Abstract

The hAT superfamily comprises a large and diverse array of DNA transposons found in all supergroups of eukaryotes. Here we characterized the Drosophila buzzatii BuT2 element and found that it harbors a five-exon gene encoding a 643-aa putatively functional transposase. A phylogeny built with 85 hAT transposases yielded, in addition to the two major groups already described, Ac and Buster, a third one comprising 20 sequences that includes BuT2, Tip100, hAT-4_BM, and RP-hAT1. This third group is here named Tip. In addition, we studied the phylogenetic distribution and evolution of BuT2 by in silico searches and molecular approaches. Our data revealed BuT2 was, most often, vertically transmitted during the evolution of genus Drosophila being lost independently in several species. Nevertheless, we propose the occurrence of three horizontal transfer events to explain its distribution and conservation among species. Another aspect of BuT2 evolution and life cycle is the presence of short related sequences, which contain similar 5′ and 3′ regions, including the terminal inverted repeats. These sequences that can be considered as miniature inverted repeat transposable elements probably originated by internal deletion of complete copies and show evidences of recent mobilization.

Keywords: Drosophila, transposase, hAT, MITE, horizontal transfer

Introduction

Transposable elements (TEs) are widely distributed DNA sequences able to mobilize and increase their copy number within genomes. They are an important source of genetic variation in the genomes as a consequence of their insertion, domestication, and homologous recombination (Kidwell and Lisch 2001). Based on the transposition mechanism, via RNA or DNA intermediates, TEs can be classified into two major classes, retrotransposons (class I) and DNA transposons (class II), respectively (Finnegan 1989). These classes are further subdivided into subclass, order, superfamily, family, and subfamily, according to their sequence similarities and structural relationships (Wicker et al. 2007). Class II elements usually have terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) and encode a transposase that catalyzes their excision of the original site and promotes their reinsertion into a new place in the genome, generating target site duplications (TSDs; Wicker et al. 2007). The hAT superfamily comprise a large and diverse array of DNA transposons and related domesticated sequences found in all supergroups of eukaryotes including plants, animals, and fungi (Arensburger et al. 2011; Feschotte and Pritham 2007). Transposons of this superfamily are 2.5–5 kb in length, have relatively short TIRs (10–25 bp), and are flanked by 8-bp TSDs (Feschotte and Pritham 2007). Recently, the hAT superfamily was divided into two major groups or families, Ac and Buster, based on the primary sequence of their transposases and by differences in target-site selection (Arensburger et al. 2011). A small number of hAT transposons that do not fall into these two groups might comprise a third major group within the hAT superfamily (Arensburger et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2013).

Mobile elements are vertically transmitted through generations along with the rest of the genome. However, analyses of their distribution in different species showing inconsistencies between TE and species phylogenies suggest that horizontal transfer (HT) may take part of TE’s life cycle (Silva et al. 2004; Schaack et al. 2010; Wallau et al. 2012). Numerous cases of HT of TEs have been reported in Drosophila, involving elements from classes I and II, including members of the hAT superfamily, like the hobo element (Loreto et al. 2008).

Each TE class has both autonomous and nonautonomous elements. Autonomous elements have sequences encoding proteins needed for their transposition, whereas nonautonomous elements can be mobilized by enzymatic activities provided by autonomous elements. Miniature inverted repeat TEs (MITEs) encompass a particular group of class II nonautonomous elements. They are short sequences with no coding capacity and conserved TIRs that often reach high copy numbers in the genomes and are found within or near genes (Feschotte and Pritham 2007). They were first discovered in plants (Bureau and Wessler 1992) but are also found in several animal genomes, including Drosophila (Holyoake and Kidwell 2003; Ortiz et al. 2010; Dias and Carareto 2011; Deprá et al. 2012; Rius et al. 2013). The origin of some MITE families is unclear. Some of them seem to be derived from autonomous copies (Jiang et al. 2003, 2004; Zhang et al. 2004; Ortiz and Loreto 2008; Deprá et al. 2012) although others are apparently the result of recombination events producing a pair of TIRs that are equal or similar to those of an autonomous element that will provide the transposase for MITE mobilization (Jiang et al. 2004).

In the genus Drosophila, TE insertions have often been found in the breakpoints of chromosomal inversion (Lim 1988; Lyttle and Haymer 1992; Eggleston et al. 1996; Regner et al. 1996; Evgen’ev et al. 2000; Cáceres et al. 2001). Cáceres et al. (2001) characterized the breakpoints of a Drosophila buzzatii polymorphic inversion, which have accumulated insertions of several different TEs. One of them, called BuT2, was tentatively classified in the hAT superfamily of class II transposons. This element is relatively scarce in the D. buzzatii genome (Casals et al. 2006), but its presence in the inversion breakpoints indicates recent transpositional activity. In this work, we seek to characterize the BuT2 element and contribute to the knowledge of hAT superfamily evolution. We found that BuT2 harbors a five-exon gene encoding a 643-aa transposase and phylogenetically classify it in the third major group of hAT transposons that we named the Tip family. By in silico searches in genomes and molecular biology approaches, we conducted a screening covering 105 insect species, of which 72 belong to the genus Drosophila. Our results show BuT2 sequences are present in five Drosophila groups and were horizontally transmitted between some of them. We also found in some species short nonautonomous sequences related to BuT2. These sequences have conserved TIRs and probably originated by deletion of BuT2 autonomous copies and may represent the rising of a MITE family.

Materials and Methods

In Silico Searches on Insect Genomes

We investigated the presence of BuT2 homologous sequences in 21 sequenced Drosophila genomes and in 27 other insect genomes (table 1). These genomes are deposited in the FlyBase database (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/blast/, last accessed February 4, 2014; Grumbling and Strelets 2006). Drosophila buzzatii canonical BuT2 nucleotide sequence (GenBank AF368884) was used as query on BlastN and TBlastX. We used an e-value cutoff of 1e-20. To calculate the average similarity between BuT2 and the sequences found, the similarity information of all high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) from the significant hits were used.

Table 1.

Number of Significant Hits Found Using BlastN and TBlastX Tools in Flybase and the Percent Average Similarity Found with the Query

| Species |

BlastN |

TBlastX |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hits | Average Similarity | Hits | Average Similarity | |

| D. melanogaster | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| D. simulans | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| D. sechellia | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| D. yakuba | 0 | – | 8 | 53.16 |

| D. erecta | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| D. ficusphila | 3 | 81.90 | 26 | 52.81 |

| D. eugracilis | 1 | 82.63 | 10 | 55.03 |

| D. biarmipes | 0 | – | 11 | 51.21 |

| D. takahashii | 0 | – | 7 | 47.33 |

| D. elegans | 0 | – | 5 | 50.75 |

| D. rhopaloa | 0 | – | 16 | 51.30 |

| D. kikkawai | 2 | 81.83 | 29 | 54.94 |

| D. ananassae | 0 | – | 10 | 49.91 |

| D. bipectinata | 1 | 82.60 | 46 | 52.86 |

| D. pseudoobscura | 0 | – | 6 | 48.76 |

| D. persimilis | 0 | – | 10 | 49.17 |

| D. miranda | 0 | – | 2 | 48.99 |

| D. willistoni | 28 | 87.48 | 55 | 65.50 |

| D. mojavensis | 3 | 90.17 | 28 | 56.54 |

| D. virilis | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| D. grimshawi | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Culex quinquefasciatus | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| A. aegypti | 0 | – | 8 | 38.54 |

| An. gambiae | 0 | – | 1 | 41.82 |

| Mayetiola destructor | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| B. mori | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Danaus plexippus | 0 | – | 1 | 41.96 |

| T. castaneum | 0 | – | 32 | 42.47 |

| N. giraulti | 0 | – | 11 | 42.23 |

| N. longicornis | 0 | – | 15 | 41.43 |

| N. vitripennis | 0 | – | 27 | 41.6 |

| Apis mellifera | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Apis florea | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Bombus impatiens | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Bombus terrestris | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Megachile rotundata | 0 | – | 5 | 39.27 |

| Acromyrmex echinatior | 0 | – | 9 | 45.06 |

| Atta cephalotes | 0 | – | 1 | 38.74 |

| C. floridanus | 0 | – | 7 | 38.93 |

| Harpegnathos saltator | 0 | – | 10 | 37.68 |

| Linepithema humile | 0 | – | 24 | 38.88 |

| Pogonomyrmex barbatus | 0 | – | 2 | 46.91 |

| Solenopsis invicta | 0 | – | 83 | 43.16 |

| A. pisum | 0 | – | 59 | 43.43 |

| R. prolixus | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Pediculus humanus corporis | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Ixodes scapularis | 0 | – | 54 | 43.22 |

| Rhipicephalus microplus | 0 | – | 0 | – |

Note.–The query sequence was the canonical But2 sequence from D. buzzatii.

The presence of short sequences related to BuT2 was investigated by in silico polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the BlastN tool against all 21 Drosophila genomes. The query was a sequence formed by the BuT2_F primer followed by the reverse complementary sequence of BuT2_R primer. These primers are described below. Hits that visibly contained both regions of these primers, which correspond in part to the BuT2 TIRs, were analyzed looking for conserved TIRs and TSDs.

The identity of sequences and some insertions found in BuT2 copies was investigated by Blast tool against the GenBank (Altschul et al. 1990) or using CENSOR (Kohany et al. 2006), a software tool that screens query sequences against the Repbase Update (Jurka et al. 2005), a database of repetitive sequences eukaryotes.

Fly Stocks and DNA Manipulation

Flies are maintained in laboratory by mass crosses and cultivated in corn flour culture medium in a constant temperature chamber (20 °C). Genomic DNA was extracted from adult flies as described (Sassi et al. 2005). A total of 67 species (table 2) belonging to genus Drosophila, Zaprionus, and Scaptodrosophila were used in the laboratory experimental approaches. One strain of each species was used, and their origin information is available in the supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online.

Table 2.

Drosophilidae Species Investigated by PCR, Dot Blot, and BlastN Approaches, with Their Taxonomic Placement and Respective Results

| Genus | Subgenus | Group | Species | PCR |

Dot | BlastN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Drosophila | Drosophila | guarani | D. ornatifrons | − | − | w | na |

| D. subbadia | − | − | w | na | |||

| D. guaru | − | − | w | na | |||

| grimshawi | D. grimshawi | − | − | na | − | ||

| guaramuru | D. griseolineata | − | − | − | na | ||

| D. maculifrons | − | − | − | na | |||

| tripunctata | D. nappae | − | − | w | na | ||

| D. paraguayensis | − | − | na | na | |||

| D. crocina | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. paramediostriata | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. tripunctata | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. mediodiffusa | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. mediopictoides | − | − | − | na | |||

| cardini | D. cardini | − | − | na | na | ||

| D. cardinoides | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. neocardini | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. polymorpha | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. procardinoides | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. arawakana | − | − | − | na | |||

| pallidipennis | D. pallidipennis | + | + | + | na | ||

| calloptera | D. ornatipennis | − | − | w | na | ||

| immigrans | D. immigrans | − | − | − | na | ||

| funebris | D. funebris | − | − | − | na | ||

| mesophragmatica | D. gasici | − | − | − | na | ||

| D. brncici | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. gaucha | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. pavani | − | − | − | na | |||

| repleta | D. hydei | − | − | − | na | ||

| D. mojavensis | − | − | + | + | |||

| D. buzzatii | + | + | + | na | |||

| D. mercatorum | − | − | + | na | |||

| D. repleta | − | − | na | na | |||

| canalinea | D. canalinea | − | − | na | na | ||

| flavopilosa | D. cestri | − | − | na | na | ||

| D. incompta | − | − | + | na | |||

| virilis | D. virilis | − | − | − | − | ||

| robusta | D. robusta | − | − | − | na | ||

| Sophophora | melanogaster | D. melanogaster | − | − | − | − | |

| D. simulans | − | − | − | − | |||

| D. sechellia | − | − | na | − | |||

| D. mauritiana | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. teissieri | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. santomea | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. erecta | − | − | − | − | |||

| D. yakuba | − | − | − | − | |||

| D. kikkawai | − | − | w | + | |||

| D. ananassae | − | − | − | − | |||

| D. malerkotliana | − | − | w | na | |||

| D. orena | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. ficusphila | na | na | na | + | |||

| D. eugracilis | na | na | na | + | |||

| D. biarmipes | na | na | na | − | |||

| D. takahashii | na | na | na | − | |||

| D. elegans | na | na | na | − | |||

| D. rhopaloa | na | na | na | − | |||

| D. bipectinata | na | na | na | + | |||

| obscura | D. pseudoobscura | − | − | − | − | ||

| D. persimilis | na | na | na | − | |||

| D. miranda | na | na | na | − | |||

| saltans | D. prosaltans | − | + | + | na | ||

| D. saltans | − | + | + | na | |||

| D. neoelliptica | − | − | w | na | |||

| D. sturtevanti | − | + | w | na | |||

| willistoni | D. sucinea | + | − | + | na | ||

| D. nebulosa | + | − | + | na | |||

| D. paulistorum | + | − | + | na | |||

| D. willistoni | + | + | + | + | |||

| D. equinoxialis | + | − | + | na | |||

| D. insularis | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. tropicalis | − | − | − | na | |||

| D. capricorni | + | − | + | na | |||

| Dorsilopha | D. busckii | − | − | − | na | ||

| Zaprionus | Z. indianus | − | − | − | na | ||

| Z. tuberculatus | − | − | − | na | |||

| Z. sepsoide | − | − | na | na | |||

| Scaptodrosophila | S. latifasciaeformis | − | − | na | |||

| S. lebanonensis | − | − | na | ||||

Note.— −, no amplification, hybridization signal, or significant hit on BlastN obtained; +, positive amplification, hybridization signal, or significant hit on BlastN; w, weak signal in the dot blot; na, not available/analyzed.

Dot Blot

We used dot blot to investigate the presence of BuT2 in 60 Drosophilidae species (table 2). Approximately 1 μg of genomic DNA, denatured by heat, was applied directly on a nylon membrane (Hybond-N+, GE Healthcare). Hybridization and detection followed the protocol of the kit CPD-Star Detection Module (GE Healthcare). The PCR fragment amplified from a D. willistoni BuT2 clone (Bf2_Dwil1) was used as probe and was labeled with the Gene Images Kit AlkPhos Direct Labelling Module (GE Healthcare). The hybridization temperature was 55 °C.

PCR Screening

PCR approach was also used to investigate the presence of BuT2 in 67 Drosophilidae species (table 2). Four different primers were designed (fig. 1A). Primers BuT2_F 5′ CAGTGCTGCCAACAWTTYGT 3′ and BuT2_R 5′ CASTGCTGCCAATTTAGCYA 3′ were designed based on three sequences: the canonical BuT2 element from D. buzzatii (AF368884.1), the BuT2 sequence located in the scf2_1100000004958:2664879-26680344 (scf1_Dwil) of D. willistoni genome, and the one located in the scaffold_3367: 3535-7555 (scf1_Dmoj) of D. mojavensis genome. These primers were designed to amplify the complete BuT2 element and are degenerated in some positions. Two other primers were designed based on the same sequences cited above from D. buzzatii and D. willistoni. The nucleotide sequences are: BuT2C_F 5′ AGACYTCGGGRACAGTTTTGC 3′ and BuT2C_R 5′ AGCATTAATGCYAARCTTTC 3′. The following protocol for the PCR reactions was used: 50 ng of genomic DNA added to a solution of 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1× buffer reaction, 200 mM of each deoxynucleotide, 20 pmol of each primer, and 1 U of Taq polymerase in 50 µl of total volume. The condition of reactions were 96 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 96 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1–3 min, depending on the expected size of the fragment. PCR products were cloned using TOPO TA cloning system (Invitrogen) and selected clones were sequenced from PCR products purified with Exonuclease I (USB) and Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (USB) on MegaBACE 500 automated sequencer or by a sequencing service (www.macrogen.com, last accessed February 7, 2014).

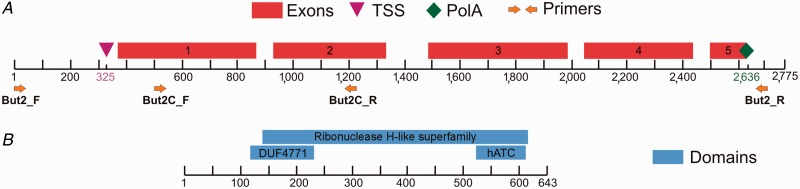

Fig. 1.—

Schematic representation of BuT2 nucleotide and predicted protein. A: Organization of D. buzzatii BuT2 coding sequences, TSS, transcription start site; Exons 1–5; PolA, polyadenylation signal. Arrows indicate the primer annealing regions. B: Organization of D. buzzatii BuT2 predicted amino acid sequence with the domains found.

Searching for a Transposase Coding Region within BuT2

To check whether the complete copies of the BuT2 potentially encodes for a functional transposase, we used three programs to predict the existence of possible introns and coding regions: GeneMark.hmm (Lomsadze et al. 2005), GENSCAN (Burge and Karlin 1997), and FGENESH (Yao et al. 2005). The Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) (Letunic et al. 2009, 2012) and InterProScan (Quevillon et al. 2005) tools were used to check for domains in the predicted protein sequences.

Sequence Analysis

Nucleotide sequences were aligned using Muscle (Edgar 2004) and BuT2 phylogeny was inferred by three methods: Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and maximum likelihood (ML) using the Tamura 3-parameter substitution model (Tamura 1992) with gamma parameter equaling 3.0 as indicated by model selection analysis and Bayesian analysis (BA) with parameters set to nst = 2 using a gamma distribution. NJ and ML trees were implemented in Mega5.2 (Tamura et al. 2011), and 1,000 replicates bootstrap was used to access the reliability of branches. BA was implemented in MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist et al. 2012) with at least 1,000,000 generations and a burn-in of 25%.

We also investigated the phylogenetic placement of BuT2 transposase using the transposase amino acid sequences from several hAT superfamily members collected based on Arensburger et al. (2011). We also carried out BlastP searches using as query the predicted BuT2 transposase amino acid sequence against all nonredundant protein sequences. We retrieved all sequences with a minimum identity of 30% and minimum coverage of 60% with an e-value cutoff of 5e-20. The accession numbers of these sequences are listed in supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online. Protein sequences were aligned using M-Coffee, which computes a consensus alignment from several multiple sequence alignment programs (Moretti et al. 2007). Conserved regions in the alignment were selected to infer the transposase phylogeny. We performed ML and NJ using the rtREV model (Dimmic et al. 2002) + G + F, as indicated by model selection implemented on Mega5.2 (Tamura et al. 2011).

Sequences of two genes alpha methyl dopa (Amd) and alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh) were used to compare their divergence with those found for BuT2 sequences with the purpose of testing the HT hypothesis. P-distance between sequences was calculated for BuT2 and for the nuclear genes using Mega5.2 (Tamura et al. 2011). Adh and Amd genes sequences were obtained from GenBank or by BlastN against the genomes. Accession numbers or scaffold coordinates are given in supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online. A χ2 test was used to verify whether the divergence observed for BuT2 between species is significantly different from the expected divergence based on nuclear genes Adh or Amd. Vertical transmission (VT) can be assumed if the BuT2 divergence is greater or equal than those from the nuclear genes. On the other hand, if the BuT2 divergence is smaller than the nuclear gene divergence, HT can be suggested. Similar approach was already used to investigate HT events (Ludwig and Loreto 2007).

Results

BuT2 from D. buzzatii Encodes a Putatively Functional Transposase

A single copy of the D. buzzatii transposon BuT2 has been described (Cáceres et al. 2001). It is 2,775-bp long, possesses 12-bp TIRs, and is flanked by 8-bp TSDs. We searched this copy for sequences encoding the transposase using three de novo gene predictors. FGENESH software predicted a transcription start site (TSS) at position 325, five exons (nucleotide positions: 366–864; 925–1331; 1486–1985; 2044–2436; 2495–2627) encoding a 643-aa protein and a polyadenylation signal at position 2636 (fig. 1A). Similarly, GeneMark.hmm and GENSCAN predicted five-exon genes but encoding somewhat shorter proteins (599 and 520-aa, respectively). We choose FGENESH as the best prediction because the protein is longer and similar in size to many other transposases of active hAT transposons, for instance, those of hobo element in the fruit fly D. melanogaster (658 aa; Calvi et al. 1991), Hermes in Musca domestica (612 aa; Warren et al. 1994), or TcBuster in Tribolium castaneum (636 aa; Arensburger et al. 2011). In addition, bioinformatic and phylogenetic observations (see later) support that this is likely the correct BuT2 transposase.

We used two different computer programs to search for domains within the 643-aa BuT2 protein (fig. 1B). SMART showed the presence of a hATC domain in residues 515–603 (e-value = 2.8e-06), which is a highly conserved dimerization domain (pfam05699) found in DNA transposons from the hAT superfamily (Essers et al. 2000). InterProScan found, in addition to the hAT dimerization domain, a domain of unknown function DUF4371 in residues 116–229 (e-value = 1.8e-8) and a Ribonuclease H-like superfamily domain (SSF53098) in residues 138–608 (e-value = 4.4e-24). This is a structural domain consisting of a three-layer alpha/beta/alpha fold that contains mixed beta sheets and is found in some ribonucleases, retroviral integrases, transposases, and exonuclease, suggesting they share a similar mechanism of catalysis (Gough et al. 2001). We conclude D. buzzatii BuT2 encodes a putatively functional transposase related to those of the hAT superfamily.

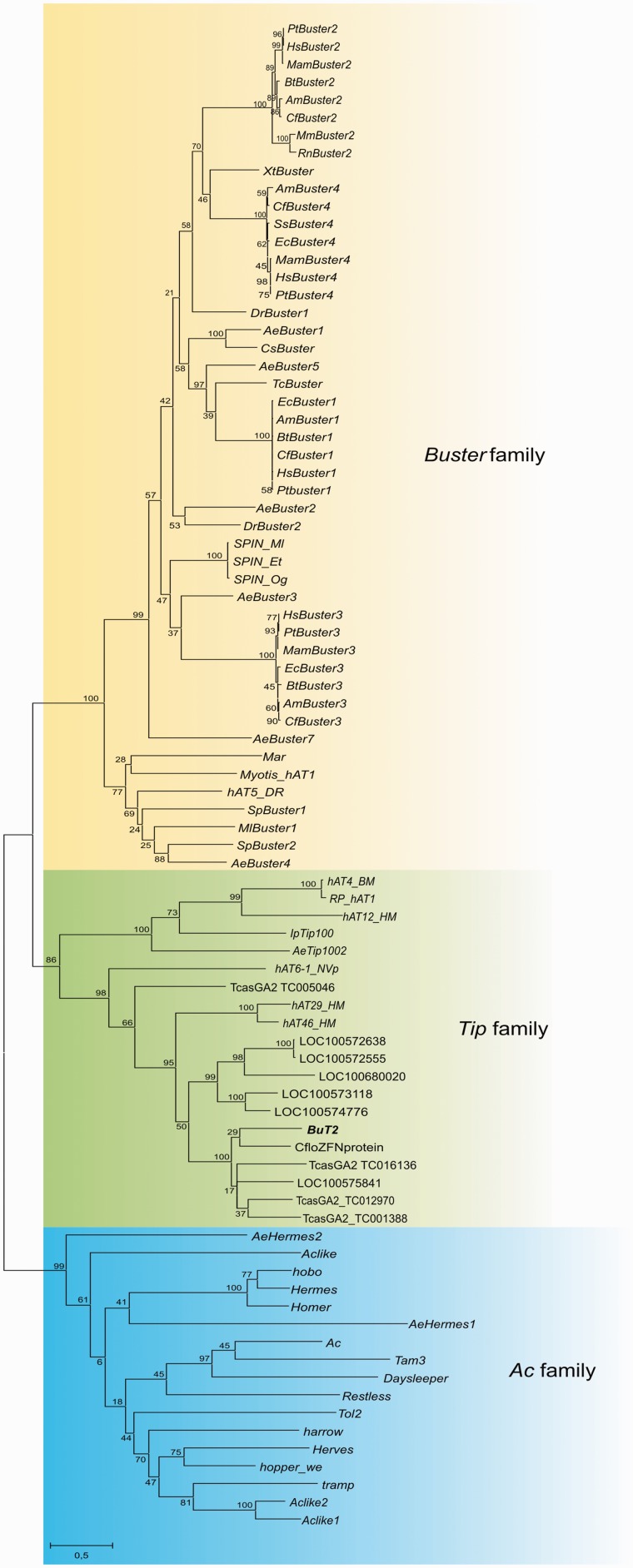

BuT2 Belongs to the Third Major Group of hAT Transposons

The hAT superfamily comprises a complex array of transposons found in diverse eukaryotic supergroups (Feschotte and Pritham 2007; Arensburger et al. 2011). Two main groups, named Buster and Ac, were established by Arensburger et al. (2011). Recently, Zhang et al. (2013) described a novel hAT element horizontally transmitted between Bombyx mori (hAT-4_BM) and Rhodnius prolixus (RP-hAT1), which might represent a third group well separated from the previous ones, Buster and Ac. In order to establish the relationships of BuT2 with the other members of the hAT superfamily, we built a phylogeny with the transposase amino acid sequences described previously (Arensburger et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2013) along with other 14 homologous sequences (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). These new sequences correspond to three proteins annotated in Repbase as belonging to hAT transposons (hAT-29_HM and hAT-46_HM from Hydra magnipapillata and hAT6-1_NVp from Nasonia vitripennis) and four proteins of T. castaneum, five proteins of Acyrthosiphon pisum, and one protein of Camponotus floridanus and N. vitripennis retrieved from Protein databases by a BlastP search. None of the latter sequences has been annotated as a transposase, although all of them contain the hATC dimerization domain. The phylogenetic tree revealed three major clades with many members in each clade (fig. 2). Two of them correspond to the known groups Ac and Buster, whereas the third clade comprises 20 proteins including the transposases of BuT2, Tip100, hAT-4_BM, and RP-hAT1. This third major group has been here named as the Tip group after the transposon Tip100 from the common morning glory Ipomoea purpurea (Habu et al. 1998). BuT2 is the only transposon from the Tip group known in Drosophila.

Fig. 2.—

Unrooted ML phylogenetic tree of hAT elements amino acid transposase sequences. Node supports are bootstrap values (1,000 replications). The three proposed hAT families, Ac, Buster, and Tip are shown.

In Silico Searches Reveal the Presence of BuT2 in the melanogaster, repleta, and willistoni Species Groups

We searched for sequences similar to BuT2 in the genomes of 21 Drosophila species and 27 other insects available in FlyBase (table 1) using BlastN. Significant hits (number in parentheses) were found in D. ficusphila (3), D. eugracilis (1), D. kikkawai (2), D. bipectinata (1), D. mojavensis (3), and D. willistoni (28). Information about the length and scaffold position of these sequences is given in supplementary table S4, Supplementary Material online. Sequences similar to BuT2 in the four species of the melanogaster group (D. ficusphila, D. eugracilis, D. kikkawai, D. bipectinata) are relatively short (165–836 bp) with identity ∼80%. Furthermore, none of these sequences seems to include TIRs nor is flanked by TSDs.

In D. mojavensis, which belongs to the repleta group of Drosophila subgenus as D. buzzatii, we found only three significant hits (supplementary table S4, Supplementary Material online). The most complete copy is 4,017-bp long, has 12-bp TIRs (with two mismatches), and is flanked by identical 8-bp TSDs. This copy is 91.2% identical to D. buzzatii BuT2 copy but has a deletion of 392 bp and an insertion of approximately 1,700 bp (likely a mariner element as identified by CENSOR). The other two copies in D. mojavensis are incomplete and have, respectively, 4,928 bp and 1,128 bp. The large size of the 4,928-bp copy is due to one large insertion (∼2,600 bp).

In D. willistoni, a species belonging to the subgenus Sophophora, we retrieved 28 significant hits, but only two copies appear to have large segments of the transposase (supplementary table S4, Supplementary Material online). The remaining copies were smaller (800–1,000 bp) and seemed to lack the internal portion of the element (coding for the transposase) but conserve the outermost portions (that are presumably required for transposition). Therefore, there seem to be nonautonomous copies generated by deletion (see later). The most complete copy has 3,156 bp length including 12-bp TIRs and is flanked by 8-bp TSDs (with one mismatch). This copy is 92.4% identical to D. buzzatii BuT2 and harbors a similar five-exon gene with conserved splice sites and encoding a 642-aa protein that is 90% identical to that of D. buzzatii (after correction of a mutation in the first exon that generates a stop codon). This D. willistoni copy is longer than that of D. buzzatii because it possesses within intron 2 an insertion of 424 bp (seemingly a BEL LTR retrotransposon as identified by CENSOR). The other copy has 6,093-bp length, including a deletion of 355 bp and an insertion of approximately 4,200 bp (a Minos transposon according to CENSOR). The BuT2 most complete copies of D. buzzatii, D. mojavensis, and D. willistoni show, after removal of secondary TE insertions, an unexpected identity (>90%) raising the hypothesis of HT among the species (see later).

Additional bioinformatic searches were carried out using TBlastX, a more sensitive search, because it uses translated DNA queries and subjects and compares the resulting amino acid translations. Significant hits were recovered, in addition to the species already known to harbor BuT2 sequences, in D. yakuba, D. biarmipes, D. takahashii, D. elegans, D. rhopaloa, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. persimilis, and D. miranda. Significant hits were also found in 17 other insect genomes (table 1). However, all these sequences present low identity with BuT2 element (in general, less than 50% of amino acid identity), suggesting these sequences may correspond to other hAT elements rather than BuT2.

Experimental Searches Show a Patchy Distribution of BuT2 among Drosophilid Species

We used dot blot hybridization to test for the presence of sequences similar to BuT2 in 60 Drosophilid species (table 2). Results are shown on supplementary figure S1, Supplementary Material online. Dot blot filters showed strong hybridization signals in three species known to harbor BuT2 (see above) and included as positive controls: D. buzzatii, D. mojavensis, and D. willistoni. In contrast, no hybridization signals were found in four species known to lack BuT2 (see above) and included here as negative controls: D. virilis, D. melanogaster, D. erecta, and D. simulans. In addition, we observed strong hybridization signals in all species of the sister groups willistoni and saltans, as well as in D. pallidipennis (pallidipenis species group) and D. incompta (flavopilosa species group). Other species showed a weak signal, including D. kikkawai, that presented a sequence similar to BuT2 by in silico searches.

We also used two PCR assays in 67 Drosophilid species to investigate the distribution of BuT2 (table 2). In PCR 1, we used primers BuT2_F and BuT2_R, expected to amplify the complete BuT2 element (∼2,770 bp), as shown in figure 1A. The amplified fragments with these primers were much smaller than expected and had a variable size among species, even within the same species group. None of the species showed an amplification corresponding to a complete element. These small fragments were cloned and sequenced, and all of them correspond to small sequences related to BuT2. Possibly, due to their smaller size and perhaps larger frequency in the genomes, these fragments are amplified with preference to the complete element, if present. The presence of small sequences related to BuT2 was confirmed by in silico PCR in the D. willistoni genome that recovered 24 short sequences, with size ranging from 532 to 927 bp with an average (±SD) = 739 bp (±108). Most (18) of these sequences present TIRs highly similar to those of the complete BuT2 copy and 14 are flanked by identical TSDs (supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). For instance, the copy in scaffold_4830 (Scf13_Dwil) is 773-bp long and is 96.8% identical to BuT2 in the first 94 nt and 95.3% identical in the terminal 128 nt. The high similarity in the outermost sequences, including TIRs, is very significant, because these sequences are presumably required for transposition.

Looking for complete BuT2 copies, the same collection of species was screened by PCR 2, with additional primers BuT2C_F and BuT2C_R covering a 750-bp central region of element BuT2 (fig. 1). Table 2 shows the PCR results for both fragments. Amplicons were cloned and sequenced for the following species: Fragment 1, D. pallidipennis, D. buzzatii, D. sucinea, D. nebulosa, D. paulistorum, D. capricorni, D. equinoxialis; Fragment 2: D. willistoni, D. buzzatii and D. pallidipennis, D. prosaltans, D. saltans, D. sturtevanti and D. willistoni. The GenBank accession numbers of these are shown in supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online.

Our data show that BuT2 has a patchy distribution among Drosophila species being found in species from five species groups: pallidipennis and repleta of subgenus Drosophila and melanogaster, saltans, and willistoni from subgenus Sophophora. Nevertheless, we cannot discard the possibility of BuT2 presence in some other group not tested in this work, and divergences in the primer regions may have led to a negative PCR result for some species harboring BuT2. It could have happened to D. incompta, D. insularis, and D. tropicalis, which showed a relatively strong hybridization signal in dot blot.

BuT2 Phylogenetic and Divergence Analyses

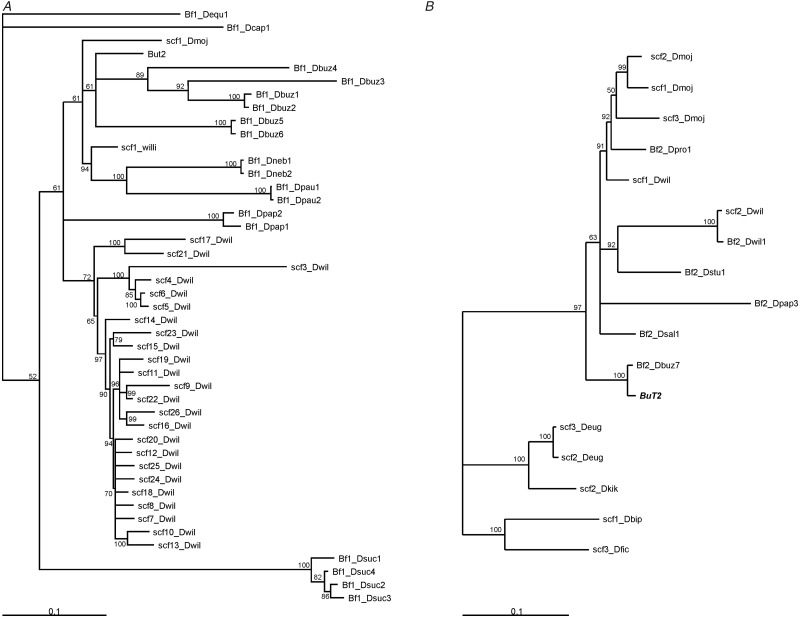

All amplicons generated with primers BuT2_F and BuT2_R can be considered as MITEs because they contain only the boundaries of BuT2 element, including TIRs. These sequences together with those obtained by in silico PCR and the corresponding homologous region of complete elements from D. buzzatii, D. willistoni, and D. mojavensis were used to construct a phylogeny (fig. 3A). The phylogenetic methods applied, NJ, MP, and BA, showed similar trees with low support of branches, which hampers the interpretation of relationships among species. When nodes with bootstrap or posterior probabilities values below 50% were forced to collapse, the phylogeny became almost an entire polytomic tree (not shown). The only well-established relationships are some species-specific clades grouping the sequences of D. sucinea, D. buzzatii, D. willistoni, and a clade grouping together sequences of D. willistoni, D. nebulosa, and D. paulistorum. The 24 MITE sequences from D. willistoni are grouped in the tree in a single clade somewhat separated from the complete copy and the short length of some branches indicates those copies are very similar, suggesting recent amplification.

Fig. 3.—

Phylogenetic relationships of BuT2 copies and associated MITE sequences. A: BA of the BuT2 short sequences obtained using the BuT2_F and BuT2_R primers (Bf1) and by in silico PCR (scf). B: BA of BuT2 copies obtained with the primers BuT2C_F and BuT2CR (Bf2) and by in silico searches (scf). Node supports are shown by posterior probability (only above 50%). Drosophila buzzatii BuT2 canonical sequence is shown in boldface. The species are the following: Dequ, D. equinoxialis; Dcap, D. capricorni; Dmoj, D. mojavensis; Dbuz, D. buzzatii; Dwil, D. willistoni; Dneb, D. nebulosa; Dpau, D. paulistorum; Dpap, D. pallidipennis; Dsuc, D. sucinea; Dfic, D. ficusphila; Dbip, D. bipectinata; Dsal, D. saltans; Dstu, D. sturtevanti; Dpro, D. prosaltans; Dkik, D. kikkawai; Deug, D. eugracilis.

Sequences of fragments amplified with BuT2C_F and BuT2C_R were also used to infer a BuT2 phylogeny (fig. 3B). NJ, MP, and BA phylogenies also showed similar trees, and the relationship between several species is unclear, because bootstrap and posterior probabilities values are very low for some branches. We can observe a confident clade grouping D. prosaltans and D. mojavensis and another one containing D. sturtevanti and D. willistoni. Both clades clustered with sequences from D. pallidipennis, D. saltans, and D. buzzatii BuT2. Another clade contains sequences of D. kikkawai and D. eugracilis.

Both phylogenies present low resolution in several nodes, and it may be inherent of this transposon sequence if relationships may not be demonstrated by simple branch bifurcations in the trees. It can represent multiple/simultaneous divergence events (Maddison 1989).

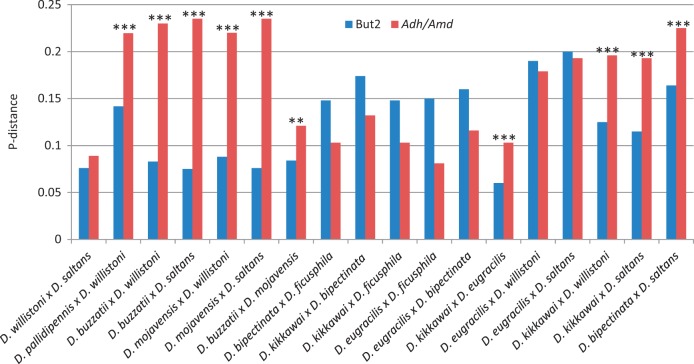

In order to test HT hypothesis, we compared the interspecific divergence found among the BuT2 sequences, with the divergence of the nuclear genes Adh and Amd. Given the functional relevance of these genes, it is expected that they are under high selective constraints. Thus, theoretically, HT events can be inferred when the divergence of BuT2 is significantly lower to the divergence found for these genes. Pairwise divergences for BuT2 and genes were estimated for all species, and the most relevant comparisons are shown in figure 4.

Fig. 4.—

Comparative analysis of the divergence found among the BuT2 sequences and the nuclear genes Adh and Amd. A χ2 test was used to verify whether the BuT2 observed divergence is significantly different from the expected based on the Adh and Amd genes. Results of χ2 test: ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01.

All comparisons between species from saltans group and D. willistoni show, for BuT2, similar or greater divergence than those for the genes. In figure 4 is exemplified the comparison of D. willistoni and D. saltans, showing nonsignificant difference for BuT2 and Adh divergence, corroborating our hypothesis of the BuT2 presence in the ancestor of willistoni and saltans groups followed by VT during speciation processes.

Drosophila pallidipennis has no Adh sequence available, then we used the Amd gene, and the comparison with D. willistoni shows much smaller divergence for BuT2 than the expected based on Amd divergence, suggesting HT.

BuT2 sequences from D. buzzatii and D. mojavensis are much more similar to all those from willistoni and saltans species than would be expected for VT based on Adh gene (fig. 4). We also compared D. buzzatii with D. mojavensis (Adh gene), and these comparisons also show BuT2 divergences are significantly lower than the gene divergence.

The relationships of BuT2 sequences are more complex to understand when we consider the melanogaster group where these sequences are present in four species with a scattered distribution and phylogenetic inconsistencies. The results of BuT2 and Adh divergence pairwise comparisons among D. ficusphila, D. bipectinata, D. kikkawai, and D. eugracilis indicate VT, except for D. kikkawai and D. eugracilis that indicates HT. Comparisons among these species with D. willistoni and D. saltans indicate VT for most of comparisons (comparisons of D. eugracilis with D. willistoni and D. saltans are exemplified in fig. 4). HT was suggested for the comparisons of D. willistoni and D. saltans with D. kikkawai and for D. bipectinata with D. saltans; however, BuT2 sequences of these two species are very short and the results may be probably biased.

Discussion

Drosophila buzzatii BuT2 Encodes a Putatively Functional Transposase and Belongs to the Third Major Group of hAT Transposons

Our results from gene prediction programs suggest that the BuT2 copy of D. buzzatii encodes a putatively active transposase, which is in agreement with the recent transpositional activity inferred in this species. BuT2 transposase is 643-aa long and contains a hATC domain, which is a highly conserved dimerization domain found in DNA transposases from the hAT superfamily (Essers et al. 2000). The most complete BuT2 copy found in D. willistoni similarly encodes a 642-aa protein that is 90% identical to that of D. buzzatii. However, this copy cannot be active because it contains a nonsense mutation that results in a premature stop codon. Because the genome sequence only represents a single D. willistoni genome, we cannot discard the existence of active copies in other individuals or populations within this widely distributed species. As a matter of fact, the presence of many short MITE-like sequences associated to BuT2 in D. willistoni genome (see later) suggests recent transpositional activity in this species.

The hAT superfamily is a very large and diverse group of DNA transposons and domesticated genes, as there are several examples of hAT superfamily elements being exapted to essential functions within the host genome (Sinzelle et al. 2009; Arensburger et al. 2011). As we mentioned before, the hAT superfamily consists of at least two families, Ac and Buster, based on the phylogeny of their transposases and by difference in target-site selection (Arensburger et al. 2011). Recently, Zhang et al. (2013) suggested a third group with a small number of elements that would include Tip100 and two transposons from B. mori (hAT_-4_BM) and R. prolixus (RP-hAT1) (Zhang et al. 2013). In this work, the unrooted hAT transposase tree more clearly shows the presence of a third large group, comprising at least 20 sequences including BuT2, Tip transposons, hAT_-4_BM, and RP-hAT1. Thus, we propose to establish a new family of hAT transposons, named the Tip family. TSD size in this family (8 bp) seems to be similar to that of the other two, but we have not investigated the target preference that differentiates the Ac and Buster groups. Further studies of the Tip elements TSDs would be interesting to detect if there are similarities in the target-site selection among Tip elements and differences with Ac and Buster members. The Tip family contains sequences coming from a phylogenetically diverse array of hosts, such as Tip100 of the common morning glory I. purpurea (Habu et al. 1998), AeTip100-2 of the mosquito Aedes aegypti (Arensburger et al. 2011), hAT-12_HM of hydra H. magnipapillata (Jurka 2008) and BuT2 of Drosophila (Cáceres et al. 2001). Here we show several other hypothetical proteins from insects are included in Tip clade; however, we cannot determine whether these are active TEs or domesticated genes. Up to now, Tip family elements are found in plants, Cnidaria, and insects from different orders Lepidoptera, Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, and Diptera. Possibly, with the advancement of genome projects, other Tip elements will be described soon.

In insects, several hAT elements were characterized, such as hobo in D. melanogaster (Calvi et al. 1991), Hermes in M. domestica (Warren et al. 1994), Hermit in Lucilia cuprina (Coates et al. 1996), Homer in Bactrocera tryoni (Pinkerton et al. 1999), Hopper in Ba. dorsalis (Handler 2003) and Herves in An. gambiae (Arensburger et al. 2005). Other hAT sequences were identified, by Ortiz and Loreto (2008), through in silico searches in 12 Drosophila genomes. Most of Drosophila hAT elements belong to Ac family, and recently we characterized the first Buster element found in Drosophila (Deprá et al. 2012). Here we describe the first Tip element in Drosophila.

MITE-Like Sequences Associated to BuT2

Nonautonomous copies of DNA transposons are very abundant and often outnumber the canonical autonomous copies. We have found that several Drosophila species possess degenerated short sequences sharing similarity with the 5′ and 3′ regions of BuT2, including the TIRs, and might be considered MITEs although some of their characteristics were not observed. MITEs, in general, share typical structural features: 1) short elements with no coding capacity, 2) high copy number, 3) TIRs, 4) location in or near genes, and 5) AT-rich mainly in the inner region (Feschotte and Pritham 2007). This term do not represent a common origin or a taxonomic level in TE classification, although it is very useful.

The first MITE families described in Drosophila were Vege and Mar, both of which were discovered in D. willistoni (Holyoake and Kidwell 2003; Deprá et al. 2012). From there, some other TE families were described to have associated MITEs: hobo from hAT superfamily (Ortiz and Loreto 2008) Bari from Tc1-Mariner superfamily (Dias and Carareto 2011) and BuT5 from P superfamily (Rius et al. 2013). Here we show BuT2 also has associated MITE sequences. BuT2 MITEs, as suggested for other MITE elements (Jiang et al. 2003, 2004; Zhang et al. 2004; Ortiz and Loreto 2008; Deprá et al. 2012), seem to originate by internal deletion of the autonomous element, and during the host species evolution, these MITEs may have originated independently in ancestor and present species. We were unable to analyze the number of copies or conservation of TIRs and TSDs in species other than D. willistoni; thus, we do not know whether the BuT2 MITEs spread successfully throughout other genomes.

The number of MITE copies found in D. willistoni (24 copies) is not as high as that of most of the plants and mosquito MITE families, but there are several families exhibiting more modest copy numbers (Jiang et al. 2003; Quesneville et al. 2006; Grzebelus et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2009; Xu et al. 2010). The D. willistoni BuT2 MITEs present conserved TIRs and TSDs and are grouped together within the same clade of the phylogenetic tree (fig. 3A), suggesting recent mobilization and amplification. The mechanisms of MITE amplification remain poorly understood; but for BuT2 MITES apparently, it could not be explained by duplications. In general, TSD sequences of a copy are identical, but different from those from the other copies, indicating the copies are amplified by a transposition rather than a duplication mechanism, also implicating the presence of an active transposase. Because of the conserved elements ends, that are required for transposition, the most likely hypothesis at this moment is that these MITES are mobilized by the transposase encoded by an active BuT2 copy. Another less likely hypothesis is that BuT2 MITEs can be mobilized by other hAT active element. Cross-mobilization is highly associated with the amplification of MITE families (Jiang et al. 2003; Torres et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2009). Within the hAT superfamily, cross-mobilization has been reported for the hobo element, which is able to mobilize the hermes transposons (Sundararajan et al. 1999). However, both elements belong to the same hAT family, the Ac (see fig. 2) that probably helps on this process.

BuT2 Is Involved in Multiple Events of HT

To reconstruct the BuT2 evolutionary history in the genus Drosophila, we analyzed its interspecific distribution using a combination of bioinformatic and experimental approaches. The results are summarized in figure 5. Three different kinds of evidence are usually considered to indicate HT of TEs: 1) Patchy distribution of a TE across a group of species; 2) Incongruence between host and TE phylogenies; and 3) High sequence similarity between TEs of distantly related species (Silva et al. 2004). We found BuT2 homologous sequences in species from five Drosophila groups with patchy distribution, incongruities between BuT2 and host phylogenies, and high similarity between copies belonging to distantly related species. Therefore, we can conclude that BuT2 has been horizontally transferred between some Drosophila species.

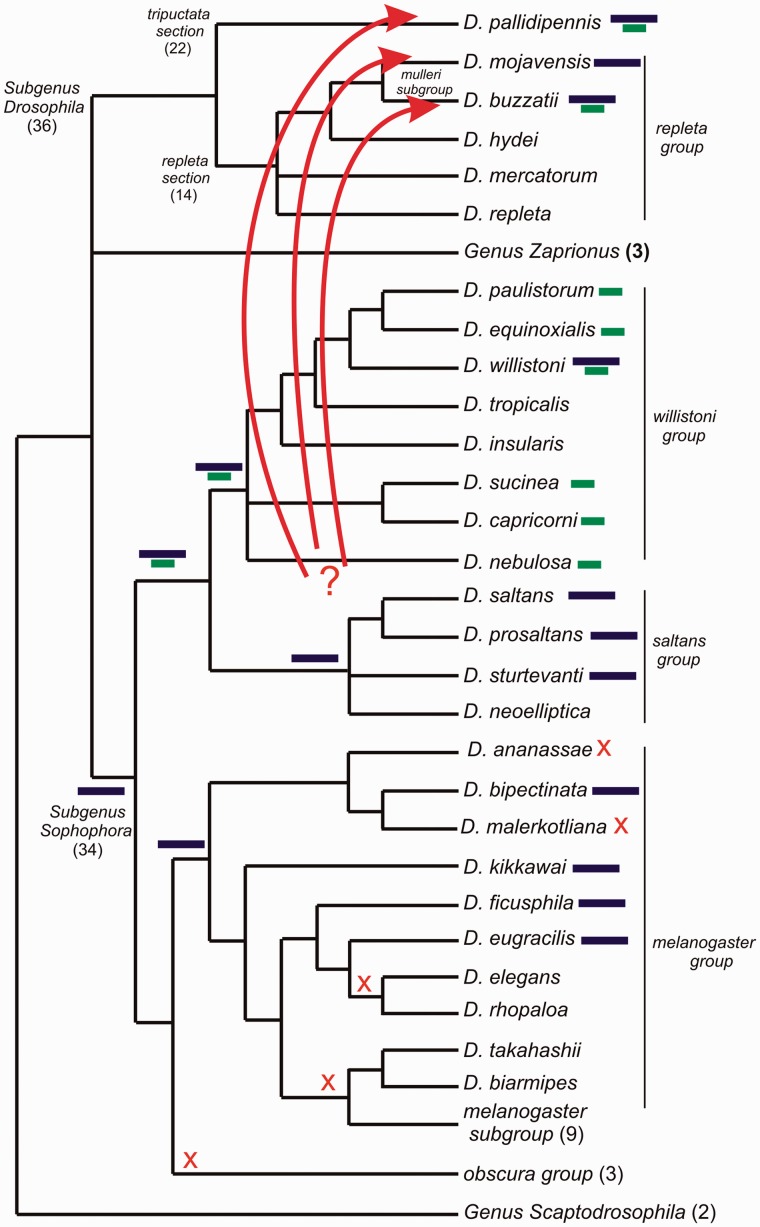

Fig. 5.—

Scheme of phylogenetic relationships of different Drosophilidae species groups employed in this study based on several works (Lewis et al. 2005; Robe et al. 2005; Kopp 2006; Robe, Cordeiro, et al. 2010; Robe, Loreto, et al. 2010; Oliveira et al. 2012). Numerous species that do not have BuT2 were omitted and only the number of species tested is shown. Blue and green bars near species represent the distribution of BuT2 complete copies and MITEs, respectively. The bars at nodes point out the potential presence of those sequences in the main ancestors. Orange crosses represent possible lost events of BuT2, and red arrows indicate probable cases of HT from some species of willistoni or saltans groups to D. pallidipennis, D. mojavensis, and D. buzzatii.

Despite the low support of some branches of the BuT2 phylogenies, we can observe a patchy distribution of BuT2 and some well-supported incongruities when compared with the host species phylogenetic relationships (fig. 3A and B). In the tripunctata section of subgenus Drosophila, BuT2 was found in only one (D. pallidipennis) among 22 species tested (fig. 5). In the repleta section, BuT2 is present in two closely related species, D. buzzatii, where it was originally found, and D. mojavensis. Three other species from the same group (D. repleta, D. mercatorum, and D. hydei) do not contain BuT2 sequences (fig. 5). This distribution is not consistent with VT. In the subgenus Sophophora, we observed a widely distribution of BuT2 in the species from the sister groups saltans and willistoni. This broadly distribution is consistent with the presence of BuT2 element in the ancestor of these two groups (fig. 5). We can also find BuT2 sequences in some species of melanogaster group, however, with a scattered distribution suggesting HT events and/or stochastic loss.

Divergences in TE sequences lower than the divergence between nuclear genes of their respective host species are also indicative of HT (Silva et al. 2004; Wallau et al. 2012). Using as control two genes, Adh and Amd, we have found BuT2 divergence to be significantly lower than expected when comparing D. pallidipennis with D. willistoni, D. buzzatii and D. mojavensis with all willistoni and saltans species, and also D. buzzatii with D. mojavensis.

Taking together all results, we can postulate a possible scenario (fig. 5): a BuT2-like copy was present in the ancestor of subgenus Sophophora, and during speciation process, it was completely lost independently in several species of melanogaster and obscura groups, although few species of melanogaster group still have remnants of this transposon. This BuT2-like element, nonetheless, was apparently maintained active in species of willistoni and saltans group while was vertically transmitted during species evolution. To explain the presence of BuT2 in some species of subgenus Drosophila, we need to propose three HT events: First, from a species of saltans or willistoni subgroups to D. pallidipennis; and more recently, another two cases also from a species of saltans or willistoni subgroups to D. mojavensis and D. buzzatii independently. Alternatively, one of the HT events could have occurred between these two species. A more parsimonious explanation would be an HT event to the ancestor of these two species; however, the lower divergence found for BuT2 is inconsistent with this hypothesis, unless BuT2 is under a higher selective constraint than Adh gene in these species, which is unlikely.

HT events have been proposed as a key step in the TE lifecycle, allowing these sequences to escape extinction before inactivation into the host genome (Le Rouzic and Capy 2006; Venner et al. 2009; Hua-Van et al. 2011). Once in the new genome, the horizontally transferred TE can generate mutations in the same way as those vertically transmitted with detrimental consequences. However, HT can be an important mechanism of genetic innovation, because a newly arrived TE consists in new regulatory and coding regions available to be co-opted by the host genome (Thomas et al. 2010). Also, TEs can facilitate the transfer of additional genetic material and play an important role in the responsive capacity of their hosts to environmental changes (Frost et al. 2005; Casacuberta and González 2013).

The mechanisms for HTs remain obscure, although these transfer events require the occurrence of common premises, such as geographical, temporal, and ecological overlap between donor and recipient species. The species involved in our work are widespread in Neotropics and share some ecological resources (Schmitz et al. 2007); therefore, the conditions for the HT of the BuT2 element are present.

Our work revealed But2 has a multifaceted evolution and life cycle, becoming an important example to investigate the behavior of hAT TEs in the eukaryotes, effects of HT in the receptor genomes, the implications generated by the coexistence of complete copies and MITEs, and the dynamics of MITE amplification in the host genomes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figure S1 and tables S1–S6 are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from CNPq, PRONEX-FAPERGS (10/0028-7), CAPES, PPGBM-UFRGS, PROPESQ-UFRGS, and fellowships from CNPq and CAPES.

Literature Cited

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arensburger P, et al. An active transposable element, Herves, from the African malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Genetics. 2005;169:697–708. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arensburger P, et al. Phylogenetic and functional characterization of the hAT transposon superfamily. Genetics. 2011;188:45–57. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.126813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau TE, Wessler SR. Tourist: a large family of small inverted repeat elements frequently associated with maize genes. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1283–1294. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres M, Puig M, Ruiz A. Molecular characterization of two natural hotspots in the Drosophila buzzatii genome induced by transposon insertions. Genome Res. 2001;11:1353–1364. doi: 10.1101/gr.174001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi BR, Hong TJ, Findley SD, Gelbart WM. Evidence for a common evolutionary origin of inverted repeat transposons in Drosophila and plants: hobo, Activator, and Tam3. Cell. 1991;66:465–471. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casacuberta E, González J. The impact of transposable elements in environmental adaptation. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:1503–1517. doi: 10.1111/mec.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casals F, González J, Ruiz A. Abundance and chromosomal distribution of six Drosophila buzzatii transposons: BuT1, BuT2, BuT3, BuT4, BuT5, and BuT6. Chromosoma. 2006;115:403–412. doi: 10.1007/s00412-006-0071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates CJ, et al. The hermit transposable element of the Australian sheep blowfly, Lucilia cuprina, belongs to the hAT family of transposable elements. Genetica. 1996;97:23–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00132577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprá M, Ludwig A, Valente VLS, Loreto ELS. Mar, a MITE family of hAT transposons in Drosophila. Mob DNA. 2012;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1759-8753-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias ES, Carareto CMA. msechBari, a new MITE-like element in Drosophila sechellia related to the Bari transposon. Genet Res. 2011;93:381–385. doi: 10.1017/S0016672311000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmic MW, Rest JS, Mindell DP, Goldstein RA. rtREV: an amino acid substitution matrix for inference of retrovirus and reverse transcriptase phylogeny. J Mol Evol. 2002;55:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-2304-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston WB, Rim NR, Lim JK. Molecular characterization of hobo-mediated inversions in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;144:647–656. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.2.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers L, Adolphs RH, Kunze R. A highly conserved domain of the maize activator transposase is involved in dimerization. Plant Cell. 2000;12:211–224. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evgen’ev MB, et al. Mobile elements and chromosomal evolution in the virilis group of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11337–11342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210386297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte C, Pritham EJ. DNA transposons and the evolution of eukaryotic genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:331–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan DJ. Eukaryotic transposable elements and genome evolution. Trends Genet. 1989;5:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost LS, Leplae R, Summers AO, Toussaint A. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:722–732. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough J, Karplus K, Hughey R, Chothia C. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of hidden Markov models that represent all proteins of known structure. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:903–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbling G, Strelets V. FlyBase: anatomical data, images and queries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D484–D488. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzebelus D, et al. Population dynamics of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) in Medicago truncatula. Gene. 2009;448:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habu Y, Hisatomi Y, Iida S. Molecular characterization of the mutable flaked allele for flower variegation in the common morning glory. Plant J. 1998;16:371–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler AM. Isolation and analysis of a new hopper hAT transposon from the Bactrocera dorsalis white eye strain. Genetica. 2003;118:17–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1022944120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holyoake AJ, Kidwell MG. Vege and Mar: two novel hAT MITE families from Drosophila willistoni. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:163–167. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua-Van A, Le Rouzic A, Boutin TS, Filée J, Capy P. The struggle for life of the genome’s selfish architects. Biol Direct. 2011;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, et al. An active DNA transposon family in rice. Nature. 2003;421:163–167. doi: 10.1038/nature01214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Feschotte C, Zhang X, Wessler SR. Using rice to understand the origin and amplification of miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs) Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J. hAT-type DNA transposons from Hydra magnipapillata. 2008 Repbase Rep. 8:2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Perspective: transposable elements, parasitic DNA, and genome evolution. Evolution. 2001;55:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohany O, Gentles AJ, Hankus L, Jurka J. Annotation, submission and screening of repetitive elements in Repbase: RepbaseSubmitter and Censor. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp A. Basal relationships in the Drosophila melanogaster species group. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;39:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Rouzic A, Capy P. Reversible introduction of transgenes in natural populations of insects. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:227–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 6: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D229–D232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D302–D305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RL, Beckenbach AT, Mooers AO. The phylogeny of the subgroups within the melanogaster species group: likelihood tests on COI and COII sequences and a Bayesian estimate of phylogeny. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;37:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JK. Intrachromosomal rearrangements mediated by hobo transposons in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:9153–9157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomsadze A, Ter-Hovhannisyan V, Chernoff YO, Borodovsky M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6494–6506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto ELS, Carareto CMA, Capy P. Revisiting horizontal transfer of transposable elements in Drosophila. Heredity. 2008;100:545–554. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, Loreto ELS. Evolutionary pattern of the gtwin retrotransposon in the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. Genetica. 2007;130:161–168. doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-9003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyttle TW, Haymer DS. The role of the transposable element hobo in the origin of endemic inversions in wild populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetica. 1992;86:113–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00133715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison W. Reconstructing character evolution on polytomous cladograms. Cladistics. 1989;5:365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1989.tb00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti S, et al. The M-Coffee web server: a meta-method for computing multiple sequence alignments by combining alternative alignment methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W645–W648. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira DCSG, et al. Monophyly, divergence times, and evolution of host plant use inferred from a revised phylogeny of the Drosophila repleta species group. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;64:533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz MF, Lorenzatto KR, Corrêa BRS, Loreto ELS. hAT transposable elements and their derivatives: an analysis in the 12 Drosophila genomes. Genetica. 2010;138:649–655. doi: 10.1007/s10709-010-9439-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz MF, Loreto ELS. The hobo-related elements in the melanogaster species group. Genet Res. 2008;90:243–252. doi: 10.1017/S0016672308009312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton AC, et al. The Queensland fruit fly, Bactrocera tryoni, contains multiple members of the hAT family of transposable elements. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8:423–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesneville H, Nouaud D, Anxolabéhère D. P elements and MITE relatives in the whole genome sequence of Anopheles gambiae. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevillon E, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–W120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regner LP, Pereira MS, Alonso CE, Abdelhay E, Valente VL. Genomic distribution of P elements in Drosophila willistoni and a search for their relationship with chromosomal inversions. J Hered. 1996;87:191–198. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a022984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rius N, Delprat A, Ruiz A. A divergent P element and its associated MITE, BuT5, generate chromosomal inversions and are widespread within the Drosophila repleta species group. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:1127–1141. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robe LJ, Cordeiro J, Loreto ELS, Valente VLS. Taxonomic boundaries, phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of the Drosophila willistoni subgroup (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Genetica. 2010;138:601–617. doi: 10.1007/s10709-009-9432-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robe LJ, Loreto ELS, Valente VLS. Radiation of the “Drosophila” subgenus (Drosophilidae, Diptera) in the Neotropics. J Zool Syst Evol Res. 2010;48:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Robe LJ, Valente VLS, Budnik M, Loreto ELS. Molecular phylogeny of the subgenus Drosophila (Diptera, Drosophilidae) with an emphasis on Neotropical species and groups: a nuclear versus mitochondrial gene approach. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005;36:623–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi AK, Herédia F, Loreto EL, Valente VLS, Rohde C. Transposable elements P and gypsy in natural populations of Drosophila willistoni. Genet Mol Biol. 2005;28:734–739. [Google Scholar]

- Schaack S, Gilbert C, Feschotte C. Promiscuous DNA: horizontal transfer of transposable elements and why it matters for eukaryotic evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010;25:537–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz HJ, Valente VLS, Hofmann PRP. Taxonomic survey of Drosophilidae (Diptera) from mangrove forests of Santa Catarina Island, Southern Brazil. Neotrop Entomol. 2007;36:53–64. doi: 10.1590/s1519-566x2007000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JC, Loreto EL, Clark JB. Factors that affect the horizontal transfer of transposable elements. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2004;6:57–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinzelle L, Izsvák Z, Ivics Z. Molecular domestication of transposable elements: from detrimental parasites to useful host genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1073–1093. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8376-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan P, Atkinson PW, O’Brochta DA. Transposable element interactions in insects: crossmobilization of hobo and Hermes. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8:359–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.83128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G+C-content biases. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:678–687. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Schaack S, Pritham EJ. Pervasive horizontal transfer of rolling-circle transposons among animals. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:656–664. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres FP, Fonte LFM, Valente VLS, Loreto ELS. Mobilization of a hobo-related sequence in the genome of Drosophila simulans. Genetica. 2006;126:101–110. doi: 10.1007/s10709-005-1436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venner S, Feschotte C, Biémont C. Dynamics of transposable elements: towards a community ecology of the genome. Trends Genet. 2009;25:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallau GL, Ortiz MF, Loreto ELS. Horizontal transposon transfer in eukarya: detection, bias, and perspectives. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4:689–699. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WD, Atkinson PW, O’Brochta DA. The Hermes transposable element from the house fly, Musca domestica, is a short inverted repeat-type element of the hobo, Ac, and Tam3 (hAT) element family. Genet Res. 1994;64:87–97. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300032699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T, et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:973–982. doi: 10.1038/nrg2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, et al. Identification of NbME MITE families: potential molecular markers in the microsporidia Nosema bombycis. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;103:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Nagel DH, Feschotte C, Hancock CN, Wessler SR. Tuned for transposition: molecular determinants underlying the hyperactivity of a Stowaway MITE. Science. 2009;325:1391–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1175688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, et al. Evaluation of five ab initio gene prediction programs for the discovery of maize genes. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57:445–460. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-0271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H-H, et al. A novel hAT element in Bombyx mori and Rhodnius prolixus: its relationship with miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs) and horizontal transfer. Insect Mol Biol. 2013;22:584–596. doi: 10.1111/imb.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Jiang N, Feschotte C, Wessler SR. PIF- and Pong-like transposable elements: distribution, evolution and relationship with Tourist-like miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements. Genetics. 2004;166:971–986. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.2.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.