Abstract

The mechanism by which the Mn-containing oxygen evolving complex (OEC) produces oxygen from water has been of great interest for over 40 years. This review focuses on how X-ray spectroscopy has provided important information about the structure of this Mn complex and its intermediates, or S-states, in the water oxidation cycle. X-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopy and high-resolution Mn Kβ X-ray emission spectroscopy experiments have identified the oxidation states of the Mn in the OEC in each of the intermediate S-states, while extended X-ray absorption fine structure experiments have shown that 2.7 Å Mn–Mn di-μ-oxo and 3.3 Å Mn–Mn mono-μ-oxo motifs are present in the OEC. X-ray spectroscopy has also been used to probe the two essential cofactors in the OEC, Ca2+ and Cl−, and has shown that Ca2+ is an integral component of the OEC and is proximal to Mn. In addition, dichroism studies on oriented PS II membranes have provided angular information about the Mn–Mn and Mn–Ca vectors. Based on these X-ray spectroscopy data, refined models for the structure of the OEC and a mechanism for oxygen evolution by the OEC are presented.

Keywords: Photosystem II, Oxygen evolving complex, Extended X-ray absorption fine structure, X-ray absorption near-edge structure, Electron paramagnetic resonance, S-states, Oxygen evolution, X-ray emission spectroscopy

1. Introduction

The oxidation of H2O to O2 by the Mn-containing oxygen evolving complex (OEC) in the chloroplasts [1], and the reduction of O2 to H2O by cytochrome c oxidase in the mitochondria [2] form the important cycle of dioxygen metabolism that is essential to both plant and animal life on earth (Eq. 1).

| (1) |

Oxygen is relatively abundant in the atmosphere primarily because of its constant regeneration by photosynthetic water oxidation by the OEC. The OEC of the photosynthetic apparatus that catalyzes the forward reaction shown in Eq. 1 contains a cluster of four Mn atoms (reviewed in [1,3–5]). In addition to Mn, Cl− and Ca2+ are essential cofactors that are required for activity [6,7]. The OEC cycles through a series of five intermediate states, Si (i =0–4), where i represents the number of oxidizing equivalents stored on the OEC. This process is driven by the energy of four successive photons absorbed by the pigment P680 of the photosystem II (PS II) reaction center [8]. The Mn complex in the OEC couples the four-electron oxidation of water with the one-electron photochemistry occurring at the PS II reaction center by acting as the locus of charge accumulation (Fig. 1).

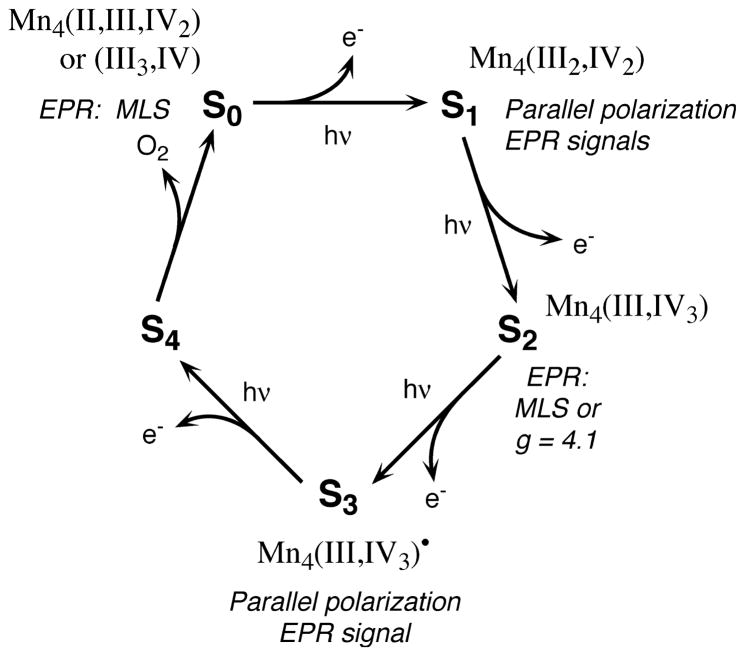

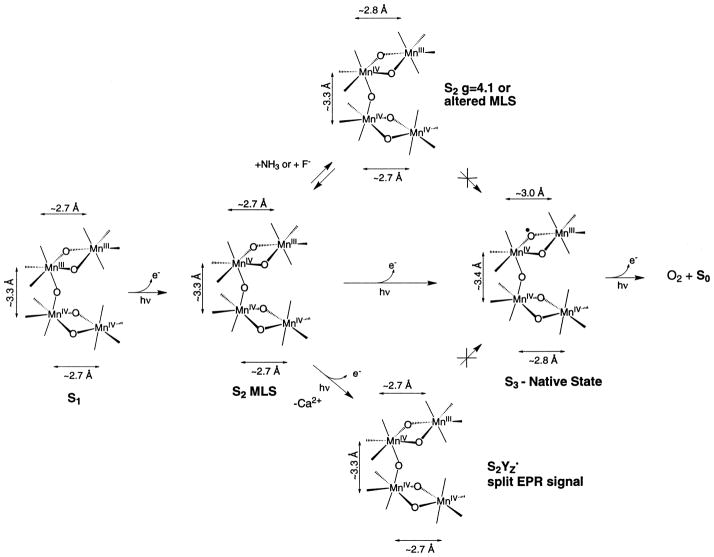

Fig. 1.

The S-state scheme for oxygen evolution. Proposed Mn oxidation states and corresponding EPR signals are shown for each S-state in the Kok cycle.

The critical questions related to this water oxidation process are the structure of the Mn complex and its nuclearity, that is the number of Mn atoms that are directly connected by bridging ligands, the oxidation state and structural changes in the Mn complex as the OEC proceeds through the S-state cycle, the structural and functional roles of the essential cofactors Ca2+ and Cl−, and the mechanism by which four electrons are removed from two water molecules by the Mn complex to produce an O2 molecule.

Mn X-ray spectroscopy studies provide direct information on the structure of the Mn cluster and on the oxidation states of the Mn atoms in the S0, S1, S2 and S3 states of the OEC. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) does not require a long-range order; the structural studies can be performed on frozen solutions. Several of the intermediate states mentioned above can be stabilized as frozen solutions. Because of the complexity of the system and the presence of many pigment and other electron-transfer components (chlorophylls, cytochromes, quinones), study of the Mn complex by optical and other spectroscopic methods can be difficult. The specificity of the XAS technique allows us to look at Mn without interference from the pigment molecules, the protein and membrane matrix, or other metals like Ca, Mg, Cu and Fe, which are also present in active preparations. X-ray K-edge spectra and Kβ X-ray emission spectra provide information about oxidation states and the site symmetry of the Mn complex, and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) at the K-edge furnishes information about the number, type and distances to neighboring ligand atoms (reviewed in [9–12]). Few other spectroscopic techniques provide such specificity for studying the structure of Mn in the OEC.

In this review, we present our view of the structure of the Mn cluster, which is refined based on new data, and a mechanism for water oxidation that emphasizes the recent results from our laboratory.

2. Oxidation states of Mn vs. S-states of the OEC

A key question for the understanding of photosynthetic water oxidation is whether the four oxidizing equivalents are accumulated on the four Mn ions of the OEC, or whether some ligand-centered oxidations take place before the formation and release of molecular oxygen. It is crucial to understand this problem, because the Mn redox states form the basis for any mechanistic proposal for photosynthetic water oxidation.

A promising approach to study the Mn oxidation states in the native S-states is to step samples through the S-state cycle by the application of saturating single-turnover flashes and to characterize these samples by X-ray spectroscopy. Roelofs et al. [13] reported X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) data from samples in the S0 through S3 states produced under these physiologically relevant conditions. The flash-advanced PS II samples prepared from spinach exhibited XANES spectra that showed Mn oxidation from S0 to S1 and from S1 to S2, but no further oxidation during the S2 to S3 transition. These results are consistent with our earlier studies of samples that were prepared by illumination at low temperature [14,15] or by chemical treatment by Guiles et al. [16,17].

Other spectroscopic techniques such as proton relaxation enhancement [18], electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) [19–21], UV absorption [22,23] and oxidized tyrosine D ( ) EPR/spin echo [24] spectroscopies show that, in PS II, the S0→S1 and S1→S2 transitions are Mn-centered oxidations, and most groups agree that Mn redox states in the S1 state are (III2, IV2) which are oxidized to (III, IV3) in the S2 state [25]. There is, however, disagreement as to whether a Mn- or ligand-centered oxidation occurs in the S2→S3 transition [26,27].

To resolve the controversy, we initiated high-resolution Mn Kβ X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) studies in collaboration with Prof. Steve Cramer, who has constructed a state-of-the-art high-resolution emission spectrometer that operates at the Mn Kβ fluorescence energy and has demonstrated the feasibility of determining the oxidation states of Mn [28]. We have now completed a comprehensive Mn Kβ XES study in conjunction with XANES, a repetition of our earlier studies by Roelofs et al. [13], on sets of samples prepared in a similar manner to address the question of the oxidation states of Mn in the various S-states.

Because the actual S-state composition is of critical importance to the interpretation of the results, we characterized the samples by EPR spectroscopy, using the S2 multiline EPR signal (MLS) as a direct measure for the S2 state population in our samples. It is essential to obtain high concentrations of PS II in the various S-states to obtain EPR, XANES and Kβ XES data with a good signal-to-noise ratio. A Nd-YAG laser system (Spectra-Physics PRO 230-10, 800 mJ/pulse at 532 nm, 9 ns pulse width) was used to illuminate PS II samples from both sides simultaneously. Because the pulse widths of the laser are narrow compared to those of a flash lamp, double hits become negligible. The damping of the oscillation pattern is decreased, thus making it possible to derive an unique set of spectra by deconvolution. When the system becomes scrambled by frequent misses and double hits, the deconvoluted spectra are not unique. Also, the laser setup has allowed us to double the sample concentration used in earlier studies [13]. The relative S-state populations in samples given 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6 flashes were determined from fitting the flash-induced EPR multiline signal oscillation pattern to the Kok model, which describes S-state dephasing as a function of flash number, for each of the samples used in the X-ray spectroscopy experiments.

2.1. Mn XANES

The Mn K-edge spectra of samples given 0, 1, 2, or 3 flashes are combined with EPR information to calculate the pure S-state edge spectra. The shifts in inflection point energy positions and changes in shape are determined by second derivatives of the K-edge spectra. In addition to the shift in edge position, the S0→S1 (2.1 eV) and S1→S2 (1.1 eV) transitions are accompanied by characteristic changes in the shape of the edge, also indicative of Mn oxidation [25]. The edge position shifts very little (0.3 eV) for the S2→S3 transition, and the edge shape shows only minor changes [29,30]. These recent results con- firm our earlier data by Roelofs et al. [13].

2.2. Mn Kβ X-ray emission spectroscopy

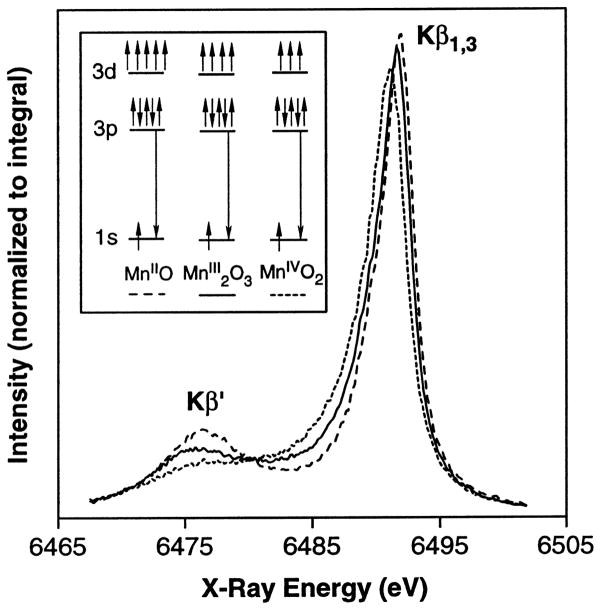

High-resolution Mn Kβ X-ray emission spectroscopy has been performed on samples prepared by using 0, 1, 2, or 3 high-power laser flashes. In this technique, the energy of the Mn Kβ emission (3p→1s) is measured with a high-resolution dispersive spectrometer [31]. The shape and energy of the Kβ1,3 emission reflect the oxidation state(s) of the emitting Mn atom(s). The emission occurs from a 3p level that is mainly influenced by the number of unpaired 3d electrons and is less sensitive to the symmetry and bonding than the K-edge absorption (see below), which involves transitions to the 4p level [10]. The spin of the unpaired 3d valence electrons can be either parallel (Kβ′) or antiparallel (Kβ1,3) to the hole in the 3p level. The splitting between the Kβ′ and Kβ1,3 peaks becomes smaller for higher oxidation states because fewer 3d electrons interact with the 3p hole. Thus, in contrast to the inflection points of the XANES edges, the Kβ1,3 peaks shift to lower energy with higher oxidation states (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kβ X-ray emission spectra of Mn oxides (adapted from Bergmann et al. [28]). The Kβ spectra consist of two main features: the Kβ′ peak at ~6475 eV and the Kβ1,3 peak at ~6490 eV. The separation of these two features is due to the exchange interaction of the unpaired 3d electrons with the 3p hole, which is formed as a final state after the core hole is filled by a 3p→1s fluorescence transition. The spin of the unpaired 3d valence electrons can be either parallel (Kβ′) or antiparallel (Kβ1,3) to the hole in the 3p level. The splitting between the Kβ′ and Kβ1,3 peaks becomes smaller for higher oxidation states because fewer 3d electrons interact with the 3p hole. Thus, in contrast to the inflection points of the XANES edges, the Kβ1,3 peaks shift to lower energy with higher oxidation states, as is seen above with the Mn oxides. The magnitude of the Kβ1,3 peak first-moment shift for is roughly a factor of four larger than the first-moment shift for the S1→S2 transition, where only one Mn out of four is being oxidized.

Using a first-moment analysis, the position of the main Kβ1,3 peak has been calculated for each S-state. Based on the shifts, or lack thereof, of the first moments, we concluded that Mn is not oxidized during the S2→S3 transition. Our results show a shift in energy between the S0 and S1 state spectra and between the S1 and S2 state, however, there is very little change between the S2 and S3 states.

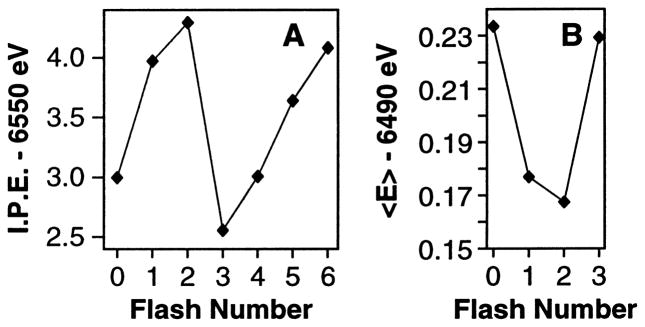

We have used two independent X-ray spectroscopic techniques, Kβ XES and XANES spectroscopy, along with EPR, to examine the Mn redox states in PS II. Fig. 3 summarizes the oscillation patterns of the XANES spectra inflection point energies (A) and of the first moments from the Kβ1,3 spectra (B). Both patterns show large shifts between the 0-flash and 1-flash samples, which reflect the Mn-centered oxidation during the S1→S2 transition. A much smaller shift occurs between 1-flash and 2-flash samples, which is inconsistent with a Mn-centered oxidation during the S2→S3 transition. Second derivatives of the S-state XANES spectra and Kβ difference spectra confirm this conclusion. We conclude that no direct Mn oxidation is involved in the S2→S3 transition. The proposed Mn oxidation state assignments are as follows: S0 (II, III, IV, IV) or (III, III, III, IV); S1 (III, III, IV, IV); S2 (III, IV, IV, IV); S3 (III, IV, IV, IV) and are summarized in Fig. 1 (J. Messinger, J.H. Robblee, U. Bergmann, personal communication).

Fig. 3.

Oscillation patterns from XANES and Kβ XES flash (nF) experiments. (A) Oscillation of XANES inflection point energies (I.P.E.) of 0F to 6F samples. (B) Oscillation of first moments (<E>) of Kβ spectra from 0F to 3F samples (4F to 6F were not collected). XANES and Kβ X-ray emission spectra shift in opposite directions in response to Mn oxidation (see text for details).

Support for this conclusion has come from XANES and Kβ XES studies of two-model compounds in which Mn oxidation occurs without ligand rearrangement or replacement. Of particular interest are the complexes [MnIII–O–MnIII]L2 (L =N,N-bis-(2-pyridylmethyl)-N′-salicylidene-1,2-diaminoethane), poised in the MnIII/MnIII, MnIII/MnIV and MnIV/MnIV states, and [MnIII–O2–MnIV]L4 (L =bipy), poised in the MnIII/MnIV and MnIV/MnIV states, by low-temperature preparative scale electrolysis [32]. The data show the expected shift in the K-edge and Kβ XES first moments when Mn is oxidized from (III2) to (III,IV) and to (IV2) (H. Visser, personal communication). The Kβ XES first-moment shifts of this set of complexes have been compared to the first-moment shift for the S1→S2 transition, taking into account the fact that the models oxidize one Mn out of two in each step, while PS II oxidizes maximally one Mn out of four. This comparison shows that the first-moment shift in the model complexes, where Mn(III) is oxidized to Mn(IV), is comparable to that seen during the S1→S2 transition in PS II. Most interestingly, the difference spectra for the (III2) to (III,IV) or (III,IV) to (IV2) transition in the mono-μ-oxo bridged complex, or the (III,IV) to (IV2) transition in the di-μ-oxo bridged complex, are almost identical. This provides conclusive evidence that Kβ X-ray emission spectra are less sensitive to structural changes and are predominantly determined by oxidation states of Mn, as indicated above. Thus we conclude that the lack of a change in the Kβ X-ray emission spectrum for the S2→S3 transition is firm evidence for lack of Mn oxidation.

The critical issue is the distribution of the oxidizing equivalents in the S3 state. In our interpretation, the oxidizing equivalent in the S3 state is stored not on Mn, but elsewhere, probably on a ligand or protein residue. We propose that it is stored on the bridging oxo ligand (vide infra) and hypothesize that changes in the Mn K-edge and Kβ X-ray emission spectra during the S2 to S3 transition are small, because the Mn 1s level is not perturbed as much by ligand oxidation as it is when Mn is oxidized.

3. Topological structure of the Mn cluster

XAS results that showed the existence of the 2.7-Å Mn–Mn distance [33–35] and the discovery of the MLS from the S2 state [19,36] established the multinuclear nature of the Mn cluster. The interplay between the two methods has played an essential role in our present understanding of the structure of the Mn complex and the mechanism of water oxidation.

3.1. Mn EXAFS-based structure

The quantitation of the Fourier peak at 2.7 Å in the S1 and S2 states leads to 1–1.5 Mn–Mn vectors per Mn in PS II at that distance [25,37–39]. The 2.7-Å Mn–Mn distance is characteristic of di-μ-oxo bridged models, therefore it was proposed that the Mn complex in the OEC is a structure with minimally two di-μ-oxo bridges. This conclusion was based principally on the observation of the 2.7-Å Mn–Mn distance, but it was also supported by the presence of a short Mn–O distance at about 1.8 Å, which is characteristic of bridging Mn–oxo distances in multinuclear Mn complexes [40].

The Fourier transforms (FTs) from the S1 and S2 states also exhibit a peak at 3.3 Å that corresponds to at least one Mn–Mn interaction and a Mn–Ca interaction (see below). A Mn–Mn 3.3 Å-distance is characteristic of mono-μ-oxo-bridged Mn complexes; hence, we proposed that the Mn cluster in the OEC consists of at least one such mono-μ-oxo bridge between two Mn atoms.

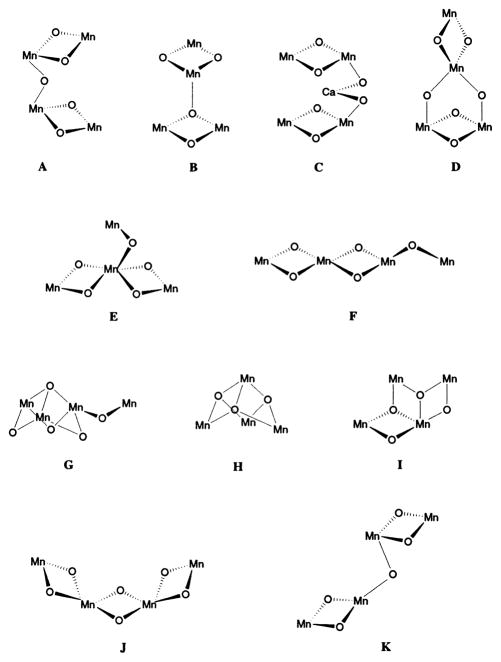

Given that there are four Mn atoms in the OEC, win at least two Mn–Mn di-μ-oxo bridges and at least one Mn–Mn mono-μ-oxo bridge, it becomes physically impossible not to have a tetranuclear Mn cluster. By comparison with the structural motifs present in multinuclear Mn complexes [41,42], we proposed that the Mn cluster in PS II consists of a pair of di-μ-oxo bridged Mn binuclear clusters linked through a mono-μ-oxo bridge. There are several topological alternatives for arranging four Mn atoms that satisfy the two requirements listed above and the details are discussed in DeRose et al. [40]. Fig. 4 shows the various options that are compatible with EXAFS data and, among those options, A, E, F, G and K are especially favored.

Fig. 4.

Possible core structures for the active site of the OEC in PS II. Adapted from DeRose et al. [40]. Only Mn and bridging O are shown.

EPR and ENDOR simulations of the MLS by Britt and coworkers [43] and Kusunoki and coworkers [44] are in better agreement with E, F or G shown in Fig. 4. Temperature dependence studies of the g =4.1 S2 signal have led Å hrling et al. [45] to propose two non-magnetically interacting Mn dimers like those shown in Fig. 4C.

It is important to emphasize that the spatial arrangement of the four Mn atoms associated with the water-oxidation complex is not definitively known. Although option A in [40] (Fig. 4A) has been used as a working model [25], the other options E, F, G or K in Fig. 4 are equally feasible, as we emphasized in DeRose et al. [40]. The mechanism proposed on the basis of density functional calculations [46] prefers option F in Fig. 4, where the two di-μ-oxo units are adjacent to each other; a structural arrangement that can more easily explain the lengthening of both of the two 2.7-Å Mn–Mn distances in the S3 state.

3.2. Structural insights from the dichroism of the Mn cluster

PS II preparations [47,48] are membrane fragments, thus the cofactors are vectorially arranged. We have taken advantage of this to investigate the angles between the various Mn–Mn or Mn–Ca(Sr) or Mn–Cl(Br) vectors to derive geometrical information about the Mn cluster, something that is normally not available from XAS studies.

The dichroism studies have provided crucial information about the symmetry, or the lack of it, of the Mn complex that, along with the structural information described above, place constraints on the structural alternatives that are possible. The two Mn–Mn vectors at 2.7 Å are aligned at an average angle of 60±7° to the membrane normal and the 3.3-Å Mn–Mn vector is aligned at ~62° with respect to the membrane normal (vide infra). The pronounced dichroism of the Mn–Mn vectors provides evidence that the Mn cluster is asymmetric, a result that unequivocally rules out all highly symmetric structures.

4. Structural role of cofactors of the Mn cluster

4.1. Calcium cofactor

Along with Mn and Cl−, Ca2+ is an essential cofactor in oxygen evolution [1,6]. Depleting this cofactor suppresses OEC activity, which can be restored (up to 90%) by replenishing with Ca2+. Partial reactivation (up to 40%) results from addition of strontium to Ca-depleted PS II membranes [49,50] and no other metal ions (except VO2+, vanadyl ion [51]) can restore activity [52–54].

Although Sr2+ replenishes the Ca-depleted centers to a similar extent as added Ca2+, the slower kinetics of the OEC turnover yields an overall lower steady-state rate (40%) at saturating light intensities [55]. Substitution of Ca2+ with Sr2+ also alters the EPR multiline signal (MLS) from the S2 state, giving narrower hyperfine splitting and different intensity patterns [50,56–58]. Most researchers addressing the stoichiometry of the Ca2+ cofactor in PS II now conclude that functional water oxidase activity requires one Ca2+, which can be removed by low-pH/citrate or 1.2 M NaCl wash [52,59–62]. In higher plants, another more tightly bound Ca2+ is associated with the light-harvesting complex (LHC II) and requires harsher treatments for its removal [63–65].

There is debate about the environment of the Ca2+ cofactor binding site and its function. Several investigations have involved substitution of various metals into this binding site, followed by EXAFS studies on the Mn cluster. One set of experiments using EXAFS on Sr-reactivated PS II membranes was interpreted to indicate a 3.4–3.5-Å distance between the Ca (Sr) and the Mn cluster [66]. This conclusion was based on the observation of increased amplitude in the FT peak at 3.3 Å upon replacement of Ca2+ with Sr2+, which is a heavier atom and thus a better X-ray scatterer. This close link is also supported by FTIR spectroscopic work [67] that is consistent with a carboxylate bridge between Mn and Ca. Analysis of EXAFS spectra from purified PS II membrane preparations by MacLachlan et al. also support the proximity of Ca to Mn [38]. Ca2+-depletion by NaCl-washing of PS II membranes removed the 16- and 23-kDa extrinsic proteins [68] and led to a reduced amplitude for this Fourier transform peak [69]. Because of the lower X-ray scattering ability of sodium, this result was interpreted as possible Na+ substitution for Ca2+ [69].

However, another Mn EXAFS study [70] did not detect any changes in the Fourier peak at 3.3 Å when Ca was replaced with Sr2+ or Dy3+ in PS II reaction center complexes lacking the 16- and 23-kDa extrinsic polypeptides. These authors found no evidence of an EXAFS-detectable Mn–Ca interaction at about 3.3 Å and proposed that Ca2+ was located at a distance beyond 4 Å from the Mn cluster, coordinated by a ligated water molecule to a di-μ-oxo oxygen bridge. More support came from EPR-based experiments involving Mn2+ substitution in Ca-depleted (inactive) PS II membranes, which indicated that the Mn2+-occupied Ca2+ binding site was outside the first coordination region of the catalytic cluster (beyond 4 Å) [71].

4.1.1. Strontium-reconstituted OEC

Given this uncertain situation, and to further test whether a Ca binding site is close to the Mn cluster, we decided to embark on a different approach: to use strontium EXAFS methods to probe from the Sr cofactor point-of-view for nearby Mn within 4 Å. This is the reverse of the previously described Mn EXAFS studies that concentrated on the Mn cluster [66,70], and probed for nearby Ca2+ or Sr2+ neighbors. Several factors favor Sr2+ as the better cofactor for this XAS study. The X-ray energies involved (16 keV for the K-edge) are more penetrating and not significantly attenuated by air. The higher X-ray absorption cross-section and fluorescence yield of Sr relative to Ca also make the experiment practicable.

We substituted Sr2+ for Ca2+ and probed from the Sr2+ point of view for any nearby Mn. The EXAFS of Sr-PS II probes the local environment around the Sr2+ cofactor to detect any nearby Mn. We focused on the functional Sr2+ by removing non-essential, loosely bound Sr2+ in the protein environment. For comparison, an inactive sample was prepared by treating the intact PS II with hydroxylamine to disrupt the Mn cluster and to produce non-functional enzyme. Sr EXAFS results indicate major differences in phase and amplitude between the functional (intact) and non-functional (NH2OH-treated) samples. In intact samples, the FT of the Sr EXAFS shows a peak that is missing in inactive samples. This Fourier Peak II is best simulated by two Mn neighbors at a distance of 3.5 Å. Thus, with X-ray absorption studies on Sr-reconstituted PS II, we confirm the proximity of Ca2+ (Sr2+) cofactor to the Mn cluster and show that the active site is a Mn–Ca heteronuclear cluster [72].

As an extension of this approach, polarized Sr EXAFS studies on oriented Sr2+-reactivated PS II show that this Fourier peak II is highly dichroic: within the range of angles θ, between the PS II membrane normal and the X-ray electric field vector, that were examined, the magnitude of peak II was largest at 10° and smallest at 80°. The dichroism pattern is best fit by an average angle between the Mn–Sr (and therefore Mn–Ca) vectors and the membrane normal of ~23° to the membrane normal [29,73,74].

The results further bolster the contention that Ca2+ (Sr2+) is proximal to the Mn cluster and allows us to refine the working model of the OEC in PS II. These measurements place constraints on the kinds of structures that are possible for the Mn cluster and aid in narrowing the options available.

4.1.2. Calcium-depleted OEC

The structural consequences of Ca2+ depletion of PS II by treatment at pH 3.0 in the presence of citrate has been determined by Mn XAS. XANES of Ca2+-depleted samples in the three modified S-states (referred to here as S′-states) reveals that there is Mn oxidation on the S1′ to S2′ transition, although no evidence of Mn oxidation was found for the S2′ to S3′ transition. These results are in keeping with results from EPR studies where it has been found that the species oxidized to give the S3′ broad radical signal [75] found in Ca2+-depleted PS II is tyrosine Yz [76–78]. EXAFS measurements of Ca2+-depleted samples in the S1′, S2′, and S3′ states reveals that the Fourier peak due to scatterers at~3.3 Å from Mn is strongly diminished, consistent with our previous assignment of a Ca2+ scattering contribution at this distance [79]. However, even after Ca2+ depletion, there is still significant amplitude in the third peak, further supporting our conclusion from earlier studies that the third peak in native samples is comprised of both Mn and Ca scattering. The Mn–Mn contributions making up the second Fourier peak at ~2.7 Å are largely undisturbed by Ca2+-depletion.

4.2. Chloride cofactor

The results of steady-state kinetic experiments have been interpreted to indicate a halide binding site on the Mn cluster [80]. Despite a multitude of spectroscopic studies, direct structural evidence for such a site has not yet been reported.

There is one functional Cl− per PS II unit [81], but it is unclear whether chloride is a ligand to one of the Mn atoms in any of the five S-states. Steady-state kinetic studies indicate the presence of a halide binding site on the Mn complex [7,81,82], and activity is inhibited by some compounds which compete with the Cl− binding site, such as fluoride [82] and primary amines [82–84]. Ono et al. [85] have shown that Cl−-depleted PS II particles in the S2 state do not have the usual MLS but rather have a signal at g =4.1, signifying that an alternative S2 state is formed. A similar EPR signal is observed on treatment with F−. It was found that when the OEC is in this alternative state, it can no longer advance to higher S-states. However, the EPR multiline signal is restored following illumination and subsequent addition of Cl−. Recent studies indicate that the presence of the Cl− is necessary only for the S2 to S3 and S3 to S0 transitions of the OEC, while the earlier steps of the cycle can proceed in its absence [86,87]. These studies indicate that Cl− is closely associated with the structure of the OEC and the mechanism of oxygen evolution, but its detailed role is as yet unclear.

F− perturbation of the Mn–Mn distances by treatment with F− is one of the most direct data available that implies halide as a ligand of Mn. XAS studies of F−-inhibited samples show that one of the two 2.7-Å Mn–Mn distances is increased to ~2.8 Å, which is suggestive of F− binding to the Mn cluster [88].

Our XAS results from isotropic samples in the S3 state have shown that there is considerable change in the Mn–Mn distances as the system advances from the S2 to the S3 state [89,90]. The two 2.7- Å Mn–Mn distances in the S2 state increase to ~2.8 and 2.9–3.0 Å in the S3 state. With the aim of determining the relative orientation of the 2.8 and 2.9–3.0- Å Mn–Mn vectors, we initiated XAS studies of oriented S3 state samples. The results show that the two Mn–Mn vectors are dichroic. Interestingly, perhaps because of the lengthening of the Mn–Mn vectors, a new Fourier peak is observed between the first and second Fourier peaks. Comparing this FT with that of a Mn binuclear complex with one Cl− as a terminal ligand to a Mn atom shows that the peak corresponding to Cl backscattering in the model complex is found at approximately the same apparent distance as the new Fourier peak in the PS II samples [91]. In other model compounds, the amplitude of this peak increases as the ratio of Cl/Mn increases and the peak is absent when Cl− is not present as a ligand. In the S3 state sample, this peak does not fit to lower Z atoms such as C, N, or O. The fit is significantly better for Cl backscattering at ~2.2 Å. The fits for the model compound are very similar. The difference in amplitude of this Fourier peak between the S3 sample and the model is probably due to the difference in the number of Cl− backscatterers/Mn in the model and in PS II. It is likely that in PS II the ratio is only one Cl− per four Mn as compared to one Cl− per two Mn in the model compound. Dichroism studies on seven different S3 state samples show that the Fourier peak is larger at the 10° orientation compared to the 80° orientation, which suggests that the Mn–Cl vector is more parallel to the membrane normal.

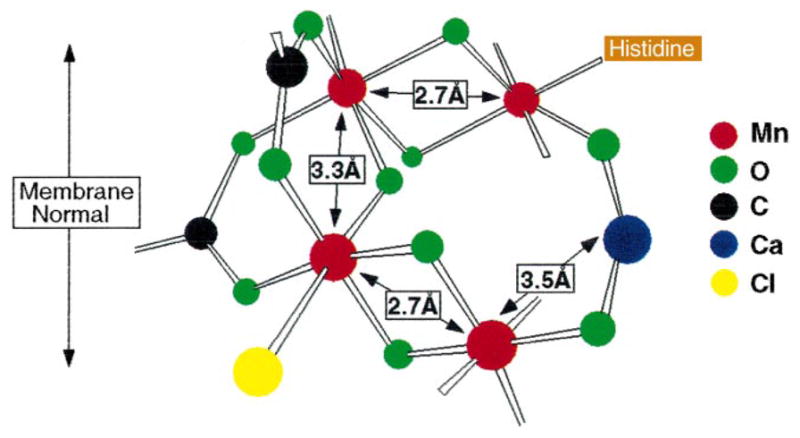

5. Refined model of the Mn/Ca/Cl heteronuclear cluster

The Mn EXAFS data clearly establish an asymmetric tetranuclear Mn cluster that can accommodate two 2.7- Å Mn–Mn vectors and one 3.3- Å Mn–Mn vector. The dichroism that is present in the Mn EXAFS data shows that the two Mn–Mn vectors at 2.7 Å are aligned at average angle of 60±7° to the membrane normal. The Sr EXAFS data and data from Ca-depleted preparations place Ca2+ at a distance of 3.4 Å from 1–2 Mn atoms. Cheniae and coworkers have shown that Ca2+ is a prerequisite for the assembly of the Mn cluster [65]. There is good evidence as described above for the inclusion of Cl− as a ligand, at least in the S3 state. There is also evidence for the presence of at least one histidine residue as a ligand of Mn [92]. Finally, the lack of multiple scattering features [93] in the Mn and Sr EXAFS spectra indicate that the OEC does not contain a collinear (θ>150°) arrangement of three Mn atoms (or two Mn atoms and one Ca atom). It also excludes linear Mn–O–Mn and Mn–O–Ca moieties. A proposed model is shown in Fig. 5 [72].

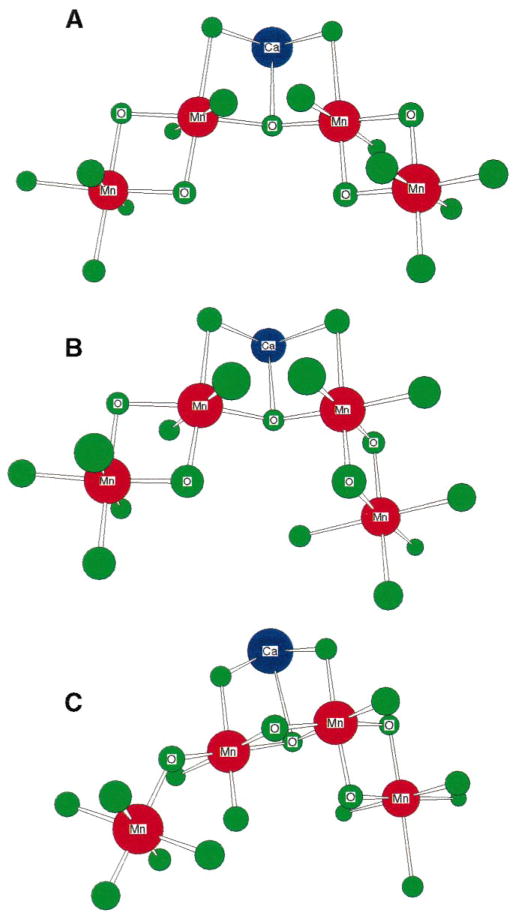

Fig. 5.

Proposed model for the active site of the OEC in PS II from the work of Cinco et al. [72]. The model incorporates the finding from the isotropic Sr-substituted PS II studies: Sr2+ (and therefore Ca2+) is intimately linked to the Mn cluster at a distance of ~3.4–3.5 Å. This linkage requires single-atom (oxygen) bridging that can derive from acidic protein residues (aspartate or glutamate), hydroxide, or water. Depicted is one of several possible configurations consistent with the findings of the isotropic Sr EXAFS studies.

Additional structural constraints have become available from the recently completed oriented Sr XAS experiments. The dichroism data from the Sr XAS experiments can be combined with the dichroism data from peak III in the Mn EXAFS data to calculate the dichroism of the 3.3- Å Mn–Mn vector. This peak III, which contains equal numbers of Mn–Mn (3.3 Å) and Mn–Ca (3.4 Å) contributions, is dichroic, with an average angle of 43±10° with respect to the membrane normal [94]. Moreover, the 43±10° estimate is a cos2ϕ-weighted average of the orientations of the Mn–Mn (3.3 Å) and the Mn–Ca vectors [95–97]. Thus, having independent knowledge from Sr EXAFS experiments that the Mn–Ca dichroism is ~23° means that the 3.3 Å Mn–Mn vector is aligned at ~62° with respect to the membrane normal. Therefore, all three Mn–Mn vectors lie at the same angle (~28°) with respect to the membrane plane. The vectors are not restricted to being collinear, because each of these vectors can lie anywhere on a cone with a defined angle with respect to the membrane normal.

Because significant angular information about Mn–Mn and Mn–Ca vectors is now available, the model shown in Fig. 5 and other topological models shown in Fig. 4 can be refined to include the presence of Ca2+ and take into account the new dichroism data. We have chosen to modify two options from Fig. 4: option A, where the two di-μ-oxo binuclear units are connected by a mono-μ-oxo bridge, and option F, where the two di-μ-oxo motifs are formed using a common Mn atom and the mono-μ-oxo motif is placed at the end of the trinuclear unit.

One possible modification for option A from Fig. 4 is the structure shown in Fig. 5; however, this arrangement, with the Ca2+ at the open end of the complex, places the Ca–Mn and 3.3-Å Mn–Mn vectors roughly parallel, which is inconsistent with the current dichroism data for these vectors. Placing the Ca2+ at the closed end of the complex resolves this discrepancy, and the angle between the two di-μ-oxo vectors can now be adjusted.

Fig. 6A,B shows two possibilities for this configuration of Mn and Ca atoms. These placements are reconcilable with the dichroism results from the 2.7-Å Mn–Mn, 3.3-Å Mn–Mn, and 3.4-Å Mn–Ca vectors. In addition, Ca2+ can be incorporated into option F from Fig. 4, which has two adjacent di-μ-oxo bridged Mn–Mn moieties which are linked to another Mn atom via a mono-μ-oxo bridge. Ca2+ forms an open cubane with two Mn atoms forming the other two corners. This arrangement of Ca and Mn atoms is preferred by density functional theory simulations and simulations of EPR and ENDOR data from the OEC [44,46]; a variant of this structure has been proposed by Siegbahn [46].

Fig. 6.

Refined models for the active site of the OEC in PS II. These models incorporate the recent finding from oriented Sr-substituted PS II studies that the Sr–Mn vectors lie at an average angle of ~23° with respect to the membrane normal; thus, the refined angle for the 3.3 Å Mn–Mn vector is ~62°. The distance between the two Mn atoms on either end of the complex in model A can be somewhat shortened by using a different oxygen ligand atom from the inner Mn to form the di-μ-oxo binuclear unit on the right side. This is shown in model B. Model C is a variation on a model originally proposed by Siegbahn [46]. The position of the Mn on the end of the mono-μ-oxo bridge can be varied by rotation about the inner Mn–O mono-μ-oxo bond.

All three refined models shown in Fig. 6 were constructed preserving the structural motifs proposed by us earlier [40] and are variations of the original model [25,72]. In each of the models in Fig. 6, the Ca2+ atom is not in a plane defined by either of the di-μ-oxo bridges, thus eliminating multiple scattering effects in the EXAFS. Both of these proposed models are consistent with the current Sr and Mn XAS data; however, we have not yet tested the compatibility of our XAS data with all possible topological models, including those proposed by Kusunoki and coworkers (option G in Fig. 4 [40]) [44].

6. Structural changes of the Mn cluster in the S-states

The changes in Mn–Mn distances occurring during the S1 to S2 and S3 transitions within the context of the model in option A in Fig. 4 are shown in Fig. 7. However, we emphasize that the changes in Mn–Mn distances can be illustrated as well using the other topologically viable alternatives described above.

Fig. 7.

Summary of the changes in Mn–Mn distances in the native S1, native S2, modified S2, , and native S3 states of PS II as determined by XAS. Reprinted from Liang et al. [90]. Copyright 2000 American Chemical Society

6.1. S1 to S2 state transition (g=4.1 or MLS S2 state)

The first step in the scheme is the conversion of the dark stable S1 state to the S2 state that is characterized by the MLS. Little change is observed in the fitting parameters for Fourier peaks II and III when the Mn cluster undergoes this transition. This step involves a Mn-centered oxidation, demonstrated by the appearance of the MLS during this transition and by our Mn K-edge and Mn Kβ XES studies [13,19,30,36]. Fourier peak II, corresponding to the averaged Mn–Mn distance in each di-μ-oxo dimanganese unit, is best fit to ~2.7 Å for both the S1 and S2 states [40]. EXAFS studies on oriented PS II in the S1 and S2 states show that there is heterogeneity in the 2.7- Å vectors, which suggests that these two binuclear species are not completely equivalent [94,95].

The inequivalence of the two di-μ-oxo-bridged Mn units becomes more evident in the S2 state that is prepared by illumination at 130 K and characterized by the g=4.1 EPR signal [98]. Similar results were obtained with NH3-treated and annealed S2 state samples [97] and in F−-treated samples [88]. In these modified S2 states, one of the Mn–Mn distances increases to ~2.85 Å, whereas there is very little change in the other 2.7 Å or the 3.3- Å Mn–Mn distance. With the degeneracy of the 2.7 Å lifted we were able, by studying the dichroism of the Fourier peak, to assign the relative orientation of the 2.7- and 2.85- Å vectors [97]. The scheme in Fig. 7 shows that there are paths from the MLS S2 state that lead to two states: the S2-g=4.1 state inhibited by NH3/F− or the S2-oxidized tyrosine residue ( ) states; neither of these states can proceed to the physiologically relevant S3 state. These states are depicted in Fig. 7 as branching away from the normal pathway leading to the S3 state by photon absorption. However, the S2-g=4.1 state generated by 820-nm illumination at 130 K [99] can proceed to an S3 state [100].

The NH3-treated and F−-treated samples cannot advance beyond the modified S2 state ( state). It is likely that F− or NH3 prevents the structural changes or oxidation of the oxo-bridge involved in the formation of the S3 state that are necessary for proceeding beyond the S3 state. The modification of the MLS spectra upon addition of NH3 [101] and ESEEM studies using 14NH3 and 15NH3 demonstrated that NH3 becomes a ligand of Mn [102]. The asymmetry parameter derived from ESEEM results is compatible with an amido group as a bridging ligand, either between two Mn atoms or between a Mn and a Ca atom [102].

6.2. S2 to S3 state transition (S3′ or native S3 state)

Significant changes are observed in the Mn–Mn distances in the S3 state compared to the S1 and the S2 states. The two 2.7-Å Mn–Mn distances that characterize the di-μ-oxo centers in the S1 and S2 states are lengthened to ~2.8 and 3.0 Å in the S3 state, respectively (Fig. 7). These changes in Mn–Mn distances are interpreted as consequences of the onset of substrate water oxidation in the S3 state. Mn-centered oxidation is evident during the S0→S1 and S1→S2 transitions. During the S2→S3 transition, we propose that the changes in Mn–Mn distances are the result of ligand or water oxidation, leading to the formation of an oxyl radical intermediate at a bridging or terminal position. The reaction of the oxyl radical with OH−, H2O, or an oxo group during the subsequent S-state conversion then forms the O–O bond [90]. We propose that substrate/water oxidation occurring at this transition provides the trigger for the formation of the O–O bond; the critical step in the water oxidation reaction.

The results from isotropic S3 samples are supported by polarized EXAFS studies on oriented PS II in the native S3 state. The data confirm that the two di-μ-oxo-bridged Mn–Mn dimer units are not equivalent. Fourier peak II of S3 is dichroic and is readily resolved to Mn–Mn distances of ~2.8 Å and ~3.0 Å, each with its own distinct projection on the membrane normal [91]. The polarized EXAFS data are different from those observed in the S2 state which showed two Mn–Mn distances at ~2.7 Å [94,97].

The other unproductive state generated from the S2-MLS state is denoted in Fig. 7 as the state (referred to as the S3′ state below) generated in Ca-depleted samples. The Ca-depleted samples are inactive in O2 evolution, while a broad g=2 EPR signal has been observed in the S3′ state of such samples [75]. In such samples, the g=2 broadened EPR signal has been confirmed to arise from [76,77,103], and it is proposed that the signal is broadened by interaction with the spin on the Mn cluster [104].

We recently reported the XAS analysis from calcium- depleted S3′ state samples [79]. The position of Peak II in the FT of S3′ state samples was invariant relative to that of the native S2 state sample. The EXAFS fits showed that the 2.7- Å Mn–Mn distances did not lengthen as observed in the native S3 state samples and are essentially unchanged from those of the native S2 state. This finding is surprising because the Mn K-edges from these Ca-depleted samples showed a behavior similar to the native PS II in that little or no shift was observed in the S2′→S3′ transition. This difference between the native S3 and calcium-depleted S3′ states indicates that the core di-μ-oxo-bridged structure is probably dissimilar in the native S3 and the S3′ states, with the structure in the S3′ state resembling the native S2 state structure. It is reasonable to question how the transfer of one electron from the Mn cluster onto YZ can result in major changes in the Mn–Mn distances, as is observed in the native S3 state. The roles of YZ and the Mn cluster in the process of water oxidation are clearly delineated by the comparison of the S3 and the S3′ states. Instead of the Mn cluster simply providing a scaffold for water oxidation, this comparison shows that the structural change in the Mn cluster initiated by the transfer of an electron from the Mn cluster to Tyrz during the S2→S3 transition may provide the trigger to the chemistry of the formation of the O–O bond. The results show that the Mn cluster is involved in a much more intimate manner in the catalysis than just providing the framework. The implications to the mechanism are significant (see below).

In Ca2+-depleted systems the tyrosine YZ radical is stabilized, and the oxidation of the Mn–OEC and the concomitant changes in Mn–Mn distances are prevented. In the S3 state, with Ca2+ present, the radical resides on the Mn cluster; however, in the absence of Ca2+, the radical resides on tyrosine Z. Thus, Ca2+ is proposed to play a crucial role in controlling the redox potential and thus the course of the mechanism of water oxidation.

6.3. S0 to S1 state transition

A comparison of the EXAFS spectra from the S0 and S1 states has been completed [30]. The most prominent change is the decrease in the amplitude of the 2.7- Å feature in the S0 sample. This is consistent with the presence of two slightly different Mn–Mn distances around 2.7 Å. The fits show the lengthening of one Mn–Mn distance from 2.72 Å (S1) to about 2.85 Å (S0) and an increase in the average Mn–O/N distance. In contrast, no reasonable fits with two different Mn–Mn distances were possible for peak II in the S1 state.

The structural changes on the S0 to S1 transition can be explained by the oxidation of one Mn(II) to Mn(III), because this would account for both the lengthening of the Mn–O/N bonds and of one Mn–Mn distance. The EXAFS results point, along with the XANES data, to Mn(II,III,IV2) as Mn redox states in S0.

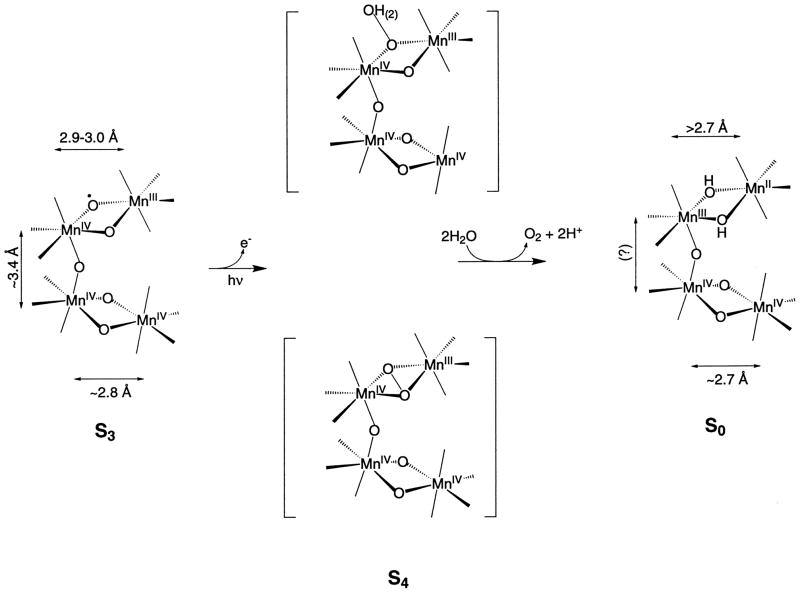

7. Structure-based mechanism of water oxidation

We have proposed earlier a model for the S3 state in which an oxyl radical is generated on one of the μ-oxo-bridges, which results in an increase of one of the Mn–Mn distances to ~2.95 Å (Fig. 7) [4,90]. Consistent with our XANES results is the implication in this structure that the oxidative equivalent is not stored on the Mn atoms per se during the S2→S3 transition but is delocalized with significant charge and spin density on the bridging oxo ligand. Junge and coworkers have proposed a mechanism involving Mn oxidation during the S0→S1 and S1→S2 transitions, and the oxidation of bound substrate, OH−, to a hydroxide radical during the S2→S3 transition, with a small admixture of a peroxide intermediate [105]. For the S3 state, Renger and coworkers have proposed an equilibrium between bound hydroxide (or water) and peroxide bound between two Mn atoms [106].

Two essential factors are considered to construct possible structural arrangements of the Mn cluster in the S3 state. First, our Mn K-edge inflection point data better support the interpretation that there is little or no oxidation of Mn during the S2→S3 transition. These data are reinforced by our recent Mn Kβ XES studies of the various S-states [30]. Second, the Mn–Mn distance in both of the di-μ-oxo-bridged units increases from 2.72 Å to 2.82 Å and 2.95 Å, upon the formation of the S3 state. These changes imply a significant structural change in the Mn cluster as it proceeds to the S3 state. It is difficult to rationalize such changes in Mn–Mn distance as arising purely from Mn oxidation. We propose that substrate/water oxidation chemistry is occurring at this transition, leading to the significant structural changes

In addition to oxo-bridging ligands, Mn terminal oxo ligands have also been proposed to be involved in dioxygen formation [107,108]. It has been proposed that Mn is ligated to activated O (Mn=O) produced by the abstraction of protons from Mn-bound water by a nearby tyrosine [77,109,110], and the O–O bond is proposed to form between the oxo ligands of two adjacent Mn atoms [5]. However, it is difficult to understand how changes in terminal ligation can generate such a profound change on the Mn–Mn distances in the S3 state as reported here. Replacement of terminal ligands in di-μ-oxo-bridged model compounds has a minimal effect on the Mn–Mn distance of 2.7 Å that is characteristic of such di-μ-oxo bridged Mn compounds [41,42].

The case for the involvement of the bridging oxygen atoms during the S2→S3 transition and in the mechanism of oxygen evolution is many fold. It is easy to rationalize increases in Mn–Mn distances as being due to changes in the bridging structure.

The disappearance of the multiline signal upon advancement to the S3 state does not necessarily indicate Mn oxidation during the S2→S3 transition; the lack of a multiline signal is also consistent with the formation of a radical on a bridging oxygen atom, which changes the spin state of the Mn complex. Parallel-mode EPR studies by Kawamori and coworkers have shown the presence of EPR resonances at g=12 and 8 that are best simulated by an S=1 excited spin state species in the S3 state [111]. A similar signal from the S3 state has recently been reported by Ioannidis and Petrouleas [112]. These signals are consistent with the coupling of the S =1/2 spin of the Mn complex in the S2 state with the S =1/2 radical introduced in the S3 state.

Siegbahn and Crabtree have proposed a mechanism on the basis of quantum chemical studies where they have tried to reconcile the various biophysical data [113]. Spin state considerations led them to propose a Mn–O oxyl intermediate in the S3 state, with radical character on the terminal oxygen ligand, with the formation of the O–O bond proposed to occur between the oxyl radical and an outer-sphere water molecule. Recent calculations by Siegbahn produced an energy minimum for the formation of the oxyl radical on the bridging O atom [46]. The Siegbahn and Crabtree mechanism involves only one Mn in the oxidation process and involves a radical species in the S3 state as proposed by our group.

We propose that the O–Mn–O angle in one of the di-μ-oxo-bridged Mn–Mn moieties decreases in the S3 state and as a consequence draws the two bridging oxo ligands closer for the imminent formation of an O–O bond before O2 release. Consequently, the distance between the two Mn atoms lengthens. We previously proposed that in the S4 state a dioxyl radical is produced which spontaneously converts to a peroxo species with the formation of an O–O bond (Fig. 8) [4]. This proposal is inspired from the study of a synthetic inorganic di-μ-oxo-bridged di-Cu compound, that has been shown to convert into an isomer with the formation of an O–O bond between the two bridged oxygens [114]. Alternatively, the formation of the oxyl radical on one dimer in the S3 state and its reaction with OH− or H2O either on the other Mn dimer or in the outer sphere during the subsequent S-state conversion can lead to the formation of the O–O bond (Fig. 8). The results by Messinger and coworkers support the presence of two non-equivalent exchangeable sites in the S3 state as required by this proposal [108,115].

Fig. 8.

Scheme showing two different paths by which an oxyl radical formed in the S3 state may form an O–O bond in the transient S4 state before release of dioxygen. One path involves the formation of an O–O bond between the two oxo groups of one binuclear unit. The other path for the formation of the O–O bond is the reaction of the oxyl radical formed with OH− or H2O that is a ligand of Mn or in the outer sphere of the Mn cluster. The Mn–Mn distances in the transient S4 state are unknown at present. Reprinted from Liang et al. [90]. Copyright 2000 American Chemical Society

Our proposed mechanism avoids the formation of the O–O bond until the most oxidized state (S4) is reached. This precludes the formation and release of peroxide or other oxidation products of water in the earlier S-states, thus preventing the system from ‘short circuiting’ and avoiding the risk of damaging the polypeptides of PS II.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant (GM 55302) and by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Energy Biosciences, U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC03-76SF00098. We are indebted to Profs. Mel Klein and Ken Sauer for all their help, encouragement, and contributions to every aspect of the work presented in this review. We thank Dr. Johannes Messinger and Dr. Carmen Fernandez for many useful discussions regarding the structure and mechanism of the OEC and their contributions. We are grateful to Hendrik Visser, Drs. Shelly Pizarro, Karen McFarlane, Emanuele Bellacchio, Wen Liang, Theo Roelofs, Matthew Latimer, Annette Rompel, Elodie Anxolabéhère-Mallart and Olivier Horner for all their contributions. We thank Prof. Steve Cramer, Dr. Uwe Bergmann and Pieter Glatzel for the collaboration on the Mn Kβ XES experiments. We thank our collaborators Profs. K. Wieghardt, G. Christou, W. H. Armstrong, J.-J. Girerd, V.L. Pecoraro, and R.N. Mukherjee for providing all the inorganic Mn compounds. Synchrotron radiation facilities were provided by the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) and the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), both supported by the U.S. Department of Energy. The Biotechnology Laboratory at SSRL and Beam Line X9 at NSLS are supported by the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- EXAFS

extended X-ray absorption fine structure

- FT

Fourier transform

- MLS

multiline EPR signal

- OEC

oxygen evolving complex

- PS II

photosystem II

oxidized tyrosine D

oxidized tyrosine residue

- XANES

X-ray absorption near-edge structure

- XAS

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

- Kβ XES

Kβ X-ray emission spectroscopy

Footnotes

We dedicate this review to the memory of Mel Klein, our colleague, collaborator, mentor, and dear friend.

References

- 1.Debus RJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1102:269–352. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90133-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock GT, Wikström M. Nature Lond. 1992;356:301–309. doi: 10.1038/356301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britt RD. In: Oxygenic Photosynthesis: The Light Reactions. Ort DR, Yocum CF, editors. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 1996. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2927–2950. doi: 10.1021/cr950052k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tommos C, Babcock GT. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yocum CF. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1059:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yocum CF. In: Manganese Redox Enzymes. Pecoraro VL, editor. VCH; New York: 1992. pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kok B, Forbush B, McGloin M. Photochem Photobiol. 1970;11:457–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1970.tb06017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer SP. In: X-ray Absorption: Principles, Applications and Techniques of EXAFS, SEXAFS, and XANES. Koningsberger DC, Prins R, editors. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1988. pp. 257–320. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng G, de Groot FMF, Hämäläinen K, Moore JA, Wang X, Grush MM, Hastings JB, Siddons DP, Armstrong WH, Mullins OC, Cramer SP. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:2194–2290. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yachandra VK. Methods Enzymol. 1995;246:638–675. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)46028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yachandra VK, Klein MP. In: Biophysical Techniques in Photosynthesis. Amesz J, Hoff AJ, editors. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 1996. pp. 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roelofs TA, Liang W, Latimer MJ, Cinco RM, Rompel A, Andrews JC, Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Klein MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3335–3340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodin DB, Yachandra VK, Britt RD, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;767:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDermott AE, Yachandra VK, Guiles RD, Cole JL, Dexheimer SL, Britt RD, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4021–4031. doi: 10.1021/bi00411a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guiles RD, Zimmermann JL, McDermott AE, Yachandra VK, Cole JL, Dexheimer SL, Britt RD, Wieghardt K, Bossek U, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1990;29:471–485. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guiles RD, Yachandra VK, McDermott AE, Cole JL, Dexheimer SL, Britt RD, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1990;29:486–496. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharp RR. In: Manganese Redox Enzymes. Pecoraro VL, editor. VCH; New York: 1992. pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dismukes GC, Siderer Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:274–278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messinger J, Robblee JH, Yu WO, Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Klein MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11349–11350. doi: 10.1021/ja972696a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messinger J, Nugent JHA, Evans MCW. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11055–11060. doi: 10.1021/bi9711285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Leeuwen PJ, Heimann C, van Gorkom HJ. Photosynth Res. 1993;38:323–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00046757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dekker JP. In: Manganese Redox Enzymes. Pecoraro VL, editor. VCH; New York: 1992. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Styring SA, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4915–4923. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yachandra VK, DeRose VJ, Latimer MJ, Mukerji I, Sauer K, Klein MP. Science. 1993;260:675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.8480177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono TA, Noguchi T, Inoue Y, Kusunoki M, Matsushita T, Oyanagi H. Science. 1992;258:1335–1337. doi: 10.1126/science.258.5086.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iuzzolino L, Dittmer J, Dörner W, Meyer-Klaucke W, Dau H. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17112–17119. doi: 10.1021/bi9817360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergmann U, Grush MM, Horne CR, DeMarois P, Penner-Hahn JE, Yocum CF, Wright DW, Dubé CE, Armstrong WH, Christou G, Eppley HJ, Cramer SP. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:8350–8352. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cinco RM, Fernandez C, Messinger J, Robblee JH, Visser H, McFarlane KL, Bergmann U, Glatzel P, Cramer SP, Sauer K, Klein MP, Yachandra VK. In: Photosynthesis: Mechanisms and Effects. Garab G, editor. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 1998. pp. 1273–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Messinger J, Robblee JH, Fernandez C, Cinco RM, Visser H, Bergmann U, Glatzel P, Cramer SP, Campbell KA, Peloquin JM, Britt RD, Sauer K, Klein MP, Yachandra VK. In: Photosynthesis: Mechanisms and Effects. Garab G, editor. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 1998. pp. 1279–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergmann U, Cramer SP. SPIE Conference on Crystal and Multilayer Optics. SPIE; San Diego, CA: 1998. pp. 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horner O, Anxolabéhère-Mallart E, Charlot MF, Tchertanov L, Guilhem J, Mattioli TA, Boussac A, Girerd JJ. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:1222–1232. doi: 10.1021/ic980832m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirby JA, Robertson AS, Smith JP, Thompson AC, Cooper SR, Klein MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:5529–5537. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yachandra VK, Guiles RD, McDermott A, Britt RD, Dexheimer SL, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;850:324–332. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yachandra VK, Guiles RD, McDermott AE, Cole JL, Britt RD, Dexheimer SL, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5974–5981. doi: 10.1021/bi00393a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansson Ö, Andréasson LE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;679:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penner-Hahn JE, Fronko RM, Pecoraro VL, Yocum CF, Betts SD, Bowlby NR. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2549–2557. [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacLachlan DJ, Hallahan BJ, Ruffle SV, Nugent JHA, Evans MCW, Strange RW, Hasnain SS. Biochem J. 1992;285:569–576. doi: 10.1042/bj2850569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kusunoki M, Takano T, Ono T, Noguchi T, Yamaguchi Y, Oyanagi H, Inoue Y. In: Photosynthesis : from Light to Biosphere. Mathis P, editor. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 1995. pp. 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeRose VJ, Mukerji I, Latimer MJ, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:5239–5249. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wieghardt K. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1989;28:1153–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pecoraro VL. Manganese Redox Enzymes. VCH; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peloquin JM, Britt RD. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1503:96–111. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00219-x. [this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasegawa K, Ono TA, Inoue Y, Kusunoki M. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;300:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Åhrling KA, Smith PJ, Pace RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:13202–13214. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegbahn PEM. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:2923–2935. doi: 10.1021/ic9911872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berthold DA, Babcock GT, Yocum CF. FEBS Lett. 1981;134:231–234. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuwabara T, Murata N. Plant Cell Physiol. 1982;23:533–539. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghanotakis DF, Babcock GT, Yocum CF. FEBS Lett. 1984;167:127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boussac A, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1988;27:3476–3483. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lockett CJ, Demetriou C, Bowden SJ, Nugent JHA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1016:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ono TA, Inoue Y. FEBS Lett. 1988;227:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghanotakis DF, Babcock GT, Yocum CF. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;809:173–180. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ono TA, Inoue Y. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;275:440–448. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boussac A, Rutherford AW. Chem Scr. 1988;28A:123–126. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boussac A, Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8984–8989. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sivaraja M, Tso J, Dismukes GC. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9459–9464. doi: 10.1021/bi00450a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tso J, Sivaraja M, Dismukes GC. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4734–4739. doi: 10.1021/bi00233a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ädelroth P, Lindberg K, Andréasson LE. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9021–9027. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cammarata KV, Cheniae GM. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:587–595. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen JR, Satoh K, Katoh S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;933:358–364. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katoh S, Satoh K, Ohno T, Chen J-R, Kashino Y. In: Progress in Photosynthesis Research. Biggins J, editor. Martinus Nijhoff; Dordrecht: 1987. pp. I.5.625–628. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davis DJ, Gross EL. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;387:557–567. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(75)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han KC, Katoh S. Plant Cell Physiol. 1993;34:585–593. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen C, Kazimir J, Cheniae GM. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13511–13526. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Latimer MJ, DeRose VJ, Mukerji I, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10898–10909. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noguchi T, Ono TA, Inoue Y. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1228:189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seidler A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1277:35–60. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(96)00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacLachlan DJ, Nugent JHA, Bratt PJ, Evans MCW. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1186:186–200. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riggs-Gelasco PJ, Mei R, Ghanotakis DF, Yocum CF, Penner-Hahn JE. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2400–2410. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Booth PJ, Rutherford AW, Boussac A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1277:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cinco RM, Robblee JH, Rompel A, Fernandez C, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:8248–8256. doi: 10.1021/jp981658q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cinco RM, Robblee JH, Rompel A, Fernandez C, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. J Synchrotron Rad. 1999;6:419–420. doi: 10.1107/S0909049598017968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cinco RM. PhD Thesis. University of California; Berkeley, Berkeley, CA: 1999. LBNL Report 44 753. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boussac A, Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW, Lavergne J. Nature. 1990;347:303–306. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hallahan BJ, Nugent JHA, Warden JT, Evans MCW. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4562–4573. doi: 10.1021/bi00134a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gilchrist ML, Jr, Ball JA, Randall DW, Britt RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9545–9549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tang XS, Randall DW, Force DA, Diner BA, Britt RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7638–7639. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Latimer MJ, DeRose VJ, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:8257–8265. doi: 10.1021/jp981668r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lindberg K, Wydrzynski T, Vänngård T, Andréasson LE. FEBS Lett. 1990;264:153–155. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lindberg K, Andréasson LE. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14259–14267. doi: 10.1021/bi961244s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sandusky PO, Yocum CF. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;849:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sandusky PO, Yocum CF. FEBS Lett. 1983;162:339–343. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sandusky PO, Yocum CF. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;766:603–611. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ono T, Zimmermann JL, Inoue Y, Rutherford AW. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;851:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wincencjusz H, van Gorkom HJ, Yocum CF. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3663–3670. doi: 10.1021/bi9626719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wincencjusz H, Yocum CF, van Gorkom HJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3719–3725. doi: 10.1021/bi982295n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.DeRose VJ, Latimer MJ, Zimmermann JL, Mukerji I, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Chem Phys. 1995;194:443–459. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liang W, Roelofs TA, Olsen GT, Latimer MJ, Cinco RM, Rompel A, Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Klein MP. In: Photosynthesis: From Light to Biosphere. Mathis P, editor. Kluwer; Dordrecht: 1995. pp. 413–416. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liang W, Roelofs TA, Cinco RM, Rompel A, Latimer MJ, Yu WO, Sauer K, Klein MP, Yachandra VK. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3399–3412. doi: 10.1021/ja992501u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fernandez C, Cinco RM, Robblee JH, Messinger J, Pizarro SA, Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Klein MP. In: Photosynthesis: Mechanisms and Effects. Garab G, editor. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht: 1998. pp. 1399–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tang X-S, Diner BA, Larsen BS, Gilchrist ML, Jr, Lorigan GA, Britt RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:704–708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Westre TE, DiCicco A, Filipponi A, Natoli CR, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Hodgson KO. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:6757–6768. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mukerji I, Andrews JC, DeRose VJ, Latimer MJ, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9712–9721. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.George GN, Prince RC, Frey TG, Cramer SP. Phys B. 1989;158:81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 96.George GN, Cramer SP, Frey TG, Prince RC. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1142:240–252. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dau H, Andrews JC, Roelofs TA, Latimer MJ, Liang W, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5274–5287. doi: 10.1021/bi00015a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liang W, Latimer MJ, Dau H, Roelofs TA, Yachandra VK, Sauer K, Klein MP. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4923–4932. doi: 10.1021/bi00182a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Boussac A, Girerd JJ, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6984–6989. doi: 10.1021/bi960636w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4609–4615. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Beck WF, Brudvig GW. Biochemistry. 1986;25:6479–6486. doi: 10.1021/bi00369a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Britt RD, Zimmermann JL, Sauer K, Klein MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:3522–3532. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Peloquin JM, Campbell KA, Britt RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6840–6841. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lakshmi KV, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Frank HA, Brudvig GW. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:8327–8335. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Haumann M, Junge W. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1411:86–91. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Karge M, Irrgang KD, Renger G. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8904–8913. doi: 10.1021/bi962342g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rüttinger W, Dismukes GC. Chem Rev. 1997;97:1–24. doi: 10.1021/cr950201z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Messinger J, Badger M, Wydrzynski T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3209–3213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hoganson CW, Babcock GT. Science. 1997;277:1953–1956. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pecoraro VL, Baldwin MJ, Caudle MT, Hsieh WY, Law NA. Pure Appl Chem. 1998;70:925–929. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Matsukawa T, Mino H, Yoneda D, Kawamori A. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4072–4077. doi: 10.1021/bi9818570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ioannidis N, Petrouleas V. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5246–5254. doi: 10.1021/bi000131c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Siegbahn PEM, Crabtree RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:117–127. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Halfen JA, Mahapatra S, Wilkinson EC, Kaderli S, Young VG, Jr, Que L, Jr, Zuberbuhler AD, Tolman WB. Science. 1996;277:1953–1956. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5254.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hillier W, Messinger J, Wydrzynski T. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16908–16914. doi: 10.1021/bi980756z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]