Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum Erythrocyte Binding Antigen 175 (PfEBA-1751) engages Glycophorin A (GpA2) on erythrocytes during malaria infection. The two Duffy binding like domains (F13 and F24) of PfEBA-175 that form region II (RII5) are necessary for binding GpA, and are the target of neutralizing antibodies. Recombinant production of RII in P. pastoris and baculovirus has required mutations to prevent aberrant glycosylation or deglycosylation resulting in modifications to the protein surface that may affect antibody recognition and binding. In this study, we developed a recombinant system in E. coli to obtain RII and F2 without mutations or glycosylation through oxidative refolding. The system produced refolded protein with high yields and purity, and without the need for mutations or deglycosylation. Biophysical characterization indicated both proteins are well behaved and correctly folded. We also demonstrate the recombinant proteins are functional, and develop a quantitative functional flow cytometry binding assay for erythrocyte binding ideally suited to measure inhibition by antibodies and inhibitors. This assay showed far greater binding of RII to erythrocytes over F2 and that binding of RII is inhibited by a neutralizing antibody and sialyllactose, while galactose had no effect on binding. These studies form the framework to measure inhibition by antibodies and small molecules that target PfEBA-175 in a rapid and quantitative manner using RII that is unmodified or mutated. This approach has significant advantages over current methods for examining receptor-ligand interactions and is applicable to other erythrocyte binding proteins used by the parasite.

Keywords: PfEBA-175, Glycophorin A, Erythrocyte invasion, Duffy Binding Like Domain, Malaria, Oxidative refolding

INTRODUCTION

Malaria affects a third of the world's population and kills 1 million individuals annually. The clinical manifestations of malaria occur upon invasion and lysis of erythrocytes by Plasmodium parasites. As such, the blood-stage of Plasmodium parasites is an attractive target for the development of therapeutic interventions. Plasmodium falciparum Erythrocyte Binding Antigen of 175 kDa (PfEBA-1751) is a parasite protein ligand that binds to the erythrocyte receptor Glycophorin A during the blood-stage of the parasite life cycle [1–5]. PfEBA-175 is therefore an important antibody target and vaccine candidate [6–18].

PfEBA-175 is a member of the Erythrocyte Binding Like (EBL6) family of proteins [19]. The EBL family of proteins bind specific receptors during erythrocyte invasion of P. falciparum, and are involved in tight junction formation between the parasite and erythrocyte [1, 4, 5]. The EBL family is defined by the presence of cysteine-rich Duffy binding like (DBL7) domains [19]. PfEBA-175 contains two tandem DBL domains termed F1 and F2 that together form region II (RII – Figure 1A). RII is the erythrocyte binding domain [3], although F2 alone exhibited variable binding to erythrocytes when fused to hepatitis simplex virus glycoprotein D and expressed on the surface of COS cells [3]. No binding to erythrocytes for F1 alone was observed [3]. In addition to a direct role in red blood cell engagement, RII is a target for neutralizing antibodies [6–18].

Figure 1. Purification of recombinant RII and F2 results in monodisperse samples.

(A) Schematic showing the domains of PfEBA-175. F1 (green) and F2 (purple) are DBL domains that together form region II (RII). Signal sequence is in grey, C-terminal cysteine rich domain is in yellow, transmembrane domain is in dark blue and putative cytoplasmic domains are in light blue. (B) Size exclusion chromatography profile (left panel) and SDS-PAGE analysis (right panel) reveal single peaks and pure protein for (B) RII and (C) F2. Multi-angle static light scattering demonstrates (D) RII and (E) F2 are monodisperse and not crosslinked.

P. falciparum has limited N- and O-glycosylation capability and parasite proteins are essentially unglycosylated [20]. RII has been expressed in P. pastoris and the structure solved [21]. However, mutation of four residues to avoid aberrant glycosylation during expression was necessary. A baculovirus expression system for RII was also developed [22]. Once again a significant portion of the protein was glycosylated leading to heterogeneous protein. Finally, bacterial expression and refolding for RII [16] and the single DBL-domain F2 [23] of PfEBA-175 have been described. Using this system, F2 could be refolded with yields of 1 mg/L of E. coli culture [23].

Here, we optimize the production and purification of RII and F2, both untagged and 6x-His tagged, by expression in E. coli and oxidative refolding. We show the recombinant proteins are well behaved and correctly folded. Recombinant RII functionally binds erythrocytes and exhibits the same binding profile as full length PfEBA-175 from parasites with specific binding to Glycophorin A. RII exhibits greater binding to erythrocytes than F2 suggesting a role for both DBL domains in erythrocyte engagement. We develop a quantitative binding assay that facilitates rapid inhibition studies with small molecules and antibodies. This system provides high yields and purity for the DBL domains from PfEBA-175 without aberrant glycosylation or the need for mutations, and a rapid quantitative method to address binding to erythrocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and plasmids

RII DNA comprising amino acids 145 to 760, and F2 DNA comprising amino acids 449 to 760 of PfEBA-175 (Gene ID 2654998) were obtained by PCR using PfuUltra II hotstart DNA polymerase (Agilent # 600672) from genomic DNA of P. falciparum 3D7. For untagged proteins, DNA was cloned into the NcoI and XhoI restriction enzyme sites of pET-28 (Novagen) to yield pET-28-RII or pET-28-F2. To obtain pET-28-RII-His and pET-28-F2-His, DNA was cloned into the NdeI and XhoI restriction enzyme sites of pET-28 to yield an N-terminal 6-His tagged proteins. The plasmid sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Protein expression

E. coli Rosetta (DE3) were transformed by heat shock and grown in a 100 ml of LB supplemented with 30 μg/ml kanamycin overnight at 37 °C. 1 L of luria-broth supplemented with 30 μg/ml kanamycin was inoculated with 5 ml of overnight culture and grown at 37 °C to an O.D. of 0.6. Protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-galctopyranoside and allowed to proceed for 5 hours at 37 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 g for 30 minutes at 4 °C, lysed in 50 mM tris pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol, cOmplete protease inhibitor tablet (Roche # 04693159001), 1 mg/ml lysozyme, and disrupted by sonication. Inclusion bodies were separated by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 1 hour at 4 °C and the supernatant discarded.

Protein refolding

Recombinant proteins, untagged and 6x-His tagged, were extracted from inclusion bodies by incubation with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol overnight. Protein concentration was determined by diluting 2 uL of either protein or denaturing buffer in 98 uL of 5 M urea and reading the absorbance at 280 nm. 100 mg in 10 mL of denatured RII or F2 were rapidly diluted dropwise in 1 L of 400 mM L-arginine, 50 mM tris pH 8.0, 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride, 2 mM reduced glutathione, and 2 mM oxidized glutathione while stirring and allowed to refold for 48 hours at 4 °C. The refolded proteins were harvested by capture on sp sepharose fast flow resin (GE Healthcare). The sp sepharose fast flow resin was equilibrated with 25 mM MES pH 6.0, 100 mM NaCl. The refolded protein was diluted 1:4 in 50 mM MES pH 6.0, 50 mM NaCl and flowed over the resin. The resin was then washed with 25 mM MES pH 6.0, 100 mM NaCl. Finally, the protein was eluted with 25 mM MES pH 6.0, 500 mM NaCl and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff and a regenerated cellulose membrane for further purification.

Protein purification

The concentrated proteins were purified by size exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad superdex 200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl at 4 °C. Samples further purified by ion exchange chromatography on a HiTrapS column (GE Healthcare) eluted using a 50–1000 mM NaCl linear gradient in 25 mM MES, pH 6.0 at 4 °C. The protein was finally buffer exchanged into 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl using a superdex 200 10/300 GL column for RII and a superdex 75 10/300 GL column for F2 (GE Healthcare).

Multi-angle static light scattering

RII or F2 were injected onto a Waters 600S HPLC connected to a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column with a Waters 996 UV/VIS detector, a Wyatt Optilab-Tex refractive index detector, and a Wyatt Dawn-Heleos light scattering detector and run with 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl. Data were analyzed using Astra software to determine the experimental molecular weight of the resultant peak.

Small-angle x-ray scattering

SAXS data for RII and F2 at 1 mg/ml were collected at SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source using standard procedures [24]. Exposures were assessed for radiation damage and merged using PRIMUS [25] and merged data compared to crystal structure using CRYSOL [26]. Ab initio model generation was performed in DAMMIF [27] and aligned using SUPCOMB20 [28].

Erythrocyte binding assay

Flow cytometry assays have been developed to evaluate binding of Plasmodium proteins [29, 30], and a similar assay to quantify binding of PfEBA-175 domains to erythrocytes was developed. Anonymized erythrocytes were obtained from Zenbio. 500,000 erythrocytes were diluted in 500 μL DMEM with 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS). Varying concentrations of RII-His or F2-His were added to erythrocytes and incubated at room temperature for one hour. Erythrocytes were washed three times with 500 μl DMEM with 10 % FCS. FITC conjugated anti-6-His antibody (Invitrogen # R93325) was diluted 1:500 in DMEM with 10 % FCS. 100 μl of the diluted antibody was added to the washed erythrocytes and incubated at room temperature for one hour. The erythrocytes were then washed three times with 500 μl DMEM with 10 % FCS. Finally, erythrocytes were resuspended in 2 mL DMEM with 10 % FCS and analyzed by microscopy or using a BD FACScanto machine. For the salt dependence experiments, the buffer was altered to DMEM with 10 % FCS and 100 mM NaCl. Some clumping of cells upon incubation with RII was observed that was abolished in the presence of 100 mM NaCl. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software. For erythrocyte treatments and inhibition by the anti-Glycophorin A antibody, RBCs were incubated with either 2 mg/mL Trypsin, 1 mg/mL Chymotrysin, or 20 μl of anti-GpA (Santa Cruz Biosystems) overnight at 4 °C. The treated erythrocytes were used in binding assays as described above.

Inhibition studies

1 μM RII-His in DMEM with 10 % FCS and 100 mM NaCl was incubated with various concentrations of α-2,3-sialyllactose (Carbosynth), galactose (Sigma) or the inhibitory antibody R217 [12, 16, 17] adjusted to a final concentration of 500 μl and the mixture incubated at 4°C overnight. The mixture was then added to 500,000 erythrocytes in a final volume of 500 μl and analyzed as above. Measurements at each concentration were conducted in triplicate. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

RESULTS

Production of RII and F2 with high yield and purity

Bacterial expression and refolding has proven successful for DBL domain containing proteins [31–36]. We investigated oxidative refolding for the double-DBL domain RII and the single DBL domain F2. Both constructs expressed insolubly as inclusion bodies in E. coli. To obtain recombinant proteins, denatured RII or F2 were extracted from inclusion bodies and oxidative refolding conditions investigated. Refolding conditions were optimized by varying time, arginine concentration and glutathione concentrations and ratio. The final condition reported in Materials and Methods produced the highest quality protein in each case.

A three step purification protocol was developed for both RII and F2 that included an initial size-exclusion step, followed by an ion-exchange polishing step and a final size-exclusion step to exchange the protein into the desired final buffer (Figure 1). This purification protocol resulted in >98 % pure RII and F2 as judged by SDS-PAGE with a final yield of 5 mg and 25 mg per liter of refolding, respectively (Figure 1B–C). In both cases the protein eluted after the final size-exclusion as a single peak (Figure 1B–C). Purification of the 6x-His tagged constructs resulted in protein of similar purity and yield as that of the untagged constructs.

Refolded RII and F2 are well behaved and correctly folded

To characterize the quality of the recombinant proteins, the molecular weight and monodispersity was determined using multiangle static light scattering (MASLS8). RII eluted as a single monodisperse peak with a molecular weight of 73 kDa consistent with the molecular weight of a monomer (Figure 1D). F2 also eluted as a single monodisperse peak with a molecular weight of 37 kDa consistent with the molecular weight for a single DBL domain (Figure 1E). Thus, the refolding protocols did not result in cross-linked oligomers as can sometimes occur with proteins with disulfide bridges. In addition, we examined the solution structure of the recombinant proteins by small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS9) to ensure the proteins were correctly folded. In both cases, the experimental SAXS profile closely matched the theoretical profile expected from the crystal structures. The crystal structure of RII fit the experimental scatter for recombinant RII with a χ2 of 1.87 (Figure 2A), and the crystal structure of F2 fit the experimental scatter for recombinant F2 with a χ2 of 1.08 (Figure 2B). The averaged ab initio molecular envelope also closely matched the expected structures. Together, these results demonstrate recombinant RII and recombinant F2 produced in E. coli are correctly folded.

Figure 2. Small-angle x-ray scattering of RII and F2.

The SAXS of (A) RII and (B) F2 indicate the recombinant proteins are correctly folded and match the theoretical scatter expected from crystal structures. The experimental (black) and theoretical SAXS profile (red) for the crystal structure of RII or F2 plotted as scattering intensity versus scattering momentum. The ab initio molecular envelopes (grey) are overlaid onto the crystal structure (F1 – green, F2 purple) in the insets. PDB entry 1ZRO was used to obtain structural models for both RII and F2.

A quantitative assay for RII engagement of erythrocytes

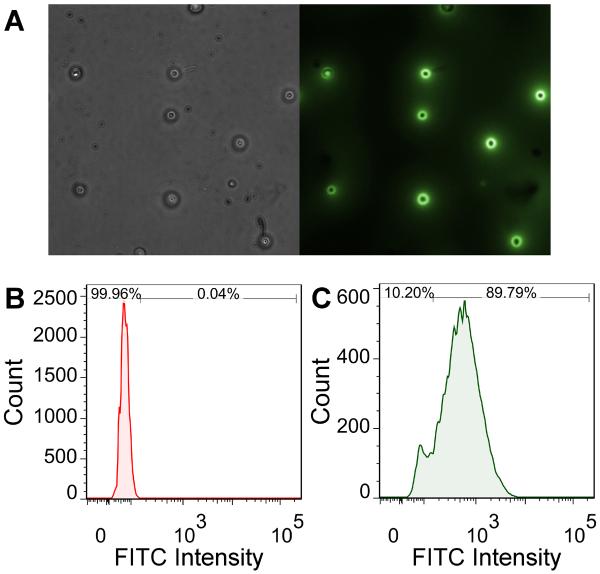

PfEBA-175 binds erythrocytes upon invasion by P. falciparum. RII is sufficient for erythrocyte binding and interacts with the receptor Glycophorin A. To determine if the recombinant RII was functional we developed a quantitative erythrocyte binding assay. RII with a 6-His tag was first incubated with erythrocytes followed by incubation with fluorescently labeled anti-6-His antibody. Erythrocytes that bound RII fluoresced upon microscopic examination (Figure 3A). This result demonstrated that recombinant RII was functional and could engage the receptor Glycophorin A on erythrocytes. This assay was adapted to allow for quantification of binding by flow cytometry (Figure 3B–C). A clear shift in the histogram upon the addition of RII demonstrated the labeling was specific to RII (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. A quantitative binding assay.

(A) Erythrocytes were labeled with recombinant RII and stained with a FITC conjugated anti-6x-His antibody. Left panel: bright-field. Right panel: FITC channel. (B) Representative flow cytometry profile for erythrocytes. (C) Representative flow cytometry profile for erythrocytes labeled with recombinant RII. Gates used to quantify unlabeled and labeled populations are indicated at the top of the plot with percentages for each sample

To further examine if RII binding to erythrocytes was specific to Glycophorin A we investigated binding to enzyme treated erythrocytes (Figure 4). PfEBA-175 binding to erythrocytes is chymotrypsin resistant and trypsin sensitive as Glycophorin A is resistant to chymotrypsin but sensitive to trypsin [3]. Treatment of erythrocytes with trypsin resulted in a complete loss in binding of recombinant RII to erythrocytes while chymotrypsin had no effect. To ensure binding was specific to GpA, we demonstrate an anti-GpA antibody prevented RII binding. Together, these results show that recombinant RII produced by oxidative refolding is correctly folded and functional for binding to GpA on erythrocytes.

Figure 4. Erythrocyte binding by RII measured by flow cytometry, plotting median fluorescence intensity (MFI) against enzyme treatment.

Trypsin treatment of erythrocytes or addition of an anti-Glycophorin A antibody prevent binding of recombinant RII-His, while chymotrypsin treatment has no effect.

RII binds erythrocyte far better than F2 alone

Erythrocytes labeled with and without RII or F2 at various concentrations were examined by the quantitative assay. RII at concentrations from 0.5 to 20 μM bound erythrocytes in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A and E). Addition of 100 mM salt to the reaction resulted in a linear dose-dependence (Figure 5B and F). Strikingly, F2 alone was unable to bind erythrocytes at any protein or salt concentration tested (Figure 5C–F). This result suggests that both DBL domains of PfEBA-175 are required for high affinity binding to erythrocytes consistent with structural studies of binding [21].

Figure 5. RII binds to erythrocytes with higher affinity than F2.

Flow cytometry analysis for (A) RII-His binding in the presence of DMEM; (B) RII-His binding in the presence of DMEM supplemented with 100 mM NaCl; (C) F2-His binding in the presence of DMEM; and (D) F2-His binding in the presence of DMEM supplemented with 100 mM NaCl. (E) Quantification of binding by plotting median fluorescence intensity (MFI) against concentration of ligand in DMEM. (F) Quantification of binding by plotting median fluorescence intensity (MFI) against concentration of ligand in DMEM supplemented with 100 mM NaCl results in a linear range.

Inhibition of RII binding by antibodies and small molecules

Binding of PfEBA-175 to erythrocytes is sialic-acid dependent and sialic-acid analogs have been examined as potential inhibitors [4, 37]. However, accurate IC50 determination has not been possible due to the limitations of the experimental setup. We determined the IC50 of α-2,3-sialyllactose, galactose and a neutralizing antibody R217 [12, 16] using the quantitative binding assay (Figure 6). A clear dose response inhibition curve was obtained for α-2,3-sialyllactose with an IC50 of 13.9 mM (Figure 6A). This high IC50 is expected as sialic-acid and analogs are poor inhibitors of parasite growth and binding to Glycophorin A [3, 37]. Galactose had no effect on binding as expected demonstrating the specificity of inhibition (Figure 6B). Inhibition by R217 also revealed a clear dose-response curve with an IC50 of 104 nM (Figure 6C). This result demonstrates the feasibility of this assay for antibody-inhibition determination.

Figure 6. Inhibition of RII-His erythrocyte binding by α-2,3-sialyllactose and the inhibitory antibody R217.

(A) Inhibition by α-2,3-sialyllactose results in a characteristic dose response curve with an IC50 of 13.9 mM. (B) Galactose is unable to inhibit binding. (C) Inhibition by R217 results in a characteristic dose response curve with an IC50 of 104 nM.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed an expression and purification protocol for recombinant RII and F2 with high yield and purity. This system allows for the production of glycosylation and mutation free proteins in E. coli. We also demonstrate the recombinant proteins are well behaved, correctly folded and functional. Lastly, we developed a quantitative binding assay to examine binding and inhibition of recombinant RII to erythrocytes. Quantification of binding for RII and F2 revealed RII has far greater affinity for erythrocytes than F2, suggesting a role for both DBL domains in high affinity binding. This is consistent with previous results where robust binding of erythrocytes to RII was consistently observed, while binding to F2 alone was variable and no binding by F1 alone was observed [3]. Structural studies of RII also suggested a role for both DBL domains in Glycophorin A engagement [21]. Recombinant RII binds with the same binding properties as PfEBA-175. RII binding to erythrocytes is inhibited by an anti-GpA antibody, α-2,3-sialyllactose and the neutralizing antibody R217 demonstrating a specific interaction with the host receptor. In addition, recombinant RII is recognized by sera from individuals living in endemic areas, and antibodies affinity purified by RII prevent parasite growth [18]. These studies further validate the potential for the use of recombinant RII described here in vaccine development and diagnostics to measure the immune response.

This system allows for rapid screening for the inhibition of binding by small molecules and antibodies. RII is a target for neutralizing antibodies [6–18] although not all antibodies that engage RII are inhibitory [12, 16]. The assay returns a quantitative measurement of inhibition that can be used to identifying and rank antibodies on their potential to block binding. The development of recombinant RII from E. coli without the need for mutations and without aberrant glycosylation ensures that mutations and glycosylation do not alter antibody epitopes in RII. Therefore, antibody binding to all potential epitopes should be identified that may be missed when using higher eukaryotic expression systems [21, 22].

The quantitative binding assay has significant advantages over the gold standard rosette assay for identifying and examining receptor-ligand interactions for the EBL family [3, 21, 31–33, 38–42]. In the rosette assay, EBL ligands are transiently transfected for surface expression in mammalian cells. Binding is assayed by clustering of erythrocytes over a transfected cell. While this assay has been instrumental in identifying and examining interactions it suffers from several drawbacks. The clustering of ligands by fusion to transmembrane segments for expression on the cell surface will affect the oligomeric state and local concentration of ligands. In addition, mammalian cells can post-translationally modify expressed proteins and these modifications may prevent or enhance binding. The rosette assay also relies on microscopic examination and counting which is tedious and not amenable to high-throughput screening.

The quantitative assay circumvents all these drawbacks. Since RII is expressed and purified, the concentration of RII is controlled. There is no artificial clustering of RII due to fusion to unnecessary segments and post-translational modifications are absent due to the expression in bacteria. Lastly, the automation of quantification by flow cytometry allows for rapid and accurate measurements of binding. In summary, this system opens new avenues for the manipulation of RII and other EBL ligands towards understanding their function, mechanism and inhibition. It is anticipated that this expression and refolding system for RII is applicable to other EBL ligands and may aid in the development of a vaccine for malaria.

HIGHLIGHTS

PfEBA-175 RII and F2 were produced by oxidative refolding from E. coli

The system produces RII and F2 without the need for mutations or deglycosylation

SAXS and MASLS demonstrate RII and F2 are well behaved and correctly folded

RII functionally binds RBCs with the same profile as parasite derived PfEBA-175

A quantitative assay for antibody and small molecule inhibition is described

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Nelson, D. Fremont and G. Amarasinghe for assistance with MASLS. The project described was supported by grant number 080792 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation. Experimental support was also provided by the Facility of the Rheumatic Diseases Core Center under award number P30AR048335.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

PfEBA-175- Plasmodium falciparum Erythrocyte Binding Antigen 175

GpA – Glycophorin A

F1 – Duffy Binding Like Domain F1

F2- Duffy Binding Like Domain F2

RII - Region II of EBA175 consisting of F1 and F2

EBL – Erythrocyte Binding Like

DBL – Duffy Binding Like

MASLS – multiangle static light scattering

SAXS - small-angle x-ray scattering

Author Contributions. N.D.S. performed experiments, collected and analyzed the data. N.H.T designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- [1].Camus D, Hadley TJ. A Plasmodium falciparum antigen that binds to host erythrocytes and merozoites. Science. 1985;230:553–556. doi: 10.1126/science.3901257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sim BK, Orlandi PA, Haynes JD, Klotz FW, Carter JM, Camus D, Zegans ME, Chulay JD. Primary structure of the 175K Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte binding antigen and identification of a peptide which elicits antibodies that inhibit malaria merozoite invasion. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1877–1884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.5.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sim BK, Chitnis CE, Wasniowska K, Hadley TJ, Miller LH. Receptor and ligand domains for invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1994;264:1941–1944. doi: 10.1126/science.8009226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Orlandi PA, Klotz FW, Haynes JD. A malaria invasion receptor, the 175-kilodalton erythrocyte binding antigen of Plasmodium falciparum recognizes the terminal Neu5Ac(alpha 2–3)Gal- sequences of glycophorin A. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:901–909. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Orlandi PA, Sim BK, Chulay JD, Haynes JD. Characterization of the 175-kilodalton erythrocyte binding antigen of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;40:285–294. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90050-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Okenu DM, Riley EM, Bickle QD, Agomo PU, Barbosa A, Daugherty JR, Lanar DE, Conway DJ. Analysis of human antibodies to erythrocyte binding antigen 175 of Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5559–5566. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5559-5566.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Osier FH, Fegan G, Polley SD, Murungi L, Verra F, Tetteh KK, Lowe B, Mwangi T, Bull PC, Thomas AW, Cavanagh DR, McBride JS, Lanar DE, Mackinnon MJ, Conway DJ, Marsh K. Breadth and magnitude of antibody responses to multiple Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens are associated with protection from clinical malaria. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2240–2248. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01585-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Richards JS, Stanisic DI, Fowkes FJ, Tavul L, Dabod E, Thompson JK, Kumar S, Chitnis CE, Narum DL, Michon P, Siba PM, Cowman AF, Mueller I, Beeson JG. Association between naturally acquired antibodies to erythrocyte-binding antigens of Plasmodium falciparum and protection from malaria and high-density parasitemia. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;51:e50–60. doi: 10.1086/656413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jiang L, Gaur D, Mu J, Zhou H, Long CA, Miller LH. Evidence for erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 as a component of a ligand-blocking blood-stage malaria vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7553–7558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104050108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McCarra MB, Ayodo G, Sumba PO, Kazura JW, Moormann AM, Narum DL, John CC. Antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte-binding antigen-175 are associated with protection from clinical malaria. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2011;30:1037–1042. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822d1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lopaticki S, Maier AG, Thompson J, Wilson DW, Tham WH, Triglia T, Gout A, Speed TP, Beeson JG, Healer J, Cowman AF. Reticulocyte and erythrocyte binding-like proteins function cooperatively in invasion of human erythrocytes by malaria parasites. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1107–1117. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01021-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sim BK, Narum DL, Chattopadhyay R, Ahumada A, Haynes JD, Fuhrmann SR, Wingard JN, Liang H, Moch JK, Hoffman SL. Delineation of stage specific expression of Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 by biologically functional region II monoclonal antibodies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ord RL, Rodriguez M, Yamasaki T, Takeo S, Tsuboi T, Lobo CA. Targeting sialic acid dependent and independent pathways of invasion in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pandey AK, Reddy KS, Sahar T, Gupta S, Singh H, Reddy EJ, Asad M, Siddiqui FA, Gupta P, Singh B, More KR, Mohmmed A, Chitnis CE, Chauhan VS, Gaur D. Identification of a Potent Combination of Key Plasmodium Falciparum Merozoite Antigens That Elicit Strain Transcending Parasite Neutralizing Antibodies. Infect Immun. 2012 doi: 10.1128/IAI.01107-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Williams AR, Douglas AD, Miura K, Illingworth JJ, Choudhary P, Murungi LM, Furze JM, Diouf A, Miotto O, Crosnier C, Wright GJ, Kwiatkowski DP, Fairhurst RM, Long CA, Draper SJ. Enhancing blockade of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion: assessing combinations of antibodies against PfRH5 and other merozoite antigens. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002991. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen E, Paing MM, Salinas N, Sim BK, Tolia NH. Structural and Functional Basis for Inhibition of Erythrocyte Invasion by Antibodies that Target Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003390. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ambroggio X, Jiang L, Aebig J, Obiakor H, Lukszo J, Narum DL. The Epitope of Monoclonal Antibodies Blocking Erythrocyte Invasion by Plasmodium falciparum Map to The Dimerization and Receptor Glycan Binding Sites of EBA-175. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Badiane AS, Bei AK, Ahouidi AD, Patel SD, Salinas N, Ndiaye D, Sarr O, Ndir O, Tolia NH, Mboup S, Duraisingh MT. Inhibitory humoral responses to the Plasmodium falciparum vaccine candidate EBA-175 are independent of erythrocyte invasion pathway. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2013 doi: 10.1128/CVI.00135-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Adams JH, Sim BK, Dolan SA, Fang X, Kaslow DC, Miller LH. A family of erythrocyte binding proteins of malaria parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7085–7089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gowda DC, Davidson EA. Protein glycosylation in the malaria parasite. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tolia NH, Enemark EJ, Sim BK, Joshua-Tor L. Structural basis for the EBA-175 erythrocyte invasion pathway of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Cell. 2005;122:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liang H, Narum DL, Fuhrmann SR, Luu T, Sim BK. A recombinant baculovirus-expressed Plasmodium falciparum receptor-binding domain of erythrocyte binding protein EBA-175 biologically mimics native protein. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3564–3568. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3564-3568.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pandey KC, Singh S, Pattnaik P, Pillai CR, Pillai U, Lynn A, Jain SK, Chitnis CE. Bacterially expressed and refolded receptor binding domain of Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 elicits invasion inhibitory antibodies. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;123:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hura GL, Menon AL, Hammel M, Rambo RP, Poole FL, 2nd, Tsutakawa SE, Jenney FE, Jr., Classen S, Frankel KA, Hopkins RC, Yang SJ, Scott JW, Dillard BD, Adams MW, Tainer JA. Robust, high-throughput solution structural analyses by small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) Nat Methods. 2009;6:606–612. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Konarev PV, Volkov VV, Sokolova AV, Koch MHJ, Svergun DI. PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2003;36:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL - a Program to Evaluate X-ray Solution Scattering of Biological Macromolecules from Atomic Coordinates. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 1995;28:768–773. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Franke D, Svergun DI. DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2009;42:342–346. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kozin MB, Svergun DI. Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2001;34:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Siddiqui FA, Dhawan S, Singh S, Singh B, Gupta P, Pandey A, Mohmmed A, Gaur D, Chitnis CE. A thrombospondin structural repeat containing rhoptry protein from Plasmodium falciparum mediates erythrocyte invasion. Cellular microbiology. 2013;15:1341–1356. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tran TM, Moreno A, Yazdani SS, Chitnis CE, Barnwell JW, Galinski MR. Detection of a Plasmodium vivax erythrocyte binding protein by flow cytometry. Cytometry Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2005;63:59–66. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Batchelor JD, Zahm JA, Tolia NH. Dimerization of Plasmodium vivax DBP is induced upon receptor binding and drives recognition of DARC. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:908–914. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lin DH, Malpede BM, Batchelor JD, Tolia NH. Crystal and solution structures of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte-binding antigen 140 reveal determinants of receptor specificity during erythrocyte invasion. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36830–36836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Malpede BM, Lin DH, Tolia NH. Molecular Basis for Sialic Acid-dependent Receptor Recognition by the Plasmodium falciparum Invasion Protein Erythrocyte-binding Antigen-140/BAEBL. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12406–12415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.450643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Singh S, Pandey K, Chattopadhayay R, Yazdani SS, Lynn A, Bharadwaj A, Ranjan A, Chitnis C. Biochemical, biophysical, and functional characterization of bacterially expressed and refolded receptor binding domain of Plasmodium vivax duffy-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17111–17116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Singh SK, Hora R, Belrhali H, Chitnis CE, Sharma A. Structural basis for Duffy recognition by the malaria parasite Duffy-binding-like domain. Nature. 2006;439:741–744. doi: 10.1038/nature04443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Batchelor JD, Malpede BM, Omattage NS, DeKoster G, Henzler-Wildman KA, Tolia NH. Red blood cell invasion by Plasmodium vivax: Structural basis for DBP engagement of DARC. PLoS Pathog. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003869. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bharara R, Singh S, Pattnaik P, Chitnis CE, Sharma A. Structural analogs of sialic acid interfere with the binding of erythrocyte binding antigen-175 to glycophorin A, an interaction crucial for erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;138:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chitnis CE, Miller LH. Identification of the erythrocyte binding domains of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium knowlesi proteins involved in erythrocyte invasion. J Exp Med. 1994;180:497–506. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chitnis CE, Chaudhuri A, Horuk R, Pogo AO, Miller LH. The domain on the Duffy blood group antigen for binding Plasmodium vivax and P. knowlesi malarial parasites to erythrocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1531–1536. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mayer DC, Kaneko O, Hudson-Taylor DE, Reid ME, Miller LH. Characterization of a Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte-binding protein paralogous to EBA-175. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5222–5227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081075398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mayer DC, Mu JB, Feng X, Su XZ, Miller LH. Polymorphism in a Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte-binding ligand changes its receptor specificity. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1523–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mayor A, Bir N, Sawhney R, Singh S, Pattnaik P, Singh SK, Sharma A, Chitnis CE. Receptor-binding residues lie in central regions of Duffy-binding-like domains involved in red cell invasion and cytoadherence by malaria parasites. Blood. 2005;105:2557–2563. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]