Abstract

Previous studies have shown that the stem cell marker, c-Kit, is involved in glucose homeostasis. We recently reported that c-KitWv/+ male mice displayed onset of diabetes at 8 weeks of age; however, the mechanisms by which c-Kit regulates β-cell proliferation and function are unknown. The purpose of the present study is to examine if c-KitWv/+ mutation-induced β-cell dysfunction is associated with down-regulation of the phospho-Akt/Gsk3β pathway in c-KitWv/+ male mice. Histology and cell signaling were examined in C57BL/6J/KitWv/+ (c-KitWv/+) and wild-type (c-Kit+/+) mice using immunofluorescence and western blotting approaches. The Gsk3β inhibitor, 1-azakenpaullone (1-AKP), was administered to c-KitWv/+ and c-Kit+/+ mice for 2 weeks, whereby alterations in glucose metabolism were examined and morphometric analyses were performed. A significant reduction in phosphorylated Akt was observed in the islets of c-KitWv/+ mice (P<0.05) along with a decrease in phosphorylated Gsk3β (P<0.05), and cyclin D1 protein level (P<0.01) when compared to c-Kit+/+ mice. However, c-KitWv/+ mice that received 1-AKP treatment demonstrated normal fasting blood glucose with significantly improved glucose tolerance. 1-AKP treated c-KitWv/+ mice also showed increased β-catenin, cyclin D1 and Pdx-1 levels in islets demonstrating that inhibition of Gsk3β activity led to increased β-cell proliferation and insulin secretion. These data suggest that c-KitWv/+ male mice had alterations in the Akt/Gsk3β signaling pathway, which lead to β-cell dysfunction by decreasing Pdx-1 and cyclin D1 levels. Inhibition of Gsk3β could prevent the onset of diabetes by improving glucose tolerance and β-cell function.

Keywords: Akt/Gsk3β/cyclin D1 signaling pathway, c-KitWv/+ mice, Gsk3β kinase inhibitor, β-cell regeneration

Introduction

Loss of pancreatic β-cell mass and varying degrees of insulin secretory defects are observed in both type 1 and 2 diabetes. Restoring insulin-producing cells show great potential for attaining normal blood glucose levels and, thus, extensive research efforts are focused on developing methods to differentiate progenitor cells into β-cells1–3 and maintain their viability and function.4,5

Previous studies have emphasized that c-Kit (also known as CD117) together with its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), are important in a number of cell types to control a variety cellular process including haematopoiesis, gametogenesis, and melanogenesis,6,7 as well as pancreatic β-cell survival and maturation.8–15 Stimulation of c-Kit by SCF leads to dimerization of the c-Kit receptor and subsequent auto phosphorylation of intrinsic tyrosine kinases. Moreover, c-Kit receptor activation mediates multiple intracellular pathways, including the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway16 for modulation of gene transcription, proliferation, differentiation, metabolic homeostasis and cell survival.17–19 Stimulation of PI3K is required for the regulation of glucose and preproinsulin gene expression as well as the nuclear translocation of Pdx-120. Our previous in vitro studies of human fetal islets demonstrated that increased c-KIT activity leads to enhanced PDX-1 and insulin expression, and cell proliferation via the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway.21,22 Recently, our in vivo study showed that reduced c-Kit activity correlated with reduced β-cell function and proliferation, which is associated with significantly decreased Pdx-1 expression and glucose intolerance in c-KitWv/+ mice.13 Evidence from these studies suggests that in β-cells, SCF/c-Kit is a modulator of the PI3K/Akt pathway, upstream of Pdx-1.13,21 Nevertheless, the signaling pathway under c-Kit including PI3K/Akt and downstream targets involved in β-cell proliferation and function in vivo remains unclear.

Glycogen synthase kinase 3, a serine/threonine kinase, consists of two highly homologous α (Gsk3α) and β (Gsk3β) isoforms that share overlaping physiological functions in terms of regulating a diverse array of cellular processes. Gsk3β is one of the substrates that are directly regulated by the PI3K/Akt pathway. Activation of Akt, which phosphorylates Gsk3β at serine residue 9, leads to inactivation of Gsk3β.23–25 Unphosphorylated Gsk3β can directly phosphorylate downstream substrates, and modulate their activity.26 Apart from the function from which it derives its name (i.e., suppressing glycogen synthesis by phosphorylating glycogen synthase), studies have shown that Gsk3β is involved in mediating cell cycle, motility, and apoptosis,26 and that Gsk3β dysregulation is linked to several prevalent pathological diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and diabetes.26 Indeed, mice with β-cell-specific overexpression of Gsk3β displayed glucose intolerence due to reduced β-cell mass and proliferation.27 Furthermore, isolated adult human and rat islets incubated with Gsk3β inhibitors demonstrated a significant increase in islet cell proliferation.28 This evidence was further confirmed by mice with β-cell specific ablation of Gsk3β.29 Although the beneficial effect of Gsk3β inhibition has been demonstrated in islet biology, the physiological role of Gsk3β under disrupted c-Kit signaling in β-cell has yet to be investigated.

Our recent in vivo studies using c-KitWv/+ male mice have shown that disrupted c-Kit receptor function is associated with severe loss of β-cell mass and function, resulting in early-onset of diabetes.13 However, the intracellular mechanisms that relate the c-Kit receptor to physiological changes in β-cells have yet to be elucidated. The aim of the present study is to examine whether β-cell dysfunction in c-KitWv/+ male mice is associated with down-regulation of the phospho-Akt/Gsk3β pathway. Furthermore, 1-Azakenpaullone (1-AKP), a specific organic inhibitor that prevents Gsk3β phosphorylation of multiple downstream substrates by competitively binding at its ATP-binding site,30 was used to investigate whether inhibition of Gsk3β could improve β-cell proliferation and function, delaying the onset of diabetes in c-KitWv/+ mice. Here, we report that decreased β-cell proliferation and function in c-KitWv/+ mice was associated with dysregulated Akt and Gsk3β phosphorylation as well as cyclin D1 protein level. Treating c-KitWv/+ mice with 1-AKP delayed onset of diabetes, maintained β-cell mass and enhanced β-cell function. This study demonstrates a functional role for c-Kit in mediating glucose homeostasis and β-cell function via the Akt/Gsk3β axis in c-KitWv/+ mice.

Materials and Methods

Heterozygotic C57BL/6J/KitWv/+ male mice

c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male mice were obtained by breeding C57BL/6J/KitWv/+ parents heterozygous for the c-Kit point mutation (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA).13 Mice were genotyped by differences in fur pigmentation as described previously.13 Mice were maintained in an environment of constant temperature (20°C) and regular 12-hour day, 12-hour night cycles. Pancreata from both c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male littermates at 8 weeks old were dissected for experimentation. The animal use protocol was approved by the Animal Use Subcommittee at the University of Western Ontario in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care.

In vivo treatment with Gsk3β inhibitor and metabolic studies

To investigate whether inhibition of Gsk3β activity could prevent early onset of diabetes at 8 weeks of age in c-KitWv/+ mice,13 both c-Ki+/+ and c-KitWv/+ 6 week old mice were treated with either 1-azakenpaullone (1-AKP, VWR Canlab, Mississauga, ON, Canada) at 2mg/kg or saline injection intraperitoneally every other day for 2 weeks to establish four experimental groups:31,32 c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP. Body weight was measured weekly while fasting (4 hr) blood glucose levels, glucose (IPGTT) and insulin (IPITT) tolerance tests were performed at 8 weeks of age (after 2 weeks of 1-AKP treatment). For the IPGTT and IPITT, an intraperitoneal injection of glucose (D-(+)-Glucose (Dextrose, 2 mg/kg, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA)) or insulin (Humalin® 1U/kg, Eli Lilly, Toronto, Canada) was administrated to each mouse, respectively.13 Blood glucose levels were examined at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes following injection.

In vitro islet treatment with Gsk3β inhibitor

Islets were isolated from c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ mice at 8 weeks of age and cultured in RPMI 1640 media plus 10% FBS with or without 1-AKP (10μM) treatment for 24 hours. Islets were harvested for protein preparation. All culture experiments were conducted with at least three repeats per group.

In vivo and ex vivo GSIS study and insulin ELISA

To assess the effects of Gsk3β inhibition on insulin secretion, glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) both in vivo and on isolated islets was performed. For in vivo GSIS, at the end of either saline or GSK3β inhibitor treatment, mouse blood samples were collected from the tail vein following 4 hours of fasting (0 min), and at 5 and 35 minutes after glucose loading.13 Assessment of GSIS on isolated islets involved islet isolation using the hand-pick method13 and incubation of the islets in an oxygenated Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate HEPES plus 0.5% BSA buffer33 containing 2.2 mmol/L or 22 mmol/L glucose for 1 hour. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion was measured using an ultrasensitive (mouse) insulin ELISA (Alpco, Salem, New Hampshire, USA). A static glucose stimulation index was calculated by dividing insulin output from the high glucose (22 mmol/L) incubation by the insulin output during low glucose (2.2mmol/L) incubation.13

Double immunofluorescence and morphometric analysis

Pancreata collected from both c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ mice at 8 weeks of age with or without 1-AKP treatments were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) followed by a standard protocol of dehydration and paraffin embedding. Pancreatic tissue sections (4μm thick) were prepared and double-stained with primary antibodies of appropriate dilutions as listed (Table. S1). Secondary antibodies, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, anti-mouse or anti-guinea pig) and TexRed (anti-rabbit or anti-guinea pig), were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Double-immunolabeled images were recorded by a Leica DMIRE2 fluorescence microscope with Openlab image software (Improvision, Lexington, MA, USA).

Quantitative evaluation for islet number, islet size, α and β-cell mass was performed using computer-assisted image analysis, as described previously.13 In order to quantify cell proliferation (labeled by Ki67), cyclin D1 and Pdx-1 positive staining in β-cell nuclear, at least ten random islet images per pancreatic section were captured and counted. The average percent co-localization of cyclin D1+/insulin+, Ki67+/insulin+ and Pdx-1+/insulin+ cells was calculated. A minimum of five pancreata per age per experimental group with at least 1000 cells was analyzed. Data are presented as a percentage of the total number of insulin+ cells counted.13

Western Blot Analysis

Protein level of Akt, Gsk3β, β-catenin, cyclin D1 and Pdx-1 in both pancreata and islets from c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ mice at 8 weeks of age with or without 1-AKP treatment was analyzed. Equal amounts of lysate from each experimental group were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies as listed in Table S1, followed by incubation with a goat anti-mouse or rabbit IgG secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). As a control for sample loading, the blot was also probed with antibodies against total signaling or housekeeping proteins. Membranes were further incubated in chemiluminescence reagents (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA) and exposed to BioMax MR Film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) to visualize protein bands. Densitometric quantification of bands at sub-saturating levels was performed using the Syngenetool gel analysis software (Syngene, Cambridge, UK) and normalized to the loading controls. Data are expressed as relative level of phosphorylated proteins to total protein levels or protein levels to the loading controls.13

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from isolated islets of c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ mice with or without 1-AKP injection using the miRNeasy kit (QAIGEN, Germantown, MD)13. Sequences of PCR primers are listed (Table. S2). Real-time PCR analyses were performed using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix kit in Chromo4 Real time PCR (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Relative levels of gene expression were calculated and normalized to the internal standard gene, 18S rRNA, with at least five repeats per experimental group13,21–22.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired student’s t-test, or ANOVA followed by Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-Hoc tests. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when P<0.05.

Results

Reduction of phospho-Akt, phospho-Gsk3β and cyclin D1 in c-KitWv/+ mice

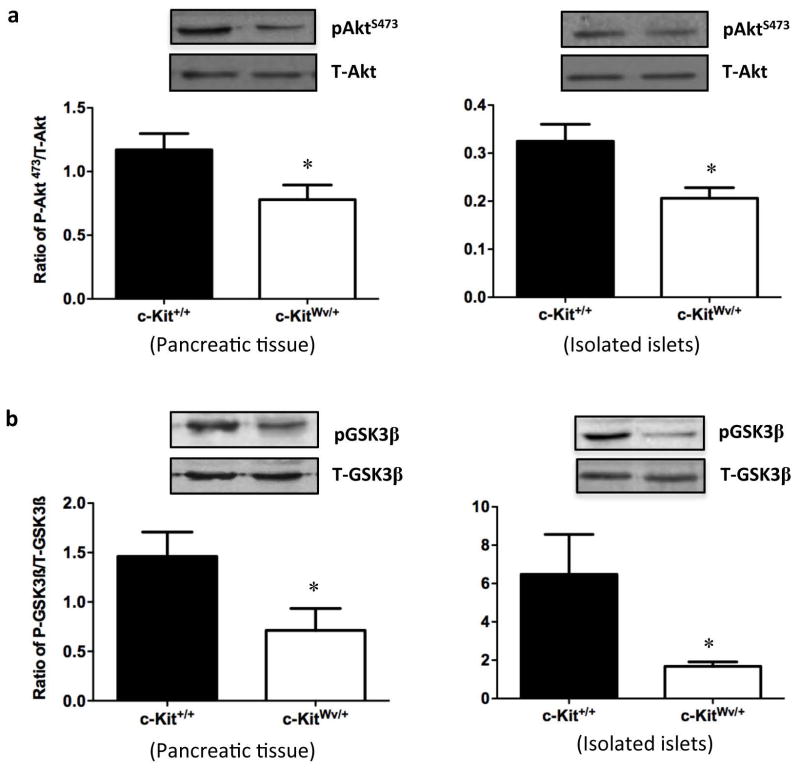

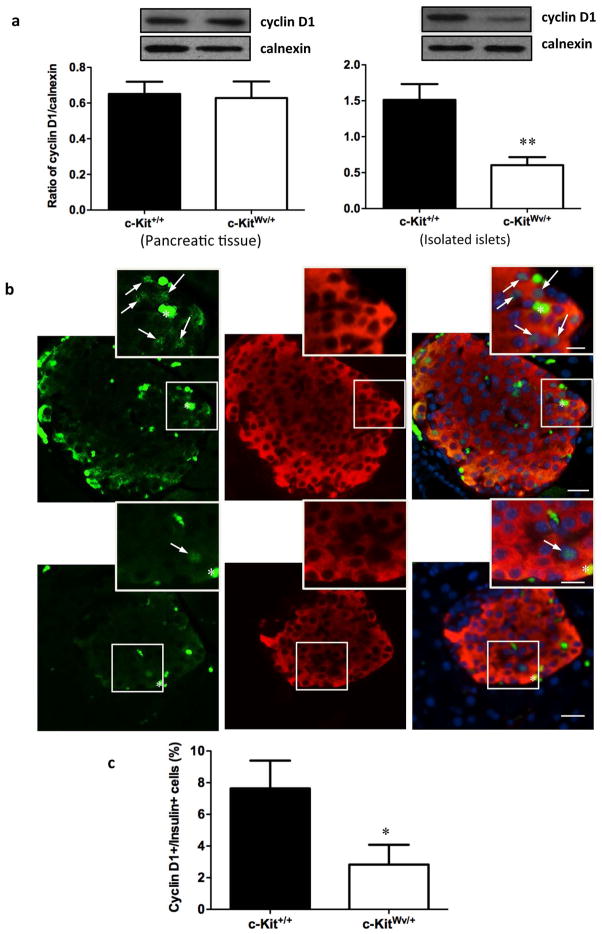

Our recent study has demonstrated that male mice with mutated c-Kit develop early onset of diabetes with a loss of β-cell mass and proliferation, suggesting that c-Kit plays a critical role in β-cell proliferation and function.13 Moreover, experiments in isolated human fetal islet-epithelial cells21,22 revealed that the PI3K/Akt pathway is significantly up-regulated upon exogenous SCF stimulation. Here, we showed that both whole pancreatic tissue and isolated islets from c-KitWv/+ male mice displayed a significant reduction in phosphorylated Akt at Ser473 (P<0.05, Figure 1a), but not at Thr308 (Figure S1a). In parallel, decreased protein level of phosphorylated Gsk3β at Ser9 was observed in c-KitWv/+ mice when compared to c-Kit+/+ mice (P<0.05, Figure 1b), but not at Tyr216 (Figure S1b). No alteration in cyclin D1 protein level was observed in total pancreatic tissue extract. However, a significant reduction in cyclin D1 protein expression was noted in isolated islets of c-KitWv/+ mice (P<0.01, Figure 2a) along with a 60% reduction in the proportion of cyclinD1+/insulin+ cells when compared to c-Kit+/+ mice (P<0.05, Figure 2bc).

Figure 1. Downregulation of phosphorylated Akt/Gsk3β signaling in the pancreas and isolated islet from c-KitWv/+ mice.

Western blot analysis of S473-phosphorylated (P) and total (T) Akt (a), phosphorylated (P) and total (T) Gsk3β (b) protein level in the pancreas and isolated islets of c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male mice at 8 week of age. Representative blots are shown. Data are normalized to total protein and expressed as means ± SEM (n=11 pancreas; n=3 isolated islets per experimental group) *P<0.05 vs. c-Kit+/+ male mice.

Figure 2. Decreased cyclin D1 protein level in isolated islet of c-KitWv/+ mice.

(a) Western blot analysis of cyclin D1 in the pancreas and isolated islets of c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male mice at 8 week of age. Representative blots are shown. Data are normalized to loading control calnexin and expressed as means ± SEM (n=4 pancreas; n=6 isolated islets per experimental group) **p<0.01 vs. c-Kit+/+ male mice. (b) Double immunofluorescence staining for cyclin D1 (green), insulin (red) of c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male mice pancreatic section at 8 week of age. Nuclear counter stained by DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 20μm (inset: 10μm). Arrows indicate cyclin D1/insulin double positive cells. (c) The percent of cyclin D1+ cells in β-cells of c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male mice at 8 week of age. Data are expressed as mean percent positive cells over insulin+ cells ± SEM (n=6) *P<0.05 vs. c-Kit+/+ male mice.

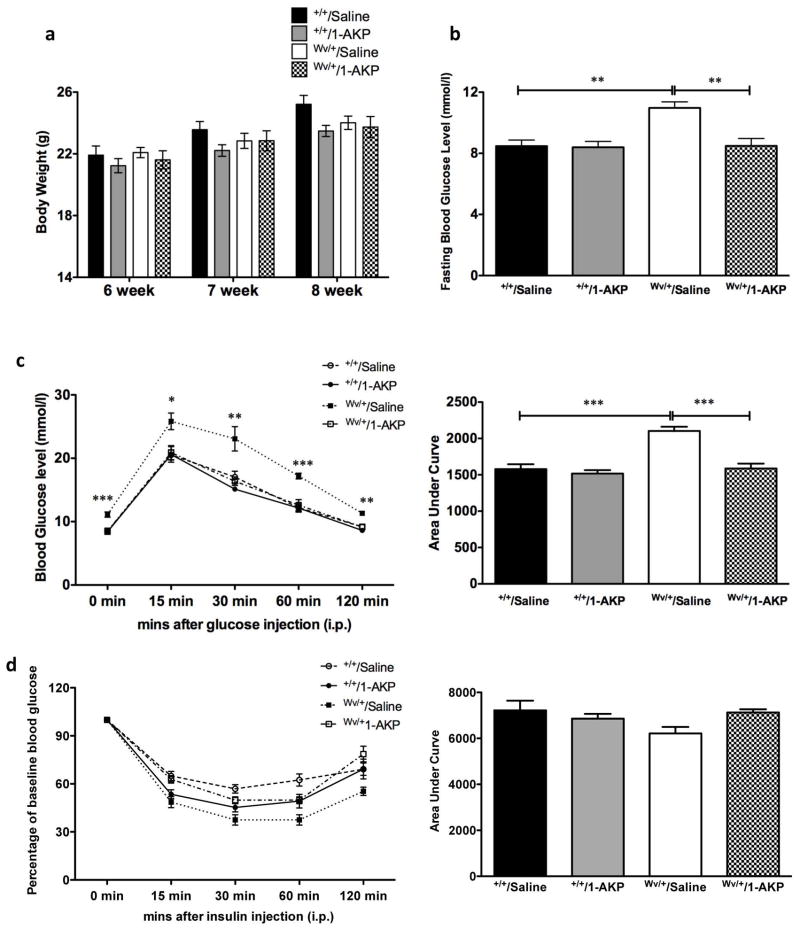

Inhibition of Gsk3β activity prevented early onset of diabetes in c-KitWv/+ mice

c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male mice that received saline or 1-AKP treatment revealed no significant change in body weight at 8 weeks of age (Figure 3a). However, fasting blood glucose levels in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice showed a significant improvement when compared to the c-KitWv/+/saline group (P<0.01, Figure 3b) and reached similar fasting blood glucose levels of the c-Kit+/+/saline and c-Kit+/+/1-AKP groups (Figure 3b). These improvements in glucose metabolism were further confirmed by glucose tolerance tests (Figure 3c). c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice showed similar glucose tolerance capacity to both c-Kit+/+/saline and c-Kit+/+/1-AKP groups, along with significant decreases in area under the curve (AUC) when the IPGTT was performed (P<0.001, Figure 3c). Insulin tolerance tests revealed no significant differences between the four experimental groups (Figure 3d).

Figure 3. Effect of Gsk3β inhibitor on glucose homeostasis of c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice.

Body weight (a) and fasting blood glucose level (b) of c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP groups. Intra-peritoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) (c) and insulin tolerance test (IPITT) (d) in c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mouse group. Glucose responsiveness of the corresponding experimental groups is shown as a measurement of area under the curve (AUC) of the IPGTT or IPITT graphs with units of [(mmol/L). min] shown on the Y-axis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n=6–8) *P<0.05, **P<0.01 ***P<0.001 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline group.

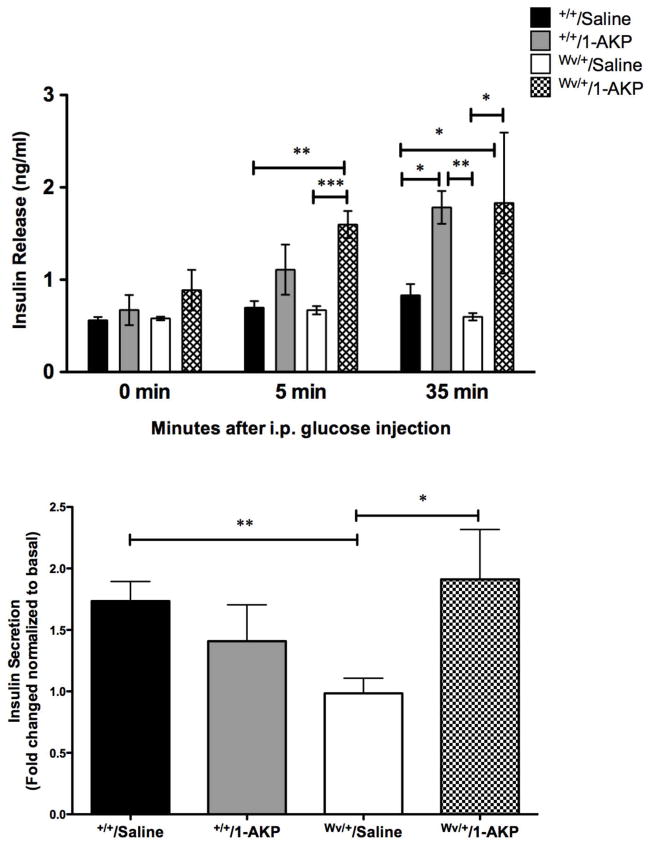

Furthermore, the effects of Gsk3β inhibition on insulin secretion were examined by the GSIS assay in vivo and on isolated islets. No significant differences were found in basal plasma insulin levels between the four experimental groups. However, 5 minutes after glucose stimulation, an increase in plasma insulin release was noted in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice when compared to the c-KitWv/+/saline (P<0.001) and c-Kit+/+/saline (P<0.01) groups (Figure 4a). There was a further increase in plasma insulin secretion at 35 minutes following stimulation in both 1-AKP treated groups (P<0.05–0.01, Figure 4a). To further confirm if these changes in insulin secretion upon glucose stimulation are observed in isolated islets, in vitro GSIS was performed using isolated islets from all experimental groups. Insulin secretion in response to 22 mM glucose was significantly increased in the islets of c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice, showing a 2-fold increase in insulin secretion compared to the c-KitWv/+/saline group (P<0.05, Figure 4b).

Figure 4. Effect of Gsk3β inhibitor on β-cell function of c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice.

(a) In vivo glucose-stimulated insulin secretion of c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP groups. c-KitWv/+/1-AKP groups demonstrated an increase in plasma insulin release after glucose loading (n=3–8). (b) Insulin secretion is improved in isolated islets from male c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice in response to 22mM glucose challenge; data are expressed as fold change normalized to basal (2.2mM glucose) secretion (n=4–5). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P< 0.001 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline group.

Inhibition of Gsk3β activity preserved β-cell mass in c-KitWv/+ male mice

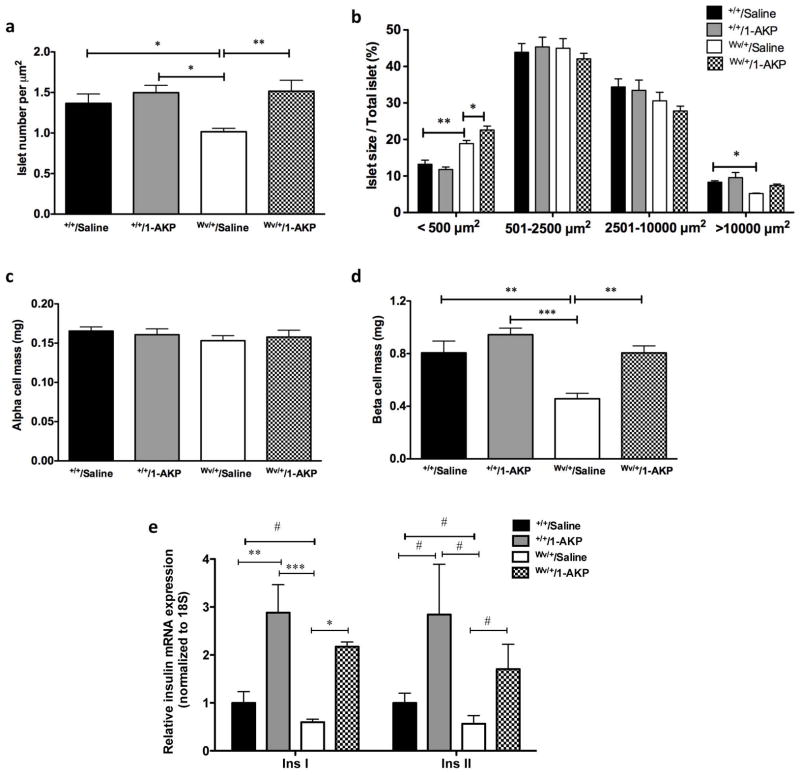

Our in vivo metabolic data suggests that inhibition of Gsk3β activity in c-KitWv/+ mice could prevent early onset of diabetes. There was no observed difference in pancreatic weight between all experimental groups (data not shown). Morphometric analyses were performed to examine the effects of the Gsk3β inhibitor on islet number and size as well as α- and β-cell mass in c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ male mice with or without 1-AKP treatments. A significant increase in the number of pancreatic islets was noted in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice (P<0.01, Figure 5a), with a significant increase in the number of small islets (<500 μm2) when compared to the c-KitWv/+/saline group (P<0.05, Figure 5b). Moreover, the number of large islets (>10000 μm2) was only slightly increased in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice when compared to the c-KitWv/+/saline group, while both c-Kit+/+/saline and c-Kit+/+/1-AKP groups had the most large islets (P<0.05, Figure 5b). Furthermore, β-cell mass in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice also increased by 24% when compared to the c-KitWv/+/saline group (P<0.01, Figure 5d), however it only reached 80–90% of the β-cell mass of the c-Kit+/+/saline and c-Kit+/+/1-AKP groups (Figure 5d). Increased β-cell mass was also correlated with increased expression of Insulin I and II genes in the islets of 1-AKP treated c-Kit+/+and c-KitWv/+ mice (Figure 5e). No alterations were detected in α-cell mass among any of the four experimental groups (Figure 5c).

Figure 5. Effect of Gsk3β inhibitor on pancreatic morphology of c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice.

Morphometric analysis of islet number (a), islet size (b), α-cell mass (c) and β-cell mass (d) in c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP groups. (n=6–8). (e) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Insulin I and II mRNA in isolated islets of c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n=5–8). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 was tested by one-way ANOVA analysis; #P<0.05 was analyzed by unpaired student t-test.

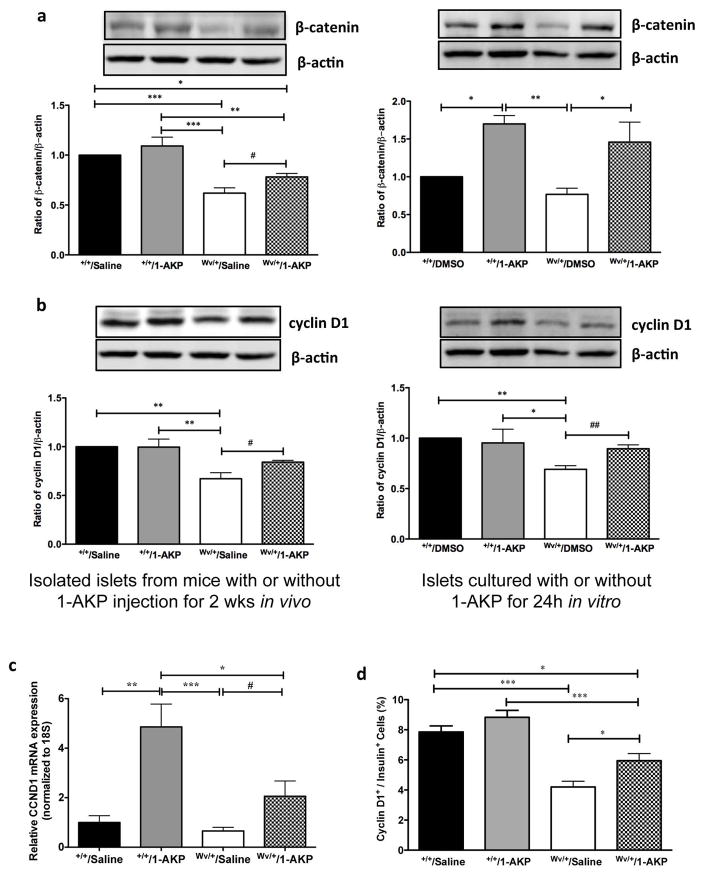

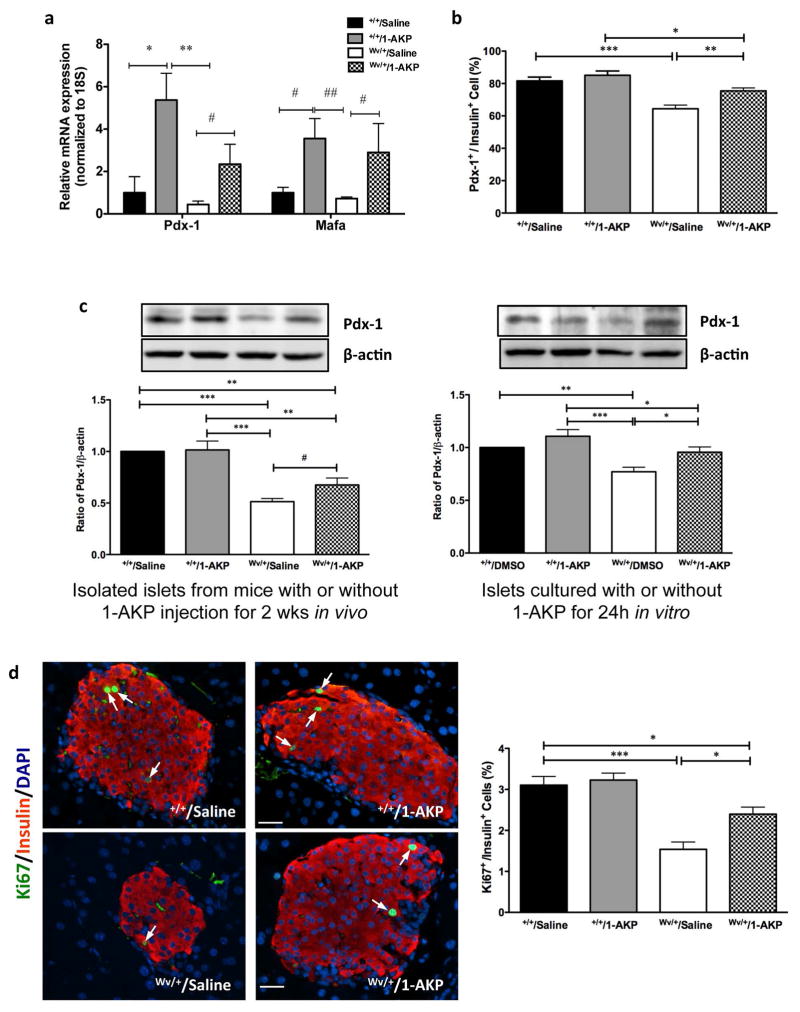

Inhibition of Gsk3β activity preserved β-catenin, cyclin D1, Pdx-1 and Mafa expression and increased the proliferative capacity of β-cells of c-KitWv/+ male mice

The effect of Gsk3β inhibition on downstream signaling mediators of β-catenin protein level in the islets of c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice was significantly higher when compared to the c-KitWv/+/saline group (P<0.05, Figure 6a). However, this protein level only reached 78% of both c-Kit+/+/saline and c-Kit+/+/1-AKP groups (P<0.05–0.01, Figure 6a). The c-KitWv/+/saline group showed a significantly lower level of islet β-catenin protein than that of c-Kit+/+/1-AKP and c-Kit+/+/saline groups (P<0.001, Figure 6a). In addition, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP mice showed slightly increased β-catenin protein level in islet protein extracts but did not reach statistical significance when compared to the c-Kit+/+/saline group (Figure 6a). The protein level of β-catenin was also significantly higher in isolated islets from c-KitWv/+ mice, when treated with 1-AKP for 24h, compared to non-treated c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+ islets (P<0.05, Figure 6a). These increases in islet β-catenin corresponded with significantly elevated islet cyclin D1 protein level in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice and c-KitWv/+ islets cultured with 1-AKP when compared to c-KitWv/+/saline mice and untreated isolated c-KitWv/+ islets, respectively (P<0.05–0.01, Figure 6b). These findings were further corroborated using q-RT-PCR and double immunofluorescence, which revealed significantly increased Ccnd1 mRNA (Figure 6c) and a higher number of cyclin D1+/insulin+ cells in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice (P<0.05 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline group, Figure 6d). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of Pdx-1 and Mafa showed significantly increased mRNA levels in the islets of both 1-AKP treated c-Kit+/+and c-KitWv/+ mice (Figure 7a). Double immunofluorescence demonstrated a significant increase in the number of Pdx-1+ cells in β-cells of c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice (P<0.01 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline group, Figure 7b) Increased Mafa staining intensity was also observed in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mouse β-cells (Figure S2). These results were further supported by western blot analysis and showed significantly higher Pdx-1 protein level in c-KitWv/+ islets from either 1-AKP injected mice or 1-AKP incubation when compared to c-KitWv/+/saline mice and c-KitWv/+ islets without 1-AKP treatment, respectively (P<0.05, Figure 7c). Furthermore, increased cyclin D1 expression (Figure 6bcd) was correlated with a significant increase in Ki67 immunoreactivity in β-cells of c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice (P<0.05 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline group, Figure 7d).

Figure 6. Inhibition of Gsk3β maintained β-catenin and cyclin D1 protein level in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mouse islets.

Western blot analysis of β-catenin (a) and cyclin D1 (b) in isolated islets from c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice (left column) and isolated islets from 8 weeks of c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+mice cultured with or without 1-AKP treatment for 24h (right column). Representative blots are shown. Data are normalized to β-actin and expressed as means ± SEM (n=4–5) *P <0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline groups by one-way ANOVA analysis. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 was analyzed by unpaired student t-test between c-KitWv/+islets with or without 1-AKP treatment. Quantitative analysis of cyclin D1 (CCND1) mRNA in isolated islets (c) and the number of nuclear cyclin D1+ cells in β-cells (d) of c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n=5–8). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline group by one-way ANOVA analysis. #P<0.05 was analyzed by unpaired student t-test.

Figure 7. Inhibition of Gsk3β resulted in increased Pdx-1 and Mafa expression, β-cell proliferation in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice.

Quantitative analysis of Pdx-1 and Mafa mRNA in isolated islets (a) and the number of Pdx-1+ (b) and Ki67+ (d, right) cells in β-cells of c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice. (c) Western blot analysis of Pdx-1 protein level in isolated islets from c-Kit+/+/saline, c-Kit+/+/1-AKP, c-KitWv/+/saline, and c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice (left column) and isolated islets from 8 week old c-Kit+/+ and c-KitWv/+mice cultured with or without 1-AKP treatment for 24h (right column). (d, left) Double immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 (green) with insulin (red), nuclear stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate Ki67/insulin double positive cells. Scale bar: 20 μm. Data are expressed mean ± SEM (n=5–8) *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. c-KitWv/+/saline group by one-way ANOVA analysis. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 was analyzed by unpaired student t-test.

Discussion

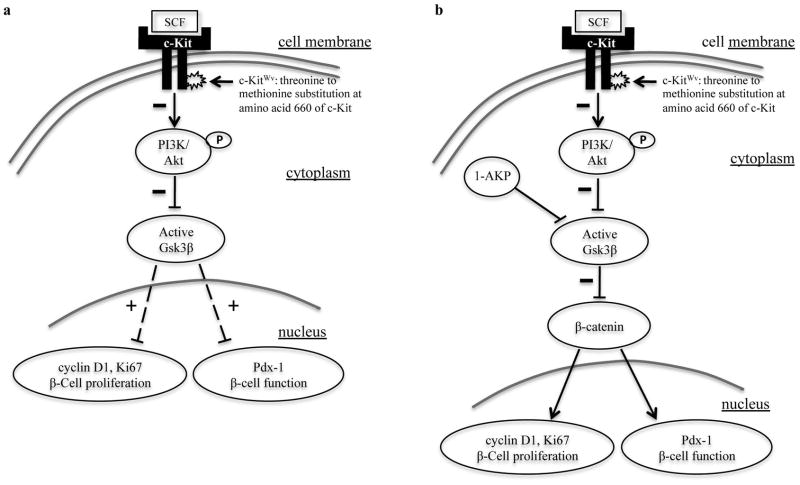

The present study demonstrates that diabetic c-KitWv/+ male mice displayed reduced levels of phospho-Akt at Ser473 and phospho-Gsk3β at Ser9 in both pancreatic and isolated islet protein extracts. These mice also possess decreased cyclin D1 expression in their β-cells. When treated with the Gsk3β inhibitor, 1-azakenpaullone (1-AKP), c-KitWv/+ mice demonstrated significant improvements in fasting glucose, glucose tolerance and insulin secretion along with increased β-cell mass and proliferation. These results indicate that the Akt/Gsk3β pathway downstream of the c-Kit receptor is predominantly involved in regulating β-cell proliferation and function in c-KitWv/+ male mice and that inhibition of Gsk3β activation can significantly improve glucose tolerance and β-cell function (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Schematic of proposed model involving c-Kit/Akt/Gsk3β signaling pathways in β-cell survival and function in c-KitWv/+ mice.

(a) Mutating the c-Kit receptor at the Wv locus lead to a down-regulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway via reduced phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473, which resulted in enhanced active Gsk3β and increased inhibition of Pdx-1 and cyclin D1 expression. (b) Direct inhibition of active Gsk3β with 1-AKP preserved β-catenin protein level, along with maintained cyclin D1 and Pdx-1 expression that allowed improvement of β-cell proliferation and function and prevented the onset of diabetes in c-Kit Wv/+ mice. “+”: enhanced; “−”: reduced; “↓”: stimulation; “⊥” inhibition.

The PI3K pathway is one of the major downstream pathways of c-Kit that triggers a variety of pro-survival signaling events, such as cell survival, cell growth, and cell cycle entry via Akt phosphorylation.21,34 Akt, a serine/threonine protein kinase, exerts its affects after being phosphorylated by PI3K at two regulatory residues; Thr308 in the activation segment, and Ser473 in the hydrophobic motif of the kinase domain.35 In the present study, we showed decreased protein levels of phospho-Akt at Ser473, but not at Thr308 in c-KitWv/+ mice when compared to controls. c-KitWv/+ mice are heterozygous for the c-Kit Wv mutation caused by substitution of a threonine to methionine at amino acid 660 in the kinase domains of the c-Kit receptor,36 and this loss-of-function mutation leads to down-regulation, but not abolition of c-Kit receptor activity. Previous research has demonstrated that Akt monophosphorylation on Thr308 showed only 10% kinase activity compared to 100% when Akt was doubly phosphorylated on Ser473 and Thr308,35 suggesting that Ser473 phosphorylation is required for maximal kinase activity of Akt.35 Therefore, our results demonstrate that c-KitWv/+ male mice showed significant down-regulation of the primary Akt phosphorylation site required conferring maximal activity, Ser473.

It is well documented that Gsk3β is the target of many important signaling molecules.37 In particular, Akt blocks the catalytic activity of the kinase, and activates downstream signals repressed by active Gsk3β.34 In the present study, we observed reduced Gsk3β phosphorylation and cyclin D1 protein level in islets of c-KitWv/+ male mice, which is consistent with the role of cyclin D1 as essential for postnatal β-cell growth.38 Active Gsk3β promotes destabilization of cyclin D1 and thus cell cycle arrest, which is associated with Akt inactivation.39 Taken together, our results suggest that Akt/Gsk3β axis dysregulation from the c-Kit Wv mutation contributed to loss of β-cell mass and function, which may have been responsible for the early onset of diabetes observed in c-KitWv/+ male mice reported previously.13

It has been previously shown that Gsk3β is involved in differentiation and proliferation of numerous tissue types including β-cells.28,29 Tanabe et al. showed that genetic ablation of Gsk3β in Irs−/− mice preserved β-cell function and prevented the onset of diabetes.40 Moreover, mice with β-cell-specific ablation of Gsk3β were resistant to high-fat diet induced diabetes.29 These studies suggest that endogenous Gsk3β activity is involved in a highly specialized feedback inhibition mechanism with the insulin receptor, which primarily signals via the PI3K/Akt pathway. In the present study, c-KitWv/+ mice received treatment of a Gsk3β inhibitor for 2 weeks and showed significant improvements in glucose tolerance and β-cell function when compared to saline-treated c-KitWv/+ controls, which showed diabetic symptoms. In addition, no significant differences in insulin tolerance were observed between the experimental groups suggesting that this improvement in glucose tolerance and β-cell function was not due to enhanced peripheral insulin sensitivity, but primarily to improved β-cell proliferation and function.

Our morphological analyses revealed that improved glucose tolerance and insulin secretion was associated with preservation of β-cell mass and an increase in islet number in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice. The most notable change was a significant increase in the percentage of small islets (<500 μm2), with a relative increase in the number of large islets (>10000 μm2), suggesting that inhibition of Gsk3β activity is associated with an increase in β-cell neogenesis and proliferation. β-catenin and cyclin D1 are two potential targets of Gsk3β, and have been implicated in β-cell growth.38,41 Preserved β-cell mass in the c-KitWv/+/1-AKP group was accompanied by increased β-cell proliferation (Ki67), and maintained β-catenin and cyclin D1 protein levels, which closely matched those of the c-Kit+/+ groups. This is in agreement with the role of β-catenin in up-regulating cyclin D1 expression to promote β-cell expansion.41,42 These results suggest that Akt/Gsk3β axis-mediated β-catenin activation in islets may regulate β-cell growth and function in c-KitWv/+ mice.43

The critically important pancreatic transcription factor, Pdx-1 has been shown to regulate β-cell survival, function and pancreatic development.44,45 Previous studies have also demonstrated that reduction of Pdx-1 impairs islet insulin secretion, 46,47 while, a partial reduction in Pdx-1 has a major effect on β-cell survival with reductions in BclXL and Bcl2 expression.45 Using c-KitWv/+ mice, we observed a significant reduction in Pdx-1 expression (~50% of WT controls) along with impaired β-cell function13 and an upregulation in the Fas associated cell death pathway (unpublished data). In the current study, Pdx-1 expression was maintained upon Gsk3β inhibition, suggesting that preservation of Pdx-1 expression is associated with increased insulin secretion in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mice. Previous studies in isolated mouse islets have shown that Pdx-1 is negatively regulated in a Gsk3β-dependent manner.48 In addition, inhibition of Gsk3β by activated Akt could ameliorate Pdx-1 phosphorylation leading to a consequential delay of its degradation, which suggests that Pdx-1 stability in β-cells may be mediated by the Akt/Gsk3β axis.49 Further in vivo studies have demonstrated that Gsk3β ablation in mouse β-cells lead to increased Pdx-1 protein level29,40 In addition, a significant up-regulation of Mafa mRNA expression in c-KitWv/+/1-AKP mouse islets was observed, which may have contributed to the observed improvements in β-cell insulin secretion. Overexpression of Mafa in neonatal rat β-cells led to enhanced glucose-responsive insulin secretion and β-cell maturation.50 Taken together, the findings of the present study showed that Akt/Gsk3β signaling, downstream of c-Kit, is not only required for β-cell proliferation, but also for mediating Pdx-1 and Mafa expression, which is essential for β-cell function and differentiation.

The present study demonstrates that the Gsk3β inhibitor, 1-AKP, predominantly improved β-cell proliferation and function, and had no significant effects in peripheral tissues, like muscle or liver insulin sensitivity. However, previous studies have shown that treatment of Gsk3β inhibitors improved glucose homeostasis by ameliorating muscle & liver insulin resistance in non-insulin dependent obese animal models.51–53 The c-Kit Wv point mutation primarily causes defect in melanocytic, hematopoietic, and endocrine cell lineages, with no apparent muscle and liver dysfunction.13, 36, 54 This is in contrast to non-insulin dependent diabetic animal models, such as ZDF rat and ob mice that have primary defects in muscle and liver insulin stimulated peripheral glucose transport activity.51–53 Thus, we speculate that the effects of Gsk3β inhibition depend upon the injury of the animal. Indeed, wild type mice in our analysis showed less responsiveness in lowering blood glucose when treated with Gsk3β inhibitors.

In summary, the present study elucidates a novel link between the c-Kit receptor and Akt/Gsk3β/cyclin D1 signaling pathways and their effects on β-cell proliferation and function in vivo (Figure 8). Our results suggest that dysregulated Akt/Gsk3β/cyclin D1 downstream from the c-Kit Wv mutation is the possible signaling mechanism that contributes to the loss of β-cell mass and function in c-KitWv/+ male mice reported in our previous publication.13 Furthermore, chronic inhibition of Gsk3β in c-KitWv/+ male mice resulted in increased β-catenin, cyclin D1, and Pdx-1 protein expression, suggesting that regulation of downstream signaling increased β-cell proliferative capacity, mass, as well as later improved glucose tolerance, and helped prevent early onset of diabetes. Taken together, the findings of present study emphasizes that understanding the complex intracellular pathways that affect β-cell proliferation and function in vivo, which the c-Kit receptor regulates, will enable the development of more successful treatment protocols for diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR MOP89800). Dr. Wang is supported by a New Investigator Award from CIHR. We are grateful to Ms. M. Liu for the technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Hao E, Tyrberg B, Itkin-Ansari P, et al. Beta-cell differentiation from nonendocrine epithelial cells of the adult human pancreas. Nat Med. 2006;12:310–316. doi: 10.1038/nm1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier JJ, Bhushan A, Butler PC. The potential for stem cell therapy in diabetes. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(Part 2):65R–73R. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000206857.38581.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang J, Au M, Lu K, et al. Generation of insulin-producing islet-like clusters from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1940–1953. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonner-Weir S, Sharma A. Pancreatic stem cells. J Pathol. 2002;197:519–526. doi: 10.1002/path.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heit JJ, Kim SK. Embryonic stem cells and islet replacement in diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2004;5 (Suppl 2):5–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa M, Matsuzaki Y, Nishikawa S, et al. Expression and function of c-kit in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 1991;174:63–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Besmer P, Manova K, Duttlinger R, et al. The kit-ligand (steel factor) and its receptor c-kit/W: Pleiotropic roles in gametogenesis and melanogenesis. Dev Suppl. 1993:125–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberg-Welsh C, Welsh M. Effects of certain growth factors on in vitro maturation of rat fetal islet-like structures. Pancreas. 1996;12:334–339. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBras S, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. A search for tyrosine kinase receptors expressed in the rat embryonic pancreas. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1474–1481. doi: 10.1007/s001250051094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rachdi L, El Ghazi L, Bernex F, et al. Expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT in mature beta-cells and in the pancreas in development. Diabetes. 2001;50:2021–2028. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.9.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yashpal NK, Li J, Wang R. Characterization of c-kit and nestin expression during islet cell development in the prenatal and postnatal rat pancreas. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:813–825. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang R, Li J, Yashpal N. Phenotypic analysis of c-kit expression in epithelial monolayers derived from postnatal rat pancreatic islets. J Endocrinol. 2004;182:113–122. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1820113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnamurthy M, Ayazi F, Li J, et al. c-kit in early onset of diabetes: A morphological and functional analysis of pancreatic beta-cells in c-KitW-v mutant mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5520–5530. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters K, Panienka R, Li J, et al. Expression of stem cell markers and transcription factors during the remodeling of the rat pancreas after duct ligation. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:56–63. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiemann K, Panienka R, Kloppel G. Expression of transcription factors and precursor cell markers during regeneration of beta cells in pancreata of rats treated with streptozotocin. Virchows Arch. 2007;450:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blume-Jensen P, Janknecht R, Hunter T. The kit receptor promotes cell survival via activation of PI 3-kinase and subsequent akt-mediated phosphorylation of bad on Ser136. Curr Biol. 1998;8:779–782. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timokhina I, Kissel H, Stella G, et al. Kit signaling through PI 3-kinase and src kinase pathways: An essential role for Rac1 and JNK activation in mast cell proliferation. EMBO J. 1998;17:6250–6262. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linnekin D. Early signaling pathways activated by c-kit in hematopoietic cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:1053–1074. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Dijk TB, van Den Akker E, Amelsvoort MP, et al. Stem cell factor induces phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-dependent Lyn/Tec/Dok-1 complex formation in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2000;96:3406–3413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rafiq I, da Silva Xavier G, Hooper S, et al. Glucose-stimulated preproinsulin gene expression and nuclear trans-location of pancreatic duodenum homeobox-1 require activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase but not p38 MAPK/SAPK2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15977–15984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.15977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Goodyer CG, Fellows F, et al. Stem cell factor/c-kit interactions regulate human islet-epithelial cluster proliferation and differentiation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:961–972. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Quirt J, Do HQ, et al. Expression of c-kit receptor tyrosine kinase and effect on beta-cell development in the human fetal pancreas. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E475–483. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00172.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hajduch E, Litherland GJ, Hundal HS. Protein kinase B (PKB/Akt)--a key regulator of glucose transport? FEBS Lett. 2001;492:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts MS, Woods AJ, Dale TC, et al. Protein kinase B/Akt acts via glycogen synthase kinase 3 to regulate recycling of alpha v beta 3 and alpha 5 beta 1 integrins. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1505–1515. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1505-1515.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jope RS, Johnson GV. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Z, Tanabe K, Bernal-Mizrachi E, et al. Mice with beta cell overexpression of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta have reduced beta cell mass and proliferation. Diabetologia. 2008;51:623–631. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0914-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Remedi MS, Pappan KL, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 and mammalian target of rapamycin pathways contribute to DNA synthesis, cell cycle progression, and proliferation in human islets. Diabetes. 2009;58:663–672. doi: 10.2337/db07-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Tanabe K, Baronnier D, et al. Conditional ablation of gsk-3beta in islet beta cells results in expanded mass and resistance to fat feeding-induced diabetes in mice. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2600–2610. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1882-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunick C, Lauenroth K, Leost M, et al. 1-azakenpaullone is a selective inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:413–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao Y, Ge X, Frank CL, et al. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;136:1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Bacquer O, Shu L, Marchand M, et al. TCF7L2 splice variants have distinct effects on {beta}-cell turnover and function. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1906–1915. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krishnamurthy M, Li J, Al-Masri M, et al. Expression and function of alphabeta1 integrins in pancretic beta (INS-1) cells. J Cell Commun Signal. 2008;2:67–79. doi: 10.1007/s12079-008-0030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Cron P, Good VM, et al. Crystal structure of an activated Akt/protein kinase B ternary complex with GSK3-peptide and AMP-PNP. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:940–944. doi: 10.1038/nsb870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nocka K, Tan JC, Chiu E, et al. Molecular bases of dominant negative and loss of function mutations at the murine c-kit/white spotting locus: W37, wv, W41 and W. EMBO J. 1990;9:1805–1813. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 7):1175–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kushner JA, Ciemerych MA, Sicinska E, et al. Cyclins D2 and D1 are essential for postnatal pancreatic beta-cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3752–3762. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3752-3762.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukherji A, Janbandhu VC, Kumar V. GSK-3beta-dependent destabilization of cyclin D1 mediates replicational stress-induced arrest of cell cycle. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1111–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanabe K, Liu Z, Patel S, et al. Genetic deficiency of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta corrects diabetes in mouse models of insulin resistance. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rulifson IC, Karnik SK, Heiser PW, et al. Wnt signaling regulates pancreatic beta cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6247–6252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701509104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Figeac F, Uzan B, Faro M, et al. Neonatal growth and regeneration of beta-cells are regulated by the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in normal and diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E245–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00538.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee G, Goretsky T, Managlia E, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling mediates beta-catenin activation in intestinal epithelial stem and progenitor cells in colitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:869–881. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, et al. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–995. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson JD, Ahmed NT, Luciani DS, et al. Increased islet apoptosis in Pdx1+/− mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(8):1147–1160. doi: 10.1172/JCI16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brissova M, Shiota M, Nicholson WE, et al. Reduction in pancreatic transcription factor PDX-1 impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11225–11232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauthier BR, Wiederkehr A, Baquie M, et al. PDX1 deficiency causes mitochondrial dysfunction and defective insulin secretion through TFAM suppression. Cell Metab. 2009;10:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boucher MJ, Selander L, Carlsson L, et al. Phosphorylation marks IPF1/PDX1 protein for degradation by glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6395–6403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphrey RK, Yu SM, Flores LE, et al. Glucose regulates steady-state levels of PDX1 via the reciprocal actions of GSK3 and AKT kinases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3406–3416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aguayo-Mazzucato C, Koh A, El Khattabi I, et al. Mafa expression enhances glucose-responsive insulin secretion in neonatal rat beta cells. Diabetologia. 2011;54:583–593. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-2026-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henriksen EJ, Kinnick TR, Teachey MK, et al. Modulation of muscle insulin resistance by selective inhibition of GSK-3 in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E892–900. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00346.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cline GW, Johnson K, Regittnig W, et al. Effects of a novel glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor on insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism in Zucker diabetic fatty (fa/fa) rat. Diabetes. 2002;51:2903–2910. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Eldar-Finkelman H. Long-term treatment with novel glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor improves glucose homeostasis in ob/ob mice: molecular characterization in liver and muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:17–24. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.090266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reith AD, Rottapel R, Giddens E, et al. W mutant mice with mild or severe developmental defects contain distinct point mutations in the kinase domain of the c-kit receptor. Genes Dev. 1990;4:390–400. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.