Abstract

Introduction

Previous studies performed in low- and middle-income countries have shown that nearly half of HIV-infected adults not eligible for antiretroviral therapy (ART) at the time of enrolment in care are lost to follow-up (LTFU). However, data about the attrition from enrolment in care to ART eligibility of HIV-infected children are scarce, especially outside sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

This is a retrospective study about the attrition before ART eligibility of 282 children ineligible for ART at enrolment in care in a cohort study in India. Multivariate analysis was performed using competing risk regression.

Results

During 5695 child-months of follow-up, three children died, 36 were LTFU and 144 became ART eligible. The cumulative incidence of attrition (mortality and LTFU) was 15.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.3-20.5) at five years, and the attrition rate was higher during the first year after enrolment in care. The cumulative incidence of LTFU and mortality was 14.4% (95% CI, 10.2-19.2) and 1.2% (95% CI, 0.3-3.3) at five years, respectively. Children with a 12-month AIDS risk <3% had a higher risk of LTFU (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR] 10.77, 95% CI 1.93-60.07) than those with a risk >4%. Those children whose father had died had a lower risk of LTFU (SHR 0.26, 95% CI 0.09-0.75) than those whose parents were alive and were living in a rented house. Children aged 10-14 had a lower risk of LTFU (SHR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03-0.55) than those aged 5-9 years.

Conclusion

In our setting, a substantial proportion of children ineligible for ART are lost to follow-up before ART eligibility, especially those with younger age, less severe immunosuppression or living with parents in poor socio-economic conditions. These findings can be used by HIV programmes to design interventions aimed at reducing the attrition of pre-ART care of HIV-infected children in India.

Keywords: India, rural, HIV, lost to follow-up, mortality, pediatrics, antiretroviral therapy, eligibility determination

Introduction

By the end of 2011, 99% of the 3.3 million HIV-infected children worldwide were living in low- or middle-income countries.1 The mortality of children infected with HIV is high,2,3 especially during the first two years of life, but antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces the hazard of mortality by 75%.4 However, only 28% of children who need ART are receiving it.1

Children diagnosed with HIV need to follow several stages prior to initiation of ART.5 After the HIV diagnosis is established, they need to engage in HIV medical care.6 Once they enter into care, children are assessed by clinical and immunological criteria to determine whether they are eligible for ART.7 Children who are ART ineligible are followed up until ART eligibility. Studies performed in adults have shown that ART ineligible patients have poor retention in care and approximately 50% are lost to follow-up (LTFU).8-10 However, data about the attrition in HIV-infected children ineligible for ART are scarce.11

With 145,000 children living with HIV, India has the highest burden of pediatric HIV in Asia.12 Of the 112,385 children registered in ART centers by December 2012, only 34,367 (30.6%) had started ART.12 The objective of this study is to describe the proportion of ART ineligible children who were LTFU before becoming eligible for ART in a cohort study in India. In particular, we aimed to find predictors of loss to follow-up, which could help HIV programmes design interventions aimed at reducing the attrition of HIV-infected children in India.

Methods

Setting and design

The study was performed in Anantapur, a rural district in South India. This is a retrospective analysis from the Vicente Ferrer HIV Cohort Study (VFHCS). The characteristics of the cohort have been described in detail elsewhere.6,13,14

For this study, we selected patients who were <15 years at the time of HIV diagnosis, diagnosed with HIV between January 1st 2007 and December 31st 2012, and who were not eligible for ART at the first assessment after enrolment in the Rural Development Trust (RDT) Bathalapalli Hospital. The selection of patients from the database was executed on July 15th 2013. ART eligibility was defined by clinical criteria (clinical stage 3 or 4 of the World Health Organization [WHO]) or by immunological criteria (CD4 count <1500 cells/µL or <25% in children aged <12 months; CD4 count <750 cells/µL or <20% in children aged 12-35 months; CD4 count <350 cells/µL or <15% in children aged 36-59 months; and CD4 count <350 cells/µL in children aged >59 months) according to the Indian National Guidelines.7 CD4 cell count determinations were performed every six months. Scheduled visits were performed at least every six months, but children could attend the clinics whenever it was needed.

In HIV-infected children <5 years, the CD4 lymphocyte percentage has generally been preferred for monitoring the immune status because of the variability of the CD4 cell count during the first years of life.15 However, a study of the HIV Paediatric Prognostic Markers Collaborative Study (HPPMCS) demonstrated that the CD4 percentage provides little or no additional prognostic value compared with the CD4 cell count in children.16 Therefore, for this study the immune status of children was calculated using the 12-month risk of AIDS used by the HPPMCS, which uses the CD4 cell count and the age of children to calculate the level of immunodeficiency.17 A high 12-month risk of AIDS indicates a low CD4 cell count for the age and the other way around. Because of the small number of older children included in the HPPMCS, children >12 years were censored at 12 years to calculate the 12-month AIDS risk.18

Definitions

The community of children was divided into four groups according to the positive discrimination schemes operated by the Government of India. People belonging to scheduled tribes (ST) are generally geographically isolated and have limited economic and social contact with the rest of the population. In the traditional Hindu caste hierarchy, the scheduled caste (SC) community was marginalized and suffered social and economic exclusion, and backward castes (BC) formed a collection of “intermediate” castes considered low in the traditional caste hierarchy, but above scheduled castes.19 Children who did not belong to any of these disadvantaged communities were included in the other castes (OC) group. Living near a town was defined as living in a mandal (administrative subdivision of districts) containing a town with a population >100,000 people.6 For those children whose parents were both alive, the parents were asked whether they lived in a rented house or in an owned house, as a marker of the economic conditions of the caregivers.

Statistical analysis and ethics statement

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software (Stata Corporation, Release 11, College Station, Texas, USA). To investigate predictors of loss to follow-up, time-to-event methods were used. Enrolment in care was defined as the date of the first CD4 cell count determination. Follow-up was defined as the time from the date of enrolment in care to ART eligibility or death, whichever occurred first.5 Children who did not die and did not become eligible for ART were censored at the last visit date. Children who did not come to the clinics for at least 180 days after their last visit date were considered LTFU.20 To avoid an overestimation of attrition, multivariate analysis and estimation of the cumulative incidence of LTFU were performed using competing risk proportional hazard models with ART eligibility as a competing event.6,21 The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the RDT Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 282 children from the VFHCS who were diagnosed with HIV from 2007 to 2012 and were not eligible for ART at the first assessment. The study included 5695.3 child-months and, during the study period, 144 became ART eligible, three children died and 36 were LTFU. Among children LTFU, the median time of follow-up was 4.1 months (interquartile range [IQR], 0.8-17.8; range 0-47.4) and the median time from enrolment in care to ART eligibility was 6.6 months (IQR, 3.2-14.9). Three children died after 6.5, 6.6 and 31.6 months from the enrolment in care.

Baseline characteristics at enrolment in care and the multivariate analysis of factors associated with LTFU are described in Table 1. The median age was 66 months (IQR, 42.7-95.9), over half were female, over half belonged to BC communities, 63% were living far from a town and 28% lived within 30 minutes from the clinics. Nearly half of the children had lost one or both of their parents, and the majority of those whose parents were alive were living in a rented house. Calculated using the age and the CD4 lymphocyte count at enrolment in care, the median estimated 12-month risk of AIDS was 3.3% (IQR 3-4, range 2.6-21.5). Children with a 12-month risk of AIDS <3% had a higher risk of LTFU (adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR] 10.77, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.93-60.07) than those with a 12-month risk of AIDS >4%. Those children whose father had died had a lower risk of LTFU (SHR 0.26, 95% CI 0.09-0.75) than those whose parents were alive and were living in a rented house. Children aged 10-14 had a lower risk of LTFU (SHR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03-0.55) than those aged 5-9 years.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with loss to follow-up before becoming eligible for antiretroviral therapy of 282 children in Anantapur, India.

| N (%) | SHR (95% CI) | aSHR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 0-1 | 27 (9.57) | 0.23 (0.03-1.72) | 0.54 (0.04-7.97) |

| 2-4 | 102 (36.17) | 0.80 (0.39-1.63) | 1.66 (0.46-6.06) |

| 5-9 | 117 (41.49) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 10-14 | 36 (12.77) | 0.50 (0.15-1.67) | 0.12* (0.03-0.55) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 148 (52.48) | 1.01 (0.52-1.94) | 1.15 (0.56-2.39) |

| Male | 134 (47.52) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Community | |||

| OC | 58 (20.57) | 1.16 (0.48-2.82) | 0.96 (0.35-2.65) |

| BC | 145 (51.42) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| SC | 63 (22.34) | 1.69 (0.75-3.81) | 1.31 (0.50-3.43) |

| ST | 16 (5.67) | 2.37 (0.85-6.56) | 2.36 (0.77-7.18) |

| Living near a town | |||

| No | 178 (63.12) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 104 (36.88) | 0.94 (0.48-1.84) | 0.89 (0.40-1.98) |

| Time to the clinics | |||

| ≤30 min | 79 (28.01) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| >30 min | 203 (71.99) | 2.00 (0.82-4.85) | 2.09 (0.73-5.96) |

| Year of enrolment | |||

| 2007 | 44 (15.6) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 2008 | 57 (20.21) | 0.78 (0.20-3.06) | 0.58 (0.14-2.44) |

| 2009 | 63 (22.34) | 1.64 (0.52-5.18) | 1.30 (0.36-4.69) |

| 2010 | 55 (19.5) | 2.03 (0.65-6.28) | 2.05 (0.62-6.76) |

| 2011 | 32 (11.35) | 2.05 (0.58-7.31) | 2.02 (0.51-8.00) |

| 2012 | 31 (10.99) | 3.07 (0.84-11.16) | 3.48 (0.97-12.51) |

| Status of parents | |||

| Alive, rented house | 81 (28.72) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Alive, owned house | 68 (24.11) | 0.84 (0.35-1.99) | 0.64 (0.24-1.69) |

| Father died | 71 (25.18) | 0.56 (0.22-1.39) | 0.26* (0.09-0.75) |

| Mother died | 32 (11.35) | 0.74 (0.25-2.26) | 0.51 (0.15-1.79) |

| Both died | 30 (10.64) | 0.59 (0.18-1.96) | 0.47 (0.14-1.57) |

| 12-month AIDS risk | |||

| <3% | 67 (23.76) | 3.02* (1.09-8.39) | 10.77* (1.93-60.07) |

| 3-3.4% | 117 (41.49) | 1.59 (0.56-4.50) | 1.34 (0.33-5.48) |

| 3.5-3.9% | 27 (9.57) | 2.36 (0.60-9.20) | 1.65 (0.33-8.28) |

| ≥4% | 71 (25.18) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

*p-value <0.05.

ART antiretroviral therapy; aSHR adjusted sub-distribution hazard ratio; BC backward castes; CI confidence interval; N number; OC other castes; SHR sub-distribution hazard ratio; SC scheduled castes; ST scheduled tribes.

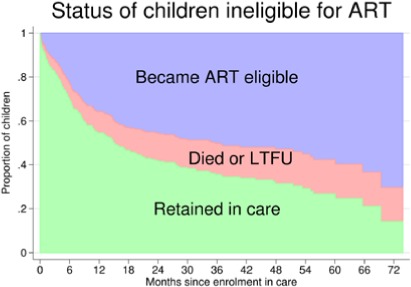

A stacked graph of the status of HIV-infected children since enrolment in care is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Stacked graph describing the cumulative incidence of antiretroviral therapy (ART) eligibility and loss to follow-up (LTFU) in 282 ART ineligible children in Anantapur, India.

The cumulative incidence of children who became eligible for ART was 22.9% (95% CI, 18.2-28) at 6 months, 35.7% (95% CI, 30.1-41.4) at 1 year, 45.4% (95% CI, 39.9-51.3) at 2 years, 50.3% (95% CI, 44-56.2) at 3 years, 52.9% (95% CI, 46.3-59) at 4 years, and 57.7% (95% CI, 50.2-64.5) at 5 years. The cumulative incidence of attrition before ART eligibility was 7.1% (95% CI, 4.5-10.5) at 6 months, 9.7% (95% CI, 6.6-13.5) at 1 year, 12.6% (95% CI, 9-16.9) at 2 years, 14.1% (95% CI, 10.2-18.6) at 3 years, and 15.6% (95% CI, 11.3-20.5) at 4 and 5 years. At five years, the cumulative incidence of LTFU and mortality was 14.4% (95% CI, 10.2-19.2) and 1.2% (95% CI, 0.3-3.3), respectively.

Discussion

The results of this study show that approximately 15% of ART ineligible children are LTFU before becoming eligible for ART. This proportion is substantially smaller than that of adults LTFU before ART eligibility in sub-Saharan Africa, which was 57.3% (95% CI, 34.3-80.2) in a meta-analysis study,8 or in a previous study from our cohort, which was 50% (95% CI, 47.7-53.2).9 We observed that the attrition rate was higher soon after enrollment in HIV medical care, indicating that interventions to reduce pre-ART attrition in children should place more emphasis during the first months after the enrolment in care.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to describe risk factors of LTFU among ART ineligible children from a resource-limited setting. Children with higher CD4 cell counts were more likely to be LTFU. Possibly these children had fewer HIV-related symptoms than those with more advanced immunodeficiency,22 so caregivers might have been more reluctant to come to the clinics if they felt the child was healthy. Interestingly, adults with higher CD4 cell counts were more likely to be LTFU from pre-ART care in two South-African studies,23,24 but this was not observed in adults from our cohort.9

Children whose parents were alive and living in a rented house were more likely to be LTFU, suggesting that children born in families with low economic conditions were more likely to have poorer retention in pre-ART care. In sub-Saharan Africa, some of the reasons that mothers mentioned for not taking their children to the clinics were transport costs, availability of food, time constraints due to work commitment, and lack of support from the male partner.25 In our setting, many families live in poor economic conditions,14 and in these families the health of an HIV-infected child may not be the first priority.26 Compared with older children, those aged 5-9 years had a higher risk of LTFU, indicating that caregivers looking after children within this range of age will need extra support. Children whose father had died were more likely to remain in pre-ART care, but the site offers nutritional support to widows. Therefore, this finding may not be generalized to other sites, but it suggests that the provision of nutritional support could be an effective measure to improve the retention in pre-ART care of children living in families with poor economic conditions.27

The study has some limitations. Children LTFU might not be lost forever, as they may reengage in the future or enroll in other HIV centers. However, studies performed in adults have shown high mortality in patients LTFU, and that patients with poor retention in pre-ART care who come back to the clinics have lower CD4 cell counts than patients retained in care.9,28 Probably because of the small sample size, the 95% confidence interval of the SHR for the 12-months AIDS risk was very wide, indicating that this estimate had low precision. New studies with larger number of children are needed to confirm this finding.

Conclusion

In our setting, 15% of children are LTFU before becoming ART eligible. Children with better immunological status, aged 5-9 years (compared with those aged >10 years), or living in families with poor economic conditions were at a higher risk of loss to follow-up. The attrition rate was higher during the first year of follow-up. These findings can be used by HIV programmes in India to design interventions aimed at reducing the attrition of HIV-infected children before the initiation of ART.

Acknowledgements

No external funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interests.

Authors' contributions: GAU contributed to the study concept and design, analysis, and manuscript preparation; PKN contributed to data acquisition and manuscript preparation; MM contributed to data acquisition and manuscript preparation; RK contributed to data acquisition and manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2012 UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. [Accessed on: December 5, 2012.]. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf.

- 2.Spira R, Lepage P, Msellati P, et al. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in children: a five-year prospective study in Rwanda. Mother-to-Child HIV-1 Transmission Study Group. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e56. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.5.e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newell ML, Coovadia H, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:1236–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmonds A, Yotebieng M, Lusiama J, et al. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the survival of HIV-infected children in a resource-deprived setting: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox MP, Larson B, Rosen S. Defining retention and attrition in pre-antiretroviral HIV care: proposals based on experience in Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1235–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez-Uria G, Naik PK, Midde M, Pakam R. Predictors of delayed entry into medical care of children diagnosed with HIV infection: data from an HIV cohort study in India. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:737620. doi: 10.1155/2013/737620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National AIDS Control Organisation. Guidelines for HIV Care and Treatment in Infants and Children. [Accessed on: July 31, 2013]. Available at: http://www.nacoonline.org/NACO/About_NACO/Policy__Guidelines/Policies__Guidelines1/

- 8.Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1509–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez-Uria G, Midde M, Pakam R, Naik PK. Predictors of attrition in patients ineligible for antiretroviral therapy after being diagnosed with HIV: data from an HIV cohort study in India. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:858023. doi: 10.1155/2013/858023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez-Uria G, Pakam R, Midde M, Naik PK. Entry, Retention, and Virological Suppression in an HIV Cohort Study in India: Description of the Cascade of Care and Implications for Reducing HIV-Related Mortality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2013;2013:384805. doi: 10.1155/2013/384805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mugglin C, Wandeler G, Estill J, et al. Retention in care of HIV-infected children from HIV test to start of antiretroviral therapy: systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National AIDS Control Organisation. India. HIV estimates 2012. Technical report. [Accessed on: July 22, 2013]. Available at: www.nacoonline.org/upload/Surveillance/Reports%20&%20Publication/Technical%20Report%20-%20India%20HIV%20Estimates%202012.pdf.

- 13.Alvarez-Uria G, Midde M, Pakam R, Kannan S, Bachu L, Naik PK. Factors Associated with Late Presentation of HIV and Estimation of Antiretroviral Treatment Need according to CD4 Lymphocyte Count in a Resource-Limited Setting: Data from an HIV Cohort Study in India. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:293795. doi: 10.1155/2012/293795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez-Uria G, Midde M, Pakam R, Naik PK. Gender differences, routes of transmission, socio-demographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV related infections of adults and children in an HIV cohort from a rural district of India. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4:e19. doi: 10.4081/idr.2012.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in infants and children: Towards universal access. [Accessed on July 10, 2013]. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/paediatric/infants2010/en/index.html. [PubMed]

- 16.HIV Paediatric Prognostic Markers Collaborative Study. Boyd K, Dunn DT, et al. Discordance between CD4 cell count and CD4 cell percentage: implications for when to start antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected children. AIDS. 2010;24:1213–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283389f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HIV Paediatric Prognostic Markers Collaborative Study. Predictive value of absolute CD4 cell count for disease progression in untreated HIV-1-infected children. AIDS. 2006;20:1289–94. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000232237.20792.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estimating risk of disease progression in HIV-infected children. Accessed on August 11, 2013Available at: http://www.hppmcs.org/

- 19.Alvarez-Uria G, Midde M, Naik PK. Socio-demographic risk factors associated with HIV infection in patients seeking medical advice in a rural hospital of India. J Public health Res. 2012;1:e14. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2012.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, et al. Universal definition of loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a statistical analysis of 111 facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchholz B, Hien S, Weichert S, Tenenbaum T. Pediatric aspects of HIV1-infection--an overview. Minerva Pediatr. 2010;62:371–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Cooke GS, Newell ML. Retention in HIV care for individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy: rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e79–86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182075ae2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson BA, Brennan A, McNamara L, et al. Early loss to follow up after enrolment in pre-ART care at a large public clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl. 1):43–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wachira J, Middlestadt SE, Vreeman R, Braitstein P. Factors underlying taking a child to HIV care: implications for reducing loss to follow-up among HIV-infected and -exposed children. SAHARA J. 2012;9:20–9. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2012.665255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhillon PK, Jeemon P, Arora NK, et al. Status of epidemiology in the WHO South-East Asia region: burden of disease, determinants of health and epidemiological research, workforce and training capacity. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:847–60. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WFP United Nations World Food Programme - Fighting Hunger Worldwide. HIV, AIDS, TB and Nutrition. [Accessed on January 21, 2014]. Available at: http://www.wfp.org/content/hiv-aids-tb-and-nutrition.

- 28.Brinkhof MWG, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]