Abstract

The tumor suppressor protein p53 regulates numerous signaling pathways by specifically recognizing diverse p53 response elements (REs). Understanding the mechanisms of p53-DNA interaction requires structural information on p53 REs. However, such information is limited as a 3D structure of any RE in the unbound form is not available yet. Here, site-directed spin labeling was used to probe the solution structures of REs involved in p53 regulation of the p21 and Bax genes. Multiple nanometer distances in the p21-RE and BAX-RE, measured using a nucleotide-independent nitroxide probe and double-electron-electron-resonance spectroscopy, were used to derive molecular models of unbound REs from pools of all-atom structures generated by Monte-Carlo simulations, thus enabling analyses to reveal sequence-dependent DNA shape features of unbound REs in solution. The data revealed distinct RE conformational changes on binding to the p53 core domain, and support the hypothesis that sequence-dependent properties encoded in REs are exploited by p53 to achieve the energetically most favorable mode of deformation, consequently enhancing binding specificity. This work reveals mechanisms of p53-DNA recognition, and establishes a new experimental/computational approach for studying DNA shape in solution that has far-reaching implications for studying protein–DNA interactions.

INTRODUCTION

The tumor suppressor protein p53 plays various essential roles in maintaining the integrity of the human genome. Sequence-specific binding of the p53 core DNA-binding domain (DBD) to its response elements (REs) is a key component of the regulation of a large number of signaling pathways (1). The importance of DNA recognition by p53 is highlighted by the fact that >80% of missense mutations of p53 found in human cancers are located within the DBD (2), and many cancer hot-spot mutants have been shown to impair recognition of target DNAs (3).

The p53 REs are defined by two closely spaced decameric half-sites [consensus sequence: 5′-(RRRCWWGYYY)n(RRRCWWGYYY)-3′; R = A,G; W = A,T; Y = C,T; n = spacer of length 0–20 base pairs (bp)], and hundreds of them have been validated in human and mouse (1). The mechanisms by which p53 specifically recognizes its REs have been a long-standing question (1,3). p53 is known to recognize REs using base readout in the major groove, as exemplified by the bidentate hydrogen bonds between Arg280 and the conserved guanines in the CWWG core (3). The importance of DNA shape readout has also been noted: Arg248, the most frequently mutated residue in human cancers, recognizes its DNA target through readout of minor groove geometry and electrostatic potential (4); similarly, another cancer hot-spot residue, Arg273, plays a role in maintaining DNA shape (5).

Intriguingly, several recent crystal structures of tetrameric p53DBDs bound to full REs have revealed various deformations of the bound DNA (4,6–9), suggesting a propensity of DNA conformational change upon formation of the p53/RE complex. However, it remains unclear to what degree the observed DNA deformation may be biased by crystal packing, and more importantly, how inherent variations of the shape of REs impact the mode of conformational change upon p53 binding. Answering these important questions requires a comparison of the bound and unbound RE conformations in solution. The latter is severely lacking—no atomic resolution structure of any unbound p53 RE has yet been reported.

The challenge of deducing DNA conformation in solution is not limited to p53 REs. Current knowledge on sequence-dependent DNA shape, particularly for free DNA, is rather inadequate despite its important role in protein–DNA recognition (10). For instance, sampling of sequence versatility in structure databases is insufficient, with the Dickerson dodecamer accounting for ∼10% of all DNA entries in the Nucleic Acid Database (11), and analyses of short non-coding DNA sequences in several eukaryotic genomes conclude that none of the abundant sequences have had their structures determined (12). These limited experimental data on intrinsic DNA shape is due, in large part, to the difficulty of obtaining unbiased structural information of ‘naked’ DNA. Whereas high-resolution structures of free DNA have been obtained by X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, their number is small compared with available data for protein–DNA complexes (13). In addition, X-ray crystallography studies are hindered by crystal-packing biases, and NMR studies are constrained by the size of the DNA.

Here, we introduce a new experimental/computational pipeline, in which the method of site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) is combined with all-atom Monte Carlo (MC) simulations to derive atomic resolution data representing the sequence-dependent conformation of DNA duplexes in solution. SDSL uses electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to monitor nitroxide radicals (i.e. the spin labels) attached at specific sites of biomolecules, and has matured as a tool for studying the structure and dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids (14,15). The MC simulation technique was shown to enable efficient conformational sampling and was extensively validated using massive experimental data from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy and hydroxyl radical cleavage experiments (13,16). In our new SDSL-MC scheme, a pulsed EPR technique, double-electron-electron-resonance (DEER) (17), is applied to measure distances between nitroxide pairs attached to the target DNA duplex. These distances are then used as constraints to query a large pool of all-atom models generated by MC simulations (18,19), thereby identifying those that conform to the experimental measurements. The SDSL-MC approach is not limited by the size of the DNA or the requirement of crystalline samples, and provides a new method for examining the sequence-dependent shape of DNA in solution.

This work presents studies on two prototypic naturally occurring p53 REs (1): the p21-RE with no spacer (0-bp) between the two half-sites; and the BAX-RE with a 1-bp insertion between the two half-sites (Figure 1A). Using the SDSL-MC approach, conformations of the unbound p21-RE and BAX-RE were determined in solution. Comparing the unbound and bound DNA revealed conformational changes in the central region between the two half-sites on protein binding, which allow formation of key protein–DNA and protein–protein contacts. The modes of conformational change, which differed between the two REs, could be linked to properties that are encoded in the individual nucleotide sequences, suggesting a possible means to achieve binding specificity through sequence-dependent conformational changes.

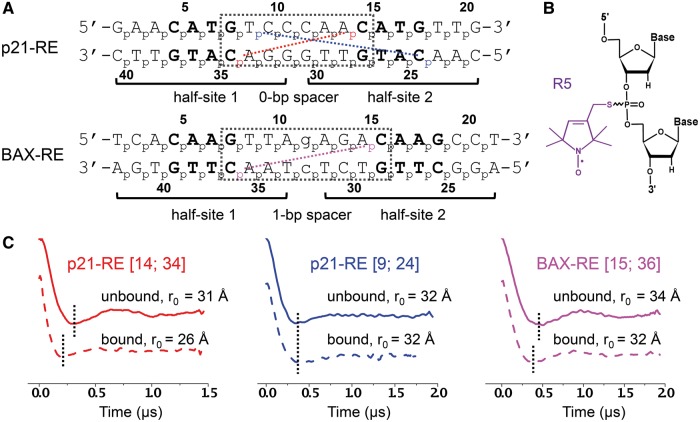

Figure 1.

Experimental design and example DEER results. (A) Nucleotide sequences of the REs. The p21-RE has no spacer between the two half-sites and is located 5′ upstream of the promoter of the CDKN1A gene involved in controlling cell cycle arrest. The BAX-RE has a 1-bp spacer (indicated by the lower-case letter) and is present at the promoter of the Bax gene. For each RE, the numbering scheme of the phosphates is shown next to each strand. The two half-sites are noted, with the CWWG core of each half-site shown in bold and the dotted box marking the central region between the two half-sites. Colored dotted lines and corresponding phosphates designate, as examples, the measured distance sets shown in (C). (B) Chemical configuration of the R5 nitroxide probe. (C) Examples of DEER data. Each data set is designated by the RE and the corresponding labeling sites. DEER spectra measured in the absence (straight line) and presence (dashed line) of p53DBD are shown, with black dotted lines included to aid comparison. See Supplementary Figures S3 and S5 for additional DEER data and analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA spin labeling

DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by solid-phase chemical synthesis (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA). Following previously reported protocols, the R5 spin labels (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline, Figure 1B) were attached to specific DNA sites using the phosphorothioate scheme, and the labeled DNA was purified by HPLC (20). Concentrations of labeled DNA were determined by absorbance at 260 nm. In this work, the Rp and Sp phosphorothioate diastereomers present at each attachment site were not separated. Previous studies using model systems have validated the use of Rp/Sp mixtures in DEER measurement and established an appropriate method for interpreting the measured inter-nitroxide distances (21–23).

EPR sample preparation and DEER spectroscopy measurements of inter-spin distances

EPR samples were prepared following procedures described in (9). Each DEER sample contains 50–100 µM of labeled DNA or p53DBD-DNA complex, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 40% (v/v) glycerol. DEER measurements were carried out at 80 K on a Bruker ELEXSYS E580 X-band spectrometer equipped with a MD4 resonator. Previously reported acquisition parameters and procedures (24) were used. Inter-spin distance distributions were computed from the resulting dipolar evolution data using DEERanalysis2011 (25). From these distance distribution profiles, the average distance (r0) and the width of distance distribution (σ) were calculated as reported previously (21). Repeated measurements indicated that errors in the measured r0 are less than 1 Å.

Generation of DNA models using Monte Carlo simulations

A previously published protocol was used to generate an MC ensemble of all-atom DNA models with sequence-dependent shape (18,26). Simulations started from idealized B-DNA structures generated without any sequence-dependent structural features. The MC sampling was based on collective and internal degrees of freedom using the AMBER force field implemented as previously described (18,26), an analytic chain closure with associated Jacobians (19) and explicit sodium counter ions combined with an implicit solvent description (27). MC sampling was performed >1 million cycles with random conformational changes of all degrees of freedom in each cycle. All-atom structures were recorded every 100 MC cycles, forming an MC ensemble of 10 000 structures for each simulation.

Computation of expected inter-R5 distances

Our previously validated NASNOX program (20,22) was used to calculate expected inter-R5 distances (rmodel). Briefly, with each DNA model, the program modeled R5 at the target site, then identified sterically allowed R5 conformers using the following search parameters [see (20) for details on these parameters]: t1 steps: 3; t2 steps: 6; t3 steps: 6; fine search: on; t1 starting values: 180°; t2 starting values: 180°; t3 starting values: 180°; and no additional conformer search criterion. Searches were carried out separately for the Rp and Sp diastereomers (i.e. R5 attached to the O1P or O2P atom), and the results were combined to yield the ensemble of allowable R5 conformers at the given labeling site. The rmodel between two-specific labeling sites was then calculated by averaging all inter-R5 distances between the two corresponding R5 ensembles. Controls showed that varying the search parameters resulted in <1 Å difference in rmodel.

For the bound REs, expected inter-R5 distances (rcrystal) were computed based on the reported crystal structures: PDB ID 3TS8 for the p21-RE (8); and 4HJE for the BAX-RE (9). A modified version of the NASNOX program was used to account for the presence of protein atoms.

Characterization of DNA duplex models

For a given model j of a DNA duplex, we defined a scoring function Pt as:

| (1) |

where i designates a particular distance in the DNA duplex, rmodel-j is the NASNOX computed expected distance for the model j, r0 is the DEER measured average distance and σ is the measured distance distribution width. Heavy atom root-mean-square-deviations between DNA models (RMSDstruct) were calculated using the program VMD (28). Calculations included, unless otherwise stated, only the interior of the duplex and excluded two base-pairs at either terminus. DNA structural parameters were calculated using CURVES (29).

RESULTS

DEER-measured distances reveal that p53DBD binding induces RE conformational changes

To examine the conformation of REs, a pair of R5 probes (Figure 1B) were attached at specific DNA sites using a previously established phosphorothioate scheme (20,21), and inter-R5 distances were measured by DEER. Each measured distance was designated by the corresponding labeling site numbers, for example, data sets [14; 34] in p21-RE represents the distance measured with a pair of R5 attached to the phosphorothioates of nucleotides C14 and C34 (Figure 1A). For all double labeled REs, the measured dipolar evolution traces showed an oscillating decay pattern (see Figure 1C for examples), from which the inter-R5 distances were determined. Control measurements on single-labeled REs gave flat traces (Supplementary Figure S1), thus ensuring that the distances measured in the double-labeled DNA were not biased by spin interactions due to undesired sample aggregation. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that R5 did not significantly distort the DNA duplex, and the measured distances accurately reported on the native structure (21,22,30).

We measured multiple distances in REs in the absence and presence of p53DBD to examine protein-induced DNA conformational changes. In these measurements, we chose labeling sites with minimal perturbation to p53 binding and we confirmed p53DBD-DNA complex formation by gel shift assays (Supplementary Figure S2). For the p21-RE, 2 of the 6 data sets, [14; 34] (Figure 1C) and [13; 34] (Supplementary Figure S3D), showed clear differences in the measured echo evolution traces on p53DBD binding. The differences in r0 between the unbound and bound DNA were 5 Å and 3 Å, respectively (Supplementary Table S1), which are well beyond the error of r0 measurements (±1 Å). In addition, control studies indicated that changes in R5 conformers on p53DBD binding were minimal and were unlikely to account for the observed r0 changes (Supplementary Figure S4). As such, distance changes observed in data sets [14; 34] and [13; 34] clearly revealed p21-RE conformational changes on p53DBD binding. On the other hand, the remaining four datasets, including [9; 24] shown in Figure 1C, gave superimposable dipolar evolution traces in the absence and presence of p53DBD, resulting in little or no changes in r0 (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Figure S3D).

For the BAX-RE, 10 sets of distances were measured in unbound and bound DNA (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Figure S5). Interestingly, the observed distance changes were much smaller than those observed for the p21-RE. The only noticeable distance changes were from data sets [15; 36] (Figure 1C) and [14; 36] (Supplementary Figure S5D), both at 2 Å, whereas the remaining 8 data sets showed little or no changes in r0 (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Figure S5D).

Overall, in both the p21- and BAX-RE, p53 induced distance changes were detected by DEER, thus unambiguously revealing RE conformational changes on interacting with p53. However, with the presence of both variable and invariable distances, it was difficult to intuitively deduce the mode of RE conformational changes, even though crystal structures of both bound DNAs were available (8,9). This motivated us to ‘solve’ the conformation of the unbound REs in solution.

Conformations of unbound REs in solution

To obtain all-atom models of unbound REs, we implemented a strategy that has been successfully used in SDSL mapping of an RNA junction (24), namely, to use the DEER measured distances to select sterically acceptable models from a large pool of 3D structures. In our approach, these structures were generated by unrestrained MC simulations (18). For each structural model, the NASNOX program (20) was used to select sterically allowed R5 conformers at the respective labeling sites, from which the relevant average inter-R5 distances (rmodel) were obtained. We then computed a scoring function Pt for each model (Equation 1, ‘Materials and Methods’ section), taking into account the measured and predicted average distances (r0 and rmodel) and the width of the measured distance distribution (σ). Pt represents, under the assumption of an idealized normal distribution, the effective probability of a given set of rmodel values that match the corresponding r0 values, with a perfect match resulting in a maximum Pt score of 1.

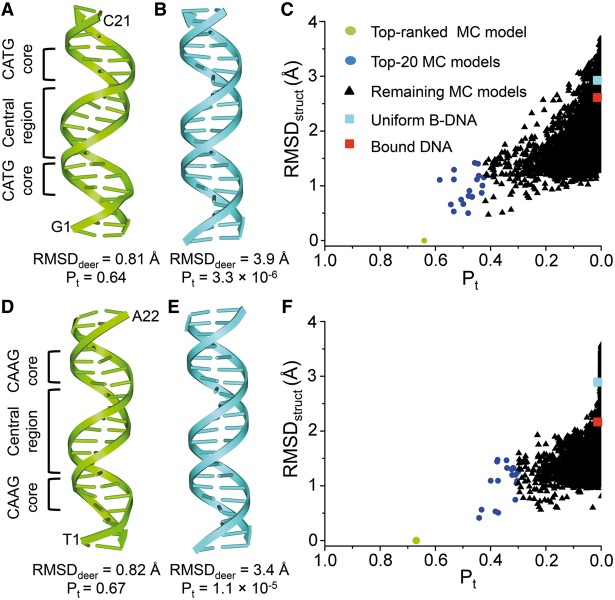

For the p21-RE, we used 16 sets of DEER-measured distance (Supplementary Figure S3, Supplementary Table S2) to compute Pt for a pool of 10 000 models obtained from 1 million MC cycles. The top-ranked model had a Pt score of 0.64 (Figure 2A, Supplementary Table S2), corresponding to on average a 97% probability of matching each rmodel to the corresponding r0 (0.9716 ≈ 0.64). For this top-ranked model, the root-mean-square-deviation between rmodel and r0 (RMSDdeer) was 0.81 Å, and the largest difference between a corresponding set of r0 and rmodel was 1.8 Å (Supplementary Table S2). Given that r0 and rmodel each might incur errors of ±1 Å, differences below 2 Å were deemed insignificant. The results indicated that the top-ranked MC model satisfies all the measured distances.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the unbound p21-RE (A–C) and BAX-RE (D-F). (A) Top-ranked MC model of the unbound p21-RE. (B) Uniform 20-bp B-DNA model constructed with a standard set of base-pair parameters (Helix twist: 35.9°; X-displacement; −0.66 Å; and C2’-endo sugar pucker). (C) Data mining of MC-generated unbound p21-RE models using EPR-derived distances. X-axis: Pt computed based on 16 measured distances in the unbound p21-RE duplex. Y-axis: RMSDstruct computed against the top-ranked MC model. Data points corresponding to uniform B-DNA (cyan) and bound DNA from PDB ID 3TS8 (red) are also included. (D) Top-ranked MC model of the unbound BAX-RE. (E) Uniform 21-bp B-DNA model. (F) Data mining of MC-generated unbound BAX-RE models using 18 EPR-measured distances. All color codes are the same as those in (C), except that the bound DNA data point (red) was obtained using PDB ID 4HJE.

To characterize variations in EPR-derived p21-RE models, we adopted a commonly used approach in NMR studies and further analyzed the 20 MC models with the highest Pt scores. The pairwise RMSDstruct among this top-20 ensemble was (1.0 ± 0.3) Å (average ± standard deviation, same below). This suggested that models that conformed to the measured distances were structurally similar (Supplementary Figure S6). In addition, we carried out a search using only 14 of the 16 measured distances, which yielded the same top-ranked model and a similar top-20 ensemble (Supplementary Table S3). Overall, the data indicated that within the resolution of the method, the 16 measured distances were sufficient to identify a set of all-atom MC models with convergent conformations.

We also examined models of generic B- and A-form duplexes built with identical helical parameters (Figure 2B and Supplementary Table S2), which therefore exhibited uniform shapes without sequence-dependent characteristics. As expected, a uniform 20-bp A-form duplex, which drastically differed from the top-ranked p21-RE model with an RMSDstruct of 5.0 Å, fitted poorly to the measured distances (Pt = 1.0 × 10−17; RMSDdeer = 8.5 Å) (Supplementary Table S2). More importantly, a uniform 20-bp B-form duplex (Figure 2B) also yielded a low Pt score (3.3 × 10−6) and a high RMSDdeer value of 3.9 Å (Supplementary Table S2), indicating that this generic B-DNA did not conform to distances measured for the p21-RE. The generic B-DNA had an RMSDstruct of 2.9 Å when compared with the top-ranked p21-RE model, which was larger than the variation among the top-20 EPR-derived models (Figure 2C). Therefore, the 16 sets of distances yielded a converged conformation of the unbound p21-RE with a sequence-dependent shape.

Using the SDSL-MC approach, we also obtained all-atom models for the unbound BAX-RE with 18 sets of measured distances (Supplementary Figure S5, Supplementary Table S4). The top-ranked BAX-RE model (Figure 2D) had a Pt score of 0.67 (Supplementary Table S4), i.e. an average 98% probability of matching each rmodel to the corresponding r0. This top-ranked MC model again differed from a 21-bp generic B-form duplex (Figure 2E) and satisfied all the DEER measured distances (Supplementary Table S4). In addition, the pair-wise RMSDstruct among the top-20 BAX-RE models was (1.0 ± 0.3) Å, indicating a high degree of structural similarity (Supplementary Figure S6). Furthermore, control studies showed that the use of 18 sets of distances was sufficient to identify a set of all-atom models with convergent conformations for the unbound BAX-RE (Supplementary Table S5).

Assessing p53DBD bound RE conformations in solution

To evaluate the bound RE conformation in solution, we compared the expected average inter-R5 distances based on the crystal structures (rcrystal) with the corresponding DEER measured r0 values (Supplemental Table S6). For the p21-RE, the four distances spanning the central region between the two CATG cores showed differences ranging between −1.4 and 1.0 Å, which were within the variability range of 2 Å in our measurements. This indicated that within the resolution accessible to our method, the crystal structure of the bound p21-RE central region accurately reflected its conformation in solution. The same conclusion has also been previously drawn regarding the central region of the bound BAX-RE (9) (see also Supplementary Table S6).

Despite the general agreement observed at the central region, four equivalent distances, each one measured across one of the four CWWG cores presented in the p21- and BAX-RE, showed that the measured r0 values exceeded the corresponding rcrystal by 2.9–5.0 Å (Supplementary Table S6). In these measurements, DNA-p53DBD complex formation was confirmed (Supplementary Figure S2), although r0 did not change upon p53DBD binding (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, these r0 values were substantially larger than the corresponding rcrystal distances obtained from other crystal structures (4–6). Taken together, the data indicated that in solution the CWWG core conformation in the bound REs likely differed from conformations captured in the crystal (see ‘Discussion’). At this point, however, extensive protein–DNA contacts involved in the CWWG regions severely limited our ability to measure informative distances to derive an EPR-based model, and bound conformations of the CWWG core regions of the REs could not be deduced with certainty.

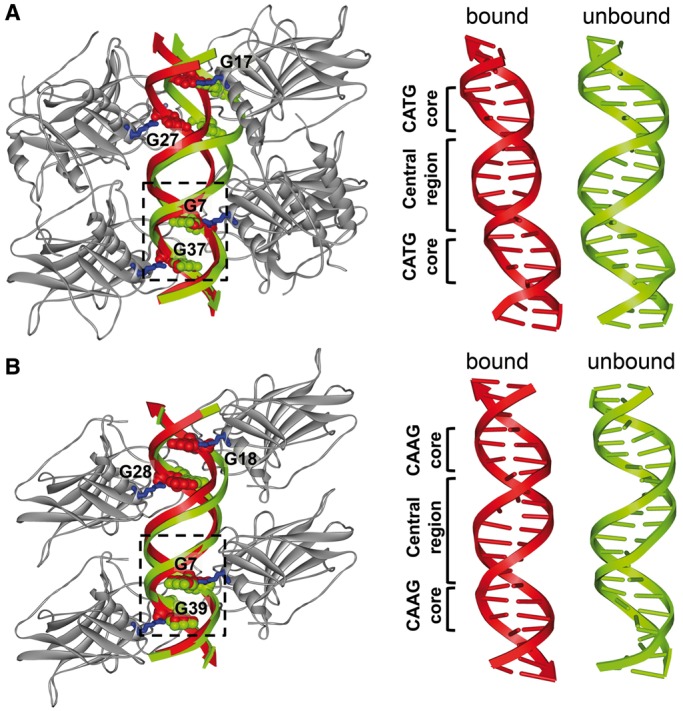

Distinct conformational changes at the central region of the REs on p53DBD binding

The unbound p21-RE conformation derived from the EPR-MC pipeline differed from the bound DNA reported in the crystal structure with an RMSDstruct of 2.6 Å, which was beyond variations among the top-20 models (Figure 2C, Supplementary Figure S7A). We modeled the unbound DNAs into the tetrameric complex by aligning half-site 1 (i.e. nucleotides A3-C10/G31-T38; Figure 1A). This half-site could be aligned reasonably well between the bound and unbound DNAs, with an RMSD of 1.4 Å between heavy atoms of the aligned nucleotides (Figure 3A). However, with half-site 1 aligned, the bound and unbound DNAs deviated at half-site 2 (i.e. C11–T18/A23–G30) with an RMSD of 8.4 Å (Figure 3A). Apparently, if the protein tetramer were maintained, the unbound DNA conformation would not allow proper protein–DNA contacts (e.g. R280 to G7, G17, G27 and G37, Figure 3A) to form simultaneously at both half-sites. This likely caused a deformation at the central region of the bound p21-RE, resulting in a previously noted displacement between the helix axes of the two half-sites (Supplementary Figure S8) (8).

Figure 3.

Conformational changes in REs upon p53 binding. In each panel, shown on the left is the superimposition of the SDSL-MC-derived unbound RE onto the corresponding co-crystal structure of the complex, with the blue sticks representing the Arg280 residues; and the CPK representation denoting the G7, G17, G27 and G37 nucleotides in the RE. Shown on the right are schematic representations of the bound and unbound REs. (A) p21-RE, with DNAs aligned at nucleotides A3-C10/G31-T38 (dashed box). In this work, the p53 construct included only the wild-type DBD, whereas the co-crystal structure of the complex (PDB ID 3TS8) included the DBD covalently linked to the oligomerization domain without the wild-type linker present, but with mutations in both domains (7,8). (B) BAX-RE, with the DNAs aligned at nucleotides A3-A10/T33-T40 (dashed box).

For the BAX-RE, the RMSDstruct between the unbound and bound DNA was 2.1 Å (Figure 2F). This is smaller than that of the p21-RE, and indicated that the BAX-RE underwent a more subtle p53-induced conformational change (Figure 3). When we aligned the unbound and bound BAX-RE based on half-site 1 (i.e. nucleotides A3-A10/T33-T40), the bound DNA was superimposed by the ensemble of top-20 unbound RE models (Supplementary Figure S7B), and half-site 2 (i.e. nucleotides A12-C19/G24-T31) of the top-ranked unbound BAX-RE deviated from the corresponding segment of the bound DNA with an RMSD of 3.9 Å (Figure 3B). These observations were consistent with the small distance changes observed at the central region of BAX-RE on p53 binding (Supplementary Table S1), and might suggest that the unbound BAX-RE was poised to interact with the p53 tetramer due to its sequence-dependent shape (Figure 3B). Most noticeably, for the 9-bp central region spanning G7/C36 and C15/G28 (Figure 1A), the unbound BAX-RE was under-wound by ∼15° compared with a generic B-DNA. This facilitated the transition into the p53 bound form, in which further unwinding at the central region has been observed (9).

DISCUSSION

We established a new SDSL-MC approach to study conformations of two prototypic p53 REs in solution. The unbound RE conformations, obtained using multiple measured nanometer distances as constraints, were within the B-DNA family while exhibiting sequence-dependent structural properties distinct from a uniform B-DNA. In both REs, p53-induced DNA deformations were detected at the central region between the two half-sites. The results indicate that sequence-dependent shapes of the unbound RE influence the mode of DNA conformational changes upon interacting with p53, which thereby may serve as a mechanism to achieve p53-RE binding specificity.

Sequence-dependent conformational changes of REs on p53DBD binding

Previous biochemical and computational studies have suggested changes of RE conformations upon p53 binding (31–33). However, the molecular details of the DNA conformational changes and their relationship to individual RE sequences remained rather unclear. Earlier work suggested that the bound REs undergo bending at the CWWG region (31). However, recent structural (4–9) and biochemical (33) studies of p53DBD bound REs showed generally rather small bending. Instead, in a number of crystal structures, deviations from canonical B-DNA characteristics were noted at a confined location between the two half-sites (i.e. the central region) (4,6–9).

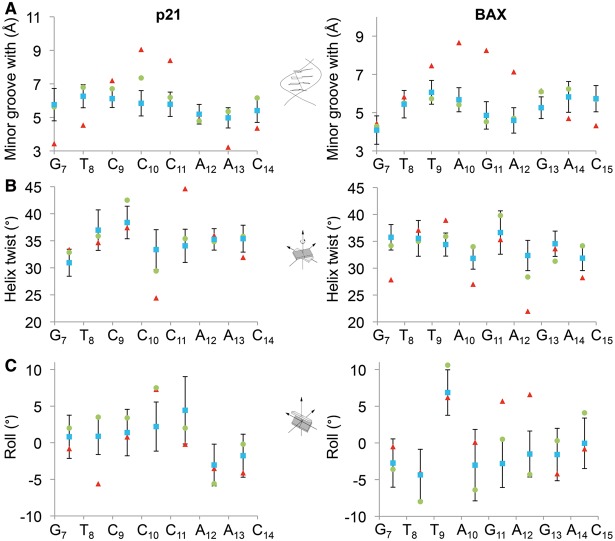

In this work, SDSL measured distances unambiguously demonstrated that in solution p53DBD binding induces conformational changes at the central region of the p21- and BAX-RE (Figure 1C, Supplementary Table S1). Perhaps unexpectedly, the degree of p53 induced DNA alteration was more subtle in the 1-bp-spacer BAX-RE as compared with that in the 0-bp-spacer p21-RE (Figure 3), whereas the p53DBD bound complexes exhibited a similar tetrameric scaffold for both REs (9). This provides a hint that sequence-dependent structural properties encoded in a particular DNA target are exploited by p53 to achieve the energetically most favorable mode of deformation. This hypothesis is further supported by structural analyses of unbound REs, which were enabled by the all-atom models provided by the new SDSL-MC method. The analyses revealed RE shape variations and suggested tangible connections between structural features in the unbound and bound DNA (Figure 4). For the BAX-RE, larger positive Roll of the T9pA10 base pair step was already apparent in the unbound DNA (Figure 4C). Such intrinsic property of the TpA step facilitated widening of the minor groove (10), which was observed in the bound form (Figure 4A). In addition, the unbound BAX-RE was under-wound at the central region (Figures 3B and 4), thus facilitating further unwinding to accommodate the 9-bp central region into the same volume occupied by 8 bp in other REs with 0-bp spacers (9). On the other hand, in the unbound p21-RE the relative positioning of the two CWWG cores deviated significantly from the bound form, necessitating a shift of the helix axis at a ‘hinge’ located at the interface between two half-sites (Figure 3). Further analyses indicated that conformational changes at the central region of the REs occurred to facilitate proper protein–DNA interactions, while at the same time maintaining the intra- and inter-dimer protein contacts (Figure 3). As the collective protein–DNA and protein–protein contacts give rise to cooperative binding, sequence-dependent conformational changes at the central region of REs thus may modulate cooperativity in p53-RE interactions, thereby contributing to specific RE recognition.

Figure 4.

Analyses of p53 RE structures. The DNA shape parameters (A) minor groove width, (B) helix twist and (C) roll are shown for the p21-RE (left panel) and the BAX-RE (right panel). Structural features were derived from the crystal structures of the complexes (red), the top-ranked MC models (green) and the averages of the top-20 MC models (blue). The error bars indicate the standard deviations of structural parameters among the top-20 models, demonstrating an efficient conformational sampling. The structural parameters indicate that the conformations observed in the crystal structures of the bound forms were partially apparent in the intrinsic DNA shape of the unbound forms. Examples for this observation are the low helix twist values at the C10pC11 step of the p21-RE and the A10pG11 step of the BAX-RE, as well as the negative Roll at the A12pA13 step of the p21-RE and the positive Roll at the T9pA10 step of the BAX-RE.

For both bound p21- and BAX-RE, the SDSL data indicated that solution-state conformations of the CWWG cores deviated to a certain degree compared with the corresponding crystal structures despite the good agreement in the central regions (Supplementary Table S6). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that this discrepancy might be due to the fact that the CWWG cores and the central region were differentially impacted by differences in experimental conditions (e.g. frozen solution versus crystal; difference in constructs, see Figure 3 caption), the SDSL data may also reflect an intrinsic variability of the CWWG core as suggested by previous studies (4–6,9,31,33). In particularly, the ApT steps within the CWWG cores have been reported in either Watson–Crick (6) or Hoogsteen configuration (4). Transitions between Watson–Crick and Hoogsteen geometry, which are associated with base flipping (34), may account for the longer distances measured in solution as reported here. Furthermore, whereas p53DBD binding induced a larger degree of deformation at the central region of p21-RE as compared with that of the BAX-RE, the p21-RE is known to bind tighter to p53 (35). One of the possible explanations for this apparently puzzling observation is that the respective CWWG cores responded differently to p53 binding. Further investigation of the CWWG core, particularly in the bound state, is therefore required.

Finally, p53/DNA interactions can be impacted by regions beyond the DBD and RE (3). Whereas biophysical studies focusing on folded p53 fragments have provided a wealth of information regarding p53 structure and function, expanding beyond these ‘truncated’ systems is highly desirable. The SDSL-MC approach, which is capable of providing molecular details in large non-crystalline complexes, is particularly suited for these studies.

Mapping sequence-dependent DNA shape using the SDSL-MC approach

Whereas early SDSL studies used DNA duplexes as model systems (21,36,37), recent reports have emerged in which SDSL measured distances were used to study DNA duplex conformation in response to base lesion (38), mismatches (39) and protein binding (40). In addition, SDSL has also been used to study higher order DNA structures such as quadruplexes (41) and four-way junctions (42). In this work, using the R5 probe that can be attached to any nucleotide within a target sequence, multiple distances were readily measured, and they directly revealed conformational changes between the bound and unbound DNA. In addition, synergistic integration with MC sampling allowed us to derive atomic models of the target DNA with sequence-dependent shape. In each top-20 ensemble of unbound REs, the models are: (i) structurally highly similar; and (ii) clearly different from a uniform B-DNA (Figures 2 and 4). This demonstrates that the SDSL-MC pipeline has the ability to provide detailed structural information of DNA duplexes. The bound p21-RE structure differed from the top-ranked model of the unbound DNA by an RMSDstruct of 2.6 Å and from uniform B-DNA by only 1.8 Å. As such, obtaining the sequence-dependent shape of the unbound DNA has a profound impact on properly assessing protein induced deformations of DNA targets. Furthermore, intrinsic DNA shape features revealed by the SDSL-MC approach will benefit a broad range of efforts, such as prediction of transcription factor binding specificities based on regression models that combine DNA sequence and shape (43–45).

Nevertheless, further studies are needed to explore the utility and limitation of the SDSL-MC method. For example, the ‘resolution’ that can be achieved by this approach remains to be investigated. In addition, DEER measures distances in a frozen solution state, whereas MC simulations target solution-state equilibrium at ambient temperature. It is not clear how unique aspects of each methodology impact the interpretation of the resulting DNA shape.

In summary, results reported here clearly demonstrate that the SDSL-MC approach reveals sequence-dependent shapes of p53 REs that advance our understanding of p53/DNA recognition. The method is not limited by the size of the system and allows parallel examination of DNA shape in both the unbound and protein-bound states. This is a step forward toward uncovering the role of intrinsic DNA shape on protein–DNA recognition on a general basis.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

NIH [GM069557 and RR028992 (to P.Z.Q.); U01GM103804 and R01HG003008 (in part to R.R.); and R01GM064642 and 2U54RR022220 (to L.C.)]; and NSF [MCB-0546529 and CHE-1213673 (to P.Z.Q.)]. Funding for open access charge: NSF, NIH.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank I. Haworth for the continued development of the NASNOX program. R.R. is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow. See Supplementary Data for detailed author contributions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine A. Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:402–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, Ishioka C, Tavtigian SV, Hainaut P, Olivier M. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:622–629. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joerger AC, Fersht AR. The Tumor Suppressor p53: From Structures to Drug Discovery. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000919. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitayner M, Rozenberg H, Rohs R, Suad O, Rabinovich D, Honig B, Shakked Z. Diversity in DNA recognition by p53 revealed by crystal structures with Hoogsteen base pairs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:423–429. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eldar A, Rozenberg H, Diskin-Posner Y, Rohs R, Shakked Z. Structural studies of p53 inactivation by DNA-contact mutations and its rescue by suppressor mutations via alternative protein-DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:8748–8759. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Dey R, Chen L. Crystal structure of the p53 core domain bound to a full consensus site as a self-assembled tetramer. Structure. 2010;18:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petty TJ, Emamzadah S, Costantino L, Petkova I, Stavridi ES, Saven JG, Vauthey E, Halazonetis TD. An induced fit mechanism regulates p53 DNA binding kinetics to confer sequence specificity. EMBO J. 2011;30:2167–2176. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emamzadah S, Tropia L, Halazonetis TD. Crystal Structure of a Multidomain Human p53 Tetramer Bound to the Natural CDKN1A (p21) p53-Response Element. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011;9:1493–1499. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Zhang X, Dantas Machado AC, Ding Y, Chen Z, Qin PZ, Rohs R, Chen L. Structure of p53 binding to the BAX response element reveals DNA unwinding and compression to accommodate base-pair insertion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:8368–8376. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohs R, West SM, Sosinsky A, Liu P, Mann RS, Honig B. The role of DNA shape in protein-DNA recognition. Nature. 2009;461:1248–1253. doi: 10.1038/nature08473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egli M, Pallan PS. The many twists and turns of DNA: template, telomere, tool, and target. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subirana JA, Messeguer X. The most frequent short sequences in non-coding DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1172–1181. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou T, Yang L, Lu Y, Dror I, Dantas Machado AC, Ghane T, Di Felice R, Rohs R. DNAshape: a method for the high-throughput prediction of DNA structural features on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W56–W62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fanucci GE, Cafiso DS. Recent Advances and applications of site-directed spin labeling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sowa GZ, Qin PZ. Site-directed spin labeling studies on nucleic acid structure and dynamics. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 2008;82:147–197. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)00005-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop EP, Rohs R, Parker SC, West SM, Liu P, Mann RS, Honig B, Tullius TD. A map of minor groove shape and electrostatic potential from hydroxyl radical cleavage patterns of DNA. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:1314–1320. doi: 10.1021/cb200155t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiemann O, Prisner TF. Long-range distance determinations in biomacromolecules by EPR spectroscopy. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2007;40:1–53. doi: 10.1017/S003358350700460X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohs R, Sklenar H, Shakked Z. Structural and energetic origins of sequence-specific DNA bending: Monte Carlo simulations of papillomavirus E2-DNA binding sites. Structure. 2005;13:1499–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sklenar H, Wüstner D, Rohs R. Using internal and collective variables in Monte Carlo simulations of nucleic acid structures: chain breakage/closure algorithm and associated Jacobians. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;27:309–315. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin PZ, Haworth IS, Cai Q, Kusnetzow AK, Grant GPG, Price EA, Sowa GZ, Popova A, Herreros B, He H. Measuring nanometer distances in nucleic acids using a sequence-independent nitroxide probe. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2354–2365. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai Q, Kusnetzow AK, Hubbell WL, Haworth IS, Gacho GPC, Van Eps N, Hideg K, Chambers EJ, Qin PZ. Site-directed spin labeling measurements of nanometer distances in nucleic acids using a sequence-independent nitroxide probe. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4722–4734. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price EA, Sutch BT, Cai Q, Qin PZ, Haworth IS. Computation of nitroxide-nitroxide distances in spin-labeled DNA duplexes. Biopolymers. 2007;87:40–50. doi: 10.1002/bip.20769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai Q, Kusnetzow AK, Hideg K, Price EA, Haworth IS, Qin PZ. Nanometer Distance Measurements in RNA Using Site-Directed Spin Labeling. Biophys. J. 2007;93:2110–2117. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.109439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Tung C-S, Sowa GZ, Hatmal MMM, Haworth IS, Qin PZ. Global structure of a three-way junction in a phi29 packaging RNA dimer determined using site-directed spin labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2644–2652. doi: 10.1021/ja2093647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeschke G, Chechik V, Ionita P, Godt A, Zimmermann H, Banham J, Timmel C, Hilger D, Jung H. DeerAnalysis2006—a comprehensive software package for analyzing pulsed ELDOR data. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2006;30:473–498. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohs R, Bloch I, Sklenar H, Shakked Z. Molecular flexibility in ab initio drug docking to DNA: binding-site and binding-mode transitions in all-atom Monte Carlo simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:7048–7057. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohs R, Etchebest C, Lavery R. Unraveling proteins: a molecular mechanics study. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2760–2768. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77429-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavery R, Sklenar H. Defining the structure of irregular nucleic acids: conventions and principles. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1989;6:655–667. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1989.10507728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popova AM, Kálai T, Hideg K, Qin PZ. Site-specific DNA structural and dynamic features revealed by nucleotide-independent nitroxide probes. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8540–8550. doi: 10.1021/bi900860w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagaich AK, Zhurkin VB, Durell SR, Jernigan RL, Appella E, Harrington RE. p53-induced DNA bending and twisting: p53 tetramer binds on the outer side of a DNA loop and increases DNA twisting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1875–1880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan Y, Nussinov R. p53-Induced DNA bending: the interplay between p53-DNA and p53-p53 interactions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:6716–6724. doi: 10.1021/jp800680w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beno I, Rosenthal K, Levitine M, Shaulov L, Haran TE. Sequence-dependent cooperative binding of p53 to DNA targets and its relationship to the structural properties of the DNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1919–1932. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honig B, Rohs R. Biophysics: flipping Watson and Crick. Nature. 2011;470:472–473. doi: 10.1038/470472a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinberg RL, Veprintsev DB, Bycroft M, Fersht AR. Comparative binding of p53 to its promoter and DNA recognition elements. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ward R, Keeble DJ, El-Mkami H, Norman DG. Distance determination in heterogeneous DNA model systems by pulsed EPR. Chembiochem. 2007;8:1957–1964. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiemann O, Cekan P, Margraf D, Prisner TF, Sigurdsson ST. Relative orientation of rigid nitroxides by PELDOR: beyond distance measurements in nucleic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:3292–3295. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sicoli G, Mathis G, Aci-Seche S, Saint-Pierre C, Boulard Y, Gasparutto D, Gambarelli S. Lesion-induced DNA weak structural changes detected by pulsed EPR spectroscopy combined with site-directed spin labelling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3165–3176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wunnicke D, Ding P, Seela F, Steinhoff H-J. Site-directed spin labeling of DNA reveals mismatch-induced nanometer distance changes between flanking nucleotides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:4118–4123. doi: 10.1021/jp212421c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reginsson GW, Shelke SA, Rouillon C, White MF, Sigurdsson ST, Schiemann O. Protein-induced changes in DNA structure and dynamics observed with noncovalent site-directed spin labeling and PELDOR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh V, Azarkh M, Exner TE, Hartig JS, Drescher M. Human telomeric quadruplex conformations studied by pulsed EPR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:9728–9730. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeman ADJ, Ward R, El Mkami H, Lilley DMJ, Norman DG. Analysis of Conformational Changes in the DNA Junction-Resolving Enzyme T7 Endonuclease I on Binding a Four-Way Junction Using EPR. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9963–9972. doi: 10.1021/bi2011898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordân R, Shen N, Dror I, Zhou T, Horton J, Rohs R, Bulyk ML. Genomic regions flanking E-box binding sites influence DNA binding specificity of bHLH transcription factors through DNA shape. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1093–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dror I, Zhou T, Mandel-Gutfreund Y, Rohs R. Covariation between homeodomain transcription factors and the shape of their DNA binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:430–441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang L, Zhou T, Dror I, Mathelier A, Wasserman WW, Gordân R, Rohs R. TFBSshape: a motif database for DNA shape features of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D148–D155. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.