Abstract

The aim of this study was to survey the bacterial diversity of Amblyomma maculatum Koch, 1844, and characterize its infection with Rickettsia parkeri. Pyrosequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA was used to determine the total bacterial population in A. maculatum. Pyrosequencing analysis identified Rickettsia in A. maculatum midguts, salivary glands, and saliva, which indicates successful trafficking in the arthropod vector. The identity of Rickettsia spp. was determined based on sequencing the rickettsial outer membrane protein A (rompA) gene. The sequence homology search revealed the presence of R. parkeri, Rickettsia amblyommii, and Rickettsia endosymbiont of A. maculatum in midgut tissues, whereas the only rickettsia detected in salivary glands was R. parkeri, suggesting it is unique in its ability to migrate from midgut to salivary glands, and colonize this tissue before dissemination to the host. Owing to its importance as an emerging infectious disease, the R. parkeri pathogen burden was quantified by a rompB-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay and the diagnostic effectiveness of using R. parkeri polyclonal antibodies in tick tissues was tested. Together, these data indicate that field-collected A. maculatum had a R. parkeri infection rate of 12–32%. This study provides an insight into the A. maculatum microbiome and confirms the presence of R. parkeri, which will serve as the basis for future tick and microbiome interaction studies.

Keywords: Amblyomma maculatum, Rickettsia parkeri, microbiome

Ticks transmit a variety of pathogens and are second only to mosquitoes in human and veterinary health importance (Sonenshine 1991). Amblyomma maculatum Koch, 1844, has emerged as an important arthropod of public health significance because of its competence as a vector for Rickettsia parkeri and experimental vector of Ehrlichia ruminantium. R. parkeri is the causative agent of human rickettsiosis (Paddock et al. 2010), and E. ruminantium is the etiological agent of a fatal cattle disease in South America and Africa (Uilenberg 1982). A. maculatum is distributed along the Atlantic and Gulf Coast region of the United States and is also present in several Central and South American countries (Teel et al. 2010). Bird migration and livestock transportation are two important factors affecting the distribution of A. maculatum (Hasle et al. 2009) and represent a serious threat in importing tick-borne diseases into the United States (Uilenberg 1982).

Ticks also harbor various nonpathogenic microbial organisms; however, knowledge of these microbial communities associated with ticks remains largely unknown because of limitations in culture-based techniques. Bacterial ribosomal-based sequence analysis (“metagenomics”) has revolutionized the exploration of microbial communities in complex environments (Dowd et al. 2008a,b). This method has been successfully used to characterize the metagenome of Ixodes ricinus L., Rhipicephalus microplus (Canestrini, 1888), and Amblyomma americanum (L.) (Andreotti et al. 2011, Carpi et al. 2011, Menchaca et al. 2013), and has revealed a rich bacterial diversity in ticks, but with limited understanding of the functional significance of the associated bacterial communities. The bacterial genera Stenotrophomonas, Pseudomonas, Rhodococcus, and Propriobacterium have consistently been identified in tick tissues. Ticks are also frequently associated with various pathogenic bacteria of the Borrelia, Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, and Anaplasma genera, various bacterial endosymbionts, or both, which can have commensal, mutualistic, or parasitic relationships with ticks (Noda et al. 1997, Sacchi et al. 2004, Scoles 2004).

Tick-borne rickettsial diseases are caused by two groups of intracellular bacterial species belonging to 1) the spotted fever group of the genus Rickettsia (spotted fever group Rickettsia (SFGR); Raoult and Roux 1997), and 2) species from the Anaplasma and Ehrlichia genera (Dumler et al. 2001). Rickettsiae are obligatory intracellular gram-negative α-proteobacteria that are disseminated by arthropod vectors and affect an estimated one billion people worldwide (Parola et al. 2005, Walker and Ismail 2008). Ticks are the important reservoir of the SFGR (Raoult and Roux 1997).

This metagenomics study begins to investigate the functional role of microbial communities in organismal biology. The microbial community plays important roles in pathogen transmission, vector competence (Burgdorfer et al. 1973, Clay et al. 2008, Vilcins et al. 2009), and tick reproductive fitness (Zhong et al. 2007), and likely has other undiscovered roles in vector ecological and physiological adaptation. In this study, we examined the microbiome associated with blood-fed A. maculatum and further screened for SFGR agents. This is the first report cataloging the microbial diversity associated with A. maculatum-isolated tissues during pathogen development. The identification of the A. maculatum microbiome and further detection of R. parkeri in tick tissues provides the basis for future tick–pathogen interaction studies.

Materials and Methods

Tick Rearing

Adult Gulf-Coast ticks were obtained from three different sources. Wild-caught A. maculatum were collected from the Sandhill National Wildlife Refuge (Gautier, MS) using the drag-cloth method as described previously (Falco and Fish 1988). These ticks were collected in late summer and early fall of 2011 and 2012. Questing adult ticks were collected and identified based on morphological characteristics (Keirans and Litwak 1989). Rickettsial identification within the wild-caught ticks is described below. A. maculatum ticks that contain Rickettsia endosymbionts (lab colony) were purchased from the tick rearing facility at Oklahoma State University. Rickettsia-free A. maculatum ticks were purchased from the tick rearing facility at Texas A&M (TAMU) and were used in the immunological study of R. parkeri. All adult male and female ticks were partially blood fed on a New Zealand rabbit or sheep according to the approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol #10042001.

Tick Tissue Isolation

Blood-feeding ticks (n = 134) were removed 8 d postinfestation, weighed, and dissected to isolate midguts (MG) and salivary gland (SG) tissues from each female tick (Karim et al. 2002). The carcasses (whole tick without the midgut and salivary gland tissues) were used to determine the infection rate (2012 collection). Genomic DNA was extracted from a small piece of isolated midgut and one salivary gland to test for SFGR infection. Tick saliva was collected after injecting saliva extraction solution (Ribeiro et al. 1992). Briefly, dopamine and theophylline (1 mM each in 20 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid-buffered saline with 3% dimethyl sulfoxide, pH 7.0) were injected into the dorsum hindquarter as a stimulant for salivation (Needham and Sauer 1979). The collected saliva was used immediately after collection or stored at −80°C.

DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from tick tissues using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. From the 2011 field collection, genomic DNA was collected from midgut tissues, salivary glands, and male ticks. From the 2012 field collection tick carcasses were also used for the genomic DNA extraction following the same protocol. The extracted DNA samples were stored at −20°C until further use.

454-Pyrosequencing

DNA from field collected and laboratory colony-raised tick tissues was used for bacterial tag-encoded titanium amplicon pyrosequencing (bTETAP; Dowd et al. 2008a,b). The output used for analysis had an average read length of ≈450 bp, with sequencing extending across V1 and into the V3 ribosomal region (MRDNA, Shallowater, TX). This procedure used the forward primer 27F (5′-GAGTTTGATCNTGGCTCAG-3′) and the reverse primer 519R (5′-GTNTTACNGCGGCKGCTG-3′) in relation to E. coli 16S. Amplicon sequencing was performed as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) for titanium sequencing on the FLX-titanium platform.

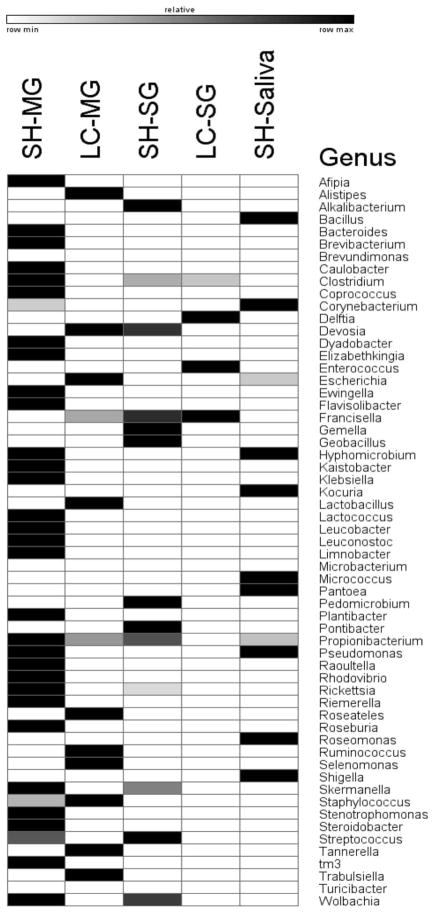

Microbial 16S rDNA sequences were curated to obtain Q25 sequence data, which were processed using a proprietary analysis pipeline (MRDNA), which trimmed sequencing reads to remove barcodes, primers, and short sequences <200 bp. Furthermore, the sequences with ambiguous base calls and homopolymer runs exceeding 6 bp were deleted. The sequences were than denoised, and chimeras were removed before operational taxonomic units (OTUs) clustering was performed using USEARCH (Drive5, WA). OTUs were defined after removal of singleton sequences, clustering at 97% similarity (Dowd et al. 2008a,b, 2011; Edgar 2010; Capone et al. 2011; Eren et al. 2011; Swanson et al. 2011). The taxonomic level of classification of OTUs was performed using BLASTn against a curated GreenGenes database (DeSantis et al. 2006) and compiled into each taxonomic level into both “counts” and “percentage” files. GENE-E software was used to visualize the percentage of bacterial genera in tick tissues and saliva, relative to each sample (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The relative abundance of bacterial genera in A. maculatum tissues. The field-collected ticks (SH) and lab colony (LC) ticks: midgut (MG), salivary glands (SG), and saliva.

SFGR Detection

The presence of SFGR was detected by using outer membrane protein A (ompA) gene-specific primers in a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction (Blair et al. 2004). The primers RR 190–70 and RR 190–701 (Table 1) were used for the primary reaction, and 190-FN1 and 190-RN1 (Table 1) for the nested PCR reaction. In the primary reaction, ≈150 ng of DNA template was added to 2× PCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI) and the appropriate primers (400 nM). In the nested reaction, the same mixture was used except with the nested primers and 2.5 μl from the primary reaction. SFGR PCR was performed in a MyCycler Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA) as follows: one cycle at 95°C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 95° for 20 s, 46°C for 30 s, and 63°C for 60 s, and one cycle at 72°C for 7 min. For each reaction, two negative controls (no-template and no-primer) and one positive control (50 ng of a known SFGR) were included. The amplicons were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and observed using a ultraviolet transilluminator. The PCR products were purified (Qiagen) and sequenced at Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). Partial sequences obtained were analyzed by BLASTn from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) for homology searches. All PCR reactions were set up in a PCR hood using sterile technique. The PCR amplicon sequences obtained from this study were assigned GenBank accession numbers: JQ914757-81 and JX134636-41.

Table 1.

Primers and probe used in this study

| Gene | Sequences | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ompA (primary) | (F) 5′-ATGGCGAATATTTCTCCAAAA-3′ (R) 5′-GTTCCGTTAATGGCAGCATCT-3′ |

590 | (Blair et al. 2004) |

| ompA (nested) | (F) 5′-AAGCAATACAACAAGGTC-3′ (R) 5′-TGACAGTTATTATACCTC-3′ |

540 | |

| ompB (qPCR) | (F) 5′-CAAATGTTGCAGTTCCTCTAAATG-3′ (R) 5′-AAAACAAACCGTTAAAACTACCG-3′ (Probe) 5′-6-FAM-CGCGAAATTAATACCCTTATGAGCAGCAGTCGCG-BHQ1-3′ |

96 | (Jiang et al. 2012) |

Quantification of R. parkeri

The presence of R. parkeri in tick tissues detected from the outer membrane protein A (rompA) gene study were further validated and quantified using the rickettsial outer membrane protein B (rompB)-based qPCR assay (Jiang et al. 2012). The R. parkeri ompB gene from positive ompA assay samples and a R. parkeri-positive sample were first amplified by PCR using primers Rpa129 F and Rpa224R (Table 1). The amplified rompB PCR product was visualized on an agarose gel and purified. The purified PCR product was serially diluted 10-fold (2 × 108 to 2 × 101) and used for standard curve preparation. The qPCR reaction consists of 2× Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI), 100 ng DNA template, 0.7 μM of each primer (Rpa129F and Rpa224R), 0.4 μM probe (Rpa188p; Table 1), and 8 mM MgSO4. The qPCR reactions were performed in a Thermal Cycler (CFX96 Real time detection system, Bio-Rad Laboratories) subjected to one cycle each of 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 2 min, and 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s. A no-template control and a positive control were included in each qPCR run. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and the obtained threshold cycle (Ct) values were used to calculate the copy number based on the standard equation.

Preparation of R. parkeri Tissue Culture

R. parkeri seed stock (1 ml) was diluted (1:10) in sterile brain heart infusion buffer or Snyder’s 1 buffer and used for the inoculation of two T-162 cm2 flasks containing Vero cells (−2–3 × 106 cells/ml). Twenty milliliters of the old media from each flask was discarded. The diluted seed stock was inoculated into each flask, rocked at RT for 1 h, replenished with 20 ml of fresh Eagle’s minimum essential medium containing 2.5% fetal bovine serum, and then placed back into the incubator. Culture flasks were incubated at 35°C and 5% CO2 until 20–30% of the infected cells had sloughed off (6–7 d). Sterile 5-mm glass beads were used to disrupt cell adhesion. The pooled cell suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in Snyder’s 1 buffer (0.22 M sucrose, 3.6 mM KH2PO4, 8.6 mM Na2HPO4, and 4.9 mM glutamic acid) at a ratio of one cell pellet to 4 ml of Snyder’s 1 buffer. R. parkeri stock was aliquoted in 1 ml volumes, placed in cryogenic vials and stored at −80°C.

Preparation of Whole Cell Antigen for Mouse Antibody Generation

R. parkeri was propagated in several T-162 cm2 flasks of Vero cells grown in Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 2.5% fetal bovine serum in 5% CO2 at 35°C. Heavily infected cells were harvested at 6–7 d postinfection, using sterile 5-mm-diameter glass beads. Cells were spun at 7,600 × g for 40 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of K36 buffer (0.1 M KCl, 0.015 M NaCl, 0.05 M KH2PO4, and pH 7.0) and homogenized with a glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and spun at 7,600 × g for another 40 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended with K36 buffer. The suspension was then used for mouse immunization. The sera from rickettsimic mouse blood were used for the detection of R. parkeri in tick tissues.

Immunodetection of R. parkeri in Tick Tissues

R. parkeri-infected female A. maculatum midgut and salivary glands tissues were suspended in 100 μl of extraction buffer (0.15 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.3 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, and Protease inhibitor cocktail) followed by sonication (3 by 5 s). The sonicated samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were removed, and the protein concentration was estimated using the Bradford assay (Bradford 1976). R. parkeri-infected Vero cells were subjected to the same procedure. The extracted supernatants were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 4–20% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane in a Transblot Cell (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturers’ instructions. A duplicate gel was stained with GelCode Blue (Pierce, IL) for visualization. R. parkeri-infected Vero cell supernatant was used as a positive control. A. maculatum obtained from the Texas A&M tick rearing facility have previously been shown to be Rickettsia free (Moraru et al. 2013) and, therefore, these samples were used as a negative control. Nonspecific binding was reduced by incubating the blot with 5% skim milk and mouse pre-immune sera (1:10,000). The nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with mouse R. parkeri polyclonal antibody (1:500 dilution). The antigen–antibody complex was visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (KPL) at a dilution of 1:10,000 and detected with SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) using Bio-Rad ChemiDox XRS. The same blot was reprobed with the monoclonal anti-β-Actin-peroxidase (1:25,000; Sigma).

Results

Microbiome of A. maculatum

From field collected A. maculatum tissues, we obtained 27,691 sequence reads for analysis after trimming and removing all low-quality sequences. In total, 12,330 sequence reads obtained from midgut tissues, 13,009 sequences reads from salivary glands, and 2,352 sequence reads from saliva were searched against the GreenGenes databases. Similarly, we obtained, in total, 13,927 sequence reads from lab colony A. maculatum midgut and salivary gland tissues together. This provided a reference for comparing field and lab colony A. maculatum tissues.

In field collected A. maculatum, the bacterial phyla Proteobacteria (83.39% MG, 95.90% SG, and 92.18% saliva), Actinobacteria (3.92% MG, 2.28% SG, and 5.23% saliva), and Firmicutes (11.0% MG, 1.73% SG, and 2.59% saliva) were found in all tick tissues, and these phyla account for >95% of the bacterial communities in all tested tick tissues. Minor bacterial phyla detected in tick midguts include Bacteroidetes (1.42%), Spirochaetes (0.17%), Cyanobacteria (0.07%), and Fusobacteria (0.02%) whereas salivary gland tissues had only a few reads from Bacteroidetes (0.05%), Spirochaetes (0.01%), and Chloroflexi (0.03%). In lab colony A. maculatum, we observed bacterial reads representing Proteobacteria (64.90% MG; 99.49% SG), Firmicutes (20.53% MG, 0.51% SG), Bacteroidetes (13.25% MG, 0% SG), and Actinobacteria (1.32% MG, 0% SG) phyla.

Francisellaceae (0.22% MG, 82.34% SG), Enterobacteriaceae (30.58% MG, 0.1% SG, and 90.82% saliva), and Rickettsiaceae (51.47% MG, 11.40% SG, and 0.21% saliva) were abundant bacterial families detected in field-collected A. maculatum tick tissues and saliva, accounting for >80% of bacterial species detected in tick tissues. The majority of endosymbionts detected in this study belong to the Francisellaceae family. A. maculatum from the lab colony had abundant reads from Francisellaceae (34.44% MG, 99.27% SG), while most other bacterial families in midgut tissues were Enterobacteriaceae (27.81%), Veillonellaceae (9.93%), Ruminococcaceae (5.30%), Porphyromonadaceae (4.64%), Lactobaccillaceae (3.97%), Staphylococcaceae (1.32%), Propionibacteriaceae (1.32%), and Comamonadaceae (1.98%).

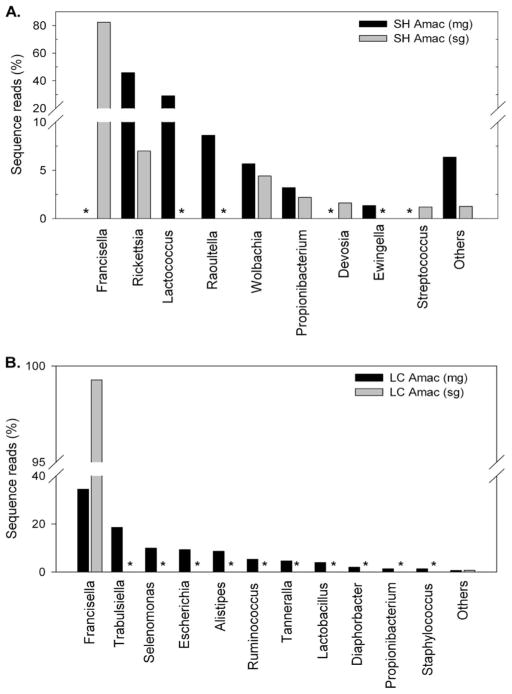

In wild-caught ticks, pyrosequencing revealed 54 different bacterial genera from midgut tissues, 23 different bacterial genera from the salivary gland tissues, and 16 bacterial genera from saliva (Figs. 1 and 2). We observed six bacterial genera in all tick tissues studied: Francisella, Propionibacterium, Rickettsia, Pseudomonas, Corynebacterium, and Escherichia. In addition, the Enterobacterial genera (Raoultella, Ewingella, Escherichia, and Klebsiella) account for ≈30% of the total microbial diversity in tick midgut tissues (Fig. 1). Reads from Rickettsia account for 46% of the total reads from midgut tissues but only 7% from salivary glands, confirming differential pathogen levels within tissues of blood-feeding wild caught A. maculatum.

Fig. 2.

Microbiome of the partially blood-fed A. maculatum tissues. The bacterial diversity in the tissues from field-collected (A) and lab-based (B) female A. maculatum tissues based on 454-pyrosequencing approach. The asterisk sign (*) denotes no or <1% reads for that genera. Values below 1% were grouped as “Others.”

Not surprisingly, the bacterial diversity is different in tick midguts and salivary glands (Fig. 2), which could be because of bacterial tissue specificity. The lab-maintained A. maculatum revealed Francisella, Escherichia, Alistipes, Ruminococcus, Selenomonas, Staphylococcus, Tannerella, Trabulsiella, Lactobacillus, Propionibacterium, and Diaphorbacter (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, Francisella endosymbionts were detected in the salivary glands of lab-maintained A. maculatum. F. endosymbionts have previously been identified in hard and soft ticks from different continents, but because of difficulty in culture-based techniques, little information is known about these endosymbionts (Ivanov et al 2011).

We determined the microbial diversity in field-collected tick saliva to evaluate potential microbial secretion. The saliva samples revealed sequences from Shigella, Bacillus, Escherichia, and Micrococcus, with most reads identified as originating from Shigella with a few from Rickettsia (Fig. 1). It is important to note that some of the detected bacteria could have resulted from environmental contamination, as many of these bacteria are commonly found in environmental samples. However, because Rickettsiae are obligate intracellular organisms, they were likely secreted from tick salivary glands. The saliva from laboratory-based ticks was not tested in this study.

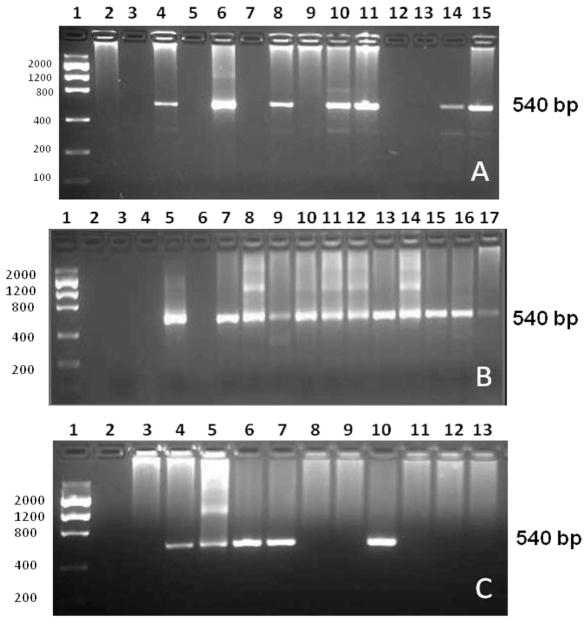

Screening of SFGR in A. maculatum

The prevalence of SFGR infection in the collected ticks was confirmed using ompA gene-specific primers in nested PCR (Fig. 3). The PCR amplicon was sequenced, and the nucleotide homology was assessed by searching the nonredundant nucleotide collection at GenBank. Of the 11 male ticks examined, 54% (6 out of 11) were found to be SFGR positive with nearest homology (99–100%) to R. parkeri, Rickettsia amblyommii, or R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum (Table 2). Next, we examined SFGR infection in partially blood-fed female midguts, salivary glands, and saliva. Eighty percent of tick midguts (20 out of 25) contained SFGR with sequence homology to R. parkeri, R. amblyommii, or R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum. Interestingly, of the eight salivary glands tested for the presence of SFGR, 50% (4 out of 8) showed sequence homology with R. parkeri (Table 2). Although we identified rickettsial reads in tick saliva from pyrosequencing, no SFGR were detected from rompA-nested PCR (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Molecular detection of SFGR in field-collected A. maculatum. Tick tissues were tested for the presence of SFGR using the ompA-nested PCR assay. (A) 1: DNA ladder; 2: no-template control; 3: no-primer control; 4: positive control; lanes 5–15: male tick DNA. (B) Lane 1: DNA ladder; 2, 4, and 6: Blank; 3: no-template control; 5: positive control; lanes 7–17: female midgut DNA. (C) 1: DNA ladder; 2: no-template control; 3: no-primer control; 4: positive control; lanes 5–13: female salivary gland DNA.

Table 2.

SFGR identification in A. maculatum tissues

| A. maculatum | Sample ID | SFGR species | Nucleotide identity (%) | GenBank | qPCR detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female midgut tissues | SH_Mg1 | R. parkeri | 100 | JQ914757 | — |

| SH_Mg2 | R. parkeri | 96 | JQ914758 | — | |

| SH_Mg3 | R. parkeri | 92 | JQ914759 | — | |

| SH_Mg4 | R. parkeri | 98 | JQ914760 | — | |

| SH_Mg5 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 99 | JQ914761 | — | |

| SH_Mg7 | R. amblyommii | 99 | JQ914762 | — | |

| SH_B1 | R. parkeri | 100 | JQ914763 | — | |

| SH_B2 | R. parkeri | 100 | JX134636 | 4,000 ± 1,106 | |

| SH_B3 | R. parkeri | 100 | JX134637 | 6 ± 2 | |

| SH_B4 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 100 | JX134638 | — | |

| SH_B5 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 98 | JX134639 | — | |

| SH_B6 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 98 | JX134640 | — | |

| SH_B7 | R. parkeri | 100 | JQ914764 | — | |

| SH_B8 | R. parkeri | 99 | JQ914765 | 755 ± 88 | |

| SH_B9 | R. parkeri | 99 | JQ914766 | — | |

| SH_B10 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 100 | JQ914767 | — | |

| SH_D1 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 99 | JQ914768 | — | |

| SH_D2 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 100 | JQ914769 | — | |

| SH_D4 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 100 | JQ914770 | — | |

| SH_D5 | R. parkeri | 94 | JQ914771 | — | |

| Female salivary gland tissues | SH_SG1 | R. parkeri | 100 | JQ914772 | 1,794 ± 177 |

| SH_SG2 | R. parkeri | 100 | JQ914773 | — | |

| SH_SG3 | R. parkeri | 100 | JQ914774 | — | |

| SH_SG6 | R. parkeri | 100 | JQ914775 | — | |

| Male tissues | SH_M2 | R. parkeri | 99 | JX134641 | ND |

| SH_M4 | R. amblyommii | 100 | JQ914776 | ND | |

| SH_M6 | R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum | 99 | JQ914777 | ND | |

| SH_M7 | R. amblyommii | 99 | JQ914778 | ND | |

| SH_M10 | R. amblyommii | 100 | JQ914779 | ND | |

| SH_M11 | R. amblyommii | 100 | JQ914780 | ND |

ND, not determined.

R. parkeri Quantification in A. maculatum

To further confirm the presence of R. parkeri in our field-collected ticks, we used a specific qPCR assay using ompB gene-specific primers and probe (Jiang et al. 2012). The male tick DNA samples were insufficient in concentration to test using the qPCR assay. The infection level of R. parkeri in the midgut samples ranged from 6 to 4,000 copies/μl, while the single pair of salivary gland that tested positive had an infection load of 1,794 copies/μl (Table 2). We observed some testing discrepancies in samples, in that some sequences with identity to R. parkeri based on ompA homology (Fig. 3) were not amplified in the more accurate qPCR assay. The apparent disparity could be because of the inherent difficulties in assigning Rickettsial species identity because of the small divergence between ompA sequences among rickettsial species (Fournier et al. 2003).

To study R. parkeri infection rate in field-collected A. maculatum, we expanded this assay to include more A. maculatum tick samples. The individual female tick carcasses (n = 83) (whole tick minus gut and salivary gland tissues) and male ticks (n = 5 groups; 3 per group) were screened for qPCR detection of R. parkeri. We observed a 32.5% infection rate in females samples (27 of 83), whereas three of five male tick samples tested positive for R. parkeri infection. Based on this assay, the R. parkeri infection level in field-collected A. maculatum showed 12–32% infection rate in field-collected female ticks.

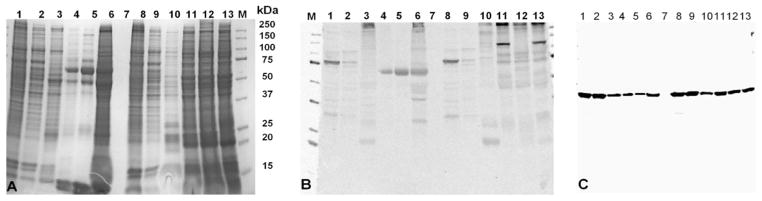

Immunodetection of R. parkeri in A. maculatum

Western blotting was performed to detect the R. parkeri expressed proteins in tick tissues and evaluate the efficacy of this antibody in future studies. R. parkeri polyclonal antibodies cross-reacted with 30, 75, and 100 kDa proteins in R. parkeri-infected Vero cells and the cell supernatant. These samples served as the positive control (Fig. 4). Rickettsia-free A. maculatum tick midgut and salivary gland supernatants (originating from a tick colony maintained at Texas A&M University) had no notable cross-reactivity to R. parkeri antibody with respect to positive controls. The R. parkeri polyclonal antibody cross-reacted with a ≈70 kDa protein (Fig. 4B, Lanes 4 and 5) in field-collected tick midgut tissues but cross-reacted with a ≈75 kDa protein (Fig. 4B, Lanes 11 and 12) in salivary glands tissues. The differences could be because of posttranslational modification of the immunogenic protein or they could represent entirely different proteins. The field-collected A. maculatum midgut and salivary gland tissues were infected with R. parkeri or R. endosymbionts, based on their carcass. The R. parkeri polyclonal antibody cross-reacted with protein species presumably associated with rickettsial infection in midguts (Fig. 4B, Lane 6; 70 kDa) and salivary glands (Fig. 4B, Lane 13; 70 kDa). The same blot was reprobed with monoclonal anti β-Actin labeled with peroxidase and showed cross-reactivity of a 42 kDa band in Vero cells and tick tissues. β-Actin was used to show the reference protein level in both the tick tissues and Vero cells (Fig. 4C). The SDS-gel stained with GelCode Blue was also included as a reference (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

A 4–20% SDS-PAGE stained with GelCode Blue (A) and its corresponding immunoblot demonstrating cross-reactivity to the R. parkeri antibody (B) and β-actin (C). Standard protein marker adjoining molecular size lane (M); Lanes 1 and 2 were R. parkeri grown in Vero cells and the corresponding cell supernatant (Lanes 8 and 9). Lane 7 was empty. Lanes 3 and 10 were A. maculatum (Texas A&M) midgut and salivary gland tissues, respectively (Rickettsia-free tissues); Lanes 4 and 5 (midgut tissues) and lanes 11 and 12 (corresponding salivary glands), respectively, from field-collected A. maculatum; Lane 6 (midgut) and lane 13 (salivary gland) of lab colony A. maculatum (infected with R. endosymbiont).

Discussion

This study revealed the microbial diversity in field-collected and lab-maintained A. maculatum tick midguts, salivary glands, and saliva. Importantly, F. endosymbionts were identified in all samples tested. The bacterial community of A. maculatum maintained in the laboratory showed an average relative abundance of the Francisella genus to be 35 and 98% in midgut and salivary gland tissues, respectively. As obligatory blood feeders, ticks are required to maintain a relatively simple and restrictive microbial community (Lalzar et al. 2012). The uniform presence of the Francisella genus represents a systemic association between arthropods and these bacteria. A more diverse bacterial community in A. maculatum was expected because of its interactions with different animal hosts while feeding in wild. In contrast, the bacterial community had abundant sequences assigned to the Francisella genus (80%), followed by Rickettsia (6%) and Wolbachia (4%) in field-collected A. maculatum salivary glands (Fig. 2). These findings are in agreement with previous reports for tick species. The abundance of Francisella species in tick tissues suggests that Francisella sustains an obligatory association with its tick hosts, and outcompetes other bacterial genera. The findings of Francisella, Rickettsia, and Wolbachia in field-collected ticks reported in this study support this assertion. Determining the extent to which field-collected ticks maintain endosymbionts (Francisella, Rickettsia, and Wolbachia), pathogens, or both, was outside the scope of this investigation. Bacteria from the Rickettsia and Wolbachia genus are known endosymbionts for several arthropod systems (Gottlieb et al. 2011). In this study, we detected bacteria from the genus Rickettsia and Wolbachia in tick salivary glands, but the bacterial density was significantly lower compared with Francisella. These findings support a facultative association between Rickettsia, Wolbachia, and ticks. The prevalence of obligatory or facultative endosymbionts in ticks has been proposed to be influenced by several factors including competition, increased virulence, and problems in vertical transmission (Mira and Moran 2002). Vector regulation of Francisella multiplication might explain the lower reads of Rickettsia and Wolbachia in A. maculatum salivary glands. Alternatively, interspecies competition of Rickettsia populations found (R. parkeri and R. endosymbiont) might result in decreased prevalence. In Dermacentor andersoni Stiles, the abundance of Rickettsia peacockii in tick ovaries was suggested to block transovarial transmission of R. rickettsii (Burgdorfer et al. 1981, Niebylski et al. 1997).

The survival or dominance of Enterobacteria in tick gut tissues (Fig. 2) could be under the control of the same mechanism that operates in mosquito guts, in that bloodmeal-induced oxidative stress results in a oxidative killing of many bacteria (Wang et al. 2011). The redox capacity of enteric bacteria may be important adaptation within blood-feeding arthropod guts, owing to high oxidative stress during blood metabolism. Francisella and Wolbachia, found in both midguts and salivary glands (Fig. 2), and Candidatus Devosia found predominantly in salivary glands (Fig. 2) are known endosymbionts (Scoles 2004, Vannini et al. 2004, Zhang et al. 2011). Wolbachia species have been proposed for use in insect pest control, importantly by Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility (Zabalou et al. 2004), and this methodology has been shown to block or reduce Plasmodium falciparum (malaria parasite) transmission from Anopheles gambiae Giles, 1902 (Hughes et al. 2011). Only the Francisella-like endosymbionts were found in lab-colony salivary glands while both the Francisella-like endosymbiont and Rickettsia (Figs. 1 and 2) were detected in field-collected salivary glands, suggesting further study is warranted to understand their interaction with their host.

Symbionts are classified as obligate, providing nutrient supplements to their arthropod host, or facultative, aiding in immunity (Moran et al. 2008). The presence of the facultative symbiont, Wolbachia, has been shown to result in upregulated immune genes on pathogen infection in Drosophila melanogastor and Aedes aegypti L. (Rances et al. 2012, Eleftherianos et al. 2013). Clearly, the presence of F. endosymbionts in A. maculatum is of fundamental significance, given their occurrence in numerous other tick species including Dermacentor variabilis (Say, 1821), D. andersoni, Dermacentor hunteri Bishopp, 1912, Dermacentor nitens Neumann, 1897, Dermacentor occidentalis Marx, 1892, and Dermacentor albipictus (Packard) (Niebylski et al. 1997, Sun et al. 2000, Scoles 2004), but the nature of this symbiotic relationship has not yet been determined.

Interestingly, Rickettsia reads were present in saliva (Fig. 1), suggesting rickettsial secretion from salivary glands. The detection of Rickettsia in midgut, salivary glands, and saliva is important with respect to the possible pathogen development cycle. The putative trafficking route in ticks begins with midgut tissues acquiring or harboring the pathogen from an infected vertebrate host, the development and replication, trafficking to the salivary glands, and finally transmission to a mammalian host via salivation (De Silva and Fikrig 1995). Interestingly, the only Rickettsia species we identified in A. maculatum salivary glands was R. parkeri, supporting its unique ability to migrate from midgut to salivary gland (Table 2).

We detected R. parkeri, R. amblyommii, and R. endosymbiont of A. maculatum in field-collected A. maculatum. R. parkeri has been frequently reported from different field-collected A. maculatum (Cohen et al. 2009, Paddock et al. 2010, Trout et al. 2010, Varela–Stokes et al. 2011, Wright et al. 2011), with an estimated infection rate of 28.1–41%, similar to this study. Similarly, R. amblyommii has been identified in many different Amblyomma species (Labruna et al. 2004; Apperson et al. 2008; Ogrzewalska et al. 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011; Jiang et al. 2010; Bermudez et al. 2011). Culturing rickettsial endosymbionts from the soft tick, Carios capanensis (Neumann, 1901), has been attempted (Mattila et al. 2007), but complete characterization remains incomplete. The public health significance of R. parkeri was recognized more than 60 yr after its discovery in A. maculatum (Parker et al. 1939, Paddock et al. 2004). In addition, a human rickettsiosis originating from R. amblyommii infection has been recently reported (Apperson et al. 2008). In fact, the pathogenicity of many rickettsial agents (which may include tick endosymbionts) remains unknown because of the lack of specific diagnostic approaches, minor differences in clinical symptoms, and the fact the same antibiotic regimen is prescribed for all rickettsial infections.

Stenotrophomonas, Pseudomonas, Rhodococcus, and Propriobacterium in A. maculatum were reported in Ixodes ricinus L. and were proposed to be part of the core microbiome of Ixodid ticks (Carpi et al. 2011); however, specific or functional classification has not yet been achieved (Moran et al. 2008). The detection of Mycobacterium, Bacillus, Streptococcus, Clostridium, Streptomyces, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Papilibacter, Coprococcus, Eubacterium, Roseburia, Pantoea, Ruminococcus, and many other environmental and soil bacterial genera identified in this study have previously been reported in ticks (Andreotti et al. 2011, Carpi et al. 2011).

In this study, we attempted the detection of R. parkeri in tick tissues using a mouse-generated polyclonal R. parkeri antibody. However, rickettsial polyclonal antibodies extensively cross-react with antigens from many different Rickettsial species (Anderson and Tzianabos 1989), and, currently, this prevents the use of Rickettsial antibodies as a means of specific detection of Rickettsial species in tick tissues. The use of a species-specific rickettsial antibody with cross-adsorption could provide a specific determination of R. parkeri (Raoult and Paddock 2005). The differences in antibody reactivity in Vero cells and the tick tissues (Fig. 4) could be because of different antigen expression profiling of R. parkeri in mammalian (Vero cell) and arthropod systems (tick). Differences in antigenic profiling was reported in Ehrlichia chaffeensis-infected tick and mammalian cells (Kuriakose et al. 2011). Overall, these data underscore the difficulty in serological differentiation among Rickettsia.

In conclusion, we described the A. maculatum microbiome and further confirmed R. parkeri infection, which could be the basis of future studies examining the interactions between R. parkeri and the tick microbiome. The known pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes likely interact with the tick vector, and a better understanding of these interactions could open new avenues for vector and disease control. The manipulation of the microbial communities by altering or inhibiting the growth of a particular bacterial strain could alter pathogen transmission (Hughes et al. 2011). The mechanism by which the tick midgut microbiome influences pathogenic rickettsial development could be used for tick-borne disease control strategies. Moreover, elucidating the precise role of the endosymbionts on the regulation of the immune response and the corresponding pathogenic response of R. parkeri, will continue to be of considerable research interest. Further studies will focus on the influence the microbiome has on pathogen survivability, virulence, and development within the tick vector and the relationship between various symbionts and tick immunity with emphasis to F. endosymbionts and numerous Rickettsiae.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH–NIAID) A1099919, U.S. Department of State (US DOS) PGA-P21049, and Work Unit Number (WUN) 6000.RAD1.J.A0310 (to Naval Medical Research Center). We thank Mississippi Functional Genomics Network core facility supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health award (P20RR016476).

Footnotes

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Navy, the Naval service at large, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. C.C.C. and W.M.C. are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties, and “copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.”

References Cited

- Anderson BE, Tzianabos T. Comparative sequence analysis of a genus-common rickettsial antigen gene. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5199–5201. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5199-5201.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti R, Perez de Leon AA, Dowd SE, Guerrero FD, Bendele KG, Scoles GA. Assessment of bacterial diversity in the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus through tag-encoded pyrosequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apperson CS, Engber B, Nicholson WL, Mead DG, Engel J, Yabsley MJ, Dail K, Johnson J, Watson DW. Tick-borne diseases in North Carolina: is “Rickettsia amblyommii” a possible cause of rickettsiosis reported as Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:597–606. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez CS, Zaldivar AY, Spolidorio MG, Moraes–Filho J, Miranda RJ, Caballero CM, Mendoza Y, Labruna MB. Rickettsial infection in domestic mammals and their ectoparasites in El Valle de Anton, Cocle, Panama. Vet Parasitol. 2011;177:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair PJ, Jiang J, Schoeler GB, Moron C, Anaya E, Cespedes M, Cruz C, Felices V, Guevara C, Mendoza L, et al. Characterization of spotted fever group rickettsiae in flea and tick specimens from northern Peru. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.4961-4967.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorfer W, Hayes SF, Mavros AJ. Non-pathogenic Rickettsiae in Dermacentor andersoni: a limiting factor for the distribution of Rickettsia rickettsii. In: Burgdorferi W, Anacker RL, editors. Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Diseases. Academic; New York, NY: 1981. pp. 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorfer W, Brinton LP, Hughes LE. Isolation and characterization of symbiotes from the Rocky Mountain wood tick, Dermacentor andersoni. J Invertebr Pathol. 1973;22:424–434. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(73)90173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone KA, Dowd SE, Stamatas GN, Nikolovski J. Diversity of the human skin microbiome early in life. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:2026–2032. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpi G, Cagnacci F, Wittekindt NE, Zhao F, Qi J, Tomsho LP, Drautz DI, Rizzoli A, Schuster SC. Metagenomic profile of the bacterial communities associated with Ixodes ricinus ticks. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay K, Klyachko O, Grindle N, Civitello D, Oleske D, Fuqua C. Microbial communities and interactions in the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:4371–4381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2008.03914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Yabsley MJ, Garrison LE, Freye JD, Dunlap BG, Dunn JR, Mead DG, Jones TF, Moncayo AC. Rickettsia parkeri in Amblyomma americanum ticks, Tennessee and Georgia, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1471–1473. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva AM, Fikrig E. Growth and migration of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ticks during blood feeding. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:397–404. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd SE, Callaway TR, Wolcott RD, Sun Y, Mc-Keehan T, Hagevoort RG, Edrington TS. Evaluation of the bacterial diversity in the feces of cattle using 16S rDNA bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP) BMC Microbiol. 2008a;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd SE, Sun Y, Wolcott RD, Domingo A, Carroll JA. Bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP) for microbiome studies: bacterial diversity in the ileum of newly weaned Salmonella-infected pigs. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2008b;5:459–472. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd SE, Hanson JD, Rees E, Wolcott RD, Zischau AM, Sun Y, White J, Smith DM, Kennedy J, Jones CE. Survey of fungi and yeast in polymicrobial infections in chronic wounds. J Wound Care. 2011;20:40–47. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2011.20.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumler JS, Barbet AF, Bekker CP, Dasch GA, Palmer GH, Ray SC, Rikihisa Y, Rurangirwa FR. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and ‘HGE agent’ as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:2145–2165. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-6-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleftherianos I, Atri J, Accetta J, Castillo JC. Endosymbiotic bacteria in insects: guardians of the immune system? Front Physiol. 2013;4:46. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren AM, Zozaya M, Taylor CM, Dowd SE, Martin DH, Ferris MJ. Exploring the diversity of Gardnerella vaginalis in the genitourinary tract microbiota of monogamous couples through subtle nucleotide variation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco RC, Fish D. Prevalence of Ixodes dammini near the homes of Lyme disease patients in Westchester County, New York. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:826–830. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier PE, Dumler JS, Greub G, Zhang J, Wu Y, Raoult D. Gene sequence-based criteria for identification of new rickettsia isolates and description of Rickettsia heilongjiangensis sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5456–5465. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5456-5465.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb Y, Perlman SJ, Chiel E, Zchori–Fein E. Rickettsia get around. In: Zchori–Fein, Bourtzis K, editors. Manipulative Tenants-Bacteria Associated With Arthropods. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2011. pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hasle G, Bjune G, Edvardsen E, Jakobsen C, Linnehol B, Roer JE, Mehl R, Roed KH, Pedersen J, Leinaas HP. Transport of ticks by migratory passerine birds to Norway. J Parasitol. 2009;95:1342–1351. doi: 10.1645/GE-2146.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GL, Koga R, Xue P, Fukatsu T, Rasgon JL. Wolbachia infections are virulent and inhibit the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002043. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov IN, Mitkova N, Reye AL, Hubschen JM, Vatcheva–Dobrevska RS, Dobreva EG, Kantardjiev TV, Muller CP. Detection of new Francisella-like tick endosymbionts in Hyalomma spp. and Rhipicephalus spp. (Acari: Ixodidae) from Bulgaria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:5562–5565. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02934-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Yarina T, Miller MK, Stromdahl EY, Richards AL. Molecular detection of Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma americanum parasitizing humans. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:329–340. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Stromdahl EY, Richards AL. Detection of Rickettsia parkeri and Candidatus Rickettsia andeanae in Amblyomma maculatum Gulf Coast ticks collected from humans in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:175–182. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim S, Essenberg RC, Dillwith JW, Tucker JS, Bowman AS, Sauer JR. Identification of SNARE and cell trafficking regulatory proteins in the salivary glands of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum (L.) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1711–1721. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirans JE, Litwak TR. Pictorial key to the adults of hard ticks, family Ixodidae (Ixodida: Ixodoidea), east of the Mississippi River. J Med Entomol. 1989;26:435–448. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/26.5.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose JA, Miyashiro S, Luo T, Zhu B, McBride JW. Ehrlichia chaffeensis transcriptome in mammalian and arthropod hosts reveals differential gene expression and post transcriptional regulation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Horta MC, Bouyer DH, McBride JW, Pinter A, Popov V, Gennari SM, Walker DH. Rickettsia species infecting Amblyomma cooperi ticks from an area in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil, where Brazilian spotted fever is endemic. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:90–98. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.90-98.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalzar I, Harrus S, Mumcuoglu KS, Gottlieb Y. Compsoition and seasonal variation of Rhipicephalus turanicus and Rhipicephalus sanguineus bacterial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4110–4116. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00323-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mira A, Moran NA. Estimating population size and transmission bottlenecks in maternally transmitted endosymbiotic bacteria. Microb Ecol. 2002;44:137–143. doi: 10.1007/s00248-002-0012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila JT, Burkhardt NY, Hutcheson HJ, Munderloh UG, Kurtti TJ. Isolation of cell lines and a rickettsial endosymbiont from the soft tick Carios capensis (Acari: Argasidae: Ornithodorinae) J Med Entomol. 2007;44:1091–1101. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[1091:ioclaa]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menchaca AC, Visi DK, Strey OF, Teel PD, Kalinowski K, Allen MS, Williamson PC. Preliminary assessment of microbiome changes following blood-feeding and survivorship in the Amblyomma americanum nymph-to-adult transition using semiconductor sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran NA, McCutcheon JP, Nakabachi A. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraru GM, Goddard J, Paddock CD, Varela–Stokes A. Experimental infection of cotton rats and bobwhite quail with Rickettsia parkeri. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:70. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham GR, Sauer JR. Involvement of calcium and cyclic AMP in controlling ixodid tick salivary fluid secretion. J Parasitol. 1979;65:531–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebylski ML, Peacock MG, Fischer ER, Porcella SF, Schwan TG. Characterization of an endosymbiont infecting wood ticks, Dermacentor andersoni, as a member of the genus Francisella. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3933–3940. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3933-3940.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Munderloh UG, Kurtti TJ. Endosymbionts of ticks and their relationship to Wolbachia spp. and tick-borne pathogens of humans and animals. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3926–3932. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3926-3932.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrzewalska M, Pacheco RC, Uezu A, Ferreira F, Labruna MB. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting wild birds in an Atlantic forest area in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil, with isolation of rickettsia from the tick Amblyomma longirostre. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:770–774. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[770:taiiwb]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrzewalska M, Pacheco RC, Uezu A, Richtzenhain LJ, Ferreira F, Labruna MB. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting birds in an Atlantic rain forest region of Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:1225–1229. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrzewalska M, Uezu A, Labruna MB. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting wild birds in the eastern Amazon, northern Brazil, with notes on rickettsial infection in ticks. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:809–816. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrzewalska M, Uezu A, Labruna MB. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting wild birds in the Atlantic Forest in northeastern Brazil, with notes on rickettsial infection in ticks. Parasitol Res. 2011;108:665–670. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Goddard J, McLellan SL, Tamminga CL, Ohl CA. Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:805–811. doi: 10.1086/381894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Fournier PE, Sumner JW, Goddard J, Elshenawy Y, Metcalfe MG, Loftis AD, Varela–Stokes A. Isolation of Rickettsia parkeri and identification of a novel spotted fever group Rickettsia sp. from Gulf Coast ticks (Amblyomma maculatum) in the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2689–2696. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02737-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RR, Kohls GM, Cox GW, Davis GE. Observations on an infectious agent from Amblyomma maculatum. Public Health Rep. 1939;54:1482–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:719–756. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.719-756.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rances E, Ye YH, Woolfit M, McGraw EA, O’Neill SL. The relative importance of innate immune priming in Wolbachia-mediated dengue interference. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002548. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D, Roux V. Rickettsioses as paradigms of new or emerging infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:694–719. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D, Paddock CD. Rickettsia parkeri infection and other spotted fevers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:626–627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200508113530617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM, Evans PM, MacSwain JL, Sauer J. Amblyomma americanum: characterization of salivary prostaglandins E2 and F2 alpha by RP-HPLC/bio-assay and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Exp Parasitol. 1992;74:112–116. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90145-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi L, Bigliardi E, Corona S, Beninati T, Lo N, Franceschi A. A symbiont of the tick Ixodes ricinus invades and consumes mitochondria in a mode similar to that of the parasitic bacterium Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. Tissue Cell. 2004;36:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoles GA. Phylogenetic analysis of the Francisella-like endosymbionts of Dermacentor ticks. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:277–286. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine DE. Biology of ticks. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sun LV, Scoles GA, Fish D, O’Neill SL. Francisella-like endosymbionts of ticks. J Invertebr Pathol. 2000;76:301–303. doi: 10.1006/jipa.2000.4983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson KS, Dowd SE, Suchodolski JS, Middelbos IS, Vester BM, Barry KA, Nelson KE, Torralba M, Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, et al. Phylogenetic and gene-centric metagenomics of the canine intestinal microbiome reveals similarities with humans and mice. ISME J. 2011;5:639–649. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teel PD, Ketchum HR, Mock DE, Wright RE, Strey OF. The Gulf Coast tick: a review of the life history, ecology, distribution, and emergence as an arthropod of medical and veterinary importance. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:707–722. doi: 10.1603/me10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trout R, Steelman CD, Szalanski AL, Williamson PC. Rickettsiae in Gulf Coast ticks, Arkansas, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:830–832. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uilenberg G. Experimental transmission of Cowdria ruminantium by the Gulf coast tick Amblyomma maculatum: danger of introducing heartwater and benign African theileriasis onto the American mainland. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43:1279–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini C, Rosati G, Verni F, Petroni G. Identification of the bacterial endosymbionts of the marine ciliate Euplotes magnicirratus (Ciliophora, Hypotrichia) and proposal of ‘Candidatus Devosia euplotis’. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1151–1156. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02759-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela–Stokes AS, Paddock CD, Engber B, Toliver M. Rickettsia parkeri in Amblyomma maculatum ticks, North Carolina, USA, 2009–2010. Emerg. Infect Dis. 2011;17:2350–2353. doi: 10.3201/eid1712.110789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcins IM, Old JM, Deane E. Molecular detection of Rickettsia, Coxiella and Rickettsiella DNA in three native Australian tick species. Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;49:229–242. doi: 10.1007/s10493-009-9260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DH, Ismail N. Emerging and re-emerging rickettsioses: endothelial cell infection and early disease events. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Gilbreath TM, 3rd, Kukutla P, Yan G, Xu J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CL, Nadolny RM, Jiang J, Richards AL, Sonenshine DE, Gaff HD, Hynes WL. Rickettsia parkeri in Gulf Coast ticks, southeastern Virginia, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:896–898. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabalou S, Riegler M, Theodorakopoulou M, Stauffer C, Savakis C, Bourtzis K. Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means for insect pest population control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15042–15045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403853101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Norris DE, Rasgon JL. Distribution and molecular characterization of Wolbachia endosymbionts and filarial nematodes in Maryland populations of the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2011;77:50–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J, Jasinskas A, Barbour AG. Antibiotic treatment of the tick vector Amblyomma americanum reduced reproductive fitness. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]