Abstract

We show that an Ng bridge function modified version of the three-dimensional reference interaction site model (3D-RISM-NgB) solvation free energy method can accurately predict the hydration free energy (HFE) of a set of 504 organic molecules. To achieve this, a single unique constant parameter was adjusted to the computed HFE of single atom Lennard-Jones solutes. It is shown that 3D-RISM is relatively accurate at predicting the electrostatic component of the HFE without correction but requires a modification of the nonpolar contribution that originates in the formation of the cavity created by the solute in water. We use a free energy functional with the Ng scaling of the direct correlation function [Ng, K. C. J. Chem. Phys.1974, 61, 2680]. This produces a rapid, reliable small molecule HFE calculation for applications in drug design.

1. Introduction

Hydration mediates many processes in nature, among which are protein folding, phase partitioning of chemicals, and protein–ligand binding. There is increasing interest in taking advantage of the water thermodynamics and structure in drug design. Indeed, methods such as WaterMap1−3 and GIST4 use explicit solvent simulations to score the stability of specific water sites in an enzymatic active site by the means of explicit solvent simulations. These methods have the disadvantage of being relatively slow, which opens the way for more approximate methods including GRID5−7 or SZMAP8 that treat water as a fluid lacking correlations interacting with a solute via an effective solvent potential as in the case of SZMAP. More approximate methods based on continuum solvent models can also capture certain aspects of hydration such as the high dielectric polarization9,10 of water. They have the advantage of being orders of magnitude faster than molecular simulations, but lack the packing and H-bonding structure of water, which greatly limits the behavior of the model where the size and anisotropy of water molecules matter.11 This is especially true in an enzyme active site. An intermediate approach using liquid state integral equations, called the three-dimensional reference interaction site model (3D-RISM),12−14 is very attractive for applications where the high dielectric polarization, the detailed interactions with a solute, and the multibody correlations of the solvent structure matters. The 3D-RISM method produces an approximate average solvent distribution around a rigid solute. It also offers a way to compute hydration free energy (HFE). It is orders of magnitude faster than molecular simulations and does not share the sequestered-water sampling problem that molecular simulations have. Compared to the independent particle approximation or continuum models, it has the advantage of treating water in a liquid state, incorporating the molecular correlations in an effective way.15

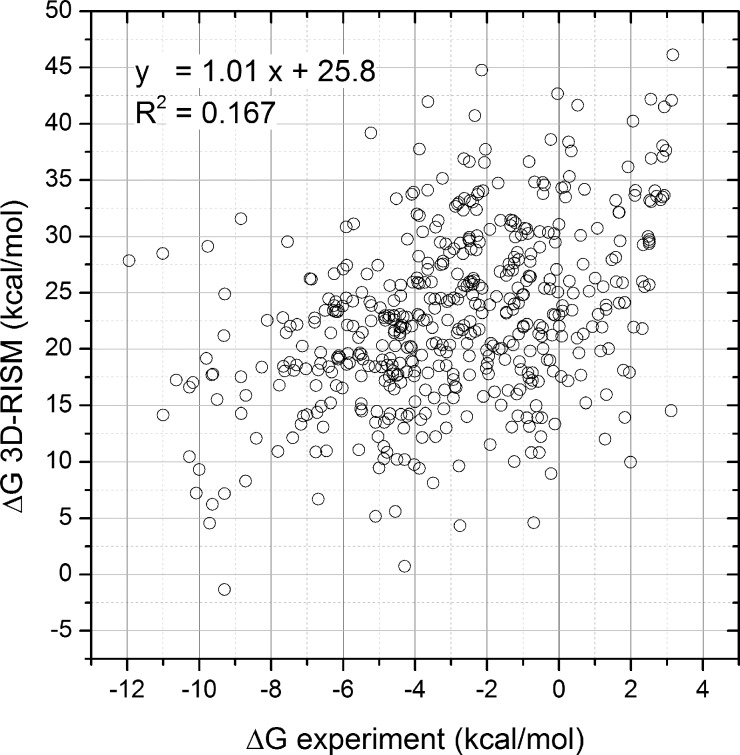

The 3D-RISM approach becomes an interesting alternative in many applications to the more traditional methods. However, a major weakness of the 3D-RISM is its poor ability to compute, with any reasonable accuracy, the hydration free energy (HFE) of organic solutes.16−18 This defect is related to the problem of all extended RISM theories in dealing with the thermodynamics of hydrophobicity.19 Figure 1 shows the inadequacy of the 3D-RISM with the KH closure HFEs for a set of 504 small organic molecules when compared to experimental results (c.f. section 3 for calculation details).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the 3D-RISM/KH prediction of the hydration free energy with experimental results for a set of 504 small organic molecules.

It is important to be able to calculate with sufficient accuracy the HFE of small solutes given that the equilibrium for ligand binding depends on both the direct interaction of the ligand as well as the desolvation penalty. Explicit solvent approaches such as WaterMap and GIST are scoring functions not designed to compute HFEs since these methods do not account, for example, for the cavity free energy. The independent particle methods and continuum approaches are also missing most of the cavity free energy and usually rely on surface area (SA) scaling20,21 or other approximate types of methods.22−25 It is known that SA types of approaches do not produce accurate cavity terms compared to more rigorous theoretical calculations.26−28

It is therefore of great interest to find a theoretical formalism to compute the full HFE including the cavity free energy component. In this article, we test 3D-RISM with the KH closure and the Ng modified free energy functional29 against converged explicit solvent simulations. We show that only a single component of the energy functional is responsible for most of the error correction. In the next sections, we first briefly review important aspects of the 3D-RISM/KH; we then show results and present our calculations.

2. Theory

The fundamental equations that lead to the practical framework we use can be derived using the variational principle in the density functional theory of liquids.30 This formally states that, given an external potential (e.g., the interaction potential coming from a solute), the true physical solvent distribution density minimizes the grand canonical potential functional. The Ornstein–Zernike type of integral equation such as the RISM approximation for molecular solvents,30,31 may be used to compute solvent density and thermodynamic functions that can be solved on a spatial grid. Alone, it is difficult to use this approach to treat complicated solutes such as drug-like molecules or proteins. The 3D-RISM method makes possible applications such as computing the HFE of more elaborate solutes.12,14 The idea is to fix a single solute (implying infinite dilution of the solute) and compute the solvent perturbation using any of a number of closures.15,32,33 The 3D-RISM equations with a suitable closure only need the solute and solvent potential parameters as input, typically from molecular two-body additive force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, etc.), and the solvent thermodynamic conditions (bulk solvent density, temperature, and composition). Once solved, the 3D-RISM equations yield approximate density distribution functions, direct correlation functions (DCF) for each H and for O in the case of pure water. The distribution function is the three-dimensional analog to the radial distribution function (also called pair distribution function). It gives the spatial density of the solvent atoms in the presence of a solute. The auxiliary DCFs are essential to relating the solvent distribution functions to the solvent free energy.

It is very convenient that, using thermodynamic integration, an exact equation can be derived for the HFE.17,34,35 The equivalent formalism applied to molecular simulations requires multiple simulations, each of which account for the variation of a transformation parameter.26,36−40 However, as previously shown, the approximate 3D-RISM HFEs lack sufficient accuracy when compared to either experiments or more rigorous simulation methods. This will be further demonstrated hereafter. In an attempt to improve the 3D-RISM HFEs, both theoretical and empirical approaches have been applied.15,33 The theoretical corrections had success on a limited number of molecules16,18 and focus on the improvement of the closure equation with additional so-called bridge terms. More recently, a technique called “universal correction” (UC) shows that, with a two parameter fit to the partial molar volume, the 3D-RISM HFE can be reasonably well corrected.41 The original UC is given by

| 1 |

where ΔGUC is the corrected hydration free energy in kcal/mol, ΔGKH is the 3D-RISM hydration free energy using the Kovalenko–Hirata (KH) closure in kcal/mol, ρ is the number density of bulk water (0.0333 molecule/Å3), and Vm is the partial molar volume in units of Å3/molecule.

The correction optimized by Palmer et al. is quite interesting.41 Here, we go beyond a fit to experimental hydration free energies. We find a correction optimized on computed quantities that ultimately only depends on fundamental atomic quantities derived from simulation and the thermodynamic state of the system. Also, our proposed method stems from correcting the analytical free energy functional found in 3D-RISM/KH and provides a better understanding of the nature of the HFE errors. To accomplish this, we fit with a single parameter based on a computed Lennard-Jones sphere HFE to obtain a demonstrably transferable constant that scales a well-known approximate bridge function.

In order to set the stage for what follows, it is useful to examine the equation used to calculate the HFE and derived, as stated above, directly from the thermodynamic formulation.13,35,42 The formulas and its approximation changes with different closure equations, but for the approximate KH closure one has

| 2 |

where kB is the

Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature in Kelvin

units, ρα is the bulk density of solvent center

α (0.0333 Å–3 for oxygen and 0.0666 Å–3 for hydrogen), and Δρα( ) is

the deviation of the solvent particle

density relative to bulk for the solvent center α. The position

dependent change in density can be written as Δρo(

) is

the deviation of the solvent particle

density relative to bulk for the solvent center α. The position

dependent change in density can be written as Δρo( ) = ρo(

) = ρo( ) –

ρo where ρo(

) –

ρo where ρo( ) is

the calculated oxygen density distribution

of water that results from the 3D-RISM calculations. The function

θ(x) is a Heaviside step function that effects

the quadratic term of the density deviation when the density is less

than bulk. Finally, the direct correlation function for a solvent

particle α is noted cα(

) is

the calculated oxygen density distribution

of water that results from the 3D-RISM calculations. The function

θ(x) is a Heaviside step function that effects

the quadratic term of the density deviation when the density is less

than bulk. Finally, the direct correlation function for a solvent

particle α is noted cα( ). The

solute–solvent interaction

potential, used in the 3D-RISM calculation, is defined as

). The

solute–solvent interaction

potential, used in the 3D-RISM calculation, is defined as

| 3 |

where the i summation is

over the solute centers, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity,

the atomic partial charges are denoted by q, and

the distance between the point  and

the ith solute atomic

center coordinate is given by ri. The standard Lennard-Jones potential is used where εi is the energy well depth associated with

the ith solute atom, εα is

the energy well depth associated with the α solvent particle,

and the Lennard-Jones atomic radius minima are denoted by σ.

and

the ith solute atomic

center coordinate is given by ri. The standard Lennard-Jones potential is used where εi is the energy well depth associated with

the ith solute atom, εα is

the energy well depth associated with the α solvent particle,

and the Lennard-Jones atomic radius minima are denoted by σ.

It is useful to point out at this stage that the HFE can be formally split into its nonpolar (np) and electrostatic (ele) components

| 4 |

Each of these terms can be calculated using molecular simulations and the free energy perturbation (FEP) technique using double decoupling for instance.11,36,43 The ΔGnp term corresponds to the work required to create a cavity with Lennard-Jones attractions in water, while all the atomic charges of the solute are zero. The ΔGele term corresponds to the work needed to restore the solute atomic partial charges in solution once the cavity is created. In other words, it is the cost (or gain) of the reorganization of the solvent when the solute Lennard-Jones volume recovers its full polarity. This separation of the total free energy commands a stepwise calculation with a specific order of decoupling in simulation where the atomic partial charges need to be zeroed before decoupling the Lennard-Jones parameters. These free energy quantities can also be computed individually with 3D-RISM using eq 2 in two steps: ΔGnp is calculated using eq 2 from a 3D-RISM/KH run with the solute atomic partial charges set to zero, and then ΔGele is computed using eqs 2 and 4.

We can rewrite eq 2 with the definition of

a free energy density function integrand for each solvent center α,

noted ΔGα( ), as

follows

), as

follows

| 5 |

which simplifies the notation when the volume of integration V is partitioned by a surface within which the solvent is excluded Vin and the part of space outside the exclusion domain Vext

| 6 |

Then, for the integral over Vin, ΔGKH is split into an electrostatic and a nonpolar component.

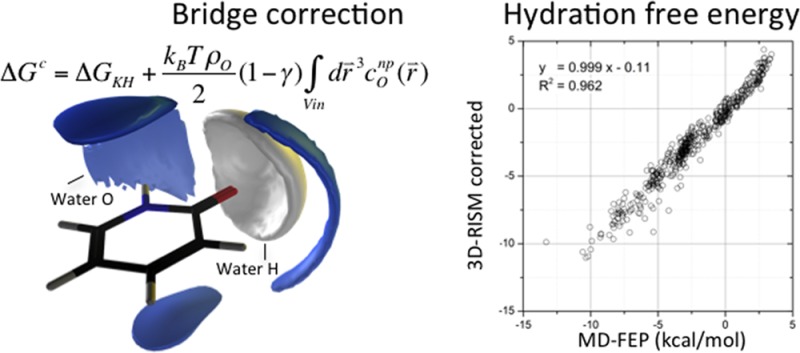

We wish to correct the behavior of the 3D-RISM/KH HFEs for the problematic behavior of the nonpolar component only. An effective bridge function correction29 to the HFE may be introduced by scaling the DCFs (c functions) in eq 5 by a constant γ yet to be determined. This leads directly to

| 7 |

from which one recovers eq 2 when the full

DCFs are used (γ = 1). It is useful to

note that the most positive contribution to ΔGKH comes from conp( ) inside the molecular core exclusion domain.

Also, the theoretical separation of the solvent water molecule densities

into oxygen and hydrogen in the exclusion domain should be dominated

by the repulsive core behavior (exclusion) of single water molecules.

This led us to consider the oxygen correction only given that the

packing is mainly represented by the oxygen L-J in most water models

) inside the molecular core exclusion domain.

Also, the theoretical separation of the solvent water molecule densities

into oxygen and hydrogen in the exclusion domain should be dominated

by the repulsive core behavior (exclusion) of single water molecules.

This led us to consider the oxygen correction only given that the

packing is mainly represented by the oxygen L-J in most water models

| 8 |

This leaves us with an equation with one adjustable parameter. The details of the mathematical steps can be found in the Supporting Information. We can optimize the free energy functional by adjusting the γ parameter following a strategy employed by others with bridge functions.16,32,44 We note that the bridge function correction proposed here is not computed self-consistently in the integral equation but only for the free energy form itself.

3. Calculation Details

Data Set

The 504 molecules used in this work come from a compilation done by Rizzo et al.45 and then enriched by Mobley et al.26 with extensive free energy perturbation results. The atomic partial charges, computed using AM1-BCC,46,47 and starting geometry come from the Supporting Information of Mobley et al.26

Force Field and Molecule Preparation

The small molecule Lennard-Jones parameters were set using the MOE48 assignment rules based on the OPLS parameters and functions.49 The solute geometries were optimized using MOE and the MMFF94 force field with the MOE 2011.10 RField implicit solvation model with a dielectric of 80 to account for the formation of intramolecular polar interactions. We used the c-TIP3P water model that was shown to reproduce the pair correlation function of pure water50 in simulation. It should be noted that the results for all RISM like integral equations are approximate.51 The atomic partial charge on the oxygen atom is −0.834 e̅, the εO = 0.156 kcal/mol, σO = 1.76827 Å, εH = 0.152 kcal/mol, and σH = 0.6938 Å. The OH distance is set to 0.9572 Å and the HOH angle to 104.52°. The main difference with the standard TIP3P water model is the addition of a hydrogen repulsive L-J term set to match the water dimer potential of the TIP3P water model and the water–water pair correlation functions, which eliminates the need for other approximations typically needed.16

RISM Calculations

The calculations were conducted using AmberTools, version 1.4. The Kovalenko–Hirata (KH) closure13 is used unless otherwise stated. The susceptibility response function of the pure liquid was computed using the AmberTools rism1d program based on the DRISM method.52 For that purpose, the grid spacing was set to 0.025 Å. The calculation was stopped when the direct correlation function residuals reached 10–12, the temperature was set to 298 K, and the water dielectric constant was set to 78.497. The water number density was set to 0.0333 molecule/Å3. The produced correlation functions were used as the input to the 3D-RISM program for which the grid spacing was set to 0.4 Å; the minimum distance between any atom of the solute and the boundary of the grid box was set to 10 Å. The water model was used to compute the solute–solvent potential energy. The periodic supercell background charge electrostatic was modified using the asymptotic charge correction.53 The calculation was converged to a direct correlation function residual of 10–5 per point. In all cases, the fast Fourier transform code from the library FFTW version 3 was used. The HFEs produced with these parameters had numerical errors around 0.1 kcal/mol. Our choice of calculation parameters allowed computation of HFEs within seconds instead of many tens of minutes as previously reported.41 This was achieved by reducing the grid density, by reducing the grid volume, and by lowering the convergence thresholds. The improved timings come from the combined effects of a careful scan of the parameters and the efficient MDIIS algorithm.17,54−56 The presented approach is orders of magnitude faster than explicit solvent simulation that typically requires thousands of CPU hours.

Calculation of the Solvent-Excluded Domain

The Vin region or interior volume was determined using the 3D-RISM calculation grid. At each grid point, the Lennard-Jones interaction potential between the water oxygen and the solute was calculated. Any point with a potential larger than 10 kcal/mol was considered as part of Vin and included as part of the integration domain of eq 8. Beyond 5 kcal/mol, the exact value is not important and leads to statistically identical results. The boundary threshold does not need to be fitted. What matters is that the water density must be very low. A threshold based on the Lennard-Jones potential as opposed to the water oxygen density has the advantage of decoupling the choice of the boundary from the 3D-RISM solution.

Statistical Analysis

The reported standard errors are estimated for the fitted parameters and the predicted quantities using 2000 samples in a bootstrap analysis.57

Results

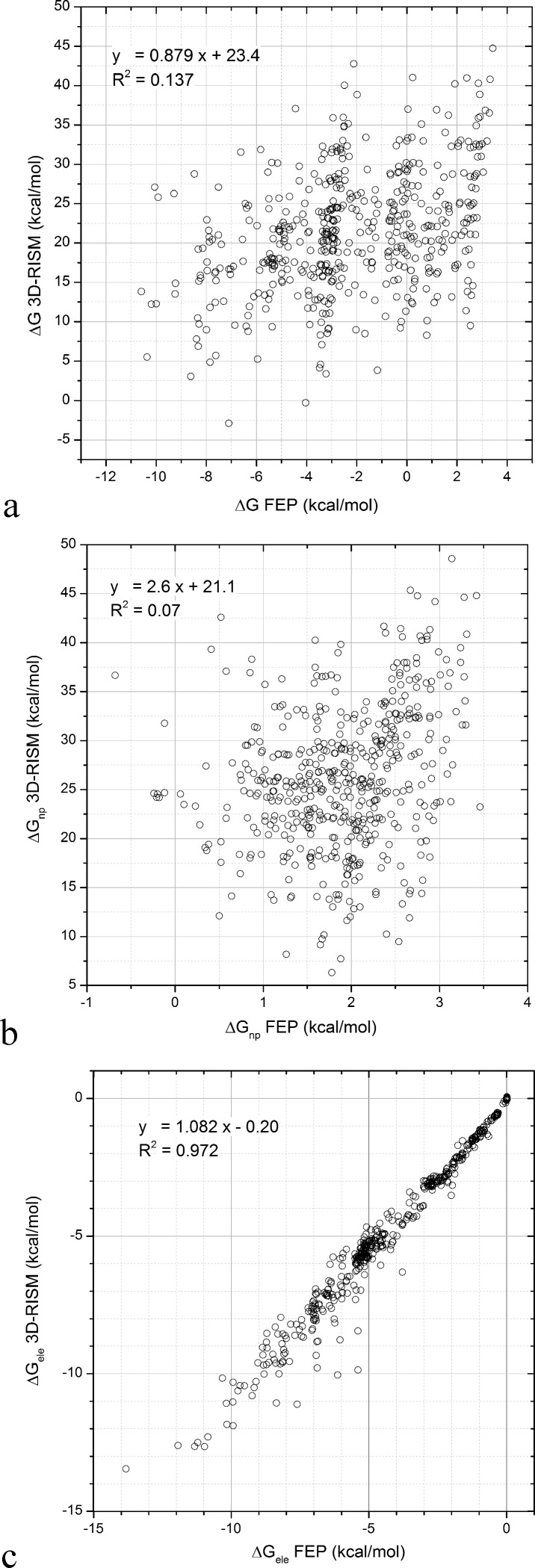

As mentioned in the Introduction, the calculated 3D-RISM/KH HFEs do not correlate well with either experimental or FEP values, as clearly shown in Figures 1 and 2a. Even more troubling, the dynamic range of the values calculated with 3D-RISM is not reasonable. Others have observed similar discrepancies for nonpolar molecules.16,18,58,59 This overestimation was attributed to the poor entropy of cavity formation.18,19 However, this explanation does not lead to a straightforward correction since the calculation of the entropy is not explicit in the formula. When the FEP-calculated HFE is partitioned into the nonpolar and electrostatic components, the 3D-RISM evaluation of the electrostatic components of the HFE correlates remarkably well, as shown in Figure 2c, given that no parameter is fitted. The slope is close to one and the y-axis intercept close to zero.

Figure 2.

Plots of ΔG FEP vs ΔG 3D-RISM, ΔGnp FEP vs ΔGnp 3D-RISM, and ΔGele FEP vs ΔGele 3D-RISM. The total 3D-RISM/KH hydration free energy (HFE) does not correlate with the simulation based free energy perturbation HFE (a). The nonpolar component of the HFE explains most of the errors (b) because the electrostatic component (c) of the HFE obtained with 3D-RISM correlates well with the FEP results.

The nonpolar contribution explains most of the variance observed in the residuals of the calculated HFEs as shown in Figure 2b. Therefore, ΔGnp needs to be corrected. Here, we use eq 8. It seems natural to simplify the problem to the calculation of the HFE of monatomic spherical Lennard-Jones (LJ) solutes, which by definition do not have atomic partial charge and bear the simplest molecular shape one can imagine. For this purpose, we used the data set of Fennell et al.28

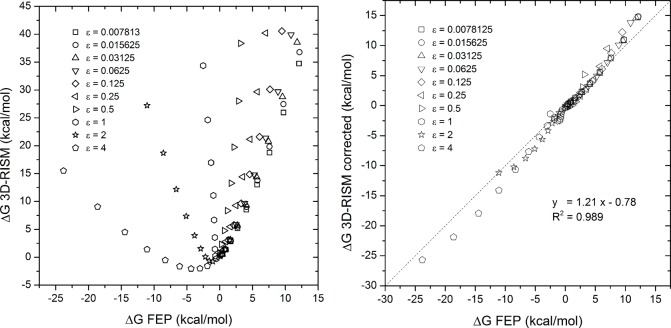

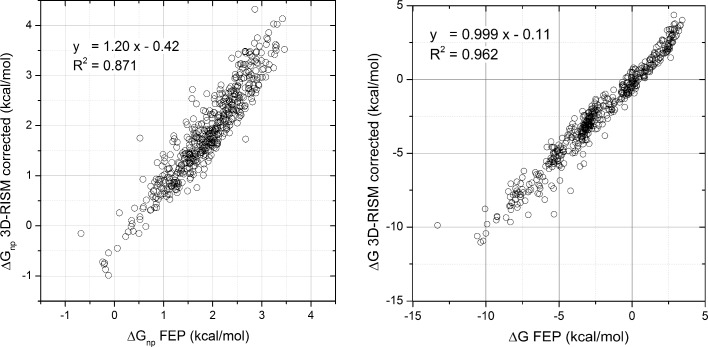

The optimization of the γ parameter in eq 8 to reproduce the calculated HFEs of the LJ monatomic solutes shows considerable improvement as demonstrated in Figure 3a and b (see also Figure 4). The DCF scaling factor obtained was γ = 0.380. To verify that it is not only valid for the solute of spherical shapes, it was also fitted to reproduce the ΔGnp of the Mobley data set. The obtained optimal value for γ is 0.379. Considering the error margins on the fit (c.f. Table 2), the two values are statistically indistinguishable, which suggests that the optimal value of γ is solute-shape-invariant, at least for molecules of the size and shape of our data set. Once again, the correction applied on the DCF in the solvent-excluded volume markedly improves the correspondence between the 3D-RISM and the calculated FEP ΔGnp as shown by the correlation graph illustrated in Figure 3a. Most notably, the dynamical ranges of both FEP and corrected 3D-RISM match; the correlation slope is close to one and the intercept close to zero. Using our corrected nonpolar 3D-RISM component and the electrostatic term leads to a corrected 3D-RISM HFE in good agreement with FEP. Indeed, with a single γ constant fitted to the LJ solute HFE, one cannot statistically distinguish FEP from 3D-RISM HFEs as shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

Plots of ΔG FEP vs ΔG 3D-RISM and vs ΔG 3D-RISM corrected. The optimization of the γ parameter in eq 8 improves the hydration free energy (HFE) correlation for a series of Lennard-Jones monatomic solutes as shown above, where (a) the initial 3D-RISM formula (c.f. eq 2) is applied and where (b) the correction is applied (c.f. eq 8) with γ = 0.38. The function y = x is shown as a reference.

Figure 4.

Plots of ΔGnp FEP vs ΔGnp 3D-RISM corrected and ΔG FEP vs ΔG 3D-RISM corrected. The corrected 3D-RISM nonpolar hydration free (HFE) energy (c.f. eq 8), using γ = 0.38 obtained by fitting monatomic Lennard-Jones solute HFEs, shows a significant improvement for both the nonpolar component and the total HFE over the original formulation.

Table 2. Fitted Parameters for the Different Hydration Free Energy Equations.

| ΔGc = ΔGKH + (1 – γ)·ΔGcavity (eq 8) | ||

|---|---|---|

| L-J sphere | small molecules | |

| γ | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.379 ± 0.002 |

| ΔGUC2 = ΔGKH + a·Vm + b | ||

|---|---|---|

| L-J spheres | small molecules | |

| a | –0.149 ± 0.007 | –0.1524 ± 0.0009 |

| b | 0.44 ± 0.7 | 1.47 ± 0.2 |

| ΔGUC1 = ΔGKH + a·Vm | ||

|---|---|---|

| L-J spheres | small molecules | |

| a | –0.146 ± 0.007 | –0.144 ± 0.001 |

Table 1 reports the accuracy and precision of the different models optimized. The repulsive bridge correction (RBC) from Kovalenko and Hirata18 was shown to improve the HFE of inert gas atoms, and we computed the HFE using their thermodynamic perturbation theory (TPT) approximation. Although we observed that the comparison with experimental results changed the R2 of the RBC-TPT model from 0.2 to 0.6, the ΔGnpR2 remains poor at a value of 0.16. We also fitted two additional models based on the UC correction. The refit was necessary because we used a more extensive data set and a different water model. It is interesting to observe that the fit on the LJ solute data set leads to statistically similar constants to those fit to the Mobley HFEs. Furthermore, the addition of a constant (b in Table 2) did not significantly improve the model. The universal correction previously reported was the UC2 form studied here.41 The fact that the corrections presented in Table 2 and using either the water-excluded domain or the more empirical approach based on the partial molar volume have similar accuracy is not too surprising since the partial molar volume is related to the solvent-excluded volume given that the former represents the volume of one solute in pure water.

Table 1. Hydration Free Energy Prediction Statistics against Experiment and Free Energy Perturbation Simulation.

| method | ΔGexp | ΔGFEP | ΔGnp | ΔGelec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-RISM (γ = 0.38 this work) | R2 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.967 ± 0.004 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.972 ± 0.005 |

| MUE | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | |

| MSE | 0.10 ± 0.06 | –0.57 ± 0.03 | –0.03 ± 0.02 | –0.54 ± 0.02 | |

| RMSE | 1.29 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | |

| 3D-RISM/KH | R2 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.972 ± 0.005 |

| MUEa | 24.4 ± 0.3 | 23.7 ± 0.3 | 24.2 ± 0.3 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | |

| MSEa | 24.4 ± 0.3 | 23.7 ± 0.3 | 24.2 ± 0.3 | –0.54 ± 0.02 | |

| RMSEa | 25.3 ± 0.3 | 24.7 ± 0.3 | 25.2 ± 0.3 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | |

| 3D-RISM RBC-TPT | R2 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.961 ± 0.005 |

| MUE | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.2 | 1.41 ± 0.05 | |

| MSE | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.2 | –1.4 ± 0.05 | |

| RMSE | 7.9 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 8.5 ± 0.2 | 1.75 ± 0.06 | |

| UC1 | R2 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.967 ± 0.005 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.970 ± 0.005 |

| MUE | 0.95 ± 0.04 | 1.05 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | |

| MSE | –0.35 ± 0.05 | –1.02 ± 0.03 | –0.78 ± 0.02 | –0.24 ± 0.02 | |

| RMSE | 1.24 ± 0.05 | 1.18 ± 0.03 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | |

| UC2 | R2 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.958 ± 0.005 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.970 ± 0.005 |

| MUE | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | |

| MSE | 0.27 ± 0.05 | –0.41 ± 0.03 | –0.150 ± 0.02 | –0.26 ± 0.02 | |

| RMSE | 1.18 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.04 |

Energies are in kcal/mol. MUE: mean unsigned error. MSE: mean signed error. RMSE: root-mean-square error.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that the 3D-RISM hydration free energy (HFE) with the KH closure formula is not accurate when used on a large data set of 504 small molecules for which experimental and double decoupling free energy perturbation (FEP) values are available from the literature. The decomposition of the HFE into its electrostatic and nonpolar components lead us to conclude that the electrostatic component of the HFE is reasonably well reproduced without any empirical fit, i.e., using standard molecular mechanics parameters for the Lennard-Jones potential and the AM1-BCC partial charge model. However, the nonpolar component of the HFE was the clear source of error. We have found that scaling the nonpolar oxygen-solute Ng-style direct correlation bridge function contribution to the HFE only over the solvent-excluded region using a single scaling constant γ brings the theoretically correct 3D-RISM formula to much better agreement with the corresponding simulated FEP and experimental values. It was also surprising that this single γ parameter is the same for Lennard-Jones monatomic solutes and for a diverse set of 504 small molecules. This γ-corrected HFE functional can simultaneously reproduce the high level FEP nonpolar HFEs, the FEP electrostatic HFEs, the FEP total HFEs, and the experimental HFEs of the set of 504 small molecules used in this study. It is important to realize that the optimal γ was not fit to experimental quantities but solely to computed quantities. Moreover the transferability of the γ parameter from a Lennard-Jones solute to small molecules suggests that it is a shape-independent property. Ultimately, it was derived from atomistic fundamental properties of a Lennard-Jones force field at a relevant thermodynamic state.

The ability of the γ-corrected 3D-RISM nonpolar free energy term to reproduce the FEP-calculated corresponding values is remarkable, and here we compare it to recent attempts using different methods. First, it was shown that surface area or volume based approximations do not correlate with the FEP nonpolar components.26−28 Previous attempts using the full dispersion solvent–solute terms were shown to be challenging and demonstrated poor transferability.23 Wagoner and Baker had optimized an approach based on a combination of the Weeks–Anderson–Chandler decomposition and scaled particle theory.60 In their work, they focus on the HFE of 11 alkanes and were able to match the FEP computed HFE with an R2 of 0.71 and an R2 of 0.38 against experimental results. The γ-corrected 3D-RISM values on this subset lead to an R2 of 0.72 versus FEP and 0.88 versus experimental results.

More recently, Chen et al. have developed a method based on a differential geometry approach with three free parameters that predicted the experimental HFE of 11 alkane molecules with a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of 0.12 kcal/mol. The corresponding γ-corrected 3D-RISM RMSE is 0.44 kcal/mol. In their article, they show that the RMSE on the prediction of the experimental HFE on 19 alkanes is 0.33 kcal/mol.61 The results of Chen et al.’s method’s ability is most likely due to their focus on alkanes, whereas we tried to cover a more broad range of chemical species. Finally, Guo et al.62 used a level-set based approach, called VISM-CFA, to compute the nonpolar component of the HFE. Using the Mobley data set, they report an R2 of 0.76 versus experimental results and of 0.84 versus FEP. Our corresponding results reported in Table 1 are 0.88 and 0.96, respectively. However, the VISM-CFA R2 for the nonpolar HFE component is only 0.42. Although encouraging, all these methods are either less accurate or more limited than the model developed here. Furthermore, the herein presented semiempirical method has strong theoretical underpinnings that only rely on theory and computed quantities.

Finally, the correction we found for the 3D-RISM formulation of hydration free energy shows that it accounts accurately for most of the physical phenomena involved in the hydration free energy of small molecules. The major asset in 3D-RISM is the computational expediency at which converged hydration functions can be calculated within a few seconds for small molecules. It is reasonable to think that this accuracy can translate into more complex environments such as protein binding sites. A proper demonstration based on experimental evaluations remains challenging due to the lack of high quality data available.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Andriy Kovalenko for providing the original 3D-RISM code implementing the repulsive bridge correction and the thermodynamic perturbation theory approximation. B.M.P. gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the National Institutes of Health (GM 037657), the National Science Foundation (CHE-1152876), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (H-0037).

Supporting Information Available

A table with the values for each of the molecules in the Mobley set together with the molecular coordinates are provided (txt files). The mathematical steps that lead to eqs 7 and 8 are provided (pdf). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Young T.; Abel R.; Kim B.; Berne B. J.; Friesner R. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 808–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel R.; Salam N. K.; Shelley J.; Farid R.; Friesner R. A.; Sherman W. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 1049–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder P. W.; Mecinovic J.; Moustakas D. T.; Thomas S. W.; Harder M.; Mack E. T.; Lockett M. R.; Heroux A.; Sherman W.; Whitesides G. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 17889–17894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen C. N.; Young T. K.; Gilson M. K. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 044101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodford P. J. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 849–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boobbyer D. N. A.; Goodford P. J.; McWhinnie P. M.; Wade R. C. J. Med. Chem. 1989, 32, 1083–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor M.; Cruciani G.; Watson K. a J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 4089–4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word J. M.; Geballe M. T.; Nicholls A. Abstr. Pap.—Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 240. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson M. K.; Honig B. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 1988, 4, 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp K. A.; Honig B. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1990, 19, 301–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley D. L.; Barber A. E.; Fennell C. J.; Dill K. A. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 2405–2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beglov D.; Roux B. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 7821–7826. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Hirata F. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 10095–10112. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Hirata F. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Perkyns J. S.; Lynch G. C.; Howard J. J.; Pettitt B. M. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 64106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q.; Beglov D.; Roux B. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 796–805. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Hirata F. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 7942–7957. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Hirata F. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 2793–2805. [Google Scholar]

- Howard J. J.; Perkyns J. S.; Choudhury N.; Pettitt B. M. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 1928–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitkoff D.; Sharp K. A.; Honig B. Biophys. Chem. 1994, 51, 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitkoff D.; Sharp K. A.; Honig B. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 1978–1988. [Google Scholar]

- Labute P. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1693–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulea T.; Wanapun D.; Dennis S.; Purisima E. O. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 4511–4520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. A.; Pickup B. T.; Nicholls A. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 608–640. [Google Scholar]

- Truchon J.-F.; Nicholls A.; Roux B.; Iftimie R. I.; Bayly C. I. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 1785–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley D. L.; Bayly C. I.; Cooper M. D.; Shirts M. R.; Dill K. A. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagoner J.; Baker N. A. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1623–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell C. J.; Kehoe C.; Dill K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 234–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K.-C. J. Chem. Phys. 1974, 61, 2680–2689. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J.-P.; McDonald I. R.. Theory of Simple Liquids, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D.; Andersen H. C. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 57, 1930–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Marucho M.; Montgomery Pettitt B. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 124107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J.; Pettitt B. M. J. Stat. Phys. 2011, 145, 441–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S. J.; Chandler D. Mol. Phys. 1985, 55, 621–625. [Google Scholar]

- Molecular Theory of Solvation; Hirata F., Ed.; Springer: Norwell MA, 2003; Understanding Chemical Reactivity Series, vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Free Energy Calculations: Theory and Applications in Chemistry and Biology; Chipot C., Pohorille A., Eds; Springer: New York, 2007; Springer Series in Chemical Physics, vol. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Bash P. A.; Singh U. C.; Langridge R.; Kollman P. A. Science 1987, 236, 564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman D. A.; Kollman P. A. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 2460. [Google Scholar]

- Zwanzig R. W. J. Chem. Phys. 1954, 22, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood J. G. J. Chem. Phys. 1935, 3, 300–313. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer D. S.; Frolov A. I.; Ratkova E. L.; Fedorov M. V J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 492101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S.; Luchko T.; Gusarov S.; Kovalenko A.; Ryde U. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 8505–8516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley D. L.; Dumont É.; Chodera J. D.; Dill K. A. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 2242–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell G. Mol. Phys. 1969, 16, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo R. C.; Aynechi T.; Case D. A.; Kuntz I. D. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2006, 2, 128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakalian A.; Bush B. L.; Jack D. B.; Bayly C. I. J. Comput. 2000, 21, 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jakalian A.; Jack D. B.; Bayly C. I. J. Comput. Chem. 2002, 23, 1623–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2012.10; Chemical Computing Group Inc.: Montreal Canada, 2012. www.chemcomp.com. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Maxwell D. S.; Tirado-Rives J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- Luchko T.; Gusarov S.; Roe D. R.; Simmerling C.; Case D. A.; Tuszynski J.; Kovalenko A. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 607–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt B. M.; Rossky P. J. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Perkyns J. S.; Pettitt B. M. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992, 190, 626–630. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Truong T. N. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 7458–7470. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Ten-no S.; Hirata F. J. Comput. Chem. 1999, 20, 928–936. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Hirata F. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 10391. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko A.; Hirata F. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 10403. [Google Scholar]

- An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Efron B., Tibshirani R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1993; Monograph on Statistics and Probability, p 57. [Google Scholar]

- Ten-no S. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 3724–3731. [Google Scholar]

- Sato K.; Chuman H.; Ten-no S. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 17290–17295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagoner J. A.; Baker N. A.; Bakert N. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 8331–8336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Zhao S.; Chun J.; Thomas D. G.; Baker N. A.; Bates P. W.; Wei G. W. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 084101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.; Li B.; Dzubiella J.; Cheng L.; McCammon J. A.; Che J. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 1778–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.