Abstract

Cancer-associated human papillomaviruses (HPVs) express E6 oncoproteins that target the degradation of p53 and have a carboxy-terminal PDZ ligand that is required for stable episomal maintenance of the HPV genome. We find that the E6 PDZ ligand can be deleted and the HPV genome stably maintained if cellular p53 is inactivated. This indicates that the E6-PDZ interaction promotes HPV genome maintenance at least in part by neutralization of an activity that can arise from residual undegraded p53.

TEXT

Papillomaviruses induce benign squamous epithelial neoplasms (papillomas) in vertebrates, and the viral DNA genome is maintained as a plasmid within the papilloma. Some virally induced papillomas may evolve over time to produce malignancies (reviewed in reference 1); this typically occurs after many months of chronic infection. Thus, human papillomavirus (HPV) genome maintenance is important to the development of malignancy.

Cancer-associated HPV types are termed “high-risk” HPV. This group expresses virally encoded E7 and E6 oncoproteins that target the degradation of cellular retinoblastoma family proteins and the p53 tumor suppressor, respectively (reviewed in references 2 and 3). The high-risk E7 oncoprotein associates with and targets the degradation of all three retinoblastoma protein (RB) family members, thereby inducing the stabilization of p53 (4) and sensitization of infected keratinocytes to apoptosis and autophagy (5, 6). Although p53 is stabilized, it remains transcriptionally inactive in E7 transduced cells (7).

The alpha genus HPV E6 proteins, both high and low risk, bind to an LXXLL motif (LQELL) on the cellular E3 ubiquitin ligase E6AP (8, 9). The high-risk type E6-E6AP complex then recruits and ubiquitinates p53, leading to its proteasome-mediated degradation (10, 11).

In addition to the targeted degradation of p53, high-risk E6 oncoproteins contain a short peptide sequence at the carboxy terminus that associates with a subset of cellular proteins that contain PDZ domains. The proteins bound by the E6 PDZ binding motif (termed PBM) are diverse and include the human homologues of Drosophila tumor suppressor scaffold proteins DLG (12) and SCRIB (13), tyrosine phosphatases PTPN3 (14) and PTPN13 (15), and multiple other scaffolding proteins implicated in epithelial polarity, membrane trafficking, and cell signaling (16–20). The E6 PBM is subject to phosphorylation and then cytoplasmic tethering to 14-3-3 proteins (21). High-risk E6 can target the degradation of bound cellular PDZ proteins in vitro and in vivo, which has been associated with many phenotypes, including altered epithelial differentiation in transgenic mice (22, 23), reduced growth factor dependence in human keratinocytes (14), promotion of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (24), and cooperation with ras to induce anchorage-independent colony formation (15). In the context of the entire HPV genome, deletion of the E6 PBM causes loss of the viral plasmid upon cell passaging (25). The capacity of high-risk E6 to target the degradation of p53 and the observed targeted degradation of cellular PDZ proteins in vitro have suggested that the role of E6 PDZ associations is to target particular PDZ proteins for degradation during the viral life cycle; however, which interactions of E6 with cellular PDZ proteins are directly related to HPV genome episomal maintenance has remained obscure.

HPV genomes transfected into either primary or immortalized keratinocyte cell lines replicate and are maintained as plasmids during prolonged cell culture. Mutation of viral E6 and E7 genes in the context of the HPV genome has had varied effects upon plasmid maintenance depending upon the cell system employed. High-risk HPV type 31 (HPV-31) genomes containing E6 truncation or missense mutations replicate transiently, but only the wild-type genome was stably maintained as an episomal plasmid in primary keratinocytes; similar mutations in E7 also resulted in loss of high-risk HPV-31 plasmid maintenance (26). Interestingly, truncation mutations of both E6 and E7 simultaneously allowed for the maintenance of the HPV genomes in primary keratinocytes, whereas single mutation of E6 or E7 alone did not, leading to the hypothesis that unbalanced expression of E6 or E7 expression leads to loss of the HPV plasmid (27). In addition to primary keratinocytes, a nontransformed keratinocyte cell line termed NIKS can also maintain transfected alpha genus HPV DNA as episomes in prolonged culture; NIKS cells are of near-normal gross karyotype, are feeder cell and growth factor dependent, produce normal appearing squamous epithelium, and support the full HPV life cycle (28–30). In NIKS cells, deletion of the HPV-16 E6 PBM leads to the loss of genome maintenance (31).

Since alpha genus high-risk E7 oncoproteins invariably target RB, and high-risk E6 oncoproteins invariably target p53 degradation, we hypothesized that the PDZ ligand function of E6 genetically served the function of neutralizing some effect of p53. In papillomavirus-infected cells, residual undegraded p53 has been observed (32, 33), and some papillomavirus-containing head and neck tumors induce p53-responsive genes when irradiated, which can be reduced by small interfering RNA (siRNA) against p53 (34). We have found that further reduction of p53 in keratinocytes attenuates the requirement of the E6 PBM for the stable plasmid maintenance of high-risk viral genomes.

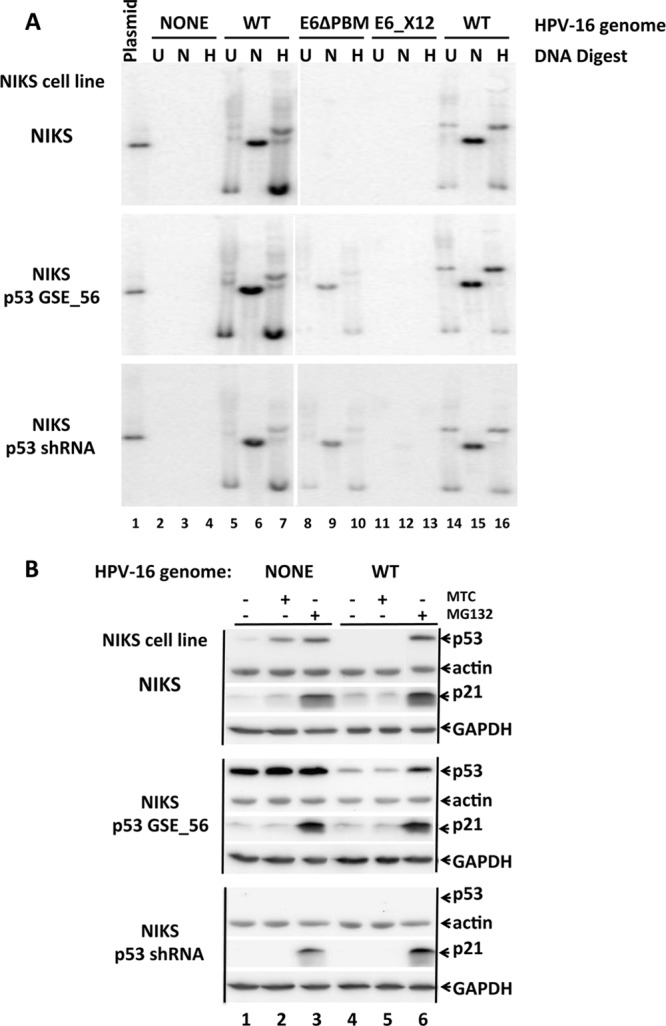

To investigate the role of the E6 PBM in episomal genome maintenance, two different E6 mutants were constructed within the entire HPV-16 genome: a premature stop codon at amino acid 12 of E6 (HPV-16_E6_X12) to ablate all forms of E6, and a premature stop codon at amino acid 150 of E6 that deletes the last two amino acids from 16E6, thereby ablating the E6 PBM (HPV-16_E6ΔPBM). Because high-risk HPV transfection immortalizes keratinocytes through the expression of E6 and E7, there is selection for maintenance of the genome in primary keratinocytes, prompting us to examine HPV genome maintenance in the already immortalized cell line NIKS. Three variants of NIKS keratinocytes were prepared: standard NIKS, NIKS transduced with a lentivirus expressing a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) directed against p53, and NIKS transduced with a dominant-negative inhibitory fragment of p53 (genetic suppressor element 56 [GSE56] [35]). Transduced NIKS cell lines comprised of pooled drug-resistant cells were selected prior to transfection with the wild-type (WT) HPV-16 genome or with genomes with mutations in E6 (HPV-16_E6_X12 or HPV-16_E6ΔPBM). HPV-16 genomes were cleaved from bacterial sequences and religated under dilute conditions to recircularize the genome, before cotransfection with a neomycin resistance expression plasmid into each of the three NIKS cell lines followed by drug selection for 4 days. Pooled colonies were passaged for 8 weeks without neomycin before concurrent harvesting for preparation of total cell DNA.

Figure 1 shows results of Southern blot analysis of the three indicated NIKS cell lines that were each transfected with HPV-16 (WT), HPV-16_E6_X12 (E6_X12), or HPV-16_E6ΔPBM (E6ΔPBM) (9 cell lines). Total cellular DNA preparations were either left alone, cut with NcoI that cuts HPV-16 once or cut with HindIII that does not cut HPV-16. Lanes 14 to 16 show a Hirt lysate sample derived from NIKS cells transfected with WT HPV-16 to serve as a marker of episomal HPV-16. All three blots shown were hybridized simultaneously with a common probe, washed, and exposed concurrently. Figure 1 demonstrates that wild-type HPV-16 replicated episomally in NIKS, NIKS-p53_shRNA, and NIKS-p53_GSE56 cells and that HPV-16_E6_X12 was not present episomally in any of the NIKS cell lines. HPV-16_E6ΔPBM was not maintained in NIKS cells but was maintained as an episomal plasmid in both NIKS_GSE56 and NIKS_p53_shRNA cells after 8 weeks of cell culture.

FIG 1.

Episomal replication of HPV-16_E6ΔPDZ. (A) The three panels are Southern blot exposures using a HPV-16 genomic probe. Three variants of NIKS keratinocytes are indicated to the left of each panel: NIKS cells, NIKS cells expressing an shRNA directed against p53, and NIKS cells transduced with a retrovirus expressing a dominant-negative p53 (GSE56 [35]). Each of the three NIKS cell lines were transfected with the indicated HPV-16 genomes as indicated above the blots: wild-type (WT) HPV-16, HPV-16 with a premature stop codon at amino acid 12 of E6 (E6_X12), and HPV-16 with a premature stop codon at amino acid 150 of E6 that deletes the last two amino acids of E6, thereby ablating the PDZ ligand (E6ΔPDZ). The bacterial sequences were excised, the HPV genomes were recircularized and transfected into the three indicated NIKS cell lines together with a plasmid conferring resistance to G418, and the cells were selected for drug resistance for 4 days. Surviving pooled drug-resistant cell colonies were then passaged 1 or 2 times per week without further drug coselection for 8 weeks before isolation of total cellular DNA. Ten micrograms of uncut (U) DNA or DNA cut with NcoI that cuts HPV-16 once (N) or DNA cut with HindIII (H) that does not cut HPV-16 were loaded per lane. Lane 1 contains 5 pg of unit-length linear plasmid genomic DNA as a marker. Lanes 14 to 16 contain Hirt lysate samples derived from NIKS cells transfected with WT HPV-16 to enrich for episomal supercoiled HPV-16. (B) Expression levels of p53 in NIKS cell lines. The same NIKS cell lines described above for panel A were treated (+) with mitomycin C (MTC) (10 μg/ml) or the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) for 6 h, lysed in 1% SDS, and analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies directed against p53 (p53 AB8, Oncogene Science, Cambridge, MA.), p21Cip (Abcam, Cambridge, MA.), actin (Thermo Scientific), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA.).

It was possible that deletion of the E6 PBM rendered E6 less stable, and thus resulted in loss of the HPV-16_E6ΔPBM genome. A recent report showed that E6 with the PDZ motif deleted is unstable and that E6 association with PDZ domain proteins such as SCRIB increased E6 expression (31). Those results were obtained in transient-expression experiments, and the E6ΔPBM mutant employed in that study deleted 4 amino acids from the C terminus of E6. In this study, we deleted only the last 2 amino acids of E6; we have previously shown that under stable expression conditions, 16E6 WT and 16E6ΔPBM expression levels in NIKS cells are the same (36). In both NIKS cells or NIKS cells expressing GSE56, E6 targeted the degradation of p53 (data not shown).

The finding that repression of p53, through either shRNA or dominant-negative GSE56 expression, can promote the stable episomal replication of HPV-16_E6ΔPBM is perhaps not surprising, given that the presence of an E6 PBM is invariably found in high-risk genomes where E7 proteins target RB degradation and thereby stabilize p53 and is never found in low-risk alpha genus HPV types. Our results also imply that since elimination of p53 function by shRNA or GSE56 can rescue the episomal replication of HPV-16_E6ΔPBM, HPV-16_E6ΔPBM would be better maintained in cells if the E6ΔPBM protein could more fully neutralize p53. This then implies first that E6_ΔPBM is defective in degradation of some biologically active form of p53 that WT E6 can degrade or that PDZ interaction with E6 neutralizes some biological activity of p53 that is independent of the degradation of p53. Further, the absence of stable plasmid maintenance of HPV-16_E6X12 in either NIKS-p53_GSE56 or NIKS-p53_shRNA cells implies that there are E6 functions that promote stable plasmid maintenance that are independent of p53 neutralization.

It is unclear from our experiments whether HPV-16_E6ΔPBM genomes are lost immediately or progressively during cell passaging, but this has been addressed in a recent publication from the Roberts laboratory, which demonstrated that HPV-18 genomes where PBM is deleted from E6 are maintained episomally in early passage transfected keratinocytes, but progressively lost upon cell passaging (37). It is also possible that there could be differences in outcome had our experiments been conducted in primary keratinocytes instead of NIKS cells, where HPV oncogene expression is not necessary for NIKS immortalization.

Our findings give rise to a number of interesting questions. Does deletion of the E6 PBM cause a quantitative difference in the ability of E6 to degrade all forms of p53 in the cell or cause a qualitative difference in the ability to degrade one or more particular p53 isoforms, localizations, or modifications? Does the activity of the wild-type E6 to support genomic maintenance compared to the E6ΔPBM mutant require association with a particular PDZ binding partner or with 14-3-3 or both? Although high-risk type E6-PDZ associations have numerous consequences, which consequences are both necessary to the viral life cycle and unrelated to p53?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants (RO1CA120352 and RO1CA134737) to S.B.V.P.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

While this article was under review, similar conclusions were found by Lorenz et al. (L. D. Lorenz, J. R. Cardona, and P. F. Lambert, PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003717, 2013, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003717).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.zur Hausen H. 2009. Papillomaviruses in the causation of human cancers - a brief historical account. Virology 384:260–265. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roman A, Munger K. 2013. The papillomavirus E7 proteins. Virology 445:138–168. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vande Pol SB, Klingelhutz AJ. 2013. Papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins. Virology 445:115–137. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demers GW, Halbert CL, Galloway DA. 1994. Elevated wild-type p53 protein levels in human epithelial cell lines immortalized by the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 gene. Virology 198:169–174. 10.1006/viro.1994.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones DL, Thompson DA, Munger K. 1997. Destabilization of the RB tumor suppressor protein and stabilization of p53 contribute to HPV type 16 E7-induced apoptosis. Virology 239:97–107. 10.1006/viro.1997.8851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou X, Munger K. 2009. Expression of the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein induces an autophagy-related process and sensitizes normal human keratinocytes to cell death in response to growth factor deprivation. Virology 385:192–197. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichten A, Westfall M, Pietenpol JA, Munger K. 2002. Stabilization and functional impairment of the tumor suppressor p53 by the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. Virology 295:74–85. 10.1006/viro.2002.1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huibregtse JM, Scheffner M, Howley PM. 1993. Localization of the E6-AP regions that direct human papillomavirus E6 binding, association with p53, and ubiquitination of associated proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4918–4927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brimer N, Lyons C, Vande Pol SB. 2007. Association of E6AP (UBE3A) with human papillomavirus type 11 E6 protein. Virology 358:303–310. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. 1993. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell 75:495–505. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheffner M, Werness BA, Huibregtse JM, Levine AJ, Howley PM. 1990. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63:1129–1136. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90409-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiyono T, Hiraiwa A, Fujita M, Hayashi Y, Akiyama T, Ishibashi M. 1997. Binding of high-risk human papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins to the human homologue of the Drosophila discs large tumor suppressor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:11612–11616. 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakagawa S, Huibregtse JM. 2000. Human scribble (Vartul) is targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation by the high-risk papillomavirus E6 proteins and the E6AP ubiquitin-protein ligase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8244–8253. 10.1128/MCB.20.21.8244-8253.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jing M, Bohl J, Brimer N, Kinter M, Vande Pol SB. 2007. Degradation of tyrosine phosphatase PTPN3 (PTPH1) by association with oncogenic human papillomavirus E6 proteins. J. Virol. 81:2231–2239. 10.1128/JVI.01979-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spanos WC, Hoover A, Harris GF, Wu S, Strand GL, Anderson ME, Klingelhutz AJ, Hendriks W, Bossler AD, Lee JH. 2008. The PDZ binding motif of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 induces PTPN13 loss, which allows anchorage-independent growth and synergizes with ras for invasive growth. J. Virol. 82:2493–2500. 10.1128/JVI.02188-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaunsinger BA, Lee SS, Thomas M, Banks L, Javier R. 2000. Interactions of the PDZ-protein MAGI-1 with adenovirus E4-ORF1 and high-risk papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins. Oncogene 19:5270–5280. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SS, Glaunsinger B, Mantovani F, Banks L, Javier RT. 2000. Multi-PDZ domain protein MUPP1 is a cellular target for both adenovirus E4-ORF1 and high-risk papillomavirus type 18 E6 oncoproteins. J. Virol. 74:9680–9693. 10.1128/JVI.74.20.9680-9693.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas M, Laura R, Hepner K, Guccione E, Sawyers C, Lasky L, Banks L. 2002. Oncogenic human papillomavirus E6 proteins target the MAGI-2 and MAGI-3 proteins for degradation. Oncogene 21:5088–5096. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latorre IJ, Roh MH, Frese KK, Weiss RS, Margolis B, Javier RT. 2005. Viral oncoprotein-induced mislocalization of select PDZ proteins disrupts tight junctions and causes polarity defects in epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 118:4283–4293. 10.1242/jcs.02560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeong KW, Kim HZ, Kim S, Kim YS, Choe J. 2007. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein interacts with cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator-associated ligand and promotes E6-associated protein-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Oncogene 26:487–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boon SS, Banks L. 2013. High-risk human papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins interact with 14-3-3zeta in a PDZ binding motif-dependent manner. J. Virol. 87:1586–1595. 10.1128/JVI.02074-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen ML, Nguyen MM, Lee D, Griep AE, Lambert PF. 2003. The PDZ ligand domain of the human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein is required for E6's induction of epithelial hyperplasia in vivo. J. Virol. 77:6957–6964. 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6957-6964.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen MM, Nguyen ML, Caruana G, Bernstein A, Lambert PF, Griep AE. 2003. Requirement of PDZ-containing proteins for cell cycle regulation and differentiation in the mouse lens epithelium. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:8970–8981. 10.1128/MCB.23.24.8970-8981.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson RA, Thomas M, Banks L, Roberts S. 2003. Activity of the human papillomavirus E6 PDZ-binding motif correlates with an enhanced morphological transformation of immortalized human keratinocytes. J. Cell Sci. 116:4925–4934. 10.1242/jcs.00809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee C, Laimins LA. 2004. Role of the PDZ domain-binding motif of the oncoprotein E6 in the pathogenesis of human papillomavirus type 31. J. Virol. 78:12366–12377. 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12366-12377.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas JT, Hubert WG, Ruesch MN, Laimins LA. 1999. Human papillomavirus type 31 oncoproteins E6 and E7 are required for the maintenance of episomes during the viral life cycle in normal human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:8449–8454. 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park RB, Androphy EJ. 2002. Genetic analysis of high-risk E6 in episomal maintenance of human papillomavirus genomes in primary human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 76:11359–11364. 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11359-11364.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen-Hoffmann BL, Schlosser SJ, Ivarie CA, Sattler CA, Meisner LF, O'Connor SL. 2000. Normal growth and differentiation in a spontaneously immortalized near-diploid human keratinocyte cell line, NIKS. J. Investig. Dermatol. 114:444–455. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genther SM, Sterling S, Duensing S, Munger K, Sattler C, Lambert PF. 2003. Quantitative role of the human papillomavirus type 16 E5 gene during the productive stage of the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 77:2832–2842. 10.1128/JVI.77.5.2832-2842.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins AS, Nakahara T, Do A, Lambert PF. 2005. Interactions with pocket proteins contribute to the role of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 in the papillomavirus life cycle. J. Virol. 79:14769–14780. 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14769-14780.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicolaides L, Davy C, Raj K, Kranjec C, Banks L, Doorbar J. 2011. Stabilization of HPV16 E6 protein by PDZ proteins, and potential implications for genome maintenance. Virology 414:137–145. 10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butz K, Shahabeddin L, Geisen C, Spitkovsky D, Ullmann A, Hoppe-Seyler F. 1995. Functional p53 protein in human papillomavirus-positive cancer cells. Oncogene 10:927–936 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tervahauta AI, Syrjanen SM, Vayrynen M, Saastamoinen J, Syrjanen KJ. 1993. Expression of p53 protein related to the presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in genital carcinomas and precancer lesions. Anticancer Res. 13:1107–1111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimple RJ, Smith MA, Blitzer GC, Torres AD, Martin JA, Yang RZ, Peet CR, Lorenz LD, Nickel KP, Klingelhutz AJ, Lambert PF, Harari PM. 2013. Enhanced radiation sensitivity in HPV-positive head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 73:4791–4800. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ossovskaya VS, Mazo IA, Chernov MV, Chernova OB, Strezoska Z, Kondratov R, Stark GR, Chumakov PM, Gudkov AV. 1996. Use of genetic suppressor elements to dissect distinct biological effects of separate p53 domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:10309–10314. 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper B, Brimer N, Vande Pol SB. 2007. Human papillomavirus E6 regulates the cytoskeleton dynamics of keratinocytes through targeted degradation of p53. J. Virol. 81:12675–12679. 10.1128/JVI.01083-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delury CP, Marsh EK, James CD, Boon SS, Banks L, Knight GL, Roberts S. 2013. The role of protein kinase A regulation of the E6 PDZ-binding domain during the differentiation-dependent life cycle of human papillomavirus type 18. J. Virol. 87:9463–9472. 10.1128/JVI.01234-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]