Abstract

There has been a worldwide increase in community-associated (CA) methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. CA-MRSA isolates commonly produce the Panton-Valentine leukocidin toxin encoded by the pvl genes lukF-PV and lukS-PV. This study investigated the clinical and molecular epidemiologies of pvl-positive MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) isolates identified by the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory (NMRSARL) between 2002 and 2011. All pvl-positive MRSA (n = 190) and MSSA (n = 39) isolates underwent antibiogram-resistogram typing, spa typing, and DNA microarray profiling for multilocus sequence type, clonal complex (CC) and/or sequence type (ST), staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type assignment, and virulence and resistance gene detection. Where available, patient demographics and clinical data were analyzed. The prevalence of pvl-positive MRSA increased from 0.2% to 8.8%, and that of pvl-positive MSSA decreased from 20% to 2.5% during the study period. The pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA isolates belonged to 16 and 5 genotypes, respectively, with CC/ST8-MRSA-IV, CC/ST30-MRSA-IV, CC/ST80-MRSA-IV, CC1/ST772-MRSA-V, CC30-MSSA, CC22-MSSA, and CC121-MSSA predominating. Temporal shifts in the predominant pvl-positive MRSA genotypes and a 6-fold increase in multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA genotypes occurred during the study period. An analysis of patient data indicated that pvl-positive S. aureus strains, especially MRSA strains, had been imported into Ireland several times. Two hospital and six family clusters of pvl-positive MRSA were identified, and 70% of the patient isolates for which information was available were from patients in the community. This study highlights the increased burden and changing molecular epidemiology of pvl-positive S. aureus in Ireland over the last decade and the contribution of international travel to the influx of genetically diverse pvl-positive S. aureus isolates into Ireland.

INTRODUCTION

Usually, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is considered to be a health care-associated (HCA) pathogen, and it is frequently responsible for serious and often life-threatening infections in individuals with established risk factors, such as prolonged hospital stay and antibiotic usage, older age, recent surgery, or an immunocompromised state. Health care-associated MRSA isolates have been found to belong to five distinct clonal lineages, typically harbor the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type I, II, or III, (or less frequently, SCCmec type IV, VI, or VIII), and often exhibit resistance to multiple classes of antimicrobial agents (1).

However, during the last decade, there has been a concurrent worldwide increase in the prevalence of community-associated (CA) MRSA infections among otherwise healthy individuals, often children and young adults, who exhibit none of the HCA risk factors (2, 3). These consist predominantly of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) but also include necrotizing pneumonia, necrotizing fasciitis, and sepsis (2, 4–6). The pathogenesis of CA-MRSA has in some studies been attributed to the ability of these organisms to express the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin (3, 7). Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive MRSA infections have been reported in many different populations, particularly those in close contact or in poor socioeconomic situations (2).

Panton-Valentine leukocidin is a bicomponent beta-barrel toxin that causes leukocyte lysis or apoptosis via pore formation (8). PVL is encoded by two genes, lukF-PV and lukS-PV, which are carried on a variety of lysogenic bacteriophages (9). While outbreaks of PVL-producing methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) isolates were reported in the 1950s and 1960s (10), PVL was first reported in newly emerging CA-MRSA strains in the 1990s (4, 11). While not all CA-MRSA isolates produce PVL, and there are conflicting data regarding the role of PVL in the pathogenesis of CA-MRSA infection, it is clear that the success of some CA-MRSA clones is associated with PVL, albeit not exclusively (12).

MRSA isolates carrying the PVL toxin genes (pvl) are predominantly genetically distinct from HCA-MRSA, as they belong to more diverse clonal lineages and harbor the smaller SCCmec elements type IV, V, or VT, and they are frequently not multiresistant (1, 3, 13). Different pvl-positive MRSA clones predominate in different regions, e.g., sequence type 8 (ST8)-MRSA-IV (USA300) in the United States (14), ST59-MRSA-VT in Asia (13, 15), ST30-MRSA-IV in New Zealand (16), ST93-MRSA-IV in Australia (17), ST80-MRSA-IV in Europe (18) and the Middle East (1), ST88-MRSA-IV in Africa (19), and ST22-MRSA-IV and ST772-MRSA-V in India (20). However, recent studies highlighted the complex and changing epidemiology of pvl-positive MRSA, including (i) considerable variation in the prevalence rates of pvl-positive MRSA in different regions of the world (2, 17), (ii) the increasing prevalence and polyclonal population structure of pvl-positive MRSA isolates in Europe (1, 21, 22), (iii) the increasing prevalence of ST8-MRSA-IV in Europe and the decreasing prevalence of ST80-MRSA-IV (21), (iv) the increasing prevalence of multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA (22), and (v) the spread of pvl-positive MRSA into hospitals (14, 23–25). Furthermore, there has been an increasing frequency of reports of infections associated with pvl-positive MSSA (26, 27) that produce similar clinical presentations as pvl-positive MRSA, and the former are a potential reservoir for the emergence of pvl-positive MRSA.

In Ireland, MRSA is endemic in hospitals, and since 2002, the pvl-negative ST22-MRSA-IV clone has accounted for 70 to 80% of MRSA from bloodstream infections (BSIs) each year (28, 29). Between 1999 and 2005, a prevalence rate of 1.8% was reported for pvl-positive MRSA in Ireland, and six distinct pvl-positive MRSA clones (ST30, ST8, ST22, ST80, ST5, and ST154, all harboring SCCmec IV) were identified, some of which were probably imported (30). In 2011, we reported multiple importations of the multiresistant pvl-positive ST772-MRSA-V clone into Ireland and a cluster of this clone in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in an Irish hospital (31). However, there have been no published data on the overall prevalence and molecular epidemiological characteristics of the pvl-positive MRSA population in Ireland since 2005 and only a single report of a familial outbreak of pvl-positive MSSA in Ireland; no molecular epidemiological typing of the isolates was undertaken (32). The purpose of the present study was to investigate the clinical and molecular epidemiologies of pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA identified by the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory (NMRSARL) between 2002 and 2011.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

The NMRSARL investigated 7,103 S. aureus isolates (6,702 MRSA and 401 MSSA) between 2002 and 2011, of which 1,531 were examined for the presence of the lukF-PV and lukS-PV genes (pvl) (Table 1). An isolate was selected for pvl investigation if it was recovered from a suspected pvl-associated infection; for MRSA only, an isolate was selected if it exhibited an antibiogram-resistogram (AR) pattern and/or pulsed-field group (PFG) distinct from that of previously or currently predominant pvl-negative health care-associated MRSA clones, e.g., AR-PFG 06-01, indicative of ST22-MRSA-IV or AR-PFG 13/14-00, indicative of ST8-MRSA-IIA-E ± SCCM1 (28, 33). Of the 1,532 isolates investigated for pvl (1,217 MRSA and 315 MSSA), 229 (190 MRSA and 39 MSSA) were pvl positive and were investigated further (Table 1). This included 24/25 previously described pvl-positive MRSA isolates recovered between 2002 and 2005 (30) and 18 previously described pvl-positive ST772-MRSA-V isolates recovered between 2009 and 2011 (31). One MRSA isolate (E1760) previously reported as pvl positive (30) was excluded from the present study because pvl was not detected despite several attempts using PCR and DNA microarray profiling. Only one isolate per patient was investigated unless AR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing indicated the presence of a second strain from a particular patient. When possible, patient demographics and clinical data were collected from isolate submission forms, telephone follow-ups, and follow-up questionnaires. The isolates were defined as clusters if they were recovered from members of one family/household, within a hospital, or both. Within each cluster, the isolates were recovered between 3 months and 2 years apart. Each isolate within a cluster was recovered from a different person or environmental source. This paper does not include any identifying or potentially identifying patient information.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA isolates identified each year between 2002 and 2011 by the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory

| yr | MRSA isolates |

MSSA isolates |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. identified by NMRSARL | No. investigated for pvla | No. (%) confirmed pvl positiveb | No. identified by NMRSARL | No. investigated for pvla | No. (%) confirmed pvl positiveb | |

| 2002 | 497 | 8 | 1 (0.2)c | 1 | 1 | 1 (100) |

| 2003 | 599 | 17 | 4 (0.7)c | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| 2004 | 724 | 134 | 10 (1.4)c | 15 | 14 | 3 (20) |

| 2005 | 827 | 112 | 9 (1.1)c | 43 | 30 | 5 (11.6) |

| 2006 | 869 | 110 | 12 (1.4) | 41 | 31 | 5 (12.2) |

| 2007 | 782 | 120 | 17 (2.2) | 42 | 29 | 6 (14.3) |

| 2008 | 747 | 179 | 37 (5.0) | 58 | 53 | 7 (12.1) |

| 2009 | 605 | 187 | 32 (5.3)d | 44 | 35 | 5 (11.4) |

| 2010 | 596 | 160 | 28 (4.7)d | 77 | 61 | 5 (6.5) |

| 2011 | 456 | 190 | 40 (8.8)d | 81 | 61 | 2 (2.5) |

| Total | 6,702 | 1,217 | 190 (2.8) | 401 | 315 | 39 (9.7) |

An isolate was selected for pvl investigation if it was from a suspected pvl-associated infection or, for MRSA only, if the isolate exhibited an antibiogram-resistogram (AR) and pulsed-field group (PFG) pattern distinct from that of previously or currently predominant pvl-negative health care-associated MRSA clones, e.g., AR-PFG 06-01, indicative of ST22-MRSA-IV, or AR-PFG 13/14-00, indicative of ST8-MRSA-IIA-E ± SCCM1.

The values shown in parentheses indicate the percentages of pvl-positive MRSA or MSSA isolates identified among the total number of MRSA or MSSA isolates investigated by the NMRSARL each year during the study period.

The MRSA isolates recovered between 2002 and 2005 were described previously (30). One MRSA isolate (E1760) from that study was excluded because pvl was not detected, despite several attempts using PCR and DNA microarray profiling.

One, eight, and nine pvl-positive isolates recovered in 2009, 2010, and 2011, respectively, were described previously (31).

Confirmation of isolates as S. aureus, methicillin susceptibility testing, and detection of the lukF-PV and lukS-PV genes.

On receipt by the NMRSARL, all S. aureus isolates were inoculated onto Protect beads (Technical Service Consultants Ltd., Heywood, United Kingdom) and stored at −70°C prior to subsequent investigation. The isolates were confirmed to be S. aureus using the tube coagulase test, and methicillin resistance was investigated with 10-μg and 30-μg cefoxitin discs (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom), as described previously (30). The detection of the lukF-PV and lukS-PV genes was performed by PCR, as described previously (4); isolates recovered in the final quarter of 2011 were tested using an in-house real-time PCR assay designed to detect the mecA, nuc, and pvl genes. The identification of isolates as S. aureus, the presence or absence of mecA, and the presence of the lukF-PV and lukS-PV genes were also confirmed in all isolates using DNA microarray profiling, as described below.

Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of pvl-positive S. aureus isolates.

All 229 pvl-positive S. aureus isolates underwent antimicrobial susceptibility testing, spa typing, and DNA microarray profiling. For the 18 pvl-positive ST772-MRSA-V isolates included in the study, this analysis was performed previously, and three of these isolates also underwent multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (31). The 24 previously described pvl-positive MRSA isolates recovered between 2002 and 2005 included in the study underwent previous antimicrobial susceptibility, MLST, SCCmec typing, and toxin gene profiling for a limited number of toxin genes (30).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The susceptibility of each isolate to a panel of 23 antimicrobial agents was determined by disk diffusion, as described previously (30). The antimicrobial agents tested were amikacin, ampicillin, cadmium acetate, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, ethidium bromide, fusidic acid, gentamicin, kanamycin, lincomycin, mercuric chloride, mupirocin, neomycin, phenyl mercuric acetate, rifampin, spectinomycin, streptomycin, sulfonamide, tetracycline, tobramycin, trimethoprim, and vancomycin.

DNA microarray analysis.

DNA microarray analysis was performed on all isolates using the StaphyType kit (Alere Technologies GmbH, Jena, Germany), which simultaneously detects 333 S. aureus gene targets, including species markers, antimicrobial resistance and virulence-associated genes (including lukF-PV, lukS-PV and mecA), and SCCmec-associated genes and typing markers allowing isolates to be assigned to MLST sequence types (STs) and/or clonal complexes (CCs), and SCCmec types (34, 35). The DNA microarray procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR detection of antimicrobial resistance genes.

Isolates that exhibited phenotypic resistance to particular antimicrobial agents for which associated resistance genes were not detected by the DNA microarray, or for which resistance genes were detected but partial or none of the associated resistance phenotypes were detected, were further investigated by PCR to confirm the presence or absence of these resistance genes. These investigations included PCRs using previously described primers to detect mupA (36), aphA3 (37), aacA-aphD (37), fusB (38), tet(K) (36), tet(M) (36), aadD (39), and qacA (40), and also novel primers to detect qacC, msr(A), dfrS1, lnu(A), mph(C), and blaZ (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Statistical analysis.

A two-sample z test was used to assess the significance of the difference between the two population proportions. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 229 pvl-positive S. aureus isolates were identified by the NMRSARL between 2002 and 2011, including 190 MRSA and 39 MSSA isolates representing 2.8% and 9.7% of all MRSA and MSSA isolates, respectively, submitted to the NMRSARL during this time (Table 1). Overall, the prevalence of pvl-positive MRSA among all MRSA isolates submitted to the NMRSARL increased significantly during the study period (P < 0.0005) from 0.2% in 2002 (1/497) to 8.8% (40/456) in 2011, with those two specific years recording the lowest and highest prevalence rates, respectively (Table 1). In contrast, for pvl-positive MSSA, the prevalence rate among all MSSA isolates submitted to the NMRSARL decreased significantly (P < 0.0005) from 20% in 2004 (3/15) to 2.5% (2/81) in 2011 (Table 1).

Genotyping.

The pvl-positive MRSA (n = 190) and MSSA (n = 39) isolates were assigned to 11 and five MLST clonal complexes (CCs), respectively (Table 2). For MRSA, the isolates were assigned to either SCCmec type IV (79.5% [151/190]) or V (20.5% [39/190]), and to 16 genotypes (CC/ST-SCCmec types) (Table 2), with CC/ST8-MRSA-IV predominating (33.7% [64/190]), followed by CC/ST30-MRSA-IV (21.1% [40/190]), CC/ST80-MRSA-IV (14.2% [27/190]), CC1/ST772-MRSA-V (13.2% [25/190]), CC/ST22-MRSA-IV (6.3% [12/190]), ST59/952-MRSA-V (4.7% [9/190]), ST93-MRSA-IV (3/190 [1.6%]), and CC1-MRSA-IV (1.1% [2/190]) (Table 2). The remaining eight MRSA genotypes were each represented by one isolate only (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic and genotypic typing data for pvl-positive MRSA (n = 190) and MSSA (n = 39) isolates identified by the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory between 2002 and 2011

| CCa | Typing category results (n): |

Antibiotic resistance profiles |

Virulence genes (% indicated when not 100%)e | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotypea |

spab | agra | Capsulea | IECa,b,c | |||||

| MRSA | MSSA | Phenotype (% indicated when not 100%)d | Genotype (% indicated when not 100%) | ||||||

| 1 | CC1-MRSA-IV (2) | t128 (1), t8968 (1) | III | 8 | D (1), B (1) | AMP, CAD, TET (50) | blaZ, sdrM, tet(K) (50) | sea (50), sec&sel (50), sek&seq (50), seh | |

| ST772-MRSA-V (25) | t657 (24), t345 (1) | II | 5 | Novel: scn&sea | AMP, AMI, CAD (88), CIP, ERY, GEN, KAN, NEO, TOB, TMP | blaZ, sdrM, msr(A), mph(C), aacA-aphD, aphA3&sat, fosB | sea, sec&sel, egc | ||

| CC1-MRSA-V (1) | t127 | III | 8 | D | AMP, FUS, GEN, KAN, NEO, TOB, TET | blaZ, sdrM, aacA-aphD, aphA3&sat, tet(K), tet(M), fusC | sea, sek&seq, seh | ||

| CC1-MSSA (4) | t127 (2), t177 (1), t12303 (1) | III | 8 | D | AMP, CAD (75), FUS, KAN (25), NEO (25) | blaZ, sdrM, aphA3&sat (25), ileS2 (50), fusC, qacA (50) | sea, sek&seq, seh | ||

| 5 | CC5-MRSA-V (1) | t311 | II | 5 | A | AMP, CAD, TET, TMP | blaZ, sdrM, tet(K), dfrS1, fosB | sea, edinA, egc | |

| CC5-MRSA-IV (1) | t311 | II | 5 | A | AMP, CAD | blaZ, sdrM, fosB | sea, edinA, egc | ||

| 8 | CC/ST8-MRSA-IV (64) | t008 (47), t051 (4), 121 (3), t068 (2), t4229 (1), t304 (1), t024 (1), t681 (1), t4306 (1), t11157 (1), t596 (1), t1635 (1) | I | 5 | B (63), neg (1) | AMI (21.8), AMP, CAD (20.3) (I), CHL (1.5), CIP (46.9), ERY (84.3), GEN (1.5), KAN (81.3), LIN (3.1), MC (6.3), MUP (1.5), NEO (81.3), PMA (1.5), TOB (1.5), TET, (9.4) TMP (3.1), LNZ (1.6) | blaZ (90.6), sdrM, tet(K) (9.4), lnu(A) (3.1), msr(A) (84.3), mph(C) (84.3), aacA-aphD (1.5), aphA3&sat (81.3), fosB (100), merA&merB (6.3), qacC (4.7), ileS2 (1.5), cfr&fexA (1.5), dfrS1 (3.1) | sek&seq (96.9), sed, sej&ser (4.7), ACME (89.1) | |

| CC8-MRSA-V (1) | t008 | I | 5 | B | AMP | sdrM, fosB | sek&seq, ACME | ||

| 22 | CC/ST22-MRSA-IV (12) | t852 (7), t2480 (1), t3107 (1), t4463 (1), t5422 (1), t005 (1) | I | 5 | B (11), neg (1) | AMI (25), AMP, CAD (50), CIP (75), ERY (66.7), GEN (25), KAN (91.7), NEO (33.3), TOB (91.7), TMP (66.7) | blaZ, aacA-aphD (91.7), dfrS1 (66.7), erm(C) (66.7), aadD (75) | egc | |

| CC22-MSSA (10) | t005 (7), t891 (2), t1869 (1) | I | 5 | B | AMI (10), AMP, CAD (60), FUS (10), GEN (80), KAN, TOB (90), TMP (90) | blaZ, aacA-aphD, dfrS1 (90) | egc | ||

| 30 | CC/ST30-MRSA-IV (40) | t019 (22), t012 (12), 3800 (2), t122 (1), t275 (1), t318 (1), t9904 (1) | III | 8 | B (37), A (2), neg (1) | AMP, CAD (82.5), CIP (5), FUS (35), TET (2.5), TMP (2.5) | blaZ, sdrM, tet(K) (2.5), fosB, dfrS1 (2.5), fusC (35) | sea (5), tst (35), egc | |

| CC30-MSSA (15) | t021 (6), t318 (4), t990 (1), t3502 (1), t1055 (1), t11156 (1), t433 (1) | III | 8 | A (2), B (11), neg (3) | AMP (73.3), CAD, CIP, ERY (6.7), TET (13.3), TMP (13.3) | blaZ (73.3), mph(C) (6.7), sdrM, tet(K) (13.3), fosB, dfrS1 (13.3) | sea (13.3), sec&sel (6.7), sek&seq (6.7), tst (13.3), egc (86.7) | ||

| 45 | CC45-MRSA-V (1) | t620 | I | 8 | B | AMP, TET | blaZ, sdrM, tet(K) | sec&sel, ACME, egc | |

| 59 | ST59/952-MRSA-V (9) | t437 | I | 8 | C | AMP, CAD (20), CHL (88.9), ERY (88.9), KAN (88.9), LIN (88.9), NEO (88.9), STR (80), TET (60) | blaZ (11.1), sdrM, tet(K) (66.7), aphA3&sat (88.9), erm(B) (88.9), cat-pC223 (88.9) | seb, sek&seq | |

| ST59-MRSA-IV (1) | t437 | I | 8 | A | AMP, ERY, KAN, LIN, NEO, STR | blaZ, sdrM, aphA3&sat, erm(B) | sea, seb, sek&seq | ||

| 80 | CC80/ST80-MRSA-IV (27) | t044 (21) | III | 8 | E | AMI (3.7), AMP, CAD (85.2), CHL (3.7), CIP (3.7), ERY (40.7), FUS (74.1), KAN, NEO, TET (77.8), TMP (3.7) | blaZ (77.8), sdrM, dfrS1 (3.7), tet(K) (70.4), aphA3&sat, fusB (77.8), erm(C) (40.7), tet(K) (70.4), cat-pC221 (3.7), dfrS1 (3.7) | etD, edinB | |

| t376 (5) | |||||||||

| t131 (1) | |||||||||

| 88 | CC88-MSSA (3) | t186 (2) t448 (1) | III | 8 | F | AMP, CAD (66.7), ERY (33.3), TET (66.7), TMP (33.3) | blaZ, sdrM, tet(K) (66.7), erm(C) (33.3), dfrS1 (33.3) | sek&seq (33.3), sep | |

| 93 | ST93-MRSA-IV (3) | t3949 (1) | III | 8 | B | AMP, CAD (66.7), ERY (33.3) | blaZ, sdrM, msr(A) (33.3), mph(C) (33.3), qacC (33.3) | CM14 | |

| t1819 (1) | |||||||||

| t202 (1) | |||||||||

| 121 | CC121-MSSA (7) | t159 (5), t435 (2) | IV | 8 | E | AMP, CAD (28.6) (I), CHL (14.3), ERY (57.1), LIN (14.3), STR (14.3), TET (28.6), TMP (28.6) | blaZ, sdrM, tet(K) (28.6), fosB, erm(C) (57.1), cat-pC221 (14.3), dfrS1 (28.6) | seb (57.1), egc, CM14 | |

| 152 | ST152-MRSA-V (1) | t355 | I | 5 | E | AMP, CAD, GEN, KAN, TOB | blaZ, sdrM, aacA-aphD | etD&edinB | |

| 154 | ST154-MRSA-IV (1) | t667 | III | 8 | Neg | AMP, CAD, CIP, SPC, TET | blaZ, sdrM, tet(M), cat-pMC524 | None detected | |

The StaphyType DNA microarray kit (Alere Technologies) was used for assigning the isolates to a multilocus sequence type (MLST) sequence type (ST) and/or a clonal complex (CC), a staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type (for MRSA only), accessory gene regulator (agr), capsule, and immune evasion complex (IEC) types. Forty-three MRSA isolates previously underwent MLST and SCCmec typing, namely, 18 ST772-MRSA-V, two ST22-MRSA-IV, 11 ST30-MRSA-IV, eight ST8-MRSA-IV, two ST80-MRSA-IV, one ST154-MRSA-IV, and one ST5-MRSA-IV isolates (30, 31).

The number of isolates (n) represented by each spa type or IEC type are indicated in parentheses only when more than one spa or IEC type was identified within a genotype.

Immune evasion complex (IEC) types were defined as described previously (59): A, sea, sak, chp, and scn; B, sak, chp, and scn; C, chp and scn; D, sea, sak, and scn; E, sak and scn; F. sep, sak, chp, and scn; novel, novel IEC type consisting of sak and sea (41); neg (negative), no IEC genes detected.

The susceptibility of each isolate to a panel of 23 antimicrobial agents was determined by disk diffusion, as described previously (30). The antimicrobial agents tested were amikacin (AMI), ampicillin (AMP), cadmium acetate (CAD), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ERY), ethidium bromide (ETBR), fusidic acid (FUS), gentamicin (GEN), kanamycin (KAN), lincomycin (LIN), mercuric chloride (MC), mupirocin (MUP), neomycin (NEO), phenyl mercuric acetate (PMA), rifampin, spectinomycin (SPC), streptomycin (STR), sulfonamide, tetracycline (TET), tobramycin (TOB), trimethoprim (TMP), and vancomycin. The ST8-MRSA-IV cfr-positive isolate M05/0060 was tested for linezolid resistance (LNZ), as described previously (42).

Excluding lukF-PV and lukS-PV, which were detected in all isolates.

Among the pvl-positive MSSA isolates, CC30 was the dominant clone, with 38.5% (15/39) of the isolates being assigned to this genotype (Table 2). CC22-MSSA accounted for 25.6% (10/39) of MSSA isolates, while CC121-MSSA, CC1-MSSA, and CC88-MSSA accounted for 18% (7/39), 10.3% (4/39), and 7.7% (3/39) of the isolates, respectively (Table 2).

Temporal changes in the predominant clonal types of pvl-positive MRSA.

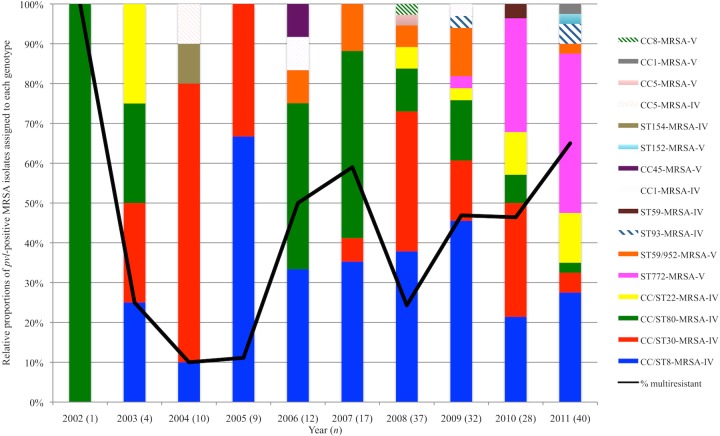

Fig. 1 shows the percentage of pvl-positive MRSA isolates assigned to each genotype for each year between 2002 and 2011. Ten of the genotypes identified between 2006 and 2011 were not identified between 2002 and 2005, including ST93-MRSA-IV, CC/ST59-MRSA-IV/V, and ST772-MRSA-V. The latter was identified for the first time in 2009, when it accounted for just 3.1% (1/32) of the isolates, but this increased to 28.6% (8/28) in 2010, and it was the predominant genotype in 2011, accounting for 40% (16/40) of pvl-positive MRSA isolates (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

The relative proportions of the 190 pvl-positive MRSA isolates identified by the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory between 2002 and 2011 assigned to each genotype each year during the study period and the annual percentage of these MRSA isolates that exhibited multiresistance during this time period (black line). Multiresistant MRSA isolates were defined as those exhibiting resistance to three of more classes of commonly used antimicrobial agents, including fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, macrolides/lincosamides, tetracyclines, fusidic acid, and mupirocin (22). Numbers in parentheses (n) indicate the numbers of pvl-positive MRSA isolates identified each year.

The CC/ST30-MRSA-IV clone predominated and was at its most prevalent in 2004, when it accounted for 70% of pvl-positive MRSA isolates (7/10). Subsequently, the prevalence of CC/ST30-MRSA-IV varied significantly each year between 2005 and 2011, accounting for 33.3% (3/9) of the isolates in 2005 but just 5% (2/40) of the isolates in 2011 (Fig. 1). The CC/ST8-MRSA-IV clone predominated and was at its most prevalent in 2005, when it accounted for 66.7% of the isolates (6/9); afterwards, however, the prevalence of this clone varied dramatically each year between 2006 and 2011, e.g., despite a decrease to 33.3% (4/12) in 2006, a rise in the prevalence of this clone was noted between 2006 and 2009 to 46.9% (15/32), followed by an overall decrease to 27.5% (11/40) in 2011 (Fig. 1).

Apart from 2002, when just one pvl-positive MRSA isolate was identified and was assigned to CC80/ST80-MRSA-IV, the highest prevalence of this clone was in 2007, when it accounted for 47.1% (8/17) of the isolates. Subsequently, the prevalence of this clone declined, and by 2011, it accounted for just 2.5% of the isolates (1/40) (Fig. 1).

Prior to 2008, only one pvl-positive ST22-MRSA-IV isolate had been detected (in 2003). Despite the low numbers of the isolates, an increase in the prevalence of pvl-positive ST22-MRSA-IV was noted between 2009 (3.1% [1/32]) and 2011 (12.5% [5/40]) (Fig. 1). The first ST59/952-MRSA-V isolates were detected in 2006, and a small number of the isolates of this clone were subsequently detected each year apart from 2010 (Fig. 1). The highest prevalence of this clone occurred in 2009 (12.5% [4/32]). Only three ST93-MRSA-IV isolates were identified, one in 2009 and two in 2011. All other clones were represented by one or two isolates only (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of pvl-positive S. aureus isolates.

The virulence and resistance gene profiles of the isolates identified within each genotype of pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA are shown in Table 2, and the main characteristics of the isolates within lineages, i.e., CCs, represented by more than one isolate, are described below.

CC1.

The majority of CC1/ST772-MRSA-V isolates exhibited spa type t657 (96% [24/25]), and all exhibited resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents, including ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim, erythromycin, and aminoglycosides, the latter two encoded by msr(A) and mph(C) and by aacA-aphD and aphA3, respectively. The enterotoxin genes sec&sel (“&” denotes linked genes) and egc, as well as the novel immune evasion complex (IEC) type consisting of scn and sea, were identified in all ST772-MRSA-V isolates (41).

The other CC1 genotypes identified (CC1-MRSA-IV, CC1-MRSA-V, and CC1-MSSA) exhibited different spa, agr, capsule, and IEC types from those of CC1/ST772-MRSA-V. The CC1-MRSA-V isolate also exhibited resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents and carried multiple resistance genes, but apart from aminoglycoside resistance encoded by aphA3 and aacA-aphD, these were different from those detected in CC1/ST772-MRSA-V and included tetracycline resistance encoded by tet(K) and tet(M) and fusidic acid resistance encoded by fusC. The two CC1-MRSA-IV isolates carried fewer resistance genes, with just one isolate carrying tet(K). The CC1-MRSA-IV/V isolates lacked egc, but various other enterotoxin genes were detected, including sea, sec&sel, sek&seq, and seh.

Of the four CC1-MSSA isolates identified, two exhibited the same spa type, t127, as the CC1-MRSA-V isolate. Multiple resistance genes were detected among these isolates, including aphA3, fusC, ileS2, and qacA, but for the latter two, phenotypic resistances to mupirocin and quaternary ammonium compounds were not detected. Toxin genes similar to those detected in CC1-MRSA were detected among the CC1-MSSA isolates, namely, sea, sek&seq, and seh. In fact, seh was unique to CC1 and was detected in all isolates except those belonging to ST772.

CC5.

The two CC5 MRSA isolates identified, one with SCCmec IV and the other with SCCmec V, exhibited the same spa, agr, capsule, and IEC types. Only the CC5-MRSA-V isolate carried dfrS1 and tet(K) and exhibited resistances to trimethoprim and tetracycline, respectively, and both isolates carried sea, egc, and the epidermolytic toxin gene edinA.

CC8.

Although 12 spa types were identified among the CC/ST8-MRSA-IV isolates, t008 predominated (73.4% [47/64]). The majority of CC/ST8-MRSA-IV isolates exhibited resistances to kanamycin and neomycin encoded by aphA3 and to erythromycin encoded by msr(A), and almost half of the isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin. Slightly <10% of the CC/ST8-MRSA-IV isolates were tetracycline resistant and carried tet(K). One isolate carried cfr and fexA and exhibited chloramphenicol and linezolid resistances (42). The majority of the isolates carried the enterotoxin genes sek and seq and the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME), and although they were less common, sed, sej, and ser were also identified.

The one remaining CC8-MRSA t008 isolate harbored SCCmec V and did not exhibit resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents or harbor multiple resistance genes, but sek&seq and ACME were detected. ACME was only identified in one non-CC/ST8-MRSA isolate (CC45-MRSA-V).

CC22.

The spa types t852 and t005 predominated among the CC22 MRSA (58.3% [7/12]) and MSSA (70% [7/10]) isolates, respectively. Only one spa type, t005, was common to CC22 MRSA and MSSA, but only one t005 MRSA isolate was identified. Among the CC22-MRSA-IV isolates, resistances to aminoglycosides encoded by aacA-aphD and aadD, trimethoprim encoded by dfrS1, erythromycin encoded by erm(C), and ciprofloxacin were common. No ciprofloxacin-resistant CC22 MSSA isolates were identified, but they all exhibited aminoglycoside resistance encoded by aacA-aphD; the majority were resistant to trimethoprim and carried dfrS1, and one isolate exhibited resistance to fusidic acid, which was probably due to mutations in fusA, as neither fusB or fusC were detected. However, not all CC22 isolates harboring aacA-aphD and aadD exhibited resistance to all of the appropriate aminoglycoside antimicrobial agents. All CC22 isolates carried egc, but no other toxin genes were detected.

CC30.

The majority of CC/ST30-MRSA-IV isolates were assigned to spa type t019 (55% [22/40]) or t012 (30% [12/40]). Fewer than half of the isolates were resistant to fusidic acid encoded by fusC, and resistances to tetracycline and trimethoprim encoded by tet(K) and dfrS1, respectively, were detected in one isolate each. All CC/ST30-MRSA-IV isolates carried egc, and 35% (14/40) carried the toxic shock toxin gene tst, with only two isolates harboring sea.

Among the CC30 MSSA spa types, t021 (40% [6/15]) and t318 (26.7% [4/15]) predominated. The latter spa type (t318) was the only common spa type detected among CC30 MRSA and MSSA but was only detected in one CC30-MRSA isolate. While no fusidic acid resistance phenotype or genes were detected among the CC30-MSSA, resistances to tetracycline, trimethoprim, and erythromycin encoded by tet(K), dfrS1, and mph(C), respectively, were identified in one or two isolates each. CC30-MSSA isolates carried the greatest range of toxin genes, i.e., the enterotoxin genes sek&seq, egc, sea, sec&sel, and tst, but apart from egc, which was detected in the majority of CC30 MSSA, each of these were found in one or two CC30-MSSA isolates only. Overall, tst was unique to CC30 isolates.

CC59.

All ST59/952-MRSA-V isolates exhibited a single spa type, t437, and the majority of the isolates exhibited resistances to multiple antimicrobial agents and carried multiple resistance genes, with erythromycin and lincomycin resistances encoded by erm(B), kanamycin and neomycin resistances encoded by aphA3, and chloramphenicol resistance encoded by cat-pC223. Tetracycline resistance encoded by tet(K) was also common among these isolates. All ST59/952-MRSA-V isolates carried the enterotoxin genes seb and sek&seq.

The one ST59-MRSA-IV isolate identified carried fewer resistance genes, but aphA3 and erm(B) encoding resistances to aminoglycosides and erythromycin, respectively, were detected. Similar to the ST59/952-MRSA-V isolates, the ST59-MRSA-IV isolate carried seb and sek&seq, but sea was also detected.

CC80.

The majority of the CC/ST80-MRSA-IV isolates exhibited spa type t044 (77.8% [21/27]). All isolates exhibited resistances to kanamycin and neomycin, encoded by aphA3. Resistances to tetracycline, fusidic acid, and erythromycin encoded by tet(K), fusB, and erm(C), respectively, were also common. However, for a small number of the isolates, tet(K) and fusB were identified but the appropriate resistance phenotype was not detected. Chloramphenicol and trimethoprim resistances encoded by cat-pC221 and dfrS1, respectively, as well as ciprofloxacin resistance, were detected in only one isolate each. All CC/ST80-MRSA-IV isolates harbored the exfoliative toxin gene etD and the epidermolytic toxin gene edinB, which were identified in only one other isolate (ST152-MRSA-V).

CC88.

Only three CC88 isolates, all MSSA, were identified and were assigned to two spa types. These isolates were the only isolates found to harbor IEC type F (sep, sak, chp, and scn). Two isolates exhibited tetracycline resistance and carried tet(K), with only one isolate each exhibiting resistances to erythromycin and trimethoprim, encoded by erm(C) and dfrS1, respectively. The enterotoxin genes sek&seq were detected in one CC88-MSSA isolate.

ST93.

The three ST93-MRSA-IV isolates each exhibited a different spa type. Erythromycin resistance encoded by msr(A) and mph(C) was detected in one isolate only. The qacC gene was also detected in one isolate but the isolate did not exhibit resistance to ethidium bromide. The enterotoxin gene homolog CM14 was the only toxin gene detected among ST93-MRSA-IV isolates.

CC121.

All CC121 isolates identified were MSSA, and the majority exhibited spa type t159 (71.4% [5/7]). Only CC121-MSSA isolates exhibited agr type IV. Just over half of the isolates exhibited erythromycin resistance encoded by erm(C), and tetracycline, trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol resistances encoded by tet(K), dfrS1, and cat-pC221, respectively, were also detected among CC121-MSSA. All CC121-MSSA isolates harbored egc and CM14, and just over half also carried seb.

Multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA.

Multiresistance was identified among MRSA isolates only and was defined as phenotypic resistance to three or more classes of commonly used antimicrobial agents tested, including fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin), aminoglycosides (gentamicin/kanamycin/neomycin/tobramycin), macrolides/lincosamides (erythromycin/lincomycin), tetracyclines, fusidic acid, and mupirocin (22). Using this criterion, 43.7% (83/190) of pvl-positive MRSA isolates were multiresistant. These multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA isolates were assigned to six genotypes, with the majority belonging to CC/ST8-MRSA-IV (30.1% [25/83]), ST772-MRSA-V (30.1% [25/83]), and CC/ST80-MRSA-IV (25.3% [21/83]), with a small number of multiresistant isolates also belonging to CC/ST22-MRSA-IV (7.2% [6/83]), ST59/952-MRSA-V (6% [5/83]), and CC1-MRSA-V (1.2% [1/83]) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). An increase in the prevalence of multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA was observed between 2004 (10% [1/10]) and 2007 (59% [10/17]) (P < 0.02), and despite a decline in 2008 (24.3% [9/37]), this prevalence increased again between 2008 and 2011 to 65% (26/40) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). In fact, the highest prevalence of multiresistance among pvl-positive MRSA isolates was observed in 2011, and this was predominantly associated with isolates within ST772-MRSA-V (61.5% [16/26]) and to a lesser extent, CC/ST8-MRSA-IV (19.2% [5/26]), CC/ST22-MRSA-IV (11.5% [3/26]), ST59-MRSA-V (3.8% [1/26]), and CC1-MRSA-V (3.8% [1/26]).

Patient demographics.

Of the 229 isolates investigated, 216 (94.3%) were from patients, nine (3.9%) from health care staff, and four (1.8%) from environmental sources. Information pertaining to whether the S. aureus isolates were from patients based in the community or in hospitals were available for 175/216 isolates, 69.7% (122/175) of whom were based in the community.

Sex and age.

Gender data were available for patients, from whom 189 isolates were recovered, of which 52.4% (99/189) were from females (Table 3). There was no significant difference between the genders of patients associated with pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA isolates, with 52.2% (83/159) and 47.8% (76/159) of MRSA isolates being associated with females and males, respectively, and 53.3% (16/30) and 46.7% (14/30) of MSSA isolates being associated with females and males, respectively. The ages of patients from whom pvl-positive S. aureus isolates were recovered ranged from <1 month to 98 years, and the median age was 30 years (age data were available for 193 patients). Seventy percent (136/193) of the isolates were from patients who were <40 years of age (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Patient demographics associated with pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA identified by the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory between 2002 and 2011

| Patient characteristics | No. of isolates | Genotypea |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 90 | NA |

| Female | 99 | NA |

| Data not available | 36 | NA |

| Age group (yr) | ||

| 0–9 | 35 | NA |

| 10–19 | 19 | NA |

| 20–29 | 40 | NA |

| 30–39 | 42 | NA |

| 40–49 | 23 | NA |

| 50–59 | 11 | NA |

| 60–69 | 9 | NA |

| 70–79 | 7 | NA |

| 80–89 | 4 | NA |

| 90–99 | 3 | NA |

| Data not available | 32 | NA |

| No. of clustersb | ||

| 1 (household) | 4 | CC/ST30-MRSA-IV |

| 2 (household) | 3 | CC/ST30-MRSA-IV |

| 3 (household) | 4 | CC/ST8-MRSA-IV |

| 4 (household) | 3 | CC/ST8-MRSA-IV |

| 5 (household) | 4 | CC80-MRSA-IV |

| 6 (hospital) | 6 | ST772-MRSA-V |

| 7 (hospital and household)c | 11 | ST772-MRSA-V |

| International travel to or country/region of origin | ||

| United States | 1 | CC1-MRSA-IV |

| 3 | ST8-MRSA-IV | |

| Africa | 1 | ST8-MRSA-IV |

| 1 | CC5-MRSA-IV | |

| 2 | ST30-MRSA-IV | |

| 1 | CC121-MSSA | |

| 1 | CC5-MRSA-V | |

| The Middle East | 1 | ST80-MRSA-IV |

| India | 1 | ST772-MRSA-V |

| 5 | ST772-MRSA-V | |

| Far East Asia | 1 | ST80-MRSA-IV |

| 1 | ST154-MRSA-IV | |

| 3 | ST30-MRSA-IV | |

| 1 | CC121-MSSA | |

| 1 | ST59-MRSA-V | |

| 1 | ST8-MRSA-IV | |

| Australia | 1 | CC22-MRSA-IV |

| 1 | ST93-MRSA-IV | |

| New Zealand | 1 | ST8-MRSA-IV |

| Brazil | 1 | ST8-MRSA-IV |

| Czech Republic | 1 | CC1-MRSA-IV |

| Undefined (outside of Ireland) | 2 | ST59/952-MRSA-V |

| 1 | ST22-MRSA-IV | |

| 1 | CC22-MSSA | |

| 1 | CC30-MSSA |

NA, not applicable; CC, clonal complex; ST, sequence type.

Isolates were defined as clusters if they were recovered from members of one family/household, within a hospital, or both. Within each cluster, isolates were recovered between 3 months and 2 years apart. Each isolate within a cluster was recovered from a different person or environmental source.

The 11 pvl-positive ST772-MRSA-V isolates in cluster 7 were described previously (31).

Isolate clusters.

No clusters were identified among pvl-positive MSSA isolates, but seven isolate clusters were identified among pvl-positive MRSA isolates, either from two or more members of one family/household, within a hospital, or both (Table 3). Within each cluster, the isolates were recovered between 3 months and 2 years apart, and the isolates were represented by a single genotype, with indistinguishable spa and DNA microarray profiles in each case. ST772-MRSA-V accounted for almost half of all cluster-associated isolates identified (48.6% [17/35]) (Table 3).

International travel or country of origin outside of Ireland.

Thirty-five individuals from whom pvl-positive isolates were recovered were known to have recently traveled internationally or had a country of origin other than Ireland (Table 3). Recent travel ranged from 2 weeks to 1 year prior to the recovery of the pvl-positive S. aureus isolates, but for the majority of patients, the time period since travel was not defined. The genotypes most commonly associated with international travel or country of origin other than Ireland were ST8-MRSA-IV (seven isolates), ST772-MRSA-V (six isolates), and ST30-MRSA-IV (five isolates) (Table 3). The ST8-MRSA-IV and ST30-MRSA-IV isolates were identified from patients with links to multiple regions worldwide, while the ST772-MRSA-V isolates were associated exclusively with India (Table 3).

Overall, the most common travel destination or region of origin for patients with pvl-positive S. aureus was Asia (15 isolates), followed by Africa (six isolates) and the United States (4 isolates) (Table 3).

Clinical presentations.

Clinical data were available for 159 isolates (135 MRSA and 24 MSSA) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The most common infections were SSTIs (60.4% [96/159]), including unspecified SSTIs, abscesses, boils, furuncles, bursitis, folliculitis, sinusitis, eye and ear infections, inguinal lymphadenitis, and wound infections. SSTIs were associated with isolates from all except three genotypes: CC1-MSSA (n = 4), ST152-MRSA-V (n = 1), and ST59-MRSA-IV (n = 1). More serious manifestations were also identified, including BSIs (10.7% [17/159] of the isolates including ST59-MRSA-IV, ST59/952-MRSA-V, ST30-MRSA-IV, ST22-MRSA-IV, ST8-MRSA-IV, CC1-MRSA-IV, ST772-MRSA-V, and CC30-MSSA), pneumonia (3.1% [5/159] of the isolates including CC30-MSSA, ST772-MRSA-V, CC/ST8-MRSA-IV, and CC/ST80-MRSA-IV), osteomyelitis (1.3% [2/159] of the isolates including CC121-MSSA and CC1-MSSA), necrotizing pneumonia (1.3% [2/159] of the isolates belonging to CC/ST8-MRSA-IV and CC1 MSSA), necrotizing fasciitis (0.6% [1/159] of the isolates belonging to CC30-MSSA), and endocarditis (0.6% [1/159] isolates belonging to CC22/ST22-MRSA-IV). Thirty-one isolates were recovered during patient screenings (nose, throat, and/or perineum sites) during hospital outbreaks or from persons with close contact with patients with pvl-positive S. aureus.

DISCUSSION

This study reports several novel findings in relation to pvl-positive MRSA, including an increase in the prevalence and diversity of pvl-positive MRSA isolates submitted to the NMRSARL between 2002 and 2011 and several temporal shifts in the predominant clonal types. A 44-fold increase in the prevalence of pvl-positive MRSA, from 0.2% to 8.8%, was observed between 2002 and 2011 (Fig. 1). While these findings may reflect a true increase in the prevalence of pvl-positive MRSA in Ireland over the last decade, enhanced clinical and laboratory awareness of pvl probably also contributed to the higher rate. A relatively low but increasing prevalence of pvl-positive MRSA has also been reported from Austria and Germany during the last decade (43, 44).

The polyclonal pvl-positive MRSA population structure identified in Ireland and in other European countries (21, 22, 43, 45) contrasts starkly with that in the United States and Australia, where single epidemic pvl-positive clones predominate, specifically ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300 and ST93-MRSA-IV, respectively (17, 46). Many reasons have been proposed for this difference between the United States and Europe, including environmental, host, social, economic, and cultural factors (2, 21). However, direct evidence for these is somewhat lacking, and many of the risk factors identified for pvl-positive MRSA/CA-MRSA in the United States may also apply to various communities in Europe (2). In the present study, while such specific parameters were not investigated, six familial/household outbreaks of pvl-positive MRSA were identified. Furthermore, links between several pvl-positive S. aureus isolates and patients with recent foreign travel to or ethnic origin from outside of Ireland were also identified, highlighting the continuing role of strain importation on the variety of pvl-positive MRSA strains found in Ireland.

While the prevalence of different pvl-positive MRSA clones identified in the present study, together with precise temporal shifts of predominant clones that are unique to Ireland, similarities and differences were noted in comparison with polyclonal pvl-positive MRSA populations observed in other European countries. For example, a decline in the incidence of the pvl-positive European clone ST80-MRSA-IV has been noted recently across Europe in association with an increase in ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300 (21). In the present study, an increase in the prevalence of ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300 was observed between 2006 and 2009, and it predominated in 2008 and 2009, decreased in 2010, and was the second most common clone in 2011, surpassed only by ST772-MRSA-V. The emergence of ST772-MRSA-V as the dominant pvl-positive MRSA clone in 2011 in Ireland reflects a similar situation in the United Kingdom, where ST772-MRSA-V was the predominant multiresistant pvl-positive clone between 2005 and 2008 (22). The predominance of ST772-MRSA-V and ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300 in the pvl-positive MRSA isolates in Ireland is of concern, as both clones appear to be highly transmissible, with a propensity to spread worldwide and displace hospital strains (14, 20). In the present study, ST772-MRSA-V was found in association with two separate hospital clusters and one familial cluster, and ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300 was found in association with three family clusters; both of these strains were found to have been imported frequently into Ireland. In addition, genetic characteristics that may enhance the virulence or ability of these clones to spread have been identified in this and other studies, including ACME and the enterotoxin genes sek&seq in ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300 and an sea- and pvl-encoding bacteriophage (41), and also multiple other enterotoxin genes in ST772-MRSA-V (Table 2). Lastly, isolates belonging to both clones can exhibit multiresistance (22), and all ST772-MRSA-V and 38.5% of ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300 isolates investigated in this study were multiresistant.

While the overall numbers of pvl-positive ST22-MRSA-IV isolates in this study were low, a 4-fold increase was noted between 2009 and 2011 (Fig. 1). Worryingly, pvl-positive ST22-MRSA-IV has been associated with hospital and community outbreaks elsewhere (47–49), and it now predominates together with ST772-MRSA-V in hospitals in India (20). Although pvl-negative ST22-MRSA-IV is currently predominant in Irish hospitals (mainly spa type t032 [28]), pvl-positive ST22-MRSA-IV was genetically distinct (spa type t852) in the present study, indicating the independent evolution of these strains.

CC/ST30-MRSA-IV was the second most common pvl-positive MRSA clone identified, accounting for 21.1% of all isolates during the study period and predominating several times across the duration of the study (Fig. 1). Isolates of this pandemic clone are also common in the United Kingdom and have been associated with a hospital outbreak in which the probable index case was a staff member who had recently traveled to the Philippines (24, 50, 51). In the present study, a link between travel to or ethnic origin in Asia or Africa was identified for several CC/ST30-MRSA-IV isolates, emphasizing the role of travel in its spread. CC/ST30-MRSA-IV isolates were also associated with two familial outbreaks, indicating further its propensity to spread. In the present study, the prevalence of CC/ST30-MRSA-IV declined from 70% to 0% between 2004 and 2006 and from 28.6% to 5% between 2010 and 2011 (Fig. 1). A decline in the prevalence of this once-predominant clone among CA-MRSA was also recently reported in New Zealand, where it was replaced by pvl-negative ST5-MRSA-IV (52). It is now well established that not all CA-MRSA isolates carry pvl. In the present study, 70% of pvl-positive S. aureus isolates for which information was available were from patients in the community, indicating that CA S. aureus had emerged as a significant problem in Ireland. However, the true burden of CA S. aureus infections in Ireland will only be fully understood when pvl-negative and pvl-positive CA S. aureus isolates are investigated systematically together with detailed epidemiological information.

The diversity of pvl-positive MRSA clones increased in the second half of the study period, with 10/16 MRSA genotypes identified for the first time between 2006 and 2011, including CC/ST59-MRSA-V, ST93-MRSA-IV, and ST772-MRSA-V. Links between several isolates of these clones and the regions where they predominated were also noted. Although an increase in the Taiwanese clone (CC/ST59-MRSA-V), from 8.3% in 2006 to 12.5% in 2009, was observed, the number of isolates recovered each year remained low throughout (between one and four isolates each year). CC/ST59-MRSA-V is among the predominant CA-MRSA clones in some northern European countries (21). In contrast, similar to in the present study, ST93-MRSA-IV has only been reported sporadically in Europe (21, 53) but is the dominant pvl-positive MRSA strain in Australia, where it has spread into health care facilities (54). Increasing reports of outbreaks of pvl-positive MRSA, particularly in NICUs, highlights the ability of these strains to spread among vulnerable patient groups in hospitals (24, 25, 47, 48). In the present study, two NICU clusters in separate hospitals were due to the recently emerged pvl-positive multiresistant ST772-MRSA-V clone. In fact, 30% of pvl-positive isolates for which information was available were from patients in hospitals, a situation that requires close monitoring so that pvl-positive MRSA does not become widespread in Irish hospitals.

Despite a decrease in 2008, an overall 6-fold increase in the prevalence of multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA was identified between 2004 and 2011 (Fig. 1). Similarly, a 12.3-fold increase in the prevalence of multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA was noted in the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2008 (22). Both in Ireland and the United Kingdom, this was largely due to the emergence and predominance of ST772-MRSA-V, and in Ireland only, to the continued prevalence of ST8-MRSA-IV/USA300. Also of concern is the high prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance identified among multiresistant pvl-positive MRSA isolates (67.1%). All of these findings highlight how non-multiantibiotic resistance and susceptibility to ciprofloxacin can no longer be considered to be reliable markers for pvl-positive MRSA.

This study has for the first time provided important insights into the molecular epidemiology of pvl-positive MSSA in Ireland. The prevalence of pvl-positive MSSA decreased 8-fold, from 20% in 2004 to 2.5% in 2011, and it accounted for only 17% of all pvl-positive isolates identified during the study period. In contrast, in the United Kingdom, the prevalence of pvl-positive MSSA increased 9-fold between 2005 and 2010, accounting for 61.5% of all pvl-positive S. aureus in 2009 (26); in Africa, pvl-positive MSSA is also common, with 57% of MSSA isolates in one study being identified as pvl positive (27). However, MSSA isolates are not routinely referred to the Irish NMRSARL, and the number of MSSA isolates referred each year during our study was low (Table 1). Additional studies are required in order to determine the true burden of pvl-positive MSSA in Ireland.

The results of this study also suggest that the importation of pvl-positive MRSA strains is more significant than the local emergence of pvl-positive MRSA from pvl-positive MSSA, with only 1.6% (3/189) of the MRSA isolates exhibiting the same spa type as the MSSA isolates. Due to the greater abundance of these spa types among pvl-positive MSSA, it is reasonable to speculate that this small number of pvl-positive MRSA isolates may have evolved from the pvl-positive MSSA isolates by the acquisition of SCCmec rather than the loss of SCCmec by MRSA, although both alternatives are possible.

Similar to a recent study in the United Kingdom, CC22 and CC30 were the most common pvl-positive MSSA clones identified in our study, accounting for 64.1% of the isolates (26). While not reported previously in the United Kingdom (26), the CC121-MSSA clone that accounted for 17.9% of pvl-positive MSSA isolates in the present study is a pandemic clone (55, 56). Interestingly, a link to Africa and the Far East was noted for 2/7 CC121 MSSA isolates, where that clone has been shown to dominate (56, 57). CC88-MSSA accounted for just 7.6% of the pvl-positive MSSA isolates and was reported previously in India (58), but isolates of this lineage are more commonly reported as MRSA with SCCmec IV, particularly in Africa (19).

In conclusion, while this study highlights the changing molecular epidemiology of pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA in Ireland over the last decade, it is clear that the actual burden of pvl-positive and CA S. aureus infections in Ireland may be even higher, since this study investigated only pvl-positive isolates and only those submitted to the NMRSARL. There is a need for ongoing and systematic surveillance of pvl-positive and CA S. aureus infections in communities and hospitals in Ireland, together with obtaining detailed epidemiological information, in order to fully understand the burden of S. aureus infections that exists.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Microbiology Research Unit, Dublin Dental University Hospital (DDUH).

We thank the staff of the Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory, past and present, particularly Angela Rossney, for their support and collaboration in investigating pvl-positive MRSA and MSSA. We thank Brenda McManus, DDUH, for designing the primers for antimicrobial resistance gene detection.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 December 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02799-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monecke S, Coombs G, Shore AC, Coleman DC, Akpaka P, Borg M, Chow H, Ip M, Jatzwauk L, Jonas D, Kadlec K, Kearns A, Laurent F, O'Brien FG, Pearson J, Ruppelt A, Schwarz S, Scicluna E, Slickers P, Tan HL, Weber S, Ehricht R. 2011. A field guide to pandemic, epidemic and sporadic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 6:e17936. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witte W. 2009. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: what do we need to know? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:17–25. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandenesch F, Naimi T, Enright MC, Lina G, Nimmo GR, Heffernan H, Liassine N, Bes M, Greenland T, Reverdy ME, Etienne J. 2003. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:978–984. 10.3201/eid0908.030089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lina G, Piémont Y, Godail-Gamot F, Bes M, Peter MO, Gauduchon V, Vandenesch F, Etienne J. 1999. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1128–1132. 10.1086/313461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillet Y, Issartel B, Vanhems P, Fournet JC, Lina G, Bes M, Vandenesch F, Piémont Y, Brousse N, Floret D, Etienne J. 2002. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet 359:753–759. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07877-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis JS, Doherty MC, Lopatin U, Johnston CP, Sinha G, Ross T, Cai M, Hansel NN, Perl T, Ticehurst JR, Carroll K, Thomas DL, Nuermberger E, Bartlett JG. 2005. Severe community-onset pneumonia in healthy adults caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying the Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:100–107. 10.1086/427148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS. 2007. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the role of Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Lab. Invest. 87:3–9. 10.1038/labinvest.3700501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaneko J, Kamio Y. 2004. Bacterial two-component and hetero-heptameric pore-forming cytolytic toxins: structures, pore-forming mechanism, and organization of the genes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68:981–1003. 10.1271/bbb.68.981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boakes E, Kearns AM, Ganner M, Perry C, Hill RL, Ellington MJ. 2011. Distinct bacteriophages encoding Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) among international methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones harboring PVL. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:684–692. 10.1128/JCM.01917-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson DA, Kearns AM, Holmes A, Morrison D, Grundmann H, Edwards G, O'Brien FG, Tenover FC, McDougal LK, Monk AB, Enright MC. 2005. Re-emergence of early pandemic Staphylococcus aureus as a community-acquired meticillin-resistant clone. Lancet 365:1256–1258. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74814-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groom AV, Wolsey DH, Naimi TS, Smith K, Johnson S, Boxrud D, Moore KA, Cheek JE. 2001. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a rural American Indian community. JAMA 286:1201–1205. 10.1001/jama.286.10.1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otto M. 2013. Community-associated MRSA: what makes them special? Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303:324–330. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyle-Vavra S, Ereshefsky B, Wang CC, Daum RS. 2005. Successful multiresistant community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineage from Taipei, Taiwan, that carries either the novel staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec (SCCmec) type VT or SCCmec type IV. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4719–4730. 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4719-4730.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Hara FP, Amrine-Madsen H, Mera RM, Brown ML, Close NM, Suaya JA, Acosta CJ. 2012. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus in the United States 2004–2008 reveals the rapid expansion of USA300 among inpatients and outpatients. Microb. Drug Resist. 18:555–561. 10.1089/mdr.2012.0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CJ, Unger C, Hoffmann W, Lindsay JA, Huang YC, Götz F. 2013. Characterization and comparison of 2 distinct epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones of ST59 lineage. PLoS One 8:e63210. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JM, Cook GM. 2005. A decade of community MRSA in New Zealand. Epidemiol. Infect. 133:899–904. 10.1017/S0950268805004024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coombs GW, Goering RV, Chua KY, Monecke S, Howden BP, Stinear TP, Ehricht R, O'Brien FG, Christiansen KJ. 2012. The molecular epidemiology of the highly virulent ST93 Australian community Staphylococcus aureus strain. PLoS One 7:e43037. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otter JA, French GL. 2010. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:227–239. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70053-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghebremedhin B, Olugbosi MO, Raji AM, Layer F, Bakare RA, König B, König W. 2009. Emergence of a community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain with a unique resistance profile in southwest Nigeria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2975–2980. 10.1128/JCM.00648-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Souza N, Rodrigues C, Mehta A. 2010. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with emergence of epidemic clones of sequence type (ST) 22 and ST 772 in Mumbai, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1806–1811. 10.1128/JCM.01867-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rolo J, Miragaia M, Turlej-Rogacka A, Empel J, Bouchami O, Faria NA, Tavares A, Hryniewicz W, Fluit AC, de Lencastre H, CONCORD Working Group 2012. High genetic diversity among community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in Europe: results from a multicenter study. PLoS One 7:e34768. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellington MJ, Ganner M, Warner M, Cookson BD, Kearns AM. 2010. Polyclonal multiply antibiotic-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with Panton-Valentine leucocidin in England. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:46–50. 10.1093/jac/dkp386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel M, Thomas HC, Room J, Wilson Y, Kearns A, Gray J. 2013. Successful control of nosocomial transmission of the USA300 clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a UK paediatric burns centre. J. Hosp. Infect. 84:319–322. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali H, Nash JQ, Kearns AM, Pichon B, Vasu V, Nixon Z, Burgess A, Weston D, Sedgwick J, Ashford G, Mühlschlegel FA. 2012. Outbreak of a South West Pacific clone Panton-Valentine leucocidin-positive meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in a UK neonatal intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 80:293–298. 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlebusch S, Price GR, Hinds S, Nourse C, Schooneveldt JM, Tilse MH, Liley HG, Wallis T, Bowling F, Venter D, Nimmo GR. 2010. First outbreak of PVL-positive nonmultiresistant MRSA in a neonatal ICU in Australia: comparison of MALDI-TOF and SNP-plus-binary gene typing. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:1311–1314. 10.1007/s10096-010-0995-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otokunefor K, Sloan T, Kearns AM, James R. 2012. Molecular characterization and Panton-Valentine leucocidin typing of community-acquired methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3069–3072. 10.1128/JCM.00602-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breurec S, Fall C, Pouillot R, Boisier P, Brisse S, Diene-Sarr F, Djibo S, Etienne J, Fonkoua MC, Perrier-Gros-Claude JD, Ramarokoto CE, Randrianirina F, Thiberge JM, Zriouil SB, Working Group on Staphylococcus aureus Infections, Garin B, Laurent F 2011. Epidemiology of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus lineages in five major African towns: high prevalence of Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:633–639. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shore AC, Rossney AS, Kinnevey PM, Brennan OM, Creamer E, Sherlock O, Dolan A, Cunney R, Sullivan DJ, Goering RV, Humphreys H, Coleman DC. 2010. Enhanced discrimination of highly clonal ST22-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus IV isolates achieved by combining spa, dru, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1839–1852. 10.1128/JCM.02155-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irish National MRSA Reference Laboratory 2011. National MRSA Reference Laboratory annual report. St. James's Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. http://www.stjames.ie/Departments/DepartmentsA-Z/N/NationalMRSAReferenceLaboratory/DepartmentinDepth/NMRSARL%20Annual%20Report%202011.pdf

- 30.Rossney AS, Shore AC, Morgan PM, Fitzgibbon MM, O'Connell B, Coleman DC. 2007. The emergence and importation of diverse genotypes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) harboring the Panton-Valentine leukocidin gene (pvl) reveal that pvl is a poor marker for community-acquired MRSA strains in Ireland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2554–2563. 10.1128/JCM.00245-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brennan GI, Shore AC, Corcoran S, Tecklenborg S, Coleman DC, O'Connell B. 2012. Emergence of hospital- and community-associated Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotype ST772-MRSA-V in Ireland and detailed investigation of an ST772-MRSA-V cluster in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:841–847. 10.1128/JCM.06354-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heelan K, Murphy A, Murphy LA. 2012. Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcal aureus: report of four siblings. Pediatr. Dermatol. 29:618–620. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shore AC, Brennan OM, Deasy EC, Rossney AS, Kinnevey PM, Ehricht R, Monecke S, Coleman DC. 2012. DNA microarray profiling of a diverse collection of nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates assigns the majority to the correct sequence type and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type and results in the subsequent identification and characterization of novel SCCmec-SCCM1 composite islands. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:5340–5355. 10.1128/AAC.01247-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monecke S, Jatzwauk L, Weber S, Slickers P, Ehricht R. 2008. DNA microarray-based genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from Eastern Saxony. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14:534–545. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monecke S, Slickers P, Ehricht R. 2008. Assignment of Staphylococcus aureus isolates to clonal complexes based on microarray analysis and pattern recognition. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 53:237–251. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDougal LK, Fosheim GE, Nicholson A, Bulens SN, Limbago BM, Shearer JE, Summers AO, Patel JB. 2010. Emergence of resistance among USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing invasive disease in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3804–3811. 10.1128/AAC.00351-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanhoof R, Godard C, Content J, Nyssen HJ, Hannecart-Pokorni E. 1994. Detection by polymerase chain reaction of genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates of epidemic phage types. Belgian Study Group of Hospital Infections (GDEPIH/GOSPIZ). J. Med. Microbiol. 41:282–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen CM, Huang M, Chen HF, Ke SC, Li CR, Wang JH, Wu LT. 2011. Fusidic acid resistance among clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Taiwanese hospital. BMC Microbiol. 11:98. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Argudin MA, Mendoza MC, González-Hevia MA, Bances M, Guerra B, Rodicio MR. 2012. Genotypes, exotoxin gene content, and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus strains recovered from foods and food handlers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:2930–2935. 10.1128/AEM.07487-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith K, Gemmell CG, Hunter IS. 2008. The association between biocide tolerance and the presence or absence of qac genes among hospital-acquired and community-acquired MRSA isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:78–84. 10.1093/jac/dkm395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prabhakara S, Khedkar S, Shambat SM, Srinivasan R, Basu A, Norrby-Teglund A, Seshasayee AS, Arakere G. 2013. Genome sequencing unveils a novel sea enterotoxin-carrying PVL phage in Staphylococcus aureus ST772 from India. PLoS One 8:e60013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shore AC, Brennan OM, Ehricht R, Monecke S, Schwarz S, Slickers P, Coleman DC. 2010. Identification and characterization of the multidrug resistance gene cfr in a Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive sequence type 8 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus IVa (USA300) isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4978–4984. 10.1128/AAC.01113-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berktold M, Grif K, Mäser M, Witte W, Würzner R, Orth-Höller D. 2012. Genetic characterization of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Western Austria. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 124:709–715. 10.1007/s00508-012-0244-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witte W, Strommenger B, Cuny C, Heuck D, Nuebel U. 2007. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the Panton-Valentine leucocidin gene in Germany in 2005 and 2006. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:1258–1263. 10.1093/jac/dkm384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brauner J, Hallin M, Deplano A, De Mendonça R, Nonhoff C, De Ryck R, Roisin S, Struelens MJ, Denis O. 2013. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones circulating in Belgium from 2005 to 2009: changing epidemiology. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32:613–620. 10.1007/s10096-012-1784-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tenover FC, McDougal LK, Goering RV, Killgore G, Projan SJ, Patel JB, Dunman PM. 2006. Characterization of a strain of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus widely disseminated in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:108–118. 10.1128/JCM.44.1.108-118.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinto AN, Seth R, Zhou F, Tallon J, Dempsey K, Tracy M, Gilbert GL, O'Sullivan MV. 2012. Emergence and control of an outbreak of infections due to Panton-Valentine leukocidin positive, ST22 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a neonatal intensive care unit. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19:620–627. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris SR, Cartwright EJ, Török ME, Holden MTG, Brown NM, Ogilvy-Stuart AL, Ellington MJ, Quail MA, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Peacock SJ. 2012. Whole-genome sequencing for analysis of an outbreak of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13:130–136. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70268-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto T, Takano T, Yabe S, Higuchi W, Iwao Y, Isobe H, Ozaki K, Takano M, Reva I, Nishiyama A. 2012. Super-sticky familial infections caused by Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive ST22 community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 18:187–198. 10.1007/s10156-011-0316-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellington MJ, Perry C, Ganner M, Warner M, McCormick Smith I, Hill RL, Shallcross L, Sabersheikh S, Holmes A, Cookson BD, Kearns AM. 2009. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of ciprofloxacin-susceptible MRSA encoding PVL in England and Wales. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:1113–1121. 10.1007/s10096-009-0757-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pantelides NM, Gopal Rao G, Charlett A, Kearns AM. 2012. Preadmission screening of adults highlights previously unrecognized carriage of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in London: a cause for concern? J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3168–3171. 10.1128/JCM.01066-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williamson DA, Roberts SA, Ritchie SR, Coombs GW, Fraser JD, Heffernan H. 2013. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in New Zealand: rapid emergence of sequence type 5 (ST5)-SCCmec-IV as the dominant community-associated MRSA clone. PLoS One 8:e62020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ellington MJ, Ganner M, Warner M, Boakes E, Cookson BD, Hill RL, Kearns AM. 2010. First international spread and dissemination of the virulent Queensland community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1009–1012. 10.1111/j.1469-0691-2009.02994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Munckhof WJ, Nimmo GR, Carney J, Schooneveldt JM, Huygens F, Inman-Bamber J, Tong E, Morton A, Giffard P. 2008. Methicillin-susceptible, non-multiresistant methicillin-resistant and multiresistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a clinical, epidemiological and microbiological comparative study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:355–364. 10.1007/s10096-007-0449-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monecke S, Slickers P, Ellington MJ, Kearns AM, Ehricht R. 2007. High diversity of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive, methicillin-susceptible isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and implications for the evolution of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:1157–1164. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurt K, Rasigade JP, Laurent F, Goering RV, Žemličková H, Machova I, Struelens MJ, Zautner AE, Holtfreter S, Bröker B, Ritchie S, Reaksmey S, Limmathurotsakul D, Peacock SJ, Cuny C, Layer F, Witte W, Nübel U. 2013. Subpopulations of Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 121 are associated with distinct clinical entities. PLoS One 8:e58155. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghasemzadeh-Moghaddam H, Ghaznavi-Rad E, Sekawi Z, Yun-Khoon L, Aziz MN, Hamat RA, Melles DC, van Belkum A, Shamsudin MN, Neela V. 2011. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus from clinical and community sources are genetically diverse. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301:347–353. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Afroz S, Kobayashi N, Nagashima S, Alam MM, Hossain AB, Rahman MA, Islam MR, Lutfor AB, Muazzam N, Khan MA, Paul SK, Shamsuzzaman AK, Mahmud MC, Musa AK, Hossain MA. 2008. Genetic characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes in Bangladesh. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 61:393–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Wamel WJ, Rooijakkers SH, Ruyken M, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. 2006. The innate immune modulators staphylococcal complement inhibitor and chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus are located on beta-hemolysin-converting bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 188:1310–1315. 10.1128/JB.188.4.1310-1315.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.