Abstract

Pioneering work over the past years has highlighted the remarkable ability of manipulating cell states through exogenous, mostly transcription factor-induced reprogramming. The use of small molecules and reprogramming by transcription factors share a common history starting with the early AZA and MyoD experiments in fibroblast cells. Recent work shows that a combination of small molecules can replace all of the reprogramming factors and many previous studies have demonstrated their use in enhancing efficiencies or replacing individual factors. Here we provide a brief introduction to reprogramming followed by a detailed review of the major classes of small molecules that have been used to date and what future opportunities can be expected from these.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cells, small molecules, reprogramming, chemical biology, epigenetics

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotency

ESCs show great potential for regenerative biology and provide a unique platform for studying basic cell biology. Their capacity for unlimited self-renewal allows long-term maintenance of ESC lines in laboratory culture conditions, making them one of the few non-transformed cell types with this ability. As a result, ESCs have proved a useful model for studying early human embryology and, more generally, decisions of cell fate throughout differentiation and specification [1–3]. Furthermore, the system allows for disease modeling in human cells, which facilitates the study of underlying disease mechanisms in a relevant setting [4–6]. Beyond basic research, the prospective clinical uses for personalized cellular therapy using pluripotent cells cannot be overstated. The first clinical trial assessing the use of ESCs for acute spinal cord injury began in 2009 and another trial investigating their use in age-related macular degeneration began in 2010 with promising results [7]. Although cellular therapy with donor ESCs is indeed exciting, the ultimate goal lies in treating patients with genetically matched stem cells derived from their own somatic tissue.

In the past, several approaches have been used to achieve somatic-cell reprogramming including somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) and cell fusion [8,9]. Clinical translation of both techniques has proven difficult, because SCNT requires scarce donor oocytes and is accompanied by ethical trepidation, and the fused tetraploid cells are unsuitable for use in human patients.

The seminal work of Takahashi and Yamanaka eloquently addressed the shortcomings of these reprogramming approaches by transforming fibroblasts into pluripotent cells via forced expression of four transcription factors: Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) [10,11]. The cells produced with this method, termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), show morphological, transcriptional, epigenetic, and phenotypic similarity to ESCs. Likewise, they can differentiate into all embryonic germ layers and incorporate into a developing mouse embryo to give rise to chimeric adults [8]. Many widely available cell types provide the starting point for mouse and human iPSC reprogramming [12,13]. The original protocol relies on viral transduction of the four factors but subsequent efforts quickly focused on methodologies to avoid the use of integrating viruses. Although variable, the kinetics of the process remains slow (2–4 weeks) and inefficient (0.01–0.1% of cells reprogram) [13]. Moreover, the introduction of the oncogenic proteins Klf4 and c-Myc is best avoided when considering clinical translation [14,15].

Improvements to the Yamanaka protocol address these concerns by utilizing alternative methods of transduction, substituting genetic factors with macromolecules, or treating with small molecules that abrogate the need for certain genetic factors [13]. Non-integrating viral vectors, excisable vectors, and direct transfection of plasmid DNA with OSKM can all reprogram fibroblast cells, but the efficiency and kinetics of these processes remain prohibitively low [5,16–18]. Transduced, modified mRNA can substitute for DNA introduction during reprogramming and its transient stability allows for iPSC generation while avoiding integration and permanent introduction of oncogenes [19]. Recombinant OSKM proteins tagged with a cell-penetrant polyarginine sequence have also been used and eliminate the need for the transfer of genetic material [20]. However, this process is inefficient, requires large amounts of recombinant protein and has not been widely used. In addition to the inefficiencies with these second-generation reprogramming methods, the various techniques remain technically challenging, forcing most laboratories to continue to generate iPSCs through classic viral transduction approaches. However, iPSC generation can be facilitated and improved by supplementation with small-molecule compounds. Modulation by small molecules is more technically tractable than alternative genetic approaches and their activity can be restricted temporally and spatially, ensuring an additional level of safety in clinical applications.

The reprogramming process requires coordinated, correctly timed transitions in gene expression, which are mediated by OSKM [21–25] (Figure 1). To date, a small collection of compounds has already been shown to collaborate with OSKM to facilitate iPSC reprogramming (Table 1), all of which exert their effects through gene-regulatory pathways, in particular through inhibiting chromatin regulators or kinase signaling pathways. Furthermore, the first report of somatic-cell reprogramming using only small-molecule compounds was published earlier this year [26]. Following this rapidly advancing field, we review published compounds, their effect on somatic-cell reprogramming, their mechanism of action, and the pathways they act on. A better understanding of how these molecules interact with each other as well as their interaction with the cellular environment will allow for more efficient reprogramming and eventually small molecule-based control of cell states.

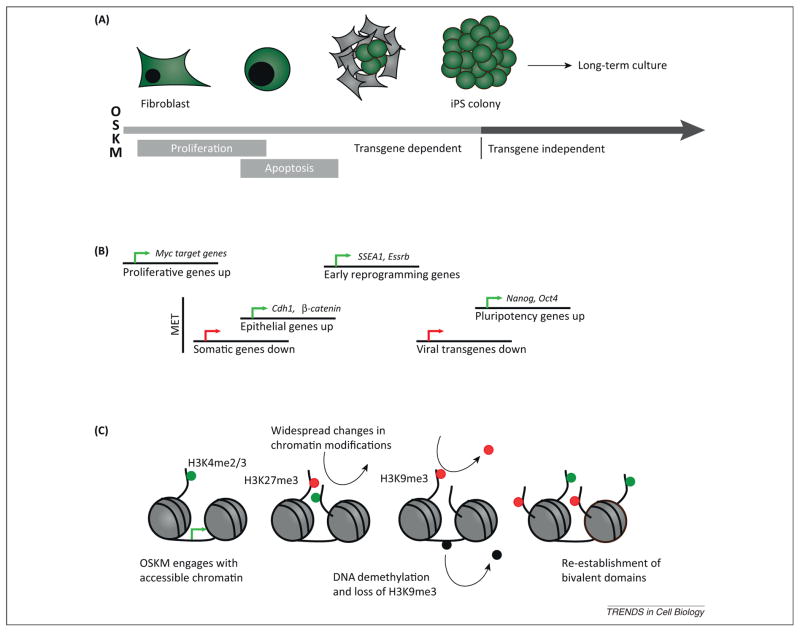

Figure 1.

Dynamics of selected molecular events during reprogramming. The reprogramming of somatic cells occurs in two general phases, the first being transgene dependent wherein removal of exogenous expression of OSK(M) results in the reversion to a differentiated state. During the second phase, removal of exogenous transgene expression no longer prevents the final transition to pluripotency. (A) A set of morphological changes are notable during the transgene-dependent phase, as early reprogramming cells divide rapidly, becoming round and beginning to form clusters. Widespread apoptosis is seen following this expansion, and eventually the cells form compact colonies of fully reprogrammed iPSCs [79]. (B) Many of the early changes in transcription result from a c-Myc driven effect. This is followed by the mesenchymal to epithelial transition seen at an intermediate phase in reprogramming, ultimately leading to the silencing of transgenes and the permanent re-activation of the core pluripotency network. (C) The initial binding locations of the OSKM factors are defined by the chromatin landscape of the somatic cell. Early in reprogramming, widespread changes in histone modifications are seen, followed by a general loss of repressive histone and DNA modifications. In fully reprogrammed cells, bivalent domains are re-established at loci important for development as seen in ESCs. Chromatin remodeling continues during the transgene-independent phase with X-chromosome reactivation and telomere elongation. Abbreviations: ESCs, embryonic stem cells; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; OSKM, Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc.

Table 1.

Compounds shown to collaborate with OSKM to facilitate iPSC reprogramming

| Molecule name | Target | Factors used | Cell type | Effect on reprogramming | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic modifiers | |||||

| EPZ004777 | DOT1L | OS | Fibroblast | Decreases H3K79me2 levels at fibroblast EMT genes | [43] |

| Valproic acid | HDACs | OS | Fibroblast | 20-fold efficiency increase for VPA+OSK | [31,39] |

| TSA, SAHA, NaB | HDACs | OSKM | Fibroblast | Increased efficiency over OSKM | [31,39] |

| Azacytidine | DNMT | OSKM | Fibroblast | Increases efficiency, converts partially reprogrammed cells to iPSCs | [21] |

| RG108 | DNMT | OK | Fibroblast | OK+BIX-01294+RG108 enhances reprogramming over OK alone ~30-fold | [44] |

| BIX | H3K9 protein methyltransferases (PMTs) | OS | Fibroblast | Combination eliminates the need for Oct4, NPCs express endogenous SOX2 | [44] |

| KSM | Neural progenitor cell (NPC) | [67] | |||

| Parnate | LSD1 | OK | Keratinocyte | In combination with CHIR99021, allows keratinocyte reprogramming with OK only | [36] |

| Vitamin C | Histone demethylases | OSK | Fibroblast | Decreases p53 levels during reprogramming, promotes activity of the H3K36 demethylases Jhdm1a and Jhdm1b | [57,58] |

| AMI5 | Arginine methyltransferase | O | Fibroblast | O-only reprogramming in combination with a TGFβ inhibitor | [54] |

| Kinase inhibitors | |||||

| PD0325901 | MEK | Fibroblast | Part of 2i cocktail | [76] | |

| TGFβ inhibitors | ALK4, 5, 7 | OK | Fibroblast | Activates Nanog in partially reprogrammed cells to facilitate transition to iPSCs | [65,66] |

| Kenpaullone | GSK3, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) | OSM | Fibroblast, NPC | Identified in a high-throughput phenotypic screen to replace Klf4 in reprogramming | [70] |

| CHIR99021 | GSK3 | OK | Fibroblast | Part of 2i cocktail, increases efficiency with OSK, allows fibroblast reprogramming with OK only | [76] |

| BIM-0086660 | Aurora kinase | OSKM | Fibroblast | Aurora A inhibition enhances Akt-mediated GSK3β inactivation | [80] |

| Rapamycin | Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) | OSKM | Fibroblast | Reports a correlation between longevity-promoting drugs and reprogramming | [81] |

| Src inhibitors | Src family kinases | OKM | Fibroblast | Compounds induce expression of Nanog | [82] |

| Miscellaneous | |||||

| BayK | L-type calcium channel | – | Fibroblast | Inactive alone, in combination with OS+BIX provides efficiency comparable with OSKM | [44] |

| Forskolin | ATP hydrolase | – | Fibroblast | Part of small molecule-only reprogramming cocktail | [26] |

| DZNep | S-Adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) hydrolase | – | Fibroblast | Part of small molecule-only reprogramming cocktail | [26] |

| RSC133 | Unknown | OSKM | Fibroblast | Some evidence that the molecule targets DNMTs or HDACs | [83] |

| OAC | Unknown | OSKM | Fibroblast | Reported to induce expression of OCT4 in MEFs, only shown to increase efficiency of OSKM | [77] |

Targeting the epigenome in reprogramming

Conrad Waddington described a model of developmental biology where, as cells progress through the stages of development, they irreversibly restrict their developmental potential and become increasingly specialized [27]. Molecular regulation of gene expression mirrors this specialization through the silencing of genes required for alternative cellular lineages and for the pluripotent state as the cell differentiates. These gene-expression programs must be robust and heritable through cell divisions to maintain the integrity of cell state. This is accomplished in part through epigenetic mechanisms, which are defined as heritable, non-genetic changes in the cell. These mechanisms include classically covalent modifications of the DNA and histones, as discussed here, the introduction of histone variants and may also extend to small and large non-coding RNA function [28] (Box 1).

Box 1. Structure and function of epigenomic modifications.

DNA methylation was first observed in mammalian cells in 1948 [84] and initially suggested as a regulatory mechanism in 1975 [85]. In particular, the last two decades have provided critical insights through straight knockout and conditional knockout studies [86,87] as well as, more recently, extensive, genome-wide mapping [21,88]. More than half of all genes contain clusters of CpG dinucleotides, which when methylated result in chromatin compaction and repression of transcriptional activity. These methylation events play important roles in development, genomic imprinting, and X chromosome inactivation and are found to be deregulated in many types of cancer.

In addition to the DNA itself, the histone subunits of nucleosomes are subject to various post-translational modifications (PTMs) that biophysically influence the degree of chromatin compaction and biologically modulate and stabilize transcriptional output by recruiting coactivators and repressors to specific genetic loci [37]. Certain covalent-modification states of chromatin preserve gene-regulatory pathways through cell division, establishing an epigenetic basis for inheritance. Histone modifications are placed by enzymes, termed epigenetic ‘writers’, and are removed by so-called epigenetic ‘erasers’. Many PTMs participate in chromatin-dependent signaling to the gene-regulatory apparatus or influence nucleosome remodeling via assembly of macromolecular complexes nucleated by conserved PTM-specific binding modules (so-called epigenetic ‘readers’) [89].

Several covalent modifications discussed throughout this review are associated with different types of gene regulation. Active promoters are found to be DNA hypomethylated, with high levels of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac accompanying the active RNA polymerase. The first intron of these elongating genes usually contains H3K79me2 [90]. Repressed genes (heterochromatin) can show two main classes of chromatin modification. A combination of H3K9me2, mediated by the histone methyltransferase G9a and DNA methylation is typically associated with permanently silenced constitutive heterochromatin, whereas H3K27me3 marks facultative heterochromatin in stem cells and during cell-type specification. In ESCs, many genes involved in development are marked by both the active H3K4me3 and the repressive H3K27me3 and are termed bivalent genes [91]. These are silenced in the ESC state but poised for activation should the cell differentiate down the appropriate lineage. These bivalent domains are re-established during reprogramming [21], although only at later stages [92].

Genes found to contain DNA methylation at CpG-rich promoters tend to be permanently silenced in differentiated cells and include many pluripotency as well as germ-line genes [29]. Both induced pluripotent stem iPSCs and ESCs are hypomethylated at pluripotency gene promoters, display nucleosome depletion at the transcription start site, and exhibit high levels of transcription. Reactivation of the endogenous pluripotency core circuitry requires loss of the somatic DNA methylation during the reprogramming process [21]. Notably, reprogramming to iPSCs seems predominantly to require loss rather than gain of DNA methylation, because both DNA methyltransferase 3a (Dnmt3a) and Dnmt3b are dispensable for the process [30]. The small number of cells that eventually undergo full reprogramming into iPSCs are able to overcome this epigenetic barrier through yet unknown mechanisms. Unsurprisingly, compounds targeting the epigenetic machinery show activity in enhancing reprogramming rates and efficiency (Table 1) [21,31]. In general, three major classes of compounds have been studied in the context of reprogramming: modulators of DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and histone methylation.

DNA methylation inhibitors

The most widely studied DNA methylation inhibitor, 5-azacytidine (AzaC), was first isolated from Streptoverticillium ladakanus in 1974 and is currently used as a chemo-therapeutic agent [32,33]. AzaC is a chemical derivative of the DNA nucleoside cytidine, the only difference being the presence of a nitrogen atom at position 5 of the cytosine, the same site at which DNA methylation occurs. AzaC is recognized by DNA polymerase and incorporated into replicating DNA. DNMTs acting on incorporated AzaC become covalently attached to the DNA strand due to the nitrogen at position 5, leading to protein degradation and functional depletion of DNMTs that cause a global reduction in levels of DNA methylation [34].

AzaC-induced demethylation was first applied to cellular reprogramming in the classic Weintraub experiments on converting fibroblasts into muscle cells [35]. Several groups have used it in iPSC reprogramming and demonstrated its effect in the context of bulk populations as well as partially reprogrammed cells [21]. Partially reprogrammed fibroblasts that display heterogeneous expression of pluripotency markers were treated with AzaC resulting in a transition to fully reprogrammed iPSCs. Further experiments demonstrated a fourfold enhancement of reprogramming efficiency with AzaC treatment, but only when the cells were treated at a late stage of reprogramming. Treatment early in reprogramming was cytotoxic, although it is unclear whether this is caused by on-target DNMT inhibition or by DNA damage that accompanies AzaC treatment at the dose used in this study (0.5 μM) [21]. Although another study reported that when given throughout the entire reprogramming timeline, AzaC (2 μM) enhances reprogramming efficacy tenfold measured by cell sorting [31]. Greater understanding of this molecule’s pharmacology may provide insight into its best use in somatic reprogramming.

An alternative approach to reversing DNA methylation is the direct inhibition of DNMT enzymatic activity. These compounds tend to have better pharmacological properties and lower toxicity than nucleoside DNA methylation inhibitors. One of these compounds (RG108) has been shown to facilitate reprogramming. Unlike AzaC, RG108 binds directly to the DNMT active site, disrupting propagation of methylation through cell cycle divisions. In a screen for compounds that synergize during reprogramming, combinations that include RG108 were shown to enhance the reprogramming efficiency of cells transduced with just OK [36]. This molecule has not been reported on further but is promising for future research in reprogramming owing to its mechanism of direct DNMT inhibition.

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors

The acetyl group is a post-translational modification placed on lysine residues throughout various histone tails and is generally associated with high levels of transcription [37]. Its impact on transcriptional activation is likely accomplished through two mechanisms: disrupting the electrostatic interaction between the histone and the DNA backbone and acting as a docking site for the recruitment of transcriptional coactivators. Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) place the mark and HDACs remove acetyl groups from the histones [38].

HDAC inhibitors have been widely used in biological studies and in clinical oncology for several indications [38]. A subset of these compounds has also been used in studies for stem-cell reprogramming (Table 1). The most extensively studied HDAC inhibitor in the context of reprogramming is valproic acid (VPA). VPA dramatically increases rates of reprogramming by up to 12% when used in combination with OSKM [31]. Even with removal of the oncogenic c-Myc from reprogramming, rates for OSK+VPA were reported to be higher than OSKM. Notably, VPA could also promote reprogramming, although at lower efficiency, with just OK transduction alone. Finally, the authors also reported two related HDAC inhibitors –SAHA and trichostatin A (TSA) – to be active in reprogramming, although to a lesser extent [39]. Sodium butyrate is another nonspecific HDAC inhibitor in the same class as VPA used in human reprogramming. When used together with OSKM, sodium butyrate showed higher reprogramming rates than VPA treatment in mesenchymal stem cells [40]. One drawback that limits the conclusions and comparability of these studies is the use of various fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) methodologies to quantify the fraction of reprogrammed cells. Some calculate the reprogramming efficiency as a percentage of the final cell population rather than from the initial cell population, so generally cytotoxic compounds like nonspecific HDAC inhibitors can show artificially high reprogramming rates, enriching for a cell population more resistant to HDAC inhibition. When measured by immunohistochemistry instead of FACS, the enhancement conferred by VPA is less than 10% [39]. Nonetheless, HDAC inhibitors remain one of the earliest and most widely used class of compounds known to facilitate iPSC formation.

All of the compounds mentioned here are active against the entire class I and II HDAC family [41]. As a result, these compounds tend to be generally cytotoxic, especially at the high doses used in these experiments. Recent medicinal chemistry efforts in academic laboratories and in industry have provided compounds that can specifically inhibit certain HDAC isoforms [42]. These compounds show lower levels of toxicity than the pan-HDAC inhibitors studied in stem-cell reprogramming to date and may facilitate improved mechanistic understanding as well as allow for further increases in reprogramming efficiency.

Lysine methyltransferase inhibitors

Histone methylation is the most abundant mark on chromatin and serves different functions depending on the site and number of methyl groups placed on the lysine or arginine side chain [37]. A short hairpin RNA (shRNA) screen against histone methylation writers and erasers identified positive and negative regulators of stem-cell reprogramming. Two histone methyltransferases were identified to enhance reprogramming when suppressed by RNAi: SUV39h1 and DOT1L [43]. These two enzymes are responsible for catalyzing the methylation of different lysine residues on the H3 tail (K9 and K79, respectively) and chemical inhibitors of both enzymes are active during stem-cell reprogramming [43,44] (Table 1).

SUV39h1 is a member of an enzyme family responsible for maintaining H3K9me3 in regions of transcriptional repression. H3K9me3 is most often found in permanently silenced regions of terminally differentiated cells including telomeres, centromeres, and other repetitive regions of DNA [37]. In addition to these areas, large regions of H3K9me3 are present in differentiated cells that are replaced with open chromatin in iPSCs and these regions harbor several genes important for the pluripotency network, including Nanog and Sox2 [45,46]. These H3K9me3 regions might act as a barrier in iPSC reprogramming; therefore, disruption with H3K9me3 inhibitors may enhance reprogramming efficiency.

The compound BIX01294 shows inhibitory effects against members of the H3K9 methyltransferase family, with modest specificity for G9a [47]. This compound decreases cellular levels of H3K9me2 and me3 while other histone marks remain unchanged. BIX012494 was identified in a screen for compounds that enable mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) reprogramming transduced with only OK [44]. The efficiency was low for OK+BIX reprogramming, but when combined with AzaC or BayK8644, a calcium-channel agonist, efficiency levels were similar to OSKM reprogramming. The combination of OK and BIX01294 plus RG108 also resulted in reprogramming rates comparable to OSKM controls [44]. Like the nonspecific HDAC inhibitors, BIX01294 exhibits modest cellular toxicity at pharmacologically relevant doses, so the evaluation of more tolerable second-generation H3K9me inhibitors in reprogramming may show further benefits targeting this class of enzymes [48,49].

The other chromatin-associated factor identified in the shRNA screen is the DOT1L lysine methyltransferase [43], which catalyzes the dimethylation of H3K79, a mark associated with active transcription [50]. An important step in embryonic development is the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), where cells lose adhesion properties, and this process is mediated by DOT1L methylation of H3K79 (Box 2). Using both the shRNAs and a recently reported small-molecule inhibitor of DOT1L (EPZ004777) [51], the EMT gene-expression signature was inhibited, favoring MET and presumably enhancing the reprogramming process [43]. When applied during OSKM reprogramming, EPZ004777 increased efficiency fourfold. In line with the idea that the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) is a crucial early step [52], the molecule is effective in the early stages of reprogramming and inactive when used in pretreatment or after 14 days of viral transduction. Additionally EPZ004777 can replace Klf4 and c-Myc, possibly through its effect on the expression of Nanog and Lin28, two other proteins shown to be sufficient for reprogramming when combined with OS [53].

Box 2. The EMT.

The EMT is a phenomenon that occurs during development and is characterized by coordinated changes in intercellular interactions as well as the extracellular matrix [93]. The EMT phenotype includes morphological changes away from close, polarized cellular connections with tight junctions and gap junctions toward a spindle-like, non-polarized cellular morphology and can be seen in gastrulation, during the development of many different organs throughout embryogenesis, and in wound healing. Gene-expression changes accompany this transition with ~4000 genes changing expression levels, with E-cadherin downregulation and Snail upregulation being the hallmarks of EMT, regardless of developmental setting [93]. An EMT can also be seen in cancer progression, with epithelial cancer cells gaining migratory and invasive processes while losing cell-junction properties, allowing metastasis.

One of the earliest observable events during fibroblast reprogramming is a MET where elongated fibroblast cells become rounded and aggregate into small clusters. These events occur early in the reprogramming timeline (see Figure 1 in main text), roughly between days 3 and 5 depending on the system used, and correlate with alkaline phosphatase (AP) positivity and SSEA upregulation. The MET also coincides with the upregulation of a gene set enriched in epithelial junction components, including Cdh1 and β-catenin, and involvement of the TGFβ signaling pathway (see Figure 2 in main text). Different TGFβ ligands have different effects on the reprogramming process, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 inhibit reprogramming [66] whereas BMP7 enhances reprogramming [52] through a miRNA-mediated mechanism.

Both H3K9 and DOT1L inhibitors have been well characterized for specificity and selectivity for the target enzymes due to their planned use in clinical trials, thereby providing a high degree of confidence that their activity in reprogramming is due to engagement of the protein target of interest. Several miscellaneous molecules that affect histone methylation also show some activity in cellular reprogramming, but their activities and possible off-target effects remain poorly defined. AMI-5 is a general inhibitor of arginine methyltransferases and when combined with transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) inhibition allows Oct4-only reprogramming [54]. Parnate inhibits the activity of lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) and was identified in a target screen for combinations that allow reprogramming in the absence of Sox2 when MEFs are supplemented with VPA and CHIR99021 [36]. These molecules undoubtedly exhibit reprogramming enhancement in chemical cocktails, although the promiscuity of both of these molecules clouds their roles in the process. AMI-5 has not been profiled against other protein targets to query additional nonspecific interactions [55] and Parnate is clinically approved as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor [56]. Vitamin C also enhances reprogramming efficiency, possibly through increasing rates of histone demethylation or DNA demethylation, but again the exact mechanism is unclear and requires further investigation [57,58].

The program required for the transition from somatic-cell to iPSC state requires changes at many histone methylation and acetylation sites, as well as changes in arginine methylation, serine phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and probably many currently unknown marks. As new compounds emerge that allow for exquisite manipulation of the epigenome, the roles that individual histone marks play in this process will become clearer and may allow mimicking of the transcriptional program mediated through OSKM with small-molecule treatment. One notable class of inhibitors still to be studied in iPSC formation is the recently reported inhibitors of the EZH2 methyltransferase [59], the enzyme responsible for placing the repressive H3K27me3. Interestingly, H3K27me3 dynamics are very limited in the early phase of reprogramming and loss/gain occurs at the later stages [23]. Notably, depletion of H3K27me3 through Ezh2 inhibition or knock down of other Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) components such as Eed decreased the reprogramming efficiency highlighting its dual role in stabilizing the differentiated and pluripotent state [60]. Nonetheless, the histone demethylase UTX was shown to cooperate with OSK to facilitate reprogramming [61], suggesting the process could possibly be mimicked with a small-molecule EZH2 inhibitor [59], which may allow for better and possibly required temporal control.

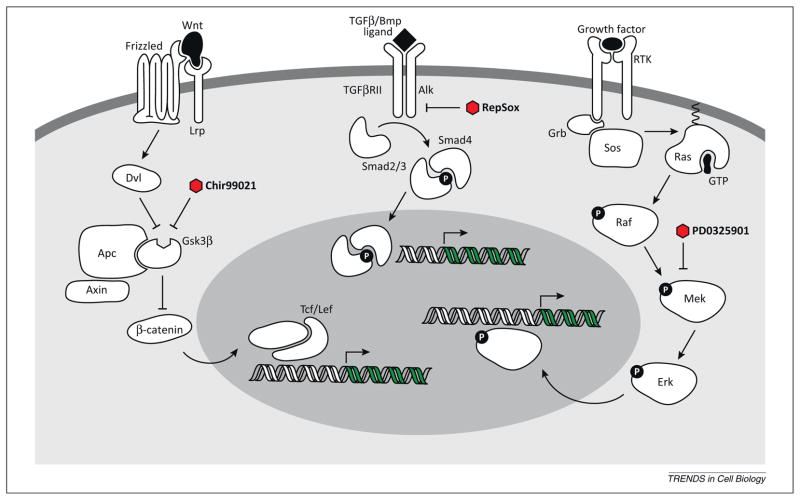

Modulation of cell signaling

In the same way as cancer biology inspired the development of compounds that modulate epigenomic targets, the systematic approach to kinase inhibition emerged from efforts in cancer-drug discovery. Many oncogenic mutations constitutively activate signaling pathways that promote growth and survival while bypassing the negative-feedback loops built into the signaling networks. Toward blocking this aberrant signaling, chemists developed many compounds capable of modulating key signaling pathways in the cell [62]. The cornucopia of compounds designed to target the human kinome provides a wealth of possibilities for manipulating cell state, in both disease and cellular reprogramming. It is now appreciated that pharmacological inhibition of three important kinases – TGFβ receptors, glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) – enhances somatic cell reprogramming (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Simplified schematic of key signaling pathways (Wnt/Gsk3β, TGFβ, and MEK) that have been targeted by small molecule inhibitors to enhance the reprogramming of somatic cells to a pluripotent state. Three small molecules and their targets within the pathways are shown.

TGFβ inhibitors

Proteins in the TGFβ superfamily, including bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), have been shown to play a role in stem-cell self-renewal and fate determination [63]. BMPs are extracellular ligands that bind to serine/threonine kinase receptors, triggering complex formation and receptor phosphorylation that signals through Smad transcription factors and is directly involved in transcriptional regulation (Figure 2). During development, TGFβ ligands participate in signaling to promote the EMT (Box 2), and blocking these pro-EMT signals through OSKM expression or small-molecule inhibition facilitates the MET and thereby presumably reprogramming [64].

Inhibitors of TGFβ signaling that bind the Alk receptor [52,65,66] were originally found to facilitate reprogramming in a high-content cell-based reprogramming screen for compounds capable of replacing Sox2 [65]. Unlike previous studies that reported Sox2 reprogramming in cell types that already express endogenous Sox2 [67], this compound replaces Sox2 in MEFs and prevents the binding interaction between Alk and TGFβ ligands [65,66]. The authors hypothesized that the compound works through the induction of Nanog, an alternative pluripotency factor, in a population of reprogramming intermediates formed by the expression of OKM. However, these compounds may also block the EMT and further study of this signaling axis with specific pharmacological tools might provide more insight on how to best utilize this class of compounds.

GSK3 inhibition

GSK3 is a serine/threonine kinase involved in the regulation of over 40 proteins in the cell [68]. Post-translational modification, subcellular localization, and differential complex formation coordinate its specificity in the cell. It is active in pathways that control cellular structure, growth, motility, and apoptosis. Deregulation of GSK3 is implicated in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease, leading to the characterization of potent and specific inhibitors of the enzyme [69]. One of these compounds (CHIR99021) was identified as an enhancer of reprogramming in a cell-based phenotypic screen [36]. It significantly improves the reprogramming efficiency of OSK transduced MEFs and in combination with Parnate (an LSD1 inhibitor) allows reprogramming in the absence of Sox2 [36]. A second GSK3 inhibitor, kenpaullone, was identified in a separate screen using 500,000 compounds and can replace Klf4 in reprogramming [70]. However, the specificity of kenpaullone is low compared with CHIR99021 and no further study of kenpaullone in reprogramming has been reported.

The GSK3 compounds are hypothesized to exert their effects through the Wnt pathway, an important pathway for stem-cell maintenance and proliferation. ESCs secrete Wnt ligands and autocrine Wnt signaling is required to prevent their differentiation [71]. In canonical Wnt signaling, the absence of Wnt binding to the membrane-associated Frizzled receptor allows a degradation complex comprising Axin and APC to target cytoplasmic β-catenin for proteolysis. GSK is another subunit of this degradation complex and phosphorylates β-catenin, promoting ubiquitinylation and degradation. Inhibition of GSK3 with small molecules stabilizes β-catenin and allows it to translocate into the nucleus where it associates with TCF transcription factors to initiate transcription (Figure 2).

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that Wnt signaling and GSK3 are important for stem-cell self-renewal and proliferation [72,73]. Activation of the pathway with treatment of Wnt3a ligand stabilizes β-catenin and promotes reprogramming in MEFs with OSK transduction [72,73]. This is a functional mimic of GSK3 inhibition, which would also prevent β-catenin degradation and promote a transcriptional program compatible with reprogramming. Wnt signaling in reprogramming is context specific, because early activation of Wnt leads to a reprogramming block whereas late activation of Wnt is beneficial, owing to different transcriptional coactivators being present at these stages [74]. These differences might provide an alternative avenue for small-molecule modulation where compounds acting directly on transcriptional coactivators could play an important role in leveraging stage-specific patterns of gene expression during reprogramming.

Although GSK3 certainly plays a role in Wnt signaling, which has clear links to stem-cell biology, GSK3 has many protein targets and is involved in other signaling pathways including metabolic regulation. Further research is needed to define the mechanism through which CHIR99021 exerts its effects, which could then be exploited more specifically during reprogramming.

MEK inhibition

MEK kinase is a component of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, a highly conserved membrane-to-nucleus signaling module. Extracellular mitogenic or differentiating signals bind to receptor tyrosine kinases, which through mediator proteins activate the Ras GTPase and the downstream MAPK cascade in which successive kinases are activated through phosphorylation. ERK, the final protein in the MAPK cascade, can translocate into the nucleus and phosphorylate transcription factors, regulating their activity. Its activation is implicated in a wide variety of cellular functions as diverse as cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, terminal differentiation, and apoptosis [75].

When added during late stages of reprogramming, the MEK inhibitor PD0325901 when combined with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and GSK inhibition stabilizes true iPSCs while inhibiting the growth of non-pluripotent cells and promoting the conversion of pre-iPSCs into a fully reprogrammed state [76]. Additionally, MEK inhibition prevents differentiation of iPSCs in culture, further enriching for the population of pluripotent cells. PD0325901 is a common supplement in stem-cell culture media for achieving ‘ground-state’ pluripotency and during long-term passaging to prevent spurious differentiation [76].

Concluding remarks

Most small molecules identified to date that provide enhancements of somatic cell reprogramming are able to compensate for three of the four canonical factors, SKM. The identification of molecules that can substitute directly for Oct4 transduction has proved difficult, but recent progress is encouraging [77]. Earlier this year, the first successful reprogramming experiment using only small-molecule compounds was published [26], using a combination of VPA, CHIR99021, 616452 (an ALK inhibitor), tranylcypromine (an LSD1 inhibitor), forskolin (an adenylyl cyclase activator), and late treatment with the global methylation inhibitor DZNep, which leads to broad reduction in histone methylation. The final two compounds were found using phenotypic cellular screening, a promising approach for further optimization of reprogramming conditions. These findings are exciting and understanding the mechanisms underlying the activity of these new molecules is of immediate interest.

Despite the recent progress, a barrier remains to rapid, reliable generation of iPSCs from somatic cells, limiting their expanded use in clinical settings. Further studies into the pathways that underlie reprogramming and the pharmacological modulations that are capable with current chemical biology tools will identify new areas where small molecules might be useful and new targets that provide opportunities for chemical discovery. Future studies should move toward the incorporation of well-validated chemical probes and more sophisticated pharmacological approaches to identify optimal reprogramming conditions. Chemical probes with well-studied specificity profiles and biological properties will be important in uncovering the fundamental pathways that must be altered to allow somatic reprogramming [78]. Other chemical approaches would include the establishment of context-specific dose responses, exposure times, and synergistic effects in a systematic and high-throughput way. Most studies with small molecules in reprogramming adopt these parameters from the cancer literature, a useful but imperfect model. Advances in compound-screening technology in combination with new molecule libraries should also contribute towards progress in defining routine iPSC derivation from easily accessible patient tissue, a technology that will hopefully allow the swift adaptation of iPSCs in translational and clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Meissner and Bradner laboratories for their discussions and critiques of the manuscript. They specifically thank Katharin Shaw for her insight regarding figure design and layout. A.J.F. is supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. A.M. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P01GM099117) and is a Robertson Investigator of The New York Stem Cell Foundation.

References

- 1.Weissman IL. Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell. 2000;100:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison SJ, et al. Regulatory mechanisms in stem cell biology. Cell. 1997;88:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81867-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller G. Embryonic stem cell differentiation: emergence of a new era in biology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1129–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.1303605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimos JT, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somers A, et al. Generation of transgene-free lung disease-specific human induced pluripotent stem cells using a single excisable lentiviral stem cell cassette. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1728–1740. doi: 10.1002/stem.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unternaehrer JJ, Daley GQ. Induced pluripotent stem cells for modelling human diseases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B: Biol Sci. 2011;366:2274–2285. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz SD, et al. Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: a preliminary report. Lancet. 2012;379:713–720. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamanaka S. Induced pluripotent stem cells: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R. Nuclear reprogramming and pluripotency. Nature. 2006;441:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/nature04955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sindhu C, et al. Transcription factor-mediated epigenetic reprogramming. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30922–30931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.319046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stadtfeld M, Hochedlinger K. Induced pluripotency: history, mechanisms, and applications. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2239–2263. doi: 10.1101/gad.1963910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu F, et al. Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) is required for maintenance of breast cancer stem cells and for cell migration and invasion. Oncogene. 2011;30:2161–2172. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woltjen K, et al. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stadtfeld M, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science. 2008;322:945–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1162494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okita K, et al. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science. 2008;322:949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1164270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren L, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikkelsen T, et al. Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature. 2008;454:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nature07056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sridharan R, et al. Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell. 2009;136:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koche R, et al. Reprogramming factor expression initiates widespread targeted chromatin remodeling. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buganim Y, et al. Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell. 2012;150:1209–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polo J, et al. A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell. 2012;151:1617–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou P, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemberger M, et al. Epigenetic dynamics of stem cells and cell lineage commitment: digging Waddington’s canal. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:526–537. doi: 10.1038/nrm2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg AD, et al. Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell. 2007;128:635–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pawlak M, Jaenisch R. De novo DNA methylation by Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b is dispensable for nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells to a pluripotent state. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1035–1040. doi: 10.1101/gad.2039011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huangfu D, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells by defined factors is greatly improved by small-molecule compounds. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:795–797. doi: 10.1038/nbt1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cihák A. Biological effects of 5-azacytidine in eukaryotes. Oncology. 1974;30:405–422. doi: 10.1159/000224981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman LR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the cancer and leukemia group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christman JK. 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine as inhibitors of DNA methylation: mechanistic studies and their implications for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2002;21:5483–5495. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor SM, Jones PA. Multiple new phenotypes induced in 10T1/2 and 3T3 cells treated with 5-azacytidine. Cell. 1979;17:771–779. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li W, et al. Generation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of exogenous Sox2. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2992–3000. doi: 10.1002/stem.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haberland M, et al. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huangfu D, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from primary human fibroblasts with only Oct4 and Sox2. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mali P, et al. Butyrate greatly enhances derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by promoting epigenetic remodeling and the expression of pluripotency-associated genes. Stem Cells. 2010;28:713–720. doi: 10.1002/stem.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradner J, et al. Chemical phylogenetics of histone deacetylases. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itoh Y, et al. Isoform-selective histone deacetylase inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:529–544. doi: 10.2174/138161208783885335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onder T, et al. Chromatin-modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature. 2012;483:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature10953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi Y, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small-molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen J, et al. H3K9 methylation is a barrier during somatic cell reprogramming into iPSCs. Nat Genet. 2012;45:34–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schotta G, et al. Central role of Drosophila SU(VAR)3-9 in histone H3-K9 methylation and heterochromatic gene silencing. EMBO J. 2002;21:1121–1131. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubicek S, et al. Reversal of H3K9me2 by a small-molecule inhibitor for the G9a histone methyltransferase. Mol Cell. 2007;25:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vedadi M, et al. A chemical probe selectively inhibits G9a and GLP methyltransferase activity in cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:566–574. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan Y, et al. A small-molecule probe of the histone methyltransferase G9a induces cellular senescence in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1152–1157. doi: 10.1021/cb300139y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen AT, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of Dot1 and H3K79 methylation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1345–1358. doi: 10.1101/gad.2057811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daigle S, et al. Selective killing of mixed lineage leukemia cells by a potent small-molecule DOT1L inhibitor. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samavarchi-Tehrani P, et al. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan X, et al. Brief report: combined chemical treatment enables Oct4-induced reprogramming from mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Stem Cells. 2011;29:549–553. doi: 10.1002/stem.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng D, et al. Small molecule regulators of protein arginine methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23892–23899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kingston WR. A clinical trial of an antidepressant, tranylcypromine (“Parnate”) Med J Aust. 1962;49:1011–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Esteban M, et al. Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blaschke K, et al. Vitamin C induces Tet-dependent DNA demethylation and a blastocyst-like state in ES cells. Nature. 2013;500:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nature12362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCabe M, et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012;492:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fragola G, et al. Cell reprogramming requires silencing of a core subset of polycomb targets. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mansour A, et al. The H3K27 demethylase Utx regulates somatic and germ cell epigenetic reprogramming. Nature. 2012;488:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature11272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang J, et al. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Varga AC, Wrana JL. The disparate role of BMP in stem cell biology. Oncogene. 2005;24:5713–5721. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li R, et al. A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ichida J, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of TGF-beta signaling replaces Sox2 in reprogramming by inducing Nanog. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maherali N, Hochedlinger K. TGFbeta signal inhibition cooperates in the induction of iPSCs and replaces Sox2 and cMyc. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1718–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim J, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature. 2008;454:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature07061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen P, Goedert M. GSK3 inhibitors: development and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:479–487. doi: 10.1038/nrd1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lyssiotis C, et al. Reprogramming of murine fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells with chemical complementation of Klf4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8912–8917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903860106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.ten Berge D, et al. Embryonic stem cells require Wnt proteins to prevent differentiation to epiblast stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1070–1075. doi: 10.1038/ncb2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marson A, et al. Wnt signaling promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holland JD, et al. Wnt signaling in stem and cancer stem cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ho R, et al. Stage-specific regulation of reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells by Wnt signaling and T cell factor proteins. Cell Rep. 2013;3:2113–2126. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zebisch A, et al. Signaling through RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK: from basics to bedside. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:601–623. doi: 10.2174/092986707780059670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silva J, et al. Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li W, et al. Identification of Oct4-activating compounds that enhance reprogramming efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:20853–20858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219181110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Frye SV. The art of the chemical probe. Nat ChemBiol. 2010;6:159–161. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith ZD, et al. Dynamic single-cell imaging of direct reprogramming reveals an early specifying event. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li Z, Rana T. A kinase inhibitor screen identifies small-molecule enhancers of reprogramming and iPS cell generation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1085. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen T, et al. Rapamycin and other longevity-promoting compounds enhance the generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Aging Cell. 2011;10:908–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Staerk J, et al. Pan-Src family kinase inhibitors Replace Sox2 during the direct reprogramming of somatic cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:5734–5736. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee J, et al. A novel small molecule facilitates the reprogramming of human somatic cells into a pluripotent state and supports the maintenance of an undifferentiated state of human pluripotent stem cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:12509–12513. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hotchkiss RD. The quantitative separation of purines, pyrimidines, and nucleosides by paper chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1948;175:315–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Holliday R, Pugh JE. DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science. 1975;187:226–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li E, et al. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Okano M, et al. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 1999;99:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meissner A, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheung P, et al. Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell. 2000;103:263–271. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huff J, et al. Reciprocal intronic and exonic histone modification regions in humans. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1495–1499. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bernstein B, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meissner A. Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1079–1088. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zavadil J, et al. Genetic programs of epithelial cell plasticity directed by transforming growth factor-beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6686–6691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111614398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]