Abstract

Significance: Revealing the basic mechanisms in the healing process and then regulating these processes for faster healing or to avoid negative outcomes such as infection or scarring are fundamental to wound research. The normal healing process is basically known, but to thoroughly understand the very complex aspects involved, it is necessary to characterize the course of events at a higher resolution with the latest molecular techniques and methodologies.

Recent Advances: Various animal models are used in wound-healing research. Rodent and pig models are the ones most often used, probably because of pre-existing sophisticated research methodologies and as the proper care and ethical use of these species are highly developed and organized to serve science throughout the world.

Critical Issues: Since several animal models are used, their anatomical and physiological differences varyingly affect the translation of results on healing mechanisms. Hence, to avoid species-specific misinformation, more ways to study wound healing directly in humans are needed.

Future Directions: Fortunately, novel techniques have enabled high-end molecular-level research even from small samples of tissue. Since these methods require only a small amount of patient skin, they make it possible to study wound healing directly in humans.

Kristo Nuutila, PhD

Scope and Significance

Although skin wound healing has been studied for decades, the molecular mechanisms behind the process are still not completely clear and most of the molecular-level understanding has been derived from various animal models. Species anatomical and physiological differences affect healing mechanisms varyingly, and thus different biological processes are always species specific. Hence, to avoid inaccurate interpretations due to species differences, more ways to study wound healing directly in humans are needed. Here, we describe the usefulness and limitations of these techniques for the characterization of human wound healing in a clinical setting.

Translational Relevance

Fortunately, novel techniques have enabled high-end molecular-level research even from small samples of tissue. Since these methods require only a small amount of patient skin, they make it possible to study wound healing directly in humans. With techniques such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), microarray, and RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), it is possible to investigate how different genes' expressions are altered in skin during trauma or disease. More importantly, these techniques offer an unbiased approach to the observation of healing.

Clinical Relevance

Revealing the basic mechanisms in the healing process and then regulating these processes for faster healing or to avoid negative outcomes such as infection or scarring are fundamental to wound research. The normal healing process is basically known, but to thoroughly understand the very complex aspects involved, it is necessary to approach these problems not only in the laboratory but in the clinic as well.

Background

Skin wounds are typically divided into acute and chronic wounds. Acute wounds are traumatic or surgical wounds that usually heal over time according to the normal wound-healing process. Acute skin wounds vary from superficial scratches to deep wounds with variable amounts of tissue loss and damage to blood vessels, nerves, muscles or other tissues, or internal organs.1 The larger the wound, the more intensive the body's response to injury. The systemic responses to trauma involve the body's inflammatory and immunomodulatory cellular and humoral networks. If these local and systemic responses fail to initiate recovery, their persistent activation may cause extensive organ damage.2

Acute wound healing is a complex physiological process that is regulated by many different cell types, growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines. Most of all, it is the body's inherent way of responding to injury for survival. During the healing process, cells such as inflammatory cells, platelets, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes undergo distinct preprogrammed changes in their gene expression and/or phenotype. In consequence, the wound environment progresses toward homeostasis through stages involving inflammation, new tissue formation, and, finally, tissue remodeling, that is, the classical phases of wound healing.3 The wound-healing program is an intricate interplay between several cell types involving various forms of intercellular signaling. Most wounds heal rather quickly and efficiently within several weeks according to the phases of normal wound healing.4

Since the skin serves as the protective barrier against physical and chemical threats, exposure to radiation or thermal stress, and pathogen entry, a wound radically compromises the functionality of the barrier.5 The wounded site is under constant microbial pressure, and, thus, a superficial skin wound is practically never sterile. Depending on the environment, size, and depth of the wound, as well as the patient's immunocompetence, treatment of wound infections ranges from easy to practically impossible. Given such a strong role of microbial colonization, one of the major objectives in wound-healing research is to elucidate and enhance the local antimicrobial defense mechanisms.6

Skin wounds and compromised wound healing are major concerns for the public health sector. Complex and lengthy treatments cause an increasing burden on healthcare expenses. Even in uncomplicated cases, burns, chronic and other difficult-to-treat wounds require surgery and extended hospitalization periods. In the United States alone, 6.5 million patients need treatment for chronic wounds and an estimated US$25 billion is spent annually. More worryingly, the burden is growing year by year mainly due to the increasing prevalence of obesity and diabetes.7

Wounds are defined as chronic when they have failed to proceed through an orderly and timely process without establishing a sustained anatomic and functional result. They are not capable of closure or regaining the anatomy and function of healthy skin. Usually, chronic wounds do not occur in healthy people. They are very often related to conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and old age. The majority of chronic wounds fall into three categories: pressure ulcers, arterial or venous ulcers, and diabetic ulcers. The pressure ulcers occur when skin or underlying tissue suffers injury due to direct pressure or pressure with shear forces. Constant pressure against the skin reduces the blood supply, and, thus, limited amounts of oxygen and nutrients reach the tissue. In venous ulcers, venous return is impaired, blood is packed in the superficial veins increasing intravenous pressure and causing perfusion defects. The diabetic ulcers have been closely associated with damage to the vasculature and nerves, immune system issues, and predisposition to infections that increasingly occur with disease progression. The biology of chronic wounds is still poorly understood. They do not follow the steps of the normal wound-healing process and remain in the inflammation phase. It has been proposed that the pathogenesis of impaired wound healing is based on four factors: bacterial colonization of the wound, ischemia, aging, and reperfusion injury.8

Discussion

Animal models

Various animal models have been used in wound-healing research. Rodent and pig models are the ones most often used, probably because the proper care and ethical use of these species is highly developed and organized throughout the world. Moreover, the extensive history of mice and rats as research models and the continuous development and improvement of various targeted genetic manipulations to single out a gene's role in a specific process—as well as specific research tools to serve these models, such as bioimaging—make these models highly lucrative. With these important developments, however, also comes a risk for error in sensitizing the model toward a predetermined result that better serves the researchers' goals and benefits. Even more importantly, the fact remains that although related, humans are a different species with specific differences in both physiological responses and pathological processes. The skins of different species vary by anatomical factors (thickness), physiological functions (blood flow), biochemical composition (lipids, enzymes), and they may have different receptors for immunological and pharmaceutical agents.9 The skin of rodents is loosely attached to the subcutaneous muscle layer (panniculus carnosus) and is covered with thick fur. Anatomically, both epidermis and dermis are thinner than the corresponding structures in human skin. More importantly, in these animals, wounds heal primarily through contraction instead of through re-epithelialization, as human partial-thickness wounds usually heal.10 In addition, stem cells of the hair follicles contribute to re-epithelialization, and, thus, the thick hair density of rodents affects the healing rate. Hence, although rodents are affordable as laboratory animals, their healing patterns differ substantially from those of humans.

Pigs are the animals whose biology and skin structure are closest to those of humans. These two species' epidermal/dermal ratios are very similar, as are their skin functions in terms of epidermal turnover time, types of keratinous proteins, and composition of lipids in the stratum corneum. Their circulation is also very similar; the blood vessels are of the same size and similarly oriented. In addition, pigs have no dense body hair and, as in humans, wound contraction caused by myofibroblasts is only a part of the healing process, whereas re-epithelialization is in most cases a more important mechanism.11 On the other hand, pigs are far more expensive than rodents and the healing pattern which often resembles that of human skin is not identical. Thus, there are differences between these two species: Pigskin has an additional interfollicular muscle, and the sweat glands are of the apocrine type and not the eccrine glands, which are postulated to be the main sources of epidermal repair in humans.12 Table 1 illustrates the differences between human, porcine, rat, and mouse skin.

Table 1.

Anatomical and physiological differences in skin of different species

| Thickness (μM) | Sweat Glands | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Epidermis | Dermis | Hair Follicle Density/cm2 | Apocrine | Eccrine | Panniculus Carnosus | Wound Healing |

| Human | <120 | <1,500 | 10 | Yes | Yes | No | Re-epithelialization |

| Porcine | <140 | <2,000 | 10 | Yes | No | Yes | Re-epithelialization |

| Rat | <55 | <700 | 290 | No | No | Yes | Contraction |

| Mouse | <25 | <500 | 660 | No | No | Yes | Contraction |

Species anatomical and physiological differences affect the mechanisms of healing and thus in order to study wound healing, one species and one model is not enough. To obtain a more complete understanding, the use of several species has been recommended. Essentially, however, mechanisms for different biological processes are always species specific, and, thus, the best species in which to study human wound healing is not pigs or rats but humans themselves. Hence, to avoid inaccurate interpretations due to species differences, more ways to study wound healing directly in humans are needed.

Problems in clinical wound-healing research

Understanding the basic mechanisms behind the wound-healing cascade and then discovering means to regulate them for faster healing or to avoid negative outcomes such as infection or scarring is very important to wound research. The normal healing process is basically known, but to thoroughly understand the very complex fine-tuned sequences, cell type and subtype kinetics, and the signaling pathways or intermediates involved, it is necessary to approach the problem in the laboratory as well as in the clinic.

Of importance are also the clinical problems encountered in human wounds research, such as heterogenicity of the wound etiology, differences in patient age, and comorbidities. Chronic wounds may be caused by arterial or venous insufficiency, infection, trauma, immobilization, or poor general condition. A plethora of factors, such as diabetes, arteriosclerosis, malnutrition, and malignancies, can drive or further contribute to the disease process. Thus, to have a coherent study group with similar individual wounds poses great demands. This also applies to the age of patients, because the etiologies of wounds in younger groups are different from those in the elderly. Perhaps the most difficult problem with clinical wounds is that there are very seldom two similar wounds which would enable both treatment and control sites in the same individual, that is, with a similar etiology and background (genetic background, associated diseases, or pharmacotherapy, etc). This means that to have enough power in the study, the number of participants should be very high, which causes practical problems. In addition to these difficulties, the endpoints of a clinical study may be difficult to define.13

Nonhealing wounds are a major clinical problem, and the requirements for performing a proper randomized controlled trial are enormous. There are many challenges that researchers should consider in planning the study. First of all, the study should be planned very carefully in accordance to ethical principles: How many patients and samples are needed, how large can the samples be, and how are the randomization and blinding executed? Careful planning, requesting for ethical permits, and recruiting appropriate patients require lengthy periods and long-term commitment. In addition, proper funding is essential; microarray and RNA-seq are very expensive techniques, and processing even a single sample can cost several hundreds of dollars. Genome-wide techniques produce enormous amounts of data, and for proper analysis a bona fide professional is needed.14,15

There is no standard clinical model available for chronic, nonhealing wounds, but the problem may be approached, to some extent, by studying normal wound healing. Split-thickness skin grafting is a standard procedure in many defects demanding skin cover; 0.01-inch- or 0.25-mm-thick grafts can be harvested in a very standardized way with a mechanical air-driven device (dermatome). The thickness can be adjusted but usually, the graft includes the entire epidermis and the upper part of the dermis. The donor site heals mainly from the epidermal cells of the skin appendages (sweat glands, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands) in 2–3 weeks. The usual donor site is the upper thigh, and a similar control wound can be obtained from the opposite extremity. Using the same patient as his/her own control dramatically diminishes the number of individuals needed for a trial.

Human wound-healing microarray studies

Although skin wound healing has been studied for decades, the molecular mechanisms behind the process are still not completely clear and most of the molecular-level understanding has been derived from various animal models. Fortunately, RNA- and DNA-based techniques have enabled molecular-level research even from a small sample of tissue. Since these methods require only a small amount of the patient skin, they make it possible to study wound healing directly in humans. With techniques such as the PCR and microarray, it is possible to investigate how different genes' expressions are altered in skin during trauma or disease. More importantly, these techniques offer an unbiased approach to the observation of healing.

So far, the utilization of microarrays in wound-healing research has been quite modest. Most of the molecular-level wound healing data have been obtained from various animal models. Several studies have clarified the role of specific genes in various wound models in animals.16,17 A few studies are available on gene expression in human wound healing. Some of these reports were based on samples that were collected for another purpose, or, alternatively, obtained from nonstandardized wounds. A comprehensive look at normal wound healing over time has been lacking. However, some interesting studies exist: Smiley et al. used microarrays to better understand molecular differences between cultured skin substitutes and native skin. Their gene expression analysis revealed that entire clusters of genes were either up- or down-regulated on a combination of fibroblasts and keratinocytes in cultured skin grafts. Furthermore, several categories of genes were overexpressed in cultured skin substitutes compared with native skin, including genes associated with hyperproliferative skin or activated keratinocytes.18 In another study, Chen et al.19 investigated why oral mucosal wounds heal more rapidly and with reduced scar formation than cutaneous wounds. They obtained biopsies of both oral mucosal and skin wounds and used microarrays to compare transcriptomes to determine the critical differences in the healing response at these two sites. Their results demonstrated dramatically different reactions to injury between skin and mucosal wounds.19 In a study by Greco et al.,20 the gene expression profiles of thermally injured human skin were observed with microarrays. For the analysis, skin samples were collected from 45 burn patients and the transcriptomes were compared with those from 15 control patients. Greco et al. found that the expressions of several hundreds of genes were significantly altered between groups, including many calcium-binding proteins, cytokeratins, and chemokines.20 In one study, Deonarine et al.21 investigated gene expression changes in skin wounds by collecting punch biopsies before and after wounding from basal cell carcinoma patients. They concluded that the initial response to a cutaneous wound induces transcriptional activation of proinflammatory stimuli which may alert the host defense.21 It would be useful to be able to translate all existing and future microarray data to clinical relevance as has already occurred, for example, in cancer biology, using expression signatures as diagnostic and prognostic tools.22 There is still much to do after obtaining relevant microarray-derived gene lists and gene expression associations in terms of functional validations and evaluation of the discoveries for therapeutic application.

Since a comprehensive look at normal human wound healing over time has been lacking, we performed a series of studies to map gene expression changes during the various stages of human superficial cutaneous wound healing.23,24 Standard depth, clean, and consistently healing donor site wounds were used as models for the studies. Biopsies were collected over time to represent different steps in the healing process. The first biopsy was obtained before wounding from the intact skin, and the following biopsies, respectively, from the wound in the acute phase, on the 3rd, 7th, 14th, and 21st postoperative days. In addition, the interest was in determining how the effect of clinical wound therapy would be reflected in terms of gene expression changes. For this purpose, we used negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT), which also served as an example. Our data reveal, as expected, the involvement of thousands of genes during the first 3 weeks of donor site healing. More importantly, they showed which genes act most dominantly and additionally revealed specific groups of genes to be more important than others.23,24

Collecting and handling the samples for microarray and sequencing is very accurate and has many challenges. The surgeon who obtains the samples should be well instructed and samples should be correctly stored to secure the quality of the RNA. Careful and standardized methods for sample collection and handling enable only very small pieces of tissue to be used for the study, which is very critical. The location on the wound where the sample is obtained also affects the results; a sample from the middle of the wound is different from that taken from the wound edges. Thus, the samples should always be obtained from the same area and the number of patients in a study should be big enough, yet balanced between study costs and statistical power. Iatrogenic wounds, such as donor site wounds, make models for human wound-healing studies because they are standardized and heal over time.

From microarrays to sequencing

RNA-seq is a recent prominent methodology for genome-wide transcriptome studies. Although there are many modified RNA-seq methods for measuring various types of RNAs, the standard one is complementary DNA (cDNA) sequencing of long polyadenylated RNA with fragmentation. Counts of the sequenced fragments associated with a known gene correlate with the actual expression levels of the gene; therefore, the RNA-seq is an alternative method to the microarray for the extraction of differentially expressed genes. The sequenced fragments overlapping with the exon junctions also suggest the presence of splicing patterns; thus, the RNA-seq provides unique insights into differential protein expression. Moreover, although the genome and large-scale cDNA projects identified many genes and splicing isoforms, alignments of the sequenced fragments in unannotated regions imply novel exon usages, or possible novel transcripts. Therefore, RNA-seq provides rich information on transcriptomes.

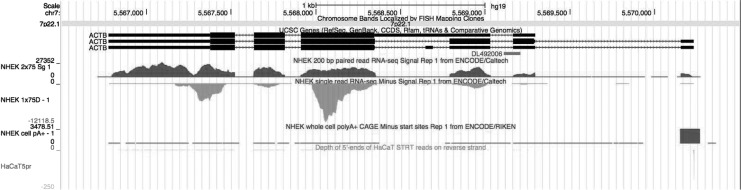

One of the other RNA-seq methods is 5′-end sequencing of messenger RNAs (mRNAs). These methods are better for the identification of transcription starting sites than the standard RNA-seq methods. Figure 1 shows an example of human beta-actin gene (ACTB) loci; the human ACTB has two alternative starting sites, and these two could produce two different proteins. While fragments sequenced by the standard method were distributed to the second or further downstream exons, the 5′-end sequencing methods clearly indicated usage of the upstream promoter in human keratinocytes. Regulatory elements were concentrated around the starting sites; therefore, the 5′-end sequencing RNA-seq could suggest upstream regulators more precisely than the microarray and standard RNA-seq methods.25 In other words, 5′-end sequencing is for upstream-oriented studies, while the standard method is for downstream-oriented studies.

Figure 1.

Comparison of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) methods in human ACTB loci. The track at the top is the known ACTB splicing patterns; there were two alternative starting sites, and the two sites could produce two different proteins. The following tracks are alignment histograms of (i) normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) by nonstrand-specific standard RNA-seq, (ii) NHEK by strand-specific standard RNA-seq, (iii) NHEK by capa analysis gene expression (CAGE), which is a 5′-end sequencing RNA-method, and (iv) HaCaT by STRT, which is the other 5′-end sequencing method. The tracks (i–iii) are by the ENCODE project.32

Skin maintenance and wound healing are complex four-dimensional processes, in which heterogeneous cell types cooperate. RNA-seq requires as low as 10 ng of total RNA, and when used along with the recent optimized methods for quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR),26 and microarray,27 it is expected to redefine the evaluation of the transcriptome at a given timepoint, and approximately a single cell level.28–30 Moreover, combined with minimally manipulated clinical sample collection, the application of these technologies could help reveal unprecedented novel transcriptional variations even in each cell type.31 For these purposes, however, even further optimizations for high-throughput, or multiplex, experiments should be considered.32

An important preprocessing step for reducing technical variations before statistical tests is normalization. Traditional normalization methods require endogenous genes that are expressed stably in the target samples, and the normalization corrects the measured expression levels of the target genes using one of the control genes. However, the expression of control genes, which is assumed to be constant, is restricted to given cell types or conditions.33 Therefore, while small-scale experiments require careful gene selection,34,35 genome-wide measurements use the other properties, which were assumed to be constant in the endogenous genes over samples. For example, quantile normalization (for array,36 for qRT-PCR,37 or for RNA-seq38) assumes that the distribution of the transcriptome remains nearly constant throughout the samples. Rank-invariant set normalization assumes that many genes have the same rank order across samples, although the absolute expression levels may change; the normalization is rescaling of the measurement values to make the rank-invariant genes equivalent.37,39 Moreover, several normalization methods for RNA-seq assume that counting of the total, or some portion of the transcripts is equivalent across the samples.40–42

However, the traditional normalization methods could overestimate the stability of the cellular systems. For example, the RNA/DNA ratio of human keratinocytes changed sixfold, depending on the cell-cycle phase, cell size, or the passages.43 The mRNA content per cell also decreased fourfold by the first duplication of cleavages for human preimplantation developments, as the size of the early embryos did not change after the fertilization.44 Moreover, mouse embryonic fibroblasts have 23 times as much polyadenylated RNAs as mouse embryonic stem cells in each cell.29 In fact, a given cell changes its volume, complexity, and amount of RNA drastically depending on its biological activity and environment. Therefore, many genes throughout the whole genome would be differentially expressed in different cases, and this did not match with assumptions in the traditional normalization methods. Even if we used equivalent amounts of RNAs for measurements, valid interpretation would change whether we extracted the RNAs from an equivalent number or nonequivalent number of cells. One solution is the addition of exogenous control RNAs into the target RNAs just before reverse transcription, and normalization according to the controls.29,45–47

Summary

Future evolution of technologies and processing of samples down to a single cell in size will enable more research to be carried out in the clinical setting on humans. Enormous amounts of data can already be collected from tiny tissue samples, using the newest microarray techniques or RNA-seq for evaluation of gene expression. Given the huge financial impact of the wound-healing market, this will lead to an increase in both research on the basic mechanisms of wound healing and the pathology of compromised healing, as well as clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of various products. Although such development of tools enabling research on human subjects is extremely important and provides long-desired progress in the science of wound healing, there are several caveats to these trials that need to be assessed with careful study design, and motivated meticulous adherence to the trial guidelines by the clinical staff. The fact remains that even if these novel techniques provide massive amounts of data, the data are only as good—or as bad—as the sample. After collection, proper storage and handling, as well as sample processing and analysis, are further major steps that need to be standardized with care. After collection of data, analysis of the data is critical and should be performed correctly.

Take-Home Messages.

• Molecular mechanisms behind human skin wound healing are still not completely clear.

• Existing and emerging RNA- and DNA-based techniques have enabled molecular-level clinical research from a very small amount of tissue.

• Active collaboration between clinicians and researchers will enable elucidation of human wound-healing mechanisms for guiding rational design of patient treatments.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NPWT

negative-pressure wound therapy

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Finnish Government EVO grants and the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

All authors declare no conflicts of interest, and no ghostwriters were involved in the writing of this article.

About the Authors

Kristo Nuutila, PhD, is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Biomedicine. Shintaro Katayama, PhD, is a bioinformatics-specialized postdoctoral researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Jyrki Vuola, MD, PhD, is the head of Helsinki Burn Center and an associate professor of plastic surgery in the University of Helsinki. Esko Kankuri, MD, PhD, is an associate professor of pharmacology in the University of Helsinki and the leader of regenerative skin therapies research group at the Institute of Biomedicine

References

- 1.Percival NJ: Classification of wounds and their management. Surgery 2002; 20:114 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore FA, Sauaia A, Moore EE, Haenel JB, Burch JM, and Lezotte DC: Postinjury multiple organ failure: a bimodal phenomenon. J Trauma 1996; 40:501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, and Longaker MT: Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008; 453:314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin P: Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science 1997; 276:75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afshar M. and Gallo RL: Innate immune defense system of the skin. Vet Dermatol 2013; 24:32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweizer ML. and Herwaldt LA: Surgical site infections and their prevention. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012; 25:378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, and Longaker MT: Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen 2009; 17:763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mustoe TA, O'Shaughnessy K, and Kloeters O: Chronic wound pathogenesis and current treatment strategies: a unifying hypothesis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117:35S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bronaugh RL, Stewart RF, and Congdon ER: Methods for in vitro percutaneous absorption studies. II. Animal models for human skin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1982; 62:481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorsett-Martin WA: Rat models of skin wound healing: a review. Wound Repair Regen 2004; 12:591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan TP, Eaglstein WH, Davis SC, and Mertz P: The pig as a model for human wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2001; 9:66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittié L, Sachs DL, Orringer JS, Voorhees JJ, and Fisher GJ: Eccrine sweat glands are major contributors to reepithelialization of human wounds. Am J Pathol 2013; 182:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottrup F: Controversies in performing a randomized control trial and a systemic review. Wound Repair Regen 2012; 20:447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottrup F, Apelqvist J, and Price P; European Wound Management Association Patient Outcome Group: Outcomes in controlled and comparative studies on non-healing wounds: recommendations to improve the quality of evidence in wound management. J Wound Care 2010; 19:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eskes AM, Brölmann FE, Sumpio BE, Mayer D, Moore Z, Agren MS, Hermans M, Cutting K, Legemate DA, Ubbink DT, and Vermeulen H: Fundamentals of randomized clinical trials in wound care: design and conduct. Wound Repair Regen 2012; 20:449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw TJ. and Martin P: Wound repair at a glance. J Cell Sci 2009; 122:3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schäfer M. and Werner S: Transcriptional control of wound repair. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2007; 23:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smiley AK, Klingenberg JM, Aronow BJ, Boyce ST, Kitzmiller WJ, and Supp DM: Microarray analysis of gene expression in cultured skin substitutes compared with native human skin. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125:1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Arbieva ZH, Guo S, Marucha PT, Mustoe TA, and DiPietro LA: Positional differences in the wound transcriptome of skin and oral mucosa. BMC Genomics 2010; 11:471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greco JA, Pollins AC, Boone BE, Levy SE, and Nanney LB: A microarray analysis of temporal gene expression profiles in thermally injured skin. Burns 2010; 36:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deonarine K, Panelli MC, Stashower ME, Jin P, Smith K, Slade HB, Norwood C, Wang E, Marincola FM, and Stroncek DF: Gene expression profiling of cutaneous wound healing. J Transl Med 2007; 5:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, Schreiber GJ, Peterse JL, Roberts C, Marton MJ, Parrish M, Atsma D, Witteveen A, Glas A, Delahaye L, van der Velde T, Bartelink H, Rodenhuis S, Rutgers ET, Friend SH, and Bernards R: A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuutila K, Siltanen A, Peura M, Bizik J, Kaartinen I, Kuokkanen H, Nieminen T, Harjula A, Aarnio P, Vuola J, and Kankuri E: Human skin transcriptome during superficial cutaneous wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2012; 20:830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuutila K, Siltanen A, Peura M, Harjula A, Nieminen T, Vuola J, Kankuri E, and Aarnio P: Gene expression profiling of negative-pressure-treated skin graft donor site wounds. Burns 2013; 39:687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng C, Alexander R, Min R, Leng J, Yip KY, Rozowsky J, Yan KK, Dong X, Djebali S, Ruan Y, Davis CA, Carninci P, Lassman T, Gingeras TR, Guigó R, Birney E, Weng Z, Snyder M, and Gerstein M: Understanding transcriptional regulation by integrative analysis of transcription factor binding data. Genome Res 2012; 22:1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buganim Y, Faddah DA, Cheng AW, Itskovich E, Markoulaki S, Ganz K, Klemm SL, van Oudenaarden A, and Jaenisch R: Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell 2012; 150:1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan DWM, Jensen KB, Trotter MWB, Connelly JT, Broad S, and Watt FM: Single-cell gene expression profiling reveals functional heterogeneity of undifferentiated human epidermal cells. Development 2013; 140:1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang F, Lao K, and Surani MA: Development and applications of single-cell transcriptome analysis. Nat Methods 2011; 8:S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Islam S, Kjällquist U, Moliner A, Zajac P, Fan J-B, Lönnerberg P, and Linnarsson S: Characterization of the single-cell transcriptional landscape by highly multiplex RNA-seq. Genome Res 2011; 21:1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashimshony T, Wagner F, Sher N, and Yanai I: CEL-Seq: single-cell RNA-seq by multiplexed linear amplification. Cell Rep 2012; 2:666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raj A. and van Oudenaarden A: Nature, nurture, or chance: stochastic gene expression and its consequences. Cell 2008; 135:216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Islam S, Kjällquist U, Moliner A, Zajac P, Fan J-B, Lönnerberg P, and Linnarsson S: Highly multiplexed and strand-specific single-cell RNA 5′ end sequencing. Nat Protoc 2012; 7:813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thellin O, Zorzi W, Lakaye B, De Borman B, Coumans B, Hennen G, Grisar T, Igout A, and Heinen E: Housekeeping genes as internal standards: use and limits. J Biotechnol 1999; 75:291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stürzenbaum SR. and Kille P: Control genes in quantitative molecular biological techniques: the variability of invariance. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 2001; 130:281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minner F. and Poumay Y: Candidate housekeeping genes require evaluation before their selection for studies of human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, and Speed TP: A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 2003; 19:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mar JC, Kimura Y, Schroder K, Irvine KM, Hayashizaki Y, Suzuki H, Hume D, and Quackenbush J: Data-driven normalization strategies for high-throughput quantitative RT-PCR. BMC Bioinformatics 2009; 10:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bullard JH, Purdom E, Hansen KD, and Dudoit S: Evaluation of statistical methods for normalization and differential expression in mRNA-Seq experiments. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng GC, Oh MK, Rohlin L, Liao JC, and Wong WH: Issues in cDNA microarray analysis: quality filtering, channel normalization, models of variations and assessment of gene effects. Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29:2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson MD. and Oshlack A: A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol 2010; 11:R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anders S. and Huber W: Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 2010; 11:R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Witten DM, Johnstone IM, and Tibshirani R: Normalization, testing, and false discovery rate estimation for RNA-sequencing data. Biostatistics 2011; 13:523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Staiano-Coico L, Higgins PJ, Darzynkiewicz Z, Kimmel M, Gottlieb AB, Pagan-Charry I, Madden MR, Finkelstein JL, and Hefton JM: Human keratinocyte culture. Identification and staging of epidermal cell subpopulations. J Clin Invest 1986; 77:396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dobson AT, Raja R, Abeyta MJ, Taylor T, Shen S, Haqq C, and Pera RA: The unique transcriptome through day 3 of human preimplantation development. Hum Mol Genet 2004; 13:1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carter MG, Sharov AA, VanBuren V, Dudekula DB, Carmack CE, Nelson C, and Ko MS: Transcript copy number estimation using a mouse whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray. Genome Biol 2005; 6:R61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lovén J, Orlando DA, Sigova AA, Lin CY, Rahl PB, Burge CB, Levens DL, Lee TI, and Young RA: Revisiting global gene expression analysis. Cell 2012; 151:476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katayama S, Töhönen V, Linnarsson S, and Kere J: SAMstrt: statistical test for differential expression in single-cell transcriptome with spike-in normalization. Bioinformatics 2013; 29:2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]