SUMMARY

In order for stressed cells to induce the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, a cohort of pro-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins must collaborate with the outer mitochondrial membrane to permeabilize it. BAK and BAX are the two pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family members that are required for mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. While biochemical and structural insights of BAK/BAX function have expanded in the recent years, very little is known about the role of the outer mitochondrial membrane in regulating BAK/BAX activity. In this review, we will highlight the impact of mitochondrial composition (both protein and lipid), and mitochondrial interactions with cellular organelles, on BAK/BAX function and cellular commitment to apoptosis. A better understanding of how BAK/BAX and mitochondrial biology are mechanistically linked will likely reveal novel insights into homeostatic and pathological mechanisms associated with apoptosis.

Keywords: apoptosis, BAX, BAK, BCL-2 family, cardiolipin, endoplasmic reticulum, lipids, mitochondria, sphingolipids

INTRODUCTION

“I kissed thee ere I killed thee. No way but this, Killing myself, to die upon a kiss.”

—William Shakespeare (1564–1616) Othello

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically controlled mechanism of removing stressed or unnecessary cells within multi-cellular organisms. Apoptosis is the most common form of PCD; and apoptotic mechanisms are divided into two major pathways.

The “extrinsic pathway” is induced by extracellular death ligands and cognate death receptors (e.g., TNF-α); and the “intrinsic pathway”, which responds to intracellular stress signaling (e.g., macromolecular damage), is mediated by mitochondria.

Throughout the past two decades, significant research efforts have focused on understanding the mechanistic contribution of mitochondria to the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Kerr, Willie, and Curie published a groundbreaking observation in 1972, which identified the morphological features of PCD and introduced the concept of “apoptosis.” One of the observations within that manuscript was that mitochondria remain intact during the early stages of apoptosis --- therefore, how do mitochondria communicate a signal to induce cell death (Kerr et al., 1972)?

In 1990, the anti-apoptotic function of the oncogene B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) was shown to rely on mitochondrial localization (Hockenbery et al., 1990, 1993); and soon after, cytochrome c release was identified as the mitochondrial signal required for apoptosis (Liu et al., 1996; Kluck et al., 1997; Manon et al., 1997). It is now well established that the BCL-2 family of proteins primarily regulate the release of mitochondrial inter-membrane space (IMS) proteins that activate the cell death proteases called caspases. These proteases are responsible for many of the apoptotic hallmarks first identified by Kerr et al., including nuclear condensation and cellular contraction. In addition to cytochrome c, two other IMS proteins that directly contribute to the initiation phases of apoptosis are second mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases (SMAC) (Du et al., 2000; Verhagen et al., 2000) and Omi/HtrA2 (Srinivasula et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2003). The release of these pro-apoptotic factors from the IMS requires a loss of outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) integrity, which is directly initiated by the pro-apoptotic members of the BCL-2 family in a process termed mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization or “MOMP”. Through MOMP, the pro-apoptotic IMS proteins re-localize to the cytosol to initiate caspase activation, and this process generates the mitochondrial signal required for the intrinsic pathway to proceed.

Here we will present a current interpretation of how the BCL-2 family functions, and how the pro-apoptotic BCL-2 members collaborate to induce MOMP (Figure 1). Importantly, we will discuss BCL-2 family function and MOMP within the context of both mitochondrial composition and biology for two key reasons: (1) pro-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins functionalize at the OMM to promote MOMP; and (2) recent evidence supports a novel role for both mitochondrial proteins and lipids in the regulation of MOMP. The second reason is of significant interest as it suggests that mitochondria play an active role in the recruitment and activation of the pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family members by regulating the proteins and lipids at the OMM. In addition, the notion that specific lipids and lipid metabolic pathways directly regulate mitochondrial sensitivity to pro-apoptotic BCL-2 members reveals that heterotypic membrane interactions and lipid trafficking pathways may play novel roles in cell death regulation.

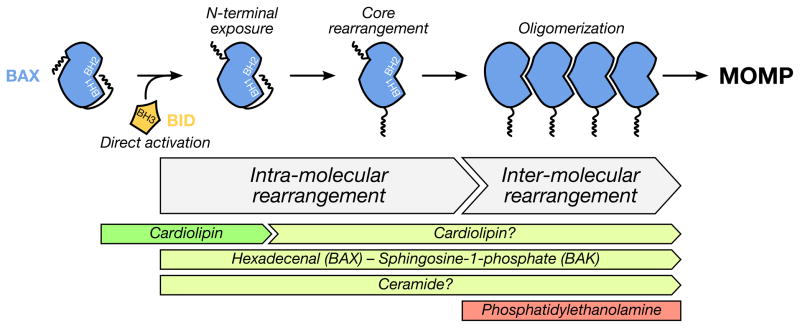

Figure 1. Mechanisms of BAK/BAX activation within the BCL-2 family.

Pro-apoptotic effectors (e.g., BAX, in blue) require multiple conformational changes to induce MOMP. Activation-associated BAK/BAX conformational changes are induced by interactions with direct activator BH3-only proteins (e.g., BIM, in yellow). These conformational changes are: exposure of the N-terminus, exposure of the α9 helix revealing the BH3 domain and, in some cases, homo-dimerization. Subsequently, multimerization of these dimers leads to pore formation and apoptosis. Anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., BCL-2, in red) prevent MOMP in two ways: (1) anti-apoptotic proteins actively sequester pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins; and (2) anti-apoptotic proteins bind to the exposed BH3 domain of BAK and BAX to prevent dimerization and oligomerization. Sensitization is when BH3-only proteins (e.g., BIM, in yellow) are binding anti-apoptotic proteins, preventing the future inhibition of pro-apoptotic proteins. De-repression is when a BH3-only protein (e.g., BAD, in green) releases activated BAK/BAX monomers and/or direct activator proteins, from anti-apoptotic proteins, leading to MOMP.

The BCL-2 family: regulators of outer mitochondrial membrane integrity

The BCL-2 family is divided into three groups based on structural and functional homologies. The proteins are composed mostly of alpha (α) helices and share up to four homology domains termed BCL-2 homology (BH) domains. Most multi-domain members (i.e., those with two or more BH domains, for example BCL-2) and BID (a BH3-only member, described below) possess a similar tridimensional structure (Yan and Shi, 2005), whereas the remaining BH3-only proteins are intrinsically unstructured in solution and fold upon interactions with multi-domain members (Hinds et al., 2007; Petros et al., 2000).

The anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins are responsible for maintaining the integrity of the OMM. They are globular proteins that contain BH domains 1–4. The members of this subfamily include A-1 (BCL-2 related gene A1), BCL-2, BCL-xL (BCL-2 related gene, long isoform), BCL-w, and MCL-1 (myeloid cell leukemia 1). These proteins are generally found at the OMM, but can also be localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane and in the cytosol. The anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins preserve OMM integrity by directly binding to both classes of pro-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins (i.e., the BH3-only and effector proteins), which prevents them from cooperating to induce MOMP and subsequent apoptosis. The anti-apoptotic members share a conserved ‘BCL-2 core’ structure comprised of six α helices that results in the formation of a hydrophobic groove. Although the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins demonstrate conserved sequence and/or structural homologies, slight variations within this groove afford unique binding profiles between the anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic proteins.

The pro-apoptotic multi-domain proteins BAK (BCL-2 Antagonist Killer 1) and BAX (BCL-2 Associated X protein) are the effectors of MOMP as they insert into the OMM and induce the formation of pores allowing for the release of IMS proteins (Liu et al., 1996; Kluck et al., 1997) (Figure 1). In order for BAK or BAX to induce MOMP, these proteins must be localized to the OMM and activated by a BH3-only protein. For BAK, the mechanism of activation is more straightforward, as the protein is constitutively inserted in the OMM by its α9 helix (Moldoveanu et al., 2006). In contrast, BAX activation requires additional steps as this protein is generally cytosolic and must interact with the OMM to undergo activation (Hsu et al., 1997; Wolter et al., 1997) and trigger MOMP (Manon et al., 1997; Jürgensmeier et al., 1998). Upon activation by BH3-only proteins (Kuwana et al., 2002; Gavathiotis et al., 2008; Lovell et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009), physico-chemical changes (Khaled et al., 2001; Cartron et al., 2004), or in vitro interactions with hydrophobic molecules (e.g., detergents or fatty aldehydes), BAX and BAK undergo multiple conformational changes including: the exposure of the α1 helix (Cartron et al., 2005; Peyerl et al., 2007), the α9 helix (Gavathiotis et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009; Czabotar et al., 2013), and the BH3 domain (Cartron et al., 2005), insertion of their α5–6 helices in the OMM (Annis et al., 2005; García-Sáez et al., 2006), dimerization, and higher order oligomerization (Eskes et al., 2000; Antonsson et al., 2001). Once activated, the oligomerized forms of BAK and BAX form proteolipid pores within the OMM, and these pores are large enough for the majority of soluble IMS proteins escape into the cytosol.

The third subgroup is comprised of proteins in which homology to the BCL-2 family is restricted to the BH3 domain, and these members are commonly referred to as “BH3-only proteins”. These function by directly associating with both the anti-apoptotic and effector proteins; and this leads to two distinct mechanisms of action for the BH3-only members (Figure 1). First, all BH3-only proteins have the ability to bind anti-apoptotic proteins with relative binding specificities, which either neutralizes anti-apoptotic function to decrease cellular sensitivity to MOMP (e.g., BAD), or releases previously sequestered BH3-only proteins to directly induce MOMP (e.g., PUMA) (Kuwana et al., 2005; Letai et al., 2004). In the latter statement, the second mechanism of BH3-only protein function is revealed, which is a subgroup of BH3-only proteins can act as direct activators to BAK and BAX to induce their oligomerization and pore forming activity; for example, BID (Desagher et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2000) and BIM (Gavathiotis et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009).

As described above, the BCL-2 family participates in MOMP by controlling the formation of pores in the OMM (Figure 2). However, the interplay between the BCL-2 family and mitochondria is not limited to the intrinsic pathway. Numerous BCL-2 family members play an active role in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics, and subsequently, mitochondrial metabolism in healthy cells. Mitochondrial fusion is regulated by BCL-xL through the interaction with a large GTPase in the OMM, Mitofusin-2 (Mfn2) (Delivani et al., 2006). Similarly, BAK and BAX also enhance mitochondrial fusion in non-apoptotic (Hoppins et al., 2011; Karbowski et al., 2006) and apoptotic cells (Brooks et al., 2007), by interaction with Mfn-2 (Hoppins et al., 2011). These observations suggest that mitochondria are not a passive target of the BCL-2 family, but that a broader cooperation exists. As such, a role for BCL-2 proteins in autophagy is also well documented, and the process of autophagy directly impacts on organelle turnover and cellular metabolism (Levine et al., 2008).

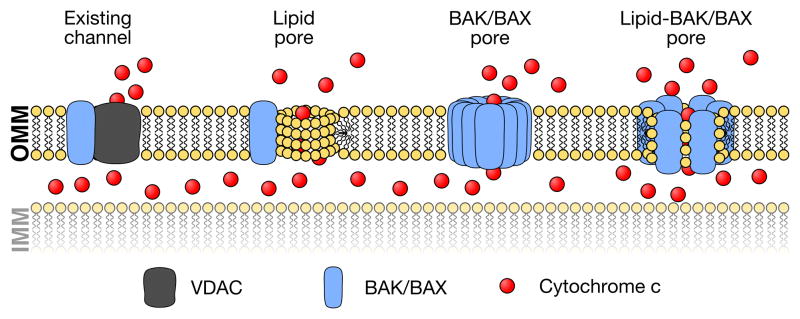

Figure 2. Competing models of pore formation during apoptosis.

In the literature, there are several models describing the composition of the pore responsible for cytochrome c release. Early models of apoptosis suggested that BAK and BAX can positively influence proteinaceous or lipidic pore formation. For example, it has been shown that BAX increases the permeability of VDAC1 function in the OMM; alternatively, BAK/BAX may cooperate with ceramide channels. On the other hand, biochemical studies have shown that BAK and BAK directly promote pore formation in the absence of additional proteins. More recently, accumulating evidence suggests that BAK/BAX and mitochondrial lipids cooperate to promote BAK/BAX activation and pore formation.

Throughout our discuss so far, we have focused on the function of BCL-2 protein to regulate apoptosis, but little attention has been paid to understanding how mitochondria impact on the BCL-2 family to induce MOMP. Are mitochondria passive organelles in the process --- or --- do they regulate their own permeabilization by creating an environment that is permissive for pro-apoptotic BCL-2 members to engage MOMP? We will directly address these questions in the following sections.

The outer mitochondrial membrane: a unique platform for BCL-2 family function

Nearly all the multi-domain members of the BCL-2 family are localized to the OMM, but there are instances of cytosolic and inner mitochondrial membrane localizations, such as BAX and MCL-1, respectively (Hsu et al., 1997; Perciavalle et al., 2012). The mitochondrial localization of the BCL-2 proteins is favored by a combination of α-helical bundles that comprise the core structural components of the folded members, a carboxyl terminus transmembrane domain, hydrophobic patches of the proteins, and post-translational modifications that promote protein-membrane interactions (e.g., N-myristoylation of BID) (Zha et al., 2000).

One of the intriguing questions about the BCL-2 family of proteins is what dictates their predilection for the OMM? Unlike most of mitochondrial proteins, BCL-2 family members do not possess a well-defined mitochondrial targeting sequence. The presence of several positively charged residues in the transmembrane helix of BCL-xL favors its mitochondrial localization, however this is not the case for BCL-2 (Kaufmann et al., 2003). As the majority of BCL-2 family members do not have a carboxyl terminus with multiple positively charged amino acid residues, it is unlikely that such a signal dictates the targeting to the OMM. More likely, BCL-2 family localization and function are favored by the environment of the OMM itself via a combination of mitochondrial proteins and lipids.

Indeed, most of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members are localized to the OMM via a carboxyl terminus transmembrane domain. This serves as an efficient docking element for regulating pro-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins, which bind to anti-apoptotic members via their BH3 domain. It is likely that most BH3-only proteins localize to the OMM by direct associations with the anti-apoptotic repertoire. One exception is BID, which appears to directly bind membranes in order to reveal its BH3 domain and induce apoptosis. However, neither protein nor membrane interactions exclude subsequent exchanges; more specifically, if BID is first bound to a membrane, this could serve as an efficient mechanism to eventually position BID into the hydrophobic groove of a pro- or an anti-apoptotic BCL-2 member.

Furthermore, there are several proteins that serve as ‘receptors’ to promote the mitochondrial localization of BCL-2 family members, including multiple components of the mitochondrial import machinery (i.e., the TOM complex) and the mitochondrial carrier protein MTCH2, both of which have been suggested to play a role in the incorporation of the BCL-2 proteins into the OMM (Zaltsman et al., 2010). Significant efforts have focused on understanding how BAX is recruited to the OMM to promote apoptosis. As mentioned earlier, BAX is dynamically associated with the mitochondrial membrane in healthy cells (Hsu et al., 1997). Several studies recently suggested that mitochondrial BAX in non-apoptotic cells results from a translocation/retro-translocation to and from the mitochondria (Edlich et al., 2011; Renault et al., 2013; Schellenberg et al., 2013). Multiple members of the BCL-2 family have been shown to modulate BAX mitochondrial localization. For example, BCL-2, BCL-xL, and MCL-1 increased both BAX translocation to (Renault et al., 2013; Schellenberg et al., 2013) and retro-translocation from (Edlich et al., 2011; Schellenberg et al., 2013) the OMM. Upon triggering of apoptosis, BH3-only proteins (e.g., BID and BIM) can stimulate the mitochondrial localization of BAX, and accumulation into the OMM (Hsu et al., 1997; Kuwana et al., 2002). After BAX is at the OMM, additional protein may serve to promote activation, such as the mitochondrial division protein DRP-1 that stimulates BAX oligomerization through the remodeling of the OMM (Montessuit et al., 2010).

As we have alluded to throughout our discussion, BCL-2 family members function in the context of mitochondrial membranes, and the proteins involved in localizing the BCL-2 family to the OMM are either constitutively membrane bound and/or regulate the OMM directly. Therefore, we propose that the lipid environment has at least two key roles in regulating cellular sensitivity to apoptosis: (1) anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic proteins likely have a specific lipid requirement to efficiently interact to either promote cellular survival or engage apoptosis; and (2) in order for the above interactions to take place, the membrane environment must be able to localize and/or deliver BCL-2 proteins to the OMM. Below, we will discuss these two key roles of the OMM.

BAK and BAX disrupt lipid membranes to induce MOMP

After the discovery of the nearly twenty BCL-2 family members, and the identification of anti- and pro-apoptotic phenotypes associated with each member, significant effort focused on understanding how the multiple members of the pro-apoptotic subfamilies collaborated to induce MOMP. One of the major advances in the field stemmed from a paper by Kuwana et al., that shows BAX, BID, and mitochondrial lipids cooperate to permeabilize membranes. The authors determined the lipid composition of mitochondrial membranes, and then established a biochemically-defined, protein-free large unilamellar vesicle model system that mimics the composition of the OMM. The OMM is comprised of several ubiquitous lipids, including phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, and phosphatidylserine; along with small amounts of phosphatidic acid and a debatable level of cardiolipin (n.b., we will discuss cardiolipin in the next section). That said, BAX-dependent permeabilization of these “mitochondrial LUVs” required a high percentage of cardiolipin. Similar requirements for BAK have not been formally tested, but BAK also works in LUV systems similar to those described above (Kuwana et al., 2002; Du et al., 2011; Leshchiner et al., 2013).

Given the abilities of BAK and BAX to activate, oligomerize, and permeabilize in the OMM independently of mitochondria proteins, it was further hypothesized that BAK and BAX are sufficient to form a proteinaceous pore. Kinetic analysis suggested that the BAX pore assembles progressively, and is formed by nine to twelve BAX monomers that would correspond to a size of about 6 nm (Martinez-Caballero et al., 2009). Larger BAX and BAK oligomers (between 100 and 2×104 BAX) have also been identified in vitro (Nechushtan et al., 2001; Zhou and Chang, 2008), but physiological requirements for such large pores have not been demonstrated.

In parallel, one additional important detail is that BAX can destabilize lipid bilayers at very low concentrations (Basañez et al., 1999), suggesting that membrane permeabilization may not be exclusively due to the formation of a proteinaceous pore, but there may be contributions of the lipid reorganization within the membrane that cause MOMP. This model suggests that lipids rearrange to form a toroidal structure involving a local fusion of the two leaflets of the bilayer membrane and suggests that BAK and BAX would play a role in the organization and stabilization of the lipids. This idea was first supported by the observation that the lipid composition of the membrane was critical for the formation of a BAK/BAX channel. Indeed, in the toroidal model, lipids are subjected to non-planar constraints which is favored by the presence of lipids with a positive intrinsic curvature (e.g., lysophosphatidylcholine) and to a lesser extent, lipids with a negative intrinsic curvature (e.g., phosphatidylethanolamine). Both positively and negatively curved lipids have been shown to stimulate the BAX-mediated permeabilization of liposomes (Basañez et al., 2002; Terrones et al., 2004) via BAX α5 and α6 helices (García-Sáez et al., 2006). In contrast to β-barrel channels for which a structure can be determined by crystallization, it is very difficult to obtain structural information on α-helix structured pore-forming proteins. However, structural data was acquired using BAX α5 helix and further supported the model of a toroidal lipidic pore (Qian et al., 2008); and more recently structural interrogations of BAX dimers will surely lead us onto a path of a better understanding of the BAK and BAX pores (Czabotar et al., 2013).

Does cardiolipin regulate BAK/BAX-dependent MOMP?

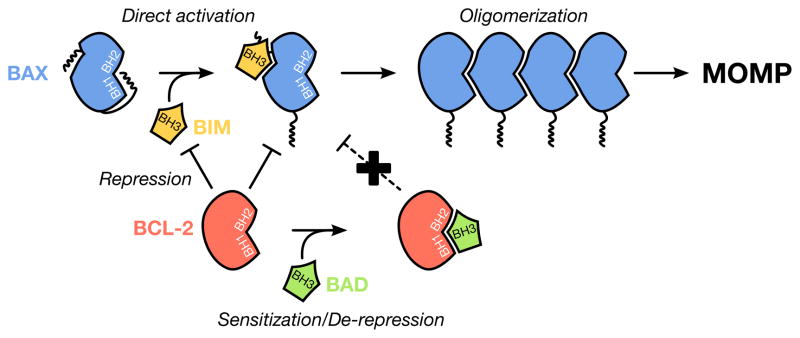

Cardiolipin (CL), or 1,3-bis-(sn-3′-phosphatidyl)-sn-glycerol, is one of the major lipids synthesized and localized in the IMM (~13%); and CL plays a key structural role in the junction sites between the IMM and OMM (Hoch, 1992; Zhang et al., 2011). CL also directly binds to cytochrome c at the IMM, and is therefore thought to be an important regulator of apoptosis (Iverson et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2007); likewise, a deficiency in CL facilitates cytochrome c release and apoptosis (Choi et al., 2007). As mentioned earlier, CL is required for BAX-induced permeabilization of mitochondrial LUVs (Kuwana et al., 2002; Terrones et al., 2004) (Figure 3). Interestingly, LUVs that resemble the lipid composition of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resist BAX-mediated permeabilization unless CL is added (Kuwana et al., 2002). However, deletion of CL synthase in yeast expressing human BAX has no effect on BAX insertion into the OMM and subsequent cytochrome c release (Iverson et al., 2004), which suggests that CL is not absolutely essential for BAX-dependent membrane permeabilization, or perhaps CL can be substituted with other factors (Du et al., 2011).

Figure 3. Mitochondrial lipids regulate BAK/BAX activation and MOMP.

BAK/BAX activation requires several conformational changes, including intra-molecular (N-terminus exposure, core conformational changes revealing the BH3 domain) and intermolecular (homo-dimerization and oligomerization) rearrangements. Several lipids are described to cooperate with BID, BAK and BAX. As a first example, cardiolipin favors BID interactions with BAK and BAX, which promotes intra-molecular conformational changes. Given the abundance of cardiolipin in the IMM and contact sites, additional roles for cardiolipin in BAK/BAX core rearrangements and oligomerization remain to be resolved. Additionally, sphingosine-1-phosphate and hexadecenal are demonstrated to participate in BAK and BAX activation, respectively. The exact step(s) of BAK/BAX activation controlled by these sphingolipid metabolites also remains to be defined. Little is known about the negative regulatory aspects of lipids on BAK and BAX activation, except for phosphatidylethanolamine which inhibits BAX oligomerization in vitro.

While the published literature describing a role for CL in BAX function at the OMM remains debated, additional roles for CL in BCL-2 family function have also been suggested. CL promotes BID translocation to liposomes (García-Sáez et al., 2009), to the OMM (Lutter et al., 2000), and to mitochondrial contact sites (Lutter et al., 2001). CL also assists in the recruitment and activation of caspase 8 to the OMM, which may function as an activation platform for BID cleavage (Gonzalvez et al., 2008). Within BID, there is a CL-binding domain that resides within amino acids 103–163 spanning α-helices 4, 5, and 6 (Lutter et al., 2000). This CL-binding domain is directly implicated in targeting BID to the OMM, as cells expressing a temperature sensitive mutant of CL synthase fail to properly localize exogenously expressed BID (Lutter et al., 2000).

BID localizes and activates at the OMM, but is there a role for CL on BID-induced MOMP after recruitment? (Figure 3) Perhaps the sole role of CL is to promote BID-induced BAX activation and membrane permeabilization? The answer is likely no, however, as additional reports suggest that BID can also have directly consequences on membrane integrity, lipid mixing between the IMM and OMM, and membrane curvature (Epand et al., 2002) --- all of which are directly impacted by the presence of CL and its metabolism. Furthermore, the role of CL likely extends beyond BID and BAX, as a truncated form of BAK directly binds CL resulting in heighted sensitivity to BID-induced BAK activation and membrane permeabilization (Landeta et al., 2011). As noted above, CL is described to affect BAK, BAX, and BID function, this begs the question: are anti-apoptotic BCL-2 members also regulated? There is currently no answer to this question.

Alternatively, a role for CL in BAK/BAX-dependent apoptosis can be debated for at least two reasons: (1) the CL concentration required for membrane permeabilization in vitro is below the physiological level observable in the OMM; and (2) in vitro activation of BAX and subsequent membrane permeabilization can occur in the absence of CL (Chipuk et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013). However, thorough biochemical and cellular studies using mammalian systems and endogenous components are necessary to generate conclusions. Furthermore, as BAK, BAX, BID, and CL likely regulate mitochondrial cristae junction organization during MOMP (Scorrano et al., 2002; Yamaguchi et al., 2008), which impacts upon cytochrome c accessibility to the cytosol, we may have to also explore alternative regulatory components to fully appreciate the potential dual role of CL in MOMP.

While CL synthesis occurs within mitochondria, numerous lipids found in the OMM originate from distinct cellular membranes. Mitochondria themselves biochemically and physically interact with a host of membrane structures, e.g., the ER, --- is it possible that these interactions regulate the composition of the OMM, which have immediate implications on pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family function? We will explore this question in the following section.

Contact sites between the ER and mitochondria: a regulator of BAK/BAX activation and cell death?

The ER network represents a significant proportion of a cell’s total membrane structure, and the ER interacts with multiple organelles via membrane-membrane contacts, along with proteinaceous tethers between the organelles (Elbaz and Schuldiner, 2011). Regarding a direct interaction between the ER and OMM, there are proteinaceous tethers that link the two membranes at a distance of approximately 10 - 20 nm, but the identity of these protein(s) remains controversial. The pro-fusion GTPase Mfn2 is suggested as an ER - mitochondrial tether, as its deletion results in marked changes in ER network morphology and a decrease in mitochondrial proximity (Brito and Scorrano, 2008). However, the effect of mfn2 deletion generates a phenotype in only 40% of mitochondria, suggesting multiple tethering proteins may exist. Indeed, a genetic screen searching for mitochondria/ER disruptions in yeast identified a tethering complex named ER-mitochondria encounter structure (ERMES), which is comprised of the ER protein Mmm1, and the mitochondrial proteins Mdm10/34 and Mdm12 (Kornmann et al., 2009). (Figure 4) But, what is the evidence that ER - mitochondrial contact regulates MOMP and apoptosis?

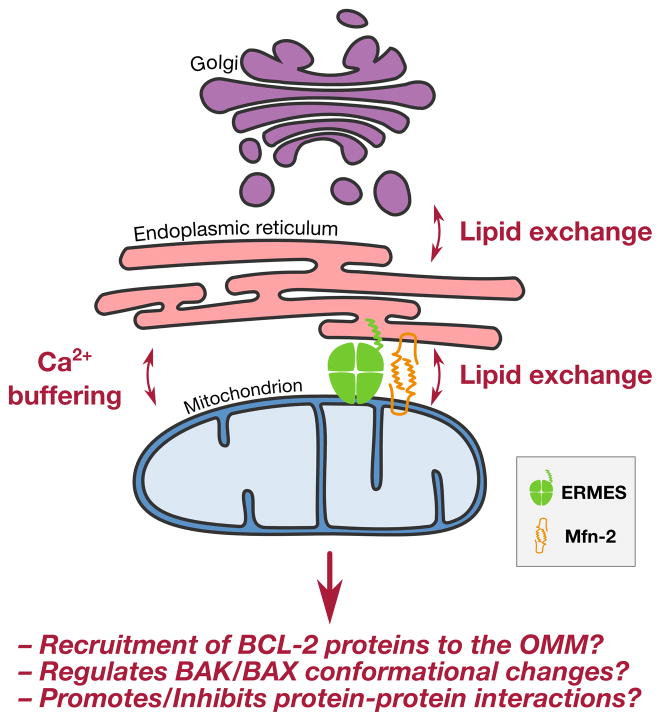

Figure 4. Inter-organellar communication influences mitochondrial lipid composition and MOMP.

As the permeabilization of the OMM is effected and affected by lipids, interactions between the OMM and other cellular membranes likely influence BAK/BAX activation and MOMP. For example, lipids originating at the Golgi complex and ER influence the composition of mitochondrial membranes (e.g., sphingomyelin, ceramide, phosphatidylserine). Likewise, this transfer increases the diversity of mitochondrial lipids as mitochondria themselves are able to further metabolize lipids which directly impact on BAK/BAX activation (e.g., sphingosine-1-phosphate, hexadecenal, phosphatidylethanolamine). Lipid transfer is likely assisted by a combination of shared membrane structures and proteinaceous tethers between the ER and mitochondria (e.g., the ERMES complex and Mfn-2 dimers). In addition to a role in lipid exchange, ER-mitochondria interactions also allow for calcium buffering between organelles which is known to modulate the sensitivity of mitochondria to the BCL-2 family.

To address this question, we must focus on the physiological roles of ER - mitochondrial communication. Mitochondria demonstrate excellent buffering capacity against calcium release from the ER, and when mitochondrial - ER tethering is increased by the introduction of recombinant tethers, there are impressive increases to mitochondrial calcium uptake that may directly influence cellular sensitivity to apoptosis by the recruitment of pro-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins (Csordás et al., 2006, 2010). Another function of ER - mitochondrial tethering is the regulation of phospholipid synthesis and translocation between the organelles as phosphatidylcholine (PC) synthesis requires crosstalk between ER and mitochondria. Phosphatidylserine (PS), a PC precursor, is synthesized in the ER network and must translocate to the mitochondrial IMS to be converted to phosphatidylethanolamine (Stone and Vance, 2000), which returns to the ER to be converted to PC. As evidence, deletion of critical components of the ERMES complex leads to changes in both mitochondrial morphology and collateral decreases in PS to PC conversion (Kornmann et al., 2009). There is limited information available on the role of phospholipids on BCL-2 family function, but one study revealed that the presence of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) does not effect BAX insertion into a membrane, but PE is inhibitory to BAX oligomerization. As with all membranes, a balance between each lipid species is essential for homeostasis, and we have little information on how disruptions to phospholipid levels directly impact on BAK/BAX function.

Another aspect of ER - mitochondrial communication that likely impacts on BAK/BAX function is the dual role of the mitochondrial dynamics machinery in tethering. As mentioned above, Mfn2 tethers the ER to the mitochondrial network. However in healthy cells, BAX also localizes to the sites of mitochondrial fusion, interacts with Mfn-2, and stimulates mitochondrial fusion (Karbowski et al., 2006). Mechanistically, the monomeric form of BAX promotes the homo-dimerization of Mfn2 to induce mitochondrial fusion (Hoppins et al., 2011); and these observations may also provide some insights for the observation that BAX localizes on the ER membrane (Scorrano et al., 2003; Zong et al., 2003). An additional function of ER - mitochondrial interactions may be the physical requirement for ER tubules to mark the mitochondrial network for sites of mitochondrial division, which is mediated by Drp1 assembly (Friedman et al., 2011). Likewise, there is a significant literature describing a role for Drp1 in mediating BAX localization and activation, along with mitochondrial membrane rearrangements, that are necessary to support MOMP.

One more role for ER - mitochondrial tethering may be to directly provide a source of cellular sphingolipids to the mitochondrial membranes (and vice versa). There is a substantial literature supporting a role for sphingolipids in regulating cellular sensitivity to BAK/BAX activation, but synthetic pathways and transport mechanisms for sphingolipids into the OMM require further study. The shuttling of ceramides between the ER and Golgi complex and other cellular organelles is mediated by CERT (ceramide transporter), GLTP (glycolipid transport protein), and saposins. While little is known regarding the flow of sphingolipids from heterotypic membranes to mitochondria, we will discuss the role of various sphingolipids in mediating BAK/BAX activation and apoptosis in the following section.

Sphingolipids: multiple intersections with the BCL-2 family

Sphingolipids are a complex and diverse set of lipids that are characterized by a sphingoid base linked to a fatty acid via an amide bond. These lipids are essential for cellular membrane structures and signal transduction. The role of these lipids in signaling ranges from survival pathways to the biochemical decision to induce cell death, and encompasses almost everything in between (e.g., autophagy, metabolism, signaling cascades, membrane trafficking, and organelle integrity). A discussion on all the possible roles of every sphingolipid in cell survival and cell death pathways is not possible here, but we will present three distinct topics that are directly linked to the BCL-2 family and pro-apoptotic signaling: (1) ceramides induce pore formation in the OMM that is regulated by the BCL-2 family; (2) the BCL-2 family regulates cellular sphingolipid composition following cellular stress; and (3) multiple sphingolipids cooperate with BAK and BAX to promote MOMP (Figure 3). In brief, these topics reveal that BCL-2 family function and multiple sphingolipid species collaborate to promote MOMP, but the molecular mechanisms behind these interactions and phenotypes remain mostly unknown.

Before the mechanisms of BCL-2 family regulated apoptosis were identified, early studies revealed that the addition of C2-ceramide (a cell-permeable synthetic analog of ceramide) to leukemic cells in vitro led to inter-nucleosomal DNA cleavage and apoptosis (Obeid et al., 1993). Similarly, cancer cell lines treated with TNF-α displayed increased sphingomyelin hydrolysis, ceramide accumulation, and subsequent apoptosis (Dressler et al., 1992; Obeid et al., 1993; Geilen et al., 1997). These observations suggested that ceramide itself was necessary and sufficient to induce apoptosis, and led to numerous studies showing that ceramide could form pores in lipid membranes, which was then implicated as a mediator of cytochrome c release in cells. Indeed, ceramide forms pores in planar membranes; and similar results can be obtained using isolated mitochondria suggesting that ceramide may be able to induce cytochrome c release directly (Siskind and Colombini, 2000; Siskind et al., 2002). Interestingly, several members of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family have been shown to modulate the pore-forming activity of ceramide. For instance, the anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 and BCL-xL, along with the C. elegans BCL-2 homologue CED-9, disassemble ceramide channels in isolated mitochondrial systems from rat and yeast (Siskind et al., 2008), potentially through direct interactions between ceramide and the anti-apoptotic protein (Perera et al., 2012). Conversely, BAX is described to synergize with various ceramides to permeabilize both planar membranes and isolated mitochondria. Despite BAX and ceramide possessing independent pore-forming functions, the combination of BAX and ceramide leads to an enhanced permeabilization (Ganesan et al., 2010). However, it remains unknown if BAX stabilizes the formation of ceramide pores, or if ceramide promotes BAX insertion and oligomerization; potentially, the two mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. However, the use of a mitochondrially-targeted analog of ceramide (C6-pyridinium) demonstrated a positive role for ceramide on BAX-induced MOMP and apoptosis in the absence of BID suggesting that perhaps ceramide specifically promotes BAX function (Hou et al., 2011).

In cells, it is difficult to directly determine the effects of sphingolipids on individual BCL-2 proteins because of the multiple roles these lipids play in cellular homeostasis and the exquisite compensatory mechanisms that are activated when the metabolism of one sphingolipid species is altered. However, an interesting set of observations revealed that the subcellular location of ceramide generation has differential effects on apoptosis. The pro-apoptotic contributions of ceramide generation in different cellular compartments was determined by targeting a bacterial neutral sphingomyelinase to various organelles and revealed that ceramide-induced apoptosis relies on mitochondrial ceramide (Birbes et al., 2001). Interestingly, apoptosis induced by mitochondrial ceramide is dependent upon BAX recruitment to mitochondria, cytochrome c release, and is inhibited by the over-expression of BCL-2 (Birbes et al., 2001, 2005). Moreover, multiple stressors (e.g., DNA damage, cytokines) induce cellular ceramide generation through numerous pathways (Cifone et al., 1994; Takeda et al., 1999; Caricchio et al., 2002; Clarke et al., 2011), which is directly implicated in organizing a mitochondrial ceramide-rich macrodomains (MCRM), which supports BAX recruitment and oligomerization in the OMM (Lee et al., 2011). The requirement for ceramide in DNA damage-induced apoptosis is also evolutionally conserved as the genetic disruption of ceramide synthase in C. elegans reduces apoptotic responses by inhibiting the BH3-only protein EGL-1 (Deng et al., 2008).

Not only do stress signals regulate ceramide generation, but also several reports suggest that BCL-2 proteins themselves are directly involved in ceramide generation. Epigenetic regulation of BAK revealed that irradiation-induced generation of distinct ceramide pools was dependent upon BAK expression (Mullen et al., 2011). Moreover, the inhibition of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins with ABT-263, a BH3-only protein mimetic, led to BAK-dependent activation of ceramide synthase that was inhibited by MCL-1 (Beverly et al., 2013). Is BAK-dependent regulation of ceramide production contributing to cell death? Within Beverly et al., the authors suggest that the activated conformation of BAK promotes ceramide generation, and this phenotype is independent of BAX. The physiological role of ABT-263 induced, BAK-dependent ceramide generation remains speculation. However, do BH3-only proteins also elicit the same mitochondrial response? Is ceramide generation dependent upon activated monomers of BAK or BAK dimers/oligomers? Also, does mitochondrial generation of ceramide directly alter the lipid environment of the OMM to impact upon cellular sensitivity to pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family function?

Ceramide generation is considered an important node in sphingolipid metabolism as ceramide can be reversibly converted into numerous lipid species, and most of these lipids influence cellular sensitivity to apoptosis by direct or indirect mechanisms. Here, we will discuss recent developments on sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and its metabolic product hexadecenal. We should mention that the extracellular role of S1P involves binding to cell surface receptors which transduce anti-apoptotic signals via transcriptional and post-translational effects on the BCL-2 family (Limaye et al., 2005; Colié et al., 2009). This role is not discussed here, as our focus is restricted to the direct intracellular effects of S1P and hexadecenal on the BCL-2 family. Indeed, a growing body of evidence suggests that intracellular S1P has direct effects on cell death pathways. For example, the injection of ethanol into neonatal mice results in marked increases in intracellular S1P, which is correlated with sphingosine kinase 2 (SK2) activation, and apoptosis (Chakraborty et al., 2012). Curiously, SK2 is localized to mitochondria and may directly regulate apoptosis through both S1P generation and via a putative BH3 domain (Liu et al., 2003).

The direct relationships between S1P metabolism and BAK/BAX activation were elucidated by the demonstration that S1P and hexadecenal promote BAK and BAX activation, respectively (Chipuk et al., 2012). In this study, purified mitochondria devoid of contaminating membrane species (e.g., ER) resisted BID-induced BAK/BAX-dependent cytochrome c release; and re-sensitization to BAK/BAX activation was achieved by adding S1P and hexadecenal, respectively. Furthermore, hexadecenal can directly bind BAX to promote conformational changes associated with activation, oligomerization, and pore formation in mitochondria and LUVs (Chipuk et al., 2012). Indeed, a role for hexadecenal in apoptosis has been suggested throughout the literature. S1P lyase (SPL), the enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of S1P to hexadecenal, sensitizes to p53-mediated apoptosis (Oskouian et al., 2006). Hexadecenal also causes cytoskeletal reorganization and triggers the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis via BID and BIM activation, and BAX-dependent cytochrome c release (Kumar et al., 2011a). A relationship between SPL and DNA damage is also characterized by cell cycle arrest, depletion of S1P, and apoptosis (Kumar et al., 2011b).

PERSPECTIVES

Returning to one of our initial questions: how do mitochondria communicate a signal to induce cell death? Observations accumulated throughout the past twenty years suggest that BAK/BAX-dependent MOMP is the key event leading to the initiation of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. In order for MOMP to proceed, monomeric forms of BAK and BAX undergo activation at the OMM, and this occurs via interactions with the direct activator BH3-only proteins. Indeed, the OMM is permeabilized following the activation of BAK/BAX, but evidence provided here points to a more active role of mitochondria in dictating whether or not BAK/BAX can localize, activate, oligomerize, and permeabilize mitochondria.

Mitochondrial contributions to BAK/BAX activation likely include a combination of both passive and active mechanisms. For example, several OMM proteins (i.e., TOM, MTCH2) are implicated in localizing BAK/BAX to mitochondria; however, whether or not MTCH2 and TOM are actively regulated during cell death signaling remains to be determined. Likewise, how are the non-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic roles of MTCH2 and TOM balanced to preserve survival and/or promote death?

The mechanistic contributions of lipids (including mitochondria-specific, i.e., CL; and ubiquitous, e.g., PE) to BAK/BAX activation and cellular sensitivity to apoptosis remain an outstanding question. The requirement for CL in certain systems may suggest that distinct apoptotic pathways or BCL-2 family complexes differentially require CL-mediated BAK/BAX activation and oligomerization. Are there pro-survival or pro-apoptotic signaling events that directly influence the composition of the OMM to dictate cellular responses? This situation is further complicated by a significant literature describing multiple lipid species (e.g., ceramide, S1P) have diverse outcomes on both anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family function (Maceyka et al., 2005; Mullen and Obeid, 2012). The answers to many of these questions will likely result from biochemical and cellular experiments that reveal all the potential cellular interactions between mitochondria and additional membrane compartments that directly influence both the lipid and protein composition of mitochondrial membranes. Detailed structural analyses are also required to better understand how lipids directly interact with pro-apoptotic members of the BCL-2 family. Furthermore, as multiple members of the mitochondrial dynamics machinery influence membrane structure by tethering mitochondria to themselves and other organelles (i.e., Drp1, Mfn2), a more detailed understanding of how altering Drp1 or the mitofusins changes mitochondrial membrane composition will also reveal novel aspects of BAK/BAX activation.

In this review, we highlight the complexity of BAK/BAX activation and MOMP, and how they are affected by multiple cellular components. In addition to the well-defined control by the BCL-2 family of proteins, MOMP is also regulated by the composition of the OMM. In contrast to Shakespeare’s Othello, whose demise was instigated by his own misjudgment and inability to interact with others, mitochondrial communication is likely an essential component to BAX/BAK activation, MOMP, and cellular demise. Understanding the complexity by which mitochondrial composition is maintained and influenced by cell survival and cell death pathways will likely reveal novel mediators of cell fate decisions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Annis MG, Soucie EL, Dlugosz PJ, Cruz-Aguado JA, Penn LZ, Leber B, Andrews DW. Bax forms multispanning monomers that oligomerize to permeabilize membranes during apoptosis. EMBO J. 2005;24:2096–2103. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonsson B, Montessuit S, Sanchez B, Martinou JC. Bax is present as a high molecular weight oligomer/complex in the mitochondrial membrane of apoptotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11615–11623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basañez G, Nechushtan A, Drozhinin O, Chanturiya A, Choe E, Tutt S, Wood KA, Hsu Y, Zimmerberg J, Youle RJ. Bax, but not Bcl-xL, decreases the lifetime of planar phospholipid bilayer membranes at subnanomolar concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5492–5497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basañez G, Sharpe JC, Galanis J, Brandt TB, Hardwick JM, Zimmerberg J. Bax-type apoptotic proteins porate pure lipid bilayers through a mechanism sensitive to intrinsic monolayer curvature. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49360–49365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverly LJ, Howell LA, Hernandez-Corbacho M, Casson L, Chipuk JE, Siskind LJ. BAK activation is necessary and sufficient to drive ceramide synthase-dependent ceramide accumulation following inhibition of BCL2-like proteins. Biochem J. 2013;452:111–119. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbes H, Bawab SE, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Selective hydrolysis of a mitochondrial pool of sphingomyelin induces apoptosis. FASEB J. 2001;15:2669–2679. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0539com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbes H, Luberto C, Hsu YT, El Bawab S, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. A mitochondrial pool of sphingomyelin is involved in TNFα-induced Bax translocation to mitochondria. Biochem J. 2005;386:445. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks C, Wei Q, Feng L, Dong G, Tao Y, Mei L, Xie ZJ, Dong Z. Bak regulates mitochondrial morphology and pathology during apoptosis by interacting with mitofusins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11649–11654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703976104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caricchio R, D’Adamio L, Cohen PL. Fas, ceramide and serum withdrawal induce apoptosis via a common pathway in a type II Jurkat cell line. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:574–580. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartron PF, Oliver L, Mayat E, Meflah K, Vallette FM. Impact of pH on Bax alpha conformation, oligomerisation and mitochondrial integration. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartron PF, Arokium H, Oliver L, Meflah K, Manon S, Vallette FM. Distinct domains control the addressing and the insertion of Bax into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10587–10598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty G, Saito M, Shah R, Mao RF, Vadasz C, Saito M. Ethanol triggers sphingosine 1-phosphate elevation along with neuroapoptosis in the developing mouse brain. J Neurochem. 2012;121:806–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, McStay GP, Bharti A, Kuwana T, Clarke CJ, Siskind LJ, Obeid LM, Green DR. Sphingolipid Metabolism Cooperates with BAK and BAX to Promote the Mitochondrial Pathway of Apoptosis. Cell. 2012;148:988–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Gonzalvez F, Jenkins GM, Slomianny C, Chretien D, Arnoult D, Petit PX, Frohman MA. Cardiolipin deficiency releases cytochrome c from the inner mitochondrial membrane and accelerates stimuli-elicited apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:597–606. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifone MG, De Maria R, Roncaioli P, Rippo MR, Azuma M, Lanier LL, Santoni A, Testi R. Apoptotic signaling through CD95 (Fas/Apo-1) activates an acidic sphingomyelinase. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1547–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke CJ, Cloessner EA, Roddy PL, Hannun YA. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) is the primary neutral sphingomyelinase isoform activated by tumour necrosis factor-α in MCF-7 cells. Biochem J. 2011;435:381–390. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colié S, Veldhoven PPV, Kedjouar B, Bedia C, Albinet V, Sorli SC, Garcia V, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Bauvy C, Codogno P, et al. Disruption of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Lyase Confers Resistance to Chemotherapy and Promotes Oncogenesis through Bcl-2/Bcl-xL Upregulation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9346–9353. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordás G, Renken C, Várnai P, Walter L, Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA, Hajnóczky G. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordás G, Várnai P, Golenár T, Roy S, Purkins G, Schneider TG, Balla T, Hajnóczky G. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell. 2010;39:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabotar PE, Westphal D, Dewson G, Ma S, Hockings C, Fairlie WD, Lee EF, Yao S, Robin AY, Smith BJ, et al. Bax Crystal Structures Reveal How BH3 Domains Activate Bax and Nucleate Its Oligomerization to Induce Apoptosis. Cell. 2013;152:519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delivani P, Adrain C, Taylor RC, Duriez PJ, Martin SJ. Role for CED-9 and Egl-1 as Regulators of Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion Dynamics. Mol Cell. 2006;21:761–773. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Yin X, Allan R, Lu DD, Maurer CW, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Fuks Z, Shaham S, Kolesnick R. Ceramide Biogenesis Is Required for Radiation-Induced Apoptosis in the Germ Line of C. elegans. Science. 2008;322:110–115. doi: 10.1126/science.1158111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desagher S, Osen-Sand A, Nichols A, Eskes R, Montessuit S, Lauper S, Maundrell K, Antonsson B, Martinou JC. Bid-induced conformational change of Bax is responsible for mitochondrial cytochrome c release during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:891–901. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler KA, Mathias S, Kolesnick RN. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha activates the sphingomyelin signal transduction pathway in a cell-free system. Science. 1992;255:1715–1718. doi: 10.1126/science.1313189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L, Wang X. Smac, a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell. 2000;102:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Wolf J, Schafer B, Moldoveanu T, Chipuk JE, Kuwana T. BH3 domains other than Bim and Bid can directly activate Bax/Bak. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:491–501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlich F, Banerjee S, Suzuki M, Cleland MM, Arnoult D, Wang C, Neutzner A, Tjandra N, Youle RJ. Bcl-x(L) retrotranslocates Bax from the mitochondria into the cytosol. Cell. 2011;145:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz Y, Schuldiner M. Staying in touch: the molecular era of organelle contact sites. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RF, Martinou JC, Fornallaz-Mulhauser M, Hughes DW, Epand RM. The apoptotic protein tBid promotes leakage by altering membrane curvature. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32632–32639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskes R, Desagher S, Antonsson B, Martinou JC. Bid induces the oligomerization and insertion of Bax into the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:929–935. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.929-935.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JR, Lackner LL, West M, DiBenedetto JR, Nunnari J, Voeltz GK. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. 2011;334:358–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan V, Perera MN, Colombini D, Datskovskiy D, Chadha K, Colombini M. Ceramide and activated Bax act synergistically to permeabilize the mitochondrial outer membrane. Apoptosis Int J Program Cell Death. 2010;15:553–562. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sáez AJ, Coraiola M, Serra MD, Mingarro I, Muller P, Salgado J. Peptides corresponding to helices 5 and 6 of Bax can independently form large lipid pores. FEBS J. 2006;273:971–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sáez AJ, Ries J, Orzáez M, Pérez-Payà E, Schwille P. Membrane promotes tBID interaction with BCL(XL) Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1178–1185. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavathiotis E, Suzuki M, Davis ML, Pitter K, Bird GH, Katz SG, Tu HC, Kim H, Cheng EHY, Tjandra N, et al. BAX activation is initiated at a novel interaction site. Nature. 2008;455:1076–1081. doi: 10.1038/nature07396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geilen CC, Bektas M, Wieder T, Kodelja V, Goerdt S, Orfanos CE. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces sphingomyelin hydrolysis in HaCaT cells via tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8997–9001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.8997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalvez F, Schug ZT, Houtkooper RH, MacKenzie ED, Brooks DG, Wanders RJA, Petit PX, Vaz FM, Gottlieb E. Cardiolipin provides an essential activating platform for caspase-8 on mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:681–696. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds MG, Smits C, Fredericks-Short R, Risk JM, Bailey M, Huang DCS, Day CL. Bim, Bad and Bmf: intrinsically unstructured BH3-only proteins that undergo a localized conformational change upon binding to prosurvival Bcl-2 targets. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:128–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch FL. Cardiolipins and biomembrane function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1113:71–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery D, Nuñez G, Milliman C, Schreiber RD, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature. 1990;348:334–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppins S, Edlich F, Cleland MM, Banerjee S, McCaffery JM, Youle RJ, Nunnari J. The soluble form of Bax regulates mitochondrial fusion via MFN2 homotypic complexes. Mol Cell. 2011;41:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Q, Jin J, Zhou H, Novgorodov SA, Bielawska A, Szulc ZM, Hannun YA, Obeid LM, Hsu YT. Mitochondrially targeted ceramides preferentially promote autophagy, retard cell growth, and induce apoptosis. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:278–288. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M012161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YT, Wolter KG, Youle RJ. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3668–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson SL, Enoksson M, Gogvadze V, Ott M, Orrenius S. Cardiolipin is not required for Bax-mediated cytochrome c release from yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1100–1107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgensmeier JM, Xie Z, Deveraux Q, Ellerby L, Bredesen D, Reed JC. Bax directly induces release of cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:4997–5002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowski M, Norris KL, Cleland MM, Jeong SY, Youle RJ. Role of Bax and Bak in mitochondrial morphogenesis. Nature. 2006;443:658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature05111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann T, Schlipf S, Sanz J, Neubert K, Stein R, Borner C. Characterization of the signal that directs Bcl-x(L), but not Bcl-2, to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:53–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled AR, Moor AN, Li A, Kim K, Ferris DK, Muegge K, Fisher RJ, Fliegel L, Durum SK. Trophic factor withdrawal: p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activates NHE1, which induces intracellular alkalinization. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7545–7557. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7545-7557.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Tu HC, Ren D, Takeuchi O, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJD, Cheng EHY. Stepwise activation of BAX and BAK by tBID, BIM, and PUMA initiates mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2009;36:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: a primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275:1132–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS, Walter P. An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science. 2009;325:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1175088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Byun HS, Bittman R, Saba JD. The sphingolipid degradation product trans-2-hexadecenal induces cytoskeletal reorganization and apoptosis in a JNK-dependent manner. Cell Signal. 2011a;23:1144–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Oskouian B, Fyrst H, Zhang M, Paris F, Saba JD. S1P lyase regulates DNA damage responses through a novel sphingolipid feedback mechanism. Cell Death Dis. 2011b;2:e119. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Mackey MR, Perkins G, Ellisman MH, Latterich M, Schneiter R, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Cell. 2002;111:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Chipuk JE, Bonzon C, Sullivan BA, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. BH3 domains of BH3-only proteins differentially regulate Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization both directly and indirectly. Mol Cell. 2005;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landeta O, Landajuela A, Gil D, Taneva S, Di Primo C, Sot B, Valle M, Frolov VA, Basañez G. Reconstitution of proapoptotic BAK function in liposomes reveals a dual role for mitochondrial lipids in the BAK-driven membrane permeabilization process. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8213–8230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.165852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Rotolo JA, Mesicek J, Penate-Medina T, Rimner A, Liao WC, Yin X, Ragupathi G, Ehleiter D, Gulbins E, et al. Mitochondrial Ceramide-Rich Macrodomains Functionalize Bax upon Irradiation. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshchiner ES, Braun CR, Bird GH, Walensky LD. Direct activation of full-length proapoptotic BAK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E986–95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214313110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letai A, Sorcinelli MD, Beard C, Korsmeyer SJ. Antiapoptotic BCL-2 is required for maintenance of a model leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Sinha S, Kroemer G. Bcl-2 family members: dual regulators of apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:600–606. doi: 10.4161/auto.6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limaye V, Li X, Hahn C, Xia P, Berndt MC, Vadas MA, Gamble JR. Sphingosine kinase-1 enhances endothelial cell survival through a PECAM-1-dependent activation of PI-3K/Akt and regulation of Bcl-2 family members. Blood. 2005;105:3169–3177. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Toman RE, Goparaju SK, Maceyka M, Nava VE, Sankala H, Payne SG, Bektas M, Ishii I, Chun J, et al. Sphingosine kinase type 2 is a putative BH3-only protein that induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40330–40336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell JF, Billen LP, Bindner S, Shamas-Din A, Fradin C, Leber B, Andrews DW. Membrane binding by tBid initiates an ordered series of events culminating in membrane permeabilization by Bax. Cell. 2008;135:1074–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter M, Fang M, Luo X, Nishijima M, Xie X, Wang X. Cardiolipin provides specificity for targeting of tBid to mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:754–761. doi: 10.1038/35036395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter M, Perkins GA, Wang X. The pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member tBid localizes to mitochondrial contact sites. BMC Cell Biol. 2001;2:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-2-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maceyka M, Sankala H, Hait NC, Le Stunff H, Liu H, Toman R, Collier C, Zhang M, Satin LS, Merrill AH, Jr, et al. SphK1 and SphK2, sphingosine kinase isoenzymes with opposing functions in sphingolipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37118–37129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manon S, Chaudhuri B, Guérin M. Release of cytochrome c and decrease of cytochrome c oxidase in Bax-expressing yeast cells, and prevention of these effects by coexpression of Bcl-xL. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Caballero S, Dejean LM, Kinnally MS, Oh KJ, Mannella CA, Kinnally KW. Assembly of the mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel, MAC. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12235–12245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806610200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldoveanu T, Liu Q, Tocilj A, Watson M, Shore G, Gehring K. The X-ray structure of a BAK homodimer reveals an inhibitory zinc binding site. Mol Cell. 2006;24:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montessuit S, Somasekharan SP, Terrones O, Lucken-Ardjomande S, Herzig S, Schwarzenbacher R, Manstein DJ, Bossy-Wetzel E, Basañez G, Meda P, et al. Membrane remodeling induced by the dynamin-related protein Drp1 stimulates Bax oligomerization. Cell. 2010;142:889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen TD, Obeid LM. Ceramide and apoptosis: exploring the enigmatic connections between sphingolipid metabolism and programmed cell death. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:340–363. doi: 10.2174/187152012800228661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen TD, Jenkins RW, Clarke CJ, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Ceramide synthase-dependent ceramide generation and programmed cell death: involvement of salvage pathway in regulating postmitochondrial events. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15929–15942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechushtan A, Smith CL, Lamensdorf I, Yoon SH, Youle RJ. Bax and Bak coalesce into novel mitochondria-associated clusters during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1265–1276. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid LM, Linardic CM, Karolak LA, Hannun YA. Programmed cell death induced by ceramide. Science. 1993;259:1769–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.8456305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskouian B, Sooriyakumaran P, Borowsky AD, Crans A, Dillard-Telm L, Tam YY, Bandhuvula P, Saba JD. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase potentiates apoptosis via p53- and p38-dependent pathways and is down-regulated in colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:17384–17389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perciavalle RM, Stewart DP, Koss B, Lynch J, Milasta S, Bathina M, Temirov J, Cleland MM, Pelletier S, Schuetz JD, et al. Anti-apoptotic MCL-1 localizes to the mitochondrial matrix and couples mitochondrial fusion to respiration. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:575–583. doi: 10.1038/ncb2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera MN, Lin SH, Peterson YK, Bielawska A, Szulc ZM, Bittman R, Colombini M. Bax and Bcl-xL exert their regulation on different sites of the ceramide channel. Biochem J. 2012;445:81–91. doi: 10.1042/BJ20112103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros AM, Nettesheim DG, Wang Y, Olejniczak ET, Meadows RP, Mack J, Swift K, Matayoshi ED, Zhang H, Thompson CB, et al. Rationale for Bcl-xL/Bad peptide complex formation from structure, mutagenesis, and biophysical studies. Protein Sci Publ Protein Soc. 2000;9:2528–2534. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyerl FW, Dai S, Murphy GA, Crawford F, White J, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Elucidation of some Bax conformational changes through crystallization of an antibody-peptide complex. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:447–452. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian S, Wang W, Yang L, Huang HW. Structure of transmembrane pore induced by Bax-derived peptide: Evidence for lipidic pores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17379–17383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807764105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renault TT, Teijido O, Antonsson B, Dejean LM, Manon S. Regulation of Bax mitochondrial localization by Bcl-2 and Bcl-x(L): keep your friends close but your enemies closer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg B, Wang P, Keeble JA, Rodriguez-Enriquez R, Walker S, Owens TW, Foster F, Tanianis-Hughes J, Brennan K, Streuli CH, et al. Bax Exists in a Dynamic Equilibrium between the Cytosol and Mitochondria to Control Apoptotic Priming. Mol Cell. 2013;49:959–971. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorrano L, Ashiya M, Buttle K, Weiler S, Oakes SA, Mannella CA, Korsmeyer SJ. A distinct pathway remodels mitochondrial cristae and mobilizes cytochrome c during apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2002;2:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorrano L, Oakes SA, Opferman JT, Cheng EH, Sorcinelli MD, Pozzan T, Korsmeyer SJ. BAX and BAK regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: a control point for apoptosis. Science. 2003;300:135–139. doi: 10.1126/science.1081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siskind LJ, Colombini M. The lipids C2- and C16-ceramide form large stable channels. Implications for apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38640–38644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000587200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siskind LJ, Kolesnick RN, Colombini M. Ceramide Channels Increase the Permeability of the Mitochondrial Outer Membrane to Small Proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26796–26803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200754200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siskind LJ, Feinstein L, Yu T, Davis JS, Jones D, Choi J, Zuckerman JE, Tan W, Hill RB, Hardwick JM, et al. Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 Family Proteins Disassemble Ceramide Channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6622–6630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706115200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasula SM, Gupta S, Datta P, Zhang Z, Hegde R, Cheong N, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins are substrates for the mitochondrial serine protease Omi/HtrA2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31469–31472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300240200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SJ, Vance JE. Phosphatidylserine synthase-1 and -2 are localized to mitochondria-associated membranes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34534–34540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Tashima M, Takahashi A, Uchiyama T, Okazaki T. Ceramide generation in nitric oxide-induced apoptosis. Activation of magnesium-dependent neutral sphingomyelinase via caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10654–10660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrones O, Antonsson B, Yamaguchi H, Wang HG, Liu J, Lee RM, Herrmann A, Basañez G. Lipidic pore formation by the concerted action of proapoptotic BAX and tBID. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30081–30091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen AM, Ekert PG, Pakusch M, Silke J, Connolly LM, Reid GE, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ, Vaux DL. Identification of DIABLO, a mammalian protein that promotes apoptosis by binding to and antagonizing IAP proteins. Cell. 2000;102:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei MC, Lindsten T, Mootha VK, Weiler S, Gross A, Ashiya M, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. tBID, a membrane-targeted death ligand, oligomerizes BAK to release cytochrome c. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2060–2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KG, Hsu YT, Smith CL, Nechushtan A, Xi XG, Youle RJ. Movement of Bax from the Cytosol to Mitochondria during Apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1281–1292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XP, Zhai D, Kim E, Swift M, Reed JC, Volkmann N, Hanein D. Three-dimensional structure of Bax-mediated pores in membrane bilayers. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e683. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi R, Lartigue L, Perkins G, Scott RT, Dixit A, Kushnareva Y, Kuwana T, Ellisman MH, Newmeyer DD. Opa1-mediated cristae opening is Bax/Bak and BH3 dependent, required for apoptosis, and independent of Bak oligomerization. Mol Cell. 2008;31:557–569. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N, Shi Y. Mechanisms of Apoptosis Through Structural Biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:35–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang QH, Church-Hajduk R, Ren J, Newton ML, Du C. Omi/HtrA2 catalytic cleavage of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) irreversibly inactivates IAPs and facilitates caspase activity in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1487–1496. doi: 10.1101/gad.1097903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaltsman Y, Shachnai L, Yivgi-Ohana N, Schwarz M, Maryanovich M, Houtkooper RH, Vaz FM, De Leonardis F, Fiermonte G, Palmieri F, et al. MTCH2/MIMP is a major facilitator of tBID recruitment to mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:553–562. doi: 10.1038/ncb2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha J, Weiler S, Oh KJ, Wei MC, Korsmeyer SJ. Posttranslational N-myristoylation of BID as a molecular switch for targeting mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 2000;290:1761–1765. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Guan Z, Murphy AN, Wiley SE, Perkins GA, Worby CA, Engel JL, Heacock P, Nguyen OK, Wang JH, et al. Mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1 is essential for cardiolipin biosynthesis. Cell Metab. 2011;13:690–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Chang DC. Dynamics and structure of the Bax-Bak complex responsible for releasing mitochondrial proteins during apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2186–2196. doi: 10.1242/jcs.024703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong WX, Li C, Hatzivassiliou G, Lindsten T, Yu QC, Yuan J, Thompson CB. Bax and Bak can localize to the endoplasmic reticulum to initiate apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:59–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]