SUMMARY

CD4 T-follicular helper cells (TFH) are central for generation of long-term B cell immunity. A defining phenotypic attribute of TFH cells is expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR5, and TFH cells are typically identified by co-expression of CXCR5 together with other markers such as programmed death (PD)-1. Herein we report high-level expression of the nutrient transporter, folate receptor (FR)4 on TFH cells in acute viral infection. Distinct from the expression profile of conventional TFH markers, FR4 was highly expressed by naive CD4 T cells, was down regulated after activation and subsequently re-expressed on TFH cells. Furthermore, FR4 was maintained, albeit at lower levels, on memory TFH cells. Comparative gene expression profiling of FR4hi, versus FR4lo antigen-specific CD4 effector T cells revealed a molecular signature consistent with TFH and TH1 subsets, respectively. Interestingly, genes involved in the purine metabolic pathway, including the ecto-enzyme CD73, were enriched in TFH cells compared to TH1 cells, and phenotypic analysis confirmed expression of CD73 on TFH cells. As there is now considerable interest in developing vaccines that will induce optimal TFH cell responses, the identification of two novel cell surface markers should be useful in characterization and identification of TFH cells following vaccination and infection.

Keywords: CD4 T cells, folate receptor 4, CD73, viral infection, B cells

INTRODUCTION

CD4 T follicular helper (TFH) cells are critical for generation of long-term B cell immunity. Interaction of antigen-specific TFH cells with cognate B cells in germinal centers leads to development of high-affinity memory B cells and plasma cells necessary for production of high-affinity antibody [1, 2]. Due to their central role in B cell immunity, optimizing TFH cell responses is an important consideration in vaccine design while controlling augmented TFH cell responses is of therapeutic value in antibody mediated autoimmune diseases such as lupus and arthritis [3]. Consequently, there is a great deal of interest in characterizing pathways underlying TFH cell differentiation and understanding how TFH cells differ from other CD4 helper subsets.

One of the key distinguishing features of TFH cells is surface expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR5, which is important for their positioning in the germinal centers of B cell follicles [4, 5]. Recently, the transcriptional repressor, B cell lymphoma-6 (Bcl-6) has been demonstrated as an important regulator of TFH cell differentiation [6, 7]. Numerous other molecules critical for TFH cell function have been identified; these include the B-cell helper cytokine interleukin 21 [8]; inducible costimulator (ICOS) [9]; the immunoregulatory receptor, programmed death (PD)-1 [5]; the apoptosis inducing receptor, Fas; and the adhesion and signaling molecule SLAM associated protein (SAP), among others [10].

Many phenotypic attributes of TFH cells, such as up-regulation of CXCR5, PD-1, and ICOS have also been observed on non-TFH cells immediately following TCR stimulation [11, 12]. For instance, a recent study of in vitro stimulated CD4 T cells demonstrated that early TH1 differentiation is marked by TFH-like transition with expression of CXCR5, PD-1, and Bcl-6 [13]. In vivo studies examining TFH cell differentiation in the absence of B-cell derived signals have demonstrated that subsequent interaction of TFH cells with cognate B cells reinforces and sustains expression of these markers, which are not maintained on TH1 cells [14]. Indeed, a subset of TFH cells actively interacting with B cells in the germinal centers (GC), referred to as GC TFH cells, expresses highest amounts of CXCR5, PD-1, and ICOS [15].

The relationship of TFH cells to TH1 cells has received a great deal of interest and has been the focus of several recent studies [7, 13, 16, 17]. A useful system to study CD4 effector differentiation are SMARTA transgenic T cells, which express TCR specific for the MHC-Class II restricted lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) GP66–77 epitope. After acute LCMV infection, SMARTA CD4 T cells differentiate into two phenotypically and functionally distinct effector subsets, B cell helper TFH cells and cytolytic TH1 cells but not T regulatory cells or other CD4 helper subsets. Thus, the LCMV model provides an excellent system for resolving critical aspects of TFH cell function and phenotype in relation to TH1 cells.

In this study, we report the identification of two novel markers that distinguish TFH cells from TH1 cells. Using the LCMV infection model, we identified that folate receptor 4 (FR4), a nutrient transporter for the vitamin folic acid, is expressed by TFH cells. Kinetic analysis of antigen specific CD4 T cells demonstrated dynamic regulation of FR4 expression on TFH cells. FR4 was highly expressed by naive CD4 T cells, was dramatically down-regulated after activation, and was strikingly re-expressed on TFH cells. Gene expression analysis of TFH and TH1 cells using FR4 as a marker showed that genes related to adenosine metabolism, including the adenosine generating ecto-enzyme Nt5e/CD73, were selectively up-regulated in TFH cells, and phenotypic analysis confirmed expression of CD73 on TFH cells. These studies present the novel observation that TFH cells coordinately express FR4 and CD73.

RESULTS

FR4 expression distinguishes TFH and TH1 antigen-specific CD4 effector subsets

During acute viral infection, CD4 T cells predominantly differentiate into two phenotypically and functionally distinct helper subsets: a CXCR5-expressing, Ly6Clo B cell helper TFH cell subset and a CXCR5−, Ly6Chi cytolytic TH1 cell subset [16]. While comparing transcriptional profile of Ly6Clo and Ly6Chi subsets we observed that the expression profile of a recently discovered metabolite receptor, folate receptor (FR)4 was strikingly different from that of conventional surface TFH cell markers such as PD-1 and ICOS. While PD-1 and ICOS were upregulated both on TH1 and TFH cells, with a higher relative expression on TFH cells (Figure S1), FR4 was downregulated on TH1 cells and upregulated on TFH cells (Figure 1A). Genes encoding other folate transport proteins, including the ubiquitously expressed reduced folate carrier (RFC), were not differentially expressed between TFH and TH1 subsets (Figure 1B). Ex vivo staining of FR4 and Ly6C confirmed gene expression data (Figure 1C) suggesting that FR4 could be a potential TFH cell marker. Examination of FR4 expression on day 8 CXCR5+, PD-1hi TFH cells revealed that this was indeed the case (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

FR4 expression distinguishes TFH and TH1 subsets. Antigen-specific CD4 effectors in spleen were sorted based on Ly6C expression and mRNA levels of FR4 (A) and other folate transport genes (B) were examined. (C) Flow cytometric analysis confirmed high FR4 expression on Ly6Clo antigen-specific CD4 T cells. (D) shows expression of CXCR5 and PD-1 on day 8 effectors and histograms show FR4 expression on TFH and TH1 subsets in. In (E) comparative phenotypic analysis of FR4hi, CXCR5+ (red histogram) and FR4lo, CXCR5− subsets (blue histogram) is shown. FR4 is highly expressed by GL7+, CXCR5+ GC TFH (F) and (G) shows localization of FR4 expressing CD4 T cells in the germinal centers in spleen at day 12 post-infection. (H) shows comparative expression profile of FR4 on antigen-specific CD4 T cells in the spleen, liver, and lung. FR4 expression on endogenous GP66 tetramer positive cells is shown in (I). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

To establish that FR4hi, CXCR5+ cells represented TFH cells, we first examined phenotypic characteristics of this population (Figure 1E). Intracellular staining of the TFH-determining transcription factor Bcl-6 showed higher expression on FR4hi, CXCR5+ cells. Correspondingly, expression of the T-box transcripton factor T-bet was higher in FR4lo, CXCR5− effectors. Additionally, FR4hi, CXCR5+ cells showed a SLAMlo, ICOShi phenotype confirming their identity as TFH cells. Next, we performed detailed phenotypic analysis to directly compare CXCR5+ versus FR4hi cells (Figure S2). Both CXCR5+ and FR4hi subsets were comparable for expression of key TFH markers such as PD-1, ICOS, CD200, Bcl-6, and GL7.

To more carefully determine whether the more polarized TFH cell subset in the germinal centers expressed FR4, we co-stained day 8 effectors with CXCR5, GL7, and FR4 [10]. FR4 expression on GL7+, CXCR5+ GC TFH cells was 1.7-fold higher than GL7−, CXCR5+ TFH cells, suggesting that FR4hi TFH cells were located in germinal centers (Figure 1F). To confirm this, we immunofluorescently stained spleen sections at day 12 post-infection with PNA (green) to detect germinal center B cells, anti-CD4 (red), and anti-FR4 (blue) antibodies (Figure 1G). Panel 3 shows digital overlays of all three respective stains; co-localization of FR4 on CD4 T cells within the GC indicate that FR4hi TFH cells migrate to germinal centers.

Consistent with predominant localization of TFH cells to lymphoid organs, antigen-specific CD4 effectors in lung and liver demonstrated low FR4 expression compared to spleen (Figure 1H). Finally, examination of endogenous GP 66 tetramer specific cells 8 days after LCMV infection showed that TFH cells generated from polyclonal CD4 T cells also highly expressed FR4 (Figure 1I).

Because FR4 is highly expressed by Foxp3+ T regulatory cells [18], we wanted to determine whether identification of TFH cells using FR4 could result in inclusion of T-regulatory cells. For this purpose, we examined SMARTA TCR transgenic CD4 T cells and also endogenous GP66 tetramer positive cells 8 days after LCMV infection. CD4 effectors derived from SMARTA TCR transgenic T cells did not express Foxp3 (Figure S3, A, B). Additionally, endogenous polyclonal GP66 tetramer positive cells did not express Foxp3 (C). These data show that LCMV-specific FR4hi TFH cell subset does not comprise T regulatory cells.

Level of FR4 expression on naive CD4 T cells does not pre-determine TFH or TH1 cell fate

Phenotypic and functional characterization of antigen-specific CD4 T cells showed that FR4 expression was associated with functional dichotomy of effectors with the FR4lo subset expressing high T-bet levels, characteristic of TH1 cells, and the FR4hi subset showing a TFH cell phenotype with expression of Bcl-6 and CXCR5. Interestingly, naive CD4 T cells also expressed FR4 at varying levels with approximately 70–85% showing intermediate to high FR4 expression and a small proportion expressing low levels of FR4 (Figure 2A, panel 1). This raised the possibility that level of FR4 expression on naive T cells could play a role in TH1 versus TFH effector commitment.

Figure 2.

FR4 expression on naive precursors does not determine TFH/TH1 commitment. Differentiation of FR4hi and FR4lo cells isolated from naive mouse spleen was determined as shown in (A). In (B), frequency and expression of FR4 on donor cells is shown in recipient spleen at day 8 post-infection. Bar graphs in (C) show number and frequency of donor cells per spleen. (D), shows % of TFH identified by co-expression of CXCR5 and PD-1, and CXCR5 and FR4 and % of GL7+ GC TFH in spleen at day 8 post-infection. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM

To determine whether FR4lo versus FR4hi naive cells met divergent cell fates after activation, we adoptively transferred equal numbers of sorted FR4lo and FR4hi naive subsets into individual mice, infected chimeric hosts with LCMV the next day, and analyzed differentiation of donor cells at 8 days post-infection (Figure 2A). Strikingly, expression of FR4 was similar in effectors generated from both donor subsets, with approximately 50% expressing FR4, suggesting that FR4 expression was dynamically regulated on antigen-specific CD4 T cells after activation. (Figure 2B,C).

Analysis of effector differentiation demonstrated that both FR4lo and FR4hi naive precursors gave rise to comparable frequencies of TFH and TH1 cells (Figure 2D). Because FR4 expression was highest on GC TFH cells, we examined whether FR4hi naive precursors were more likely to differentiate into this subset. However, similar frequency of GL7+, CXCR5+ GC TFH cells between both donor subsets suggests that this was not the case. Together, the data show that while heterogeneity in FR4 expression marks functionally different CD4 effector subsets, FR4 expression in naive precursors does not pre-determine effector commitment.

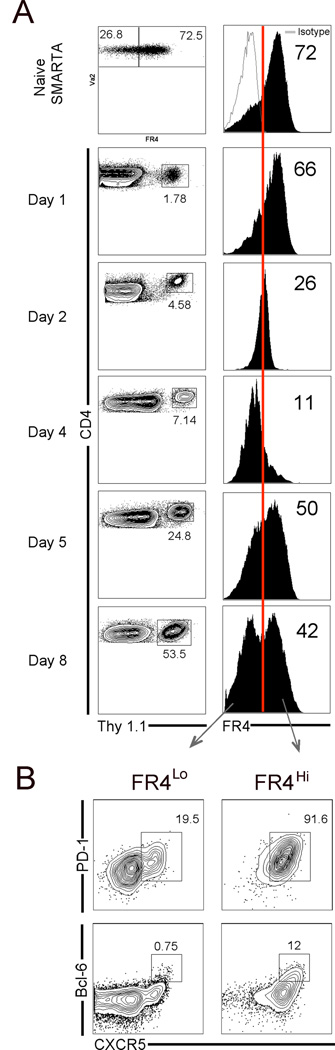

Dynamic regulation of FR4 expression during TFH cell differentiation

Studies using sorted FR4lo and FR4hi naive CD4 T cells showed lack of differential programming among the subsets. However, the inter-conversion of FR4lo and FR4hi cells strongly suggested dynamic regulation of FR4 expression on antigen-specific cells after infection. Therefore, we examined temporal kinetics of FR4 expression on CD4 effectors in the context of TFH cell differentiation.

Based on high expression of FR4 on naive precursors and TFH cells but not TH1 cells, we hypothesized that subsequent to activation, FR4 would be down-regulated on TH1 cells while selectively being retained on TFH cells. Surprisingly, FR4 modestly decreased on all antigen-specific CD4 T cells at day 1, was almost entirely down-regulated at day 2, continued to be expressed at low levels until day 4, and showed a striking increase at day 5 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Dynamic regulation of FR4 expression during TFH differentiation. (A) Kinetic analysis of FR4 expression on naive and antigen-specific CD4 T cells. Red line indicates percentage of FR4hi cells relative to isotype control staining. In (B), percentage of CXCR5+, PD-1hi TFH cells and CXCR5+, Bcl-6+ GC TFH cells in FR4lo versus FR4hi subsets is shown. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

In contrast to the acute down-regulation of FR4, the majority of antigen-specific CD4 T cells up-regulated both PD-1 and CXCR5 early after infection (Figure S4). Interestingly, re-expression of FR4 at day 5 coincided with the emergence of a clear-cut CXCR5+, PD-1hi TFH subset and at day 8 two distinct FR4lo and FR4hi subsets were observed. Phenotypic examination showed that while the majority of FR4hi effectors were CXCR5+ and PD-1hi, a small percentage of FR4lo cells also expressed these markers (Figure 3B). Notably, however, it was the FR4hi subset that almost entirely comprised of Bcl-6+, CXCR5+ GC TFH cells. The data show that FR4 expression was dynamically regulated during TFH cell differentiation with an initial complete down-regulation on all antigen-specific CD4 T cells followed by gradual re-expression on TFH cells.

Re-expression of FR4 on TFH cells requires interaction with cognate B cells

The dynamic expression pattern of FR4 suggested that initial priming of CD4 T cells by antigen-presenting cells resulted in down-regulation of FR4 while the second round of signaling by cognate B cells induced re-expression of FR4 on TFH cells. To determine whether FR4 would be re-expressed on antigen-specific CD4 T cells in the absence of cognate B cell help, we transferred naive SMARTA cells to wild-type B6 hosts or to B cell transgenic mice in which majority of the B cells expressed B cell receptor specific for the hen-egg lysozyme (HEL) protein. Mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong and B cell and CD4 T cell responses were assessed at 8 days post-infection (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Re-expression of FR4 on TFH cells requires interaction with cognate B cells. SMARTA CD4 T cells were transferred to WT or HEL Tg mice and responses were assessed 8 days after LCMV infection (A). Flow plots in (B) are gated on total B220+ B cells and show Fas+, PNA+, GC B cells in spleen. (C) shows % GC cells in spleen and total number of GC B cells in spleen is shown in (D). (E) LCMV enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed at day 8; LCMV-specific IgG endpoint titers in sera are shown. Flow plots in (F) are gated on CD4+ SMARTA cells in the spleen and show frequency of TFH cells and GC TFH cells in WT and HEL Tg mice. (G) shows frequency of FR4hi, CXCR5+ cells and black histogram shows % FR4hi antigen-specific CD4 T cells. Bar graph shows mean % TFH and % FR4hi antigen-specific CD4 T cells in peripheral blood (H) and spleen (I). (J), shows total number of TFH and FR4hi cells in spleen. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Bar graphs show mean ± SEM

HEL transgenic mice showed impairment in generation of antigen-specific B cell responses after LCMV infection. Frequency of germinal center B cells was markedly decreased in HEL transgenic mice compared to robust responses in WT mice (Figure 4B–D). Additionally, transgenic mice failed to make LCMV-specific antibody responses as demonstrated by low LCMV-specific IgG titers in serum (Figure 4E).

We observed a 2-fold reduction in CXCR5+, PD-1hi cells (as a percentage of transferred SMARTA cells) compared to WT control mice (Figure 4F). Consistently, the percentage of GC TFH cells identified by GL7 and Bcl-6 expression was also decreased. This is the expected outcome as TFH cell differentiation occurs but is poorly sustained in the absence of antigen-specific B cells [19].

If FR4 re-expression on CD4 effectors occurred independently of TFH cell differentiation, then a decrease in % of TFH and GC TFH cells in HEL Tg mice would not be accompanied by a decrease in % FR4hi CD4 effectors. The corresponding decrease in % of FR4hi cells in HEL Tg mice compared to controls (Figure 4G–J), suggests that FR4 expression was directly linked to the TFH cell developmental program.

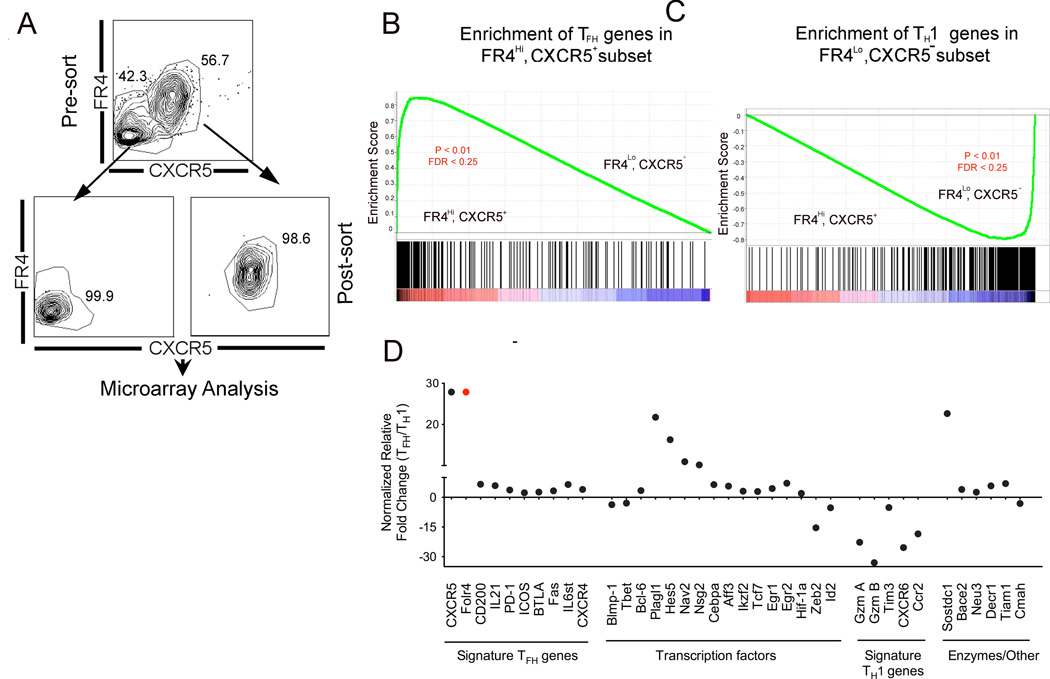

Transcriptional profiling of CD4 effectors confirms FR4 as a robust TFH cell marker

Having identified FR4lo and FR4hi CD4 effectors as phenotypically and functionally distinguishable populations, we examined the molecular signature of these populations using Affymetrix 430 microarrays. Because TFH cells are typically identified by co-expression of CXCR5 with other surface markers, we sorted CD4 effectors based on CXCR5 and FR4. Figure 5A shows pre-sort and post-sort flow-plots gated on antigen specific CD4 T cells isolated 12 days after infection.

Figure 5.

Gene expression profiling of TFH and TH1 cells. (A) shows sorting strategy used to purify day 12 SMARTA CD4 T effectors based on FR4 and CXCR5 expression. Differentially regulated genes between TFH and TH1 subsets were identified using significance analysis of microarrays, which found 711 differentially regulated genes with a false discovery rate of 0.08 and a fold change of at least 2-fold. GSEA plots in B and C, show enrichment profile of TFH and TH1 genes in FR4hi, CXCR5hi and FR4lo, CXCR5lo subsets, respectively. Relative expression of select genes in TFH/TH1 subsets is shown in (D). Of note, CXCR5+, FR4hi cells did not express Foxp3 transcript levels indicating that this subset did not comprise of T follicular regulatory cells. Data are representative of two independent replicates.

To confirm that FR4hi, CXCR5+ subset represented TFH cells and FR4lo, CXCR5− subset corresponded to TH1 cells, we used gene set enrichment analysis [20]. First, a rank ordered list of “signature” TFH and TH1 genes was generated using gene expression data of antigen-specific TFH and TH1 subsets [7]. To determine the degree to which each signature gene set was represented in the present analysis we used the enrichment score (ES). The magnitude of the ES, which ranges from −1 to +1, shows the degree to which a gene set is overrepresented at the top or bottom of a ranked list of genes. The enrichment plots in Figure 5B and C provide a graphical representation of the enrichment score for each of the gene sets.

An enrichment score of 0.8 demonstrates that TFH genes were highly enriched in the FR4hi, CXCR5+ subset indicating that FR4 is a robust marker to identify TFH (Figure 5B). Not surprisingly, CXCR5 and FR4 were among the top genes highly expressed in TFH cells compared to TH1 cells. Consistently, expression levels of CD200, IL-21, PD-1, ICOS, BTLA, and Fas were higher in the TFH cell subset (Figure 5D). Bcl-6 expression was 3.4-fold higher and Blimp-1 expression 3.6-fold lower in the TFH subset (Figure 5D). TFH cells did not express the Foxp3 transcript indicating that CXCR5+, FR4hi cells did not comprise T follicular regulatory cells [21]

Both subsets expressed the TH1- transcription factor, T-bet (TFH/naive = 14.12; TH1/naive= 38.58) and the classic TH1 cytokine IFN-G (TFH/naive = 19.08; TH1/naive=36.58), with higher relative expression in TH1 cells. However, only TH1 cells expressed granzyme A and B. T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (Tim3) a TH1-specific protein that plays a critical role in tempering TH1-specific immune responses [22] was also selectively expressed by TH1 cells. The cytokine and chemokine receptors, CCR2 and CXCR6 were selectively expressed by TH1 cells. The ligand for CXCR6, CXCL16 is highly expressed in the liver and lung while lower levels are expressed in spleen, therefore CXCR6-CXCL16 interaction may direct homing of TH1 effectors to peripheral tissues [23]. The transcription factor, inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2) thought to regulate CXCR6 expression in NKT cells was 5.2 fold elevated in TH1 subset compared to TFH cells (TH1/naive= 21.92; TFH/naive = 6.30, Figure 5F) [24]. The micro-RNA 200 family target gene, Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (Zeb2) [25], a transcriptional repressor was also selectively expressed in TH1. Incidentally, Zeb2 is upregulated by about 2.5-fold in effector and memory CD8 T cells compared to naive T cells [26] but its role in T cell differentiation is unclear. Thus, the molecular signature of TFH and TH1 subsets sorted using FR4 as a marker closely reflected phenotypic and functional properties of each subset.

Differentially regulated metabolic genes in TFH cells

Because TFH cells expressed high levels of the folate receptor, we hypothesized that metabolic enzymes directly related to folate metabolism would also be expressed at higher levels. Surprisingly, however, there were no genes in the folate metabolic pathway that were differentially expressed in TFH cells. A select list of metabolic pathways enriched in TFH is shown in Figure 6A.

Figure 6.

Gene expression profiling leads to identification of CD73 as a novel TFH cell marker. Table A provides a list of select metabolic pathways enriched in TFH. (B), shows genes related to purine metabolic pathway differentially expressed between TFH and TH1 subsets; P2rx7, purinergic receptor P2X ligand gated ion channel 7; ADA, adenosine deaminase; ADK, adenosine kinase; Pde2a, phosphodiesterase 2a; Dck, deoxycytidine kinase. (C) Phenotypic analysis of CD73 confirms high expression on FR4hi and CXCR5+ antigen-specific TFH cells. (D, E) Comparison of TFH cells identified using CXCR5, PD-1 versus CD73 and FR4. Data are representative of three independent replicates.

Because folate functions as a co-factor in numerous biological reactions, the most significant of which involve nucleotide metabolism, we next examined genes related to nucleotide metabolism. Interestingly, a number of genes involved in purine salvage pathway were differentially expressed between TFH and TH1 subsets (Figure 6B). The gene ecto-5’-nucleotidase (Nt5e/CD73) was 3.7-fold higher in TFH compared to TH1 subsets. To determine if TFH preferentially expressed CD73 on their surface, we stained SMARTA effectors with antibody against CD73 and found a high correlation between expression of CD73 with that of FR4 and CXCR5 (Figure 6C). Furthermore, antigen-specific TFH and TH1 cells identified using FR4 and CD73 shared phenotypic attributes with TFH and TH1 cells identified by conventional markers, CXCR5 and PD-1 (Figure 6D, E). These results show that FR4 and CD73 can be used to clearly distinguish between TFH and TH1 CD4 T cells.

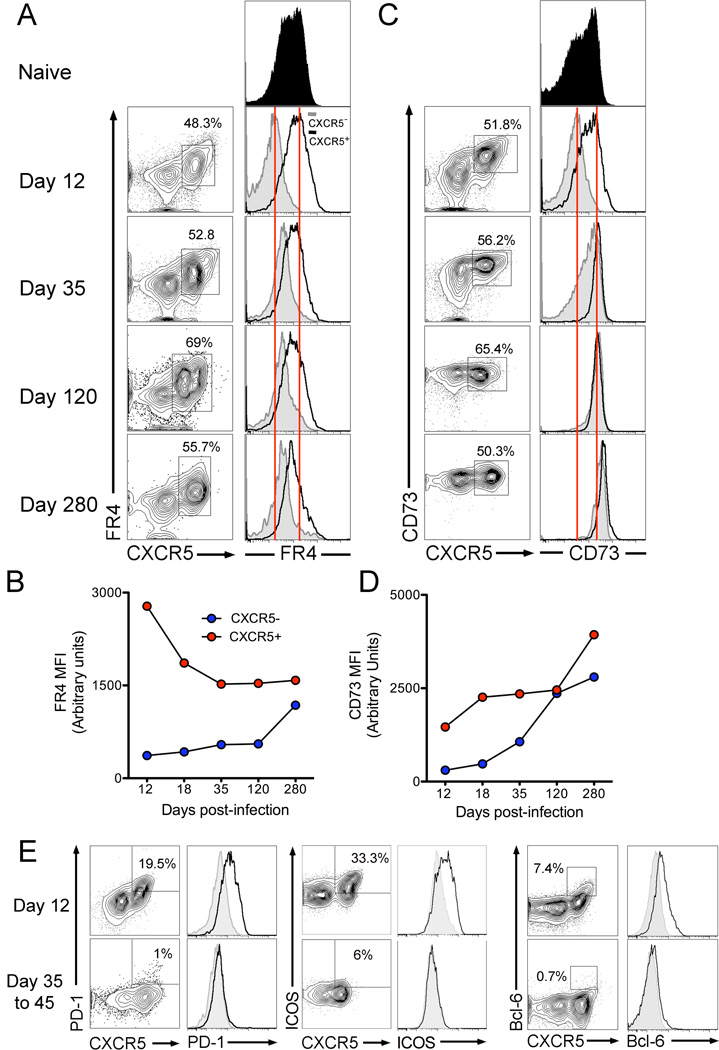

FR4 expression is maintained on memory CXCR5+cells

Based on the high and relatively selective expression profile of FR4 and CD73 on TFH cells at the effector time point, we wanted to determine whether these markers were also selectively maintained on memory CXCR5+ cells. To address this question, we assessed expression of FR4 and CD73 on antigen-specific CD4 T cells during the peak germinal center response (day 12) and at various memory time-points (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Expression of FR4 is sustained on memory CXCR5+ antigen-specific cells. Kinetics of FR4 (A,B) and CD73 (C,D) expression on antigen-specific CD4 T cells from day 12 to day 280. Histograms show expression on CXCR5− (grey) and CXCR5+ (black) subsets. Figure E shows expression of PD-1, ICOS, and Bcl-6 on antigen-specific CD4 T cells at effector and memory time-points. Data are representative of three independent experiments

Kinetic analysis of FR4 expression showed that CXCR5+ cells continued to express FR4 with an initial sharp decline (1.5-fold) in FR4 MFI at day 18, coinciding with the culmination of the germinal center reaction, followed by relatively steady-state maintenance from day 35 to day 280 after infection (Figure 7A,B). Interestingly, FR4 was gradually re-expressed on CXCR5− cells with a 3-fold increase in FR4 expression at day 280 compared to day 12. While the mechanism driving re-expression of FR4 on CXCR5− cells is not known, it may result from induction of transcriptional program of quiescence. Indeed, the high level expression of FR4 in naive CD4 T cells prior to its down regulation upon T cell activation supports this possibility.

In contrast to the differential kinetics of FR4 on CXCR5− and CXCR5+ cells, CD73 expression increased in both subsets over time (Figure 7C,D). CXCR5+ cells showed a 2.7-fold increase and CXCR5− showed a 9-fold increase in CD73 expression at day 280 compared to day 12 such that by memory time-point both subsets expressed uniformly high levels of CD73

This expression profile of FR4 and CD73 on antigen-specific TFH and TH1 subsets stands in sharp contrast to that of conventional TFH cell markers in two main ways. Firstly, PD-1, ICOS, and Bcl-6 are rapidly downregulated on TFH cells after completion of the germinal center reaction with similar expression levels on CXCR5+ and CXCR5− cells at day 35–45 post-infection (Figure 7E). Secondly, PD-1, ICOS, and Bcl-6 are not re-expressed by either CXCR5− or CXCR5+ antigen-specific memory subsets. This suggests that the regulation of FR4 and CD73 on antigen-specific CD4 T cells is different from the program driving expression of conventional TFH cell markers.

Finally, we wanted to determine expression profile of FR4 and CD73 on human TFH cells. The human homolog to murine FR4, folate receptor delta /folate binding protein 3 (FRD, FOLBP3) is a 27kD protein with restricted temporal and spatial expression [27]. As an antibody against FRD was unavailable, we were unable to examine expression pattern of this protein. To determine whether peripheral CD4 T cells in humans expressed CD73, we employed a monoclonal antibody against CD73 [28]. Peripheral blood was obtained from 6 healthy individuals and expression profile of CD73 was evaluated on CD4 T cell subsets and B cells (Supplementary Figure 5). Among lymphocytes, circulating B cells expressed highest levels of CD73 and expression of CD73 on CD4 T cells varied widely among individuals. While a subset of naive CD4 T cells and memory CXCR5− cells expressed CD73, very little CD73 expression was observed on CXCR5+ circulating memory TFH cell subsets. More studies are needed to determine whether human TFH cells express other molecules related to folate and purine metabolism, and whether these would serve as useful markers to identify TFH cells after vaccination or infection.

DISCUSSION

The present study has three main findings: first, that FR4 is a marker for identifying TFH cells and that FR4 is highly expressed on GC TFH cells; second, that FR4 expression is linked to the TFH developmental program; and third, that FR4 expression is maintained on CXCR5+ cells well into the memory phase. In addition, gene expression analysis of FR4hi, CXCR5+ effectors enabled the identification of yet another TFH cell marker, CD73. Our findings are timely given the interest in understanding phenotypic, genomic, and functional aspects of TFH cells and should, therefore, be of utility to the field.

In the context of LCMV infection, we show that antigen-specific CD4 T cells differentiate into an FR4hi TFH cell subset that is CXCR5+, Bcl-6+, and Ly6Clo, and an FR4lo TH1 subset expressing Ly6C but not CXCR5 and Bcl-6. Despite these phenotypic differences, both subsets expressed the TH1 master transcription factor, T-bet and the classic TH1 cytokine IFN-γ. This observation is consistent with those of Fazileau et al. who demonstrated high T-bet and IFNγ message levels on antigen-specific CXCR5hi, ICOShi TFH cells, 7 days after challenge with pigeon cytochrome C [29]. These overlapping attributes suggest that common nodes may exist between TFH and TH1 differentiation programs and provide support for the multistage and multifactorial model of TFH differentiation, where subsequent to priming, successive rounds of interaction with cognate B cells coupled with appropriate cytokine skewing reinforces TFH cell differentiation [13–15].

Transcriptional profiling of CD4 effectors based on FR4 and CXCR5 validated our phenotypic data demonstrating FR4 as a robust TFH cell marker. Furthermore, FR4hi, CXCR5+ subset showed 2.7-fold lower expression of cytidine monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (Cmah), a cytosolic enzyme repressed in GC TFH cells [10]. This indicated that FR4hi, CXCR5+ cells comprised the GC TFH population. We noted other genes of interest; four among the top 10 highly expressed genes in TFH were pattern specification genes (Figure 5F), which included basic helix-loop-helix gene, hairy and enhancer of split (Hes)5. Hes5 is critical for determining cell-fate in the developing brain [30] and Hes5 is upregulated by folate supplementation in neural stem cells. It is possible that folate uptake via FR4 may induce upregulation of Hes5 and, potentially, other pattern-forming genes in TFH cells [31].

A key observation from this study is that TFH cells highly express FR4; however, the function of FR4 in TFH cells is not apparent. The high expression of FR4 raises the question as to whether TFH cells have a high metabolic demand for folate. Folate is an essential B vitamin that plays a crucial role in nucleotide synthesis and its requirements increase in cycling cells [32, 33]. Indeed, deficiency of folate impairs both CD4 and CD8 T cell responses [34]. However, the kinetics of FR4 expression appear to be inconsistent with the metabolic role of folate in cell proliferation. First, FR4 is highly expressed on naive CD4 T cells but is downregulated soon after T cell activation when folate requirements for proliferation are very high. Secondly, there is no evidence that TFH cells are hyperproliferative compared to TH1 cells. On the contrary, as assayed by thymidine incorporation in vitro, TFH cells are markedly hypoproliferative compared to non-TFH cells [35]. However, because folate functions as a co-factor in numerous biological reactions it is possible that TFH cells have a requirement for metabolic pathways that indirectly depend on folate [36].

One such example is the purine metabolic pathway, which was highly enriched in TFH cells. A number of genes involved in purine salvage pathway were differentially expressed between TFH and TH1 subsets. The gene for ecto-5’-nucleotidase (Nt5e/CD73) was 3.7-fold higher in TFH compared to TH1 subsets and phenotypic analysis confirmed high surface expression of CD73 on TFH cells. CD73 is a GPI-anchored protein, which hydrolyzes extracellular AMP, generated from apoptotic cells, to adenosine [37, 38]. The expression of CD73 is cell-type specific and is inversely related to expression of the adenosine degrading enzyme ADA [39]. TFH cells also expressed lower ADA message levels (2-fold lower than naive); the CD73hi, ADAlo phenotype suggests that TFH cells have an “adenosine producing metabolic signature” [40].

Once generated, extracellular adenosine can signal via surface adenosine receptors to inhibit proliferation and/or inhibit inflammation via the induction of intracellular cAMP [40, 41]. It is possible, therefore, that adenosine may dampen inflammatory cytokine production in TFH cells and/or suppress proliferation of low-affinity B cells. CD73 has also been shown to function as an adhesion molecule and is speculated to facilitate adhesion of B cells to follicular dendritic cells (FDC) in the germinal center [42]. Additional studies are needed to determine whether TFH utilize purinergic pathways to facilitate autocrine or paracrine signaling, to adhere to FDC or B cells, and/or to meet bioenergetic demands.

Interestingly, T regulatory cells share the FR4hi, CD73hi phenotype of TFH cells [18, 38]. Common pathways involved in tolerizing T regulatory cells, centrally during thymic development, and TFH cells, peripherally in the germinal center, may result in concerted expression of FR4 and CD73. This program, however, does not appear to be directly regulated by Foxp3, as TFH cells showed no evidence of Foxp3 expression. This further indicates that TFH cells described here did not comprise T regulatory cells or T follicular regulatory cell subsets [21].

Expression of FR4 and CD73 has also been reported on anergic, autoreactive T cells compared to functional T cells [43]. Additionally, FR4 is also highly expressed by exhausted CD8 T cells in chronic viral infection but not on effectors or fully functional memory CD8 T cells (our unpublished observations). These data point to a potential role of chronic TCR simulation in regulating FR4 expression.

Notably, expression of both FR4 and CD73 was maintained on CXCR5+ cells at the memory time point. The continued expression of FR4 on memory CXCR5+ cells distinguishes it from other TFH cell markers, which are significantly down-regulated on CXCR5+ cells subsequent to their exit from the germinal center. Thus, FR4 could be used together with CXCR5 to identify, sort, and study putative memory TFH cells.

At present, we do not fully understand the utility of FR4 and CD73 as markers for human TFH cells. The unavailability of monoclonal antibody against the human homolog of FR4 precludes its identification in human TFH cells. Our preliminary studies in human peripheral blood show that CD73 is not expressed by circulating CXCR5+ CD4 T cells during steady state. More detailed studies, in peripheral blood and lymphoid compartments including tonsils and lymph nodes, are needed to investigate the dynamics of CD73 expression on CD4 T cell subsets after vaccination and infection.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that FR4 and CD73 are novel markers to identify TFH cells. These observations emphasize the need for understanding the role of folate and adenosine metabolism, and how FR4 and CD73 intersect with these pathways in regulating TFH function. Mechanistic insights into folate and purinergic pathways as they relate to TFH cell development and function may provide novel strategies to optimize TFH cell responses to vaccinations and/or control TFH cell responses in B cell-mediated disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, virus, and adoptive transfers

Four to 6-wk-old C57BL/6 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). SMARTA transgenic mice with CD4 T cells bearing the GP61–80 specific T-cell receptor were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice bearing either Thy1.1 or Ly5.1 congenic cell-surface markers, as previously described [44]. Mice were housed in cages and maintained on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle at the Division of Animal Resources at Emory University. SMARTA chimeric mice were generated by adoptively transferring naive SMARTA splenocytes into naive C57BL/6 mice by intravenous injection. The number of antigen-specific cells transferred varied between 1×103 and 1×106 among experiments as indicated in the text and figure legends. Chimeric mice were infected with 2×105 PFU of LCMV Armstrong by intra-peritoneal injection. LCMV Armstrong virus was propagated, titers were determined, and virus was used as previously described [45]. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University.

Antibodies, flow cytometric analysis, and sorting

All data unless otherwise specified were obtained from analysis of spleen. Single-cell suspensions were prepared in RPMI containing 10% FBS by mechanical disruption of spleens. Red blood cells were lysed in 0.83% ammonium chloride. 106 cells were stained in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% FBS (FACS buffer) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for CD4 (RM4-5), Thy 1.1 (OX7), Ly 5.1 (A20), Ly6C (AL-21), GL7, ICOS (7E.17G9), T-bet (O4-46), Bcl-6 (K112-91), Fas (Jo2), CXCR5 (2G8), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), TNF-α (MP6-XT22), IL-2 (JES6-5H4) from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA); CD44 (IM7), PD-1 (RMP-130), FR4 (12A5), CD73 (TY/11.8), SLAM(TC15-12F12.2) from Biolegend (San Diego, CA); Foxp3 (FJK-16s from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Dead cells were excluded from analysis based on staining for Live/Dead Aqua dead cell stain from Molecular Probes, Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). CXCR5 staining was performed as previously described [7]. Bcl-6, T-bet, and Foxp3 stains were performed after cells were stained for surface antigens followed by permeabilization/fixation using the Foxp3 kit and protocol, followed by intracellular staining. Prior to intracellular staining for cytokines, splenocytes were stimulated with GP61–80 peptide for 5 hours in the presence of brefeldin A (Golgi Plug), then fixed and permeabilized with CytoFix / CytoPerm (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were acquired on a FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software v 9.3.1 (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Cell sorting was performed using a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences). Prior to sorting, cells were pre-purified using anti-CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Microarray hybridization and analysis

Naive and day 12 FR4lo, CXCR5− and FR4hi, CXCR5+ Ly5.1+, SMARTA CD4 T cells were FACS sorted and RNA was isolated from cells using the QIAGEN RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) followed by DNAse treatment to remove contaminating DNA. RNA was quantified using the Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer and analyzed for integrity using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer at the Vanderbilt Genome Sciences Resource. Samples with optimal RNA integrity number and RNA quality score were amplified using a kit from NuGEN, Inc, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Following amplification, RNA was prepared for microarray analysis and hybridized in triplicate to Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays containing 45,000 sets of 11 to 25-mer oligomers, representing 39,000 mouse transcripts (34,000 are annotated as well-defined genes). Hybridized cRNA was detected using streptavidin coupled to phycoerythrin and visualized by the Affymetrix 3000 7G laser scanner.

For statistical analysis, CEL files (raw Affymetrix data) were processed using R (R version 2.11.1). Quality control was performed by viewing the images in R and using the bioconductor packages affyPLM and affy (R version 2.11.1, affyPLM version 1.28.5, affy version 1.26.1) [46]. The raw CEL files were then normalized with quantile normalization and summarized using robust multi-array analysis (RMA) [47]. Differentially regulated genes between FR4hi, CXCR5+ and FR4lo, CXCR5− subsets were identified using significance analysis of microarrays (SAM- siggenes package version 1.22.0), which found 711 differentially regulated genes with a false discovery rate of 0.08 and a fold change of at least 2-fold [48]. The data were annotated with Affymetrix Mouse 430 2.0 annotation files (version 30).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by the two-tailed Student t test using Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). A p value #0.05 was used to determine significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Karaffa and S. Durham for FACS sorting at the Emory University School of Medicine Flow Cytometry Core Facility. The authors acknowledge Carl Davis, Benjamin Youngblood, Andreas Wieland, and Reben Rahman for helpful suggestions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01A1030048, U19A1057266, PO 5-24906 (to R.A). All microarray experiments were performed in the Vanderbilt Genome Sciences Resource. The Vanderbilt Genome Sciences Resource is supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485), the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Center (P30 DK58404) and the Vanderbilt Vision Center (P30 EY08126).

Abbreviations

- TFH cells

T follicular helper cells

- FR4

folate receptor 4

- PD-1

programmed cell death 1

- CXCR5

chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 5

- LCMV

lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, Ellwart J, Sallusto F, Lipp M, Forster R. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1545–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berek C, Berger A, Apel M. Maturation of the immune response in germinal centers. Cell. 1991;67:1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90289-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linterman MA, Rigby RJ, Wong RK, Yu D, Brink R, Cannons JL, Schwartzberg PL, Cook MC, Walters GD, Vinuesa CG. Follicular helper T cells are required for systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2009;206:561–576. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1553–1562. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes NM, Allen CD, Lesley R, Ansel KM, Killeen N, Cyster JG. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J Immunol. 2007;179:5099–5108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Tanaka S, Matskevitch TD, Wang YH, Dong C. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, Yusuf I, Eto D, Barnett B, Dent AL, Craft J, Crotty S. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linterman MA, Beaton L, Yu D, Ramiscal RR, Srivastava M, Hogan JJ, Verma NK, Smyth MJ, Rigby RJ, Vinuesa CG. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med. 207:353–363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bossaller L, Burger J, Draeger R, Grimbacher B, Knoth R, Plebani A, Durandy A, Baumann U, Schlesier M, Welcher AA, Peter HH, Warnatz K. ICOS deficiency is associated with a severe reduction of CXCR5+CD4 germinal center Th cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:4927–4932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yusuf I, Kageyama R, Monticelli L, Johnston RJ, Ditoro D, Hansen K, Barnett B, Crotty S. Germinal center T follicular helper cell IL-4 production is dependent on signaling lymphocytic activation molecule receptor (CD150) J Immunol. 185:190–202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Moser B. Cutting edge: induction of follicular homing precedes effector Th cell development. J Immunol. 2001;167:6082–6086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardtke S, Ohl L, Forster R. Balanced expression of CXCR5 and CCR7 on follicular T helper cells determines their transient positioning to lymph node follicles and is essential for efficient B-cell help. Blood. 2005;106:1924–1931. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayamada S, Kanno Y, Takahashi H, Jankovic D, Lu KT, Johnson TA, Sun HW, Vahedi G, Hakim O, Handon R, Schwartzberg PL, Hager GL, O'Shea JJ. Early Th1 Cell Differentiation Is Marked by a Tfh Cell-like Transition. Immunity. 35:919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi YS, Kageyama R, Eto D, Escobar TC, Johnston RJ, Monticelli L, Lao C, Crotty S. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 34:932–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crotty S. Follicular Helper CD4 T Cells (T(FH)) Annu Rev Immunol. 29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall HD, Chandele A, Jung YW, Meng H, Poholek AC, Parish IA, Rutishauser R, Cui W, Kleinstein SH, Craft J, Kaech SM. Differential expression of Ly6C and T-bet distinguish effector and memory Th1 CD4(+) cell properties during viral infection. Immunity. 35:633–646. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hale JS, Youngblood B, Latner DR, Mohammed AU, Ye L, Akondy RS, Wu T, Iyer SS, Ahmed R. Distinct memory CD4+ T cells with commitment to T follicular helper- and T helper 1-cell lineages are generated after acute viral infection. Immunity. 2013;38:805–817. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi T, Hirota K, Nagahama K, Ohkawa K, Takahashi T, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of immune responses by antigen-specific regulatory T cells expressing the folate receptor. Immunity. 2007;27:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poholek AC, Hansen K, Hernandez SG, Eto D, Chandele A, Weinstein JS, Dong X, Odegard JM, Kaech SM, Dent AL, Crotty S, Craft J. In vivo regulation of Bcl6 and T follicular helper cell development. J Immunol. 185:313–326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sage PT, Francisco LM, Carman CV, Sharpe AH. The receptor PD-1 controls follicular regulatory T cells in the lymph nodes and blood. Nat Immunol. 14:152–161. doi: 10.1038/ni.2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Tian J, Picarella D, Domenig C, Zheng XX, Sabatos CA, Manlongat N, Bender O, Kamradt T, Kuchroo VK, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Coyle AJ, Strom TB. Tim-3 inhibits T helper type 1-mediated auto- and alloimmune responses and promotes immunological tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X, Shimaoka T, Kojo S, Harada M, Watarai H, Wakao H, Ohkohchi N, Yonehara S, Taniguchi M, Seino K. Cutting edge: critical role of CXCL16/CXCR6 in NKT cell trafficking in allograft tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;175:2051–2055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monticelli LA, Yang Y, Knell J, D'Cruz LM, Cannarile MA, Engel I, Kronenberg M, Goldrath AW. Transcriptional regulator Id2 controls survival of hepatic NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19461–19466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908249106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renthal NE, Chen CC, Williams KC, Gerard RD, Prange-Kiel J, Mendelson CR. miR-200 family and targets, ZEB1 and ZEB2, modulate uterine quiescence and contractility during pregnancy and labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:20828–20833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008301107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutishauser RL, Kaech SM. Generating diversity: transcriptional regulation of effector and memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Immunol Rev. 235:219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiegelstein O, Eudy JD, Finnell RH. Identification of two putative novel folate receptor genes in humans and mouse. Gene. 2000;258:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson LF, Ruedi JM, Glass A, Moldenhauer G, Moller P, Low MG, Klemens MR, Massaia M, Lucas AH. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored lymphocyte differentiation antigen ecto-5'-nucleotidase (CD73) Tissue Antigens. 1990;35:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1990.tb01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fazilleau N, Eisenbraun MD, Malherbe L, Ebright JN, Pogue-Caley RR, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Lymphoid reservoirs of antigen-specific memory T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:753–761. doi: 10.1038/ni1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Hatakeyama J, Ohsawa R. Roles of bHLH genes in neural stem cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, Huang GW, Zhang XM, Ren DL, J XW. Folic Acid supplementation stimulates notch signaling and cell proliferation in embryonic neural stem cells. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 47:174–180. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mashiyama ST, Courtemanche C, Elson-Schwab I, Crott J, Lee BL, Ong CN, Fenech M, Ames BN. Uracil in DNA, determined by an improved assay, is increased when deoxynucleosides are added to folate-deficient cultured human lymphocytes. Anal Biochem. 2004;330:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blount BC, Mack MM, Wehr CM, MacGregor JT, Hiatt RA, Wang G, Wickramasinghe SN, Everson RB, Ames BN. Folate deficiency causes uracil misincorporation into human DNA and chromosome breakage: implications for cancer and neuronal damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3290–3295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courtemanche C, Elson-Schwab I, Mashiyama ST, Kerry N, Ames BN. Folate deficiency inhibits the proliferation of primary human CD8+ T lymphocytes in vitro. J Immunol. 2004;173:3186–3192. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, Wang YH, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ames BN, Wakimoto P. Are vitamin and mineral deficiencies a major cancer risk? Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:694–704. doi: 10.1038/nrc886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resta R, Yamashita Y, Thompson LF. Ecto-enzyme and signaling functions of lymphocyte CD73. Immunol Rev. 1998;161:95–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobie JJ, Shah PR, Yang L, Rebhahn JA, Fowell DJ, Mosmann TR. T regulatory and primed uncommitted CD4 T cells express CD73, which suppresses effector CD4 T cells by converting 5'-adenosine monophosphate to adenosine. J Immunol. 2006;177:6780–6786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schenk U, Frascoli M, Proietti M, Geffers R, Traggiai E, Buer J, Ricordi C, Westendorf AM, Grassi F. ATP inhibits the generation and function of regulatory T cells through the activation of purinergic P2X receptors. Sci Signal. 4:ra12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandapathil M, Hilldorfer B, Szczepanski MJ, Czystowska M, Szajnik M, Ren J, Lang S, Jackson EK, Gorelik E, Whiteside TL. Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Biol Chem. 285:7176–7186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 11:201–212. doi: 10.1038/nri2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Airas L, Jalkanen S. CD73 mediates adhesion of B cells to follicular dendritic cells. Blood. 1996;88:1755–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez RJ, Zhang N, Thomas SR, Nandiwada SL, Jenkins MK, Binstadt BA, Mueller DL. Arthritogenic Self-Reactive CD4+ T Cells Acquire an FR4hiCD73hi Anergic State in the Presence of Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 188:170–181. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oxenius A, Bachmann MF, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Virus-specific MHC-class II-restricted TCR-transgenic mice: effects on humoral and cellular immune responses after viral infection. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:390–400. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<390::AID-IMMU390>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed R, Salmi A, Butler LD, Chiller JM, Oldstone MB. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J Exp Med. 1984;160:521–540. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bolstad BM, Collin F, Brettschneider J, Simpson K, Cope L, Irizarry RA, Speed TP. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.