Abstract

Food allergy is a rapidly growing public health concern due to its increasing prevalence and its life threatening potential. Animal models of food allergy have emerged as a tool for identifying mechanisms involved in the development of sensitization to normally harmless food allergens as well as delineating the critical immune components of the effector phase of allergic reactions to food. However, the role animal models might play in understanding human diseases remain contentious. This review summarizes how animal models have provided insights on the etiology of human food allergy, experimental corroboration for epidemiological findings that might facilitate prevention strategies, and validation for the utility of new therapies for food allergy. Improved understanding of food allergy from the study of animal models together with human studies are likely to contribute to the development of novel strategies to prevent and treat food allergy.

Keywords: food allergy, anaphylaxis, murine model, microbiota, regulatory T cells

INTRODUCTION

The genetic revolution over the last decade has had few stronger influences than that on our ability to generate tools from the laboratory mouse. Work stemming from manipulating murine embryonic stem cells earned Drs. Mario Capecchi, Martin Evans and Oliver Smithies the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 2007 and led to a new dawn of scientific inquiry that has revolutionized our understanding of most fields of biology, including immunology and allergy. These tools —gene deletions, gene insertions, gene reporters, and more—, have allowed researchers to define biology in ways previously unobtainable. Despite this, concerns regarding what relevance murine models have in understanding human disease persist. It goes without saying that mice and humans differ in many ways. This was spotlighted recently in a paper reporting that the transcriptional responses observed in murine models of endotoxemia, burns and trauma were not representative of those observed in patients’ samples 1. Although this study has been criticized by leaders in these areas 2, it raised an important question of whether studies performed in mice, or any animal for that matter, have meaningful bearing on the diseases they are intended to inform about.

Interestingly, allergy is one field where this transcriptional analysis approach has shown remarkable consistency between murine samples and human samples. For example, a recent study using a murine model of atopic dermatitis (AD) included comparisons with data from affected human skin and showed a high degree of homology in the gene expression profile 3. Utilizing genetically modified mice, the authors definitively showed key roles for T cells and mast cells in the disease pathogenesis. Similarly, in a murine model of severe asthma, Galli and colleagues performed transcriptional comparison analysis between the murine lung and patient lung biopsies 4. Their data elegantly showed a highly significant association in gene expression pattern that was lost in mast cell deficient mice but was restored if mast cells were reconstituted by adoptive transfer. There is no doubt that such validation approaches will be an important aspect of mechanistic studies moving forward, especially that researchers in the field of allergy possess a strong collection of tools to study the diseases.

This review aims to outline the role animal models might play in understanding food allergy, as well as to highlight how animal models might contribute to the development of future therapies. It is first worth discussing what precisely constitutes an animal model though.

There are generally three main types of approaches to modeling human disease— homologous (in which the underlying cause, symptoms and treatments are shared), isomorphic (in which the symptoms and treatments are shared) and predictive (in which symptoms might be different but treatments show efficacy). Within the allergy field, most models are isomorphic.

As we well know from asthma model research, sensitization using intraperitoneal ovalbumin and alum has been a mainstay approach of the airway inflammation community for many years. However, ovalbumin is not an allergen associated with asthma nor do human subjects encounter antigens via the intraperitoneal route or in the context of alum adjuvant. However, since the type 2 immune response and ensuing eosinophilic airway inflammation are highly associated with asthma, this isomorphic model has facilitated significant progress in our understanding of asthma mechanisms, helped by the availability of tools such as ovalbumin-specific T cell receptor transgenic mice, monoclonal antibodies and tetramers. In recent years, a shift towards using house dust mite has been driven the desire for a more homologous disease model, although there is little data about the physiological relevance of the levels of house dust mite extract delivered to the mice in order to elicit pathology. In food allergy, there is insufficient information regarding the nature of food allergens and the mechanisms responsible for loss or lack of tolerance in patients for us to develop a true homologous model at this time, since feeding of food allergens to mice elicits oral tolerance, like it does in most humans. Instead, mucosal adjuvants such as Cholera Toxin (CT) 5 or Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) 6, 7 or genetically manipulated mouse strains susceptible to enteral sensitization 8 have been employed. Interestingly, physiological exposure to Staphylococcus aureus and/or SEB have been closely connected with many allergic diseases in humans 9, suggesting the potential for a homologous link, although connections between Staphylococcus aureus and food allergy remain to be determined. However, the utilization of these models has already provided significant advances in our understanding of the potential mechanisms of pathogenesis of food allergy and in the development of new therapies.

This review will address how such models can work in synergy with human studies to promote better understand of the mechanisms, etiology and potential therapy for food allergy.

DEFINING THE ETIOLOGY OF FOOD ALLERGY USING MURINE SYSTEMS

One of the critical advantages of using mouse models to study food allergy is that allergic sensitization or tolerance can be induced to specific allergens under controlled environmental conditions within defined genetic backgrounds, which is not possible in humans. This aspect of mouse models allows extensive and precise investigations into the mechanisms involved in disease etiology, such as identification of possible triggers, as well as pathways involved in food allergy. Normally ingestion of food results in oral tolerance in mice, as in most humans. Although the immune mechanisms responsible for breakdown in the oral tolerance are not fully understood, increasing evidence from mouse models indicate that alterations in regulatory T (Treg) cell function and environmental factors such as microbiota are likely important contributors to allergic sensitization and food allergy. Increased intestinal permeability has been suggested as a potential cause of food allergy 10 possibly via increased exposure to intact protein. Loss of oral tolerance may also occur when food antigen is presented via alternative routes, such as the skin, and results in the development of food allergy.

1. Induction mechanisms of food allergy

To establish tolerance or initiate allergic responses against food antigens, dendritic cells (DCs) acting as professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) must encounter the antigens and bring antigens to local lymph nodes. Although the function of various intestinal APC subpopulation to induce tolerance versus sensitization is currently unclear and needs further investigation (Readers are referred elsewhere 11, 12), under normal conditions, CD103+ dendritic cells (DCs) have been thought to capture antigen in the lamina propria (LP) and Peyer’s patches and migrate to the mesenteric lymph node (MLN) where they induce Treg cells that migrate back to the LP. Resident CX3CR1+ macrophages in LP can expand Treg cells that suppress generation of type 2 cytokines and immunoglobulin (Ig) E, as well as the effector functions of mast cells and basophils, thus inhibiting allergic inflammation and food hypersensitivity. The importance of Treg cells in the development of tolerance has been demonstrated in both mice and humans, in which deficiency of forkhead box protein 3 (Foxp3)+ T cells leads to increased allergic disorders such as AD and food allergy 13. Transfer of Treg cells induces oral tolerance in mice 14 and antigen-specific CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Treg cells are associated with the onset of clinical tolerance to milk 15.

Mucosal adjuvants CT and SEB have been widely used to overcome oral tolerance to co-administered antigens. Oral sensitization to various food antigens in the presence of CT or SEB has been shown to be effective in inducing antigen-specific IgE and systemic anaphylaxis upon antigen exposure 6, 16. Orally administered CT is thought to promote type 2 responses and food hypersensitivity through the upregulation of the costimulatory molecule OX40L on gastrointestinal CD103+ DC 17 that are normally tolerogenic. Additionally, IL-33, but not thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) or IL-25, has been shown to upregulate OX40L on DCs 18. While CT is unlikely to play a role in the etiology of human food allergy, these results raise the possibility that factors that stimulate intestinal epithelial cells to produce IL-33 may trigger type 2 responses to ingested foods. Polymorphisms in IL-33 and/or its receptor ST2 genes are highly associated with allergic diseases 19, further supporting their potential roles in human food allergy. Although further studies are needed to determine whether these adjuvants also directly suppress the generation or functions of Treg cells, dysfunction of Treg cells after SEB exposure has previously been shown in samples from AD patients 9. Oral SEB-driven sensitization resulted in type 2 response and antigen-triggered anaphylaxis with decreased expression of intestinal transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and Foxp3 6 while transfer of Treg cells from unexposed mice was also sufficient to diminish food allergy responses in this model 20.

Enteral sensitization to food allergens can also be elicited in the absence of CT or SEB in mice genetically manipulated to enhance IL-4 responses. For instance, Il4raF709 mice, in which IL-4 signaling is enhanced due to disruption of the inhibitory signaling motif in the IL-4 receptor α-chain, exhibit sensitization to food proteins, mast cell expansion, anaphylactic responses following food challenge and a food allergy specific gut microbiota 8, 21, 22. Recent studies have revealed defective induction and function of Il4raF709 Treg cells due to their Th2 reprogramming (Chatila TA and Oettgen HC, manuscript in preparation). These findings implicate strong IL-4 signals, such as those that might be encountered in the Th2 milieu of atopic patients, in subverting Treg cell responses to oral antigens and fostering the development of food specific IgE, intestinal mast cell expansion and susceptibility to anaphylaxis.

Emerging data suggest that allergic sensitization to foods may occur by routes other than the tolerance-promoting oral route, such as exposure via the skin or the respiratory tract. Mouse models have demonstrated that sensitization through skin successfully elicited allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis to a various food antigens, including egg, peanuts, and hazelnuts 23–25. Mice cutaneously exposed to hazelnut protein exhibited sustained hazelnut-specific IgE antibodies associated with memory IgE and IL-4 response after eight months of antigen withdrawal 26, which may reflect the situation in humans with persistent clinical sensitivity to peanuts and tree nuts. Cutaneous exposure was most effective in triggering food sensitization than intragastric, intranasal or sublingual routes 5, indicating that skin may be a potent route of food sensitization. In contrast, antigen uptake through intact skin has also been shown to downregulate antigen-specific responses 27. Data from these mouse models suggest that additional factors such as adjuvant 5 or skin barrier disruption 23 in addition to antigen entry are required for food sensitization. These factors may promote antigen sensitization by activating skin DCs, as DCs derived from mechanically disrupted skin were shown to be programmed by keratinocyte-derived TSLP 28 to bring antigen to MLN 29 where they may induce local Th2 responses. Following subcutaneous immunization, retinoic acid may also be important for subsequent homing of T and B cells to the gut 30. Conversely, antigen-specific gut-homing T cells can be reprogrammed following cutaneous antigen exposure to migrate to the skin and elicit allergic skin inflammation in the mouse 29, suggesting a bidirectional crosstalk between skin and gut.

2. Microbiota regulation of tolerance and allergy

Alterations in the microbiota have now been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, asthma, and food allergy 31. Intestinal microbiota influence the network of the immune system and result in impaired regulatory functions and Th2 skewing. While germ free (GF) conditions are almost impossible in human studies, limiting the types of analysis that can be performed, a role for commensal microbiota in promoting oral tolerance has been clearly defined using gnotobiotic mice, in which reconstitution of GF mice with well-characterized communities of microbiota or defined bacteria. CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells are reduced in antibiotic-treated mice or GF mice 32, 33, which exhibit a predisposition towards allergic sensitization 33, 34. Administration of defined commensal microbiota such as Clostridia and Bacteroides fragilis or short-chain fatty acids, microbiota-derived products, to GF mice induced Treg cells 32, 35–38, and reduced allergic sensitization 32, supporting the notion that intestinal commensal microbiota promote Treg cells and limit allergic responses to foods. Il4raF709 mice carrying a gain-of-function mutation in IL-4 receptor α chain, which are susceptible to allergic sensitization and to anaphylaxis 8, 21, exhibit an altered gut microbiota signature from that in control mice 21. GF mice reconstituted with these microbiota exhibit allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis. Transfer of antigen-specific Treg cells to Il4raF709 mice is capable of both restoring the normal microbiota and suppressing the allergic responses 21. A recent study demonstrated a successful reconstitution of mice with human microbiota that resulted in an increase in Treg cells and amelioration of allergic diarrhea 39. Intriguingly, mice co-housed with or progeny of reconstituted mice with human microbiota also exhibited increased Treg cells 39. These findings suggest that susceptibility to or protection against food allergy may be a transmissible trait. These murine approaches are powerful tools for dissecting the interaction between microbiota and disease pathogenesis, opening potential investigations of a myriad of human microbiota that are beneficial or harmful in treatment and management of allergic conditions.

3. Effector mechanisms of food allergy

Once food sensitization is established, re-exposure to antigen can lead to local or systemic manifestations of food allergy. Systemic antigen sensitization with intraperitoneal adjuvant has been primarily performed to induce antigen sensitization and food hypersensitivity responses upon antigen challenge, therefore provided important insights on the mechanisms of the effector phases of food allergy 40. Early clinical evidence suggested that anaphylaxis was classically mediated by antigen-cross linking of antigen-specific IgE bound to FcεRI on mast cells inducing the rapid release of mediators such as histamine and leukotrienes, which act on responder cells to induce vasodilation, increased vascular permeability and hypotension, and bronchospasm that commonly manifest as a shock 41. Mouse models of anaphylaxis have well-defined alternative pathways of systemic anaphylaxis mediated by IgG, FcγRIII, neutrophils, macrophages, basophils, and platelet-activating factor (PAF) 40, some of which may also play a role in human systems. Subsequent findings showed that human neutrophils activated via IgG mediated systemic anaphylactic shock in mice 42. This was further defined using mice engineered to express human FcγRs 43 and, taken together, sheds new light on the role of neutrophils in human anaphylaxis. As in the mouse studies 44, PAF levels were associated with the severity of anaphylaxis in humans 45 while PAF acetylhydrolase was decreased in patients with fatal anaphylaxis 45, suggesting that the failure of PAF inactivation may increase anaphylactic severity. Mouse studies have suggested that anaphylaxis caused by food allergen ingestion is IgE-dependent, whereas anaphylaxis induced by systemically administered allergen is mediated by both IgG and IgE pathways 40. The IgE pathway is also more sensitive, requiring lower levels of antigen compared to IgG mediated responses 46. Possible markers that distinguish IgE- versus IgG-mediated anaphylaxis have been suggested in mouse models 47, but have not yet been extended to human studies.

Like in humans, the susceptibility of mice to food anaphylaxis seems variable, with antigen and strain influences. C3H/HeJ mice, but not BALB/c mice, sensitized orally with CT and antigen were susceptible to oral food anaphylaxis 48. C3H/HeJ mice lack functional toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 that recognizes lipopolysaccharide 49, but a requirement of TLR4 impairment for food anaphylaxis was exclusive to a C3H/HeJ background and peanut protein, but not seen in BALB/c background or to cow’s milk (CM) antigen 16. Mouse studies have indicated that food antigens must be absorbed systemically to induce anaphylaxis 50, and inhibiting the antigen passage through intestinal epithelium can prevent anaphylaxis 51. Indeed, systemic antigen challenge does induce anaphylaxis in typically resistant strains such as C57Bl/6 mice 52. Although the precise mechanisms underlying the variable genetic susceptibility to food allergy are not known, these results are consistent with the observations in humans that the predisposing genetic factors are important 53.

Gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, are common symptoms of food-induced anaphylaxis in mice and have helped define key mechanisms of response. Repeated oral antigen challenge of mice intraperitoneally immunized with ovalbumin and alum induced dose-dependent acute diarrhea associated with increased intestinal permeability and mastocytosis 54, 55. This diarrhea was dependent on IgE-mast cell pathway and on a combination of serotonin and PAF 54. These results highlight the critical role for mast cells in allergic diarrhea, and intestinal mast cell numbers were associated with systemic anaphylaxis severity 56. The role of T cells in allergic diarrhea was demonstrated by adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells purified from MLN of sensitized mice, which transferred antigen-triggered diarrhea to the naïve recipients 57. Mast cells produce type 2 cytokines and Th2 chemoattractants and may recruit Th2 cells to the gut 57. Conversely, type 2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, IL-9) in the gut may promote mast cell expansion/recruitment in the gut 8, 22, 58, 59. The crosstalk between Th2 cells and mast cells and its role in the development of food allergy may be an important aspect of intestinal pathogenesis and need to be further investigated.

4. Antigen cross reactivity

Several legumes, especially peanut, exhibit an extensive serological cross-reactivity. Mouse models have helped define such cross reactivity in controlled exposure environments that are impossible in humans because of the implicit problems in determining a cross reactive versus multi-sensitization in patients. For example, lupin and fenugreek have been implicated as triggers of reactions in peanut allergic patients 60, 61. Mice orally sensitized to lupin or fenugreek exhibited hypersensitivity reactions to challenge with peanut, soy, fenugreek or lupin, providing direct experimental evidence of the physiologic relevance of this cross-reactivity among legumes. Similarly, mice sensitized with cow’s milk (CM) exhibited CM-specific IgE and IgG1 antibodies that cross-reacted with soy proteins, analogous to the data obtained in human 62, 63. These mice developed anaphylaxis to oral challenge with soy protein 64. Although it is not clear whether cross-reactive IgE and IgG1 predict the elicitation of clinical symptoms to the cross-reactive allergens in humans, such studies will likely have important implications for further characterization of cross allergenicity among food allergens.

INSIGHTS ON PREVENTION OF FOOD ALLERGY

Findings from clinical and epidemiological research and results from animal models are mutually supportive in increasing their significance; clinical studies of epidemiological factors on disease identify a possible causative factor associated with the onset of the disease and provide valuable findings, and animal models allow the inferences from these studies to be experimentally tested to directly assess causality. For example, clinical studies have suggested that cutaneous (environmental) exposure to antigen, or maternal antigen transmission during pregnancy and breast-feeding, might play a role in food sensitization. Similarly, the observations that patients treated with anti-ulcer medication developed allergic responses to co-ingested foods led to the hypothesis that acid suppression is a risk factor for food allergy. Mouse models have enabled the testing of these hypotheses and provided insight into the molecular and cellular mechanisms. Bring out

1. Route of antigen exposure

The observations that oral exposure to foods is limited in infancy, and that allergic reactions to foods are reported to occur on the first known ingestion suggest potential roles for other routes of allergen exposure. Epidemiologic data suggest that sensitization to peanut protein can occur in children through the exposure to peanut in oils to inflamed skin 65 while early oral exposure to food antigen induces tolerance 66. Food allergen consumption at home correlates with the incidence of food allergy 67. Furthermore, loss of function mutations in filaggrin, a gene that encodes the epithelial barrier protein filaggrin, conferred increased risk for AD and other allergies, including peanut allergy 68, 69. These observations led to the hypothesis that the altered barrier function in AD skin may facilitate cutaneous sensitization to food antigens, potentially leading to the development of food allergies. We have recently used a mouse model of allergic skin inflammation with many features of AD and AD-associated asthma 70 to demonstrate that epicutaneous sensitization with the food antigen results in IgE-dependent expansion of intestinal mast cells and IgE-mediated anaphylaxis upon oral challenge 23. Our findings support the hypothesis that cutaneous sensitization to food allergens plays an important role in the development of food allergy, and show that IgE and intestinal mast cells are critical to this pathology. Further evidence is that sensitization to ovalbumin occurred through the skin of flaky tail mice that carry a mutation in filaggrin gene and resulted in production of antigen-specific IgE 71, 72, and provided conclusive evidence that filaggrin deficiency and consequent skin barrier dysfunction enhances antigen sensitization. Avoidance of cutaneous exposures might prevent the development of food anaphylaxis. Recovery of skin barrier function by increasing filaggrin expression in keratinocytes 73 may be potentially beneficial for AD and AD-associated food allergy.

2. Maternal transmission

Maternal allergy is a risk factor for allergic disease in children, however, there is no direct evidence of maternal transmission of allergy susceptibility to children. It also remains controversial whether the antigen exposure during pregnancy predisposes the child to allergic disease. Peanut consumption during pregnancy associating with the development of peanut sensitization in infants has been supported 74 and refuted 65. Mouse studies have convincingly shown that antigen exposure during pregnancy protected the offspring against allergic sensitization 75–77. Mechanistically, this tolerance induction was due to TGF-β and antigen 77 or antigen-IgG immune complexes 76, 78 transferred via breast milk. Additionally, exposure of pregnant mice to certain bacteria prevents the development of an allergic phenotype in the offspring 79, implying protective effects by early-life microbial exposure. There is currently no supportive human study for the protective effect of maternal antigen ingestion and further studies are needed to examine whether a similar approach would be amenable in humans.

3. Acid Suppression

Alterations in gastric digestive capacity may affect the allergenicity of ingested food proteins 80. The increased risk of developing food sensitization was first described as associating with the use of acid-suppressing medication in patients being treated for peptic ulcers and their developing food allergen sensitization 81. Anti-ulcer medication during pregnancy has been associated with a higher risk of developing asthma in childhood 82. Similar to these findings in humans, antacid treatment promoted oral sensitization and hypersensitivity to hazelnut allergens in mice 83 and concomitant feedings of pregnant mice with anti-ulcer drug and codfish induced codfish-specific IgE in mothers and Th2 milieu in their offspring 84. These examples highlight the utility of mouse models to define the associative or causal influences of epidemiological factors identified in food allergy studies in humans.

TREATMENT

The requirements for strict allergen avoidance and the use of injectable epinephrine in emergency situations have been shown to contribute to the significant adverse effect food allergy can have on patients’ quality of life 85. Consequently, providing improved therapeutic options has become an important avenue for food allergy research. Since the FDA typically requires animal testing before issuing an Investigational New Drug (IND), preclinical animal models of food allergy will likely be a necessary step towards achieving this goal. Indeed, studies in animal models have already supported advancements of therapy in three key areas: 1) validation of existing therapeutic strategies, 2) utility of existing therapies for food allergy, and 3) development of novel therapies. While there has been significant interest in the third point, it seems likely that the animal studies aimed at validation and utility of existing therapeutics can lead to relatively immediate and potentially significant improvements in therapy options for food allergy patients.

1: Validation of existing therapeutic approaches

In the recent “Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel”, the recommendations for treatment of food induced anaphylaxis in a hospital setting included the use of H2 antihistamines (ranitidine, 1–2 mg/kg per dose), in addition to H1 antihistamines and other standard allergy treatment strategies 86. Indeed, combination H1 and H2 antihistamines have shown efficacy for acute allergic reactions in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial 87. Despite this, the rationale for H2 antihistamine use seemed unclear since these readily available drugs are mainly utilized for their acid-suppressing abilities and roles of the H2 receptor in systemic anaphylactic reactions had not been shown. Taking advantage of genetically deficient mice and the ability to completely eliminate the contributions of each specific receptor, we recently demonstrated that IgE-dependent anaphylactic responses in the mouse were only partially ablated in the absence of either H1 or H2 88. In contrast, deficiency in both H1 and H2 provided substantial protection. This was also evident if intravenous histamine, sufficient to elicit responses, was used. Our study provides conclusive evidence to support the rationale of using H2 antihistamines in food allergy therapy.

Similarly, there has been substantial efforts to determine the efficacy and safety of oral immunotherapy (OIT) for several food allergens, including milk, egg and peanut 89. These have been approached mainly through relatively small-scale clinical trials, perhaps due to the risks associated with adverse reactions to food administration. Despite concluding that there is a measurable benefit to OIT therapy, a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of many of the peanut studies raised concerns over the lack of consistency in design and readouts that limited the proper determination of the efficacy and safety of this treatment 90. The mechanistic understanding of the clinical benefits of OIT therapy also remains elusive, with desensitization versus tolerance still under investigation. By using a murine model of food allergy, Berin and colleagues were able to clearly demonstrate significant reduction in food allergy-associated symptoms through a modified OIT strategy 91. Furthermore, they defined a unique protective mechanism that localized to the intestinal mucosal compartment, rather than a systemic influence over the Foxp3+ Treg cell compartment, which has been the focus of many clinical studies. The use of mice allowed these investigators to examine the mechanisms of protection in a way that would be extremely difficult in human trials. In this way, the use of murine models can provide focus and understanding that may help in the design of future clinical trials, particularly for deciding on measures of efficacy.

2. Application of existing therapies to food allergy

The global suppression of immune responses is a common therapeutic strategy applied to inflammatory diseases, including allergic asthma, autoimmune diseases or post-transplantation. For allergic asthma, glucocorticoids have become a mainstay and yet they are generally considered ineffective for food allergy. Work in a murine model of food allergy examined the potential effects of rapamycin in altering food allergy responses 92. Perhaps not surprisingly given its potent abilities to suppress T cell responses, rapamycin was able to diminish the generation of food allergy-associated pathology when given during the sensitization window. In addition, treatment of fully sensitized mice was also sufficient to reduce the severity of diarrhea, symptoms and core body temperature drops seen upon antigen challenge. Interestingly, the immediate responses to passive immunization with antigen-specific IgE or in cultured mast cells were unaffected but instead, the IL-9-mediated survival of mast cells was diminished. Increasing evidence from animal models has supported the critical role for mast cells and the IL-9 pathway in the severity of food allergy responses 55, 59, including the beneficial effects of mast cell stabilization in IL-9 transgenic mice with systemic cromolyn sodium treatment 59. Interestingly, several case reports have shown therapeutic benefit from oral cromolyn sodium treatment for food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis 93, 94 and, taken together, suggest that existing therapies that limit mast cell numbers or enhance mast cell stability may be clinically effective for food allergy.

Similarly, recent work has demonstrated the potential efficacy of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor compound Sunitinib malate (trade name Suntent) 95 in food allergy models. Sunitinib malate inhibits several receptor systems, including that of the stem cell factor receptor that is highly expressed on mast cells, and has been successfully used in the treatment of renal carcinoma and imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal tumors 96. Although high doses were used, the findings demonstrated a clear diminishment of oral-antigen triggered anaphylactic responses in mice previously sensitized to ovalbumin. Importantly, inhibition of passively immunized mice, as well as primed in vitro mast cells, was shown, suggesting that the efficacy of this approach lies with inhibition of the immediate mast cell response to antigen.

These examples highlight how animal models of food allergy can serve as a screening tool to examine the potential biological efficacy of therapeutic compounds that are already approved for other uses. The obvious benefit to this approach lies with the existing safety information available from previous clinical trials that may generate therapeutic options faster than new developments.

3. Screening for efficacy of new therapies

During the last decade, there have been many examples of potential therapies for food allergy that have been demonstrated using murine models. One of the most discussed is the use of Chinese herbal formulations, the subject of previous reviews 97. In particular, work on food allergy herbal formula-2 (FAHF-2) has demonstrated the potential for murine models as a tool to aid in development of novel therapies. FAHF-2, a concoction of nine herbal extractions, has been clearly demonstrated to limit the severity and progression of food allergic responses to peanut in these models and its effects were sustained over several months 98. Importantly, while relatively large doses of the extracted formulation are necessary, there was no reported evidence of toxicity from this treatment strategy. In an initial phase 1 trial of eighteen patients, FAHF-2 has been reported as safe and to have reduced the CD63 expression, an activation marker, on ex vivo stimulated basophils from these patients 99. Further studies have begun aimed at elucidating the mechanisms through which these effects might be mediated.

Umetsu and colleagues recently demonstrated that the neutralizing anti-IgE antibody omalizumab may facilitate rapid oral desensitization in high risk peanut-allergic patients 100, further supporting the potential of anti-IgE as the treatment of food allergy. The efficacy of antibodies specific for a segment of human membrane IgE on depleting IgE producing B cells has been proven in humanized mice expressing human M1’ domain 101, strengthening the value of the animal model in the development of a new treatment of food allergy.

We also reported a potential new therapy in antigen-coupled cell tolerance 102. Drawing from numerous studies in autoimmunity and transplantation, chemical coupling of antigens to the surface of autologous cells has been shown to promote specific and sustained tolerance 103 but it was unknown if this would be effective in type 2 immunity, such as allergy. Additionally, this method requires intravenous antigen delivery that, particularly for food allergy, is a challenging concept to accept would not cause adverse reactions. Using murine models of allergy, we demonstrated that this approach was potently capable of reducing peanut-specific immune responses and could be delivered to peanut sensitized animals without eliciting any reactions. The first phase 1 clinical trial of this type of tolerance induction has recently been reported for treatment of multiple sclerosis and established the tolerability and safety, as well as showing decreased myelin peptide specific immune responses in several patients 104.

SUMMARY

In summary, animal models of food allergy are invaluable tools for dissecting etiology, mechanisms and preventive strategies, as well as assisting in the identification, validation and development of therapies before they progress towards patients. While the application of animal models to human disease requires careful and thorough consideration and interpretation, their utility in facilitating truly translational discoveries has been demonstrated repeatedly and on many levels. Particularly in the setting food allergy, where risks of adverse reactions to therapy are a major issue for patients, animal models will be indispensible to effectively and ethically develop new treatments. Mechanistically, the recent discoveries of the roles of microbiota on the etiology of food allergy, derived from studies of animal models, provides an excellent example of how lessons learned from experimental animals can provide new breakthrough areas that educate future studies of host factors in human patients with food allergy.

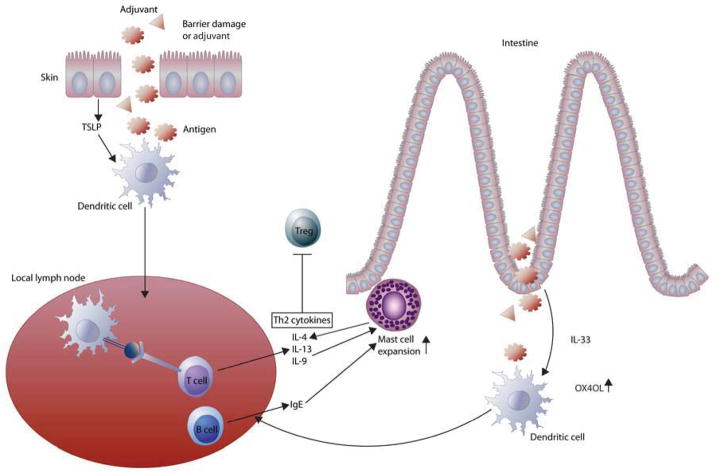

Figure 1. Possible mechanisms of allergic sensitization to food antigens.

Altered skin barrier (or adjuvant) allows antigen entry and stimulates keratinocyte to produce TSLP that activates skin derived DCs, which promote the differentiation of Th2 cells and IgE producing B cells in draining lymph node. Orally administered mucosal adjuvant induces IL-33 secretion by intraepithelial cells that upregulates OX40L expression on DCs that promote Th2 response in MLN. Increased Th2 cytokines and IgE mediate intestinal expansion of mast cells that may in turn recruit Th2 cells to the intestine and increase intestinal permeability that results in the development of gastrointestinal symptoms including diarrhea. Increased Th2 milieu, such as those in Il4raF709 mice, may hinder Treg cell function that leads to loss of oral tolerance to food antigens.

Table 1.

Key points

| Animal models allow extensive investigation into the mechanisms of allergic sensitization or tolerance to specific allergens under controlled environmental conditions within defined genetic background, which promote better understanding of the etiology of human food allergy. |

| Animal models have identified key factors responsible for breakdown in the oral tolerance such epithelial cytokine that activate DCs to promote a Th2 milieu, altered microbiota, or antigen exposure via alternative routes such as skin. |

| Animal models have defined effector mechanisms of food allergy, some of which may also play role in humans: IgE- and IgG-mediated pathways of anaphylaxis, variable genetic susceptibility food allergy, and T- and mast cell-dependent diarrhea. |

| Animal models enable experimental investigation to delineate the associative or causal influences of epidemiological findings in humans, which might facilitate prevention strategies. |

| Animal models allow validation and utility of existing therapeutics as well as development of novel therapies, which can lead to significant improvements in therapy options for food allergy patients. |

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R21 AI 080002 (TAC), R56 AI100889-01 (HCO), R56 AI105839-01 (PJB), Department of Defense grant award 11-1-0553 (TAC), and the Bunning Foundation (RSG). MKO was supported by the Harvard Digestive Disease Center, NIH Grant P30 DK34845, the Children’s Hospital Boston Faculty Career Development Fellowship/Eleanor and Miles Shore Program for Scholars in Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and Children’s Hospital Pediatric Associates Award.

Abbreviations

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CM

cow’s milk

- CT

cholera toxin

- DC

dendritic cells

- FAHF-2

food allergy herbal formula-2

- Foxp3

forkhead box protein 3

- GF

germ free

- IL

Interleukin

- LP

lamina propria

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- OIT

oral immunotherapy

- PAF

platelet activating factor

- SEB

Staphylococcal enterotoxin B

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TSLP

thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- Treg

regulatory T

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Seok J, Warren HS, Cuenca AG, Mindrinos MN, Baker HV, Xu W, et al. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perlman H, Budinger GR, Ward PA. Humanizing the mouse: in defense of murine models of critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:898–900. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0489ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando T, Matsumoto K, Namiranian S, Yamashita H, Glatthorn H, Kimura M, et al. Mast Cells Are Required for Full Expression of Allergen/SEB-Induced Skin Inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu M, Eckart MR, Morgan AA, Mukai K, Butte AJ, Tsai M, et al. Identification of an IFN-gamma/mast cell axis in a mouse model of chronic asthma. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3133–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI43598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunkin D, Berin MC, Mayer L. Allergic sensitization can be induced via multiple physiologic routes in an adjuvant-dependent manner. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1251–8. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganeshan K, Neilsen CV, Hadsaitong A, Schleimer RP, Luo X, Bryce PJ. Impairing oral tolerance promotes allergy and anaphylaxis: a new murine food allergy model. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:231–8. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang PC, Xing Z, Berin CM, Soderholm JD, Feng BS, Wu L, et al. TIM-4 expressed by mucosal dendritic cells plays a critical role in food antigen-specific Th2 differentiation and intestinal allergy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1522–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathias CB, Hobson SA, Garcia-Lloret M, Lawson G, Poddighe D, Freyschmidt EJ, et al. IgE-mediated systemic anaphylaxis and impaired tolerance to food antigens in mice with enhanced IL-4 receptor signaling. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:795–805. e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ou LS, Goleva E, Hall C, Leung DY. T regulatory cells in atopic dermatitis and subversion of their activity by superantigens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:756–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groschwitz KR, Hogan SP. Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2009;124:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.038. quiz 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pabst O, Mowat AM. Oral tolerance to food protein. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:232–9. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiter B, Shreffler WG. The role of dendritic cells in food allergy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012;129:921–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatila TA. Role of regulatory T cells in human diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:949– 59. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.047. quiz 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadis U, Wahl B, Schulz O, Hardtke-Wolenski M, Schippers A, Wagner N, et al. Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity. 2011;34:237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shreffler WG, Wanich N, Moloney M, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA. Association of allergen-specific regulatory T cells with the onset of clinical tolerance to milk protein. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:43–52. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berin MC, Zheng Y, Domaradzki M, Li XM, Sampson HA. Role of TLR4 in allergic sensitization to food proteins in mice. Allergy. 2006;61:64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blazquez AB, Berin MC. Gastrointestinal dendritic cells promote Th2 skewing via OX40L. J Immunol. 2008;180:4441–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu DK, Llop-Guevara A, Walker TD, Flader K, Goncharova S, Boudreau JE, et al. IL-33, but not thymic stromal lymphopoietin or IL-25, is central to mite and peanut allergic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:187–200. e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grotenboer NS, Ketelaar ME, Koppelman GH, Nawijn MC. Decoding asthma: translating genetic variation in IL33 and IL1RL1 into disease pathophysiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:856– 65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganeshan K, Bryce PJ. Regulatory T Cells Enhance Mast Cell Production of IL-6 via Surface-Bound TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2012;188:594–603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noval Rivas M, Burton OT, Wise P, Zhang YQ, Hobson SA, Garcia Lloret M, et al. A microbiota signature associated with experimental food allergy promotes allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:201–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton OT, Darling AR, Zhou JS, Noval-Rivas M, Jones TG, Gurish MF, et al. Direct effects of IL-4 on mast cells drive their intestinal expansion and increase susceptibility to anaphylaxis in a murine model of food allergy. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:740–50. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartnikas LM, Gurish MF, Burton OT, Leisten S, Janssen E, Oettgen HC, et al. Epicutaneous sensitization results in IgE-dependent intestinal mast cell expansion and food-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:451–60. e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birmingham NP, Parvataneni S, Hassan HM, Harkema J, Samineni S, Navuluri L, et al. An adjuvant-free mouse model of tree nut allergy using hazelnut as a model tree nut. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007;144:203–10. doi: 10.1159/000103993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strid J, Hourihane J, Kimber I, Callard R, Strobel S. Epicutaneous exposure to peanut protein prevents oral tolerance and enhances allergic sensitization. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;35:757–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonipeta B, Parvataneni S, Paruchuri P, Gangur V. Long-term characteristics of hazelnut allergy in an adjuvant-free mouse model. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;152:219–25. doi: 10.1159/000283028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mondoulet L, Dioszeghy V, Larcher T, Ligouis M, Dhelft V, Puteaux E, et al. Epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) blocks the allergic esophago-gastro-enteropathy induced by sustained oral exposure to peanuts in sensitized mice. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oyoshi MK, Larson RP, Ziegler SF, Geha RS. Mechanical injury polarizes skin dendritic cells to elicit a T(H)2 response by inducing cutaneous thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:976–84. 84 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oyoshi MK, Elkhal A, Scott JE, Wurbel MA, Hornick JL, Campbell JJ, et al. Epicutaneous challenge of orally immunized mice redirects antigen-specific gut-homing T cells to the skin. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2210–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI43586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammerschmidt SI, Friedrichsen M, Boelter J, Lyszkiewicz M, Kremmer E, Pabst O, et al. Retinoic acid induces homing of protective T and B cells to the gut after subcutaneous immunization in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3051–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI44262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marrs T, Bruce KD, Logan K, Rivett DW, Perkin MR, Lack G, et al. Is there an association between microbial exposure and food allergy? A systematic review. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24:311–20. e8. doi: 10.1111/pai.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Hartmann M, Willing BP, Thorson L, Wlodarska M, et al. Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:440– 7. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bashir ME, Louie S, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling by intestinal microbes influences susceptibility to food allergy. J Immunol. 2004;172:6978–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geuking MB, Cahenzli J, Lawson MA, Ng DC, Slack E, Hapfelmeier S, et al. Intestinal bacterial colonization induces mutualistic regulatory T cell responses. Immunity. 2011;34:794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lathrop SK, Bloom SM, Rao SM, Nutsch K, Lio CW, Santacruz N, et al. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. 2011;478:250–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, Suda W, Nagano Y, Nishikawa H, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finkelman FD. Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:506– 15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.033. quiz 16–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:827–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI45434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonsson F, Mancardi DA, Kita Y, Karasuyama H, Iannascoli B, Van Rooijen N, et al. Mouse and human neutrophils induce anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1484–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI45232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mancardi DA, Albanesi M, Jonsson F, Iannascoli B, Van Rooijen N, Kang X, et al. The high-affinity human IgG receptor FcgammaRI (CD64) promotes IgG-mediated inflammation, anaphylaxis, and antitumor immunotherapy. Blood. 2013;121:1563–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arias K, Chu DK, Flader K, Botelho F, Walker T, Arias N, et al. Distinct immune effector pathways contribute to the full expression of peanut-induced anaphylactic reactions in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1552–61. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vadas P, Gold M, Perelman B, Liss GM, Lack G, Blyth T, et al. Platelet-activating factor, PAF acetylhydrolase, and severe anaphylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:28–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strait RT, Morris SC, Finkelman FD. IgG-blocking antibodies inhibit IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in vivo through both antigen interception and Fc gamma RIIb cross-linking. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:833–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI25575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khodoun MV, Strait R, Armstrong L, Yanase N, Finkelman FD. Identification of markers that distinguish IgE- from IgG-mediated anaphylaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12413–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105695108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morafo V, Srivastava K, Huang CK, Kleiner G, Lee SY, Sampson HA, et al. Genetic susceptibility to food allergy is linked to differential TH2-TH1 responses in C3H/HeJ and BALB/c mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1122–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–8. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strait RT, Mahler A, Hogan S, Khodoun M, Shibuya A, Finkelman FD. Ingested allergens must be absorbed systemically to induce systemic anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:982–9. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martos G, Lopez-Exposito I, Bencharitiwong R, Berin MC, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Mechanisms underlying differential food allergy response to heated egg. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:990–7. e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smit JJ, Willemsen K, Hassing I, Fiechter D, Storm G, van Bloois L, et al. Contribution of classic and alternative effector pathways in peanut-induced anaphylactic responses. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brandt EB, Strait RT, Hershko D, Wang Q, Muntel EE, Scribner TA, et al. Mast cells are required for experimental oral allergen-induced diarrhea. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1666–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI19785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osterfeld H, Ahrens R, Strait R, Finkelman FD, Renauld JC, Hogan SP. Differential roles for the IL- 9/IL-9 receptor alpha-chain pathway in systemic and oral antigen-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:469–76. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahrens R, Osterfeld H, Wu D, Chen CY, Arumugam M, Groschwitz K, et al. Intestinal mast cell levels control severity of oral antigen-induced anaphylaxis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:1535– 46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knight AK, Blazquez AB, Zhang S, Mayer L, Sampson HA, Berin MC. CD4 T cells activated in the mesenteric lymph node mediate gastrointestinal food allergy in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1234–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00323.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brandt EB, Munitz A, Orekov T, Mingler MK, McBride M, Finkelman FD, et al. Targeting IL-4/IL-13 signaling to alleviate oral allergen-induced diarrhea. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Forbes EE, Groschwitz K, Abonia JP, Brandt EB, Cohen E, Blanchard C, et al. IL-9- and mast cell-mediated intestinal permeability predisposes to oral antigen hypersensitivity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:897–913. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moneret-Vautrin DA, Guerin L, Kanny G, Flabbee J, Fremont S, Morisset M. Cross-allergenicity of peanut and lupine: the risk of lupine allergy in patients allergic to peanuts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:883–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Faeste CK, Namork E, Lindvik H. Allergenicity and antigenicity of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) proteins in foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rozenfeld P, Docena GH, Anon MC, Fossati CA. Detection and identification of a soy protein component that cross-reacts with caseins from cow’s milk. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:49–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.t01-1-01935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Curciarello R, Lareu JF, Fossati CA, Docena GH, Petruccelli S. Immunochemical characterization of Glycine max L. Merr. var Raiden, as a possible hypoallergenic substitute for cow’s milk-allergic patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;38:1559–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smaldini P, Curciarello R, Candreva A, Rey MA, Fossati CA, Petruccelli S, et al. In vivo evidence of cross-reactivity between cow’s milk and soybean proteins in a mouse model of food allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;158:335–46. doi: 10.1159/000333562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lack G, Fox D, Northstone K, Golding J. Factors associated with the development of peanut allergy in childhood. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:977–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fox DE, Lack G. Peanut allergy. Lancet. 1998;352:741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60863-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fox AT, Sasieni P, du Toit G, Syed H, Lack G. Household peanut consumption as a risk factor for the development of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:417–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown SJ, Asai Y, Cordell HJ, Campbell LE, Zhao Y, Liao H, et al. Loss-of-function variants in the filaggrin gene are a significant risk factor for peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:661–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:441–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spergel JM, Mizoguchi E, Brewer JP, Martin TR, Bhan AK, Geha RS. Epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen induces localized allergic dermatitis and hyperresponsiveness to methacholine after single exposure to aerosolized antigen in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1614– 22. doi: 10.1172/JCI1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fallon PG, Sasaki T, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Saunders SP, Mangan NE, et al. A homozygous frameshift mutation in the mouse Flg gene facilitates enhanced percutaneous allergen priming. Nat Genet. 2009;41:602–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oyoshi MK, Murphy GF, Geha RS. Filaggrin-deficient mice exhibit TH17-dominated skin inflammation and permissiveness to epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:485–93. 93 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Otsuka A, Doi H, Egawa G, Maekawa A, Fujita T, Nakamizo S, et al. Possible new therapeutic strategy to regulate atopic dermatitis through upregulating filaggrin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sicherer SH, Wood RA, Stablein D, Lindblad R, Burks AW, Liu AH, et al. Maternal consumption of peanut during pregnancy is associated with peanut sensitization in atopic infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lopez-Exposito I, Song Y, Jarvinen KM, Srivastava K, Li XM. Maternal peanut exposure during pregnancy and lactation reduces peanut allergy risk in offspring. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1039–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamamoto T, Tsubota Y, Kodama T, Kageyama-Yahara N, Kadowaki M. Oral tolerance induced by transfer of food antigens via breast milk of allergic mothers prevents offspring from developing allergic symptoms in a mouse food allergy model. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:721085. doi: 10.1155/2012/721085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Verhasselt V, Milcent V, Cazareth J, Kanda A, Fleury S, Dombrowicz D, et al. Breast milk-mediated transfer of an antigen induces tolerance and protection from allergic asthma. Nat Med. 2008;14:170–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mosconi E, Rekima A, Seitz-Polski B, Kanda A, Fleury S, Tissandie E, et al. Breast milk immune complexes are potent inducers of oral tolerance in neonates and prevent asthma development. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:461–74. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brand S, Teich R, Dicke T, Harb H, Yildirim AO, Tost J, et al. Epigenetic regulation in murine offspring as a novel mechanism for transmaternal asthma protection induced by microbes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:618–25. e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Untersmayr E, Jensen-Jarolim E. The role of protein digestibility and antacids on food allergy outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1301–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.025. quiz 9–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Untersmayr E, Bakos N, Scholl I, Kundi M, Roth-Walter F, Szalai K, et al. Anti-ulcer drugs promote IgE formation toward dietary antigens in adult patients. FASEB J. 2005;19:656–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3170fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dehlink E, Yen E, Leichtner AM, Hait EJ, Fiebiger E. First evidence of a possible association between gastric acid suppression during pregnancy and childhood asthma: a population-based register study. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;39:246–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scholl I, Untersmayr E, Bakos N, Roth-Walter F, Gleiss A, Boltz-Nitulescu G, et al. Antiulcer drugs promote oral sensitization and hypersensitivity to hazelnut allergens in BALB/c mice and humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:154–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scholl I, Ackermann U, Ozdemir C, Blumer N, Dicke T, Sel S, et al. Anti-ulcer treatment during pregnancy induces food allergy in mouse mothers and a Th2-bias in their offspring. FASEB J. 2007;21:1264–70. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7223com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Flokstra-de Blok BM, Dubois AE, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, Raat H, DunnGalvin A, et al. Health-related quality of life of food allergic patients: comparison with the general population and other diseases. Allergy. 2010;65:238–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:S1–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin RY, Curry A, Pesola GR, Knight RJ, Lee HS, Bakalchuk L, et al. Improved outcomes in patients with acute allergic syndromes who are treated with combined H1 and H2 antagonists. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:462–8. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.109445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wechsler JB, Schroeder HA, Byrne AJ, Chien KB, Bryce PJ. Anaphylactic responses to histamine in mice utilize both histamine receptors 1 and 2. Allergy. 2013 doi: 10.1111/all.12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vickery BP, Burks W. Oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:765–70. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833f5fc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nurmatov U, Venderbosch I, Devereux G, Simons FE, Sheikh A. Allergen-specific oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD009014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009014.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leonard SA, Martos G, Wang W, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Berin MC. Oral immunotherapy induces local protective mechanisms in the gastrointestinal mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1579–87. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yamaki K, Yoshino S. Preventive and therapeutic effects of rapamycin, a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, on food allergy in mice. Allergy. 2012;67:1259–70. doi: 10.1111/all.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sugimura T, Tananari Y, Ozaki Y, Maeno Y, Ito S, Yoshimoto Y, et al. Effect of oral sodium cromoglycate in 2 children with food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis (FDEIA) Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48:945–50. doi: 10.1177/0009922809337528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Juji F, Suko M. Effectiveness of disodium cromoglycate in food-dependent, exercise-induced anaphylaxis: a case report. Ann Allergy. 1994;72:452–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yamaki K, Yoshino S. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib relieves systemic and oral antigen-induced anaphylaxes in mice. Allergy. 2012;67:114–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Motzer RJ, Hoosen S, Bello CL, Christensen JG. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of solid tumours: a review of current clinical data. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:553–61. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.5.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang J. Treatment of food anaphylaxis with traditional Chinese herbal remedies: from mouse model to human clinical trials. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:386–91. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283615bc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Srivastava KD, Qu C, Zhang T, Goldfarb J, Sampson HA, Li XM. Food Allergy Herbal Formula-2 silences peanut-induced anaphylaxis for a prolonged posttreatment period via IFN-gamma-producing CD8+ T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.12.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patil SP, Wang J, Song Y, Noone S, Yang N, Wallenstein S, et al. Clinical safety of Food Allergy Herbal Formula-2 (FAHF-2) and inhibitory effect on basophils from patients with food allergy: Extended phase I study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1259–65. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schneider LC, Rachid R, Lebovidge J, Blood E, Mittal M, Umetsu DT. A pilot study of omalizumab to facilitate rapid oral desensitization in high-risk peanut-allergic patients. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;132:1368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brightbill HD, Jeet S, Lin Z, Yan D, Zhou M, Tan M, et al. Antibodies specific for a segment of human membrane IgE deplete IgE-producing B cells in humanized mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:2218–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI40141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smarr CB, Hsu CL, Byrne AJ, Miller SD, Bryce PJ. Antigen-fixed leukocytes tolerize Th2 responses in mouse models of allergy. J Immunol. 2011;187:5090–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Miller SD, Turley DM, Podojil JR. Antigen-specific tolerance strategies for the prevention and treatment of autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:665–77. doi: 10.1038/nri2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lutterotti A, Yousef S, Sputtek A, Sturner KH, Stellmann JP, Breiden P, et al. Antigen-specific tolerance by autologous myelin peptide-coupled cells: a phase 1 trial in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:188ra75. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]