Abstract

We developed a generalized technique to characterize polymer–nanopore interactions via single channel ionic current measurements. Physical interactions between analytes, such as DNA, proteins, or synthetic polymers, and a nanopore cause multiple discrete states in the current. We modeled the transitions of the current to individual states with an equivalent electrical circuit, which allowed us to describe the system response. This enabled the estimation of short-lived states that are presently not characterized by existing analysis techniques. Our approach considerably improves the range and resolution of single-molecule characterization with nanopores. For example, we characterized the residence times of synthetic polymers that are three times shorter than those estimated with existing algorithms. Because the molecule’s residence time follows an exponential distribution, we recover nearly 20-fold more events per unit time that can be used for analysis. Furthermore, the measurement range was extended from 11 monomers to as few as 8. Finally, we applied this technique to recover a known sequence of single-stranded DNA from previously published ion channel recordings, identifying discrete current states with subpicoampere resolution.

Keywords: nanopores, electrical circuit models, DNA sequencing, single-molecule measurements

Membrane-bound protein ionic channels provide the basis for many cellular activities.1−4 As part of the function of many channels, ion flow through them can be gated, or fluctuate akin to a two-state random telegraph signal. Characterizing these gating kinetics provides insight into the molecular basis of channel activity.5 However, because some events are short-lived events, they do not always attain an observable steady state ionic current and therefore can be missed or ignored in analyses. Several methods, including hidden Markov modeling,6−11 kinetic simulations,12−16 and direct fitting of channel events to the response of the measurement electronics,17 were developed to correct for missed events and markedly improve estimation of the open and closed channel intervals. Most of these techniques implicitly assume that the system fluctuates between two states (infinite and one finite resistance values).

Nanometer-scale pores also have demonstrated potential use in biotechnology applications,18−20 including DNA sequencing,18,21−23 single-molecule force spectroscopy,19,24 and single-molecule mass spectrometry.25,26 The latter can be extended to deduce the geometry of a nanopore without high resolution crystallographic information.20,27,28 The data modeling and analysis methods described in this work potentially allow for dramatic improvements in the quantification of molecular interactions with the channel in each of these applications.

In contrast to gating in ionic channels, the pore conductance in single-molecule measurement applications generally has N states, where N > 2. Techniques to characterize single-molecule interactions with nanopores include thresholding methods,21,26,29 modeling with equivalent circuits,30−32 and Viterbi decoding to improve DNA sequence analysis,33 but are limited to characterizing events when the channel conductance reaches a steady state. The techniques described here address this limitation, and enable the characterization of systems that attain multiple discrete short-lived states.

Results and Discussion

Equivalent Electrical Model

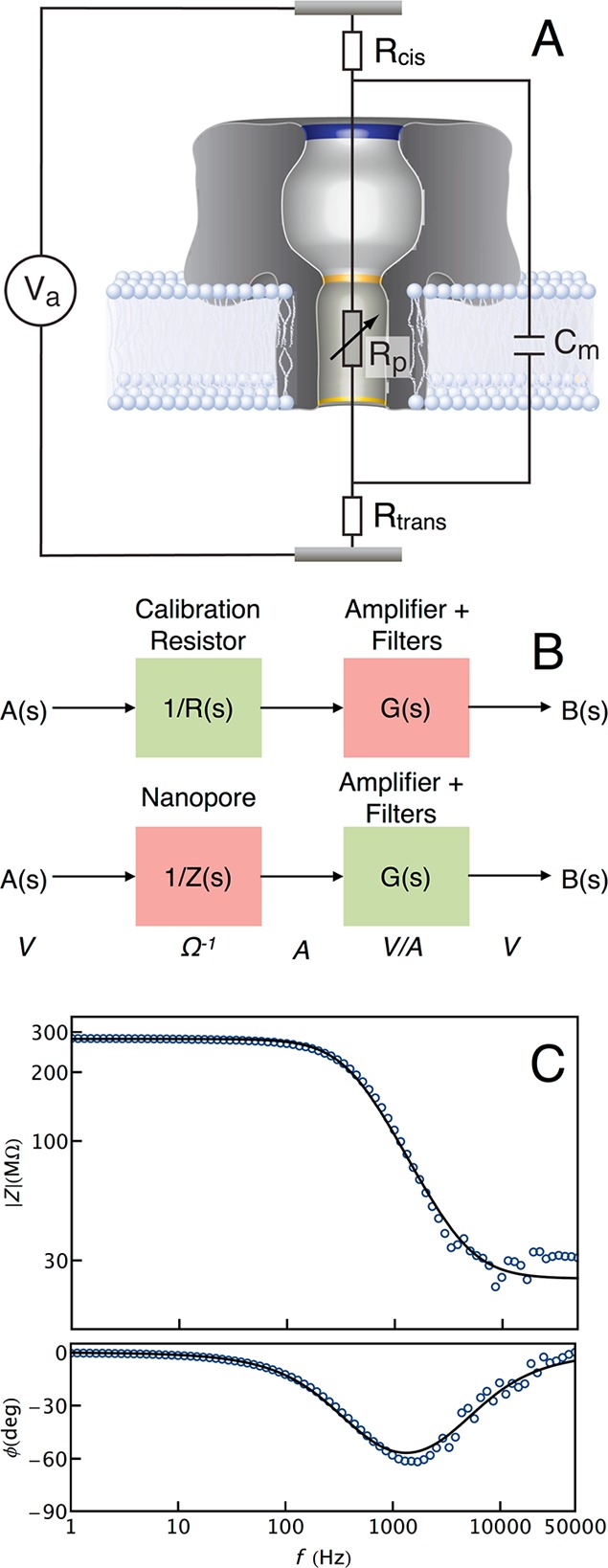

The interactions of single molecules with nanopores are observed by measuring changes to the ionic current that occurs when the pore changes from an unoccupied (i.e., open channel) to an occupied state. The electrical nature of the measurement allows us to model components of the physical system with equivalent electrical elements (Figure 1A), and describe system behavior collectively with the circuit response. The resistance from the electrolyte solution between the two electrodes, together with the access resistance near the entrance of the channel due to electrical field constriction,34−36 is modeled by resistors Rcis and Rtrans, on each side of the nanopore. The nanopore itself is modeled as a resistor, Rp, in series with Rcis and Rtrans. Finally, the lipid bilayer is assumed to be a capacitive circuit element, Cm, in parallel with the nanopore resistor.

Figure 1.

(A) Equivalent circuit model of the nanopore system. The nanopore and membrane are modeled as a resistor (Rp) and capacitor (Cm) in parallel, together with the total solution and access resistances on either side of the membrane (Rcis and Rtrans). (B) The nanopore impedance is measured after removing artifacts from the measurement apparatus. First, the transfer function of the measurement apparatus is determined from the response (B(s)) of a 300 MΩ calibration resistor to a swept sinusoidal voltage (A(s)) stimulus (top). Assuming the resistor frequency response is flat, G(s) = (B(s)/A(s)) R(s), where G(s) and R(s) are the transfer functions of the measurement apparatus and the calibration resistor respectively. The corrected nanopore impedance was then determined in an identical manner (bottom) to yield Z(s) = G(s)/(B(s)/A(s)). (C) The equivalent circuit model was validated by measuring the impedance of the nanopore–membrane complex as a function of frequency (blue markers). A least-squares fit (black) of eq 1 to the measured data yielded estimates of Rp = 255 MΩ, Rcis = Rtrans = 14 MΩ, and Cm = 1.6 pF.

Electrical circuits described above are typically analyzed using external time-varying signal sources. In contrast, for the nanopore sensor system (Figure 1A), the applied potential is fixed, and the net change in the current arises internally from the change in the nanopore resistance, Rp, from single molecules that partition into the pore. We first determine the overall circuit impedance for the case where the channel resistance is fixed, to verify the validity of the equivalent circuit model, and later relax that condition.

For a predetermined pore resistance, the channel ionic current can be obtained by applying Ohm’s law to the impedance (Z) of the circuit in Figure 1A, given in Laplace space by

| 1 |

To verify eq 1, we measured the impedance of a single Staphylococcus aureus α-hemolysin (αHL) nanopore in a lipid bilayer in a glass micro capillary,37 with amplifier bandwidth (B) of 100 kHz and frequencies f < 50 kHz (see Methods for the experimental protocol). The nanopore frequency response implicitly includes the transfer function of the measurement apparatus, which must be removed as shown in Figure 1B (and described in the Methods section). The corrected open channel impedance (magnitude and phase) of the nanopore as a function of frequency is shown in Figure 1C (blue markers). Fitting eq 1 to the measured nanopore impedance yields excellent agreement (Figure 1C, black), resulting in model parameters Rp = 255 MΩ, Rcis = Rtrans = 14 MΩ, and Cm = 1.6 pF.

To further validate this model, we also measured the impedance of the αHL channel incorporated in a large (≈ 50 μm diameter) solvent-free membrane (see Methods). A least-squares fit of eq 1 to that measured nanopore impedance yields Rp = 300 MΩ, Rcis and Rtrans = 1.1 MΩ and Cm = 105 pF (not shown). As expected, model parameters for this latter case differ considerably from the micro capillary-based measurements. The larger membrane area results in a greater capacitance, but Rcis and Rtrans are smaller due to the less-confined geometry of the test cell, compared with the glass micro capillary system. Note that the current measurement technique reported in this work does not allow us to separate asymmetric contributions of the access resistance from the cis (Rcis) and trans (Rtrans) sides of the channel. Therefore, Rcis + Rtrans is the combined access and solution resistances of the system.

The fluctuations of a molecule’s internal degrees of freedom when it interacts with a nanopore are too fast to resolve with existing instrumentation. However, nanopore-molecule interactions result in a discrete changes in the measured conductance, for example, from individual DNA bases translocating across the channel. This allows us to model single-molecule events, assuming a constant applied potential Va, using a series of N instantaneous step changes in the ionic current, each representing a transition from one state to another. In Laplace space, each transition is modeled with a Heaviside step function, Rp(s) = ΔRp/s, where ΔRp is the instantaneous change in pore resistance, per unit time. We can obtain an expression for the nanopore current response of a single transition by substituting eq 1 into I(s) = Va/Z(s) and simplifying,

| 2 |

where α = (1/ΔRp + Cm)Va and τ = (Rcis + Rtrans)(1/ΔRp + Cm). The inverse Laplace transform of eq 2 yields an exponentially decaying time-domain current response,

| 3 |

where i0 is the open channel current offset. eqs 2 and 3 suggest that the experimentally observed RC time constant (τ) is characteristic of the molecule interacting with the pore and related to the molecule’s physical properties (e.g., volume, charge, etc.).26,38

Single-Molecule Analysis

Equation 3 provides the basis for practical single-molecule analysis using the model described above. In this model, the fit parameters, such as the RC time constant (τ) and step height (α), are defined by the values of the underlying electrical components. While knowing the system response (see Figure 1) allows us to extract the values of these underlying electrical components to yield physical insight into the system, a priori knowledge of these parameters is not necessary to analyze single-molecule ionic current time-series. Instead, we describe the molecule interactions (e.g., entry into or exit from the channel) with the pore as discrete changes in the channel conductance. For N-discrete conductance states, eq 3 was generalized by summing individual contributions. In this case, the ionic current is

|

4 |

where H is the Heaviside step function with delay μj and step height aj of the jth state. Parameters for complex events with N discrete steps are estimated by fitting eq 4 to the data. A detailed protocol to analyze measured ionic current time-series is described in the Methods section.

Poly(ethylene glycol) Measurements

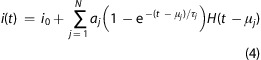

We applied the technique described above to analyze a mixture of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) molecules (see Methods for experimental protocol) with mean molecular weights (Mw) of 400 g/mol (pPEG400; 40 μM), 600 g/mol (pPEG600; 20 μM) and highly purified PEG11 (502 g/mol, polymer index n = 11; 2 μM), in 4 M KCl at pH 7.2. The molecules were measured and characterized individually with a single αHL nanopore.25,26 Data were collected with amplifier bandwidths of 10 and 100 kHz, and sampling frequency, Fs = 500 kHz. To minimize the fitting error, we excluded exceedingly short-lived events (with residence times of a single PEG molecules in the pore, δμ < 16 μs or 8 sample points). Figure 2 shows the current time-series for four representative events, when Va = −40 mV. In the absence of PEG, the mean open channel current was ⟨i0⟩ = −144 ± 2 pA. Individual PEG blockade events were first identified and separated (see Methods for data analysis details). A least-squares fit of eq 4 (with N = 2) to the data corresponding to individual events (Figure 2) yields the amplitude of the ionic current step change (a), RC constant (τ), and residence time (δμ).

Figure 2.

Ionic current time-series (red) caused by different single PEG molecules interacting with an α-hemolysin nanopore. In each case, eq 4, with N = 2, was fit (black) to the data to recover the ideal event pulse (gray, dashed). (A) A long event where the ionic current reaches a steady state. (B–D) For short events, where the ionic current does not reach a steady state with PEG inside the pore, the model returns the true shape (height and width) of the pulse.

Equation 4 implies that the ionic current approaches 99.3% of a (steady-state value) when δμ =5τ. In addition to quantifying long events (δμ > 5τ; Figure 2A), this technique allows us to characterize short-lived events (δμ < 5τ) by extrapolating the exponentially decaying current to its steady-state convergence value (Figure 2B–D). Therefore, the strength of this method lies in its ability to analyze short-lived events that are missed by existing analysis tools.26,29,39

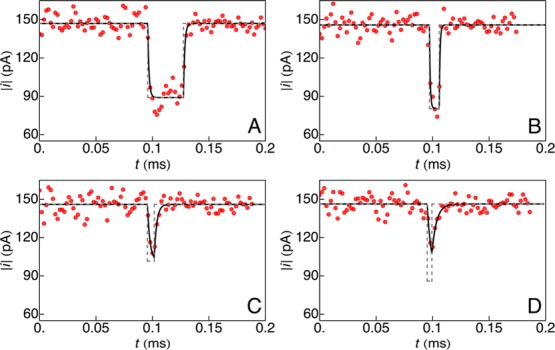

The ability to characterize short events considerably improves the size-based separation of single molecules.25,26,38Figure 3A shows a histogram of blockade depths (⟨i⟩/⟨i0⟩), for the measured PEG sample. Each peak corresponds to a particular size polymer (the height is proportional to that polymer’s concentration) and two peaks differ by one ethylene glycol monomer. The same data were analyzed independently with the new technique and a commonly used current thresholding algorithm.21,26,29 For the higher bandwidth (B = 100 kHz, Fs = 500 kHz) data, the thresholding algorithm recovered ≈12 000 events (Figure 3A, gray markers), corresponding to molecules ranging in size from PEG11 to PEG17. In contrast, the new method recovered ≈217 000 events (18-fold more than the previous method, Figure 3A, orange markers), resulting in molecules sized from PEG8 to PEG19 (black curve). With the use of a more common filter (B = 10 kHz and Fs = 500 kHz), the new technique detected 8 unique species ranging in size from PEG9 to PEG16 (Figure 3B, orange markers), while the thresholding algorithm failed to resolve any PEG species in this small molecule size regime (gray markers).

Figure 3.

(A) Histogram of PEG-induced ionic current blockade depths (⟨i⟩/⟨i0⟩) using thresholding (gray) and the new technique (orange), when B = 100 kHz. The new technique recovered ≈18-fold more events and increased the small molecule measurement limit from PEG with 11 monomers to 8 monomers. The location and height of individual peaks were determined by fitting a Gaussian mixture model to the blockade depth histogram (black). (B) With B = 10 kHz, the new algorithm discriminated 8 distinct PEG sizes (from PEG9 to PEG16, orange markers) from a distribution of ⟨i⟩/⟨i0⟩. In contrast, the thresholding technique failed to detect any peaks (gray markers). (C) Residence times (δμ) followed single exponential distributions, with mean values for PEG10, 10.5 ± 0.6 μs (blue); PEG12, 18 ± 1 μs (orange); and PEG14, 29 ± 1 μs (green). (D) A previously developed analytical theory26,38 that models the physics of PEG–nanopore interactions was fit to the measured data. Least-squares fits of expressions for the mean blockade depth (⟨i⟩/⟨i0⟩, circles) and residence time (δμ, squares) as a function of polymer size were found to be in good agreement over the entire range of the measurement.

A maximum likelihood algorithm was used to assign ionic current blockade events to each species, shown in the mass spectrogram, in Figure 3A.26 This allowed the construction of distributions of molecular residence times, δμ (Figure 3C), shown for PEG10 (blue), PEG12 (orange), and PEG14 (green). Each distribution follows a single exponential function, which suggests both a simple interaction between the polymer and pore, and is consistent with previous results.25,26 We estimated the mean residence time of the molecules in the nanopore from a least-squares fit of a single exponential function to the distribution of δμ for each molecule to yield 10.5 ± 0.6, 18 ± 1, and 29 ± 1 μs for PEG10, PEG12, and PEG14, respectively. The mean residence time decreased with PEG size, as demonstrated in earlier work.25,26,38

Poly(ethylene glycol) Measurements: Physical Validation

We validated the separation of PEG molecules with an αHL nanopore using a previously developed analytical theory that was refined by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.26,38 The analytical theory assumes that PEG decreases the pore conductance by volume exclusion and the formation of reversible PEG–cation complexes.26,38 Therefore, in addition to geometrical parameters, expressions for ⟨i⟩/⟨i0⟩ and δμ include the free energy change from PEG binding a single cation (ΔGpore), the free energy change per monomer associated with confining PEG to the nanopore (ΔGc) and the average number of PEG monomers that are bound to a single cation (rm+).38

Figure 3D shows the least-squares fit of the previously developed analytical theory to the mean blockade depth (black circles) and residence times (black squares), determined using the nanopore circuit model, as a function of polymer index (n). From the data ⟨i⟩/⟨i0⟩ scales inversely with n, consistent with the fact that larger polymers, by virtue of their increased volume and increased coordination of cations, block the channel current more deeply. On the other hand, the mean residence time scales with the polymer size. The analytical theory shows excellent agreement with both quantities even for molecules with as few as 8 monomers. Critical parameters were found to be consistent with previously reported results38 (e.g., rm+ = 0.1, ΔGc = 0.1 kBT and ΔGpore = −4.75 kBT at room temperature).

Interestingly, the value of ΔGc indicates that the smallest measured polymers (n < 10) have confinement energies lower than the thermal energy. With such a low entropic barrier, the capture probability for small molecules will likely have a different rate-limiting step, compared with larger molecules, and consequently a different mechanism responsible for the rate at which these molecules partition into the channel. Our ability to measure the smallest polymers interacting with the nanopore could have interesting implications in quantifying the capture rate and residence times of small molecules. Combining analytical theory with the analysis tools developed herein will permit the quantification of interactions between small molecules and the nanopore.

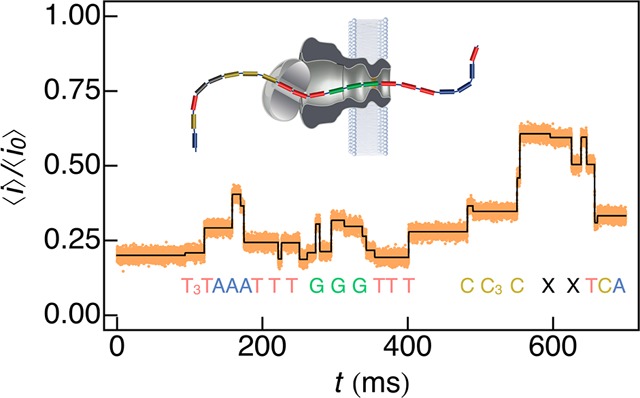

Complex Events: Single-Stranded DNA

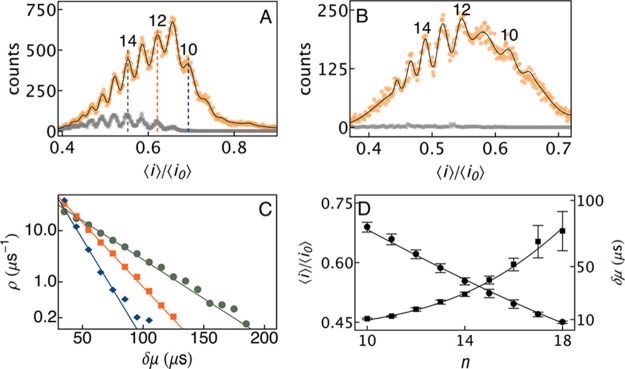

The method described above is directly applicable to arbitrarily complex events with N discrete states. To illustrate this capability we analyzed ionic current time-series from a proposed nanopore-based method for DNA strand sequencing. The Mycobacterium smegmatis porin A (MspA) was used to determine the ionic conductance levels that correspond to a known DNA sequence.22 The data in Figure 4 was reconstructed from work by Gundlach and colleagues22 assuming the root-mean-square (RMS) noise in the ionic current was 1.2 pA, B = 10 kHz, and Fs = 50 kHz. A ionic current thresholding algorithm21,26,29 was first used to generate initial guesses for the fit parameters in eq 4 as described in the Methods section. Fitting the model to the published time series data, we directly identified 26 unique events (Figure 4, black), corresponding to individual bases of the DNA strand. Significantly, we are able to identify step changes in the current as small as 0.9 ± 0.04 pA, which result from systematic fluctuations in measuring sequential thymine bases at the start of the sequence.

Figure 4.

The new analysis method can directly estimate ionic current levels of nanopore-based DNA sequencing data. The ionic current trace was reconstructed from parameters published by Gundlach and colleagues22 that used the MspA nanopore to measure a known DNA sequence. By fitting eq 4 to the data, 26 distinct events were correctly identified to correspond with the sequence of the DNA. The smallest step change in the ionic current from the fit was 0.9 ± 0.04 pA.

Effects of Noise, Bandwidth, and Sampling Rate

The techniques described in this paper, for characterizing previously missed nanopore events, will, in some cases, be limited by existing instrumentation. For example, despite restricting the analysis to events with δμ >16 μs, the technique enabled the determination of the mean residence time of PEG8 (6.1 ± 0.9 μs), because the distribution of δμ follows a single exponential form. Such characterization, however, is much more difficult with even smaller molecules, which exhibit a lesser signal-to-noise ratio.

Increasing the sampling rate would improve the fit of eq 4 to the data, but this strategy is technologically limited by the resolution of fixed-precision analog-to-digital converters. Building on early work,40,41 recent designs of amplifiers have drastically increased the available bandwidth when monitoring ionic current.42,43 While increasing the amplifier bandwidth improves signal fidelity, it also increases noise, especially from statistical counting errors in the ionic current. These considerations suggest a lower limit when measuring PEG with the αHL nanopore, but more generally impose limits on characterizing molecules using ionic current measurements in nanopores. Within these constraints, however, optimization is possible to extend the range of ionic current measurements. A detailed analysis of the errors and any potential optimization will be explored in future work.

Finally, it is important to note that this technique is not limited to ionic current measurements of single molecules. In some cases, the measurement can be considerably improved by employing alternate detection schemes that record the tunneling current across a molecule,44,45 or the drain current in a transistor.46 This electronic current can be modeled using the system response in a manner similar to that described in this work. This in turn has the potential to improve the resolution and detection limits of those electronic measurement techniques.

Conclusions

We developed a technique to analyze transient events in single nanopore ionic current recordings, which fluctuate between N discrete states. A single nanopore system is modeled using equivalent circuit components based on the system physics and molecule–pore interactions. This representation, and its accompanying closed-form analytical expressions, allow the use of circuit response theory to considerably extend the range of nanopore measurements. For example, an intrinsic change in the system impedance from a molecule entering the channel was shown to be related to physical quantities such as the volume or charge of the molecule.26,38 Because this model predicts the response of the nanopore to a molecule interacting with it, we are able to characterize short-lived events that would otherwise be ignored. Applying this technique to the measurement of individual PEG molecules with an αHL nanopore resulted in the detection of nearly 20-fold more events per unit time than existing methods, and allowed the characterization of PEGs with as few as 8 monomers (370 g/mol; approximately the size of sucrose). This technique was also applied to correctly identify individual bases in single-stranded DNA. Moreover, the technique allowed the measurement of systematic fluctuations in the ionic current as small as 0.9 ± 0.04 pA. As demonstrated here, the significantly improved sensitivity and resolution of this analysis technique has direct implications for DNA and protein sequencing,18,19,21,22 where discarded events negatively impact the accuracy and reliability of the measurement.

Methods

Capillary Nanopore Measurements

Single nanopore measurements were performed using quartz capillaries with an ≈1 μm diameter aperture at one end.37 Solvent-free lipid bilayers were formed across the aperture using 10 mg/mL 1,2 diphytanolyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DPhyPC; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) in n-decane. [Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose.] The capillary was filled with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG; Fluka, Switzerland): 20 μM of PEG600 (mean molecular weight 600 g/mol), 40 μM of PEG400 (mean molecular weight 400 g/mol), and a calibration standard of 2 μM highly purified PEG11, Mw = 502 g/mol (Polypure, Norway). PEG was dissolved in 4 M KCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), buffered with 10 mM 2-amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol (TRIS; Schwarz/Mann Biotech, Cleveland, OH), and titrated to pH 7.2 using 3 M citric acid. After ≈10 min, 0.5 μL of 0.5 mg/mL S. aureus α-hemolysin (αHL; List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) was added to the external solution chamber. To decrease the membrane thickness and facilitate channel incorporation, a static pressure between 80 and 120 mmHg was applied and the transmembrane potential was set to 400 mV. When a single αHL channel was inserted into the membrane, the voltage was decreased to −40 mV and the pressure was reduced to 40 mmHg. PEG data were measured with an amplifier bandwidth of 100 kHz and sampled at 500 kHz (Electronic BioSciences, San Diego, CA).

Nanopore Impedance Measurements

Capillary Measurements

The impedance of a single αHL nanopore system (including the lipid membrane, electrolyte solution, and the αHL nanopore, in the test cell), formed using the protocol described above, was measured as a function of frequency. After the formation of a single stable channel, the response (magnitude and phase of the ionic current) to a constant amplitude sine stimulus with varying frequency (swept sine) was recorded. The measurement was performed using a dynamic signal analyzer (HP 35670A, Palo Alto, CA) from DC to 50 kHz. After correcting for the transfer function of the measurement apparatus, as described below, the impedance of the nanopore system was recovered as a function of frequency (Figure 1C, blue markers).

Large Membrane Measurements

A lipid membrane was formed across an ≈50 μm diameter aperture in a 25 μm thick Teflon partition separating two ≈2.5 mL electrolyte reservoirs (4 M KCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.2) using a folding method.47−49 A volume of 5 μL of 0.5 mg/mL αHL solution was added to one chamber and stirred briefly to uniformly distribute the protein. A swept sine measurement using a Modulab potentiostat equipped with a frequency response analyzer and low current amplifier (Solarton Analytical, Farnborough, U.K.) was then run on a continuous loop to record the insertion of individual nanopores into the membrane. The measurement was carried out over a frequency range of 1 Hz to 100 kHz with a fixed 10 mV RMS amplitude sinusoidal potential. The data for a single channel was then processed (see description below) to remove the effect of the transfer function of the measurement apparatus and yield the channel impedance as a function of frequency.

Amplifier Transfer Function Deconvolution

The measured frequency response of the nanopores implicitly includes the transfer function of the measurement apparatus, e.g., the amplifier, cabling, and other factors. To remove these systematic artifacts, we first used a swept sine stimulus A(s) to measure the response B(s) of a 300 MΩ calibration resistor (Figure 1B, top). Assuming the resistor has a flat frequency response over the frequency range of interest, i.e., DC to 50 kHz, we determined that the transfer function of the apparatus is G(s) = (B(s)/A(s)) R(s), where B(s)/A(s) is the measured transfer function, and G(s) and R(s) are the frequency responses of the measurement apparatus and the calibration resistor, respectively. Once the transfer function of the measurement apparatus is computed numerically, by an element-wise division of the complex frequency response, the corrected nanopore impedance is determined in an identical manner (Figure 1B, bottom) to yield Z(s) = G(s)/(B(s)/A(s)).

Data Analysis

Nanopore data were processed with a custom Python program that implemented the method described herein. A thresholding algorithm first detects the interaction of a single molecule with the nanopore, when the ionic current deviates from the open channel value by 2σ, where σ is the standard deviation.26,29 Once an event is detected, this algorithm monitors discrete changes in the ionic current using a threshold to determine the number of discrete current levels (N), and initial estimates of the step height (aj) and the delay (μj) for each discrete current level (j) in the event, as defined in eq 4. Once the initial guesses are determined for an event, eq 4 is fit (for example with N = 2 for PEG events in Figure 2 and N = 26 for the DNA events in Figure 4) to the time-series to accurately estimate event parameters that correspond to a single molecule interacting with the nanopore. The process is repeated to estimate each interaction of a molecule with the nanopore in the recorded time-series.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant R01HG007415 from the National Human Genome Research Initiative (J.J.K.) and by a NRC/NIST-NIH Research Fellowship (A.B.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Katz B.Nerve, Muscle, and Synapse; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel E.; Schwartz J.; Jessell T.. Principles of Neural Science, 5 ed.; McGraw-Hill Medical: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hille B.Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes, 3rd ed.; Sinauer Associates, Incorporated: Sunderland, MA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nonner W.; Eisenberg B. Electrodiffusion in Ionic Channels of Biological Membranes. J. Mol. Liq. 2000, 87, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F. The Voltage Sensor in Voltage-Dependent Ion Channels. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 555–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner L.; Juang B. H. An Introduction to Hidden Markov Models. IEEE ASSP Mag. 1986, 3, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Qin F.; Auerbach A.; Sachs F. A Direct Optimization Approach to Hidden Markov Modeling for Single Channel Kinetics. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 1915–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F.; Auerbach A.; Sachs F. Hidden Markov Modeling for Single Channel Kinetics with Filtering and Correlated Noise. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 1928–1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R.; Stark J. A.; Fitzgerald W. J.; Hladky S. B. Bayesian Restoration of Ion Channel Records Using Hidden Markov Models. Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 1088–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milescu L. S.; Yildiz A.; Selvin P. R.; Sachs F. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Molecular Motor Kinetics From Staircase Dwell-Time Sequences. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 1156–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley C.; Magleby K. L. Linking Exponential Components to Kinetic States in Markov Models for Single-Channel Gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 2008, 132, 295–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatz A. L.; Magleby K. L. Correcting Single Channel Data for Missed Events. Biophys. J. 1986, 49, 967–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F.; Auerbach A.; Sachs F. Estimating Single-Channel Kinetic Parameters From Idealized Patch-Clamp Data Containing Missed Events. Biophys. J. 1996, 70, 264–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D.; Hawkes A. G. On the Stochastic Properties of Bursts of Single Ion Channel Openings and of Clusters of Bursts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 1982, 300, 1–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby K. L.; Weiss D. S. Estimating Kinetic Parameters for Single Channels with Simulation. A General Method That Resolves the Missed Event Problem and Accounts for Noise. Biophys. J. 1990, 58, 1411–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D.; Hatton C. J.; Hawkes A. G. The Quality of Maximum Likelihood Estimates of Ion Channel Rate Constants. J. Physiol. 2003, 547, 699–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D.; Sigworth F. J.. Fitting and Statistical Analysis of Single-Channel Records. In Single-Channel Recording; Sakmann B., Neher E., Eds.; Springer: New York, 1995; pp 483–587. [Google Scholar]

- Kasianowicz J. J.; Robertson J. W. F.; Chan E. R.; Reiner J. E.; Stanford V. M. Nanoscopic Porous Sensors. Ann. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2008, 1, 737–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner J. E.; Balijepalli A.; Robertson J. W. F.; Campbell J.; Suehle J.; Kasianowicz J. J. Disease Detection and Management via Single Nanopore-Based Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 6432–6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. W. F.; Kasianowicz J. J.; Banerjee S. Analytical Approaches for Studying Transporters, Channels and Porins. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 6227–6249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasianowicz J.; Brandin E.; Branton D.; Deamer D. Characterization of Individual Polynucleotide Molecules Using a Membrane Channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 13770–13773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrao E. A.; Derrington I. M.; Laszlo A. H.; Langford K. W.; Hopper M. K.; Gillgren N.; Pavlenok M.; Niederweis M.; Gundlach J. H. Reading DNA at Single-Nucleotide Resolution with a Mutant MspA Nanopore and Phi29 DNA Polymerase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 349–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Tao C.; Chien M.; Hellner B.; Balijepalli A.; Robertson J. W. F.; Li Z.; Russo J. J.; Reiner J. E.; Kasianowicz J. J.; et al. PEG-Labeled Nucleotides and Nanopore Detection for Single Molecule DNA Sequencing by Synthesis. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y.; Dudko O. K. Biomolecules Under Mechanical Stress: A Simple Mechanism of Complex Behavior. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 065102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. W. F.; Rodrigues C. G.; Stanford V. M.; Rubinson K. A.; Krasilnikov O. V.; Kasianowicz J. J. Single-Molecule Mass Spectrometry in Solution Using a Solitary Nanopore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 8207–8211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner J. E.; Kasianowicz J. J.; Nablo B. J.; Robertson J. W. F. Theory for Polymer Analysis Using Nanopore-Based Single-Molecule Mass Spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 12080–12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzlyak P. G.; Yuldasheva L. N.; Rodrigues C. G.; Carneiro C. M. M.; Krasilnikov O. V.; Bezrukov S. M. Polymeric Nonelectrolytes to Probe Pore Geometry: Application to the Alpha-Toxin Transmembrane Channel. Biophys. J. 1999, 77, 3023–3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. W. F.; Kasianowicz J. J.; Reiner J. E. Changes in Ion Channel Geometry Resolved to Sub-Ångström Precision via Single Molecule Mass Spectrometry. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 454108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedone D.; Firnkes M.; Rant U. Data Analysis of Translocation Events in Nanopore Experiments. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 9689–9694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov V.; Mirsaidov U.; Wang D.; Sorsch T.; Mansfield W.; Miner J.; Klemens F.; Cirelli R.; Yemenicioglu S.; Timp G. Nanopores in Solid-State Membranes Engineered for Single Molecule Detection. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 065502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krems M.; Pershin Y. V.; Di Ventra M. Ionic Memcapacitive Effects in Nanopores. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2674–2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht T. How to Understand and Interpret Current Flow in Nanopore/Electrode Devices. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6714–6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timp W.; Comer J.; Aksimentiev A. DNA Base-Calling From a Nanopore Using a Viterbi Algorithm. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, L37–L39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. E. Access Resistance of a Small Circular Pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 1975, 66, 531–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezrukov S. M.; Vodyanoy I. Probing Alamethicin Channels with Water-Soluble Polymers. Effect on Conductance of Channel States. Biophys. J. 1993, 64, 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezrukov S.; Vodyanoy I.; Brutyan R.; Kasianowicz J. Dynamics and Free Energy of Polymers Partitioning Into a Nanoscale Pore. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 8517–8522. [Google Scholar]

- White R. J.; Ervin E. N.; Yang T.; Chen X.; Daniel S.; Cremer P. S.; White H. S. Single Ion-Channel Recordings Using Glass Nanopore Membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 11766–11775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balijepalli A.; Robertson J. W. F.; Reiner J. E.; Kasianowicz J. J.; Pastor R. W. Theory of Polymer-Nanopore Interactions Refined Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7064–7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J.; Wu H.-C.; Jayasinghe L.; Patel A.; Reid S.; Bayley H. Continuous Base Identification for Single-Molecule Nanopore DNA Sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg R. S.; Gage P. W. Ionic Conductances of the Surface and Transverse Tubular Membranes of Frog Sartorius Fibers. J. Gen. Physiol. 1969, 53, 279–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigworth F. J.Electronic Design of the Patch Clamp. In Single-Channel Recording; Sakmann B., Neher E., Eds.; Springer: New York, 1995; pp 95–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop D. K.; Ervin E. N.; Barrall G. A.; Keehan M. G.; Kawano R.; Krupka M. A.; White H. S.; Hibbs A. H. Monitoring the Escape of DNA From a Nanopore Using an Alternating Current Signal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1878–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein J. K.; Wanunu M.; Merchant C. A.; Drndić M.; Shepard K. L. Integrated Nanopore Sensing Platform with Sub-Microsecond Temporal Resolution. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwolak M.; Di Ventra M. Electronic Signature of DNA Nucleotides via Transverse Transport. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carminati M.; Ferrari G.; Ivanov A. P.; Albrecht T. Design and Characterization of a Current Sensing Platform for Silicon-Based Nanopores with Integrated Tunneling Nanoelectrodes. Analog Integr. Circ. Sig. Process. 2013, 77, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Xie P.; Xiong Q.; Fang Y.; Qing Q.; Lieber C. M. Local Electrical Potential Detection of DNA by Nanowire-Nanopore Sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 7, 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montal M.; Mueller P. Formation of Bimolecular Membranes From Lipid Monolayers and a Study of Their Electrical Properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1972, 69, 3561–3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menestrina G. Ionic Channels Formed by Staphylococcus Aureus Alpha-Toxin: Voltage-Dependent Inhibition by Divalent and Trivalent Cations. J. Membr. Biol. 1986, 90, 177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasianowicz J. J.; Bezrukov S. M. Protonation Dynamics of the Alpha-Toxin Ion Channel From Spectral Analysis of pH-Dependent Current Fluctuations. Biophys. J. 1995, 69, 94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]