Abstract

Importance

Community-based efforts to prevent adolescent problem behaviors are essential to promote public health and achieve collective impact community-wide.

Objective

To test whether the Communities That Care (CTC) prevention system reduced levels of risk and adolescent problem behaviors community-wide 8 years after implementation of CTC.

Design

A community-randomized trial.

Setting

Twenty-four small towns in 7 states, matched within state, assigned randomly to control or intervention group in 2003.

Participants

All fifth-grade students attending public schools in study communities in 2003-04 who received consent from their parents to participate (76.4% of eligible population). A panel of 4407 fifth graders was surveyed through 12th grade with 92.5% of the sample participating at the last follow-up.

Intervention

A coalition of community stakeholders received training and technical assistance to install CTC, used epidemiologic data to identify elevated risk factors and depressed protective factors for adolescent problem behaviors in the community, and implemented tested and effective programs for youths aged 10 to 14, their families, and schools to address their community's elevated risks.

Main Outcome Measures

Levels of targeted risk; sustained abstinence and cumulative incidence by grade 12 and current prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use, delinquency, and violence in 12th grade.

Results

By spring of 12th grade, students in CTC communities were more likely than students in control communities to have abstained from: any drug use (RR=1.32; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.63); drinking alcohol (RR=1.31; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.58); smoking cigarettes (RR=1.13; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.27), and engaging in delinquency(RR=1.18; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.26). They were also less likely to ever have committed a violent act (RR=0.86; 95% CI 0.76 to 0.98). There were no significant differences by intervention group in targeted risks, the prevalence of past-month or past-year substance use, or past-year delinquency or violence.

Conclusions and Relevance

Using the CTC system continued to prevent the initiation of adolescent problem behaviors through 12th grade, 8 years after implementation of CTC and 3 years after study-provided resources ended, but did not produce reductions in current levels of risk or current prevalence of problem behavior in 12th grade.

INTRODUCTION

Community-based efforts to prevent substance use, delinquency, and violence are an essential component of promoting health during adolescence and later life.1,2 Communities That Care (CTC) is a prevention system that activates a coalition of stakeholders to develop and implement a science-based approach to prevention in the community to achieve collective impact on youth development community-wide. 3, 4 CTC seeks to achieve this goal by increasing the use of tested, effective preventive interventions that address risk factors for adolescent problem behaviors prioritized by the community. This is expected to produce community-wide reductions in targeted risk factors and, in turn, decreased adolescent substance use, delinquency, and violence.3, 5

CTC is different from other efforts to mobilize communities for the prevention of adolescent problem behaviors (e.g., the Midwestern Prevention Project,6-8 Project Northland,9 Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol,10 the Community Trials Intervention to Reduce High Risk Drinking,11,12 and PROSPER13). CTC does not focus exclusively on the prevention of alcohol use but rather on reducing shared risk factors for multiple behavior problems. CTC does not prescribe specific programs, but trains the local coalition to choose programs from a menu of tested programs that best address the community's unique profile of risk and protection. In contrast to PROSPER, CTC does not prescribe who leads the prevention efforts, but encourages stakeholders from a variety of organizations in the community to take leadership.

Results from a community-randomized trial of CTC support the CTC theory, 3,5 including increased adoption of a science-based approach to prevention14,15,16 and implementation of a greater number of tested and effective prevention programs.17 The trial also found that CTC lowered targeted risks for problem behavior and reduced the incidence and prevalence of 7th and 8th grade delinquency and substance use in a panel of youth followed since fifth grade 3 and 4 years after initial implementation of CTC.18,19 These reductions continued to be observed two years later in 10th grade, 6 years after initial implementation of CTC and one year after support for the implementation of CTC had ended in the trial.20

This study tested the enduring effects of CTC on risk exposure and youth problem behaviors in 12th grade, 3 years after study-provided resources ended and 8 years after initial implementation of CTC in the trial. Although most CTC coalitions continued during the unsupported period,21,22 very few of them used tested and effective prevention programs targeting high school students. The primary outcomes expected to be affected by CTC and examined in the present study are targeted risk factors, substance use, delinquency, and violence.23

METHODS

The Community Youth Development Study (CYDS)5 is a community-randomized trial of CTC. Twenty-four communities in the states of Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Oregon, Utah, and Washington were matched in pairs within state, on population size, racial and ethnic diversity, economic indicators, and crime rates. One community from within each matched pair was assigned randomly by a coin toss to either the intervention (CTC) or control group.5 CYDS communities are small- to moderate-sized incorporated towns with their own governmental, educational, and law enforcement structures, ranging from 1500 to 50 000 residents.

Beginning in the summer of 2003, intervention communities received CTC training over the course of 6 to 12 months by certified trainers. CTC coalition members were trained to use data from cross-sectional CTC Youth Surveys of public school students in the community to prioritize risk factors to be targeted by tested and effective preventive actions.24,25 Although CTC is designed for children and youth ages 0-18 years, CYDS communities were asked to focus their prevention plans on programs for youths aged 10 to 14 and their families and schools so that possible effects on drug use and delinquency could be observed within the initial 5-year study period. Starting with the 2004-2005 school year and annually thereafter, community coalitions implemented between 1 and 5 preventive programs to address their prioritized risk factors. These included universal school-, family-, and community-based programs and selective school and community programs targeted at youths at elevated risk. CYDS staff provided technical assistance and support for preventive interventions throughout the 5-year efficacy trial, but stopped after the fifth year of the study. Control communities received data from CTC Youth Surveys administered in their schools every 2 years, but no resources, training, or technical assistance from the study.

Sample and Data Collection

Data were from a longitudinal panel of public school students in the 24 CYDS communities followed from grade 5 through grade 12 (N=4407).23 Students were surveyed annually (2004-2011), except in 11th grade when students were tracked but not surveyed. The sample is gender balanced (50% male). Twenty percent of students identified as Hispanic/Latino, 64% were non-Hispanic white, 3% non-Hispanic African American, 5% non-Hispanic Native American, 1% non-Hispanic Asian American, and 6% other ethnicities. All students in fifth-grade classrooms during the 2003-2004 school year in the 24 CYDS communities were eligible for participation in the study. Recruitment continued in grade 6 to increase the overall participation rate. Parents of 4420 students consented to their participation in the study (76.4% of the total eligible population; 76.1% in CTC and 76.7% in control communities). The first wave of data collection (fifth grade, 2004) was a pre-intervention baseline assessment. The seventh wave of data was collected in the spring of 2011 when panel students progressing normally were in grade 12. At this point, 10 of the original 12 CTC coalitions were still active but had not received any support from the study for 3 years. 21, 22 Tested and effective programs that were still being implemented in CTC communities during this unsupported period continued to be aimed primarily at middle school-aged adolescents (grades 5 through 9). Only 4 CTC communities implemented 1 of 3 substance abuse prevention programs aimed at high school-aged youths (Project Toward No Drug Abuse, Class Action, or Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol) during this period. Therefore, few panel students were exposed during the high school years to tested and effective prevention programs selected through the CTC process.

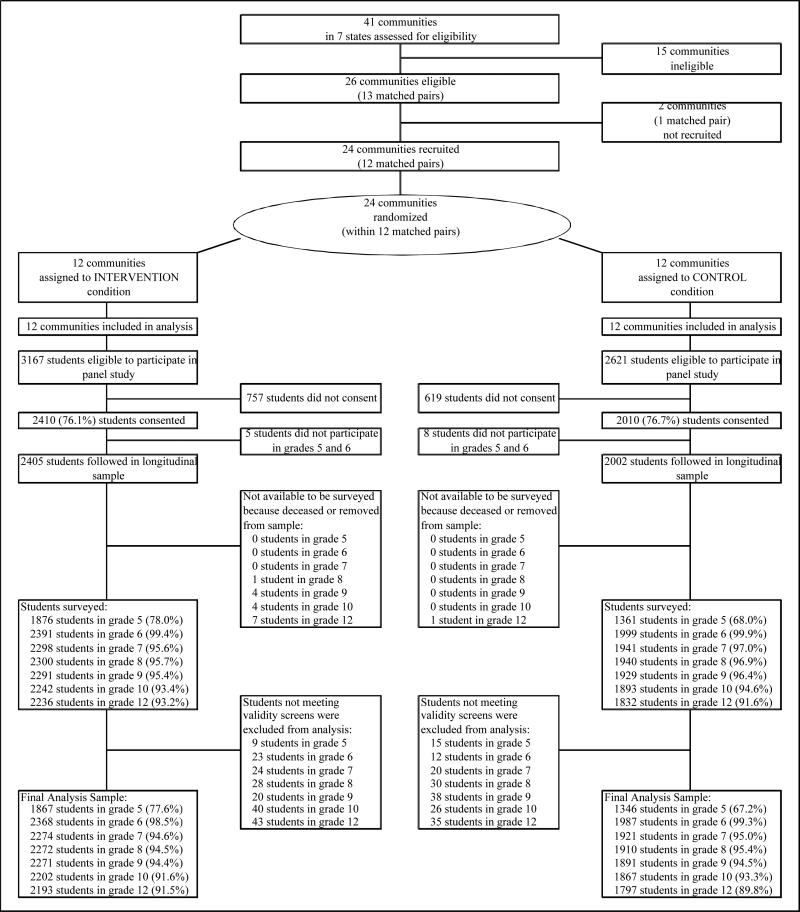

The longitudinal panel consists of 4407 students who completed a wave 1 or wave 2 survey. Students in the longitudinal panel who remained in the intervention or control communities for at least 1 semester were tracked and surveyed, even if they left the community, moved schools or dropped out.23 Seven students were deceased by the 12th grade data collection and 2 students were permanently excluded from the sample due to disability that precluded them from filling out the survey, leaving an active still-living sample of 4398 students. Of the still-living sample members, 92.5% (n=4068) completed the survey in 12th grade; 93.2% (n=2236) in CTC communities and 91.6% (n=1832) in control communities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of communities and participants in the randomized trial.

Students completed the Youth Development Survey (YDS),26 a self-administered paper-and-pencil questionnaire designed to be completed in a class period. In 12th grade, 26 percent of participants completed the survey online because they were no longer attending school. Identification numbers but no names or other identifying information were included on the surveys. Participants received a $10 incentive check after completing the survey. The University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee approved this protocol.

Measures

Targeted Risk Factors

CTC coalitions prioritized between 2 to 5 risk factors that were elevated in their community based on anonymous cross-sectional surveys of all assenting sixth- and eighth-grade students in their community.27,28 Data used for targeting decisions were different from those used in the present analysis to evaluate intervention effects on risk factors. The cohort of 5th graders followed in the trial did not participate in the cross-sectional surveys.

A targeted risk factor score was calculated for panel students in CTC communities by averaging the community-specific set of targeted risk factors. Items comprising each risk factor scale were standardized within each year and each scale was then standardized across years to facilitate pre-post comparisons. Because control communities did not prioritize risk factors using the CTC process, the average risk factor score in control communities was calculated using the set of targeted risk factors identified in its matched CTC community For example, for students in community pair A, the targeted risk factor score was the average of scale scores for family conflict, antisocial friends, peer rewards for antisocial behavior, attitudes favorable to antisocial behavior, and rebelliousness; for students in community pair B, the targeted risk factor score was calculated based on scale scores for low commitment to school, family conflict, and antisocial friends (eTable 1 in the supplementary online materials shows the community-specific sets of targeted risk factors for all intervention communities).

Substance Use

Students reported their lifetime and past-month use of substances in grades 5 through 12 and past-year substance use in grade 12. Based on these prospective data, we examined sustained abstinence from any substance use, use of gateway drugs (alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana), and binge drinking (having 5 or more drinks in one occasion) through grade 12 to assess the overall effect of CTC on preventing substance use. Cumulative incidence was examined for substances where use by grade 12 was less common than non-use (i.e., at least 50% of the sample reported never using by grade 12). 12th grade prevalence rates in the past month and the past year were computed for individual substances as well as composite indexes of any substance use and gateway drugs (alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana).

Delinquent and Violent Behavior

Each year, students reported participation in 7 delinquent and violent acts (stealing, damaging property, shoplifting, attacking someone with intent to harm, carrying a handgun, being arrested, and beating up someone so badly that they probably needed medical attention). A subset of the delinquency items (attacking someone with intent to harm, carrying a handgun, and beating up someone) was used to measure violent behavior. We computed sustained abstinence from delinquency and cumulative incidence of violence through spring of grade 12 as well as the past-year prevalence of both outcomes in grade 12. We also examined the number of different delinquent acts (ranging from 0 to 7) and different violent behaviors (ranging from 0 to 3) in the past year in grade 12.

Student and Community Characteristics

Student-level covariates included age, sex, race (white versus nonwhite), Hispanic ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic), parental education, attendance at religious services during grade 5 (1=never to 4=about once a week or more), and rebelliousness in grade 5 (mean of 3 items; Cronbach's α=.69). Community-level covariates included the total population of students in the community (M=2628; SD=1917) and the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price school lunch (M=38.2%; SD=13.8%).

Analysis Sample and Missing Data Procedures

Overall, 91.4% (n=4021) of students in the active still-living sample participated in at least 6 of the 7 waves of data collection, and item non-response was small (<1%). Based on validity criteria (e.g., reporting not being honest and using a fictitious drug), 78 students were excluded from the analysis sample in grade 12 (35 students in control and 43 students in CTC communities), resulting in valid data from 3990 students in 12th grade (90.7% of the active, still-living sample; 1797 students [89.8%] in control, and 2193 students [91.5%] in CTC communities).

Of all the data points involved in the analysis (= N × number of variables)29, 11.8% were missing (10.8% in the CTC group and 13.0% in the control group). Missing data were imputed using multiple imputations to obtain unbiased estimates of model parameters and their standard errors assuming that data are missing at random.30 Using NORM version 2.03,31 40 datasets including data from all 7 waves were imputed separately by intervention group.32 Analyses were conducted within each imputed dataset and then averaged using Rubin's rules.33

Analyses

Because communities rather than students were randomized within matched community pairs, the effect of CTC was estimated as the mean difference between intervention groups in community-level sustained abstinence, cumulative incidence, prevalence, and means. Since community randomization does not guarantee equivalent student populations or that community pairs will remain similar over time, all analyses were adjusted for student and community characteristics and the respective pre-intervention baseline measure of the outcome to improve the precision of estimated intervention effects.23,34,35 All covariates were grand-mean centered.

Sustained abstinence and cumulative incidence was assessed among students who had not yet engaged in the behavior at baseline (grade 5). Current prevalence in the 12th grade and targeted risk factor scores were examined in the full sample.

Generalized Linear Mixed Models36,37 with random effects for intercepts were used to model variability in outcomes across 4407 students, 24 communities, and 12 community pairs. Linear regression was used to estimate mean differences between CTC and control communities in average levels of targeted risk factors in grade 12, adjusting for baseline levels of targeted risk. Poisson regression with a log link and binomial error distribution was used to estimate adjusted risk ratios (ARRs) for sustained abstinence, cumulative incidence, and current prevalence.38,39 Adjusted odds ratios estimated using logistic regression can be found in eTables 2 to 4 in the supplementary online materials.

The statistical significance of intervention effects was tested with 9 degrees of freedom (number of community-matched pairs (12) minus the number of community-level covariates (2), minus 1) and a .05 type I error rate (2-tailed). All analyses were conducted using HLM 740 and population-average results are reported.41

RESULTS

Baseline Intervention Group Equivalence

There were no statistically significant baseline differences by intervention group in levels of average targeted risk factors, the incidence and prevalence of substance use, delinquency, and violence, or the mean number of delinquent and violent acts.18,23 Accretion and attrition were similar in both intervention groups.

Targeted Risk

The adjusted mean difference between intervention groups in the targeted risk factor score in grade 12, adjusting for baseline levels of targeted risk and student and community characteristics, was not statistically significant (adjusted mean difference = 0.07; 95% CI −0.03 to 0.18; p = .16).

Sustained Abstinence and Cumulative Incidence

Youth in CTC communities were significantly more likely than youth in control communities to have abstained from any substance use and the use of gateway drugs through the spring of 12th grade (Table 1). The proportion of 12th graders who had never used alcohol and who had never smoked cigarettes was significantly higher in CTC than control communities, but there was no statistically significant difference by intervention group in sustained abstinence or in cumulative incidence of other substances (Tables 1 and 2). Youth in CTC communities were also significantly more likely than youth in control communities to avoid ever engaging in delinquent (Table 1) or violent behavior (Table 2) through the spring of 12th grade.

Table 1.

Sustained Abstinence from Substance Use and Delinquency through Spring of Grade 12 among Baseline Non-Initiators comparing CTC and Control Communities

| Non-Initiators at Baseline (Grade 5) |

Cumulative Abstinence by Grade 12 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTC | Control | CTC | Control | ARR | (95% CI) | |

| Any drugs | 72.0% | 70.6% | 24.5% | 17.6% | 1.32 | (1.06;1.63) |

| Gateway drugs | 76.8% | 73.9% | 29.4% | 21.0% | 1.31 | (1.06;1.63) |

| Alcohol | 79.7% | 76.7% | 32.2% | 23.3% | 1.31 | (1.09;1.58) |

| Cigarettes | 92.6% | 90.5% | 49.9% | 42.8% | 1.13 | (1.01;1.27) |

| Marijuana | 99.6% | 99.3% | 52.6% | 48.2% | 1.07 | (0.96;1.19) |

| Binge drinking | 99.0% | 98.7% | 50.4% | 43.9% | 1.11 | (0.97;1.28) |

| Delinquency | 80.1% | 76.9% | 41.7% | 33.0% | 1.18 | (1.03;1.36) |

All figures represent averages across 40 imputed data sets. There were no significant baseline differences by intervention group. CTC = Communities That Care; CI = confidence interval.

ARR = adjusted risk ratio (for abstinence in CTC versus control group) adjusted for student and community characteristics. Bolded ARRs are statistically significant at p < .05 (2-tailed).

Table 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Substance Use and Violence by Grade 12 among Baseline Non-Initiators comparing CTC and Control Communities

| Non-Initiators at Baseline (Grade 5) |

Cumulative Incidence by Grade 12 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTC | Control | CTC | Control | ARR | (95% CI) | |

| Smokeless tobacco | 98.1% | 97.2% | 31.6% | 34.6% | 0.97 | (0.82;1.15) |

| Inhalants | 91.5% | 91.3% | 29.3% | 31.9% | 0.93 | (0.81;1.07) |

| Prescription drugsa | 98.6% | 98.4% | 29.4% | 29.3% | 0.98 | (0.85;1.13) |

| Ecstasy (MDMA)a | 98.6% | 98.4% | 13.5% | 12.0% | 1.18 | (0.86;1.63) |

| Cocainea | 98.6% | 98.4% | 9.6% | 11.2% | 0.94 | (0.73;1.21) |

| LSDa | 98.6% | 98.4% | 11.7% | 10.6% | 1.15 | (0.90;1.46) |

| Stimulantsa | 98.6% | 98.4% | 6.4% | 6.8% | 0.96 | (0.68;1.36) |

| Other illegal drugs | 98.6% | 98.4% | 25.3% | 25.4% | 1.07 | (0.89;1.29) |

| Violence | 92.2% | 88.9% | 34.4% | 41.1% | 0.86 | (0.76;0.98) |

All figures represent averages across 40 imputed data sets. There were no significant baseline differences by intervention group. CTC = Communities That Care; CI = confidence interval.

ARR = adjusted risk ratio (for incidence in CTC versus control group) adjusted for student and community characteristics. Bolded ARRs are statistically significant at p < .05 (2-tailed).

At baseline (5th grade), respondents were asked if they had used any other illegal drugs beyond marijuana and inhalants. They were not asked specifically about the use of prescription drugs, ecstasy, cocaine, LSD, and stimulants. Analyses of these specific drugs in 12th grade were conducted among baseline non-initiators of other illegal drugs.

Past-Month and Past-Year Prevalence

The proportion of students in control and CTC communities who used drugs in the past month or the past year did not differ significantly, with the exception of ecstasy use (Table 3). Students in CTC communities were almost twice as likely to use ecstasy in the past month as students in control communities. There were no significant differences by intervention group in past-year prevalence of delinquency and violence (Table 3) or the number of different delinquent behaviors (ARR=1.03; 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.19; p=.67) and the number of different violent acts (ARR=0.98; 95% CI: 0.78 to 1.22; p=.81).

Table 3.

Grade 12 Prevalence of Past-Month and Past-Year Substance Use, Delinquency, and Violence in CTC and Control Communities

| CTC | Control | ARR | (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past-month use | ||||

| Any drugs | 46.6% | 48.4% | 1.01 | (0.83;1.21) |

| Gateway drugs | 45.3% | 46.3% | 1.01 | (0.84;1.21) |

| Alcohol | 35.7% | 36.1% | 1.04 | (0.85;1.28) |

| Cigarettes | 22.7% | 24.3% | 0.94 | (0.76;1.15) |

| Marijuana | 21.9% | 19.7% | 1.09 | (0.93;1.28) |

| Smokeless tobacco | 8.8% | 10.8% | 0.83 | (0.66;1.06) |

| Inhalants | 1.5% | 1.1% | 1.37 | (0.73;2.57) |

| Prescription drugs | 7.3% | 5.1% | 1.44 | (0.98;2.12) |

| LSD | 2.2% | 1.5% | 1.41 | (0.81;2.45) |

| Cocaine | 1.4% | 1.0% | 1.52 | (0.77;2.99) |

| Stimulants | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.84 | (0.37;1.89) |

| Ecstasy (MDMA) | 2.6% | 1.4% | 1.89 | (1.09;3.27) |

| Other illegal drugs | 3.5% | 2.5% | 1.39 | (0.90;2.15) |

| Past 2 weeks | ||||

| Binge drinking | 17.3% | 19.7% | 0.94 | (0.72;1.23) |

| Past year | ||||

| Gateway drug use | 60.7% | 65.3% | 0.97 | (0.82;1.14) |

| Alcohol use | 55.6% | 59.2% | 0.99 | (0.83;1.18) |

| Cigarette smoking | 33.5% | 35.7% | 0.97 | (0.82;1.15) |

| Marijuana use | 34.2% | 33.7% | 0.99 | (0.87;1.12) |

| Delinquency | 28.7% | 29.8% | 1.02 | (0.90;1.17) |

| Violence | 10.4% | 11.6% | 0.97 | (0.77;1.21) |

All figures represent averages across 40 imputed data sets. There were no significant baseline differences by intervention group. CTC = Communities That Care; CI = confidence interval.

ARR = adjusted risk ratio (CTC versus control group) adjusted for student and community characteristics. Bolded ARRs are statistically significant at p < .05 (2-tailed).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study indicate that 8 years after implementation of CTC in communities and 3 years after study-provided technical assistance and resources ended, CTC continued to prevent initiation of alcohol and tobacco use, delinquency, and violence through 12th grade in a panel of students followed from grade 5. However, as implemented in this study, CTC did not produce reductions in levels of risk or the prevalence of current drug use or delinquent and violent behavior in grade 12.

Readers are reminded that communities chosen for this randomized trial of CTC were towns of 50 000 or fewer residents and do not include urban or suburban populations. Findings of this study may not generalize to larger communities. Another limitation is that the effect of CTC was evaluated in only 12 matched community pairs, which may have limited power to detect smaller intervention effects. However, the study detected substantively meaningful risk reductions or increases in abstinence between 12% and 32%. Youth in CTC communities were 32% more likely than youth in control communities to abstain from any drug use through 12th grade; they were 31% more likely to avoid ever using any of three gateway drugs (alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana). They were 18% more likely to have avoided delinquent behaviors and 14% less likely to have engaged in violence. Twelfth-graders in CTC communities also had a 31% higher probability than students in control communities of never having drunk alcohol and they were 12% more likely to have never smoked cigarettes. These effect sizes are similar to those found earlier when the panel was in 8th grade and when the benefit-cost ratio was estimated to be $5.30 per $1.00 invested in CTC based on the prevention of smoking and delinquency.42

Another possible threat to the internal validity of the study is that all analyses are based on self-report data, which carry the risk of social desirability bias or dishonesty. It is important to note that although this study was not a blinded trial, communities, not students, were randomized into intervention groups. It is highly unlikely that students in the longitudinal panel were aware to which intervention group their community belonged; and, thus, it is unlikely that there was differential self-report bias by intervention group that might account for any observed trial benefits. Further, we used validity checks to exclude a small number of students each year (<2% of the sample) deemed to have provided inaccurate reports of their behavior. This exclusion rate did not differ by intervention group. Additionally, the prevalence of substance use in this study is comparable to national data for the same cohort of 12th grader in the Monitoring the Future study. 43

The enduring effects of CTC through 12th grade were observed with little preventive programming targeting the high school years. Because CTC communities were asked to focus their prevention plans on programs for youths in grades 5 through 9, and continued to do so following study support, few students in the longitudinal panel were exposed to tested and effective programs beyond ninth grade. It is noteworthy that initiation of alcohol use, tobacco use, delinquency, and violence in the panel was prevented through 12th grade in CTC communities.

Targeting preventive interventions during middle school, a developmentally sensitive time for drug use and delinquency initiation, appears to have prevented the onset of alcohol and tobacco use, delinquency, and violence in the panel through high school. However, the present findings suggest that continued preventive interventions during high school may be needed to lower the current prevalence of substance use, delinquency, and violence among those who have initiated these behaviors. This suggestion is consistent with results of the randomized trial of Project Northland, a school and community approach to preventing adolescent alcohol use. Perry and colleagues9 found significant positive effects of Project Northland during the active intervention phase in middle school, but alcohol use grew faster among youth in intervention than in control communities in grades 9 and 10 when little programming took place. Positive effects in reducing alcohol use were found again, however, after preventive interventions were introduced in grades 11 and 12.

The higher prevalence of past-month use of ecstasy among 12th-grade students in CTC compared to control communities is the only significant negative effect associated with CTC observed in this panel. 18-20 This result should be interpreted with caution as the estimation of this intervention effect is based on small numbers of students reporting ecstasy use. In 11 of the 12 control communities and in 7 of the 12 CTC communities, no more than 4 students reported past-month ecstasy use in 12th grade. When community pairs were compared, the prevalence of past-month ecstasy use was higher in the CTC than the control community in 8 of 12 pairs and lower in the CTC than the control community in 4 pairs. In the absence of specific hypotheses or other evidence that would explain a negative intervention effect, it is unclear whether the higher prevalence of ecstasy use in grade 12 in CTC communities is an iatrogenic effect attributable to the intervention.

CONCLUSION

Sustained effects of CTC on preventing the initiation of alcohol use, tobacco use, delinquency, and violence through 12th grade are important. These effects were sustained with little preventive programming targeted at high school students during a period in which communities experienced economic stress likely to threaten prevention efforts.44 Lack of a developmental focus on preventive intervention during the high school years may explain why CTC communities did not reduce current levels of targeted risk factors or the current prevalence of drug use, delinquency, or violence in the panel in grade 12. It is possible that communities using the CTC system could affect these behaviors if they expanded the use of tested and effective preventive interventions developmentally through the high school years, though research is needed to confirm this suggestion.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding/Support: This work was supported by a research grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA015183-03), with co-funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, or preparation of data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: J. David Hawkins had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Additional Contributions: David M. Murray (Ph.D., Ohio State University) provided paid statistical consultation on this project, but the authors are responsible for all analyses and results. We thank Tanya Williams for her editorial help. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the communities participating in the Community Youth Development Study and the collaborating state offices of drug abuse prevention in Colorado, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Oregon, Utah, and Washington.

Study concept and design: Hawkins, Oesterle, Brown, Catalano, Abbott

Acquisition of data: Hawkins, Catalano

Analysis and interpretation of data: Oesterle, Brown, Hawkins, Abbott

Drafting of the manuscript: Oesterle, Hawkins

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Hawkins, Oesterle, Brown, Catalano, Abbott

Statistical analysis: Oesterle, Brown

Obtained funding: Hawkins, Catalano

Administrative, technical, or material support: Hawkins, Oesterle

Study supervision: Hawkins, Catalano

Financial Disclosure: Richard F. Catalano is a board member of Channing Bete Company, distributor of Supporting School Success® and Guiding Good Choices®. These programs were used in some communities in the study that produced the dataset used in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020 Adolescent Health Objectives. [March 3, 2011];Healthy People 2020. 2011 http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=2.

- 2.U. S. Department of Health and Human Services . The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; Washington, DC: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Communities That Care: Action for Drug Abuse Prevention. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2011;9(1):36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, et al. Testing Communities That Care: The rationale, design and behavioral baseline equivalence of the Community Youth Development Study. Prev Sci. 2008;9(3):178–190. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pentz MA, Dwyer JH, MacKinnon DP, et al. A multi-community trial for primary prevention of adolescent drug abuse: Effects on drug use prevalence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261(22):3259–3266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pentz MA, Trebow EA, Hansen WB, MacKinnon DP. Effects of program implementation on adolescent drug use behavior: The Midwestern Prevention Project (MPP). Eval Rev. 1990 Jun;14(3):264–289. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou CP, Montgomery S, Pentz MA, et al. Effects of a community-based prevention program in decreasing drug use in high-risk adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(6):944–948. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry C, Williams CL, Komro KA, et al. Project Northland: Long-term outcomes of community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(1):117–132. doi: 10.1093/her/17.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagenaar AC, Gehan JP, Jones-Webb R, et al. Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol: Lessons and results from a 15-community randomized trial. J Comm Psychol. 1999;27(3):315–326. 05. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grube JW. Preventing sales of alcohol to minors: results from a community trial. Addiction. 1997 Jun;92(Suppl. 2):S251–S260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holder HD, Gruenewald PJ, Ponicki WR, et al. Effect of community-based interventions on high-risk drinking and alcohol-related injuries. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(18):2341–2347. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg M, Clair S, Feinberg M. Substance-use outcomes at 18 months past baseline: The PROSPER community-university partnership trial. Am J Prev Med. 2007 May;32(5):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown EC, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW, Briney JS, Abbott RD. Effects of Communities That Care on prevention services systems: Outcomes from the Community Youth Development Study at 1.5 years. Prev Sci. 2007;8(3):180–191. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown EC, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW, Briney JS, Fagan AA. Prevention service system transformation using Communities That Care. J Comm Psychol. 2011;39(2):183–201. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhew IC, Brown EC, Hawkins JD, Briney JS. Sustained effects of the Communities That Care system on prevention service system transformation. Am J Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300567. Advance online publication. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300567:e1-e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagan AA, Arthur MW, Hanson K, Briney JS, Hawkins JD. Effects of Communities That Care on the adoption and implementation fidelity of evidence-based prevention programs in communities: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci. 2011;12(3):223–234. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0226-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkins JD, Brown EC, Oesterle S, Arthur MW, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Early effects of Communities That Care on targeted risks and initiation of delinquent behavior and substance use. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins JD, Oesterle S, Brown EC, et al. Results of a type 2 translational research trial to prevent adolescent drug use and delinquency: A test of Communities That Care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009 Sep;163(9):789–798. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins JD, Oesterle S, Brown EC, et al. Sustained decreases in risk exposure and youth problem behaviors after installation of the Communities That Care prevention system in a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(2):141–148. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gloppen KM, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Shapiro VB. Sustainability of the Communities That Care prevention system by coalitions participating in the Community Youth Development Study. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arthur MW, Gloppen KM, Hawkins JD. Sustainability of the Communities That Care prevention system.. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC. May 30, 2012; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown EC, Graham JW, Hawkins JD, et al. Design and analysis of the Community Youth Development Study longitudinal cohort sample. Eval Rev. 2009;33(4):311–334. doi: 10.1177/0193841X09337356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Pollard JA, Catalano RF, Baglioni AJ., Jr. Measuring risk and protective factors for substance use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors: The Communities That Care Youth Survey. Eval Rev. 2002;26(6):575–601. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0202600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glaser RR, Van Horn ML, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Measurement properties of the Communities That Care® Youth Survey across demographic groups. J Quant Criminol. 2005;21(1):73–102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Social Development Research Group . Community Youth Development Study, Youth Development Survey [Grades 5 - 12] Social Development Research Group, School of Social Work, University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2005-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arthur MW, Briney JS, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Brooke-Weiss BL, Catalano RF. Measuring risk and protection in communities using the Communities That Care Youth Survey. Eval Program Plann. 2007;30(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briney JS, Brown EC, Hawkins JD, Arthur MW. Predictive validity of established cut points for risk and protective factor scales from the Communities That Care Youth Survey. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2012;33(5-6):249–258. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0280-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham JW, Hofer SM. Multiple imputation in multivariate research. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multi-group data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 2000. pp. 201–218.pp. 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol Meth. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schafer JL. NORM for Windows 95/98/NT Version 2.03. Center for the Study and Prevention through Innovative Methodology at Pennsylvania State University; University Park, PA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, Cumsille PE. Planned missing data designs in psychological research. Psychol Meth. 2006;11(4):323–343. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schafer JL, Kang J. Average causal effects from nonrandomized studies: A practical guide and simulated example. Psychol Meth. 2008;13(4):279–313. doi: 10.1037/a0014268. 2008/12// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breslow N, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cummings P. Methods for estimating adjusted risk ratios. Stata Journal. 2009;9(2):175–196. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Localio AR, Margolis DJ, Berlin JA. Relative risks and confidence intervals were easily computed indirectly from multivariable logistic regression. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(9):874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon RT, Jr., du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert P. Models for longitudinal data: A likelihood approach. Biometrika. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuklinski MR, Briney JS, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Cost-benefit analysis of Communities That Care outcomes at eighth grade. Prev Sci. 2012;13(2):150–161. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0259-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use; Overview of key findings. 2011. National institue on Drug Abuse; Betheda, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuklinski MR, Hawkins JD, Plotnick RD, Abbott RD, Reid CK. How has the economic downturn affected communities and implementation of science-based prevention in the randomized trial of Communities That Care? Am J Comm Psychol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9557-z. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.