]. All nine methionine residues in UreG showed susceptibility to oxidation, and all were repaired with the addition of Msr. Interestingly, almost all (eight out of nine) methionine residues in UreG are predicted to be surface- or solvent-exposed. This is consistent with evidence that exposed methionine residues are more readily oxidized by oxidants and would be expected to be accessible to Msr [55–58]. A few prior accounts of Met-SO protein repair upon oxidative inactivation have been demonstrated in other systems such as E. coli L12 protein [59] and H. pylori catalase [16]. Oxidation and/or repair of every methionine residue within an enzyme has not been shown previously in any other system. For E. coli GroEL, 12 out of 23 methionine residues were converted into Met-SO [42]. Some activity (70% compared with untreated) of GroEL was restored by Msr when the lowest oxidant concentration was used, but harsher oxidation led to the production of some methionine-sulfone residues. In this case no activity could be restored [40]. Analysis of oxidized or Msr-repaired E. coli Ffh showed that four out of five methionine-containing peptides were oxidized and repaired [41]. Not all methionine residues of H. pylori catalase were susceptible to HOCl-mediated oxidation, but those that were indeed became targets of repair [16]. Our experiments expand our understanding of the unusual recognition flexibility of Msr, in that all nine methionine residues are repaired, and another target enzyme with a defined physiological role in pathogenesis is identified.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr K. Bayyareddy for help with cross-linking experiments.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number RO1 AI077569]. J.S.S. acknowledges support for analytical instrumentation used in the present study from the National Institutes of Health [grant number RR005351] from the National Center for Research Resources.

Abbreviations used

- AhpC

alkyl hydroperoxide reductase

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

- BHI

brain heart infusion

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IPTG

isopropyl β -d-thiogalactopyranoside

- LB

Luria–Bertani

- LC

liquid chromatography

- Met-SO

methionine sulfoxide

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- Msr

methionine sulfoxide reductase

- MS/MS

tandem MS

- Ni-NTA

Ni2+ -nitrilotriacetate

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- sulfo-NHS

sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide

- Sulfo-SBED

sulfosuccinimidyl-2-[6-(biotinamido)-2-(p-azido benzamide)hexanoamido]ethyl-1,3′-dithiopropionate

- TAP

tandem affinity purification

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- Trx

thioredoxin

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

- TTBS

Tween 20/Tris-buffered saline.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Lisa Kuhns, Manish Mahawar and Robert Maier conceived and designed the experiments. Joshua Sharp performed the MS. Stéphane Benoit constructed the UreG overexpression plasmid and assisted with atomic absorption spectrometry. Lisa Kuhns performed all the experiments. Lisa Kuhns and Robert Maier interpreted the data and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser MJ, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori persistence: biology and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:321–333. doi: 10.1172/JCI20925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997;10:720–741. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagchi D, Bhattacharya G, Stohs SJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by gastric cells in association with Helicobacter pylori. Free Radical Res. 1996;24:439–450. doi: 10.3109/10715769609088043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramarao N, Gray-Owen SD, Meyer TF. Helicobacter pylori induces but survives the extracellular release of oxygen radicals from professional phagocytes using its catalase activity. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;38:103–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa O, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. Helicobacter pylori: a ROS-inducing bacterial species in the stomach. Inflamm. Res. 2010;59:997–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00011-010-0245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stadtman ER, Levine RL. Protein oxidation. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2000;899:191–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brot N, Fliss H, Coleman T, Weissbach H. Enzymatic reduction of methionine sulfoxide residues in proteins and peptides. Methods Enzymol. 1984;107:352–360. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(84)07023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olczak AA, Olson JW, Maier RJ. Oxidative-stress resistance mutants of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:3186–3193. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.12.3186-3193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang G, Alamuri P, Maier RJ. The diverse antioxidant systems of Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:847–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang G, Conover RC, Benoit S, Olczak AA, Olson JW, Johnson MK, Maier RJ. Role of a bacterial organic hydroperoxide detoxification system in preventing catalase inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:51908–51914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408450200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimaud R, Ezraty B, Mitchell JK, Lafitte D, Briand C, Derrick PJ, Barras F. Repair of oxidized proteins. Identification of a new methionine sulfoxide reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48915–48920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauffmann B, Aubry A, Favier F. The three-dimensional structures of peptide methionine sulfoxide reductases: current knowledge and open questions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1703:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alamuri P, Maier RJ. Methionine sulphoxide reductase is an important antioxidant enzyme in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:1397–1406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahawar M, Tran V, Sharp JS, Maier RJ. Synergistic roles of Helicobacter pylori methionine sulfoxide reductase and GroEL in repairing oxidant-damaged catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:19159–19169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alamuri P, Maier RJ. Methionine sulfoxide reductase in Helicobacter pylori: interaction with methionine-rich proteins and stress-induced expression. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:5839–5850. doi: 10.1128/JB.00430-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn BE, Campbell GP, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Purification and characterization of urease from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:9464–9469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu LT, Mobley HL. Purification and N-terminal analysis of urease from Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 1990;58:992–998. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.992-998.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobley HL, Garner RM, Bauerfeind P. Helicobacter pylori nickel-transport gene nixA: synthesis of catalytically active urease in Escherichia coli independent of growth conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauerfeind P, Garner R, Dunn BE, Mobley HL. Synthesis and activity of Helicobacter pylori urease and catalase at low pH. Gut. 1997;40:25–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee MH, Mulrooney SB, Renner MJ, Markowicz Y, Hausinger RP. Klebsiella aerogenes urease gene cluster: sequence of ureD and demonstration that four accessory genes (ureD, ureE, ureF, and ureG) are involved in nickel metallocenter biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:4324–4330. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4324-4330.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cussac V, Ferrero RL, Labigne A. Expression of Helicobacter pylori urease genes in Escherichia coli grown under nitrogen-limiting conditions. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:2466–2473. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2466-2473.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton CL, Pallen MJ, Kleanthous H, Wren BW, Tabaqchali S. Nucleotide sequence of two genes from Helicobacter pylori encoding for urease subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:362. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park IS, Hausinger RP. Evidence for the presence of urease apoprotein complexes containing UreD, UreF, and UreG in cells that are competent for in vivo enzyme activation. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:1947–1951. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.1947-1951.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moncrief MB, Hausinger RP. Characterization of UreG, identification of a UreD-UreF-UreG complex, and evidence suggesting that a nucleotide-binding site in UreG is required for in vivo metallocenter assembly of Klebsiella aerogenes urease. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:4081–4086. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4081-4086.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stingl K, Schauer K, Ecobichon C, Labigne A, Lenormand P, Rousselle JC, Namane A, de Reuse H. In vivo interactome of Helicobacter pylori urease revealed by tandem affinity purification. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7:2429–2441. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800160-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soriano A, Colpas GJ, Hausinger RP. UreE stimulation of GTP-dependent urease activation in the UreD-UreF-UreG-urease apoprotein complex. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12435–12440. doi: 10.1021/bi001296o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moncrief MB, Hausinger RP. Purification and activation properties of UreD-UreF-urease apoprotein complexes. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5417–5421. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5417-5421.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta N, Benoit S, Maier RJ. Roles of conserved nucleotide-binding domains in accessory proteins, HypB and UreG, in the maturation of nickel-enzymes required for efficient Helicobacter pylori colonization. Microb. Pathog. 2003;35:229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(03)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weatherburn MW. Phenol-hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Anal. Chem. 1967;39:971–974. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olson JW, Mehta NS, Maier RJ. Requirement of nickel metabolism proteins HypA and HypB for full activity of both hydrogenase and urease in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:176–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minamisawa S, Hoshijima M, Chu G, Ward CA, Frank K, Gu Y, Martone ME, Wang Y, Ross J, Jr, Kranias EG, et al. Chronic phospholamban-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase interaction is the critical calcium cycling defect in dilated cardiomyopathy. Cell. 1999;99:313–322. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minami Y, Kawasaki H, Minami M, Tanahashi N, Tanaka K, Yahara I. A critical role for the proteasome activator PA28 in the Hsp90-dependent protein refolding. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9055–9061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.9055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minami Y, Minami M. Hsc70/Hsp40 chaperone system mediates the Hsp90-dependent refolding of firefly luciferase. Genes Cells. 1999;4:721–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambelli B, Stola M, Musiani F, De Vriendt K, Samyn B, Devreese B, Van Beeumen J, Turano P, Dikiy A, Bryant DA, Ciurli S. UreG, a chaperone in the urease assembly process, is an intrinsically unstructured GTPase that specifically binds Zn2+ J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:4684–4695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zambelli B, Musiani F, Savini M, Tucker P, Ciurli S. Biochemical studies on Mycobacterium tuberculosis UreG and comparative modeling reveal structural and functional conservation among the bacterial UreG family. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3171–3182. doi: 10.1021/bi6024676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Real-Guerra R, Staniscuaski F, Zambelli B, Musiani F, Ciurli S, Carlini CR. Biochemical and structural studies on native and recombinant Glycine max UreG: a detailed characterization of a plant urease accessory protein. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;78:461–475. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang G, Olczak AA, Walton JP, Maier RJ. Contribution of the Helicobacter pylori thiol peroxidase bacterioferritin comigratory protein to oxidative stress resistance and host colonization. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:378–384. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.378-384.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G, Maier RJ. An NADPH quinone reductase of Helicobacter pylori plays an important role in oxidative stress resistance and host colonization. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:1391–1396. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1391-1396.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ezraty B, Grimaud R, El Hassouni M, Moinier D, Barras F. Methionine sulfoxide reductases protect Ffh from oxidative damages in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2004;23:1868–1877. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khor HK, Fisher MT, Schoneich C. Potential role of methionine sulfoxide in the inactivation of the chaperone GroEL by hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19486–19493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seshadri S, Benoit SL, Maier RJ. Roles of His-rich hpn and hpn-like proteins in Helicobacter pylori nickel physiology. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:4120–4126. doi: 10.1128/JB.01245-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kansau I, Labigne A. Heat shock proteins of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996;10(Suppl. 1):51–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.22164005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilbert JV, Ramakrishna J, Sunderman FW, Jr, Wright A, Plaut AG. Protein Hpn: cloning and characterization of a histidine-rich metal-binding polypeptide in Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter mustelae. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:2682–2688. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2682-2688.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mobley HLT. Urease. In: Mobley HLT, Mendz GL, Hazell SL, editors. Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics. Chapter 16. Washington: ASM Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mobley HL, Hu LT, Foxal PA. Helicobacter pylori urease: properties and role in pathogenesis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1991;187(Suppl):39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stingl K, De Reuse H. Staying alive overdosed: how does Helicobacter pylori control urease activity? Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005;295:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss SJ. Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N. Engl. J.Med. 1989;320:365–376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902093200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alamuri P. Ph.D. Thesis. Athens, GA, U.S.A.: University of Georgia; 2006. The Role of Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase in Helicobacter pylori. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Wen Y, Singh S, Feng J, Sachs G. Cytoplasmic histidine kinase (HP0244)-regulated assembly of urease with UreI, a channel for urea and its metabolites, CO2, NH3, and NH4+, is necessary for acid survival of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:94–103. doi: 10.1128/JB.00848-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Weeks DL, Sachs G. Mechanisms of acid resistance due to the urease system of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:187–195. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rain JC, Selig L, De Reuse H, Battaglia V, Reverdy C, Simon S, Lenzen G, Petel F, Wojcik J, Schachter V, et al. The protein-protein interaction map of Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2001;409:211–215. doi: 10.1038/35051615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voland P, Weeks DL, Marcus EA, Prinz C, Sachs G, Scott D. Interactions among the seven Helicobacter pylori proteins encoded by the urease gene cluster. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G96–G106. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00160.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levine RL, Mosoni L, Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Methionine residues as endogenous antioxidants in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 1996;93:15036–15040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo S, Levine RL. Methionine in proteins defends against oxidative stress. FASEB. J. 2009;23:464–472. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-118414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vogt W. Oxidation of methionyl residues in proteins: tools, targets, and reversal. Free Radical Biol. Med. 1995;18:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00158-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiong Y, Chen B, Smallwood HS, Urbauer RJ, Markille LM, Galeva N, Williams TD, Squier TC. High-affinity and cooperative binding of oxidized calmodulin by methionine sulfoxide reductase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14642–14654. doi: 10.1021/bi0612465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caldwell P, Luk DC, Weissbach H, Brot N. Oxidation of the methionine residues of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein L12 decreases the protein’s biological activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 1978;75:5349–5352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]