Abstract

Objectives

The objective of our paper was to ascertain the self-reported competency level of surgeons who had completed a 1-year spine fellowship versus those who had not. Our secondary objective was to determine whether there was any difference between orthopaedic and neurosurgeons.

Methods

A 60 question online questionnaire was provided to AOSpine Europe members for completion online.

Results

289 members provided a response, of which 64 % were orthopaedic surgeons and 31 % neurosurgeons (5 % did not specify). Eighty (28 %) had completed a 1-year fellowship. Theoretical and practical knowledge of the management of spinal deformity was the greatest difference seen upon completing a fellowship. Multiple elective and emergent conditions were demonstrated to have a significant difference upon completion of a fellowship. There was no difference between orthopaedic surgeons and neurosurgeons.

Conclusions

In order to provide an efficient and safe service covering the broad spectrum of spinal pathology, a formal spine fellowship, ideally with a formal curriculum, should be considered.

Keywords: Spine, Fellowship, Training, Complications, Assessment

Introduction

Spinal surgery is a dynamically developing field of medicine. It has been a focus of extensive research that has led to numerous advances in surgical procedures. The increased volume of rapidly accumulating knowledge delineates a trend for spinal surgery becoming an established and discrete discipline distinct from general orthopaedics and neurosurgery. The importance of this discipline has dramatically evolved over the past decades [1]. It has transformed from being the domain of neurosurgeons, as a method of neural element decompression, to becoming a major aspect of neurosurgical and orthopaedic practise (spinal procedures now comprise 14 % of orthopaedic practise and 60 % of neurological practise [2]).

A reduction in training due to the instigation of the European Working Time Directive is a cause of concern amongst the medical profession. It is believed that the quality of training may be compromised, and that despite of modifications to the surgical training curriculum and the introduction of innovative teaching methods into residency programmes, future doctors may be less competent than their present day counterparts [2]. Combined with the rapid advancement of the field, the knowledge base and skills required are becoming unmanageable for an orthopaedic or neurosurgical resident to master.

Subspecialisation is a phenomenon that not only results in better services and patient outcomes due to increased physician expertise, but is also cost-effective [3]. 80 % of graduates enrol in some type of advanced surgical training programme after completion of general surgical training [4]. Spinal fellowships are becoming increasingly popular, with 54 % of neurosurgical residents at the EANS (European Association of Neurosurgical Specialities) training course in 2004 interested in further training in spinal surgery [3] for example.

The efficacy of subspecialty training provides better outcomes—we do not know whether fellowship training is directly responsible for this. Whilst it can be assumed that fellowship training meets this goal in a particular subspecialty, to our knowledge this has not been formally assessed in spinal surgery.

A fellowship allows for an increased exposure to specialised disorders, which is associated with improved surgical outcomes [5, 6]. It is also the time to acquire decision-making skills and familiarise oneself with the most recent surgical techniques and their associated complications. Fellowship programmes are not uniform, each emphasising certain disease processes perhaps at the cost of others. Regardless of the nature of the spinal fellowship, it is expected that upon completion of the programme a fellow is competent in the diagnosis and management of a wide spectrum of spinal disorders and trauma. Arguably, this lack of regulation of the curriculum of spinal training leads to variable competence amongst specialists.

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether fellowship training led to an increase in (self-assessed) competency. The secondary objective was to determine whether there was any difference in theoretical and practical competencies between those respondents who had been trained as neurosurgeons and those who had been trained as othopaedic surgeons.

Materials and methods

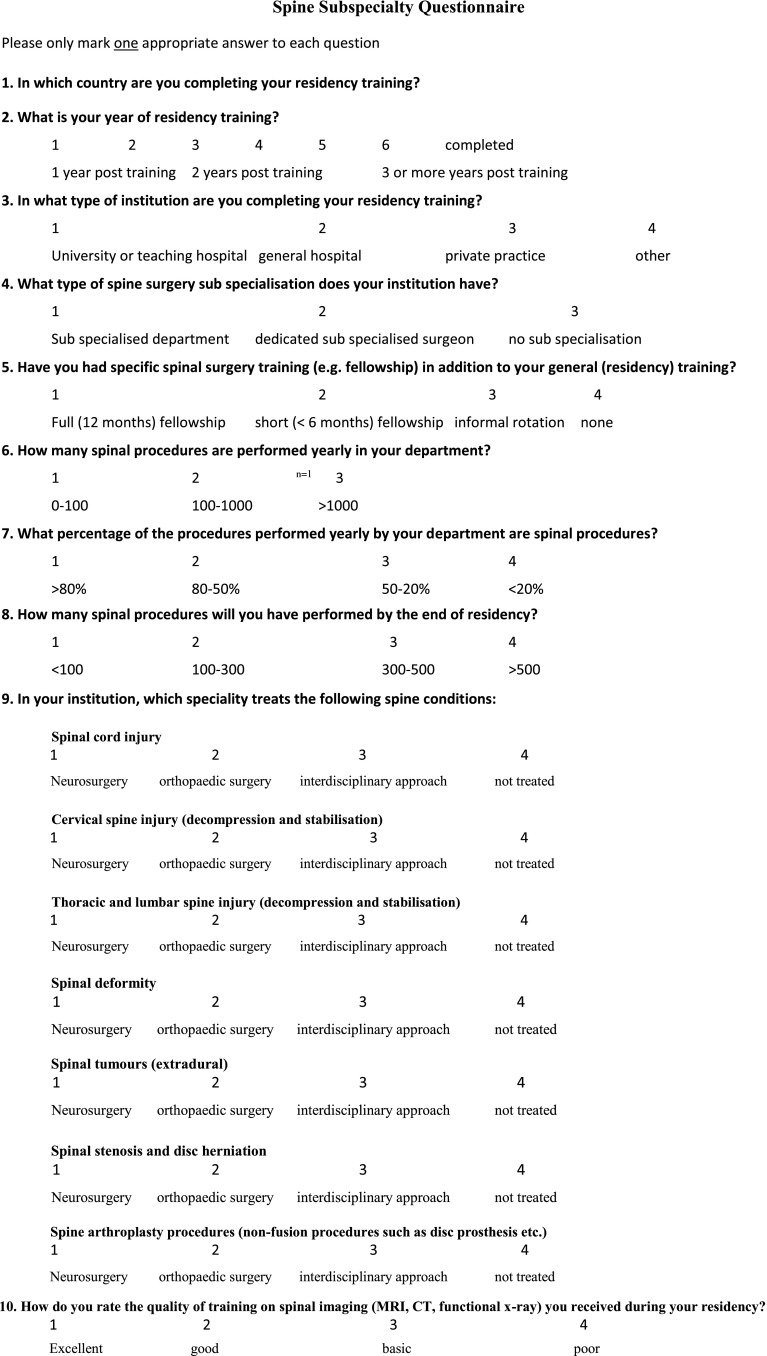

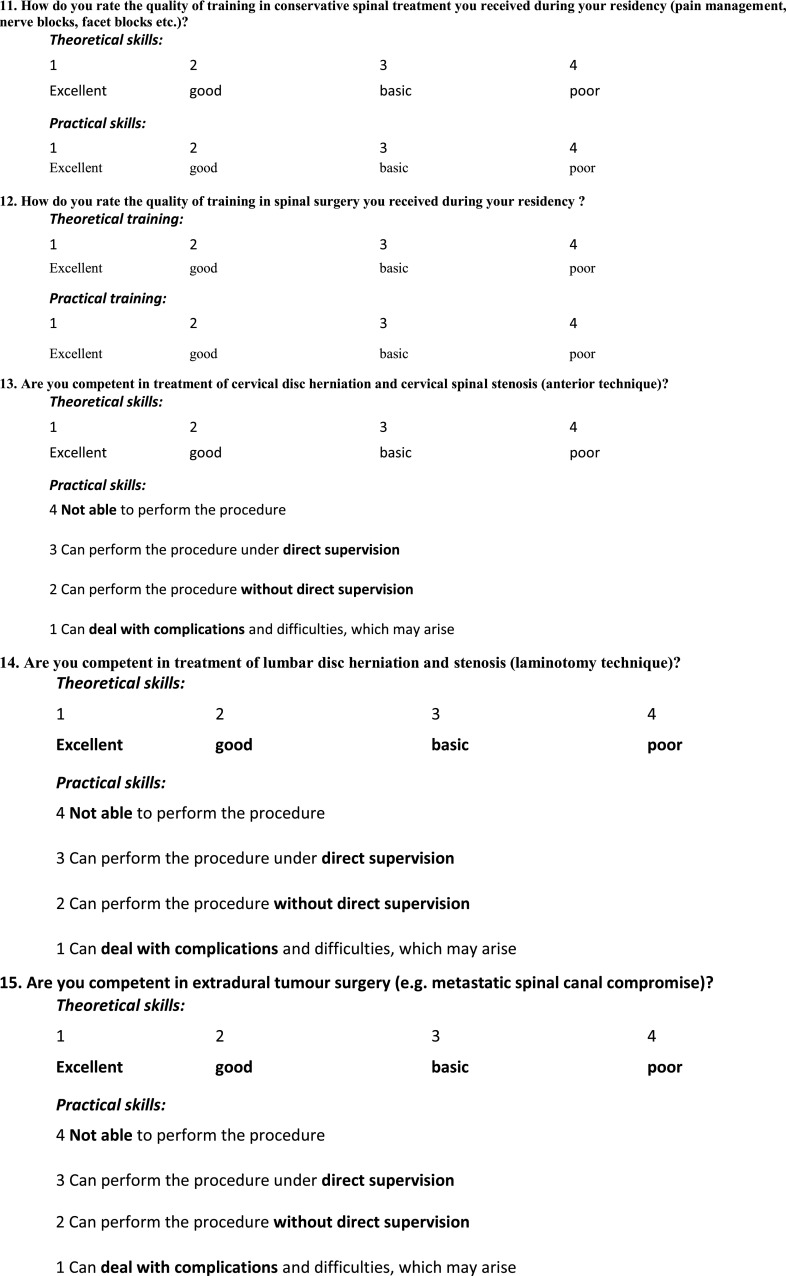

An online questionnaire was devised based on a previously published fellowship assessment questionnaire [3] and distributed amongst AOSpine members in Europe via the AOSpine website. It consisted of 60 questions and enquired about previous surgical training, fellowships and their nature, and both theoretical and practical competency amongst basic and advanced spinal conditions. Details of previous surgical training included the year and type of residency training, as well as the perceived quality of training and exposure to spinal conditions. The presence of any fellowships was recorded. Competence in a total of 15 areas of spinal surgery has been covered, including both the theoretical and practical aspects.

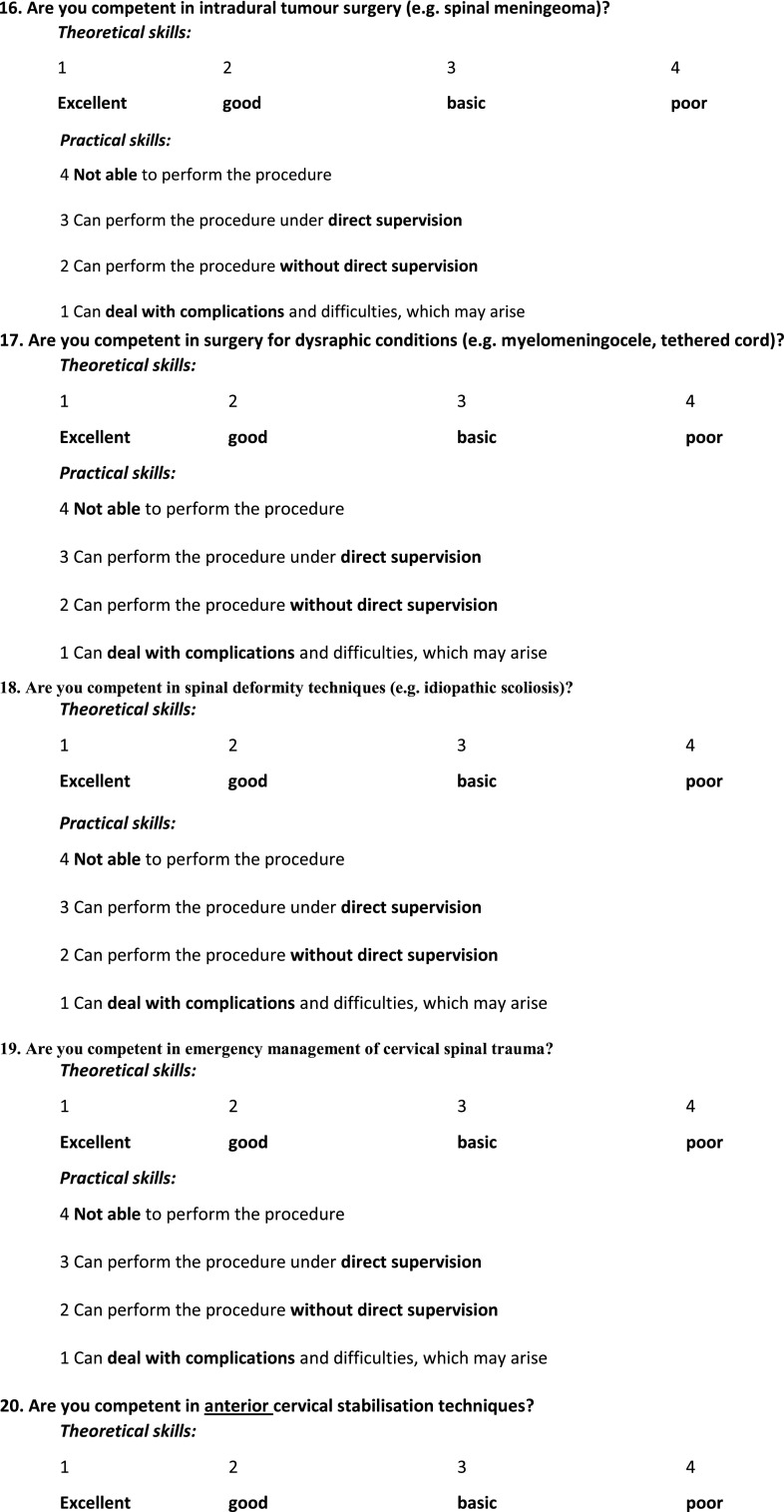

Theoretical skills competence was graded on a 4-point scale and described as “excellent”, “good”, “basic” or “poor”. Theoretical competence was defined as an “excellent” or “good” understanding the condition (see Appendix—Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of competence of theoretical aspects of spinal surgery in AOSpine members who completed spinal fellowship training (full) versus those who did not (none)

| Excellent | Good | Basic | Poor | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full | None | Full | None | Full (%) | None (%) | (%) | Full | None | Full | None | |

| Elective | |||||||||||

| Cervical disc herniation and cervical stenosis | 41 | 62 | 22 | 87 | 79 | 71 | −7 | 7 | 31 | 0 | 18 |

| Lumbar disc herniation and stenosis | 53 | 88 | 18 | 81 | 89 | 81 | −8 | 1 | 21 | 0 | 5 |

| Extradural tumour surgery | 41 | 54 | 17 | 83 | 73 | 66 | −7 | 8 | 36 | 5 | 23 |

| Intradural tumour surgery | 13 | 37 | 15 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 0 | 15 | 53 | 22 | 67 |

| Surgery for dysraphic conditions | 3 | 15 | 18 | 64 | 26 | 38 | 12 | 24 | 51 | 26 | 66 |

| Spinal deformity | 26 | 30 | 28 | 55 | 68 | 41 | −27 | 10 | 75 | 8 | 38 |

| Emergency | |||||||||||

| Cervical spine trauma | 43 | 70 | 23 | 82 | 83 | 73 | −10 | 5 | 31 | 1 | 9 |

| Anterior cervical stabilisation | 49 | 85 | 18 | 66 | 84 | 72 | −12 | 2 | 36 | 3 | 8 |

| Posterior cervical stabilisation | 44 | 55 | 17 | 76 | 76 | 63 | −14 | 11 | 49 | 0 | 12 |

| Cranio-cervical stabilisation | 24 | 45 | 29 | 69 | 66 | 55 | −12 | 13 | 51 | 4 | 28 |

| Lumbar and thoracic trauma | 49 | 76 | 19 | 85 | 85 | 77 | −8 | 3 | 32 | 0 | 4 |

| Posterior thoracic and lumbar stabilisation | 55 | 91 | 14 | 84 | 86 | 84 | −3 | 1 | 18 | 0 | 3 |

| Anterior lumbar and thoracic stabilisation. | 37 | 53 | 25 | 75 | 78 | 61 | −16 | 19 | 54 | 1 | 16 |

| Complications | |||||||||||

| Posterior dural teras | 49 | 63 | 19 | 94 | 85 | 75 | −10 | 6 | 29 | 8 | |

| Vascular complications of anterior thoracic and lumbar stabilisation | 16 | 22 | 29 | 65 | 56 | 42 | −15 | 18 | 72 | 9 | 38 |

Competence defined as “excellent” or “good” understanding of the condition

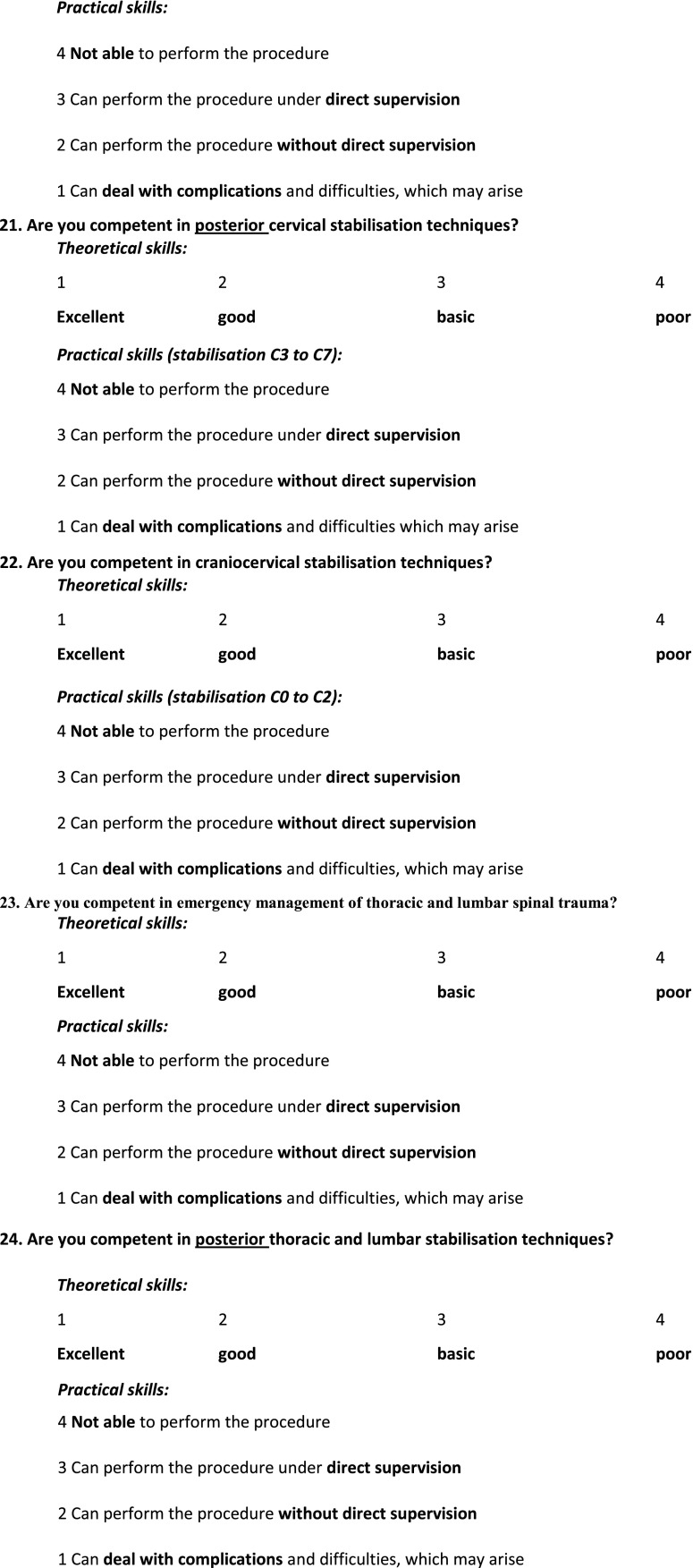

Practical skill competence was also graded on a 4-point scale and described as “not able to perform the procedure”, “can perform the procedure under direct supervision”, “can perform the procedure without direct supervision” and “can deal with the complications and difficulties which may arise”. Respondents were deemed to have achieved practical skill competence if they were able to perform the procedure without direct supervision or were able to deal with complications and difficulties which may arise (see Appendix—Table 3).

Table 3.

Assessment of competence of practical aspects of spinal surgery in AOSpine members who completed spinal fellowship training (full) versus those who did not (none)

| Can deal with complications | Perform without supervision | Perform with supervision | Not able to perform | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full | None | Full | None | Full (%) | None (%) | (%) | Full | None | Full | None | |||

| Elective | |||||||||||||

| Cervical disc herniation and cervical stenosis | 44 | 82 | 17 | 40 | 61 | 122 | 76 | 58 | −18 | 7 | 37 | 3 | 38 |

| Lumbar disc herniation and stenosis | 57 | 113 | 12 | 32 | 69 | 145 | 86 | 69 | −17 | 2 | 36 | 0 | 16 |

| Extradural tumour surgery | 44 | 70 | 9 | 43 | 53 | 113 | 66 | 54 | −12 | 13 | 43 | 3 | 35 |

| Intradural tumour surgery | 12 | 43 | 10 | 18 | 22 | 61 | 28 | 29 | 2 | 17 | 28 | 29 | 100 |

| Surgery for dysraphic conditions | 7 | 24 | 13 | 22 | 20 | 46 | 25 | 22 | −3 | 12 | 45 | 38 | 105 |

| Spinal deformity | 32 | 34 | 14 | 20 | 46 | 54 | 58 | 26 | −32 | 16 | 63 | 11 | 75 |

| Emergency | |||||||||||||

| Cervical spine trauma | 45 | 79 | 21 | 44 | 66 | 123 | 83 | 59 | −24 | 7 | 44 | 1 | 30 |

| Anterior cervical stabilisation | 46 | 87 | 18 | 34 | 64 | 121 | 80 | 58 | −22 | 5 | 44 | 3 | 29 |

| Posterior cervical stabilisation | 43 | 59 | 18 | 42 | 61 | 101 | 76 | 48 | −28 | 10 | 53 | 1 | 38 |

| Cranio-cervical stabilisation | 26 | 42 | 22 | 43 | 48 | 85 | 60 | 41 | −19 | 18 | 48 | 5 | 61 |

| Lumbar and thoracic trauma | 52 | 85 | 16 | 34 | 68 | 119 | 85 | 57 | −28 | 4 | 52 | 0 | 23 |

| Posterior thoracic and lumbar stabilisation | 57 | 102 | 12 | 48 | 69 | 150 | 86 | 72 | −14 | 2 | 29 | 0 | 17 |

| Anterior lumbar and thoracic stabilisation. | 33 | 51 | 20 | 34 | 53 | 85 | 66 | 41 | −26 | 13 | 50 | 4 | 60 |

| Complications | |||||||||||||

| Posterior dural tears | 45 | 94 | 19 | 47 | 64 | 141 | 80 | 67 | −13 | 5 | 38 | 15 | |

| Vascular complications of anterior thoracic and lumbar stabilisation | 18 | 17 | 19 | 32 | 37 | 49 | 46 | 23 | −23 | 25 | 61 | 11 | 85 |

Competence defined as being able to perform the procedure without direct supervision (good), or being able to perform the procedure without direct supervision and being able to deal with complications and difficulties, which may arise (excellent)

Results

A complete response to the questionnaire was provided by 289 AOSpine Europe members (13 % response rate) from 32 countries. 64 % of respondents were trained as orthopaedic surgeons, and 31 % were trained as neurosurgeons (5 % did not elaborate). Eighty (28 %) had undertaken a full 12-month fellowship (see Appendix—Table 1) and 83 % of those undertaking a fellowship did so in a teaching hospital, with the remaining 17 % working in a general hospital or private practise.

Table 1 .

Assessment of the fellowship experience amongst AOSpine members

| Duration of fellowship | Full (12 months) fellowship | Short fellowship (<6 months) | Informal rotation | None | No recorded response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 80 | 47 | 78 | 73 | 11 |

A significant difference in competency levels was defined as a 20 % difference between AOSpine members who have undertaken a full fellowship versus those who have not. Our results have demonstrated that there was no significant difference in theoretical knowledge or practical skills between those who have been trained as orthopaedic surgeons versus those trained as neurosurgeons. However, significant differences were noted when the group which completed fellowship training was compared to those who have not.

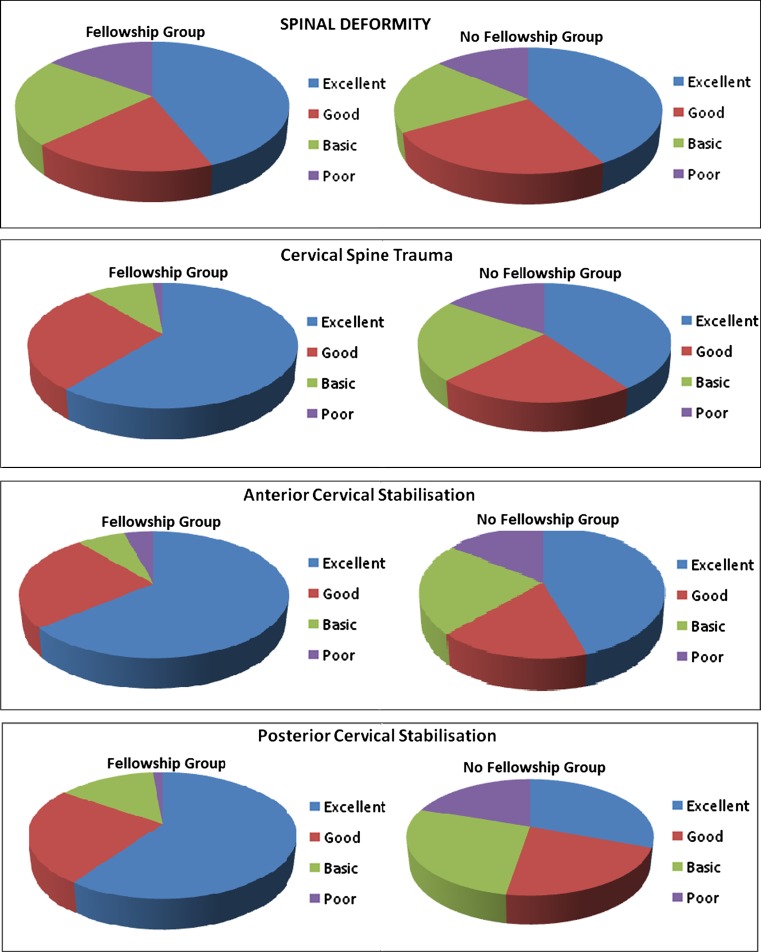

With regards to theoretical knowledge, respondents from both groups were competent in the majority of areas related to spine surgery, excluding competency in spinal deformity, where a 27 % increase in competency was seen when upon completion of a fellowship. Significant differences began to emerge when assessing practical skill competency, especially in the management of emergency conditions with both groups exhibiting a similar level of competence in the surgical management of elective conditions. The only exception was the surgical management of spinal deformity, where a difference of 32 % was noted in favour of the fellowship group.

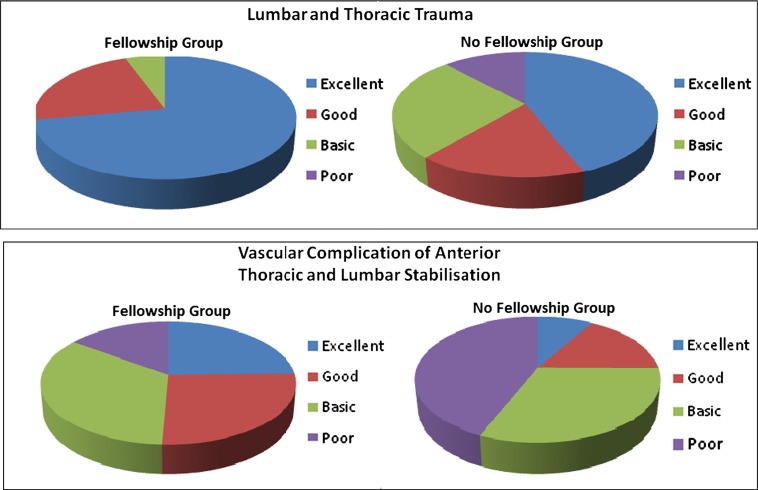

With regards to emergency surgical procedures, our results demonstrated a significant difference in the competency levels of those who had undertaken a full fellowship, versus those who had not, in the following areas: cervical spine trauma (24 %), anterior cervical stabilisation (22 %), posterior cervical stabilisation (28 %), lumbar and thoracic trauma (28 %), anterior lumbar and thoracic stabilisation (26 %) and its complications (23 %).

A competency assessment of the fellowship group was performed in addition (Appendix—Table 2). This revealed that 10 % of AOSpine post-fellowship members cannot perform an anterior cervical stabilisation without supervision and 27.5 % were unable to perform an anterior lumbar stabilisation without direct supervision. 24 % of the group reported to be unable to perform posterior stabilisation of the cervical spine without supervision. Posterior stabilisation of the lumbar spine was a procedure that post-fellowship members felt more comfortable with; no members were unable to perform surgery and only 2.5 % required direct supervision. In the management of cervical and lumbar trauma, supervision was required by 20 and 11 % of responders, respectively. In managing complications, 45 % of surgeons who completed a spinal fellowship rated themselves as being able to deal with all post-operative complications, but only 22.5 % stated that they were able to deal with the vascular complications of anterior surgery. Overall, 59 % required supervision to manage vascular complications of anterior lumbar spinal surgery. There was a similar disparity in the management of dural complications (lacerations) in posterior surgery, where 16 % of responders were in need of supervision.

Analysis of the quality of previous training (appendix—Table 4) revealed that 66 % of respondents were competent in spinal imaging at the end of their orthopaedic/neurosurgical training. 73 % were competent in spinal surgery (both theory and practise), and 50 % were competent in the use of a microscope. Interestingly, of the whole group only 43 % were competent in the actual practise of conservative management of spinal conditions (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Analysis of the quality of training and its association with competence, defined as an “excellent” or “good” comprehension of given topics

| Quality of training | Excellent | Good | Basic | Poor | No response | Number competent | Percentage competent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative management (theory) | 32 | 127 | 80 | 37 | 13 | 159 | 55 |

| Conservative management (practise) | 33 | 92 | 92 | 56 | 16 | 125 | 43 |

| Spinal imaging | 77 | 115 | 65 | 16 | 16 | 192 | 66 |

| Use of microscope | 83 | 62 | 68 | 56 | 20 | 145 | 50 |

| Spinal surgery (theory) | 68 | 142 | 52 | 9 | 18 | 210 | 73 |

| Spinal surgery (practise) | 81 | 129 | 52 | 14 | 13 | 210 | 73 |

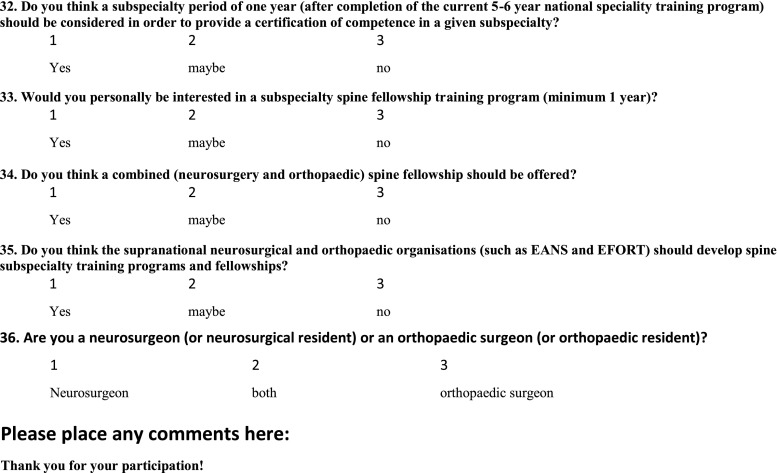

Figs. 1–7.

Comparison of competence in performing spinal procedures in AOSpine members who completed a spinal fellowship versus those who have not. Poor not able to perform the procedure, Basic able to perform the procedure under direct senior supervision, Good able to perform the procedure without supervision, Excellent able to deal with all complications and difficulties which may arise

Discussion

Subspecialisation is becoming increasingly more prevalent in medicine, resulting in more cost-effective and comprehensive patient care [3, 7]. Due to the great number of different conditions embraced by spinal surgery, orthopaedic and neurosurgical training are unable to cover all aspects of treatment leaving some trainees with deficits in the management of even the most prevalent spinal conditions [7]. A comprehensive list of spinal conditions that both residencies should be familiar with can be found in Herkowitz et al. Resident and fellowship guidelines: educational guidelines for resident training in spinal surgery [8]. Even the most respected accredited residency training programmes will not be able to fully prepare the surgeon to be competent in the vast and complex area of spinal surgery.

It is advised, therefore, that those intending to specialise in spinal surgery should pursue additional training with a sufficient caseload to ensure adequate exposure to spinal pathology, which is the most important predictor of both the surgeons’ subjective confidence and improved patient outcomes [2, 5, 9, 10].

The majority of AOSpine members who responded to the questionnaire came from an orthopaedic background. This is surprising given the fact that spinal surgery is a more popular career choice amongst neurosurgically trained surgeons [2, 11, 12]. It is difficult to establish whether this finding is a result of a disparity in the response rate between orthopaedic surgeons and neurosurgeons or whether it is due to the high prevalence of orthopaedic surgeons in the AOSpine organisation; however, similar trends have been observed in previous studies [2, 13].

Despite differences in training and variable exposure to spinal ailments, the results of our survey indicated that self-assessed competency of orthopaedic and neurosurgical trainees in their theoretical and practical aspects of the spinal training was similar. These findings are not consistent with outcomes of similar research in the field. Previous studies have shown that neurosurgical residents are more competent at performing spine-related procedures than their orthopaedic colleagues [2, 12]. This is largely due to the amount of training devoted to spine-related disease, which is a major constituent of the neurosurgical training agenda.

Significant differences in time and exposure to spine training differentiated the neurosurgical and orthopaedic residencies (37 and 16 % of total residency time devoted to spine, respectively) [2]. Orthopaedic training focuses on the entirety of the musculoskeletal system, including bone physiology, musculoskeletal malignancy and rehabilitation. The exposure to spinal conditions is restricted, as it is assumed that orthopaedic residents wishing to further pursue the specialty of spinal surgery will enrol in further subspecialty training [12]. There is a possibility that our results have been subjected to responder bias, or results were influenced by the fact that the study was performed on groups, which were specifically interested in spine surgery. Orthopaedic trainees may have had significant exposure to spinal disease for a prolonged period of time following their residency, allowing them to achieve a similar level of competence in this subspecialty to neurosurgeons.

Training in European residency spinal programmes has clear strengths, especially in the field of spinal surgery, where a majority of trainees become competent at managing elective procedures. Regardless of the speciality, weakness was displayed in the conservative management of spinal conditions, where only 43 % of respondents felt confident in the area.

In a previous study, it was shown that a significant proportion of senior orthopaedic/neurosurgical residents are actively interested in pursuing further education in spinal surgery [3]. This trend can be seen in multiple surgical specialties, where upon completing specialist training, surgeons embark on further subspecialty training [4]. In the field of orthopaedics, over 60 % of surgeons enrol in some form of fellowship after the completion of specialty training [7]. Further education allows for improvement in areas that were not covered in depth in residency training, making the individual not only more employable in the future [7], but allowing for the development of good relationships with a mentor that can last even after the completion of the fellowship.

The results of our study indicate that a fellowship in spinal surgery can significantly improve competence in a number of surgical procedures. A significant (>20 %) difference between those who have completed a fellowship versus those who have not has been noted in the practical aspects of treatment in the following areas of spinal surgery: spinal deformity, cervical spine trauma, cervical stabilisation, lumbar and thoracic trauma and anterior surgery and its complications. This indicates that the fellowship period allows for significant exposure of the fellow to these conditions, allowing for greater proficiency in their management. These findings are in keeping with the belief that experience is positively correlated to improved surgical outcomes [2, 5, 9, 10]. The influence of the spine fellowship on the management of intradural tumour surgery cannot be properly assessed due to a small sample size not representing competence of the AOSpine group as a whole in these types of procedures.

The fellowship group had significantly increased self-perceived competency levels in both the theoretical and practical aspects of spinal deformity when compared with surgeons with no-fellowship training. This finding reflects upon the neurosurgical and orthopaedic residency curricula, which fail to provide the trainees with sufficient exposure to this field of spinal pathology to ensure competency. This is likely to be a consequence of the complexity of the surgical management of spinal deformity, which requires specialised tertiary centres that can individually tailor surgical procedures to each patient [14, 15]. Access to such facilities may not be readily available for a significant proportion of neurosurgical and orthopaedic residents, thus limiting their experience in this field of spinal surgery. We believe that a clearly defined curriculum of a fellowship, with the fellow playing a central role in the management of spinal disorders, should be formulated by a named programme director. It has been suggested previously that a spinal fellowship should incorporate at least 250 cases per year for each fellow [16], and have a wide spectrum of spinal disorders ranging from degenerative disease, deformities and trauma to paediatrics and reconstruction. There should be multidisciplinary input from both orthopaedic and neurosurgical specialists, allowing for the fellow to gain differing perspectives with regards to surgical decision-making in addition to the technical skills necessary for delivering high quality care. The facility must provide the fellow with access to a sufficient number of inpatient and outpatient cases to be able to gain the necessary expertise in the care of spinal patients. The staff should allow for the fellowship to be an educational experience with a strong academic component and refrain from the service-orientated approach. For these reasons, spinal fellowships should be ideally undertaken in large tertiary centres with a high case-per-day ratio and significant experience in managing complex spinal conditions.

Based on the results of the study there is a considerable variation in the competency of post-fellowship spinal surgeons in the management of frequently encountered spinal conditions mainly because of a lack of uniformity in the surgical curriculum, with many fellowships being preceptorships due to inadequate regulation of their content [17].

In our study, 10 % of those who undertook a fellowship cannot perform anterior cervical stabilisation without supervision, which would be deemed unsatisfactory of a spinal surgeon expected to deal with emergent cases. The reason behind this is hard to evaluate, due to the lack of previous research in this area. 24 % of post-fellowship AOSpine members do not feel confident in performing posterior cervical stabilisation without supervision. 27.5 % cannot independently perform anterior lumbar stabilisation; however, 97.5 % are competent at performing posterior lumbar stabilisation. Due to most vertebral lesions affecting the anterior spine [18], it is a logical assumption that one would therefore expect an anterior approach to be in the repertoire of a competent spinal surgeon. However, due to the difficulty of access (need to pass through various anatomical regions), it is rarely performed without the help of appropriate specialists. In addition, fixation methods using this approach are not as good as stabilising vertebral structures as the posterior approach [18]. For these reasons, the anterior approach is less commonly utilised, resulting in reduced competence amongst respondents.

The management of spinal trauma is also an issue, with 20 and 11 % of responders being unable to manage cervical and lumbar trauma, respectively. This is a recognised deficit in spinal surgery training as a whole, with 34–48 % of senior trainees being incompetent in managing such cases [3]. Despite the fellowship having a positive impact on competence in this area, there is still a significant minority who cannot effectively manage these commonly encountered conditions that have a worldwide incidence of 2.5–57.8 per million per annum [19]. This probably results from the variation in fellowship programmes, with some favouring elective procedures at the cost of exposure to emergency cases [7, 16].

Disparity can also be seen in the management of complications arising from spinal surgery, with 59 % requiring supervision when managing vascular complications of anterior lumbar spinal surgery, and 16 % when managing dural complications of posterior surgery. It is a rare complication occurring in only 4 % of lumbar spine procedures [18]. Due to its rarity, respondents are in all likelihood not offered many occasions to familiarise themselves with the treatment of these complications. Since this study only highlights the types of deficiencies, there is a need to further investigate the underlying reasons for all the deficits in the management of these common conditions.

Candidates willing to enrol in fellowships have no official guidelines to evaluate the efficacy of these programmes other than verbal recommendations and/or faculty recognition [8]. We believe that this situation necessitates serious discussion amongst clinical educators and professional organisations and societies to develop innovative training models to accommodate for the increasing knowledge base and reduced training time due to European Working Time Directives. It has been suggested that a complete reappraisal of the educational system, focusing on competency-based training, is the best solution [20]. A thorough evaluation of the fellows’ skills in respect of spinal disease management should be performed at regular intervals throughout the fellowship, and the results communicated to trainees [8]. A minimum of one assessment performed every 6 months is recommended [21, 22]. Performance should be assessed by considering a large volume of separate occurrences, where the fellow has employed skills, knowledge and clinical judgement relevant to the field of spinal surgery. The fellow should also have an opportunity to provide feedback concerning the fellowship itself, discussing it with the programme director. This study is only a catalyst for further discussion, which should concentrate on establishing a standardised core curriculum and objectives in spinal fellowship training. Programmes should ensure adequate exposure to and training in all aspects of spinal surgery. They should be accredited by a central governing body composed of specialists in the area of spinal surgery.

Several limitations of the study require consideration when interpreting this data. The low response rate was due to the size of the AOSpine organisation, which comprises of over six thousand members making an active follow-up of non-responders unfeasible. The low response rate may have introduced an element of non-response bias; however, we do believe that a sample size of 289 responders is sufficient for achieving the objectives of the study. Surgeons were made to assess their own “competence”, which can be translated as a subjective measure of confidence of the individual in performing procedures and understanding concepts related to spinal surgery. As such, it omits the measurement of true aspects of “competence” such as professionalism, bedside manner, objective skill level acquisition etc. Despite the possibility of personal bias, it is reasonable to assume that AOSpine members have developed a basic capacity for honest introspective self-reflection throughout the course of their training.

One may argue that a selection bias is present when comparing the fellowship and the no-fellowship groups. The respondents who chose to undergo a spinal surgery fellowship may have had more motivation and/or baseline competency when compared with AOSpine members who began their clinical practise immediately after residency, thus overestimating the impact of a fellowship in improving theoretical and practical competence in various areas of spinal surgery.

Some of the questions may have been misinterpreted by the participants of the study, and it is difficult to assess the degree of this phenomenon. Data regarding the age of the surgeon and surgical experience were not collected. No enquiries were made regarding the country in which the spinal surgery fellowship was undertaken or the year in which it was completed. Such data would have allowed for the evaluation of spinal surgery fellowship programmes in different countries, as well as for assessing the transformation of spinal surgery fellowship curricula over the years. However, due to the size of the study population, we believe that such comparisons would not bear statistical significance. Other than the respondents’ own perception of exposure to spinal disorders, there has been no quantitative assessment of such exposure, such as patient notes, theatre lists etc.

Conclusions

In order to provide an efficient, routine and emergency service a spinal surgeon should be competent at performing procedures aimed at stabilising acute spinal instability and conditions which threaten neurological structures. A formal fellowship curriculum for spinal training should reasonably ensure such competencies.

There is a significant difference in the self-assessed competency levels of those who had undertaken a full fellowship, versus those who had not, in the following surgical skills: spinal deformity, cervical spine trauma, cervical stabilisation, lumbar and thoracic trauma, anterior and posterior surgery and its complications.

Study data suggest that even after the completion of a formal spinal fellowship, spinal surgeons do not feel that they have achieved competence in managing the vast array of conditions embraced by spinal surgery, which indicates that support from more experienced colleagues is necessary in the initial period following completion of training.

The study did not reveal any significant difference in theoretical knowledge or practical skills between orthopaedic surgeons and neurosurgeons in the field of spine surgery among AOSpine members.

Acknowledgments

AOSpine; Jim Hegarty (senior data administrator; Centre for Spinal Studies and Surgery, Nottingham University Hospitals). No funding or grants were provided for this paper.

Conflict of interest

None.

Appendix

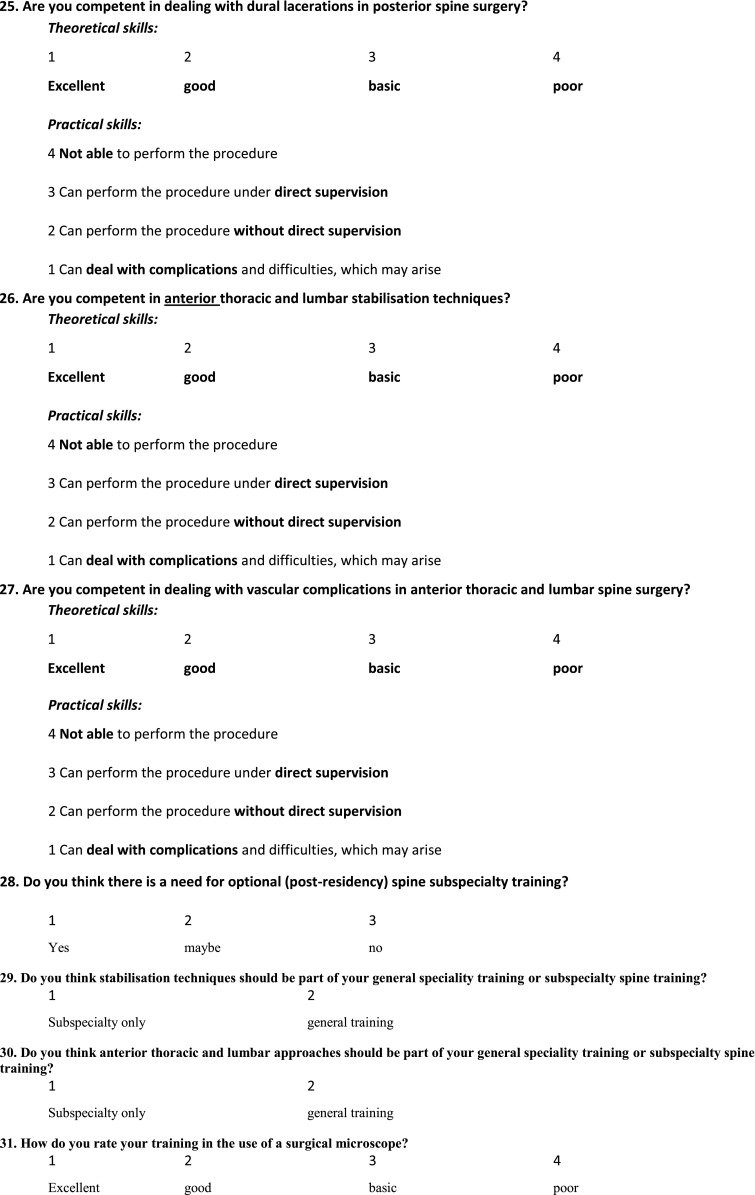

See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Copy of the questionnaire which was available on the AOSpine website

Contributor Information

Wojciech Konczalik, Phone: +447815914826, Email: wojtekonczalik@gmail.com.

Sherief Elsayed, Phone: +447980299325, Email: elsayed@professionalmedical.co.uk.

Bronek Boszczyk, Phone: +441159249924, Email: bronek.boszczyk@nuh.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Mulholland RC, Clamp JC, Boszczyk BM. A short history of spinal training and outlook on spine speciality development in the UK 1948–2013. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(Suppl. 1):S1–S4. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2667-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dvorak M, et al. Confidence in spine training among senior neurosurgical and orthopaedic residents. Spine. 2006;31(7):831–837. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000207238.48446.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boszczyk B, et al. Spine surgery training and competence of European neurosurgical trainees. Acta Neurochir. 2009;151(6):619–628. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bass BL. Early specialization in surgical training: an old concept whose time has come? Semin Vasc Surg. 2006;19(4):214–217. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodrow SI, et al. Training and evaluating spinal surgeons—the development of novel performance measures. Spine. 2007;32(25):2921–2925. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815b6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitale MA, et al. Comparison of the volume of scoliosis surgery between spine and pediatric orthopaedic fellowship—trained surgeons in New York and California. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2687–2692. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garfin SR. Editorial on residencies and fellowships. Spine. 2000;25(20):2700–2702. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herkowitz HN, et al. Resident and fellowship guidelines: educational guidelines for resident training in spinal surgery. Spine. 2000;25(20):2703–2707. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chumas P, et al. Safe paediatric neurosurgery 2001. Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16(3):208–210. doi: 10.1080/02688690220148806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallah A, et al. Do supspecialized neurosurgeons experience higher complication rates for nonsubspecialty emergent surgery. Surg Neurol. 2009;72(1):98–99. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamartina C. Spine surgery in Italy between neuro and ortho surgeons. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(Suppl. 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaccaro A. Point of view: confidence in spine training among senior neurosurgical and orthopaedic residents. Spine. 2006;31(7):838. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000207476.28516.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grauer JN, et al. Similarities and differences in the treatment of spine trauma between surgical specialties and location of practice. Spine. 2004;29(6):685–696. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000115137.11276.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(10):925–948. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janicki J, Alman B. Scoliosis: review of diagnosis and treatment. Peadiatr Child Health. 2007;12(9):771–776. doi: 10.1093/pch/12.9.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuire K. Spine fellowships. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:244–248. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224070.08535.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eismont F. The education, training and evaluation of a spine surgeon. Spine. 1996;21(18):2059–2063. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199609150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis C et al (2011) How we treat recent thoracic and lumbar spine fractures. Viewed 24 August, 2011 Available from:http://www.maitrise-orthop.com/corpusmaitri/orthopaedic/mo58_spine_fracture/mo58_spine_fractures.shtml

- 19.Boran S, et al. A 10-year review of sports-related spinal injuries. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180(4):859–863. doi: 10.1007/s11845-011-0730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyota BD. The impact of subspecialization on postgraduate medical education in neurosurgery. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(5):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benzel E, Dwyer A, Herkowitz H. Controversies in spine: should there be subspecialty certification in spine surgery? Spine. 2002;27(13):1478–1483. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200207010-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke RM, et al. The neurosurgical training curriculum in Australia and New Zealand is changing. Why? J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(2):115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]