Abstract

A novel delivery method is described for the rapid determination of taste preferences for sweet taste in humans. This forced-choice paired comparison approach incorporates the non-caloric sweetener sucralose into a set of one-inch square edible strips for the rapid determination of sweet taste preferences. When compared to aqueous sucrose solutions, significantly lower amounts of sucralose were required to identify the preference for sweet taste. The validity of this approach was determined by comparing sweet taste preferences obtained with five different sucralose-containing edible strips to a set of five intensity-matched sucrose solutions. When compared to the solution test, edible strips required approximately the same number of steps to identify the preferred amount of sweet taste stimulus. Both approaches yielded similar distribution patterns for the preferred amount of sweet taste stimulus. In addition, taste intensity values for the preferred amount of sucralose in strips were similar to that of sucrose in solution. The hedonic values for the preferred amount of sucralose were lower than for sucrose, but the taste quality of the preferred sucralose strip was described as sweet. When taste intensity values between sucralose strips and sucralose solutions containing identical amounts of taste stimulus were compared, sucralose strips produced a greater taste intensity and more positive hedonic response. A preference test that uses edible strips for stimulus delivery should be useful for identifying preferences for sweet taste in young children, and in clinical populations. This test should also be useful for identifying sweet taste preferences outside of the lab or clinic. Finally, edible strips should be useful for developing preference tests for other primary taste stimuli and for taste mixtures.

Keywords: gustation, taste test, taste preference, sweet taste, edible taste strip, sucralose

Introduction

Food preferences in humans are determined by sensory responses to the taste, smell, and texture of foods (Drewnowski & Rock 1995; Duffy & Bartoshuk, 2000). Of these sensory responses, taste is considered the major determinant of food choice (Asao et al., 2012). Of the primary taste stimuli, sweet taste generally signals a pleasurable experience (Reed and McDaniel, 2006). Due to this strong hedonic appeal, humans have a strong desire for sweet-tasting foods (Drewnowski et al., 2012), or foods with both sweet and fat taste qualities (Drewnowski, 1993; Drewnowski & Greenwood, 1983). However, this desire for sweet-tasting foods may contribute to metabolic syndrome and obesity (Swithers, 2013), hypertension (Ferder et al., 2010), diabetes (Tepper et al., 1996) and dental caries (Binns, 1981; Roberts and Wright, 2012). Nonetheless, no clear association between an increased preference for sweet taste and obesity in humans has been observed (Mattes and Mela, 1986).

Taste preferences for sweetness show age-related differences (Desor & Beauchamp, 1987), and these preferences may be influenced by genetics, race and ethnicity, or nutrient deficiencies (Drewnowski et al., 2012). Changes in preferences for sweet taste are also associated with drug and alcohol use since nicotine (Grunberg et al., 1985), cannabinoids (Yoshida et al., 2010), opiods (Langleben et al., 2012), cocaine (Janowsky et al., 2003), heroin (Picozzi et al., 1972), alcohol (Bogucka-Bonikowska et al., 2001; Gosnell & Krahn, 1998), and methadone (Nolan and Scagnetti, 2007), can impact preferences for sweet taste (Turner-McGrievy et al., 2013).

The preparation, transport, and storage of sucrose solutions for testing outside of the clinic or lab can be laborious. Impregnated filter papers that contain taste stimuli have been prepared that alleviate many of these problems (Lawless, 1980; Mueller et al., 2003; Landis, 2009), but the filter paper must be expectorated after each measurement, and disposed as hazardous waste. A third method for delivering stimuli is to prepare edible taste strips that rapidly and completely dissolve in the oral cavity (Smutzer et al., 2008). Sucralose was chosen as the sweet taste stimulus because this molecule is perceived as approximately 600 times sweeter than sugar (Friedman, 1998; Binns, 2003) so that lower amounts of stimulus are required for examining sweet taste. At matched intensities, both sucrose and sucralose exhibit similar taste perception profiles (Binns, 2003), and sucralose does not result in an unpleasant aftertaste in most individuals (Wells, 1989; Schiffman & Gatlin, 1993). Finally, the Venus flytrap domain at the N-terminus of both heteromeric subunits of the mammalian sweet taste receptor binds both sucrose and sucralose, which would suggest a similar transduction mechanism for both sweet taste stimuli (Zhang et al., 2010).

The purpose of this study was to develop edible sucralose strips for rapidly identifying sweet taste preferences in humans. Then, the perception of sucralose strips and solutions in the oral cavity was measured in order to identify which delivery method yielded higher taste intensity and hedonic values.

Materials and Methods

All sucrose and sucralose solutions were prepared in water (Deer Park, Stamford, CT.), and warmed to room temperature before use. Edible taste strips were prepared as previously described (Smutzer et al., 2008; Smutzer et al., 2013). Briefly, pullulan (α-1,4-; α-1,6-glucan; NutriScience Innovations, LLC, Trumbull, CT), was combined with the polymer hydroxypropyl-methylcellulose (Dow Chemical Co., Midland, MI) at a weight ratio of 11.5:1. Food coloring was added to aid in visualization of taste strips. Sucrose was obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), and sucralose was obtained from Tate & Lyle (MacIntosh, AL). For taste film preparation, a flat casting surface was washed with 70% ethanol, dried, and wiped clean with a paper towel. The clear polymer solution was then poured onto a non-stick surface (Smutzer et al., 2008). The solution was evenly spread over an enclosed area, and allowed to dry for 12 to18 hours at room temperature. After drying, the clear film was removed, cut into one-inch squares, and stored in the dark at 4°C or −100°C in an airtight sealable bag for no more than one month.

The maximal amount of sucrose that could be incorporated into a one-inch square edible taste strip was ~80 umol (Smutzer et al., 2008). This amount of sucrose produces a sweet taste intensity that is well below that of a 36% sucrose solution (Cowart & Beauchamp, 1990). In addition, sucrose amounts greater than ~50 umol resulted in taste strips that became distorted in shape and possessed diminished tensile strength after their removal from the drying surface. These physical characteristics resulted in taste strips that were unsuitable for a preference test with sucrose as the stimulus.

Test Subjects

A total of 50 subjects participated in this project, and included 27 females and 23 males (see Table I). The mean subject age was 26.5 ±1.8 years of age, and all subjects were healthy by self-report. The subjects were 54% Asians, 36% Caucasians, 8% African-Americans, and 2% Hispanic. In the sucralose and sucrose comparison study, the subset of subjects included 12 males and 18 females (mean age was 26.8 ± 2.7 years).

Table I.

Test Subjects for Sweet Preference Study

| Subject Characteristics | Sucralose Strip and Sucrose Soln. Matching | Sweet Preference Tests | Sucralose Retest | Sucralose Strip Quality Study | Sucralose Strips and Sucralose Soln. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Males | 8 | 12 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Number of Females | 4 | 18 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Mean Age | 36.1 ± 5.3 | 26.8 ± 2.7 | 28.2 ± 6.7 | 26.3 ± 3.3 | 26.3 ± 4.8 |

The same cohort of subjects was used for the two preference tests for sweet taste, and for the sucralose retest.

All subjects refrained from eating for 30 minutes prior to the start of the study, and 49 of 50 subjects were non-smokers. Study subjects were recruited through flyers and by word of mouth. All test subjects were trained in the use of the general Labeled Magnitude Scale (gLMS) (Bartoshuk et al., 2004). For taste strips, subjects were instructed to place the strip on the tongue surface, raise their tongue to the roof of their mouth to dissolve the strip, and wait a minimum of 5 seconds before reporting a response. Subjects were specifically instructed to report a taste intensity response and not a tactile response. Lastly, all subjects rinsed with water after each stimuli presentation. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Temple University, and all study participants were provided written informed consent.

Forced Choice Paired Comparison Preference Test for Sweet Taste

For both preference tests, a series of five stimuli with increasing amounts of stimulus were matched in intensities (identified as A, B, C, D, and E, with A containing the lowest amount of stimulus). For a comparison of the two preference tests, sucralose strip intensity was matched to sucrose solution intensity by trial and error. Initially, sucralose strip A was matched in taste intensity to sucrose solution A, and then the intensity of strip E was approximated to that of sucrose solution E. Finally, the amount of sucralose in samples B, C, D, and E were intensity matched to the corresponding sucrose solutions.

In order to more closely match the intensities of all five stimuli in both preference tests, the sucralose preference test used a geometric progression (common ratio = 2) for varying the amount of taste stimulus rather than a modified geometric progression (Cowart & Beauchamp, 1990), where the highest concentration of liquid sucrose was 1.5 times greater than the penultimate concentration.

For edible strips, test subjects were presented with pairs of strips that differed in amounts of sucralose (182.4, 364.8, 730.9, 1460.5, or 2921.1 nmol of sucralose). For the solution test, subjects were presented with pairs of solutions that differed in amounts of sucrose (0.88, 1.75, 3.51, 7.01, or 10.52 umol of sucrose in 10 ml volumes).

The preference test consisted of two counterbalanced series (see Figure 1). In both series, trial one consisted of the second lowest stimulus amount (sample B) presented with the penultimate stimulus amount (sample D) according to Cowart and Beauchamp (1990). This protocol allowed the subject to compare his or her preferred stimulus amount from trial one with either the next lower (series one) or next higher (series two) amount of taste stimulus in trial two (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example of how preferences for sweet taste were identified. Top row lists the amounts of taste stimuli used for the sucralose strip test (nmol) and sucrose liquid test (mmol). A capital “X” denotes the pair of sweet taste stimuli that were presented in each trial. An underline identifies the first stimulus that was presented in each stimulus pair. Preference amounts for each subject were calculated as the geometric mean of the two counterbalanced series of sweet taste stimuli (Adapted from Mennella et al., 2011).

For series one, the lower amount of stimulus was presented first in each trial. Then, the preferred amount of stimulus in trial one was always paired with the next lower stimulus amount in trial two. This protocol was repeated until the subject chose the same amount when presented with both the next higher and next lower amount in successive trials, or when the subject chose either the highest or the lowest amount in two consecutive trials (sample A or E) (Mennella et al., 2011). Each subject rinsed a single time with room temperature water after the first strip of each trial, and rinsed twice between trials.

A three-minute interval occurred between series one and two. For series two, the stronger (higher) amount of stimulus was presented first in all trials. Then, the preferred amount from trial one was always paired with the next higher amount in trial two. As in series one, this process was repeated until the subject chose the same amount when presented with both the next higher and next lower amount of stimulus in consecutive trials, or when the subject chose either the highest (sample E) or the lowest (sample A) amount in two consecutive trials. The preference amount for each subject was estimated by calculating the geometric mean of the amount of sweet taste stimulus that was chosen in each of the two counterbalanced series:

If a subject chose two different preference amounts in series one and series two, then an intermediate amount of taste stimulus would be identified as the preferred amount for that subject. Once the preferred sucralose strip or sucrose solution was identified in each of the two counterbalanced series, subjects were instructed to report a taste intensity and hedonic value for their preferred amount of sweet taste stimulus. The taste intensity and hedonic value of the preferred amount for each subject was again estimated by calculating the geometric mean of the data from series one and series two. The gLMS was used for all taste intensity measurements (Bartoshuk et al., 2004). Possible responses varied from barely detectable (1.4), weak (6.0), moderate (17.0), strong (34.7), very strong (52.5), and the strongest sensation of any kind (100.0). For hedonics ratings, the degrees of liking–disliking of sucralose and sucrose were rated on a (bipolar) hedonic gLMS scale (0 = neutral; ±6.0 = weakly like/dislike; ±17.0 = moderately like/dislike; ±34.7 = strongly like/dislike; ±52.5 = very strongly like/dislike; ±100.0 = strongest imaginable like/dislike of any kind) according to Duffy & Bartoshuk (2000), with zero representing the neutral response. For taste quality responses, subjects were requested to choose among sweet, sour, salty, bitter, fatty, umami, or no taste.

Finally, the two delivery methods (edible strips and aqueous solutions) were compared. Subjects (n = 12) were presented with five different amounts of sucralose in edible strips plus a control strip, or in aqueous solutions plus a water control. Stimuli were presented in random order, and the mean of two trials was used to identify taste intensity responses and hedonic values for sucralose strips and sucralose solutions. A water rinse followed each stimulus presentation, and a mild salt rinse (25 mM NaCl) followed by a water rinse, were presented after each trial.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and were analyzed using SPSS, version 17.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY). Significance was defined as p < 0.05. Parametric (e.g., ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc tests) and nonparametric tests (e. g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests) were used to test for differences in taste intensity and hedonic values between sucralose and sucrose solutions and strips. For Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficients, all intensity and hedonic data were transformed to common logarithms (log10) before analysis.

Results

Sucralose is a non-caloric artificial sweetener that is approx. 600 times sweeter than sucrose (Friedman, 1998; Binns, 2003). Consequently, lower stimulus amounts are needed when matching sucralose taste intensities to that of sucrose. The heightened sweet taste of sucralose permitted the development of edible strips with physical characteristics that were indistinguishable from control strips, and yielded a taste intensity response that was comparable to 10 ml sucrose solutions.

The perceived intensity of sucralose taste strips was matched to the intensity of the five sucrose solutions previously used in sweet preference tests (Cowart & Beauchamp, 1990). Figure 2 identifies the amounts of sucralose in the five taste strips that closely matched the perceived intensity of 10 ml sucrose solutions (3% (0.88 mmol) to 36% (10.52 mmol) w/v sucrose). After matching taste intensity, taste quality values for the five sucralose strips and five sucrose solutions were obtained in a subset of subjects (n = 12). A comparison of the sucrose solution and sucralose strip data for all five stimulus amounts yielded a Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient (which measures linear dependence between two values) of 0.99.

Figure 2.

Taste intensity responses for sucralose strips and sucrose solutions for five different amounts of sweet taste stimuli. Vertical lines represent standard errors for intensities obtained with edible strips (n = 12). For the horizontal axis, “O” represents the water control, or the edible strip with no sucralose. Filled squares represent sucralose strip data, and filled circles represent sucrose solution data.

All respondents reported a sweet taste quality for the five sucrose solutions. With sucralose taste strips, all respondents described the taste quality as sweet for strips A, B, C, and D. However, three out of 12 subjects described strip E, which contained the maximal amount of taste stimulus as bitter-sweet, or sweet-salty. The remaining nine subjects reported taste strip E as sweet.

Comparing Sweet Taste Preferences Obtained with Sucralose Strips and Sucrose Solutions

The major focus of this study was to compare and validate preferences for sweet taste when sucralose strips were used to deliver taste stimuli. Sucralose was delivered to the oral cavity by edible taste strips, and sucrose was delivered to the oral cavity by 10 ml liquid solutions.

Figure 3 shows individual preferences for sweet taste that was obtained from test subjects (n=30) by both the sucralose strip method and the sucrose solution method. For sucralose, preferences that were within one nmol were combined (one subject out of 30). Figure 3A is the resulting frequency histogram of the preferred amount of sucralose among our subjects, which were grouped into seven different preference amounts. The preferred amount of sucralose ranged from 182 to 2921 nmol of sucralose, a span of 1.2 log units. Also, preferences for sucralose were not evenly distributed. In our study, the most preferred amounts of sucralose were 1461 nmol, followed by 365 nmol.

Figure 3.

Preferences for sweet taste. A. Histogram of sweet taste preferences for sucralose when this stimulus is delivered to the oral cavity by edible taste strips (n = 30). B. Histogram of sweet taste preferences for sucrose when this stimulus is delivered to the oral cavity as a liquid (n = 30). C. Comparison of sucralose and sucrose taste preferences for each subject in this study (n = 30). Preference amounts for each subject were calculated as the geometric mean of the two counterbalanced series of sweet taste stimuli.

Figure 3B is a frequency histogram of the preferred amount of sucrose in our subjects. Ten different sweet preference amounts were obtained from the same 30 test subjects who were previously tested for sucralose preferences. The range of preferences varied from 0.9 to 10.5 mmol of sucrose, a span of 1.1 log units. As with sucralose, preferences were not uniformly divided among the preference amounts found in our study. Rather, the frequency histogram hinted at a bimodal distribution with 16 of 30 subjects choosing either 1.75 or 7.01 mmol as their preferred amounts. On a molar basis, the mean preferred amount of sucralose when delivered by edible strips was approximately one-five thousandth that of sucrose in solution (885.1 nmol for sucralose compared to 4.4 mmol for sucrose).

Overall, sucralose and sucrose preferences yielded clusters of two different amounts of sweet taste stimuli. A low preference amount was favored by one group (365 nmol for sucralose, and 1.75 mmol for sucrose), and a higher amount was favored by a second group (1461 nmol and 7.01 mmol). This higher amount was four-fold greater than the lower amount for both sweet taste stimuli.

Finally, Figure 3C displays preferred amount of sucralose and sucrose for each subject in our study. These results show that the preferred amounts of sucralose correlated fairly well with the preferred amounts of sucrose for each test subject. The non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test supports this conclusion at the .01 level. In addition, the Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient for the data sets on sweet taste preference was 0.61.

Table II presents a summary of both preference tests for sweet taste. In our subjects, the mean preferred amount for sucralose was slightly greater than the amount of sucralose in strip C (731 nmol sucralose strip). For sucrose, the mean preference amount was also slightly greater than the amount of solution C (3.5 mmol in 10 ml). Overall, 43% of subjects reported different preference amounts for the two counterbalanced series with sucralose as stimulus while 23% of subjects differed in their preferences for sucrose in the two series. Seven out of thirty subjects reported either one higher or one lower preference amount for sucralose, while six subjects chose sucralose preferences that differed by two preference amounts. A similar number of steps were required to identify the sweet taste preference with sucralose strips when compared to sucrose solutions, and the number of steps was not significantly different (ρ >= 0.05, two-tailed test).

Table II.

Comparison of Sucralose and Sucrose Sweet Preference Tests

| Sweet Taste Stimulus | Presentation Vehicle | Preference Amount | Identical Preference | Series 1 Lower Preference | Number steps | Ave. Taste Intensity | Ave. Hedonic Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sucralose | Edible Strips | 885.2 nmol | 17 of 30 | 11 of 30 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 20.9 ±1.7 | 10.6 ± 2.7 |

| Sucrose | Liquid | 4.4 mmol | 23 of 30 | 6 of 30 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 19.5 ± 2.0 | 13.8 ± 2.0 |

Finally, a small number of subjects (n = 10) were retested within two weeks of their original test date. These subjects reported a mean preference of 681.1 nmol of sucralose. A mean of 3.5 ± 0.2 steps was required to reach their preferred amount of sucralose (two series), which was similar to that observed in the original sucralose preference test. Five of ten subjects reported an identical preference for the two series of sucralose strips.

Perceived Taste Intensity Values for the Preferred Amount of Sucralose and Sucrose

At the end of the preference test, participants rated the taste intensity of their preferred amount of sweet taste stimulus. The results indicate that sucralose strips and sucrose solutions did not differ in the intensity rating of the preferred amount of sweet taste stimulus in our test subjects (ANOVA, F (4.0, 70.9) = 0.46, P = 0.50).

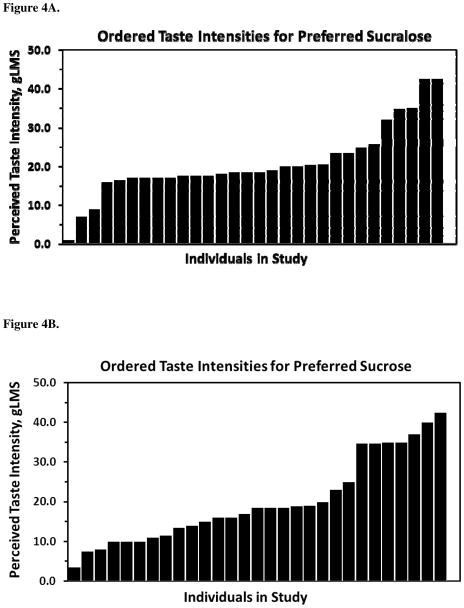

The mean taste intensity for the preferred amount of sucralose in our subjects was slightly above “moderate” on the gLMS (see Table II). Figure 4A shows the ordered taste intensity data from lowest to highest for the preferred amount of sucralose in our subjects. Twenty-nine out of 30 subjects reported taste intensity values that were within three standard deviations of the mean score. The data showed a gradual increase in taste intensity values, and the median difference in the ordered intensity for the preferred amount of sucralose in our subjects was 0.5 gLMS units. Nonetheless, over half the intensity values were clustered between 16 to 20 on the gLMS (moderate intensity) for the preferred amount of sucralose.

Figure 4.

Taste intensity values for the preferred amount of sucralose and sucrose that were chosen by each test subject. Data is ordered from lowest to highest gLMS values. A. Ordered taste intensity values for sucralose. Each vertical column represents the mean taste intensity of the preferred amount of sucralose obtained from series one and series two (n = 30). B. Ordered taste intensity values for sucrose solutions. Each vertical column represents the mean taste intensity of the preferred amount of sucrose obtained from series one and two (n = 30).

For sucrose, the mean taste intensity value for the preferred amount was again just above “moderate” on the gLMS (see Table II). Figure 4B shows the ordered taste intensity data from lowest to highest for the preferred amount of sucrose (n = 30). Twenty-seven of 30 subjects reported intensity values within three standard deviations of the mean for sucrose. When compared to sucralose, taste intensity data showed a nearly identical range on the gLMS. However, ordered taste intensity values for the preferred amount of sucrose showed a greater stepwise increase than did sucralose. For the preferred amount of sucrose, the median difference in intensity was 1.0 gLMS units. In general, individuals who preferred a lower amount of sweet taste stimulus in the preference test reported higher intensity values for sucralose than for sucrose. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test supported this difference at the .01 level.

In contrast, individuals who preferred moderate or higher amounts of sweet taste stimulus reported similar intensity values for both sucralose and sucrose. A comparison of all 30 ordered taste intensities for the preferred amount of sucralose and sucrose yielded a Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient of 0.93.

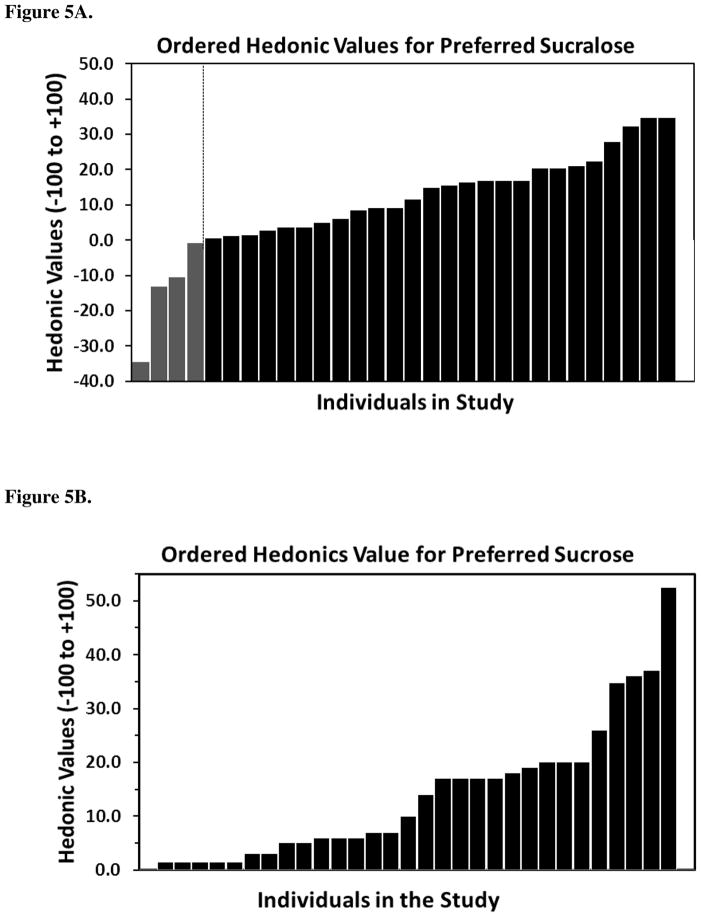

Hedonic Values for Preferred Amounts of Sucralose in Strips and Sucrose in Solution

Each participant also rated the hedonic value of his or her preferred amount of sweet taste stimulus. For our subjects, hedonic values of the preferred amount of stimulus were statistically similar for sucralose strips and sucrose solutions (F (4.0, 138.0) = 0.80, P = 0.38). The mean hedonic value for the preferred amount of sucralose (two series) is shown in Table II. The mean pleasantness value for sucralose ranked between “weakly like” and “moderately like” on the bipolar hedonic scale (Duffy & Bartoshuk, 2000).

Figure 5A is an ordered histogram of the hedonic values for the preferred amount of sucralose for each subject (two series). Hedonic values ranged from −34.5 to +34.7 for sucralose. As shown in Figure 5A, four out of thirty individuals reported a negative value for their preferred amount, with the remaining 26 reporting positive values. In addition, all thirty subjects reported hedonic values that were within three standard deviations of the mean.

Figure 5.

Hedonic values for the preferred sucralose and sucrose amounts that were chosen by each subject. Data are presented as increasing from lowest to highest. A. Histogram of ordered hedonic values for the preferred sucralose strip by each test subject (n = 30). Vertical columns represent the mean hedonic value of the two counterbalanced series of the preference test. Gray bars represent negative hedonic values, and black bars present positive hedonic values. Positive and negative values are also divided by a vertical dotted line. B. Histogram of ordered hedonic values for the preferred sucrose solution reported by each test subject. Vertical columns represent mean hedonic values that were obtained from the two counterbalanced series used to identify the preferred amount of sucrose.

Figure 5B is an ordered histogram of the hedonic values for the preferred sucrose solution (two series). The hedonic values for the preferred amount of sucrose were positive values that ranged between +1.4 to +42.5 in our subjects. As with sucralose, the mean hedonic score for our subjects was between “weakly like” and “moderately like” on the bipolar scale. As shown in Table II, the mean hedonic value for our subject population was higher for sucrose than for sucralose, but all values were within three standard deviations of the mean for both stimuli. However, the range of hedonic values was greater for sucralose strips than for sucrose solutions.

Nineteen subjects reported a higher hedonic score for their preferred amount of sucrose compared to their preferred amount of sucralose, and nine subjects reported higher pleasantness scores for their preferred amount of sucralose compared to their preferred amount of sucrose (two subjects reported identical hedonic scores for both sucrose and sucralose). Finally, the Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient of ordered hedonic values for the two preferred sweet taste stimuli was 0.97.

Taste Quality Measurements for Preferred Amounts of Sucralose and Sucrose

Including the four subjects who reported negative hedonic values for sucralose, all thirty subjects in this phase of our study described their preferred amount of sucralose as sweet. Identical taste quality results were obtained for the preferred amount of sucrose in our study.

Psychophysical Measurements that Compare Sucralose Strips and Sucralose Solutions

The final experiment was completed so that perceived taste intensities and hedonics for all five stimulus amounts used in the preference test (and a control) could be compared by the two delivery methods that were used in this study. For this experiment, identical amounts of sucralose were incorporated into one-inch square edible strips and also dissolved in 10 ml of water. The results from this study are shown in Figure 6. These data indicate that sucralose strips yielded gLMS intensity values that were between 10 and 19 units greater than sucralose solutions for the five stimulus amounts that were used in this study. The insert in Figure 6A shows that the ratios of taste intensity values for sucrose and sucralose increased linearly as the amount of stimulus increased. The Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient for the five intensity values for sucralose strips and solutions was 0.96. Figure 6B shows that mean hedonic values were greater for the five sucralose strips when compared to the five sucralose solutions (n = 12).

Figure 6.

Comparison of two methods for delivering sucralose to the oral cavity. A. The mean intensity of sucralose strips (one-inch squares) compared to sucralose solutions (10 ml volume) (n = 12). Filled squares represent sucralose strips, and filled circles represent sucralose solutions. Water controls and blank strips with no sucralose both yielded mean values of zero. The insert for Figure 6A is a plot of perceived taste intensity that compares both delivery methods for each of the five stimuli used in the preference test. B. The mean hedonic values for sucralose strips and sucralose solutions are shown. Sucralose strip are designated as filled squares, and sucralose solutions are designated as filled circles. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Discussion

Psychophysical studies on sweet taste preferences can use varying concentrations of sucrose solutions that are presented in random order (Kampov-Polevoy et al., 1997), or may employ a forced-choice, paired-comparison tracking technique (Cowart & Beauchamp, 1986, Mennella et al., 2011; Asao et al., 2012, Coldwell et al., 2013). This report describes the development of a forced-choice, paired comparison tracking preference test that uses edible taste strips for delivering sweet taste stimuli. The results of this study demonstrate that edible strips are useful for the rapid estimation of preferences for sweet taste. In addition, these results indicate that edible taste strips yield higher taste intensity values when compared to aqueous solutions (Desai et al., 2011). Finally, the similarity in distribution of taste preference results, taste intensity results, and hedonic values of sucralose strips with sucrose solutions, all indicate that sucralose is an acceptable alternative to sucrose for determining sweet taste preferences in humans.

One important advantage of taste tests is that these studies examine responses to stimuli in the oral cavity. Therefore, post-oral responses are minimized because little or no taste stimulus is swallowed and enters the digestive tract. This advantage is even more pronounced with edible taste strips since lower amounts of taste stimuli are required (Smutzer et al., 2013). Thus, post-ingestive activities of sucralose (Brown et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2012; Pepino et al., 2013), or metabolism of sucralose in the digestive tract (Schiffman, 2012) should be minimal, and should have little or no effect on taste preferences measured in the oral cavity.

On a molar basis, the preferred amount of sucralose was considerably lower than the preferred amount of sucrose. This difference reflects the enhanced sweet taste of sucralose over sucrose (Friedman, 1998) and differences in the two delivery methods (Smutzer et al., 2013, this study). One-inch square polymer-based taste strips are completely dissolved by a relatively small volume of saliva in the oral cavity, which permits this delivery method to present taste stimuli at higher concentrations to a more localized area of the oral cavity (Smutzer et al., 2013). These observations may explain why edible taste strips yield higher perceived taste intensities when compared to aqueous solutions that contain identical amounts of taste stimulus.

Aqueous solutions of sucralose require a longer time interval to produce maximal sweet taste intensities when compared with sucrose solutions (Schiffman et al., 2007). In our study, no significant delay in maximal taste intensity was observed with sucralose strips. Future suprathreshold studies are required to determine whether a measurable delay occurs when edible strips are used to deliver sucralose to the human oral cavity.

The bitterness rating for sucralose in solution is approximately four times greater than sucrose (Schiffman et al., 1995), and may cause a minor aftertaste at high concentrations (Schiffman et al., 1995). In our study, sucralose strips exhibited a mild bitter aftertaste in a small number of subjects at only the highest amount that was used in the preference test (strip E). Sucralose also causes a lingering sweet taste in the oral cavity (Schiffman et al., 2007), and the lingering sweet taste could be minimized in future studies by incorporating small amounts of plant-derived tannic acid compounds or related additives into aqueous solutions or edible films that contain sucralose (Shamil et al., 1992; Shamil, 1996).

Our observations indicate that the highest amount of sucralose used in this study was at or near the upper limit for examining sweet taste preferences with this stimulus. In order to minimize the bitter aftertaste of strip E reported by subjects, future preference tests with sucralose could present subjects with a modified geometric progression of stimuli where the highest amount of stimulus in strip E is less than double the penultimate amount of sucralose in strip D (Cowart & Beauchamp, 1990; Mennella et al., 2011).

Preference results obtained with sucralose strips showed less consistency when compared to the sucrose liquid test for the two counterbalanced series. In addition, the majority of subjects in our study preferred the sweet taste of sucrose to that of sucralose. The difference in consistency between the two preference tests may have been due to the unfamiliarity of sucralose as a sweet taste stimulus, the lower hedonic scores of sucralose when compared to sucrose in some subjects, or differences in the two delivery methods.

In summary, edible taste strips are easy to prepare in large numbers, require minimal storage space, are easily transported outside the lab, can be used in regions of the world where electricity is not available, and can be stored for extended periods of time at room temperature. These edible taste strips completely dissolve in the oral cavity, and should be useful for identifying preferences for other gustatory stimuli that include salt, umami, or fatty acid stimuli (Ebba et al., 2012). This preference test should also prove advantageous for examining taste mixtures, such as sweet-fatty acid mixtures (Crow, 2012). Finally, whole mouth preference tests should be advantageous for separating oral cavity responses from post-oral responses in gastrointestinal tissue that also express taste receptors (Fernstrom, 2012; Dyer et al., 2005).

Conclusions

A protocol that uses edible strips should prove to be a convenient and useful method for examining sweet taste preferences. These strips should allow the rapid examination of sweet taste preferences as a function of normal aging, nutritional status, drug addiction and recovery, the onset of neurological disorders, or obesity-related disorders. In addition, this procedure should be useful for examining preferences outside the lab or clinic. Finally, edible strips should prove effective for determining sweet taste preferences in children and in young adults.

Highlights.

A preference test for sweet taste that uses edible strips is described.

An average of 3.4 steps was required to complete the sucralose preference test.

Preference amounts for sweet taste stimuli showed similar patterns with both methods.

Taste intensity responses for sucralose strips and sucrose solutions were similar.

Sucralose strips produced greater taste intensities than did sucralose solutions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an ARRA supplement to grant 2R44 DC007291 from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. The authors thank Tate and Lyle for providing sucralose for this study, and Dow Chemical Company for the hydroxypropyl-methylcellulose. The authors acknowledge support from the Undergraduate Research Fund at Temple University. Finally, the authors thank Jennifer Orlet Fisher, Susan Coldwell, Joseph Tran, and Julie Mennella for valuable discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asao K, Luo W, Herman WH. Reproducibility of the measurement of sweet taste preferences. Appetite. 2012;59:927–932. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Green BG, Hoffman HJ, Ko CW, Lucchina LA, Marks LE, Snyder DJ, Weiffenbach JM. Valid across-group comparisons with labeled scales: the gLMS versus magnitude matching. Physiology & Behavior. 2004;82:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binns NM. Caries and carbohydrates - a problem for dentists and nutritionists. Dental Health (London) 1981;20:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binns NM. Sucralose – all sweetness and light. Nutrition Bulletin. 2003;28:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bogucka-Bonikowska A, Scinska A, Koros E, Polanowska E, Habrat B, Woronowicz B, Kukwa A, Kostowski W, Bienkowski P. Taste responses in alcohol-dependent men. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;36:516–519. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RJ, Walter M, Rother KI. Ingestion of diet soda before a glucose load augments glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2184–2186. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RJ, Walter M, Rother KI. Effects of diet soda on gut hormones in youths with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:959–964. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell SE, Mennella JA, Duffy VB, Pelchat M, Griffith JW, Smutzer G, et al. Gustation assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80 (Supplement 3):S20–S24. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart BJ, Beauchamp GK. The importance of sensory context in young children’s acceptance of salty tastes. Child Development. 1986;57:1034–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart BJ, Beauchamp GK. Early development of taste perception. In: McBride RL, MacFie HJH, editors. Psychological basis of sensory evaluation. London: Elsevier Applied Science; 1990. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Crow JM. Obesity: insensitive issue. Nature. 2012;486:S12–S13. doi: 10.1038/486S12a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai H, Smutzer G, Coldwell SE, Griffith JW. Validation of edible taste strips for identifying PROP taste recognition thresholds. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1177–1183. doi: 10.1002/lary.21757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desor JA, Beauchamp GK. Longitudinal changes in sweet preferences in humans. Physiology & Behavior. 1987;39:639–641. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Greenwood MR. Cream and sugar: human preferences for high-fat foods. Physiology & Behavior. 1983;30:629–633. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A. Individual differences in sensory preferences for fat in model sweet dairy products. Acta Psychologica (Amsterdam) 1993;84:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(93)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Rock CL. The influence of genetic taste markers on food acceptance. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1995;62:506–511. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.3.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Mennella JA, Johnson SL, Bellisle F. Sweetness and food preference. Journal of Nutrition. 2012;142:1142S–1148S. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.149575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Bartoshuk LM. Food acceptance and genetic variation in taste. Journal of the American Dietic Association. 2000;100:647–655. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer J, Salmon KS, Zibrik L, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Expression of sweet taste receptors of the T1R family in the intestinal tract and enteroendocrine cells. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2005;33:302–305. doi: 10.1042/BST0330302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebba S, Abarintos RA, Kim DG, Tiyouh M, Stull JC, Movalia A, Smutzer G. The examination of fatty acid taste with edible strips. Physiology & Behavior. 2012;106:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferder L, Ferder MD, Inserra F. The role of high-fructose corn syrup in metabolic syndrome and hypertension. Current Hypertension Reports. 2010;12:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrom JD, Munger SD, Sclafani A, de Araujo IE, Roberts A, Molinary S. Mechanisms for Sweetness. Journal of Nutrition. 2012;142:1134S–1141S. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.149567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MA. Federal Register. 1998. Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption; Sucralose. 21 CFR Part 172, Docket No. 87F-0086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell BA, Krahn DD. Taste and diet preferences as predictors of drug self-administration. NIDA Research Monograph. 1998;169:154–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg NE, Bowen DJ, Maycock VA, Nespor SM. The importance of sweet taste and caloric content in the effects of nicotine on specific food consumption. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1985;87:198–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00431807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowsky DS, Pucilowski O, Buyinza M. Preference for higher sucrose concentrations in cocaine abusing-dependent patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;37:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampov-Polevoy A, Garbutt JC, Janowsky D. Evidence of preference for a high-concentration sucrose solution in alcoholic men. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:269–270. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis BN, Welge-Luessen A, Brämerson A, Bende M, Mueller CA, Nordin S, Hummel T. “Taste Strips” - a rapid, lateralized, gustatory bedside identification test based on impregnated filter papers. Journal of Neurology. 2009;256:242–248. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0088-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langleben DD, Busch EL, O’Brien CP, Elman I. Depot naltrexone decreases rewarding properties of sugar in patients with opioid dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2012;220:559–564. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless H. A comparison of different methods used to assess sensitivity to the taste of phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) Chemical Senses. 1980;5:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mattes RD, Mela DJ. Relationships between and among selected measures of sweet-taste preference and dietary intake. Chemical Senses. 1986;11:523–539. [Google Scholar]

- Mennella JA, Lukasewycz LD, Griffith JW, Beauchamp GK. Evaluation of the Monell forced-choice, paired-comparison tracking procedure for determining sweet taste preferences across the lifespan. Chemical Senses. 2011;36:345–355. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller C, Kallert S, Renner B, Stiassny K, Temmel AF, Hummel T, Kobal G. Quantitative assessment of gustatory function in a clinical context using impregnated “taste strips”. Rhinology. 2003;41:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan LJ, Scagnelli LM. Preference for sweet foods and higher body mass index in patients being treated in long-term methadone maintenance. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:1555–1566. doi: 10.1080/10826080701517727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepino MY, Tiemann CD, Patterson BW, Wice BM, Klein S. Sucralose affects glycemic and hormonal responses to an oral glucose load. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2530–2535. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picozzi A, Dworkin SF, Leeds JG, Nash J. Dental and associated attitudinal aspects of heroin addiction: a pilot study. Journal of Dental Research. 1972;51:869. doi: 10.1177/00220345720510032901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DR, McDaniel AH. The human sweet tooth. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6 (Suppl 1):S17–S29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MW, Wright JT. Nonnutritive, low caloric substitutes for food sugars: clinical implications for addressing the incidence of dental caries and overweight/obesity. International Journal of Dentistry. 2012:8. doi: 10.1155/2012/625701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman SS, Gatlin CA. Sweeteners: state of knowledge review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 1993;17:313–345. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman SS, Booth BJ, Losee ML, Pecore SD, Warwick ZS. Bitterness of sweeteners as a function of concentration. Brain Research Bulletin. 1995;36:505–513. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00225-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman SS, Sattely-Miller EA, Bishay IE. Time to maximum sweetness intensity of binary and ternary blends of sweeteners. Food Quality and Preference. 2007;18:405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman SS. Rationale for further medical and health research on high-potency sweeteners. Chemical Senses. 2012;37:671–679. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjs053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamil SH, Birch GG. Physico-chemical and psychophysical studies of 4,1′,6′-trichloro-4,1′6′-trideoxy-galactosucrose (sucralose) Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und Technologie. 1992;25:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Shamil SH. U.S. Patent No 5902628. A Beverage with reduction of lingering sweet aftertaste of sucralose. 1996

- Smutzer G, Lam S, Hastings L, Desai H, Abarintos RA, Sobel M, et al. A test for measuring gustatory function. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1411–1416. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817709a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smutzer G, Desai H, Coldwell SE, Griffith JW. Validation of edible taste strips for assessing PROP taste perception. Chemical Senses. 2013;38:529–539. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swithers SE. Artificial sweeteners produce the counterintuitive effect of inducing metabolic derangements. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;24:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper BJ, Hartfiel LM, Schneider SH. Sweet taste and diet in type II diabetes. Physiology & Behavior. 1996;60:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner-McGrievy G, Tate DF, Moore D, Popkin B. Taking the bitter with the sweet: relationship of supertasting and sweet preference with metabolic syndrome and dietary intake. Journal of Food Science. 2013;78:S336–S342. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells AG. The use of intense sweeteners in soft drinks. In: Grenby TH, editor. Progress in Sweeteners. London: Elsevier Applied Science; 1989. pp. 169–214. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R, Ohkuri T, Jyotaki M, Yasuo T, Horio N, Yasumatsu K, Sanematsu K, Shigemura N, Yamamoto T, Margolskee RF, Ninomiya Y. Endocannabinoids selectively enhance sweet taste. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2010;107:935–939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912048107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Klebansky B, Fine RM, Liu H, Xu H, Servant G, Zoller M, Tachdjian C, Li X. Molecular mechanism of the sweet taste enhancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2010;107:4752–4757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911660107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]