Abstract

Background

The process of identifying molecules that regulate angiogenesis is critical to the success of candidate therapies for ocular neovascular disease. The purpose of the study was to determine the pattern of expression for integrins and their colocalization with endothelium in membranes from proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR).

Methods

Clinically categorized membranes were collected from vitreoretinal surgery. A double immunohistochemical staining procedure was used to identify the presence and colocalization of integrins and endothelium. Five integrins were examined.

Results

Endothelial markers were robust in all 4 active-stage PDR membranes but absent in the fibrotic-stage PDR membrane. The expression of αvβ3 and β3 integrins on endothelial cells was observed with low to moderate intensity. The expression of α1β1 and α2β1 was moderate but was not colocalized with endothelial cells in active-stage PDR membranes. Integrin αvβ5 was not evident in any of the samples used in this study.

Interpretation

The results suggest an essential role of integrins αvβ3 and β3 in the pathogenesis of PDR. It is suggested that αvβ3 and β3 are preferred candidate targets for therapeutic development.

Keywords: proliferative diabetic retinopathy, integrins, neovascularization, immunohistochemistry, antagonists

Diabetic retinopathy has historically been one of the main causes of acquired blindness in developing nations. Currently, diabetic retinopathy remains a common cause of acquired blindness despite the development of laser treatment for patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). In developed nations approximately 12,000 to 24,000 new cases of PDR occur each year that result in blindness.1,2

PDR is conventionally defined as a disease that requires the presence of newly formed blood vessels or fibrous tissue, or both, arising from the retina or optic disc and extending along the inner surface of the retina, the disc, or into the vitreous cavity.2 Normal retinal capillaries consist of endothelial cells lying on the basement membrane surrounded by pericytes. Tight junctions are found between endothelial cells at the point of contact and are largely responsible for the blood–retinal barrier.1 Therefore, circulation proteins do not normally travel through the walls of retinal blood vessels unless they are transported specifically via transport molecules. The basement membrane is composed of a variety of proteins produced by endothelial cells, including collagen, laminin, and heparin sulfate proteoglycan. The basement membrane plays an important role in regulating vascular permeability and the division and migration of endothelial cells. Pericytes are also responsible for the control of vessel diameter and, hence, blood flow, and may also be involved in the control of endothelial cell growth.1

In diagnosed cases of PDR, physiological changes occur resulting in the loss of pericytes and endothelial cells, endothelial cell dysfunction, and the thickening of the basement membrane. These resulting biological and chemical changes can lead to an increase in capillary permeability and the leakage of fluids into the retina. There is an eventual closure of retinal capillaries and subsequent retinal ischemia. Earlier studies have shown that ischemic retinal tissues promote the release of growth factors resulting in neovascularization. 1 In PDR, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is believed to play a major role in mediating active intraocular neovascularization in patients with diseases associated with retinal ischemia.3–5 Currently, studies involving pericytes, the expression of VEGF, and specific integrins indicate that pericytes show an angiogenic program of gene expression involving the upregulation of many molecules, including VEGF and the integrin subunit α5.6

In vitro and in vivo studies show that cells of virtually all types lay down a network of proteins and proteoglycans on which to adhere and develop. This network is called the extracellular matrix (ECM) and is composed of fibronectin, laminin, and collagen.7,8 The role of the ECM is not only to anchor cells but to also to affect differentiation and behaviour. Intracellular signaling is relayed from the extracellular milieu to the intracellular regulatory systems via surface integrins, subsequently causing physiological changes to the cell. Most integrins bind several different ligands.7

Integrins are heterodimeric, transmembrane glycoproteins consisting of 1 alpha subunit and 1 beta subunit.7 They are cell adhesion molecules and are receptors of ECM components (Table 1). Integrins facilitate cellular adhesions to and migration on ECM proteins found in intercellular spaces and basement membranes. Ligation of integrins by their ECM component induces cascades of intracellular signals, including tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase, increases in intracellular pH and calcium, inositol lipid synthesis, and the synthesis of cyclins. Integrins also regulate cell entry and withdrawal from the cell cycle.9 These proteins help regulate processes (e.g., cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation) that are also involved in the pathogenesis of proliferative retinal diseases such as PDR.10 Angiogenesis depends on growth factors and is also influenced by cell adhesion molecules. Hence, involvement of both growth factors and integrins is a determining factor in the pathogenesis of PDR.4,9

Table 1.

Integrin antibodies* and ligands

| Antigen | Dimer(s) | Type | Possible ligand(s) | Types of cell(s) expressing integrin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | α1β1 | Polyclonal | Collagen, laminin, fibronectin, fibrinogen | Activated T-cells, monocytes, melanoma cells, smooth muscle cells |

| α2AB1936 | α2β1 | Polyclonal | Collagen I and IV, laminin | B and T lymphocytes, platelets, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, melanoma cells |

| β3AB1932 | αvβ3LM609 | Monoclonal | Vitronectin, fibrinogen, VWF, fibronectin, OP, BSPI, Tsp | Endothelial cells, platelets, monocytes |

| αIIbβ3 | Monoclonal | Fibrinogen, fibronectin, VWF, vitronectin | Platelets | |

| β5 | αvβ5P1F6 | Monoclonal | Vitronectin | Hepatoma cells, fibroblasts, carcinoma cells |

Obtained from Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.

Note: VWF, von Willebrand factor; OP, osteopontin; BSPI, bone sialoprotein 1; Tsp, thrombospondin.

Integrin binding produces changes in cell physiology and behaviour. Hence, cell behaviour (e.g., angiogenesis) can be influenced by changing ECM components, blocking integrin interactions with extracellular substrates, blocking integrin intracellular signaling, or decreasing production of specific integrins.1,11 With the use of a panel of 5 antibodies against integrins and 2 antibodies against endothelial cells, double labeling studies were undertaken on surgical specimens of PDR membranes. During neovascularization several integrin family members have been implicated in regulating endothelial cell function, including α1β1, α2β1, α41β1, α5β1, αvβ3, and αvβ5.12 The purpose of this study was to build on existing findings that αvβ3 and αvβ5 play a key role in PDR13 and to compare the results with those of another neovascular eye disease, choroidal neovascularization (CNV), associated with age-related macular degeneration.14

The process of identifying molecules that regulate angiogenesis is critical to the success of candidate therapies for ocular neovascular disease. The prevention of integrin–ligand interaction suppresses cellular growth or the induction of apoptotic cell death.9 Knowledge of the specific integrin associated with PDR may help develop integrin antagonists to prevent the progression of the disease process.

Methods

Tissue preparation

Four membranes at advanced PDR ETDRS (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study)15 stage 81 were collected from eyes by vitreoretinal surgery. A fifth, non-proliferative, fibrotic membrane was also used for comparison. Methods for securing human tissue were humane and included proper written informed consent, which complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The procedures were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. The membranes were set in molds using an optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, Calif.) and were stored at −80 °C.

PDR membranes were thawed at −20 °C for 30 minutes before sectioning and then maintained at this temperature during sectioning. The membranes were serially sectioned at 6 μm thickness using a Frigocut 2800 N Cryostat (Reichert-Jung, Chicago, Ill.) and mounted on glass slides. These slides were then stored at −20 °C until further processing.

Immunohistochemical staining

A double immunohistochemical staining procedure was used to identify endothelial cells and the presence of integrins. The colocalization of the integrin subtype to different cell types in this study will provide important information for the development of specific therapeutics targeted to specific cell types and (or) integrin subtypes.

The slides were removed from −20°C conditions and were left to dry for 20 minutes at room temperature. The sections on the slides were then circled with a PAP Pen (Daido Sangyo Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) and fixed in acetone for 10 minutes. Following this, the slides were washed in a mixture of fresh phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 5 minutes. The sections were then treated with 0.3% H2O2 for 15 minutes to remove endogenous peroxidases. After the allotted time, the sections were blocked for nonspecific binding in a solution of PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 5% normal horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) for 20 minutes.

Sections were incubated with a solution containing 2 primary antibodies for 1 hour. The first antibody was targeted against 1 of the integrins, and the second was specific for the endothelial cell. The commercially available antibodies were diluted with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Positive controls were designed using tonsil tissue according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The presence of positive and negative controls for staining are essential for determining specificity. Omission of the primary antibody was the negative control.

Five different primary antibodies against integrins were used (Table 1). Antibodies were obtained from Chemicon Inc (Temecula, Calif.) and consisted of rabbit anti-human integrin β3AB1932 (1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-human integrin α1 (1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-human integrin α2AB1936 (1:100), mouse anti-human integrin αvβ3 Clone: LM609 (1:100), and mouse anti-human integrin αvβ5 clone P1F6 (1:500). Two antibodies directed against endothelial cells, polyclonal rabbit von Willebrand Factor (VWF) (Chemicon Inc), and monoclonal mouse CD31 clone JC70A (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), both at a dilution of 1:200, were used.

After incubation with the primary antibodies, the slides were washed 3 times over 15 minutes with PBS. This was followed by the application of standard fluorescent secondary antibodies, anti-rabbit Alexa-488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Ore.) and anti-mouse Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories Inc, West Grove, Pa.), both at a dilution of 1:400 with PBS for 30 minutes. Next, slides were washed 3 times over 15 minutes with PBS. To preserve the luminosity of the fluorescent secondary antibodies, the slides were mounted with SlowFade (Molecular Probes) and then covered with No 1.5 coverslip glass.

Several sections from each membrane were also stained for hematoxylin and eosin to allow bright-field visualization of the cellular content and comparison with immunohistochemical staining.

Analysis

Tissue sections were analyzed using a Zeiss Inverted Axiovert 200M confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss-LSM 510 META, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Random fields of the sections were imaged at ×20 magnification. The sections were scanned with laser wavelengths of 488 nm (Alexa-488 emission green) and 543 nm (Cy3 emission red). The gain was adjusted accordingly for each wavelength to ensure that background fluorescence was minimal. If the field had 10 or more immunoreactive sites (visually seen as “dots” of fluorescence, e.g., see arrow in Fig. 1K), it was classified as +++, indicating high-intensity expression. If the field had 6–10 immunoreactive sites it was classified as ++ for moderate-intensity staining, and a field of 1–5 immunoreactive sites was classified at + for low-intensity staining. If the field indicated no expression of fluorescence, it was classified as −. Double staining was identified in cells emitting both green and red fluorescence, which appeared yellow.

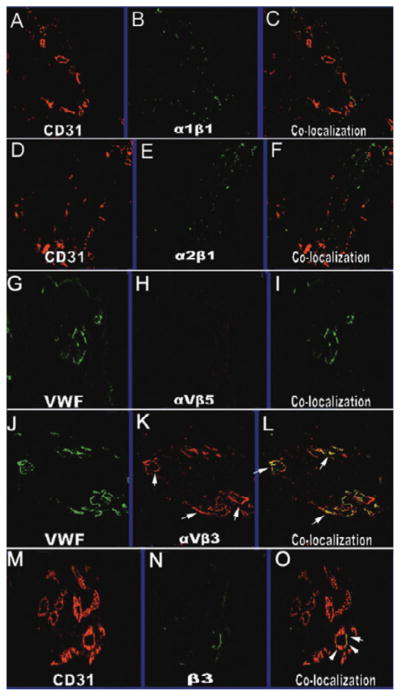

Fig. 1.

Confocal images of integrins and endothelial cell expression at ×20 magnification. Immunostaining for endothelial cell markers CD31 (A,D, and M) or VWF (G and M) and integrin staining (B, E, H, K, and N). The corresponding overlaid images of endothelial and integrin staining within a tissue are shown in C, F, I, L, and O. Staining for β3 integrin (N) showed colocalization with CD31 (M) as demonstrated by yellow signaling (O, arrows). Similar to the staining for β3, staining for the heterodimer αvβ3 (K, arrows) with VWF (J) also demonstrated colocalization (L, arrows). The staining for α1β1 (B) and α2β1 (E) was not colocalized with endothelial cells as identified by CD31 (A and D). The staining for αvβ5 was not observed (H).

Results

Endothelial markers CD31 and VWF were strongly stained in all PDR membranes (Table 2). The data suggest that all 4 membranes were undergoing neovascular response at the time of surgical removal (Fig. 1). The 1 late-stage fibrotic membrane used for comparison was negative for CD31 and VWF (image not shown).

Table 2.

Summary of patient characteristics and integrin staining on PDR membranes

| Number | Age, yr | Sex | Endothelial staining | β3 | αVβ3 | αVβ5 | α1β1 | α2β1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDR 1 | 72 | M | +++ | ++/− | +/+ | −/− | ++/− | +/− |

| PDR 2 | 66 | F | +++ | +/− | +++/++ | −/− | n/a | ++/− |

| PDR 3 | 67 | M | +++ | ++/++ | ++/++ | −/− | ++/− | ++/− |

| PDR 4 | 59 | F | +++ | ++/++ | +++/++ | −/− | ++/− | +/− |

| PDR 5 | 65 | M | − | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

| Tonsil | (control) | +++ | +/− | ++/− | ++/− | +/+ | +/− |

Note: PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; n/a, tissue unavailable; integrin and endothelial cell staining intensities: +++ high intensity (10 or more dots); ++ moderate intensity staining (6–10 dots); + low intensity staining (1–5 dots); − absence of staining.

Expression of α1β1

Immunohistochemical staining for α1β1 integrin was observed to be present in all specimens with moderate intensity. However, colocalization of α1β1 integrin and CD31 was not observed. In the control tonsil tissue, α1β1 integrin expression was at low intensity, and the expression of CD31 was at high intensity. Colocalization of both α1β1 integrin and CD31 was observed with low intensity in control tonsil tissue (Fig. 1B, 1C).

Expression of α2β1

The expression of integrin α2β1 was observed in all specimens with low to moderate intensities. Colocalization with α2β1 integrin and the endothelial cell marker CD31 was not observed. Colocalization of both these markers was also not observed in the control tonsil tissue (Fig. 1E, 1F).

Expression of αvβ5

The expression of integrin αvβ5 was not observed in any of the specimens (Fig. 1H, 1I). In the control tonsil tissue, αvβ5 integrin staining was seen with moderate intensity; however, colocalization of VWF and αvβ5 integrin was not seen.

Expression of αvβ3

Immunohistochemical staining of αvβ3 was observed in all specimens with varying intensities from high to low (Fig. 1K). Colocalization of the αvβ3 integrin and CD31 was seen with low to moderate intensity (Fig. 1L). The control tonsil tissue expressed αvβ3 with moderate intensity and VWF with high intensity. However, colocalization of αvβ3 and VWF was not observed.

Expression of β3

Expression of the integrin β was seen with low to moderate intensities in all specimens (Fig. 1N). Colocalization of both CD31 and β3 integrin was observed with moderate intensity in PDR 3 and PDR 4 (Fig. 1O). However, colocalization was not observed in the remaining specimens PDR 1 and PDR 2. The control tissue expressed β3 integrin with low intensity and CD31 with high intensity; colocalization of the two molecules was not observed.

Interpretation

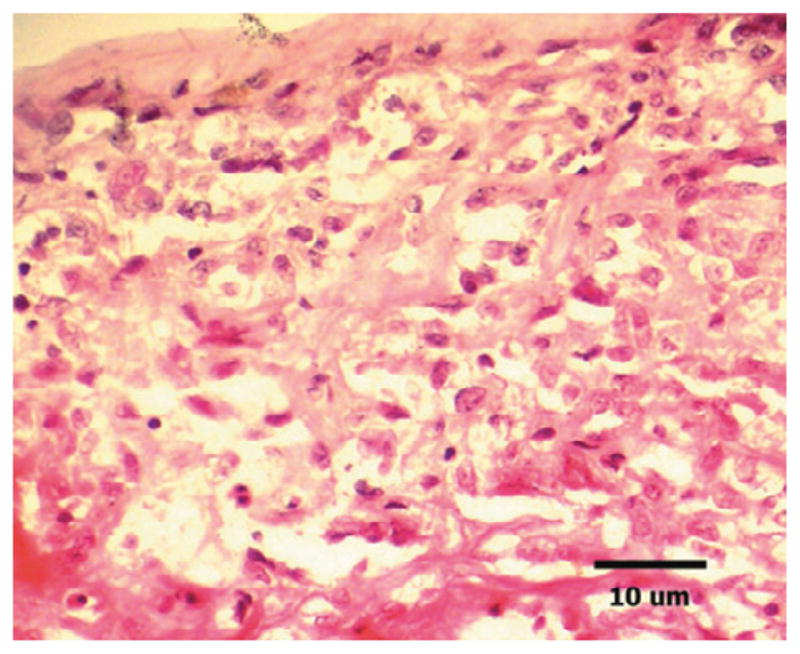

The present study examined the expression of 5 integrins on endothelial cells of actively proliferating PDR membranes. Our results show that integrin family members αvβ3 and β3 colocalize with endothelial cells, confirming an earlier report on αvβ3, and adding new information regarding β3 in PDR. The expression of 5 integrins did not present in fibrous membranes because these membranes do not have vessels and are composed of only very few cells. It is most probable that nonvascular cell types in the PDR membranes might express integrins (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Light micrograph of a cryostat section (6 μm thickness) taken from membrane of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) obtained during vitrectomy, stained with hematoxylin–eosin. Note several round, cell nuclei (purple hematoxylin), nonvascular cell types in the PDR membranes. (Original magnification ×20, scale bar, 10 μm.)

The expression of αvβ3 observed in this study is consistent with an earlier study by Friedlander.13 Studies of αvβ3 antagonists/antibodies and their ability to inhibit angiogenesis have shown that antagonists targeted at αvβ3 suppress angiogenesis but do not harm pre-existing vessels in various models of angiogenesis.13,16–19 However, not all aspects of angiogenesis may be dependent on the expression of αvβ3. It has been suggested that other integrin family members may compensate for the loss of αv integrin or may play a more essential role in the angiogenic response.20–22

Our finding of β3’s role in PDR is novel and places β as a candidate integrin that may also play a prominent role in the angiogenic response in PDR. Interestingly, β3 was demonstrated on endothelial cells in surgical membranes removed from patients with CNV associated with age-related macular degeneration, suggestive of a broader role in neovascular diseases of the eye.14 Little is known of the mechanism of action of β3 and angiogenesis. However, a recent study by Miller et al.23 showed that retinal endothelial cells in hyperglycemic conditions upregulate β3 ligand binding leading to an increase in its activation state, as measured by tyrosine phosphorylation, contributing to an enhanced responsiveness of retinal endothelial cells to insulin growth factor-I. In future, antagonists to the β3 integrin subunit may be used in models to assess its efficacy in inhibiting the angiogenic response.

This work also revealed that αvβ5 expression was not present in endothelial cells of the PDR membranes studied here, which is at odds with earlier reports.13,24–26 The differences in findings may be due to differences in the specificities of the antibodies or in individual variations among surgical specimens. The integrin αvβ5 was observed on both nonvascular and vascular areas with some expression colocalized on endothelial cells in PDR and CNV.26 In a recent study of CNV membranes, αvβ5 did colocalize with endothelial cells.14 More research is needed to fully grasp the extent of the role that αvβ5 may play in both PDR and CNV, and other ocular neovascular diseases.

The integrins α1β1 and α2β1 do not appear to be associated with endothelial cells in the PDR membranes studied here. No other studies have looked at α1β1 and α2β1 in ocular tissues. However, in other systems, α1β1 and α2β1were expressed with moderate intensity, but not colocalized with endothelial cells.27 It is most probable that other cell types in the PDR membranes may express these integrins.

Previous studies have demonstrated that potential exists for therapeutic approaches toward integrin antagonists and antibodies and their correlation with the inhibition of angiogenesis. Antagonists targeted at αvβ3 integrin have the ability to suppress angiogenesis but cause no effects on pre-existing vessels in various models of angiogenesis.13,16,17 The results of this study have demonstrated the colocalized expression of αvβ3 integrin and β3 integrin subunit with endothelial cells. The presence of these integrins on endothelial cells may play a role in the regulation of angiogenesis during PDR. Consequently, future anti-angiogenic treatments of PDR may involve integrin antagonists or antibodies.

References

- 1.Speicher MA, Danis RP, Criswell M, Pratt L. Pharmacologic therapy for diabetic retinopathy. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2003;8:239–50. doi: 10.1517/14728214.8.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan SJ. Retina. 4. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1480–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412013312203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byzova TV, Goldman CK, Pampori N, et al. A mechanism for modulation of cellular responses to VEGF: activation of the integrins. Mol Cell. 2000;6:851–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senger DR, Claffey KP, Benes JE, Perruzzi CA, Sergiou AP, Detmar M. Angiogenesis promoted by vascular endothelial growth factor: regulation through alpha1beta1 and alpha2beta1 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13612–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kale S, Hanai J, Chan B, et al. Microarray analysis of in vitro pericyte differentiation reveals an angiogenic program of gene expression. FASEB J. 2005;19:270–1. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1604fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brem RB, Robbins SG, Wilson DJ, et al. Immunolocalization of integrins in the human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3466–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliceiri BP. Integrin and growth factor receptor crosstalk. Circ Res. 2001;89:1104–10. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varner JA, Brooks PC, Cheresh DA. The integrin alpha V beta 3: angiogenesis and apoptosis. Cell Adhes Commun. 1995;3:367–74. doi: 10.3109/15419069509081020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robbins SG, Brem RB, Wilson DJ, et al. Immunolocalization of integrins in proliferative retinal membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3475–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senger DR, Ledbetter SR, Claffey KP, Papadopoulos-Sergiou A, Peruzzi CA, Detmar M. Stimulation of endothelial cell migration by vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor through cooperative mechanisms involving the alphav-beta3 integrin, osteopontin, and thrombin. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:293–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eliceiri BP, Cheresh DA. Adhesion events in angiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:563–8. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedlander M, Brooks PC, Shaffer RW, Kincaid CM, Varner JA, Cheresh DA. Definition of two angiogenic pathways by distinct alpha v integrins. Science. 1995;270:1500–2. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui JZ, Mabeley D, Samad A, et al. Expression of integrins on human choroidal neovascular membranes. Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; 2006. p. Abstract 866. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association. Diabetic retinopathy. Clin Diabetes. 2001;19:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks PC, Clark RA, Cheresh DA. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science. 1994;264:569–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks PC, Montgomery AM, Rosenfeld M, et al. Integrin alpha v beta 3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell. 1994;79:1157–64. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drake CJ, Cheresh DA, Little CD. An antagonist of integrin alpha v beta 3 prevents maturation of blood vessels during embryonic neovascularization. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2655–61. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.7.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danis RP, Ciulla TA, Criswell M, Pratt L. Anti-angiogenic therapy of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:395–407. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bader BL, Rayburn H, Crowley D, Hynes RO. Extensive vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and organogenesis precede lethality in mice lacking all alpha v integrins. Cell. 1998;95:507–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81618-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodivala-Dilke KM, McHugh KP, Tsakiris DA, et al. Beta3-integrin-deficient mice are a model for Glanzmann thrombasthenia showing placental defects and reduced survival. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:229–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Li C, Baciu PC. Expression of integrins and MMPs during alkaline-burn-induced corneal angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:955–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller EC, Capps BE, Sanghani RR, Clemmons DR, Maile LA. Regulation of IGF-I signaling in retinal endothelial cells by hyperglycemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3878–87. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casaroli Marano RP, Preissner KT, Vilaró S. Fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin and their receptors at newly-formed capillaries in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 1995;60:5–17. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luna J, Tobe T, Mousa SA, Reilly TM, Campochiaro PA. Antagonists of integrin alpha v beta 3 inhibit retinal neovascularization in a murine model. Lab Invest. 1996;75:563–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedlander M, Theesfeld CL, Sugita M, et al. Involvement of integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 in ocular neovascular diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9764–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damjanovich L, Albelda SM, Mette SA, Buck CA. Distribution of integrin cell adhesion receptors in normal and malignant lung tissue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:197–206. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]