Significance

The identification of molecular subtype heterogeneity in breast cancer has allowed a deeper understanding of breast cancer biology. We present evidence that there are two intrinsic subtypes of high-grade bladder cancer, basal-like and luminal, which reflect the hallmarks of breast biology. Moreover, we have developed an accurate gene set predictor of molecular subtype, the BASE47, that should allow the incorporation of subtype stratification into clinical trials. Further clinical, etiologic, and therapeutic response associations will be of interest in future investigations.

Abstract

We sought to define whether there are intrinsic molecular subtypes of high-grade bladder cancer. Consensus clustering performed on gene expression data from a meta-dataset of high-grade, muscle-invasive bladder tumors identified two intrinsic, molecular subsets of high-grade bladder cancer, termed “luminal” and “basal-like,” which have characteristics of different stages of urothelial differentiation, reflect the luminal and basal-like molecular subtypes of breast cancer, and have clinically meaningful differences in outcome. A gene set predictor, bladder cancer analysis of subtypes by gene expression (BASE47) was defined by prediction analysis of microarrays (PAM) and accurately classifies the subtypes. Our data demonstrate that there are at least two molecularly and clinically distinct subtypes of high-grade bladder cancer and validate the BASE47 as a subtype predictor. Future studies exploring the predictive value of the BASE47 subtypes for standard of care bladder cancer therapies, as well as novel subtype-specific therapies, will be of interest.

In the United States, urothelial carcinoma (UC) of the bladder is the fourth most common malignancy in men and the ninth most common in women, with 72,570 new cases and 15,210 deaths expected in 2013 (1). Bladder cancer is heterogeneous and can be histologically divided into low-grade and high-grade disease. Whereas low-grade tumors are almost invariably noninvasive (Ta), high-grade tumors can be classified based on invasion into the muscularis propria of the bladder, as non–muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC; Tis, Ta, T1) or muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC; ≥T2). Low-grade tumors are associated with a high rate of recurrence but an excellent overall prognosis, with a 5-y survival in the range of 90%. In contrast, high-grade MIBC has a relatively poor 5-y overall survival, 68% for T2 and decreasing to 15% for non–organ-confined disease (i.e., pT3 and pT4) (1, 2).

Along with divergent pathologies and prognosis, low-grade and high-grade UCs are associated with distinct genetic alterations. For example, low-grade UCs are enriched for activating mutations in fibroblast growth factor 3 (FGFR3), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), and inactivating lysine (K)-specific demethylase 6A (KDM6A) mutations, whereas high-grade, muscle-invasive tumors are enriched for tumor protein p53 (TP53) and retinoblastoma 1 (RB1) pathway alterations (3–10).

Several reports have examined the gene expression profiles of primary bladder tumors. From these studies, it is apparent that low-grade noninvasive and high-grade muscle-invasive tumors harbor distinct gene expression patterns, and that further molecular subsets can be identified within low-grade and high-grade tumors (5, 11–14). Moreover, a number of gene signatures have been developed that can predict tumor stage, lymph node metastases, and bladder cancer progression (11–13, 15–18). There are established gene expression patterns that differentiate low-grade and high-grade tumors; however, there are little data identifying intrinsic subtypes specifically within high-grade disease. We have identified two intrinsic molecular subsets of high-grade bladder cancer, termed “luminal” and “basal-like,” with differences in clinical outcome. In addition, we have developed a 47-gene predictor, bladder cancer analysis of subtypes by expression (BASE47), which can accurately classify high-grade UCs into luminal and basal-like tumors. The molecular subtypes appear to reflect different stages of urothelial differentiation and strikingly recapitulate aspects of breast cancer biology, including a claudin-low subtype.

Results

Consensus Clustering Reveals Two Distinct Molecular Subtypes of High-Grade Bladder Cancer.

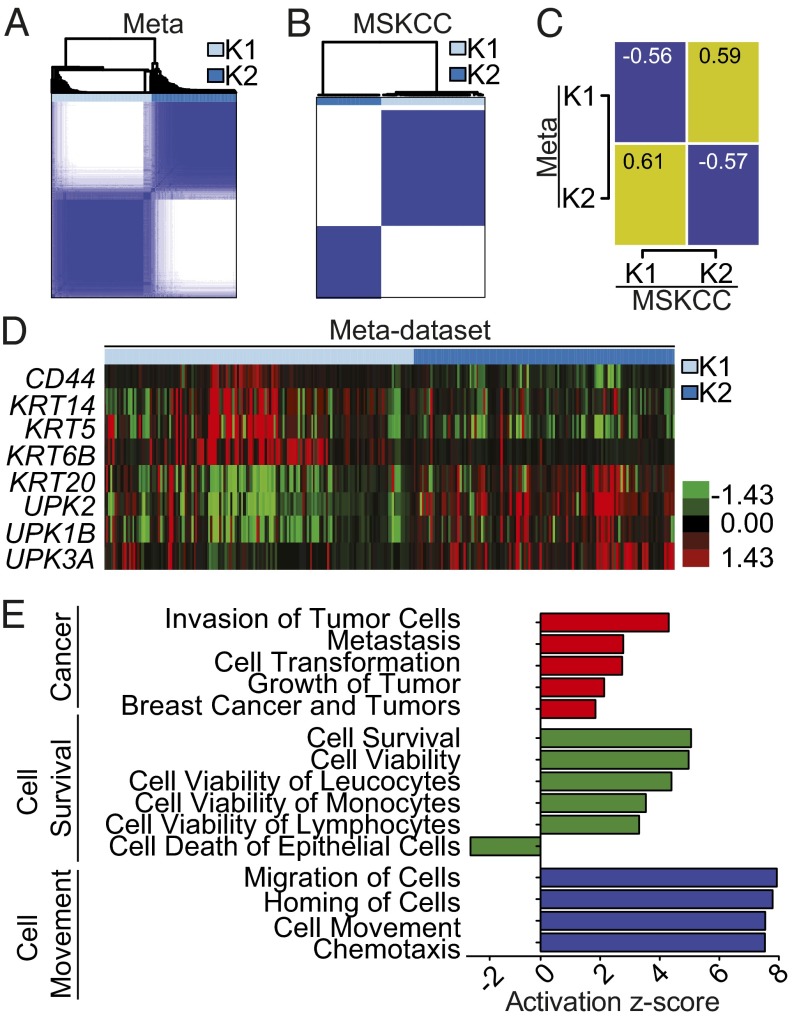

Previous studies examining the gene expression changes associated with bladder cancer have assessed both low-grade and high-grade tumors in aggregate (5, 11–13, 19, 20). In the present study, we looked exclusively for intrinsic subtypes of high-grade disease agnostic to clinical stage or outcome. We first created a meta-dataset of 262 high-grade muscle-invasive tumors, curated from four publically available datasets (12, 19–21) (SI Appendix, Table S1). In parallel, an independent set of 49 high-grade tumors from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) served as a validation set (8). In both the meta-dataset and the MSKCC dataset, consensus clustering identified two groups (designated K1 and K2) as the optimal number of molecular subtypes, as defined by the criterion of subclass stability (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B).

Fig. 1.

Consensus clustering defines two distinct molecular subtypes of MIBC. (A) Consensus clustering was performed on 262 muscle-invasive tumors curated from four publicly available datasets (meta-dataset), yielding two subtypes. (B) Consensus clustering was performed independently on a dataset of high-grade bladder tumors obtained from MSKCC (n = 49). (C) The median gene expression of all common genes between the datasets were compared, and the Pearson correlation was plotted (yellow, correlation; blue, anticorrelation). Numerical values represent the Pearson correlation. (D) Gene expression of epithelial and urothelial markers were visualized by heatmap, supervised by ConsensusClusterPlus calls in the meta-dataset. (E) Significantly differentially expressed genes between K1 and K2 from the meta-dataset and their respective fold changes, as determined by two-class SAM (2,393 genes; FDR, 0) were analyzed for predicted pathway enrichment by IPA. Selected significant pathways enriched in K1 are shown.

To validate that the gene expression changes that define the two subtypes are similar, we determined the correlation between the median gene expression (using all common genes between datasets) for each subtype (Fig. 1C; yellow, correlation; blue, anticorrelation). There appeared to be a high level of correlation between the meta-dataset K1 cluster and MSKCC K2 cluster, as well as between the meta-dataset K2 cluster and MSKCC K1 cluster. Thus, the intrinsic molecular subtypes defined by independent discovery in the two datasets are defined by highly concordant gene expression patterns and suggest that the subtypes are robust.

Intrinsic Molecular Subtypes of Bladder Cancer Differentially Express Markers of Urothelial Differentiation.

To understand the gene expression patterns that differentiate the intrinsic subtypes of high-grade bladder cancer, we performed two-class significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) comparing clusters K1 and K2 from the meta-dataset. A total of 2,393 genes were found to be differentially expressed [false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff, 0] (SI Appendix, Table S2). The intrinsic molecular subtypes were characterized by gene expression patterns representative of urothelial differentiation. Cluster K1 of the meta-dataset expressed high levels of the high molecular weight keratins (HMWKs) keratin 14 (KRT14), keratin 5 (KRT5), and keratin 6B (KRT6B), as well as of CD44 molecule (CD44), which are expressed in urothelial basal cells (22, 23). In contrast, cluster K2 expressed high levels of uroplakins [uroplakin 1B (UPK1B), uroplakin 2 (UPK2), and uroplakin 3A (UPK3A)], as well as the low molecular weight keratin (LMWK) keratin 20 (KRT20) (Fig. 1D), characteristic of urothelial umbrella cells (23). Moreover, the gene expression of KRT5 was inversely correlated with that of both UPK2 and KRT20 across all tumors (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 E and F). Similar findings were seen in the MSKCC dataset (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C, F, and G).

We performed ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) to examine whether processes other than urothelial differentiation were associated with the intrinsic subtypes. IPA revealed that K1 cluster tumors were enriched in gene pathways involving cancer, cell survival, and cell movement (Fig. 1E). In aggregate, these findings demonstrate that the two molecular subtypes of high-grade MIBC represent different stages of urothelial differentiation, leading us to name cluster 1 “basal-like” and cluster 2 “luminal.”

BASE47 Accurately Predicts Basal-Like and Luminal Subtypes.

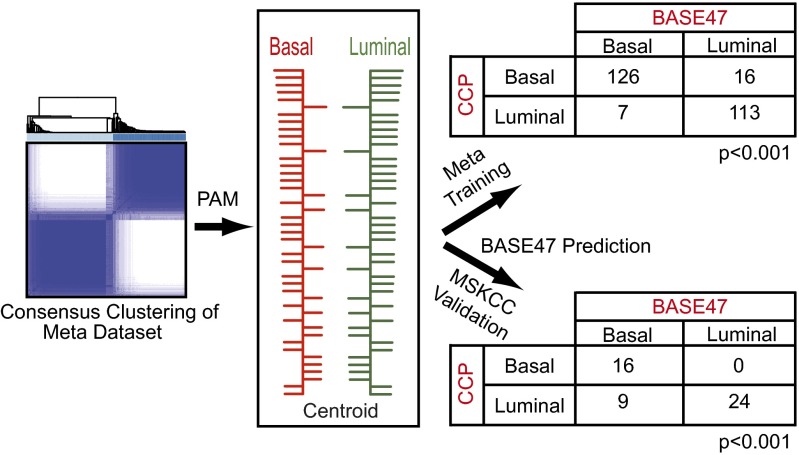

We next sought to define a minimal set of genes that could accurately classify bladder tumors into the luminal and basal-like bladder intrinsic subtypes. To this end, we applied prediction analysis of microarrays (PAM) to our meta-dataset and derived a 47-gene signature, BASE47 (SI Appendix, Table S3), that could accurately classify basal-like and luminal tumors relative to consensus clustering (training error rate, 0.11 and 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 2). A pairwise comparison of the subtype classification by consensus clustering relative to classification by BASE47 showed a strong correlation in both the meta-dataset and the MSKCC datasets (both P < 0.001, χ2 test). Cluster analysis using the MSKCC tumors illustrates the gene expression patterns that compose the BASE47 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A).

Fig. 2.

Generation of the BASE47 subtype predictor. PAM was performed using the basal-like and luminal subtype calls generated by ConsensusClusterPlus. A predictor consisting of 47 genes was generated that accurately predicted the subtypes from the meta-dataset training set (P < 0.001), as well as a MSKCC validation dataset (45 of 47 genes present; P < 0.001).

Intrinsic Bladder Subtypes Have Differential Survival.

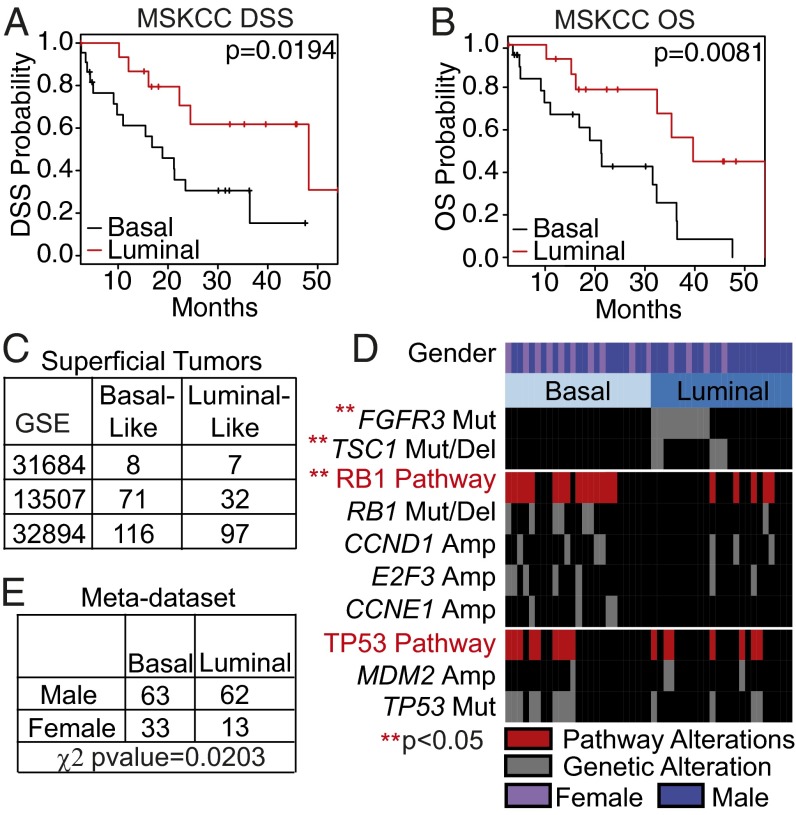

We next asked whether the intrinsic bladder subtypes had prognostic significance. Basal-like tumors (as identified by BASE47) had significantly decreased disease-specific and overall survival (P = 0.0194 and P = 0.0081 respectively) (Fig. 3 A and B). Moreover, of the clinicopathological features available to us in the MSKCC dataset, only BASE47 subtype was found to be significant for disease-specific survival by univariate analysis (SI Appendix, Table S4 and Fig. S2B).

Fig. 3.

Luminal and basal-like bladder cancer have differential survival and are associated with distinct genomic alterations. (A and B) Kaplan–Meier plots for muscle-invasive tumors from the MSKCC dataset (≥pT2) were generated for disease-specific survival (A) and overall survival (B). Basal-like tumors (n = 22) had a significantly decreased disease-free and overall survival compared with luminal tumors (n = 16) (P = 0.0194 and 0.0081, respectively). (C) Superficial tumors not included in the generation of BASE47 were subjected to BASE47 subtype prediction. (D) Sequencing and copy number analysis was performed on common mutations in bladder cancer. FGFR3 and TSC1 alterations were significantly enriched in luminal bladder cancer, whereas alterations of the RB1 pathway were enriched in basal-like bladder cancer. TP53 alterations were distributed evenly in both subtypes. (E) Basal-like and luminal tumors from the meta-dataset were annotated for sex (two of four datasets). The prevalence of basal-like bladder cancer was significantly greater in female patients (P value = 0.0203, χ2 test).

Furthermore, to assess the prognostic value of the BASE47 relative to published prognostic signatures derived from high-grade, muscle-invasive tumors, we generated “good” and “poor” prognosis calls on the MSKCC tumors using the published gene lists (11, 13) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D). Neither gene signature demonstrated prognostic value (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E and F). Thus, the BASE47 intrinsic bladder subtypes not only reflect bladder cancer biology, but also have prognostic value. Interestingly, whereas the BASE47 predictor was developed on muscle-invasive tumors, we also noted that when applied to a meta-dataset of superficial tumors, it classified a significant proportion them as basal-like (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the intrinsic subtypes may exist in NMIBC.

Intrinsic Subtypes Are Associated with Distinct Genomic Alterations.

The MSKCC tumor set has been previously characterized for bladder cancer-relevant genetic alterations (8). We examined the relative enrichment of these molecular events in the bladder subtypes (Fig. 3D). Notably, FGFR3 (P < 0.001) and tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) (P = 0.02) mutations were significantly enriched in the luminal subtype, whereas RB1 pathway alterations [i.e., RB1 mutations/deletions, Cyclin D1 (CCND1) amplification, E2F transcription factor 2 (E2F3) amplification, or Cyclin E1 (CCNE1) amplification] were significantly enriched in basal-like bladder cancer (P = 0.009).

Multiple studies have shown poorer bladder cancer-specific outcomes in females compared with males (24). We found a trend toward enrichment of basal-like tumors in female patients in the MSKCC dataset (Fig. 3D; P = 0.1137), and a significantly higher incidence of basal-like bladder cancer in female patients in the meta-dataset with annotated sex (Fig. 3E). This enrichment of basal-like bladder cancer may explain in part the poorer bladder cancer-specific outcomes in women.

Basal-Like Bladder Cancer Is Enriched for the Signatures of Basal-Like Breast Cancer and Tumor-Initiating Cells.

A number of genes fundamental for breast development and breast cancer were found to be coregulated with genes that regulate urothelial development (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Moreover, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) performed on the meta-dataset to identify gene sets enriched in the intrinsic subtypes found multiple breast cancer-related gene signatures enriched in the basal-like bladder subtype, as well as signatures related to mammary stem cells (SI Appendix, Table S5). In keeping with these findings, we found that a previously published bladder tumor initiating cell (TIC) signature (22) was enriched in the basal-like subtype by both hierarchical clustering (P = 2 × 10−16, χ2 test) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) and GSEA (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B), suggesting that basal-like bladder cancer has a more “stem-like” phenotype, similar to that described previously in basal-like breast cancer (25).

Intrinsic Bladder Subtypes Reflect the Attributes of Breast Cancer Subtypes.

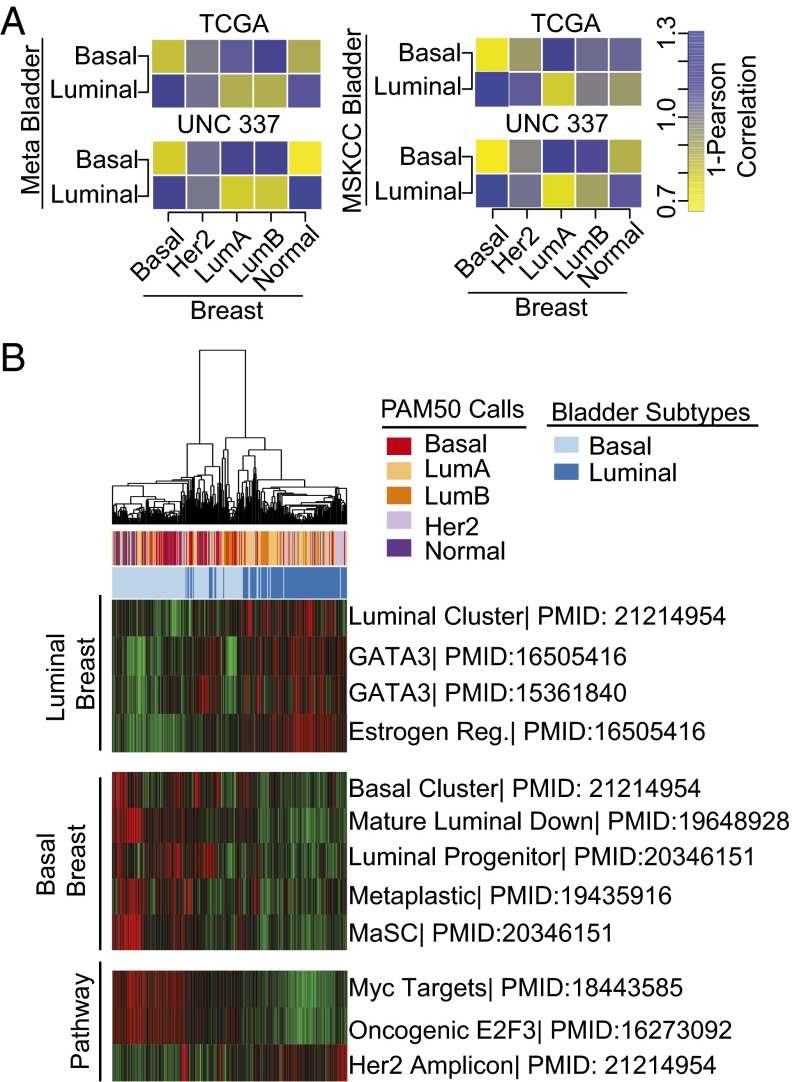

We next asked whether the basal-like and luminal bladder cancer subtypes correlated with any of the previously defined molecular subtypes of breast cancer (26). To this end, we generated breast cancer molecular subtype classifications (basal, Her2-enriched, luminal A, luminal B, and normal-like) on two independent sets of breast tumors [The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (27) and UNC337 (28)] using the PAM50 nearest-centroid classifier (29). To examine whether the gene expression patterns of luminal and basal-like bladder cancers were reflected in the intrinsic breast cancer subtypes, we correlated the centroid gene expression (using the breast intrinsic gene list) between the bladder and breast cancer subtypes (Fig. 4A; yellow, correlation; blue, anticorrelation). Basal-like bladder cancers demonstrated positive correlations with basal-like breast as well as normal-like breast cancer subtypes, whereas luminal bladder cancers had positive correlations with both luminal A and luminal B breast cancer subtypes.

Fig. 4.

Basal-like and luminal bladder cancers are correlated with the intrinsic molecular subtypes of breast cancer. (A) Median gene expression of genes present in the breast cancer-specific intrinsic gene list were determined for each bladder and breast subtype, and 1-Pearson correlation was calculated comparing bladder subtypes (bladder tumors) with breast subtypes (breast tumors) in both the TCGA and UNC337 breast datasets. (B) The meta-dataset tumors were run against previously published breast cancer-related gene sets. The resulting pathway scores were clustered by hierarchical clustering, and heatmaps were generated for visualization.

A similar comparison using published gene expression data from TCGA showed that whereas there were other cross-cancer similarities, the molecular association between breast and bladder cancers was relatively strong (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C) (27, 30–34). Finally, strikingly, applying PAM50 to our meta-dataset of bladder tumors revealed positive correlations between basal-like bladder tumors and the basal centroid and luminal bladder tumors and the luminal A centroid subtype (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 D and E).

To better visualize this association, we hierarchically clustered the bladder tumors using a comprehensive list of 1,906 genes (1,426 of which were present in the meta-dataset) that were previously shown to define the intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer (29). The breast-specific gene list clustered the bladder tumors along the lines of basal-like and luminal bladder subtypes (P = 2.2e-16, χ2 test) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4F). Furthermore, gene signatures representative of basal-like and luminal breast cancers as well as well-defined breast cancer-related oncogenic pathway signatures faithfully clustered basal-like and luminal bladder tumors in both datasets (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Basal-like bladder tumors displayed enhanced MYC and E2F3 pathway signatures, whereas luminal tumors appeared enriched in the set of genes characteristic of the HER2 amplicon. Taken together, these data strongly demonstrate that the gene expression patterns that distinguish basal-like and luminal bladder cancers reflect the RNA expression patterns that define the intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer.

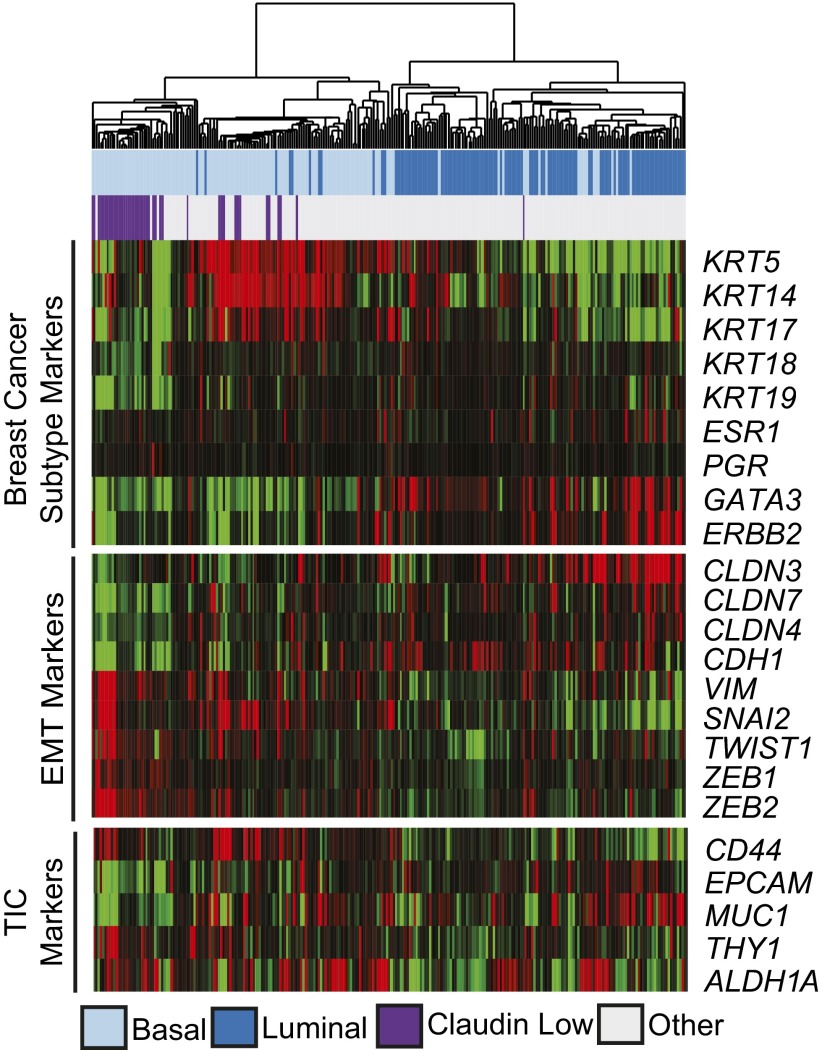

A Subset of Basal-Like Bladder Tumors Are Claudin-Low.

The recently described claudin-low molecular subtype of breast cancer is characterized by low expression of the claudin tight junction proteins (claudins 3, 4, and 7) and up-regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers as well as stem cell-like features (28). Tumors from the meta-dataset were classified based on an 807 gene signature, which accurately defines claudin-low breast cancer (28). Overall, 16% of the meta-dataset tumors (Fig. 5) and 26% of the MSKCC tumors (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B) were identified as claudin-low. When clustered based on genes that define key molecular pathways in claudin-low breast tumors (breast cancer subtype markers, EMT markers, and TIC markers) (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B) the claudin-low bladder tumors displayed expression patterns indicative of claudin-low breast tumors. In addition, whereas all of the claudin-low tumors were of the basal subtype, they did not appear to have different disease-specific or overall survival from basal-like bladder tumors (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D), in keeping with the claudin-low subtype in breast cancer (28). Thus, a subset of basal-like bladder tumors have claudin-low features.

Fig. 5.

A subset of basal-like bladder tumors are claudin-low. The meta-dataset was clustered hierarchically using representative genes known to define claudin-low breast tumors. Claudin-low subtype designation was assigned using a previously defined 807-gene signature.

Discussion

Using independent discovery in distinct datasets, we have defined two molecular subtypes of high-grade UC with molecular features reflecting different stages of urothelial differentiation. Luminal bladder cancers express markers of terminal urothelial differentiation, such as those seen in umbrella cells (UPK1B, UPK2, UPK3A, and KRT20), whereas basal-like tumors express high levels of genes that typically mark urothelial basal cells (KRT14, KRT5, and KRT6B). The basal cell compartment is a common feature of most organs with stratified or pseudostratified epithelium. It is characterized by its proximity to the basement membrane and is thought to harbor multipotent tissue stem cells important for normal tissue homeostasis and orderly regeneration after injury. Because basal cells are a long-lived population, they are potentially more likely to incur multiple genomic alterations, including changes in their chromatin landscape. In this regard, it is interesting to note that there appears to be a relatively high prevalence of mutations in histone- and chromatin-modifying genes in UC (3).

The luminal and basal-like subtypes of bladder cancer reflect many of the hallmarks of the intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. For example, a number of basal-like and luminal breast cancer-specific gene signatures were enriched in the corresponding bladder subtype, including bonafide luminal breast cancer pathways, such as GATA3 and estrogen receptor signaling in the luminal bladder subtype. Moreover, the gene expression patterns that define luminal and basal-like bladder cancers closely corresponded with the gene expression patterns that define luminal (A and B) and basal-like breast cancers. These similarities may reflect the presence of urothelial basal cells and their corollary, the basal/myoepithelial cells of the breast. In both tissues, these basal cells represent a multipotent “stem/progenitor cell” population (35, 36) and their similar functional roles may explain their similar molecular profiles.

We identified some differences between the breast and bladder cancer intrinsic subtypes as well. For example, whereas we identified a claudin-low subtype of bladder cancer, in contrast to breast cancer in which claudin-low tumors arise from multiple intrinsic subtypes, all of the claudin-low bladder tumors are a subpopulation of the basal-like subtype. Furthermore, despite a subset of luminal bladder tumors with elevated expression of the HER2 amplicon, we did not find any significant correlation with the Her2-enriched breast subtype using our correlation matrix (Fig. 4A).

Our study has created a gene signature, BASE47, which accurately discriminates intrinsic bladder subtypes. Interestingly, even in superficial bladder tumors, there appears to be a significant number of basal-like tumors. Although the characteristics of our meta-dataset did not allow us to determine whether the subtypes were prognostic or predicted the progression to muscle-invasive disease in superficial bladder tumors, these are important questions with significant clinical implications, such as early cystectomy for patients with high-grade T1 disease. The ability to accurately classify basal-like and luminal bladder subtypes with only 47 genes should allow the adoption of BASE47 to formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissues, allowing its widespread use.

Female patients with UC have inferior outcomes compared with males with UC, even when controlling for other known prognostic variables, such as stage and grade (24). Interestingly, we found that females have an increased incidence of basal-like bladder cancer, which is associated with worse outcomes. To the extent to which this increased prevalence of basal-like bladder tumors in women contributes to their poorer outcomes remains unclear. Moreover, whether this association suggests that the pathogenesis of bladder cancer in females (i.e., chronic inflammation) is different is of interest.

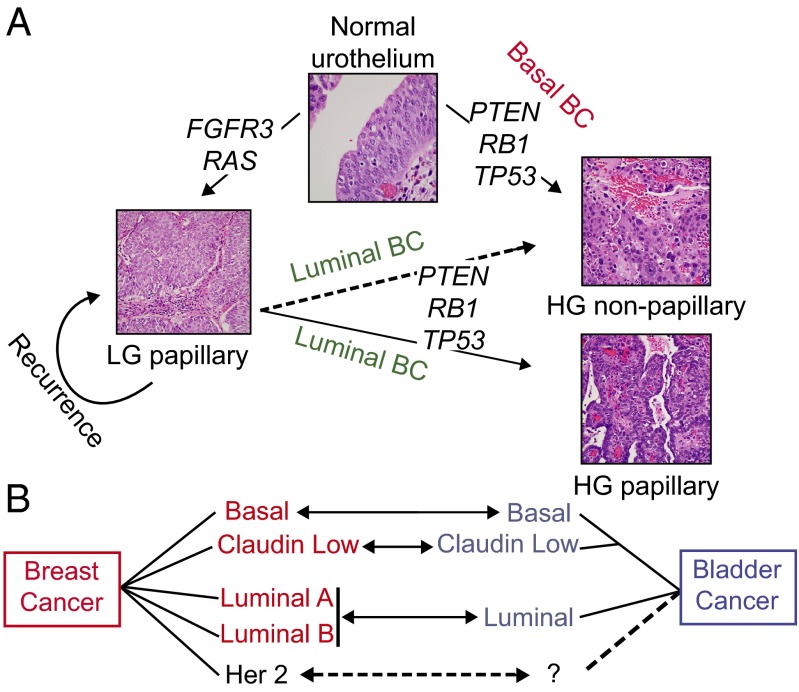

In summary, the basal-like and luminal intrinsic subtypes of bladder cancer reflect many aspects of urothelial physiological development, as well as breast cancer biology (Fig. 6 A and B). These findings underscore the idea of common themes underlying the development and maintenance of solid tumors that extend beyond overlapping mutational spectra. An appreciation of subtype heterogeneity has substantially furthered our understanding of breast cancer biology. Our results suggest that the intrinsic subtypes of high-grade bladder cancer strikingly reflect many aspects of breast cancer. It will be particularly interesting to see whether the bladder subtypes, like the breast subtypes, are useful in stratification for therapy.

Fig. 6.

Proposed model of urothelial tumorigenesis and relationships with intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer. (A) Low-grade (LG) and high-grade (HG) UCs are associated with specific genetic alterations. Low-grade papillary tumors often incur FGFR3, RAS, and receptor tyrosine kinase alterations, whereas high-grade tumors are characterized by loss of tumor-suppressor genes, such as PTEN, TP53, and RB1 pathway alterations. Whereas most low-grade tumors recur as low-grade, a small proportion progress to high-grade tumors in association with PTEN, TP53, and RB1 pathway alterations. We propose that low-grade tumors that progress are likely to be high-grade papillary tumors of the luminal molecular subtype, and that de novo high-grade tumors are likely to be of the basal-like expression subtype. Whether luminal, nonpapillary tumors arise from low-grade tumors is unclear. (B) Diagram showing the proposed relationship between intrinsic subtypes of breast and bladder cancers.

Materials and Methods

Training Dataset Analysis.

A meta-dataset was generated by combining the muscle-invasive (≥T2) UC samples from four publicly available datasets (GSE13507, GSE31684, GSE32894, and GSE5287) with clinical annotation provided by the Michor laboratory at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The data were normalized, median-centered by gene, and merged into a single dataset comprising 262 tumors. The mean absolute deviation (MAD) was computed across samples by gene. Genes with a MAD score of >0.10 were selected for clustering analysis (7,303 genes). Consensus hierarchical clustering was performed as described previously (37), with 90% resampling and 1,000 iterations. Two-class SAM (FDR, 0) was performed to generate subtype-specific gene lists (38). The significant genes and corresponding fold changes as determined by SAM were analyzed by IPA (Ingenuity Systems) for predicted pathway activation. GSEA was performed comparing basal and luminal tumors against MSigDB.c2.all.v4.0 (39, 40).

Validation Dataset.

Gene expression data were derived from 49 high-grade tumors from MSKCC using human HT-12 expression BeadChip arrays (Illumina) as described previously (8). The MSKCC dataset was normalized and median-centered, and the MAD was computed across samples by gene. Genes with a MAD score of >0.10 were selected for clustering analysis (3,357 genes). Consensus clustering was performed identically to the meta-dataset (37). The resulting subtype assignments for K2 were used to validate the training dataset. Centroids were generated for both the meta-dataset and MSKCC dataset using all common genes, and correlations were calculated by 1-Pearson correlation. Copy number alterations and hotspot mutation analyses were determined as described previously (8).

Subtype Predictor.

PAM was used to determine the minimal number of genes that could accurately predict subtype classification on the meta-dataset, using the consensus clustering calls as a reference (41). The resulting 47-gene predictor (Δ = 6.3) was used to classify the MSKCC samples (41). Tumors were then analyzed for enrichment of mutations or copy number alterations (8) by the χ2 or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Categorical survival analyses were performed using the log-rank test and visualized with Kaplan–Meier plots. BASE47 was then applied to superficial tumors, which were excluded from the meta-dataset. The superficial tumors were normalized and median-centered as described previously, and BASE47 calls were made using PAM.

Correlation with Breast Cancer.

TCGA (27) and UNC337 (GSE18229) breast mRNA datasets were log-transformed and median centered. Breast and bladder subtypes were correlated using Pearson correlation (visualized as 1-Pearson) by the median gene expression of the breast cancer intrinsic gene list (29). PAM50 calls were made on the individual datasets that composed the meta-dataset and the MSKCC dataset as described previously (29). Breast cancer signature enrichment was performed as described previously (42). Samples were hierarchically clustered and visualized on a heatmap. Claudin-low subtype calls were made as described previously (28).

Note Added in Proof.

During the course of our studies, we became aware of the work by Choi et al. (43) whose results independently demonstrate the existence of basal and luminal subtypes of high grade bladder cancers with molecular features that resemble their corresponding breast cancer subtypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the W.Y.K. and Perou laboratories, as well as Matthew Wilkerson, for useful discussions. We also thank Dr. Keith Chan for sharing his bladder TIC gene signature. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA142794 (to W.Y.K.), T32-CA009688 (to C.J.T.), and Integrative Vascular Biology Training Grant T32-HL069768 (to J.S.D.). W.Y.K. is a Damon Runyon Merck Clinical Investigator.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: J.S.D. and W.Y.K. have submitted a patent application for the BASE47 gene classifier.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1318376111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goebell PJ, Knowles MA. Bladder cancer or bladder cancers? Genetically distinct malignant conditions of the urothelium. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(4):409–428. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gui Y, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Nat Genet. 2011;43(9):875–878. doi: 10.1038/ng.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindgren D, et al. Integrated genomic and gene expression profiling identifies two major genomic circuits in urothelial carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindgren D, et al. Combined gene expression and genomic profiling define two intrinsic molecular subtypes of urothelial carcinoma and gene signatures for molecular grading and outcome. Cancer Res. 2010;70(9):3463–3472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-Knowles E, et al. PIK3CA mutations are an early genetic alteration associated with FGFR3 mutations in superficial papillary bladder tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7401–7404. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjödahl GG, et al. A systematic study of gene mutations in urothelial carcinoma; inactivating mutations in TSC2 and PIK3R1. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e18583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyer G, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of actionable genomic alterations in high-grade bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):3133–3140. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinney CPN, et al. Focus on bladder cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(2):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X-R. Urothelial tumorigenesis: A tale of divergent pathways. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(9):713–725. doi: 10.1038/nrc1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Lozano J, Saint F, Cordon-Cardo C. Defining molecular profiles of poor outcome in patients with invasive bladder cancer using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(5):778–789. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riester M, et al. Combination of a novel gene expression signature with a clinical nomogram improves the prediction of survival in high-risk bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(5):1323–1333. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaveri E, et al. Bladder cancer outcome and subtype classification by gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(11):4044–4055. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyrskjøt L, et al. Identifying distinct classes of bladder carcinoma using microarrays. Nat Genet. 2003;33(1):90–96. doi: 10.1038/ng1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SC, et al. A 20-gene model for molecular nodal staging of bladder cancer: Development and prospective assessment. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70296-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J-S, et al. Expression signature of E2F1 and its associated genes predict superficial to invasive progression of bladder tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2660–2667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modlich O, et al. Identifying superficial, muscle-invasive, and metastasizing transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: Use of cDNA array analysis of gene expression profiles. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3410–3421. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim W-J, et al. A four-gene signature predicts disease progression in muscle invasive bladder cancer. Mol Med. 2011;17(5-6):478–485. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjödahl G, et al. A molecular taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(12):3377–3386. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0077-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim W-J, et al. Predictive value of progression-related gene classifier in primary non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Als AB, et al. Emmprin and survivin predict response and survival following cisplatin-containing chemotherapy in patients with advanced bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15 Pt 1):4407–4414. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan KS, et al. Identification, molecular characterization, clinical prognosis, and therapeutic targeting of human bladder tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(33):14016–14021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906549106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castillo-Martin M, Domingo-Domenech J, Karni-Schmidt O, Matos T, Cordon-Cardo C. Molecular pathways of urothelial development and bladder tumorigenesis. Urol Oncol. 2011;28:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donsky H, Coyle S, Scosyrev E, Messing EM. Sex differences in incidence and mortality of bladder and kidney cancers: National estimates from 49 countries. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(1):e23–e31. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim E, et al. kConFab Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nat Med. 2009;15(8):907–913. doi: 10.1038/nm.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perou CM, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490(7418):61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prat A, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(5):R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker JS, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499(7456):43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kandoth C, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakha EA, Reis-Filho JS, Ellis IO. Basal-like breast cancer: A critical review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15):2568–2581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurzrock EA, Lieu DK, Degraffenried LA, Chan CW, Isseroff RR. Label-retaining cells of the bladder: Candidate urothelial stem cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294(6):F1415–F1421. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00533.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilkerson MD, Hayes DN. ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):1572–1573. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(9):5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mootha VK, et al. PGC-1alpha–responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately down-regulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Narasimhan B, Chu G. Diagnosis of multiple cancer types by shrunken centroids of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(10):6567–6572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082099299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan C, et al. Building prognostic models for breast cancer patients using clinical variables and hundreds of gene expression signatures. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi W, et al. Identification of distinct basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer with different sensitivities to frontline chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(2):152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.